User login

Iron deficiency and anemia in patients with heavy menstrual bleeding: Mechanisms and management

Recurrent episodic blood loss from normal menstruation is not expected to result in anemia. But without treatment, chronic heavy periods will progress through the stages of low iron stores to iron deficiency and then to anemia. When iron storage levels are low, the bone marrow’s blood cell factory cannot keep up with continued losses. Every patient with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) or prolonged menstrual episodes should be tested and treated for iron deficiency and anemia.1,2

Particular attention should be paid to assessment of iron storage levels with serum ferritin, recognizing that low iron levels progress to anemia once the storage is depleted. Recovery from anemia is much slower in individuals with iron deficiency, so assessment for iron storage also should be included in preoperative assessments and following a diagnosis of acute blood loss anemia.

The mechanics of erythropoiesis, hemoglobin, and oxygen transport

Red blood cells (erythrocytes) have a short life cycle and require constant replacement. Erythrocytes are generated on demand in erythropoiesis by a hormonal signaling process, regardless of whether sufficient components are available.3 Hemoglobin, the main intracellular component of erythrocytes, is comprised of 4 globin chains, which each contain 1 iron atom bound to a heme molecule. After erythrocytes are assembled, they are sent out into circulation for approximately 120 days. A hemoglobin level measures the oxygen-carrying capacity of erythrocytes, and anemia is defined as hemoglobin less than 12 g/dL.

Unless erythrocytes are lost from bleeding, they are decommissioned—that is, the heme molecule is metabolized into bilirubin and excreted, and the iron atoms are recycled back to the bone marrow or to storage.4 Ferritin is the storage molecule that binds to iron, a glycoprotein with numerous subunits around a core that can contain about 4,000 iron atoms. Most ferritin is intracellular, but a small proportion is present in serum, where it can be measured.

Serum ferritin is a good marker for the iron supply in healthy individuals because it has high correlation to iron in the bone marrow and correlates to total intracellular storage unless there is inflammation, when mobilization to serum increases. The ferritin level at which the iron supply is deficient to meet demand, defined as iron deficiency, is hotly debated and ranges from less than 15 to 50 ng/mL in menstruating individuals, with higher thresholds based on onset of erythropoiesis signaling and the lower threshold being the World Health Organization recommendation.5-7 When iron atoms are in short supply, erythrocytes still are generated but they have lower amounts of intracellular hemoglobin, which makes them thinner, smaller, and paler—and less effective at oxygen transport.

CASE Patient seeks treatment for HMB-associated symptoms

A 17-year-old patient presents with HMB, fatigue, and difficulty with concentration. She reports that her periods have been regular and lasting 7 days since menarche at age 13. While they are manageable, they seem to be getting heavier, soaking pads in 2 to 3 hours. The patient reports that she would like to start treatment for her progressively heavy bleeding and prefers lighter scheduled bleeding; she currently does not desire contraception. The patient has no family history of bleeding problems and self-reports no personal history of epistaxis or bleeding with tooth extraction or tonsillectomy. Laboratory tests confirm iron deficiency with a hemoglobin level of 12.5 g/dL (reference range, 12.0–17.5 g/dL) and a serum ferritin level of 8 ng/mL (reference range, 50–420 ng/mL). Results from a coagulopathy panel are normal, as are von Willebrand factor levels.

Untreated iron deficiency will progress to anemia

This patient has iron deficiency without anemia, which warrants significant attention in HMB because without treatment it eventually will progress to anemia. The prevalence of iron deficiency, which makes up half of all causes of anemia, is at least double that of iron deficiency anemia.3

Adult bodies usually contain about 3 to 4 g of iron, with two-thirds in erythrocytes as hemoglobin.8 Approximately 40 to 60 mg of iron is recycled daily, 1 to 2 mg/day is lost from sloughed cells and sweat, and at least 1 mg/day is lost during normal menstruation. These losses are balanced with gastrointestinal uptake of 1 to 2 mg/day until bleeding exceeds about 10 mL/day. In this 17-year-old patient, iron stores have likely been on a progressive decline since menarche.

For normally menstruating individuals to maintain iron homeostasis, the daily dietary iron requirement is 18 mg/day. Iron requirements also increase during periods of illness or inflammation due to hormonal signaling in the iron absorption and transport pathway, in athletes due to sweating, foot strike hemolysis and bruising, and during growth spurts.9

Continue to: Managing iron deficiency and anemia...

Managing iron deficiency and anemia

Management of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in the setting of HMB includes:

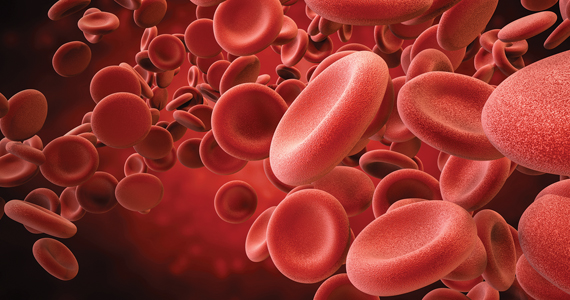

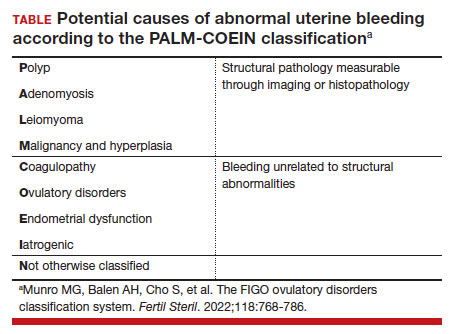

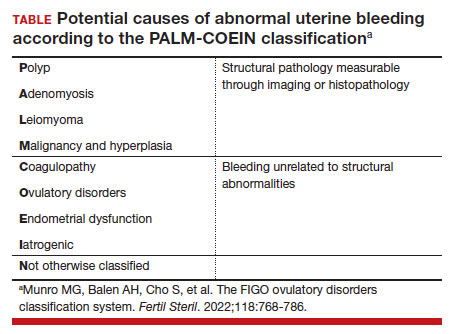

- workup for the etiology of the abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE)

- reducing the source of blood loss, and

- iron supplementation to correct the iron deficiency state.

In most cases, workup, reduction, and repletion can occur simultaneously. The goal is not always complete cessation of menstrual bleeding; even short-term therapy can allow time to replenish iron storage. Use a shared decision-making process to assess what is important to the patient, and provide information about relative amounts of bleeding cessation that can be expected with various therapies.10

Treatment options

Medical treatments to decrease menstrual iron losses are recommended prior to proceeding with surgical interventions.11 Hormonal treatments are the most consistently recommended, with many guidelines citing the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG IUD) as first-line treatment due to its substantial reduction in the amount of bleeding, HMB treatment indication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and evidence of success in those with HMB.12

Any progestin or combined hormonal medication with estrogen and a progestin will result in an approximately 60% to 90% bleeding reduction, thus providing many effective options for blood loss while considering patient preferences for bleeding pattern, route of administration, and concomitant benefits. While only 1 oral product (estradiol valerate/dienogest) is FDA approved for managementof HMB, use of any of the commercially available contraceptive products will provide substantial benefit.11,13

Nonhormonal options, such as antifibrinolytics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tend to be listed as second-line therapies or for those who want to avoid hormonal medications. Antifibrinolytics, such as tranexamic acid, require frequent dosing of large pills and result in approximately 40% blood loss reduction, but they are a very successful and well-tolerated method for those seeking on-demand therapy.14 NSAIDs may result in a slight bleeding reduction, but they are far less effective than other therapies.15 Antifibrinolytics have a theoretical risk of thrombosis and a contraindication to use with hormonal contraceptives; therefore, concomitant use with estrogen-containing medications is reserved for patients with refractory heavy bleeding or for heavy bleeding days during the hormone-free interval, when benefits likely outweigh potential risk.16,17

Guidelines for medical management of acute HMB typically cite 3 small comparative studies with high-dose regimens of parenteral conjugated estrogen, combined ethinyl estradiol and progestin, or oral medroxyprogesterone acetate.18,19 Dosing recommendations for the oral medications include a loading dose followed by a taper regimen that is poorly tolerated and for which there is no evidence of superior effectiveness over the standard dose.20,21 In most cases, initiation of the preferred long-term hormonal medication plan will reduce bleeding significantly within 2 to 3 days. Many clinicians who commonly treat acute HMB prescribe norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (up to 3 times daily, if needed) for effective and safe menstrual suppression.22

Iron replenishment: Dosing frequency, dietary iron, and multivitamins

Iron repletion is usually via the oral route unless surgery is imminent, anemia is severe, or the oral route is not tolerated or effective.23 Oral iron has substantial adverse effects that limit tolerance, including nausea, epigastric pain, diarrhea, and constipation. Fortunately, evidence supports lower oral iron doses than previously used.4

Iron homeostasis is controlled by the peptide hormone hepcidin, produced by the liver, which controls mobilization of iron from the gut and spleen and aids iron absorption from the diet and supplements.24 Hepcidin levels decrease in response to high circulating levels of iron, so the ideal iron repletion dose in iron-deficient nonanemic women was determined by assessing the dose response of hepcidin. Researchers compared iron 60 mg daily for 14 days versus every other day for 28 days and found that iron absorption was greater in the every-other-day group (21.8% vs 16.3%).25 They concluded that changing iron administration to 60 mg or more in a single dose every other day is most efficient in those with iron deficiency without anemia. Since study participants did not have anemia, research is pending on whether different strategies (such as daily dosing) are more effective for more severe cases. The bottom line is that conventional high-dose divided daily oral iron administration results in reduced iron bioavailability compared with alternate-day dosing.

Increasing dietary iron is insufficient to treat low iron storage, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. Likewise, multivitamins, which contain very little elemental iron, are not recommended for repletion. Any iron salt with 60 to 120 mg of elemental iron can be used (for examples, ferrous sulfate, ferrous gluconate).25 Once ingested, stomach and pancreatic acids release elemental iron from its bound form. For that reason, absorption may be improved by administering iron at least 1 hour before a meal and avoiding antacids, including milk. Meat proteins and ascorbic acid help maintain the soluble ferrous form and also aid absorption. Tea, coffee, and tannins prevent absorption when polyphenol compounds form an insoluble complex with iron (see box at end of article). Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be minimized by decreasing the dose and taking after meals, although with reduced efficacy.

Intravenous iron treatment raises hemoglobin levels significantly faster than oral administration but is limited by cost and availability, so it is reserved for individuals with a hemoglobin level less than 9 g/dL, prior gastrointestinal or bariatric surgery, imminent surgery, and intolerance, poor adherence, or nonresponse to oral iron therapy. Several approved formulations are available, all with equivalent effectiveness and similar safety profiles. Lower-dose formulations (such as iron sucrose) may require several infusions, but higher-dose intravenous iron products (ferric carboxymaltose, low-molecular weight iron dextran, etc) have a stable carbohydrate shell that inhibits free iron release and improves safety, allowing a single administration.26

Common adverse effects of intravenous iron treatment include a metallic taste and headache during administration. More serious adverse effects, such as hypotension, arthralgia, malaise, and nausea, are usually self-limited. With mild infusion reactions (1 in 200), the infusion can be stopped until symptoms improve and can be resumed at a slower rate.27

Continue to: The role of blood transfusion...

The role of blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is expensive and potentially hazardous, so its use is limited to treatment of acute blood loss or severe anemia.

A one-time red blood cell transfusion does not impact diagnostic criteria to assess for iron deficiency with ferritin, and it does not improve underlying iron deficiency.28 Patients with acute blood loss anemia superimposed on chronic blood loss should be screened and treated for iron deficiency even after receiving a transfusion.

Since ferritin levels can rise significantly as an acute phase reactant, even following a hemorrhage, iron deficiency during inflammation is defined as ferritin less than 70 ng/mL.

The potential for iron overload

Since iron is never metabolized or excreted, it is possible to have iron overload following accidental overdose, transfusion dependency, and disorders of iron transport, such as hemochromatosis and thalassemia.

While a low ferritin level always indicates iron deficiency, high ferritin levels can be an acute phase reactant. Ferritin levels greater than 150 ng/mL in healthy menstruating individuals and greater than 500 ng/mL in unhealthy individuals should raise concern for excess iron and should prompt discontinuation of iron intake or workup for conditions at risk for overload.5

Oral iron supplements should be stored away from small children, who are at particular risk of toxicity.

How long to treat?

Treatment duration depends on the individual’s degree of iron deficiency, whether anemia is present, and the amount of ongoing blood loss. The main treatment goal is normalization and maintenance of serum ferritin.

Successful treatment should be confirmed with a complete blood count and ferritin level. Hemoglobin levels improve 2 g/dL after 3 weeks of oral iron therapy, but repletion may take 4 to 6 months.23,29 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends 3 to 6 months of continued iron therapy after resolution of HMB.19

In a comparative study of treatment for HMB with the 52-mg LNG IUD versus hysterectomy, hemoglobin levels increased in both treatment groups but stayed lower in those with initial anemia.8 Ferritin levels normalized only after 5 years and were still lower in individuals with initial anemia.

Increase in hemoglobin is faster after intravenous iron administration but is equivalent to oral therapy by 12 weeks. If management to reduce menstrual losses is discontinued, periodic or maintenance iron repletion will be necessary.

CASE Management plan initiated

This 17-year-old patient with iron deficiency resulting from HMB requests management to reduce menstrual iron losses with a preference for predictable menses. We have already completed a basic workup, which could also include assessment for hypermobility with a Beighton score, as connective tissue disorders also are associated with HMB.30 We discuss the options of cyclic hormonal therapy, antifibrinolytic treatment, and an LNG IUD. The patient is concerned about adherence and wants to avoid unscheduled bleeding, so she opts for a trial of tranexamic acid 1,300 mg 3 times daily for 5 days during menses. This regimen results in a 50% reduction in bleeding amount, which the patient finds satisfactory. Iron repletion with oral ferrous sulfate 325 mg (containing 65 mg of elemental iron) is administered on alternating days with vitamin C taken 1 hour prior to dinner. Repeat laboratory test results at 3 weeks show improvement to a hemoglobin level of 14.2 g/dL and a ferritin level of 12 ng/mL. By 3 months, her ferritin levels are greater than 30 ng/mL and oral iron is administered only during menses.

Summing up

Chronic HMB results in a progressive net loss of iron and eventual anemia. Screening with complete blood count and ferritin and early treatment of low iron storage when ferritin is less than 30 ng/mL will help avoid symptoms. Any amount of reduction of menstrual blood loss can be beneficial, allowing a variety of effective hormonal and nonhormonal treatment options. ●

- Take 60 to 120 mg elemental iron every other day.

- To help with absorption:

—Take 1 hour before a meal, but not with coffee, tea, tannins, antacids, or milk

—Take with vitamin C or other acidic fruit juice

- Recheck complete blood count and ferritin in 2 to 3 weeks to confirm initial response.

- Continue treatment for up to 3 to 6 months until ferritin levels are greater than 30 to 50 ng/mL.

- Munro MG, Mast AE, Powers JM, et al. The relationship between heavy menstrual bleeding, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;S00029378(23)00024-8.

- Tsakiridis I, Giouleka S, Koutsouki G, et al. Investigation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive aged women: a descriptive review of national and international recommendations. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2022;27:504-517.

- Camaschella C. Iron deficiency. Blood. 2019;133:30-39.

- Camaschella C, Nai A, Silvestri L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica. 2020;105:260-272.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on use of ferritin concentrations to assess iron status in individuals and populations. April 21, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000124

- Mei Z, Addo OY, Jefferds ME, et al. Physiologically based serum ferritin thresholds for iron deficiency in children and non-pregnant women: a US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) serial cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8: e572-e582.

- Galetti V, Stoffel NU, Sieber C, et al. Threshold ferritin and hepcidin concentrations indicating early iron deficiency in young women based on upregulation of iron absorption. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101052.

- Percy L, Mansour D, Fraser I. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:55-67.

- Brittenham GM. Short-term periods of strenuous physical activity lower iron absorption. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113:261-262.

- Chen M, Lindley A, Kimport K, et al. An in-depth analysis of the use of shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2019;99:187-191.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Dias S, Jordan V, et al. Interventions for heavy menstrual bleeding; overview of Cochrane reviews and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013180.

- Mansour D, Hofmann A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. A review of clinical guidelines on the management of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Adv Ther. 2021;38:201-225.

- Micks EA, Jensen JT. Treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding with the estradiol valerate and dienogest oral contraceptive pill. Adv Ther. 2013;30:1-13.

- Bryant-Smith AC, Lethaby A, Farquhar C, et al. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD000249.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:CD000400.

- Relke N, Chornenki NLJ, Sholzberg M. Tranexamic acid evidence and controversies: an illustrated review. Res Pract T hromb Haemost. 2021;5:e12546.

- Reid RL, Westhoff C, Mansour D, et al. Oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism consensus opinion from an international workshop held in Berlin, Germany in December 2009. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36:117-122.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:891-896.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 785: screening and management of bleeding disorders in adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e71-e83.

- Haamid F, Sass AE, Dietrich JE. Heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:335-340.

- Roth LP, Haley KM, Baldwin MK. A retrospective comparison of time to cessation of acute heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents following two dose regimens of combined oral hormonal therapy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2022;35:294-298.

- Huguelet PS, Buyers EM, Lange-Liss JH, et al. Treatment of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents: what are providers doing in various specialties? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:286-291.

- Elstrott B, Khan L, Olson S, et al. The role of iron repletion in adult iron deficiency anemia and other diseases. Eur J Haematol. 2020;104:153-161.

- Pagani A, Nai A, Silvestri L, et al. Hepcidin and anemia: a tight relationship. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1294.

- Stoffel NU, von Siebenthal HK, Moretti D, et al. Oral iron supplementation in iron-deficient women: how much and how often? Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75:100865.

- Auerbach M, Adamson JW. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:31-38.

- Dave CV, Brittenham GM, Carson JL, et al. Risks for anaphylaxis with intravenous iron formulations: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:656-664.

- Froissart A, Rossi B, Ranque B, et al; SiMFI Group. Effect of a red blood cell transfusion on biological markers used to determine the cause of anemia: a prospective study. Am J Med. 2018;131:319-322.

- Carson JL, Brittenham GM. How I treat anemia with red blood cell transfusion and iron. Blood. 2022;blood.2022018521.

- Borzutzky C, Jaffray J. Diagnosis and management of heavy menstrual bleeding and bleeding disorders in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:186-194.

Recurrent episodic blood loss from normal menstruation is not expected to result in anemia. But without treatment, chronic heavy periods will progress through the stages of low iron stores to iron deficiency and then to anemia. When iron storage levels are low, the bone marrow’s blood cell factory cannot keep up with continued losses. Every patient with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) or prolonged menstrual episodes should be tested and treated for iron deficiency and anemia.1,2

Particular attention should be paid to assessment of iron storage levels with serum ferritin, recognizing that low iron levels progress to anemia once the storage is depleted. Recovery from anemia is much slower in individuals with iron deficiency, so assessment for iron storage also should be included in preoperative assessments and following a diagnosis of acute blood loss anemia.

The mechanics of erythropoiesis, hemoglobin, and oxygen transport

Red blood cells (erythrocytes) have a short life cycle and require constant replacement. Erythrocytes are generated on demand in erythropoiesis by a hormonal signaling process, regardless of whether sufficient components are available.3 Hemoglobin, the main intracellular component of erythrocytes, is comprised of 4 globin chains, which each contain 1 iron atom bound to a heme molecule. After erythrocytes are assembled, they are sent out into circulation for approximately 120 days. A hemoglobin level measures the oxygen-carrying capacity of erythrocytes, and anemia is defined as hemoglobin less than 12 g/dL.

Unless erythrocytes are lost from bleeding, they are decommissioned—that is, the heme molecule is metabolized into bilirubin and excreted, and the iron atoms are recycled back to the bone marrow or to storage.4 Ferritin is the storage molecule that binds to iron, a glycoprotein with numerous subunits around a core that can contain about 4,000 iron atoms. Most ferritin is intracellular, but a small proportion is present in serum, where it can be measured.

Serum ferritin is a good marker for the iron supply in healthy individuals because it has high correlation to iron in the bone marrow and correlates to total intracellular storage unless there is inflammation, when mobilization to serum increases. The ferritin level at which the iron supply is deficient to meet demand, defined as iron deficiency, is hotly debated and ranges from less than 15 to 50 ng/mL in menstruating individuals, with higher thresholds based on onset of erythropoiesis signaling and the lower threshold being the World Health Organization recommendation.5-7 When iron atoms are in short supply, erythrocytes still are generated but they have lower amounts of intracellular hemoglobin, which makes them thinner, smaller, and paler—and less effective at oxygen transport.

CASE Patient seeks treatment for HMB-associated symptoms

A 17-year-old patient presents with HMB, fatigue, and difficulty with concentration. She reports that her periods have been regular and lasting 7 days since menarche at age 13. While they are manageable, they seem to be getting heavier, soaking pads in 2 to 3 hours. The patient reports that she would like to start treatment for her progressively heavy bleeding and prefers lighter scheduled bleeding; she currently does not desire contraception. The patient has no family history of bleeding problems and self-reports no personal history of epistaxis or bleeding with tooth extraction or tonsillectomy. Laboratory tests confirm iron deficiency with a hemoglobin level of 12.5 g/dL (reference range, 12.0–17.5 g/dL) and a serum ferritin level of 8 ng/mL (reference range, 50–420 ng/mL). Results from a coagulopathy panel are normal, as are von Willebrand factor levels.

Untreated iron deficiency will progress to anemia

This patient has iron deficiency without anemia, which warrants significant attention in HMB because without treatment it eventually will progress to anemia. The prevalence of iron deficiency, which makes up half of all causes of anemia, is at least double that of iron deficiency anemia.3

Adult bodies usually contain about 3 to 4 g of iron, with two-thirds in erythrocytes as hemoglobin.8 Approximately 40 to 60 mg of iron is recycled daily, 1 to 2 mg/day is lost from sloughed cells and sweat, and at least 1 mg/day is lost during normal menstruation. These losses are balanced with gastrointestinal uptake of 1 to 2 mg/day until bleeding exceeds about 10 mL/day. In this 17-year-old patient, iron stores have likely been on a progressive decline since menarche.

For normally menstruating individuals to maintain iron homeostasis, the daily dietary iron requirement is 18 mg/day. Iron requirements also increase during periods of illness or inflammation due to hormonal signaling in the iron absorption and transport pathway, in athletes due to sweating, foot strike hemolysis and bruising, and during growth spurts.9

Continue to: Managing iron deficiency and anemia...

Managing iron deficiency and anemia

Management of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in the setting of HMB includes:

- workup for the etiology of the abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE)

- reducing the source of blood loss, and

- iron supplementation to correct the iron deficiency state.

In most cases, workup, reduction, and repletion can occur simultaneously. The goal is not always complete cessation of menstrual bleeding; even short-term therapy can allow time to replenish iron storage. Use a shared decision-making process to assess what is important to the patient, and provide information about relative amounts of bleeding cessation that can be expected with various therapies.10

Treatment options

Medical treatments to decrease menstrual iron losses are recommended prior to proceeding with surgical interventions.11 Hormonal treatments are the most consistently recommended, with many guidelines citing the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG IUD) as first-line treatment due to its substantial reduction in the amount of bleeding, HMB treatment indication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and evidence of success in those with HMB.12

Any progestin or combined hormonal medication with estrogen and a progestin will result in an approximately 60% to 90% bleeding reduction, thus providing many effective options for blood loss while considering patient preferences for bleeding pattern, route of administration, and concomitant benefits. While only 1 oral product (estradiol valerate/dienogest) is FDA approved for managementof HMB, use of any of the commercially available contraceptive products will provide substantial benefit.11,13

Nonhormonal options, such as antifibrinolytics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tend to be listed as second-line therapies or for those who want to avoid hormonal medications. Antifibrinolytics, such as tranexamic acid, require frequent dosing of large pills and result in approximately 40% blood loss reduction, but they are a very successful and well-tolerated method for those seeking on-demand therapy.14 NSAIDs may result in a slight bleeding reduction, but they are far less effective than other therapies.15 Antifibrinolytics have a theoretical risk of thrombosis and a contraindication to use with hormonal contraceptives; therefore, concomitant use with estrogen-containing medications is reserved for patients with refractory heavy bleeding or for heavy bleeding days during the hormone-free interval, when benefits likely outweigh potential risk.16,17

Guidelines for medical management of acute HMB typically cite 3 small comparative studies with high-dose regimens of parenteral conjugated estrogen, combined ethinyl estradiol and progestin, or oral medroxyprogesterone acetate.18,19 Dosing recommendations for the oral medications include a loading dose followed by a taper regimen that is poorly tolerated and for which there is no evidence of superior effectiveness over the standard dose.20,21 In most cases, initiation of the preferred long-term hormonal medication plan will reduce bleeding significantly within 2 to 3 days. Many clinicians who commonly treat acute HMB prescribe norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (up to 3 times daily, if needed) for effective and safe menstrual suppression.22

Iron replenishment: Dosing frequency, dietary iron, and multivitamins

Iron repletion is usually via the oral route unless surgery is imminent, anemia is severe, or the oral route is not tolerated or effective.23 Oral iron has substantial adverse effects that limit tolerance, including nausea, epigastric pain, diarrhea, and constipation. Fortunately, evidence supports lower oral iron doses than previously used.4

Iron homeostasis is controlled by the peptide hormone hepcidin, produced by the liver, which controls mobilization of iron from the gut and spleen and aids iron absorption from the diet and supplements.24 Hepcidin levels decrease in response to high circulating levels of iron, so the ideal iron repletion dose in iron-deficient nonanemic women was determined by assessing the dose response of hepcidin. Researchers compared iron 60 mg daily for 14 days versus every other day for 28 days and found that iron absorption was greater in the every-other-day group (21.8% vs 16.3%).25 They concluded that changing iron administration to 60 mg or more in a single dose every other day is most efficient in those with iron deficiency without anemia. Since study participants did not have anemia, research is pending on whether different strategies (such as daily dosing) are more effective for more severe cases. The bottom line is that conventional high-dose divided daily oral iron administration results in reduced iron bioavailability compared with alternate-day dosing.

Increasing dietary iron is insufficient to treat low iron storage, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. Likewise, multivitamins, which contain very little elemental iron, are not recommended for repletion. Any iron salt with 60 to 120 mg of elemental iron can be used (for examples, ferrous sulfate, ferrous gluconate).25 Once ingested, stomach and pancreatic acids release elemental iron from its bound form. For that reason, absorption may be improved by administering iron at least 1 hour before a meal and avoiding antacids, including milk. Meat proteins and ascorbic acid help maintain the soluble ferrous form and also aid absorption. Tea, coffee, and tannins prevent absorption when polyphenol compounds form an insoluble complex with iron (see box at end of article). Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be minimized by decreasing the dose and taking after meals, although with reduced efficacy.

Intravenous iron treatment raises hemoglobin levels significantly faster than oral administration but is limited by cost and availability, so it is reserved for individuals with a hemoglobin level less than 9 g/dL, prior gastrointestinal or bariatric surgery, imminent surgery, and intolerance, poor adherence, or nonresponse to oral iron therapy. Several approved formulations are available, all with equivalent effectiveness and similar safety profiles. Lower-dose formulations (such as iron sucrose) may require several infusions, but higher-dose intravenous iron products (ferric carboxymaltose, low-molecular weight iron dextran, etc) have a stable carbohydrate shell that inhibits free iron release and improves safety, allowing a single administration.26

Common adverse effects of intravenous iron treatment include a metallic taste and headache during administration. More serious adverse effects, such as hypotension, arthralgia, malaise, and nausea, are usually self-limited. With mild infusion reactions (1 in 200), the infusion can be stopped until symptoms improve and can be resumed at a slower rate.27

Continue to: The role of blood transfusion...

The role of blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is expensive and potentially hazardous, so its use is limited to treatment of acute blood loss or severe anemia.

A one-time red blood cell transfusion does not impact diagnostic criteria to assess for iron deficiency with ferritin, and it does not improve underlying iron deficiency.28 Patients with acute blood loss anemia superimposed on chronic blood loss should be screened and treated for iron deficiency even after receiving a transfusion.

Since ferritin levels can rise significantly as an acute phase reactant, even following a hemorrhage, iron deficiency during inflammation is defined as ferritin less than 70 ng/mL.

The potential for iron overload

Since iron is never metabolized or excreted, it is possible to have iron overload following accidental overdose, transfusion dependency, and disorders of iron transport, such as hemochromatosis and thalassemia.

While a low ferritin level always indicates iron deficiency, high ferritin levels can be an acute phase reactant. Ferritin levels greater than 150 ng/mL in healthy menstruating individuals and greater than 500 ng/mL in unhealthy individuals should raise concern for excess iron and should prompt discontinuation of iron intake or workup for conditions at risk for overload.5

Oral iron supplements should be stored away from small children, who are at particular risk of toxicity.

How long to treat?

Treatment duration depends on the individual’s degree of iron deficiency, whether anemia is present, and the amount of ongoing blood loss. The main treatment goal is normalization and maintenance of serum ferritin.

Successful treatment should be confirmed with a complete blood count and ferritin level. Hemoglobin levels improve 2 g/dL after 3 weeks of oral iron therapy, but repletion may take 4 to 6 months.23,29 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends 3 to 6 months of continued iron therapy after resolution of HMB.19

In a comparative study of treatment for HMB with the 52-mg LNG IUD versus hysterectomy, hemoglobin levels increased in both treatment groups but stayed lower in those with initial anemia.8 Ferritin levels normalized only after 5 years and were still lower in individuals with initial anemia.

Increase in hemoglobin is faster after intravenous iron administration but is equivalent to oral therapy by 12 weeks. If management to reduce menstrual losses is discontinued, periodic or maintenance iron repletion will be necessary.

CASE Management plan initiated

This 17-year-old patient with iron deficiency resulting from HMB requests management to reduce menstrual iron losses with a preference for predictable menses. We have already completed a basic workup, which could also include assessment for hypermobility with a Beighton score, as connective tissue disorders also are associated with HMB.30 We discuss the options of cyclic hormonal therapy, antifibrinolytic treatment, and an LNG IUD. The patient is concerned about adherence and wants to avoid unscheduled bleeding, so she opts for a trial of tranexamic acid 1,300 mg 3 times daily for 5 days during menses. This regimen results in a 50% reduction in bleeding amount, which the patient finds satisfactory. Iron repletion with oral ferrous sulfate 325 mg (containing 65 mg of elemental iron) is administered on alternating days with vitamin C taken 1 hour prior to dinner. Repeat laboratory test results at 3 weeks show improvement to a hemoglobin level of 14.2 g/dL and a ferritin level of 12 ng/mL. By 3 months, her ferritin levels are greater than 30 ng/mL and oral iron is administered only during menses.

Summing up

Chronic HMB results in a progressive net loss of iron and eventual anemia. Screening with complete blood count and ferritin and early treatment of low iron storage when ferritin is less than 30 ng/mL will help avoid symptoms. Any amount of reduction of menstrual blood loss can be beneficial, allowing a variety of effective hormonal and nonhormonal treatment options. ●

- Take 60 to 120 mg elemental iron every other day.

- To help with absorption:

—Take 1 hour before a meal, but not with coffee, tea, tannins, antacids, or milk

—Take with vitamin C or other acidic fruit juice

- Recheck complete blood count and ferritin in 2 to 3 weeks to confirm initial response.

- Continue treatment for up to 3 to 6 months until ferritin levels are greater than 30 to 50 ng/mL.

Recurrent episodic blood loss from normal menstruation is not expected to result in anemia. But without treatment, chronic heavy periods will progress through the stages of low iron stores to iron deficiency and then to anemia. When iron storage levels are low, the bone marrow’s blood cell factory cannot keep up with continued losses. Every patient with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) or prolonged menstrual episodes should be tested and treated for iron deficiency and anemia.1,2

Particular attention should be paid to assessment of iron storage levels with serum ferritin, recognizing that low iron levels progress to anemia once the storage is depleted. Recovery from anemia is much slower in individuals with iron deficiency, so assessment for iron storage also should be included in preoperative assessments and following a diagnosis of acute blood loss anemia.

The mechanics of erythropoiesis, hemoglobin, and oxygen transport

Red blood cells (erythrocytes) have a short life cycle and require constant replacement. Erythrocytes are generated on demand in erythropoiesis by a hormonal signaling process, regardless of whether sufficient components are available.3 Hemoglobin, the main intracellular component of erythrocytes, is comprised of 4 globin chains, which each contain 1 iron atom bound to a heme molecule. After erythrocytes are assembled, they are sent out into circulation for approximately 120 days. A hemoglobin level measures the oxygen-carrying capacity of erythrocytes, and anemia is defined as hemoglobin less than 12 g/dL.

Unless erythrocytes are lost from bleeding, they are decommissioned—that is, the heme molecule is metabolized into bilirubin and excreted, and the iron atoms are recycled back to the bone marrow or to storage.4 Ferritin is the storage molecule that binds to iron, a glycoprotein with numerous subunits around a core that can contain about 4,000 iron atoms. Most ferritin is intracellular, but a small proportion is present in serum, where it can be measured.

Serum ferritin is a good marker for the iron supply in healthy individuals because it has high correlation to iron in the bone marrow and correlates to total intracellular storage unless there is inflammation, when mobilization to serum increases. The ferritin level at which the iron supply is deficient to meet demand, defined as iron deficiency, is hotly debated and ranges from less than 15 to 50 ng/mL in menstruating individuals, with higher thresholds based on onset of erythropoiesis signaling and the lower threshold being the World Health Organization recommendation.5-7 When iron atoms are in short supply, erythrocytes still are generated but they have lower amounts of intracellular hemoglobin, which makes them thinner, smaller, and paler—and less effective at oxygen transport.

CASE Patient seeks treatment for HMB-associated symptoms

A 17-year-old patient presents with HMB, fatigue, and difficulty with concentration. She reports that her periods have been regular and lasting 7 days since menarche at age 13. While they are manageable, they seem to be getting heavier, soaking pads in 2 to 3 hours. The patient reports that she would like to start treatment for her progressively heavy bleeding and prefers lighter scheduled bleeding; she currently does not desire contraception. The patient has no family history of bleeding problems and self-reports no personal history of epistaxis or bleeding with tooth extraction or tonsillectomy. Laboratory tests confirm iron deficiency with a hemoglobin level of 12.5 g/dL (reference range, 12.0–17.5 g/dL) and a serum ferritin level of 8 ng/mL (reference range, 50–420 ng/mL). Results from a coagulopathy panel are normal, as are von Willebrand factor levels.

Untreated iron deficiency will progress to anemia

This patient has iron deficiency without anemia, which warrants significant attention in HMB because without treatment it eventually will progress to anemia. The prevalence of iron deficiency, which makes up half of all causes of anemia, is at least double that of iron deficiency anemia.3

Adult bodies usually contain about 3 to 4 g of iron, with two-thirds in erythrocytes as hemoglobin.8 Approximately 40 to 60 mg of iron is recycled daily, 1 to 2 mg/day is lost from sloughed cells and sweat, and at least 1 mg/day is lost during normal menstruation. These losses are balanced with gastrointestinal uptake of 1 to 2 mg/day until bleeding exceeds about 10 mL/day. In this 17-year-old patient, iron stores have likely been on a progressive decline since menarche.

For normally menstruating individuals to maintain iron homeostasis, the daily dietary iron requirement is 18 mg/day. Iron requirements also increase during periods of illness or inflammation due to hormonal signaling in the iron absorption and transport pathway, in athletes due to sweating, foot strike hemolysis and bruising, and during growth spurts.9

Continue to: Managing iron deficiency and anemia...

Managing iron deficiency and anemia

Management of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in the setting of HMB includes:

- workup for the etiology of the abnormal uterine bleeding (TABLE)

- reducing the source of blood loss, and

- iron supplementation to correct the iron deficiency state.

In most cases, workup, reduction, and repletion can occur simultaneously. The goal is not always complete cessation of menstrual bleeding; even short-term therapy can allow time to replenish iron storage. Use a shared decision-making process to assess what is important to the patient, and provide information about relative amounts of bleeding cessation that can be expected with various therapies.10

Treatment options

Medical treatments to decrease menstrual iron losses are recommended prior to proceeding with surgical interventions.11 Hormonal treatments are the most consistently recommended, with many guidelines citing the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG IUD) as first-line treatment due to its substantial reduction in the amount of bleeding, HMB treatment indication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and evidence of success in those with HMB.12

Any progestin or combined hormonal medication with estrogen and a progestin will result in an approximately 60% to 90% bleeding reduction, thus providing many effective options for blood loss while considering patient preferences for bleeding pattern, route of administration, and concomitant benefits. While only 1 oral product (estradiol valerate/dienogest) is FDA approved for managementof HMB, use of any of the commercially available contraceptive products will provide substantial benefit.11,13

Nonhormonal options, such as antifibrinolytics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tend to be listed as second-line therapies or for those who want to avoid hormonal medications. Antifibrinolytics, such as tranexamic acid, require frequent dosing of large pills and result in approximately 40% blood loss reduction, but they are a very successful and well-tolerated method for those seeking on-demand therapy.14 NSAIDs may result in a slight bleeding reduction, but they are far less effective than other therapies.15 Antifibrinolytics have a theoretical risk of thrombosis and a contraindication to use with hormonal contraceptives; therefore, concomitant use with estrogen-containing medications is reserved for patients with refractory heavy bleeding or for heavy bleeding days during the hormone-free interval, when benefits likely outweigh potential risk.16,17

Guidelines for medical management of acute HMB typically cite 3 small comparative studies with high-dose regimens of parenteral conjugated estrogen, combined ethinyl estradiol and progestin, or oral medroxyprogesterone acetate.18,19 Dosing recommendations for the oral medications include a loading dose followed by a taper regimen that is poorly tolerated and for which there is no evidence of superior effectiveness over the standard dose.20,21 In most cases, initiation of the preferred long-term hormonal medication plan will reduce bleeding significantly within 2 to 3 days. Many clinicians who commonly treat acute HMB prescribe norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (up to 3 times daily, if needed) for effective and safe menstrual suppression.22

Iron replenishment: Dosing frequency, dietary iron, and multivitamins

Iron repletion is usually via the oral route unless surgery is imminent, anemia is severe, or the oral route is not tolerated or effective.23 Oral iron has substantial adverse effects that limit tolerance, including nausea, epigastric pain, diarrhea, and constipation. Fortunately, evidence supports lower oral iron doses than previously used.4

Iron homeostasis is controlled by the peptide hormone hepcidin, produced by the liver, which controls mobilization of iron from the gut and spleen and aids iron absorption from the diet and supplements.24 Hepcidin levels decrease in response to high circulating levels of iron, so the ideal iron repletion dose in iron-deficient nonanemic women was determined by assessing the dose response of hepcidin. Researchers compared iron 60 mg daily for 14 days versus every other day for 28 days and found that iron absorption was greater in the every-other-day group (21.8% vs 16.3%).25 They concluded that changing iron administration to 60 mg or more in a single dose every other day is most efficient in those with iron deficiency without anemia. Since study participants did not have anemia, research is pending on whether different strategies (such as daily dosing) are more effective for more severe cases. The bottom line is that conventional high-dose divided daily oral iron administration results in reduced iron bioavailability compared with alternate-day dosing.

Increasing dietary iron is insufficient to treat low iron storage, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. Likewise, multivitamins, which contain very little elemental iron, are not recommended for repletion. Any iron salt with 60 to 120 mg of elemental iron can be used (for examples, ferrous sulfate, ferrous gluconate).25 Once ingested, stomach and pancreatic acids release elemental iron from its bound form. For that reason, absorption may be improved by administering iron at least 1 hour before a meal and avoiding antacids, including milk. Meat proteins and ascorbic acid help maintain the soluble ferrous form and also aid absorption. Tea, coffee, and tannins prevent absorption when polyphenol compounds form an insoluble complex with iron (see box at end of article). Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be minimized by decreasing the dose and taking after meals, although with reduced efficacy.

Intravenous iron treatment raises hemoglobin levels significantly faster than oral administration but is limited by cost and availability, so it is reserved for individuals with a hemoglobin level less than 9 g/dL, prior gastrointestinal or bariatric surgery, imminent surgery, and intolerance, poor adherence, or nonresponse to oral iron therapy. Several approved formulations are available, all with equivalent effectiveness and similar safety profiles. Lower-dose formulations (such as iron sucrose) may require several infusions, but higher-dose intravenous iron products (ferric carboxymaltose, low-molecular weight iron dextran, etc) have a stable carbohydrate shell that inhibits free iron release and improves safety, allowing a single administration.26

Common adverse effects of intravenous iron treatment include a metallic taste and headache during administration. More serious adverse effects, such as hypotension, arthralgia, malaise, and nausea, are usually self-limited. With mild infusion reactions (1 in 200), the infusion can be stopped until symptoms improve and can be resumed at a slower rate.27

Continue to: The role of blood transfusion...

The role of blood transfusion

Blood transfusion is expensive and potentially hazardous, so its use is limited to treatment of acute blood loss or severe anemia.

A one-time red blood cell transfusion does not impact diagnostic criteria to assess for iron deficiency with ferritin, and it does not improve underlying iron deficiency.28 Patients with acute blood loss anemia superimposed on chronic blood loss should be screened and treated for iron deficiency even after receiving a transfusion.

Since ferritin levels can rise significantly as an acute phase reactant, even following a hemorrhage, iron deficiency during inflammation is defined as ferritin less than 70 ng/mL.

The potential for iron overload

Since iron is never metabolized or excreted, it is possible to have iron overload following accidental overdose, transfusion dependency, and disorders of iron transport, such as hemochromatosis and thalassemia.

While a low ferritin level always indicates iron deficiency, high ferritin levels can be an acute phase reactant. Ferritin levels greater than 150 ng/mL in healthy menstruating individuals and greater than 500 ng/mL in unhealthy individuals should raise concern for excess iron and should prompt discontinuation of iron intake or workup for conditions at risk for overload.5

Oral iron supplements should be stored away from small children, who are at particular risk of toxicity.

How long to treat?

Treatment duration depends on the individual’s degree of iron deficiency, whether anemia is present, and the amount of ongoing blood loss. The main treatment goal is normalization and maintenance of serum ferritin.

Successful treatment should be confirmed with a complete blood count and ferritin level. Hemoglobin levels improve 2 g/dL after 3 weeks of oral iron therapy, but repletion may take 4 to 6 months.23,29 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends 3 to 6 months of continued iron therapy after resolution of HMB.19

In a comparative study of treatment for HMB with the 52-mg LNG IUD versus hysterectomy, hemoglobin levels increased in both treatment groups but stayed lower in those with initial anemia.8 Ferritin levels normalized only after 5 years and were still lower in individuals with initial anemia.

Increase in hemoglobin is faster after intravenous iron administration but is equivalent to oral therapy by 12 weeks. If management to reduce menstrual losses is discontinued, periodic or maintenance iron repletion will be necessary.

CASE Management plan initiated

This 17-year-old patient with iron deficiency resulting from HMB requests management to reduce menstrual iron losses with a preference for predictable menses. We have already completed a basic workup, which could also include assessment for hypermobility with a Beighton score, as connective tissue disorders also are associated with HMB.30 We discuss the options of cyclic hormonal therapy, antifibrinolytic treatment, and an LNG IUD. The patient is concerned about adherence and wants to avoid unscheduled bleeding, so she opts for a trial of tranexamic acid 1,300 mg 3 times daily for 5 days during menses. This regimen results in a 50% reduction in bleeding amount, which the patient finds satisfactory. Iron repletion with oral ferrous sulfate 325 mg (containing 65 mg of elemental iron) is administered on alternating days with vitamin C taken 1 hour prior to dinner. Repeat laboratory test results at 3 weeks show improvement to a hemoglobin level of 14.2 g/dL and a ferritin level of 12 ng/mL. By 3 months, her ferritin levels are greater than 30 ng/mL and oral iron is administered only during menses.

Summing up

Chronic HMB results in a progressive net loss of iron and eventual anemia. Screening with complete blood count and ferritin and early treatment of low iron storage when ferritin is less than 30 ng/mL will help avoid symptoms. Any amount of reduction of menstrual blood loss can be beneficial, allowing a variety of effective hormonal and nonhormonal treatment options. ●

- Take 60 to 120 mg elemental iron every other day.

- To help with absorption:

—Take 1 hour before a meal, but not with coffee, tea, tannins, antacids, or milk

—Take with vitamin C or other acidic fruit juice

- Recheck complete blood count and ferritin in 2 to 3 weeks to confirm initial response.

- Continue treatment for up to 3 to 6 months until ferritin levels are greater than 30 to 50 ng/mL.

- Munro MG, Mast AE, Powers JM, et al. The relationship between heavy menstrual bleeding, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;S00029378(23)00024-8.

- Tsakiridis I, Giouleka S, Koutsouki G, et al. Investigation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive aged women: a descriptive review of national and international recommendations. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2022;27:504-517.

- Camaschella C. Iron deficiency. Blood. 2019;133:30-39.

- Camaschella C, Nai A, Silvestri L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica. 2020;105:260-272.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on use of ferritin concentrations to assess iron status in individuals and populations. April 21, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000124

- Mei Z, Addo OY, Jefferds ME, et al. Physiologically based serum ferritin thresholds for iron deficiency in children and non-pregnant women: a US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) serial cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8: e572-e582.

- Galetti V, Stoffel NU, Sieber C, et al. Threshold ferritin and hepcidin concentrations indicating early iron deficiency in young women based on upregulation of iron absorption. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101052.

- Percy L, Mansour D, Fraser I. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:55-67.

- Brittenham GM. Short-term periods of strenuous physical activity lower iron absorption. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113:261-262.

- Chen M, Lindley A, Kimport K, et al. An in-depth analysis of the use of shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2019;99:187-191.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Dias S, Jordan V, et al. Interventions for heavy menstrual bleeding; overview of Cochrane reviews and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013180.

- Mansour D, Hofmann A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. A review of clinical guidelines on the management of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Adv Ther. 2021;38:201-225.

- Micks EA, Jensen JT. Treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding with the estradiol valerate and dienogest oral contraceptive pill. Adv Ther. 2013;30:1-13.

- Bryant-Smith AC, Lethaby A, Farquhar C, et al. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD000249.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:CD000400.

- Relke N, Chornenki NLJ, Sholzberg M. Tranexamic acid evidence and controversies: an illustrated review. Res Pract T hromb Haemost. 2021;5:e12546.

- Reid RL, Westhoff C, Mansour D, et al. Oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism consensus opinion from an international workshop held in Berlin, Germany in December 2009. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36:117-122.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:891-896.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 785: screening and management of bleeding disorders in adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e71-e83.

- Haamid F, Sass AE, Dietrich JE. Heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:335-340.

- Roth LP, Haley KM, Baldwin MK. A retrospective comparison of time to cessation of acute heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents following two dose regimens of combined oral hormonal therapy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2022;35:294-298.

- Huguelet PS, Buyers EM, Lange-Liss JH, et al. Treatment of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents: what are providers doing in various specialties? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:286-291.

- Elstrott B, Khan L, Olson S, et al. The role of iron repletion in adult iron deficiency anemia and other diseases. Eur J Haematol. 2020;104:153-161.

- Pagani A, Nai A, Silvestri L, et al. Hepcidin and anemia: a tight relationship. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1294.

- Stoffel NU, von Siebenthal HK, Moretti D, et al. Oral iron supplementation in iron-deficient women: how much and how often? Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75:100865.

- Auerbach M, Adamson JW. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:31-38.

- Dave CV, Brittenham GM, Carson JL, et al. Risks for anaphylaxis with intravenous iron formulations: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:656-664.

- Froissart A, Rossi B, Ranque B, et al; SiMFI Group. Effect of a red blood cell transfusion on biological markers used to determine the cause of anemia: a prospective study. Am J Med. 2018;131:319-322.

- Carson JL, Brittenham GM. How I treat anemia with red blood cell transfusion and iron. Blood. 2022;blood.2022018521.

- Borzutzky C, Jaffray J. Diagnosis and management of heavy menstrual bleeding and bleeding disorders in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:186-194.

- Munro MG, Mast AE, Powers JM, et al. The relationship between heavy menstrual bleeding, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency anemia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;S00029378(23)00024-8.

- Tsakiridis I, Giouleka S, Koutsouki G, et al. Investigation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive aged women: a descriptive review of national and international recommendations. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2022;27:504-517.

- Camaschella C. Iron deficiency. Blood. 2019;133:30-39.

- Camaschella C, Nai A, Silvestri L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica. 2020;105:260-272.

- World Health Organization. WHO guideline on use of ferritin concentrations to assess iron status in individuals and populations. April 21, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000124

- Mei Z, Addo OY, Jefferds ME, et al. Physiologically based serum ferritin thresholds for iron deficiency in children and non-pregnant women: a US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) serial cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8: e572-e582.

- Galetti V, Stoffel NU, Sieber C, et al. Threshold ferritin and hepcidin concentrations indicating early iron deficiency in young women based on upregulation of iron absorption. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101052.

- Percy L, Mansour D, Fraser I. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;40:55-67.

- Brittenham GM. Short-term periods of strenuous physical activity lower iron absorption. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113:261-262.

- Chen M, Lindley A, Kimport K, et al. An in-depth analysis of the use of shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2019;99:187-191.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Dias S, Jordan V, et al. Interventions for heavy menstrual bleeding; overview of Cochrane reviews and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013180.

- Mansour D, Hofmann A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. A review of clinical guidelines on the management of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Adv Ther. 2021;38:201-225.

- Micks EA, Jensen JT. Treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding with the estradiol valerate and dienogest oral contraceptive pill. Adv Ther. 2013;30:1-13.

- Bryant-Smith AC, Lethaby A, Farquhar C, et al. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4:CD000249.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Lethaby A, Farquhar C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:CD000400.

- Relke N, Chornenki NLJ, Sholzberg M. Tranexamic acid evidence and controversies: an illustrated review. Res Pract T hromb Haemost. 2021;5:e12546.

- Reid RL, Westhoff C, Mansour D, et al. Oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism consensus opinion from an international workshop held in Berlin, Germany in December 2009. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36:117-122.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:891-896.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 785: screening and management of bleeding disorders in adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e71-e83.

- Haamid F, Sass AE, Dietrich JE. Heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:335-340.

- Roth LP, Haley KM, Baldwin MK. A retrospective comparison of time to cessation of acute heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents following two dose regimens of combined oral hormonal therapy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2022;35:294-298.

- Huguelet PS, Buyers EM, Lange-Liss JH, et al. Treatment of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents: what are providers doing in various specialties? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:286-291.

- Elstrott B, Khan L, Olson S, et al. The role of iron repletion in adult iron deficiency anemia and other diseases. Eur J Haematol. 2020;104:153-161.

- Pagani A, Nai A, Silvestri L, et al. Hepcidin and anemia: a tight relationship. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1294.

- Stoffel NU, von Siebenthal HK, Moretti D, et al. Oral iron supplementation in iron-deficient women: how much and how often? Mol Aspects Med. 2020;75:100865.

- Auerbach M, Adamson JW. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:31-38.

- Dave CV, Brittenham GM, Carson JL, et al. Risks for anaphylaxis with intravenous iron formulations: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:656-664.

- Froissart A, Rossi B, Ranque B, et al; SiMFI Group. Effect of a red blood cell transfusion on biological markers used to determine the cause of anemia: a prospective study. Am J Med. 2018;131:319-322.

- Carson JL, Brittenham GM. How I treat anemia with red blood cell transfusion and iron. Blood. 2022;blood.2022018521.

- Borzutzky C, Jaffray J. Diagnosis and management of heavy menstrual bleeding and bleeding disorders in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:186-194.

CSU in children: Study identifies biomarkers associated with responses to different treatments

NEW ORLEANS – , results from a single-center prospective study showed.

“Given that the majority of CSU cases in adults are due to autoimmunity and there being very [few] studies on biomarkers for CSU in children, our study furthers our current understanding of the role of different biomarkers in treatment response,” lead study author Alex Nguyen, MsC, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during a poster session.

To identify biomarkers with treatment and disease resolution in children with CSU, Mr. Nguyen, a 4-year medical student at McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues prospectively recruited 109 children from the Montreal Children’s Hospital Allergy and Immunology Clinic who reported hives for at least 6 weeks from 2013 to 2022. They obtained levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), anti-thyroxine peroxidase (anti-TPO), total immunoglobulin E (IgE), CD63, tryptase, eosinophils, MPV, and platelets; the weekly urticaria activity score (UAS7) was recorded at study entry.

Levels of treatment included antihistamines at standard dose, four times the standard dose, omalizumab, and resolution of treatment. The researchers used univariate and multivariate logistic regressions to determine factors associated with different treatment levels and resolution.

Slightly more than half of the study participants (55%) were female, and their mean age was 9 years. Mr. Nguyen and colleagues observed that elevated MPV was associated with the four times increased dose of antihistamines treatment level (odds ratio = 1.052, 95% confidence interval = 1.004-1.103). Lower age was associated with disease resolution (OR = 0.982, 95% CI = 0.965-0.999).

After adjustment for age, sex, TSH, anti-TPO, total IgE, CD63, eosinophils, MPV, and platelets, elevated tryptase was associated with the antihistamine use at standard dose level (OR = 1.152, 95% CI = 1.019-1.302) and lower tryptase levels with disease resolution (OR = .861, 95% CI = 0.777-0.955).

“We were fascinated when we found that tryptase levels in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria were associated with standard dose of antihistamines and even disease resolution,” Mr. Nguyen said. “Higher tryptase levels were associated with standard dose antihistamines, which potentially could imply an increase in mast cell activation. Furthermore, we saw that lower tryptase levels were associated with disease resolution likely given if the disease may not have been as severe.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including a limited sample size and an unbalanced sample size among treatment groups. In the future, he and his colleagues plan to increase the sample size and to include other biomarkers such as interleukin (IL)-6, D-dimer, vitamin D, and matrix mettaloproteinase-9.

“Much as the name suggests, CSU often arises without a clear trigger,” said Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study. “Particularly in children, little is known about potential biomarkers that may guide treatment or disease resolution. While a larger, prospective analysis would better characterize temporal trends in serum biomarkers in relation to disease activity, these data suggest that underlying mechanisms of tryptase may be worth an in-depth look in children with CSU.”

The study was recognized as the second-best poster at the meeting. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures. The other study coauthors were Michelle Le MD, Sofianne Gabrielli MSc, Elena Netchiporouk, MD, MSc, and Moshe Ben-Shoshan, MD, MSc. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, and/or a member of the advisory board for several pharmaceutical companies.

NEW ORLEANS – , results from a single-center prospective study showed.

“Given that the majority of CSU cases in adults are due to autoimmunity and there being very [few] studies on biomarkers for CSU in children, our study furthers our current understanding of the role of different biomarkers in treatment response,” lead study author Alex Nguyen, MsC, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during a poster session.

To identify biomarkers with treatment and disease resolution in children with CSU, Mr. Nguyen, a 4-year medical student at McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues prospectively recruited 109 children from the Montreal Children’s Hospital Allergy and Immunology Clinic who reported hives for at least 6 weeks from 2013 to 2022. They obtained levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), anti-thyroxine peroxidase (anti-TPO), total immunoglobulin E (IgE), CD63, tryptase, eosinophils, MPV, and platelets; the weekly urticaria activity score (UAS7) was recorded at study entry.

Levels of treatment included antihistamines at standard dose, four times the standard dose, omalizumab, and resolution of treatment. The researchers used univariate and multivariate logistic regressions to determine factors associated with different treatment levels and resolution.

Slightly more than half of the study participants (55%) were female, and their mean age was 9 years. Mr. Nguyen and colleagues observed that elevated MPV was associated with the four times increased dose of antihistamines treatment level (odds ratio = 1.052, 95% confidence interval = 1.004-1.103). Lower age was associated with disease resolution (OR = 0.982, 95% CI = 0.965-0.999).

After adjustment for age, sex, TSH, anti-TPO, total IgE, CD63, eosinophils, MPV, and platelets, elevated tryptase was associated with the antihistamine use at standard dose level (OR = 1.152, 95% CI = 1.019-1.302) and lower tryptase levels with disease resolution (OR = .861, 95% CI = 0.777-0.955).

“We were fascinated when we found that tryptase levels in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria were associated with standard dose of antihistamines and even disease resolution,” Mr. Nguyen said. “Higher tryptase levels were associated with standard dose antihistamines, which potentially could imply an increase in mast cell activation. Furthermore, we saw that lower tryptase levels were associated with disease resolution likely given if the disease may not have been as severe.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including a limited sample size and an unbalanced sample size among treatment groups. In the future, he and his colleagues plan to increase the sample size and to include other biomarkers such as interleukin (IL)-6, D-dimer, vitamin D, and matrix mettaloproteinase-9.

“Much as the name suggests, CSU often arises without a clear trigger,” said Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study. “Particularly in children, little is known about potential biomarkers that may guide treatment or disease resolution. While a larger, prospective analysis would better characterize temporal trends in serum biomarkers in relation to disease activity, these data suggest that underlying mechanisms of tryptase may be worth an in-depth look in children with CSU.”

The study was recognized as the second-best poster at the meeting. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures. The other study coauthors were Michelle Le MD, Sofianne Gabrielli MSc, Elena Netchiporouk, MD, MSc, and Moshe Ben-Shoshan, MD, MSc. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, and/or a member of the advisory board for several pharmaceutical companies.

NEW ORLEANS – , results from a single-center prospective study showed.

“Given that the majority of CSU cases in adults are due to autoimmunity and there being very [few] studies on biomarkers for CSU in children, our study furthers our current understanding of the role of different biomarkers in treatment response,” lead study author Alex Nguyen, MsC, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, where the study was presented during a poster session.

To identify biomarkers with treatment and disease resolution in children with CSU, Mr. Nguyen, a 4-year medical student at McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues prospectively recruited 109 children from the Montreal Children’s Hospital Allergy and Immunology Clinic who reported hives for at least 6 weeks from 2013 to 2022. They obtained levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), anti-thyroxine peroxidase (anti-TPO), total immunoglobulin E (IgE), CD63, tryptase, eosinophils, MPV, and platelets; the weekly urticaria activity score (UAS7) was recorded at study entry.

Levels of treatment included antihistamines at standard dose, four times the standard dose, omalizumab, and resolution of treatment. The researchers used univariate and multivariate logistic regressions to determine factors associated with different treatment levels and resolution.

Slightly more than half of the study participants (55%) were female, and their mean age was 9 years. Mr. Nguyen and colleagues observed that elevated MPV was associated with the four times increased dose of antihistamines treatment level (odds ratio = 1.052, 95% confidence interval = 1.004-1.103). Lower age was associated with disease resolution (OR = 0.982, 95% CI = 0.965-0.999).

After adjustment for age, sex, TSH, anti-TPO, total IgE, CD63, eosinophils, MPV, and platelets, elevated tryptase was associated with the antihistamine use at standard dose level (OR = 1.152, 95% CI = 1.019-1.302) and lower tryptase levels with disease resolution (OR = .861, 95% CI = 0.777-0.955).

“We were fascinated when we found that tryptase levels in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria were associated with standard dose of antihistamines and even disease resolution,” Mr. Nguyen said. “Higher tryptase levels were associated with standard dose antihistamines, which potentially could imply an increase in mast cell activation. Furthermore, we saw that lower tryptase levels were associated with disease resolution likely given if the disease may not have been as severe.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including a limited sample size and an unbalanced sample size among treatment groups. In the future, he and his colleagues plan to increase the sample size and to include other biomarkers such as interleukin (IL)-6, D-dimer, vitamin D, and matrix mettaloproteinase-9.

“Much as the name suggests, CSU often arises without a clear trigger,” said Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study. “Particularly in children, little is known about potential biomarkers that may guide treatment or disease resolution. While a larger, prospective analysis would better characterize temporal trends in serum biomarkers in relation to disease activity, these data suggest that underlying mechanisms of tryptase may be worth an in-depth look in children with CSU.”

The study was recognized as the second-best poster at the meeting. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures. The other study coauthors were Michelle Le MD, Sofianne Gabrielli MSc, Elena Netchiporouk, MD, MSc, and Moshe Ben-Shoshan, MD, MSc. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, and/or a member of the advisory board for several pharmaceutical companies.

AT AAD 2023

JAK inhibitor safety warnings drawn from rheumatologic data may be misleading in dermatology

NEW ORLEANS – , even though the basis for all the risks is a rheumatoid arthritis study, according to a critical review at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Given the fact that the postmarketing RA study was specifically enriched with high-risk patients by requiring an age at enrollment of at least 50 years and the presence of at least one cardiovascular risk factor, the extrapolation of these risks to dermatologic indications is “not necessarily data-driven,” said Brett A. King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The recently approved deucravacitinib is the only JAK inhibitor that has so far been exempt from these warnings. Instead, based on the ORAL Surveillance study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the Food and Drug Administration requires a boxed warning in nearly identical language for all the other JAK inhibitors. Relative to tofacitinib, the JAK inhibitor tested in ORAL Surveillance, many of these drugs differ by JAK selectivity and other characteristics that are likely relevant to risk of adverse events, Dr. King said. The same language has even been applied to topical ruxolitinib cream.

Basis of boxed warnings

In ORAL Surveillance, about 4,300 high-risk patients with RA were randomized to one of two doses of tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg) twice daily or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. All patients in the trial were taking methotrexate, and almost 60% were taking concomitant corticosteroids. The average body mass index of the study population was about 30 kg/m2.

After a median 4 years of follow-up (about 5,000 patient-years), the incidence of many of the adverse events tracked in the study were higher in the tofacitinib groups, including serious infections, MACE, thromboembolic events, and cancer. Dr. King did not challenge the importance of these data, but he questioned whether they are reasonably extrapolated to dermatologic indications, particularly as many of those treated are younger than those common to an RA population.