User login

75-year-old man • recent history of hand-foot-mouth disease • discolored fingernails and toenails lifting from the proximal end • Dx?

THE CASE

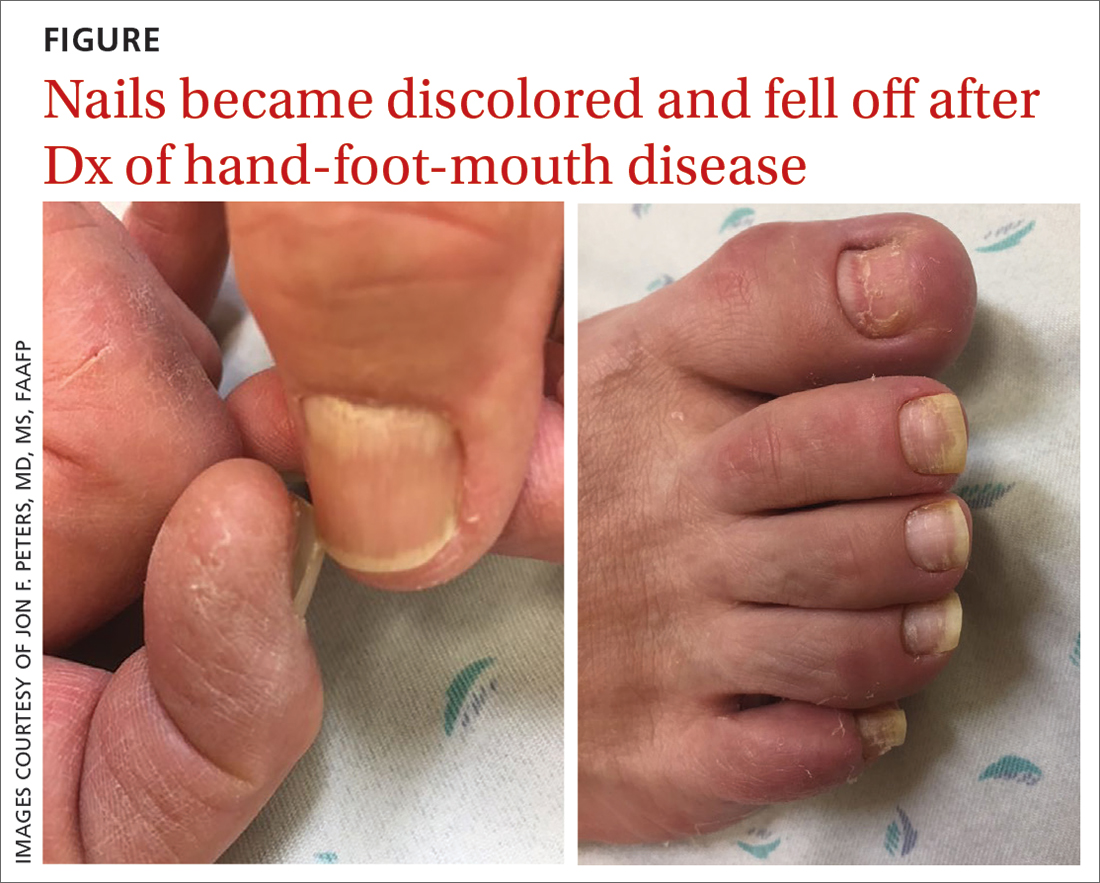

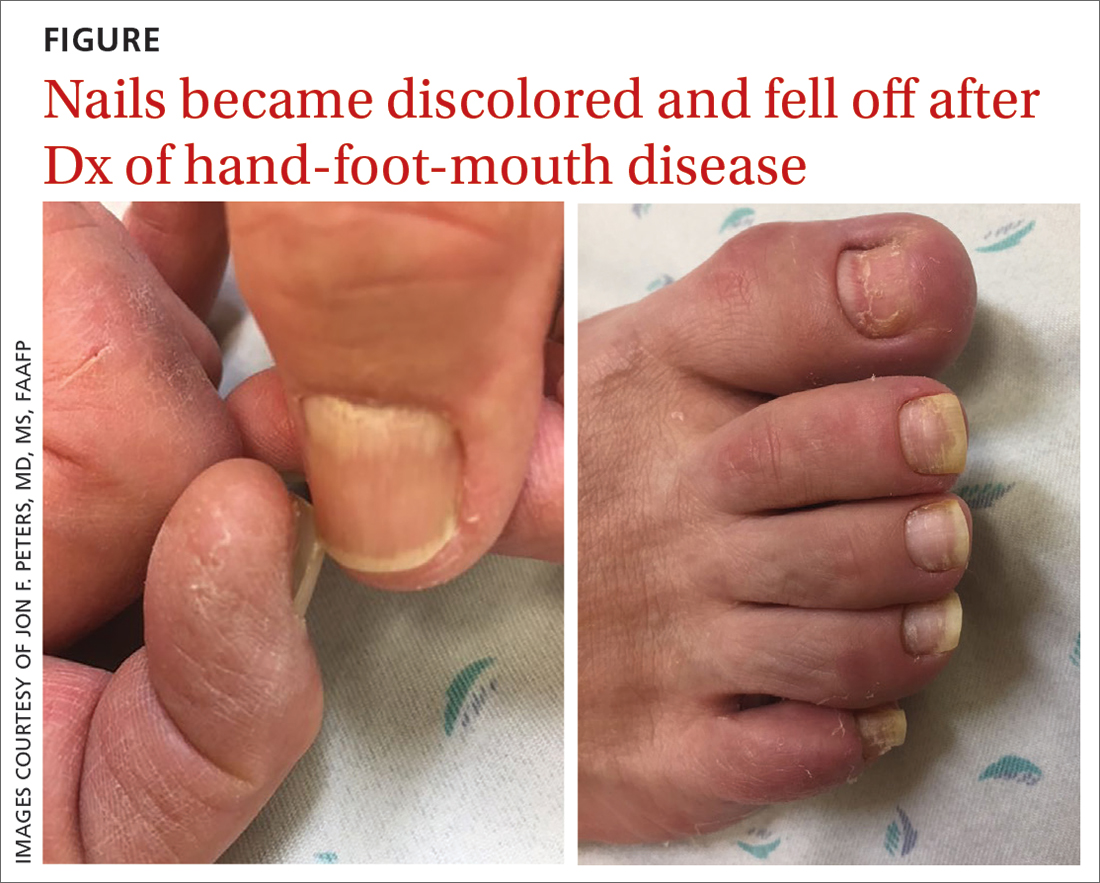

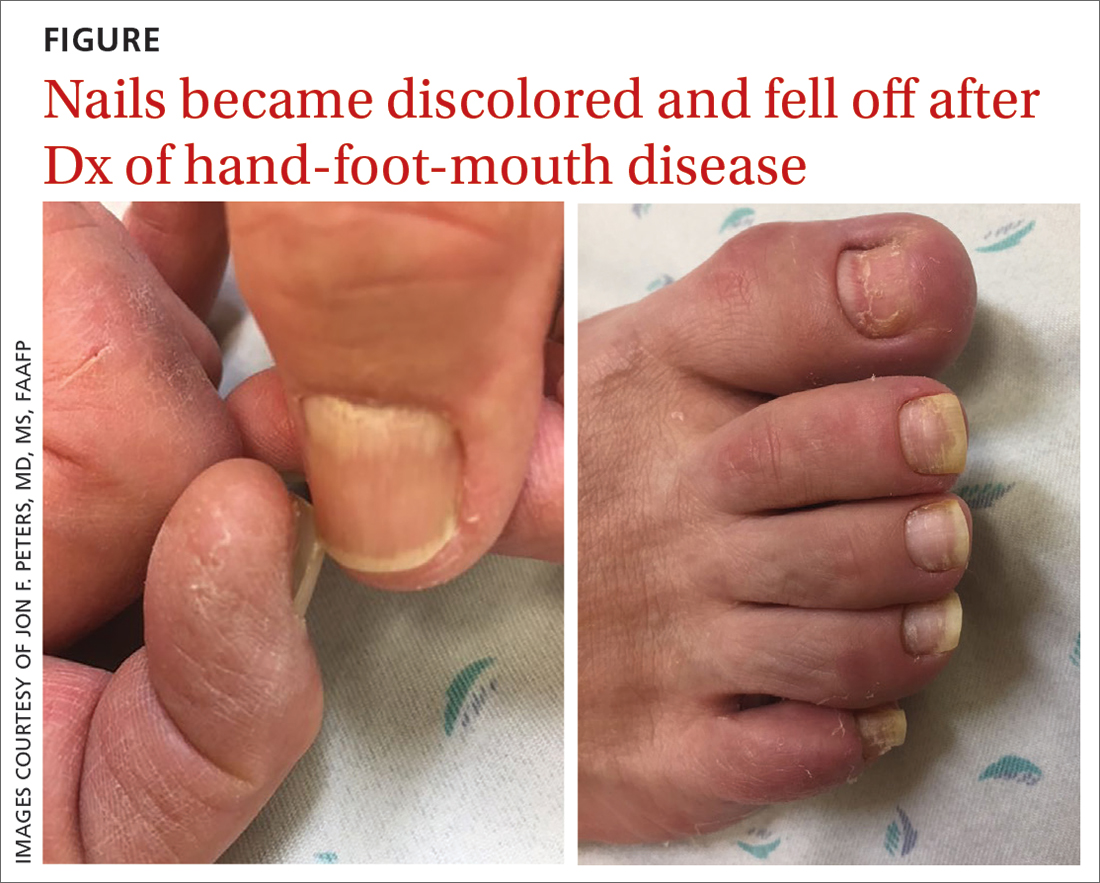

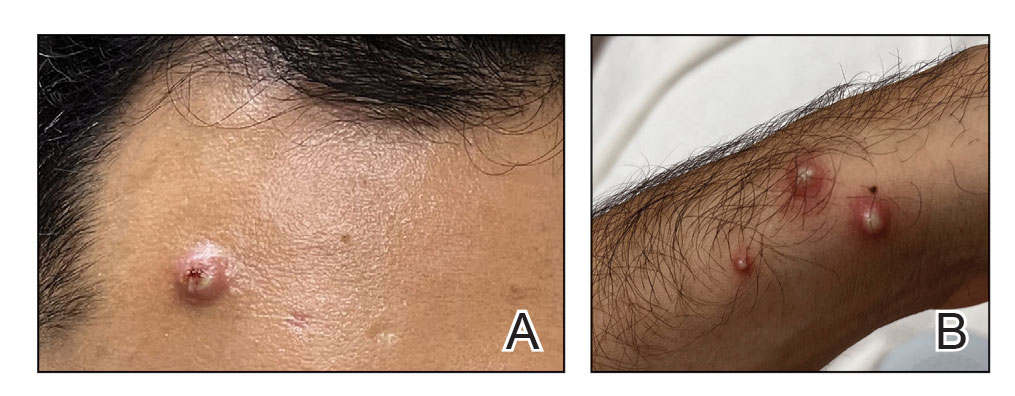

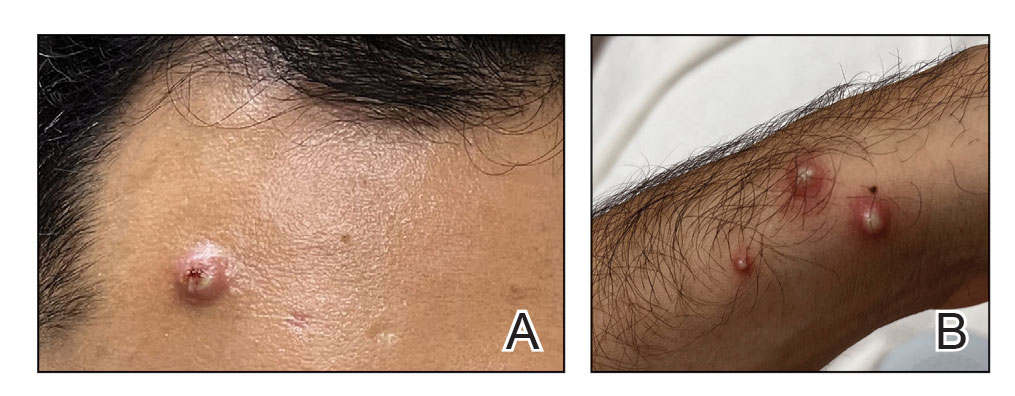

A 75-year-old man sought care from his primary care physician because his “fingernails and toenails [were] all falling off.” He did not feel ill and had no other complaints. His vital signs were unremarkable. He had no history of malignancies, chronic skin conditions, or systemic diseases. His fingernails and toenails were discolored and lifting from the proximal end of his nail beds (FIGURE). One of his great toenails had already fallen off, 1 thumb nail was minimally attached with the cuticle, and the rest of his nails were loose and in the process of separating from their nail beds. There was no nail pitting, rash, or joint swelling and tenderness.

The patient reported that while on vacation in Hawaii 3 weeks earlier, he had sought care at an urgent care clinic for a painless rash on his hands and the soles of his feet. At that time, he did not feel ill or have mouth ulcers, penile discharge, or arthralgia. There had been no recent changes to his prescription medications, which included finasteride, terazosin, omeprazole, and an albuterol inhaler. He denied taking over-the-counter medications or supplements.

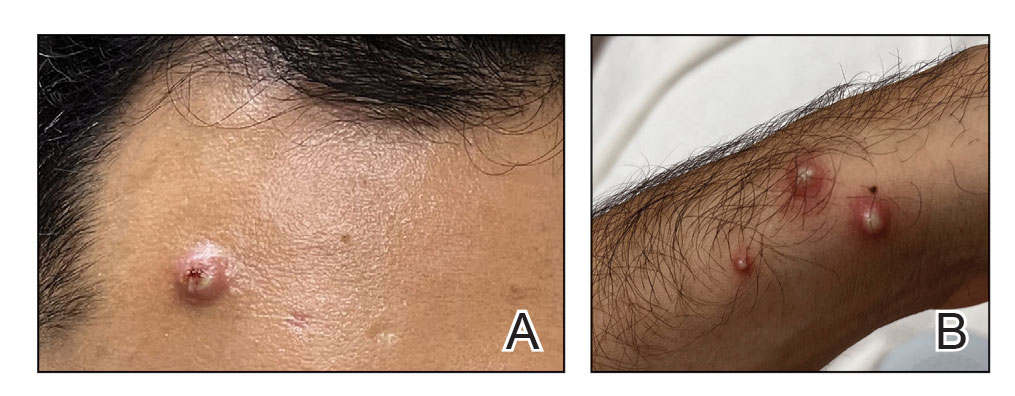

The physical exam at the urgent care had revealed multiple blotchy, dark, 0.5- to 1-cm nonpruritic lesions that were desquamating. No oral lesions were seen. He had been given a diagnosis of hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) and reassured that it would resolve on its own in about 10 days.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Several possible diagnoses for nail disorders came to mind with this patient, including onychomycosis, onychoschizia, onycholysis, and onychomadesis.

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nail that affects toenails more often than fingernails.1 The most common form is distal subungual onychomycosis, which begins distally and slowly migrates proximally through the nail matrix.1 Often onychomycosis affects only a few nails unless the patient is elderly or has comorbid conditions, and the nails rarely separate from the nail bed.

Onychoschizia involves lamellar splitting and peeling of the dorsal surface of the nail plate.2 Usually white discolorations appear on the distal edges of the nail.3 It is more common in women than in men and is often caused by nail dehydration from repeated excessive immersion in water with detergents or recurrent application of nail polish.2 However, the nails do not separate from the nail bed, and usually only the fingernails are involved.

Onycholysis is a nail attachment disorder in which the nail plate distally separates from the nail bed. Areas of separation will appear white or yellow. There are many etiologies for onycholysis, including trauma, psoriasis, fungal infection, and contact irritant reactions.3 It also can be caused by medications and thyroid disease.3,4

Continue to: Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis, sometimes considered a severe form of Beau’s line,5,6 is defined by the spontaneous separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. Although the nail will initially remain attached, proximal shedding will eventually occur.7 When several nails are involved, a systemic source—such as an acute infection, autoimmune disease, medication, malignancy (eg, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), Kawasaki disease, skin disorders (eg, pemphigus vulgaris or keratosis punctata et planters), or chemotherapy—may be the cause.6-8 If only a few nails are involved, it may be associated with trauma, and in rare cases, onychomadesis can be idiopathic.5,7

In this case, all signs pointed to onychomadesis. All of the patient’s nails were affected (discolored and lifting), his nail loss involved spontaneous proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix, and he had a recent previous infection: HFMD.

DISCUSSION

Onychomadesis is a rare nail-shedding disorder thought to be caused by the temporary arrest of the nail matrix.8 It is a potential late complication of infection, such as HFMD,9 and was first reported in children in Chicago in 2000.10 Since then, onychomadesis has been noted in children in many countries.8 Reports of onychomadesis following HFMD in adults are rare, but it may be underreported because HFMD is more common in children and symptoms are usually minor in adults.11

Molecular studies have associated onychomadesis with coxsackievirus (CV)A6 and CVA10.4 Other serotypes associated with onychomadesis include CVB1, CVB2, CVA5, CVA16, and enteroviruses 71 and 9.4 Most known outbreaks seem to be caused by CVA6.4

No treatment is needed for onychomadesis; physicians can reassure patients that normal nail growth will begin within 1 to 4 months. Because onychomadesis is rare, it does not have its own billing code, so one can use code L60.8 for “Other nail disorders.”12

Our patient was seen in the primary care clinic 3 months after his initial visit. At that time, his nails were no longer discolored and no other abnormalities were present. All of the nails on his fingers and toes were firmly attached and growing normally.

THE TAKEAWAY

The sudden asymptomatic loss of multiple fingernails and toenails—especially with proximal nail shedding—is a rare disorder known as onychomadesis. It can be caused by various etiologies and can be a late complication of HFMD or other viral infections. Onychomadesis should be considered when evaluating older patients, particularly when all of their nails are involved after a viral infection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jon F. Peters, MD, MS, FAAFP, 14486 SE Lyon Court, Happy Valley, OR 97086; [email protected]

1. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677-678.

2. Sparavigna A, Tenconi B, La Penna L. Efficacy and tolerability of a biomineral formulation for treatment of onychoschizia: a randomized trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019:12:355-362. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187305

3. Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.153002

4. Cleveland Clinic. Onycholysis. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22903-onycholysis

5. Chiu H-H, Liu M-T, Chung W-H, et al. The mechanism of onychomadesis (nail shedding) and Beau’s lines following hand-foot-mouth disease. Viruses. 2019;11:522. doi: 10.3390/v11060522

6. Suchonwanit P, Nitayavardhana S. Idiopathic sporadic onychomadesis of toenails. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;2016:6451327. doi: 10.1155/2016/6451327

7. Hardin J, Haber RM. Onychomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:592-596. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13339

8. Li D, Yang W, Xing X, et al. Onychomadesis and potential association with HFMD outbreak in a kindergarten in Hubei providence, China, 2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019:19:995. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4560-8

9. Chiu HH, Wu CS, Lan CE. Onychomadesis: a late complication of hand, foot, and mouth disease. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:243-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.01.034

10. Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01702.x

11. Scarfi F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Derm. 2014;53:1392-1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05774.x

12. ICD10Data.com. 2023 ICD-10-CM codes. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/codes

THE CASE

A 75-year-old man sought care from his primary care physician because his “fingernails and toenails [were] all falling off.” He did not feel ill and had no other complaints. His vital signs were unremarkable. He had no history of malignancies, chronic skin conditions, or systemic diseases. His fingernails and toenails were discolored and lifting from the proximal end of his nail beds (FIGURE). One of his great toenails had already fallen off, 1 thumb nail was minimally attached with the cuticle, and the rest of his nails were loose and in the process of separating from their nail beds. There was no nail pitting, rash, or joint swelling and tenderness.

The patient reported that while on vacation in Hawaii 3 weeks earlier, he had sought care at an urgent care clinic for a painless rash on his hands and the soles of his feet. At that time, he did not feel ill or have mouth ulcers, penile discharge, or arthralgia. There had been no recent changes to his prescription medications, which included finasteride, terazosin, omeprazole, and an albuterol inhaler. He denied taking over-the-counter medications or supplements.

The physical exam at the urgent care had revealed multiple blotchy, dark, 0.5- to 1-cm nonpruritic lesions that were desquamating. No oral lesions were seen. He had been given a diagnosis of hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) and reassured that it would resolve on its own in about 10 days.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Several possible diagnoses for nail disorders came to mind with this patient, including onychomycosis, onychoschizia, onycholysis, and onychomadesis.

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nail that affects toenails more often than fingernails.1 The most common form is distal subungual onychomycosis, which begins distally and slowly migrates proximally through the nail matrix.1 Often onychomycosis affects only a few nails unless the patient is elderly or has comorbid conditions, and the nails rarely separate from the nail bed.

Onychoschizia involves lamellar splitting and peeling of the dorsal surface of the nail plate.2 Usually white discolorations appear on the distal edges of the nail.3 It is more common in women than in men and is often caused by nail dehydration from repeated excessive immersion in water with detergents or recurrent application of nail polish.2 However, the nails do not separate from the nail bed, and usually only the fingernails are involved.

Onycholysis is a nail attachment disorder in which the nail plate distally separates from the nail bed. Areas of separation will appear white or yellow. There are many etiologies for onycholysis, including trauma, psoriasis, fungal infection, and contact irritant reactions.3 It also can be caused by medications and thyroid disease.3,4

Continue to: Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis, sometimes considered a severe form of Beau’s line,5,6 is defined by the spontaneous separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. Although the nail will initially remain attached, proximal shedding will eventually occur.7 When several nails are involved, a systemic source—such as an acute infection, autoimmune disease, medication, malignancy (eg, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), Kawasaki disease, skin disorders (eg, pemphigus vulgaris or keratosis punctata et planters), or chemotherapy—may be the cause.6-8 If only a few nails are involved, it may be associated with trauma, and in rare cases, onychomadesis can be idiopathic.5,7

In this case, all signs pointed to onychomadesis. All of the patient’s nails were affected (discolored and lifting), his nail loss involved spontaneous proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix, and he had a recent previous infection: HFMD.

DISCUSSION

Onychomadesis is a rare nail-shedding disorder thought to be caused by the temporary arrest of the nail matrix.8 It is a potential late complication of infection, such as HFMD,9 and was first reported in children in Chicago in 2000.10 Since then, onychomadesis has been noted in children in many countries.8 Reports of onychomadesis following HFMD in adults are rare, but it may be underreported because HFMD is more common in children and symptoms are usually minor in adults.11

Molecular studies have associated onychomadesis with coxsackievirus (CV)A6 and CVA10.4 Other serotypes associated with onychomadesis include CVB1, CVB2, CVA5, CVA16, and enteroviruses 71 and 9.4 Most known outbreaks seem to be caused by CVA6.4

No treatment is needed for onychomadesis; physicians can reassure patients that normal nail growth will begin within 1 to 4 months. Because onychomadesis is rare, it does not have its own billing code, so one can use code L60.8 for “Other nail disorders.”12

Our patient was seen in the primary care clinic 3 months after his initial visit. At that time, his nails were no longer discolored and no other abnormalities were present. All of the nails on his fingers and toes were firmly attached and growing normally.

THE TAKEAWAY

The sudden asymptomatic loss of multiple fingernails and toenails—especially with proximal nail shedding—is a rare disorder known as onychomadesis. It can be caused by various etiologies and can be a late complication of HFMD or other viral infections. Onychomadesis should be considered when evaluating older patients, particularly when all of their nails are involved after a viral infection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jon F. Peters, MD, MS, FAAFP, 14486 SE Lyon Court, Happy Valley, OR 97086; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 75-year-old man sought care from his primary care physician because his “fingernails and toenails [were] all falling off.” He did not feel ill and had no other complaints. His vital signs were unremarkable. He had no history of malignancies, chronic skin conditions, or systemic diseases. His fingernails and toenails were discolored and lifting from the proximal end of his nail beds (FIGURE). One of his great toenails had already fallen off, 1 thumb nail was minimally attached with the cuticle, and the rest of his nails were loose and in the process of separating from their nail beds. There was no nail pitting, rash, or joint swelling and tenderness.

The patient reported that while on vacation in Hawaii 3 weeks earlier, he had sought care at an urgent care clinic for a painless rash on his hands and the soles of his feet. At that time, he did not feel ill or have mouth ulcers, penile discharge, or arthralgia. There had been no recent changes to his prescription medications, which included finasteride, terazosin, omeprazole, and an albuterol inhaler. He denied taking over-the-counter medications or supplements.

The physical exam at the urgent care had revealed multiple blotchy, dark, 0.5- to 1-cm nonpruritic lesions that were desquamating. No oral lesions were seen. He had been given a diagnosis of hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) and reassured that it would resolve on its own in about 10 days.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Several possible diagnoses for nail disorders came to mind with this patient, including onychomycosis, onychoschizia, onycholysis, and onychomadesis.

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nail that affects toenails more often than fingernails.1 The most common form is distal subungual onychomycosis, which begins distally and slowly migrates proximally through the nail matrix.1 Often onychomycosis affects only a few nails unless the patient is elderly or has comorbid conditions, and the nails rarely separate from the nail bed.

Onychoschizia involves lamellar splitting and peeling of the dorsal surface of the nail plate.2 Usually white discolorations appear on the distal edges of the nail.3 It is more common in women than in men and is often caused by nail dehydration from repeated excessive immersion in water with detergents or recurrent application of nail polish.2 However, the nails do not separate from the nail bed, and usually only the fingernails are involved.

Onycholysis is a nail attachment disorder in which the nail plate distally separates from the nail bed. Areas of separation will appear white or yellow. There are many etiologies for onycholysis, including trauma, psoriasis, fungal infection, and contact irritant reactions.3 It also can be caused by medications and thyroid disease.3,4

Continue to: Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis, sometimes considered a severe form of Beau’s line,5,6 is defined by the spontaneous separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. Although the nail will initially remain attached, proximal shedding will eventually occur.7 When several nails are involved, a systemic source—such as an acute infection, autoimmune disease, medication, malignancy (eg, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), Kawasaki disease, skin disorders (eg, pemphigus vulgaris or keratosis punctata et planters), or chemotherapy—may be the cause.6-8 If only a few nails are involved, it may be associated with trauma, and in rare cases, onychomadesis can be idiopathic.5,7

In this case, all signs pointed to onychomadesis. All of the patient’s nails were affected (discolored and lifting), his nail loss involved spontaneous proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix, and he had a recent previous infection: HFMD.

DISCUSSION

Onychomadesis is a rare nail-shedding disorder thought to be caused by the temporary arrest of the nail matrix.8 It is a potential late complication of infection, such as HFMD,9 and was first reported in children in Chicago in 2000.10 Since then, onychomadesis has been noted in children in many countries.8 Reports of onychomadesis following HFMD in adults are rare, but it may be underreported because HFMD is more common in children and symptoms are usually minor in adults.11

Molecular studies have associated onychomadesis with coxsackievirus (CV)A6 and CVA10.4 Other serotypes associated with onychomadesis include CVB1, CVB2, CVA5, CVA16, and enteroviruses 71 and 9.4 Most known outbreaks seem to be caused by CVA6.4

No treatment is needed for onychomadesis; physicians can reassure patients that normal nail growth will begin within 1 to 4 months. Because onychomadesis is rare, it does not have its own billing code, so one can use code L60.8 for “Other nail disorders.”12

Our patient was seen in the primary care clinic 3 months after his initial visit. At that time, his nails were no longer discolored and no other abnormalities were present. All of the nails on his fingers and toes were firmly attached and growing normally.

THE TAKEAWAY

The sudden asymptomatic loss of multiple fingernails and toenails—especially with proximal nail shedding—is a rare disorder known as onychomadesis. It can be caused by various etiologies and can be a late complication of HFMD or other viral infections. Onychomadesis should be considered when evaluating older patients, particularly when all of their nails are involved after a viral infection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jon F. Peters, MD, MS, FAAFP, 14486 SE Lyon Court, Happy Valley, OR 97086; [email protected]

1. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677-678.

2. Sparavigna A, Tenconi B, La Penna L. Efficacy and tolerability of a biomineral formulation for treatment of onychoschizia: a randomized trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019:12:355-362. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187305

3. Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.153002

4. Cleveland Clinic. Onycholysis. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22903-onycholysis

5. Chiu H-H, Liu M-T, Chung W-H, et al. The mechanism of onychomadesis (nail shedding) and Beau’s lines following hand-foot-mouth disease. Viruses. 2019;11:522. doi: 10.3390/v11060522

6. Suchonwanit P, Nitayavardhana S. Idiopathic sporadic onychomadesis of toenails. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;2016:6451327. doi: 10.1155/2016/6451327

7. Hardin J, Haber RM. Onychomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:592-596. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13339

8. Li D, Yang W, Xing X, et al. Onychomadesis and potential association with HFMD outbreak in a kindergarten in Hubei providence, China, 2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019:19:995. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4560-8

9. Chiu HH, Wu CS, Lan CE. Onychomadesis: a late complication of hand, foot, and mouth disease. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:243-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.01.034

10. Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01702.x

11. Scarfi F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Derm. 2014;53:1392-1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05774.x

12. ICD10Data.com. 2023 ICD-10-CM codes. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/codes

1. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677-678.

2. Sparavigna A, Tenconi B, La Penna L. Efficacy and tolerability of a biomineral formulation for treatment of onychoschizia: a randomized trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019:12:355-362. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S187305

3. Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.153002

4. Cleveland Clinic. Onycholysis. Accessed March 1, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22903-onycholysis

5. Chiu H-H, Liu M-T, Chung W-H, et al. The mechanism of onychomadesis (nail shedding) and Beau’s lines following hand-foot-mouth disease. Viruses. 2019;11:522. doi: 10.3390/v11060522

6. Suchonwanit P, Nitayavardhana S. Idiopathic sporadic onychomadesis of toenails. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;2016:6451327. doi: 10.1155/2016/6451327

7. Hardin J, Haber RM. Onychomadesis: literature review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:592-596. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13339

8. Li D, Yang W, Xing X, et al. Onychomadesis and potential association with HFMD outbreak in a kindergarten in Hubei providence, China, 2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019:19:995. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4560-8

9. Chiu HH, Wu CS, Lan CE. Onychomadesis: a late complication of hand, foot, and mouth disease. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:243-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.01.034

10. Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01702.x

11. Scarfi F, Arunachalam M, Galeone M, et al. An uncommon onychomadesis in adults. Int J Derm. 2014;53:1392-1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05774.x

12. ICD10Data.com. 2023 ICD-10-CM codes. Accessed February 15, 2023. www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/codes

► Recent history of hand-foot-mouth disease

► Discolored fingernails and toenails lifting from the proximal end

Racial disparities not found in chronic hepatitis B treatment initiation

Researchers studying differences in treatment initiation for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) among a large, multiracial cohort in North America did not find evidence of disparities by race or socioeconomic status.

.

That gap suggests that treatment guidelines need to be simplified and that efforts to increase hepatitis B virus (HBV) awareness and train more clinicians are needed to achieve the World Health Organization’s goal of eliminating HBV by 2030, the researchers write.

The Hepatitis B Research Network study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

The prevalence of CHB in the United States is estimated at 2.4 million. It disproportionately affects persons of Asian or African descent, the investigators note. Their study examined whether treatment initiation and outcomes differ between African American and Black, Asian, and White participants, as well as between African American and Black participants born in North America and East or West Africa.

The research involved 1,550 adult patients: 1,157 Asian American, 193 African American or Black (39 born in the United States, 90 in East Africa, 53 in West Africa, and 11 elsewhere), 157 White, and 43 who identified as being of “other races.” All had CHB but were not receiving antiviral treatment at enrollment.

Participants came from 20 centers in the United States and one in Canada. They underwent clinical and laboratory assessments and could receive anti-HBV treatment after they enrolled. Enrollment was from Jan. 14, 2011, to Jan. 28, 2018. Participants were followed at 12 and 24 weeks and every 24 weeks thereafter in the longitudinal cohort study by Mandana Khalili, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

Information on patients’ country of birth, duration of U.S. or Canadian residency, educational level, employment, insurance, prior antiviral treatment, family history of HBV or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and mode of transmission were collected by research coordinators.

Treatment initiation

During the study period, slightly fewer than one-third (32.5%) of the participants initiated treatment. The incidences were 4.8 per 100 person-years in African American or Black participants, 9.9 per 100 person-years in Asian participants, 6.6 per 100 person-years in White participants, and 7.9 per 100 person-years in those of other races (P < .001).

A lower percentage of African American and Black participants (14%) met the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases treatment criteria, compared with Asian (22%) and White (27%) participants (P = .01).

When the researchers compared cumulative probability of initiating treatment by race for those who met criteria for treatment, they found no significant differences by race.

At 72 weeks, initiation probability was 0.45 for African American and Black patients and 0.51 for Asian and White patients (P = .68). Similarly, among African American and Black participants who met treatment criteria, there were no significant differences in cumulative probability of treatment by region of birth.

The cumulative percentage of treatment initiation for those who met guideline-based criteria was 62%.

“Among participants with a treatment indication, treatment rates did not differ significantly by race, despite marked differences in educational level, income, and type of health care insurance across the racial groups,” the researchers write. “Moreover, race was not an independent estimator of treatment initiation when adjusting for known factors associated with a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes, namely, HBV DNA, disease severity, sex, and age.”

Adverse liver outcomes (hepatic decompensation, HCC, liver transplant, and death) were rare and did not vary significantly by race, the researchers write.

One study limitation is that participants were linked to specialty liver clinics, so the findings may not be generalizable to patients who receive care in other settings, the authors note.

The results are “reassuring,” said senior author Anna S. Lok, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. However, she noted, study participants had already overcome barriers to receiving care at major academic centers.

“Once you get into the big academic liver centers, then maybe everything is equal, but in the real world, a lot of people don’t ever get to the big liver centers,” she said. The question becomes: “Are we serving only a portion of the patient population?”

Many factors drive the decision to undergo treatment, including the doctor’s opinion as to need and the patient’s desire to receive treatment, she said.

The study participants who were more likely to get treated were those with higher-level disease who had a stronger indication for treatment, Dr. Lok said.

Finding the disparities

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics show that Black people are 3.9 times more likely to have CHB and 2.5 times more likely to die from it than White people, notes H. Nina Kim, MD, with the department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, in an accompanying invited commentary.

“The fact that we have not observed racial disparities in treatment initiation does not mean none exist; it means we have to look harder to find them,” she writes.

“We need to examine whether our guidelines for HBV treatment are so complex that it becomes the purview of specialists, thereby restricting access and deepening inequities,” Dr. Kim adds. “We should look closely at retention in care, the step that precedes treatment, and stratify this outcome by race and ethnicity.”

Primary care physicians in some regions might find it difficult to manage patients who have hepatitis B because they see so few of them, Dr. Lok noted.

Dr. Khalili has received grants and consulting fees from Gilead Sciences Inc and grants from Intercept Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Dr. Lok has received grants from Target and consultant fees from Abbott, Ambys, Arbutus, Chroma, Clear B, Enanta, Enochian, GNI, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Virion outside the submitted work. Coauthors have received grants, consulting fees, or personal fees from Bayer, Boston Scientific, Exact Sciences, Fujifilm Medical Sciences, Gilead Sciences, Glycotest, Redhill Biopharma, Target RWE, MedEd Design, Pontifax, Global Life, the Lynx Group, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Novartis Venture Fund, Grail, QED Therapeutics, Genentech, Hepion Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Abbott, AbbVie, and Pfizer. Dr. Kim has received grants from Gilead Sciences (paid to her institution) outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers studying differences in treatment initiation for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) among a large, multiracial cohort in North America did not find evidence of disparities by race or socioeconomic status.

.

That gap suggests that treatment guidelines need to be simplified and that efforts to increase hepatitis B virus (HBV) awareness and train more clinicians are needed to achieve the World Health Organization’s goal of eliminating HBV by 2030, the researchers write.

The Hepatitis B Research Network study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

The prevalence of CHB in the United States is estimated at 2.4 million. It disproportionately affects persons of Asian or African descent, the investigators note. Their study examined whether treatment initiation and outcomes differ between African American and Black, Asian, and White participants, as well as between African American and Black participants born in North America and East or West Africa.

The research involved 1,550 adult patients: 1,157 Asian American, 193 African American or Black (39 born in the United States, 90 in East Africa, 53 in West Africa, and 11 elsewhere), 157 White, and 43 who identified as being of “other races.” All had CHB but were not receiving antiviral treatment at enrollment.

Participants came from 20 centers in the United States and one in Canada. They underwent clinical and laboratory assessments and could receive anti-HBV treatment after they enrolled. Enrollment was from Jan. 14, 2011, to Jan. 28, 2018. Participants were followed at 12 and 24 weeks and every 24 weeks thereafter in the longitudinal cohort study by Mandana Khalili, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

Information on patients’ country of birth, duration of U.S. or Canadian residency, educational level, employment, insurance, prior antiviral treatment, family history of HBV or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and mode of transmission were collected by research coordinators.

Treatment initiation

During the study period, slightly fewer than one-third (32.5%) of the participants initiated treatment. The incidences were 4.8 per 100 person-years in African American or Black participants, 9.9 per 100 person-years in Asian participants, 6.6 per 100 person-years in White participants, and 7.9 per 100 person-years in those of other races (P < .001).

A lower percentage of African American and Black participants (14%) met the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases treatment criteria, compared with Asian (22%) and White (27%) participants (P = .01).

When the researchers compared cumulative probability of initiating treatment by race for those who met criteria for treatment, they found no significant differences by race.

At 72 weeks, initiation probability was 0.45 for African American and Black patients and 0.51 for Asian and White patients (P = .68). Similarly, among African American and Black participants who met treatment criteria, there were no significant differences in cumulative probability of treatment by region of birth.

The cumulative percentage of treatment initiation for those who met guideline-based criteria was 62%.

“Among participants with a treatment indication, treatment rates did not differ significantly by race, despite marked differences in educational level, income, and type of health care insurance across the racial groups,” the researchers write. “Moreover, race was not an independent estimator of treatment initiation when adjusting for known factors associated with a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes, namely, HBV DNA, disease severity, sex, and age.”

Adverse liver outcomes (hepatic decompensation, HCC, liver transplant, and death) were rare and did not vary significantly by race, the researchers write.

One study limitation is that participants were linked to specialty liver clinics, so the findings may not be generalizable to patients who receive care in other settings, the authors note.

The results are “reassuring,” said senior author Anna S. Lok, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. However, she noted, study participants had already overcome barriers to receiving care at major academic centers.

“Once you get into the big academic liver centers, then maybe everything is equal, but in the real world, a lot of people don’t ever get to the big liver centers,” she said. The question becomes: “Are we serving only a portion of the patient population?”

Many factors drive the decision to undergo treatment, including the doctor’s opinion as to need and the patient’s desire to receive treatment, she said.

The study participants who were more likely to get treated were those with higher-level disease who had a stronger indication for treatment, Dr. Lok said.

Finding the disparities

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics show that Black people are 3.9 times more likely to have CHB and 2.5 times more likely to die from it than White people, notes H. Nina Kim, MD, with the department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, in an accompanying invited commentary.

“The fact that we have not observed racial disparities in treatment initiation does not mean none exist; it means we have to look harder to find them,” she writes.

“We need to examine whether our guidelines for HBV treatment are so complex that it becomes the purview of specialists, thereby restricting access and deepening inequities,” Dr. Kim adds. “We should look closely at retention in care, the step that precedes treatment, and stratify this outcome by race and ethnicity.”

Primary care physicians in some regions might find it difficult to manage patients who have hepatitis B because they see so few of them, Dr. Lok noted.

Dr. Khalili has received grants and consulting fees from Gilead Sciences Inc and grants from Intercept Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Dr. Lok has received grants from Target and consultant fees from Abbott, Ambys, Arbutus, Chroma, Clear B, Enanta, Enochian, GNI, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Virion outside the submitted work. Coauthors have received grants, consulting fees, or personal fees from Bayer, Boston Scientific, Exact Sciences, Fujifilm Medical Sciences, Gilead Sciences, Glycotest, Redhill Biopharma, Target RWE, MedEd Design, Pontifax, Global Life, the Lynx Group, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Novartis Venture Fund, Grail, QED Therapeutics, Genentech, Hepion Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Abbott, AbbVie, and Pfizer. Dr. Kim has received grants from Gilead Sciences (paid to her institution) outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers studying differences in treatment initiation for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) among a large, multiracial cohort in North America did not find evidence of disparities by race or socioeconomic status.

.

That gap suggests that treatment guidelines need to be simplified and that efforts to increase hepatitis B virus (HBV) awareness and train more clinicians are needed to achieve the World Health Organization’s goal of eliminating HBV by 2030, the researchers write.

The Hepatitis B Research Network study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

The prevalence of CHB in the United States is estimated at 2.4 million. It disproportionately affects persons of Asian or African descent, the investigators note. Their study examined whether treatment initiation and outcomes differ between African American and Black, Asian, and White participants, as well as between African American and Black participants born in North America and East or West Africa.

The research involved 1,550 adult patients: 1,157 Asian American, 193 African American or Black (39 born in the United States, 90 in East Africa, 53 in West Africa, and 11 elsewhere), 157 White, and 43 who identified as being of “other races.” All had CHB but were not receiving antiviral treatment at enrollment.

Participants came from 20 centers in the United States and one in Canada. They underwent clinical and laboratory assessments and could receive anti-HBV treatment after they enrolled. Enrollment was from Jan. 14, 2011, to Jan. 28, 2018. Participants were followed at 12 and 24 weeks and every 24 weeks thereafter in the longitudinal cohort study by Mandana Khalili, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

Information on patients’ country of birth, duration of U.S. or Canadian residency, educational level, employment, insurance, prior antiviral treatment, family history of HBV or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and mode of transmission were collected by research coordinators.

Treatment initiation

During the study period, slightly fewer than one-third (32.5%) of the participants initiated treatment. The incidences were 4.8 per 100 person-years in African American or Black participants, 9.9 per 100 person-years in Asian participants, 6.6 per 100 person-years in White participants, and 7.9 per 100 person-years in those of other races (P < .001).

A lower percentage of African American and Black participants (14%) met the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases treatment criteria, compared with Asian (22%) and White (27%) participants (P = .01).

When the researchers compared cumulative probability of initiating treatment by race for those who met criteria for treatment, they found no significant differences by race.

At 72 weeks, initiation probability was 0.45 for African American and Black patients and 0.51 for Asian and White patients (P = .68). Similarly, among African American and Black participants who met treatment criteria, there were no significant differences in cumulative probability of treatment by region of birth.

The cumulative percentage of treatment initiation for those who met guideline-based criteria was 62%.

“Among participants with a treatment indication, treatment rates did not differ significantly by race, despite marked differences in educational level, income, and type of health care insurance across the racial groups,” the researchers write. “Moreover, race was not an independent estimator of treatment initiation when adjusting for known factors associated with a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes, namely, HBV DNA, disease severity, sex, and age.”

Adverse liver outcomes (hepatic decompensation, HCC, liver transplant, and death) were rare and did not vary significantly by race, the researchers write.

One study limitation is that participants were linked to specialty liver clinics, so the findings may not be generalizable to patients who receive care in other settings, the authors note.

The results are “reassuring,” said senior author Anna S. Lok, MD, division of gastroenterology and hepatology at University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. However, she noted, study participants had already overcome barriers to receiving care at major academic centers.

“Once you get into the big academic liver centers, then maybe everything is equal, but in the real world, a lot of people don’t ever get to the big liver centers,” she said. The question becomes: “Are we serving only a portion of the patient population?”

Many factors drive the decision to undergo treatment, including the doctor’s opinion as to need and the patient’s desire to receive treatment, she said.

The study participants who were more likely to get treated were those with higher-level disease who had a stronger indication for treatment, Dr. Lok said.

Finding the disparities

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics show that Black people are 3.9 times more likely to have CHB and 2.5 times more likely to die from it than White people, notes H. Nina Kim, MD, with the department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, in an accompanying invited commentary.

“The fact that we have not observed racial disparities in treatment initiation does not mean none exist; it means we have to look harder to find them,” she writes.

“We need to examine whether our guidelines for HBV treatment are so complex that it becomes the purview of specialists, thereby restricting access and deepening inequities,” Dr. Kim adds. “We should look closely at retention in care, the step that precedes treatment, and stratify this outcome by race and ethnicity.”

Primary care physicians in some regions might find it difficult to manage patients who have hepatitis B because they see so few of them, Dr. Lok noted.

Dr. Khalili has received grants and consulting fees from Gilead Sciences Inc and grants from Intercept Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Dr. Lok has received grants from Target and consultant fees from Abbott, Ambys, Arbutus, Chroma, Clear B, Enanta, Enochian, GNI, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, and Virion outside the submitted work. Coauthors have received grants, consulting fees, or personal fees from Bayer, Boston Scientific, Exact Sciences, Fujifilm Medical Sciences, Gilead Sciences, Glycotest, Redhill Biopharma, Target RWE, MedEd Design, Pontifax, Global Life, the Lynx Group, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Novartis Venture Fund, Grail, QED Therapeutics, Genentech, Hepion Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Abbott, AbbVie, and Pfizer. Dr. Kim has received grants from Gilead Sciences (paid to her institution) outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

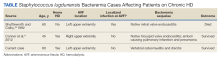

High-Grade Staphylococcus lugdunensis Bacteremia in a Patient on Home Hemodialysis

Staphylococcus lugdunensis (S lugdunensis) is a species of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) and a constituent of human skin flora. Unlike other strains of CoNS, however, S lugdunensis has gained notoriety for virulence that resembles Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus). S lugdunensis is now recognized as an important nosocomial pathogen and cause of prosthetic device infections, including vascular catheter infections. We present a case of persistent S lugdunensis bacteremia occurring in a patient on hemodialysis (HD) without any implanted prosthetic materials.

Case Presentation

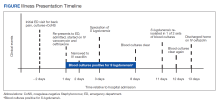

A 60-year-old man with a history of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and end-stage renal disease on home HD via arteriovenous fistula (AVF) presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of subacute progressive low back pain. His symptoms began abruptly 2 weeks prior to presentation without any identifiable trigger or trauma. His pain localized to the lower thoracic spine, radiating anteriorly into his abdomen. He reported tactile fever for several days before presentation but no chills, night sweats, paresthesia, weakness, or bowel/bladder incontinence. He had no recent surgeries, implanted hardware, or invasive procedures involving the spine. HD was performed 5 times a week at home with a family member cannulating his AVF via buttonhole technique. He initially sought evaluation in a community hospital several days prior, where he underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine. He was discharged from the community ED with oral opioids prior to the MRI results. He presented to West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WLAVAMC) ED when MRI results came back indicating abnormalities and he reported recalcitrant pain.

On arrival at WLAVAMC, the patient was afebrile with a heart rate of 107 bpm and blood pressure of 152/97 mm Hg. The remainder of his vital signs were normal. The physical examination revealed midline tenderness on palpation of the distal thoracic and proximal lumbar spine. Muscle strength was 4 of 5 in the bilateral hip flexors, though this was limited by pain. The remainder of his neurologic examination was nonfocal. The cardiac examination was unremarkable with no murmurs auscultated. His left upper extremity AVF had an audible bruit and palpable thrill. The skin examination was notable for acanthosis nigricans but no areas of skin erythema or induration and no obvious stigmata of infective endocarditis.

The initial laboratory workup was remarkable for a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10.0 × 103/µL with left shift, blood urea nitrogen level of 59 mg/dL, and creatinine level of 9.3 mg/dL. The patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 45 mm/h (reference range, ≤ 20 mm/h) and C-reactive protein level was > 8.0 mg/L (reference range, ≤ 0.74 mg/L). Two months prior the hemoglobin A1c had been recorded at 9.9%.

Given his intractable low back pain and elevated inflammatory markers, the patient underwent an MRI of the thoracic and lumbar spine with contrast while in the ED. This MRI revealed abnormal marrow edema in the T11-T12 vertebrae with abnormal fluid signal in the T11-T12 disc space. Subjacent paravertebral edema also was noted. There was no well-defined fluid collection or abnormal signal in the spinal cord. Taken together, these findings were concerning for T11-T12 discitis with osteomyelitis.

Two sets of blood cultures were obtained, and empiric IV vancomycin and ceftriaxone were started. Interventional radiology was consulted for consideration of vertebral biopsy but deferred while awaiting blood culture data. Neurosurgery also was consulted and recommended nonoperative management given his nonfocal neurologic examination and imaging without evidence of abscess. Both sets of blood cultures collected on admission later grew methicillin-sensitive S lugdunensis, a species of CoNS. A transthoracic and later transesophageal echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations. The patient’s antibiotic regimen was narrowed to IV oxacillin based on susceptibility data. It was later discovered that both blood cultures obtained during his outside ED encounter were also growing S lugdunensis.

The patient’s S lugdunensis bacteremia persisted for the first 8 days of his admission despite appropriate dosing of oxacillin. During this time, the patient remained afebrile with stable vital signs and a normal WBC count. Positron emission tomography was obtained to evaluate for potential sources of his persistent bacteremia. Aside from tracer uptake in the T11-T12 vertebral bodies and intervertebral disc space, no other areas showed suspicious uptake. Neurosurgery reevaluated the patient and again recommended nonoperative management. Blood cultures cleared and based on recommendations from an infectious disease specialist, the patient was transitioned to IV cefazolin dosed 3 times weekly after HD, which was transitioned to an outpatient dialysis center. The patient continued taking cefazolin for 6 weeks with subsequent improvement in back pain and normalization of inflammatory markers at outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

CoNS are a major contributor to human skin flora, a common contaminant of blood cultures, and an important cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections.1,2 These species have a predilection for forming biofilms, making CoNS a major cause of prosthetic device infections.3 S lugdunensis is a CoNS species that was first described in 1988.4 In addition to foreign body–related infections, S lugdunensis has been implicated in bone/joint infections, native valve endocarditis, toxic shock syndrome, and brain abscesses.5-8 Infections due to S lugdunensis are notorious for their aggressive and fulminant courses. With its increased virulence that is atypical of other CoNS, S lugdunensis has understandably been likened more to S aureus.

Prior cases have been reported of S lugdunensis bacteremia in patients using HD. However, the suspected source of bacteremia in these cases has generally been central venous catheters.9-12

Notably, our patient’s AVF was accessed using the buttonhole technique for his home HD sessions, which involves cannulating the same site along the fistula until an epithelialized track has formed from scar tissue. At later HD sessions, duller needles can then be used to cannulate this same track. In contrast, the rope-ladder technique involves cannulating a different site along the fistula until the entire length of the fistula has been used. Patients report higher levels of satisfaction with the buttonhole technique, citing decreased pain, decreased oozing, and the perception of easier cannulation by HD nurses.14 However, the buttonhole technique also appears to confer a higher risk of vascular access-related bloodstream infection when compared with the rope-ladder technique.13,15,16

The buttonhole technique is hypothesized to increase infection risk due to the repeated use of the same site for needle entry. Skin flora, including CoNS, may colonize the scab that forms after dialysis access. If proper sterilization techniques are not rigorously followed, the bacteria colonizing the scab and adjacent skin may be introduced into a patient’s bloodstream during needle puncture. Loss of skin integrity due to frequent cannulation of the same site may also contribute to this increased infection risk. It is relevant to recall that our patient received HD 5 times weekly using the buttonhole technique. The use of the buttonhole technique, frequency of his HD sessions, unclear sterilization methods, and immune dysfunction related to his uncontrolled T2DM and renal disease all likely contributed to our patient’s bacteremia.

Using topical mupirocin for prophylaxis at the intended buttonhole puncture site has shown promising results in decreasing rates of S aureus bacteremia.17 It is unclear whether this intervention also would be effective against S lugdunensis. Increasing rates of mupirocin resistance have been reported among S lugdunensis isolates in dialysis settings, but further research in this area is warranted.18

There are no established treatment guidelines for S lugdunensis infections. In vitro studies suggest that S lugdunensis is susceptible to a wide variety of antibiotics. The mecA gene is a major determinant of methicillin resistance that is commonly observed among CoNS but is uncommonly seen with S lugdunensis.5 In a study by Tan and colleagues of 106 S lugdunensis isolates, they found that only 5 (4.7%) were mecA positive.19

Vancomycin is generally reasonable for empiric antibiotic coverage of staphylococci while speciation is pending. However, if S lugdunensis is isolated, its favorable susceptibility pattern typically allows for de-escalation to an antistaphylococcal β-lactam, such as oxacillin or nafcillin. In cases of bloodstream infections caused by methicillin-sensitive S aureus, treatment with a β-lactam has demonstrated superiority over vancomycin due to the lower rates of treatment failure and mortality with β-lactams.20,21 It is unknown whether β-lactams is superior for treating bacteremia with methicillin-sensitive S lugdunensis.

Our patient’s isolate of S lugdunensis was pansensitive to all antibiotics tested, including penicillin. These susceptibility data were used to guide the de-escalation of his empiric vancomycin and ceftriaxone to oxacillin on hospital day 1.

Due to their virulence, bloodstream infections caused by S aureus and S lugdunensis often require more than timely antimicrobial treatment to ensure eradication. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist to manage patients with S aureus bacteremia has been proven to reduce mortality.25 A similar mortality benefit is seen when infectious disease specialists are consulted for S lugdunensis bacteremia.26 This mortality benefit is likely explained by S lugdunensis’ propensity to cause aggressive, metastatic infections. In such cases, infectious disease consultants may recommend additional imaging (eg, transthoracic echocardiogram) to evaluate for occult sources of infection, advocate for appropriate source control, and guide the selection of an appropriate antibiotic course to ensure resolution of the bacteremia.

Conclusions

S lugdunensis is an increasingly recognized cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections. Given the commonalities in virulence that S lugdunensis shares with S aureus, treatment of bacteremia caused by either species should follow similar management principles: prompt initiation of IV antistaphylococcal therapy, a thorough evaluation for the source(s) of bacteremia as well as metastatic complications, and consultation with an infectious disease specialist. This case report also highlights the importance of considering a patient’s AVF as a potential source for infection even in the absence of localized signs of infection. The buttonhole method of AVF cannulation was thought to be a major contributor to the development and persistence of our patient’s bacteremia. This risk should be discussed with patients using a shared decision-making approach when developing a dialysis treatment plan.

1. Huebner J, Goldmann DA. Coagulase-negative staphylococci: role as pathogens. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50(1):223-236. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.223

2. Beekmann SE, Diekema DJ, Doern GV. Determining the clinical significance of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from blood cultures. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(6):559-566. doi:10.1086/502584

3. Arrecubieta C, Toba FA, von Bayern M, et al. SdrF, a Staphylococcus epidermidis surface protein, contributes to the initiation of ventricular assist device driveline–related infections. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(5):e1000411. doi.10.1371/journal.ppat.1000411

4. Freney J, Brun Y, Bes M, et al. Staphylococcus lugdunensis sp. nov. and Staphylococcus schleiferi sp. nov., two species from human clinical specimens. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38(2):168-172. doi:10.1099/00207713-38-2-168

5. Frank KL, del Pozo JL, Patel R. From clinical microbiology to infection pathogenesis: how daring to be different works for Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(1):111-133. doi:10.1128/CMR.00036-07

6. Anguera I, Del Río A, Miró JM; Hospital Clinic Endocarditis Study Group. Staphylococcus lugdunensis infective endocarditis: description of 10 cases and analysis of native valve, prosthetic valve, and pacemaker lead endocarditis clinical profiles. Heart. 2005;91(2):e10. doi:10.1136/hrt.2004.040659

7. Pareja J, Gupta K, Koziel H. The toxic shock syndrome and Staphylococcus lugdunensis bacteremia. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(7):603-604. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-128-7-199804010-00029

8. Woznowski M, Quack I, Bölke E, et al. Fulminant Staphylococcus lugdunensis septicaemia following a pelvic varicella-zoster virus infection in an immune-deficient patient: a case report. Eur J Med Res. 201;15(9):410-414. doi:10.1186/2047-783x-15-9-410

9. Mallappallil M, Salifu M, Woredekal Y, et al. Staphylococcus lugdunensis bacteremia in hemodialysis patients. Int J Microbiol Res. 2012;4(2):178-181. doi:10.9735/0975-5276.4.2.178-181

10. Shuttleworth R, Colby W. Staphylococcus lugdunensis endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(8):5. doi:10.1128/jcm.30.8.1948-1952.1992

11. Conner RC, Byrnes TJ, Clough LA, Myers JP. Staphylococcus lugdunensis tricuspid valve endocarditis associated with home hemodialysis therapy: report of a case and review of the literature. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2012;20(3):182-183. doi:1097/IPC.0b013e318245d4f1

12. Kamaraju S, Nelson K, Williams D, Ayenew W, Modi K. Staphylococcus lugdunensis pulmonary valve endocarditis in a patient on chronic hemodialysis. Am J Nephrol. 1999;19(5):605-608. doi:1097/IPC.0b013e318245d4f1

13. Lok C, Sontrop J, Faratro R, Chan C, Zimmerman DL. Frequent hemodialysis fistula infectious complications. Nephron Extra. 2014;4(3):159-167. doi:10.1159/000366477

14. Hashmi A, Cheema MQ, Moss AH. Hemodialysis patients’ experience with and attitudes toward the buttonhole technique for arteriovenous fistula cannulation. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74(5):346-350. doi:10.5414/cnp74346

15. Lyman M, Nguyen DB, Shugart A, Gruhler H, Lines C, Patel PR. Risk of vascular access infection associated with buttonhole cannulation of fistulas: data from the National Healthcare Safety Network. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76(1):82-89. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.11.006

16. MacRae JM, Ahmed SB, Atkar R, Hemmelgarn BR. A randomized trial comparing buttonhole with rope ladder needling in conventional hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1632-1638. doi:10.2215/CJN.02730312

17. Nesrallah GE, Cuerden M, Wong JHS, Pierratos A. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and buttonhole cannulation: long-term safety and efficacy of mupirocin prophylaxis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(6):1047-1053. doi:10.2215/CJN.00280110

18. Ho PL, Liu MCJ, Chow KH, et al. Emergence of ileS2 -carrying, multidrug-resistant plasmids in Staphylococcus lugdunensis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(10):6411-6414. doi:10.1128/AAC.00948-16

19. Tan TY, Ng SY, He J. Microbiological characteristics, presumptive identification, and antibiotic susceptibilities of Staphylococcus lugdunensis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(7):2393-2395. doi:10.1128/JCM.00740-08

20. Chang FY, Peacock JE, Musher DM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: recurrence and the impact of antibiotic treatment in a prospective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82(5):333-339. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000091184.93122.09

21. Shurland S, Zhan M, Bradham DD, Roghmann MC. Comparison of mortality risk associated with bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(3):273-279. doi:10.1086/512627

22. Levine DP, Fromm BS, Reddy BR. Slow response to vancomycin or vancomycin plus rifampin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(9):674. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-115-9-674

23. Fowler VG, Karchmer AW, Tally FP, et al; S. aureus Endocarditis and Bacteremia Study Group. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):653-665 . doi:10.1056/NEJMoa053783

24. Duhon B, Dallas S, Velasquez ST, Hand E. Staphylococcus lugdunensis bacteremia and endocarditis treated with cefazolin and rifampin. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(13):1114-1118. doi:10.2146/ajhp140498

25. Lahey T, Shah R, Gittzus J, Schwartzman J, Kirkland K. Infectious diseases consultation lowers mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(5):263-267. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3181b8fccb

26. Forsblom E, Högnäs E, Syrjänen J, Järvinen A. Infectious diseases specialist consultation in Staphylococcus lugdunensis bacteremia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(10):e0258511. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0258511

Staphylococcus lugdunensis (S lugdunensis) is a species of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) and a constituent of human skin flora. Unlike other strains of CoNS, however, S lugdunensis has gained notoriety for virulence that resembles Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus). S lugdunensis is now recognized as an important nosocomial pathogen and cause of prosthetic device infections, including vascular catheter infections. We present a case of persistent S lugdunensis bacteremia occurring in a patient on hemodialysis (HD) without any implanted prosthetic materials.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old man with a history of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and end-stage renal disease on home HD via arteriovenous fistula (AVF) presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of subacute progressive low back pain. His symptoms began abruptly 2 weeks prior to presentation without any identifiable trigger or trauma. His pain localized to the lower thoracic spine, radiating anteriorly into his abdomen. He reported tactile fever for several days before presentation but no chills, night sweats, paresthesia, weakness, or bowel/bladder incontinence. He had no recent surgeries, implanted hardware, or invasive procedures involving the spine. HD was performed 5 times a week at home with a family member cannulating his AVF via buttonhole technique. He initially sought evaluation in a community hospital several days prior, where he underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine. He was discharged from the community ED with oral opioids prior to the MRI results. He presented to West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WLAVAMC) ED when MRI results came back indicating abnormalities and he reported recalcitrant pain.

On arrival at WLAVAMC, the patient was afebrile with a heart rate of 107 bpm and blood pressure of 152/97 mm Hg. The remainder of his vital signs were normal. The physical examination revealed midline tenderness on palpation of the distal thoracic and proximal lumbar spine. Muscle strength was 4 of 5 in the bilateral hip flexors, though this was limited by pain. The remainder of his neurologic examination was nonfocal. The cardiac examination was unremarkable with no murmurs auscultated. His left upper extremity AVF had an audible bruit and palpable thrill. The skin examination was notable for acanthosis nigricans but no areas of skin erythema or induration and no obvious stigmata of infective endocarditis.

The initial laboratory workup was remarkable for a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10.0 × 103/µL with left shift, blood urea nitrogen level of 59 mg/dL, and creatinine level of 9.3 mg/dL. The patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 45 mm/h (reference range, ≤ 20 mm/h) and C-reactive protein level was > 8.0 mg/L (reference range, ≤ 0.74 mg/L). Two months prior the hemoglobin A1c had been recorded at 9.9%.

Given his intractable low back pain and elevated inflammatory markers, the patient underwent an MRI of the thoracic and lumbar spine with contrast while in the ED. This MRI revealed abnormal marrow edema in the T11-T12 vertebrae with abnormal fluid signal in the T11-T12 disc space. Subjacent paravertebral edema also was noted. There was no well-defined fluid collection or abnormal signal in the spinal cord. Taken together, these findings were concerning for T11-T12 discitis with osteomyelitis.

Two sets of blood cultures were obtained, and empiric IV vancomycin and ceftriaxone were started. Interventional radiology was consulted for consideration of vertebral biopsy but deferred while awaiting blood culture data. Neurosurgery also was consulted and recommended nonoperative management given his nonfocal neurologic examination and imaging without evidence of abscess. Both sets of blood cultures collected on admission later grew methicillin-sensitive S lugdunensis, a species of CoNS. A transthoracic and later transesophageal echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations. The patient’s antibiotic regimen was narrowed to IV oxacillin based on susceptibility data. It was later discovered that both blood cultures obtained during his outside ED encounter were also growing S lugdunensis.

The patient’s S lugdunensis bacteremia persisted for the first 8 days of his admission despite appropriate dosing of oxacillin. During this time, the patient remained afebrile with stable vital signs and a normal WBC count. Positron emission tomography was obtained to evaluate for potential sources of his persistent bacteremia. Aside from tracer uptake in the T11-T12 vertebral bodies and intervertebral disc space, no other areas showed suspicious uptake. Neurosurgery reevaluated the patient and again recommended nonoperative management. Blood cultures cleared and based on recommendations from an infectious disease specialist, the patient was transitioned to IV cefazolin dosed 3 times weekly after HD, which was transitioned to an outpatient dialysis center. The patient continued taking cefazolin for 6 weeks with subsequent improvement in back pain and normalization of inflammatory markers at outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

CoNS are a major contributor to human skin flora, a common contaminant of blood cultures, and an important cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections.1,2 These species have a predilection for forming biofilms, making CoNS a major cause of prosthetic device infections.3 S lugdunensis is a CoNS species that was first described in 1988.4 In addition to foreign body–related infections, S lugdunensis has been implicated in bone/joint infections, native valve endocarditis, toxic shock syndrome, and brain abscesses.5-8 Infections due to S lugdunensis are notorious for their aggressive and fulminant courses. With its increased virulence that is atypical of other CoNS, S lugdunensis has understandably been likened more to S aureus.

Prior cases have been reported of S lugdunensis bacteremia in patients using HD. However, the suspected source of bacteremia in these cases has generally been central venous catheters.9-12

Notably, our patient’s AVF was accessed using the buttonhole technique for his home HD sessions, which involves cannulating the same site along the fistula until an epithelialized track has formed from scar tissue. At later HD sessions, duller needles can then be used to cannulate this same track. In contrast, the rope-ladder technique involves cannulating a different site along the fistula until the entire length of the fistula has been used. Patients report higher levels of satisfaction with the buttonhole technique, citing decreased pain, decreased oozing, and the perception of easier cannulation by HD nurses.14 However, the buttonhole technique also appears to confer a higher risk of vascular access-related bloodstream infection when compared with the rope-ladder technique.13,15,16

The buttonhole technique is hypothesized to increase infection risk due to the repeated use of the same site for needle entry. Skin flora, including CoNS, may colonize the scab that forms after dialysis access. If proper sterilization techniques are not rigorously followed, the bacteria colonizing the scab and adjacent skin may be introduced into a patient’s bloodstream during needle puncture. Loss of skin integrity due to frequent cannulation of the same site may also contribute to this increased infection risk. It is relevant to recall that our patient received HD 5 times weekly using the buttonhole technique. The use of the buttonhole technique, frequency of his HD sessions, unclear sterilization methods, and immune dysfunction related to his uncontrolled T2DM and renal disease all likely contributed to our patient’s bacteremia.

Using topical mupirocin for prophylaxis at the intended buttonhole puncture site has shown promising results in decreasing rates of S aureus bacteremia.17 It is unclear whether this intervention also would be effective against S lugdunensis. Increasing rates of mupirocin resistance have been reported among S lugdunensis isolates in dialysis settings, but further research in this area is warranted.18

There are no established treatment guidelines for S lugdunensis infections. In vitro studies suggest that S lugdunensis is susceptible to a wide variety of antibiotics. The mecA gene is a major determinant of methicillin resistance that is commonly observed among CoNS but is uncommonly seen with S lugdunensis.5 In a study by Tan and colleagues of 106 S lugdunensis isolates, they found that only 5 (4.7%) were mecA positive.19

Vancomycin is generally reasonable for empiric antibiotic coverage of staphylococci while speciation is pending. However, if S lugdunensis is isolated, its favorable susceptibility pattern typically allows for de-escalation to an antistaphylococcal β-lactam, such as oxacillin or nafcillin. In cases of bloodstream infections caused by methicillin-sensitive S aureus, treatment with a β-lactam has demonstrated superiority over vancomycin due to the lower rates of treatment failure and mortality with β-lactams.20,21 It is unknown whether β-lactams is superior for treating bacteremia with methicillin-sensitive S lugdunensis.

Our patient’s isolate of S lugdunensis was pansensitive to all antibiotics tested, including penicillin. These susceptibility data were used to guide the de-escalation of his empiric vancomycin and ceftriaxone to oxacillin on hospital day 1.

Due to their virulence, bloodstream infections caused by S aureus and S lugdunensis often require more than timely antimicrobial treatment to ensure eradication. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist to manage patients with S aureus bacteremia has been proven to reduce mortality.25 A similar mortality benefit is seen when infectious disease specialists are consulted for S lugdunensis bacteremia.26 This mortality benefit is likely explained by S lugdunensis’ propensity to cause aggressive, metastatic infections. In such cases, infectious disease consultants may recommend additional imaging (eg, transthoracic echocardiogram) to evaluate for occult sources of infection, advocate for appropriate source control, and guide the selection of an appropriate antibiotic course to ensure resolution of the bacteremia.

Conclusions

S lugdunensis is an increasingly recognized cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections. Given the commonalities in virulence that S lugdunensis shares with S aureus, treatment of bacteremia caused by either species should follow similar management principles: prompt initiation of IV antistaphylococcal therapy, a thorough evaluation for the source(s) of bacteremia as well as metastatic complications, and consultation with an infectious disease specialist. This case report also highlights the importance of considering a patient’s AVF as a potential source for infection even in the absence of localized signs of infection. The buttonhole method of AVF cannulation was thought to be a major contributor to the development and persistence of our patient’s bacteremia. This risk should be discussed with patients using a shared decision-making approach when developing a dialysis treatment plan.

Staphylococcus lugdunensis (S lugdunensis) is a species of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) and a constituent of human skin flora. Unlike other strains of CoNS, however, S lugdunensis has gained notoriety for virulence that resembles Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus). S lugdunensis is now recognized as an important nosocomial pathogen and cause of prosthetic device infections, including vascular catheter infections. We present a case of persistent S lugdunensis bacteremia occurring in a patient on hemodialysis (HD) without any implanted prosthetic materials.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old man with a history of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and end-stage renal disease on home HD via arteriovenous fistula (AVF) presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of subacute progressive low back pain. His symptoms began abruptly 2 weeks prior to presentation without any identifiable trigger or trauma. His pain localized to the lower thoracic spine, radiating anteriorly into his abdomen. He reported tactile fever for several days before presentation but no chills, night sweats, paresthesia, weakness, or bowel/bladder incontinence. He had no recent surgeries, implanted hardware, or invasive procedures involving the spine. HD was performed 5 times a week at home with a family member cannulating his AVF via buttonhole technique. He initially sought evaluation in a community hospital several days prior, where he underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine. He was discharged from the community ED with oral opioids prior to the MRI results. He presented to West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WLAVAMC) ED when MRI results came back indicating abnormalities and he reported recalcitrant pain.

On arrival at WLAVAMC, the patient was afebrile with a heart rate of 107 bpm and blood pressure of 152/97 mm Hg. The remainder of his vital signs were normal. The physical examination revealed midline tenderness on palpation of the distal thoracic and proximal lumbar spine. Muscle strength was 4 of 5 in the bilateral hip flexors, though this was limited by pain. The remainder of his neurologic examination was nonfocal. The cardiac examination was unremarkable with no murmurs auscultated. His left upper extremity AVF had an audible bruit and palpable thrill. The skin examination was notable for acanthosis nigricans but no areas of skin erythema or induration and no obvious stigmata of infective endocarditis.

The initial laboratory workup was remarkable for a white blood cell (WBC) count of 10.0 × 103/µL with left shift, blood urea nitrogen level of 59 mg/dL, and creatinine level of 9.3 mg/dL. The patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 45 mm/h (reference range, ≤ 20 mm/h) and C-reactive protein level was > 8.0 mg/L (reference range, ≤ 0.74 mg/L). Two months prior the hemoglobin A1c had been recorded at 9.9%.

Given his intractable low back pain and elevated inflammatory markers, the patient underwent an MRI of the thoracic and lumbar spine with contrast while in the ED. This MRI revealed abnormal marrow edema in the T11-T12 vertebrae with abnormal fluid signal in the T11-T12 disc space. Subjacent paravertebral edema also was noted. There was no well-defined fluid collection or abnormal signal in the spinal cord. Taken together, these findings were concerning for T11-T12 discitis with osteomyelitis.

Two sets of blood cultures were obtained, and empiric IV vancomycin and ceftriaxone were started. Interventional radiology was consulted for consideration of vertebral biopsy but deferred while awaiting blood culture data. Neurosurgery also was consulted and recommended nonoperative management given his nonfocal neurologic examination and imaging without evidence of abscess. Both sets of blood cultures collected on admission later grew methicillin-sensitive S lugdunensis, a species of CoNS. A transthoracic and later transesophageal echocardiogram did not show any valvular vegetations. The patient’s antibiotic regimen was narrowed to IV oxacillin based on susceptibility data. It was later discovered that both blood cultures obtained during his outside ED encounter were also growing S lugdunensis.

The patient’s S lugdunensis bacteremia persisted for the first 8 days of his admission despite appropriate dosing of oxacillin. During this time, the patient remained afebrile with stable vital signs and a normal WBC count. Positron emission tomography was obtained to evaluate for potential sources of his persistent bacteremia. Aside from tracer uptake in the T11-T12 vertebral bodies and intervertebral disc space, no other areas showed suspicious uptake. Neurosurgery reevaluated the patient and again recommended nonoperative management. Blood cultures cleared and based on recommendations from an infectious disease specialist, the patient was transitioned to IV cefazolin dosed 3 times weekly after HD, which was transitioned to an outpatient dialysis center. The patient continued taking cefazolin for 6 weeks with subsequent improvement in back pain and normalization of inflammatory markers at outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

CoNS are a major contributor to human skin flora, a common contaminant of blood cultures, and an important cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections.1,2 These species have a predilection for forming biofilms, making CoNS a major cause of prosthetic device infections.3 S lugdunensis is a CoNS species that was first described in 1988.4 In addition to foreign body–related infections, S lugdunensis has been implicated in bone/joint infections, native valve endocarditis, toxic shock syndrome, and brain abscesses.5-8 Infections due to S lugdunensis are notorious for their aggressive and fulminant courses. With its increased virulence that is atypical of other CoNS, S lugdunensis has understandably been likened more to S aureus.

Prior cases have been reported of S lugdunensis bacteremia in patients using HD. However, the suspected source of bacteremia in these cases has generally been central venous catheters.9-12

Notably, our patient’s AVF was accessed using the buttonhole technique for his home HD sessions, which involves cannulating the same site along the fistula until an epithelialized track has formed from scar tissue. At later HD sessions, duller needles can then be used to cannulate this same track. In contrast, the rope-ladder technique involves cannulating a different site along the fistula until the entire length of the fistula has been used. Patients report higher levels of satisfaction with the buttonhole technique, citing decreased pain, decreased oozing, and the perception of easier cannulation by HD nurses.14 However, the buttonhole technique also appears to confer a higher risk of vascular access-related bloodstream infection when compared with the rope-ladder technique.13,15,16

The buttonhole technique is hypothesized to increase infection risk due to the repeated use of the same site for needle entry. Skin flora, including CoNS, may colonize the scab that forms after dialysis access. If proper sterilization techniques are not rigorously followed, the bacteria colonizing the scab and adjacent skin may be introduced into a patient’s bloodstream during needle puncture. Loss of skin integrity due to frequent cannulation of the same site may also contribute to this increased infection risk. It is relevant to recall that our patient received HD 5 times weekly using the buttonhole technique. The use of the buttonhole technique, frequency of his HD sessions, unclear sterilization methods, and immune dysfunction related to his uncontrolled T2DM and renal disease all likely contributed to our patient’s bacteremia.