User login

Atopic dermatitis, sleep difficulties often intertwined

According to Phyllis C. Zee, MD, PhD, proinflammatory cytokines influence neural processes that affect sleep and circadian rhythm. “It’s almost like when you’re most vulnerable, when you’re sleeping, the immune system is kind of poised for attack,” Dr. Zee, chief of the division of sleep medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “This is normal, and perhaps in some of these inflammatory disorders, it’s gone a little haywire.”

Circulation of interleukins and cytokines are high in the morning, become lower in the afternoon, and then get higher again in the evening hours and into the night during sleep, she continued. “Whereas if you look at something like blood flow, it increases on a diurnal basis,” she said. “It’s higher during the day and a little bit lower during the mid-day, and a little bit higher during the evening. That parallels changes in the sebum production of the skin and the transepidermal water loss, which has been implicated in some of the symptoms of AD. What’s curious about this is that the transdermal/epidermal water loss is really highest during the sleep period. Some of this is sleep gated, but some of this is circadian gated as well. There’s a bidirectional relationship between sleep and immunity.”

Disturbance of sleep can have multiple consequences. It can activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis through autonomic activation, increase brain metabolic activity, trigger mood disturbances and cognitive impairment, and cause daytime sleepiness and health consequences that affect cardiometabolic and immunologic health.

One study conducted by Anna B. Fishbein, MD, Dr. Zee, and colleagues at Northwestern examined the effects of sleep duration and sleep disruption and movements in 38 children with and without moderate to severe AD. It found that children with AD get about 1 hour less of sleep per night overall, compared with age-matched healthy controls. “It’s not so much difficulty falling asleep, but more difficulty staying asleep as determined by wake after sleep onset,” said Dr. Zee, who is also a professor of neurology at Northwestern.

A study of 34,613 adults who participated in the 2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that eczema increased the odds of fatigue (odds ratio, 2.97), daytime sleepiness (OR, 2.66), and regular insomnia (OR, 2.36).

“Very importantly, it predicted poor health,” said Dr. Zee, who was one of the study’s coauthors. “This gives us an opportunity to think about how we can improve sleep to improve outcomes.”

Dr. Zee advises dermatologists and primary care clinicians to ask patients with AD about their sleep health by using a screening tool such as the self-reported STOP questionnaire, which consists of the following questions: “Do you snore loudly?” “Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during daytime?” “Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?” “Do you have or are you being treated for high blood pressure?”

Other clinical indicators of a sleep disorder, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), include having a neck circumference of 17 inches or greater in men and 16 inches or greater in women. “You want to also do a brief upper-airway examination, the Mallampati classification where you say to the patient, ‘open your mouth, don’t stick your mouth out too much,’ and you look at how crowded the upper airway is,” Dr. Zee said . “Someone with a Mallampati score of 3 has a very high risk of having sleep apnea.”

She also recommends asking patients with AD if they have difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep 3 or more nights per week, and about the frequency and duration of awakenings. “Maybe they have insomnia as a disorder,” she said. “If they have trouble falling asleep, maybe they have a circadian rhythm disorder. You want to ask about snoring, choking, and stop breathing episodes, because those are symptoms of sleep apnea. You want to ask about itch, uncomfortable sensations in the limbs during sleep or while trying to get to sleep, because that may be something like restless legs syndrome. Sleep disorder assessment is important because it impair daytime function, cognition, attention, and disruptive behavior, especially in children.”

For the management of insomnia, try behavioral approaches first. “You don’t want to try medications from the get-go,” Dr. Zee advised. Techniques include sleep hygiene and stimulus control therapy, “to make the bedroom a safe place to sleep. Lower the temperature a little bit and get rid of the allergens as much as possible. Relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy can also help. If you get a lot of light during the day, structure your physical activity, and watch what and when you eat.”

An OSA diagnosis requires evaluation of objective information from a sleep study. Common treatments of mild to moderate OSA include nasal continuous positive airway pressure and oral appliances.

Dr. Zee disclosed that she had received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Harmony and Apnimed. She also serves on the scientific advisory board of Eisai, Jazz, CVS-Caremark, Takeda, and Sanofi-Aventis, and holds stock in Teva.

According to Phyllis C. Zee, MD, PhD, proinflammatory cytokines influence neural processes that affect sleep and circadian rhythm. “It’s almost like when you’re most vulnerable, when you’re sleeping, the immune system is kind of poised for attack,” Dr. Zee, chief of the division of sleep medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “This is normal, and perhaps in some of these inflammatory disorders, it’s gone a little haywire.”

Circulation of interleukins and cytokines are high in the morning, become lower in the afternoon, and then get higher again in the evening hours and into the night during sleep, she continued. “Whereas if you look at something like blood flow, it increases on a diurnal basis,” she said. “It’s higher during the day and a little bit lower during the mid-day, and a little bit higher during the evening. That parallels changes in the sebum production of the skin and the transepidermal water loss, which has been implicated in some of the symptoms of AD. What’s curious about this is that the transdermal/epidermal water loss is really highest during the sleep period. Some of this is sleep gated, but some of this is circadian gated as well. There’s a bidirectional relationship between sleep and immunity.”

Disturbance of sleep can have multiple consequences. It can activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis through autonomic activation, increase brain metabolic activity, trigger mood disturbances and cognitive impairment, and cause daytime sleepiness and health consequences that affect cardiometabolic and immunologic health.

One study conducted by Anna B. Fishbein, MD, Dr. Zee, and colleagues at Northwestern examined the effects of sleep duration and sleep disruption and movements in 38 children with and without moderate to severe AD. It found that children with AD get about 1 hour less of sleep per night overall, compared with age-matched healthy controls. “It’s not so much difficulty falling asleep, but more difficulty staying asleep as determined by wake after sleep onset,” said Dr. Zee, who is also a professor of neurology at Northwestern.

A study of 34,613 adults who participated in the 2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that eczema increased the odds of fatigue (odds ratio, 2.97), daytime sleepiness (OR, 2.66), and regular insomnia (OR, 2.36).

“Very importantly, it predicted poor health,” said Dr. Zee, who was one of the study’s coauthors. “This gives us an opportunity to think about how we can improve sleep to improve outcomes.”

Dr. Zee advises dermatologists and primary care clinicians to ask patients with AD about their sleep health by using a screening tool such as the self-reported STOP questionnaire, which consists of the following questions: “Do you snore loudly?” “Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during daytime?” “Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?” “Do you have or are you being treated for high blood pressure?”

Other clinical indicators of a sleep disorder, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), include having a neck circumference of 17 inches or greater in men and 16 inches or greater in women. “You want to also do a brief upper-airway examination, the Mallampati classification where you say to the patient, ‘open your mouth, don’t stick your mouth out too much,’ and you look at how crowded the upper airway is,” Dr. Zee said . “Someone with a Mallampati score of 3 has a very high risk of having sleep apnea.”

She also recommends asking patients with AD if they have difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep 3 or more nights per week, and about the frequency and duration of awakenings. “Maybe they have insomnia as a disorder,” she said. “If they have trouble falling asleep, maybe they have a circadian rhythm disorder. You want to ask about snoring, choking, and stop breathing episodes, because those are symptoms of sleep apnea. You want to ask about itch, uncomfortable sensations in the limbs during sleep or while trying to get to sleep, because that may be something like restless legs syndrome. Sleep disorder assessment is important because it impair daytime function, cognition, attention, and disruptive behavior, especially in children.”

For the management of insomnia, try behavioral approaches first. “You don’t want to try medications from the get-go,” Dr. Zee advised. Techniques include sleep hygiene and stimulus control therapy, “to make the bedroom a safe place to sleep. Lower the temperature a little bit and get rid of the allergens as much as possible. Relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy can also help. If you get a lot of light during the day, structure your physical activity, and watch what and when you eat.”

An OSA diagnosis requires evaluation of objective information from a sleep study. Common treatments of mild to moderate OSA include nasal continuous positive airway pressure and oral appliances.

Dr. Zee disclosed that she had received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Harmony and Apnimed. She also serves on the scientific advisory board of Eisai, Jazz, CVS-Caremark, Takeda, and Sanofi-Aventis, and holds stock in Teva.

According to Phyllis C. Zee, MD, PhD, proinflammatory cytokines influence neural processes that affect sleep and circadian rhythm. “It’s almost like when you’re most vulnerable, when you’re sleeping, the immune system is kind of poised for attack,” Dr. Zee, chief of the division of sleep medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago, said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “This is normal, and perhaps in some of these inflammatory disorders, it’s gone a little haywire.”

Circulation of interleukins and cytokines are high in the morning, become lower in the afternoon, and then get higher again in the evening hours and into the night during sleep, she continued. “Whereas if you look at something like blood flow, it increases on a diurnal basis,” she said. “It’s higher during the day and a little bit lower during the mid-day, and a little bit higher during the evening. That parallels changes in the sebum production of the skin and the transepidermal water loss, which has been implicated in some of the symptoms of AD. What’s curious about this is that the transdermal/epidermal water loss is really highest during the sleep period. Some of this is sleep gated, but some of this is circadian gated as well. There’s a bidirectional relationship between sleep and immunity.”

Disturbance of sleep can have multiple consequences. It can activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis through autonomic activation, increase brain metabolic activity, trigger mood disturbances and cognitive impairment, and cause daytime sleepiness and health consequences that affect cardiometabolic and immunologic health.

One study conducted by Anna B. Fishbein, MD, Dr. Zee, and colleagues at Northwestern examined the effects of sleep duration and sleep disruption and movements in 38 children with and without moderate to severe AD. It found that children with AD get about 1 hour less of sleep per night overall, compared with age-matched healthy controls. “It’s not so much difficulty falling asleep, but more difficulty staying asleep as determined by wake after sleep onset,” said Dr. Zee, who is also a professor of neurology at Northwestern.

A study of 34,613 adults who participated in the 2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that eczema increased the odds of fatigue (odds ratio, 2.97), daytime sleepiness (OR, 2.66), and regular insomnia (OR, 2.36).

“Very importantly, it predicted poor health,” said Dr. Zee, who was one of the study’s coauthors. “This gives us an opportunity to think about how we can improve sleep to improve outcomes.”

Dr. Zee advises dermatologists and primary care clinicians to ask patients with AD about their sleep health by using a screening tool such as the self-reported STOP questionnaire, which consists of the following questions: “Do you snore loudly?” “Do you often feel tired, fatigued, or sleepy during daytime?” “Has anyone observed you stop breathing during your sleep?” “Do you have or are you being treated for high blood pressure?”

Other clinical indicators of a sleep disorder, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), include having a neck circumference of 17 inches or greater in men and 16 inches or greater in women. “You want to also do a brief upper-airway examination, the Mallampati classification where you say to the patient, ‘open your mouth, don’t stick your mouth out too much,’ and you look at how crowded the upper airway is,” Dr. Zee said . “Someone with a Mallampati score of 3 has a very high risk of having sleep apnea.”

She also recommends asking patients with AD if they have difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep 3 or more nights per week, and about the frequency and duration of awakenings. “Maybe they have insomnia as a disorder,” she said. “If they have trouble falling asleep, maybe they have a circadian rhythm disorder. You want to ask about snoring, choking, and stop breathing episodes, because those are symptoms of sleep apnea. You want to ask about itch, uncomfortable sensations in the limbs during sleep or while trying to get to sleep, because that may be something like restless legs syndrome. Sleep disorder assessment is important because it impair daytime function, cognition, attention, and disruptive behavior, especially in children.”

For the management of insomnia, try behavioral approaches first. “You don’t want to try medications from the get-go,” Dr. Zee advised. Techniques include sleep hygiene and stimulus control therapy, “to make the bedroom a safe place to sleep. Lower the temperature a little bit and get rid of the allergens as much as possible. Relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy can also help. If you get a lot of light during the day, structure your physical activity, and watch what and when you eat.”

An OSA diagnosis requires evaluation of objective information from a sleep study. Common treatments of mild to moderate OSA include nasal continuous positive airway pressure and oral appliances.

Dr. Zee disclosed that she had received research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Harmony and Apnimed. She also serves on the scientific advisory board of Eisai, Jazz, CVS-Caremark, Takeda, and Sanofi-Aventis, and holds stock in Teva.

FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2020

Primary care clinicians neglect hearing loss, survey finds

But asking a single question – “Do you think you have hearing loss?” – may be an efficient way to identify patients who should receive further evaluation, researchers said.

Only 20% of adults aged 50-80 years report that their primary care physician has asked about their hearing in the past 2 years, according to the National Poll on Healthy Aging, published online March 2. Among adults who rated their hearing as fair or poor, only 26% said they had been asked about their hearing.

Michael McKee, MD, MPH, a family medicine physician and health services researcher at Michigan Medicine, the University of Michigan’s academic medical center, and colleagues surveyed 2,074 adults aged 50-80 years in June 2020. They asked participants about the screening and testing of hearing that they had undergone. The researchers weighted the sample to reflect population figures from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Men were more likely than women to have been asked about their hearing (24% vs. 17%), and adults aged 65-80 years were more likely than younger adults to have been asked about their hearing (25% vs. 16%).

The survey also found that 23% of adults had undergone a hearing test by a health care professional; 62% felt that it was at least somewhat important to have their hearing tested at least once every 2 years.

Overall, 16% of adults rated their hearing as fair or poor. Approximately a third rated their hearing as good, and about half rated their hearing as excellent or very good. Fair or poor hearing was more commonly reported by men than women (20% vs. 12%) and by older adults than younger adults (19% vs. 14%).

In all, 6% used a hearing aid or cochlear implant. Of the adults who used these devices, 13% rated their hearing as fair or poor.

Those with worse physical or mental health were more likely to rate their hearing as fair or poor and were less likely to have undergone testing.

Although “screening for hearing loss is expected as part of the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit,” the data suggest that most adults aged 65-80 years have not been screened recently, the researchers say.

“One efficient way to increase hearing evaluations among older adults in primary care is to use a single-question screener,” Dr. McKee and coauthors wrote.

“The response to the question ‘Do you think you have hearing loss?’ has been shown to be highly predictive of true hearing loss ... Age-related hearing loss remains a neglected primary care and public health concern. Consistent use of screening tools and improved access to assistive devices that treat hearing loss can enhance the health and well-being of older adults,” they wrote.

Philip Zazove, MD, chair of the department of family medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and one of the authors of the report, noted in a news release that health insurance coverage varies widely for hearing screening by primary care providers, testing by audiologists, and hearing aids and cochlear implants.

Implementing the single-question screener is “easy to do,” Dr. Zazove said in an interview. “The major barrier is remembering, considering all the things primary care needs to do.” Electronic prompts may be an effective reminder.

If a patient answers yes, then clinicians should discuss referral for testing. Still, some patients may not be ready for further testing or treatment, possibly owing to vanity, misunderstandings, or cultural barriers, Dr. Zazove said. “Unfortunately, most physicians are not comfortable dealing with hearing loss. We get relatively little education on that in medical school and even residency,” he said.

“Hearing screening isn’t difficult,” and primary care providers can accomplish it “with one quick screening question – as the authors note,” said Jan Blustein, MD, PhD, professor of health policy and medicine at New York University. “I believe that some providers may be reluctant to screen or make a referral because they know that many people can’t afford hearing aids ... However, I also believe that many providers just don’t appreciate how disabling hearing loss is. And many didn’t receive training in this area in medical school. Training in disability gets very short shrift at most schools, in my experience. This needs to change.”

The survey does not address whether screening practices for hearing loss has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, though Dr. Zazove suspects that screening has decreased as a result. Even if patients are screened, some may not present for audiology testing “because of fear of COVID or the audiologist not being open,” he said.

Hearing loss is associated with increased risk for hospitalization and readmission, dementia, and depression. “We believe, though studies are needed to verify, that detection and intervention for these patients can ameliorate the adverse health, social, and economic outcomes,” Dr. Zazove said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

But asking a single question – “Do you think you have hearing loss?” – may be an efficient way to identify patients who should receive further evaluation, researchers said.

Only 20% of adults aged 50-80 years report that their primary care physician has asked about their hearing in the past 2 years, according to the National Poll on Healthy Aging, published online March 2. Among adults who rated their hearing as fair or poor, only 26% said they had been asked about their hearing.

Michael McKee, MD, MPH, a family medicine physician and health services researcher at Michigan Medicine, the University of Michigan’s academic medical center, and colleagues surveyed 2,074 adults aged 50-80 years in June 2020. They asked participants about the screening and testing of hearing that they had undergone. The researchers weighted the sample to reflect population figures from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Men were more likely than women to have been asked about their hearing (24% vs. 17%), and adults aged 65-80 years were more likely than younger adults to have been asked about their hearing (25% vs. 16%).

The survey also found that 23% of adults had undergone a hearing test by a health care professional; 62% felt that it was at least somewhat important to have their hearing tested at least once every 2 years.

Overall, 16% of adults rated their hearing as fair or poor. Approximately a third rated their hearing as good, and about half rated their hearing as excellent or very good. Fair or poor hearing was more commonly reported by men than women (20% vs. 12%) and by older adults than younger adults (19% vs. 14%).

In all, 6% used a hearing aid or cochlear implant. Of the adults who used these devices, 13% rated their hearing as fair or poor.

Those with worse physical or mental health were more likely to rate their hearing as fair or poor and were less likely to have undergone testing.

Although “screening for hearing loss is expected as part of the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit,” the data suggest that most adults aged 65-80 years have not been screened recently, the researchers say.

“One efficient way to increase hearing evaluations among older adults in primary care is to use a single-question screener,” Dr. McKee and coauthors wrote.

“The response to the question ‘Do you think you have hearing loss?’ has been shown to be highly predictive of true hearing loss ... Age-related hearing loss remains a neglected primary care and public health concern. Consistent use of screening tools and improved access to assistive devices that treat hearing loss can enhance the health and well-being of older adults,” they wrote.

Philip Zazove, MD, chair of the department of family medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and one of the authors of the report, noted in a news release that health insurance coverage varies widely for hearing screening by primary care providers, testing by audiologists, and hearing aids and cochlear implants.

Implementing the single-question screener is “easy to do,” Dr. Zazove said in an interview. “The major barrier is remembering, considering all the things primary care needs to do.” Electronic prompts may be an effective reminder.

If a patient answers yes, then clinicians should discuss referral for testing. Still, some patients may not be ready for further testing or treatment, possibly owing to vanity, misunderstandings, or cultural barriers, Dr. Zazove said. “Unfortunately, most physicians are not comfortable dealing with hearing loss. We get relatively little education on that in medical school and even residency,” he said.

“Hearing screening isn’t difficult,” and primary care providers can accomplish it “with one quick screening question – as the authors note,” said Jan Blustein, MD, PhD, professor of health policy and medicine at New York University. “I believe that some providers may be reluctant to screen or make a referral because they know that many people can’t afford hearing aids ... However, I also believe that many providers just don’t appreciate how disabling hearing loss is. And many didn’t receive training in this area in medical school. Training in disability gets very short shrift at most schools, in my experience. This needs to change.”

The survey does not address whether screening practices for hearing loss has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, though Dr. Zazove suspects that screening has decreased as a result. Even if patients are screened, some may not present for audiology testing “because of fear of COVID or the audiologist not being open,” he said.

Hearing loss is associated with increased risk for hospitalization and readmission, dementia, and depression. “We believe, though studies are needed to verify, that detection and intervention for these patients can ameliorate the adverse health, social, and economic outcomes,” Dr. Zazove said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

But asking a single question – “Do you think you have hearing loss?” – may be an efficient way to identify patients who should receive further evaluation, researchers said.

Only 20% of adults aged 50-80 years report that their primary care physician has asked about their hearing in the past 2 years, according to the National Poll on Healthy Aging, published online March 2. Among adults who rated their hearing as fair or poor, only 26% said they had been asked about their hearing.

Michael McKee, MD, MPH, a family medicine physician and health services researcher at Michigan Medicine, the University of Michigan’s academic medical center, and colleagues surveyed 2,074 adults aged 50-80 years in June 2020. They asked participants about the screening and testing of hearing that they had undergone. The researchers weighted the sample to reflect population figures from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Men were more likely than women to have been asked about their hearing (24% vs. 17%), and adults aged 65-80 years were more likely than younger adults to have been asked about their hearing (25% vs. 16%).

The survey also found that 23% of adults had undergone a hearing test by a health care professional; 62% felt that it was at least somewhat important to have their hearing tested at least once every 2 years.

Overall, 16% of adults rated their hearing as fair or poor. Approximately a third rated their hearing as good, and about half rated their hearing as excellent or very good. Fair or poor hearing was more commonly reported by men than women (20% vs. 12%) and by older adults than younger adults (19% vs. 14%).

In all, 6% used a hearing aid or cochlear implant. Of the adults who used these devices, 13% rated their hearing as fair or poor.

Those with worse physical or mental health were more likely to rate their hearing as fair or poor and were less likely to have undergone testing.

Although “screening for hearing loss is expected as part of the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit,” the data suggest that most adults aged 65-80 years have not been screened recently, the researchers say.

“One efficient way to increase hearing evaluations among older adults in primary care is to use a single-question screener,” Dr. McKee and coauthors wrote.

“The response to the question ‘Do you think you have hearing loss?’ has been shown to be highly predictive of true hearing loss ... Age-related hearing loss remains a neglected primary care and public health concern. Consistent use of screening tools and improved access to assistive devices that treat hearing loss can enhance the health and well-being of older adults,” they wrote.

Philip Zazove, MD, chair of the department of family medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and one of the authors of the report, noted in a news release that health insurance coverage varies widely for hearing screening by primary care providers, testing by audiologists, and hearing aids and cochlear implants.

Implementing the single-question screener is “easy to do,” Dr. Zazove said in an interview. “The major barrier is remembering, considering all the things primary care needs to do.” Electronic prompts may be an effective reminder.

If a patient answers yes, then clinicians should discuss referral for testing. Still, some patients may not be ready for further testing or treatment, possibly owing to vanity, misunderstandings, or cultural barriers, Dr. Zazove said. “Unfortunately, most physicians are not comfortable dealing with hearing loss. We get relatively little education on that in medical school and even residency,” he said.

“Hearing screening isn’t difficult,” and primary care providers can accomplish it “with one quick screening question – as the authors note,” said Jan Blustein, MD, PhD, professor of health policy and medicine at New York University. “I believe that some providers may be reluctant to screen or make a referral because they know that many people can’t afford hearing aids ... However, I also believe that many providers just don’t appreciate how disabling hearing loss is. And many didn’t receive training in this area in medical school. Training in disability gets very short shrift at most schools, in my experience. This needs to change.”

The survey does not address whether screening practices for hearing loss has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, though Dr. Zazove suspects that screening has decreased as a result. Even if patients are screened, some may not present for audiology testing “because of fear of COVID or the audiologist not being open,” he said.

Hearing loss is associated with increased risk for hospitalization and readmission, dementia, and depression. “We believe, though studies are needed to verify, that detection and intervention for these patients can ameliorate the adverse health, social, and economic outcomes,” Dr. Zazove said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Can smoke exposure inform CRC surveillance in IBD?

Cigarette smoking may be associated with a higher probability of developing colorectal neoplasia (CRN) among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a finding that if confirmed could help to refine colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines. IBD patients undergo surveillance at specific time points of their disease with the aim to detect and potentially treat early CRN.

But these procedures are costly and burdensome to patients, and some previous studies have revealed a relatively low utility for patients, according to Kimberley van der Sloot, MD, a PhD candidate at the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands). She presented the research at the annual congress of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association. The study was also published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“We aimed to explore the role of cigarette exposure in colorectal neoplasia risk in patients with IBD, and we aimed to improve the CRN risk stratification model that we are currently using for these surveillance guidelines,” Dr. van der Sloot said during her talk.

Commenters during the Q&A period noted that the population database used in the study did not include measures of inflammation, which is a known risk for CRN. One review found that smoking worsens inflammation in Crohn’s disease but improves it in ulcerative colitis.

“It certainly raises the issue that we’ve always said, which is that people should quit smoking for other health reasons, but it doesn’t necessarily answer the question definitively,” said David Rubin, MD, who moderated the session and is professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and chair of the congress’s organizing committee. He added that the association between smoking and CRN risk may nevertheless inform future management surveillance guidelines if it is confirmed.

The researchers analyzed data from the 1000IBD cohort, which is prospectively following IBD patients in the Netherlands. The study included 1,386 patients who had at least one colorectal biopsy. Compared to a general population CRN incidence of 2.4%, Crohn’s disease patients who were never smokers had an incidence of 4.7% versus 10.3% among former or current smokers. In ulcerative colitis, the incidence was 12.5% among never smokers and 17.9% among former or current smokers.

In Crohn’s disease, previous or current smokers had about a twofold increased risk (hazard ratio, 2.04; P = .044). Compared to never smokers, former smokers trended toward an increased risk (HR, 2.16; P = .051), and active smokers had a significantly increased risk (HR, 2.20; P = .044). Passive smoke exposure was also associated with greater risk, both in childhood (HR, 4.79; P = .003) and current (HR, 1.87; P = .024).

In ulcerative colitis, the only statistically significant association between smoke exposure and CRN risk was among former smokers (HR, 1.73; P = .032).

The researchers also looked at patients with a disease duration longer than 8 years and stratified patients according to low risk (left-side ulcerative colitis, <50% of colon affected in Crohn’s disease; n = 425), medium risk (postinflammatory polyposis present or extensive colitis; n = 467), and high risk (concordant primary sclerosing cholangitis or having a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer; n = 143). In Crohn’s disease, current smoking was associated with greater CRN incidence (P = .046), and former smoking trended in that direction but was nonsignificant (P = .068). Former smoking also trended toward a risk in ulcerative colitis (P = .068), but there was no sign of an association for current smoking (P = .883).

In Crohn’s disease, after adjustment for risk stratification, greater CRN risk was associated with passive smoke exposure both during childhood (P = .001) and at present (P = .003).

“We believe this is the first study to describe the important role of cigarette smoking in development of colorectal neoplasia in IBD patients in a large, prospective, cohort, and I think [it] has shown the importance of lifestyle and smoking particularly in IBD. This is one more example. Alongside that, we’ve shown that adding this risk factor can improve the current risk stratification that is used for surveillance guidelines, and might be of benefit in the development of future guidelines,” said Dr. van der Sloot.

Dr. van der Sloot and Dr. Rubin had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated Mar. 11, 2021.

Cigarette smoking may be associated with a higher probability of developing colorectal neoplasia (CRN) among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a finding that if confirmed could help to refine colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines. IBD patients undergo surveillance at specific time points of their disease with the aim to detect and potentially treat early CRN.

But these procedures are costly and burdensome to patients, and some previous studies have revealed a relatively low utility for patients, according to Kimberley van der Sloot, MD, a PhD candidate at the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands). She presented the research at the annual congress of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association. The study was also published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“We aimed to explore the role of cigarette exposure in colorectal neoplasia risk in patients with IBD, and we aimed to improve the CRN risk stratification model that we are currently using for these surveillance guidelines,” Dr. van der Sloot said during her talk.

Commenters during the Q&A period noted that the population database used in the study did not include measures of inflammation, which is a known risk for CRN. One review found that smoking worsens inflammation in Crohn’s disease but improves it in ulcerative colitis.

“It certainly raises the issue that we’ve always said, which is that people should quit smoking for other health reasons, but it doesn’t necessarily answer the question definitively,” said David Rubin, MD, who moderated the session and is professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and chair of the congress’s organizing committee. He added that the association between smoking and CRN risk may nevertheless inform future management surveillance guidelines if it is confirmed.

The researchers analyzed data from the 1000IBD cohort, which is prospectively following IBD patients in the Netherlands. The study included 1,386 patients who had at least one colorectal biopsy. Compared to a general population CRN incidence of 2.4%, Crohn’s disease patients who were never smokers had an incidence of 4.7% versus 10.3% among former or current smokers. In ulcerative colitis, the incidence was 12.5% among never smokers and 17.9% among former or current smokers.

In Crohn’s disease, previous or current smokers had about a twofold increased risk (hazard ratio, 2.04; P = .044). Compared to never smokers, former smokers trended toward an increased risk (HR, 2.16; P = .051), and active smokers had a significantly increased risk (HR, 2.20; P = .044). Passive smoke exposure was also associated with greater risk, both in childhood (HR, 4.79; P = .003) and current (HR, 1.87; P = .024).

In ulcerative colitis, the only statistically significant association between smoke exposure and CRN risk was among former smokers (HR, 1.73; P = .032).

The researchers also looked at patients with a disease duration longer than 8 years and stratified patients according to low risk (left-side ulcerative colitis, <50% of colon affected in Crohn’s disease; n = 425), medium risk (postinflammatory polyposis present or extensive colitis; n = 467), and high risk (concordant primary sclerosing cholangitis or having a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer; n = 143). In Crohn’s disease, current smoking was associated with greater CRN incidence (P = .046), and former smoking trended in that direction but was nonsignificant (P = .068). Former smoking also trended toward a risk in ulcerative colitis (P = .068), but there was no sign of an association for current smoking (P = .883).

In Crohn’s disease, after adjustment for risk stratification, greater CRN risk was associated with passive smoke exposure both during childhood (P = .001) and at present (P = .003).

“We believe this is the first study to describe the important role of cigarette smoking in development of colorectal neoplasia in IBD patients in a large, prospective, cohort, and I think [it] has shown the importance of lifestyle and smoking particularly in IBD. This is one more example. Alongside that, we’ve shown that adding this risk factor can improve the current risk stratification that is used for surveillance guidelines, and might be of benefit in the development of future guidelines,” said Dr. van der Sloot.

Dr. van der Sloot and Dr. Rubin had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated Mar. 11, 2021.

Cigarette smoking may be associated with a higher probability of developing colorectal neoplasia (CRN) among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a finding that if confirmed could help to refine colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines. IBD patients undergo surveillance at specific time points of their disease with the aim to detect and potentially treat early CRN.

But these procedures are costly and burdensome to patients, and some previous studies have revealed a relatively low utility for patients, according to Kimberley van der Sloot, MD, a PhD candidate at the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands). She presented the research at the annual congress of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association. The study was also published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“We aimed to explore the role of cigarette exposure in colorectal neoplasia risk in patients with IBD, and we aimed to improve the CRN risk stratification model that we are currently using for these surveillance guidelines,” Dr. van der Sloot said during her talk.

Commenters during the Q&A period noted that the population database used in the study did not include measures of inflammation, which is a known risk for CRN. One review found that smoking worsens inflammation in Crohn’s disease but improves it in ulcerative colitis.

“It certainly raises the issue that we’ve always said, which is that people should quit smoking for other health reasons, but it doesn’t necessarily answer the question definitively,” said David Rubin, MD, who moderated the session and is professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and chair of the congress’s organizing committee. He added that the association between smoking and CRN risk may nevertheless inform future management surveillance guidelines if it is confirmed.

The researchers analyzed data from the 1000IBD cohort, which is prospectively following IBD patients in the Netherlands. The study included 1,386 patients who had at least one colorectal biopsy. Compared to a general population CRN incidence of 2.4%, Crohn’s disease patients who were never smokers had an incidence of 4.7% versus 10.3% among former or current smokers. In ulcerative colitis, the incidence was 12.5% among never smokers and 17.9% among former or current smokers.

In Crohn’s disease, previous or current smokers had about a twofold increased risk (hazard ratio, 2.04; P = .044). Compared to never smokers, former smokers trended toward an increased risk (HR, 2.16; P = .051), and active smokers had a significantly increased risk (HR, 2.20; P = .044). Passive smoke exposure was also associated with greater risk, both in childhood (HR, 4.79; P = .003) and current (HR, 1.87; P = .024).

In ulcerative colitis, the only statistically significant association between smoke exposure and CRN risk was among former smokers (HR, 1.73; P = .032).

The researchers also looked at patients with a disease duration longer than 8 years and stratified patients according to low risk (left-side ulcerative colitis, <50% of colon affected in Crohn’s disease; n = 425), medium risk (postinflammatory polyposis present or extensive colitis; n = 467), and high risk (concordant primary sclerosing cholangitis or having a first-degree relative with colorectal cancer; n = 143). In Crohn’s disease, current smoking was associated with greater CRN incidence (P = .046), and former smoking trended in that direction but was nonsignificant (P = .068). Former smoking also trended toward a risk in ulcerative colitis (P = .068), but there was no sign of an association for current smoking (P = .883).

In Crohn’s disease, after adjustment for risk stratification, greater CRN risk was associated with passive smoke exposure both during childhood (P = .001) and at present (P = .003).

“We believe this is the first study to describe the important role of cigarette smoking in development of colorectal neoplasia in IBD patients in a large, prospective, cohort, and I think [it] has shown the importance of lifestyle and smoking particularly in IBD. This is one more example. Alongside that, we’ve shown that adding this risk factor can improve the current risk stratification that is used for surveillance guidelines, and might be of benefit in the development of future guidelines,” said Dr. van der Sloot.

Dr. van der Sloot and Dr. Rubin had no relevant financial disclosures.

This article was updated Mar. 11, 2021.

FROM THE CROHN’S AND COLITIS CONGRESS

Impact of comorbid migraine on propranolol efficacy for painful TMD

Key clinical point: Propranolol appears more effective in reducing temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pain among migraineurs, with more of the effect mediated by reduced heart rate than by decreased headache impact.

Major finding: Efficacy of propranolol for at least 30% reduction in facial pain index at week 9 was higher among 104 migraineurs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.3; P = .009; P for treatment group interaction = .139) than 95 non-migraineurs (aOR, 1.3; P = .631; P for treatment group interaction = .139). Only 9% of the treatment effect was mediated by reduced headache, whereas 46% was mediated by reduced heart rate.

Study details: Data come from SOPPRANO, a phase 2b randomized controlled trial that investigated analgesic efficacy of propranolol in 200 patients with chronic myogenous TMD randomly allocated to either propranolol or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Tchivileva IE et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 9. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989268.

Key clinical point: Propranolol appears more effective in reducing temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pain among migraineurs, with more of the effect mediated by reduced heart rate than by decreased headache impact.

Major finding: Efficacy of propranolol for at least 30% reduction in facial pain index at week 9 was higher among 104 migraineurs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.3; P = .009; P for treatment group interaction = .139) than 95 non-migraineurs (aOR, 1.3; P = .631; P for treatment group interaction = .139). Only 9% of the treatment effect was mediated by reduced headache, whereas 46% was mediated by reduced heart rate.

Study details: Data come from SOPPRANO, a phase 2b randomized controlled trial that investigated analgesic efficacy of propranolol in 200 patients with chronic myogenous TMD randomly allocated to either propranolol or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Tchivileva IE et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 9. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989268.

Key clinical point: Propranolol appears more effective in reducing temporomandibular disorder (TMD) pain among migraineurs, with more of the effect mediated by reduced heart rate than by decreased headache impact.

Major finding: Efficacy of propranolol for at least 30% reduction in facial pain index at week 9 was higher among 104 migraineurs (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 3.3; P = .009; P for treatment group interaction = .139) than 95 non-migraineurs (aOR, 1.3; P = .631; P for treatment group interaction = .139). Only 9% of the treatment effect was mediated by reduced headache, whereas 46% was mediated by reduced heart rate.

Study details: Data come from SOPPRANO, a phase 2b randomized controlled trial that investigated analgesic efficacy of propranolol in 200 patients with chronic myogenous TMD randomly allocated to either propranolol or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Source: Tchivileva IE et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 9. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989268.

Is the keto diet effective for refractory chronic migraine?

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Galcanezumab may alleviate severity and symptoms of migraine

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Lasmiditan demonstrates superior pain freedom at 2 hours in at least 2 of 3 migraine attacks

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Hyperkeratotic Nummular Plaques on the Upper Trunk

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

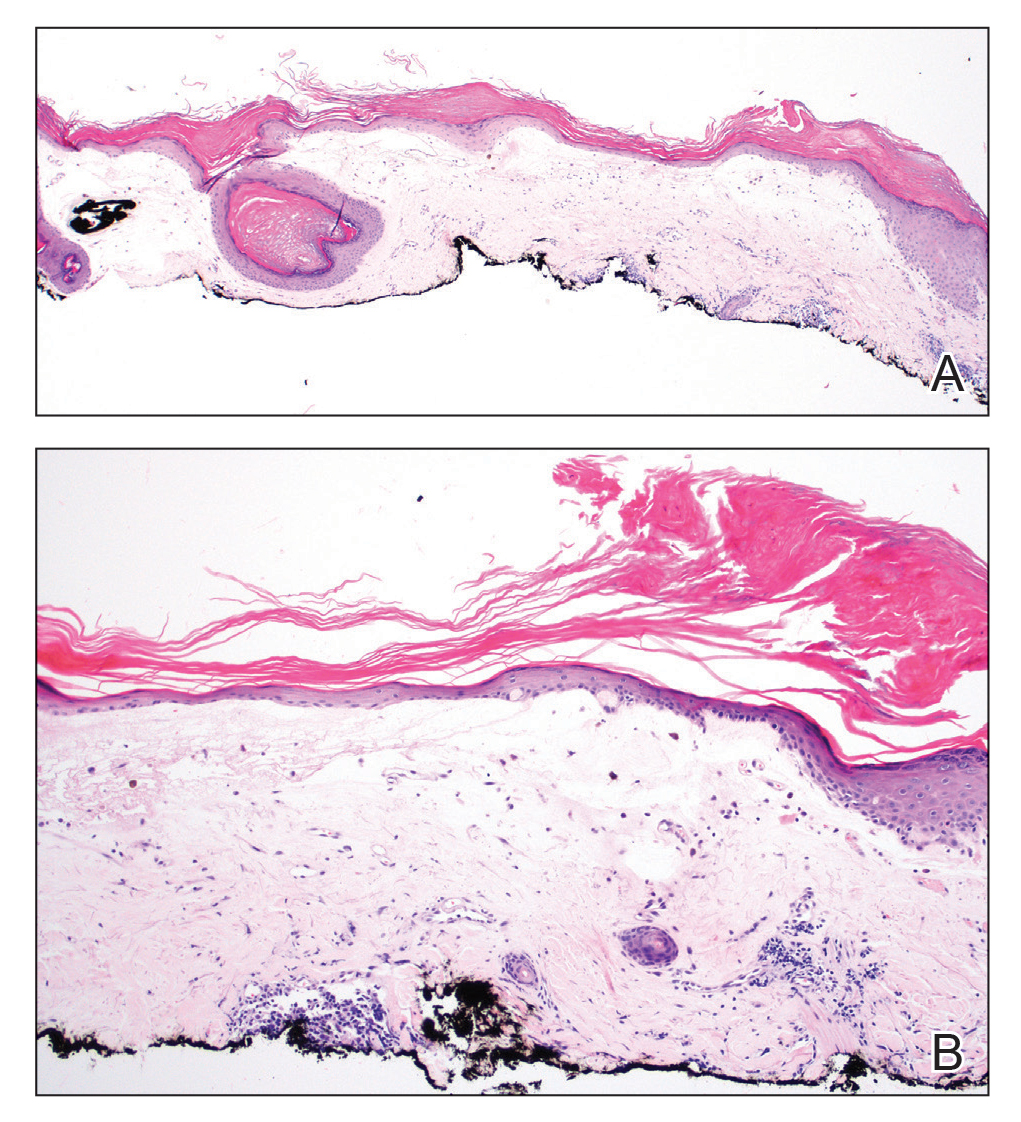

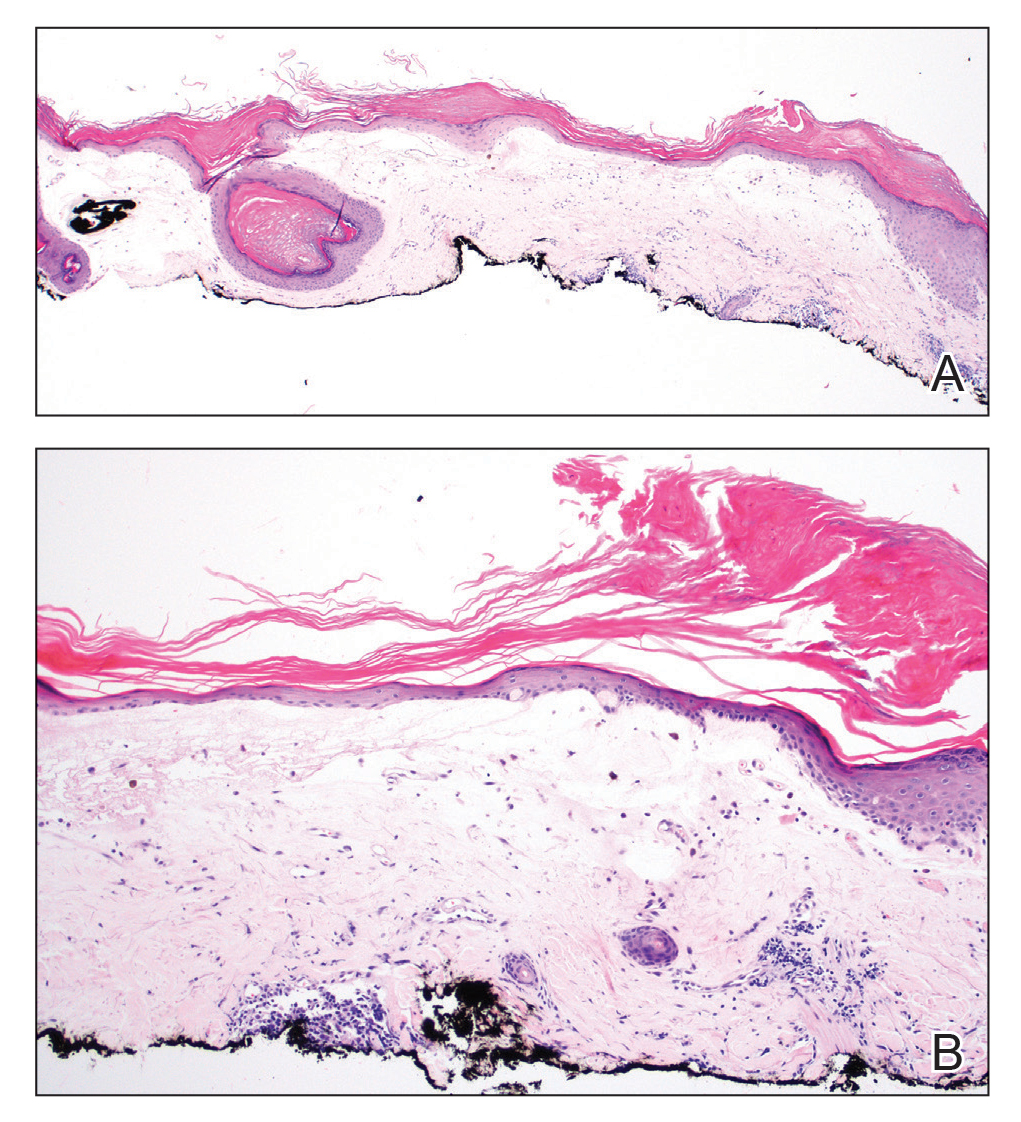

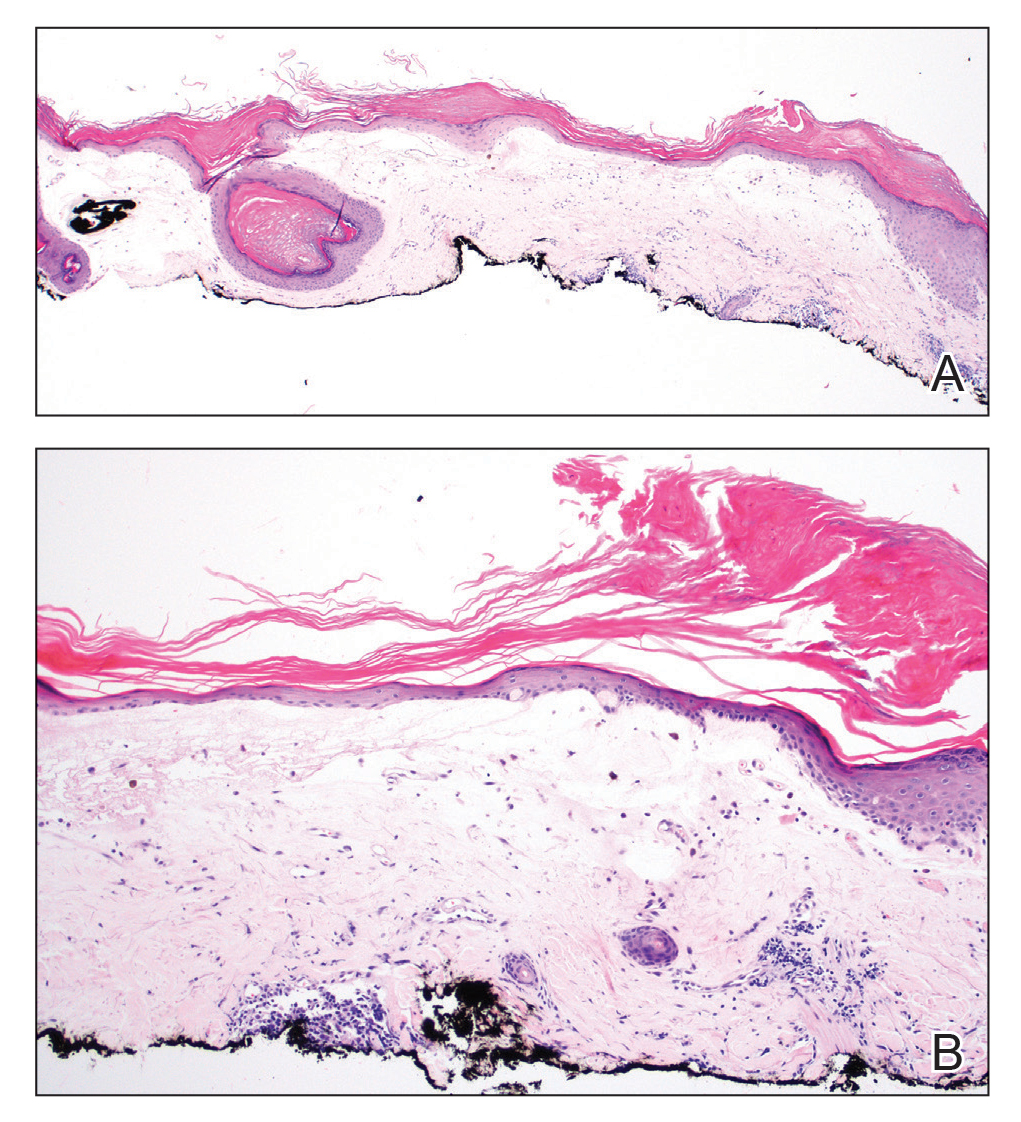

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

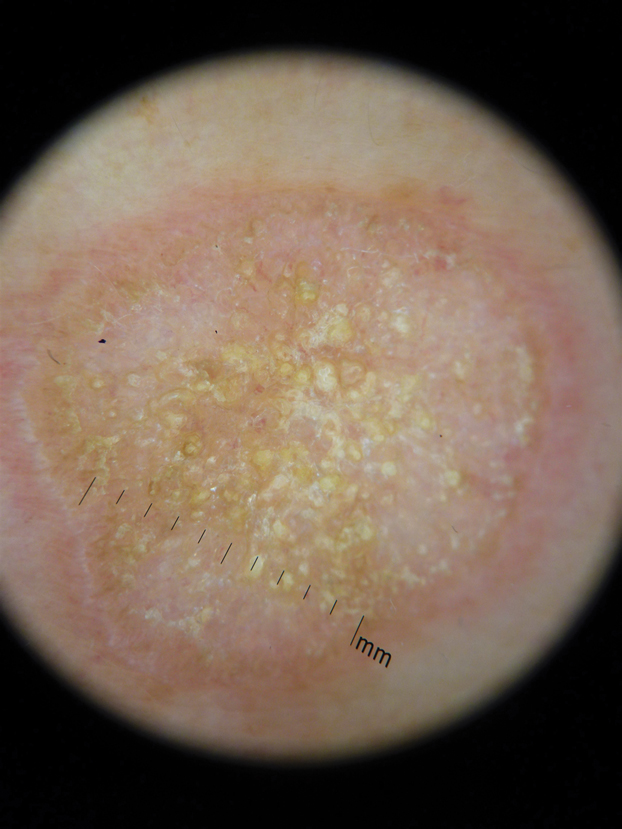

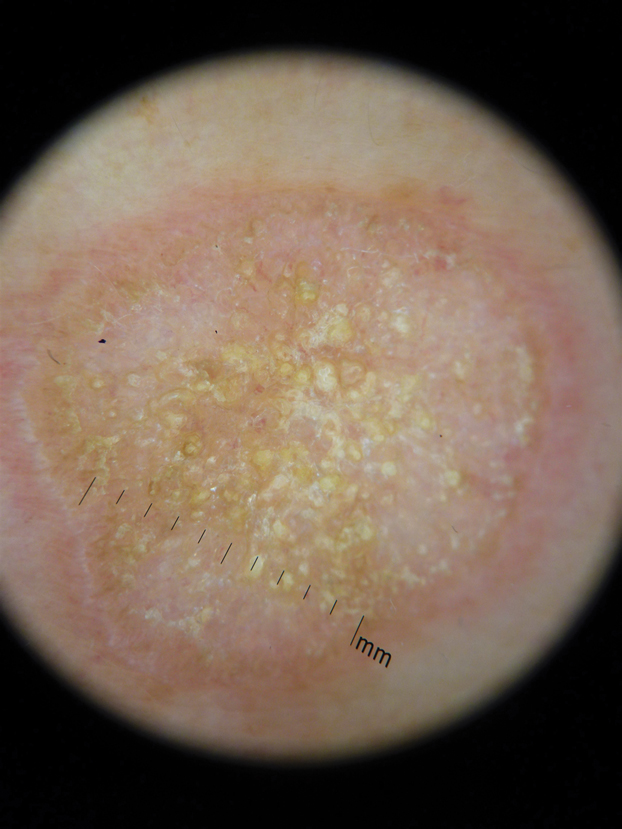

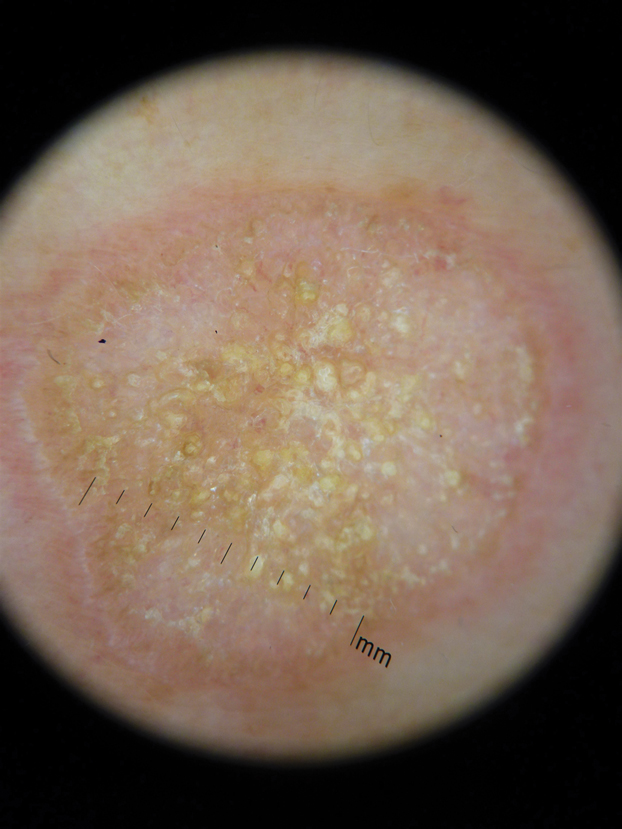

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.