User login

Risankizumab Effective in Resolving Enthesitis and Dactylitis in PsA

Key clinical point: Risankizumab vs placebo led to higher resolution rates for enthesitis and dactylitis at 24 weeks in patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which were sustained through 52 weeks.

Major finding: At week 24, a higher proportion of risankizumab- vs placebo-treated patients achieved resolution of enthesitis (48.4% vs 34.8%; P < .001), dactylitis (68.1% vs 51.0%; P < .001), and enthesitis + dactylitis (42.2% vs 28.6%; P < .05). More than 50% of patients who continuously received risankizumab or switched from placebo to risankizumab at week 24 achieved resolution of enthesitis, dactylitis, or both.

Study details: This integrated post hoc analysis of the KEEPsAKE 1 and KEEPsAKE 2 trials included 1407 patients with PsA and previous inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs who received risankizumab or placebo with crossover to risankizumab at week 24.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Four authors declared being employees or holding stocks, stock options, or patents of AbbVie. Five authors declared ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Kwatra SG, Khattri S, Amin AZ, et al. Enthesitis and dactylitis resolution with risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: Integrated analysis of the randomized KEEPsAKE 1 and 2 trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1517-1530 (May 13). doi: 10.1007/s13555-024-01174-4 Source

Key clinical point: Risankizumab vs placebo led to higher resolution rates for enthesitis and dactylitis at 24 weeks in patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which were sustained through 52 weeks.

Major finding: At week 24, a higher proportion of risankizumab- vs placebo-treated patients achieved resolution of enthesitis (48.4% vs 34.8%; P < .001), dactylitis (68.1% vs 51.0%; P < .001), and enthesitis + dactylitis (42.2% vs 28.6%; P < .05). More than 50% of patients who continuously received risankizumab or switched from placebo to risankizumab at week 24 achieved resolution of enthesitis, dactylitis, or both.

Study details: This integrated post hoc analysis of the KEEPsAKE 1 and KEEPsAKE 2 trials included 1407 patients with PsA and previous inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs who received risankizumab or placebo with crossover to risankizumab at week 24.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Four authors declared being employees or holding stocks, stock options, or patents of AbbVie. Five authors declared ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Kwatra SG, Khattri S, Amin AZ, et al. Enthesitis and dactylitis resolution with risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: Integrated analysis of the randomized KEEPsAKE 1 and 2 trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1517-1530 (May 13). doi: 10.1007/s13555-024-01174-4 Source

Key clinical point: Risankizumab vs placebo led to higher resolution rates for enthesitis and dactylitis at 24 weeks in patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which were sustained through 52 weeks.

Major finding: At week 24, a higher proportion of risankizumab- vs placebo-treated patients achieved resolution of enthesitis (48.4% vs 34.8%; P < .001), dactylitis (68.1% vs 51.0%; P < .001), and enthesitis + dactylitis (42.2% vs 28.6%; P < .05). More than 50% of patients who continuously received risankizumab or switched from placebo to risankizumab at week 24 achieved resolution of enthesitis, dactylitis, or both.

Study details: This integrated post hoc analysis of the KEEPsAKE 1 and KEEPsAKE 2 trials included 1407 patients with PsA and previous inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs who received risankizumab or placebo with crossover to risankizumab at week 24.

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie. Four authors declared being employees or holding stocks, stock options, or patents of AbbVie. Five authors declared ties with various sources, including AbbVie.

Source: Kwatra SG, Khattri S, Amin AZ, et al. Enthesitis and dactylitis resolution with risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: Integrated analysis of the randomized KEEPsAKE 1 and 2 trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:1517-1530 (May 13). doi: 10.1007/s13555-024-01174-4 Source

Real-World Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Difficult-To-Treat PsA

Key clinical point: This real-world study showed that almost 1 in 6 patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) had potentially difficult-to-treat (D2T) disease, which was associated with extensive psoriasis, higher body mass index (BMI), and a history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Major finding: Of 467 patients, 16.5% had D2T PsA. Compared to non-D2T patients, those with D2T disease were more likely to have extensive psoriasis at diagnosis (odds ratio [OR] 5.05; P < .0001), higher BMI (OR 1.07; P = .023), and a history of IBD (OR 1.22; P = .026).

Study details: This study analyzed 467 patients with PsA from a Greek registry who had ≥6-months of disease duration, progressed on disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs with different mechanisms of actions, and had disease activity index for PsA > 14 or were not at minimal disease activity.

Disclosures: The registry was funded by the Greek (Hellenic) Rheumatology Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Vassilakis KD, Papagoras C, Fytanidis N, et al. Identification and characteristics of patients with potential difficult-to-treat Psoriatic Arthritis: Exploratory analyses of the Greek PsA registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024 (May 17). doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keae263 Source

Key clinical point: This real-world study showed that almost 1 in 6 patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) had potentially difficult-to-treat (D2T) disease, which was associated with extensive psoriasis, higher body mass index (BMI), and a history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Major finding: Of 467 patients, 16.5% had D2T PsA. Compared to non-D2T patients, those with D2T disease were more likely to have extensive psoriasis at diagnosis (odds ratio [OR] 5.05; P < .0001), higher BMI (OR 1.07; P = .023), and a history of IBD (OR 1.22; P = .026).

Study details: This study analyzed 467 patients with PsA from a Greek registry who had ≥6-months of disease duration, progressed on disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs with different mechanisms of actions, and had disease activity index for PsA > 14 or were not at minimal disease activity.

Disclosures: The registry was funded by the Greek (Hellenic) Rheumatology Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Vassilakis KD, Papagoras C, Fytanidis N, et al. Identification and characteristics of patients with potential difficult-to-treat Psoriatic Arthritis: Exploratory analyses of the Greek PsA registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024 (May 17). doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keae263 Source

Key clinical point: This real-world study showed that almost 1 in 6 patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) had potentially difficult-to-treat (D2T) disease, which was associated with extensive psoriasis, higher body mass index (BMI), and a history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Major finding: Of 467 patients, 16.5% had D2T PsA. Compared to non-D2T patients, those with D2T disease were more likely to have extensive psoriasis at diagnosis (odds ratio [OR] 5.05; P < .0001), higher BMI (OR 1.07; P = .023), and a history of IBD (OR 1.22; P = .026).

Study details: This study analyzed 467 patients with PsA from a Greek registry who had ≥6-months of disease duration, progressed on disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs with different mechanisms of actions, and had disease activity index for PsA > 14 or were not at minimal disease activity.

Disclosures: The registry was funded by the Greek (Hellenic) Rheumatology Society. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Vassilakis KD, Papagoras C, Fytanidis N, et al. Identification and characteristics of patients with potential difficult-to-treat Psoriatic Arthritis: Exploratory analyses of the Greek PsA registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024 (May 17). doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keae263 Source

Low Stress Resilience in Adolescence Raises Risk for Psoriatic Arthritis

Key clinical point: Low stress resilience during adolescence increased the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA) later in life in a cohort of >1.6 million men who were followed up for up to 51 years.

Major finding: Over nearly 51 years of follow-up, 9433 (0.6%) men developed first onset PsA. Low vs high stress resilience increased the risk for new-onset PsA by 23% in the overall cohort (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.23; 95% CI 1.15-1.32) and 53% in the subgroup of patients who were hospitalized due to severe PsA (aHR 1.53; 95% CI 1.32-1.77).

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 1,669,422 men from the Swedish Military Service Conscription Register, of whom 20.4%, 58.0%, and 21.5% had low, medium, and high stress resilience levels, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health and other sources. One author declared receiving honoraria as consultant or speaker from various sources. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Laskowski M, Schiöler L, Åberg M, et al. Influence of stress resilience in adolescence on long-term risk of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis among men: A prospective register-based cohort study in Sweden. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024 (May 20). doi: 10.1111/jdv.20069 Source

Key clinical point: Low stress resilience during adolescence increased the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA) later in life in a cohort of >1.6 million men who were followed up for up to 51 years.

Major finding: Over nearly 51 years of follow-up, 9433 (0.6%) men developed first onset PsA. Low vs high stress resilience increased the risk for new-onset PsA by 23% in the overall cohort (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.23; 95% CI 1.15-1.32) and 53% in the subgroup of patients who were hospitalized due to severe PsA (aHR 1.53; 95% CI 1.32-1.77).

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 1,669,422 men from the Swedish Military Service Conscription Register, of whom 20.4%, 58.0%, and 21.5% had low, medium, and high stress resilience levels, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health and other sources. One author declared receiving honoraria as consultant or speaker from various sources. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Laskowski M, Schiöler L, Åberg M, et al. Influence of stress resilience in adolescence on long-term risk of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis among men: A prospective register-based cohort study in Sweden. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024 (May 20). doi: 10.1111/jdv.20069 Source

Key clinical point: Low stress resilience during adolescence increased the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis (PsA) later in life in a cohort of >1.6 million men who were followed up for up to 51 years.

Major finding: Over nearly 51 years of follow-up, 9433 (0.6%) men developed first onset PsA. Low vs high stress resilience increased the risk for new-onset PsA by 23% in the overall cohort (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 1.23; 95% CI 1.15-1.32) and 53% in the subgroup of patients who were hospitalized due to severe PsA (aHR 1.53; 95% CI 1.32-1.77).

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 1,669,422 men from the Swedish Military Service Conscription Register, of whom 20.4%, 58.0%, and 21.5% had low, medium, and high stress resilience levels, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health and other sources. One author declared receiving honoraria as consultant or speaker from various sources. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Laskowski M, Schiöler L, Åberg M, et al. Influence of stress resilience in adolescence on long-term risk of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis among men: A prospective register-based cohort study in Sweden. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024 (May 20). doi: 10.1111/jdv.20069 Source

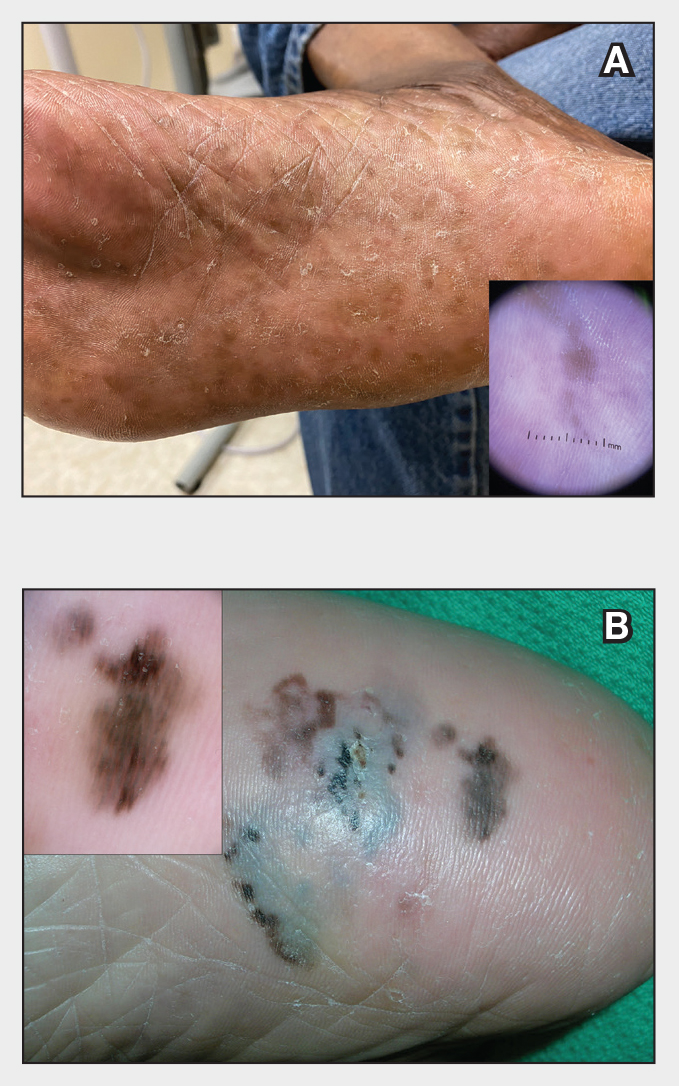

Reticulated Brownish Erythema on the Lower Back

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Based on the patient's long-standing history of back pain treated with heating pads as well as the normal laboratory findings and skin examination, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI) was made.

Erythema ab igne presents as reticulated brownish erythema or hyperpigmentation on sites exposed to prolonged use of heat sources such as heating pads, laptops, and space heaters. Erythema ab igne most commonly affects the lower back, thighs, or legs1-6; however, EAI can appear on atypical sites such as the forehead and eyebrows due to newer technology (eg, virtual reality headsets).7 The level of heat required for EAI to occur is below the threshold for thermal burns (<45 °C [113 °F]).1 Erythema ab igne can occur at any age, and woman are more commonly affected than men.8 The pathophysiology currently is unknown; however, recurrent and prolonged heat exposure may damage superficial vessels. As a result, hemosiderin accumulates in the skin, and hyperpigmentation subsequently occurs.9

The diagnosis of EAI is clinical, and early stages of the rash present as blanching reticulated erythema in areas associated with heat exposure. If the offending source of heat is not removed, EAI can progress to nonblanching, fixed, hyperpigmented plaques with skin atrophy, bullae, or hyperkeratosis. Patients often are asymptomatic; however, mild burning may occur.2 Histopathology reveals cellular atypia, epidermal atrophy, dilation of dermal blood vessels, a minute inflammatory infiltrate, and keratinocyte apoptosis.10 Skin biopsy may be necessary in cases of suspected malignancy due to chronic heat exposure. Lesions that ulcerate or evolve should raise suspicion for malignancy.11 Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy associated with EAI; other malignancies that may manifest include basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,12-14

Erythema ab igne often is mistaken for livedo reticularis, which appears more erythematous without hyperpigmentation or epidermal changes and may be associated with a pathologic state.15 The differential diagnosis in our patient, who was in her 40s with a history of fatigue and joint pain, included livedo reticularis associated with lupus; however, the history of heating pad use, normal laboratory findings, and presence of epidermal changes suggested EAI. Lupus typically affects the hand and knee joints.16 Additionally, livedo reticularis more commonly appears on the legs.15

Other differentials for EAI include livedo racemosa, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and cutis marmorata. Livedo racemosa presents with broken rings of erythema in young to middle-aged women and primarily affects the trunk and proximal limbs. It is associated with an underlying condition such as polyarteritis nodosa and less commonly with lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid or Sneddon syndrome.15,17 Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma typically manifests with poikilodermatous patches larger than the palm, especially in covered areas of skin.18 Cutis marmorata is transient and temperature dependent.9

The key intervention for EAI is removal of the offending heat source.2 Patients should be counseled that the erythema and hyperpigmentation may take months to years to resolve. Topical hydroquinone or tretinoin may be used in cases of persistent hyperpigmentation.19 Patients who continue to use heating pads for long-standing pain should be advised to limit their use to short intervals without occlusion. If malignancy is a concern, a biopsy should be performed.20

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Patel DP. The evolving nomenclature of erythema ab igne-redness from fire. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2021

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Haleem Z, Philip J, Muhammad S. Erythema ab igne: a rare presentation of toasted skin syndrome with the use of a space heater. Cureus. 2021;13:e13401. doi:10.7759/cureus.13401

- Moreau T, Benzaquen M, Gueissaz F. Erythema ab igne after using a virtual reality headset: a new phenomenon to know. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E932-E933. doi:10.1111/jdv.18371

- Ozturk M, An I. Clinical features and etiology of patients with erythema ab igne: a retrospective multicenter study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1774-1779. doi:10.1111/jocd.13210

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:E236-E238. doi:10.1097 /PEC.0000000000001460

- Wells A, Desai A, Rudnick EW, et al. Erythema ab igne with features resembling keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:151-153. doi:10.1111/cup.13885

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Daneshvar E, Seraji S, Kamyab-Hesari K, et al. Basal cell carcinoma associated with erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt3kz985b4.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, et al. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:315-321. doi:10.4103 /2229-5178.164493

- Grossman JM. Lupus arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:495-506. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2009.04.003

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:1085-1102. doi:10.1002/ajh.24876

- Pennitz A, Kinberger M, Avila Valle G, et al. Self-applied topical interventions for melasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:309-317.

- Sahl WJ, Taira JW. Erythema ab igne: treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:109-110.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Based on the patient's long-standing history of back pain treated with heating pads as well as the normal laboratory findings and skin examination, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI) was made.

Erythema ab igne presents as reticulated brownish erythema or hyperpigmentation on sites exposed to prolonged use of heat sources such as heating pads, laptops, and space heaters. Erythema ab igne most commonly affects the lower back, thighs, or legs1-6; however, EAI can appear on atypical sites such as the forehead and eyebrows due to newer technology (eg, virtual reality headsets).7 The level of heat required for EAI to occur is below the threshold for thermal burns (<45 °C [113 °F]).1 Erythema ab igne can occur at any age, and woman are more commonly affected than men.8 The pathophysiology currently is unknown; however, recurrent and prolonged heat exposure may damage superficial vessels. As a result, hemosiderin accumulates in the skin, and hyperpigmentation subsequently occurs.9

The diagnosis of EAI is clinical, and early stages of the rash present as blanching reticulated erythema in areas associated with heat exposure. If the offending source of heat is not removed, EAI can progress to nonblanching, fixed, hyperpigmented plaques with skin atrophy, bullae, or hyperkeratosis. Patients often are asymptomatic; however, mild burning may occur.2 Histopathology reveals cellular atypia, epidermal atrophy, dilation of dermal blood vessels, a minute inflammatory infiltrate, and keratinocyte apoptosis.10 Skin biopsy may be necessary in cases of suspected malignancy due to chronic heat exposure. Lesions that ulcerate or evolve should raise suspicion for malignancy.11 Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy associated with EAI; other malignancies that may manifest include basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,12-14

Erythema ab igne often is mistaken for livedo reticularis, which appears more erythematous without hyperpigmentation or epidermal changes and may be associated with a pathologic state.15 The differential diagnosis in our patient, who was in her 40s with a history of fatigue and joint pain, included livedo reticularis associated with lupus; however, the history of heating pad use, normal laboratory findings, and presence of epidermal changes suggested EAI. Lupus typically affects the hand and knee joints.16 Additionally, livedo reticularis more commonly appears on the legs.15

Other differentials for EAI include livedo racemosa, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and cutis marmorata. Livedo racemosa presents with broken rings of erythema in young to middle-aged women and primarily affects the trunk and proximal limbs. It is associated with an underlying condition such as polyarteritis nodosa and less commonly with lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid or Sneddon syndrome.15,17 Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma typically manifests with poikilodermatous patches larger than the palm, especially in covered areas of skin.18 Cutis marmorata is transient and temperature dependent.9

The key intervention for EAI is removal of the offending heat source.2 Patients should be counseled that the erythema and hyperpigmentation may take months to years to resolve. Topical hydroquinone or tretinoin may be used in cases of persistent hyperpigmentation.19 Patients who continue to use heating pads for long-standing pain should be advised to limit their use to short intervals without occlusion. If malignancy is a concern, a biopsy should be performed.20

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Based on the patient's long-standing history of back pain treated with heating pads as well as the normal laboratory findings and skin examination, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI) was made.

Erythema ab igne presents as reticulated brownish erythema or hyperpigmentation on sites exposed to prolonged use of heat sources such as heating pads, laptops, and space heaters. Erythema ab igne most commonly affects the lower back, thighs, or legs1-6; however, EAI can appear on atypical sites such as the forehead and eyebrows due to newer technology (eg, virtual reality headsets).7 The level of heat required for EAI to occur is below the threshold for thermal burns (<45 °C [113 °F]).1 Erythema ab igne can occur at any age, and woman are more commonly affected than men.8 The pathophysiology currently is unknown; however, recurrent and prolonged heat exposure may damage superficial vessels. As a result, hemosiderin accumulates in the skin, and hyperpigmentation subsequently occurs.9

The diagnosis of EAI is clinical, and early stages of the rash present as blanching reticulated erythema in areas associated with heat exposure. If the offending source of heat is not removed, EAI can progress to nonblanching, fixed, hyperpigmented plaques with skin atrophy, bullae, or hyperkeratosis. Patients often are asymptomatic; however, mild burning may occur.2 Histopathology reveals cellular atypia, epidermal atrophy, dilation of dermal blood vessels, a minute inflammatory infiltrate, and keratinocyte apoptosis.10 Skin biopsy may be necessary in cases of suspected malignancy due to chronic heat exposure. Lesions that ulcerate or evolve should raise suspicion for malignancy.11 Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy associated with EAI; other malignancies that may manifest include basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,12-14

Erythema ab igne often is mistaken for livedo reticularis, which appears more erythematous without hyperpigmentation or epidermal changes and may be associated with a pathologic state.15 The differential diagnosis in our patient, who was in her 40s with a history of fatigue and joint pain, included livedo reticularis associated with lupus; however, the history of heating pad use, normal laboratory findings, and presence of epidermal changes suggested EAI. Lupus typically affects the hand and knee joints.16 Additionally, livedo reticularis more commonly appears on the legs.15

Other differentials for EAI include livedo racemosa, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and cutis marmorata. Livedo racemosa presents with broken rings of erythema in young to middle-aged women and primarily affects the trunk and proximal limbs. It is associated with an underlying condition such as polyarteritis nodosa and less commonly with lupus erythematosus with antiphospholipid or Sneddon syndrome.15,17 Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma typically manifests with poikilodermatous patches larger than the palm, especially in covered areas of skin.18 Cutis marmorata is transient and temperature dependent.9

The key intervention for EAI is removal of the offending heat source.2 Patients should be counseled that the erythema and hyperpigmentation may take months to years to resolve. Topical hydroquinone or tretinoin may be used in cases of persistent hyperpigmentation.19 Patients who continue to use heating pads for long-standing pain should be advised to limit their use to short intervals without occlusion. If malignancy is a concern, a biopsy should be performed.20

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Patel DP. The evolving nomenclature of erythema ab igne-redness from fire. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2021

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Haleem Z, Philip J, Muhammad S. Erythema ab igne: a rare presentation of toasted skin syndrome with the use of a space heater. Cureus. 2021;13:e13401. doi:10.7759/cureus.13401

- Moreau T, Benzaquen M, Gueissaz F. Erythema ab igne after using a virtual reality headset: a new phenomenon to know. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E932-E933. doi:10.1111/jdv.18371

- Ozturk M, An I. Clinical features and etiology of patients with erythema ab igne: a retrospective multicenter study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1774-1779. doi:10.1111/jocd.13210

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:E236-E238. doi:10.1097 /PEC.0000000000001460

- Wells A, Desai A, Rudnick EW, et al. Erythema ab igne with features resembling keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:151-153. doi:10.1111/cup.13885

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Daneshvar E, Seraji S, Kamyab-Hesari K, et al. Basal cell carcinoma associated with erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt3kz985b4.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, et al. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:315-321. doi:10.4103 /2229-5178.164493

- Grossman JM. Lupus arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:495-506. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2009.04.003

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:1085-1102. doi:10.1002/ajh.24876

- Pennitz A, Kinberger M, Avila Valle G, et al. Self-applied topical interventions for melasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:309-317.

- Sahl WJ, Taira JW. Erythema ab igne: treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:109-110.

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

- Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, et al. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:676-678. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3182871648

- Patel DP. The evolving nomenclature of erythema ab igne-redness from fire. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:685. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.2021

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;126:E1227-E1230. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1390

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Laptop-induced erythema ab igne: report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:5.

- Haleem Z, Philip J, Muhammad S. Erythema ab igne: a rare presentation of toasted skin syndrome with the use of a space heater. Cureus. 2021;13:e13401. doi:10.7759/cureus.13401

- Moreau T, Benzaquen M, Gueissaz F. Erythema ab igne after using a virtual reality headset: a new phenomenon to know. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E932-E933. doi:10.1111/jdv.18371

- Ozturk M, An I. Clinical features and etiology of patients with erythema ab igne: a retrospective multicenter study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1774-1779. doi:10.1111/jocd.13210

- Gmuca S, Yu J, Weiss PF, et al. Erythema ab igne in an adolescent with chronic pain: an alarming cutaneous eruption from heat exposure. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:E236-E238. doi:10.1097 /PEC.0000000000001460

- Wells A, Desai A, Rudnick EW, et al. Erythema ab igne with features resembling keratosis lichenoides chronica. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:151-153. doi:10.1111/cup.13885

- Milchak M, Smucker J, Chung CG, et al. Erythema ab igne due to heating pad use: a case report and review of clinical presentation, prevention, and complications. Case Rep Med. 2016;2016:1862480. doi:10.1155/2016/1862480

- Daneshvar E, Seraji S, Kamyab-Hesari K, et al. Basal cell carcinoma associated with erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030 /qt3kz985b4.

- Jones CS, Tyring SK, Lee PC, et al. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:110-113.

- Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:1080-1081. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.005

- Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, et al. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:315-321. doi:10.4103 /2229-5178.164493

- Grossman JM. Lupus arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:495-506. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2009.04.003

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635. doi:10.7759/cureus.2635

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:1085-1102. doi:10.1002/ajh.24876

- Pennitz A, Kinberger M, Avila Valle G, et al. Self-applied topical interventions for melasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of data from randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:309-317.

- Sahl WJ, Taira JW. Erythema ab igne: treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:109-110.

A 42-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic, erythematous, lacelike rash on the lower back of 8 months’ duration that was first noticed by her husband. The patient had a long-standing history of chronic fatigue and lower back pain treated with acetaminophen, diclofenac gel, and heating pads. Physical examination revealed reticulated brownish erythema confined to the lower back. Laboratory findings were unremarkable.

FDA Expands Repotrectinib Label to All NTRK Gene Fusion+ Solid Tumors

The approval is a label expansion for the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), which received initial clearance in November 2023 for locally advanced or metastatic ROS1-positive non–small cell lung cancer.

NTRK gene fusions are genetic abnormalities wherein part of the NTRK gene fuses with an unrelated gene. The abnormal gene can then produce an oncogenic protein. Although rare, these mutations are found in many cancer types.

The approval, for adult and pediatric patients aged 12 years or older, was based on the single-arm open-label TRIDENT-1 trial in 88 adults with locally advanced or metastatic NTRK gene fusion solid tumors.

In the 40 patients who were TKI-naive, the overall response rate was 58%, and the median duration of response was not estimable. In the 48 patients who had a TKI previously, the overall response rate was 50% and median duration of response was 9.9 months.

In 20% or more of participants, treatment caused dizziness, dysgeusia, peripheral neuropathy, constipation, dyspnea, fatigue, ataxia, cognitive impairment, muscular weakness, and nausea.

Labeling warns of central nervous system reactions, interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis, hepatotoxicity, myalgia with creatine phosphokinase elevation, hyperuricemia, bone fractures, and embryo-fetal toxicity.

The recommended dose is 160 mg orally once daily for 14 days then increased to 160 mg twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Sixty 40-mg capsules cost around $7,644, according to drugs.com.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The approval is a label expansion for the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), which received initial clearance in November 2023 for locally advanced or metastatic ROS1-positive non–small cell lung cancer.

NTRK gene fusions are genetic abnormalities wherein part of the NTRK gene fuses with an unrelated gene. The abnormal gene can then produce an oncogenic protein. Although rare, these mutations are found in many cancer types.

The approval, for adult and pediatric patients aged 12 years or older, was based on the single-arm open-label TRIDENT-1 trial in 88 adults with locally advanced or metastatic NTRK gene fusion solid tumors.

In the 40 patients who were TKI-naive, the overall response rate was 58%, and the median duration of response was not estimable. In the 48 patients who had a TKI previously, the overall response rate was 50% and median duration of response was 9.9 months.

In 20% or more of participants, treatment caused dizziness, dysgeusia, peripheral neuropathy, constipation, dyspnea, fatigue, ataxia, cognitive impairment, muscular weakness, and nausea.

Labeling warns of central nervous system reactions, interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis, hepatotoxicity, myalgia with creatine phosphokinase elevation, hyperuricemia, bone fractures, and embryo-fetal toxicity.

The recommended dose is 160 mg orally once daily for 14 days then increased to 160 mg twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Sixty 40-mg capsules cost around $7,644, according to drugs.com.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The approval is a label expansion for the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), which received initial clearance in November 2023 for locally advanced or metastatic ROS1-positive non–small cell lung cancer.

NTRK gene fusions are genetic abnormalities wherein part of the NTRK gene fuses with an unrelated gene. The abnormal gene can then produce an oncogenic protein. Although rare, these mutations are found in many cancer types.

The approval, for adult and pediatric patients aged 12 years or older, was based on the single-arm open-label TRIDENT-1 trial in 88 adults with locally advanced or metastatic NTRK gene fusion solid tumors.

In the 40 patients who were TKI-naive, the overall response rate was 58%, and the median duration of response was not estimable. In the 48 patients who had a TKI previously, the overall response rate was 50% and median duration of response was 9.9 months.

In 20% or more of participants, treatment caused dizziness, dysgeusia, peripheral neuropathy, constipation, dyspnea, fatigue, ataxia, cognitive impairment, muscular weakness, and nausea.

Labeling warns of central nervous system reactions, interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis, hepatotoxicity, myalgia with creatine phosphokinase elevation, hyperuricemia, bone fractures, and embryo-fetal toxicity.

The recommended dose is 160 mg orally once daily for 14 days then increased to 160 mg twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Sixty 40-mg capsules cost around $7,644, according to drugs.com.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AMA Wrestles With AI But Acts on Prior Authorization, Other Concerns

The largest US physician organization wrestled with the professional risks and rewards of artificial intelligence (AI) at its annual meeting, delaying action even as it adopted new policies on prior authorization and other concerns for clinicians and patients.

Physicians and medical students at the annual meeting of the American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates in Chicago intensely debated a report and two key resolutions on AI but could not reach consensus, pushing off decision-making until a future meeting in November.

One resolution would establish “augmented intelligence” as the preferred term for AI, reflecting the desired role of these tools in supporting — not making — physicians’ decisions. The other resolution focused on insurers’ use of AI in determining medical necessity.

(See specific policies adopted at the meeting, held June 8-12, below.)

A comprehensive AMA trustees’ report on AI considered additional issues including requirements for disclosing AI use, liability for harms due to flawed application of AI, data privacy, and cybersecurity.

The AMA intends to “continue to methodically assess these issues and make informed recommendations in proposing new policy,” said Bobby Mukkamala, MD, an otolaryngologist from Flint, Michigan, who became the AMA’s new president-elect.

AMA members at the meeting largely applauded the aim of these AI proposals, but some objected to parts of the trustees’ report.

They raised questions about what, exactly, constitutes an AI-powered service and whether all AI tools need the kind of guardrails the AMA may seek. There also were concerns about calls to make AI use more transparent.

While transparency might be an admirable goal, it might prove too hard to achieve given that AI-powered tools and products are already woven into medical practice in ways that physicians may not know or understand, said Christopher Libby, MD, MPH, a clinical informaticist and emergency physician at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“It’s hard for the practicing clinician to know how every piece of technology works in order to describe it to the patient,” Dr. Libby said at the meeting. “How many people here can identify when algorithms are used in their EHR today?”

He suggested asking for more transparency from the companies that make and sell AI-powered software and tools to insurers and healthcare systems.

Steven H. Kroft, MD, the editor of the American Journal of Clinical Pathology, raised concerns about the unintended harm that unchecked use of AI may pose to scientific research.

He asked the AMA to address “a significant omission in an otherwise comprehensive report” — the need to protect the integrity of study results that can direct patient care.

“While sham science is not a new issue, large language models make it far easier for authors to generate fake papers and far harder for editors, reviewers, and publishers to identify them,” Dr. Kroft said. “This is a rapidly growing phenomenon that is threatening the integrity of the literature. These papers become embedded in the evidence bases that drive clinical decision-making.”

AMA has been working with specialty societies and outside AI experts to refine an effective set of recommendations. The new policies, once finalized, are intended to build on steps AMA already has taken, including last year releasing principles for AI development, deployment, and use.

Congress Mulling

The AMA delegates are far from alone in facing AI policy challenges.

Leaders in Congress also are examining AI guardrails, with influential panels such as the Senate Finance and House Energy and Commerce committees holding hearings.

A key congressional AI effort to watch is the expected implementation of a bipartisan Senate “road map,” which Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and colleagues released in May, said Miranda A. Franco, a senior policy advisor at the law firm Holland & Knight.

The product of many months of deliberation, this Senate road map identifies priorities for future legislation, including:

- Creating appropriate guardrails and safety measures to protect patients.

- Making healthcare and biomedical data available for machine learning and data science research while carefully addressing privacy issues.

- Providing transparency for clinicians and the public about the use of AI in medical products and clinical support services, including the data used to train models.

- Examining the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ reimbursement mechanisms as well as guardrails to ensure accountability, appropriate use, and broad application of AI across all populations.

Congress likely will address issues of AI in healthcare in piecemeal fashion, taking on different aspects of these challenges at different times, Ms. Franco said. The Senate road map gives the key committees directions on where to proceed in their efforts to develop new laws.

“I think this is all going to be slow and rolling, not big and sweeping,” Ms. Franco told this news organization. “I don’t think we’re going to see an encompassing AI bill.”

AMA Policies Adopted on Other Issues

At the June meeting, AMA delegates adopted the following policies aiming to:

- Increase oversight and accountability of health insurers’ use of prior authorization controls on patient access to care.

- Encourage policy changes allowing physicians to receive loan forgiveness when they practice in an Indian Health Service, Tribal, or Urban Indian Health Program, similar to physicians practicing in a Veterans Administration facility.

- Advocate for federal policy that limits a patient’s out-of-pocket cost to be the same or less than the amount that a patient with traditional Medicare plus a Medigap plan would pay.

- Oppose state or national legislation that could criminalize in vitro fertilization.

- Limit what the AMA calls the “expensive” cost for Medicare Advantage enrollees who need physician-administered drugs or biologics.

- Help physicians address the handling of de-identified patient data in a rapidly changing digital health ecosystem.

- Support efforts to decriminalize the possession of non-prescribed buprenorphine for personal use by individuals who lack access to a physician for the treatment of opioid use disorder.

- Expand access to hearing, vision, and dental care. The new AMA policy advocates working with state medical associations to support coverage of hearing exams, hearing aids, cochlear implants, and vision exams and aids. The revised AMA policy also supports working with the American Dental Association and other national organizations to improve access to dental care for people enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP programs.

- Increase enrollment of more women and sexual and gender minority populations in clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The largest US physician organization wrestled with the professional risks and rewards of artificial intelligence (AI) at its annual meeting, delaying action even as it adopted new policies on prior authorization and other concerns for clinicians and patients.

Physicians and medical students at the annual meeting of the American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates in Chicago intensely debated a report and two key resolutions on AI but could not reach consensus, pushing off decision-making until a future meeting in November.

One resolution would establish “augmented intelligence” as the preferred term for AI, reflecting the desired role of these tools in supporting — not making — physicians’ decisions. The other resolution focused on insurers’ use of AI in determining medical necessity.

(See specific policies adopted at the meeting, held June 8-12, below.)

A comprehensive AMA trustees’ report on AI considered additional issues including requirements for disclosing AI use, liability for harms due to flawed application of AI, data privacy, and cybersecurity.

The AMA intends to “continue to methodically assess these issues and make informed recommendations in proposing new policy,” said Bobby Mukkamala, MD, an otolaryngologist from Flint, Michigan, who became the AMA’s new president-elect.

AMA members at the meeting largely applauded the aim of these AI proposals, but some objected to parts of the trustees’ report.

They raised questions about what, exactly, constitutes an AI-powered service and whether all AI tools need the kind of guardrails the AMA may seek. There also were concerns about calls to make AI use more transparent.

While transparency might be an admirable goal, it might prove too hard to achieve given that AI-powered tools and products are already woven into medical practice in ways that physicians may not know or understand, said Christopher Libby, MD, MPH, a clinical informaticist and emergency physician at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“It’s hard for the practicing clinician to know how every piece of technology works in order to describe it to the patient,” Dr. Libby said at the meeting. “How many people here can identify when algorithms are used in their EHR today?”

He suggested asking for more transparency from the companies that make and sell AI-powered software and tools to insurers and healthcare systems.

Steven H. Kroft, MD, the editor of the American Journal of Clinical Pathology, raised concerns about the unintended harm that unchecked use of AI may pose to scientific research.

He asked the AMA to address “a significant omission in an otherwise comprehensive report” — the need to protect the integrity of study results that can direct patient care.

“While sham science is not a new issue, large language models make it far easier for authors to generate fake papers and far harder for editors, reviewers, and publishers to identify them,” Dr. Kroft said. “This is a rapidly growing phenomenon that is threatening the integrity of the literature. These papers become embedded in the evidence bases that drive clinical decision-making.”

AMA has been working with specialty societies and outside AI experts to refine an effective set of recommendations. The new policies, once finalized, are intended to build on steps AMA already has taken, including last year releasing principles for AI development, deployment, and use.

Congress Mulling

The AMA delegates are far from alone in facing AI policy challenges.

Leaders in Congress also are examining AI guardrails, with influential panels such as the Senate Finance and House Energy and Commerce committees holding hearings.

A key congressional AI effort to watch is the expected implementation of a bipartisan Senate “road map,” which Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and colleagues released in May, said Miranda A. Franco, a senior policy advisor at the law firm Holland & Knight.

The product of many months of deliberation, this Senate road map identifies priorities for future legislation, including:

- Creating appropriate guardrails and safety measures to protect patients.

- Making healthcare and biomedical data available for machine learning and data science research while carefully addressing privacy issues.

- Providing transparency for clinicians and the public about the use of AI in medical products and clinical support services, including the data used to train models.

- Examining the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ reimbursement mechanisms as well as guardrails to ensure accountability, appropriate use, and broad application of AI across all populations.

Congress likely will address issues of AI in healthcare in piecemeal fashion, taking on different aspects of these challenges at different times, Ms. Franco said. The Senate road map gives the key committees directions on where to proceed in their efforts to develop new laws.

“I think this is all going to be slow and rolling, not big and sweeping,” Ms. Franco told this news organization. “I don’t think we’re going to see an encompassing AI bill.”

AMA Policies Adopted on Other Issues

At the June meeting, AMA delegates adopted the following policies aiming to:

- Increase oversight and accountability of health insurers’ use of prior authorization controls on patient access to care.

- Encourage policy changes allowing physicians to receive loan forgiveness when they practice in an Indian Health Service, Tribal, or Urban Indian Health Program, similar to physicians practicing in a Veterans Administration facility.

- Advocate for federal policy that limits a patient’s out-of-pocket cost to be the same or less than the amount that a patient with traditional Medicare plus a Medigap plan would pay.

- Oppose state or national legislation that could criminalize in vitro fertilization.

- Limit what the AMA calls the “expensive” cost for Medicare Advantage enrollees who need physician-administered drugs or biologics.

- Help physicians address the handling of de-identified patient data in a rapidly changing digital health ecosystem.

- Support efforts to decriminalize the possession of non-prescribed buprenorphine for personal use by individuals who lack access to a physician for the treatment of opioid use disorder.

- Expand access to hearing, vision, and dental care. The new AMA policy advocates working with state medical associations to support coverage of hearing exams, hearing aids, cochlear implants, and vision exams and aids. The revised AMA policy also supports working with the American Dental Association and other national organizations to improve access to dental care for people enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP programs.

- Increase enrollment of more women and sexual and gender minority populations in clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The largest US physician organization wrestled with the professional risks and rewards of artificial intelligence (AI) at its annual meeting, delaying action even as it adopted new policies on prior authorization and other concerns for clinicians and patients.

Physicians and medical students at the annual meeting of the American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates in Chicago intensely debated a report and two key resolutions on AI but could not reach consensus, pushing off decision-making until a future meeting in November.

One resolution would establish “augmented intelligence” as the preferred term for AI, reflecting the desired role of these tools in supporting — not making — physicians’ decisions. The other resolution focused on insurers’ use of AI in determining medical necessity.

(See specific policies adopted at the meeting, held June 8-12, below.)

A comprehensive AMA trustees’ report on AI considered additional issues including requirements for disclosing AI use, liability for harms due to flawed application of AI, data privacy, and cybersecurity.

The AMA intends to “continue to methodically assess these issues and make informed recommendations in proposing new policy,” said Bobby Mukkamala, MD, an otolaryngologist from Flint, Michigan, who became the AMA’s new president-elect.

AMA members at the meeting largely applauded the aim of these AI proposals, but some objected to parts of the trustees’ report.

They raised questions about what, exactly, constitutes an AI-powered service and whether all AI tools need the kind of guardrails the AMA may seek. There also were concerns about calls to make AI use more transparent.

While transparency might be an admirable goal, it might prove too hard to achieve given that AI-powered tools and products are already woven into medical practice in ways that physicians may not know or understand, said Christopher Libby, MD, MPH, a clinical informaticist and emergency physician at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

“It’s hard for the practicing clinician to know how every piece of technology works in order to describe it to the patient,” Dr. Libby said at the meeting. “How many people here can identify when algorithms are used in their EHR today?”

He suggested asking for more transparency from the companies that make and sell AI-powered software and tools to insurers and healthcare systems.

Steven H. Kroft, MD, the editor of the American Journal of Clinical Pathology, raised concerns about the unintended harm that unchecked use of AI may pose to scientific research.

He asked the AMA to address “a significant omission in an otherwise comprehensive report” — the need to protect the integrity of study results that can direct patient care.

“While sham science is not a new issue, large language models make it far easier for authors to generate fake papers and far harder for editors, reviewers, and publishers to identify them,” Dr. Kroft said. “This is a rapidly growing phenomenon that is threatening the integrity of the literature. These papers become embedded in the evidence bases that drive clinical decision-making.”

AMA has been working with specialty societies and outside AI experts to refine an effective set of recommendations. The new policies, once finalized, are intended to build on steps AMA already has taken, including last year releasing principles for AI development, deployment, and use.

Congress Mulling

The AMA delegates are far from alone in facing AI policy challenges.

Leaders in Congress also are examining AI guardrails, with influential panels such as the Senate Finance and House Energy and Commerce committees holding hearings.

A key congressional AI effort to watch is the expected implementation of a bipartisan Senate “road map,” which Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and colleagues released in May, said Miranda A. Franco, a senior policy advisor at the law firm Holland & Knight.

The product of many months of deliberation, this Senate road map identifies priorities for future legislation, including:

- Creating appropriate guardrails and safety measures to protect patients.

- Making healthcare and biomedical data available for machine learning and data science research while carefully addressing privacy issues.

- Providing transparency for clinicians and the public about the use of AI in medical products and clinical support services, including the data used to train models.

- Examining the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ reimbursement mechanisms as well as guardrails to ensure accountability, appropriate use, and broad application of AI across all populations.

Congress likely will address issues of AI in healthcare in piecemeal fashion, taking on different aspects of these challenges at different times, Ms. Franco said. The Senate road map gives the key committees directions on where to proceed in their efforts to develop new laws.

“I think this is all going to be slow and rolling, not big and sweeping,” Ms. Franco told this news organization. “I don’t think we’re going to see an encompassing AI bill.”

AMA Policies Adopted on Other Issues

At the June meeting, AMA delegates adopted the following policies aiming to:

- Increase oversight and accountability of health insurers’ use of prior authorization controls on patient access to care.

- Encourage policy changes allowing physicians to receive loan forgiveness when they practice in an Indian Health Service, Tribal, or Urban Indian Health Program, similar to physicians practicing in a Veterans Administration facility.

- Advocate for federal policy that limits a patient’s out-of-pocket cost to be the same or less than the amount that a patient with traditional Medicare plus a Medigap plan would pay.

- Oppose state or national legislation that could criminalize in vitro fertilization.

- Limit what the AMA calls the “expensive” cost for Medicare Advantage enrollees who need physician-administered drugs or biologics.

- Help physicians address the handling of de-identified patient data in a rapidly changing digital health ecosystem.

- Support efforts to decriminalize the possession of non-prescribed buprenorphine for personal use by individuals who lack access to a physician for the treatment of opioid use disorder.

- Expand access to hearing, vision, and dental care. The new AMA policy advocates working with state medical associations to support coverage of hearing exams, hearing aids, cochlear implants, and vision exams and aids. The revised AMA policy also supports working with the American Dental Association and other national organizations to improve access to dental care for people enrolled in Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP programs.

- Increase enrollment of more women and sexual and gender minority populations in clinical trials.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Recurrent UTI Rates High Among Older Women, Diagnosing Accurately Is Complicated

TOPLINE:

Accurately diagnosing recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs) in older women is challenging and requires careful weighing of the risks and benefits of various treatments, according to a new clinical insight published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Women aged > 65 years have double the rUTI rates compared with younger women, but detecting the condition is more complicated due to age-related conditions, such as overactive bladder related to menopause.

- Overuse of antibiotics can increase their risk of contracting antibiotic-resistant organisms and can lead to pulmonary or hepatic toxic effects in women with reduced kidney function.

- Up to 20% of older women have bacteria in their urine, which may or may not reflect a rUTI.

- Diagnosing rUTIs is complicated if women have dementia or cognitive decline, which can hinder recollection of symptoms.

TAKEAWAYS:

- Clinicians should consider only testing older female patients for rUTIs when symptoms are present and consider all possibilities before making a diagnosis.

- Vaginal estrogen may be an effective treatment, although the authors of the clinical review note a lack of a uniform formulation to recommend. However, oral estrogen use is not supported by evidence, and clinicians should instead consider vaginal creams or rings.

- The drug methenamine may be as effective as antibiotics but may not be safe for women with comorbidities. Evidence supports daily use at 1 g.

- Cranberry supplements and behavioral changes may be helpful, but evidence is limited, including among women living in long-term care facilities.

IN PRACTICE:

“Shared decision-making is especially important when diagnosis of an rUTI episode in older women is unclear ... in these cases, clinicians should acknowledge limitations in the evidence and invite patients or their caregivers to discuss preferences about presumptive treatment, weighing the possibility of earlier symptom relief or decreased UTI complications against the risk of adverse drug effects or multidrug resistance.”

SOURCE:

The paper was led by Alison J. Huang, MD, MAS, an internal medicine specialist and researcher in the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors reported no limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Huang received grants from the National Institutes of Health. Other authors reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the Kahn Foundation, and Nanovibronix.

Cranberry supplements and behavioral changes may be helpful, but evidence is limited, including among women living in long-term care facilities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Accurately diagnosing recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs) in older women is challenging and requires careful weighing of the risks and benefits of various treatments, according to a new clinical insight published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Women aged > 65 years have double the rUTI rates compared with younger women, but detecting the condition is more complicated due to age-related conditions, such as overactive bladder related to menopause.

- Overuse of antibiotics can increase their risk of contracting antibiotic-resistant organisms and can lead to pulmonary or hepatic toxic effects in women with reduced kidney function.

- Up to 20% of older women have bacteria in their urine, which may or may not reflect a rUTI.

- Diagnosing rUTIs is complicated if women have dementia or cognitive decline, which can hinder recollection of symptoms.

TAKEAWAYS:

- Clinicians should consider only testing older female patients for rUTIs when symptoms are present and consider all possibilities before making a diagnosis.

- Vaginal estrogen may be an effective treatment, although the authors of the clinical review note a lack of a uniform formulation to recommend. However, oral estrogen use is not supported by evidence, and clinicians should instead consider vaginal creams or rings.

- The drug methenamine may be as effective as antibiotics but may not be safe for women with comorbidities. Evidence supports daily use at 1 g.

- Cranberry supplements and behavioral changes may be helpful, but evidence is limited, including among women living in long-term care facilities.

IN PRACTICE:

“Shared decision-making is especially important when diagnosis of an rUTI episode in older women is unclear ... in these cases, clinicians should acknowledge limitations in the evidence and invite patients or their caregivers to discuss preferences about presumptive treatment, weighing the possibility of earlier symptom relief or decreased UTI complications against the risk of adverse drug effects or multidrug resistance.”

SOURCE:

The paper was led by Alison J. Huang, MD, MAS, an internal medicine specialist and researcher in the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors reported no limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Huang received grants from the National Institutes of Health. Other authors reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the Kahn Foundation, and Nanovibronix.

Cranberry supplements and behavioral changes may be helpful, but evidence is limited, including among women living in long-term care facilities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Accurately diagnosing recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs) in older women is challenging and requires careful weighing of the risks and benefits of various treatments, according to a new clinical insight published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Women aged > 65 years have double the rUTI rates compared with younger women, but detecting the condition is more complicated due to age-related conditions, such as overactive bladder related to menopause.

- Overuse of antibiotics can increase their risk of contracting antibiotic-resistant organisms and can lead to pulmonary or hepatic toxic effects in women with reduced kidney function.

- Up to 20% of older women have bacteria in their urine, which may or may not reflect a rUTI.

- Diagnosing rUTIs is complicated if women have dementia or cognitive decline, which can hinder recollection of symptoms.

TAKEAWAYS:

- Clinicians should consider only testing older female patients for rUTIs when symptoms are present and consider all possibilities before making a diagnosis.

- Vaginal estrogen may be an effective treatment, although the authors of the clinical review note a lack of a uniform formulation to recommend. However, oral estrogen use is not supported by evidence, and clinicians should instead consider vaginal creams or rings.

- The drug methenamine may be as effective as antibiotics but may not be safe for women with comorbidities. Evidence supports daily use at 1 g.

- Cranberry supplements and behavioral changes may be helpful, but evidence is limited, including among women living in long-term care facilities.

IN PRACTICE:

“Shared decision-making is especially important when diagnosis of an rUTI episode in older women is unclear ... in these cases, clinicians should acknowledge limitations in the evidence and invite patients or their caregivers to discuss preferences about presumptive treatment, weighing the possibility of earlier symptom relief or decreased UTI complications against the risk of adverse drug effects or multidrug resistance.”

SOURCE:

The paper was led by Alison J. Huang, MD, MAS, an internal medicine specialist and researcher in the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors reported no limitations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Huang received grants from the National Institutes of Health. Other authors reported receiving grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the Kahn Foundation, and Nanovibronix.

Cranberry supplements and behavioral changes may be helpful, but evidence is limited, including among women living in long-term care facilities.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

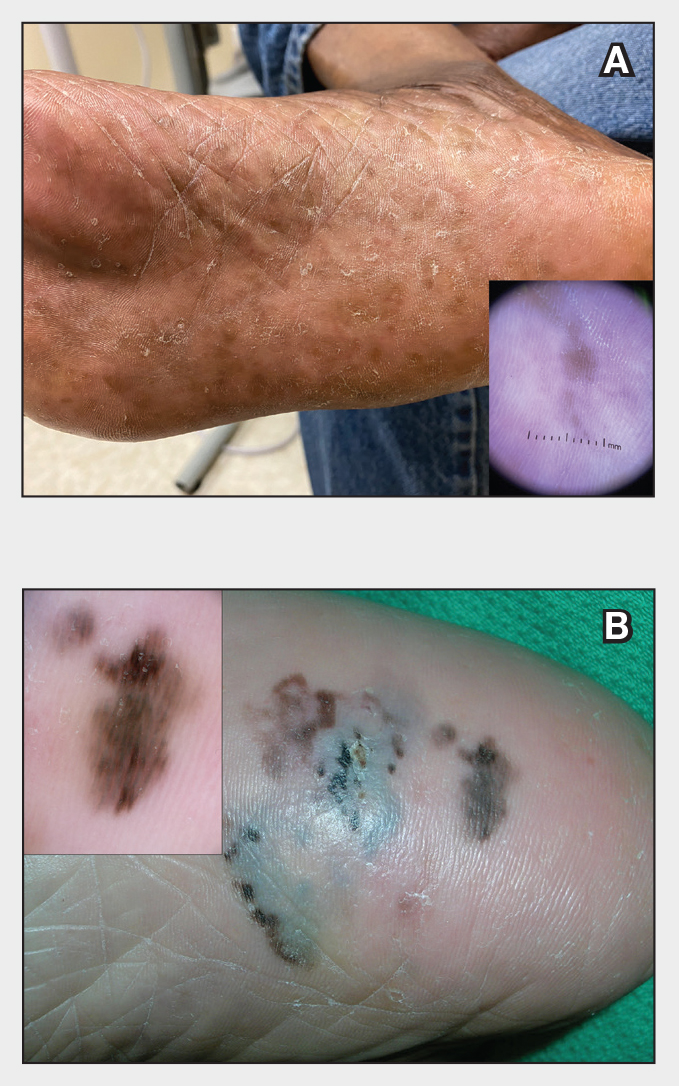

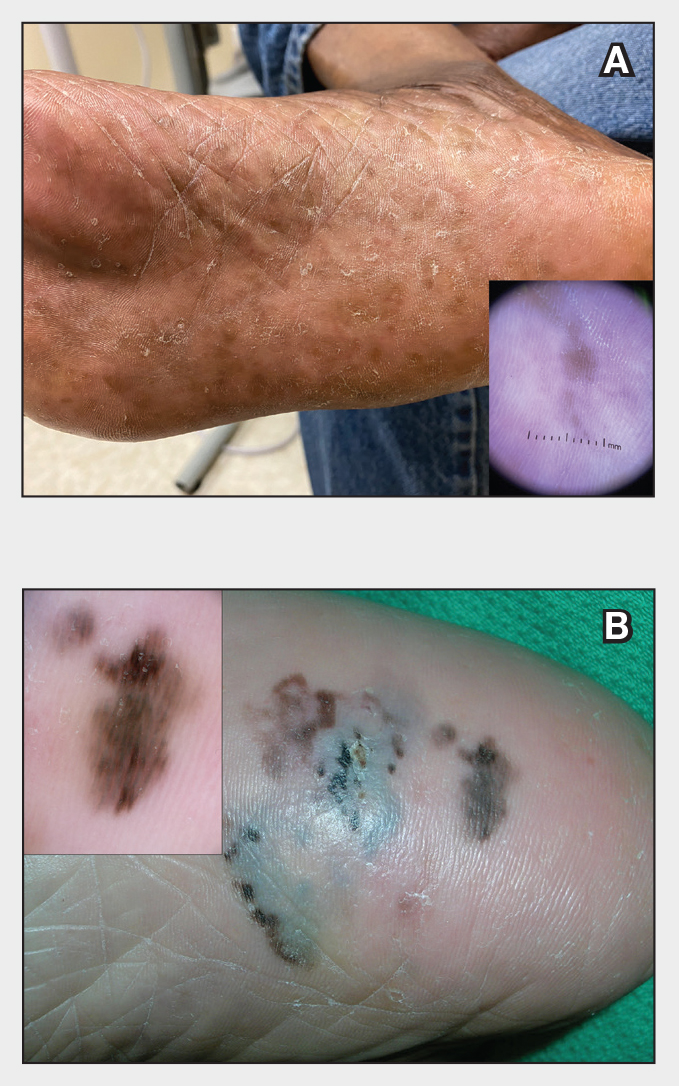

Plantar Hyperpigmentation

The Comparison

Plantar hyperpigmentation (also known as plantar melanosis [increased melanin], volar pigmented macules, benign racial melanosis, acral pigmentation, acral ethnic melanosis, or mottled hyperpigmentation of the plantar surface) is a benign finding in many individuals and is especially prevalent in those with darker skin tones. Acral refers to manifestation on the hands and feet, volar on the palms and soles, and plantar on the soles only. Here, we focus on plantar hyperpigmentation. We use the terms ethnic and racial interchangeably.

It is critically important to differentiate benign hyperpigmentation, which is common in patients with skin of color, from melanoma. Although rare, Black patients in the United States experience high morbidity and mortality from acral melanoma, which often is diagnosed late in the disease course.1

There are many causes of hyperpigmentation on the plantar surfaces, including benign ethnic melanosis, nevi, melanoma, infections such as syphilis and tinea nigra, conditions such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation secondary to atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. We focus on the most common causes, ethnic melanosis and nevi, as well as melanoma, which is the deadliest cause.

Epidemiology

In a 1980 study (N=251), Black Americans had a high incidence of plantar hyperpigmentation, with 52% of affected patients having dark brown skin and 31% having light brown skin.2

The epidemiology of melanoma varies by race/ethnicity. Melanoma in Black individuals is relatively rare, with an annual incidence of approximately 1 in 100,000 individuals.3 However, when individuals with skin of color develop melanoma, they are more likely than their White counterparts to have acral melanoma (acral lentiginous melanoma), one of the deadliest types.1 In a case series of Black patients with melanoma (N=48) from 2 tertiary care centers in Texas, 30 of 40 primary cutaneous melanomas (75%) were located on acral skin.4 Overall, 13 patients developed stage IV disease and 12 died due to disease progression. All patients who developed distant metastases or died of melanoma had acral melanoma.4 Individuals of Asian descent also have a high incidence of acral melanoma, as shown in research from Japan.5-9

Key clinical features in individuals with darker skin tones

Dermoscopy is an evidence-based clinical examination method for earlier diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma, including on acral skin.10,11 Benign nevi on the volar skin as well as the palms and soles tend to have one of these 3 dermoscopic patterns: parallel furrow, lattice, or irregular fibrillar. The pattern that is most predictive of volar melanoma is the parallel ridge pattern (PRP) (Figures A and B [insets]), which showed a high specificity (99.0%) and very high negative predictive value (97.7%) for malignant melanoma in a Japanese population.7 The PRP data from this study cannot be applied reliably to Black individuals, especially because benign ethnic melanosis and other benign conditions can demonstrate PRP.12 Reliance on the PRP as a diagnostic clue could result in unneccessary biopsies in as many as 50% of Black patients with benign plantar hyperpigmentation.2 Furthermore, biopsies of the plantar surface can be painful and cause pain while walking.

It has been suggested that PRP seen on dermoscopy in benign hyperpigmentation such as ethnic melanosis and nevi may preserve the acrosyringia (eccrine gland openings on the ridge), whereas PRP in melanoma may obliterate the acrosyringia.13 This observation is based on case reports only and needs further study. However, if validated, it could be a useful diagnostic clue.

Worth noting

In a retrospective cohort study of skin cancer in Black individuals (n=165) at a New York City–based cancer center from 2000 to 2020, 68% of patients were diagnosed with melanomas—80% were the acral subtype and 75% displayed a PRP. However, the surrounding uninvolved background skin, which was visible in most cases, also demonstrated a PRP.14 Because of the high morbidity and mortality rates of acral melanoma, clinicians should biopsy or immediately refer patients with concerning plantar hyperpigmentation to a dermatologist.

Health disparity highlight

The mortality rate for acral melanoma in Black patients is disproportionately high for the following reasons15,16:

- Patients and health care providers do not expect to see melanoma in Black patients (it truly is rare!), so screening and education on sun protection are limited.

- Benign ethnic melanosis makes it more difficult to distinguish between early acral melanoma and benign skin changes.

- Black patients and other US patient populations with skin of color may be less likely to have health insurance, which contributes to inequities in access to health care. As of 2022, the uninsured rates for nonelderly American Indian and Alaska Native, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, Black, and White individuals were 19.1%, 18.0%, 12.7%, 10.0%, and 6.6%, respectively.17

Multi-institutional registries could improve understanding of acral melanoma in Black patients.4 More studies are needed to help differentiate between the dermoscopic finding of PRP in benign ethnic melanosis vs malignant melanoma.

- Huang K, Fan J, Misra S. Acral lentiginous melanoma: incidence and survival in the United States, 2006-2015: an analysis of the SEER registry. J Surg Res. 2020;251:329-339. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2020.02.010

- Coleman WP, Gately LE, Krementz AB, et al. Nevi, lentigines, and melanomas in blacks. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:548-551.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Melanoma Incidence and Mortality, United States: 2012-2016. USCS Data Brief, no. 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no9-melanoma-incidence-mortality-UnitedStates-2012-2016.htm

- Wix SN, Brown AB, Heberton M, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of black patients with melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:328-333. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5789

- Saida T, Koga H. Dermoscopic patterns of acral melanocytic nevi: their variations, changes, and significance. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1423-1426. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.11.1423

- Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Key points in dermoscopic differentiation between early acral melanoma and acral nevus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:25-34. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01174.x

- Saida T, Miyazaki A, Oguchi S. Significance of dermoscopic patterns in detecting malignant melanoma on acral volar skin: results of a multicenter study in Japan. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1233-1238. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.10.1233

- Saida T, Koga H, Uhara H. Dermoscopy for acral melanocytic lesions: revision of the 3-step algorithm and refined definition of the regular and irregular fibrillar pattern. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12:e2022123. doi:10.5826/dpc.1203a123

- Heath CR, Usatine RP. Melanoma. Cutis. 2022;109:284-285.doi:10.12788/cutis.0513.

- Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al; Cochrane Skin Cancer Diagnostic Test Accuracy Group. Visual inspection and dermoscopy, alone or in combination, for diagnosing keratinocyte skin cancers in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 12:CD011901. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011901.pub2

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked-eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08713.x

- Phan A, Dalle S, Marcilly MC, et al. Benign dermoscopic parallel ridge pattern variants. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:634. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.47

- Fracaroli TS, Lavorato FG, Maceira JP, et al. Parallel ridge pattern on dermoscopy: observation in non-melanoma cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:646-648. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132058

- Manci RN, Dauscher M, Marchetti MA, et al. Features of skin cancer in black individuals: a single-institution retrospective cohort study. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12:e2022075. doi:10.5826/dpc.1202a75

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.006

- Ingrassia JP, Stein JA, Levine A, et al. Diagnosis and management of acral pigmented lesions. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 2023;49:926-931. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003891

- Hill L, Artiga S, Damico A. Health coverage by race and ethnicity, 2010-2022. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published January 11, 2024. Accessed May 9, 2024. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity

The Comparison

Plantar hyperpigmentation (also known as plantar melanosis [increased melanin], volar pigmented macules, benign racial melanosis, acral pigmentation, acral ethnic melanosis, or mottled hyperpigmentation of the plantar surface) is a benign finding in many individuals and is especially prevalent in those with darker skin tones. Acral refers to manifestation on the hands and feet, volar on the palms and soles, and plantar on the soles only. Here, we focus on plantar hyperpigmentation. We use the terms ethnic and racial interchangeably.

It is critically important to differentiate benign hyperpigmentation, which is common in patients with skin of color, from melanoma. Although rare, Black patients in the United States experience high morbidity and mortality from acral melanoma, which often is diagnosed late in the disease course.1

There are many causes of hyperpigmentation on the plantar surfaces, including benign ethnic melanosis, nevi, melanoma, infections such as syphilis and tinea nigra, conditions such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and Laugier-Hunziker syndrome, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation secondary to atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. We focus on the most common causes, ethnic melanosis and nevi, as well as melanoma, which is the deadliest cause.

Epidemiology

In a 1980 study (N=251), Black Americans had a high incidence of plantar hyperpigmentation, with 52% of affected patients having dark brown skin and 31% having light brown skin.2