User login

Childhood type 1 diabetes tests suggested at ages 2 and 6

, new data suggest.

Both genetic screening and islet-cell autoantibody screening for type 1 diabetes risk have become less expensive in recent years. Nonetheless, as of now, most children who receive such screening do so through programs that screen relatives of people who already have the condition, such as the global TrialNet program.

Some in the type 1 diabetes field have urged wider screening, with the rationale that knowledge of increased risk can prepare families to recognize the early signs of hyperglycemia and seek medical help to prevent the onset of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Moreover, potential therapies to prevent or delay type 1 diabetes are currently in development, including the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody teplizumab (Tzield, Provention Bio).

However, given that the incidence of type 1 diabetes is about 1 in 300 children, any population-wide screening program would need to be implemented in the most efficient and cost-effective way possible with limited numbers of tests, say Mohamed Ghalwash, PhD, of the Center for Computational Health, IBM Research, Yorktown Heights, N.Y., and colleagues.

Results from their analysis of nearly 25,000 children from five prospective cohorts in Europe and the United States were published online in Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Screening in kids feasible, but may need geographic tweaking

“Our results show that initial screening for islet autoantibodies at two ages (2 years and 6 years) is sensitive and efficient for public health translation but might require adjustment by country on the basis of population-specific disease characteristics,” Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues write.

In an accompanying editorial, pediatric endocrinologist Maria J. Redondo, MD, PhD, writes: “This study is timely because recent successes in preventing type 1 diabetes highlight the need to identify the best candidates for intervention ... This paper constitutes an important contribution to the literature.”

However, Dr. Redondo, of Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, also cautioned: “It remains to be seen whether Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues’ strategy could work in the general population, because all the participants in the combined dataset had genetic risk factors for the disease or a relative with type 1 diabetes, in whom performance is expected to be higher.”

She also noted that most participants were of northern European ancestry and that it is unknown whether the same or a similar screening strategy could be applied to individuals older than 15 years, in whom preclinical type 1 diabetes progresses more slowly.

Two-time childhood screening yielded high sensitivity, specificity

The data from a total of 24,662 participants were pooled from five prospective cohorts from Finland (DIPP), Germany (BABYDIAB), Sweden (DiPiS), and the United States (DAISY and DEW-IT).

All were at elevated risk for type 1 diabetes based on human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotyping, and some had first-degree relatives with the condition. Participants were screened annually for three type 1 diabetes–associated autoantibodies up to age 15 years or the onset of type 1 diabetes.

During follow-up, 672 children developed type 1 diabetes by age 15 years and 6,050 did not. (The rest hadn’t yet reached age 15 years or type 1 diabetes onset.) The median age at first appearance of islet autoantibodies was 4.5 years.

A two-age screening strategy at 2 years and 6 years was more sensitive than screening at just one age, with a sensitivity of 82% and a positive predictive value of 79% for the development of type 1 diabetes by age 15 years.

The predictive value increased with the number of autoantibodies tested. For example, a single islet autoantibody at age 2 years indicated a 4-year risk of developing type 1 diabetes by age 5.99 years of 31%, while multiple antibody positivity at age 2 years carried a 4-year risk of 55%.

By age 6 years, the risk over the next 9 years was 39% if the test had been negative at age 2 years and 70% if the test had been positive at 2 years. But overall, a 6-year-old with multiple autoantibodies had an overall 83% risk of type 1 diabetes regardless of the test result at 2 years.

The predictive performance of sensitivity by age differed by country, suggesting that the optimal ages for autoantibody testing might differ by geographic region, Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues say.

Dr. Redondo commented, “The model might require adaptation to local factors that affect the progression and prevalence of type 1 diabetes.” And, she added, “important aspects, such as screening cost, global access, acceptability, and follow-up support will need to be addressed for this strategy to be a viable public health option.”

The study was funded by JDRF. Dr. Ghalwash and another author are employees of IBM. A third author was a JDRF employee when the research was done and is now an employee of Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Redondo has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new data suggest.

Both genetic screening and islet-cell autoantibody screening for type 1 diabetes risk have become less expensive in recent years. Nonetheless, as of now, most children who receive such screening do so through programs that screen relatives of people who already have the condition, such as the global TrialNet program.

Some in the type 1 diabetes field have urged wider screening, with the rationale that knowledge of increased risk can prepare families to recognize the early signs of hyperglycemia and seek medical help to prevent the onset of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Moreover, potential therapies to prevent or delay type 1 diabetes are currently in development, including the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody teplizumab (Tzield, Provention Bio).

However, given that the incidence of type 1 diabetes is about 1 in 300 children, any population-wide screening program would need to be implemented in the most efficient and cost-effective way possible with limited numbers of tests, say Mohamed Ghalwash, PhD, of the Center for Computational Health, IBM Research, Yorktown Heights, N.Y., and colleagues.

Results from their analysis of nearly 25,000 children from five prospective cohorts in Europe and the United States were published online in Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Screening in kids feasible, but may need geographic tweaking

“Our results show that initial screening for islet autoantibodies at two ages (2 years and 6 years) is sensitive and efficient for public health translation but might require adjustment by country on the basis of population-specific disease characteristics,” Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues write.

In an accompanying editorial, pediatric endocrinologist Maria J. Redondo, MD, PhD, writes: “This study is timely because recent successes in preventing type 1 diabetes highlight the need to identify the best candidates for intervention ... This paper constitutes an important contribution to the literature.”

However, Dr. Redondo, of Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, also cautioned: “It remains to be seen whether Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues’ strategy could work in the general population, because all the participants in the combined dataset had genetic risk factors for the disease or a relative with type 1 diabetes, in whom performance is expected to be higher.”

She also noted that most participants were of northern European ancestry and that it is unknown whether the same or a similar screening strategy could be applied to individuals older than 15 years, in whom preclinical type 1 diabetes progresses more slowly.

Two-time childhood screening yielded high sensitivity, specificity

The data from a total of 24,662 participants were pooled from five prospective cohorts from Finland (DIPP), Germany (BABYDIAB), Sweden (DiPiS), and the United States (DAISY and DEW-IT).

All were at elevated risk for type 1 diabetes based on human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotyping, and some had first-degree relatives with the condition. Participants were screened annually for three type 1 diabetes–associated autoantibodies up to age 15 years or the onset of type 1 diabetes.

During follow-up, 672 children developed type 1 diabetes by age 15 years and 6,050 did not. (The rest hadn’t yet reached age 15 years or type 1 diabetes onset.) The median age at first appearance of islet autoantibodies was 4.5 years.

A two-age screening strategy at 2 years and 6 years was more sensitive than screening at just one age, with a sensitivity of 82% and a positive predictive value of 79% for the development of type 1 diabetes by age 15 years.

The predictive value increased with the number of autoantibodies tested. For example, a single islet autoantibody at age 2 years indicated a 4-year risk of developing type 1 diabetes by age 5.99 years of 31%, while multiple antibody positivity at age 2 years carried a 4-year risk of 55%.

By age 6 years, the risk over the next 9 years was 39% if the test had been negative at age 2 years and 70% if the test had been positive at 2 years. But overall, a 6-year-old with multiple autoantibodies had an overall 83% risk of type 1 diabetes regardless of the test result at 2 years.

The predictive performance of sensitivity by age differed by country, suggesting that the optimal ages for autoantibody testing might differ by geographic region, Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues say.

Dr. Redondo commented, “The model might require adaptation to local factors that affect the progression and prevalence of type 1 diabetes.” And, she added, “important aspects, such as screening cost, global access, acceptability, and follow-up support will need to be addressed for this strategy to be a viable public health option.”

The study was funded by JDRF. Dr. Ghalwash and another author are employees of IBM. A third author was a JDRF employee when the research was done and is now an employee of Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Redondo has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new data suggest.

Both genetic screening and islet-cell autoantibody screening for type 1 diabetes risk have become less expensive in recent years. Nonetheless, as of now, most children who receive such screening do so through programs that screen relatives of people who already have the condition, such as the global TrialNet program.

Some in the type 1 diabetes field have urged wider screening, with the rationale that knowledge of increased risk can prepare families to recognize the early signs of hyperglycemia and seek medical help to prevent the onset of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Moreover, potential therapies to prevent or delay type 1 diabetes are currently in development, including the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody teplizumab (Tzield, Provention Bio).

However, given that the incidence of type 1 diabetes is about 1 in 300 children, any population-wide screening program would need to be implemented in the most efficient and cost-effective way possible with limited numbers of tests, say Mohamed Ghalwash, PhD, of the Center for Computational Health, IBM Research, Yorktown Heights, N.Y., and colleagues.

Results from their analysis of nearly 25,000 children from five prospective cohorts in Europe and the United States were published online in Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Screening in kids feasible, but may need geographic tweaking

“Our results show that initial screening for islet autoantibodies at two ages (2 years and 6 years) is sensitive and efficient for public health translation but might require adjustment by country on the basis of population-specific disease characteristics,” Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues write.

In an accompanying editorial, pediatric endocrinologist Maria J. Redondo, MD, PhD, writes: “This study is timely because recent successes in preventing type 1 diabetes highlight the need to identify the best candidates for intervention ... This paper constitutes an important contribution to the literature.”

However, Dr. Redondo, of Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, also cautioned: “It remains to be seen whether Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues’ strategy could work in the general population, because all the participants in the combined dataset had genetic risk factors for the disease or a relative with type 1 diabetes, in whom performance is expected to be higher.”

She also noted that most participants were of northern European ancestry and that it is unknown whether the same or a similar screening strategy could be applied to individuals older than 15 years, in whom preclinical type 1 diabetes progresses more slowly.

Two-time childhood screening yielded high sensitivity, specificity

The data from a total of 24,662 participants were pooled from five prospective cohorts from Finland (DIPP), Germany (BABYDIAB), Sweden (DiPiS), and the United States (DAISY and DEW-IT).

All were at elevated risk for type 1 diabetes based on human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotyping, and some had first-degree relatives with the condition. Participants were screened annually for three type 1 diabetes–associated autoantibodies up to age 15 years or the onset of type 1 diabetes.

During follow-up, 672 children developed type 1 diabetes by age 15 years and 6,050 did not. (The rest hadn’t yet reached age 15 years or type 1 diabetes onset.) The median age at first appearance of islet autoantibodies was 4.5 years.

A two-age screening strategy at 2 years and 6 years was more sensitive than screening at just one age, with a sensitivity of 82% and a positive predictive value of 79% for the development of type 1 diabetes by age 15 years.

The predictive value increased with the number of autoantibodies tested. For example, a single islet autoantibody at age 2 years indicated a 4-year risk of developing type 1 diabetes by age 5.99 years of 31%, while multiple antibody positivity at age 2 years carried a 4-year risk of 55%.

By age 6 years, the risk over the next 9 years was 39% if the test had been negative at age 2 years and 70% if the test had been positive at 2 years. But overall, a 6-year-old with multiple autoantibodies had an overall 83% risk of type 1 diabetes regardless of the test result at 2 years.

The predictive performance of sensitivity by age differed by country, suggesting that the optimal ages for autoantibody testing might differ by geographic region, Dr. Ghalwash and colleagues say.

Dr. Redondo commented, “The model might require adaptation to local factors that affect the progression and prevalence of type 1 diabetes.” And, she added, “important aspects, such as screening cost, global access, acceptability, and follow-up support will need to be addressed for this strategy to be a viable public health option.”

The study was funded by JDRF. Dr. Ghalwash and another author are employees of IBM. A third author was a JDRF employee when the research was done and is now an employee of Janssen Research and Development. Dr. Redondo has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM LANCET DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY

Social media in the lives of adolescents

Adolescence is a time of growing autonomy fueled by puberty, intellectual development, and identity formation. Social media engages adolescents by giving them easy access to (semi) private communication with peers, the ability to safely explore their sexuality, and easily investigate issues of intellectual curiosity, as they move from childhood to older adolescence. Social media facilitates the creation of a teenager’s own world, separate and distinct from adult concern or scrutiny. It is clearly compelling for adolescents, but we are in the early days of understanding the effect of various types of digital activities on the health and well-being of youth. There is evidence that for some, the addictive potential of these applications is potent, exacerbating or triggering mood, anxiety, and eating disorder symptoms. Their drive to explore their identity and relationships and their immature capacity to regulate emotions and behaviors make the risks of overuse substantial. But it would be impossible (and probably socially very costly) to simply avoid social media. So how to discuss its healthy use with your patients and their parents?

The data

Social media are digital communication platforms that allow users to build a public profile and then accumulate a network of followers, and follow other users, based on shared interests. They include FaceBook, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, and Twitter. Surveys demonstrated that 90% of U.S. adolescents use social media, with 75% having at least one social media profile and over half visiting social media sites at least once daily. Adolescents spend over 7 hours daily on their phones, not including time devoted to online schoolwork, and 8- to 12-year-olds are not far behind at almost 5 hours of daily phone use. On average, 39% of adolescent screen time is spent on passive consumption, 26% on social media, 25% on interactive activities (browsing the web, interactive video gaming) and 3% on content creation (coding, etc). There was considerable variability in survey results, and differences between genders, with boys engaged in video games almost eight times as often as girls, and girls in social media nearly twice as often as boys.1

The research

There is a growing body of research devoted to understanding the effects of all of this digital activity on youth health and well-being.

A large, longitudinal study of Canadian 13- to 17-year-olds found that time spent on social media or watching television was strongly associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms, with a robust dose-response relationship.2 However, causality is not clear, as anxious, shy, and depressed adolescents may use more social media as a consequence of their mood. Interestingly, there was no such relationship with mood and anxiety symptoms and time spent on video games.3 For youth with depression and anxiety, time spent on social media has been strongly associated with increased levels of self-reported distress, self-injury and suicidality, but again, causality is hard to prove.

One very large study from the United Kingdom (including more than 10,000 participants), demonstrated a strong relationship between time spent on social media and severity of depressive symptoms, with a more pronounced effect in girls than in boys.4 Many more nuanced studies have demonstrated that excessive time spent on social media, the presence of an addictive pattern of use, and the degree to which an adolescent’s sense of well-being is connected to social media are the variables that strongly predict an association with worsening depressive or anxiety symptoms.5

Several studies have demonstrated that low to moderate use of social media, and use to gather information and make plans were associated with better scores of emotional self-regulation and lower rates of depressive symptoms in teens.6 It seems safe to say that social media can be useful and fun, but that too much can be bad for you. So help your adolescent patients to expand their perspective on its use by discussing it with them.

Make them curious about quantity

Most teens feel they do not have enough time for all of the things they need to do, so invite them to play detective by using their phone’s applications that can track their time spent online and in different apps.

Remind them that these apps were designed to be so engaging that for some addiction is a real problem. As with tobacco, addiction is the business model by which these companies earn advertising dollars. Indeed, adolescents are the target demographic, as they are most sensitive to social rewards and are the most valuable audience for advertisers. Engage their natural suspicion of authority by pointing out that with every hour on Insta, someone else is making a lot of money. They get to choose how they want to relax, connect with friends, and explore the world, so help them to be aware of how these apps are designed to keep them from choosing.

Raise awareness of vulnerability

Adolescents who have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder already have difficulty with impulse control and with shifting their attention to less engaging activities. Adolescents with anxiety are prone to avoid stressful situations, but still hunger for knowledge and connections. Adolescents with depression are managing low motivation and self-esteem, and the rewards of social media may keep them from exercise and actual social engagement that are critical to their treatment. Youth with eating disorders are especially prone to critical comparison of themselves to others, feeding their distorted body images. Help your patients with these common illnesses to be aware of how social media may make their treatment harder, rather than being the source of relief it may feel like.

Protect their health

For all young people, too much time spent in virtual activities and passive media consumption may not leave enough time to explore potential interests, talents, or relationships. These are important activities throughout life, but they are the central developmental tasks of adolescence. They also need 8-10 hours of sleep nightly and regular exercise. And of course, they have homework! Help them to think about how to use their time wisely to support satisfying relationships and activities, with time for relaxation and good health.

Keep parents in the room for these discussions

State that most of us have difficulty putting down our phones. Children and teens need adults who model striving for balance in all areas of choice. Just as we try to teach them to make good choices about food, getting excellent nutrition while still valuing taste and pleasure, we can talk about how to balance virtual activities with actual activities, work with play, and effort with relaxation. You can help expand your young patients’ self-awareness, acknowledge the fun and utility of their digital time, and enhance their sense of how we must all learn how to put screens down sometimes. In so doing, you can help families to ensure that they are engaging with the digital tools and toys available to all of us in ways that can support their health and well-being.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Teens and Tweens, 2015.

2. Abi-Jaoude E et al. CMAJ 2020;192(6):E136-41.

3. Boers E et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;65(3):206-8.

4. Kelly Y et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jan 4;6:59-68.

5. Vidal C et al. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2020 May;32(3):235-53.

6. Coyne SM et al. J Res Adolescence. 2019;29(4):897-907.

Adolescence is a time of growing autonomy fueled by puberty, intellectual development, and identity formation. Social media engages adolescents by giving them easy access to (semi) private communication with peers, the ability to safely explore their sexuality, and easily investigate issues of intellectual curiosity, as they move from childhood to older adolescence. Social media facilitates the creation of a teenager’s own world, separate and distinct from adult concern or scrutiny. It is clearly compelling for adolescents, but we are in the early days of understanding the effect of various types of digital activities on the health and well-being of youth. There is evidence that for some, the addictive potential of these applications is potent, exacerbating or triggering mood, anxiety, and eating disorder symptoms. Their drive to explore their identity and relationships and their immature capacity to regulate emotions and behaviors make the risks of overuse substantial. But it would be impossible (and probably socially very costly) to simply avoid social media. So how to discuss its healthy use with your patients and their parents?

The data

Social media are digital communication platforms that allow users to build a public profile and then accumulate a network of followers, and follow other users, based on shared interests. They include FaceBook, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, and Twitter. Surveys demonstrated that 90% of U.S. adolescents use social media, with 75% having at least one social media profile and over half visiting social media sites at least once daily. Adolescents spend over 7 hours daily on their phones, not including time devoted to online schoolwork, and 8- to 12-year-olds are not far behind at almost 5 hours of daily phone use. On average, 39% of adolescent screen time is spent on passive consumption, 26% on social media, 25% on interactive activities (browsing the web, interactive video gaming) and 3% on content creation (coding, etc). There was considerable variability in survey results, and differences between genders, with boys engaged in video games almost eight times as often as girls, and girls in social media nearly twice as often as boys.1

The research

There is a growing body of research devoted to understanding the effects of all of this digital activity on youth health and well-being.

A large, longitudinal study of Canadian 13- to 17-year-olds found that time spent on social media or watching television was strongly associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms, with a robust dose-response relationship.2 However, causality is not clear, as anxious, shy, and depressed adolescents may use more social media as a consequence of their mood. Interestingly, there was no such relationship with mood and anxiety symptoms and time spent on video games.3 For youth with depression and anxiety, time spent on social media has been strongly associated with increased levels of self-reported distress, self-injury and suicidality, but again, causality is hard to prove.

One very large study from the United Kingdom (including more than 10,000 participants), demonstrated a strong relationship between time spent on social media and severity of depressive symptoms, with a more pronounced effect in girls than in boys.4 Many more nuanced studies have demonstrated that excessive time spent on social media, the presence of an addictive pattern of use, and the degree to which an adolescent’s sense of well-being is connected to social media are the variables that strongly predict an association with worsening depressive or anxiety symptoms.5

Several studies have demonstrated that low to moderate use of social media, and use to gather information and make plans were associated with better scores of emotional self-regulation and lower rates of depressive symptoms in teens.6 It seems safe to say that social media can be useful and fun, but that too much can be bad for you. So help your adolescent patients to expand their perspective on its use by discussing it with them.

Make them curious about quantity

Most teens feel they do not have enough time for all of the things they need to do, so invite them to play detective by using their phone’s applications that can track their time spent online and in different apps.

Remind them that these apps were designed to be so engaging that for some addiction is a real problem. As with tobacco, addiction is the business model by which these companies earn advertising dollars. Indeed, adolescents are the target demographic, as they are most sensitive to social rewards and are the most valuable audience for advertisers. Engage their natural suspicion of authority by pointing out that with every hour on Insta, someone else is making a lot of money. They get to choose how they want to relax, connect with friends, and explore the world, so help them to be aware of how these apps are designed to keep them from choosing.

Raise awareness of vulnerability

Adolescents who have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder already have difficulty with impulse control and with shifting their attention to less engaging activities. Adolescents with anxiety are prone to avoid stressful situations, but still hunger for knowledge and connections. Adolescents with depression are managing low motivation and self-esteem, and the rewards of social media may keep them from exercise and actual social engagement that are critical to their treatment. Youth with eating disorders are especially prone to critical comparison of themselves to others, feeding their distorted body images. Help your patients with these common illnesses to be aware of how social media may make their treatment harder, rather than being the source of relief it may feel like.

Protect their health

For all young people, too much time spent in virtual activities and passive media consumption may not leave enough time to explore potential interests, talents, or relationships. These are important activities throughout life, but they are the central developmental tasks of adolescence. They also need 8-10 hours of sleep nightly and regular exercise. And of course, they have homework! Help them to think about how to use their time wisely to support satisfying relationships and activities, with time for relaxation and good health.

Keep parents in the room for these discussions

State that most of us have difficulty putting down our phones. Children and teens need adults who model striving for balance in all areas of choice. Just as we try to teach them to make good choices about food, getting excellent nutrition while still valuing taste and pleasure, we can talk about how to balance virtual activities with actual activities, work with play, and effort with relaxation. You can help expand your young patients’ self-awareness, acknowledge the fun and utility of their digital time, and enhance their sense of how we must all learn how to put screens down sometimes. In so doing, you can help families to ensure that they are engaging with the digital tools and toys available to all of us in ways that can support their health and well-being.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Teens and Tweens, 2015.

2. Abi-Jaoude E et al. CMAJ 2020;192(6):E136-41.

3. Boers E et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;65(3):206-8.

4. Kelly Y et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jan 4;6:59-68.

5. Vidal C et al. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2020 May;32(3):235-53.

6. Coyne SM et al. J Res Adolescence. 2019;29(4):897-907.

Adolescence is a time of growing autonomy fueled by puberty, intellectual development, and identity formation. Social media engages adolescents by giving them easy access to (semi) private communication with peers, the ability to safely explore their sexuality, and easily investigate issues of intellectual curiosity, as they move from childhood to older adolescence. Social media facilitates the creation of a teenager’s own world, separate and distinct from adult concern or scrutiny. It is clearly compelling for adolescents, but we are in the early days of understanding the effect of various types of digital activities on the health and well-being of youth. There is evidence that for some, the addictive potential of these applications is potent, exacerbating or triggering mood, anxiety, and eating disorder symptoms. Their drive to explore their identity and relationships and their immature capacity to regulate emotions and behaviors make the risks of overuse substantial. But it would be impossible (and probably socially very costly) to simply avoid social media. So how to discuss its healthy use with your patients and their parents?

The data

Social media are digital communication platforms that allow users to build a public profile and then accumulate a network of followers, and follow other users, based on shared interests. They include FaceBook, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, and Twitter. Surveys demonstrated that 90% of U.S. adolescents use social media, with 75% having at least one social media profile and over half visiting social media sites at least once daily. Adolescents spend over 7 hours daily on their phones, not including time devoted to online schoolwork, and 8- to 12-year-olds are not far behind at almost 5 hours of daily phone use. On average, 39% of adolescent screen time is spent on passive consumption, 26% on social media, 25% on interactive activities (browsing the web, interactive video gaming) and 3% on content creation (coding, etc). There was considerable variability in survey results, and differences between genders, with boys engaged in video games almost eight times as often as girls, and girls in social media nearly twice as often as boys.1

The research

There is a growing body of research devoted to understanding the effects of all of this digital activity on youth health and well-being.

A large, longitudinal study of Canadian 13- to 17-year-olds found that time spent on social media or watching television was strongly associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms, with a robust dose-response relationship.2 However, causality is not clear, as anxious, shy, and depressed adolescents may use more social media as a consequence of their mood. Interestingly, there was no such relationship with mood and anxiety symptoms and time spent on video games.3 For youth with depression and anxiety, time spent on social media has been strongly associated with increased levels of self-reported distress, self-injury and suicidality, but again, causality is hard to prove.

One very large study from the United Kingdom (including more than 10,000 participants), demonstrated a strong relationship between time spent on social media and severity of depressive symptoms, with a more pronounced effect in girls than in boys.4 Many more nuanced studies have demonstrated that excessive time spent on social media, the presence of an addictive pattern of use, and the degree to which an adolescent’s sense of well-being is connected to social media are the variables that strongly predict an association with worsening depressive or anxiety symptoms.5

Several studies have demonstrated that low to moderate use of social media, and use to gather information and make plans were associated with better scores of emotional self-regulation and lower rates of depressive symptoms in teens.6 It seems safe to say that social media can be useful and fun, but that too much can be bad for you. So help your adolescent patients to expand their perspective on its use by discussing it with them.

Make them curious about quantity

Most teens feel they do not have enough time for all of the things they need to do, so invite them to play detective by using their phone’s applications that can track their time spent online and in different apps.

Remind them that these apps were designed to be so engaging that for some addiction is a real problem. As with tobacco, addiction is the business model by which these companies earn advertising dollars. Indeed, adolescents are the target demographic, as they are most sensitive to social rewards and are the most valuable audience for advertisers. Engage their natural suspicion of authority by pointing out that with every hour on Insta, someone else is making a lot of money. They get to choose how they want to relax, connect with friends, and explore the world, so help them to be aware of how these apps are designed to keep them from choosing.

Raise awareness of vulnerability

Adolescents who have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder already have difficulty with impulse control and with shifting their attention to less engaging activities. Adolescents with anxiety are prone to avoid stressful situations, but still hunger for knowledge and connections. Adolescents with depression are managing low motivation and self-esteem, and the rewards of social media may keep them from exercise and actual social engagement that are critical to their treatment. Youth with eating disorders are especially prone to critical comparison of themselves to others, feeding their distorted body images. Help your patients with these common illnesses to be aware of how social media may make their treatment harder, rather than being the source of relief it may feel like.

Protect their health

For all young people, too much time spent in virtual activities and passive media consumption may not leave enough time to explore potential interests, talents, or relationships. These are important activities throughout life, but they are the central developmental tasks of adolescence. They also need 8-10 hours of sleep nightly and regular exercise. And of course, they have homework! Help them to think about how to use their time wisely to support satisfying relationships and activities, with time for relaxation and good health.

Keep parents in the room for these discussions

State that most of us have difficulty putting down our phones. Children and teens need adults who model striving for balance in all areas of choice. Just as we try to teach them to make good choices about food, getting excellent nutrition while still valuing taste and pleasure, we can talk about how to balance virtual activities with actual activities, work with play, and effort with relaxation. You can help expand your young patients’ self-awareness, acknowledge the fun and utility of their digital time, and enhance their sense of how we must all learn how to put screens down sometimes. In so doing, you can help families to ensure that they are engaging with the digital tools and toys available to all of us in ways that can support their health and well-being.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

References

1. Geena Davis Institute on Gender and Media. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Teens and Tweens, 2015.

2. Abi-Jaoude E et al. CMAJ 2020;192(6):E136-41.

3. Boers E et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;65(3):206-8.

4. Kelly Y et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jan 4;6:59-68.

5. Vidal C et al. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2020 May;32(3):235-53.

6. Coyne SM et al. J Res Adolescence. 2019;29(4):897-907.

Transplanted pig hearts functioned normally in deceased persons on ventilator support

A team of surgeons successfully transplanted genetically engineered pig hearts into two recently deceased people whose bodies were being maintained on ventilatory support – not in the hope of restoring life, but as a proof-of-concept experiment in xenotransplantation that could eventually help to ease the critical shortage of donor organs.

The surgeries were performed on June 16 and July 6, 2022, using porcine hearts from animals genetically engineered to prevent organ rejection and promote adaptive immunity by human recipients

without utilizing unapproved devices or techniques or medications,” said Nader Moazami, MD, surgical director of heart transplantation and chief of the division of heart and lung transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at NYU Langone Health, New York.

Through 72 hours of postoperative monitoring “we evaluated the heart for functionality and the heart function was completely normal with excellent contractility,” he said at a press briefing announcing early results of the experimental program.

He acknowledged that for the first of the two procedures some surgical modification of the pig heart was required, primarily because of size differences between the donor and recipient.

“Nevertheless, we learned a tremendous amount from the first operation, and when that experience was translated into the second operation it even performed better,” he said.

Alex Reyentovich, MD, medical director of heart transplantation and director of the NYU Langone advanced heart failure program noted that “there are 6 million individuals with heart failure in the United States. About 100,000 of those individuals have end-stage heart failure, and we only do about 3,500 heart transplants a year in the United States, so we have a tremendous deficiency in organs, and there are many people dying waiting for a heart.”

Infection protocols

To date there has been only one xenotransplant of a genetically modified pig heart into a living human recipient, David Bennett Sr., age 57. The surgery, performed at the University of Maryland in January 2022, was initially successful, with the patient able to sit up in bed a few days after the procedure, and the heart performing like a “rock star” according to transplant surgeon Bartley Griffith, MD.

However, Mr. Bennett died 2 months after the procedure from compromise of the organ by an as yet undetermined cause, of which one may have been the heart's infection by porcine cytomegalovirus (CMV).

The NYU team, mindful of this potential setback, used more sensitive assays to screen the donor organs for porcine CMV, and implemented protocols to prevent and to monitor for potential zoonotic transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus.

The procedure used a dedicated operating room and equipment that will not be used for clinical procedures, the team emphasized.

An organ transplant specialist who was not involved in the study commented that there can be unwelcome surprises even with the most rigorous infection prophylaxis protocols.

“I think these are important steps, but they don’t resolve the question of infectious risk. Sometimes viruses or latent infections are only manifested later,” said Jay A. Fishman, MD, associate director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Transplant Center and director of the transplant infectious diseases and compromised host program at the hospital, which is in Boston.

“I think these are important steps, but as you may recall from the Maryland heart transplant experience, when porcine cytomegalovirus was activated, it was a long way into that patient’s course, and so we just don’t know whether something would have been reactivated later,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Fishman noted that experience with xenotransplantation at the University of Maryland and other centers has suggested that immunosuppressive regimens used for human-to-human transplants may not be suited for animal-to-human grafts.

The hearts were taken from pigs genetically modified with knockouts of four porcine genes to prevent rejection – including a gene for a growth hormone that would otherwise cause the heart to continue to expand in the recipient’s chest – and with the addition of six human transgenes encoding for expression of proteins regulating biologic pathways that might be disrupted by incompatibilities across species.

Vietnam veteran

The organ recipients were recently deceased patients who had expressed the clear wish to be organ donors but whose organs were for clinical reasons unsuitable for transplant.

The first recipient was Lawrence Kelly, a Vietnam War veteran and welder who died from heart failure at the age of 72.

“He was an organ donor, and would be so happy to know how much his contribution to this research will help people like him with this heart disease. He was a hero his whole life, and he went out a hero,” said Alice Michael, Mr. Kelly’s partner of 33 years, who also spoke at the briefing.

“It was, I think, one of the most incredible things to see a pig heart pounding away and beating inside the chest of a human being,” said Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Transplant Institute, and himself a heart transplant recipient.

Dr. Fishman said he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was updated on 7/12/22 and 7/14/22.

A team of surgeons successfully transplanted genetically engineered pig hearts into two recently deceased people whose bodies were being maintained on ventilatory support – not in the hope of restoring life, but as a proof-of-concept experiment in xenotransplantation that could eventually help to ease the critical shortage of donor organs.

The surgeries were performed on June 16 and July 6, 2022, using porcine hearts from animals genetically engineered to prevent organ rejection and promote adaptive immunity by human recipients

without utilizing unapproved devices or techniques or medications,” said Nader Moazami, MD, surgical director of heart transplantation and chief of the division of heart and lung transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at NYU Langone Health, New York.

Through 72 hours of postoperative monitoring “we evaluated the heart for functionality and the heart function was completely normal with excellent contractility,” he said at a press briefing announcing early results of the experimental program.

He acknowledged that for the first of the two procedures some surgical modification of the pig heart was required, primarily because of size differences between the donor and recipient.

“Nevertheless, we learned a tremendous amount from the first operation, and when that experience was translated into the second operation it even performed better,” he said.

Alex Reyentovich, MD, medical director of heart transplantation and director of the NYU Langone advanced heart failure program noted that “there are 6 million individuals with heart failure in the United States. About 100,000 of those individuals have end-stage heart failure, and we only do about 3,500 heart transplants a year in the United States, so we have a tremendous deficiency in organs, and there are many people dying waiting for a heart.”

Infection protocols

To date there has been only one xenotransplant of a genetically modified pig heart into a living human recipient, David Bennett Sr., age 57. The surgery, performed at the University of Maryland in January 2022, was initially successful, with the patient able to sit up in bed a few days after the procedure, and the heart performing like a “rock star” according to transplant surgeon Bartley Griffith, MD.

However, Mr. Bennett died 2 months after the procedure from compromise of the organ by an as yet undetermined cause, of which one may have been the heart's infection by porcine cytomegalovirus (CMV).

The NYU team, mindful of this potential setback, used more sensitive assays to screen the donor organs for porcine CMV, and implemented protocols to prevent and to monitor for potential zoonotic transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus.

The procedure used a dedicated operating room and equipment that will not be used for clinical procedures, the team emphasized.

An organ transplant specialist who was not involved in the study commented that there can be unwelcome surprises even with the most rigorous infection prophylaxis protocols.

“I think these are important steps, but they don’t resolve the question of infectious risk. Sometimes viruses or latent infections are only manifested later,” said Jay A. Fishman, MD, associate director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Transplant Center and director of the transplant infectious diseases and compromised host program at the hospital, which is in Boston.

“I think these are important steps, but as you may recall from the Maryland heart transplant experience, when porcine cytomegalovirus was activated, it was a long way into that patient’s course, and so we just don’t know whether something would have been reactivated later,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Fishman noted that experience with xenotransplantation at the University of Maryland and other centers has suggested that immunosuppressive regimens used for human-to-human transplants may not be suited for animal-to-human grafts.

The hearts were taken from pigs genetically modified with knockouts of four porcine genes to prevent rejection – including a gene for a growth hormone that would otherwise cause the heart to continue to expand in the recipient’s chest – and with the addition of six human transgenes encoding for expression of proteins regulating biologic pathways that might be disrupted by incompatibilities across species.

Vietnam veteran

The organ recipients were recently deceased patients who had expressed the clear wish to be organ donors but whose organs were for clinical reasons unsuitable for transplant.

The first recipient was Lawrence Kelly, a Vietnam War veteran and welder who died from heart failure at the age of 72.

“He was an organ donor, and would be so happy to know how much his contribution to this research will help people like him with this heart disease. He was a hero his whole life, and he went out a hero,” said Alice Michael, Mr. Kelly’s partner of 33 years, who also spoke at the briefing.

“It was, I think, one of the most incredible things to see a pig heart pounding away and beating inside the chest of a human being,” said Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Transplant Institute, and himself a heart transplant recipient.

Dr. Fishman said he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was updated on 7/12/22 and 7/14/22.

A team of surgeons successfully transplanted genetically engineered pig hearts into two recently deceased people whose bodies were being maintained on ventilatory support – not in the hope of restoring life, but as a proof-of-concept experiment in xenotransplantation that could eventually help to ease the critical shortage of donor organs.

The surgeries were performed on June 16 and July 6, 2022, using porcine hearts from animals genetically engineered to prevent organ rejection and promote adaptive immunity by human recipients

without utilizing unapproved devices or techniques or medications,” said Nader Moazami, MD, surgical director of heart transplantation and chief of the division of heart and lung transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at NYU Langone Health, New York.

Through 72 hours of postoperative monitoring “we evaluated the heart for functionality and the heart function was completely normal with excellent contractility,” he said at a press briefing announcing early results of the experimental program.

He acknowledged that for the first of the two procedures some surgical modification of the pig heart was required, primarily because of size differences between the donor and recipient.

“Nevertheless, we learned a tremendous amount from the first operation, and when that experience was translated into the second operation it even performed better,” he said.

Alex Reyentovich, MD, medical director of heart transplantation and director of the NYU Langone advanced heart failure program noted that “there are 6 million individuals with heart failure in the United States. About 100,000 of those individuals have end-stage heart failure, and we only do about 3,500 heart transplants a year in the United States, so we have a tremendous deficiency in organs, and there are many people dying waiting for a heart.”

Infection protocols

To date there has been only one xenotransplant of a genetically modified pig heart into a living human recipient, David Bennett Sr., age 57. The surgery, performed at the University of Maryland in January 2022, was initially successful, with the patient able to sit up in bed a few days after the procedure, and the heart performing like a “rock star” according to transplant surgeon Bartley Griffith, MD.

However, Mr. Bennett died 2 months after the procedure from compromise of the organ by an as yet undetermined cause, of which one may have been the heart's infection by porcine cytomegalovirus (CMV).

The NYU team, mindful of this potential setback, used more sensitive assays to screen the donor organs for porcine CMV, and implemented protocols to prevent and to monitor for potential zoonotic transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus.

The procedure used a dedicated operating room and equipment that will not be used for clinical procedures, the team emphasized.

An organ transplant specialist who was not involved in the study commented that there can be unwelcome surprises even with the most rigorous infection prophylaxis protocols.

“I think these are important steps, but they don’t resolve the question of infectious risk. Sometimes viruses or latent infections are only manifested later,” said Jay A. Fishman, MD, associate director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Transplant Center and director of the transplant infectious diseases and compromised host program at the hospital, which is in Boston.

“I think these are important steps, but as you may recall from the Maryland heart transplant experience, when porcine cytomegalovirus was activated, it was a long way into that patient’s course, and so we just don’t know whether something would have been reactivated later,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Fishman noted that experience with xenotransplantation at the University of Maryland and other centers has suggested that immunosuppressive regimens used for human-to-human transplants may not be suited for animal-to-human grafts.

The hearts were taken from pigs genetically modified with knockouts of four porcine genes to prevent rejection – including a gene for a growth hormone that would otherwise cause the heart to continue to expand in the recipient’s chest – and with the addition of six human transgenes encoding for expression of proteins regulating biologic pathways that might be disrupted by incompatibilities across species.

Vietnam veteran

The organ recipients were recently deceased patients who had expressed the clear wish to be organ donors but whose organs were for clinical reasons unsuitable for transplant.

The first recipient was Lawrence Kelly, a Vietnam War veteran and welder who died from heart failure at the age of 72.

“He was an organ donor, and would be so happy to know how much his contribution to this research will help people like him with this heart disease. He was a hero his whole life, and he went out a hero,” said Alice Michael, Mr. Kelly’s partner of 33 years, who also spoke at the briefing.

“It was, I think, one of the most incredible things to see a pig heart pounding away and beating inside the chest of a human being,” said Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Transplant Institute, and himself a heart transplant recipient.

Dr. Fishman said he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was updated on 7/12/22 and 7/14/22.

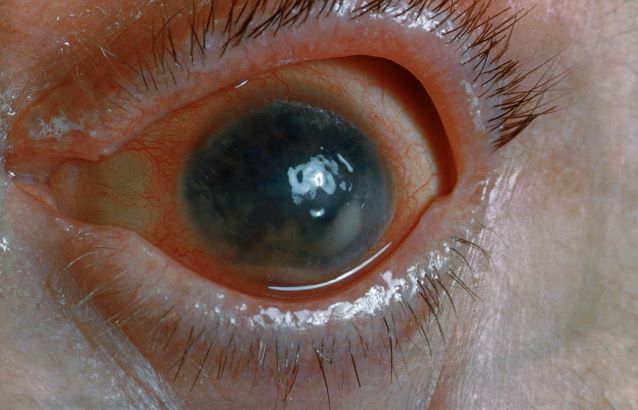

Pain and photophobia

On the basis of the patient's medical history and presentation, this is probably a case of uveitis, a common extra-articular manifestation of psoriatic disease. In fact, the presence of uveitis can help distinguish PsA from osteoarthritis. Uveitis is characterized by inflammation of the uvea tract, with the retina, optic nerve, vitreous body, and sclera potentially becoming inflamed as well. Among patients with PsA, the prevalence of uveitis rises with ongoing disease duration, though the condition may also precede the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis, and is common among patients with severe psoriatic disease in Western and Asian populations. Overall, the prevalence of uveitis has been estimated to be 6%-9%. HLA-B27 genotype is strongly associated with uveitis in patients with concomitant PsA.

Symptoms of uveitis, as seen in the present case, include blurred vision, photophobia, pain, and ciliary flush. The condition is classified as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis, with the majority of cases diagnosed as anterior. In anterior uveitis, the inflamed pupil may become constricted or take on an irregular shape caused by iris adhesions to the anterior lens capsule. Uveitis in PsA is bilateral and has a chronic relapsing course. Onset is typically insidious.

Workup for uveitis should comprise visual acuity testing, slit lamp biomicroscopy, measurement of intraocular pressures, and a dilated eye exam. Conditions in the differential which threaten a patient's sight include retinal vasculitis, vitritis, cystoid macular edema, Behçet disease, and tubulo-interstitial nephritis. Other autoimmune diseases which can cause uveitis with systemic manifestations (multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, lupus) should be investigated. Infectious causes must also be eliminated. However, considering this patient's history of psoriatic disease, uveitis should be highly suspected.

Uveitis demands urgent treatment to control ocular inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are the recommended first-line and second-line treatment for PsA, including in patients with complications such as uveitis. However, etanercept should not be used as it is less effective than adalimumab or other TNF inhibitors for uveitis. Because uveitis may sometimes respond to MTX therapy, patients with severe PsA may use a biologic agent in combination with MTX if they have had a partial response to current MTX therapy, as recommended by the American College of Rheumatology.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's medical history and presentation, this is probably a case of uveitis, a common extra-articular manifestation of psoriatic disease. In fact, the presence of uveitis can help distinguish PsA from osteoarthritis. Uveitis is characterized by inflammation of the uvea tract, with the retina, optic nerve, vitreous body, and sclera potentially becoming inflamed as well. Among patients with PsA, the prevalence of uveitis rises with ongoing disease duration, though the condition may also precede the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis, and is common among patients with severe psoriatic disease in Western and Asian populations. Overall, the prevalence of uveitis has been estimated to be 6%-9%. HLA-B27 genotype is strongly associated with uveitis in patients with concomitant PsA.

Symptoms of uveitis, as seen in the present case, include blurred vision, photophobia, pain, and ciliary flush. The condition is classified as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis, with the majority of cases diagnosed as anterior. In anterior uveitis, the inflamed pupil may become constricted or take on an irregular shape caused by iris adhesions to the anterior lens capsule. Uveitis in PsA is bilateral and has a chronic relapsing course. Onset is typically insidious.

Workup for uveitis should comprise visual acuity testing, slit lamp biomicroscopy, measurement of intraocular pressures, and a dilated eye exam. Conditions in the differential which threaten a patient's sight include retinal vasculitis, vitritis, cystoid macular edema, Behçet disease, and tubulo-interstitial nephritis. Other autoimmune diseases which can cause uveitis with systemic manifestations (multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, lupus) should be investigated. Infectious causes must also be eliminated. However, considering this patient's history of psoriatic disease, uveitis should be highly suspected.

Uveitis demands urgent treatment to control ocular inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are the recommended first-line and second-line treatment for PsA, including in patients with complications such as uveitis. However, etanercept should not be used as it is less effective than adalimumab or other TNF inhibitors for uveitis. Because uveitis may sometimes respond to MTX therapy, patients with severe PsA may use a biologic agent in combination with MTX if they have had a partial response to current MTX therapy, as recommended by the American College of Rheumatology.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's medical history and presentation, this is probably a case of uveitis, a common extra-articular manifestation of psoriatic disease. In fact, the presence of uveitis can help distinguish PsA from osteoarthritis. Uveitis is characterized by inflammation of the uvea tract, with the retina, optic nerve, vitreous body, and sclera potentially becoming inflamed as well. Among patients with PsA, the prevalence of uveitis rises with ongoing disease duration, though the condition may also precede the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis, and is common among patients with severe psoriatic disease in Western and Asian populations. Overall, the prevalence of uveitis has been estimated to be 6%-9%. HLA-B27 genotype is strongly associated with uveitis in patients with concomitant PsA.

Symptoms of uveitis, as seen in the present case, include blurred vision, photophobia, pain, and ciliary flush. The condition is classified as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis, with the majority of cases diagnosed as anterior. In anterior uveitis, the inflamed pupil may become constricted or take on an irregular shape caused by iris adhesions to the anterior lens capsule. Uveitis in PsA is bilateral and has a chronic relapsing course. Onset is typically insidious.

Workup for uveitis should comprise visual acuity testing, slit lamp biomicroscopy, measurement of intraocular pressures, and a dilated eye exam. Conditions in the differential which threaten a patient's sight include retinal vasculitis, vitritis, cystoid macular edema, Behçet disease, and tubulo-interstitial nephritis. Other autoimmune diseases which can cause uveitis with systemic manifestations (multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, lupus) should be investigated. Infectious causes must also be eliminated. However, considering this patient's history of psoriatic disease, uveitis should be highly suspected.

Uveitis demands urgent treatment to control ocular inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are the recommended first-line and second-line treatment for PsA, including in patients with complications such as uveitis. However, etanercept should not be used as it is less effective than adalimumab or other TNF inhibitors for uveitis. Because uveitis may sometimes respond to MTX therapy, patients with severe PsA may use a biologic agent in combination with MTX if they have had a partial response to current MTX therapy, as recommended by the American College of Rheumatology.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 48-year-old male patient presents with blurred vision, pain, and photophobia. He recently had a routine visit with an ophthalmologist, which was normal. The affected pupil appears irregular in shape. The anterior chamber appears foggy. Local ciliary flush is observed on slit lamp exam. The physical examination is also notable for axial arthropathy. The patient has an 11-year history of moderate to severe psoriatic arthritis (PsA) which he typically manages with methotrexate (MTX) therapy, to which he has had a partial response. He was initially diagnosed when he presented with worsening psoriasis and enthesitis on the insertion sites of the plantar fascia, as well as dactylitis.

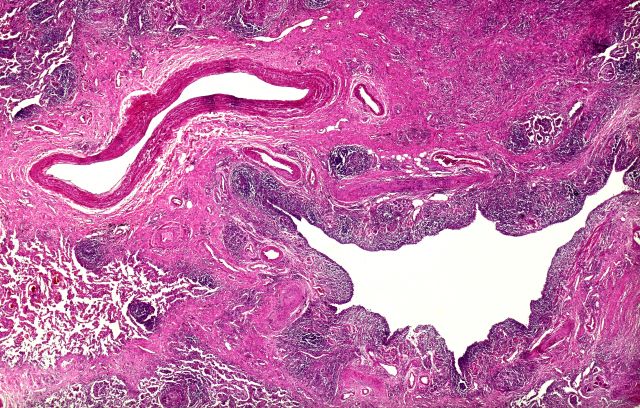

Dry cough and dyspnea

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 58-year-old man with a 20-year–pack history of smoking initially presented with a persistent dry cough and dyspnea. Clubbing was noted on physical examination and breath sounds in the right upper lung were weak. Other than hypertension, which the patient manages with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, medical history is unremarkable. The patient notes that this medication has always made him cough, but dyspnea has only developed over the past 6 weeks. Respiratory symptoms prompted a chest radiograph which revealed a mass in the upper lobe of the right lung. Transbronchial lung biopsy of the right lung reveals components of adenocarcinoma; the specimen is otherwise squamous.

Drugging the undruggable

including 68% of pancreatic tumors and 20% of all non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLC).

We now have a treatment – sotorasib – for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC that is driven by a KRAS mutation (G12C). And, now, there is a second treatment – adagrasib – under study, which, according to a presentation recently made at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, looks promising.

Ras is a membrane-bound regulatory protein (G protein) belonging to the family of guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). Ras functions as a guanosine diphosphate/triphosphate binary switch by cycling between the active GTP-bound and the inactive GDP-bound states in response to extracellular stimuli. The KRAS (G12C) mutation affects the active form of KRAS and results in abnormally high concentrations of GTP-bound KRAS leading to hyperactivation of downstream oncogenic pathways and uncontrolled cell growth, specifically of ERK and MEK signaling pathways.

At the ASCO annual meeting in June, Spira and colleagues reported the results of cohort A of the KRYSTAL-1 study evaluating adagrasib as second-line therapy patients with advanced solid tumors harboring a KRAS (G12C) mutation. Like sotorasib, adagrasib is a KRAS (G12C) inhibitor that irreversibly and selectively binds KRAS (G12C), locking it in its inactive state. In this study, patients had to have failed first-line chemotherapy and immunotherapy with 43% of lung cancer patients responding. The 12-month overall survival (OS) was 51%, median overall survival was 12.6 and median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.5 months. Twenty-five patients with KRAS (G12C)–mutant NSCLC and active, untreated central nervous system metastases received adagrasib in a phase 1b cohort. The intracranial overall response rate was 31.6% and median intracranial PFS was 4.2 months. Systemic ORR was 35.0% (7/20), the disease control rate was 80.0% (16/20) and median duration of response was 9.6 months. Based on these data, a phase 3 trial evaluating adagrasib monotherapy versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with KRAS (G12C) mutant NSCLC is ongoing.

The Food and Drug Administration approval of sotorasib in 2021 was, in part, based on the results of a single-arm, phase 2, second-line study of patients who had previously received platinum-based chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy. An ORR rate of 37.1% was reported with a median PFS of 6.8 months and median OS of 12.5 months leading to the FDA approval. Responses were observed across the range of baseline PD-L1 expression levels: 48% of PD-L1 negative, 39% with PD-L1 between 1%-49%, and 22% of patients with a PD-L1 of greater than 50% having a response.

The major toxicities observed in these studies were gastrointestinal (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting) and hepatic (elevated liver enzymes). About 97% of patients on adagrasib experienced any treatment-related adverse events, and 43% experienced a grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse event leading to dose reduction in 52% of patients, a dose interruption in 61% of patients, and a 7% discontinuation rate. About 70% of patients treated with sotorasib had a treatment-related adverse event of any grade, and 21% reported grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events.

A subgroup in the KRYSTAL-1 trial reported an intracranial ORR of 32% in patients with active, untreated CNS metastases. Median overall survival has not yet reached concordance between systemic and intracranial disease control was 88%. In addition, preliminary data from two patients with untreated CNS metastases from a phase 1b cohort found cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of adagrasib with a mean ratio of unbound brain-to-plasma concentration of 0.47, which is comparable or exceeds values for known CNS-penetrant tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Unfortunately, KRAS (G12C) is not the only KRAS mutation out there. There are a myriad of others, such as G12V and G12D. Hopefully, we will be seeing more drugs aimed at this set of important mutations. Another question, of course, is when and if these drugs will move to the first-line setting.

Dr. Schiller is a medical oncologist and founding member of Oncologists United for Climate and Health. She is a former board member of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and a current board member of the Lung Cancer Research Foundation.

including 68% of pancreatic tumors and 20% of all non–small cell lung cancers (NSCLC).

We now have a treatment – sotorasib – for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC that is driven by a KRAS mutation (G12C). And, now, there is a second treatment – adagrasib – under study, which, according to a presentation recently made at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, looks promising.

Ras is a membrane-bound regulatory protein (G protein) belonging to the family of guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). Ras functions as a guanosine diphosphate/triphosphate binary switch by cycling between the active GTP-bound and the inactive GDP-bound states in response to extracellular stimuli. The KRAS (G12C) mutation affects the active form of KRAS and results in abnormally high concentrations of GTP-bound KRAS leading to hyperactivation of downstream oncogenic pathways and uncontrolled cell growth, specifically of ERK and MEK signaling pathways.