User login

Evidence helps, but some decisions remain within the art of medicine

Despite advances in therapy, more than 10% of patients with acute bacterial meningitis still die of it, and more suffer significant morbidity, including cognitive dysfunction and deafness. Well-defined protocols that include empiric antibiotics and systemic corticosteroids have improved the outcomes of patients with meningitis. But, as with other closed-space infections such as septic arthritis, any delay in providing appropriate antibiotic treatment is associated with a worse prognosis. In the case of bacterial meningitis, a retrospective analysis concluded that each hour of delay in delivering antibiotics and a corticosteroid can be associated with a relative (not absolute) increase in mortality of 13%.1

The precise diagnosis of bacterial meningitis depends entirely on obtaining cerebrospinal fluid for analysis, including culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing. But that simple statement belies several current and historical complexities. From my experience, getting a prompt diagnostic lumbar puncture is not as simple as it once was.

Many hospitals have imposed patient safety initiatives, which overall have been beneficial but have had the effect that medical residents and probably even hospitalists in some medical centers are less frequently the ones doing interventional procedures. Some procedures, such as placement of pulmonary arterial catheters in the medical intensive care unit, have been shown to be less useful and to pose more risk than once believed. The tasks of placing other central lines and performing thoracenteses have been relegated to special procedure teams trained in using ultrasound guidance. Interventional radiologists now often do the visceral biopsies and lumbar punctures, and as a result, it is hoped that procedural complication rates will decline. On the other hand, these changes mean that medical residents and future staff are less experienced in performing these procedures, even though there are times that they are the only ones available to perform them. The result is a potential delay in performing a necessary lumbar puncture.

Another reason that a lumbar puncture may be delayed is concern over iatrogenic herniation if the procedure is done in a patient who has elevated intracranial pressure. We do not know precisely how often this occurs if there is an undiagnosed brain mass lesion such as an abscess, which can mimic bacterial meningitis, or a malignancy, and meningitis itself may be associated with herniation. Yet, for years physicians have hesitated to perform lumbar punctures in some patients without first ruling out a brain mass by computed tomography (CT), a diagnostic flow algorithm that often introduces at least an hour of delay in performing the procedure and in obtaining cultures before starting antibiotics.

When I was in training, we were perhaps more cavalier, appropriately or not. If the history and examination did not suggest a brain mass and the patient had retinal vein pulsations without papilledema, we did the lumbar puncture. It was a different time, and there was a different perspective on risks and benefits. More recently, the trend has been to obtain a CT scan before a lumbar puncture in several subsets of patients.

A 2015 analysis from Sweden1 showed that we can probably do a lumbar puncture for suspected bacterial meningitis without first doing a CT scan in most patients, even in patients with moderately impaired mentation. Perhaps some other concerns can also be assuaged if evaluated, but we don’t have data. Mirrakhimov et al, in this issue of the Journal, review the current evidence on when to do CT before a lumbar puncture, even if it may significantly delay the procedure and the timely delivery of antibiotics. A perfect algorithm that balances the risks of delaying treatment, initiating less-than-ideal empiric antibiotics potentially without definitive culture, and inducing complications from a procedure done promptly may well be impossible to develop. Evidence helps us refine the diagnostic approach, but with limited data, some important decisions unfortunately remain within the “art” rather than the science of medicine.

- Glimåker M, Johansson B, Grindborg Ö, Bottai M, Lindquist L, Sjölin J. Adult bacterial meningitis: earlier treatment and improved outcome following guideline revision promoting prompt lumbar puncture. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1162–1169.

Despite advances in therapy, more than 10% of patients with acute bacterial meningitis still die of it, and more suffer significant morbidity, including cognitive dysfunction and deafness. Well-defined protocols that include empiric antibiotics and systemic corticosteroids have improved the outcomes of patients with meningitis. But, as with other closed-space infections such as septic arthritis, any delay in providing appropriate antibiotic treatment is associated with a worse prognosis. In the case of bacterial meningitis, a retrospective analysis concluded that each hour of delay in delivering antibiotics and a corticosteroid can be associated with a relative (not absolute) increase in mortality of 13%.1

The precise diagnosis of bacterial meningitis depends entirely on obtaining cerebrospinal fluid for analysis, including culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing. But that simple statement belies several current and historical complexities. From my experience, getting a prompt diagnostic lumbar puncture is not as simple as it once was.

Many hospitals have imposed patient safety initiatives, which overall have been beneficial but have had the effect that medical residents and probably even hospitalists in some medical centers are less frequently the ones doing interventional procedures. Some procedures, such as placement of pulmonary arterial catheters in the medical intensive care unit, have been shown to be less useful and to pose more risk than once believed. The tasks of placing other central lines and performing thoracenteses have been relegated to special procedure teams trained in using ultrasound guidance. Interventional radiologists now often do the visceral biopsies and lumbar punctures, and as a result, it is hoped that procedural complication rates will decline. On the other hand, these changes mean that medical residents and future staff are less experienced in performing these procedures, even though there are times that they are the only ones available to perform them. The result is a potential delay in performing a necessary lumbar puncture.

Another reason that a lumbar puncture may be delayed is concern over iatrogenic herniation if the procedure is done in a patient who has elevated intracranial pressure. We do not know precisely how often this occurs if there is an undiagnosed brain mass lesion such as an abscess, which can mimic bacterial meningitis, or a malignancy, and meningitis itself may be associated with herniation. Yet, for years physicians have hesitated to perform lumbar punctures in some patients without first ruling out a brain mass by computed tomography (CT), a diagnostic flow algorithm that often introduces at least an hour of delay in performing the procedure and in obtaining cultures before starting antibiotics.

When I was in training, we were perhaps more cavalier, appropriately or not. If the history and examination did not suggest a brain mass and the patient had retinal vein pulsations without papilledema, we did the lumbar puncture. It was a different time, and there was a different perspective on risks and benefits. More recently, the trend has been to obtain a CT scan before a lumbar puncture in several subsets of patients.

A 2015 analysis from Sweden1 showed that we can probably do a lumbar puncture for suspected bacterial meningitis without first doing a CT scan in most patients, even in patients with moderately impaired mentation. Perhaps some other concerns can also be assuaged if evaluated, but we don’t have data. Mirrakhimov et al, in this issue of the Journal, review the current evidence on when to do CT before a lumbar puncture, even if it may significantly delay the procedure and the timely delivery of antibiotics. A perfect algorithm that balances the risks of delaying treatment, initiating less-than-ideal empiric antibiotics potentially without definitive culture, and inducing complications from a procedure done promptly may well be impossible to develop. Evidence helps us refine the diagnostic approach, but with limited data, some important decisions unfortunately remain within the “art” rather than the science of medicine.

Despite advances in therapy, more than 10% of patients with acute bacterial meningitis still die of it, and more suffer significant morbidity, including cognitive dysfunction and deafness. Well-defined protocols that include empiric antibiotics and systemic corticosteroids have improved the outcomes of patients with meningitis. But, as with other closed-space infections such as septic arthritis, any delay in providing appropriate antibiotic treatment is associated with a worse prognosis. In the case of bacterial meningitis, a retrospective analysis concluded that each hour of delay in delivering antibiotics and a corticosteroid can be associated with a relative (not absolute) increase in mortality of 13%.1

The precise diagnosis of bacterial meningitis depends entirely on obtaining cerebrospinal fluid for analysis, including culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing. But that simple statement belies several current and historical complexities. From my experience, getting a prompt diagnostic lumbar puncture is not as simple as it once was.

Many hospitals have imposed patient safety initiatives, which overall have been beneficial but have had the effect that medical residents and probably even hospitalists in some medical centers are less frequently the ones doing interventional procedures. Some procedures, such as placement of pulmonary arterial catheters in the medical intensive care unit, have been shown to be less useful and to pose more risk than once believed. The tasks of placing other central lines and performing thoracenteses have been relegated to special procedure teams trained in using ultrasound guidance. Interventional radiologists now often do the visceral biopsies and lumbar punctures, and as a result, it is hoped that procedural complication rates will decline. On the other hand, these changes mean that medical residents and future staff are less experienced in performing these procedures, even though there are times that they are the only ones available to perform them. The result is a potential delay in performing a necessary lumbar puncture.

Another reason that a lumbar puncture may be delayed is concern over iatrogenic herniation if the procedure is done in a patient who has elevated intracranial pressure. We do not know precisely how often this occurs if there is an undiagnosed brain mass lesion such as an abscess, which can mimic bacterial meningitis, or a malignancy, and meningitis itself may be associated with herniation. Yet, for years physicians have hesitated to perform lumbar punctures in some patients without first ruling out a brain mass by computed tomography (CT), a diagnostic flow algorithm that often introduces at least an hour of delay in performing the procedure and in obtaining cultures before starting antibiotics.

When I was in training, we were perhaps more cavalier, appropriately or not. If the history and examination did not suggest a brain mass and the patient had retinal vein pulsations without papilledema, we did the lumbar puncture. It was a different time, and there was a different perspective on risks and benefits. More recently, the trend has been to obtain a CT scan before a lumbar puncture in several subsets of patients.

A 2015 analysis from Sweden1 showed that we can probably do a lumbar puncture for suspected bacterial meningitis without first doing a CT scan in most patients, even in patients with moderately impaired mentation. Perhaps some other concerns can also be assuaged if evaluated, but we don’t have data. Mirrakhimov et al, in this issue of the Journal, review the current evidence on when to do CT before a lumbar puncture, even if it may significantly delay the procedure and the timely delivery of antibiotics. A perfect algorithm that balances the risks of delaying treatment, initiating less-than-ideal empiric antibiotics potentially without definitive culture, and inducing complications from a procedure done promptly may well be impossible to develop. Evidence helps us refine the diagnostic approach, but with limited data, some important decisions unfortunately remain within the “art” rather than the science of medicine.

- Glimåker M, Johansson B, Grindborg Ö, Bottai M, Lindquist L, Sjölin J. Adult bacterial meningitis: earlier treatment and improved outcome following guideline revision promoting prompt lumbar puncture. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1162–1169.

- Glimåker M, Johansson B, Grindborg Ö, Bottai M, Lindquist L, Sjölin J. Adult bacterial meningitis: earlier treatment and improved outcome following guideline revision promoting prompt lumbar puncture. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1162–1169.

Urinary leakage: What are the treatment options?

Urinary incontinence—the loss of bladder control—affects 15 million American women. Many endure it in silence, thinking that it is a normal part of aging or that no medical urinary incontinence treatments exist. But in many cases it can be managed through exercise, lifestyle changes, pelvic stimulation, and sometimes medicines or other treatments.

Types of urinary incontinence

Urgency incontinence causes an urgent desire to urinate (void), which is followed by involuntary loss of urine. This condition can be caused by an “overactive” bladder, or OAB. Normally, strong muscles (sphincters) control the flow of urine from the bladder. In OAB, the muscles contract or spasm with enough force to override the sphincter muscles of the urethra and allow urine to pass out of the bladder.

Stress incontinence occurs when an activity such as a coughing or sneezing increases pressure on the bladder. Typically, a small amount of urine leaks from the urethra. This problem can be caused by weak muscles of the pelvic floor, a weak sphincter muscle, or a problem with the way the sphincter muscle opens and closes. Women who have given birth are more likely to have stress incontinence.

Women with mixed incontinence have symptoms of both urgency and stress incontinence.

Treatment options

For urge incontinence, doctors generally recommend:

- Bladder training. You would complete a bladder diary to determine how often you urinate and then try to lengthen the time between voids.

- Kegel exercises. These help strengthen the pelvic muscles, improving pelvic support and the bladder’s ability to hold urine. When you try to stop the flow of urine or try not to pass gas, you are contracting the muscles of the pelvic floor. This is what happens when you do Kegel exercises. When doing the exercises, try not to move your legs, buttocks, or abdominal muscles. In fact, no one should be able to see that you are doing them. Do 5 sets of Kegel exercises a day. Each time you contract the muscles of the pelvic floor, hold for a slow count of 5 and then relax. Repeat this 10 times for 1 set of Kegels.

- Medications such as antidepressant drugs may be prescribed to relax the bladder. Other drugs, called anticholinergic drugs, help control muscle spasms in the bladder.

For stress incontinence, doctors generally recommend:

- Bladder training and Kegel exercises, as described above.

- Bulking agents, which are injected into the lining of the urethra. They increase the thickness of the lining of the urethra, which creates resistance against the flow of urine. Collagen is one bulking agent commonly used.

Treatments for either type of urinary incontinence include:

- Vaginal estrogen—this is used by women who are going through menopause or who are postmenopausal. Vaginal estrogen is provided in the form of creams, tablets, or a ring inserted into the vagina. It works in part by thickening the vaginal tissue, which increases pelvic support, and by relieving tissue irritation.

- Pelvic stimulation. Mild electrical impulses stimulate contractions of the pelvic floor muscles, and this eventually strengthens them. Some devices require a prescription and monthly office visits and are connected to biofeedback. Others, such as the Automatic Pelvic Exerciser (APEX M), are available over the counter.

- Biofeedback therapy with a physical therapist can help you learn how to perform Kegel exercises by letting you know if you are contracting your pelvic muscles correctly. Sensors are placed on the body or within the anus or vagina and provide feedback on a computer screen or through audio tones.

- Weight loss. Being overweight or obese can lead to urinary incontinence by increasing pressure in the abdomen. Losing even 5 pounds can make a big difference in bladder control.

This information is provided by your physician and the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. It does not replace your physician’s medical assessment and judgment.

This page may be reproduced noncommercially. For information on hundreds of health topics, see my.clevelandclinic.org/health.

Urinary incontinence—the loss of bladder control—affects 15 million American women. Many endure it in silence, thinking that it is a normal part of aging or that no medical urinary incontinence treatments exist. But in many cases it can be managed through exercise, lifestyle changes, pelvic stimulation, and sometimes medicines or other treatments.

Types of urinary incontinence

Urgency incontinence causes an urgent desire to urinate (void), which is followed by involuntary loss of urine. This condition can be caused by an “overactive” bladder, or OAB. Normally, strong muscles (sphincters) control the flow of urine from the bladder. In OAB, the muscles contract or spasm with enough force to override the sphincter muscles of the urethra and allow urine to pass out of the bladder.

Stress incontinence occurs when an activity such as a coughing or sneezing increases pressure on the bladder. Typically, a small amount of urine leaks from the urethra. This problem can be caused by weak muscles of the pelvic floor, a weak sphincter muscle, or a problem with the way the sphincter muscle opens and closes. Women who have given birth are more likely to have stress incontinence.

Women with mixed incontinence have symptoms of both urgency and stress incontinence.

Treatment options

For urge incontinence, doctors generally recommend:

- Bladder training. You would complete a bladder diary to determine how often you urinate and then try to lengthen the time between voids.

- Kegel exercises. These help strengthen the pelvic muscles, improving pelvic support and the bladder’s ability to hold urine. When you try to stop the flow of urine or try not to pass gas, you are contracting the muscles of the pelvic floor. This is what happens when you do Kegel exercises. When doing the exercises, try not to move your legs, buttocks, or abdominal muscles. In fact, no one should be able to see that you are doing them. Do 5 sets of Kegel exercises a day. Each time you contract the muscles of the pelvic floor, hold for a slow count of 5 and then relax. Repeat this 10 times for 1 set of Kegels.

- Medications such as antidepressant drugs may be prescribed to relax the bladder. Other drugs, called anticholinergic drugs, help control muscle spasms in the bladder.

For stress incontinence, doctors generally recommend:

- Bladder training and Kegel exercises, as described above.

- Bulking agents, which are injected into the lining of the urethra. They increase the thickness of the lining of the urethra, which creates resistance against the flow of urine. Collagen is one bulking agent commonly used.

Treatments for either type of urinary incontinence include:

- Vaginal estrogen—this is used by women who are going through menopause or who are postmenopausal. Vaginal estrogen is provided in the form of creams, tablets, or a ring inserted into the vagina. It works in part by thickening the vaginal tissue, which increases pelvic support, and by relieving tissue irritation.

- Pelvic stimulation. Mild electrical impulses stimulate contractions of the pelvic floor muscles, and this eventually strengthens them. Some devices require a prescription and monthly office visits and are connected to biofeedback. Others, such as the Automatic Pelvic Exerciser (APEX M), are available over the counter.

- Biofeedback therapy with a physical therapist can help you learn how to perform Kegel exercises by letting you know if you are contracting your pelvic muscles correctly. Sensors are placed on the body or within the anus or vagina and provide feedback on a computer screen or through audio tones.

- Weight loss. Being overweight or obese can lead to urinary incontinence by increasing pressure in the abdomen. Losing even 5 pounds can make a big difference in bladder control.

This information is provided by your physician and the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. It does not replace your physician’s medical assessment and judgment.

This page may be reproduced noncommercially. For information on hundreds of health topics, see my.clevelandclinic.org/health.

Urinary incontinence—the loss of bladder control—affects 15 million American women. Many endure it in silence, thinking that it is a normal part of aging or that no medical urinary incontinence treatments exist. But in many cases it can be managed through exercise, lifestyle changes, pelvic stimulation, and sometimes medicines or other treatments.

Types of urinary incontinence

Urgency incontinence causes an urgent desire to urinate (void), which is followed by involuntary loss of urine. This condition can be caused by an “overactive” bladder, or OAB. Normally, strong muscles (sphincters) control the flow of urine from the bladder. In OAB, the muscles contract or spasm with enough force to override the sphincter muscles of the urethra and allow urine to pass out of the bladder.

Stress incontinence occurs when an activity such as a coughing or sneezing increases pressure on the bladder. Typically, a small amount of urine leaks from the urethra. This problem can be caused by weak muscles of the pelvic floor, a weak sphincter muscle, or a problem with the way the sphincter muscle opens and closes. Women who have given birth are more likely to have stress incontinence.

Women with mixed incontinence have symptoms of both urgency and stress incontinence.

Treatment options

For urge incontinence, doctors generally recommend:

- Bladder training. You would complete a bladder diary to determine how often you urinate and then try to lengthen the time between voids.

- Kegel exercises. These help strengthen the pelvic muscles, improving pelvic support and the bladder’s ability to hold urine. When you try to stop the flow of urine or try not to pass gas, you are contracting the muscles of the pelvic floor. This is what happens when you do Kegel exercises. When doing the exercises, try not to move your legs, buttocks, or abdominal muscles. In fact, no one should be able to see that you are doing them. Do 5 sets of Kegel exercises a day. Each time you contract the muscles of the pelvic floor, hold for a slow count of 5 and then relax. Repeat this 10 times for 1 set of Kegels.

- Medications such as antidepressant drugs may be prescribed to relax the bladder. Other drugs, called anticholinergic drugs, help control muscle spasms in the bladder.

For stress incontinence, doctors generally recommend:

- Bladder training and Kegel exercises, as described above.

- Bulking agents, which are injected into the lining of the urethra. They increase the thickness of the lining of the urethra, which creates resistance against the flow of urine. Collagen is one bulking agent commonly used.

Treatments for either type of urinary incontinence include:

- Vaginal estrogen—this is used by women who are going through menopause or who are postmenopausal. Vaginal estrogen is provided in the form of creams, tablets, or a ring inserted into the vagina. It works in part by thickening the vaginal tissue, which increases pelvic support, and by relieving tissue irritation.

- Pelvic stimulation. Mild electrical impulses stimulate contractions of the pelvic floor muscles, and this eventually strengthens them. Some devices require a prescription and monthly office visits and are connected to biofeedback. Others, such as the Automatic Pelvic Exerciser (APEX M), are available over the counter.

- Biofeedback therapy with a physical therapist can help you learn how to perform Kegel exercises by letting you know if you are contracting your pelvic muscles correctly. Sensors are placed on the body or within the anus or vagina and provide feedback on a computer screen or through audio tones.

- Weight loss. Being overweight or obese can lead to urinary incontinence by increasing pressure in the abdomen. Losing even 5 pounds can make a big difference in bladder control.

This information is provided by your physician and the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. It does not replace your physician’s medical assessment and judgment.

This page may be reproduced noncommercially. For information on hundreds of health topics, see my.clevelandclinic.org/health.

Medical management of urinary incontinence in women

Urinary incontinence can lead to a cascade of symptomatic burden on the patient, causing distress, embarrassment, and suffering.

See related patient information

Traditionally, incontinence has been treated by surgeons, and surgery remains an option. However, more patients are now being managed by medical clinicians, who can offer a number of newer therapies. Ideally, a medical physician can initiate the evaluation and treatment and even effectively cure some forms of urinary incontinence.

In 2014, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published recommendations on the medical treatment of urinary incontinence in women (Table 1).1

This review describes the medical management of urinary incontinence in women, emphasizing the ACP recommendations1 and newer over-the-counter options.

COMMON AND UNDERREPORTED

Many women erroneously believe that urinary incontinence is an inevitable consequence of aging and allow it to lessen their quality of life without seeking medical attention.

Indeed, it is common. The 2005–2006 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey2 found the prevalence of urinary incontinence in US women to be 15.7%. The prevalence increases with age from 6.9% in women ages 20 through 29 to 31.7% in those age 80 and older. A separate analysis of the same data found that 25.0% of women age 20 and older had 1 or more pelvic floor disorders.3 Some estimates are even higher. Wu et al4 reported a prevalence of urinary incontinence of 51.1% in women ages 31 through 54.

Too few of these women are identified and treated, for many reasons, including embarrassment and inadequate screening. Half of women with urinary incontinence do not report their symptoms because of humiliation or anxiety.5

The burden of urinary incontinence extends beyond the individual and into society. The total cost of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence in the United States was estimated to be $65.9 billion in 2007 and is projected to reach $82.6 billion in 2020.6

THREE TYPES

There are 3 types of urinary incontinence: stress, urgency, and mixed.

Stress urinary incontinence is involuntary loss of urine associated with physical exertion or increased abdominal pressure, eg, with coughing or sneezing.

Urgency urinary incontinence is involuntary loss of urine associated with the sudden need to void. Many patients experience these symptoms simultaneously, making the distinction difficult.

Mixed urinary incontinence is loss of urine with both urgency and increased abdominal pressure or physical exertion.

Overactive bladder, a related problem, is defined as urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence, in the absence of a urinary tract infection or other obvious disease.7

Nongenitourinary causes such as neurologic disorders or even malignancy can present with urinary incontinence, and thus it is critical to perform a thorough initial evaluation.

A 2014 study revealed that by age 80, 20% of women may need to undergo surgery for stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. This statistic should motivate healthcare providers to focus on prevention and offer conservative medical management for these conditions first.8

QUESTIONS TO ASK

When doing a pelvic examination, once could inquire about urinary incontinence with questions such as:

Do you leak urine when you cough, sneeze, laugh, or jump or during sexual climax?

Do you have to get up more than once at night to urinate?

Do you feel the urge to urinate frequently?

BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATION AND BLADDER TRAINING

Bladder training is a conservative behavioral treatment for urinary incontinence that primary care physicians can teach. It is primarily used for urgency urinary incontinence but can also be useful in stress urinary incontinence.

After completing a bladder diary and gaining awareness of their daily voiding patterns, patients can learn scheduled voiding to train the bladder, gradually extending the urges to longer intervals.

Clinicians should instruct patients on how to train the bladder, using methods first described by Wyman and Fantl.9 (See Training the bladder.)

There is evidence that bladder training improves urinary incontinence compared with usual care.10,11

The ACP recommends bladder training for women who have urgency urinary incontinence, but grades this recommendation as weak with low-quality evidence.

PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING

Introduced in 1948 by Dr. Arnold Kegel, pelvic floor muscle training has become widely adopted.12

The pelvic floor consists of a group of muscles, resembling a hammock, that support the pelvic viscera. These muscles include the coccygeus and the layers of the levator ani (Figure 1). A weak pelvic floor is one of many risk factors for developing stress urinary incontinence. Like other muscle groups, a weak pelvic floor can be rehabilitated through various techniques, often guided by a physical therapist.

Compared with those who received no treatment, women with stress urinary incontinence who performed pelvic floor muscle training were 8 times more likely to report being cured and 17 times more likely to report cure or improvement.13

To perform a Kegel exercise, a woman consciously contracts her pelvic floor muscles as if stopping the flow of urine.

The Knack maneuver can be used to prevent leakage during anticipated events that increase intra-abdominal pressure. For example, when a cough or sneeze is imminent, patients can preemptively contract their pelvic floor and hold the contraction through the cough or sneeze.

Although many protocols have been compared, no specific pelvic floor exercise strategy has proven superior. A systematic review assessed variations in pelvic floor interventions, exercises, and delivery and found that there was insufficient evidence to make any recommendations about the best approach. However, the benefit was greater with regular supervision during pelvic floor muscle training than with little or no supervision.14

Pelvic floor muscle training strengthens the pelvic floor, which better supports the bladder neck and anatomically compensates for defects in stress urinary incontinence. In urgency urinary incontinence, a strong pelvic floor created by muscle training prevents leaking induced by the involuntary contractions of the detrusor muscle.

Recommendation

The ACP recommends pelvic floor muscle training as first-line treatment for stress urinary incontinence and mixed urinary incontinence, and grades this recommendation as strong with high-quality evidence.

BIOFEEDBACK AND PELVIC STIMULATION

Although pelvic floor exercises are effective in urinary incontinence, 30% of patients perform them incorrectly.15

Biofeedback therapy uses visual, verbal, and acoustic signals to give the patient immediate feedback and a greater awareness of her muscular activity. A commonly used technique employs a vaginal probe to measure and display pressure changes as the patient contracts her levator ani muscles.

Women who received biofeedback in addition to traditional pelvic floor physical therapy had greater improvement in urinary incontinence than those who received pelvic physical therapy alone (risk ratio 0.75, 95% confidence interval 0.66–0.86).16

Pelvic stimulation can be used separately or in conjunction with biofeedback in both urgency and stress urinary incontinence. When pelvic stimulation is used alone, 9 women need to be treated to achieve continence in 1, and 6 women need to be treated to improve continence in 1.16

Traditionally delivered by a pelvic floor physical therapist, pelvic stimulation and biofeedback have also been validated for home use.17,18 Several pelvic stimulation devices have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating stress, urgency, and mixed urinary incontinence. These devices deliver stimulation to the pelvic floor at single or multiple frequencies. Although the mechanisms are not clearly understood, lower frequencies are used to treat urgency incontinence, while higher frequencies are used for stress incontinence. A theory is that higher-frequency stimulation strengthens the pelvic floor in stress urinary incontinence while lower frequency stimulation calms the detrusor muscle in urgency urinary incontinence.

The Apex and Apex M devices are both available over the counter, the former to treat stress urinary incontinence and the latter to treat mixed urinary incontinence, using pelvic stimulation alone. Other available devices, including the InTone and a smaller version, the InTone MV, are available by prescription and combine pelvic stimulation with biofeedback.18

Women who wish to avoid surgery, botulinum toxin injections, and daily oral medications, particularly those who are highly motivated, are ideal candidates for these over-the-counter automatic neuromuscular pelvic exercising devices.

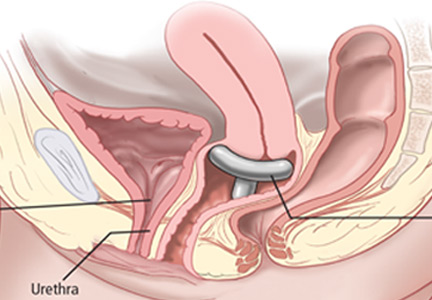

PESSARIES AND OTHER DEVICES

Pessaries are commonly used to treat pelvic organ prolapse but can also be designed to help correct the anatomic defect responsible for stress urinary incontinence. Continence pessaries support the bladder neck so that the urethrovesicular junction is stabilized rather than hypermobile during the increased intra-abdominal pressure that occurs with coughing, sneezing, or physical exertion (Figure 2). In theory, this should decrease leakage.

A systematic review concluded that the value of pessaries in the management of incontinence remains uncertain. However, there are inherent challenges in conducting trials of such devices.19 A pessary needs to be fitted by an appropriately trained healthcare provider. The Ambulatory Treatments for Leakage Associated With Stress Incontinence (ATLAS) trial20 reported that behavioral therapy was more effective than a pessary at 3 months, but the treatments were equivalent at 12 months.

The FDA has approved a disposable, over-the-counter silicone intravaginal device for treating stress urinary incontinence. Patients initially purchase a sizing kit and subsequently insert the nonabsorbent temporary intravaginal bladder supportive device, which is worn for up to 8 hours.

Women may elect to use regular tampons to do the job of a pessary, as they are easy to use and low in cost. No large randomized trials have compared tampons and pessaries, and currently no one device is known to be superior to another.

Overall, these devices are temporizing measures that have few serious adverse effects.

WEIGHT LOSS AND DIETARY CHANGES

Obesity has become a national epidemic, with more than 68% of Americans found to be overweight or obese according to the National Institutes of Health.21

Several studies found obesity to be an independent risk factor for urinary incontinence. As early as 1946, the British Birth Cohort study found that women ages 48 through 54 who were obese earlier in life had a higher risk of urinary incontinence in middle age, and those who were obese by age 20 were more likely to report severe incontinence.22 Likewise, the Nurses’ Health Study showed that women with a body mass index (BMI) more than 30 kg/m2 had 3.1 times the risk of severe incontinence compared with women with a normal BMI. Also, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation and the Leicestershire Medical Research Council (MRC) incontinence study both showed that a higher BMI and weight gain are strongly correlated with urinary incontinence.23,24

Increased intra-abdominal pressure may be the causative mechanism of stress urinary incontinence in obesity. The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that central adiposity correlated with urgency incontinence.25,26

The MRC study was one of the largest to evaluate the effect of diet on urinary symptoms. Consuming a diet dense in vegetables, bread, and chicken was found to reduce the risk of urinary incontinence, while carbonated drinks were associated with a higher risk.25 These studies and others may point to reducing calories, and thus BMI, as a conservative treatment for urinary incontinence.

Newer data show bariatric surgery is associated with a strong reduction in urinary incontinence, demonstrated in a study that followed patients for 3 years after surgery.27 This encouraging result is but one of several positive health outcomes from bariatric surgery.

Recommendation

The ACP recommends both weight loss and exercise for overweight women with urinary incontinence, and grades this as strong with moderate-quality evidence.

DRUG THERAPY

The bladder neck is rich with sympathetic alpha-adrenergic receptors, and the bladder dome is dense with parasympathetic muscarinic receptors and sympathetic beta-adrenergic receptors. When the parasympathetic system is stimulated, the muscarinic receptors are activated, causing detrusor contraction and ultimately bladder emptying.

Agonism of beta-alpha adrenergic receptors and inhibition of parasympathetic receptors are both strategies of drug treatment of urinary incontinence.

Anticholinergic drugs

Anticholinergic medications function by blocking the muscarinic receptor, thereby inhibiting detrusor contraction.

Six oral anticholinergic medications are available: oxybutynin, tolterodine, fesoterodine, solifenacin, trospium, and darifenacin. These drugs have about the same effectiveness in treating urgency urinary incontinence, as measured by achieving continence and improving quality of life.28 Given their similarity in effectiveness, the choice of agent typically relies on the side-effect profile. Extended-release formulations have a more favorable side-effect profile, with fewer cases of dry mouth compared with immediate-release formulations.29

Overall, however, the benefit of these medications is small, with fewer than 200 patients achieving continence per 1,000 treated.28

Other limitations of these medications include their adverse effects and contraindications, and patients’ poor adherence to therapy. The most commonly reported adverse effect is dry mouth, but other common side effects include constipation, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, fatigue, dry eye, and dry skin. Transdermal oxybutynin therapy has been associated with fewer anticholinergic side effects than oral therapy.30

Contraindications to these medications include gastric retention, urinary retention, and angle-closure glaucoma.

Long-term adherence to anticholinergics is low, reported between 14% to 35% after 12 months, with the highest rates of adherence with solifenacin.31 The most commonly cited reason for discontinuation is lack of effect.32

Caution is urged when considering starting anticholinergic medications in older adults because of the central nervous system side effects, including drowsiness, hallucinations, cognitive impairment, and dementia. After 3 weeks, oxybutynin caused a memory decline as measured by delayed recall that was comparable to the decline seen over 10 years in normal aging.33 There is evidence suggesting trospium may cause less cognitive impairment, and therefore may be a better option for older patients.34

Beta-3 adrenoreceptor agonists

Activation of beta-3 adrenergic receptors through the sympathetic nervous system relaxes the detrusor muscle, allowing the bladder to store urine.

Mirabegron is a selective beta-3 adrenoreceptor agonist that effectively relaxes the bladder and increases bladder capacity. It improves continence, treatment satisfaction, and quality of life.35,36 There are fewer reports of dry mouth and constipation with this drug than with the anticholinergics; however, beta-3 adrenoreceptor agonists may be associated with greater risk of hypertension, nasopharyngitis, headache, and urinary tract infection.37

Duloxetine

Duloxetine, an antidepressant, blocks the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine. Consequently, it decreases parasympathetic activity and increases sympathetic and somatic activity in the urinary system.38 While urine is stored, this cascade of neural activity is thought to collectively increase pudendal nerve activity and improve closure of the urethra.

Although duloxetine is approved to treat stress urinary incontinence in Europe, this is an off-label use in the United States.

A meta-analysis39 found that duloxetine improved quality of life in patients with stress urinary incontinence and that subjective cure rates were 10.8% with duloxetine vs 7.7% with placebo (P = .04). However the rate of adverse events is high, with nausea most common. Given its modest benefit and high rate of side effects, physicians may consider starting duloxetine only if there are psychiatric comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, or fibromyalgia.

Recommendations

The ACP recommends against systemic pharmacologic therapy for stress urinary incontinence. For urgency urinary incontinence, pharmacologic therapy is recommended if bladder training fails, and should be individualized based on the patient’s preference and medical comorbidities and the drug’s tolerability, cost, and ease of use.

Hormone therapy

In 2014, the North American Menopause Society recommended replacing the term “vulvovaginal atrophy” with the term genitourinary syndrome of menopause, which better encompasses the postmenopausal changes to the female genital system.40

Estrogen therapy is commercially available in both systemic and local preparations. The effect of exogenous estrogen on urinary incontinence may depend on whether it is given locally or systemically.

A systematic review41 definitively concluded that all commercially prepared local vaginal estrogen preparations can effectively relieve the genitourinary syndrome of menopause, including not only the common complaints of dryness, burning, and irritation but also urinary complaints of frequency, urgency, and urgency urinary incontinence.41 Additionally, the estradiol vaginal ring for vaginal atrophy (Estring) may have dual effects, functioning like an incontinence pessary by supporting the bladder neck while simultaneously providing local estrogen to the atrophied vaginal tissue.

However, in the Women’s Health Initiative,42 continent women who received either systemic estrogen therapy alone or systemic estrogen combined with progestin actually had a higher risk of developing urinary incontinence, and those already experiencing incontinence developed a worsening of their symptoms on systemic hormone therapy. The mechanism by which systemic hormone therapy causes urinary incontinence is unclear; however, previous studies showed that hormone therapy leads to a reduction in periurethral collagen and increased bladder contractility.43,44

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Half of women with symptomatic urinary incontinence never report their symptoms.

- Bladder training is recommended for urgency incontinence and pelvic floor muscle training for stress incontinence.

- Thirty percent of women perform pelvic floor exercises incorrectly.

- Devices can be considered, including automatic pelvic exercise devices for stress and urgency incontinence and incontinence pessaries and disposable intravaginal bladder support devices for stress incontinence.

- Higher BMIs are strongly correlated with urinary incontinence.

- Anticholinergic medications are recommended for urgency but not stress incontinence.

- Vaginal estrogen cream may help with symptoms of urinary urgency, recurrent bladder infections, and nocturia in addition to incontinence.

- Qaseem A, Dallas P, Forciea MA, Starkey M, Denberg TD, Shekelle P; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence in women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161:429–440.

- Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA 2008; 300:1311–1316.

- Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, et al. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123:141–148.

- Wu JM, Stinnett S, Jackson RA, Jacoby A, Learman LA, Kuppermann M. Prevalence and incidence of urinary incontinence in a diverse population of women with noncancerous gynecologic conditions. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2010; 16:284–289.

- Griffiths AN, Makam A, Edward GJ. Should we actively screen for urinary and anal incontinence in the general gynaecology outpatients setting? A prospective observational study. J Obstet Gynaecol 2006; 26:442–444.

- Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Milsom I. Economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence in the United Stated: a systematic review. J Manag Care Pharm 2014; 20:130–140.

- Haylen BT, Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al; International Urogynecological Association; International Continence Society. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 2010; 29:4–20.

- Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123:1201–1206.

- Wyman JF, Fantl JA. Bladder training in the ambulatory care management of urinary incontinence. Urol Nurs 1991; 11:11–17.

- Fantl JA, Wyman JF, McClish DK, et al. Efficacy of bladder training in older women with urinary incontinence. JAMA 1991; 265:609–613.

- Subak LL, Quesenberry CP, Posner SF, Cattolica E, Soghikian K. The effect of behavioral therapy on urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 100:72–78.

- Kegel AH. Progressive resistance exercise in the functional restoration of the perineal muscles. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1948; 56:238–248.

- Domoulin C, Hay-Smith EJ, Mac Habée-Séguin G. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 5:CD005654.

- Hay-Smith EJ, Herderschee R, Dumoulin C, Herbison GP. Comparisons of approaches to pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 12:CD009508.

- Bo K. Pelvic floor muscle strength and response to pelvic floor muscle training for stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 2003; 22:654–658.

- Herderschee R, Hay-Smith EJ, Herbison GP, Roovers JP, Heineman MJ. Feedback or biofeedback to augment pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 7:CD009252.

- Terlikowski R, Dobrzycka B, Kinalski M, Kuryliszyn-Moskal A, Terlikowski SJ. Transvaginal electrical stimulation with surface-EMG biofeedback in managing stress urinary incontinence in women of premenopausal age: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Int Urogynecol J 2013; 17:1631–1638.

- Guralnick ML, Kelly H, Engelke H, Koduri S, O’Connor RC. InTone: a novel pelvic floor rehabilitation device for urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J 2015; 26:99–106.

- Lipp A, Shaw C, Glavind K. Mechanical devices for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 12:CD001756.

- Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 115:609–617.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Overweight and obesity statistics. www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/Pages/overweight-obesity-statistics.aspx. Accessed January 6, 2017.

- Mishra GD, Hardy R, Cardozo L, Kuh D. Body weight through adult life and risk of urinary incontinence in middle-aged women. Results from a British prospective cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008; 32:1415–1422.

- Danforth KN, Townsend MK, Lifford K, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. Risk factors for urinary incontinence among middle age women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006; 194:339–345.

- Waetjen LE, Liao S, Johnson WO, et al. Factors associated with prevalence and incident urinary incontinence in a cohort of midlife women: a longitudinal analysis of data: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 165:309–318.

- Dallosso HM, McGrother CW, Matthews RJ, Donaldson MM; Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study Group. The association of diet and other lifestyle factors with overactive bladder and stress incontinence: a longitudinal study in women. BJU Int 2003; 92:69–77.

- Kim IH, Chung H, Kwon JW. Gender differences in the effect of obesity on chronic diseases among the elderly Koreans. J Korean Med Sci. 2011; 26:250–257.

- Subak LL, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Urinary incontinence before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175:1378–1387.

- Shamliyan T, Wyman JF, Ramakrishnan R, Sainfort F, Kane RL. Benefits and harms of pharmacologic treatment for urinary incontinence in women: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012; 156:861–874, W301–W310.

- Hay-Smith J, Herbison P, Ellis G, Morris A. Which anticholinergic drug for overactive bladder symptoms in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 3:CD005429.

- Davila GW, Daugherty CA, Sanders SW; Transdermal Oxybutynin Study Group. A short term, multicenter, randomized double-blind dose titration study of the efficacy and anticholinergic side effects of transdermal compared to immediate release oral oxybutynin treatment of patients with urge urinary incontinence. J Urol 2001; 166:140–145.

- Wagg A, Compion G, Fahey A, Siddiqui E. Persistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a UK experience. BJU Int 2012; 110:1767–1774.

- Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, et al. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int 2010; 105:1276–1282.

- Kay G, Crook T, Rekeda L, et al. Differential effects of the antimuscarinic agents darifenacin and oxybutynin ER on memory in older subjects. Eur Urol 2006; 50:317–326.

- Staskin D, Kay G, Tannenbaum C, et al. Trospium chloride has no effect on memory testing and is assay undetectable in the central nervous system of older patients with overactive bladder. Int J Clin Pract 2010; 64:1294–1300.

- Chapple CR, Amarenco G, Lopez A, et al; BLOSSOM Investigator Group. A proof of concept study: mirabegron, a new therapy for overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn 2013; 32:1116–1122.

- Nitti VB, Khullar V, van Kerrebroeck P, et al. Mirabegron for the treatment of overactive bladder: a prespecified pooled efficacy analysis and pooled safety analysis of three randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III studies. Int J Clin Pract 2013; 67:619–632.

- Maman K, Aballea S, Nazir J, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of medical treatments for the management of overactive bladder: a systematic literature review and mixed treatment comparison. Eur Urol 2014; 65:755–765.

- Katofiasc MA, Nissen J, Audia JE, Thor KB. Comparison of the effects of serotonin selective, norepinephrine, and dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors on lower urinary tract function in cats. Life Sci 2002; 71:1227–1236.

- Mariappan P, Alhasso A, Ballantyne Z, Grant A, N’Dow J. Duloxetine, a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Eur Urol 2007; 51:67–74.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2014; 21:1063–1068.

- Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 124:1147–1156.

- Hendrix SL, Cochrane BB, Nygaard IE, et al. Effects of estrogen with and without progestin on urinary incontinence. JAMA 2005; 293:935–948.

- Jackson S, James M, Abrams P. The effect of estradiol on vaginal collagen metabolism in postmenopausal women with genuine stress incontinence. BJOG 2002; 109:339–344.

- Lin AD, Levin R, Kogan B, et al. Estrogen induced functional hypertrophy and increased force generation of the female rabbit bladder. Neurourol Urodyn 2006; 25:473–479.

Urinary incontinence can lead to a cascade of symptomatic burden on the patient, causing distress, embarrassment, and suffering.

See related patient information

Traditionally, incontinence has been treated by surgeons, and surgery remains an option. However, more patients are now being managed by medical clinicians, who can offer a number of newer therapies. Ideally, a medical physician can initiate the evaluation and treatment and even effectively cure some forms of urinary incontinence.

In 2014, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published recommendations on the medical treatment of urinary incontinence in women (Table 1).1

This review describes the medical management of urinary incontinence in women, emphasizing the ACP recommendations1 and newer over-the-counter options.

COMMON AND UNDERREPORTED

Many women erroneously believe that urinary incontinence is an inevitable consequence of aging and allow it to lessen their quality of life without seeking medical attention.

Indeed, it is common. The 2005–2006 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey2 found the prevalence of urinary incontinence in US women to be 15.7%. The prevalence increases with age from 6.9% in women ages 20 through 29 to 31.7% in those age 80 and older. A separate analysis of the same data found that 25.0% of women age 20 and older had 1 or more pelvic floor disorders.3 Some estimates are even higher. Wu et al4 reported a prevalence of urinary incontinence of 51.1% in women ages 31 through 54.

Too few of these women are identified and treated, for many reasons, including embarrassment and inadequate screening. Half of women with urinary incontinence do not report their symptoms because of humiliation or anxiety.5

The burden of urinary incontinence extends beyond the individual and into society. The total cost of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence in the United States was estimated to be $65.9 billion in 2007 and is projected to reach $82.6 billion in 2020.6

THREE TYPES

There are 3 types of urinary incontinence: stress, urgency, and mixed.

Stress urinary incontinence is involuntary loss of urine associated with physical exertion or increased abdominal pressure, eg, with coughing or sneezing.

Urgency urinary incontinence is involuntary loss of urine associated with the sudden need to void. Many patients experience these symptoms simultaneously, making the distinction difficult.

Mixed urinary incontinence is loss of urine with both urgency and increased abdominal pressure or physical exertion.

Overactive bladder, a related problem, is defined as urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence, in the absence of a urinary tract infection or other obvious disease.7

Nongenitourinary causes such as neurologic disorders or even malignancy can present with urinary incontinence, and thus it is critical to perform a thorough initial evaluation.

A 2014 study revealed that by age 80, 20% of women may need to undergo surgery for stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. This statistic should motivate healthcare providers to focus on prevention and offer conservative medical management for these conditions first.8

QUESTIONS TO ASK

When doing a pelvic examination, once could inquire about urinary incontinence with questions such as:

Do you leak urine when you cough, sneeze, laugh, or jump or during sexual climax?

Do you have to get up more than once at night to urinate?

Do you feel the urge to urinate frequently?

BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATION AND BLADDER TRAINING

Bladder training is a conservative behavioral treatment for urinary incontinence that primary care physicians can teach. It is primarily used for urgency urinary incontinence but can also be useful in stress urinary incontinence.

After completing a bladder diary and gaining awareness of their daily voiding patterns, patients can learn scheduled voiding to train the bladder, gradually extending the urges to longer intervals.

Clinicians should instruct patients on how to train the bladder, using methods first described by Wyman and Fantl.9 (See Training the bladder.)

There is evidence that bladder training improves urinary incontinence compared with usual care.10,11

The ACP recommends bladder training for women who have urgency urinary incontinence, but grades this recommendation as weak with low-quality evidence.

PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING

Introduced in 1948 by Dr. Arnold Kegel, pelvic floor muscle training has become widely adopted.12

The pelvic floor consists of a group of muscles, resembling a hammock, that support the pelvic viscera. These muscles include the coccygeus and the layers of the levator ani (Figure 1). A weak pelvic floor is one of many risk factors for developing stress urinary incontinence. Like other muscle groups, a weak pelvic floor can be rehabilitated through various techniques, often guided by a physical therapist.

Compared with those who received no treatment, women with stress urinary incontinence who performed pelvic floor muscle training were 8 times more likely to report being cured and 17 times more likely to report cure or improvement.13

To perform a Kegel exercise, a woman consciously contracts her pelvic floor muscles as if stopping the flow of urine.

The Knack maneuver can be used to prevent leakage during anticipated events that increase intra-abdominal pressure. For example, when a cough or sneeze is imminent, patients can preemptively contract their pelvic floor and hold the contraction through the cough or sneeze.

Although many protocols have been compared, no specific pelvic floor exercise strategy has proven superior. A systematic review assessed variations in pelvic floor interventions, exercises, and delivery and found that there was insufficient evidence to make any recommendations about the best approach. However, the benefit was greater with regular supervision during pelvic floor muscle training than with little or no supervision.14

Pelvic floor muscle training strengthens the pelvic floor, which better supports the bladder neck and anatomically compensates for defects in stress urinary incontinence. In urgency urinary incontinence, a strong pelvic floor created by muscle training prevents leaking induced by the involuntary contractions of the detrusor muscle.

Recommendation

The ACP recommends pelvic floor muscle training as first-line treatment for stress urinary incontinence and mixed urinary incontinence, and grades this recommendation as strong with high-quality evidence.

BIOFEEDBACK AND PELVIC STIMULATION

Although pelvic floor exercises are effective in urinary incontinence, 30% of patients perform them incorrectly.15

Biofeedback therapy uses visual, verbal, and acoustic signals to give the patient immediate feedback and a greater awareness of her muscular activity. A commonly used technique employs a vaginal probe to measure and display pressure changes as the patient contracts her levator ani muscles.

Women who received biofeedback in addition to traditional pelvic floor physical therapy had greater improvement in urinary incontinence than those who received pelvic physical therapy alone (risk ratio 0.75, 95% confidence interval 0.66–0.86).16

Pelvic stimulation can be used separately or in conjunction with biofeedback in both urgency and stress urinary incontinence. When pelvic stimulation is used alone, 9 women need to be treated to achieve continence in 1, and 6 women need to be treated to improve continence in 1.16

Traditionally delivered by a pelvic floor physical therapist, pelvic stimulation and biofeedback have also been validated for home use.17,18 Several pelvic stimulation devices have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating stress, urgency, and mixed urinary incontinence. These devices deliver stimulation to the pelvic floor at single or multiple frequencies. Although the mechanisms are not clearly understood, lower frequencies are used to treat urgency incontinence, while higher frequencies are used for stress incontinence. A theory is that higher-frequency stimulation strengthens the pelvic floor in stress urinary incontinence while lower frequency stimulation calms the detrusor muscle in urgency urinary incontinence.

The Apex and Apex M devices are both available over the counter, the former to treat stress urinary incontinence and the latter to treat mixed urinary incontinence, using pelvic stimulation alone. Other available devices, including the InTone and a smaller version, the InTone MV, are available by prescription and combine pelvic stimulation with biofeedback.18

Women who wish to avoid surgery, botulinum toxin injections, and daily oral medications, particularly those who are highly motivated, are ideal candidates for these over-the-counter automatic neuromuscular pelvic exercising devices.

PESSARIES AND OTHER DEVICES

Pessaries are commonly used to treat pelvic organ prolapse but can also be designed to help correct the anatomic defect responsible for stress urinary incontinence. Continence pessaries support the bladder neck so that the urethrovesicular junction is stabilized rather than hypermobile during the increased intra-abdominal pressure that occurs with coughing, sneezing, or physical exertion (Figure 2). In theory, this should decrease leakage.

A systematic review concluded that the value of pessaries in the management of incontinence remains uncertain. However, there are inherent challenges in conducting trials of such devices.19 A pessary needs to be fitted by an appropriately trained healthcare provider. The Ambulatory Treatments for Leakage Associated With Stress Incontinence (ATLAS) trial20 reported that behavioral therapy was more effective than a pessary at 3 months, but the treatments were equivalent at 12 months.

The FDA has approved a disposable, over-the-counter silicone intravaginal device for treating stress urinary incontinence. Patients initially purchase a sizing kit and subsequently insert the nonabsorbent temporary intravaginal bladder supportive device, which is worn for up to 8 hours.

Women may elect to use regular tampons to do the job of a pessary, as they are easy to use and low in cost. No large randomized trials have compared tampons and pessaries, and currently no one device is known to be superior to another.

Overall, these devices are temporizing measures that have few serious adverse effects.

WEIGHT LOSS AND DIETARY CHANGES

Obesity has become a national epidemic, with more than 68% of Americans found to be overweight or obese according to the National Institutes of Health.21

Several studies found obesity to be an independent risk factor for urinary incontinence. As early as 1946, the British Birth Cohort study found that women ages 48 through 54 who were obese earlier in life had a higher risk of urinary incontinence in middle age, and those who were obese by age 20 were more likely to report severe incontinence.22 Likewise, the Nurses’ Health Study showed that women with a body mass index (BMI) more than 30 kg/m2 had 3.1 times the risk of severe incontinence compared with women with a normal BMI. Also, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation and the Leicestershire Medical Research Council (MRC) incontinence study both showed that a higher BMI and weight gain are strongly correlated with urinary incontinence.23,24

Increased intra-abdominal pressure may be the causative mechanism of stress urinary incontinence in obesity. The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that central adiposity correlated with urgency incontinence.25,26

The MRC study was one of the largest to evaluate the effect of diet on urinary symptoms. Consuming a diet dense in vegetables, bread, and chicken was found to reduce the risk of urinary incontinence, while carbonated drinks were associated with a higher risk.25 These studies and others may point to reducing calories, and thus BMI, as a conservative treatment for urinary incontinence.

Newer data show bariatric surgery is associated with a strong reduction in urinary incontinence, demonstrated in a study that followed patients for 3 years after surgery.27 This encouraging result is but one of several positive health outcomes from bariatric surgery.

Recommendation

The ACP recommends both weight loss and exercise for overweight women with urinary incontinence, and grades this as strong with moderate-quality evidence.

DRUG THERAPY

The bladder neck is rich with sympathetic alpha-adrenergic receptors, and the bladder dome is dense with parasympathetic muscarinic receptors and sympathetic beta-adrenergic receptors. When the parasympathetic system is stimulated, the muscarinic receptors are activated, causing detrusor contraction and ultimately bladder emptying.

Agonism of beta-alpha adrenergic receptors and inhibition of parasympathetic receptors are both strategies of drug treatment of urinary incontinence.

Anticholinergic drugs

Anticholinergic medications function by blocking the muscarinic receptor, thereby inhibiting detrusor contraction.

Six oral anticholinergic medications are available: oxybutynin, tolterodine, fesoterodine, solifenacin, trospium, and darifenacin. These drugs have about the same effectiveness in treating urgency urinary incontinence, as measured by achieving continence and improving quality of life.28 Given their similarity in effectiveness, the choice of agent typically relies on the side-effect profile. Extended-release formulations have a more favorable side-effect profile, with fewer cases of dry mouth compared with immediate-release formulations.29

Overall, however, the benefit of these medications is small, with fewer than 200 patients achieving continence per 1,000 treated.28

Other limitations of these medications include their adverse effects and contraindications, and patients’ poor adherence to therapy. The most commonly reported adverse effect is dry mouth, but other common side effects include constipation, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, fatigue, dry eye, and dry skin. Transdermal oxybutynin therapy has been associated with fewer anticholinergic side effects than oral therapy.30

Contraindications to these medications include gastric retention, urinary retention, and angle-closure glaucoma.

Long-term adherence to anticholinergics is low, reported between 14% to 35% after 12 months, with the highest rates of adherence with solifenacin.31 The most commonly cited reason for discontinuation is lack of effect.32

Caution is urged when considering starting anticholinergic medications in older adults because of the central nervous system side effects, including drowsiness, hallucinations, cognitive impairment, and dementia. After 3 weeks, oxybutynin caused a memory decline as measured by delayed recall that was comparable to the decline seen over 10 years in normal aging.33 There is evidence suggesting trospium may cause less cognitive impairment, and therefore may be a better option for older patients.34

Beta-3 adrenoreceptor agonists

Activation of beta-3 adrenergic receptors through the sympathetic nervous system relaxes the detrusor muscle, allowing the bladder to store urine.

Mirabegron is a selective beta-3 adrenoreceptor agonist that effectively relaxes the bladder and increases bladder capacity. It improves continence, treatment satisfaction, and quality of life.35,36 There are fewer reports of dry mouth and constipation with this drug than with the anticholinergics; however, beta-3 adrenoreceptor agonists may be associated with greater risk of hypertension, nasopharyngitis, headache, and urinary tract infection.37

Duloxetine

Duloxetine, an antidepressant, blocks the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine. Consequently, it decreases parasympathetic activity and increases sympathetic and somatic activity in the urinary system.38 While urine is stored, this cascade of neural activity is thought to collectively increase pudendal nerve activity and improve closure of the urethra.

Although duloxetine is approved to treat stress urinary incontinence in Europe, this is an off-label use in the United States.

A meta-analysis39 found that duloxetine improved quality of life in patients with stress urinary incontinence and that subjective cure rates were 10.8% with duloxetine vs 7.7% with placebo (P = .04). However the rate of adverse events is high, with nausea most common. Given its modest benefit and high rate of side effects, physicians may consider starting duloxetine only if there are psychiatric comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, or fibromyalgia.

Recommendations

The ACP recommends against systemic pharmacologic therapy for stress urinary incontinence. For urgency urinary incontinence, pharmacologic therapy is recommended if bladder training fails, and should be individualized based on the patient’s preference and medical comorbidities and the drug’s tolerability, cost, and ease of use.

Hormone therapy

In 2014, the North American Menopause Society recommended replacing the term “vulvovaginal atrophy” with the term genitourinary syndrome of menopause, which better encompasses the postmenopausal changes to the female genital system.40

Estrogen therapy is commercially available in both systemic and local preparations. The effect of exogenous estrogen on urinary incontinence may depend on whether it is given locally or systemically.

A systematic review41 definitively concluded that all commercially prepared local vaginal estrogen preparations can effectively relieve the genitourinary syndrome of menopause, including not only the common complaints of dryness, burning, and irritation but also urinary complaints of frequency, urgency, and urgency urinary incontinence.41 Additionally, the estradiol vaginal ring for vaginal atrophy (Estring) may have dual effects, functioning like an incontinence pessary by supporting the bladder neck while simultaneously providing local estrogen to the atrophied vaginal tissue.

However, in the Women’s Health Initiative,42 continent women who received either systemic estrogen therapy alone or systemic estrogen combined with progestin actually had a higher risk of developing urinary incontinence, and those already experiencing incontinence developed a worsening of their symptoms on systemic hormone therapy. The mechanism by which systemic hormone therapy causes urinary incontinence is unclear; however, previous studies showed that hormone therapy leads to a reduction in periurethral collagen and increased bladder contractility.43,44

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Half of women with symptomatic urinary incontinence never report their symptoms.

- Bladder training is recommended for urgency incontinence and pelvic floor muscle training for stress incontinence.

- Thirty percent of women perform pelvic floor exercises incorrectly.

- Devices can be considered, including automatic pelvic exercise devices for stress and urgency incontinence and incontinence pessaries and disposable intravaginal bladder support devices for stress incontinence.

- Higher BMIs are strongly correlated with urinary incontinence.

- Anticholinergic medications are recommended for urgency but not stress incontinence.

- Vaginal estrogen cream may help with symptoms of urinary urgency, recurrent bladder infections, and nocturia in addition to incontinence.

Urinary incontinence can lead to a cascade of symptomatic burden on the patient, causing distress, embarrassment, and suffering.

See related patient information

Traditionally, incontinence has been treated by surgeons, and surgery remains an option. However, more patients are now being managed by medical clinicians, who can offer a number of newer therapies. Ideally, a medical physician can initiate the evaluation and treatment and even effectively cure some forms of urinary incontinence.

In 2014, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published recommendations on the medical treatment of urinary incontinence in women (Table 1).1

This review describes the medical management of urinary incontinence in women, emphasizing the ACP recommendations1 and newer over-the-counter options.

COMMON AND UNDERREPORTED

Many women erroneously believe that urinary incontinence is an inevitable consequence of aging and allow it to lessen their quality of life without seeking medical attention.

Indeed, it is common. The 2005–2006 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey2 found the prevalence of urinary incontinence in US women to be 15.7%. The prevalence increases with age from 6.9% in women ages 20 through 29 to 31.7% in those age 80 and older. A separate analysis of the same data found that 25.0% of women age 20 and older had 1 or more pelvic floor disorders.3 Some estimates are even higher. Wu et al4 reported a prevalence of urinary incontinence of 51.1% in women ages 31 through 54.

Too few of these women are identified and treated, for many reasons, including embarrassment and inadequate screening. Half of women with urinary incontinence do not report their symptoms because of humiliation or anxiety.5

The burden of urinary incontinence extends beyond the individual and into society. The total cost of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence in the United States was estimated to be $65.9 billion in 2007 and is projected to reach $82.6 billion in 2020.6

THREE TYPES

There are 3 types of urinary incontinence: stress, urgency, and mixed.

Stress urinary incontinence is involuntary loss of urine associated with physical exertion or increased abdominal pressure, eg, with coughing or sneezing.

Urgency urinary incontinence is involuntary loss of urine associated with the sudden need to void. Many patients experience these symptoms simultaneously, making the distinction difficult.

Mixed urinary incontinence is loss of urine with both urgency and increased abdominal pressure or physical exertion.

Overactive bladder, a related problem, is defined as urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence, in the absence of a urinary tract infection or other obvious disease.7

Nongenitourinary causes such as neurologic disorders or even malignancy can present with urinary incontinence, and thus it is critical to perform a thorough initial evaluation.

A 2014 study revealed that by age 80, 20% of women may need to undergo surgery for stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. This statistic should motivate healthcare providers to focus on prevention and offer conservative medical management for these conditions first.8

QUESTIONS TO ASK

When doing a pelvic examination, once could inquire about urinary incontinence with questions such as:

Do you leak urine when you cough, sneeze, laugh, or jump or during sexual climax?

Do you have to get up more than once at night to urinate?

Do you feel the urge to urinate frequently?

BEHAVIORAL MODIFICATION AND BLADDER TRAINING

Bladder training is a conservative behavioral treatment for urinary incontinence that primary care physicians can teach. It is primarily used for urgency urinary incontinence but can also be useful in stress urinary incontinence.

After completing a bladder diary and gaining awareness of their daily voiding patterns, patients can learn scheduled voiding to train the bladder, gradually extending the urges to longer intervals.

Clinicians should instruct patients on how to train the bladder, using methods first described by Wyman and Fantl.9 (See Training the bladder.)

There is evidence that bladder training improves urinary incontinence compared with usual care.10,11

The ACP recommends bladder training for women who have urgency urinary incontinence, but grades this recommendation as weak with low-quality evidence.

PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING

Introduced in 1948 by Dr. Arnold Kegel, pelvic floor muscle training has become widely adopted.12