User login

Trial of epicutaneous immunotherapy in eosinophilic esophagitis

For children with milk-induced eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), 9 months of epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) with Viaskin Milk did not significantly improve eosinophil counts or symptoms, compared with placebo, according to the results of an intention-to-treat analysis of a randomized, double-blinded pilot study.

Average maximum eosinophil counts were 50.1 per high-power field in the Viaskin Milk group versus 48.2 in the placebo group, said Jonathan M. Spergel, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates. However, in the per-protocol analysis, the seven patients who received Viaskin Milk had mean eosinophil counts of 25.6 per high-power field, compared with 95.0 for the two children who received placebo (P = .038). Moreover, 47% of patients had fewer than 15 eosinophils per high-power field after an additional 11 months of open-label treatment with Viaskin Milk. Taken together, the findings justify larger, multicenter studies to evaluate EPIT for treating EoE and other non-IgE mediated food diseases, Dr. Spergel and associates wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

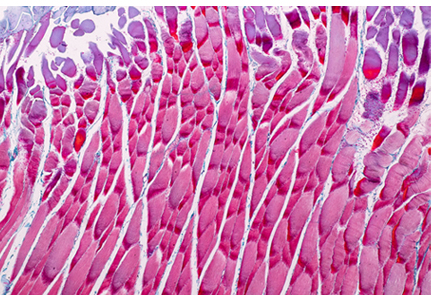

EoE results from an immune response to specific food allergens, including milk. Classic symptoms include difficulty feeding and failure to thrive in infants, abdominal pain in young children, and dysphagia in older children and adults. Definitive diagnosis requires an esophageal biopsy with an eosinophil count of 15 or more cells per high-power field. “There are no approved therapies [for eosinophilic esophagitis] beyond avoidance of the allergen(s) or treatment of inflammation,” the investigators wrote.

In prior studies, exposure to EPIT was found to mitigate eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease in mice and pigs. In humans, milk is the most common dietary cause of eosinophilic esophagitis. Accordingly, Viaskin Milk is an EPIT containing an allergen extract of milk that is administered epicutaneously using a specialized delivery system. To evaluate its use for the treatment of pediatric milk-induced EoE (at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame despite at least 2 months of high-dose proton pump–inhibitor therapy at 1-2 mg/kg twice daily), the researchers randomly assigned 20 children on a 3:1 basis to receive either Viaskin Milk or placebo for 9 months. Patients and investigators were double-blinded for this phase of the study, during most of which patients abstained from milk. Toward the end of the 9 months, patients resumed consuming milk and continued doing so if their upper endoscopy biopsy showed resolution of EoE (eosinophil count less than 15 per high-power field).

In the intention-to-treat analysis, Viaskin Milk did not meet the primary endpoint of the difference in least squares mean compared with placebo (8.6; 95% confidence interval, –35.36 to 52.56). Symptom scores also were similar between groups. In contrast, at the end of the 11-month, open-label period, 9 of 19 evaluable patients had eosinophil biopsy counts of fewer than 15 per high-power field, for a response rate of 47%. “The number of adverse events did not differ significantly between the Viaskin Milk and placebo groups,” the researchers added.

Protocol violations might explain why EPIT failed to meet the primary endpoint in the intention-to-treat analysis, they wrote. “For example, the patients on the active therapy wanted to ingest more milk, while the patients in the placebo group wanted less milk,” they reported. “Three patients in the active therapy went on binge milk diets drinking 4 to 8 times the amount of milk compared with baseline.” The use of proton pump inhibitors also was inconsistent between groups, they added. “The major limitation in the [per-protocol] population was the small sample size of this pilot study, raising the possibility of false-positive results.”

The study was funded by DBV Technologies and by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Eosinophilic Esophagitis Family Fund. Dr. Spergel disclosed consulting agreements, grants funding, and stock equity with DBV Technologies. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to DBV. The remaining five coinvestigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Spergel JM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.014.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is primarily triggered by food antigens. Though many patients can be treated with dietary elimination or pharmacologic therapies, when foods are added back, elimination diets are not followed, or medications stopped, the disease will flare. Further, unlike some other atopic conditions, patients with EoE do not “grow out of it.” A true cure for EoE has been elusive. In this study by Spergel and colleagues, they build on intriguing data from animal models showing induction of immune tolerance to food antigens with epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT).

The investigators conducted a proof-of-concept, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of epicutaneous desensitization with a milk patch in children with EoE who had milk as a confirmed dietary trigger. The primary intention-to-treat results showed that there was no difference between placebo and active patches for decreasing esophageal eosinophil counts. However, in the small set of patients who were able to adhere fully to the protocol, the per-protocol analysis suggested that there was a lower eosinophil count with active treatment. Additionally, in an 11-month, open-label extension, there were patients who maintained histologic response (less than 15 eosinophils/hpf) after reintroducing milk.

These data suggest that EPIT potentially can desensitize milk-triggered EoE patients and that this treatment method should be pursued in future studies, with protocol alterations based on lessons learned regarding adherence in this study. Should this line of investigation be successful, then EoE patients who have milk as their EoE trigger, and who undergo successful desensitization with mild reintroduction while maintaining disease remission, may be able to be deemed cured.

Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and epidemiology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has received research funding from and consulted for Adare, Allakos, GSK, Celgene/Receptos, and Shire/Takeda among other pharmaceutical companies.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is primarily triggered by food antigens. Though many patients can be treated with dietary elimination or pharmacologic therapies, when foods are added back, elimination diets are not followed, or medications stopped, the disease will flare. Further, unlike some other atopic conditions, patients with EoE do not “grow out of it.” A true cure for EoE has been elusive. In this study by Spergel and colleagues, they build on intriguing data from animal models showing induction of immune tolerance to food antigens with epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT).

The investigators conducted a proof-of-concept, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of epicutaneous desensitization with a milk patch in children with EoE who had milk as a confirmed dietary trigger. The primary intention-to-treat results showed that there was no difference between placebo and active patches for decreasing esophageal eosinophil counts. However, in the small set of patients who were able to adhere fully to the protocol, the per-protocol analysis suggested that there was a lower eosinophil count with active treatment. Additionally, in an 11-month, open-label extension, there were patients who maintained histologic response (less than 15 eosinophils/hpf) after reintroducing milk.

These data suggest that EPIT potentially can desensitize milk-triggered EoE patients and that this treatment method should be pursued in future studies, with protocol alterations based on lessons learned regarding adherence in this study. Should this line of investigation be successful, then EoE patients who have milk as their EoE trigger, and who undergo successful desensitization with mild reintroduction while maintaining disease remission, may be able to be deemed cured.

Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and epidemiology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has received research funding from and consulted for Adare, Allakos, GSK, Celgene/Receptos, and Shire/Takeda among other pharmaceutical companies.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated disease that is primarily triggered by food antigens. Though many patients can be treated with dietary elimination or pharmacologic therapies, when foods are added back, elimination diets are not followed, or medications stopped, the disease will flare. Further, unlike some other atopic conditions, patients with EoE do not “grow out of it.” A true cure for EoE has been elusive. In this study by Spergel and colleagues, they build on intriguing data from animal models showing induction of immune tolerance to food antigens with epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT).

The investigators conducted a proof-of-concept, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of epicutaneous desensitization with a milk patch in children with EoE who had milk as a confirmed dietary trigger. The primary intention-to-treat results showed that there was no difference between placebo and active patches for decreasing esophageal eosinophil counts. However, in the small set of patients who were able to adhere fully to the protocol, the per-protocol analysis suggested that there was a lower eosinophil count with active treatment. Additionally, in an 11-month, open-label extension, there were patients who maintained histologic response (less than 15 eosinophils/hpf) after reintroducing milk.

These data suggest that EPIT potentially can desensitize milk-triggered EoE patients and that this treatment method should be pursued in future studies, with protocol alterations based on lessons learned regarding adherence in this study. Should this line of investigation be successful, then EoE patients who have milk as their EoE trigger, and who undergo successful desensitization with mild reintroduction while maintaining disease remission, may be able to be deemed cured.

Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and epidemiology, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He has received research funding from and consulted for Adare, Allakos, GSK, Celgene/Receptos, and Shire/Takeda among other pharmaceutical companies.

For children with milk-induced eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), 9 months of epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) with Viaskin Milk did not significantly improve eosinophil counts or symptoms, compared with placebo, according to the results of an intention-to-treat analysis of a randomized, double-blinded pilot study.

Average maximum eosinophil counts were 50.1 per high-power field in the Viaskin Milk group versus 48.2 in the placebo group, said Jonathan M. Spergel, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates. However, in the per-protocol analysis, the seven patients who received Viaskin Milk had mean eosinophil counts of 25.6 per high-power field, compared with 95.0 for the two children who received placebo (P = .038). Moreover, 47% of patients had fewer than 15 eosinophils per high-power field after an additional 11 months of open-label treatment with Viaskin Milk. Taken together, the findings justify larger, multicenter studies to evaluate EPIT for treating EoE and other non-IgE mediated food diseases, Dr. Spergel and associates wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

EoE results from an immune response to specific food allergens, including milk. Classic symptoms include difficulty feeding and failure to thrive in infants, abdominal pain in young children, and dysphagia in older children and adults. Definitive diagnosis requires an esophageal biopsy with an eosinophil count of 15 or more cells per high-power field. “There are no approved therapies [for eosinophilic esophagitis] beyond avoidance of the allergen(s) or treatment of inflammation,” the investigators wrote.

In prior studies, exposure to EPIT was found to mitigate eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease in mice and pigs. In humans, milk is the most common dietary cause of eosinophilic esophagitis. Accordingly, Viaskin Milk is an EPIT containing an allergen extract of milk that is administered epicutaneously using a specialized delivery system. To evaluate its use for the treatment of pediatric milk-induced EoE (at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame despite at least 2 months of high-dose proton pump–inhibitor therapy at 1-2 mg/kg twice daily), the researchers randomly assigned 20 children on a 3:1 basis to receive either Viaskin Milk or placebo for 9 months. Patients and investigators were double-blinded for this phase of the study, during most of which patients abstained from milk. Toward the end of the 9 months, patients resumed consuming milk and continued doing so if their upper endoscopy biopsy showed resolution of EoE (eosinophil count less than 15 per high-power field).

In the intention-to-treat analysis, Viaskin Milk did not meet the primary endpoint of the difference in least squares mean compared with placebo (8.6; 95% confidence interval, –35.36 to 52.56). Symptom scores also were similar between groups. In contrast, at the end of the 11-month, open-label period, 9 of 19 evaluable patients had eosinophil biopsy counts of fewer than 15 per high-power field, for a response rate of 47%. “The number of adverse events did not differ significantly between the Viaskin Milk and placebo groups,” the researchers added.

Protocol violations might explain why EPIT failed to meet the primary endpoint in the intention-to-treat analysis, they wrote. “For example, the patients on the active therapy wanted to ingest more milk, while the patients in the placebo group wanted less milk,” they reported. “Three patients in the active therapy went on binge milk diets drinking 4 to 8 times the amount of milk compared with baseline.” The use of proton pump inhibitors also was inconsistent between groups, they added. “The major limitation in the [per-protocol] population was the small sample size of this pilot study, raising the possibility of false-positive results.”

The study was funded by DBV Technologies and by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Eosinophilic Esophagitis Family Fund. Dr. Spergel disclosed consulting agreements, grants funding, and stock equity with DBV Technologies. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to DBV. The remaining five coinvestigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Spergel JM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.014.

For children with milk-induced eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), 9 months of epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) with Viaskin Milk did not significantly improve eosinophil counts or symptoms, compared with placebo, according to the results of an intention-to-treat analysis of a randomized, double-blinded pilot study.

Average maximum eosinophil counts were 50.1 per high-power field in the Viaskin Milk group versus 48.2 in the placebo group, said Jonathan M. Spergel, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates. However, in the per-protocol analysis, the seven patients who received Viaskin Milk had mean eosinophil counts of 25.6 per high-power field, compared with 95.0 for the two children who received placebo (P = .038). Moreover, 47% of patients had fewer than 15 eosinophils per high-power field after an additional 11 months of open-label treatment with Viaskin Milk. Taken together, the findings justify larger, multicenter studies to evaluate EPIT for treating EoE and other non-IgE mediated food diseases, Dr. Spergel and associates wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

EoE results from an immune response to specific food allergens, including milk. Classic symptoms include difficulty feeding and failure to thrive in infants, abdominal pain in young children, and dysphagia in older children and adults. Definitive diagnosis requires an esophageal biopsy with an eosinophil count of 15 or more cells per high-power field. “There are no approved therapies [for eosinophilic esophagitis] beyond avoidance of the allergen(s) or treatment of inflammation,” the investigators wrote.

In prior studies, exposure to EPIT was found to mitigate eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease in mice and pigs. In humans, milk is the most common dietary cause of eosinophilic esophagitis. Accordingly, Viaskin Milk is an EPIT containing an allergen extract of milk that is administered epicutaneously using a specialized delivery system. To evaluate its use for the treatment of pediatric milk-induced EoE (at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame despite at least 2 months of high-dose proton pump–inhibitor therapy at 1-2 mg/kg twice daily), the researchers randomly assigned 20 children on a 3:1 basis to receive either Viaskin Milk or placebo for 9 months. Patients and investigators were double-blinded for this phase of the study, during most of which patients abstained from milk. Toward the end of the 9 months, patients resumed consuming milk and continued doing so if their upper endoscopy biopsy showed resolution of EoE (eosinophil count less than 15 per high-power field).

In the intention-to-treat analysis, Viaskin Milk did not meet the primary endpoint of the difference in least squares mean compared with placebo (8.6; 95% confidence interval, –35.36 to 52.56). Symptom scores also were similar between groups. In contrast, at the end of the 11-month, open-label period, 9 of 19 evaluable patients had eosinophil biopsy counts of fewer than 15 per high-power field, for a response rate of 47%. “The number of adverse events did not differ significantly between the Viaskin Milk and placebo groups,” the researchers added.

Protocol violations might explain why EPIT failed to meet the primary endpoint in the intention-to-treat analysis, they wrote. “For example, the patients on the active therapy wanted to ingest more milk, while the patients in the placebo group wanted less milk,” they reported. “Three patients in the active therapy went on binge milk diets drinking 4 to 8 times the amount of milk compared with baseline.” The use of proton pump inhibitors also was inconsistent between groups, they added. “The major limitation in the [per-protocol] population was the small sample size of this pilot study, raising the possibility of false-positive results.”

The study was funded by DBV Technologies and by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Eosinophilic Esophagitis Family Fund. Dr. Spergel disclosed consulting agreements, grants funding, and stock equity with DBV Technologies. Three coinvestigators also disclosed ties to DBV. The remaining five coinvestigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Spergel JM et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.014.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

ADA2 is a potent new biomarker for macrophage activation syndrome

ATLANTA – Adenosine deaminase 2 above the upper limit of normal is 86% sensitive and 94% specific for distinguishing macrophage activation syndrome from active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, making it perhaps the most potent blood marker yet identified to differentiate the two, according to a report presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The upper limit of normal was 27.8 U/L, two standard deviations above the median of 13 U/L (interquartile range, 10.6-16.1) in 174 healthy children. The work was published simultaneously in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

In children with active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), adenosine deaminase 2 (ADA2) “beyond the upper limit of normal is strong evidence for concomitant” macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). “Our work represents a new method to diagnose this condition,” said lead investigator Pui Y. Lee, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

The hope, he said, is that the finding will lead to quicker recognition and treatment of MAS, a devastating complication of systemic JIA in which rampant inflammation begets further inflammation in a downward spiral that ultimately proves fatal in about 20% of cases. The problem is that the clinical features of MAS overlap with those of active systemic JIA, which makes early diagnosis difficult.

Ferritin and other common markers are not very specific unless “the cutoff is raised significantly to distinguish MAS from general inflammation. Most labs will not tell you ‘this is an active systemic JIA range; this is an MAS-like range.’ It’s hard for them to define that for you. ADA2 is more black and white; if you go above the upper limit, you most likely have MAS,” Dr. Lee explained at the meeting.

Potentially, “we can combine this test with other tests to define a single MAS panel,” he said.

ADA2 is measured by a simple, inexpensive enzyme assay that’s been around for 20 years, but it hasn’t caught on because the protein’s function is unknown and the clinical relevance of ADA2 levels has been uncertain. With the new findings, “it is our hope that ADA2 testing will become more available,” Dr. Lee said.

The protein appears to be a product of monocytes and macrophages, and a genetic deficiency has recently been linked to congenital vasculitis, which made Dr. Lee and colleagues curious about ADA2 in other rheumatic diseases. The first step was to define normal limits in healthy controls; the 13 U/L median in children proved to be a bit higher than in 150 healthy adults.

The team then found that levels were completely normal in 25 children with active Kawasaki disease, and only mildly elevated in 13 children with systemic lupus and 13 with juvenile dermatomyositis. The Kawasaki children, in particular “were highly inflamed, so this protein is not just simply a marker of inflammation,” Dr. Lee said.

They next turned to 120 children with JIA, with a mix of systemic and nonsystemic cases. “The ones with very high levels, far beyond the upper limit of normal, were” almost exclusively the 23 children with systemic JIA and clinically diagnosed MAS. “As long as [JIA children] didn’t have MAS, their levels were pretty much close to normal,” he said.

In eight MAS children with repeat testing, levels fell below the upper limit of normal with treatment and remission, but children prone to repeat MAS seemed to hover closer to the limit even when they were well.

Blood sample testing showed that interleukin-18 and interferon-gamma were the main drivers of ADA2 expression in the periphery, “which makes sense because these two cytokines are very involved in the process of MAS,” Dr. Lee said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Lee didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Lee PY et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 920.

ATLANTA – Adenosine deaminase 2 above the upper limit of normal is 86% sensitive and 94% specific for distinguishing macrophage activation syndrome from active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, making it perhaps the most potent blood marker yet identified to differentiate the two, according to a report presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The upper limit of normal was 27.8 U/L, two standard deviations above the median of 13 U/L (interquartile range, 10.6-16.1) in 174 healthy children. The work was published simultaneously in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

In children with active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), adenosine deaminase 2 (ADA2) “beyond the upper limit of normal is strong evidence for concomitant” macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). “Our work represents a new method to diagnose this condition,” said lead investigator Pui Y. Lee, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

The hope, he said, is that the finding will lead to quicker recognition and treatment of MAS, a devastating complication of systemic JIA in which rampant inflammation begets further inflammation in a downward spiral that ultimately proves fatal in about 20% of cases. The problem is that the clinical features of MAS overlap with those of active systemic JIA, which makes early diagnosis difficult.

Ferritin and other common markers are not very specific unless “the cutoff is raised significantly to distinguish MAS from general inflammation. Most labs will not tell you ‘this is an active systemic JIA range; this is an MAS-like range.’ It’s hard for them to define that for you. ADA2 is more black and white; if you go above the upper limit, you most likely have MAS,” Dr. Lee explained at the meeting.

Potentially, “we can combine this test with other tests to define a single MAS panel,” he said.

ADA2 is measured by a simple, inexpensive enzyme assay that’s been around for 20 years, but it hasn’t caught on because the protein’s function is unknown and the clinical relevance of ADA2 levels has been uncertain. With the new findings, “it is our hope that ADA2 testing will become more available,” Dr. Lee said.

The protein appears to be a product of monocytes and macrophages, and a genetic deficiency has recently been linked to congenital vasculitis, which made Dr. Lee and colleagues curious about ADA2 in other rheumatic diseases. The first step was to define normal limits in healthy controls; the 13 U/L median in children proved to be a bit higher than in 150 healthy adults.

The team then found that levels were completely normal in 25 children with active Kawasaki disease, and only mildly elevated in 13 children with systemic lupus and 13 with juvenile dermatomyositis. The Kawasaki children, in particular “were highly inflamed, so this protein is not just simply a marker of inflammation,” Dr. Lee said.

They next turned to 120 children with JIA, with a mix of systemic and nonsystemic cases. “The ones with very high levels, far beyond the upper limit of normal, were” almost exclusively the 23 children with systemic JIA and clinically diagnosed MAS. “As long as [JIA children] didn’t have MAS, their levels were pretty much close to normal,” he said.

In eight MAS children with repeat testing, levels fell below the upper limit of normal with treatment and remission, but children prone to repeat MAS seemed to hover closer to the limit even when they were well.

Blood sample testing showed that interleukin-18 and interferon-gamma were the main drivers of ADA2 expression in the periphery, “which makes sense because these two cytokines are very involved in the process of MAS,” Dr. Lee said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Lee didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Lee PY et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 920.

ATLANTA – Adenosine deaminase 2 above the upper limit of normal is 86% sensitive and 94% specific for distinguishing macrophage activation syndrome from active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, making it perhaps the most potent blood marker yet identified to differentiate the two, according to a report presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The upper limit of normal was 27.8 U/L, two standard deviations above the median of 13 U/L (interquartile range, 10.6-16.1) in 174 healthy children. The work was published simultaneously in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

In children with active systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), adenosine deaminase 2 (ADA2) “beyond the upper limit of normal is strong evidence for concomitant” macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). “Our work represents a new method to diagnose this condition,” said lead investigator Pui Y. Lee, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

The hope, he said, is that the finding will lead to quicker recognition and treatment of MAS, a devastating complication of systemic JIA in which rampant inflammation begets further inflammation in a downward spiral that ultimately proves fatal in about 20% of cases. The problem is that the clinical features of MAS overlap with those of active systemic JIA, which makes early diagnosis difficult.

Ferritin and other common markers are not very specific unless “the cutoff is raised significantly to distinguish MAS from general inflammation. Most labs will not tell you ‘this is an active systemic JIA range; this is an MAS-like range.’ It’s hard for them to define that for you. ADA2 is more black and white; if you go above the upper limit, you most likely have MAS,” Dr. Lee explained at the meeting.

Potentially, “we can combine this test with other tests to define a single MAS panel,” he said.

ADA2 is measured by a simple, inexpensive enzyme assay that’s been around for 20 years, but it hasn’t caught on because the protein’s function is unknown and the clinical relevance of ADA2 levels has been uncertain. With the new findings, “it is our hope that ADA2 testing will become more available,” Dr. Lee said.

The protein appears to be a product of monocytes and macrophages, and a genetic deficiency has recently been linked to congenital vasculitis, which made Dr. Lee and colleagues curious about ADA2 in other rheumatic diseases. The first step was to define normal limits in healthy controls; the 13 U/L median in children proved to be a bit higher than in 150 healthy adults.

The team then found that levels were completely normal in 25 children with active Kawasaki disease, and only mildly elevated in 13 children with systemic lupus and 13 with juvenile dermatomyositis. The Kawasaki children, in particular “were highly inflamed, so this protein is not just simply a marker of inflammation,” Dr. Lee said.

They next turned to 120 children with JIA, with a mix of systemic and nonsystemic cases. “The ones with very high levels, far beyond the upper limit of normal, were” almost exclusively the 23 children with systemic JIA and clinically diagnosed MAS. “As long as [JIA children] didn’t have MAS, their levels were pretty much close to normal,” he said.

In eight MAS children with repeat testing, levels fell below the upper limit of normal with treatment and remission, but children prone to repeat MAS seemed to hover closer to the limit even when they were well.

Blood sample testing showed that interleukin-18 and interferon-gamma were the main drivers of ADA2 expression in the periphery, “which makes sense because these two cytokines are very involved in the process of MAS,” Dr. Lee said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Lee didn’t have any disclosures.

SOURCE: Lee PY et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10), Abstract 920.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

Appropriate laboratory testing in Lyme disease

Lyme disease is a complex multisystem bacterial infection affecting the skin, joints, heart, and nervous system. The full spectrum of disease was first recognized and the disease was named in the 1970s during an outbreak of arthritis in children in the town of Lyme, Connecticut.1

This review describes the epidemiology and pathogenesis of Lyme disease, the advantages and disadvantages of current diagnostic methods, and diagnostic algorithms.

THE MOST COMMON TICK-BORNE INFECTION IN NORTH AMERICA

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne infection in North America.2,3 In the United States, more than 30,000 cases are reported annually. In fact, in 2017, the number of cases was about 42,000, a 16% increase from the previous year, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Infected nymphs account for most cases.

The infection is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a particularly arthritogenic spirochete transmitted by Ixodes scapularis (the black-legged deer tick, (Figure 1) and Ixodes pacificus (the Western black-legged tick). Although the infection can occur at any time of the year, its peak incidence is in May to late September, coinciding with increased outdoor recreational activity in areas where ticks live.3,4 The typical tick habitat consists of deciduous woodland with sufficient humidity provided by a good layer of decaying vegetation. However, people can contract Lyme disease in their own backyard.3

Most cases of Lyme disease are seen in the northeastern United States, mainly in suburban and rural areas.2,3 Other areas affected include the midwestern states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, as well as northern California.4 Fourteen states and the District of Columbia report a high average incidence (> 10 cases per 100,000 persons) (Table 1).2

FIRST COMES IgM, THEN IgG

The pathogenesis and the different stages of infection should inform laboratory testing in Lyme disease.

It is estimated that only 5% of infected ticks that bite people actually transmit their spirochetes to the human host.5 However, once infected, the patient’s innate immune system mounts a response that results in the classic erythema migrans rash at the bite site. A rash develops in only about 85% of patients who are infected and can appear at any time between 3 and 30 days, but most commonly after 7 days. Hence, a rash occurring within the first few hours of tick contact is not erythema migrans and does not indicate infection, but rather an early reaction to tick salivary antigens.5

Antibody levels remain below the detection limits of currently available serologic tests in the first 7 days after exposure. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody titers peak between 8 and 14 days after tick contact, but IgM antibodies may never develop if the patient is started on early appropriate antimicrobial therapy.5

If the infection is not treated, the spirochete may disseminate through the blood from the bite site to different tissues.3 Both cell-mediated and antibody-mediated immunity swing into action to kill the spirochetes at this stage. The IgM antibody response occurs in 1 to 2 weeks, followed by a robust IgG response in 2 to 4 weeks.6

Because IgM can also cross-react with antigens other than those associated with B burgdorferi, the IgM test is less specific than the IgG test for Lyme disease.

Once a patient is exposed and mounts an antibody-mediated response to the spirochete, the antibody profile may persist for months to years, even after successful antibiotic treatment and cure of the disease.5

Despite the immune system’s robust series of defenses, untreated B burgdorferi infection can persist, as the organism has a bag of tricks to evade destruction. It can decrease its expression of specific immunogenic surface-exposed proteins, change its antigenic properties through recombination, and bind to the patient’s extracellular matrix proteins to facilitate further dissemination.3

Certain host-genetic factors also play a role in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease, such as the HLA-DR4 allele, which has been associated with antibiotic-refractory Lyme-related arthritis.3

LYME DISEASE EVOLVES THROUGH STAGES

Lyme disease evolves through stages broadly classified as early and late infection, with significant variability in its presentation.7

Early infection

Early disease is further subdivided into “localized” infection (stage 1), characterized by a single erythema migrans lesion and local lymphadenopathy, and “disseminated” infection (stage 2), associated with multiple erythema migrans lesions distant from the bite site, facial nerve palsy, radiculoneuritis, meningitis, carditis, or migratory arthritis or arthralgia.8

Highly specific physical findings include erythema migrans, cranial nerve palsy, high-grade or progressive conduction block, and recurrent migratory polyarthritis. Less specific symptoms and signs of Lyme disease include arthralgia, myalgia, neck stiffness, palpitations, and myocarditis.5

Erythema migrans lesions are evident in at least 85% of patients with early disease.9 If they are not apparent on physical examination, they may be located at hidden sites and may be atypical in appearance or transient.5

If treatment is not started in the initial stage of the disease, 60% of infected patients may develop disseminated infection.5 Progressive, untreated infection can manifest with Lyme arthritis and neuroborreliosis.7

Noncutaneous manifestations are less common now than in the past due to increased awareness of the disease and early initiation of treatment.10

Late infection

Manifestations of late (stage 3) infection include oligoarthritis (affecting any joint but often the knee) and neuroborreliosis. Clinical signs and symptoms of Lyme disease may take months to resolve even after appropriate antimicrobial therapy is completed. This should not be interpreted as ongoing, persistent infection, but as related to host immune-mediated activity.5

INTERPRET LABORATORY RESULTS BASED ON PRETEST PROBABILITY

The usefulness of a laboratory test depends on the individual patient’s pretest probability of infection, which in turn depends on the patient’s epidemiologic risk of exposure and clinical features of Lyme disease. Patients with a high pretest probability—eg, a history of a tick bite followed by the classic erythema migrans rash—do not need testing and can start antimicrobial therapy right away.11

Serologic tests are the gold standard

Prompt diagnosis is important, as early Lyme disease is easily treatable without any future sequelae.11

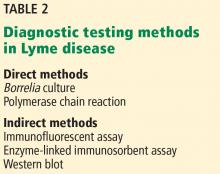

Tests for Lyme disease can be divided into direct methods, which detect the spirochete itself by culture or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and indirect methods, which detect antibodies (Table 2). Direct tests lack sensitivity for Lyme disease; hence, serologic tests remain the gold standard. Currently recommended is a standard 2-tier testing strategy using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) followed by Western blot for confirmation.

DIRECT METHODS

Culture lacks sensitivity

A number of factors limit the sensitivity of direct culture for diagnosing Lyme disease. B burgdorferi does not grow easily in culture, requiring special media, low temperatures, and long periods of incubation. Only a relatively few spirochetes are present in human tissues and body fluids to begin with, and bacterial counts are further reduced with duration and dissemination of infection.5 All of these limit the possibility of detecting this organism.

Polymerase chain reaction may help in some situations

Molecular assays are not part of the standard evaluation and should be used only in conjunction with serologic testing.7 These tests have high specificity but lack consistent sensitivity.

That said, PCR testing may be useful:

- In early infection, before antibody responses develop

- In reinfection, when serologic tests are not reliable because the antibodies persist for many years after an infection in many patients

- In endemic areas where serologic testing has high false-positive rates due to high baseline population seropositivity for anti-Borrelia antibodies caused by subclinical infection.3

PCR assays that target plasmid-borne genes encoding outer surface proteins A and C (OspA and OspC) and VisE (variable major protein-like sequence, expressed) are more sensitive than those that detect chromosomal 16s ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) genes, as plasmid-rich “blebs” are shed in larger concentrations than chromosomal DNA during active infection.7 However, these plasmid-contained genes persist in body tissues and fluids even after the infection is cleared, and their detection may not necessarily correlate with ongoing disease.8 Detection of chromosomal 16s rRNA genes is a better predictor of true organism viability.

The sensitivity of PCR for borrelial DNA depends on the type of sample. If a skin biopsy sample is taken of the leading edge of an erythema migrans lesion, the sensitivity is 69% and the specificity is 100%. In patients with Lyme arthritis, PCR of the synovial fluid has a sensitivity of up to 80%. However, the sensitivity of PCR of the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease is only 19%.7 PCR of other clinical samples, including blood and urine, is not recommended, as spirochetes are primarily confined to tissues, and very few are present in these body fluids.3,12

The disadvantage of PCR is that a positive result does not always mean active infection, as the DNA of the dead microbe persists for several months even after successful treatment.8

INDIRECT METHODS

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISAs detect anti-Borrelia antibodies. Early-generation ELISAs, still used in many laboratories, use whole-cell extracts of B burgdorferi. Examples are the Vidas Lyme screen (Biomérieux, biomerieux-usa.com) and the Wampole B burgdorferi IgG/M EIA II assay (Alere, www.alere.com). Newer ELISAs use recombinant proteins.13

Three major targets for ELISA antibodies are flagellin (Fla), outer surface protein C (OspC), and VisE, especially the invariable region 6 (IR6). Among these, VisE-IR6 is the most conserved region in B burgdorferi.

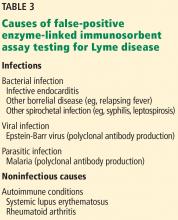

Early-generation assays have a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 72%.11 However, the patient’s serum may have antibodies that cross-react with unrelated bacterial antigens, leading to false-positive results (Table 3). Whole-cell sonicate assays are not recommended as an independent test and must be confirmed with Western blot testing when assay results are indeterminate or positive.11

Newer-generation ELISAs detect antibodies targeting recombinant proteins of VisE, especially a synthetic peptide C6, within IR6.13 VisE-IR6 is the most conserved region of the B burgdorferi complex, and its detection is a highly specific finding, supporting the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Antibodies against VisE-IR6 antigen are the earliest to develop.5 An example of a newer-generation serologic test is the VisE C6 Lyme EIA kit, approved as a first-tier test by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001. This test has a specificity of 99%,14,15 and its specificity is further increased when used in conjunction with Western blot (99.5%).15 The advantage of the C6 antibody test is that it is more sensitive than 2-tier testing during early infection (sensitivity 29%–74% vs 17%–40% in early localized infection, and 56%–90% vs 27%–78% in early disseminated infection).6

During early infection, older and newer ELISAs are less sensitive because of the limited number of antigens expressed at this stage.13 All patients suspected of having early Lyme disease who are seronegative at initial testing should have follow-up testing to look for seroconversion.13

Western blot

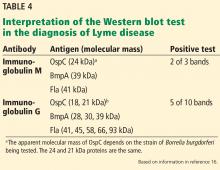

Western blot (immunoblot) testing identifies IgM and IgG antibodies against specific B burgdorferi antigens. It is considered positive if it detects at least 2 of a possible 3 specific IgM bands in the first 4 weeks of disease or at least 5 of 10 specific IgG bands after 4 weeks of disease (Table 4 and Figure 2).16

The nature of the bands indicates the duration of infection: Western blot bands against 23-kD OspC and 41-kD FlaB are seen in early localized infection, whereas bands against all 3 B burgdorferi proteins will be seen after several weeks of disease.17 The IgM result should be interpreted carefully, as only 2 bands are required for the test to be positive, and IgM binds to antigen less specifically than IgG.12

Interpreting the IgM Western blot test: The ‘1-month rule’

If clinical symptoms and signs of Lyme disease have been present for more than 1 month, IgM reactivity alone should not be used to support the diagnosis, in view of the likelihood of a false-positive test result in this situation.18 This is called the “1-month rule” in the diagnosis of Lyme disease.13

In early localized infection, Western blot is only half as sensitive as ELISA testing. Since the overall sensitivity of a 2-step algorithm is equal to that of its least sensitive component, 2-tiered testing is not useful in early disease.13

Although currently considered the most specific test for confirmation of Lyme disease, Western blot has limitations. It is technically and interpretively complex and is thus not universally available.13 The blots are scored by visual examination, compromising the reproducibility of the test, although densitometric blot analysis techniques and automated scanning and scoring attempt to address some of these limitations.13 Like the ELISA, Western blot can have false-positive results in healthy individuals without tick exposure, as nonspecific IgM immunoblots develop faint bands. This is because of cross-reaction between B burgdorferi antigens and antigens from other microorganisms. Around 50% of healthy adults show low-level serum IgG reactivity against the FlaB antigen, leading to false-positive results as well. In cases in which the Western blot result is indeterminate, other etiologies must be considered.

False-positive IgM Western blots are a significant problem. In a 5-year retrospective study done at 63 US Air Force healthcare facilities, 113 (53.3%) of 212 IgM Western blots were falsely positive.19 A false-positive test was defined as one that failed to meet seropositivity (a first-tier test omitted or negative, > 30 days of symptoms with negative IgG blot), lack of exposure including residing in areas without documented tick habitats, patients having atypical or no symptoms, and negative serology within 30 days of a positive test.

In a similar study done in a highly endemic area, 50 (27.5%) of 182 patients had a false-positive test.20 Physicians need to be careful when interpreting IgM Western blots. It is always important to consider locale, epidemiology, and symptoms when interpreting the test.

Limitations of serologic tests for Lyme disease

Currently available serologic tests have inherent limitations:

- Antibodies against B burgdorferi take at least 1 week to develop

- The background rate of seropositivity in endemic areas can be up to 4%, affecting the utility of a positive test result

- Serologic tests cannot be used as tests of cure because antibodies can persist for months to years even after appropriate antimicrobial therapy and cure of disease; thus, a positive serologic result could represent active infection or remote exposure21

- Antibodies can cross-react with related bacteria, including other borrelial or treponemal spirochetes

- False-positive serologic test results can also occur in association with other medical conditions such as polyclonal gammopathies and systemic lupus erythematosus.12

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TESTING

Standard 2-tier testing

The CDC released recommendations for diagnosing Lyme disease after a second national conference of serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease in October 1994.18 The 2-tiered testing method, involving a sensitive ELISA followed by the Western blot to confirm positive and indeterminate ELISA results, was suggested as the gold standard for diagnosis (Figure 3). Of note, negative ELISA results do not require further testing.11

The sensitivity of 2-tiered testing depends on the stage of the disease. Unfortunately, this method has a wide range of sensitivity (17% to 78%) in stage 1 disease. In the same stage, the sensitivity increases from 14.1% in patients with a single erythema migrans lesion and early localized infection to 65.4% in those with multiple lesions. The algorithm has excellent sensitivity in late stage 3 infection (96% to 100%).5

A 2-step ELISA algorithm

A 2-step ELISA algorithm (without the Western blot) that includes the whole-cell sonicate assay followed by the VisE C6 peptide assay actually showed higher sensitivity and comparable specificity compared with 2-tiered testing in early localized disease (sensitivity 61%–74% vs 29%–48%, respectively; specificity 99.5% for both methods).22 This higher sensitivity was even more pronounced in early disseminated infection (sensitivity 100% vs 40%, respectively). By late infection, the sensitivities of both testing strategies reached 100%. Compared with the Western blot, the 2-step ELISA algorithm was simpler to execute in a reproducible fashion.5

The Infectious Diseases Society of America is revising its current guidelines, with an update expected late this year, which may shift the recommendation from 2-tiered testing to the 2-step ELISA algorithm.

Multiplex testing

To overcome the intrinsic problems of protein-based assays, a multiplexed, array-based assay for the diagnosis of tick-borne infections called Tick-Borne Disease Serochip (TBD-Serochip) was established using recombinant antigens that identify key immunodominant epitopes.8 More studies are needed to establish the validity and usefulness of these tests in clinical practice.

Who should not be tested?

The American College of Physicians6 recommends against testing in patients:

- Presenting with nonspecific symptoms (eg, headache, myalgia, fatigue, arthralgia) without objective signs of Lyme disease

- With low pretest probability of infection based on epidemiologic exposures and clinical features

- Living in Lyme-endemic areas with no history of tick exposure6

- Presenting less than 1 week after tick exposure5

- Seeking a test of cure for treated Lyme disease.

DIAGNOSIS IN SPECIAL SITUATIONS

Early Lyme disease

The classic erythema migrans lesion on physical examination of a patient with suspected Lyme disease is diagnostic and does not require laboratory confirmation.10

In ambiguous cases, 2-tiered testing of a serum sample during the acute presentation and again 4 to 6 weeks later can be useful. In patients who remain seronegative on paired serum samples despite symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks and no antibiotic treatment in the interim, the diagnosis of Lyme disease is unlikely, and another diagnosis should be sought.3

Antimicrobial therapy may block the serologic response; hence, negative serologic testing in patients started on empiric antibiotics should not rule out Lyme disease.6

PCR or bacterial culture testing is not recommended in the evaluation of suspected early Lyme disease.

Central nervous system Lyme disease

Central nervous system Lyme disease is diagnosed by 2-tiered testing using peripheral blood samples because all patients with this infectious manifestation should have mounted an adequate IgG response in the blood.11

B cells migrate to and proliferate inside the central nervous system, leading to intrathecal production of anti-Borrelia antibodies. An index of cerebrospinal fluid to serum antibody greater than 1 is thus also indicative of neuroborreliosis.12 Thus, performing lumbar puncture to detect intrathecal production of antibodies may support the diagnosis of central nervous system Lyme disease; however, it is not necessary.11

Antibodies persist in the central nervous system for many years after appropriate antimicrobial treatment.

Lyme arthritis

Articular involvement in Lyme disease is characterized by a robust humoral response such that a negative IgG serologic test virtually rules out Lyme arthritis.23 PCR testing of synovial fluid for borrelial DNA has a sensitivity of 80% but may become falsely negative after 1 to 2 months of antibiotic treatment.24,25 In an algorithm suggested by Puius et al,23 PCR testing of synovial fluid should be done in patients who have minimal to no response after 2 months of appropriate oral antimicrobial therapy to determine whether intravenous antibiotics are merited.

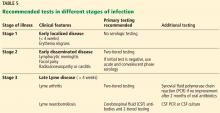

Table 5 summarizes the tests of choice in different clinical stages of infection.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to acknowledge Anita Modi, MD, and Ceena N. Jacob, MD, for reviewing the manuscript and providing valuable suggestions, and Belinda Yen-Lieberman, PhD, for contributing pictures of the Western blot test results.

- Steere AC, Malawista SE, Snydman DR, et al. Lyme arthritis: an epidemic of oligoarticular arthritis in children and adults in three Connecticut communities. Arthritis Rheum 1977; 20(1):7–17. doi:10.1002/art.1780200102

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Lyme disease: recent surveillance data. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance/recent-surveillance-data.html. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 2012; 379(9814):461–473. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7

- Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2015; 29(2):269–280. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.004

- Schriefer ME. Lyme disease diagnosis: serology. Clin Lab Med 2015; 35(4):797–814. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.08.001

- Hu LT. Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164(9):ITC65–ITC80. doi:10.7326/AITC201605030

- Alby K, Capraro GA. Alternatives to serologic testing for diagnosis of Lyme disease. Clin Lab Med 2015; 35(4):815–825. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2015.07.005

- Dumler JS. Molecular diagnosis of Lyme disease: review and meta-analysis. Mol Diagn 2001; 6(1):1–11. doi:10.1054/modi.2001.21898

- Wormser GP, McKenna D, Carlin J, et al. Brief communication: hematogenous dissemination in early Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142(9):751–755. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00011

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43(9):1089–1134. doi:10.1086/508667

- Guidelines for laboratory evaluation in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127(12):1106–1108. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00010

- Halperin JJ. Lyme disease: a multisystem infection that affects the nervous system. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2012; 18(6 Infectious Disease):1338–1350. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000423850.24900.3a

- Branda JA, Body BA, Boyle J, et al. Advances in serodiagnostic testing for Lyme disease are at hand. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(7):1133–1139. doi:10.1093/cid/cix943

- Immunetics. Immunetics® C6 Lyme ELISA™ Kit. http://www.oxfordimmunotec.com/international/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/CF-E601-096A-C6-Pkg-Insrt.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2019.

- Civelek M, Lusis AJ. Systems genetics approaches to understand complex traits. Nat Rev Genet 2014; 15(1):34–48. doi:10.1038/nrg3575

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1995; 44(31):590–591. pmid:7623762

- Steere AC, Mchugh G, Damle N, Sikand VK. Prospective study of serologic tests for Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47(2):188–195. doi:10.1086/589242

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. JAMA 1995; 274(12):937. pmid:7674514

- Webber BJ, Burganowski RP, Colton L, Escobar JD, Pathak SR, Gambino-Shirley KJ. Lyme disease overdiagnosis in a large healthcare system: a population-based, retrospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2019.02.020. Epub ahead of print.

- Seriburi V, Ndukwe N, Chang Z, Cox ME, Wormser GP. High frequency of false positive IgM immunoblots for Borrelia burgdorferi in clinical practice. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18(12):1236–1240. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03749.x

- Hilton E, DeVoti J, Benach JL, et al. Seroprevalence and seroconversion for tick-borne diseases in a high-risk population in the northeast United States. Am J Med 1999; 106(4):404–409. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00046-7

- Branda JA, Linskey K, Kim YA, Steere AC, Ferraro MJ. Two-tiered antibody testing for Lyme disease with use of 2 enzyme immunoassays, a whole-cell sonicate enzyme immunoassay followed by a VlsE C6 peptide enzyme immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(6):541–547. doi:10.1093/cid/cir464

- Puius YA, Kalish RA. Lyme arthritis: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2008; 22(2):289–300. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.014

- Nocton JJ, Dressler F, Rutledge BJ, Rys PN, Persing DH, Steere AC. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid from patients with Lyme arthritis. N Engl J Med 1994; 330(4):229–234. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401273300401

- Liebling MR, Nishio MJ, Rodriguez A, Sigal LH, Jin T, Louie JS. The polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Borrelia burgdorferi in human body fluids. Arthritis Rheum 1993; 36(5):665–975. doi:10.1002/art.1780360514

Lyme disease is a complex multisystem bacterial infection affecting the skin, joints, heart, and nervous system. The full spectrum of disease was first recognized and the disease was named in the 1970s during an outbreak of arthritis in children in the town of Lyme, Connecticut.1

This review describes the epidemiology and pathogenesis of Lyme disease, the advantages and disadvantages of current diagnostic methods, and diagnostic algorithms.

THE MOST COMMON TICK-BORNE INFECTION IN NORTH AMERICA

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne infection in North America.2,3 In the United States, more than 30,000 cases are reported annually. In fact, in 2017, the number of cases was about 42,000, a 16% increase from the previous year, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Infected nymphs account for most cases.

The infection is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a particularly arthritogenic spirochete transmitted by Ixodes scapularis (the black-legged deer tick, (Figure 1) and Ixodes pacificus (the Western black-legged tick). Although the infection can occur at any time of the year, its peak incidence is in May to late September, coinciding with increased outdoor recreational activity in areas where ticks live.3,4 The typical tick habitat consists of deciduous woodland with sufficient humidity provided by a good layer of decaying vegetation. However, people can contract Lyme disease in their own backyard.3

Most cases of Lyme disease are seen in the northeastern United States, mainly in suburban and rural areas.2,3 Other areas affected include the midwestern states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, as well as northern California.4 Fourteen states and the District of Columbia report a high average incidence (> 10 cases per 100,000 persons) (Table 1).2

FIRST COMES IgM, THEN IgG

The pathogenesis and the different stages of infection should inform laboratory testing in Lyme disease.

It is estimated that only 5% of infected ticks that bite people actually transmit their spirochetes to the human host.5 However, once infected, the patient’s innate immune system mounts a response that results in the classic erythema migrans rash at the bite site. A rash develops in only about 85% of patients who are infected and can appear at any time between 3 and 30 days, but most commonly after 7 days. Hence, a rash occurring within the first few hours of tick contact is not erythema migrans and does not indicate infection, but rather an early reaction to tick salivary antigens.5

Antibody levels remain below the detection limits of currently available serologic tests in the first 7 days after exposure. Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody titers peak between 8 and 14 days after tick contact, but IgM antibodies may never develop if the patient is started on early appropriate antimicrobial therapy.5

If the infection is not treated, the spirochete may disseminate through the blood from the bite site to different tissues.3 Both cell-mediated and antibody-mediated immunity swing into action to kill the spirochetes at this stage. The IgM antibody response occurs in 1 to 2 weeks, followed by a robust IgG response in 2 to 4 weeks.6

Because IgM can also cross-react with antigens other than those associated with B burgdorferi, the IgM test is less specific than the IgG test for Lyme disease.

Once a patient is exposed and mounts an antibody-mediated response to the spirochete, the antibody profile may persist for months to years, even after successful antibiotic treatment and cure of the disease.5

Despite the immune system’s robust series of defenses, untreated B burgdorferi infection can persist, as the organism has a bag of tricks to evade destruction. It can decrease its expression of specific immunogenic surface-exposed proteins, change its antigenic properties through recombination, and bind to the patient’s extracellular matrix proteins to facilitate further dissemination.3

Certain host-genetic factors also play a role in the pathogenesis of Lyme disease, such as the HLA-DR4 allele, which has been associated with antibiotic-refractory Lyme-related arthritis.3

LYME DISEASE EVOLVES THROUGH STAGES

Lyme disease evolves through stages broadly classified as early and late infection, with significant variability in its presentation.7

Early infection

Early disease is further subdivided into “localized” infection (stage 1), characterized by a single erythema migrans lesion and local lymphadenopathy, and “disseminated” infection (stage 2), associated with multiple erythema migrans lesions distant from the bite site, facial nerve palsy, radiculoneuritis, meningitis, carditis, or migratory arthritis or arthralgia.8

Highly specific physical findings include erythema migrans, cranial nerve palsy, high-grade or progressive conduction block, and recurrent migratory polyarthritis. Less specific symptoms and signs of Lyme disease include arthralgia, myalgia, neck stiffness, palpitations, and myocarditis.5

Erythema migrans lesions are evident in at least 85% of patients with early disease.9 If they are not apparent on physical examination, they may be located at hidden sites and may be atypical in appearance or transient.5

If treatment is not started in the initial stage of the disease, 60% of infected patients may develop disseminated infection.5 Progressive, untreated infection can manifest with Lyme arthritis and neuroborreliosis.7

Noncutaneous manifestations are less common now than in the past due to increased awareness of the disease and early initiation of treatment.10

Late infection

Manifestations of late (stage 3) infection include oligoarthritis (affecting any joint but often the knee) and neuroborreliosis. Clinical signs and symptoms of Lyme disease may take months to resolve even after appropriate antimicrobial therapy is completed. This should not be interpreted as ongoing, persistent infection, but as related to host immune-mediated activity.5

INTERPRET LABORATORY RESULTS BASED ON PRETEST PROBABILITY

The usefulness of a laboratory test depends on the individual patient’s pretest probability of infection, which in turn depends on the patient’s epidemiologic risk of exposure and clinical features of Lyme disease. Patients with a high pretest probability—eg, a history of a tick bite followed by the classic erythema migrans rash—do not need testing and can start antimicrobial therapy right away.11

Serologic tests are the gold standard

Prompt diagnosis is important, as early Lyme disease is easily treatable without any future sequelae.11

Tests for Lyme disease can be divided into direct methods, which detect the spirochete itself by culture or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and indirect methods, which detect antibodies (Table 2). Direct tests lack sensitivity for Lyme disease; hence, serologic tests remain the gold standard. Currently recommended is a standard 2-tier testing strategy using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) followed by Western blot for confirmation.

DIRECT METHODS

Culture lacks sensitivity

A number of factors limit the sensitivity of direct culture for diagnosing Lyme disease. B burgdorferi does not grow easily in culture, requiring special media, low temperatures, and long periods of incubation. Only a relatively few spirochetes are present in human tissues and body fluids to begin with, and bacterial counts are further reduced with duration and dissemination of infection.5 All of these limit the possibility of detecting this organism.

Polymerase chain reaction may help in some situations

Molecular assays are not part of the standard evaluation and should be used only in conjunction with serologic testing.7 These tests have high specificity but lack consistent sensitivity.

That said, PCR testing may be useful:

- In early infection, before antibody responses develop

- In reinfection, when serologic tests are not reliable because the antibodies persist for many years after an infection in many patients

- In endemic areas where serologic testing has high false-positive rates due to high baseline population seropositivity for anti-Borrelia antibodies caused by subclinical infection.3

PCR assays that target plasmid-borne genes encoding outer surface proteins A and C (OspA and OspC) and VisE (variable major protein-like sequence, expressed) are more sensitive than those that detect chromosomal 16s ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) genes, as plasmid-rich “blebs” are shed in larger concentrations than chromosomal DNA during active infection.7 However, these plasmid-contained genes persist in body tissues and fluids even after the infection is cleared, and their detection may not necessarily correlate with ongoing disease.8 Detection of chromosomal 16s rRNA genes is a better predictor of true organism viability.

The sensitivity of PCR for borrelial DNA depends on the type of sample. If a skin biopsy sample is taken of the leading edge of an erythema migrans lesion, the sensitivity is 69% and the specificity is 100%. In patients with Lyme arthritis, PCR of the synovial fluid has a sensitivity of up to 80%. However, the sensitivity of PCR of the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease is only 19%.7 PCR of other clinical samples, including blood and urine, is not recommended, as spirochetes are primarily confined to tissues, and very few are present in these body fluids.3,12

The disadvantage of PCR is that a positive result does not always mean active infection, as the DNA of the dead microbe persists for several months even after successful treatment.8

INDIRECT METHODS

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISAs detect anti-Borrelia antibodies. Early-generation ELISAs, still used in many laboratories, use whole-cell extracts of B burgdorferi. Examples are the Vidas Lyme screen (Biomérieux, biomerieux-usa.com) and the Wampole B burgdorferi IgG/M EIA II assay (Alere, www.alere.com). Newer ELISAs use recombinant proteins.13

Three major targets for ELISA antibodies are flagellin (Fla), outer surface protein C (OspC), and VisE, especially the invariable region 6 (IR6). Among these, VisE-IR6 is the most conserved region in B burgdorferi.

Early-generation assays have a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 72%.11 However, the patient’s serum may have antibodies that cross-react with unrelated bacterial antigens, leading to false-positive results (Table 3). Whole-cell sonicate assays are not recommended as an independent test and must be confirmed with Western blot testing when assay results are indeterminate or positive.11

Newer-generation ELISAs detect antibodies targeting recombinant proteins of VisE, especially a synthetic peptide C6, within IR6.13 VisE-IR6 is the most conserved region of the B burgdorferi complex, and its detection is a highly specific finding, supporting the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Antibodies against VisE-IR6 antigen are the earliest to develop.5 An example of a newer-generation serologic test is the VisE C6 Lyme EIA kit, approved as a first-tier test by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001. This test has a specificity of 99%,14,15 and its specificity is further increased when used in conjunction with Western blot (99.5%).15 The advantage of the C6 antibody test is that it is more sensitive than 2-tier testing during early infection (sensitivity 29%–74% vs 17%–40% in early localized infection, and 56%–90% vs 27%–78% in early disseminated infection).6

During early infection, older and newer ELISAs are less sensitive because of the limited number of antigens expressed at this stage.13 All patients suspected of having early Lyme disease who are seronegative at initial testing should have follow-up testing to look for seroconversion.13

Western blot

Western blot (immunoblot) testing identifies IgM and IgG antibodies against specific B burgdorferi antigens. It is considered positive if it detects at least 2 of a possible 3 specific IgM bands in the first 4 weeks of disease or at least 5 of 10 specific IgG bands after 4 weeks of disease (Table 4 and Figure 2).16

The nature of the bands indicates the duration of infection: Western blot bands against 23-kD OspC and 41-kD FlaB are seen in early localized infection, whereas bands against all 3 B burgdorferi proteins will be seen after several weeks of disease.17 The IgM result should be interpreted carefully, as only 2 bands are required for the test to be positive, and IgM binds to antigen less specifically than IgG.12

Interpreting the IgM Western blot test: The ‘1-month rule’

If clinical symptoms and signs of Lyme disease have been present for more than 1 month, IgM reactivity alone should not be used to support the diagnosis, in view of the likelihood of a false-positive test result in this situation.18 This is called the “1-month rule” in the diagnosis of Lyme disease.13

In early localized infection, Western blot is only half as sensitive as ELISA testing. Since the overall sensitivity of a 2-step algorithm is equal to that of its least sensitive component, 2-tiered testing is not useful in early disease.13

Although currently considered the most specific test for confirmation of Lyme disease, Western blot has limitations. It is technically and interpretively complex and is thus not universally available.13 The blots are scored by visual examination, compromising the reproducibility of the test, although densitometric blot analysis techniques and automated scanning and scoring attempt to address some of these limitations.13 Like the ELISA, Western blot can have false-positive results in healthy individuals without tick exposure, as nonspecific IgM immunoblots develop faint bands. This is because of cross-reaction between B burgdorferi antigens and antigens from other microorganisms. Around 50% of healthy adults show low-level serum IgG reactivity against the FlaB antigen, leading to false-positive results as well. In cases in which the Western blot result is indeterminate, other etiologies must be considered.

False-positive IgM Western blots are a significant problem. In a 5-year retrospective study done at 63 US Air Force healthcare facilities, 113 (53.3%) of 212 IgM Western blots were falsely positive.19 A false-positive test was defined as one that failed to meet seropositivity (a first-tier test omitted or negative, > 30 days of symptoms with negative IgG blot), lack of exposure including residing in areas without documented tick habitats, patients having atypical or no symptoms, and negative serology within 30 days of a positive test.

In a similar study done in a highly endemic area, 50 (27.5%) of 182 patients had a false-positive test.20 Physicians need to be careful when interpreting IgM Western blots. It is always important to consider locale, epidemiology, and symptoms when interpreting the test.

Limitations of serologic tests for Lyme disease

Currently available serologic tests have inherent limitations:

- Antibodies against B burgdorferi take at least 1 week to develop

- The background rate of seropositivity in endemic areas can be up to 4%, affecting the utility of a positive test result

- Serologic tests cannot be used as tests of cure because antibodies can persist for months to years even after appropriate antimicrobial therapy and cure of disease; thus, a positive serologic result could represent active infection or remote exposure21

- Antibodies can cross-react with related bacteria, including other borrelial or treponemal spirochetes

- False-positive serologic test results can also occur in association with other medical conditions such as polyclonal gammopathies and systemic lupus erythematosus.12

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TESTING

Standard 2-tier testing

The CDC released recommendations for diagnosing Lyme disease after a second national conference of serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease in October 1994.18 The 2-tiered testing method, involving a sensitive ELISA followed by the Western blot to confirm positive and indeterminate ELISA results, was suggested as the gold standard for diagnosis (Figure 3). Of note, negative ELISA results do not require further testing.11

The sensitivity of 2-tiered testing depends on the stage of the disease. Unfortunately, this method has a wide range of sensitivity (17% to 78%) in stage 1 disease. In the same stage, the sensitivity increases from 14.1% in patients with a single erythema migrans lesion and early localized infection to 65.4% in those with multiple lesions. The algorithm has excellent sensitivity in late stage 3 infection (96% to 100%).5

A 2-step ELISA algorithm

A 2-step ELISA algorithm (without the Western blot) that includes the whole-cell sonicate assay followed by the VisE C6 peptide assay actually showed higher sensitivity and comparable specificity compared with 2-tiered testing in early localized disease (sensitivity 61%–74% vs 29%–48%, respectively; specificity 99.5% for both methods).22 This higher sensitivity was even more pronounced in early disseminated infection (sensitivity 100% vs 40%, respectively). By late infection, the sensitivities of both testing strategies reached 100%. Compared with the Western blot, the 2-step ELISA algorithm was simpler to execute in a reproducible fashion.5

The Infectious Diseases Society of America is revising its current guidelines, with an update expected late this year, which may shift the recommendation from 2-tiered testing to the 2-step ELISA algorithm.

Multiplex testing

To overcome the intrinsic problems of protein-based assays, a multiplexed, array-based assay for the diagnosis of tick-borne infections called Tick-Borne Disease Serochip (TBD-Serochip) was established using recombinant antigens that identify key immunodominant epitopes.8 More studies are needed to establish the validity and usefulness of these tests in clinical practice.

Who should not be tested?

The American College of Physicians6 recommends against testing in patients:

- Presenting with nonspecific symptoms (eg, headache, myalgia, fatigue, arthralgia) without objective signs of Lyme disease

- With low pretest probability of infection based on epidemiologic exposures and clinical features

- Living in Lyme-endemic areas with no history of tick exposure6

- Presenting less than 1 week after tick exposure5

- Seeking a test of cure for treated Lyme disease.

DIAGNOSIS IN SPECIAL SITUATIONS

Early Lyme disease

The classic erythema migrans lesion on physical examination of a patient with suspected Lyme disease is diagnostic and does not require laboratory confirmation.10

In ambiguous cases, 2-tiered testing of a serum sample during the acute presentation and again 4 to 6 weeks later can be useful. In patients who remain seronegative on paired serum samples despite symptoms lasting longer than 6 weeks and no antibiotic treatment in the interim, the diagnosis of Lyme disease is unlikely, and another diagnosis should be sought.3

Antimicrobial therapy may block the serologic response; hence, negative serologic testing in patients started on empiric antibiotics should not rule out Lyme disease.6

PCR or bacterial culture testing is not recommended in the evaluation of suspected early Lyme disease.

Central nervous system Lyme disease

Central nervous system Lyme disease is diagnosed by 2-tiered testing using peripheral blood samples because all patients with this infectious manifestation should have mounted an adequate IgG response in the blood.11

B cells migrate to and proliferate inside the central nervous system, leading to intrathecal production of anti-Borrelia antibodies. An index of cerebrospinal fluid to serum antibody greater than 1 is thus also indicative of neuroborreliosis.12 Thus, performing lumbar puncture to detect intrathecal production of antibodies may support the diagnosis of central nervous system Lyme disease; however, it is not necessary.11

Antibodies persist in the central nervous system for many years after appropriate antimicrobial treatment.

Lyme arthritis

Articular involvement in Lyme disease is characterized by a robust humoral response such that a negative IgG serologic test virtually rules out Lyme arthritis.23 PCR testing of synovial fluid for borrelial DNA has a sensitivity of 80% but may become falsely negative after 1 to 2 months of antibiotic treatment.24,25 In an algorithm suggested by Puius et al,23 PCR testing of synovial fluid should be done in patients who have minimal to no response after 2 months of appropriate oral antimicrobial therapy to determine whether intravenous antibiotics are merited.

Table 5 summarizes the tests of choice in different clinical stages of infection.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to acknowledge Anita Modi, MD, and Ceena N. Jacob, MD, for reviewing the manuscript and providing valuable suggestions, and Belinda Yen-Lieberman, PhD, for contributing pictures of the Western blot test results.

Lyme disease is a complex multisystem bacterial infection affecting the skin, joints, heart, and nervous system. The full spectrum of disease was first recognized and the disease was named in the 1970s during an outbreak of arthritis in children in the town of Lyme, Connecticut.1

This review describes the epidemiology and pathogenesis of Lyme disease, the advantages and disadvantages of current diagnostic methods, and diagnostic algorithms.

THE MOST COMMON TICK-BORNE INFECTION IN NORTH AMERICA