User login

Misoprostol: Clinical pharmacology in obstetrics and gynecology

Oxytocin and prostaglandins are critically important regulators of uterine contraction. Obstetrician-gynecologists commonly prescribe oxytocin and prostaglandin agonists (misoprostol, dinoprostone) to stimulate uterine contraction for the induction of labor, prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, and treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise. The focus of this editorial is the clinical pharmacology of misoprostol.

Misoprostol is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention and treatment of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced gastric ulcers and for patients at high risk for gastric ulcers, including those with a history of gastric ulcers. The approved misoprostol route and dose for this indication is oral administration of 200 µg four times daily with food.1 Recent food intake and antacid use reduces the absorption of orally administered misoprostol. There are no FDA-approved indications for the use of misoprostol as a single agent in obstetrics and gynecology. The FDA has approved the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol for medication abortion in the first trimester. In contrast to misoprostol, PGE2 (dinoprostone) is approved by the FDA as a vaginal insert containing 10 mg of dinoprostone for the initiation and/or continuation of cervical ripening in patients at or near term in whom there is a medical or obstetric indication for induction of labor (Cervidil; Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc, Parsippany, New Jersey).2

Pharmacology of misoprostol

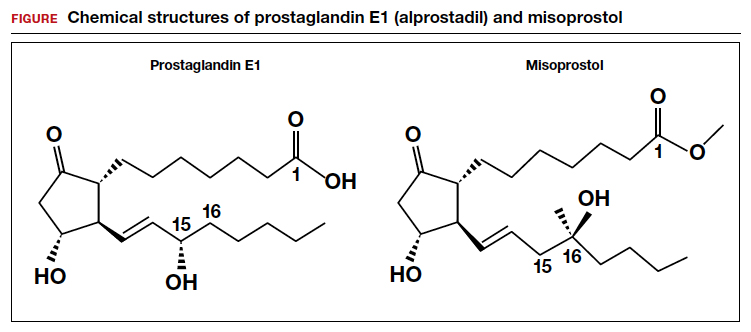

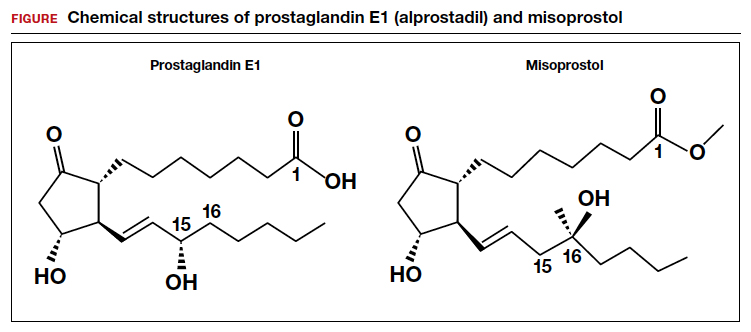

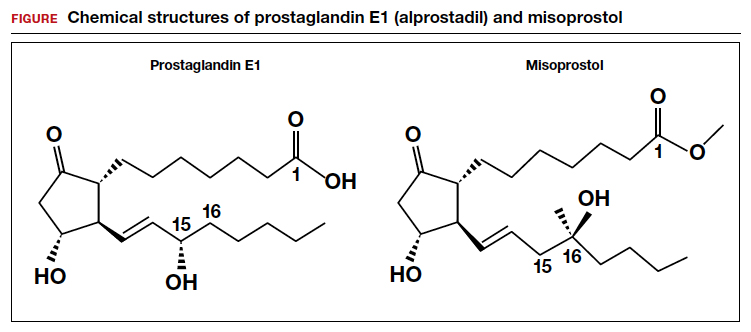

Misoprostol is a prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) agonist analogue. Prostaglandin E1 (alprostadil) is rapidly metabolized, has a half-life in the range of minutes and is not orally active, requiring administration by intravenous infusion or injection. It is indicated to maintain a patent ductus arteriosus in newborns with ductal-dependent circulation and to treat erectile dysfunction.3 In contrast to PGE1, misoprostol has a methyl ester group at carbon-1 (C-1) that increases potency and duration of action. Misoprostol also has no hydroxyl group at C-15, replacing that moiety with the addition of both a methyl- and hydroxyl- group at C-16 (FIGURE). These molecular changes improve oral activity and increase duration of action.4 Pure misoprostol is a viscous oil. It is formulated into tables by dispersing the oil on hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose before compounding into tablets. Unlike naturally occurring prostaglandins (PGE1), misoprostol tablets are stabile at room temperature for years.4

Following absorption, the methyl ester at C-1 is enzymatically cleaved, yielding misoprostol acid, the active drug.4 Misoprostol binds to the E prostanoid receptor 3 (EP-3).5 Activation of myometrial EP-3 receptor induces an increase in intracellular phosphoinositol turnover and calcium mobilization, resulting in an increase in intracellular-free calcium, triggering actin-myosin contractility.6 The increase in free calcium is propagated cell-to-cell through gap junctions that link the myometrial cells to facilitate the generation of a coordinated contraction.

Misoprostol: Various routes of administration are not equal

Misoprostol can be given by an oral, buccal, vaginal, or rectal route of administration. To study the effect of the route of administration on uterine tone and contractility, investigators randomly assigned patients at 8 to 11 weeks’ gestation to receive misoprostol 400 µg as a single dose by the oral or vaginal route. Uterine tone and contractility were measured using an intrauterine pressure transducer. Compared to vaginal administration, oral administration of misprostol was associated with rapid attainment of peak plasma level at 30 minutes, followed by a decline in concentration by 60 minutes. This rapid onset and rapid offset of plasma concentration was paralleled by the onset of uterine tone within 8 minutes, but surprisingly no sustained uterine contractions.7 By contrast, following vaginal administration of misoprostol, serum levels rose slowly and peaked in 1 to 2 hours. Uterine tone increased within 21 minutes, and sustained uterine contractions were recorded for 4 hours.7 The rapid rise and fall in plasma misoprostol following oral administration and the more sustained plasma misoprostol concentration over 4 hours has been previously reported.8 In a second study involving patients 8 to 11 weeks’ gestation, the effect of a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg by an oral or vaginal route on uterine contractility was compared using an intrauterine pressure transducer.9 Confirming previous results, the time from misoprostol administration to increased uterine tone was more rapid with oral than with vaginal administration (8 min vs 19 min). Over the course of 4 hours, uterine contraction activity was greater with vaginal than with oral administration (454 vs 166 Montevideo units).9

Both studies reported that oral administration of misoprostol resulted in more rapid onset and offset of action than vaginal administration. Oral administration of a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg did not result in sustained uterine contractions in most patients in the first trimester. Vaginal administration produced a slower onset of increased uterine tone but sustained uterine contractions over 4 hours. Compared with vaginal administration of misoprostol, the rapid onset and offset of action of oral misoprostol may reduce the rate of tachysystole and changes in fetal heart rate observed with vaginal administration.10

An important finding is that buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol have similar effects on uterine tone in the first trimester.11 To study the effect of buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine tone, patients 6 to 13 weeks’ gestation were randomly allocated to receive a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg by a buccal or vaginal route.11 Uterine activity over 5 hours following administration was assessed using an intrauterine pressure transducer. Uterine tone 20 to 30 minutes after buccal or vaginal administration of misoprostol (400 µg) was 27 and 28 mm Hg, respectively. Peak uterine tone, as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer, for buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol was 49 mm Hg and 54 mm Hg, respectively. Total Alexandria units (AU) over 5 hours following buccal or vaginal administration was 6,537 AU and 6,090 AU, respectively.11

An AU is calculated as the average amplitude of the contractions (mm Hg) multiplied by the average duration of the contractions (min) multiplied by average frequency of contraction over 10 minutes.12 By contrast, a Montevideo unit does not include an assessment of contraction duration and is calculated as average amplitude of contractions (mm Hg) multiplied by frequency of uterine contractions over 10 minutes.12

In contrast to buccal or vaginal administration, rectal administration of misoprostol resulted in much lower peak uterine tone and contractility as measured by a pressure transducer. Uterine tone 20 to 30 minutes after vaginal and rectal administration of misoprostol (400 µg) was 28 and 19 mm Hg, respectively.11 Peak uterine tone, as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer, for vaginal and rectal administration of misoprostol was 54 and 31 mm Hg, respectively. AUs over 5 hours following vaginal and rectal administration was 6,090 AU and 2,768 AU, respectively.11 Compared with buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol, rectal administration produced less sustained uterine contractions in the first trimester of pregnancy. To achieve maximal sustained uterine contractions, buccal and vaginal routes of administration are superior to oral and rectal administration.

Continue to: Misoprostol and cervical ripening...

Misoprostol and cervical ripening

Misoprostol is commonly used to soften and ripen the cervix. Some of the cervical ripening effects of misoprostol are likely due to increased uterine tone. In addition, misoprostol may have a direct effect on the collagen structure of the cervix. To study the effect of misoprostol on the cervix, pregnant patients in the first trimester were randomly assigned to receive misoprostol 200 µg by vaginal self-administration, isosorbide mononitrate (IMN) 40 mg by vaginal self-administration or no treatment the evening prior to pregnancy termination.13 The following day, before uterine evacuation, a cervical biopsy was obtained for electron microscopy studies and immunohistochemistry to assess the presence of enzymes involved in collagen degradation, including matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1) and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9). Electron microscopy demonstrated that pretreatment with misoprostol resulted in a pronounced splitting and disorganization of collagen fibers.13 Compared with misoprostol treatment, IMN produced less splitting and disorganization of collagen fibers, and in the no treatment group, no marked changes in the collagen framework were observed.

Compared with no treatment, misoprostol and IMN pretreatment were associated with marked increases in MMP-1 and MMP-9 as assessed by immunohistochemistry. Misoprostol pretreatment also resulted in a significant increase in interleukin-8 concentration compared with IMN pretreatment and no treatment (8.8 vs 2.7 vs 2.4 pg/mg tissue), respectively.13 Other investigators have also reported that misoprostol increased cervical leukocyte influx and collagen disrupting enzymes MMP-8 and MMP-9.14,15

An open-label clinical trial compared the efficacy of misoprostol versus Foley catheter for labor induction at term in 1,859 patients ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation with a Bishop score <6.16 Patients were randomly allocated to misoprostol (50 µg orally every 4 hours up to 3 times in 24 hours) versus placement of a 16 F or 18 F Foley catheter introduced through the cervix, filled with 30 mL of sodium chloride or water. The investigators reported that oral misoprostol and Foley catheter cervical ripening had similar safety and effectiveness for cervical ripening as a prelude to induction of labor, including no statistically significant differences in 5-minute Apgar score <7, umbilical cord artery pH ≤ 7.05, postpartum hemorrhage, or cesarean birth rate.16

Bottom line

Misoprostol and oxytocin are commonly prescribed in obstetric practice for cervical ripening and induction of labor, respectively. The dose and route of administration of misoprostol influences the effect on the uterus. For cervical ripening, where rapid onset and offset may help to reduce the risk of uterine tachysystole and worrisome fetal heart rate changes, low-dose (50 µg) oral administration of misoprostol may be a preferred dose and route. For the treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise, to stimulate sustained uterine contractions over many hours, buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol are preferred. Rectal administration is generally inferior to buccal and vaginal administration for stimulating sustained uterine contractions and its uses should be limited. ●

Common side effects of misoprostol are abdominal cramping, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, headache, and fever. Elevated temperature following misoprostol administration is a concerning side effect that may require further investigation to rule out an infection, especially if the elevated temperature persists for > 4 hours. The preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus (POAH) plays a major role in thermoregulation. When an infection causes an increase in endogenous pyrogens, including interleukin-1β, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor, prostaglandins are generated in the region of the POAH, increasing the thermoregulatory set point, triggering cutaneous vasoconstriction and shivering and non-shivering thermogenesis.1 Misoprostol, especially at doses >400 µg commonly causes both patient-reported chills and temperature elevation >38° C.

In a study comparing misoprostol and oxytocin for the management of the third stage of labor, 597 patients were randomly allocated to receive oxytocin 10 units by intramuscular injection or misoprostol 400 µg or 600 µg by the oral route.2 Patient-reported shivering occurred in 13%, 19%, and 28% of patients receiving oxytocin, misoprostol 400 µg and misoprostol 800 µg, respectively. A recorded temperature >38° C occurred within 1 hour of medication administration in approximately 3%, 2%, and 7.5% of patients receiving oxytocin, misoprostol 400 µg, and misoprostol 800 µg, respectively. In another study, 453 patients scheduled for a cesarean birth were randomly allocated to receive 1 of 3 doses of rectal misoprostol 200 μg, 400 μg, or 600 μg before incision. Fever was detected in 2.6%, 9.9%, and 5.1% of the patients receiving misoprostol 200 μg, 400 μg, or 600 μg, respectively.3

References

1. Aronoff DM, Neilson EG. Antipyretics: mechanisms of action and clinical use in fever suppression. Am J Med. 2001;111:304-315. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00834-8.

2. Lumbiganon P, Hofmeyr J, Gumezoglu AM, et al. Misoprostol dose-related shivering and pyrexia in the third stage of labor. WHO Collaborative Trial of Misoprostol in the Management of the Third Stage of Labor. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:304-308. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08266.x.

3. Sweed M, El-Said M, Abou-Gamrah AA, et al. Comparison between 200, 400 and 600 microgram rectal misoprostol before cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:585-591. doi: 10.1111 /jog.13883.

- Cytotec [package insert]. Chicago, IL: GD Searle & Co. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2002/19268slr037.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Cervidil [package insert]. St Louis, MO: Forrest Pharmaceuticals Inc.; May 2006. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Caverject [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc.; March 2014. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Collins PW. Misoprostol: discovery, development and clinical applications. Med Res Rev. 1990;10:149-172. doi: 10.1002/med.2610100202.

- Audit M, White KI, Breton B, et al. Crystal structure of misoprostol bound to the labor inducer prostaglandin E2 receptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15:11-17. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0160-y.

- Pallliser KH, Hirst JJ, Ooi G, et al. Prostaglandin E and F receptor expression and myometrial sensitivity in labor onset in the sheep. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:937-943. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.035311.

- Gemzell-Danilesson K, Marions L, Rodriguez A, et al. Comparison between oral and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine contractility. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:275-280. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00436-0.

- Zieman M, Fong SK, Benowitz NL, et al. Absorption kinetics of misoprostol with oral or vaginal administration. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:88-92. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00111-7.

- Aronsson A, Bygdeman M, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Effects of misoprostol on uterine contractility following different routes of administration. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:81-84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh005.

- Young DC, Delaney T, Armson BA, et al. Oral misoprostol, low dose vaginal misoprostol and vaginal dinoprostone for labor induction: randomized controlled trial. PLOS One. 2020;15:e0227245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227245.

- Meckstroth KR, Whitaker AK, Bertisch S, et al. Misoprostol administered by epithelial routes. Drug absorption and uterine response. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:582-590. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230398.32794.9d.

- el-Sahwi S, Gaafar AA, Toppozada HK. A new unit for evaluation of uterine activity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:900-903. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(67)90074-9.

- Vukas N, Ekerhovd E, Abrahamsson G, et al. Cervical priming in the first trimester: morphological and biochemical effects of misoprostol and isosorbide mononitrate. Acta Obstet Gyecol. 2009;88:43-51. doi: 10.1080/00016340802585440.

- Aronsson A, Ulfgren AK, Stabi B, et al. The effect of orally and vaginally administered misoprostol on inflammatory mediators and cervical ripening during early pregnancy. Contraception. 2005;72:33-39. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.02.012.

- Denison FC, Riley SC, Elliott CL, et al. The effect of mifepristone administration on leukocyte populations, matrix metalloproteinases and inflammatory mediators in the first trimester cervix. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:541-548. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.6.541.

- ten Eikelder MLG, Rengerink KO, Jozwiak M, et al. Induction of labour at term with oral misoprostol versus a Foley catheter (PROBAAT-II): a multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1619-1628. doi: 10.1016 /S0140-6736(16)00084-2.

Oxytocin and prostaglandins are critically important regulators of uterine contraction. Obstetrician-gynecologists commonly prescribe oxytocin and prostaglandin agonists (misoprostol, dinoprostone) to stimulate uterine contraction for the induction of labor, prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, and treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise. The focus of this editorial is the clinical pharmacology of misoprostol.

Misoprostol is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention and treatment of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced gastric ulcers and for patients at high risk for gastric ulcers, including those with a history of gastric ulcers. The approved misoprostol route and dose for this indication is oral administration of 200 µg four times daily with food.1 Recent food intake and antacid use reduces the absorption of orally administered misoprostol. There are no FDA-approved indications for the use of misoprostol as a single agent in obstetrics and gynecology. The FDA has approved the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol for medication abortion in the first trimester. In contrast to misoprostol, PGE2 (dinoprostone) is approved by the FDA as a vaginal insert containing 10 mg of dinoprostone for the initiation and/or continuation of cervical ripening in patients at or near term in whom there is a medical or obstetric indication for induction of labor (Cervidil; Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc, Parsippany, New Jersey).2

Pharmacology of misoprostol

Misoprostol is a prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) agonist analogue. Prostaglandin E1 (alprostadil) is rapidly metabolized, has a half-life in the range of minutes and is not orally active, requiring administration by intravenous infusion or injection. It is indicated to maintain a patent ductus arteriosus in newborns with ductal-dependent circulation and to treat erectile dysfunction.3 In contrast to PGE1, misoprostol has a methyl ester group at carbon-1 (C-1) that increases potency and duration of action. Misoprostol also has no hydroxyl group at C-15, replacing that moiety with the addition of both a methyl- and hydroxyl- group at C-16 (FIGURE). These molecular changes improve oral activity and increase duration of action.4 Pure misoprostol is a viscous oil. It is formulated into tables by dispersing the oil on hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose before compounding into tablets. Unlike naturally occurring prostaglandins (PGE1), misoprostol tablets are stabile at room temperature for years.4

Following absorption, the methyl ester at C-1 is enzymatically cleaved, yielding misoprostol acid, the active drug.4 Misoprostol binds to the E prostanoid receptor 3 (EP-3).5 Activation of myometrial EP-3 receptor induces an increase in intracellular phosphoinositol turnover and calcium mobilization, resulting in an increase in intracellular-free calcium, triggering actin-myosin contractility.6 The increase in free calcium is propagated cell-to-cell through gap junctions that link the myometrial cells to facilitate the generation of a coordinated contraction.

Misoprostol: Various routes of administration are not equal

Misoprostol can be given by an oral, buccal, vaginal, or rectal route of administration. To study the effect of the route of administration on uterine tone and contractility, investigators randomly assigned patients at 8 to 11 weeks’ gestation to receive misoprostol 400 µg as a single dose by the oral or vaginal route. Uterine tone and contractility were measured using an intrauterine pressure transducer. Compared to vaginal administration, oral administration of misprostol was associated with rapid attainment of peak plasma level at 30 minutes, followed by a decline in concentration by 60 minutes. This rapid onset and rapid offset of plasma concentration was paralleled by the onset of uterine tone within 8 minutes, but surprisingly no sustained uterine contractions.7 By contrast, following vaginal administration of misoprostol, serum levels rose slowly and peaked in 1 to 2 hours. Uterine tone increased within 21 minutes, and sustained uterine contractions were recorded for 4 hours.7 The rapid rise and fall in plasma misoprostol following oral administration and the more sustained plasma misoprostol concentration over 4 hours has been previously reported.8 In a second study involving patients 8 to 11 weeks’ gestation, the effect of a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg by an oral or vaginal route on uterine contractility was compared using an intrauterine pressure transducer.9 Confirming previous results, the time from misoprostol administration to increased uterine tone was more rapid with oral than with vaginal administration (8 min vs 19 min). Over the course of 4 hours, uterine contraction activity was greater with vaginal than with oral administration (454 vs 166 Montevideo units).9

Both studies reported that oral administration of misoprostol resulted in more rapid onset and offset of action than vaginal administration. Oral administration of a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg did not result in sustained uterine contractions in most patients in the first trimester. Vaginal administration produced a slower onset of increased uterine tone but sustained uterine contractions over 4 hours. Compared with vaginal administration of misoprostol, the rapid onset and offset of action of oral misoprostol may reduce the rate of tachysystole and changes in fetal heart rate observed with vaginal administration.10

An important finding is that buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol have similar effects on uterine tone in the first trimester.11 To study the effect of buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine tone, patients 6 to 13 weeks’ gestation were randomly allocated to receive a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg by a buccal or vaginal route.11 Uterine activity over 5 hours following administration was assessed using an intrauterine pressure transducer. Uterine tone 20 to 30 minutes after buccal or vaginal administration of misoprostol (400 µg) was 27 and 28 mm Hg, respectively. Peak uterine tone, as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer, for buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol was 49 mm Hg and 54 mm Hg, respectively. Total Alexandria units (AU) over 5 hours following buccal or vaginal administration was 6,537 AU and 6,090 AU, respectively.11

An AU is calculated as the average amplitude of the contractions (mm Hg) multiplied by the average duration of the contractions (min) multiplied by average frequency of contraction over 10 minutes.12 By contrast, a Montevideo unit does not include an assessment of contraction duration and is calculated as average amplitude of contractions (mm Hg) multiplied by frequency of uterine contractions over 10 minutes.12

In contrast to buccal or vaginal administration, rectal administration of misoprostol resulted in much lower peak uterine tone and contractility as measured by a pressure transducer. Uterine tone 20 to 30 minutes after vaginal and rectal administration of misoprostol (400 µg) was 28 and 19 mm Hg, respectively.11 Peak uterine tone, as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer, for vaginal and rectal administration of misoprostol was 54 and 31 mm Hg, respectively. AUs over 5 hours following vaginal and rectal administration was 6,090 AU and 2,768 AU, respectively.11 Compared with buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol, rectal administration produced less sustained uterine contractions in the first trimester of pregnancy. To achieve maximal sustained uterine contractions, buccal and vaginal routes of administration are superior to oral and rectal administration.

Continue to: Misoprostol and cervical ripening...

Misoprostol and cervical ripening

Misoprostol is commonly used to soften and ripen the cervix. Some of the cervical ripening effects of misoprostol are likely due to increased uterine tone. In addition, misoprostol may have a direct effect on the collagen structure of the cervix. To study the effect of misoprostol on the cervix, pregnant patients in the first trimester were randomly assigned to receive misoprostol 200 µg by vaginal self-administration, isosorbide mononitrate (IMN) 40 mg by vaginal self-administration or no treatment the evening prior to pregnancy termination.13 The following day, before uterine evacuation, a cervical biopsy was obtained for electron microscopy studies and immunohistochemistry to assess the presence of enzymes involved in collagen degradation, including matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1) and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9). Electron microscopy demonstrated that pretreatment with misoprostol resulted in a pronounced splitting and disorganization of collagen fibers.13 Compared with misoprostol treatment, IMN produced less splitting and disorganization of collagen fibers, and in the no treatment group, no marked changes in the collagen framework were observed.

Compared with no treatment, misoprostol and IMN pretreatment were associated with marked increases in MMP-1 and MMP-9 as assessed by immunohistochemistry. Misoprostol pretreatment also resulted in a significant increase in interleukin-8 concentration compared with IMN pretreatment and no treatment (8.8 vs 2.7 vs 2.4 pg/mg tissue), respectively.13 Other investigators have also reported that misoprostol increased cervical leukocyte influx and collagen disrupting enzymes MMP-8 and MMP-9.14,15

An open-label clinical trial compared the efficacy of misoprostol versus Foley catheter for labor induction at term in 1,859 patients ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation with a Bishop score <6.16 Patients were randomly allocated to misoprostol (50 µg orally every 4 hours up to 3 times in 24 hours) versus placement of a 16 F or 18 F Foley catheter introduced through the cervix, filled with 30 mL of sodium chloride or water. The investigators reported that oral misoprostol and Foley catheter cervical ripening had similar safety and effectiveness for cervical ripening as a prelude to induction of labor, including no statistically significant differences in 5-minute Apgar score <7, umbilical cord artery pH ≤ 7.05, postpartum hemorrhage, or cesarean birth rate.16

Bottom line

Misoprostol and oxytocin are commonly prescribed in obstetric practice for cervical ripening and induction of labor, respectively. The dose and route of administration of misoprostol influences the effect on the uterus. For cervical ripening, where rapid onset and offset may help to reduce the risk of uterine tachysystole and worrisome fetal heart rate changes, low-dose (50 µg) oral administration of misoprostol may be a preferred dose and route. For the treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise, to stimulate sustained uterine contractions over many hours, buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol are preferred. Rectal administration is generally inferior to buccal and vaginal administration for stimulating sustained uterine contractions and its uses should be limited. ●

Common side effects of misoprostol are abdominal cramping, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, headache, and fever. Elevated temperature following misoprostol administration is a concerning side effect that may require further investigation to rule out an infection, especially if the elevated temperature persists for > 4 hours. The preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus (POAH) plays a major role in thermoregulation. When an infection causes an increase in endogenous pyrogens, including interleukin-1β, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor, prostaglandins are generated in the region of the POAH, increasing the thermoregulatory set point, triggering cutaneous vasoconstriction and shivering and non-shivering thermogenesis.1 Misoprostol, especially at doses >400 µg commonly causes both patient-reported chills and temperature elevation >38° C.

In a study comparing misoprostol and oxytocin for the management of the third stage of labor, 597 patients were randomly allocated to receive oxytocin 10 units by intramuscular injection or misoprostol 400 µg or 600 µg by the oral route.2 Patient-reported shivering occurred in 13%, 19%, and 28% of patients receiving oxytocin, misoprostol 400 µg and misoprostol 800 µg, respectively. A recorded temperature >38° C occurred within 1 hour of medication administration in approximately 3%, 2%, and 7.5% of patients receiving oxytocin, misoprostol 400 µg, and misoprostol 800 µg, respectively. In another study, 453 patients scheduled for a cesarean birth were randomly allocated to receive 1 of 3 doses of rectal misoprostol 200 μg, 400 μg, or 600 μg before incision. Fever was detected in 2.6%, 9.9%, and 5.1% of the patients receiving misoprostol 200 μg, 400 μg, or 600 μg, respectively.3

References

1. Aronoff DM, Neilson EG. Antipyretics: mechanisms of action and clinical use in fever suppression. Am J Med. 2001;111:304-315. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00834-8.

2. Lumbiganon P, Hofmeyr J, Gumezoglu AM, et al. Misoprostol dose-related shivering and pyrexia in the third stage of labor. WHO Collaborative Trial of Misoprostol in the Management of the Third Stage of Labor. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:304-308. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08266.x.

3. Sweed M, El-Said M, Abou-Gamrah AA, et al. Comparison between 200, 400 and 600 microgram rectal misoprostol before cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:585-591. doi: 10.1111 /jog.13883.

Oxytocin and prostaglandins are critically important regulators of uterine contraction. Obstetrician-gynecologists commonly prescribe oxytocin and prostaglandin agonists (misoprostol, dinoprostone) to stimulate uterine contraction for the induction of labor, prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, and treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise. The focus of this editorial is the clinical pharmacology of misoprostol.

Misoprostol is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention and treatment of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced gastric ulcers and for patients at high risk for gastric ulcers, including those with a history of gastric ulcers. The approved misoprostol route and dose for this indication is oral administration of 200 µg four times daily with food.1 Recent food intake and antacid use reduces the absorption of orally administered misoprostol. There are no FDA-approved indications for the use of misoprostol as a single agent in obstetrics and gynecology. The FDA has approved the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol for medication abortion in the first trimester. In contrast to misoprostol, PGE2 (dinoprostone) is approved by the FDA as a vaginal insert containing 10 mg of dinoprostone for the initiation and/or continuation of cervical ripening in patients at or near term in whom there is a medical or obstetric indication for induction of labor (Cervidil; Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc, Parsippany, New Jersey).2

Pharmacology of misoprostol

Misoprostol is a prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) agonist analogue. Prostaglandin E1 (alprostadil) is rapidly metabolized, has a half-life in the range of minutes and is not orally active, requiring administration by intravenous infusion or injection. It is indicated to maintain a patent ductus arteriosus in newborns with ductal-dependent circulation and to treat erectile dysfunction.3 In contrast to PGE1, misoprostol has a methyl ester group at carbon-1 (C-1) that increases potency and duration of action. Misoprostol also has no hydroxyl group at C-15, replacing that moiety with the addition of both a methyl- and hydroxyl- group at C-16 (FIGURE). These molecular changes improve oral activity and increase duration of action.4 Pure misoprostol is a viscous oil. It is formulated into tables by dispersing the oil on hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose before compounding into tablets. Unlike naturally occurring prostaglandins (PGE1), misoprostol tablets are stabile at room temperature for years.4

Following absorption, the methyl ester at C-1 is enzymatically cleaved, yielding misoprostol acid, the active drug.4 Misoprostol binds to the E prostanoid receptor 3 (EP-3).5 Activation of myometrial EP-3 receptor induces an increase in intracellular phosphoinositol turnover and calcium mobilization, resulting in an increase in intracellular-free calcium, triggering actin-myosin contractility.6 The increase in free calcium is propagated cell-to-cell through gap junctions that link the myometrial cells to facilitate the generation of a coordinated contraction.

Misoprostol: Various routes of administration are not equal

Misoprostol can be given by an oral, buccal, vaginal, or rectal route of administration. To study the effect of the route of administration on uterine tone and contractility, investigators randomly assigned patients at 8 to 11 weeks’ gestation to receive misoprostol 400 µg as a single dose by the oral or vaginal route. Uterine tone and contractility were measured using an intrauterine pressure transducer. Compared to vaginal administration, oral administration of misprostol was associated with rapid attainment of peak plasma level at 30 minutes, followed by a decline in concentration by 60 minutes. This rapid onset and rapid offset of plasma concentration was paralleled by the onset of uterine tone within 8 minutes, but surprisingly no sustained uterine contractions.7 By contrast, following vaginal administration of misoprostol, serum levels rose slowly and peaked in 1 to 2 hours. Uterine tone increased within 21 minutes, and sustained uterine contractions were recorded for 4 hours.7 The rapid rise and fall in plasma misoprostol following oral administration and the more sustained plasma misoprostol concentration over 4 hours has been previously reported.8 In a second study involving patients 8 to 11 weeks’ gestation, the effect of a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg by an oral or vaginal route on uterine contractility was compared using an intrauterine pressure transducer.9 Confirming previous results, the time from misoprostol administration to increased uterine tone was more rapid with oral than with vaginal administration (8 min vs 19 min). Over the course of 4 hours, uterine contraction activity was greater with vaginal than with oral administration (454 vs 166 Montevideo units).9

Both studies reported that oral administration of misoprostol resulted in more rapid onset and offset of action than vaginal administration. Oral administration of a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg did not result in sustained uterine contractions in most patients in the first trimester. Vaginal administration produced a slower onset of increased uterine tone but sustained uterine contractions over 4 hours. Compared with vaginal administration of misoprostol, the rapid onset and offset of action of oral misoprostol may reduce the rate of tachysystole and changes in fetal heart rate observed with vaginal administration.10

An important finding is that buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol have similar effects on uterine tone in the first trimester.11 To study the effect of buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine tone, patients 6 to 13 weeks’ gestation were randomly allocated to receive a single dose of misoprostol 400 µg by a buccal or vaginal route.11 Uterine activity over 5 hours following administration was assessed using an intrauterine pressure transducer. Uterine tone 20 to 30 minutes after buccal or vaginal administration of misoprostol (400 µg) was 27 and 28 mm Hg, respectively. Peak uterine tone, as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer, for buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol was 49 mm Hg and 54 mm Hg, respectively. Total Alexandria units (AU) over 5 hours following buccal or vaginal administration was 6,537 AU and 6,090 AU, respectively.11

An AU is calculated as the average amplitude of the contractions (mm Hg) multiplied by the average duration of the contractions (min) multiplied by average frequency of contraction over 10 minutes.12 By contrast, a Montevideo unit does not include an assessment of contraction duration and is calculated as average amplitude of contractions (mm Hg) multiplied by frequency of uterine contractions over 10 minutes.12

In contrast to buccal or vaginal administration, rectal administration of misoprostol resulted in much lower peak uterine tone and contractility as measured by a pressure transducer. Uterine tone 20 to 30 minutes after vaginal and rectal administration of misoprostol (400 µg) was 28 and 19 mm Hg, respectively.11 Peak uterine tone, as measured by an intrauterine pressure transducer, for vaginal and rectal administration of misoprostol was 54 and 31 mm Hg, respectively. AUs over 5 hours following vaginal and rectal administration was 6,090 AU and 2,768 AU, respectively.11 Compared with buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol, rectal administration produced less sustained uterine contractions in the first trimester of pregnancy. To achieve maximal sustained uterine contractions, buccal and vaginal routes of administration are superior to oral and rectal administration.

Continue to: Misoprostol and cervical ripening...

Misoprostol and cervical ripening

Misoprostol is commonly used to soften and ripen the cervix. Some of the cervical ripening effects of misoprostol are likely due to increased uterine tone. In addition, misoprostol may have a direct effect on the collagen structure of the cervix. To study the effect of misoprostol on the cervix, pregnant patients in the first trimester were randomly assigned to receive misoprostol 200 µg by vaginal self-administration, isosorbide mononitrate (IMN) 40 mg by vaginal self-administration or no treatment the evening prior to pregnancy termination.13 The following day, before uterine evacuation, a cervical biopsy was obtained for electron microscopy studies and immunohistochemistry to assess the presence of enzymes involved in collagen degradation, including matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1) and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9). Electron microscopy demonstrated that pretreatment with misoprostol resulted in a pronounced splitting and disorganization of collagen fibers.13 Compared with misoprostol treatment, IMN produced less splitting and disorganization of collagen fibers, and in the no treatment group, no marked changes in the collagen framework were observed.

Compared with no treatment, misoprostol and IMN pretreatment were associated with marked increases in MMP-1 and MMP-9 as assessed by immunohistochemistry. Misoprostol pretreatment also resulted in a significant increase in interleukin-8 concentration compared with IMN pretreatment and no treatment (8.8 vs 2.7 vs 2.4 pg/mg tissue), respectively.13 Other investigators have also reported that misoprostol increased cervical leukocyte influx and collagen disrupting enzymes MMP-8 and MMP-9.14,15

An open-label clinical trial compared the efficacy of misoprostol versus Foley catheter for labor induction at term in 1,859 patients ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation with a Bishop score <6.16 Patients were randomly allocated to misoprostol (50 µg orally every 4 hours up to 3 times in 24 hours) versus placement of a 16 F or 18 F Foley catheter introduced through the cervix, filled with 30 mL of sodium chloride or water. The investigators reported that oral misoprostol and Foley catheter cervical ripening had similar safety and effectiveness for cervical ripening as a prelude to induction of labor, including no statistically significant differences in 5-minute Apgar score <7, umbilical cord artery pH ≤ 7.05, postpartum hemorrhage, or cesarean birth rate.16

Bottom line

Misoprostol and oxytocin are commonly prescribed in obstetric practice for cervical ripening and induction of labor, respectively. The dose and route of administration of misoprostol influences the effect on the uterus. For cervical ripening, where rapid onset and offset may help to reduce the risk of uterine tachysystole and worrisome fetal heart rate changes, low-dose (50 µg) oral administration of misoprostol may be a preferred dose and route. For the treatment of miscarriage and fetal demise, to stimulate sustained uterine contractions over many hours, buccal and vaginal administration of misoprostol are preferred. Rectal administration is generally inferior to buccal and vaginal administration for stimulating sustained uterine contractions and its uses should be limited. ●

Common side effects of misoprostol are abdominal cramping, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, headache, and fever. Elevated temperature following misoprostol administration is a concerning side effect that may require further investigation to rule out an infection, especially if the elevated temperature persists for > 4 hours. The preoptic area of the anterior hypothalamus (POAH) plays a major role in thermoregulation. When an infection causes an increase in endogenous pyrogens, including interleukin-1β, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor, prostaglandins are generated in the region of the POAH, increasing the thermoregulatory set point, triggering cutaneous vasoconstriction and shivering and non-shivering thermogenesis.1 Misoprostol, especially at doses >400 µg commonly causes both patient-reported chills and temperature elevation >38° C.

In a study comparing misoprostol and oxytocin for the management of the third stage of labor, 597 patients were randomly allocated to receive oxytocin 10 units by intramuscular injection or misoprostol 400 µg or 600 µg by the oral route.2 Patient-reported shivering occurred in 13%, 19%, and 28% of patients receiving oxytocin, misoprostol 400 µg and misoprostol 800 µg, respectively. A recorded temperature >38° C occurred within 1 hour of medication administration in approximately 3%, 2%, and 7.5% of patients receiving oxytocin, misoprostol 400 µg, and misoprostol 800 µg, respectively. In another study, 453 patients scheduled for a cesarean birth were randomly allocated to receive 1 of 3 doses of rectal misoprostol 200 μg, 400 μg, or 600 μg before incision. Fever was detected in 2.6%, 9.9%, and 5.1% of the patients receiving misoprostol 200 μg, 400 μg, or 600 μg, respectively.3

References

1. Aronoff DM, Neilson EG. Antipyretics: mechanisms of action and clinical use in fever suppression. Am J Med. 2001;111:304-315. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00834-8.

2. Lumbiganon P, Hofmeyr J, Gumezoglu AM, et al. Misoprostol dose-related shivering and pyrexia in the third stage of labor. WHO Collaborative Trial of Misoprostol in the Management of the Third Stage of Labor. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:304-308. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08266.x.

3. Sweed M, El-Said M, Abou-Gamrah AA, et al. Comparison between 200, 400 and 600 microgram rectal misoprostol before cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:585-591. doi: 10.1111 /jog.13883.

- Cytotec [package insert]. Chicago, IL: GD Searle & Co. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2002/19268slr037.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Cervidil [package insert]. St Louis, MO: Forrest Pharmaceuticals Inc.; May 2006. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Caverject [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc.; March 2014. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Collins PW. Misoprostol: discovery, development and clinical applications. Med Res Rev. 1990;10:149-172. doi: 10.1002/med.2610100202.

- Audit M, White KI, Breton B, et al. Crystal structure of misoprostol bound to the labor inducer prostaglandin E2 receptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15:11-17. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0160-y.

- Pallliser KH, Hirst JJ, Ooi G, et al. Prostaglandin E and F receptor expression and myometrial sensitivity in labor onset in the sheep. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:937-943. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.035311.

- Gemzell-Danilesson K, Marions L, Rodriguez A, et al. Comparison between oral and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine contractility. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:275-280. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00436-0.

- Zieman M, Fong SK, Benowitz NL, et al. Absorption kinetics of misoprostol with oral or vaginal administration. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:88-92. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00111-7.

- Aronsson A, Bygdeman M, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Effects of misoprostol on uterine contractility following different routes of administration. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:81-84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh005.

- Young DC, Delaney T, Armson BA, et al. Oral misoprostol, low dose vaginal misoprostol and vaginal dinoprostone for labor induction: randomized controlled trial. PLOS One. 2020;15:e0227245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227245.

- Meckstroth KR, Whitaker AK, Bertisch S, et al. Misoprostol administered by epithelial routes. Drug absorption and uterine response. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:582-590. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230398.32794.9d.

- el-Sahwi S, Gaafar AA, Toppozada HK. A new unit for evaluation of uterine activity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:900-903. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(67)90074-9.

- Vukas N, Ekerhovd E, Abrahamsson G, et al. Cervical priming in the first trimester: morphological and biochemical effects of misoprostol and isosorbide mononitrate. Acta Obstet Gyecol. 2009;88:43-51. doi: 10.1080/00016340802585440.

- Aronsson A, Ulfgren AK, Stabi B, et al. The effect of orally and vaginally administered misoprostol on inflammatory mediators and cervical ripening during early pregnancy. Contraception. 2005;72:33-39. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.02.012.

- Denison FC, Riley SC, Elliott CL, et al. The effect of mifepristone administration on leukocyte populations, matrix metalloproteinases and inflammatory mediators in the first trimester cervix. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:541-548. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.6.541.

- ten Eikelder MLG, Rengerink KO, Jozwiak M, et al. Induction of labour at term with oral misoprostol versus a Foley catheter (PROBAAT-II): a multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1619-1628. doi: 10.1016 /S0140-6736(16)00084-2.

- Cytotec [package insert]. Chicago, IL: GD Searle & Co. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2002/19268slr037.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Cervidil [package insert]. St Louis, MO: Forrest Pharmaceuticals Inc.; May 2006. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Caverject [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc.; March 2014. Accessed June 20, 2022.

- Collins PW. Misoprostol: discovery, development and clinical applications. Med Res Rev. 1990;10:149-172. doi: 10.1002/med.2610100202.

- Audit M, White KI, Breton B, et al. Crystal structure of misoprostol bound to the labor inducer prostaglandin E2 receptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15:11-17. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0160-y.

- Pallliser KH, Hirst JJ, Ooi G, et al. Prostaglandin E and F receptor expression and myometrial sensitivity in labor onset in the sheep. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:937-943. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.035311.

- Gemzell-Danilesson K, Marions L, Rodriguez A, et al. Comparison between oral and vaginal administration of misoprostol on uterine contractility. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:275-280. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00436-0.

- Zieman M, Fong SK, Benowitz NL, et al. Absorption kinetics of misoprostol with oral or vaginal administration. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:88-92. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00111-7.

- Aronsson A, Bygdeman M, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Effects of misoprostol on uterine contractility following different routes of administration. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:81-84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh005.

- Young DC, Delaney T, Armson BA, et al. Oral misoprostol, low dose vaginal misoprostol and vaginal dinoprostone for labor induction: randomized controlled trial. PLOS One. 2020;15:e0227245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227245.

- Meckstroth KR, Whitaker AK, Bertisch S, et al. Misoprostol administered by epithelial routes. Drug absorption and uterine response. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:582-590. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230398.32794.9d.

- el-Sahwi S, Gaafar AA, Toppozada HK. A new unit for evaluation of uterine activity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:900-903. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(67)90074-9.

- Vukas N, Ekerhovd E, Abrahamsson G, et al. Cervical priming in the first trimester: morphological and biochemical effects of misoprostol and isosorbide mononitrate. Acta Obstet Gyecol. 2009;88:43-51. doi: 10.1080/00016340802585440.

- Aronsson A, Ulfgren AK, Stabi B, et al. The effect of orally and vaginally administered misoprostol on inflammatory mediators and cervical ripening during early pregnancy. Contraception. 2005;72:33-39. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.02.012.

- Denison FC, Riley SC, Elliott CL, et al. The effect of mifepristone administration on leukocyte populations, matrix metalloproteinases and inflammatory mediators in the first trimester cervix. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:541-548. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.6.541.

- ten Eikelder MLG, Rengerink KO, Jozwiak M, et al. Induction of labour at term with oral misoprostol versus a Foley catheter (PROBAAT-II): a multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1619-1628. doi: 10.1016 /S0140-6736(16)00084-2.

Appropriate antibiotic selection for 12 common infections in obstetric patients

For the infections we most commonly encounter in obstetric practice, I review in this article the selection of specific antibiotics. I focus on the key pathogens that cause these infections, the most useful diagnostic tests, and the most cost-effective antibiotic therapy. Relative cost estimates (high vs low) for drugs are based on information published on the GoodRx website (https://www.goodrx.com/). Actual charges to patients, of course, may vary widely depending on contractual relationships between hospitals, insurance companies, and wholesale vendors. The infections are listed in alphabetical order, not in order of frequency or severity.

1. Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a polymicrobial infection that results from perturbation of the normal vaginal flora due to conditions such as pregnancy, hormonal therapy, and changes in the menstrual cycle. It is characterized by a decrease in the vaginal concentration of Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by an increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus species, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.1,2

BV is characterized by a thin, white-gray malodorous (fishlike smell) discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5. Clue cells are apparent on saline microscopy, and the whiff (amine) test is positive when potassium hydroxide is added to a drop of vaginal secretions. Diagnostic accuracy can be improved using one of the new vaginal panel assays such as BD MAX Vaginal Panel (Becton, Dickinson and Company).3

Antibiotic selection

Antibiotic treatment of BV is directed primarily at the anaerobic component of the infection. The preferred treatment is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. If the patient cannot tolerate metronidazole, oral clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 days, can be used, although it is more expensive than metronidazole. Topical metronidazole vaginal gel (0.75%), 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is effective in treating the local vaginal infection, but it is not effective in preventing systemic complications such as preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, and puerperal endometritis.2 It also is significantly more expensive than the oral formulation of metronidazole. Topical clindamycin cream, 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is even more expensive.

Tinidazole 2 g orally daily for 2 days is an effective alternative to oral metronidazole. Single-dose therapy with oral secnidazole (2 g), a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, has been effective in small studies, but experience with this drug in the United States is limited. Secnidazole is also very expensive.4

2. Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis usually is caused by Candida albicans. Other less common species include C tropicalis, C glabrata, C auris, C lusitaniae, and C krusei. The most common clinical findings are vulvovaginal pruritus in association with a curdlike white vaginal discharge. The diagnosis can be established by confirmation of a normal vaginal pH and identification of budding yeast and hyphae on a potassium hydroxide preparation. As noted above for BV, the vaginal panel assay improves the accuracy of clinical diagnosis.3 Culture usually is indicated only in patients with infections that are refractory to therapy.

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

In the first trimester of pregnancy, vulvovaginal candidiasis should be treated with a topical medication such as clotrimazole cream 1% (50 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), miconazole cream 2% (100 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), or terconazole cream 0.4% (50 g intravaginally daily for 7 days). Single-dose formulations or 3-day courses of treatment may not be quite as effective in pregnant patients, but they do offer a more convenient dosing schedule.2,5

Oral fluconazole should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion and with fetal cardiac septal defects. Beyond the first trimester, oral fluconazole offers an attractive option for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The appropriate dose is 150 mg initially, with a repeat dose in 3 days if symptoms persist.2,5

Ibrexafungerp (300 mg twice daily for 1 day) was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for oral treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. However, this drug is teratogenic and is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation. It also is significantly more expensive than fluconazole.6

3. Cesarean delivery prophylaxis

All women having a cesarean delivery (CD) should receive antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce the risk of endometritis and wound infection.

Antibiotic selection

In my opinion, the preferred regimen is intravenous cefazolin 2 g plus azithromycin 500 mg administered preoperatively.7 Cefazolin can be administered in a rapid bolus; azithromycin should be administered over 1 hour.

In an exceptionally rigorous investigation called the C/SOAP trial (Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis trial), Tita and colleagues showed that the combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin was superior to single-agent prophylaxis (usually with cefazolin) in preventing the composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection occurring within 6 weeks of surgery.8 The additive effect of azithromycin was particularly pronounced in patients having CD after labor and rupture of membranes. Harper and associates subsequently validated the cost-effectiveness of this combination regimen using a decision analytic model.9

If the patient has a serious allergy to β-lactam antibiotics, the best alternative regimen for prophylaxis is clindamycin plus gentamicin. The appropriate single intravenous dose of clindamycin is 900 mg; the single dose of gentamicin should be 5 mg/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).7

4. Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium. In pregnant women, it typically causes urethritis, endocervicitis, and inflammatory proctitis. Along with gonorrhea, it is the cause of an unusual infection/inflammation of the liver capsule, termed Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (perihepatitis). The diagnosis of chlamydia infection is best confirmed with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). The NAAT simultaneously tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea in urine or in secretions obtained from the urethra, endocervix, and rectum.2

Antibiotic selection

The drug of choice for treating chlamydia in pregnancy is azithromycin 1,000 mg orally in a single dose. Erythromycin can be used as an alternative to azithromycin, but it usually is not well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. In my practice, the preferred alternative for a patient who cannot tolerate azithromycin is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.2,10

Continue to: 5. Chorioamnionitis...

5. Chorioamnionitis

Chorioamnionitis is a polymicrobial infection caused by anaerobes, aerobic gram-negative bacilli (predominantly Escherichia coli), and aerobic gram-positive cocci (primarily group B streptococci [GBS]). The diagnosis usually is made based on clinical examination: maternal fever, maternal and fetal tachycardia, and no other localizing sign of infection. The diagnosis can be confirmed by obtaining a sample of amniotic fluid via amniocentesis or via aspiration through the intrauterine pressure catheter and demonstrating a positive Gram stain, low glucose concentration (<20 mg/dL), positive nitrites, positive leukocyte esterase, and ultimately, a positive bacteriologic culture.2

Antibiotic selection

The initial treatment of chorioamnionitis specifically targets the 2 major organisms that cause neonatal pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis: GBS and E coli. For many years, the drugs of choice have been intravenous ampicillin (2 g every 6 hours) plus intravenous gentamicin (5 mg/kg of IBW every 24 hours). Gentamicin also can be administered intravenously at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg every 8 hours. I prefer the once-daily dosing for 3 reasons:

- Gentamicin works by a concentration-dependent mechanism; the higher the initial serum concentration, the better the killing effect.

- Once-daily dosing preserves long periods with low trough levels, an effect that minimizes ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity.

- Once-daily dosing is more convenient.

In a patient who has a contraindication to use of an aminoglycoside, aztreonam (2 g intravenously every 8 hours) may be combined with ampicillin.2

If the patient delivers vaginally, 1 dose of each drug should be administered postpartum, and then the antibiotics should be discontinued. If the patient delivers by cesarean, a single dose of a medication with strong anaerobic coverage should be administered immediately after the infant’s umbilical cord is clamped. Options include clindamycin (900 mg intravenously) or metronidazole (500 mg intravenously).11

There are 2 key exceptions to the single postpartum dose rule, however. If the patient is obese (body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) or if the membranes have been ruptured for more than 24 hours, antibiotics should be continued until she has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 hours.12

Two single agents are excellent alternatives to the combination ampicillin-gentamicin regimen. One is ampicillin-sulbactam, 3 g intravenously every 6 hours. The other is piperacillin-tazobactam, 3.375 g intravenously every 6 hours. These extended-spectrum penicillins provide exceptionally good coverage against the major pathogens that cause chorioamnionitis. Although more expensive than the combination regimen, they avoid the potential ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity associated with gentamicin.2

6. Endometritis

Puerperal endometritis is significantly more common after CD than after vaginal delivery. The infection is polymicrobial, and the principal pathogens are anaerobic gram-positive cocci, anaerobic gram-negative bacilli, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and aerobic gram-positive cocci. The diagnosis usually is made almost exclusively based on clinical findings: fever within 24 to 36 hours of delivery, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, and lower abdominal/pelvic pain and tenderness in the absence of any other localizing sign of infection.13

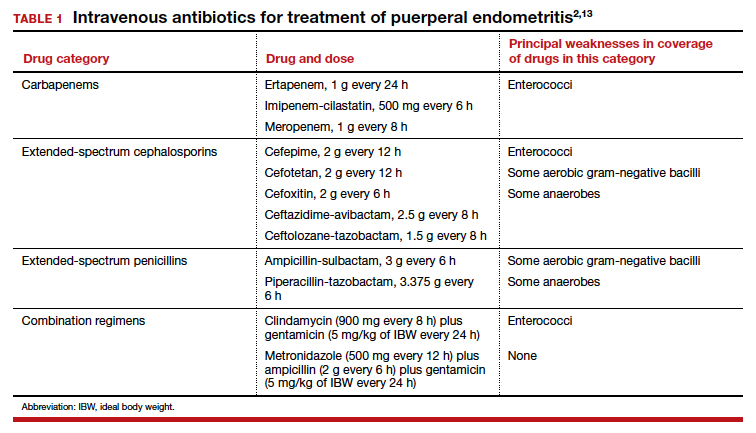

Antibiotic selection

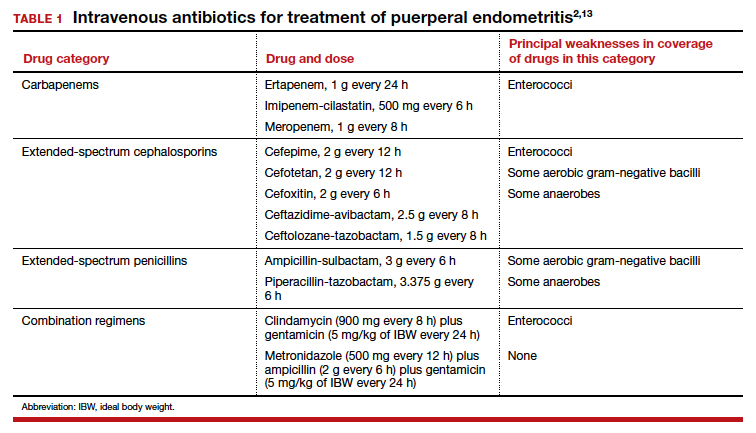

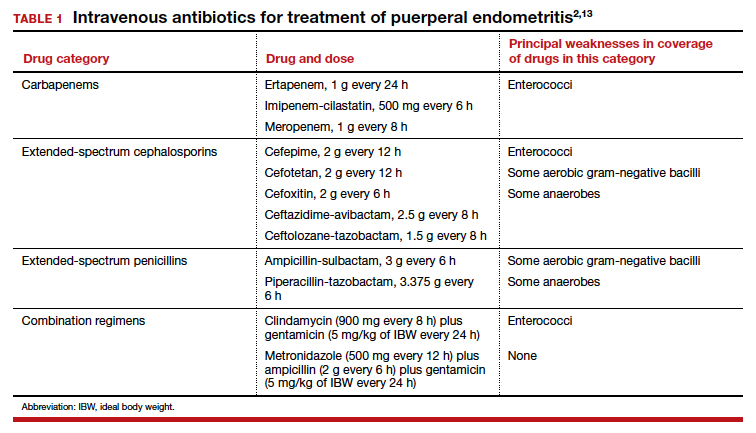

Effective treatment of endometritis requires administration of antibiotics that provide coverage against the broad range of pelvic pathogens. For many years, the gold standard of treatment has been the combination regimens of clindamycin plus gentamicin or metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin. These drugs are available in generic form and are relatively inexpensive. However, several broad-spectrum single agents are now available for treatment of endometritis. Although they are moderately more expensive than the generic combination regimens, they usually are very well tolerated, and they avoid the potential nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity associated with gentamicin. TABLE 1 summarizes the dosing regimens of these various agents and their potential weaknesses in coverage.2,13

7. Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is caused by the gram-negative diplococcus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The organism has a propensity to infect columnar epithelium and uroepithelium, and, typically, it causes a localized infection of the urethra, endocervix, and rectum. The organism also can cause an oropharyngeal infection, a disseminated infection (most commonly manifested by dermatitis and arthritis), and perihepatitis.

The diagnosis is best confirmed by a NAAT that can simultaneously test for gonorrhea and chlamydia in urine or in secretions obtained from the urethra, endocervix, and rectum.2,10

Antibiotic selection

The drugs of choice for treating uncomplicated gonococcal infection in pregnancy are a single dose of ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly, or cefixime 800 mg orally. If the patient is allergic to β-lactam antibiotics, the recommended treatment is gentamicin 240 mg intramuscularly in a single dose, combined with azithromycin 2,000 mg orally.14

8. Group B streptococci prophylaxis

The first-line agents for GBS prophylaxis are penicillin and ampicillin. Resistance of GBS to either of these antibiotics is extremely rare. The appropriate penicillin dose is 3 million U intravenously every 4 hours; the intravenous dose of ampicillin is 2 g initially, then 1 g every 4 hours. I prefer penicillin for prophylaxis because it has a narrower spectrum of activity and is less likely to cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea. The antibiotic should be continued until delivery of the neonate.2,15,16

If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, the drug of choice is cefazolin 2 g intravenously initially, then 1 g every 8 hours. If the patient’s allergy to β-lactam antibiotics is severe, the alternative agents are vancomycin (20 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours infused over 1–2 hours; maximum single dose of 2 g) and clindamycin (900 mg intravenously every 8 hours). The latter drug should be used only if sensitivity testing has confirmed that the GBS strain is sensitive to clindamycin. Resistance to clindamycin usually ranges from 10% to 15%.2,15,16

9. Puerperal mastitis

The principal microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis are the aerobic streptococci and staphylococci that form part of the normal skin flora. The diagnosis usually is made based on the characteristic clinical findings: erythema, tenderness, and warmth in an area of the breast accompanied by a purulent nipple discharge and fever and chills. The vast majority of cases can be treated with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis. The key indications for hospitalization are severe illness, particularly in an immunocompromised patient, and suspicion of a breast abscess.2

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

The initial drug of choice for treatment of mastitis is dicloxacillin sodium 500 mg every 6 hours for 7 to 10 days. If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, the appropriate alternative is cephalexin 500 mg every 8 hours for 7 to 10 days. If the patient’s allergy to penicillin is severe, 2 alternatives are possible. One is clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days; the other is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg), twice daily for 7 to 10 days. The latter 2 drugs are also of great value if the patient fails to respond to initial therapy and/or infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected.2 I prefer the latter agent because it is less expensive than clindamycin and is less likely to cause antibiotic-induced diarrhea.

If hospitalization is required, the drug of choice is intravenous vancomycin. The appropriate dosage is 20 mg/kg every 8 to 12 hours (maximum single dose of 2 g).2

10. Syphilis

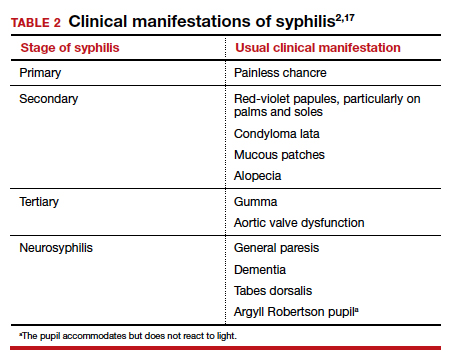

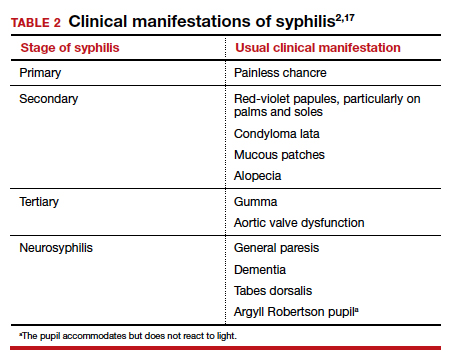

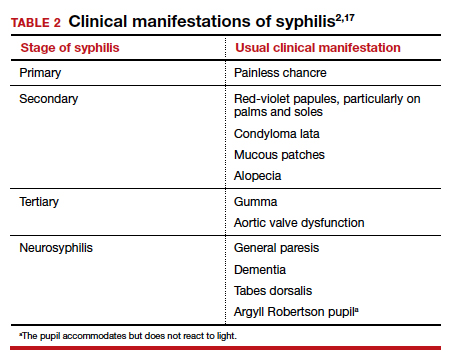

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete bacterium, Treponema pallidum. The diagnosis can be made by clinical examination if the characteristic findings listed in TABLE 2 are present.2,17 However, most patients in our practice will have latent syphilis, and the diagnosis must be established based on serologic screening.17

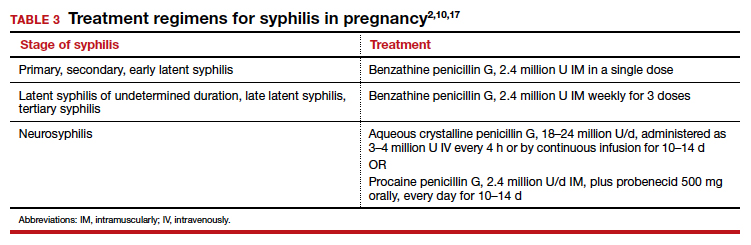

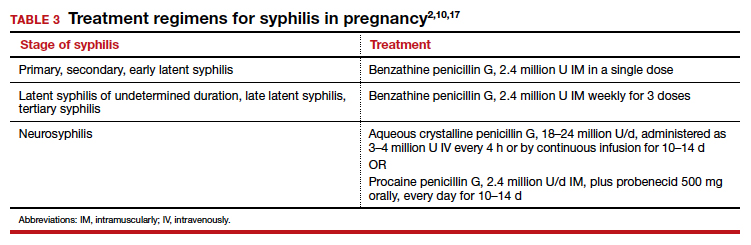

Antibiotic selection

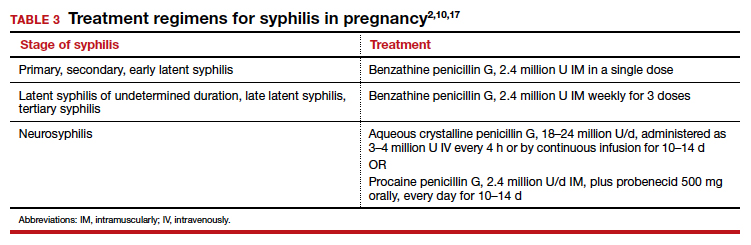

In pregnancy, the treatment of choice for syphilis is penicillin (TABLE 3).2,10,17 Only penicillin has been proven effective in treating both maternal and fetal infection. If the patient has a history of allergy to penicillin, she should undergo skin testing to determine if she is truly allergic. If hypersensitivity is confirmed, the patient should be desensitized and then treated with the appropriate regimen outlined in TABLE 3. Of interest, within a short period of time after treatment, the patient’s sensitivity to penicillin will be reestablished, and she should not be treated again with penicillin unless she undergoes another desensitization process.2,17

11. Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis is caused by the flagellated protozoan, Trichomonas vaginalis. The condition is characterized by a distinct yellowish-green vaginal discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5, and motile flagellated organisms are easily visualized on saline microscopy. The vaginal panel assay also is a valuable diagnostic test.3

Antibiotic selection

The drug of choice for trichomoniasis is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. The patient’s sexual partner(s) should be treated concurrently to prevent reinfection. Most treatment failures are due to poor compliance with therapy on the part of either the patient or her partner(s); true drug resistance is uncommon. When antibiotic resistance is strongly suspected, the patient may be treated with a single 2-g oral dose of tinidazole.2

12. Urinary tract infections

Urethritis

Acute urethritis usually is caused by C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae. The treatment of infections with these 2 organisms is discussed above.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis

Bladder infections are caused primarily by E coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus species. Gram-positive cocci such as enterococci, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and GBS are less common pathogens.18

The key diagnostic criterion for asymptomatic bacteriuria is a colony count greater than 100,000 organisms/mL of a single uropathogen on a clean-catch midstream urine specimen.18

The usual clinical manifestations of acute cystitis include frequency, urgency, hesitancy, suprapubic discomfort, and a low-grade fever. The diagnosis is most effectively confirmed by obtaining urine by catheterization and demonstrating a positive nitrite and positive leukocyte esterase reaction on dipstick examination. The finding of a urine pH of 8 or greater usually indicates an infection caused by Proteus species. When urine is obtained by catheterization, the criterion for defining a positive culture is greater than 100 colonies/mL.18

Antibiotic selection. In the first trimester, the preferred agents for treatment of a lower urinary tract infection are oral amoxicillin (875 mg twice daily) or cephalexin (500 mg every 8 hours). For an initial infection, a 3-day course of therapy usually is adequate. For a recurrent infection, a 7- to 10-day course is indicated.

Beyond the first trimester, nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals (100 mg orally twice daily) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg twice daily) are the preferred agents. Unless no other oral drug is likely to be effective, these 2 drugs should be avoided in the first trimester. The former has been associated with eye, heart, and cleft defects. The latter has been associated with neural tube defects, cardiac anomalies, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia.18

Acute pyelonephritis

Acute infections of the kidney usually are caused by the aerobic gram-negative bacilli: E coli, K pneumoniae, and Proteus species. Enterococci, S saprophyticus, and GBS are less likely to cause upper tract infection as opposed to bladder infection.

The typical clinical manifestations of acute pyelonephritis include high fever and chills in association with flank pain and tenderness. The diagnosis is best confirmed by obtaining urine by catheterization and documenting the presence of a positive nitrite and leukocyte esterase reaction. Again, an elevated urine pH is indicative of an infection secondary to Proteus species. The criterion for defining a positive culture from catheterized urine is greater than 100 colonies/mL.2,18

Antibiotic selection. Patients in the first half of pregnancy who are hemodynamically stable and who show no signs of preterm labor may be treated with oral antibiotics as outpatients. The 2 drugs of choice are amoxicillin-clavulanate (875 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days).

For unstable patients in the first half of pregnancy and for essentially all patients in the second half of pregnancy, parenteral treatment should be administered on an inpatient basis. My preference for treatment is ceftriaxone, 2 g intravenously every 24 hours. The drug provides excellent coverage against almost all the uropathogens. It has a convenient dosing schedule, and it usually is very well tolerated. Parenteral therapy should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 to 48 hours. At this point, the patient can be transitioned to one of the oral regimens listed above and managed as an outpatient. If the patient is allergic to β-lactam antibiotics, an excellent alternative is aztreonam, 2 g intravenously every 8 hours.2,18 ●

- Reeder CF, Duff P. A case of BV during pregnancy: best management approach. OBG Manag. 2021;33(2):38-42.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1145.

- Broache M, Cammarata CL, Stonebraker E, et al. Performance of a vaginal panel assay compared with the clinical diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:853-859.

- Hiller SL, Nyirjesy P, Waldbaum AS, et al. Secnidazole treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:379-386.

- Kirkpatrick K, Duff P. Candidiasis: the essentials of diagnosis and treatment. OBG Manag. 2020;32(8):27-29, 34.

- Ibrexafungerp (Brexafemme) for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021;63:141-143.

- Duff P. Prevention of infection after cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:758-770.

- Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, et al; for the C/SOAP Trial Consortium. Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1231-1241.

- Harper LM, Kilgore M, Szychowski JM, et al. Economic evaluation of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:328-334.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(RR3):1-137.

- Edwards RK, Duff P. Single additional dose postpartum therapy for women with chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):957-961.

- Black LP, Hinson L, Duff P. Limited course of antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1102-1105.

- Duff P. Fever following cesarean delivery: what are your steps for management? OBG Manag. 2021;33(12):26-30, 35.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Warkowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Prevention of group B streptococcal early-onset disease in newborns: ACOG committee opinion summary, number 782. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:1.

- Duff P. Preventing early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. OBG Manag. 2019;31(12):26, 28-31.

- Finley TA, Duff P. Syphilis: cutting risk through primary prevention and prenatal screening. OBG Manag. 2020;32(11):20, 22-27.

- Duff P. UTIs in pregnancy: managing urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, and pyelonephritis. OBG Manag. 2022;34(1):42-46.

For the infections we most commonly encounter in obstetric practice, I review in this article the selection of specific antibiotics. I focus on the key pathogens that cause these infections, the most useful diagnostic tests, and the most cost-effective antibiotic therapy. Relative cost estimates (high vs low) for drugs are based on information published on the GoodRx website (https://www.goodrx.com/). Actual charges to patients, of course, may vary widely depending on contractual relationships between hospitals, insurance companies, and wholesale vendors. The infections are listed in alphabetical order, not in order of frequency or severity.

1. Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a polymicrobial infection that results from perturbation of the normal vaginal flora due to conditions such as pregnancy, hormonal therapy, and changes in the menstrual cycle. It is characterized by a decrease in the vaginal concentration of Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by an increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus species, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.1,2

BV is characterized by a thin, white-gray malodorous (fishlike smell) discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5. Clue cells are apparent on saline microscopy, and the whiff (amine) test is positive when potassium hydroxide is added to a drop of vaginal secretions. Diagnostic accuracy can be improved using one of the new vaginal panel assays such as BD MAX Vaginal Panel (Becton, Dickinson and Company).3

Antibiotic selection

Antibiotic treatment of BV is directed primarily at the anaerobic component of the infection. The preferred treatment is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. If the patient cannot tolerate metronidazole, oral clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 days, can be used, although it is more expensive than metronidazole. Topical metronidazole vaginal gel (0.75%), 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is effective in treating the local vaginal infection, but it is not effective in preventing systemic complications such as preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, and puerperal endometritis.2 It also is significantly more expensive than the oral formulation of metronidazole. Topical clindamycin cream, 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is even more expensive.

Tinidazole 2 g orally daily for 2 days is an effective alternative to oral metronidazole. Single-dose therapy with oral secnidazole (2 g), a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, has been effective in small studies, but experience with this drug in the United States is limited. Secnidazole is also very expensive.4

2. Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis usually is caused by Candida albicans. Other less common species include C tropicalis, C glabrata, C auris, C lusitaniae, and C krusei. The most common clinical findings are vulvovaginal pruritus in association with a curdlike white vaginal discharge. The diagnosis can be established by confirmation of a normal vaginal pH and identification of budding yeast and hyphae on a potassium hydroxide preparation. As noted above for BV, the vaginal panel assay improves the accuracy of clinical diagnosis.3 Culture usually is indicated only in patients with infections that are refractory to therapy.

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

In the first trimester of pregnancy, vulvovaginal candidiasis should be treated with a topical medication such as clotrimazole cream 1% (50 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), miconazole cream 2% (100 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), or terconazole cream 0.4% (50 g intravaginally daily for 7 days). Single-dose formulations or 3-day courses of treatment may not be quite as effective in pregnant patients, but they do offer a more convenient dosing schedule.2,5

Oral fluconazole should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion and with fetal cardiac septal defects. Beyond the first trimester, oral fluconazole offers an attractive option for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The appropriate dose is 150 mg initially, with a repeat dose in 3 days if symptoms persist.2,5

Ibrexafungerp (300 mg twice daily for 1 day) was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for oral treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. However, this drug is teratogenic and is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation. It also is significantly more expensive than fluconazole.6

3. Cesarean delivery prophylaxis

All women having a cesarean delivery (CD) should receive antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce the risk of endometritis and wound infection.

Antibiotic selection

In my opinion, the preferred regimen is intravenous cefazolin 2 g plus azithromycin 500 mg administered preoperatively.7 Cefazolin can be administered in a rapid bolus; azithromycin should be administered over 1 hour.

In an exceptionally rigorous investigation called the C/SOAP trial (Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis trial), Tita and colleagues showed that the combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin was superior to single-agent prophylaxis (usually with cefazolin) in preventing the composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection occurring within 6 weeks of surgery.8 The additive effect of azithromycin was particularly pronounced in patients having CD after labor and rupture of membranes. Harper and associates subsequently validated the cost-effectiveness of this combination regimen using a decision analytic model.9

If the patient has a serious allergy to β-lactam antibiotics, the best alternative regimen for prophylaxis is clindamycin plus gentamicin. The appropriate single intravenous dose of clindamycin is 900 mg; the single dose of gentamicin should be 5 mg/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).7

4. Chlamydia