User login

Drive, chip, and putt your way to osteoarthritis relief

Taking a swing against arthritis

Osteoarthritis is a tough disease to manage. Exercise helps ease the stiffness and pain of the joints, but at the same time, the disease makes it difficult to do that beneficial exercise. Even a relatively simple activity like jogging can hurt more than it helps. If only there were a low-impact exercise that was incredibly popular among the generally older population who are likely to have arthritis.

We love a good golf study here at LOTME, and a group of Australian and U.K. researchers have provided. Osteoarthritis affects 2 million people in the land down under, making it the most common source of disability there. In that population, only 64% reported their physical health to be good, very good, or excellent. Among the 459 golfers with OA that the study authors surveyed, however, the percentage reporting good health rose to more than 90%.

A similar story emerged when they looked at mental health. Nearly a quarter of nongolfers with OA reported high or very high levels of psychological distress, compared with just 8% of golfers. This pattern of improved physical and mental health remained when the researchers looked at the general, non-OA population.

This isn’t the first time golf’s been connected with improved health, and previous studies have shown golf to reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, among other things. Just walking one 18-hole round significantly exceeds the CDC’s recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Go out multiple times a week – leaving the cart and beer at home, American golfers – and you’ll be fit for a lifetime.

The golfers on our staff, however, are still waiting for those mental health benefits to kick in. Because when we’re adding up our scorecard after that string of four double bogeys to end the round, we’re most definitely thinking: “Yes, this sport is reducing my psychological distress. I am having fun right now.”

Battle of the sexes’ intestines

There are, we’re sure you’ve noticed, some differences between males and females. Females, for one thing, have longer small intestines than males. Everybody knows that, right? You didn’t know? Really? … Really?

Well, then, we’re guessing you haven’t read “Hidden diversity: Comparative functional morphology of humans and other species” by Erin A. McKenney, PhD, of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and associates, which just appeared in PeerJ. We couldn’t put it down, even in the shower – a real page-turner/scroller. (It’s a great way to clean a phone, for those who also like to scroll, text, or talk on the toilet.)

The researchers got out their rulers, calipers, and string and took many measurements of the digestive systems of 45 human cadavers (21 female and 24 male), which were compared with data from 10 rats, 10 pigs, and 10 bullfrogs, which had been collected (the measurements, not the animals) by undergraduate students enrolled in a comparative anatomy laboratory course at the university.

There was little intestinal-length variation among the four-legged subjects, but when it comes to humans, females have “consistently and significantly longer small intestines than males,” the investigators noted.

The women’s small intestines, almost 14 feet long on average, were about a foot longer than the men’s, which suggests that women are better able to extract nutrients from food and “supports the canalization hypothesis, which posits that women are better able to survive during periods of stress,” coauthor Amanda Hale said in a written statement from the school. The way to a man’s heart may be through his stomach, but the way to a woman’s heart is through her duodenum, it seems.

Fascinating stuff, to be sure, but the thing that really caught our eye in the PeerJ article was the authors’ suggestion “that organs behave independently of one another, both within and across species.” Organs behaving independently? A somewhat ominous concept, no doubt, but it does explain a lot of the sounds we hear coming from our guts, which can get pretty frightening, especially on chili night.

Dog walking is dangerous business

Yes, you did read that right. A lot of strange things can send you to the emergency department. Go ahead and add dog walking onto that list.

Investigators from Johns Hopkins University estimate that over 422,000 adults presented to U.S. emergency departments with leash-dependent dog walking-related injuries between 2001 and 2020.

With almost 53% of U.S. households owning at least one dog in 2021-2022 in the wake of the COVID pet boom, this kind of occurrence is becoming more common than you think. The annual number of dog-walking injuries more than quadrupled from 7,300 to 32,000 over the course of the study, and the researchers link that spike to the promotion of dog walking for fitness, along with the boost of ownership itself.

The most common injuries listed in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database were finger fracture, traumatic brain injury, and shoulder sprain or strain. These mostly involved falls from being pulled, tripped, or tangled up in the leash while walking. For those aged 65 years and older, traumatic brain injury and hip fracture were the most common.

Women were 50% more likely to sustain a fracture than were men, and dog owners aged 65 and older were three times as likely to fall, twice as likely to get a fracture, and 60% more likely to have brain injury than were younger people. Now, that’s not to say younger people don’t also get hurt. After all, dogs aren’t ageists. The researchers have that data but it’s coming out later.

Meanwhile, the pitfalls involved with just trying to get our daily steps in while letting Muffin do her business have us on the lookout for random squirrels.

Taking a swing against arthritis

Osteoarthritis is a tough disease to manage. Exercise helps ease the stiffness and pain of the joints, but at the same time, the disease makes it difficult to do that beneficial exercise. Even a relatively simple activity like jogging can hurt more than it helps. If only there were a low-impact exercise that was incredibly popular among the generally older population who are likely to have arthritis.

We love a good golf study here at LOTME, and a group of Australian and U.K. researchers have provided. Osteoarthritis affects 2 million people in the land down under, making it the most common source of disability there. In that population, only 64% reported their physical health to be good, very good, or excellent. Among the 459 golfers with OA that the study authors surveyed, however, the percentage reporting good health rose to more than 90%.

A similar story emerged when they looked at mental health. Nearly a quarter of nongolfers with OA reported high or very high levels of psychological distress, compared with just 8% of golfers. This pattern of improved physical and mental health remained when the researchers looked at the general, non-OA population.

This isn’t the first time golf’s been connected with improved health, and previous studies have shown golf to reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, among other things. Just walking one 18-hole round significantly exceeds the CDC’s recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Go out multiple times a week – leaving the cart and beer at home, American golfers – and you’ll be fit for a lifetime.

The golfers on our staff, however, are still waiting for those mental health benefits to kick in. Because when we’re adding up our scorecard after that string of four double bogeys to end the round, we’re most definitely thinking: “Yes, this sport is reducing my psychological distress. I am having fun right now.”

Battle of the sexes’ intestines

There are, we’re sure you’ve noticed, some differences between males and females. Females, for one thing, have longer small intestines than males. Everybody knows that, right? You didn’t know? Really? … Really?

Well, then, we’re guessing you haven’t read “Hidden diversity: Comparative functional morphology of humans and other species” by Erin A. McKenney, PhD, of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and associates, which just appeared in PeerJ. We couldn’t put it down, even in the shower – a real page-turner/scroller. (It’s a great way to clean a phone, for those who also like to scroll, text, or talk on the toilet.)

The researchers got out their rulers, calipers, and string and took many measurements of the digestive systems of 45 human cadavers (21 female and 24 male), which were compared with data from 10 rats, 10 pigs, and 10 bullfrogs, which had been collected (the measurements, not the animals) by undergraduate students enrolled in a comparative anatomy laboratory course at the university.

There was little intestinal-length variation among the four-legged subjects, but when it comes to humans, females have “consistently and significantly longer small intestines than males,” the investigators noted.

The women’s small intestines, almost 14 feet long on average, were about a foot longer than the men’s, which suggests that women are better able to extract nutrients from food and “supports the canalization hypothesis, which posits that women are better able to survive during periods of stress,” coauthor Amanda Hale said in a written statement from the school. The way to a man’s heart may be through his stomach, but the way to a woman’s heart is through her duodenum, it seems.

Fascinating stuff, to be sure, but the thing that really caught our eye in the PeerJ article was the authors’ suggestion “that organs behave independently of one another, both within and across species.” Organs behaving independently? A somewhat ominous concept, no doubt, but it does explain a lot of the sounds we hear coming from our guts, which can get pretty frightening, especially on chili night.

Dog walking is dangerous business

Yes, you did read that right. A lot of strange things can send you to the emergency department. Go ahead and add dog walking onto that list.

Investigators from Johns Hopkins University estimate that over 422,000 adults presented to U.S. emergency departments with leash-dependent dog walking-related injuries between 2001 and 2020.

With almost 53% of U.S. households owning at least one dog in 2021-2022 in the wake of the COVID pet boom, this kind of occurrence is becoming more common than you think. The annual number of dog-walking injuries more than quadrupled from 7,300 to 32,000 over the course of the study, and the researchers link that spike to the promotion of dog walking for fitness, along with the boost of ownership itself.

The most common injuries listed in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database were finger fracture, traumatic brain injury, and shoulder sprain or strain. These mostly involved falls from being pulled, tripped, or tangled up in the leash while walking. For those aged 65 years and older, traumatic brain injury and hip fracture were the most common.

Women were 50% more likely to sustain a fracture than were men, and dog owners aged 65 and older were three times as likely to fall, twice as likely to get a fracture, and 60% more likely to have brain injury than were younger people. Now, that’s not to say younger people don’t also get hurt. After all, dogs aren’t ageists. The researchers have that data but it’s coming out later.

Meanwhile, the pitfalls involved with just trying to get our daily steps in while letting Muffin do her business have us on the lookout for random squirrels.

Taking a swing against arthritis

Osteoarthritis is a tough disease to manage. Exercise helps ease the stiffness and pain of the joints, but at the same time, the disease makes it difficult to do that beneficial exercise. Even a relatively simple activity like jogging can hurt more than it helps. If only there were a low-impact exercise that was incredibly popular among the generally older population who are likely to have arthritis.

We love a good golf study here at LOTME, and a group of Australian and U.K. researchers have provided. Osteoarthritis affects 2 million people in the land down under, making it the most common source of disability there. In that population, only 64% reported their physical health to be good, very good, or excellent. Among the 459 golfers with OA that the study authors surveyed, however, the percentage reporting good health rose to more than 90%.

A similar story emerged when they looked at mental health. Nearly a quarter of nongolfers with OA reported high or very high levels of psychological distress, compared with just 8% of golfers. This pattern of improved physical and mental health remained when the researchers looked at the general, non-OA population.

This isn’t the first time golf’s been connected with improved health, and previous studies have shown golf to reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, among other things. Just walking one 18-hole round significantly exceeds the CDC’s recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Go out multiple times a week – leaving the cart and beer at home, American golfers – and you’ll be fit for a lifetime.

The golfers on our staff, however, are still waiting for those mental health benefits to kick in. Because when we’re adding up our scorecard after that string of four double bogeys to end the round, we’re most definitely thinking: “Yes, this sport is reducing my psychological distress. I am having fun right now.”

Battle of the sexes’ intestines

There are, we’re sure you’ve noticed, some differences between males and females. Females, for one thing, have longer small intestines than males. Everybody knows that, right? You didn’t know? Really? … Really?

Well, then, we’re guessing you haven’t read “Hidden diversity: Comparative functional morphology of humans and other species” by Erin A. McKenney, PhD, of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and associates, which just appeared in PeerJ. We couldn’t put it down, even in the shower – a real page-turner/scroller. (It’s a great way to clean a phone, for those who also like to scroll, text, or talk on the toilet.)

The researchers got out their rulers, calipers, and string and took many measurements of the digestive systems of 45 human cadavers (21 female and 24 male), which were compared with data from 10 rats, 10 pigs, and 10 bullfrogs, which had been collected (the measurements, not the animals) by undergraduate students enrolled in a comparative anatomy laboratory course at the university.

There was little intestinal-length variation among the four-legged subjects, but when it comes to humans, females have “consistently and significantly longer small intestines than males,” the investigators noted.

The women’s small intestines, almost 14 feet long on average, were about a foot longer than the men’s, which suggests that women are better able to extract nutrients from food and “supports the canalization hypothesis, which posits that women are better able to survive during periods of stress,” coauthor Amanda Hale said in a written statement from the school. The way to a man’s heart may be through his stomach, but the way to a woman’s heart is through her duodenum, it seems.

Fascinating stuff, to be sure, but the thing that really caught our eye in the PeerJ article was the authors’ suggestion “that organs behave independently of one another, both within and across species.” Organs behaving independently? A somewhat ominous concept, no doubt, but it does explain a lot of the sounds we hear coming from our guts, which can get pretty frightening, especially on chili night.

Dog walking is dangerous business

Yes, you did read that right. A lot of strange things can send you to the emergency department. Go ahead and add dog walking onto that list.

Investigators from Johns Hopkins University estimate that over 422,000 adults presented to U.S. emergency departments with leash-dependent dog walking-related injuries between 2001 and 2020.

With almost 53% of U.S. households owning at least one dog in 2021-2022 in the wake of the COVID pet boom, this kind of occurrence is becoming more common than you think. The annual number of dog-walking injuries more than quadrupled from 7,300 to 32,000 over the course of the study, and the researchers link that spike to the promotion of dog walking for fitness, along with the boost of ownership itself.

The most common injuries listed in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database were finger fracture, traumatic brain injury, and shoulder sprain or strain. These mostly involved falls from being pulled, tripped, or tangled up in the leash while walking. For those aged 65 years and older, traumatic brain injury and hip fracture were the most common.

Women were 50% more likely to sustain a fracture than were men, and dog owners aged 65 and older were three times as likely to fall, twice as likely to get a fracture, and 60% more likely to have brain injury than were younger people. Now, that’s not to say younger people don’t also get hurt. After all, dogs aren’t ageists. The researchers have that data but it’s coming out later.

Meanwhile, the pitfalls involved with just trying to get our daily steps in while letting Muffin do her business have us on the lookout for random squirrels.

FDA gives fast-track approval to new ALS drug

the debilitating and deadly disease for which there is no cure.

Most people with ALS die within 3-5 years of when symptoms appear, usually of respiratory failure.

The newly approved drug, called Qalsody, is made by the Swiss company Biogen. The FDA fast-tracked the approval based on early trial results. The agency said in a news release that its decision was based on the demonstrated ability of the drug to reduce a protein in the blood that is a sign of degeneration of brain and nerve cells.

While the drug was shown to impact the chemical process in the body linked to degeneration, there was no significant change in people’s symptoms during the first 28 weeks that they took the drug, Biogen said in a news release. But the company noted that some patients did see improved functioning after starting treatment.

“I have observed the positive impact Qalsody has on slowing the progression of ALS in people with SOD1 mutations,” Timothy M. Miller, MD, PhD, researcher and codirector of the ALS Center at Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement released by Biogen. “The FDA’s approval of Qalsody gives me hope that people living with this rare form of ALS could experience a reduction in decline in strength, clinical function, and respiratory function.”

Qalsody is given to people via a spinal injection, with an initial course of three injections every 2 weeks. People then get the injection once every 28 days.

The new treatment is approved only for people with a rare kind of ALS called SOD1-ALS, which is known for a genetic mutation. While ALS affects up to 32,000 people in the United States, just 2% of people with ALS have the SOD1 gene mutation. The FDA says the number of people in the United States who could use Qalsody is about 500.

In trials, 147 people received either Qalsody or a placebo, and the treatment significantly reduced the level of a protein in people’s blood that is associated with the loss of control of voluntary muscles.

Because Qalsody received a fast-track approval from the FDA, it must still provide more research data in the future, including from a trial examining how the drug affects people who carry the SOD1 gene but do not yet show symptoms of ALS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the debilitating and deadly disease for which there is no cure.

Most people with ALS die within 3-5 years of when symptoms appear, usually of respiratory failure.

The newly approved drug, called Qalsody, is made by the Swiss company Biogen. The FDA fast-tracked the approval based on early trial results. The agency said in a news release that its decision was based on the demonstrated ability of the drug to reduce a protein in the blood that is a sign of degeneration of brain and nerve cells.

While the drug was shown to impact the chemical process in the body linked to degeneration, there was no significant change in people’s symptoms during the first 28 weeks that they took the drug, Biogen said in a news release. But the company noted that some patients did see improved functioning after starting treatment.

“I have observed the positive impact Qalsody has on slowing the progression of ALS in people with SOD1 mutations,” Timothy M. Miller, MD, PhD, researcher and codirector of the ALS Center at Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement released by Biogen. “The FDA’s approval of Qalsody gives me hope that people living with this rare form of ALS could experience a reduction in decline in strength, clinical function, and respiratory function.”

Qalsody is given to people via a spinal injection, with an initial course of three injections every 2 weeks. People then get the injection once every 28 days.

The new treatment is approved only for people with a rare kind of ALS called SOD1-ALS, which is known for a genetic mutation. While ALS affects up to 32,000 people in the United States, just 2% of people with ALS have the SOD1 gene mutation. The FDA says the number of people in the United States who could use Qalsody is about 500.

In trials, 147 people received either Qalsody or a placebo, and the treatment significantly reduced the level of a protein in people’s blood that is associated with the loss of control of voluntary muscles.

Because Qalsody received a fast-track approval from the FDA, it must still provide more research data in the future, including from a trial examining how the drug affects people who carry the SOD1 gene but do not yet show symptoms of ALS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the debilitating and deadly disease for which there is no cure.

Most people with ALS die within 3-5 years of when symptoms appear, usually of respiratory failure.

The newly approved drug, called Qalsody, is made by the Swiss company Biogen. The FDA fast-tracked the approval based on early trial results. The agency said in a news release that its decision was based on the demonstrated ability of the drug to reduce a protein in the blood that is a sign of degeneration of brain and nerve cells.

While the drug was shown to impact the chemical process in the body linked to degeneration, there was no significant change in people’s symptoms during the first 28 weeks that they took the drug, Biogen said in a news release. But the company noted that some patients did see improved functioning after starting treatment.

“I have observed the positive impact Qalsody has on slowing the progression of ALS in people with SOD1 mutations,” Timothy M. Miller, MD, PhD, researcher and codirector of the ALS Center at Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement released by Biogen. “The FDA’s approval of Qalsody gives me hope that people living with this rare form of ALS could experience a reduction in decline in strength, clinical function, and respiratory function.”

Qalsody is given to people via a spinal injection, with an initial course of three injections every 2 weeks. People then get the injection once every 28 days.

The new treatment is approved only for people with a rare kind of ALS called SOD1-ALS, which is known for a genetic mutation. While ALS affects up to 32,000 people in the United States, just 2% of people with ALS have the SOD1 gene mutation. The FDA says the number of people in the United States who could use Qalsody is about 500.

In trials, 147 people received either Qalsody or a placebo, and the treatment significantly reduced the level of a protein in people’s blood that is associated with the loss of control of voluntary muscles.

Because Qalsody received a fast-track approval from the FDA, it must still provide more research data in the future, including from a trial examining how the drug affects people who carry the SOD1 gene but do not yet show symptoms of ALS.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

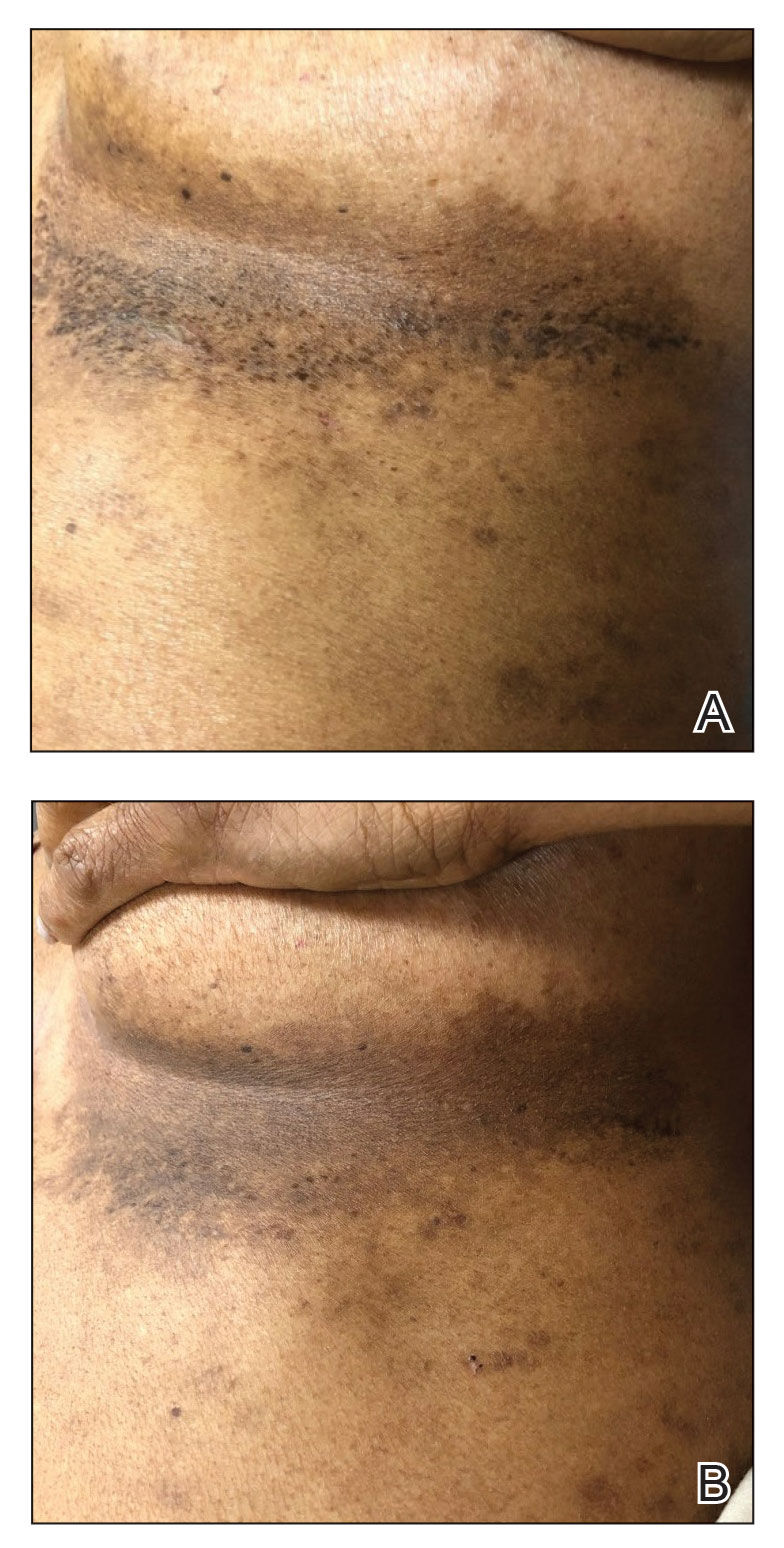

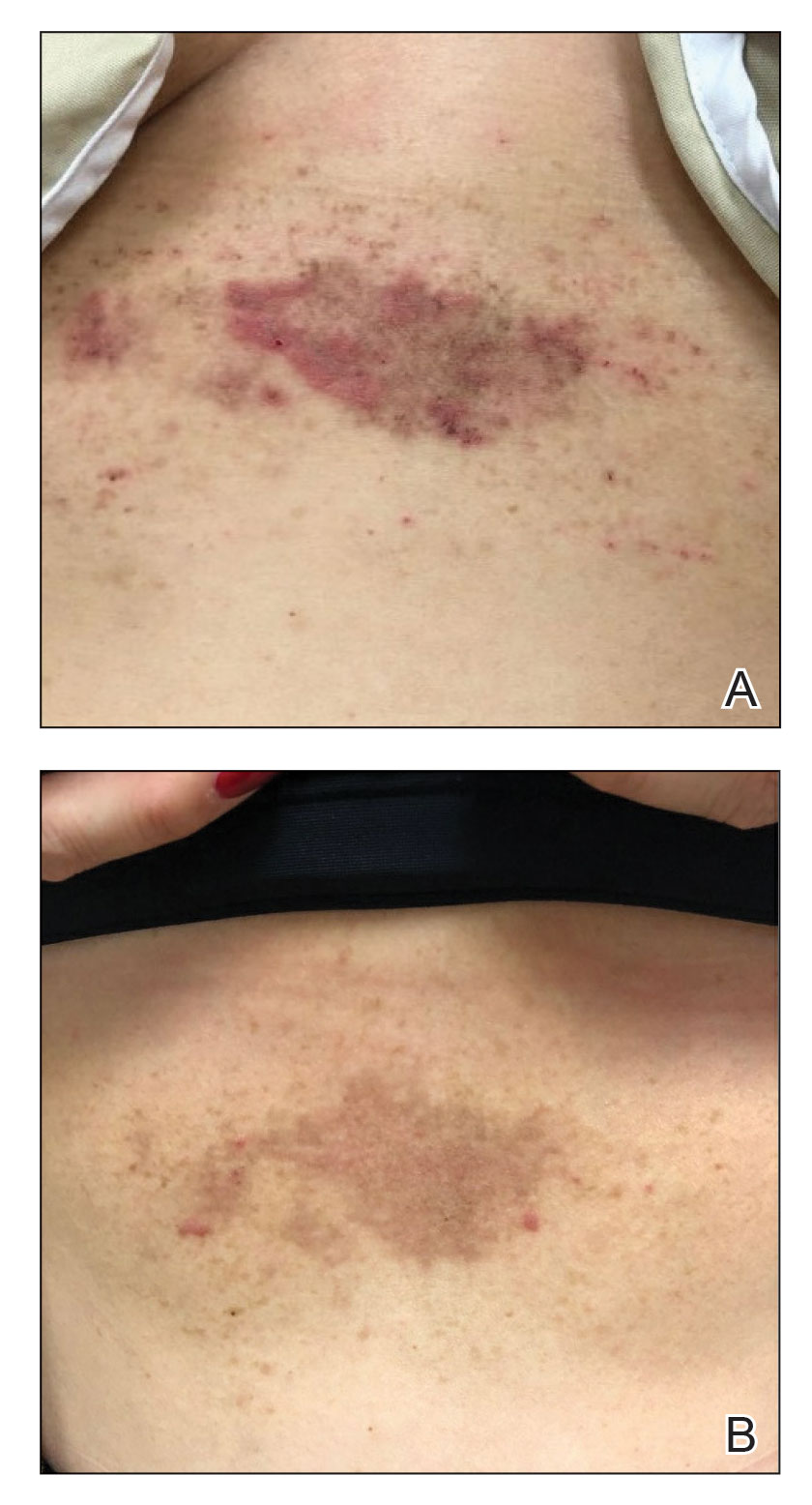

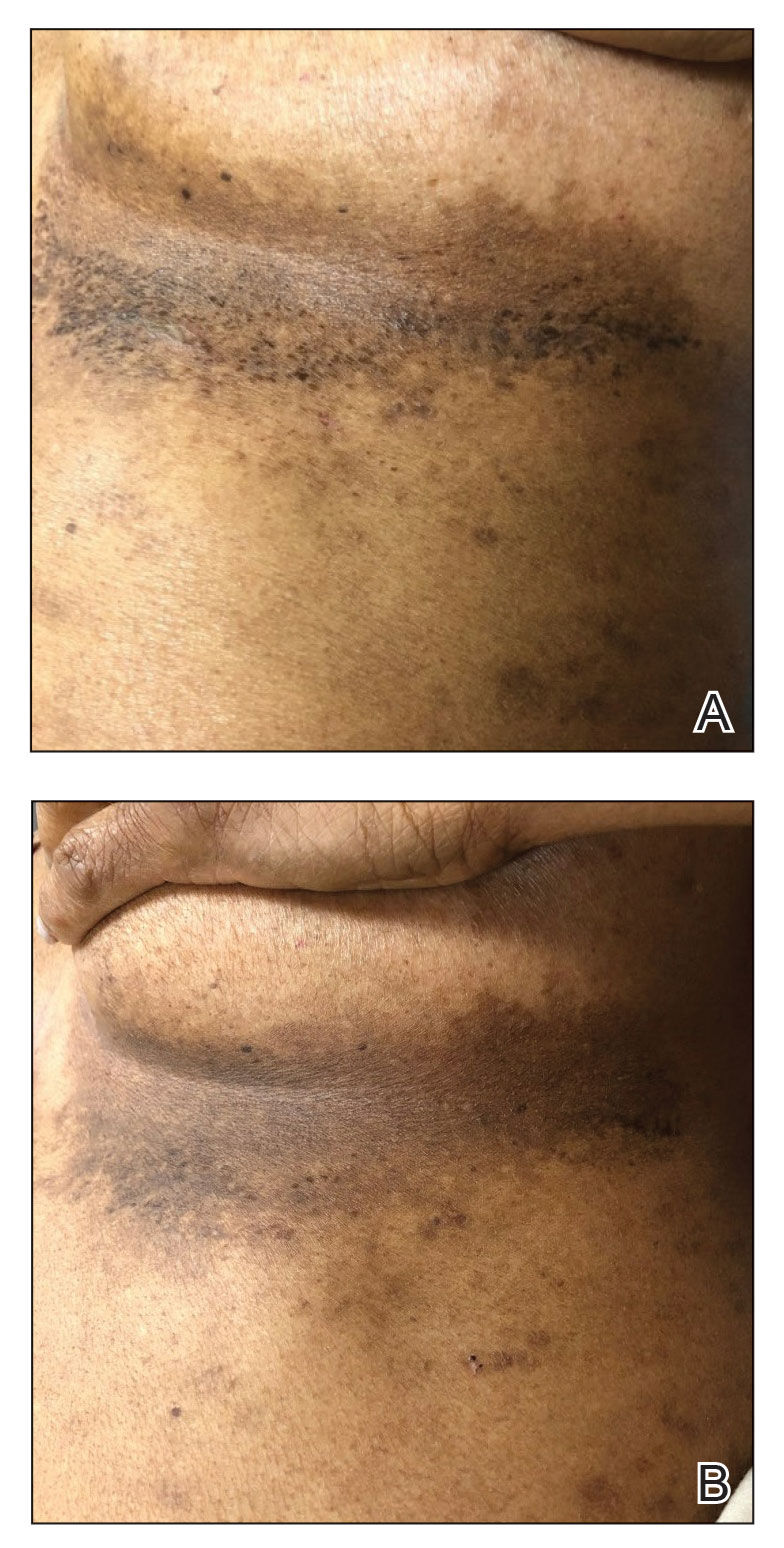

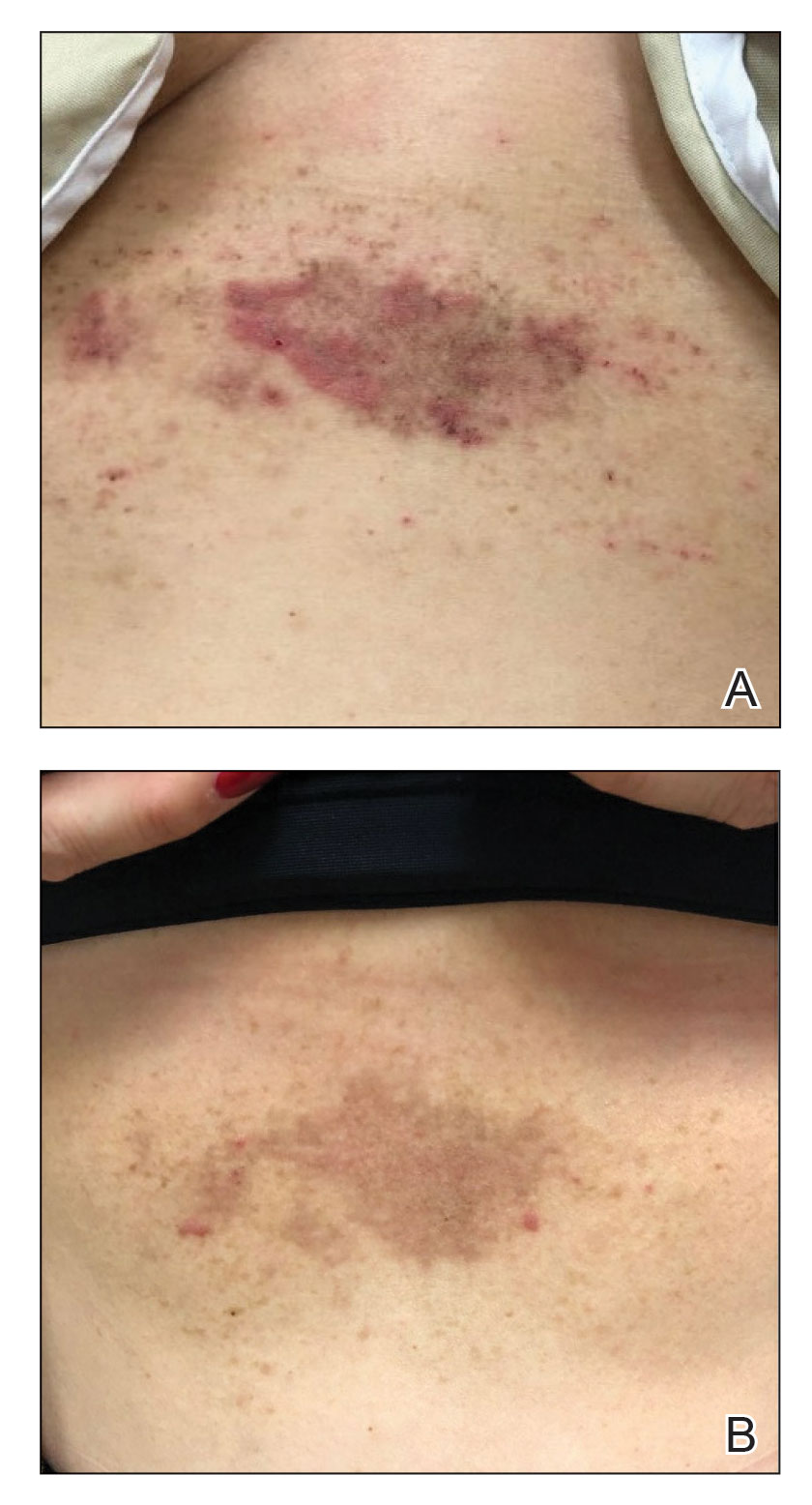

Branding tattoo removal helps sex trafficking survivor close door on painful past

PHOENIX – When Kathy Givens walked onstage during a plenary session at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery to reflect on her 9-month ordeal being sex trafficked in Texas more than 20 years ago, you could hear a pin drop.

“One of the scariest things about the life of sex trafficking is not knowing who’s going to be on the other side,” said Ms. Givens, who now lives in Houston. “There was some violence. There were some horrible things that happened. But you know what was really scary? When I got out. People may ask, ‘How’s that so? You escaped your trafficker. The past is behind you. Why were you afraid?’ I was afraid because I didn’t know that I had community. I didn’t know that community or that society would care about someone like me.”

She said that she found herself immobilized by fear of being shamed in society and labeled a sex trafficking victim, and wondered if she could overcome that fear and if anyone would view her as human again. Once free from her trafficker, she began a “healing journey,” which included getting married, raising four children, and re-enrolling in college with hopes of becoming a social worker. In 2020, she and her husband founded Twelve 11 Partners, an organization committed to supporting human trafficking survivors.

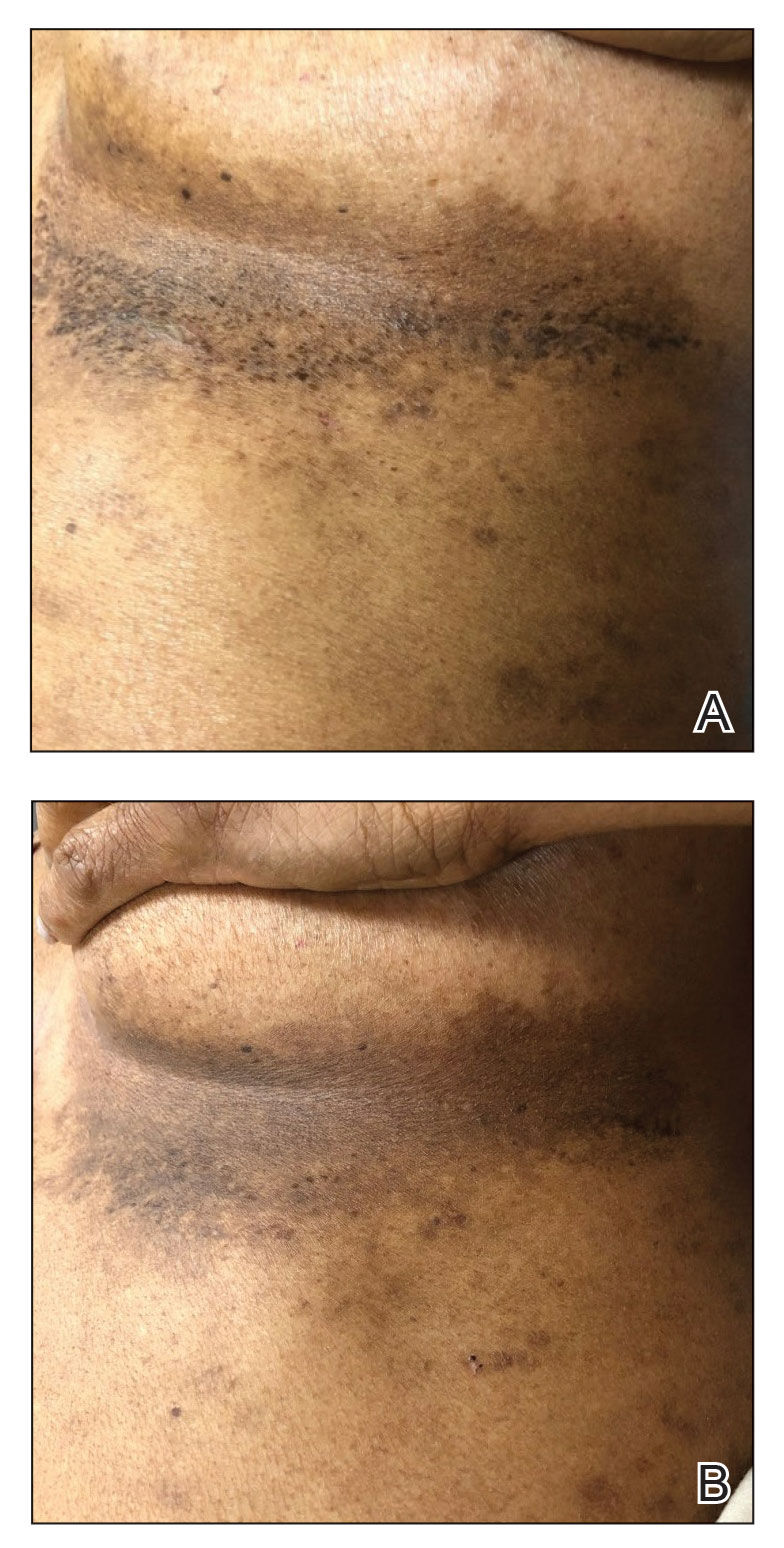

“I was working in the anti-trafficking field helping other survivors ... who have experienced this horrific crime,” she said. “I thought I was on my way.” But one “stain” from her sex trafficking past remained: The name of her trafficker was tattooed on her skin, “a reminder of what I’d gone through.”

Ms. Givens was eventually introduced to Paul M. Friedman, MD, the current ASLMS president and one of the that was formed in 2022. According to a survey that Dr. Friedman and colleagues presented at the 2022 annual ASLMS conference, an estimated 1 in 2 sex trafficking survivors have branding tattoos, and at least 1,000 survivors a year could benefit from removal of those tattoos.

“To date, 87 physicians in the U.S. and one in Canada have stepped forward to volunteer their services to be part of this program,” Dr. Friedman, who directs the Dermatology and Laser Surgery Center in Houston, said at this year’s meeting. “My goal is to double this number by the next annual conference,” he added, noting that trauma-informed training is part of the program, “to support the survivor experience during the treatment process.”

ASLMS is also working on this issue in partnership with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Ad Hoc Task Force on Dermatological Resources for the Intervention and Prevention of Human Trafficking, which is headed by Boston dermatologist Shadi Kourosh, MD.

“Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to aid in efforts to assist those experiences in trafficking with our training to recognize and diagnose relevant signs on the skin and to assist patients with certain aspects of care and recovery including the treatment of the disease of scars and tattoos,” Dr. Friedman said. “Ultimately, we hope to create a database together to improve recognition of branding tattoos to aid in identifying sex trafficking victims.”

Ms. Givens, who sits on the U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking, said that she was able to truly close the door on her sex trafficking past thanks to the tattoo removal Dr. Friedman performed as part of New Beginnings. “It means the world to me to know that I can now be an advocate for other individuals who have experienced human trafficking,” she told meeting attendees.

“Again, one of the scariest things is not knowing that you have community. I was scared of losing hope, but I’m standing here today. I have all the hope that I need. You have the power to change lives.”

PHOENIX – When Kathy Givens walked onstage during a plenary session at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery to reflect on her 9-month ordeal being sex trafficked in Texas more than 20 years ago, you could hear a pin drop.

“One of the scariest things about the life of sex trafficking is not knowing who’s going to be on the other side,” said Ms. Givens, who now lives in Houston. “There was some violence. There were some horrible things that happened. But you know what was really scary? When I got out. People may ask, ‘How’s that so? You escaped your trafficker. The past is behind you. Why were you afraid?’ I was afraid because I didn’t know that I had community. I didn’t know that community or that society would care about someone like me.”

She said that she found herself immobilized by fear of being shamed in society and labeled a sex trafficking victim, and wondered if she could overcome that fear and if anyone would view her as human again. Once free from her trafficker, she began a “healing journey,” which included getting married, raising four children, and re-enrolling in college with hopes of becoming a social worker. In 2020, she and her husband founded Twelve 11 Partners, an organization committed to supporting human trafficking survivors.

“I was working in the anti-trafficking field helping other survivors ... who have experienced this horrific crime,” she said. “I thought I was on my way.” But one “stain” from her sex trafficking past remained: The name of her trafficker was tattooed on her skin, “a reminder of what I’d gone through.”

Ms. Givens was eventually introduced to Paul M. Friedman, MD, the current ASLMS president and one of the that was formed in 2022. According to a survey that Dr. Friedman and colleagues presented at the 2022 annual ASLMS conference, an estimated 1 in 2 sex trafficking survivors have branding tattoos, and at least 1,000 survivors a year could benefit from removal of those tattoos.

“To date, 87 physicians in the U.S. and one in Canada have stepped forward to volunteer their services to be part of this program,” Dr. Friedman, who directs the Dermatology and Laser Surgery Center in Houston, said at this year’s meeting. “My goal is to double this number by the next annual conference,” he added, noting that trauma-informed training is part of the program, “to support the survivor experience during the treatment process.”

ASLMS is also working on this issue in partnership with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Ad Hoc Task Force on Dermatological Resources for the Intervention and Prevention of Human Trafficking, which is headed by Boston dermatologist Shadi Kourosh, MD.

“Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to aid in efforts to assist those experiences in trafficking with our training to recognize and diagnose relevant signs on the skin and to assist patients with certain aspects of care and recovery including the treatment of the disease of scars and tattoos,” Dr. Friedman said. “Ultimately, we hope to create a database together to improve recognition of branding tattoos to aid in identifying sex trafficking victims.”

Ms. Givens, who sits on the U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking, said that she was able to truly close the door on her sex trafficking past thanks to the tattoo removal Dr. Friedman performed as part of New Beginnings. “It means the world to me to know that I can now be an advocate for other individuals who have experienced human trafficking,” she told meeting attendees.

“Again, one of the scariest things is not knowing that you have community. I was scared of losing hope, but I’m standing here today. I have all the hope that I need. You have the power to change lives.”

PHOENIX – When Kathy Givens walked onstage during a plenary session at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery to reflect on her 9-month ordeal being sex trafficked in Texas more than 20 years ago, you could hear a pin drop.

“One of the scariest things about the life of sex trafficking is not knowing who’s going to be on the other side,” said Ms. Givens, who now lives in Houston. “There was some violence. There were some horrible things that happened. But you know what was really scary? When I got out. People may ask, ‘How’s that so? You escaped your trafficker. The past is behind you. Why were you afraid?’ I was afraid because I didn’t know that I had community. I didn’t know that community or that society would care about someone like me.”

She said that she found herself immobilized by fear of being shamed in society and labeled a sex trafficking victim, and wondered if she could overcome that fear and if anyone would view her as human again. Once free from her trafficker, she began a “healing journey,” which included getting married, raising four children, and re-enrolling in college with hopes of becoming a social worker. In 2020, she and her husband founded Twelve 11 Partners, an organization committed to supporting human trafficking survivors.

“I was working in the anti-trafficking field helping other survivors ... who have experienced this horrific crime,” she said. “I thought I was on my way.” But one “stain” from her sex trafficking past remained: The name of her trafficker was tattooed on her skin, “a reminder of what I’d gone through.”

Ms. Givens was eventually introduced to Paul M. Friedman, MD, the current ASLMS president and one of the that was formed in 2022. According to a survey that Dr. Friedman and colleagues presented at the 2022 annual ASLMS conference, an estimated 1 in 2 sex trafficking survivors have branding tattoos, and at least 1,000 survivors a year could benefit from removal of those tattoos.

“To date, 87 physicians in the U.S. and one in Canada have stepped forward to volunteer their services to be part of this program,” Dr. Friedman, who directs the Dermatology and Laser Surgery Center in Houston, said at this year’s meeting. “My goal is to double this number by the next annual conference,” he added, noting that trauma-informed training is part of the program, “to support the survivor experience during the treatment process.”

ASLMS is also working on this issue in partnership with the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Ad Hoc Task Force on Dermatological Resources for the Intervention and Prevention of Human Trafficking, which is headed by Boston dermatologist Shadi Kourosh, MD.

“Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to aid in efforts to assist those experiences in trafficking with our training to recognize and diagnose relevant signs on the skin and to assist patients with certain aspects of care and recovery including the treatment of the disease of scars and tattoos,” Dr. Friedman said. “Ultimately, we hope to create a database together to improve recognition of branding tattoos to aid in identifying sex trafficking victims.”

Ms. Givens, who sits on the U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking, said that she was able to truly close the door on her sex trafficking past thanks to the tattoo removal Dr. Friedman performed as part of New Beginnings. “It means the world to me to know that I can now be an advocate for other individuals who have experienced human trafficking,” she told meeting attendees.

“Again, one of the scariest things is not knowing that you have community. I was scared of losing hope, but I’m standing here today. I have all the hope that I need. You have the power to change lives.”

AT ASLMS 2023

Repeated CTs in childhood linked with increased cancer risk

In a population-based case-control study that included more than 85,000 participants, researchers found a ninefold increased risk of intracranial tumors among children who received four or more CT scans.

The results “indicate that judicious CT usage and radiation-reducing techniques should be advocated,” Yu-Hsuan Joni Shao, PhD, professor of biomedical informatics at Taipei (Taiwan) Medical University, and colleagues wrote.

The study was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Dose-response relationship

The investigators used the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan to identify 7,807 patients under age 25 years with intracranial tumors (grades I-IV), leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or Hodgkin lymphomas that had been diagnosed in a 14-year span between the years 2000 and 2013. They matched each case with 10 control participants without cancer by sex, date of birth, and date of entry into the cohort.

Radiation exposure was calculated for each patient according to number and type of CT scans received and an estimated organ-specific cumulative dose based on previously published models. The investigators excluded patients from the analysis if they had a diagnosis of any malignant disease before the study period or if they had any cancer-predisposing conditions, such as Down syndrome (which entails an increased risk of leukemia) or immunodeficiency (which may require multiple CT scans).

Compared with no exposure, exposure to a single pediatric CT scan was not associated with increased cancer risk. Exposure to two to three CT scans, however, was associated with an increased risk for intracranial tumour (adjusted odds ratio, 2.36), but not for leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or Hodgkin lymphoma. Exposure to four or more CT scans was associated with increased risk for intracranial tumor (aOR, 9.01), leukemia (aOR, 4.80), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (aOR, 6.76), but not for Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers also found a dose-response relationship. Participants in the top quintile of cumulative brain radiation dose had a significantly higher risk for intracranial tumor, compared with nonexposed participants (aOR, 3.61), although this relationship was not seen with the other cancers.

Age at exposure was also a significant factor. Children exposed to four or more CT scans at or before age 6 years had the highest risk for cancer (aOR, 22.95), followed by the same number of scans in those aged 7-12 years (aOR, 5.69) and those aged 13-18 years (aOR, 3.20).

The authors noted that, although these cancers are uncommon in children, “our work reinforces the importance of radiation protection strategies, addressed by the International Atomic Energy Agency. Unnecessary CT scans should be avoided, and special attention should be paid to patients who require repeated CT scans. Parents and pediatric patients should be well informed on risks and benefits before radiological procedures and encouraged to participate in decision-making around imaging.”

True risks underestimated?

Commenting on the findings, Rebecca Smith-Bindman, MD, a radiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert on the impact of CT scans on patient outcomes, said that she trusts the authors’ overall findings. But “because of the direction of their biases,” the study design “doesn’t let me accept their conclusion that one CT does not elevate the risk.

“It’s an interesting study that found the risk of brain cancer is more than doubled in children who undergo two or more CT scans, but in many ways, their assumptions will underestimate the true risk,” said Dr. Smith-Bindman, who is a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at UCSF. She said reasons for this include the fact that the investigators used estimated, rather than actual radiation doses; that their estimates “reflect doses far lower than we have found actually occur in clinical practice”; that they do not differentiate between a low-dose or a high-dose CT; and that that they include a long, 3-year lag during which leukemia can develop after a CT scan.

“They did a lot of really well-done adjustments to ensure that they were not overestimating risk,” said Dr. Smith-Bindman. “They made sure to delete children who had cancer susceptibility syndrome, they included a lag of 3 years, assuming that there could be hidden cancers for up to 3 years after the first imaging study when they might have had a preexisting cancer. These are decisions that ensure that any cancer risk they find is real, but it also means that the risks that are estimated are almost certainly an underestimate of the true risks.”

The study was conducted without external funding. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Smith-Bindman is a cofounder of Alara Imaging, a company focused on collecting and reporting radiation dose information associated with CT.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a population-based case-control study that included more than 85,000 participants, researchers found a ninefold increased risk of intracranial tumors among children who received four or more CT scans.

The results “indicate that judicious CT usage and radiation-reducing techniques should be advocated,” Yu-Hsuan Joni Shao, PhD, professor of biomedical informatics at Taipei (Taiwan) Medical University, and colleagues wrote.

The study was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Dose-response relationship

The investigators used the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan to identify 7,807 patients under age 25 years with intracranial tumors (grades I-IV), leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or Hodgkin lymphomas that had been diagnosed in a 14-year span between the years 2000 and 2013. They matched each case with 10 control participants without cancer by sex, date of birth, and date of entry into the cohort.

Radiation exposure was calculated for each patient according to number and type of CT scans received and an estimated organ-specific cumulative dose based on previously published models. The investigators excluded patients from the analysis if they had a diagnosis of any malignant disease before the study period or if they had any cancer-predisposing conditions, such as Down syndrome (which entails an increased risk of leukemia) or immunodeficiency (which may require multiple CT scans).

Compared with no exposure, exposure to a single pediatric CT scan was not associated with increased cancer risk. Exposure to two to three CT scans, however, was associated with an increased risk for intracranial tumour (adjusted odds ratio, 2.36), but not for leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or Hodgkin lymphoma. Exposure to four or more CT scans was associated with increased risk for intracranial tumor (aOR, 9.01), leukemia (aOR, 4.80), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (aOR, 6.76), but not for Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers also found a dose-response relationship. Participants in the top quintile of cumulative brain radiation dose had a significantly higher risk for intracranial tumor, compared with nonexposed participants (aOR, 3.61), although this relationship was not seen with the other cancers.

Age at exposure was also a significant factor. Children exposed to four or more CT scans at or before age 6 years had the highest risk for cancer (aOR, 22.95), followed by the same number of scans in those aged 7-12 years (aOR, 5.69) and those aged 13-18 years (aOR, 3.20).

The authors noted that, although these cancers are uncommon in children, “our work reinforces the importance of radiation protection strategies, addressed by the International Atomic Energy Agency. Unnecessary CT scans should be avoided, and special attention should be paid to patients who require repeated CT scans. Parents and pediatric patients should be well informed on risks and benefits before radiological procedures and encouraged to participate in decision-making around imaging.”

True risks underestimated?

Commenting on the findings, Rebecca Smith-Bindman, MD, a radiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert on the impact of CT scans on patient outcomes, said that she trusts the authors’ overall findings. But “because of the direction of their biases,” the study design “doesn’t let me accept their conclusion that one CT does not elevate the risk.

“It’s an interesting study that found the risk of brain cancer is more than doubled in children who undergo two or more CT scans, but in many ways, their assumptions will underestimate the true risk,” said Dr. Smith-Bindman, who is a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at UCSF. She said reasons for this include the fact that the investigators used estimated, rather than actual radiation doses; that their estimates “reflect doses far lower than we have found actually occur in clinical practice”; that they do not differentiate between a low-dose or a high-dose CT; and that that they include a long, 3-year lag during which leukemia can develop after a CT scan.

“They did a lot of really well-done adjustments to ensure that they were not overestimating risk,” said Dr. Smith-Bindman. “They made sure to delete children who had cancer susceptibility syndrome, they included a lag of 3 years, assuming that there could be hidden cancers for up to 3 years after the first imaging study when they might have had a preexisting cancer. These are decisions that ensure that any cancer risk they find is real, but it also means that the risks that are estimated are almost certainly an underestimate of the true risks.”

The study was conducted without external funding. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Smith-Bindman is a cofounder of Alara Imaging, a company focused on collecting and reporting radiation dose information associated with CT.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a population-based case-control study that included more than 85,000 participants, researchers found a ninefold increased risk of intracranial tumors among children who received four or more CT scans.

The results “indicate that judicious CT usage and radiation-reducing techniques should be advocated,” Yu-Hsuan Joni Shao, PhD, professor of biomedical informatics at Taipei (Taiwan) Medical University, and colleagues wrote.

The study was published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Dose-response relationship

The investigators used the National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan to identify 7,807 patients under age 25 years with intracranial tumors (grades I-IV), leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or Hodgkin lymphomas that had been diagnosed in a 14-year span between the years 2000 and 2013. They matched each case with 10 control participants without cancer by sex, date of birth, and date of entry into the cohort.

Radiation exposure was calculated for each patient according to number and type of CT scans received and an estimated organ-specific cumulative dose based on previously published models. The investigators excluded patients from the analysis if they had a diagnosis of any malignant disease before the study period or if they had any cancer-predisposing conditions, such as Down syndrome (which entails an increased risk of leukemia) or immunodeficiency (which may require multiple CT scans).

Compared with no exposure, exposure to a single pediatric CT scan was not associated with increased cancer risk. Exposure to two to three CT scans, however, was associated with an increased risk for intracranial tumour (adjusted odds ratio, 2.36), but not for leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or Hodgkin lymphoma. Exposure to four or more CT scans was associated with increased risk for intracranial tumor (aOR, 9.01), leukemia (aOR, 4.80), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (aOR, 6.76), but not for Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers also found a dose-response relationship. Participants in the top quintile of cumulative brain radiation dose had a significantly higher risk for intracranial tumor, compared with nonexposed participants (aOR, 3.61), although this relationship was not seen with the other cancers.

Age at exposure was also a significant factor. Children exposed to four or more CT scans at or before age 6 years had the highest risk for cancer (aOR, 22.95), followed by the same number of scans in those aged 7-12 years (aOR, 5.69) and those aged 13-18 years (aOR, 3.20).

The authors noted that, although these cancers are uncommon in children, “our work reinforces the importance of radiation protection strategies, addressed by the International Atomic Energy Agency. Unnecessary CT scans should be avoided, and special attention should be paid to patients who require repeated CT scans. Parents and pediatric patients should be well informed on risks and benefits before radiological procedures and encouraged to participate in decision-making around imaging.”

True risks underestimated?

Commenting on the findings, Rebecca Smith-Bindman, MD, a radiologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and an expert on the impact of CT scans on patient outcomes, said that she trusts the authors’ overall findings. But “because of the direction of their biases,” the study design “doesn’t let me accept their conclusion that one CT does not elevate the risk.

“It’s an interesting study that found the risk of brain cancer is more than doubled in children who undergo two or more CT scans, but in many ways, their assumptions will underestimate the true risk,” said Dr. Smith-Bindman, who is a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at UCSF. She said reasons for this include the fact that the investigators used estimated, rather than actual radiation doses; that their estimates “reflect doses far lower than we have found actually occur in clinical practice”; that they do not differentiate between a low-dose or a high-dose CT; and that that they include a long, 3-year lag during which leukemia can develop after a CT scan.

“They did a lot of really well-done adjustments to ensure that they were not overestimating risk,” said Dr. Smith-Bindman. “They made sure to delete children who had cancer susceptibility syndrome, they included a lag of 3 years, assuming that there could be hidden cancers for up to 3 years after the first imaging study when they might have had a preexisting cancer. These are decisions that ensure that any cancer risk they find is real, but it also means that the risks that are estimated are almost certainly an underestimate of the true risks.”

The study was conducted without external funding. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Smith-Bindman is a cofounder of Alara Imaging, a company focused on collecting and reporting radiation dose information associated with CT.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

‘Shocking’ data on what’s really in melatonin gummies

New data may explain the recent massive jump in pediatric hospitalizations.

Thenvestigators found that consuming some products as directed could expose consumers, including children, to doses that are 40-130 times greater than what’s recommended.

“The results were quite shocking,” lead researcher Pieter Cohen, MD, with Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass., said in an interview.

“Melatonin gummies contained up to 347% more melatonin than what was listed on the label, and some products also contained cannabidiol; in one brand of melatonin gummies, there was zero melatonin, just CBD,” Dr. Cohen said.

The study was published online in JAMA.

530% jump in pediatric hospitalizations

Melatonin products are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration but are sold over the counter or online.

Previous research from JAMA has shown the use of melatonin has increased over the past 2 decades among people of all ages.

With increased use has come a spike in reports of melatonin overdose, calls to poison control centers, and related ED visits for children.

Federal data show the number of U.S. children who unintentionally ingested melatonin supplements jumped 530% from 2012 to 2021. More than 4,000 of the reported ingestions led to a hospital stay; 287 children required intensive care, and two children died.

It was unclear why melatonin supplements were causing these harms, which led Dr. Cohen’s team to analyze 25 unique brands of “melatonin” gummies purchased online.

One product didn’t contain any melatonin but did contain 31.3 mg of CBD.

In the remaining products, the quantity of melatonin ranged from 1.3 mg to 13.1 mg per serving. The actual quantity of melatonin ranged from 74% to 347% of the labeled quantity, the researchers found.

They note that for a young adult who takes as little as 0.1-0.3 mg of melatonin, plasma concentrations can increase into the normal night-time range.

Of the 25 products (88%) analyzed, 22 were inaccurately labeled, and only 3 (12%) contained a quantity of melatonin that was within 10% (plus or minus) of the declared quantity.

Five products listed CBD as an ingredient. The listed quantity ranged from 10.6 mg to 31.3 mg per serving, although the actual quantity of CBD ranged from 104% to 118% of the labeled quantity.

Inquire about use in kids

A limitation of the study is that only one sample of each brand was analyzed, and only gummies were analyzed. It is not known whether the results are generalizable to melatonin products sold as tablets and capsules in the United States or whether the quantity of melatonin within an individual brand may vary from batch to batch.

A recent study from Canada showed similar results. In an analysis of 16 Canadian melatonin brands, the actual dose of melatonin ranged from 17% to 478% of the declared quantity.

It’s estimated that more than 1% of all U.S. children use melatonin supplements, most commonly for sleep, stress, and relaxation.

“Given new research as to the excessive quantities of melatonin in gummies, caution should be used if considering their use,” said Dr. Cohen.

“It’s important to inquire about melatonin use when caring for children, particularly when parents express concerns about their child’s sleep,” he added.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently issued a health advisory encouraging parents to talk to a health care professional before giving melatonin or any supplement to children.

Children don’t need melatonin

Commenting on the study, Michael Breus, PhD, clinical psychologist and founder of TheSleepDoctor.com, agreed that analyzing only one sample of each brand is a key limitation “because supplements are made in batches, and gummies in particular are difficult to distribute the active ingredient evenly.

“But even with that being said, 88% of them were labeled incorrectly, so even if there were a few single-sample issues, I kind of doubt its all of them,” Dr. Breus said.

“Kids as a general rule do not need melatonin. Their brains make almost four times the necessary amount already. If you start giving kids pills to help them sleep, then they start to have a pill problem, causing another issue,” Dr. Breus added.

“Most children’s falling asleep and staying sleep issues can be treated with behavioral measures like cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia,” he said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cohen has received research support from Consumers Union and PEW Charitable Trusts and royalties from UptoDate. Dr. Breus disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data may explain the recent massive jump in pediatric hospitalizations.

Thenvestigators found that consuming some products as directed could expose consumers, including children, to doses that are 40-130 times greater than what’s recommended.

“The results were quite shocking,” lead researcher Pieter Cohen, MD, with Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass., said in an interview.

“Melatonin gummies contained up to 347% more melatonin than what was listed on the label, and some products also contained cannabidiol; in one brand of melatonin gummies, there was zero melatonin, just CBD,” Dr. Cohen said.

The study was published online in JAMA.

530% jump in pediatric hospitalizations

Melatonin products are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration but are sold over the counter or online.

Previous research from JAMA has shown the use of melatonin has increased over the past 2 decades among people of all ages.

With increased use has come a spike in reports of melatonin overdose, calls to poison control centers, and related ED visits for children.

Federal data show the number of U.S. children who unintentionally ingested melatonin supplements jumped 530% from 2012 to 2021. More than 4,000 of the reported ingestions led to a hospital stay; 287 children required intensive care, and two children died.

It was unclear why melatonin supplements were causing these harms, which led Dr. Cohen’s team to analyze 25 unique brands of “melatonin” gummies purchased online.

One product didn’t contain any melatonin but did contain 31.3 mg of CBD.

In the remaining products, the quantity of melatonin ranged from 1.3 mg to 13.1 mg per serving. The actual quantity of melatonin ranged from 74% to 347% of the labeled quantity, the researchers found.

They note that for a young adult who takes as little as 0.1-0.3 mg of melatonin, plasma concentrations can increase into the normal night-time range.

Of the 25 products (88%) analyzed, 22 were inaccurately labeled, and only 3 (12%) contained a quantity of melatonin that was within 10% (plus or minus) of the declared quantity.

Five products listed CBD as an ingredient. The listed quantity ranged from 10.6 mg to 31.3 mg per serving, although the actual quantity of CBD ranged from 104% to 118% of the labeled quantity.

Inquire about use in kids

A limitation of the study is that only one sample of each brand was analyzed, and only gummies were analyzed. It is not known whether the results are generalizable to melatonin products sold as tablets and capsules in the United States or whether the quantity of melatonin within an individual brand may vary from batch to batch.

A recent study from Canada showed similar results. In an analysis of 16 Canadian melatonin brands, the actual dose of melatonin ranged from 17% to 478% of the declared quantity.

It’s estimated that more than 1% of all U.S. children use melatonin supplements, most commonly for sleep, stress, and relaxation.

“Given new research as to the excessive quantities of melatonin in gummies, caution should be used if considering their use,” said Dr. Cohen.

“It’s important to inquire about melatonin use when caring for children, particularly when parents express concerns about their child’s sleep,” he added.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently issued a health advisory encouraging parents to talk to a health care professional before giving melatonin or any supplement to children.

Children don’t need melatonin

Commenting on the study, Michael Breus, PhD, clinical psychologist and founder of TheSleepDoctor.com, agreed that analyzing only one sample of each brand is a key limitation “because supplements are made in batches, and gummies in particular are difficult to distribute the active ingredient evenly.

“But even with that being said, 88% of them were labeled incorrectly, so even if there were a few single-sample issues, I kind of doubt its all of them,” Dr. Breus said.

“Kids as a general rule do not need melatonin. Their brains make almost four times the necessary amount already. If you start giving kids pills to help them sleep, then they start to have a pill problem, causing another issue,” Dr. Breus added.

“Most children’s falling asleep and staying sleep issues can be treated with behavioral measures like cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia,” he said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cohen has received research support from Consumers Union and PEW Charitable Trusts and royalties from UptoDate. Dr. Breus disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data may explain the recent massive jump in pediatric hospitalizations.

Thenvestigators found that consuming some products as directed could expose consumers, including children, to doses that are 40-130 times greater than what’s recommended.

“The results were quite shocking,” lead researcher Pieter Cohen, MD, with Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass., said in an interview.

“Melatonin gummies contained up to 347% more melatonin than what was listed on the label, and some products also contained cannabidiol; in one brand of melatonin gummies, there was zero melatonin, just CBD,” Dr. Cohen said.

The study was published online in JAMA.

530% jump in pediatric hospitalizations

Melatonin products are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration but are sold over the counter or online.

Previous research from JAMA has shown the use of melatonin has increased over the past 2 decades among people of all ages.

With increased use has come a spike in reports of melatonin overdose, calls to poison control centers, and related ED visits for children.

Federal data show the number of U.S. children who unintentionally ingested melatonin supplements jumped 530% from 2012 to 2021. More than 4,000 of the reported ingestions led to a hospital stay; 287 children required intensive care, and two children died.

It was unclear why melatonin supplements were causing these harms, which led Dr. Cohen’s team to analyze 25 unique brands of “melatonin” gummies purchased online.

One product didn’t contain any melatonin but did contain 31.3 mg of CBD.

In the remaining products, the quantity of melatonin ranged from 1.3 mg to 13.1 mg per serving. The actual quantity of melatonin ranged from 74% to 347% of the labeled quantity, the researchers found.

They note that for a young adult who takes as little as 0.1-0.3 mg of melatonin, plasma concentrations can increase into the normal night-time range.

Of the 25 products (88%) analyzed, 22 were inaccurately labeled, and only 3 (12%) contained a quantity of melatonin that was within 10% (plus or minus) of the declared quantity.

Five products listed CBD as an ingredient. The listed quantity ranged from 10.6 mg to 31.3 mg per serving, although the actual quantity of CBD ranged from 104% to 118% of the labeled quantity.

Inquire about use in kids

A limitation of the study is that only one sample of each brand was analyzed, and only gummies were analyzed. It is not known whether the results are generalizable to melatonin products sold as tablets and capsules in the United States or whether the quantity of melatonin within an individual brand may vary from batch to batch.

A recent study from Canada showed similar results. In an analysis of 16 Canadian melatonin brands, the actual dose of melatonin ranged from 17% to 478% of the declared quantity.

It’s estimated that more than 1% of all U.S. children use melatonin supplements, most commonly for sleep, stress, and relaxation.

“Given new research as to the excessive quantities of melatonin in gummies, caution should be used if considering their use,” said Dr. Cohen.

“It’s important to inquire about melatonin use when caring for children, particularly when parents express concerns about their child’s sleep,” he added.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently issued a health advisory encouraging parents to talk to a health care professional before giving melatonin or any supplement to children.

Children don’t need melatonin

Commenting on the study, Michael Breus, PhD, clinical psychologist and founder of TheSleepDoctor.com, agreed that analyzing only one sample of each brand is a key limitation “because supplements are made in batches, and gummies in particular are difficult to distribute the active ingredient evenly.

“But even with that being said, 88% of them were labeled incorrectly, so even if there were a few single-sample issues, I kind of doubt its all of them,” Dr. Breus said.

“Kids as a general rule do not need melatonin. Their brains make almost four times the necessary amount already. If you start giving kids pills to help them sleep, then they start to have a pill problem, causing another issue,” Dr. Breus added.

“Most children’s falling asleep and staying sleep issues can be treated with behavioral measures like cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia,” he said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cohen has received research support from Consumers Union and PEW Charitable Trusts and royalties from UptoDate. Dr. Breus disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

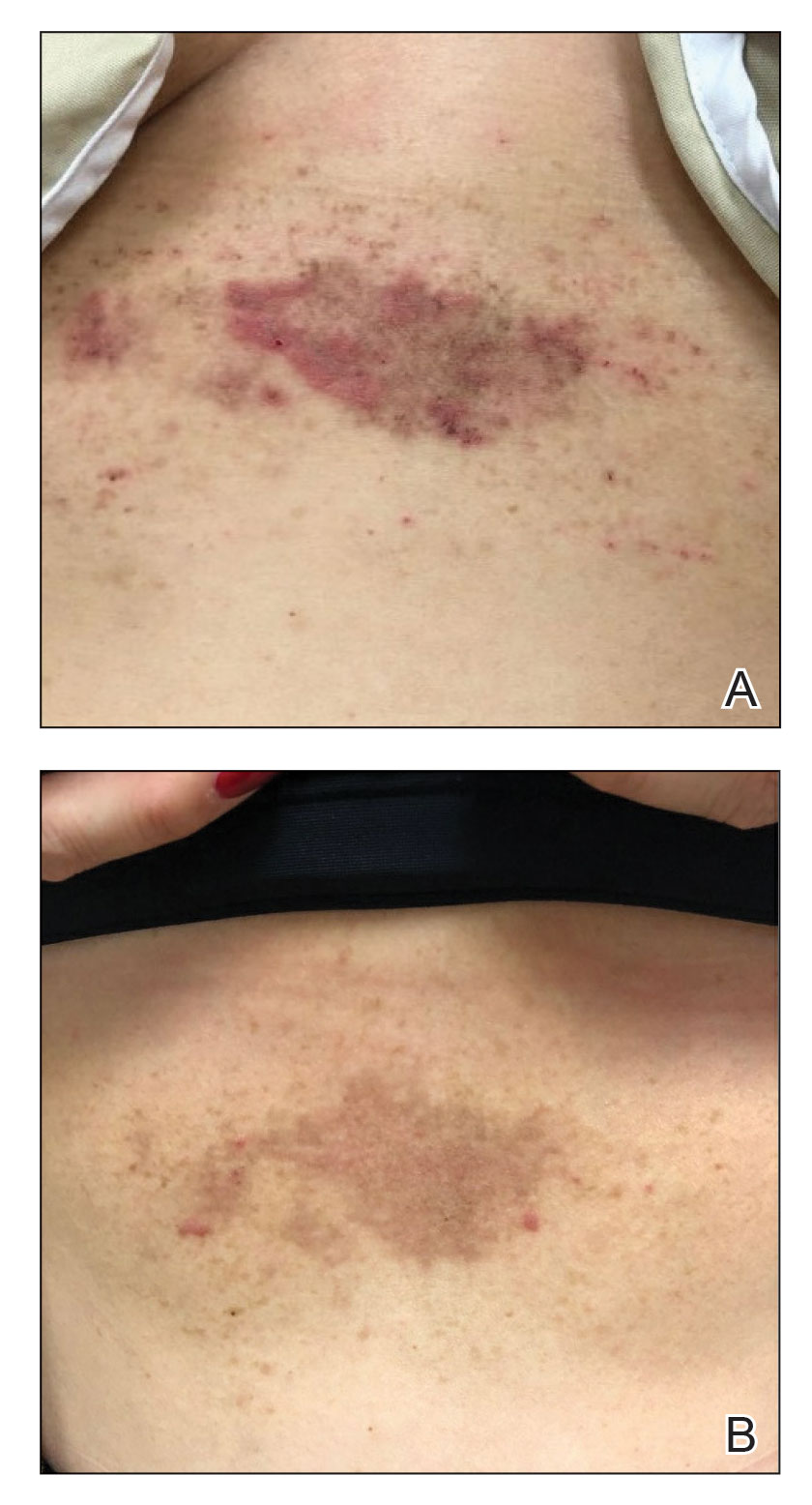

Skin Diseases Associated With COVID-19: A Narrative Review

COVID-19 is a potentially severe systemic disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) caused fatal epidemics in Asia in 2002 to 2003 and in the Arabian Peninsula in 2012, respectively. In 2019, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in patients with severe, sometimes fatal pneumonia of previously unknown origin; it rapidly spread around the world, and the World Health Organization declared the disease a pandemic on March 11, 2020. SARS-CoV-2 is a β-coronavirus that is genetically related to the bat coronavirus and SARS-CoV; it is a single-stranded RNA virus of which several variants and subvariants exist. The SARS-CoV-2 viral particles bind via their surface spike protein (S protein) to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor present on the membrane of several cell types, including epidermal and adnexal keratinocytes.1,2 The α and δ variants, predominant from 2020 to 2021, mainly affected the lower respiratory tract and caused severe, potentially fatal pneumonia, especially in patients older than 65 years and/or with comorbidities, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and (iatrogenic) immunosuppression. The ο variant, which appeared in late 2021, is more contagious than the initial variants, but it causes a less severe disease preferentially affecting the upper respiratory airways.3 As of April 5, 2023, more than 762,000,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been recorded worldwide, causing more than 6,800,000 deaths.4

Early studies from China describing the symptoms of COVID-19 reported a low frequency of skin manifestations (0.2%), probably because they were focused on the most severe disease symptoms.5 Subsequently, when COVID-19 spread to the rest of the world, an increasing number of skin manifestations were reported in association with the disease. After the first publication from northern Italy in spring 2020, which was specifically devoted to skin manifestations of COVID-19,6 an explosive number of publications reported a large number of skin manifestations, and national registries were established in several countries to record these manifestations, such as the American Academy of Dermatology and the International League of Dermatological Societies registry,7,8 the COVIDSKIN registry of the French Dermatology Society,9 and the Italian registry.10 Highlighting the unprecedented number of scientific articles published on this new disease, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE search using the terms SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19, on April 6, 2023, revealed 351,596 articles; that is more than 300 articles published every day in this database alone, with a large number of them concerning the skin.

SKIN DISEASSES ASSOCIATED WITH COVID-19

There are several types of COVID-19–related skin manifestations, depending on the circumstances of onset and the evolution of the pandemic.

Skin Manifestations Associated With SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The estimated incidence varies greatly according to the published series of patients, possibly depending on the geographic location. The estimated incidence seems lower in Asian countries, such as China (0.2%)5 and Japan (0.56%),11 compared with Europe (up to 20%).6 Skin manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection affect individuals of all ages, slightly more females, and are clinically polymorphous; some of them are associated with the severity of the infection.12 They may precede, accompany, or appear after the symptoms of COVID-19, most often within a month of the infection, of which they rarely are the only manifestation; however, their precise relationship to SARS-CoV-2 is not always well known. They have been classified according to their clinical presentation into several forms.13-15

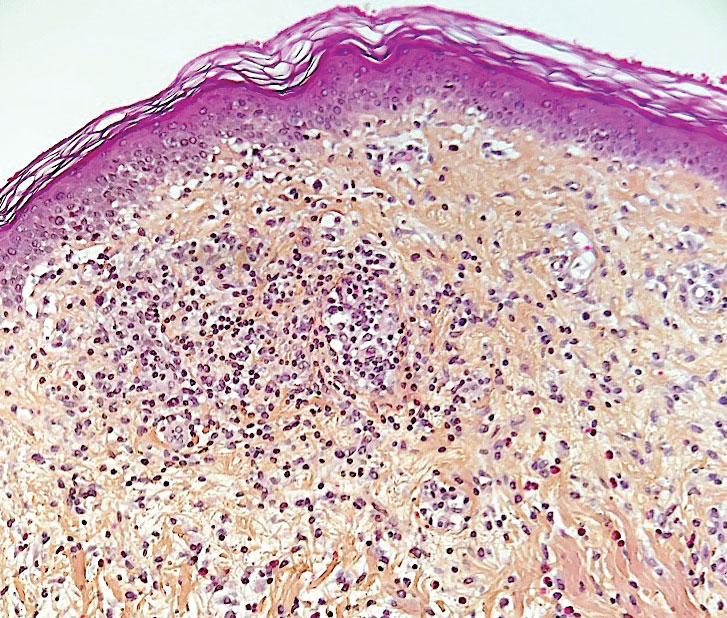

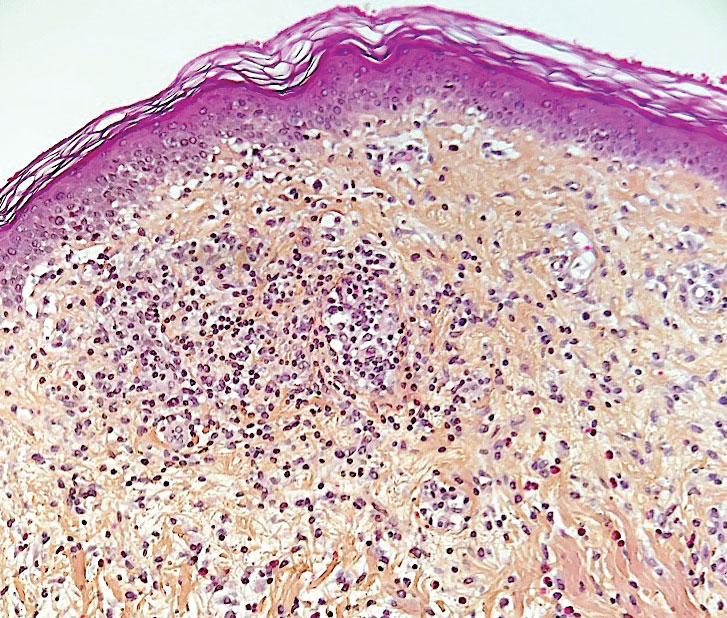

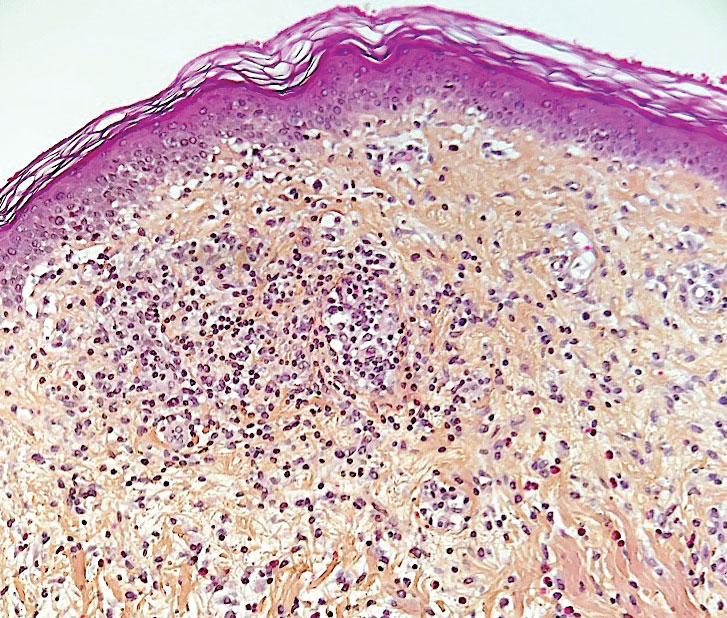

Morbilliform Maculopapular Eruption—Representing 16% to 53% of skin manifestations, morbilliform and maculopapular eruptions usually appear within 15 days of infection; they manifest with more or less confluent erythematous macules that may be hemorrhagic/petechial, and usually are asymptomatic and rarely pruritic. The rash mainly affects the trunk and limbs, sparing the face, palmoplantar regions, and mucous membranes; it appears concomitantly with or a few days after the first symptoms of COVID-19 (eg, fever, respiratory symptoms), regresses within a few days, and does not appear to be associated with disease severity. The distinction from maculopapular drug eruptions may be subtle. Histologically, the rash manifests with a spongiform dermatitis (ie, variable parakeratosis; spongiosis; and a mixed dermal perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils and histiocytes, depending on the lesion age)(Figure 1). The etiopathogenesis is unknown; it may involve immune complexes to SARS-CoV-2 deposited on skin vessels. Treatment is not mandatory; if necessary, local or systemic corticosteroids may be used.

Vesicular (Pseudovaricella) Rash—This rash accounts for 11% to 18% of all skin manifestations and usually appears within 15 days of COVID-19 onset. It manifests with small monomorphous or varicellalike (pseudopolymorphic) vesicles appearing on the trunk, usually in young patients. The vesicles may be herpetiform, hemorrhagic, or pruritic, and appear before or within 3 days of the onset of mild COVID-19 symptoms; they regress within a few days without scarring. Histologically, the lesions show basal cell vacuolization; multinucleated, dyskeratotic/apoptotic or ballooning/acantholytic epidermal keratinocytes; reticular degeneration of the epidermis; intraepidermal vesicles sometimes resembling herpetic vesicular infections or Grover disease; and mild dermal inflammation. There is no specific treatment.

Urticaria—Urticarial rash, or urticaria, represents 5% to 16% of skin manifestations; usually appears within 15 days of disease onset; and manifests with pruritic, migratory, edematous papules appearing mainly on the trunk and occasionally the face and limbs. The urticarial rash tends to be associated with more severe forms of the disease and regresses within a week, responding to antihistamines. Of note, clinically similar rashes can be caused by drugs. Histologically, the lesions show dermal edema and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, sometimes admixed with eosinophils.

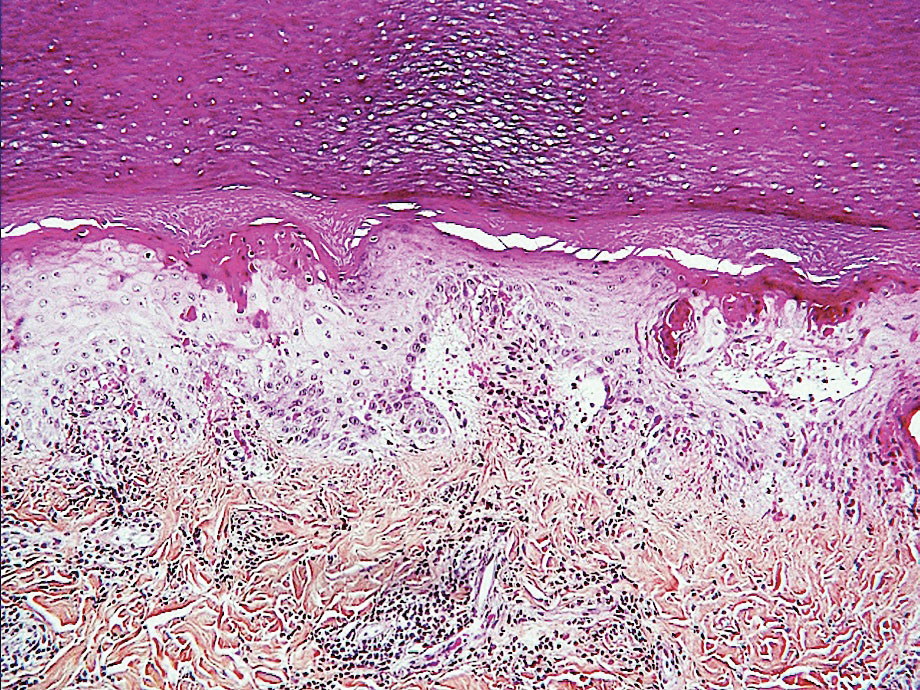

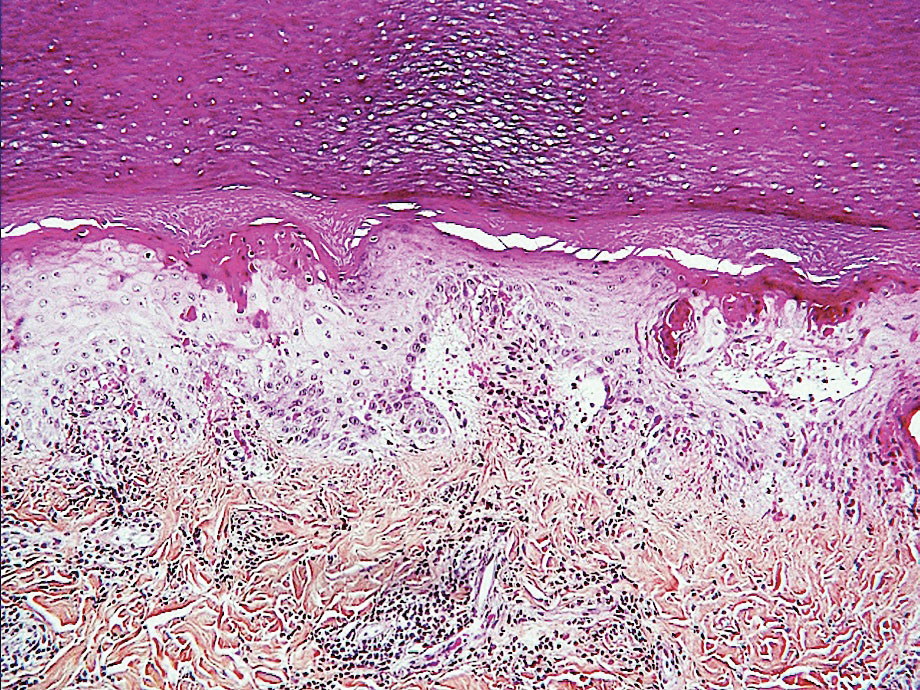

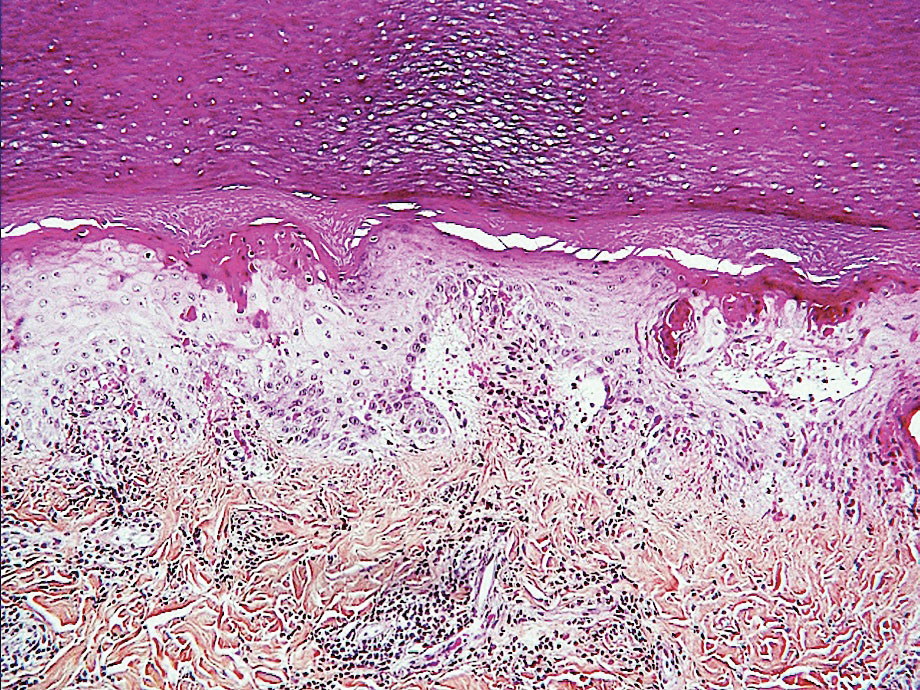

Chilblainlike Lesions—Chilblainlike lesions (CBLLs) account for 19% of skin manifestations associated with COVID-1913 and present as erythematous-purplish, edematous lesions that can be mildly pruritic or painful, appearing on the toes—COVID toes—and more rarely the fingers (Figure 2). They were seen epidemically during the first pandemic wave (2020 lockdown) in several countries, and clinically are very similar to, if not indistinguishable from, idiopathic chilblains, but are not necessarily associated with cold exposure. They appear in young, generally healthy patients or those with mild COVID-19 symptoms 2 to 4 weeks after symptom onset. They regress spontaneously or under local corticosteroid treatment within a few days or weeks. Histologically, CBLLs are indistinguishable from chilblains of other origins, namely idiopathic (seasonal) ones. They manifest with necrosis of epidermal keratinocytes; dermal edema that may be severe, leading to the development of subepidermal pseudobullae; a rather dense perivascular and perieccrine gland lymphocytic infiltrate; and sometimes with vascular lesions (eg, edema of endothelial cells, microthromboses of dermal capillaries and venules, fibrinoid deposits within the wall of dermal venules)(Figure 3).16-18 Most patients (>80%) with CBLLs have negative serologic or polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2,19 which generated a lively debate about the role of SARS-CoV-2 in the genesis of CBLLs. According to some authors, SARS-CoV-2 plays no direct role, and CBLLs would occur in young people who sit or walk barefoot on cold floors at home during confinement.20-23 Remarkably, CBLLs appeared in patients with no history of chilblains during a season that was not particularly cold, namely in France or in southern California, where their incidence was much higher compared to the same time period of prior years. Some reports have supported a direct role for the virus based on questionable observations of the virus within skin lesions (eg, sweat glands, endothelial cells) by immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and/or in situ hybridization.17,24,25 A more satisfactory hypothesis would involve the role of a strong innate immunity leading to elimination of the virus before the development of specific antibodies via the increased production of type 1 interferon (IFN-1); this would affect the vessels, causing CBLLs. This mechanism would be similar to the one observed in some interferonopathies (eg, Aicardi-Goutières syndrome), also characterized by IFN-1 hypersecretion and chilblains.26-29 According to this hypothesis, CBLLs should be considered a paraviral rash similar to other skin manifestations associated with COVID-19.30

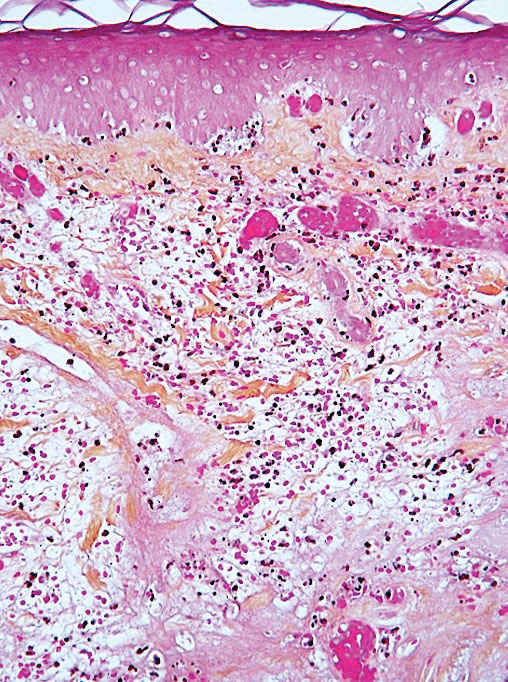

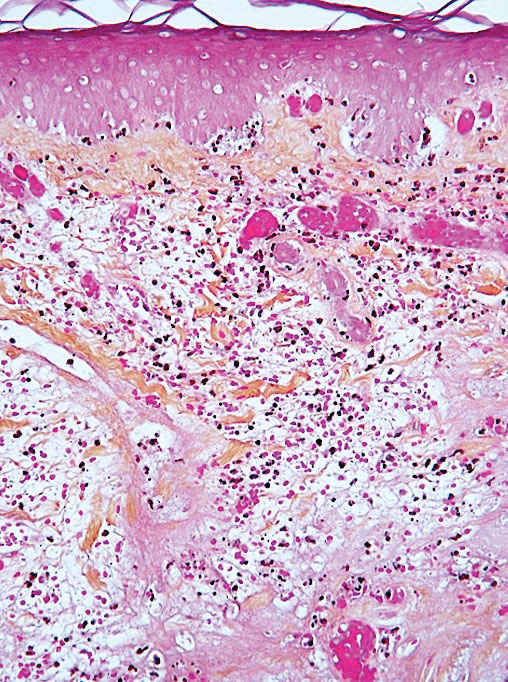

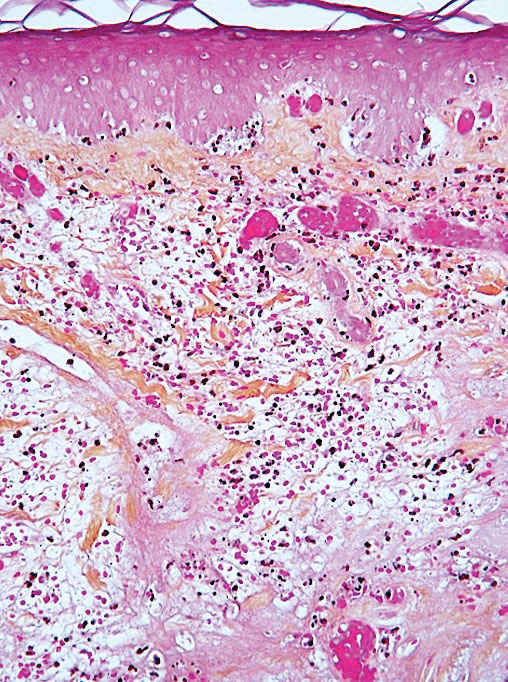

Acro-ischemia—Acro-ischemia livedoid lesions account for 1% to 6% of skin manifestations and comprise lesions of livedo (either reticulated or racemosa); necrotic acral bullae; and gangrenous necrosis of the extremities, especially the toes. The livedoid lesions most often appear within 15 days of COVID-19 symptom onset, and the purpuric lesions somewhat later (2–4 weeks); they mainly affect adult patients, last about 10 days, and are the hallmark of severe infection, presumably related to microthromboses of the cutaneous capillaries (endothelial dysfunction, prothrombotic state, elevated D-dimers). Histologically, they show capillary thrombosis and dermoepidermal necrosis (Figure 4).

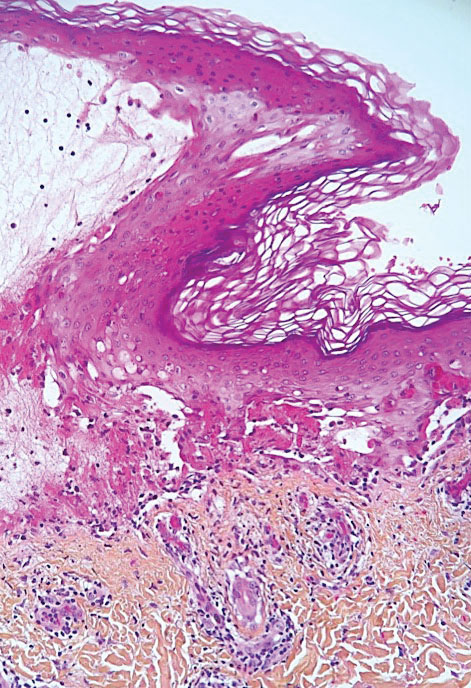

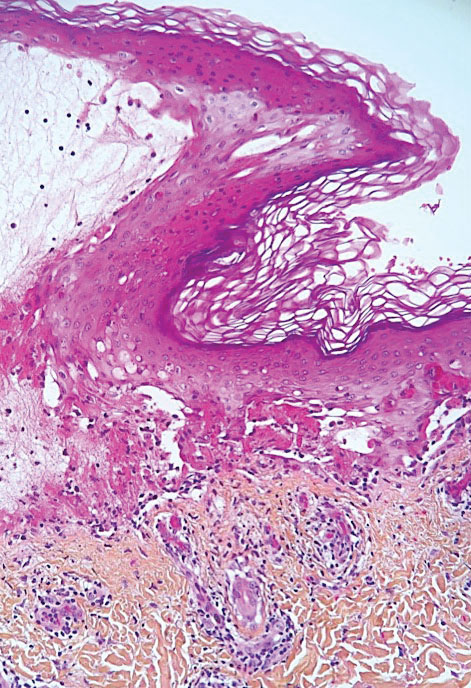

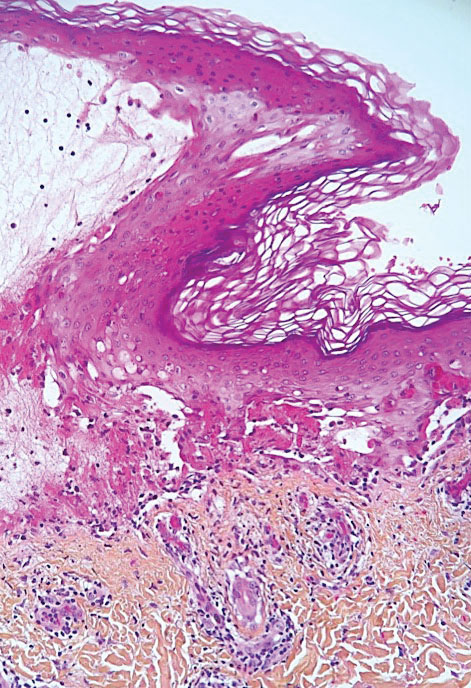

Other Reported Polymorphic or Atypical Rashes—Erythema multiforme–like eruptions may appear before other COVID-19 symptoms and manifest as reddish-purple, nearly symmetric, diffuse, occasionally targetoid bullous or necrotic macules. The eruptions mainly affect adults and most often are seen on the palms, elbows, knees, and sometimes the mucous membranes. The rash regresses in 1 to 3 weeks without scarring and represents a delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction. Histologically, the lesions show vacuolization of basal epidermal keratinocytes, keratinocyte necrosis, dermoepidermal detachment, a variably dense dermal T-lymphocytic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation (Figure 5).

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be generalized or localized. It manifests clinically by petechial/purpuric maculopapules, especially on the legs, mainly in elderly patients with COVID-19. Histologically, the lesions show necrotizing changes of dermal postcapillary venules, neutrophilic perivascular inflammation, red blood cell extravasation, and occasionally vascular IgA deposits by direct immunofluorescence examination. The course usually is benign.

The incidence of pityriasis rosea and of clinically similar rashes (referred to as “pityriasis rosea–like”) increased 5-fold during the COVID-19 pandemic.31,32 These dermatoses manifest with erythematous, scaly, circinate plaques, typically with an initial herald lesion followed a few days later by smaller erythematous macules. Histologically, the lesions comprise a spongiform dermatitis with intraepidermal exocytosis of red blood cells and a mild to moderate dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.

Erythrodysesthesia, or hand-foot syndrome, manifests with edematous erythema and palmoplantar desquamation accompanied by a burning sensation or pain. This syndrome is known as an adverse effect of some chemotherapies because of the associated drug toxicity and sweat gland inflammation; it was observed in 40% of 666 COVID-19–positive patients with mild to moderate pneumonitis.33

“COVID nose” is a rare cutaneous manifestation characterized by nasal pigmentation comprising multiple coalescent frecklelike macules on the tip and wings of the nose and sometimes the malar areas. These lesions predominantly appear in women aged 25 to 65 years and show on average 23 days after onset of COVID-19, which is usually mild. This pigmentation is similar to pigmentary changes after infection with chikungunya; it can be treated with depigmenting products such as azelaic acid and hydroquinone cream with sunscreen use, and it regresses in 2 to 4 months.34

Telogen effluvium (excessive and temporary shedding of normal telogen club hairs of the entire scalp due to the disturbance of the hair cycle) is reportedly frequent in patients (48%) 1 month after COVID-19 infection, but it may appear later (after 12 weeks).35 Alopecia also is frequently reported during long (or postacute) COVID-19 (ie, the symptomatic disease phase past the acute 4 weeks’ stage of the infection) and shows a female predominance36; it likely represents the telogen effluvium seen 90 days after a severe illness. Trichodynia (pruritus, burning, pain, or paresthesia of the scalp) also is reportedly common (developing in more than 58% of patients) and is associated with telogen effluvium in 44% of cases. Several cases of alopecia areata (AA) triggered or aggravated by COVID-19 also have been reported37,38; they could be explained by the “cytokine storm” triggered by the infection, involving T and B lymphocytes; plasmacytoid dendritic cells; natural killer cells with oversecretion of IL-6, IL-4, tumor necrosis factor α, and IFN type I; and a cytotoxic reaction associated with loss of the immune privilege of hair follicles.

Nail Manifestations