User login

Melasma Risk Factors: A Matched Cohort Study Using Data From the All of Us Research Program

To the Editor:

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is characterized by symmetric hyperpigmented patches affecting sun-exposed areas. Women commonly develop this condition during pregnancy, suggesting a connection between melasma and increased female sex hormone levels.1 Other hypothesized risk factors include sun exposure, genetic susceptibility, estrogen and/or progesterone therapy, and thyroid abnormalities but have not been corroborated.2 Treatment options are limited because the pathogenesis is poorly understood; thus, we aimed to analyze melasma risk factors using a national database with a nested case-control approach.

We conducted a matched case-control study using the Registered Tier dataset (version 7) from the National Institute of Health’s All of Us Research Program (https://allofus.nih.gov/), which is available to authorized users through the program’s Researcher Workbench and includes more than 413,000 total participants enrolled from May 1, 2018, through July 1, 2022. Cases included patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of melasma (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification code L81.1 [Chloasma]; concept ID 4264234 [Chloasma]; and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine [SNOMED] code 36209000 [Chloasma]), and controls without a diagnosis of melasma were matched in a 1:10 ratio based on age, sex, and self-reported race. Concept IDs and SNOMED codes were used to identify individuals in each cohort with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (concept IDs 433753, 435243, 4218106; SNOMED codes 15167005, 66590003, 7200002), depression (concept ID 440383; SNOMED code 35489007), hypothyroidism (concept ID 140673; SNOMED code 40930008), hyperthyroidism (concept ID 4142479; SNOMED code 34486009), anxiety (concept IDs 441542, 442077, 434613; SNOMED codes 48694002, 197480006, 21897009), tobacco dependence (concept IDs 37109023, 437264, 4099811; SNOMED codes 16077091000119107, 89765005, 191887008), or obesity (concept IDs 433736 and 434005; SNOMED codes 414916001 and 238136002), or with a history of radiation therapy (concept IDs 4085340, 4311117, 4061844, 4029715; SNOMED codes 24803000, 85983004, 200861004, 108290001) or hormonal medications containing estrogen and/or progesterone, including oral medications and implants (concept IDs 21602445, 40254009, 21602514, 21603814, 19049228, 21602529, 1549080, 1551673, 1549254, 21602472, 21602446, 21602450, 21602515, 21602566, 21602473, 21602567, 21602488, 21602585, 1596779, 1586808, 21602524). In our case cohort, diagnoses and exposures to treatments were only considered for analysis if they occurred prior to melasma diagnosis.

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios and P values between melasma and each comorbidity or exposure to the treatments specified. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

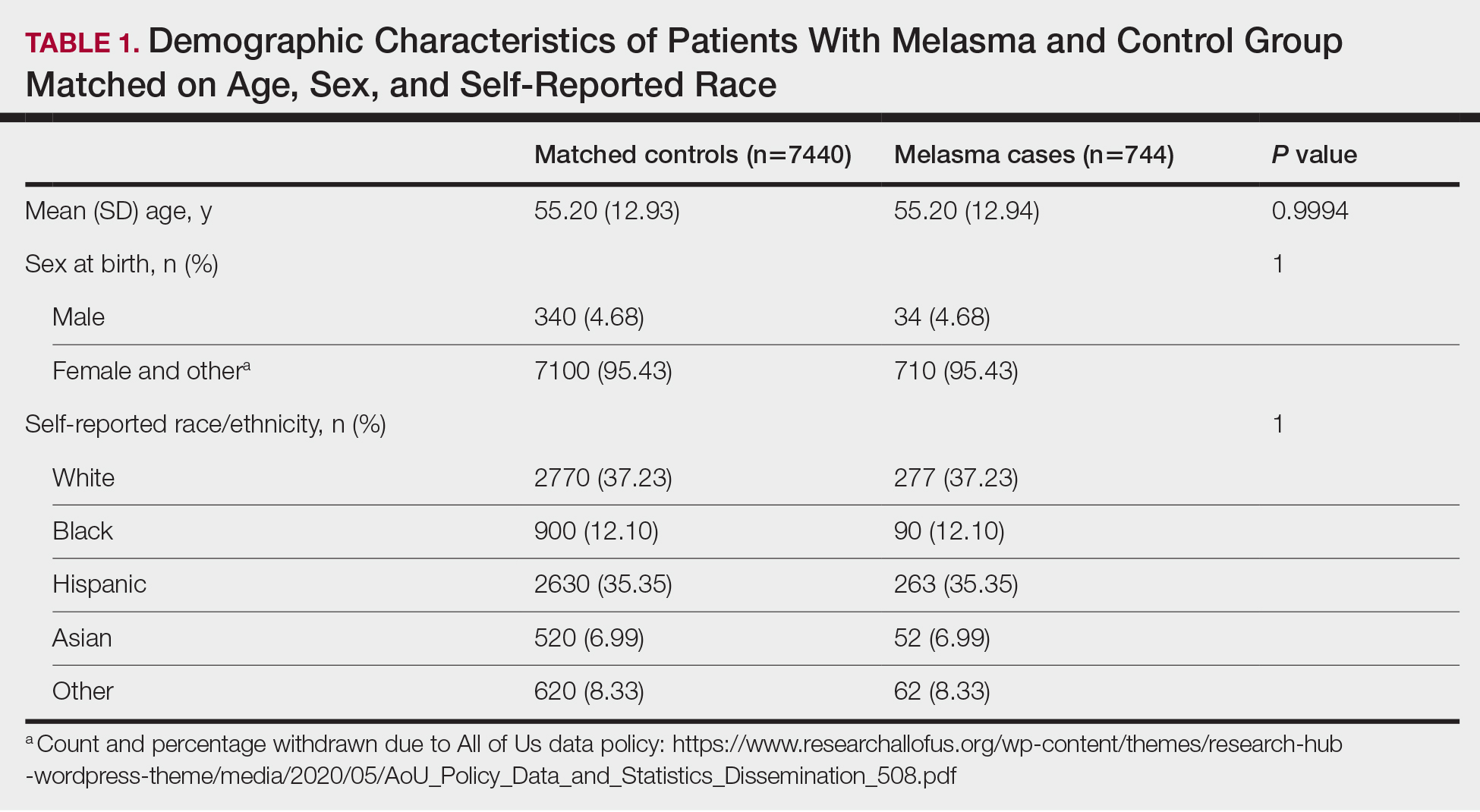

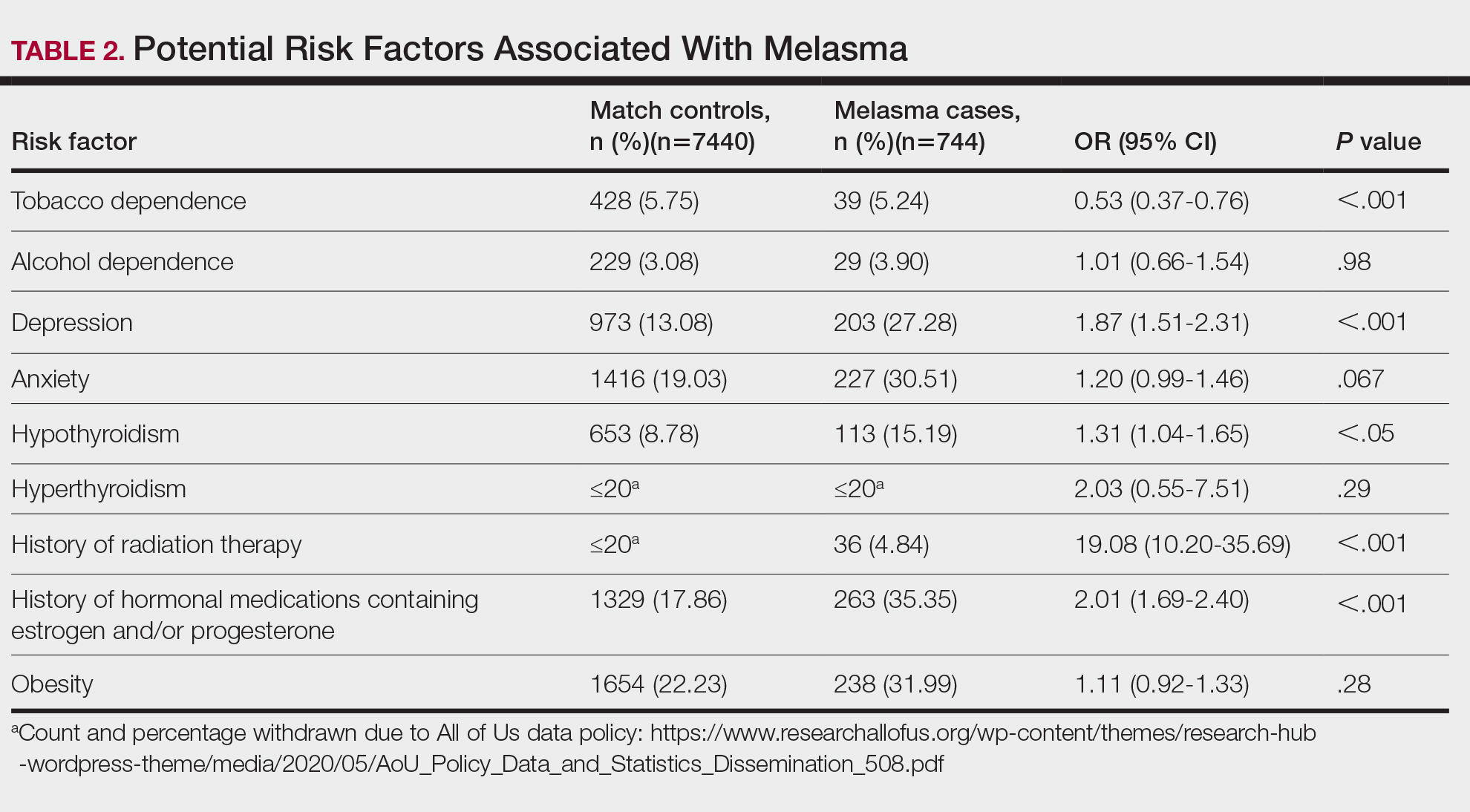

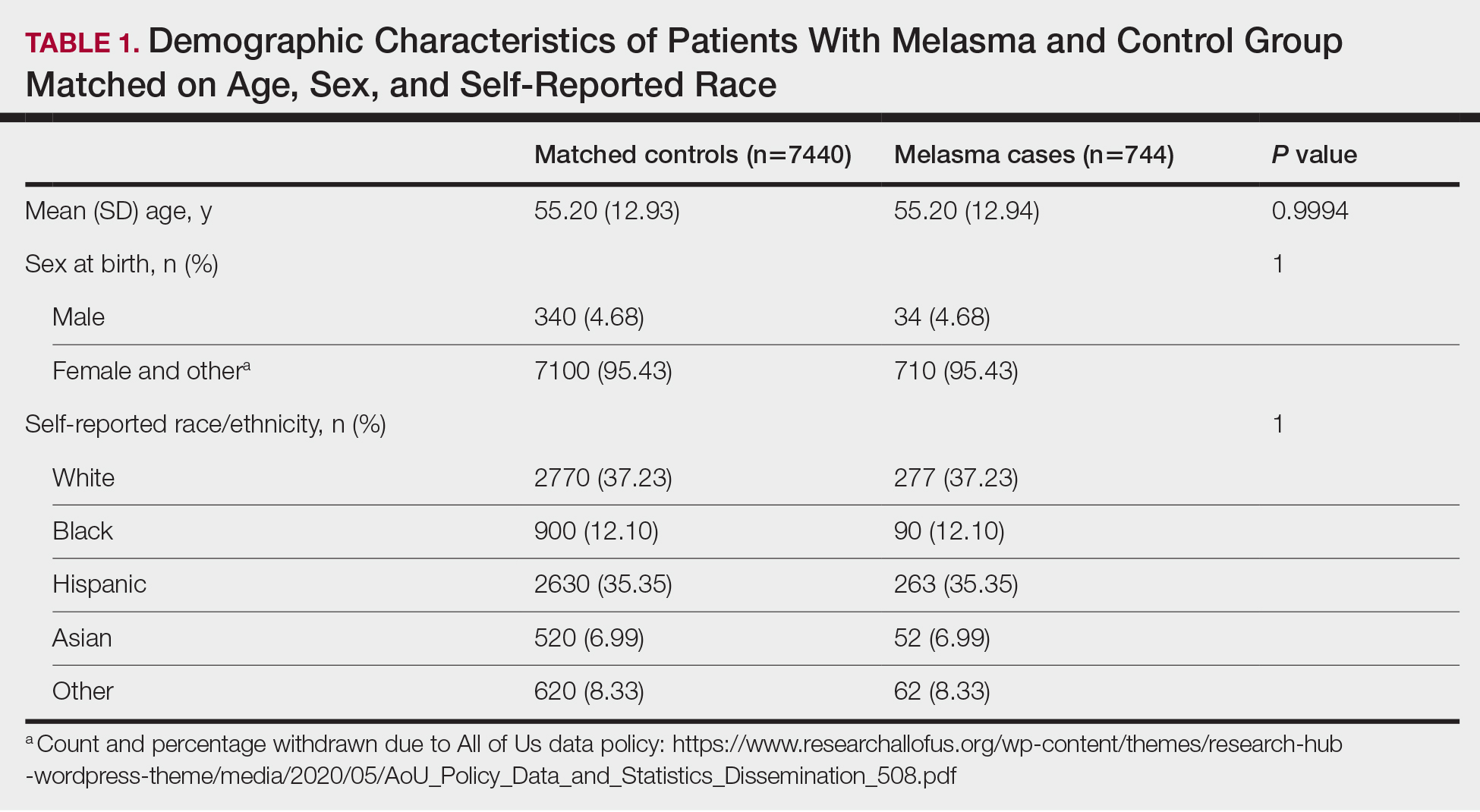

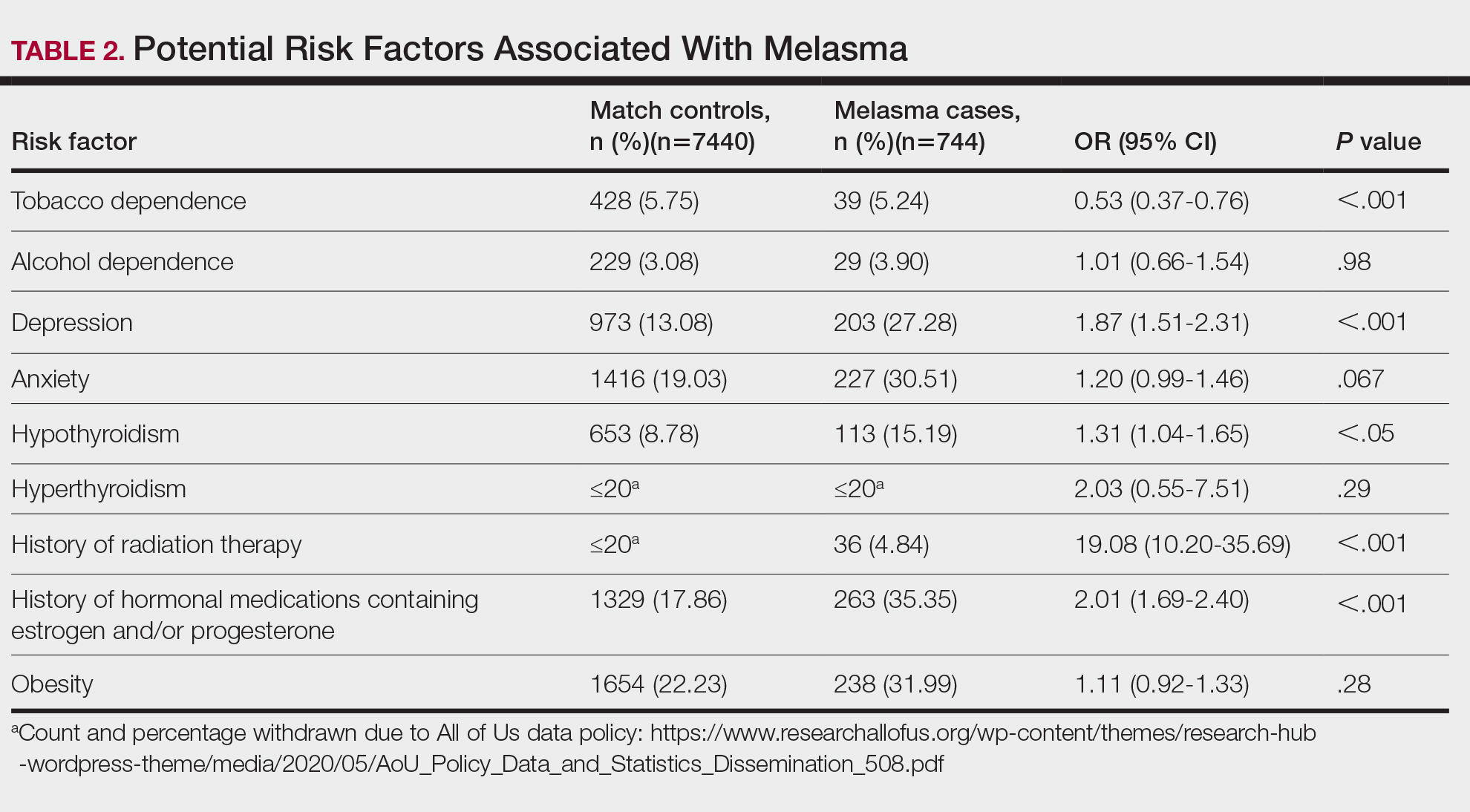

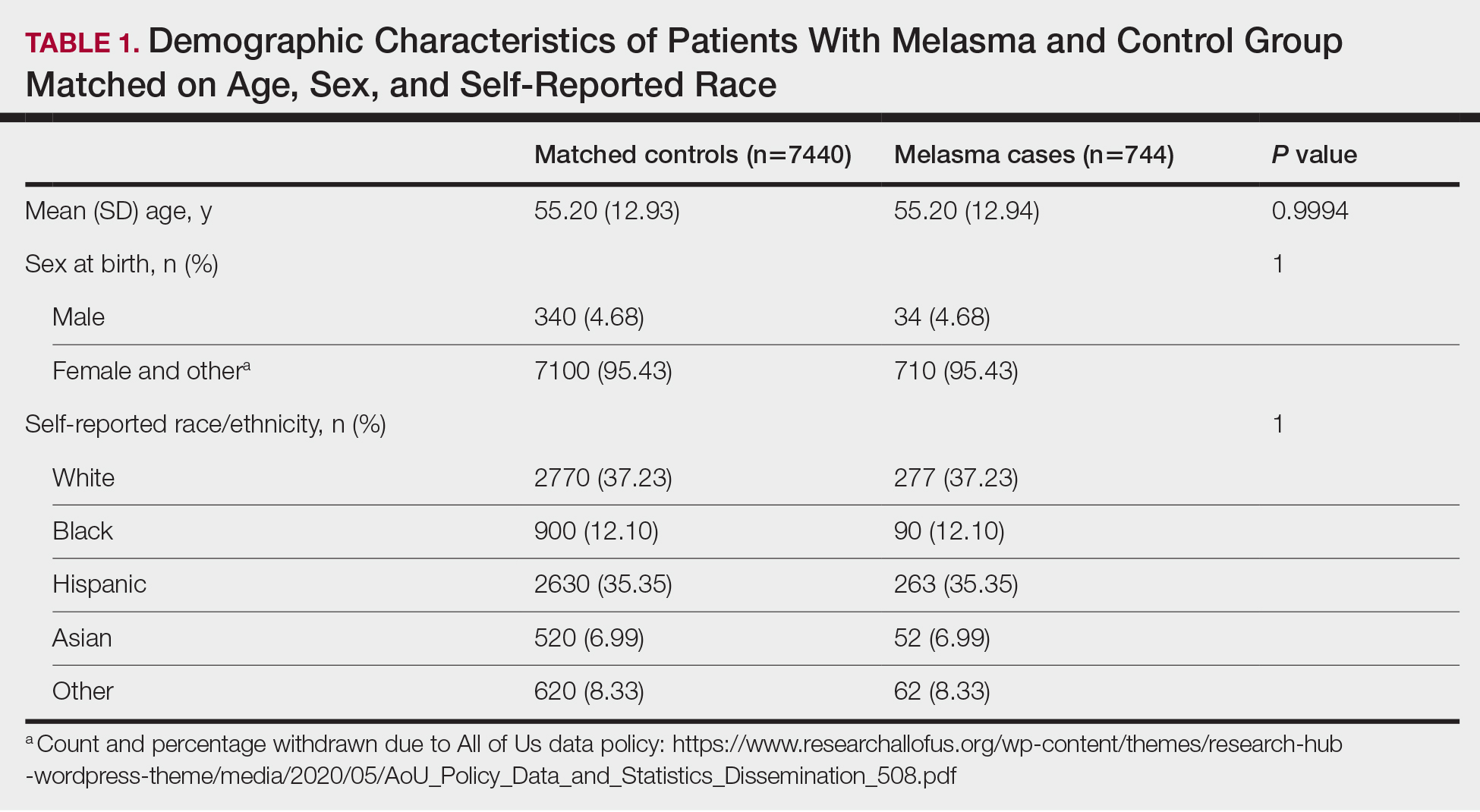

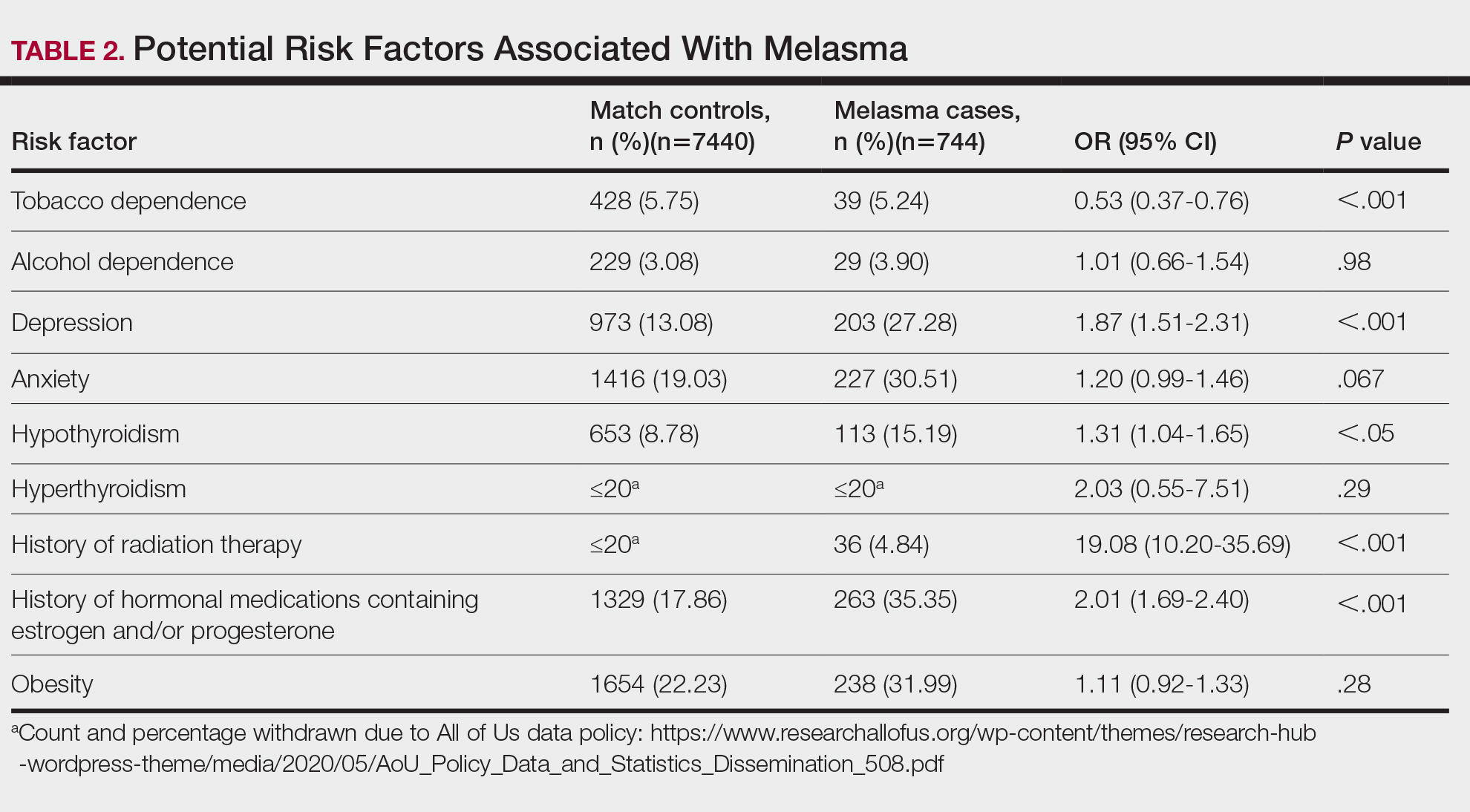

We identified 744 melasma cases (mean age, 55.20 years; 95.43% female; 12.10% Black) and 7440 controls with similar demographics (ie, age, sex, race/ethnicity) between groups (all P>.05 [Table 1]). Patients with a melasma diagnosis were more likely to have a pre-existing diagnosis of depression (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.51-2.31 [P<.001]) or hypothyroidism (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.04-1.65 [P<.05]), or a history of radiation therapy (OR, 19.08; 95% CI, 10.20-35.69 [P<.001]) and/or estrogen and/or progesterone therapy (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.69-2.40 [P<.001]) prior to melasma diagnosis. A diagnosis of anxiety prior to melasma diagnosis trended toward an association with melasma (P=.067). Pre-existing alcohol dependence, obesity, and hyperthyroidism were not associated with melasma (P=.98, P=.28, and P=.29, respectively). A diagnosis of tobacco dependence was associated with a decreased melasma risk (OR, 0.53, 95% CI, 0.37-0.76)[P<.001])(Table 2).

Our study results suggest that pre-existing depression was a risk factor for subsequent melasma diagnosis. Depression may exacerbate stress, leading to increased activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis as well as increased levels of cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone, which subsequently act on melanocytes to increase melanogenesis.3 A retrospective study of 254 participants, including 127 with melasma, showed that increased melasma severity was associated with higher rates of depression (P=.002)2; however, the risk for melasma following a depression diagnosis has not been reported.

Our results also showed that hypothyroidism was associated with an increased risk for melasma. On a cellular level, hypothyroidism can cause systemic inflammation, potentailly leading to increased stress and melanogenesis via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4 These findings are similar to a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting increased thyroid-stimulating hormone, anti–thyroid peroxidase, and antithyroglobulin antibody levels associated with increased melasma risk (mean difference between cases and controls, 0.33 [95% CI, 0.18-0.47]; pooled association, P=.020; mean difference between cases and controls, 0.28 [95% CI, 0.01-0.55], respectively).5

Patients in our cohort who had a history of radiation therapy were 19 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to findings of a survey-based study of 421 breast cancer survivors in which 336 (79.81%) reported hyperpigmentation in irradiated areas.6 Patients in our cohort who had a history of estrogen and/or progesterone therapy were 2 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to a case-control study of 207 patients with melasma and 207 controls that showed combined oral contraceptives increased risk for melasma (OR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.08-1.41; P<.01).3

Tobacco use is not a well-known protective factor against melasma. Prior studies have indicated that tobacco smoking activates melanocytes via the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, leading to hyperpigmentation.7 Although exposure to cigarette smoke decreases angiogenesis and would more likely lead to hyperpigmentation, nicotine exposure has been shown to increase angiogenesis, which could lead to increased blood flow and partially explain the protection against melasma demonstrated in our cohort.8 Future studies are needed to explore this relationship.

Limitations of our study include lack of information about melasma severity and information about prior melasma treatment in our cohort as well as possible misdiagnosis reported in the dataset.

Our results demonstrated that pre-existing depression and hypothyroidism as well as a history of radiation or estrogen and/or progesterone therapies are potential risk factors for melasma. Therefore, we recommend that patients with melasma be screened for depression and thyroid dysfunction, and patients undergoing radiation therapy or starting estrogen and/or progesterone therapy should be counseled on their increased risk for melasma. Future studies are needed to determine whether treatment of comorbidities such as hypothyroidism and depression improve melasma severity. The decreased risk for melasma associated with tobacco use also requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments—The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA #: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; The Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276.

In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants, who we gratefully acknowledge for their contributions and without whom this research would not have been possible. We also thank the All of Us Research Program for making the participant data examined in this study available to us.

- Filoni A, Mariano M, Cameli N. Melasma: how hormones can modulate skin pigmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:458-463. doi:10.1111/jocd.12877

- Platsidaki E, Efstathiou V, Markantoni V, et al. Self-esteem, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with melasma living in a sunny mediterranean area: results from a prospective cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:1127-1136. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-00915-1

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, et al. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588-594. doi:10.1111/bjd.13059

- Erge E, Kiziltunc C, Balci SB, et al. A novel inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: platelet-count-to-lymphocyte-count ratio (published January 22, 2023). Diseases. 2023;11:15. doi:10.3390/diseases11010015

- Kheradmand M, Afshari M, Damiani G, et al. Melasma and thyroid disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1231-1238. doi:10.1111/ijd.14497

- Chu CN, Hu KC, Wu RS, et al. Radiation-irritated skin and hyperpigmentation may impact the quality of life of breast cancer patients after whole breast radiotherapy (published March 31, 2021). BMC Cancer. 2021;21:330. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08047-5

- Nakamura M, Ueda Y, Hayashi M, et al. Tobacco smoke-induced skin pigmentation is mediated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:556-558. doi:10.1111/exd.12170

- Ejaz S, Lim CW. Toxicological overview of cigarette smoking on angiogenesis. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:335-344. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2005.03.011

To the Editor:

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is characterized by symmetric hyperpigmented patches affecting sun-exposed areas. Women commonly develop this condition during pregnancy, suggesting a connection between melasma and increased female sex hormone levels.1 Other hypothesized risk factors include sun exposure, genetic susceptibility, estrogen and/or progesterone therapy, and thyroid abnormalities but have not been corroborated.2 Treatment options are limited because the pathogenesis is poorly understood; thus, we aimed to analyze melasma risk factors using a national database with a nested case-control approach.

We conducted a matched case-control study using the Registered Tier dataset (version 7) from the National Institute of Health’s All of Us Research Program (https://allofus.nih.gov/), which is available to authorized users through the program’s Researcher Workbench and includes more than 413,000 total participants enrolled from May 1, 2018, through July 1, 2022. Cases included patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of melasma (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification code L81.1 [Chloasma]; concept ID 4264234 [Chloasma]; and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine [SNOMED] code 36209000 [Chloasma]), and controls without a diagnosis of melasma were matched in a 1:10 ratio based on age, sex, and self-reported race. Concept IDs and SNOMED codes were used to identify individuals in each cohort with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (concept IDs 433753, 435243, 4218106; SNOMED codes 15167005, 66590003, 7200002), depression (concept ID 440383; SNOMED code 35489007), hypothyroidism (concept ID 140673; SNOMED code 40930008), hyperthyroidism (concept ID 4142479; SNOMED code 34486009), anxiety (concept IDs 441542, 442077, 434613; SNOMED codes 48694002, 197480006, 21897009), tobacco dependence (concept IDs 37109023, 437264, 4099811; SNOMED codes 16077091000119107, 89765005, 191887008), or obesity (concept IDs 433736 and 434005; SNOMED codes 414916001 and 238136002), or with a history of radiation therapy (concept IDs 4085340, 4311117, 4061844, 4029715; SNOMED codes 24803000, 85983004, 200861004, 108290001) or hormonal medications containing estrogen and/or progesterone, including oral medications and implants (concept IDs 21602445, 40254009, 21602514, 21603814, 19049228, 21602529, 1549080, 1551673, 1549254, 21602472, 21602446, 21602450, 21602515, 21602566, 21602473, 21602567, 21602488, 21602585, 1596779, 1586808, 21602524). In our case cohort, diagnoses and exposures to treatments were only considered for analysis if they occurred prior to melasma diagnosis.

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios and P values between melasma and each comorbidity or exposure to the treatments specified. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

We identified 744 melasma cases (mean age, 55.20 years; 95.43% female; 12.10% Black) and 7440 controls with similar demographics (ie, age, sex, race/ethnicity) between groups (all P>.05 [Table 1]). Patients with a melasma diagnosis were more likely to have a pre-existing diagnosis of depression (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.51-2.31 [P<.001]) or hypothyroidism (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.04-1.65 [P<.05]), or a history of radiation therapy (OR, 19.08; 95% CI, 10.20-35.69 [P<.001]) and/or estrogen and/or progesterone therapy (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.69-2.40 [P<.001]) prior to melasma diagnosis. A diagnosis of anxiety prior to melasma diagnosis trended toward an association with melasma (P=.067). Pre-existing alcohol dependence, obesity, and hyperthyroidism were not associated with melasma (P=.98, P=.28, and P=.29, respectively). A diagnosis of tobacco dependence was associated with a decreased melasma risk (OR, 0.53, 95% CI, 0.37-0.76)[P<.001])(Table 2).

Our study results suggest that pre-existing depression was a risk factor for subsequent melasma diagnosis. Depression may exacerbate stress, leading to increased activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis as well as increased levels of cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone, which subsequently act on melanocytes to increase melanogenesis.3 A retrospective study of 254 participants, including 127 with melasma, showed that increased melasma severity was associated with higher rates of depression (P=.002)2; however, the risk for melasma following a depression diagnosis has not been reported.

Our results also showed that hypothyroidism was associated with an increased risk for melasma. On a cellular level, hypothyroidism can cause systemic inflammation, potentailly leading to increased stress and melanogenesis via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4 These findings are similar to a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting increased thyroid-stimulating hormone, anti–thyroid peroxidase, and antithyroglobulin antibody levels associated with increased melasma risk (mean difference between cases and controls, 0.33 [95% CI, 0.18-0.47]; pooled association, P=.020; mean difference between cases and controls, 0.28 [95% CI, 0.01-0.55], respectively).5

Patients in our cohort who had a history of radiation therapy were 19 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to findings of a survey-based study of 421 breast cancer survivors in which 336 (79.81%) reported hyperpigmentation in irradiated areas.6 Patients in our cohort who had a history of estrogen and/or progesterone therapy were 2 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to a case-control study of 207 patients with melasma and 207 controls that showed combined oral contraceptives increased risk for melasma (OR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.08-1.41; P<.01).3

Tobacco use is not a well-known protective factor against melasma. Prior studies have indicated that tobacco smoking activates melanocytes via the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, leading to hyperpigmentation.7 Although exposure to cigarette smoke decreases angiogenesis and would more likely lead to hyperpigmentation, nicotine exposure has been shown to increase angiogenesis, which could lead to increased blood flow and partially explain the protection against melasma demonstrated in our cohort.8 Future studies are needed to explore this relationship.

Limitations of our study include lack of information about melasma severity and information about prior melasma treatment in our cohort as well as possible misdiagnosis reported in the dataset.

Our results demonstrated that pre-existing depression and hypothyroidism as well as a history of radiation or estrogen and/or progesterone therapies are potential risk factors for melasma. Therefore, we recommend that patients with melasma be screened for depression and thyroid dysfunction, and patients undergoing radiation therapy or starting estrogen and/or progesterone therapy should be counseled on their increased risk for melasma. Future studies are needed to determine whether treatment of comorbidities such as hypothyroidism and depression improve melasma severity. The decreased risk for melasma associated with tobacco use also requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments—The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA #: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; The Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276.

In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants, who we gratefully acknowledge for their contributions and without whom this research would not have been possible. We also thank the All of Us Research Program for making the participant data examined in this study available to us.

To the Editor:

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is characterized by symmetric hyperpigmented patches affecting sun-exposed areas. Women commonly develop this condition during pregnancy, suggesting a connection between melasma and increased female sex hormone levels.1 Other hypothesized risk factors include sun exposure, genetic susceptibility, estrogen and/or progesterone therapy, and thyroid abnormalities but have not been corroborated.2 Treatment options are limited because the pathogenesis is poorly understood; thus, we aimed to analyze melasma risk factors using a national database with a nested case-control approach.

We conducted a matched case-control study using the Registered Tier dataset (version 7) from the National Institute of Health’s All of Us Research Program (https://allofus.nih.gov/), which is available to authorized users through the program’s Researcher Workbench and includes more than 413,000 total participants enrolled from May 1, 2018, through July 1, 2022. Cases included patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of melasma (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification code L81.1 [Chloasma]; concept ID 4264234 [Chloasma]; and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine [SNOMED] code 36209000 [Chloasma]), and controls without a diagnosis of melasma were matched in a 1:10 ratio based on age, sex, and self-reported race. Concept IDs and SNOMED codes were used to identify individuals in each cohort with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (concept IDs 433753, 435243, 4218106; SNOMED codes 15167005, 66590003, 7200002), depression (concept ID 440383; SNOMED code 35489007), hypothyroidism (concept ID 140673; SNOMED code 40930008), hyperthyroidism (concept ID 4142479; SNOMED code 34486009), anxiety (concept IDs 441542, 442077, 434613; SNOMED codes 48694002, 197480006, 21897009), tobacco dependence (concept IDs 37109023, 437264, 4099811; SNOMED codes 16077091000119107, 89765005, 191887008), or obesity (concept IDs 433736 and 434005; SNOMED codes 414916001 and 238136002), or with a history of radiation therapy (concept IDs 4085340, 4311117, 4061844, 4029715; SNOMED codes 24803000, 85983004, 200861004, 108290001) or hormonal medications containing estrogen and/or progesterone, including oral medications and implants (concept IDs 21602445, 40254009, 21602514, 21603814, 19049228, 21602529, 1549080, 1551673, 1549254, 21602472, 21602446, 21602450, 21602515, 21602566, 21602473, 21602567, 21602488, 21602585, 1596779, 1586808, 21602524). In our case cohort, diagnoses and exposures to treatments were only considered for analysis if they occurred prior to melasma diagnosis.

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios and P values between melasma and each comorbidity or exposure to the treatments specified. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

We identified 744 melasma cases (mean age, 55.20 years; 95.43% female; 12.10% Black) and 7440 controls with similar demographics (ie, age, sex, race/ethnicity) between groups (all P>.05 [Table 1]). Patients with a melasma diagnosis were more likely to have a pre-existing diagnosis of depression (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.51-2.31 [P<.001]) or hypothyroidism (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.04-1.65 [P<.05]), or a history of radiation therapy (OR, 19.08; 95% CI, 10.20-35.69 [P<.001]) and/or estrogen and/or progesterone therapy (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.69-2.40 [P<.001]) prior to melasma diagnosis. A diagnosis of anxiety prior to melasma diagnosis trended toward an association with melasma (P=.067). Pre-existing alcohol dependence, obesity, and hyperthyroidism were not associated with melasma (P=.98, P=.28, and P=.29, respectively). A diagnosis of tobacco dependence was associated with a decreased melasma risk (OR, 0.53, 95% CI, 0.37-0.76)[P<.001])(Table 2).

Our study results suggest that pre-existing depression was a risk factor for subsequent melasma diagnosis. Depression may exacerbate stress, leading to increased activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis as well as increased levels of cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone, which subsequently act on melanocytes to increase melanogenesis.3 A retrospective study of 254 participants, including 127 with melasma, showed that increased melasma severity was associated with higher rates of depression (P=.002)2; however, the risk for melasma following a depression diagnosis has not been reported.

Our results also showed that hypothyroidism was associated with an increased risk for melasma. On a cellular level, hypothyroidism can cause systemic inflammation, potentailly leading to increased stress and melanogenesis via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4 These findings are similar to a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting increased thyroid-stimulating hormone, anti–thyroid peroxidase, and antithyroglobulin antibody levels associated with increased melasma risk (mean difference between cases and controls, 0.33 [95% CI, 0.18-0.47]; pooled association, P=.020; mean difference between cases and controls, 0.28 [95% CI, 0.01-0.55], respectively).5

Patients in our cohort who had a history of radiation therapy were 19 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to findings of a survey-based study of 421 breast cancer survivors in which 336 (79.81%) reported hyperpigmentation in irradiated areas.6 Patients in our cohort who had a history of estrogen and/or progesterone therapy were 2 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to a case-control study of 207 patients with melasma and 207 controls that showed combined oral contraceptives increased risk for melasma (OR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.08-1.41; P<.01).3

Tobacco use is not a well-known protective factor against melasma. Prior studies have indicated that tobacco smoking activates melanocytes via the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, leading to hyperpigmentation.7 Although exposure to cigarette smoke decreases angiogenesis and would more likely lead to hyperpigmentation, nicotine exposure has been shown to increase angiogenesis, which could lead to increased blood flow and partially explain the protection against melasma demonstrated in our cohort.8 Future studies are needed to explore this relationship.

Limitations of our study include lack of information about melasma severity and information about prior melasma treatment in our cohort as well as possible misdiagnosis reported in the dataset.

Our results demonstrated that pre-existing depression and hypothyroidism as well as a history of radiation or estrogen and/or progesterone therapies are potential risk factors for melasma. Therefore, we recommend that patients with melasma be screened for depression and thyroid dysfunction, and patients undergoing radiation therapy or starting estrogen and/or progesterone therapy should be counseled on their increased risk for melasma. Future studies are needed to determine whether treatment of comorbidities such as hypothyroidism and depression improve melasma severity. The decreased risk for melasma associated with tobacco use also requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments—The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA #: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; The Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276.

In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants, who we gratefully acknowledge for their contributions and without whom this research would not have been possible. We also thank the All of Us Research Program for making the participant data examined in this study available to us.

- Filoni A, Mariano M, Cameli N. Melasma: how hormones can modulate skin pigmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:458-463. doi:10.1111/jocd.12877

- Platsidaki E, Efstathiou V, Markantoni V, et al. Self-esteem, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with melasma living in a sunny mediterranean area: results from a prospective cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:1127-1136. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-00915-1

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, et al. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588-594. doi:10.1111/bjd.13059

- Erge E, Kiziltunc C, Balci SB, et al. A novel inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: platelet-count-to-lymphocyte-count ratio (published January 22, 2023). Diseases. 2023;11:15. doi:10.3390/diseases11010015

- Kheradmand M, Afshari M, Damiani G, et al. Melasma and thyroid disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1231-1238. doi:10.1111/ijd.14497

- Chu CN, Hu KC, Wu RS, et al. Radiation-irritated skin and hyperpigmentation may impact the quality of life of breast cancer patients after whole breast radiotherapy (published March 31, 2021). BMC Cancer. 2021;21:330. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08047-5

- Nakamura M, Ueda Y, Hayashi M, et al. Tobacco smoke-induced skin pigmentation is mediated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:556-558. doi:10.1111/exd.12170

- Ejaz S, Lim CW. Toxicological overview of cigarette smoking on angiogenesis. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:335-344. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2005.03.011

- Filoni A, Mariano M, Cameli N. Melasma: how hormones can modulate skin pigmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:458-463. doi:10.1111/jocd.12877

- Platsidaki E, Efstathiou V, Markantoni V, et al. Self-esteem, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with melasma living in a sunny mediterranean area: results from a prospective cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:1127-1136. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-00915-1

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, et al. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588-594. doi:10.1111/bjd.13059

- Erge E, Kiziltunc C, Balci SB, et al. A novel inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: platelet-count-to-lymphocyte-count ratio (published January 22, 2023). Diseases. 2023;11:15. doi:10.3390/diseases11010015

- Kheradmand M, Afshari M, Damiani G, et al. Melasma and thyroid disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1231-1238. doi:10.1111/ijd.14497

- Chu CN, Hu KC, Wu RS, et al. Radiation-irritated skin and hyperpigmentation may impact the quality of life of breast cancer patients after whole breast radiotherapy (published March 31, 2021). BMC Cancer. 2021;21:330. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08047-5

- Nakamura M, Ueda Y, Hayashi M, et al. Tobacco smoke-induced skin pigmentation is mediated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:556-558. doi:10.1111/exd.12170

- Ejaz S, Lim CW. Toxicological overview of cigarette smoking on angiogenesis. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:335-344. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2005.03.011

Practice Points

- Treatment options for melasma are limited due to its poorly understood pathogenesis.

- Depression and hypothyroidism and/or history of exposure to radiation and hormonal therapies may increase melasma risk.

- We recommend that patients with melasma be screened for depression and thyroid dysfunction. Patients undergoing radiation therapy or starting estrogen and/ or progesterone therapy should be counseled on the increased risk for melasma.

“It Takes a Village”: Benefits and Challenges of Navigating Cancer Care with the Pacific Community and the Veterans Health Administration

Background

The Palliative Care in Hawaii/Pacific Island Communities for Veterans (PaCiHPIC Veterans) study is a VA-funded research study that explores social determinants of health, cultural values, and cancer disparities impacting Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander/US-affiliated Pacific Island resident (NHPI/USAPI) Veterans.Cancer prevalence and mortality are increasing among NHPI/ USAPI Veterans which can be partly attributed to nuclear fallout from U.S. military activities in the region. This population faces geographic, financial, and logistical barriers to cancer care. There is an imminent need to understand and address access to cancer care and palliative care to reduce disparities within this population.

Methods

We interviewed 15 clinicians including physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, and clinical psychologists specializing in primary care, palliative care, and oncology, self-identifying as White, Asian American, NHPI, and Multiracial. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and de-identified. Using inductive and deductive strategies, we iteratively collapsed content into codes formulating a codebook. Thematic analyses were performed using dual-coder review in Atlas.ti v23. Themes were mapped to the socioecological model.

Results

Clinicians described how NHPI/USAPI Veterans receive healthcare and instrumental support at individual, community, and systems levels, including from family caregivers, “high-talking chiefs,” traditional healers (“suruhanu”), community health clinics, and the VHA. Clinicians identified challenges and opportunities for care coordination: (1) financial and logistical barriers to involve family and decision-makers; (2) clinician understanding of cultural values and influence on medical decision-making; (3) care fragmentation resulting from transitions between community care and VHA; and (4) collaboration with key individuals in Pacific social hierarchies.

Conclusions

Cancer navigation and care coordination gaps create challenges for clinicians and NHPI/USAPI Veterans managing cancer in the Pacific Islands. Better understanding of these systems of care and associated gaps can inform the development of an intervention to improve cancer care delivery to this population. NHPI/ USAPI Veterans may experience care fragmentation due to care transitions between community care and the VHA. At the same time, these sources also create multiple layers of support for Veterans. Interventions to address these challenges can leverage the strengths of Pacific communities, while striving to better integrate care between community healthcare providers and VHA.

Background

The Palliative Care in Hawaii/Pacific Island Communities for Veterans (PaCiHPIC Veterans) study is a VA-funded research study that explores social determinants of health, cultural values, and cancer disparities impacting Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander/US-affiliated Pacific Island resident (NHPI/USAPI) Veterans.Cancer prevalence and mortality are increasing among NHPI/ USAPI Veterans which can be partly attributed to nuclear fallout from U.S. military activities in the region. This population faces geographic, financial, and logistical barriers to cancer care. There is an imminent need to understand and address access to cancer care and palliative care to reduce disparities within this population.

Methods

We interviewed 15 clinicians including physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, and clinical psychologists specializing in primary care, palliative care, and oncology, self-identifying as White, Asian American, NHPI, and Multiracial. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and de-identified. Using inductive and deductive strategies, we iteratively collapsed content into codes formulating a codebook. Thematic analyses were performed using dual-coder review in Atlas.ti v23. Themes were mapped to the socioecological model.

Results

Clinicians described how NHPI/USAPI Veterans receive healthcare and instrumental support at individual, community, and systems levels, including from family caregivers, “high-talking chiefs,” traditional healers (“suruhanu”), community health clinics, and the VHA. Clinicians identified challenges and opportunities for care coordination: (1) financial and logistical barriers to involve family and decision-makers; (2) clinician understanding of cultural values and influence on medical decision-making; (3) care fragmentation resulting from transitions between community care and VHA; and (4) collaboration with key individuals in Pacific social hierarchies.

Conclusions

Cancer navigation and care coordination gaps create challenges for clinicians and NHPI/USAPI Veterans managing cancer in the Pacific Islands. Better understanding of these systems of care and associated gaps can inform the development of an intervention to improve cancer care delivery to this population. NHPI/ USAPI Veterans may experience care fragmentation due to care transitions between community care and the VHA. At the same time, these sources also create multiple layers of support for Veterans. Interventions to address these challenges can leverage the strengths of Pacific communities, while striving to better integrate care between community healthcare providers and VHA.

Background

The Palliative Care in Hawaii/Pacific Island Communities for Veterans (PaCiHPIC Veterans) study is a VA-funded research study that explores social determinants of health, cultural values, and cancer disparities impacting Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander/US-affiliated Pacific Island resident (NHPI/USAPI) Veterans.Cancer prevalence and mortality are increasing among NHPI/ USAPI Veterans which can be partly attributed to nuclear fallout from U.S. military activities in the region. This population faces geographic, financial, and logistical barriers to cancer care. There is an imminent need to understand and address access to cancer care and palliative care to reduce disparities within this population.

Methods

We interviewed 15 clinicians including physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, and clinical psychologists specializing in primary care, palliative care, and oncology, self-identifying as White, Asian American, NHPI, and Multiracial. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and de-identified. Using inductive and deductive strategies, we iteratively collapsed content into codes formulating a codebook. Thematic analyses were performed using dual-coder review in Atlas.ti v23. Themes were mapped to the socioecological model.

Results

Clinicians described how NHPI/USAPI Veterans receive healthcare and instrumental support at individual, community, and systems levels, including from family caregivers, “high-talking chiefs,” traditional healers (“suruhanu”), community health clinics, and the VHA. Clinicians identified challenges and opportunities for care coordination: (1) financial and logistical barriers to involve family and decision-makers; (2) clinician understanding of cultural values and influence on medical decision-making; (3) care fragmentation resulting from transitions between community care and VHA; and (4) collaboration with key individuals in Pacific social hierarchies.

Conclusions

Cancer navigation and care coordination gaps create challenges for clinicians and NHPI/USAPI Veterans managing cancer in the Pacific Islands. Better understanding of these systems of care and associated gaps can inform the development of an intervention to improve cancer care delivery to this population. NHPI/ USAPI Veterans may experience care fragmentation due to care transitions between community care and the VHA. At the same time, these sources also create multiple layers of support for Veterans. Interventions to address these challenges can leverage the strengths of Pacific communities, while striving to better integrate care between community healthcare providers and VHA.

Influence of Patient Demographics and Facility Type on Overall Survival in Sezary Syndrome

Background

This study investigates the effects of patient characteristics on overall survival in Sezary Syndrome (SS), addressing a gap in the current literature. SS is a rare and aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). SS is presumed to be related to service exposure, and veterans have a 6-8 times higher incidence of CTCL than the general population. A study investigating the socio-demographic factors at diagnosis on overall survival in SS has yet to be done.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of patients diagnosed with SS (ICD- 9701/3) between 2004 and 2020 in the National Cancer Database (NCDB), highlighting patient demographics on overall survival in SS (N = 809). Exclusion criteria included missing data. Descriptive statistics were collected for all patients with SS. Overall survival was determined via KaplanMeier test. Multivariate analysis via Cox regression was performed to determine factors leading to decreased survival in SS. All statistical tests were evaluated for a significance of P < 0.05.

Results

Of 809 patients with SS, the majority were White (77.3%), male (57.8%), and had an average age at diagnosis of 66.9 years (SD=13.0). Age at diagnosis was associated with decreased overall survival (HR 0.028; 95% CI, 1.016 – 1.042, P< 0.05). Patients with SS treated at nonacademic facilities had a HR of 0.41 (95% CI, 1.171 – 1.932, P< 0.05) compared to academic facilities. Those with private insurance had improved survival with a HR of -0.83 [95% CI, (-0.241) - (-0.781), P< 0.05] compared to those who were non-insured. The average survival time for patients with SS was found to be 73.1 months. The average survival time for patients treated at academic facilities was 8.8 months longer than those treated at nonacademic facilities (75.0 vs 66.2 months, P< 0.05). Patients with private insurance had higher overall survival compared to government-insured and non-insured patients (100.4 versus 56.9 and 54.2 months, respectively). Age, facility type, and primary payor are significant factors that affect survival in SS. Further studies should address the influence of these factors on treatments received by SS patients to decrease disparity related to care.

Background

This study investigates the effects of patient characteristics on overall survival in Sezary Syndrome (SS), addressing a gap in the current literature. SS is a rare and aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). SS is presumed to be related to service exposure, and veterans have a 6-8 times higher incidence of CTCL than the general population. A study investigating the socio-demographic factors at diagnosis on overall survival in SS has yet to be done.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of patients diagnosed with SS (ICD- 9701/3) between 2004 and 2020 in the National Cancer Database (NCDB), highlighting patient demographics on overall survival in SS (N = 809). Exclusion criteria included missing data. Descriptive statistics were collected for all patients with SS. Overall survival was determined via KaplanMeier test. Multivariate analysis via Cox regression was performed to determine factors leading to decreased survival in SS. All statistical tests were evaluated for a significance of P < 0.05.

Results

Of 809 patients with SS, the majority were White (77.3%), male (57.8%), and had an average age at diagnosis of 66.9 years (SD=13.0). Age at diagnosis was associated with decreased overall survival (HR 0.028; 95% CI, 1.016 – 1.042, P< 0.05). Patients with SS treated at nonacademic facilities had a HR of 0.41 (95% CI, 1.171 – 1.932, P< 0.05) compared to academic facilities. Those with private insurance had improved survival with a HR of -0.83 [95% CI, (-0.241) - (-0.781), P< 0.05] compared to those who were non-insured. The average survival time for patients with SS was found to be 73.1 months. The average survival time for patients treated at academic facilities was 8.8 months longer than those treated at nonacademic facilities (75.0 vs 66.2 months, P< 0.05). Patients with private insurance had higher overall survival compared to government-insured and non-insured patients (100.4 versus 56.9 and 54.2 months, respectively). Age, facility type, and primary payor are significant factors that affect survival in SS. Further studies should address the influence of these factors on treatments received by SS patients to decrease disparity related to care.

Background

This study investigates the effects of patient characteristics on overall survival in Sezary Syndrome (SS), addressing a gap in the current literature. SS is a rare and aggressive form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). SS is presumed to be related to service exposure, and veterans have a 6-8 times higher incidence of CTCL than the general population. A study investigating the socio-demographic factors at diagnosis on overall survival in SS has yet to be done.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of patients diagnosed with SS (ICD- 9701/3) between 2004 and 2020 in the National Cancer Database (NCDB), highlighting patient demographics on overall survival in SS (N = 809). Exclusion criteria included missing data. Descriptive statistics were collected for all patients with SS. Overall survival was determined via KaplanMeier test. Multivariate analysis via Cox regression was performed to determine factors leading to decreased survival in SS. All statistical tests were evaluated for a significance of P < 0.05.

Results

Of 809 patients with SS, the majority were White (77.3%), male (57.8%), and had an average age at diagnosis of 66.9 years (SD=13.0). Age at diagnosis was associated with decreased overall survival (HR 0.028; 95% CI, 1.016 – 1.042, P< 0.05). Patients with SS treated at nonacademic facilities had a HR of 0.41 (95% CI, 1.171 – 1.932, P< 0.05) compared to academic facilities. Those with private insurance had improved survival with a HR of -0.83 [95% CI, (-0.241) - (-0.781), P< 0.05] compared to those who were non-insured. The average survival time for patients with SS was found to be 73.1 months. The average survival time for patients treated at academic facilities was 8.8 months longer than those treated at nonacademic facilities (75.0 vs 66.2 months, P< 0.05). Patients with private insurance had higher overall survival compared to government-insured and non-insured patients (100.4 versus 56.9 and 54.2 months, respectively). Age, facility type, and primary payor are significant factors that affect survival in SS. Further studies should address the influence of these factors on treatments received by SS patients to decrease disparity related to care.

RVD With Weekly Bortezomib Has a Favorable Toxicity and Effectiveness Profile in a Large Cohort of US Veterans With Multiple Myeloma

Background

Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) is standard triplet induction for fit newly-diagnosed myeloma (NDMM) patients, with response rate (RR)>90%. A 21-day cycle with bortezomib given days 1, 4, 8, and 11 (2x/w) is standard. However, up to 80% of patients develop neuropathy. Weekly bortezomib dosing (1x/w), subcutaneous route, and 28- to 35-day cycle length may optimize tolerance. We present an effectiveness and toxicity analysis of Veterans who received RVD with 1x/w and 2x/w bortezomib for NDMM.

Methods

The VA Corporate Data Warehouse identified 1499 Veterans with NDMM given RVD ≤42 days of treatment start. 840 Veterans were grouped for initial analysis based on criteria: 1) lenalidomide and ≥ 3 bortezomib doses during cycle 1; 2) ≥6 mean days between bortezomib treatments=1x/w); and 3) number of lenalidomide days informed cycle length (21d, 28d, or 35d; default 7-day rest). Investigators reviewed algorithm results to finalize group assignments. Endpoints included depth of response, time to next treatment (TTNT), overall survival (OS), and neuropathy. Neuropathy was defined as use of neuropathy medications and neuropathy ICD-10 codes.

Results

Our algorithm correctly assigned 82% of 840 cycle 1 RVD schedules. The largest groups were 21d 1x/w (n=291), 21d 2x/w (n=193), 28d 1x/w (n=188), and 28d 2x/w (n=82). Median age was 68.3; 53% were non-Hispanic White. Demographics and ISS stage of groups were similar. 30% underwent autologous transplant. Tolerability. Median number of bortezomib doses ranged from 22.5-25.5 (p=0.57). Neuropathy favored 1x/w, 17.7 vs 30.2% (p=0.0001) and was highest (34.7%) in 21d 2x/w. Effectiveness. Response was assessable for 28% of patients. RR (72%, p=0.68) and median TTNT (19.3 months, p=0.20) were similar, including 1x/w vs 2x/w comparison (p=0.79). 21d regimens optimized TTNT (21.4 vs 13.9 months, p=0.045) and trended to better OS (73 vs 65 months, p=0.06).

Conclusions

1x/w RVD preserved effectiveness compared to “standard” RVD in a large Veteran cohort. 1x/w reduced neuropathy incidence. 28d regimens demonstrated inferior longer-term outcomes. Certain endpoints, such as RR and neuropathy, appear underestimated due to data source limitations. 21d 1x/w RVD optimizes effectiveness, tolerability, and administration and should be considered for broader utilization in Veterans with NDMM.

Background

Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) is standard triplet induction for fit newly-diagnosed myeloma (NDMM) patients, with response rate (RR)>90%. A 21-day cycle with bortezomib given days 1, 4, 8, and 11 (2x/w) is standard. However, up to 80% of patients develop neuropathy. Weekly bortezomib dosing (1x/w), subcutaneous route, and 28- to 35-day cycle length may optimize tolerance. We present an effectiveness and toxicity analysis of Veterans who received RVD with 1x/w and 2x/w bortezomib for NDMM.

Methods

The VA Corporate Data Warehouse identified 1499 Veterans with NDMM given RVD ≤42 days of treatment start. 840 Veterans were grouped for initial analysis based on criteria: 1) lenalidomide and ≥ 3 bortezomib doses during cycle 1; 2) ≥6 mean days between bortezomib treatments=1x/w); and 3) number of lenalidomide days informed cycle length (21d, 28d, or 35d; default 7-day rest). Investigators reviewed algorithm results to finalize group assignments. Endpoints included depth of response, time to next treatment (TTNT), overall survival (OS), and neuropathy. Neuropathy was defined as use of neuropathy medications and neuropathy ICD-10 codes.

Results

Our algorithm correctly assigned 82% of 840 cycle 1 RVD schedules. The largest groups were 21d 1x/w (n=291), 21d 2x/w (n=193), 28d 1x/w (n=188), and 28d 2x/w (n=82). Median age was 68.3; 53% were non-Hispanic White. Demographics and ISS stage of groups were similar. 30% underwent autologous transplant. Tolerability. Median number of bortezomib doses ranged from 22.5-25.5 (p=0.57). Neuropathy favored 1x/w, 17.7 vs 30.2% (p=0.0001) and was highest (34.7%) in 21d 2x/w. Effectiveness. Response was assessable for 28% of patients. RR (72%, p=0.68) and median TTNT (19.3 months, p=0.20) were similar, including 1x/w vs 2x/w comparison (p=0.79). 21d regimens optimized TTNT (21.4 vs 13.9 months, p=0.045) and trended to better OS (73 vs 65 months, p=0.06).

Conclusions

1x/w RVD preserved effectiveness compared to “standard” RVD in a large Veteran cohort. 1x/w reduced neuropathy incidence. 28d regimens demonstrated inferior longer-term outcomes. Certain endpoints, such as RR and neuropathy, appear underestimated due to data source limitations. 21d 1x/w RVD optimizes effectiveness, tolerability, and administration and should be considered for broader utilization in Veterans with NDMM.

Background

Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD) is standard triplet induction for fit newly-diagnosed myeloma (NDMM) patients, with response rate (RR)>90%. A 21-day cycle with bortezomib given days 1, 4, 8, and 11 (2x/w) is standard. However, up to 80% of patients develop neuropathy. Weekly bortezomib dosing (1x/w), subcutaneous route, and 28- to 35-day cycle length may optimize tolerance. We present an effectiveness and toxicity analysis of Veterans who received RVD with 1x/w and 2x/w bortezomib for NDMM.

Methods

The VA Corporate Data Warehouse identified 1499 Veterans with NDMM given RVD ≤42 days of treatment start. 840 Veterans were grouped for initial analysis based on criteria: 1) lenalidomide and ≥ 3 bortezomib doses during cycle 1; 2) ≥6 mean days between bortezomib treatments=1x/w); and 3) number of lenalidomide days informed cycle length (21d, 28d, or 35d; default 7-day rest). Investigators reviewed algorithm results to finalize group assignments. Endpoints included depth of response, time to next treatment (TTNT), overall survival (OS), and neuropathy. Neuropathy was defined as use of neuropathy medications and neuropathy ICD-10 codes.

Results

Our algorithm correctly assigned 82% of 840 cycle 1 RVD schedules. The largest groups were 21d 1x/w (n=291), 21d 2x/w (n=193), 28d 1x/w (n=188), and 28d 2x/w (n=82). Median age was 68.3; 53% were non-Hispanic White. Demographics and ISS stage of groups were similar. 30% underwent autologous transplant. Tolerability. Median number of bortezomib doses ranged from 22.5-25.5 (p=0.57). Neuropathy favored 1x/w, 17.7 vs 30.2% (p=0.0001) and was highest (34.7%) in 21d 2x/w. Effectiveness. Response was assessable for 28% of patients. RR (72%, p=0.68) and median TTNT (19.3 months, p=0.20) were similar, including 1x/w vs 2x/w comparison (p=0.79). 21d regimens optimized TTNT (21.4 vs 13.9 months, p=0.045) and trended to better OS (73 vs 65 months, p=0.06).

Conclusions

1x/w RVD preserved effectiveness compared to “standard” RVD in a large Veteran cohort. 1x/w reduced neuropathy incidence. 28d regimens demonstrated inferior longer-term outcomes. Certain endpoints, such as RR and neuropathy, appear underestimated due to data source limitations. 21d 1x/w RVD optimizes effectiveness, tolerability, and administration and should be considered for broader utilization in Veterans with NDMM.

Agent Orange and Myelodysplastic Syndrome: A Single VAMC Experience

Background

Agent Orange (AO) exposure may be linked to development of myeloid malignancies, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). This is not yet definitive, though, and, unlike several other malignancies, MDS is not yet a service-connected diagnosis for AO. Although recent studies have not revealed AO associated specific mutations in MDS, other clinical and pathological potential differences have not been well described. In addition, determination of AO exposure is often not reported. Purpose: To assess for differences between AO versus non-AO exposed veterans with MDS.

Methods

All veterans diagnosed with MDS at the Cleveland VAMC from 2012-2023 were identified. Prior AO exposure was determined by Military Exposure tab in the EMR (CPRS) and confirmed with direct patient contact. Data collected included age and IPSS-R score at diagnosis; ring sideroblast percentage; mutations (on NGS); progression to AML and overall survival (OS).

Results

129 veterans were identified, 48 of whom had AO exposure. The mean age was 70.7 years in the AO group and 73.3 in the non-AO group (p=0.098); average IPSS-R score was 3.14 in AO and 2.75 in non-AO group (p= 0.32). In the AO group 4/48 (8.3%) progressed to AML vs 10/81 (12.3%) in the non-AO group; median OS was 39 months in AO vs 33 months in non-AO group (p=0.93). The most common mutations seen were TP53, SF3B1, SRSF2, DNMT, ASXL1, and U2AF1, with no differences between the 2 groups. 50% of those in the AO group had 2 or more genetic mutations vs. 61% for the non-AO group. Average variant allele frequency (VAF) was 40.2% in the AO group vs. 44% in the non-AO group. The average ring sideroblasts seen was 6% for the AO group compared to 5.7% for the non-AO group, p = 0.89.

Conclusions

This small retrospective study did not reveal statistically significant differences between AO vs non-AO exposed veterans with MDS, in terms of age at diagnosis, IPSS-R score, RS %, mutations (type, number or VAF load), progression to AML or OS. There were trends for AO exposed veterans presenting at a younger age and having a lower rate of progression to AML.

Background

Agent Orange (AO) exposure may be linked to development of myeloid malignancies, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). This is not yet definitive, though, and, unlike several other malignancies, MDS is not yet a service-connected diagnosis for AO. Although recent studies have not revealed AO associated specific mutations in MDS, other clinical and pathological potential differences have not been well described. In addition, determination of AO exposure is often not reported. Purpose: To assess for differences between AO versus non-AO exposed veterans with MDS.

Methods

All veterans diagnosed with MDS at the Cleveland VAMC from 2012-2023 were identified. Prior AO exposure was determined by Military Exposure tab in the EMR (CPRS) and confirmed with direct patient contact. Data collected included age and IPSS-R score at diagnosis; ring sideroblast percentage; mutations (on NGS); progression to AML and overall survival (OS).

Results

129 veterans were identified, 48 of whom had AO exposure. The mean age was 70.7 years in the AO group and 73.3 in the non-AO group (p=0.098); average IPSS-R score was 3.14 in AO and 2.75 in non-AO group (p= 0.32). In the AO group 4/48 (8.3%) progressed to AML vs 10/81 (12.3%) in the non-AO group; median OS was 39 months in AO vs 33 months in non-AO group (p=0.93). The most common mutations seen were TP53, SF3B1, SRSF2, DNMT, ASXL1, and U2AF1, with no differences between the 2 groups. 50% of those in the AO group had 2 or more genetic mutations vs. 61% for the non-AO group. Average variant allele frequency (VAF) was 40.2% in the AO group vs. 44% in the non-AO group. The average ring sideroblasts seen was 6% for the AO group compared to 5.7% for the non-AO group, p = 0.89.

Conclusions

This small retrospective study did not reveal statistically significant differences between AO vs non-AO exposed veterans with MDS, in terms of age at diagnosis, IPSS-R score, RS %, mutations (type, number or VAF load), progression to AML or OS. There were trends for AO exposed veterans presenting at a younger age and having a lower rate of progression to AML.

Background

Agent Orange (AO) exposure may be linked to development of myeloid malignancies, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). This is not yet definitive, though, and, unlike several other malignancies, MDS is not yet a service-connected diagnosis for AO. Although recent studies have not revealed AO associated specific mutations in MDS, other clinical and pathological potential differences have not been well described. In addition, determination of AO exposure is often not reported. Purpose: To assess for differences between AO versus non-AO exposed veterans with MDS.

Methods

All veterans diagnosed with MDS at the Cleveland VAMC from 2012-2023 were identified. Prior AO exposure was determined by Military Exposure tab in the EMR (CPRS) and confirmed with direct patient contact. Data collected included age and IPSS-R score at diagnosis; ring sideroblast percentage; mutations (on NGS); progression to AML and overall survival (OS).

Results

129 veterans were identified, 48 of whom had AO exposure. The mean age was 70.7 years in the AO group and 73.3 in the non-AO group (p=0.098); average IPSS-R score was 3.14 in AO and 2.75 in non-AO group (p= 0.32). In the AO group 4/48 (8.3%) progressed to AML vs 10/81 (12.3%) in the non-AO group; median OS was 39 months in AO vs 33 months in non-AO group (p=0.93). The most common mutations seen were TP53, SF3B1, SRSF2, DNMT, ASXL1, and U2AF1, with no differences between the 2 groups. 50% of those in the AO group had 2 or more genetic mutations vs. 61% for the non-AO group. Average variant allele frequency (VAF) was 40.2% in the AO group vs. 44% in the non-AO group. The average ring sideroblasts seen was 6% for the AO group compared to 5.7% for the non-AO group, p = 0.89.

Conclusions

This small retrospective study did not reveal statistically significant differences between AO vs non-AO exposed veterans with MDS, in terms of age at diagnosis, IPSS-R score, RS %, mutations (type, number or VAF load), progression to AML or OS. There were trends for AO exposed veterans presenting at a younger age and having a lower rate of progression to AML.

Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Older (Age ≥ 80) Veterans With Newly Diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)

Background

Over one-third of newly diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cases are in people age ≥75. Although a potentially curable malignancy, older adults have a comparatively lower survival rate. This may be due to multiple factors including suboptimal management. In one study, up to 23% of patients age ≥80 did not receive any therapy for DLBCL. This age-related survival disparity is potentially magnified in patients who reside in rural areas. As there is no standard of care for this population, we speculate that there is wide variation in treatment practices which may influence outcomes. The purpose of this study is to describe treatment patterns and outcomes in in veterans age ≥80 with DLBCL by area of residence.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of veterans age ≥80 newly diagnosed with Stage II-IV DLBCL between 2006-2023 using the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cancer Registry System (VACRS). Patient, disease, and treatment variables were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and via chart review. Variables were compared amongst Veterans residing at urban vs. rural addresses.

Results

We evaluated a total of 181 Veterans. Most veterans resided in an urban area (60.2%). At least 18.8% of veterans failed to start lymphoma-directed therapy, but only 6.6% of veterans were not explicitly offered treatment per documentation. In total, 68.5% of veterans were offered a curative treatment regimen by their provider; curative treatment was more likely to be offered to urban patients (68.8% vs 61.5%, p=0.86). Pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments prior to treatment were severely underutilized (2.8% and 0.6%). More urban veterans started treatment (75.2% vs 65.4%, p=0.38) and 40.9% started an anthracyclinecontaining regimen. Only 27.6% of veterans completed 6 total cycles of treatment. Only 37.6% of veterans achieved a complete response at end of treatment, although response was not reported in 46.4% of patients.

Conclusions

Most elderly veterans with DLBCL are being offered and started on a curative treatment regimen; however, most do not complete a full course of treatment. Although not statistically significant, more urban veterans were offered a curative regimen and received treatment. Wider adoption of pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments could improve response outcomes.

Background

Over one-third of newly diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cases are in people age ≥75. Although a potentially curable malignancy, older adults have a comparatively lower survival rate. This may be due to multiple factors including suboptimal management. In one study, up to 23% of patients age ≥80 did not receive any therapy for DLBCL. This age-related survival disparity is potentially magnified in patients who reside in rural areas. As there is no standard of care for this population, we speculate that there is wide variation in treatment practices which may influence outcomes. The purpose of this study is to describe treatment patterns and outcomes in in veterans age ≥80 with DLBCL by area of residence.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of veterans age ≥80 newly diagnosed with Stage II-IV DLBCL between 2006-2023 using the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cancer Registry System (VACRS). Patient, disease, and treatment variables were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and via chart review. Variables were compared amongst Veterans residing at urban vs. rural addresses.

Results

We evaluated a total of 181 Veterans. Most veterans resided in an urban area (60.2%). At least 18.8% of veterans failed to start lymphoma-directed therapy, but only 6.6% of veterans were not explicitly offered treatment per documentation. In total, 68.5% of veterans were offered a curative treatment regimen by their provider; curative treatment was more likely to be offered to urban patients (68.8% vs 61.5%, p=0.86). Pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments prior to treatment were severely underutilized (2.8% and 0.6%). More urban veterans started treatment (75.2% vs 65.4%, p=0.38) and 40.9% started an anthracyclinecontaining regimen. Only 27.6% of veterans completed 6 total cycles of treatment. Only 37.6% of veterans achieved a complete response at end of treatment, although response was not reported in 46.4% of patients.

Conclusions

Most elderly veterans with DLBCL are being offered and started on a curative treatment regimen; however, most do not complete a full course of treatment. Although not statistically significant, more urban veterans were offered a curative regimen and received treatment. Wider adoption of pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments could improve response outcomes.

Background

Over one-third of newly diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) cases are in people age ≥75. Although a potentially curable malignancy, older adults have a comparatively lower survival rate. This may be due to multiple factors including suboptimal management. In one study, up to 23% of patients age ≥80 did not receive any therapy for DLBCL. This age-related survival disparity is potentially magnified in patients who reside in rural areas. As there is no standard of care for this population, we speculate that there is wide variation in treatment practices which may influence outcomes. The purpose of this study is to describe treatment patterns and outcomes in in veterans age ≥80 with DLBCL by area of residence.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of veterans age ≥80 newly diagnosed with Stage II-IV DLBCL between 2006-2023 using the Veterans Affairs (VA) Cancer Registry System (VACRS). Patient, disease, and treatment variables were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and via chart review. Variables were compared amongst Veterans residing at urban vs. rural addresses.

Results

We evaluated a total of 181 Veterans. Most veterans resided in an urban area (60.2%). At least 18.8% of veterans failed to start lymphoma-directed therapy, but only 6.6% of veterans were not explicitly offered treatment per documentation. In total, 68.5% of veterans were offered a curative treatment regimen by their provider; curative treatment was more likely to be offered to urban patients (68.8% vs 61.5%, p=0.86). Pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments prior to treatment were severely underutilized (2.8% and 0.6%). More urban veterans started treatment (75.2% vs 65.4%, p=0.38) and 40.9% started an anthracyclinecontaining regimen. Only 27.6% of veterans completed 6 total cycles of treatment. Only 37.6% of veterans achieved a complete response at end of treatment, although response was not reported in 46.4% of patients.

Conclusions

Most elderly veterans with DLBCL are being offered and started on a curative treatment regimen; however, most do not complete a full course of treatment. Although not statistically significant, more urban veterans were offered a curative regimen and received treatment. Wider adoption of pre-phase steroids and geriatric assessments could improve response outcomes.

Investigating Differences in Melanoma Mortality Based on Demographic Information from 1999-2022 Using CDC Wonder

Background

Melanoma is a malignant type of skin cancer and is the fifth most common type of cancer in the United States. The purpose of this study is to determine how demographic information such as race and gender may influence mortality rates in melanoma patients. To date, no previous studies have analyzed epidemiological trends in melanoma mortality using the CDC Wonder database. However, previous literature has suggested that non-Hispanic Whites have the highest mortality rate.

Methods

CDC Wonder is a database that contains mortality and demographic information for various pathologies. Melanoma cases were specified using the ICD-10 code C43. Patients over the age of 35 were considered for this study. Mortality rates were generated based on gender, race, and a combination of both variables. Data analysis involved finding the rates and 95% confidence intervals for the crude and age-adjusted mortality rate (AAMR) per 100,000. Joinpoint regression analysis was also used.

Results

Several differences in the age-adjusted mortality rate were observed. In every year from 1999 to 2022, the non-Hispanic White group (NH White) had the highest mortality rate, whereas all other races had similar rates. Meanwhile, when stratifying by both race and gender, it appears that NH White males have the highest rate in mortality. In 2022, the mortality rate for NH White males was 8.8 per 100,000, whereas the second highest rate belonged to the NH White female group (4 per 100,000). All other racial and gender combinations had similar mortality rates. The trends in mortality rates did not fluctuate much from the years 1999-2022. No significant deviation in mortality trends were seen after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

This data corroborates with the results from previous studies. It also indicates that certain demographics that may be at greater risk for mortality, and that the mortality rates have remained relatively stable. The mortality rate for melanoma may vary by race and gender. More specifically, NH White males may be susceptible to higher mortality rates compared to other demographic groups. Future research on cancer staging and treatment modality received could help explain these differences.

Background

Melanoma is a malignant type of skin cancer and is the fifth most common type of cancer in the United States. The purpose of this study is to determine how demographic information such as race and gender may influence mortality rates in melanoma patients. To date, no previous studies have analyzed epidemiological trends in melanoma mortality using the CDC Wonder database. However, previous literature has suggested that non-Hispanic Whites have the highest mortality rate.

Methods

CDC Wonder is a database that contains mortality and demographic information for various pathologies. Melanoma cases were specified using the ICD-10 code C43. Patients over the age of 35 were considered for this study. Mortality rates were generated based on gender, race, and a combination of both variables. Data analysis involved finding the rates and 95% confidence intervals for the crude and age-adjusted mortality rate (AAMR) per 100,000. Joinpoint regression analysis was also used.

Results

Several differences in the age-adjusted mortality rate were observed. In every year from 1999 to 2022, the non-Hispanic White group (NH White) had the highest mortality rate, whereas all other races had similar rates. Meanwhile, when stratifying by both race and gender, it appears that NH White males have the highest rate in mortality. In 2022, the mortality rate for NH White males was 8.8 per 100,000, whereas the second highest rate belonged to the NH White female group (4 per 100,000). All other racial and gender combinations had similar mortality rates. The trends in mortality rates did not fluctuate much from the years 1999-2022. No significant deviation in mortality trends were seen after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

This data corroborates with the results from previous studies. It also indicates that certain demographics that may be at greater risk for mortality, and that the mortality rates have remained relatively stable. The mortality rate for melanoma may vary by race and gender. More specifically, NH White males may be susceptible to higher mortality rates compared to other demographic groups. Future research on cancer staging and treatment modality received could help explain these differences.

Background

Melanoma is a malignant type of skin cancer and is the fifth most common type of cancer in the United States. The purpose of this study is to determine how demographic information such as race and gender may influence mortality rates in melanoma patients. To date, no previous studies have analyzed epidemiological trends in melanoma mortality using the CDC Wonder database. However, previous literature has suggested that non-Hispanic Whites have the highest mortality rate.

Methods

CDC Wonder is a database that contains mortality and demographic information for various pathologies. Melanoma cases were specified using the ICD-10 code C43. Patients over the age of 35 were considered for this study. Mortality rates were generated based on gender, race, and a combination of both variables. Data analysis involved finding the rates and 95% confidence intervals for the crude and age-adjusted mortality rate (AAMR) per 100,000. Joinpoint regression analysis was also used.

Results

Several differences in the age-adjusted mortality rate were observed. In every year from 1999 to 2022, the non-Hispanic White group (NH White) had the highest mortality rate, whereas all other races had similar rates. Meanwhile, when stratifying by both race and gender, it appears that NH White males have the highest rate in mortality. In 2022, the mortality rate for NH White males was 8.8 per 100,000, whereas the second highest rate belonged to the NH White female group (4 per 100,000). All other racial and gender combinations had similar mortality rates. The trends in mortality rates did not fluctuate much from the years 1999-2022. No significant deviation in mortality trends were seen after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

This data corroborates with the results from previous studies. It also indicates that certain demographics that may be at greater risk for mortality, and that the mortality rates have remained relatively stable. The mortality rate for melanoma may vary by race and gender. More specifically, NH White males may be susceptible to higher mortality rates compared to other demographic groups. Future research on cancer staging and treatment modality received could help explain these differences.

Recent Incidence and Survival Trends in Pancreatic Cancer at Young Age (<50 Years)

Background

Pancreatic cancer stands as a prominent contributor to cancer-related mortality in the United States. In this abstract, we reviewed the SEER database to uncover the latest trends in pancreatic cancer among individuals diagnosed under the age of 50.

Methods

Information was obtained from the SEER database November 2023 which covers 22 national cancer registries. Only patients with age < 50 years were included. Age adjusted incidence and 5-year relative survival were compared between different ethnic groups.

Results

We identified 124691 patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed between 2017-2021, among them 6477 were with age less than 50 years at the time of diagnosis. 3074 were male and 3403 were male. Age adjusted incidence rate was 1.2/100,000 in females and 1.4/100,000 in males. Overall, Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) of 2.6% (95% CI: 1.9 – 4.3) was noticed between 2017-2021 when compared to previously reported rates. AAPC among different ethnic groups were Hispanics, any race: 5.3% (CI: 4-7.5), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 1.1 (CI: -2.7-5.1), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 1.9 (CI: 1.1-2.9), Non-Hispanic Black: 1.0 (CI: 0.3-1.7), and Non-Hispanic White: 1.6 (CI: 1.1-2.1). Stage 4 was the most common stage. Overall, the 5-year relative survival from 2014- 2020 was 37.4% (CI: 36.1-38.7). 5-year relative survival among ethnic groups from 2014-2020 were: Hispanics, any race: 40.3% (CI: 37.6-43.0), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 21.4 (CI: 8.5-38.2), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 40.2 (CI: 35.7-44.7), Non-Hispanic Black: 33.1 (CI: 29.9-36.3), and Non-Hispanic White: 36.6 (CI: 34.8-38.4).

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals a rise in the ageadjusted incidence of pancreatic cancer among younger demographics. Particularly noteworthy is the sharp increase observed over the past five years among Hispanics when compared to other ethnic populations. This rise is observed in both males and females. Further studies need to be done to study the risk factors associated with this increase in trend of pancreatic cancer at young age specifically in Hispanic population.

Background

Pancreatic cancer stands as a prominent contributor to cancer-related mortality in the United States. In this abstract, we reviewed the SEER database to uncover the latest trends in pancreatic cancer among individuals diagnosed under the age of 50.

Methods

Information was obtained from the SEER database November 2023 which covers 22 national cancer registries. Only patients with age < 50 years were included. Age adjusted incidence and 5-year relative survival were compared between different ethnic groups.

Results

We identified 124691 patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed between 2017-2021, among them 6477 were with age less than 50 years at the time of diagnosis. 3074 were male and 3403 were male. Age adjusted incidence rate was 1.2/100,000 in females and 1.4/100,000 in males. Overall, Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) of 2.6% (95% CI: 1.9 – 4.3) was noticed between 2017-2021 when compared to previously reported rates. AAPC among different ethnic groups were Hispanics, any race: 5.3% (CI: 4-7.5), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 1.1 (CI: -2.7-5.1), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 1.9 (CI: 1.1-2.9), Non-Hispanic Black: 1.0 (CI: 0.3-1.7), and Non-Hispanic White: 1.6 (CI: 1.1-2.1). Stage 4 was the most common stage. Overall, the 5-year relative survival from 2014- 2020 was 37.4% (CI: 36.1-38.7). 5-year relative survival among ethnic groups from 2014-2020 were: Hispanics, any race: 40.3% (CI: 37.6-43.0), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 21.4 (CI: 8.5-38.2), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 40.2 (CI: 35.7-44.7), Non-Hispanic Black: 33.1 (CI: 29.9-36.3), and Non-Hispanic White: 36.6 (CI: 34.8-38.4).

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals a rise in the ageadjusted incidence of pancreatic cancer among younger demographics. Particularly noteworthy is the sharp increase observed over the past five years among Hispanics when compared to other ethnic populations. This rise is observed in both males and females. Further studies need to be done to study the risk factors associated with this increase in trend of pancreatic cancer at young age specifically in Hispanic population.

Background

Pancreatic cancer stands as a prominent contributor to cancer-related mortality in the United States. In this abstract, we reviewed the SEER database to uncover the latest trends in pancreatic cancer among individuals diagnosed under the age of 50.

Methods

Information was obtained from the SEER database November 2023 which covers 22 national cancer registries. Only patients with age < 50 years were included. Age adjusted incidence and 5-year relative survival were compared between different ethnic groups.

Results

We identified 124691 patients with pancreatic cancer diagnosed between 2017-2021, among them 6477 were with age less than 50 years at the time of diagnosis. 3074 were male and 3403 were male. Age adjusted incidence rate was 1.2/100,000 in females and 1.4/100,000 in males. Overall, Average Annual Percent Change (AAPC) of 2.6% (95% CI: 1.9 – 4.3) was noticed between 2017-2021 when compared to previously reported rates. AAPC among different ethnic groups were Hispanics, any race: 5.3% (CI: 4-7.5), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 1.1 (CI: -2.7-5.1), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 1.9 (CI: 1.1-2.9), Non-Hispanic Black: 1.0 (CI: 0.3-1.7), and Non-Hispanic White: 1.6 (CI: 1.1-2.1). Stage 4 was the most common stage. Overall, the 5-year relative survival from 2014- 2020 was 37.4% (CI: 36.1-38.7). 5-year relative survival among ethnic groups from 2014-2020 were: Hispanics, any race: 40.3% (CI: 37.6-43.0), Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native: 21.4 (CI: 8.5-38.2), Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander: 40.2 (CI: 35.7-44.7), Non-Hispanic Black: 33.1 (CI: 29.9-36.3), and Non-Hispanic White: 36.6 (CI: 34.8-38.4).

Conclusions

Our analysis reveals a rise in the ageadjusted incidence of pancreatic cancer among younger demographics. Particularly noteworthy is the sharp increase observed over the past five years among Hispanics when compared to other ethnic populations. This rise is observed in both males and females. Further studies need to be done to study the risk factors associated with this increase in trend of pancreatic cancer at young age specifically in Hispanic population.