User login

Stable, long-term opioid therapy safer than tapering?

Investigators analyzed data for almost 200,000 patients who did not have signs of opioid use disorder (OUD) and were receiving opioid treatment. The investigators compared three dosing strategies: abrupt withdrawal, gradual tapering, and continuation of the current stable dosage.

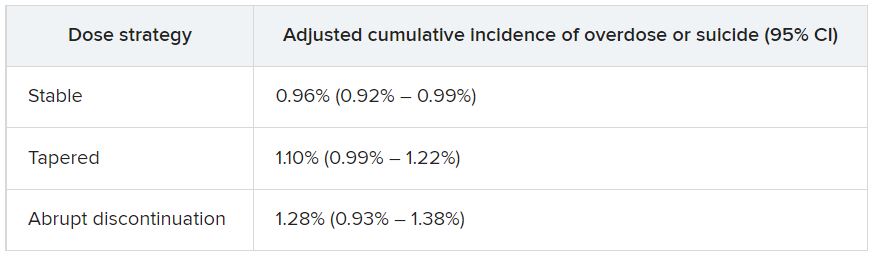

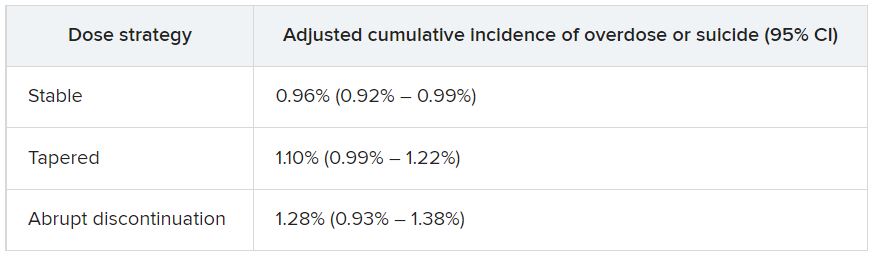

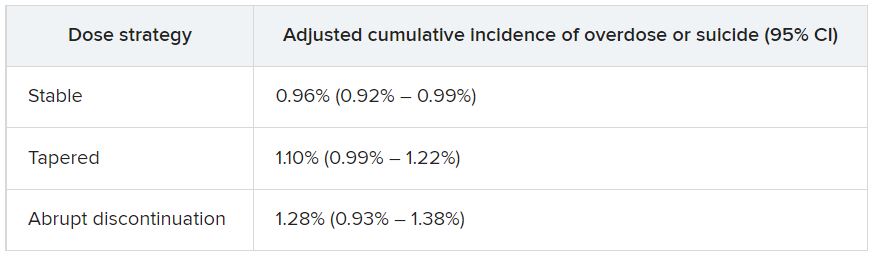

Results showed a higher adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events 11 months after baseline among participants for whom a tapered dosing strategy was utilized, compared with those who continued taking a stable dosage. The risk difference was 0.15% between taper and stable dosage and 0.33% between abrupt discontinuation and stable dosage.

“This study identified a small absolute increase in risk of harms associated with opioid tapering compared with a stable opioid dosage,” Marc LaRochelle, MD, MPH, assistant professor, Boston University, and colleagues write.

“These results do not suggest that policies of mandatory dosage tapering for individuals receiving a stable long-term opioid dosage without evidence of opioid misuse will reduce short-term harm via suicide and overdose,” they add.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Benefits vs. harms

The investigators note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in its 2016 Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, “recommended tapering opioid dosages if benefits no longer outweigh harms.”

In response, “some health systems and U.S. states enacted stringent dose limits that were applied with few exceptions, regardless of individual patients’ risk of harms,” they write. By contrast, there have been “increasing reports of patients experiencing adverse effects from forced opioid tapers.”

Previous studies that identified harms associated with opioid tapering and discontinuation had several limitations, including a focus on discontinuation, which is “likely more destabilizing than gradual tapering,” the researchers write. There is also “a high potential for confounding” in these studies, they add.

The investigators sought to fill the research gap by drawing on 8-year data (Jan. 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2018) from a large database that includes adjudicated pharmacy, outpatient, and inpatient medical claims for individuals with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance encompassing all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

Notably, individuals who had received a diagnosis of substance use, abuse, or dependence or for whom there were indicators consistent with OUD were excluded.

The researchers compared the three treatment strategies during a 4-month treatment strategy assignment period (“grace period”) after baseline. Tapering was defined as “2 consecutive months with a mean MME [morphine milligram equivalent] reduction of 15% or more compared with the baseline month.”

All estimates were adjusted for potential confounders, including demographic and treatment characteristics, baseline year, region, insurance plan type, comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions, and the prescribing of other psychiatric medications, such as benzodiazepines, gabapentin, or pregabalin.

Patient-centered approaches

The final cohort that met inclusion criteria consisted of 199,836 individuals (45.1% men; mean age, 56.9 years). Of the total group, 57.6% were aged 45-64 years. There were 415,123 qualifying long-term opioid therapy episodes.

The largest percentage of the cohort (41.2%) were receiving a baseline mean MME of 50-89 mg/day, while 34% were receiving 90-199 mg/day and 23.5% were receiving at least 200 mg/day.

During the 6-month eligibility assessment period, 34.8% of the cohort were receiving benzodiazepine prescriptions, 18% had been diagnosed with comorbid anxiety, and 19.7% had been diagnosed with comorbid depression.

After the treatment assignment period, most treatment episodes (87.1%) were considered stable, 11.1% were considered a taper, and 1.8% were considered abrupt discontinuation.

Eleven months after baseline, the adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events was lowest for those who continued to receive a stable dose.

The risk differences between taper vs. stable dosage were 0.15% (95% confidence interval, 0.03%-0.26%), and the risk differences between abrupt discontinuation and stable dose were 0.33% (95% CI, −0.03%-0.74%). The risk ratios associated with taper vs. stable dosage and abrupt discontinuation vs. stable dosage were 1.15 (95% CI, 1.04-1.27) and 1.34 (95% CI, 0.97-1.79), respectively.

The adjusted cumulative incidence curves for overdose or suicide diverged at month 4 when comparing stable dosage and taper, with a higher incidence associated with the taper vs. stable dosage treatment strategies thereafter. However, when the researchers compared stable dosage with abrupt discontinuation, the event rates were similar.

A per protocol analysis, in which the researchers censored episodes involving lack of adherence to assigned treatment, yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

“Policies establishing dosage thresholds or mandating tapers for all patients receiving long-term opioid therapy are not supported by existing data in terms of anticipated benefits even if, as we found, the rate of adverse outcomes is small,” the investigators write.

Instead, they encourage health care systems and clinicians to “continue to develop and implement patient-centered approaches to pain management for patients with established long-term opioid therapy.”

Protracted withdrawal?

Commenting on the study, A. Benjamin Srivastava, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, division on substance use disorders, Columbia University Medical Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, called the study “an important contribution to the literature” that “sheds further light on the risks associated with tapering.”

Dr. Srivastava, who was not involved with the research, noted that previous studies showing an increased prevalence of adverse events with tapering included participants with OUD or signs of opioid misuse, “potentially confounding findings.”

By contrast, the current study investigators specifically excluded patients with OUD/opioid misuse but still found a “slight increase in risk for opioid overdose and suicide, even when excluding for potential confounders,” he said.

Although causal implications require further investigation, “a source of these adverse outcomes may be unmanaged withdrawal that may be protracted,” Dr. Srivastava noted.

While abrupt discontinuation “may result in significant acute withdrawal symptoms, these should subside by 1-2 weeks at most,” he said.

Lowering the dose without discontinuation may lead to patients’ entering into “a dyshomeostatic state characterized by anxiety and dysphoria ... that may not be recognized by the prescribing clinician,” he added.

The brain “is still being primed by opioids [and] ‘wanting’ a higher dose. Thus, particular attention to withdrawal symptoms, both physical and psychiatric, is prudent when choosing to taper opioids vs. maintaining or discontinuing,” Dr. Srivastava said.

The study was funded by a grant from the CDC and a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to one of the investigators. Dr. LaRochelle received grants from the CDC and NIDA during the conduct of the study and has received consulting fees for research paid to his institution from OptumLabs outside the submitted work. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Srivastava reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data for almost 200,000 patients who did not have signs of opioid use disorder (OUD) and were receiving opioid treatment. The investigators compared three dosing strategies: abrupt withdrawal, gradual tapering, and continuation of the current stable dosage.

Results showed a higher adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events 11 months after baseline among participants for whom a tapered dosing strategy was utilized, compared with those who continued taking a stable dosage. The risk difference was 0.15% between taper and stable dosage and 0.33% between abrupt discontinuation and stable dosage.

“This study identified a small absolute increase in risk of harms associated with opioid tapering compared with a stable opioid dosage,” Marc LaRochelle, MD, MPH, assistant professor, Boston University, and colleagues write.

“These results do not suggest that policies of mandatory dosage tapering for individuals receiving a stable long-term opioid dosage without evidence of opioid misuse will reduce short-term harm via suicide and overdose,” they add.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Benefits vs. harms

The investigators note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in its 2016 Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, “recommended tapering opioid dosages if benefits no longer outweigh harms.”

In response, “some health systems and U.S. states enacted stringent dose limits that were applied with few exceptions, regardless of individual patients’ risk of harms,” they write. By contrast, there have been “increasing reports of patients experiencing adverse effects from forced opioid tapers.”

Previous studies that identified harms associated with opioid tapering and discontinuation had several limitations, including a focus on discontinuation, which is “likely more destabilizing than gradual tapering,” the researchers write. There is also “a high potential for confounding” in these studies, they add.

The investigators sought to fill the research gap by drawing on 8-year data (Jan. 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2018) from a large database that includes adjudicated pharmacy, outpatient, and inpatient medical claims for individuals with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance encompassing all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

Notably, individuals who had received a diagnosis of substance use, abuse, or dependence or for whom there were indicators consistent with OUD were excluded.

The researchers compared the three treatment strategies during a 4-month treatment strategy assignment period (“grace period”) after baseline. Tapering was defined as “2 consecutive months with a mean MME [morphine milligram equivalent] reduction of 15% or more compared with the baseline month.”

All estimates were adjusted for potential confounders, including demographic and treatment characteristics, baseline year, region, insurance plan type, comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions, and the prescribing of other psychiatric medications, such as benzodiazepines, gabapentin, or pregabalin.

Patient-centered approaches

The final cohort that met inclusion criteria consisted of 199,836 individuals (45.1% men; mean age, 56.9 years). Of the total group, 57.6% were aged 45-64 years. There were 415,123 qualifying long-term opioid therapy episodes.

The largest percentage of the cohort (41.2%) were receiving a baseline mean MME of 50-89 mg/day, while 34% were receiving 90-199 mg/day and 23.5% were receiving at least 200 mg/day.

During the 6-month eligibility assessment period, 34.8% of the cohort were receiving benzodiazepine prescriptions, 18% had been diagnosed with comorbid anxiety, and 19.7% had been diagnosed with comorbid depression.

After the treatment assignment period, most treatment episodes (87.1%) were considered stable, 11.1% were considered a taper, and 1.8% were considered abrupt discontinuation.

Eleven months after baseline, the adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events was lowest for those who continued to receive a stable dose.

The risk differences between taper vs. stable dosage were 0.15% (95% confidence interval, 0.03%-0.26%), and the risk differences between abrupt discontinuation and stable dose were 0.33% (95% CI, −0.03%-0.74%). The risk ratios associated with taper vs. stable dosage and abrupt discontinuation vs. stable dosage were 1.15 (95% CI, 1.04-1.27) and 1.34 (95% CI, 0.97-1.79), respectively.

The adjusted cumulative incidence curves for overdose or suicide diverged at month 4 when comparing stable dosage and taper, with a higher incidence associated with the taper vs. stable dosage treatment strategies thereafter. However, when the researchers compared stable dosage with abrupt discontinuation, the event rates were similar.

A per protocol analysis, in which the researchers censored episodes involving lack of adherence to assigned treatment, yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

“Policies establishing dosage thresholds or mandating tapers for all patients receiving long-term opioid therapy are not supported by existing data in terms of anticipated benefits even if, as we found, the rate of adverse outcomes is small,” the investigators write.

Instead, they encourage health care systems and clinicians to “continue to develop and implement patient-centered approaches to pain management for patients with established long-term opioid therapy.”

Protracted withdrawal?

Commenting on the study, A. Benjamin Srivastava, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, division on substance use disorders, Columbia University Medical Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, called the study “an important contribution to the literature” that “sheds further light on the risks associated with tapering.”

Dr. Srivastava, who was not involved with the research, noted that previous studies showing an increased prevalence of adverse events with tapering included participants with OUD or signs of opioid misuse, “potentially confounding findings.”

By contrast, the current study investigators specifically excluded patients with OUD/opioid misuse but still found a “slight increase in risk for opioid overdose and suicide, even when excluding for potential confounders,” he said.

Although causal implications require further investigation, “a source of these adverse outcomes may be unmanaged withdrawal that may be protracted,” Dr. Srivastava noted.

While abrupt discontinuation “may result in significant acute withdrawal symptoms, these should subside by 1-2 weeks at most,” he said.

Lowering the dose without discontinuation may lead to patients’ entering into “a dyshomeostatic state characterized by anxiety and dysphoria ... that may not be recognized by the prescribing clinician,” he added.

The brain “is still being primed by opioids [and] ‘wanting’ a higher dose. Thus, particular attention to withdrawal symptoms, both physical and psychiatric, is prudent when choosing to taper opioids vs. maintaining or discontinuing,” Dr. Srivastava said.

The study was funded by a grant from the CDC and a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to one of the investigators. Dr. LaRochelle received grants from the CDC and NIDA during the conduct of the study and has received consulting fees for research paid to his institution from OptumLabs outside the submitted work. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Srivastava reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators analyzed data for almost 200,000 patients who did not have signs of opioid use disorder (OUD) and were receiving opioid treatment. The investigators compared three dosing strategies: abrupt withdrawal, gradual tapering, and continuation of the current stable dosage.

Results showed a higher adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events 11 months after baseline among participants for whom a tapered dosing strategy was utilized, compared with those who continued taking a stable dosage. The risk difference was 0.15% between taper and stable dosage and 0.33% between abrupt discontinuation and stable dosage.

“This study identified a small absolute increase in risk of harms associated with opioid tapering compared with a stable opioid dosage,” Marc LaRochelle, MD, MPH, assistant professor, Boston University, and colleagues write.

“These results do not suggest that policies of mandatory dosage tapering for individuals receiving a stable long-term opioid dosage without evidence of opioid misuse will reduce short-term harm via suicide and overdose,” they add.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

Benefits vs. harms

The investigators note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in its 2016 Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, “recommended tapering opioid dosages if benefits no longer outweigh harms.”

In response, “some health systems and U.S. states enacted stringent dose limits that were applied with few exceptions, regardless of individual patients’ risk of harms,” they write. By contrast, there have been “increasing reports of patients experiencing adverse effects from forced opioid tapers.”

Previous studies that identified harms associated with opioid tapering and discontinuation had several limitations, including a focus on discontinuation, which is “likely more destabilizing than gradual tapering,” the researchers write. There is also “a high potential for confounding” in these studies, they add.

The investigators sought to fill the research gap by drawing on 8-year data (Jan. 1, 2010, to Dec. 31, 2018) from a large database that includes adjudicated pharmacy, outpatient, and inpatient medical claims for individuals with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance encompassing all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

Notably, individuals who had received a diagnosis of substance use, abuse, or dependence or for whom there were indicators consistent with OUD were excluded.

The researchers compared the three treatment strategies during a 4-month treatment strategy assignment period (“grace period”) after baseline. Tapering was defined as “2 consecutive months with a mean MME [morphine milligram equivalent] reduction of 15% or more compared with the baseline month.”

All estimates were adjusted for potential confounders, including demographic and treatment characteristics, baseline year, region, insurance plan type, comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions, and the prescribing of other psychiatric medications, such as benzodiazepines, gabapentin, or pregabalin.

Patient-centered approaches

The final cohort that met inclusion criteria consisted of 199,836 individuals (45.1% men; mean age, 56.9 years). Of the total group, 57.6% were aged 45-64 years. There were 415,123 qualifying long-term opioid therapy episodes.

The largest percentage of the cohort (41.2%) were receiving a baseline mean MME of 50-89 mg/day, while 34% were receiving 90-199 mg/day and 23.5% were receiving at least 200 mg/day.

During the 6-month eligibility assessment period, 34.8% of the cohort were receiving benzodiazepine prescriptions, 18% had been diagnosed with comorbid anxiety, and 19.7% had been diagnosed with comorbid depression.

After the treatment assignment period, most treatment episodes (87.1%) were considered stable, 11.1% were considered a taper, and 1.8% were considered abrupt discontinuation.

Eleven months after baseline, the adjusted cumulative incidence of opioid overdose or suicide events was lowest for those who continued to receive a stable dose.

The risk differences between taper vs. stable dosage were 0.15% (95% confidence interval, 0.03%-0.26%), and the risk differences between abrupt discontinuation and stable dose were 0.33% (95% CI, −0.03%-0.74%). The risk ratios associated with taper vs. stable dosage and abrupt discontinuation vs. stable dosage were 1.15 (95% CI, 1.04-1.27) and 1.34 (95% CI, 0.97-1.79), respectively.

The adjusted cumulative incidence curves for overdose or suicide diverged at month 4 when comparing stable dosage and taper, with a higher incidence associated with the taper vs. stable dosage treatment strategies thereafter. However, when the researchers compared stable dosage with abrupt discontinuation, the event rates were similar.

A per protocol analysis, in which the researchers censored episodes involving lack of adherence to assigned treatment, yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

“Policies establishing dosage thresholds or mandating tapers for all patients receiving long-term opioid therapy are not supported by existing data in terms of anticipated benefits even if, as we found, the rate of adverse outcomes is small,” the investigators write.

Instead, they encourage health care systems and clinicians to “continue to develop and implement patient-centered approaches to pain management for patients with established long-term opioid therapy.”

Protracted withdrawal?

Commenting on the study, A. Benjamin Srivastava, MD, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, division on substance use disorders, Columbia University Medical Center, New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, called the study “an important contribution to the literature” that “sheds further light on the risks associated with tapering.”

Dr. Srivastava, who was not involved with the research, noted that previous studies showing an increased prevalence of adverse events with tapering included participants with OUD or signs of opioid misuse, “potentially confounding findings.”

By contrast, the current study investigators specifically excluded patients with OUD/opioid misuse but still found a “slight increase in risk for opioid overdose and suicide, even when excluding for potential confounders,” he said.

Although causal implications require further investigation, “a source of these adverse outcomes may be unmanaged withdrawal that may be protracted,” Dr. Srivastava noted.

While abrupt discontinuation “may result in significant acute withdrawal symptoms, these should subside by 1-2 weeks at most,” he said.

Lowering the dose without discontinuation may lead to patients’ entering into “a dyshomeostatic state characterized by anxiety and dysphoria ... that may not be recognized by the prescribing clinician,” he added.

The brain “is still being primed by opioids [and] ‘wanting’ a higher dose. Thus, particular attention to withdrawal symptoms, both physical and psychiatric, is prudent when choosing to taper opioids vs. maintaining or discontinuing,” Dr. Srivastava said.

The study was funded by a grant from the CDC and a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to one of the investigators. Dr. LaRochelle received grants from the CDC and NIDA during the conduct of the study and has received consulting fees for research paid to his institution from OptumLabs outside the submitted work. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Srivastava reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Thyroid autoimmunity linked to cancer, but screening not advised

A new study provides more evidence that people with thyroid autoimmunity are more likely than are others to develop papillary thyroid cancer (odds ratio [OR] = 1.90, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.33-2.70), although the overall risk remains very low.

Researchers aren't recommending routine screening in all patients with thyroid autoimmunity, but they're calling for more research into whether it's a good idea in severe cases. "This is the one circumstance where screening for subclinical disease could make sense," said Donald McLeod, MPH, PhD, an epidemiologist at Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital in Australia and lead author of the study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. "However, more research is needed because our study is the first to show this result, and we need to prove that screening would make a difference to the prognosis of these patients."

According to Dr. McLeod, "doctors and patients have been wondering about the connection between thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid cancer for many years. In fact, the first report was in 1955. While the association was plausible, all previous studies had potential for biases that could have influenced the results."

For example, he said, multiple studies didn't control for confounders, while others didn't account for the possibility that cancer could have triggered an immune response. "Other case-control studies could have been affected by selection bias, where a diagnosis of thyroid autoimmunity leads to thyroid cancer identification and entry into the study," he said. "Finally, medical surveillance of people diagnosed with thyroid autoimmunity could lead to overdiagnosis, where small, subclinical cancers are diagnosed in those patients but not identified in people who are not under medical follow-up."

For the new retrospective case-control study, researchers compared 451 active-duty members of the U.S. military who developed papillary thyroid cancer from the period of 1996-2014 to matched controls (61% of all subjects were men and the mean age was 36). Those with cancer had their serum collected 3-5 years and 7-10 years before the date of diagnosis - the index date for all subjects. Some of those considered to have thyroid autoimmunity had conditions such as Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

"Eighty-five percent of cases (379 of 451) had a thyroid-related diagnosis recorded ... before their index date, compared with 5% of controls," the researchers reported. "Most cases (80%) had classical papillary thyroid cancer, with the rest having the follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer."

After adjustment to account for various confounders, those who were positive for thyroid peroxidase antibodies 7-10 years prior to the index date were more likely to have developed thyroid cancer (OR = 1.90, 95% CI, 1.33-2.70). "The results could not be fully explained by diagnosis of thyroid autoimmunity," the researchers reported, "although when autoimmunity had been identified, thyroid cancers were diagnosed at a very early stage."

Two groups - those with the highest thyroid antibody levels and women - faced the greatest risk, Dr. McLeod said. The results regarding women were the most surprising in the study, he said. "This is the first time this has been found. We think this result needs to be confirmed. If true, it could explain why women have a three-times-higher risk of thyroid cancer than men."

The overall incidence of thyroid cancer in the U.S. was estimated at 13.49 per 100,000 person-years in 2018, with women (76% of cases) and Whites (81%) accounting for the majority. Rates have nearly doubled since 2000. The authors of a 2022 report that disclosed these numbers suggest the rise is due to overdiagnosis of small tumors.

It's not clear why thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid cancer may be linked. "Chronic inflammation from thyroid autoimmunity could cause thyroid cancer, as chronic inflammation in other organs precedes cancers at those sites," Dr. McLeod said. "Alternatively, thyroid autoimmunity could appear to be associated with thyroid cancer because of biases inherent in previous studies, including previous diagnosis of autoimmunity. Thyroid cancer could also induce an immune response, which mimics thyroid autoimmunity and could bias assessment."

As for screening of patients with thyroid autoimmunity, "the main danger is that you will commonly identify small thyroid cancers that would never become clinically apparent," he said. "This leads to unnecessary treatments that can cause complications and give people a cancer label, which can also cause harm. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines recommend against screening the general population for this reason."

Many of those with thyroid autoimmunity developed small cancers, he said, most likely "detected from ultrasound being performed because autoimmune thyroid disease was known. If all patients with thyroid autoimmunity were screened for thyroid cancer, the likelihood is that many people's cancers would be overdiagnosed."

The study was funded by the Walton Family Foundation. Dr. McLeod reports no disclosures. Some of the authors report various relationships with industry.

A new study provides more evidence that people with thyroid autoimmunity are more likely than are others to develop papillary thyroid cancer (odds ratio [OR] = 1.90, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.33-2.70), although the overall risk remains very low.

Researchers aren't recommending routine screening in all patients with thyroid autoimmunity, but they're calling for more research into whether it's a good idea in severe cases. "This is the one circumstance where screening for subclinical disease could make sense," said Donald McLeod, MPH, PhD, an epidemiologist at Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital in Australia and lead author of the study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. "However, more research is needed because our study is the first to show this result, and we need to prove that screening would make a difference to the prognosis of these patients."

According to Dr. McLeod, "doctors and patients have been wondering about the connection between thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid cancer for many years. In fact, the first report was in 1955. While the association was plausible, all previous studies had potential for biases that could have influenced the results."

For example, he said, multiple studies didn't control for confounders, while others didn't account for the possibility that cancer could have triggered an immune response. "Other case-control studies could have been affected by selection bias, where a diagnosis of thyroid autoimmunity leads to thyroid cancer identification and entry into the study," he said. "Finally, medical surveillance of people diagnosed with thyroid autoimmunity could lead to overdiagnosis, where small, subclinical cancers are diagnosed in those patients but not identified in people who are not under medical follow-up."

For the new retrospective case-control study, researchers compared 451 active-duty members of the U.S. military who developed papillary thyroid cancer from the period of 1996-2014 to matched controls (61% of all subjects were men and the mean age was 36). Those with cancer had their serum collected 3-5 years and 7-10 years before the date of diagnosis - the index date for all subjects. Some of those considered to have thyroid autoimmunity had conditions such as Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

"Eighty-five percent of cases (379 of 451) had a thyroid-related diagnosis recorded ... before their index date, compared with 5% of controls," the researchers reported. "Most cases (80%) had classical papillary thyroid cancer, with the rest having the follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer."

After adjustment to account for various confounders, those who were positive for thyroid peroxidase antibodies 7-10 years prior to the index date were more likely to have developed thyroid cancer (OR = 1.90, 95% CI, 1.33-2.70). "The results could not be fully explained by diagnosis of thyroid autoimmunity," the researchers reported, "although when autoimmunity had been identified, thyroid cancers were diagnosed at a very early stage."

Two groups - those with the highest thyroid antibody levels and women - faced the greatest risk, Dr. McLeod said. The results regarding women were the most surprising in the study, he said. "This is the first time this has been found. We think this result needs to be confirmed. If true, it could explain why women have a three-times-higher risk of thyroid cancer than men."

The overall incidence of thyroid cancer in the U.S. was estimated at 13.49 per 100,000 person-years in 2018, with women (76% of cases) and Whites (81%) accounting for the majority. Rates have nearly doubled since 2000. The authors of a 2022 report that disclosed these numbers suggest the rise is due to overdiagnosis of small tumors.

It's not clear why thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid cancer may be linked. "Chronic inflammation from thyroid autoimmunity could cause thyroid cancer, as chronic inflammation in other organs precedes cancers at those sites," Dr. McLeod said. "Alternatively, thyroid autoimmunity could appear to be associated with thyroid cancer because of biases inherent in previous studies, including previous diagnosis of autoimmunity. Thyroid cancer could also induce an immune response, which mimics thyroid autoimmunity and could bias assessment."

As for screening of patients with thyroid autoimmunity, "the main danger is that you will commonly identify small thyroid cancers that would never become clinically apparent," he said. "This leads to unnecessary treatments that can cause complications and give people a cancer label, which can also cause harm. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines recommend against screening the general population for this reason."

Many of those with thyroid autoimmunity developed small cancers, he said, most likely "detected from ultrasound being performed because autoimmune thyroid disease was known. If all patients with thyroid autoimmunity were screened for thyroid cancer, the likelihood is that many people's cancers would be overdiagnosed."

The study was funded by the Walton Family Foundation. Dr. McLeod reports no disclosures. Some of the authors report various relationships with industry.

A new study provides more evidence that people with thyroid autoimmunity are more likely than are others to develop papillary thyroid cancer (odds ratio [OR] = 1.90, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.33-2.70), although the overall risk remains very low.

Researchers aren't recommending routine screening in all patients with thyroid autoimmunity, but they're calling for more research into whether it's a good idea in severe cases. "This is the one circumstance where screening for subclinical disease could make sense," said Donald McLeod, MPH, PhD, an epidemiologist at Royal Brisbane & Women's Hospital in Australia and lead author of the study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. "However, more research is needed because our study is the first to show this result, and we need to prove that screening would make a difference to the prognosis of these patients."

According to Dr. McLeod, "doctors and patients have been wondering about the connection between thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid cancer for many years. In fact, the first report was in 1955. While the association was plausible, all previous studies had potential for biases that could have influenced the results."

For example, he said, multiple studies didn't control for confounders, while others didn't account for the possibility that cancer could have triggered an immune response. "Other case-control studies could have been affected by selection bias, where a diagnosis of thyroid autoimmunity leads to thyroid cancer identification and entry into the study," he said. "Finally, medical surveillance of people diagnosed with thyroid autoimmunity could lead to overdiagnosis, where small, subclinical cancers are diagnosed in those patients but not identified in people who are not under medical follow-up."

For the new retrospective case-control study, researchers compared 451 active-duty members of the U.S. military who developed papillary thyroid cancer from the period of 1996-2014 to matched controls (61% of all subjects were men and the mean age was 36). Those with cancer had their serum collected 3-5 years and 7-10 years before the date of diagnosis - the index date for all subjects. Some of those considered to have thyroid autoimmunity had conditions such as Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

"Eighty-five percent of cases (379 of 451) had a thyroid-related diagnosis recorded ... before their index date, compared with 5% of controls," the researchers reported. "Most cases (80%) had classical papillary thyroid cancer, with the rest having the follicular variant of papillary thyroid cancer."

After adjustment to account for various confounders, those who were positive for thyroid peroxidase antibodies 7-10 years prior to the index date were more likely to have developed thyroid cancer (OR = 1.90, 95% CI, 1.33-2.70). "The results could not be fully explained by diagnosis of thyroid autoimmunity," the researchers reported, "although when autoimmunity had been identified, thyroid cancers were diagnosed at a very early stage."

Two groups - those with the highest thyroid antibody levels and women - faced the greatest risk, Dr. McLeod said. The results regarding women were the most surprising in the study, he said. "This is the first time this has been found. We think this result needs to be confirmed. If true, it could explain why women have a three-times-higher risk of thyroid cancer than men."

The overall incidence of thyroid cancer in the U.S. was estimated at 13.49 per 100,000 person-years in 2018, with women (76% of cases) and Whites (81%) accounting for the majority. Rates have nearly doubled since 2000. The authors of a 2022 report that disclosed these numbers suggest the rise is due to overdiagnosis of small tumors.

It's not clear why thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid cancer may be linked. "Chronic inflammation from thyroid autoimmunity could cause thyroid cancer, as chronic inflammation in other organs precedes cancers at those sites," Dr. McLeod said. "Alternatively, thyroid autoimmunity could appear to be associated with thyroid cancer because of biases inherent in previous studies, including previous diagnosis of autoimmunity. Thyroid cancer could also induce an immune response, which mimics thyroid autoimmunity and could bias assessment."

As for screening of patients with thyroid autoimmunity, "the main danger is that you will commonly identify small thyroid cancers that would never become clinically apparent," he said. "This leads to unnecessary treatments that can cause complications and give people a cancer label, which can also cause harm. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines recommend against screening the general population for this reason."

Many of those with thyroid autoimmunity developed small cancers, he said, most likely "detected from ultrasound being performed because autoimmune thyroid disease was known. If all patients with thyroid autoimmunity were screened for thyroid cancer, the likelihood is that many people's cancers would be overdiagnosed."

The study was funded by the Walton Family Foundation. Dr. McLeod reports no disclosures. Some of the authors report various relationships with industry.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

New model could boost BE screening, early diagnosis

A new model that predicts Barrett’s esophagus (BE) risk relies on data that can be sourced from the electronic health record.

The tool was developed and validated by researchers seeking to improve early diagnosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) through early detection of BE. Currently, 5-year survival from EAC is just 20%, and fewer than 30% of patients have curative options at diagnosis because of late-stage disease.

Several clinical guidelines recommend screening for BE in high-risk individuals. The trouble is that adherence is low: A meta-analysis of more than 33,000 patients found that 57% of newly diagnosed EAC patients had a simultaneous, first-time diagnosis of BE, which suggests missed screening opportunities. These patients also had higher probability of late-stage disease and worse mortality outcomes than patients who had a previous BE diagnosis. Low adherence to screening guidelines can be attributed to difficulties in implementation, as well as unsatisfactory outcomes in real-world settings. In a previous study, the researchers examined the efficacy of existing guidelines in diagnosing BE in a primary care population, and found all of these screening guidelines had a low area under the receiver operating curve ranging from 0.50 to 0.60.

The researchers sought to address these challenges in the current study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology using a model development cohort of 274 patients with BE and 1,350 patients without BE. The patients were seen at Houston Veterans Affairs clinics between 2008 and 2012, and were between ages 40 and 80 years. The researchers included common risk factors identified among existing guidelines. The final model, Houston-BEST, incorporated sex, age, race/ethnicity, smoking status, body mass index, symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (heartburn or reflux at least 1 day/week), and first-degree relative history of esophageal cancer.

The validation cohorts included patients from primary care clinics at the Houston VA who were undergoing screening colonoscopy (44 with BE, 469 without BE), as well as patients at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, or Ann Arbor VA clinics who presented for first esophagogastroduodenoscopy (71 with BE, 916 without BE).

In the development cohort, the researchers set an a priori threshold of predicted probability that corresponded to sensitivity of 90%; the threshold predicted probability of BE was 9.3% (AUROC, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.72). The specificity was 39.9% (95% CI, 37.2%-42.5%). In the Houston area validation cohort, the model had a sensitivity of 84.1% (AUROC, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.60-0.76). The number needed to treat to detect a single BE case was 11.

Among the University of Michigan/Ann Arbor validation cohort, the model had an AUROC of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.64-0.76), but it had a sensitivity of 0%. The researchers also tested the ability of the model to discriminate early neoplasia from no BE, and found an AUROC of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.67-0.77).

The researchers tested other models based on existing guidelines in the Houston area cohort and found that their model performed at the high end of the range when compared with those other models (AUROCs, 0.65-0.70 vs. 0.58-0.70). “While the predictive performance of Houston-BEST model is modest, it has much better discriminative ability compared to current societal clinical practice guidelines. However, the model may need to be further refined for lower risk (nonveteran) populations,” the authors wrote.

The strength of the model is that it relies on data found in the EHR. The researchers suggest that future studies should look employing the model alongside e-Trigger tools that can mine electronic clinical data to identify patients at risk for a missed diagnosis.

The authors reported no personal or financial conflicts of interest.

A new model that predicts Barrett’s esophagus (BE) risk relies on data that can be sourced from the electronic health record.

The tool was developed and validated by researchers seeking to improve early diagnosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) through early detection of BE. Currently, 5-year survival from EAC is just 20%, and fewer than 30% of patients have curative options at diagnosis because of late-stage disease.

Several clinical guidelines recommend screening for BE in high-risk individuals. The trouble is that adherence is low: A meta-analysis of more than 33,000 patients found that 57% of newly diagnosed EAC patients had a simultaneous, first-time diagnosis of BE, which suggests missed screening opportunities. These patients also had higher probability of late-stage disease and worse mortality outcomes than patients who had a previous BE diagnosis. Low adherence to screening guidelines can be attributed to difficulties in implementation, as well as unsatisfactory outcomes in real-world settings. In a previous study, the researchers examined the efficacy of existing guidelines in diagnosing BE in a primary care population, and found all of these screening guidelines had a low area under the receiver operating curve ranging from 0.50 to 0.60.

The researchers sought to address these challenges in the current study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology using a model development cohort of 274 patients with BE and 1,350 patients without BE. The patients were seen at Houston Veterans Affairs clinics between 2008 and 2012, and were between ages 40 and 80 years. The researchers included common risk factors identified among existing guidelines. The final model, Houston-BEST, incorporated sex, age, race/ethnicity, smoking status, body mass index, symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (heartburn or reflux at least 1 day/week), and first-degree relative history of esophageal cancer.

The validation cohorts included patients from primary care clinics at the Houston VA who were undergoing screening colonoscopy (44 with BE, 469 without BE), as well as patients at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, or Ann Arbor VA clinics who presented for first esophagogastroduodenoscopy (71 with BE, 916 without BE).

In the development cohort, the researchers set an a priori threshold of predicted probability that corresponded to sensitivity of 90%; the threshold predicted probability of BE was 9.3% (AUROC, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.72). The specificity was 39.9% (95% CI, 37.2%-42.5%). In the Houston area validation cohort, the model had a sensitivity of 84.1% (AUROC, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.60-0.76). The number needed to treat to detect a single BE case was 11.

Among the University of Michigan/Ann Arbor validation cohort, the model had an AUROC of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.64-0.76), but it had a sensitivity of 0%. The researchers also tested the ability of the model to discriminate early neoplasia from no BE, and found an AUROC of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.67-0.77).

The researchers tested other models based on existing guidelines in the Houston area cohort and found that their model performed at the high end of the range when compared with those other models (AUROCs, 0.65-0.70 vs. 0.58-0.70). “While the predictive performance of Houston-BEST model is modest, it has much better discriminative ability compared to current societal clinical practice guidelines. However, the model may need to be further refined for lower risk (nonveteran) populations,” the authors wrote.

The strength of the model is that it relies on data found in the EHR. The researchers suggest that future studies should look employing the model alongside e-Trigger tools that can mine electronic clinical data to identify patients at risk for a missed diagnosis.

The authors reported no personal or financial conflicts of interest.

A new model that predicts Barrett’s esophagus (BE) risk relies on data that can be sourced from the electronic health record.

The tool was developed and validated by researchers seeking to improve early diagnosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) through early detection of BE. Currently, 5-year survival from EAC is just 20%, and fewer than 30% of patients have curative options at diagnosis because of late-stage disease.

Several clinical guidelines recommend screening for BE in high-risk individuals. The trouble is that adherence is low: A meta-analysis of more than 33,000 patients found that 57% of newly diagnosed EAC patients had a simultaneous, first-time diagnosis of BE, which suggests missed screening opportunities. These patients also had higher probability of late-stage disease and worse mortality outcomes than patients who had a previous BE diagnosis. Low adherence to screening guidelines can be attributed to difficulties in implementation, as well as unsatisfactory outcomes in real-world settings. In a previous study, the researchers examined the efficacy of existing guidelines in diagnosing BE in a primary care population, and found all of these screening guidelines had a low area under the receiver operating curve ranging from 0.50 to 0.60.

The researchers sought to address these challenges in the current study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology using a model development cohort of 274 patients with BE and 1,350 patients without BE. The patients were seen at Houston Veterans Affairs clinics between 2008 and 2012, and were between ages 40 and 80 years. The researchers included common risk factors identified among existing guidelines. The final model, Houston-BEST, incorporated sex, age, race/ethnicity, smoking status, body mass index, symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (heartburn or reflux at least 1 day/week), and first-degree relative history of esophageal cancer.

The validation cohorts included patients from primary care clinics at the Houston VA who were undergoing screening colonoscopy (44 with BE, 469 without BE), as well as patients at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, or Ann Arbor VA clinics who presented for first esophagogastroduodenoscopy (71 with BE, 916 without BE).

In the development cohort, the researchers set an a priori threshold of predicted probability that corresponded to sensitivity of 90%; the threshold predicted probability of BE was 9.3% (AUROC, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.72). The specificity was 39.9% (95% CI, 37.2%-42.5%). In the Houston area validation cohort, the model had a sensitivity of 84.1% (AUROC, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.60-0.76). The number needed to treat to detect a single BE case was 11.

Among the University of Michigan/Ann Arbor validation cohort, the model had an AUROC of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.64-0.76), but it had a sensitivity of 0%. The researchers also tested the ability of the model to discriminate early neoplasia from no BE, and found an AUROC of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.67-0.77).

The researchers tested other models based on existing guidelines in the Houston area cohort and found that their model performed at the high end of the range when compared with those other models (AUROCs, 0.65-0.70 vs. 0.58-0.70). “While the predictive performance of Houston-BEST model is modest, it has much better discriminative ability compared to current societal clinical practice guidelines. However, the model may need to be further refined for lower risk (nonveteran) populations,” the authors wrote.

The strength of the model is that it relies on data found in the EHR. The researchers suggest that future studies should look employing the model alongside e-Trigger tools that can mine electronic clinical data to identify patients at risk for a missed diagnosis.

The authors reported no personal or financial conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Tumor-bed radiotherapy boost reduces DCIS recurrence risk

Giving a boost radiation dose to the tumor bed following breast-conserving surgery and whole breast irradiation (WBI) has been shown to be effective at reducing recurrence of invasive breast cancer, and now a multinational randomized trial has shown that it can do the same for patients with non–low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

“ wrote the authors, led by Boon H. Chua, PhD, from the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Among 1,608 patients with DCIS with at least one clinical or pathological marker for increased risk of local recurrence, 5-year rates of freedom from local recurrence were 97.1% for patients assigned to received a tumor bed boost versus 92.7% for patients who did not receive a boost dose. This difference translated into a hazard ratio for recurrence with radiation boost of 0.47 (P < .001).

“Our results support the use of tumor-bed boost radiation after postoperative WBI in patients with non–low-risk DCIS to optimize local control, and the adoption of moderately hypofractionated whole breast irradiation in practice to improve the balance of local control, toxicity, and socioeconomic burdens of treatment,” the authors wrote in a study published in The Lancet.

The investigators, from cancer centers in Australia, Europe, and Canada, noted that the advent of screening mammography was followed by a substantial increase in the diagnosis of DCIS. They also noted that patients who undergo breast-conserving surgery for DCIS are at risk for local recurrence, and half of recurrences present as invasive disease.

In addition, they said, there were high recurrence rates in randomized clinical for patients with DCIS who received conventionally fractionated WBI without a tumor boost following surgery.

“Further, the inconvenience of a 5- to 6-week course of conventionally fractionated WBI decreased the quality of life of patients. Thus, tailoring radiation dose fractionation according to recurrence risk is a prominent controversy in the radiation treatment of DCIS,” they wrote.

Four-way trial

To see whether a tumor-bed boost following WBI and alternative WBI fractionation schedules could improve outcomes for patients with non–low-risk DCIS, the researchers enrolled patients and assigned them on an equal basis to one of four groups, in which they would receive either conventional or hypofractionated WBI with or without a tumor-bed boost.

The conventional WBI regimen consisted of a total of 50 Gy delivered over 25 fractions. The hypofractionated regimen consisted of a total dose of 42.5 Gy delivered in 16 fractions. Patients assigned to get a boost dose to the tumor bed received an additional 16 Gy in eight fractions after WBI.

Of the 1,608 patients enrolled who eligible for randomization, 803 received a boost dose and 805 did not. As noted before, the risk of recurrence at 5 years was significantly lower with boosting, with 5-year free-from-local-recurrence rates of 97.1%, compared with 92.7% for patients who did not get a tumor-bed boost.

There were no significant differences according to fractionation schedule, however: among all randomly assigned patients the rate of 5-year freedom from recurrence was 94.9% for both the conventionally fractionated and hypofractionated WBI groups.

Not surprisingly, patients who received the boost dose had higher rates of grade 2 or greater toxicities, including breast pain (14% vs. 10%; P = .03) and induration (14% vs. 6%; P < .001).

The study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Susan G. Komen for the Cure, Breast Cancer Now, OncoSuisse, Dutch Cancer Society, and Canadian Cancer Trials Group. Dr. Chua disclosed grant support from the organizations and others.

Giving a boost radiation dose to the tumor bed following breast-conserving surgery and whole breast irradiation (WBI) has been shown to be effective at reducing recurrence of invasive breast cancer, and now a multinational randomized trial has shown that it can do the same for patients with non–low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

“ wrote the authors, led by Boon H. Chua, PhD, from the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Among 1,608 patients with DCIS with at least one clinical or pathological marker for increased risk of local recurrence, 5-year rates of freedom from local recurrence were 97.1% for patients assigned to received a tumor bed boost versus 92.7% for patients who did not receive a boost dose. This difference translated into a hazard ratio for recurrence with radiation boost of 0.47 (P < .001).

“Our results support the use of tumor-bed boost radiation after postoperative WBI in patients with non–low-risk DCIS to optimize local control, and the adoption of moderately hypofractionated whole breast irradiation in practice to improve the balance of local control, toxicity, and socioeconomic burdens of treatment,” the authors wrote in a study published in The Lancet.

The investigators, from cancer centers in Australia, Europe, and Canada, noted that the advent of screening mammography was followed by a substantial increase in the diagnosis of DCIS. They also noted that patients who undergo breast-conserving surgery for DCIS are at risk for local recurrence, and half of recurrences present as invasive disease.

In addition, they said, there were high recurrence rates in randomized clinical for patients with DCIS who received conventionally fractionated WBI without a tumor boost following surgery.

“Further, the inconvenience of a 5- to 6-week course of conventionally fractionated WBI decreased the quality of life of patients. Thus, tailoring radiation dose fractionation according to recurrence risk is a prominent controversy in the radiation treatment of DCIS,” they wrote.

Four-way trial

To see whether a tumor-bed boost following WBI and alternative WBI fractionation schedules could improve outcomes for patients with non–low-risk DCIS, the researchers enrolled patients and assigned them on an equal basis to one of four groups, in which they would receive either conventional or hypofractionated WBI with or without a tumor-bed boost.

The conventional WBI regimen consisted of a total of 50 Gy delivered over 25 fractions. The hypofractionated regimen consisted of a total dose of 42.5 Gy delivered in 16 fractions. Patients assigned to get a boost dose to the tumor bed received an additional 16 Gy in eight fractions after WBI.

Of the 1,608 patients enrolled who eligible for randomization, 803 received a boost dose and 805 did not. As noted before, the risk of recurrence at 5 years was significantly lower with boosting, with 5-year free-from-local-recurrence rates of 97.1%, compared with 92.7% for patients who did not get a tumor-bed boost.

There were no significant differences according to fractionation schedule, however: among all randomly assigned patients the rate of 5-year freedom from recurrence was 94.9% for both the conventionally fractionated and hypofractionated WBI groups.

Not surprisingly, patients who received the boost dose had higher rates of grade 2 or greater toxicities, including breast pain (14% vs. 10%; P = .03) and induration (14% vs. 6%; P < .001).

The study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Susan G. Komen for the Cure, Breast Cancer Now, OncoSuisse, Dutch Cancer Society, and Canadian Cancer Trials Group. Dr. Chua disclosed grant support from the organizations and others.

Giving a boost radiation dose to the tumor bed following breast-conserving surgery and whole breast irradiation (WBI) has been shown to be effective at reducing recurrence of invasive breast cancer, and now a multinational randomized trial has shown that it can do the same for patients with non–low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

“ wrote the authors, led by Boon H. Chua, PhD, from the University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Among 1,608 patients with DCIS with at least one clinical or pathological marker for increased risk of local recurrence, 5-year rates of freedom from local recurrence were 97.1% for patients assigned to received a tumor bed boost versus 92.7% for patients who did not receive a boost dose. This difference translated into a hazard ratio for recurrence with radiation boost of 0.47 (P < .001).

“Our results support the use of tumor-bed boost radiation after postoperative WBI in patients with non–low-risk DCIS to optimize local control, and the adoption of moderately hypofractionated whole breast irradiation in practice to improve the balance of local control, toxicity, and socioeconomic burdens of treatment,” the authors wrote in a study published in The Lancet.

The investigators, from cancer centers in Australia, Europe, and Canada, noted that the advent of screening mammography was followed by a substantial increase in the diagnosis of DCIS. They also noted that patients who undergo breast-conserving surgery for DCIS are at risk for local recurrence, and half of recurrences present as invasive disease.

In addition, they said, there were high recurrence rates in randomized clinical for patients with DCIS who received conventionally fractionated WBI without a tumor boost following surgery.

“Further, the inconvenience of a 5- to 6-week course of conventionally fractionated WBI decreased the quality of life of patients. Thus, tailoring radiation dose fractionation according to recurrence risk is a prominent controversy in the radiation treatment of DCIS,” they wrote.

Four-way trial

To see whether a tumor-bed boost following WBI and alternative WBI fractionation schedules could improve outcomes for patients with non–low-risk DCIS, the researchers enrolled patients and assigned them on an equal basis to one of four groups, in which they would receive either conventional or hypofractionated WBI with or without a tumor-bed boost.

The conventional WBI regimen consisted of a total of 50 Gy delivered over 25 fractions. The hypofractionated regimen consisted of a total dose of 42.5 Gy delivered in 16 fractions. Patients assigned to get a boost dose to the tumor bed received an additional 16 Gy in eight fractions after WBI.

Of the 1,608 patients enrolled who eligible for randomization, 803 received a boost dose and 805 did not. As noted before, the risk of recurrence at 5 years was significantly lower with boosting, with 5-year free-from-local-recurrence rates of 97.1%, compared with 92.7% for patients who did not get a tumor-bed boost.

There were no significant differences according to fractionation schedule, however: among all randomly assigned patients the rate of 5-year freedom from recurrence was 94.9% for both the conventionally fractionated and hypofractionated WBI groups.

Not surprisingly, patients who received the boost dose had higher rates of grade 2 or greater toxicities, including breast pain (14% vs. 10%; P = .03) and induration (14% vs. 6%; P < .001).

The study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Susan G. Komen for the Cure, Breast Cancer Now, OncoSuisse, Dutch Cancer Society, and Canadian Cancer Trials Group. Dr. Chua disclosed grant support from the organizations and others.

FROM THE LANCET

Fine-needle aspiration alternative allows closer look at pancreatic cystic lesions

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–guided through-the-needle biopsies (TTNBs) of pancreatic cystic lesions are sufficient for accurate molecular analysis, which offers a superior alternative to cyst fluid obtained via fine-needle aspiration, based on a prospective study.

For highest diagnostic clarity, next-generation sequencing (NGS) of TTNBs can be paired with histology, lead author Charlotte Vestrup Rift, MD, PhD, of Copenhagen University Hospital, and colleagues reported.

“The diagnostic algorithm for the management of [pancreatic cystic lesions] includes endoscopic ultrasound examination with aspiration of cyst fluid for cytology,” the investigators wrote in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. “However, the reported sensitivity of cytology is low [at 54%]. A new microforceps, introduced through a 19-gauge needle, has proven useful for procurement of [TTNBs] that represent both the epithelial and stromal component of the cyst wall. TTNBs have a high sensitivity of 86% for the diagnosis of mucinous cysts.”

Dr. Rift and colleagues evaluated the impact of introducing NGS to the diagnostic process. They noted that concomitant mutations in GNAS and KRAS are diagnostic for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), while other mutations have been linked with progression to cancer.

The study involved 101 patients with pancreatic cystic lesions larger than 15 mm in diameter, mean age of 68 years, among whom 91 had residual TTNBs available after microscopic analysis. These samples underwent a 51-gene NGS panel that included the “most prevalent hot-spot mutations.” Diagnoses were sorted into four categories: neoplastic cyst, mucinous cyst, IPMN, or serous cystic neoplasm.

The primary endpoint was diagnostic yield, both for molecular analysis of TTNBs and for molecular analysis plus histopathology of TTNBs. Sensitivity and specificity of NGS were also determined using histopathology as the gold standard.

Relying on NGS alone, diagnostic yields were 44.5% and 27.7% for detecting a mucinous cyst and determining type of cyst, respectively. These yields rose to 73.3% and 70.3%, respectively, when NGS was used with microscopic evaluation. Continuing with this combined approach, sensitivity and specificity were 83.7% and 81.8%, respectively, for the diagnosis of a mucinous cyst. Sensitivity and specificity were higher still, at 87.2% and 84.6%, respectively, for identifying IPMNs.

The adverse-event rate was 9.9%, with a risk of postprocedure acute pancreatitis of 8.9 % and procedure-associated intracystic bleeding of 3%, according to the authors.

Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size and the single-center design.

“TTNB-NGS is not sufficient as a stand-alone diagnostic tool as of yet but has a high diagnostic yield when combined with microscopic evaluation and subtyping by immunohistochemistry,” the investigators concluded. “The advantage of EUS-TTNB over EUS–[fine-needle aspiration] is the ability to perform detailed cyst subtyping and the high technical success rate of the procedure. ... However, the procedure comes with a risk of adverse events and thus should be offered to patients where the value of an exact diagnosis outweighs the risks.”

“Molecular subtyping is emerging as a useful clinical test for diagnosing pancreatic cysts,” said Margaret Geraldine Keane, MBBS, MSc, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, although she noted that NGS remains expensive and sporadically available, “which limits its clinical utility and incorporation into diagnostic algorithms for pancreatic cysts. In the future, as the cost of sequencing reduces, and availability improves, this may change.”

For now, Dr. Keane advised physicians to reserve molecular subtyping for cases in which “accurate cyst subtyping will change management ... or when other tests have not provided a clear diagnosis.”

She said the present study is valuable because better diagnostic tests are badly needed for patients with pancreatic cysts, considering the high rate of surgical overtreatment.

“Having more diagnostic tests, such as those described in this publication [to be used on their own or in combination] to decide which patients need surgery, is important,” Dr. Keane said who was not involved in the study.

Better diagnostic tests could also improve outcomes for patients with pancreatic cancer, she said, noting a 5-year survival rate of 10%.

“This outcome is in large part attributable to the late stage at which the majority of patients are diagnosed,” Dr. Keane said. “If patients can be diagnosed earlier, survival dramatically improves. Improvements in diagnostic tests for premalignant pancreatic cystic lesions are therefore vital.”

The study was supported by Rigshospitalets Research Foundation, The Novo Nordisk Foundation, The Danish Cancer Society, and others, although they did not have a role in conducting the study or preparing the manuscript. One investigator disclosed a relationship with MediGlobe. The other investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Keane disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–guided through-the-needle biopsies (TTNBs) of pancreatic cystic lesions are sufficient for accurate molecular analysis, which offers a superior alternative to cyst fluid obtained via fine-needle aspiration, based on a prospective study.

For highest diagnostic clarity, next-generation sequencing (NGS) of TTNBs can be paired with histology, lead author Charlotte Vestrup Rift, MD, PhD, of Copenhagen University Hospital, and colleagues reported.

“The diagnostic algorithm for the management of [pancreatic cystic lesions] includes endoscopic ultrasound examination with aspiration of cyst fluid for cytology,” the investigators wrote in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. “However, the reported sensitivity of cytology is low [at 54%]. A new microforceps, introduced through a 19-gauge needle, has proven useful for procurement of [TTNBs] that represent both the epithelial and stromal component of the cyst wall. TTNBs have a high sensitivity of 86% for the diagnosis of mucinous cysts.”

Dr. Rift and colleagues evaluated the impact of introducing NGS to the diagnostic process. They noted that concomitant mutations in GNAS and KRAS are diagnostic for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), while other mutations have been linked with progression to cancer.

The study involved 101 patients with pancreatic cystic lesions larger than 15 mm in diameter, mean age of 68 years, among whom 91 had residual TTNBs available after microscopic analysis. These samples underwent a 51-gene NGS panel that included the “most prevalent hot-spot mutations.” Diagnoses were sorted into four categories: neoplastic cyst, mucinous cyst, IPMN, or serous cystic neoplasm.

The primary endpoint was diagnostic yield, both for molecular analysis of TTNBs and for molecular analysis plus histopathology of TTNBs. Sensitivity and specificity of NGS were also determined using histopathology as the gold standard.

Relying on NGS alone, diagnostic yields were 44.5% and 27.7% for detecting a mucinous cyst and determining type of cyst, respectively. These yields rose to 73.3% and 70.3%, respectively, when NGS was used with microscopic evaluation. Continuing with this combined approach, sensitivity and specificity were 83.7% and 81.8%, respectively, for the diagnosis of a mucinous cyst. Sensitivity and specificity were higher still, at 87.2% and 84.6%, respectively, for identifying IPMNs.

The adverse-event rate was 9.9%, with a risk of postprocedure acute pancreatitis of 8.9 % and procedure-associated intracystic bleeding of 3%, according to the authors.

Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size and the single-center design.

“TTNB-NGS is not sufficient as a stand-alone diagnostic tool as of yet but has a high diagnostic yield when combined with microscopic evaluation and subtyping by immunohistochemistry,” the investigators concluded. “The advantage of EUS-TTNB over EUS–[fine-needle aspiration] is the ability to perform detailed cyst subtyping and the high technical success rate of the procedure. ... However, the procedure comes with a risk of adverse events and thus should be offered to patients where the value of an exact diagnosis outweighs the risks.”

“Molecular subtyping is emerging as a useful clinical test for diagnosing pancreatic cysts,” said Margaret Geraldine Keane, MBBS, MSc, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, although she noted that NGS remains expensive and sporadically available, “which limits its clinical utility and incorporation into diagnostic algorithms for pancreatic cysts. In the future, as the cost of sequencing reduces, and availability improves, this may change.”

For now, Dr. Keane advised physicians to reserve molecular subtyping for cases in which “accurate cyst subtyping will change management ... or when other tests have not provided a clear diagnosis.”

She said the present study is valuable because better diagnostic tests are badly needed for patients with pancreatic cysts, considering the high rate of surgical overtreatment.

“Having more diagnostic tests, such as those described in this publication [to be used on their own or in combination] to decide which patients need surgery, is important,” Dr. Keane said who was not involved in the study.

Better diagnostic tests could also improve outcomes for patients with pancreatic cancer, she said, noting a 5-year survival rate of 10%.

“This outcome is in large part attributable to the late stage at which the majority of patients are diagnosed,” Dr. Keane said. “If patients can be diagnosed earlier, survival dramatically improves. Improvements in diagnostic tests for premalignant pancreatic cystic lesions are therefore vital.”

The study was supported by Rigshospitalets Research Foundation, The Novo Nordisk Foundation, The Danish Cancer Society, and others, although they did not have a role in conducting the study or preparing the manuscript. One investigator disclosed a relationship with MediGlobe. The other investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Keane disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)–guided through-the-needle biopsies (TTNBs) of pancreatic cystic lesions are sufficient for accurate molecular analysis, which offers a superior alternative to cyst fluid obtained via fine-needle aspiration, based on a prospective study.

For highest diagnostic clarity, next-generation sequencing (NGS) of TTNBs can be paired with histology, lead author Charlotte Vestrup Rift, MD, PhD, of Copenhagen University Hospital, and colleagues reported.

“The diagnostic algorithm for the management of [pancreatic cystic lesions] includes endoscopic ultrasound examination with aspiration of cyst fluid for cytology,” the investigators wrote in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. “However, the reported sensitivity of cytology is low [at 54%]. A new microforceps, introduced through a 19-gauge needle, has proven useful for procurement of [TTNBs] that represent both the epithelial and stromal component of the cyst wall. TTNBs have a high sensitivity of 86% for the diagnosis of mucinous cysts.”

Dr. Rift and colleagues evaluated the impact of introducing NGS to the diagnostic process. They noted that concomitant mutations in GNAS and KRAS are diagnostic for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), while other mutations have been linked with progression to cancer.

The study involved 101 patients with pancreatic cystic lesions larger than 15 mm in diameter, mean age of 68 years, among whom 91 had residual TTNBs available after microscopic analysis. These samples underwent a 51-gene NGS panel that included the “most prevalent hot-spot mutations.” Diagnoses were sorted into four categories: neoplastic cyst, mucinous cyst, IPMN, or serous cystic neoplasm.

The primary endpoint was diagnostic yield, both for molecular analysis of TTNBs and for molecular analysis plus histopathology of TTNBs. Sensitivity and specificity of NGS were also determined using histopathology as the gold standard.

Relying on NGS alone, diagnostic yields were 44.5% and 27.7% for detecting a mucinous cyst and determining type of cyst, respectively. These yields rose to 73.3% and 70.3%, respectively, when NGS was used with microscopic evaluation. Continuing with this combined approach, sensitivity and specificity were 83.7% and 81.8%, respectively, for the diagnosis of a mucinous cyst. Sensitivity and specificity were higher still, at 87.2% and 84.6%, respectively, for identifying IPMNs.

The adverse-event rate was 9.9%, with a risk of postprocedure acute pancreatitis of 8.9 % and procedure-associated intracystic bleeding of 3%, according to the authors.

Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size and the single-center design.

“TTNB-NGS is not sufficient as a stand-alone diagnostic tool as of yet but has a high diagnostic yield when combined with microscopic evaluation and subtyping by immunohistochemistry,” the investigators concluded. “The advantage of EUS-TTNB over EUS–[fine-needle aspiration] is the ability to perform detailed cyst subtyping and the high technical success rate of the procedure. ... However, the procedure comes with a risk of adverse events and thus should be offered to patients where the value of an exact diagnosis outweighs the risks.”

“Molecular subtyping is emerging as a useful clinical test for diagnosing pancreatic cysts,” said Margaret Geraldine Keane, MBBS, MSc, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore, although she noted that NGS remains expensive and sporadically available, “which limits its clinical utility and incorporation into diagnostic algorithms for pancreatic cysts. In the future, as the cost of sequencing reduces, and availability improves, this may change.”

For now, Dr. Keane advised physicians to reserve molecular subtyping for cases in which “accurate cyst subtyping will change management ... or when other tests have not provided a clear diagnosis.”

She said the present study is valuable because better diagnostic tests are badly needed for patients with pancreatic cysts, considering the high rate of surgical overtreatment.

“Having more diagnostic tests, such as those described in this publication [to be used on their own or in combination] to decide which patients need surgery, is important,” Dr. Keane said who was not involved in the study.

Better diagnostic tests could also improve outcomes for patients with pancreatic cancer, she said, noting a 5-year survival rate of 10%.

“This outcome is in large part attributable to the late stage at which the majority of patients are diagnosed,” Dr. Keane said. “If patients can be diagnosed earlier, survival dramatically improves. Improvements in diagnostic tests for premalignant pancreatic cystic lesions are therefore vital.”

The study was supported by Rigshospitalets Research Foundation, The Novo Nordisk Foundation, The Danish Cancer Society, and others, although they did not have a role in conducting the study or preparing the manuscript. One investigator disclosed a relationship with MediGlobe. The other investigators reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Keane disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

Superolateral knee injection with a patellar tilt for osteoarthritis pain

Levels of West Nile virus higher than normal in northern Italy

Climate change has affected the spread of West Nile fever. This observation was confirmed in an Italian Ministry of Health note reporting 94 confirmed cases of infection. Of those cases, 55 were neuroinvasive, 19 were from blood donors, 19 were associated with fever, and in one case, the patient was symptomatic. Seven deaths have occurred since the start of the summer season, particularly in northern Italy.

Entomologists and veterinarians have confirmed the presence of West Nile virus (WNV) in a pool of 100 mosquitoes, 15 birds from targeted species, and 10 wild birds from passive surveillance. Four cases have been reported in horses in which clinical symptoms were attributable to a WNV infection. No cases of infection with Usutu virus (USUV) have been registered in humans. USUV is a virus in the same family as WNV. It was first identified in South Africa in the 1950s and is capable of causing encephalitis. The viral genome has been detected in a pool of 33 mosquitoes and four birds.

Currently, the regions where the circulation of WNV has been confirmed are Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, Piedmont, Lombardy, Sardinia, and Friuli Venezia Giulia. To date, USUV has been detected in Le Marche, Lombardy, Umbria, Emilia Romagna, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Lazio, and Veneto.