User login

High-dose prophylactic anticoagulation benefits patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

High-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or therapeutic anticoagulation reduced de novo thrombosis in patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, based on data from 334 adults.

Patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia are at increased risk of thrombosis and anticoagulation-related bleeding, therefore data to identify the lowest effective anticoagulant dose are needed, wrote Vincent Labbé, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

Previous studies of different anticoagulation strategies for noncritically ill and critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have shown contrasting results, but some institutions recommend a high-dose regimen in the wake of data showing macrovascular thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 who were treated with standard anticoagulation, the authors wrote.

However, no previously published studies have compared the effectiveness of the three anticoagulation strategies: high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (HD-PA), standard dose prophylactic anticoagulation (SD-PA), and therapeutic anticoagulation (TA), they said.

In the open-label Anticoagulation COVID-19 (ANTICOVID) trial, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers identified consecutively hospitalized adults aged 18 years and older being treated for hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia in 23 centers in France between April 2021 and December 2021.

The patients were randomly assigned to SD-PA (116 patients), HD-PA (111 patients), and TA (112 patients) using low-molecular-weight heparin for 14 days, or until either hospital discharge or weaning from supplemental oxygen for 48 consecutive hours, whichever outcome occurred first. The HD-PA patients received two times the SD-PA dose. The mean age of the patients was 58.3 years, and approximately two-thirds were men; race and ethnicity data were not collected. Participants had no macrovascular thrombosis at the start of the study.

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and time to clinical improvement (defined as the time from randomization to a 2-point improvement on a 7-category respiratory function scale).

The secondary outcome was a combination of safety and efficacy at day 28 that included a composite of thrombosis (ischemic stroke, noncerebrovascular arterial thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary artery thrombosis, and central venous catheter–related deep venous thrombosis), major bleeding, or all-cause death.

For the primary outcome, results were similar among the groups; HD-PA had no significant benefit over SD-PA or TA. All-cause death rates for SD-PA, HD-PA, and TA patients were 14%, 12%, and 13%, respectively. The time to clinical improvement for the three groups was approximately 8 days, 9 days, and 8 days, respectively. Results for the primary outcome were consistent across all prespecified subgroups.

However, HD-PA was associated with a significant fourfold reduced risk of de novo thrombosis compared with SD-PA (5.5% vs. 20.2%) with no observed increase in major bleeding. TA was not associated with any significant improvement in primary or secondary outcomes compared with HD-PA or SD-PA.

The current study findings of no improvement in survival or disease resolution in patients with a higher anticoagulant dose reflects data from previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Our study results together with those of previous RCTs support the premise that the role of microvascular thrombosis in worsening organ dysfunction may be narrower than estimated,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the open-label design and the relatively small sample size, the lack of data on microvascular (vs. macrovascular) thrombosis at baseline, and the predominance of the Delta variant of COVID-19 among the study participants, which may have contributed to a lower mortality rate, the researchers noted.

However, given the significant reduction in de novo thrombosis, the results support the routine use of HD-PA in patients with severe hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, they concluded.

Results inform current clinical practice

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, “Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 manifested the highest risk for thromboembolic complications, especially patients in the intensive care setting,” and early reports suggested that standard prophylactic doses of anticoagulant therapy might be insufficient to prevent thrombotic events, Richard C. Becker, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and Thomas L. Ortel, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Although there have been several studies that have investigated the role of anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, this is the first study that specifically compared a standard, prophylactic dose of low-molecular-weight heparin to a ‘high-dose’ prophylactic regimen and to a full therapeutic dose regimen,” Dr. Ortel said in an interview.

“Given the concerns about an increased thrombotic risk with prophylactic dose anticoagulation, and the potential bleeding risk associated with a full therapeutic dose of anticoagulation, this approach enabled the investigators to explore the efficacy and safety of an intermediate dose between these two extremes,” he said.

In the current study, , a finding that was not observed in other studies investigating anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19,” Dr. Ortel told this news organization. “Much initial concern about progression of disease in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 focused on the role of microvascular thrombosis, which appears to be less important in this process, or, alternatively, less responsive to anticoagulant therapy.”

The clinical takeaway from the study, Dr. Ortel said, is the decreased risk for venous thromboembolism with a high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation strategy compared with a standard-dose prophylactic regimen for patients hospitalized with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, “leading to an improved net clinical outcome.”

Looking ahead, “Additional research is needed to determine whether a higher dose of prophylactic anticoagulation would be beneficial for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia who are not in an intensive care unit setting,” Dr. Ortel said. Studies are needed to determine whether therapeutic interventions are equally beneficial in patients with different coronavirus variants, since most patients in the current study were infected with the Delta variant, he added.

The study was supported by LEO Pharma. Dr. Labbé disclosed grants from LEO Pharma during the study and fees from AOP Health unrelated to the current study.

Dr. Becker disclosed personal fees from Novartis Data Safety Monitoring Board, Ionis Data Safety Monitoring Board, and Basking Biosciences Scientific Advisory Board unrelated to the current study. Dr. Ortel disclosed grants from the National Institutes of Health, Instrumentation Laboratory, Stago, and Siemens; contract fees from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and honoraria from UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

High-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or therapeutic anticoagulation reduced de novo thrombosis in patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, based on data from 334 adults.

Patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia are at increased risk of thrombosis and anticoagulation-related bleeding, therefore data to identify the lowest effective anticoagulant dose are needed, wrote Vincent Labbé, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

Previous studies of different anticoagulation strategies for noncritically ill and critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have shown contrasting results, but some institutions recommend a high-dose regimen in the wake of data showing macrovascular thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 who were treated with standard anticoagulation, the authors wrote.

However, no previously published studies have compared the effectiveness of the three anticoagulation strategies: high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (HD-PA), standard dose prophylactic anticoagulation (SD-PA), and therapeutic anticoagulation (TA), they said.

In the open-label Anticoagulation COVID-19 (ANTICOVID) trial, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers identified consecutively hospitalized adults aged 18 years and older being treated for hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia in 23 centers in France between April 2021 and December 2021.

The patients were randomly assigned to SD-PA (116 patients), HD-PA (111 patients), and TA (112 patients) using low-molecular-weight heparin for 14 days, or until either hospital discharge or weaning from supplemental oxygen for 48 consecutive hours, whichever outcome occurred first. The HD-PA patients received two times the SD-PA dose. The mean age of the patients was 58.3 years, and approximately two-thirds were men; race and ethnicity data were not collected. Participants had no macrovascular thrombosis at the start of the study.

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and time to clinical improvement (defined as the time from randomization to a 2-point improvement on a 7-category respiratory function scale).

The secondary outcome was a combination of safety and efficacy at day 28 that included a composite of thrombosis (ischemic stroke, noncerebrovascular arterial thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary artery thrombosis, and central venous catheter–related deep venous thrombosis), major bleeding, or all-cause death.

For the primary outcome, results were similar among the groups; HD-PA had no significant benefit over SD-PA or TA. All-cause death rates for SD-PA, HD-PA, and TA patients were 14%, 12%, and 13%, respectively. The time to clinical improvement for the three groups was approximately 8 days, 9 days, and 8 days, respectively. Results for the primary outcome were consistent across all prespecified subgroups.

However, HD-PA was associated with a significant fourfold reduced risk of de novo thrombosis compared with SD-PA (5.5% vs. 20.2%) with no observed increase in major bleeding. TA was not associated with any significant improvement in primary or secondary outcomes compared with HD-PA or SD-PA.

The current study findings of no improvement in survival or disease resolution in patients with a higher anticoagulant dose reflects data from previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Our study results together with those of previous RCTs support the premise that the role of microvascular thrombosis in worsening organ dysfunction may be narrower than estimated,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the open-label design and the relatively small sample size, the lack of data on microvascular (vs. macrovascular) thrombosis at baseline, and the predominance of the Delta variant of COVID-19 among the study participants, which may have contributed to a lower mortality rate, the researchers noted.

However, given the significant reduction in de novo thrombosis, the results support the routine use of HD-PA in patients with severe hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, they concluded.

Results inform current clinical practice

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, “Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 manifested the highest risk for thromboembolic complications, especially patients in the intensive care setting,” and early reports suggested that standard prophylactic doses of anticoagulant therapy might be insufficient to prevent thrombotic events, Richard C. Becker, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and Thomas L. Ortel, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Although there have been several studies that have investigated the role of anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, this is the first study that specifically compared a standard, prophylactic dose of low-molecular-weight heparin to a ‘high-dose’ prophylactic regimen and to a full therapeutic dose regimen,” Dr. Ortel said in an interview.

“Given the concerns about an increased thrombotic risk with prophylactic dose anticoagulation, and the potential bleeding risk associated with a full therapeutic dose of anticoagulation, this approach enabled the investigators to explore the efficacy and safety of an intermediate dose between these two extremes,” he said.

In the current study, , a finding that was not observed in other studies investigating anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19,” Dr. Ortel told this news organization. “Much initial concern about progression of disease in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 focused on the role of microvascular thrombosis, which appears to be less important in this process, or, alternatively, less responsive to anticoagulant therapy.”

The clinical takeaway from the study, Dr. Ortel said, is the decreased risk for venous thromboembolism with a high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation strategy compared with a standard-dose prophylactic regimen for patients hospitalized with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, “leading to an improved net clinical outcome.”

Looking ahead, “Additional research is needed to determine whether a higher dose of prophylactic anticoagulation would be beneficial for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia who are not in an intensive care unit setting,” Dr. Ortel said. Studies are needed to determine whether therapeutic interventions are equally beneficial in patients with different coronavirus variants, since most patients in the current study were infected with the Delta variant, he added.

The study was supported by LEO Pharma. Dr. Labbé disclosed grants from LEO Pharma during the study and fees from AOP Health unrelated to the current study.

Dr. Becker disclosed personal fees from Novartis Data Safety Monitoring Board, Ionis Data Safety Monitoring Board, and Basking Biosciences Scientific Advisory Board unrelated to the current study. Dr. Ortel disclosed grants from the National Institutes of Health, Instrumentation Laboratory, Stago, and Siemens; contract fees from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and honoraria from UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

High-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or therapeutic anticoagulation reduced de novo thrombosis in patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, based on data from 334 adults.

Patients with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia are at increased risk of thrombosis and anticoagulation-related bleeding, therefore data to identify the lowest effective anticoagulant dose are needed, wrote Vincent Labbé, MD, of Sorbonne University, Paris, and colleagues.

Previous studies of different anticoagulation strategies for noncritically ill and critically ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have shown contrasting results, but some institutions recommend a high-dose regimen in the wake of data showing macrovascular thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 who were treated with standard anticoagulation, the authors wrote.

However, no previously published studies have compared the effectiveness of the three anticoagulation strategies: high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (HD-PA), standard dose prophylactic anticoagulation (SD-PA), and therapeutic anticoagulation (TA), they said.

In the open-label Anticoagulation COVID-19 (ANTICOVID) trial, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, the researchers identified consecutively hospitalized adults aged 18 years and older being treated for hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia in 23 centers in France between April 2021 and December 2021.

The patients were randomly assigned to SD-PA (116 patients), HD-PA (111 patients), and TA (112 patients) using low-molecular-weight heparin for 14 days, or until either hospital discharge or weaning from supplemental oxygen for 48 consecutive hours, whichever outcome occurred first. The HD-PA patients received two times the SD-PA dose. The mean age of the patients was 58.3 years, and approximately two-thirds were men; race and ethnicity data were not collected. Participants had no macrovascular thrombosis at the start of the study.

The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and time to clinical improvement (defined as the time from randomization to a 2-point improvement on a 7-category respiratory function scale).

The secondary outcome was a combination of safety and efficacy at day 28 that included a composite of thrombosis (ischemic stroke, noncerebrovascular arterial thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary artery thrombosis, and central venous catheter–related deep venous thrombosis), major bleeding, or all-cause death.

For the primary outcome, results were similar among the groups; HD-PA had no significant benefit over SD-PA or TA. All-cause death rates for SD-PA, HD-PA, and TA patients were 14%, 12%, and 13%, respectively. The time to clinical improvement for the three groups was approximately 8 days, 9 days, and 8 days, respectively. Results for the primary outcome were consistent across all prespecified subgroups.

However, HD-PA was associated with a significant fourfold reduced risk of de novo thrombosis compared with SD-PA (5.5% vs. 20.2%) with no observed increase in major bleeding. TA was not associated with any significant improvement in primary or secondary outcomes compared with HD-PA or SD-PA.

The current study findings of no improvement in survival or disease resolution in patients with a higher anticoagulant dose reflects data from previous studies, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Our study results together with those of previous RCTs support the premise that the role of microvascular thrombosis in worsening organ dysfunction may be narrower than estimated,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the open-label design and the relatively small sample size, the lack of data on microvascular (vs. macrovascular) thrombosis at baseline, and the predominance of the Delta variant of COVID-19 among the study participants, which may have contributed to a lower mortality rate, the researchers noted.

However, given the significant reduction in de novo thrombosis, the results support the routine use of HD-PA in patients with severe hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, they concluded.

Results inform current clinical practice

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, “Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 manifested the highest risk for thromboembolic complications, especially patients in the intensive care setting,” and early reports suggested that standard prophylactic doses of anticoagulant therapy might be insufficient to prevent thrombotic events, Richard C. Becker, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and Thomas L. Ortel, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“Although there have been several studies that have investigated the role of anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, this is the first study that specifically compared a standard, prophylactic dose of low-molecular-weight heparin to a ‘high-dose’ prophylactic regimen and to a full therapeutic dose regimen,” Dr. Ortel said in an interview.

“Given the concerns about an increased thrombotic risk with prophylactic dose anticoagulation, and the potential bleeding risk associated with a full therapeutic dose of anticoagulation, this approach enabled the investigators to explore the efficacy and safety of an intermediate dose between these two extremes,” he said.

In the current study, , a finding that was not observed in other studies investigating anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19,” Dr. Ortel told this news organization. “Much initial concern about progression of disease in patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 focused on the role of microvascular thrombosis, which appears to be less important in this process, or, alternatively, less responsive to anticoagulant therapy.”

The clinical takeaway from the study, Dr. Ortel said, is the decreased risk for venous thromboembolism with a high-dose prophylactic anticoagulation strategy compared with a standard-dose prophylactic regimen for patients hospitalized with hypoxemic COVID-19 pneumonia, “leading to an improved net clinical outcome.”

Looking ahead, “Additional research is needed to determine whether a higher dose of prophylactic anticoagulation would be beneficial for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia who are not in an intensive care unit setting,” Dr. Ortel said. Studies are needed to determine whether therapeutic interventions are equally beneficial in patients with different coronavirus variants, since most patients in the current study were infected with the Delta variant, he added.

The study was supported by LEO Pharma. Dr. Labbé disclosed grants from LEO Pharma during the study and fees from AOP Health unrelated to the current study.

Dr. Becker disclosed personal fees from Novartis Data Safety Monitoring Board, Ionis Data Safety Monitoring Board, and Basking Biosciences Scientific Advisory Board unrelated to the current study. Dr. Ortel disclosed grants from the National Institutes of Health, Instrumentation Laboratory, Stago, and Siemens; contract fees from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and honoraria from UpToDate unrelated to the current study.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

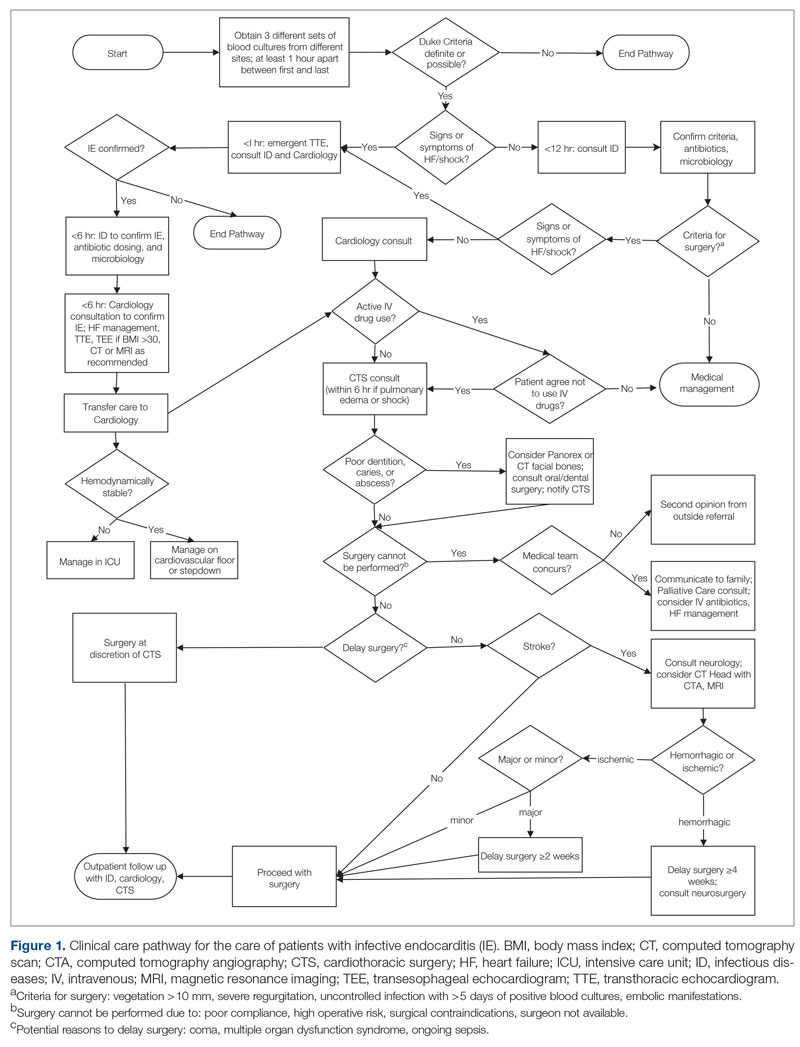

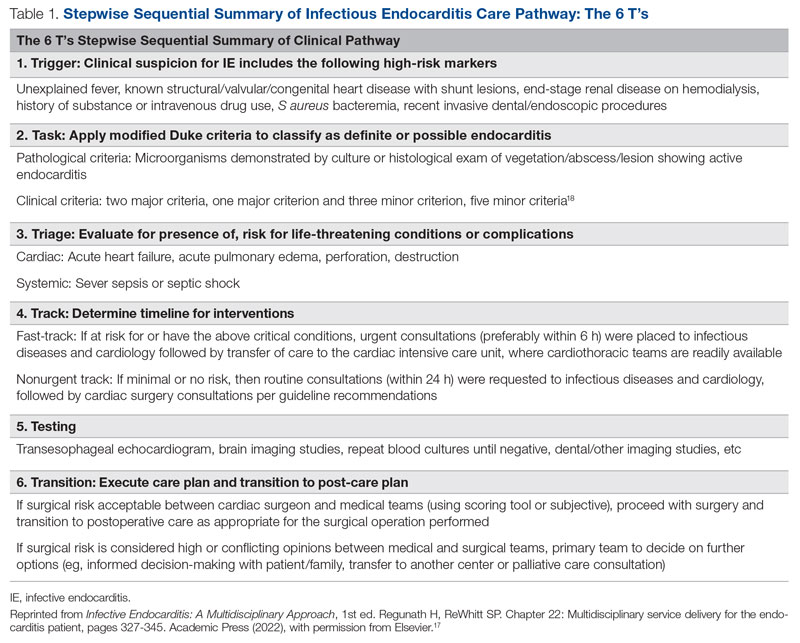

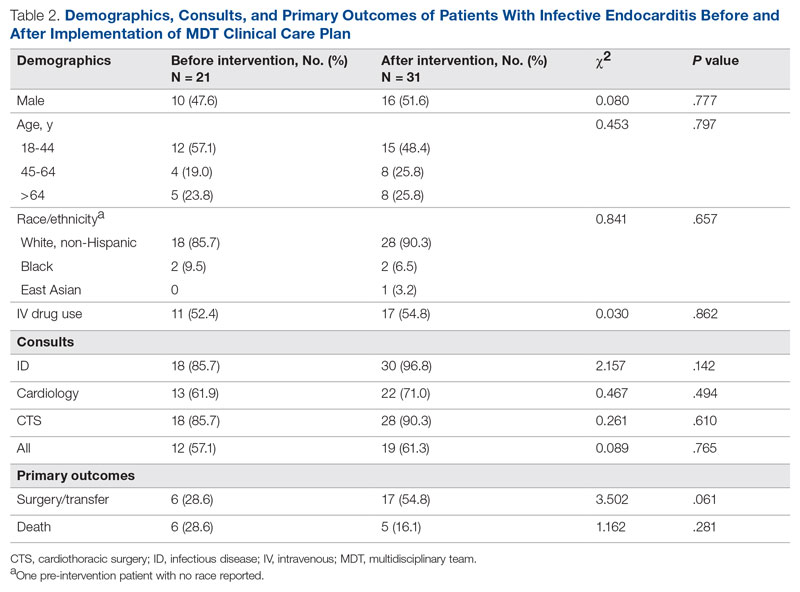

Meet the JCOM Author with Dr. Barkoudah: A Multidisciplinary Team–Based Clinical Care Pathway for Infective Endocarditis

Progressive Primary Cutaneous Nocardiosis in an Immunocompetent Patient

To the Editor:

The organisms of the genus Nocardia are gram-positive, ubiquitous, aerobic actinomycetes found worldwide in soil, decaying organic material, and water.1 The genus Nocardia includes more than 50 species; some species, such as Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia farcinica, Nocardia nova, and Nocardia brasiliensis, are the cause of nocardiosis in humans and animals.2,3 Nocardiosis is a rare and opportunistic infection that predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals; however, up to 30% of infections can occur in immunocompetent hosts.4 Nocardiosis can manifest in 3 disease forms: cutaneous, pulmonary, or disseminated. Cutaneous nocardiosis commonly develops in immunocompetent individuals who have experienced a predisposing traumatic injury to the skin,5 and it can exhibit a diverse variety of clinical manifestations, making diagnosis difficult. We describe a case of serious progressive primary cutaneous nocardiosis with an unusual presentation in an immunocompetent patient.

A 26-year-old immunocompetent man presented with pain, swelling, nodules, abscesses, ulcers, and sinus drainage of the left arm. The left elbow lesion initially developed at the site of a trauma 6 years prior that was painless but was contaminated with mossy soil. The condition slowly progressed over the next 2 years, and the patient experienced increased swelling and eventually developed multiple draining sinus tracts. Over the next 4 years, the lesions multiplied, spreading to the forearm and upper arm; associated severe pain and swelling at the elbow and wrist joint developed. The patient sought medical care at a local hospital and subsequently was diagnosed with suspected cutaneous tuberculosis. The patient was empirically treated with a 6-month course of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol; however, the lesions continued to progress and worsen. The patient had to stop antibiotic treatment because of substantially elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels.

He subsequently was evaluated at our hospital. He had no notable medical history and was afebrile. Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous nodules, abscesses, and ulcers on the left arm. There were several nodules with open sinus tracts and seropurulent crusts along with numerous atrophic, ovoid, stellate scars. Other nodules and ulcers with purulent drainage were located along the lymphatic nodes extending up the patient’s left forearm (Figure 1A). The yellowish-white pus discharge from several active sinuses contained no apparent granules. The lesions were densely distributed along the elbow, wrist, and shoulder, which resulted in associated skin swelling and restricted joint movement. The left axillary lymph nodes were enlarged.

Laboratory analyses revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.6 g/dL (reference range, 13–17.5 g/dL), platelet count of 621×109/L (reference range, 125–350×109/L), and leukocyte count of 14.3×109/L (reference range, 3.5–9.5 ×109/L). C-reactive protein level was 88.4 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). Blood, renal, and liver tests, as well as tumor marker, peripheral blood lymphocyte subset, immunoglobulin, and complement results were within reference ranges. Results for Treponema pallidum and HIV antibody tests were negative. Hepatitis B virus markers were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B e antigen, and hepatitis B core antibody, and the serum concentration of hepatitis B virus DNA was 3.12×107 IU/mL (reference range, <5×102 IU/mL). Computed tomography of the chest and cranium were unremarkable. Ultrasonography of the left arm revealed multiple vertical sinus tracts and several horizontal communicating branches that were accompanied by worm-eaten bone destruction (Figure 2).

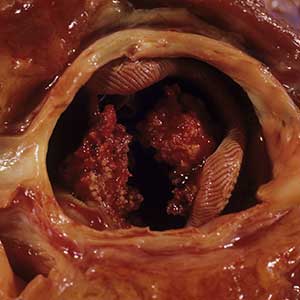

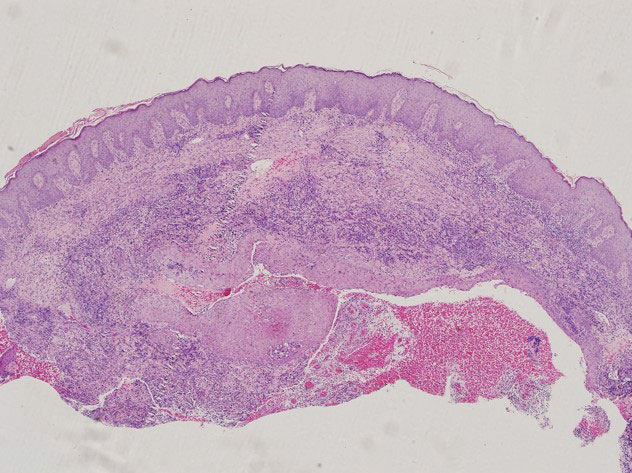

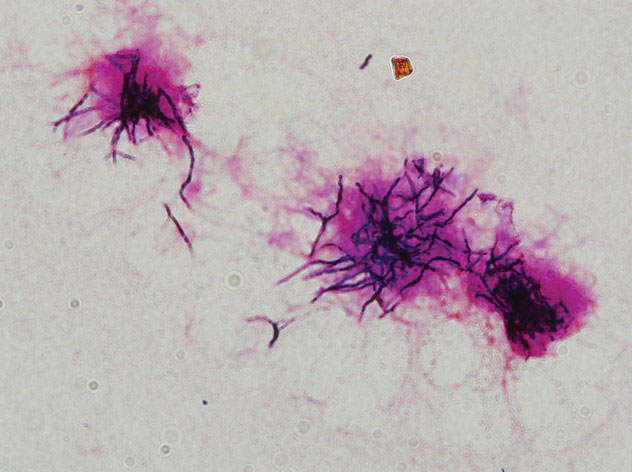

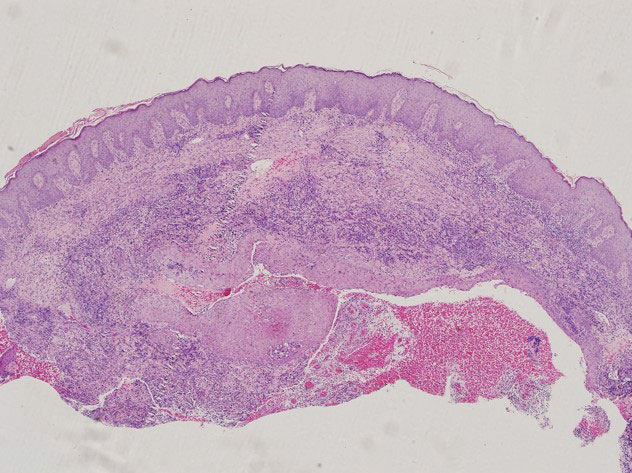

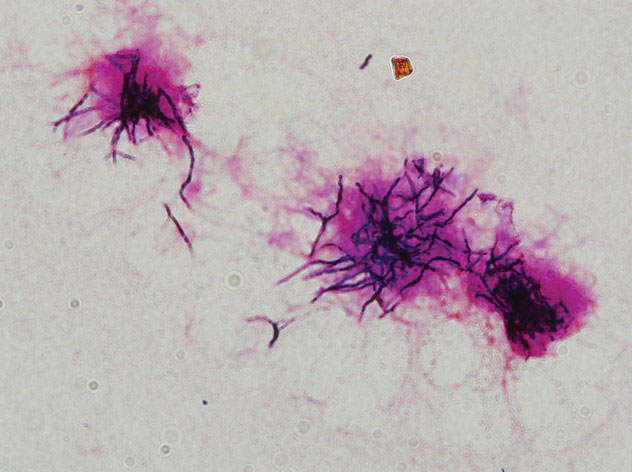

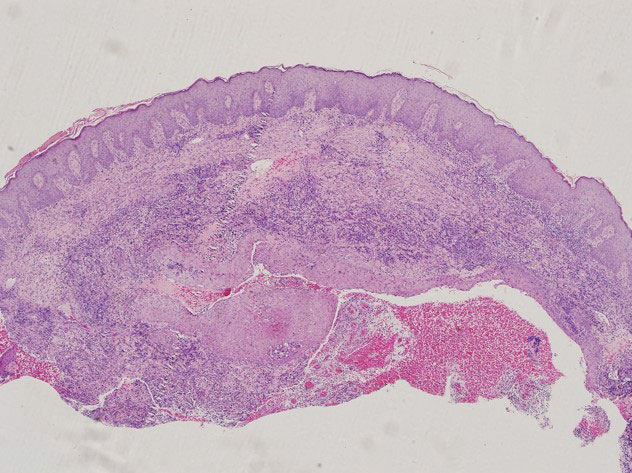

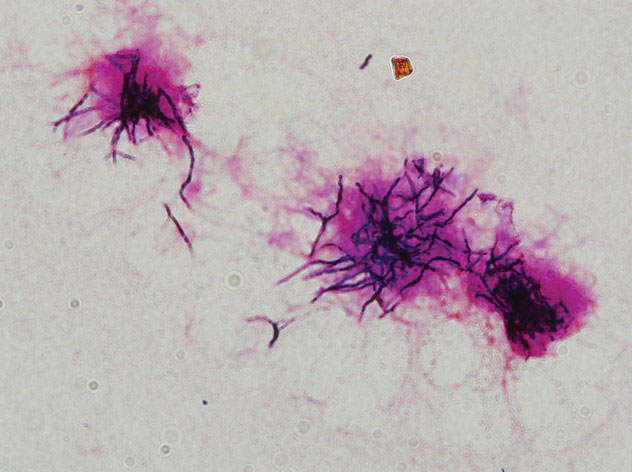

Additional testing included histopathologic staining of a skin tissue specimen—hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast staining—showed nonspecific, diffuse, inflammatory cell infiltration suggestive of chronic suppurative granuloma (Figure 3) but failed to reveal any special strains or organisms. Gram stain examination of the purulent fluid collected from the subcutaneous tissue showed no apparent positive bacillus or filamentous granules. The specimen was then inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose agar and Lowenstein-Jensen medium for fungus and mycobacteria culture, respectively. After 5 days, chalky, yellow, adherent colonies were observed on the Löwenstein-Jensen medium, and after 26 days, yellow crinkled colonies were observed on Sabouraud dextrose agar. The colonies were then inoculated on Columbia blood agar and incubated for 1 week to aid in the identification of organisms. Growth of yellow colonies that were adherent to the agar, moist, and smooth with a velvety surface, as well as a characteristic moldy odor resulted. Gram staining revealed gram-positive, thin, and beaded branching filaments (Figure 4). Based on colony characteristics, physiological properties, and biochemical tests, the isolate was identified as Nocardia. Results of further investigations employing polymerase chain reaction analysis of the skin specimen and bacterial colonies using a Nocardia genus 596-bp fragment of 16S ribosomal RNA primer (forward primer NG1: 5’-ACCGACCACAAGGGG-3’, reverse primer NG2: 5’-GGTTGTAACCTCTTCGA-3’)6 were completely consistent with the reference for identification of N brasiliensis. Evaluation of these results led to a diagnosis of cutaneous nocardiosis after traumatic inoculation.

Because there was a high suspicion of actinophytosis or nocardiosis at admission, the patient received a combination antibiotic treatment with intravenous aqueous penicillin (4 million U every 4 hours) and oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily). Subsequently, treatment was changed to a combination of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) and moxifloxacin (400 mg once daily) based on pathogen identification and antibiotic sensitivity testing. After 1 month of treatment, the cutaneous lesions and left limb swelling dramatically improved and purulent drainage ceased, though some scarring occurred during the healing process. In addition, the mobility of the affected shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints slightly improved. Notable improvement in the mobility and swelling of the joints was observed at 6-month follow-up (Figure 1B). The patient continues to be monitored on an outpatient basis.

Cutaneous nocardiosis is a disfiguring granulomatous infection involving cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue that can progress to cause injury to viscera and bone.7 It has been called one of the great imitators because cutaneous nocardiosis can present in multiple forms,8,9 including mycetoma, sporotrichoid infection, superficial skin infection, and disseminated infection with cutaneous involvement. The differential diagnoses of cutaneous nocardiosis are broad and include tuberculosis; actinomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, blastomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis; other bacterial causes of cellulitis, abscess, or ecthyma; and malignancies.10 The principle method of diagnosis is the identification of Nocardia from the infection site.

Our patient ultimately was diagnosed with primary cutaneous nocardiosis resulting from a traumatic injury to the skin that was contaminated with soil. The clinical manifestation pattern was a compound type, including both mycetoma and sporotrichoid infections. Initially, Nocardia mycetoma occurred with subcutaneous infection by direct extension10,11 and appeared as dense, predominantly painless, swollen lesions. After 4 years, the skin lesions continued to spread linearly to the patient’s upper arm and forearm and manifested as the sporotrichoid infection type with painful swollen lesions at the site of inoculation and painful enlargement of the ipsilateral axillary lymph node.

Although nocardiosis is found worldwide, it is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions such as India, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.12 Nocardiosis most often is observed in individuals aged 20 to 40 years. It affects men more than women, and it commonly occurs in field laborers and cultivators whose occupations involve direct contact with the soil.13 Most lesions are found on the lower extremities, though localized nocardiosis infections can occur in other areas such as the neck, breasts, back, buttocks, and elbows.

Our patient initially was misdiagnosed, and treatment was delayed for several reasons. First, nocardiosis is not common in China, and most clinicians are unfamiliar with the disease. Second, the related lesions do not have specific features, and our patient had a complex clinical presentation that included mycetoma and sporotrichoid infection. Third, the characteristic grain of Nocardia species is small but that of N brasiliensis is even smaller (approximately 0.1–0.2 mm in diameter), which makes visualization difficult in both histopathologic and microbiologic examinations.14 The histopathologic examination results of our patient in the local hospital were nonspecific. Fourth, our patient did not initially go to the hospital but instead purchased some over-the-counter antibiotic ointments for external application because the lesions were painless. Moreover, microbiologic smear and culture examinations were not conducted in the local hospital before administering antituberculosis treatment to the patient. Instead, a polymerase chain reaction examination of skin lesion tissue for tubercle bacilli and atypical mycobacteria was negative. These findings imply that the traditional microbial smear and culture evaluations cannot be omitted. Furthermore, culture examinations should be conducted on multiple skin tissue and purulent fluid specimens to increase the likelihood of detection. These cultures should be monitored for at least 2 to 4 weeks because Nocardia is a slow-growing organism.10

The optimal antimicrobial treatment regimens for nocardiosis have not been firmly established.15 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is regarded as the first-line antimicrobial agent for treatment of nocardial infections. The optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for nocardiosis also has not been determined, and the treatment regimen depends on the severity and extent of the infection as well as on the presence of infection-related complications. The main complication is bone involvement. Notable bony changes include periosteal thickening, osteoporosis, and osteolysis.

We considered the severity of skin lesions and bone marrow invasion in our patient and planned to treat him continually with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole according to the in vitro drug susceptibility test. The patient showed clinical improvement after 1 month of treatment, and he continued to improve after 6 months of treatment. To prevent recurrence, we found it necessary to treat the patient with a long-term antibiotic course over 6 to 12 months.16

Cutaneous nocardiosis remains a diagnostic challenge because of its nonspecific and diverse clinical and histopathological presentations. Diagnosis is further complicated by the inherent difficulty of cultivating and identifying the clinical isolate in the laboratory. A high degree of clinical suspicion followed by successful identification of the organism by a laboratory technologist will aid in the early diagnosis and treatment of the infection, ultimately reducing the risk for complications and morbidity.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

- Fatahi-Bafghi M. Nocardiosis from 1888 to 2017. Microb Pathog. 2018;114:369-384.

- Beaman BL, Burnside J, Edwards B, et al. Nocardial infections in the United States, 1972-1974. J Infect Dis. 1976;134:286-289.

- Lerner PI. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

- Laurent FJ, Provost F, Boiron P. Rapid identification of clinically relevant Nocardia species to genus level by 16S rRNA gene PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:99-102.

- Nguyen NM, Sink JR, Carter AJ, et al. Nocardiosis incognito: primary cutaneous nocardiosis with extension to myositis and pleural infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:33-35.

- Sharna NL, Mahajan VK, Agarwal S, et al. Nocardial mycetoma: diverse clinical presentations. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:635-640.

- Huang L, Chen X, Xu H, et al. Clinical features, identification, antimicrobial resistance patterns of Nocardia species in China: 2009-2017. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;94:165-172.

- Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A, Calderón L, et al. Mycetoma: experience of 482 cases in a single center in Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3102.

- Welsh O, Vero-Cabrera L, Salinas-Carmona MC. Mycetoma. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:195-202.

- Nenoff P, van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH, et al. Eumycetoma and actinomycetoma—an update on causative agents, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1873-1883.

- Emmanuel P, Dumre SP, John S, et al. Mycetoma: a clinical dilemma in resource limited settings. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17:35.

- Reis CMS, Reis-Filho EGM. Mycetomas: an epidemiological, etiological, clinical, laboratory and therapeutic review. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:8-18.

- Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:403-407.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Salinas-Carmona MC. Current treatment for Nocardia infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:2387-2398.

To the Editor:

The organisms of the genus Nocardia are gram-positive, ubiquitous, aerobic actinomycetes found worldwide in soil, decaying organic material, and water.1 The genus Nocardia includes more than 50 species; some species, such as Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia farcinica, Nocardia nova, and Nocardia brasiliensis, are the cause of nocardiosis in humans and animals.2,3 Nocardiosis is a rare and opportunistic infection that predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals; however, up to 30% of infections can occur in immunocompetent hosts.4 Nocardiosis can manifest in 3 disease forms: cutaneous, pulmonary, or disseminated. Cutaneous nocardiosis commonly develops in immunocompetent individuals who have experienced a predisposing traumatic injury to the skin,5 and it can exhibit a diverse variety of clinical manifestations, making diagnosis difficult. We describe a case of serious progressive primary cutaneous nocardiosis with an unusual presentation in an immunocompetent patient.

A 26-year-old immunocompetent man presented with pain, swelling, nodules, abscesses, ulcers, and sinus drainage of the left arm. The left elbow lesion initially developed at the site of a trauma 6 years prior that was painless but was contaminated with mossy soil. The condition slowly progressed over the next 2 years, and the patient experienced increased swelling and eventually developed multiple draining sinus tracts. Over the next 4 years, the lesions multiplied, spreading to the forearm and upper arm; associated severe pain and swelling at the elbow and wrist joint developed. The patient sought medical care at a local hospital and subsequently was diagnosed with suspected cutaneous tuberculosis. The patient was empirically treated with a 6-month course of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol; however, the lesions continued to progress and worsen. The patient had to stop antibiotic treatment because of substantially elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels.

He subsequently was evaluated at our hospital. He had no notable medical history and was afebrile. Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous nodules, abscesses, and ulcers on the left arm. There were several nodules with open sinus tracts and seropurulent crusts along with numerous atrophic, ovoid, stellate scars. Other nodules and ulcers with purulent drainage were located along the lymphatic nodes extending up the patient’s left forearm (Figure 1A). The yellowish-white pus discharge from several active sinuses contained no apparent granules. The lesions were densely distributed along the elbow, wrist, and shoulder, which resulted in associated skin swelling and restricted joint movement. The left axillary lymph nodes were enlarged.

Laboratory analyses revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.6 g/dL (reference range, 13–17.5 g/dL), platelet count of 621×109/L (reference range, 125–350×109/L), and leukocyte count of 14.3×109/L (reference range, 3.5–9.5 ×109/L). C-reactive protein level was 88.4 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). Blood, renal, and liver tests, as well as tumor marker, peripheral blood lymphocyte subset, immunoglobulin, and complement results were within reference ranges. Results for Treponema pallidum and HIV antibody tests were negative. Hepatitis B virus markers were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B e antigen, and hepatitis B core antibody, and the serum concentration of hepatitis B virus DNA was 3.12×107 IU/mL (reference range, <5×102 IU/mL). Computed tomography of the chest and cranium were unremarkable. Ultrasonography of the left arm revealed multiple vertical sinus tracts and several horizontal communicating branches that were accompanied by worm-eaten bone destruction (Figure 2).

Additional testing included histopathologic staining of a skin tissue specimen—hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast staining—showed nonspecific, diffuse, inflammatory cell infiltration suggestive of chronic suppurative granuloma (Figure 3) but failed to reveal any special strains or organisms. Gram stain examination of the purulent fluid collected from the subcutaneous tissue showed no apparent positive bacillus or filamentous granules. The specimen was then inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose agar and Lowenstein-Jensen medium for fungus and mycobacteria culture, respectively. After 5 days, chalky, yellow, adherent colonies were observed on the Löwenstein-Jensen medium, and after 26 days, yellow crinkled colonies were observed on Sabouraud dextrose agar. The colonies were then inoculated on Columbia blood agar and incubated for 1 week to aid in the identification of organisms. Growth of yellow colonies that were adherent to the agar, moist, and smooth with a velvety surface, as well as a characteristic moldy odor resulted. Gram staining revealed gram-positive, thin, and beaded branching filaments (Figure 4). Based on colony characteristics, physiological properties, and biochemical tests, the isolate was identified as Nocardia. Results of further investigations employing polymerase chain reaction analysis of the skin specimen and bacterial colonies using a Nocardia genus 596-bp fragment of 16S ribosomal RNA primer (forward primer NG1: 5’-ACCGACCACAAGGGG-3’, reverse primer NG2: 5’-GGTTGTAACCTCTTCGA-3’)6 were completely consistent with the reference for identification of N brasiliensis. Evaluation of these results led to a diagnosis of cutaneous nocardiosis after traumatic inoculation.

Because there was a high suspicion of actinophytosis or nocardiosis at admission, the patient received a combination antibiotic treatment with intravenous aqueous penicillin (4 million U every 4 hours) and oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily). Subsequently, treatment was changed to a combination of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) and moxifloxacin (400 mg once daily) based on pathogen identification and antibiotic sensitivity testing. After 1 month of treatment, the cutaneous lesions and left limb swelling dramatically improved and purulent drainage ceased, though some scarring occurred during the healing process. In addition, the mobility of the affected shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints slightly improved. Notable improvement in the mobility and swelling of the joints was observed at 6-month follow-up (Figure 1B). The patient continues to be monitored on an outpatient basis.

Cutaneous nocardiosis is a disfiguring granulomatous infection involving cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue that can progress to cause injury to viscera and bone.7 It has been called one of the great imitators because cutaneous nocardiosis can present in multiple forms,8,9 including mycetoma, sporotrichoid infection, superficial skin infection, and disseminated infection with cutaneous involvement. The differential diagnoses of cutaneous nocardiosis are broad and include tuberculosis; actinomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, blastomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis; other bacterial causes of cellulitis, abscess, or ecthyma; and malignancies.10 The principle method of diagnosis is the identification of Nocardia from the infection site.

Our patient ultimately was diagnosed with primary cutaneous nocardiosis resulting from a traumatic injury to the skin that was contaminated with soil. The clinical manifestation pattern was a compound type, including both mycetoma and sporotrichoid infections. Initially, Nocardia mycetoma occurred with subcutaneous infection by direct extension10,11 and appeared as dense, predominantly painless, swollen lesions. After 4 years, the skin lesions continued to spread linearly to the patient’s upper arm and forearm and manifested as the sporotrichoid infection type with painful swollen lesions at the site of inoculation and painful enlargement of the ipsilateral axillary lymph node.

Although nocardiosis is found worldwide, it is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions such as India, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.12 Nocardiosis most often is observed in individuals aged 20 to 40 years. It affects men more than women, and it commonly occurs in field laborers and cultivators whose occupations involve direct contact with the soil.13 Most lesions are found on the lower extremities, though localized nocardiosis infections can occur in other areas such as the neck, breasts, back, buttocks, and elbows.

Our patient initially was misdiagnosed, and treatment was delayed for several reasons. First, nocardiosis is not common in China, and most clinicians are unfamiliar with the disease. Second, the related lesions do not have specific features, and our patient had a complex clinical presentation that included mycetoma and sporotrichoid infection. Third, the characteristic grain of Nocardia species is small but that of N brasiliensis is even smaller (approximately 0.1–0.2 mm in diameter), which makes visualization difficult in both histopathologic and microbiologic examinations.14 The histopathologic examination results of our patient in the local hospital were nonspecific. Fourth, our patient did not initially go to the hospital but instead purchased some over-the-counter antibiotic ointments for external application because the lesions were painless. Moreover, microbiologic smear and culture examinations were not conducted in the local hospital before administering antituberculosis treatment to the patient. Instead, a polymerase chain reaction examination of skin lesion tissue for tubercle bacilli and atypical mycobacteria was negative. These findings imply that the traditional microbial smear and culture evaluations cannot be omitted. Furthermore, culture examinations should be conducted on multiple skin tissue and purulent fluid specimens to increase the likelihood of detection. These cultures should be monitored for at least 2 to 4 weeks because Nocardia is a slow-growing organism.10

The optimal antimicrobial treatment regimens for nocardiosis have not been firmly established.15 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is regarded as the first-line antimicrobial agent for treatment of nocardial infections. The optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for nocardiosis also has not been determined, and the treatment regimen depends on the severity and extent of the infection as well as on the presence of infection-related complications. The main complication is bone involvement. Notable bony changes include periosteal thickening, osteoporosis, and osteolysis.

We considered the severity of skin lesions and bone marrow invasion in our patient and planned to treat him continually with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole according to the in vitro drug susceptibility test. The patient showed clinical improvement after 1 month of treatment, and he continued to improve after 6 months of treatment. To prevent recurrence, we found it necessary to treat the patient with a long-term antibiotic course over 6 to 12 months.16

Cutaneous nocardiosis remains a diagnostic challenge because of its nonspecific and diverse clinical and histopathological presentations. Diagnosis is further complicated by the inherent difficulty of cultivating and identifying the clinical isolate in the laboratory. A high degree of clinical suspicion followed by successful identification of the organism by a laboratory technologist will aid in the early diagnosis and treatment of the infection, ultimately reducing the risk for complications and morbidity.

To the Editor:

The organisms of the genus Nocardia are gram-positive, ubiquitous, aerobic actinomycetes found worldwide in soil, decaying organic material, and water.1 The genus Nocardia includes more than 50 species; some species, such as Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia farcinica, Nocardia nova, and Nocardia brasiliensis, are the cause of nocardiosis in humans and animals.2,3 Nocardiosis is a rare and opportunistic infection that predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals; however, up to 30% of infections can occur in immunocompetent hosts.4 Nocardiosis can manifest in 3 disease forms: cutaneous, pulmonary, or disseminated. Cutaneous nocardiosis commonly develops in immunocompetent individuals who have experienced a predisposing traumatic injury to the skin,5 and it can exhibit a diverse variety of clinical manifestations, making diagnosis difficult. We describe a case of serious progressive primary cutaneous nocardiosis with an unusual presentation in an immunocompetent patient.

A 26-year-old immunocompetent man presented with pain, swelling, nodules, abscesses, ulcers, and sinus drainage of the left arm. The left elbow lesion initially developed at the site of a trauma 6 years prior that was painless but was contaminated with mossy soil. The condition slowly progressed over the next 2 years, and the patient experienced increased swelling and eventually developed multiple draining sinus tracts. Over the next 4 years, the lesions multiplied, spreading to the forearm and upper arm; associated severe pain and swelling at the elbow and wrist joint developed. The patient sought medical care at a local hospital and subsequently was diagnosed with suspected cutaneous tuberculosis. The patient was empirically treated with a 6-month course of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol; however, the lesions continued to progress and worsen. The patient had to stop antibiotic treatment because of substantially elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels.

He subsequently was evaluated at our hospital. He had no notable medical history and was afebrile. Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous nodules, abscesses, and ulcers on the left arm. There were several nodules with open sinus tracts and seropurulent crusts along with numerous atrophic, ovoid, stellate scars. Other nodules and ulcers with purulent drainage were located along the lymphatic nodes extending up the patient’s left forearm (Figure 1A). The yellowish-white pus discharge from several active sinuses contained no apparent granules. The lesions were densely distributed along the elbow, wrist, and shoulder, which resulted in associated skin swelling and restricted joint movement. The left axillary lymph nodes were enlarged.

Laboratory analyses revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.6 g/dL (reference range, 13–17.5 g/dL), platelet count of 621×109/L (reference range, 125–350×109/L), and leukocyte count of 14.3×109/L (reference range, 3.5–9.5 ×109/L). C-reactive protein level was 88.4 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). Blood, renal, and liver tests, as well as tumor marker, peripheral blood lymphocyte subset, immunoglobulin, and complement results were within reference ranges. Results for Treponema pallidum and HIV antibody tests were negative. Hepatitis B virus markers were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B e antigen, and hepatitis B core antibody, and the serum concentration of hepatitis B virus DNA was 3.12×107 IU/mL (reference range, <5×102 IU/mL). Computed tomography of the chest and cranium were unremarkable. Ultrasonography of the left arm revealed multiple vertical sinus tracts and several horizontal communicating branches that were accompanied by worm-eaten bone destruction (Figure 2).

Additional testing included histopathologic staining of a skin tissue specimen—hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast staining—showed nonspecific, diffuse, inflammatory cell infiltration suggestive of chronic suppurative granuloma (Figure 3) but failed to reveal any special strains or organisms. Gram stain examination of the purulent fluid collected from the subcutaneous tissue showed no apparent positive bacillus or filamentous granules. The specimen was then inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose agar and Lowenstein-Jensen medium for fungus and mycobacteria culture, respectively. After 5 days, chalky, yellow, adherent colonies were observed on the Löwenstein-Jensen medium, and after 26 days, yellow crinkled colonies were observed on Sabouraud dextrose agar. The colonies were then inoculated on Columbia blood agar and incubated for 1 week to aid in the identification of organisms. Growth of yellow colonies that were adherent to the agar, moist, and smooth with a velvety surface, as well as a characteristic moldy odor resulted. Gram staining revealed gram-positive, thin, and beaded branching filaments (Figure 4). Based on colony characteristics, physiological properties, and biochemical tests, the isolate was identified as Nocardia. Results of further investigations employing polymerase chain reaction analysis of the skin specimen and bacterial colonies using a Nocardia genus 596-bp fragment of 16S ribosomal RNA primer (forward primer NG1: 5’-ACCGACCACAAGGGG-3’, reverse primer NG2: 5’-GGTTGTAACCTCTTCGA-3’)6 were completely consistent with the reference for identification of N brasiliensis. Evaluation of these results led to a diagnosis of cutaneous nocardiosis after traumatic inoculation.

Because there was a high suspicion of actinophytosis or nocardiosis at admission, the patient received a combination antibiotic treatment with intravenous aqueous penicillin (4 million U every 4 hours) and oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily). Subsequently, treatment was changed to a combination of oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160/800 mg twice daily) and moxifloxacin (400 mg once daily) based on pathogen identification and antibiotic sensitivity testing. After 1 month of treatment, the cutaneous lesions and left limb swelling dramatically improved and purulent drainage ceased, though some scarring occurred during the healing process. In addition, the mobility of the affected shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints slightly improved. Notable improvement in the mobility and swelling of the joints was observed at 6-month follow-up (Figure 1B). The patient continues to be monitored on an outpatient basis.

Cutaneous nocardiosis is a disfiguring granulomatous infection involving cutaneous and subcutaneous tissue that can progress to cause injury to viscera and bone.7 It has been called one of the great imitators because cutaneous nocardiosis can present in multiple forms,8,9 including mycetoma, sporotrichoid infection, superficial skin infection, and disseminated infection with cutaneous involvement. The differential diagnoses of cutaneous nocardiosis are broad and include tuberculosis; actinomycosis; deep fungal infections such as sporotrichosis, blastomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis; other bacterial causes of cellulitis, abscess, or ecthyma; and malignancies.10 The principle method of diagnosis is the identification of Nocardia from the infection site.

Our patient ultimately was diagnosed with primary cutaneous nocardiosis resulting from a traumatic injury to the skin that was contaminated with soil. The clinical manifestation pattern was a compound type, including both mycetoma and sporotrichoid infections. Initially, Nocardia mycetoma occurred with subcutaneous infection by direct extension10,11 and appeared as dense, predominantly painless, swollen lesions. After 4 years, the skin lesions continued to spread linearly to the patient’s upper arm and forearm and manifested as the sporotrichoid infection type with painful swollen lesions at the site of inoculation and painful enlargement of the ipsilateral axillary lymph node.

Although nocardiosis is found worldwide, it is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions such as India, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.12 Nocardiosis most often is observed in individuals aged 20 to 40 years. It affects men more than women, and it commonly occurs in field laborers and cultivators whose occupations involve direct contact with the soil.13 Most lesions are found on the lower extremities, though localized nocardiosis infections can occur in other areas such as the neck, breasts, back, buttocks, and elbows.

Our patient initially was misdiagnosed, and treatment was delayed for several reasons. First, nocardiosis is not common in China, and most clinicians are unfamiliar with the disease. Second, the related lesions do not have specific features, and our patient had a complex clinical presentation that included mycetoma and sporotrichoid infection. Third, the characteristic grain of Nocardia species is small but that of N brasiliensis is even smaller (approximately 0.1–0.2 mm in diameter), which makes visualization difficult in both histopathologic and microbiologic examinations.14 The histopathologic examination results of our patient in the local hospital were nonspecific. Fourth, our patient did not initially go to the hospital but instead purchased some over-the-counter antibiotic ointments for external application because the lesions were painless. Moreover, microbiologic smear and culture examinations were not conducted in the local hospital before administering antituberculosis treatment to the patient. Instead, a polymerase chain reaction examination of skin lesion tissue for tubercle bacilli and atypical mycobacteria was negative. These findings imply that the traditional microbial smear and culture evaluations cannot be omitted. Furthermore, culture examinations should be conducted on multiple skin tissue and purulent fluid specimens to increase the likelihood of detection. These cultures should be monitored for at least 2 to 4 weeks because Nocardia is a slow-growing organism.10

The optimal antimicrobial treatment regimens for nocardiosis have not been firmly established.15 Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is regarded as the first-line antimicrobial agent for treatment of nocardial infections. The optimal duration of antimicrobial therapy for nocardiosis also has not been determined, and the treatment regimen depends on the severity and extent of the infection as well as on the presence of infection-related complications. The main complication is bone involvement. Notable bony changes include periosteal thickening, osteoporosis, and osteolysis.

We considered the severity of skin lesions and bone marrow invasion in our patient and planned to treat him continually with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole according to the in vitro drug susceptibility test. The patient showed clinical improvement after 1 month of treatment, and he continued to improve after 6 months of treatment. To prevent recurrence, we found it necessary to treat the patient with a long-term antibiotic course over 6 to 12 months.16

Cutaneous nocardiosis remains a diagnostic challenge because of its nonspecific and diverse clinical and histopathological presentations. Diagnosis is further complicated by the inherent difficulty of cultivating and identifying the clinical isolate in the laboratory. A high degree of clinical suspicion followed by successful identification of the organism by a laboratory technologist will aid in the early diagnosis and treatment of the infection, ultimately reducing the risk for complications and morbidity.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

- Fatahi-Bafghi M. Nocardiosis from 1888 to 2017. Microb Pathog. 2018;114:369-384.

- Beaman BL, Burnside J, Edwards B, et al. Nocardial infections in the United States, 1972-1974. J Infect Dis. 1976;134:286-289.

- Lerner PI. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

- Laurent FJ, Provost F, Boiron P. Rapid identification of clinically relevant Nocardia species to genus level by 16S rRNA gene PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:99-102.

- Nguyen NM, Sink JR, Carter AJ, et al. Nocardiosis incognito: primary cutaneous nocardiosis with extension to myositis and pleural infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:33-35.

- Sharna NL, Mahajan VK, Agarwal S, et al. Nocardial mycetoma: diverse clinical presentations. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:635-640.

- Huang L, Chen X, Xu H, et al. Clinical features, identification, antimicrobial resistance patterns of Nocardia species in China: 2009-2017. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;94:165-172.

- Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A, Calderón L, et al. Mycetoma: experience of 482 cases in a single center in Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3102.

- Welsh O, Vero-Cabrera L, Salinas-Carmona MC. Mycetoma. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:195-202.

- Nenoff P, van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH, et al. Eumycetoma and actinomycetoma—an update on causative agents, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1873-1883.

- Emmanuel P, Dumre SP, John S, et al. Mycetoma: a clinical dilemma in resource limited settings. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17:35.

- Reis CMS, Reis-Filho EGM. Mycetomas: an epidemiological, etiological, clinical, laboratory and therapeutic review. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:8-18.

- Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:403-407.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Salinas-Carmona MC. Current treatment for Nocardia infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:2387-2398.

- McNeil MM, Brown JM. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357-417.

- Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:259-282.

- Fatahi-Bafghi M. Nocardiosis from 1888 to 2017. Microb Pathog. 2018;114:369-384.

- Beaman BL, Burnside J, Edwards B, et al. Nocardial infections in the United States, 1972-1974. J Infect Dis. 1976;134:286-289.

- Lerner PI. Nocardiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:891-903.

- Laurent FJ, Provost F, Boiron P. Rapid identification of clinically relevant Nocardia species to genus level by 16S rRNA gene PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:99-102.

- Nguyen NM, Sink JR, Carter AJ, et al. Nocardiosis incognito: primary cutaneous nocardiosis with extension to myositis and pleural infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:33-35.

- Sharna NL, Mahajan VK, Agarwal S, et al. Nocardial mycetoma: diverse clinical presentations. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:635-640.

- Huang L, Chen X, Xu H, et al. Clinical features, identification, antimicrobial resistance patterns of Nocardia species in China: 2009-2017. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;94:165-172.

- Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A, Calderón L, et al. Mycetoma: experience of 482 cases in a single center in Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3102.

- Welsh O, Vero-Cabrera L, Salinas-Carmona MC. Mycetoma. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:195-202.

- Nenoff P, van de Sande WWJ, Fahal AH, et al. Eumycetoma and actinomycetoma—an update on causative agents, epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics and therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1873-1883.

- Emmanuel P, Dumre SP, John S, et al. Mycetoma: a clinical dilemma in resource limited settings. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17:35.

- Reis CMS, Reis-Filho EGM. Mycetomas: an epidemiological, etiological, clinical, laboratory and therapeutic review. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:8-18.

- Wilson JW. Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:403-407.

- Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, Salinas-Carmona MC. Current treatment for Nocardia infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:2387-2398.

Practice Points

- Although unusual, cutaneous nocardiosis can present with both mycetoma and sporotrichoid infection, which should be treated based on pathogen identification and antibiotic sensitivity testing.

- A high degree of clinical suspicion by clinicians followed by successful identification of the organism by a laboratory technologist will aid in the early diagnosis and treatment of the infection, ultimately reducing the risk for complications and morbidity.

Spotting STIs: Vaginal swabs work best

Vaginal swabs are more effective than urine analysis in detecting certain types of sexually transmitted infections, researchers have found.

In the study, which was published online in the Annals of Family Medicine, investigators found that the diagnostic sensitivity of commercially available vaginal swabs was significantly greater than that of urine tests in detecting certain infections, including those caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis.

Researchers studied chlamydia and gonorrhea, which are two of the most frequently reported STIs in the United States. Trichomoniasis is the most curable nonviral STI globally, with 156 million cases worldwide in 2016.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long recommended that vaginal swabs be used to produce optimal samples.

But despite the CDC’s recommendation, urine analysis for these STIs is more commonly used than vaginal swabs among U.S. health care providers.

“We’re using a poor sample type, and we can do better,” said Barbara Van Der Pol, PhD, a professor of medicine and public health at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and an author of the new study, a meta-analysis of 97 studies published between 1995 and 2021.

Vaginal swabs for chlamydia trachomatis had a diagnostic sensitivity of 94.1% (95% confidence interval, 93.2%-94.9%; P < .001), higher than urine testing (86.9%; 95% CI, 85.6%-88.0%; P < .001). The pooled sensitivity estimates for Neisseria gonorrhoeae were 96.5% (95% CI, 94.8%-97.7%; P < .001) for vaginal swabs and 90.7% (95% CI, 88.4%-92.5%; P < .001) for urine specimens.

The difference in pooled sensitivity estimates between vaginal swabs and urine analyses for Trichomonas vaginalis was 98% (95% CI, 97.0%-98.7%; P < .001) for vaginal swabs and 95.1% (95% CI, 93.6%-96.3%) for urine specimens.

STIs included in the study are not typically found in the urethra and appear in urine analyses only if cervical or vaginal cells have dripped into a urine sample. Dr. Van Der Pol and her colleagues estimated that the use of urine samples rather than vaginal swabs may result in more than 400,000 undiagnosed infections annually.

Undiagnosed and untreated STIs can lead to transmissions of the infection as well as infertility and can have negative effects on romantic relationships, according to Dr. Van Der Pol.

Sarah Wood, MD, an attending physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said some health care providers may use urine analysis because patients may be more comfortable with this method. The approach also can be more convenient for medical offices: All they must do is hand a specimen container to the patient.

Conversations between clinicians and patients about vaginal swabbing may be considered “sensitive” and the swabbing more invasive, Dr. Wood, an author of an editorial accompanying the journal article, said. Clinicians may also lack awareness that the swab is a more sensitive method of detecting these STIs.

“We all want to do what’s right for our patient, but we often don’t know what’s right for the patient,” Dr. Wood said. “I don’t think people are really aware of a potential real difference in outcomes with one method over the other.”

Dr. Wood advised making STI screening using vaginal swabs more common by “offering universal opt-out screening, so not waiting until you find out if someone’s having sex but just sort of saying, ‘Hey, across our practice, we screen everybody for chlamydia. Is that something that you want to do today?’ That approach sort of takes out the piece of talking about sex, talking about sexual activity.”

Dr. Van Der Pol, who said she has worked in STI diagnostics for 40 years, said she was not surprised by the results and hopes the study changes how samples are collected and used.

“I really hope that it influences practice so that we really start using vaginal swabs, because it gives us better diagnostics for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” Dr. Van Der Pol said.

“Also, then starting to think about comprehensive women’s care in such a way that they actually order other tests on that same sample if a woman is presenting with complaints.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaginal swabs are more effective than urine analysis in detecting certain types of sexually transmitted infections, researchers have found.

In the study, which was published online in the Annals of Family Medicine, investigators found that the diagnostic sensitivity of commercially available vaginal swabs was significantly greater than that of urine tests in detecting certain infections, including those caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis.

Researchers studied chlamydia and gonorrhea, which are two of the most frequently reported STIs in the United States. Trichomoniasis is the most curable nonviral STI globally, with 156 million cases worldwide in 2016.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long recommended that vaginal swabs be used to produce optimal samples.

But despite the CDC’s recommendation, urine analysis for these STIs is more commonly used than vaginal swabs among U.S. health care providers.

“We’re using a poor sample type, and we can do better,” said Barbara Van Der Pol, PhD, a professor of medicine and public health at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and an author of the new study, a meta-analysis of 97 studies published between 1995 and 2021.

Vaginal swabs for chlamydia trachomatis had a diagnostic sensitivity of 94.1% (95% confidence interval, 93.2%-94.9%; P < .001), higher than urine testing (86.9%; 95% CI, 85.6%-88.0%; P < .001). The pooled sensitivity estimates for Neisseria gonorrhoeae were 96.5% (95% CI, 94.8%-97.7%; P < .001) for vaginal swabs and 90.7% (95% CI, 88.4%-92.5%; P < .001) for urine specimens.

The difference in pooled sensitivity estimates between vaginal swabs and urine analyses for Trichomonas vaginalis was 98% (95% CI, 97.0%-98.7%; P < .001) for vaginal swabs and 95.1% (95% CI, 93.6%-96.3%) for urine specimens.

STIs included in the study are not typically found in the urethra and appear in urine analyses only if cervical or vaginal cells have dripped into a urine sample. Dr. Van Der Pol and her colleagues estimated that the use of urine samples rather than vaginal swabs may result in more than 400,000 undiagnosed infections annually.

Undiagnosed and untreated STIs can lead to transmissions of the infection as well as infertility and can have negative effects on romantic relationships, according to Dr. Van Der Pol.

Sarah Wood, MD, an attending physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said some health care providers may use urine analysis because patients may be more comfortable with this method. The approach also can be more convenient for medical offices: All they must do is hand a specimen container to the patient.

Conversations between clinicians and patients about vaginal swabbing may be considered “sensitive” and the swabbing more invasive, Dr. Wood, an author of an editorial accompanying the journal article, said. Clinicians may also lack awareness that the swab is a more sensitive method of detecting these STIs.

“We all want to do what’s right for our patient, but we often don’t know what’s right for the patient,” Dr. Wood said. “I don’t think people are really aware of a potential real difference in outcomes with one method over the other.”

Dr. Wood advised making STI screening using vaginal swabs more common by “offering universal opt-out screening, so not waiting until you find out if someone’s having sex but just sort of saying, ‘Hey, across our practice, we screen everybody for chlamydia. Is that something that you want to do today?’ That approach sort of takes out the piece of talking about sex, talking about sexual activity.”

Dr. Van Der Pol, who said she has worked in STI diagnostics for 40 years, said she was not surprised by the results and hopes the study changes how samples are collected and used.

“I really hope that it influences practice so that we really start using vaginal swabs, because it gives us better diagnostics for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” Dr. Van Der Pol said.

“Also, then starting to think about comprehensive women’s care in such a way that they actually order other tests on that same sample if a woman is presenting with complaints.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaginal swabs are more effective than urine analysis in detecting certain types of sexually transmitted infections, researchers have found.

In the study, which was published online in the Annals of Family Medicine, investigators found that the diagnostic sensitivity of commercially available vaginal swabs was significantly greater than that of urine tests in detecting certain infections, including those caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Trichomonas vaginalis.

Researchers studied chlamydia and gonorrhea, which are two of the most frequently reported STIs in the United States. Trichomoniasis is the most curable nonviral STI globally, with 156 million cases worldwide in 2016.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has long recommended that vaginal swabs be used to produce optimal samples.

But despite the CDC’s recommendation, urine analysis for these STIs is more commonly used than vaginal swabs among U.S. health care providers.

“We’re using a poor sample type, and we can do better,” said Barbara Van Der Pol, PhD, a professor of medicine and public health at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and an author of the new study, a meta-analysis of 97 studies published between 1995 and 2021.

Vaginal swabs for chlamydia trachomatis had a diagnostic sensitivity of 94.1% (95% confidence interval, 93.2%-94.9%; P < .001), higher than urine testing (86.9%; 95% CI, 85.6%-88.0%; P < .001). The pooled sensitivity estimates for Neisseria gonorrhoeae were 96.5% (95% CI, 94.8%-97.7%; P < .001) for vaginal swabs and 90.7% (95% CI, 88.4%-92.5%; P < .001) for urine specimens.

The difference in pooled sensitivity estimates between vaginal swabs and urine analyses for Trichomonas vaginalis was 98% (95% CI, 97.0%-98.7%; P < .001) for vaginal swabs and 95.1% (95% CI, 93.6%-96.3%) for urine specimens.

STIs included in the study are not typically found in the urethra and appear in urine analyses only if cervical or vaginal cells have dripped into a urine sample. Dr. Van Der Pol and her colleagues estimated that the use of urine samples rather than vaginal swabs may result in more than 400,000 undiagnosed infections annually.

Undiagnosed and untreated STIs can lead to transmissions of the infection as well as infertility and can have negative effects on romantic relationships, according to Dr. Van Der Pol.

Sarah Wood, MD, an attending physician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said some health care providers may use urine analysis because patients may be more comfortable with this method. The approach also can be more convenient for medical offices: All they must do is hand a specimen container to the patient.

Conversations between clinicians and patients about vaginal swabbing may be considered “sensitive” and the swabbing more invasive, Dr. Wood, an author of an editorial accompanying the journal article, said. Clinicians may also lack awareness that the swab is a more sensitive method of detecting these STIs.

“We all want to do what’s right for our patient, but we often don’t know what’s right for the patient,” Dr. Wood said. “I don’t think people are really aware of a potential real difference in outcomes with one method over the other.”

Dr. Wood advised making STI screening using vaginal swabs more common by “offering universal opt-out screening, so not waiting until you find out if someone’s having sex but just sort of saying, ‘Hey, across our practice, we screen everybody for chlamydia. Is that something that you want to do today?’ That approach sort of takes out the piece of talking about sex, talking about sexual activity.”

Dr. Van Der Pol, who said she has worked in STI diagnostics for 40 years, said she was not surprised by the results and hopes the study changes how samples are collected and used.

“I really hope that it influences practice so that we really start using vaginal swabs, because it gives us better diagnostics for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” Dr. Van Der Pol said.

“Also, then starting to think about comprehensive women’s care in such a way that they actually order other tests on that same sample if a woman is presenting with complaints.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

eNose knows S. aureus in children with cystic fibrosis

An electronic nose effectively detected Staphylococcus aureus in children with cystic fibrosis, based on data from 100 individuals.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen found in children with cystic fibrosis (CF), but current detection strategies are based on microbiology cultures, wrote Johann-Christoph Licht, a medical student at the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

Noninvasive tools are needed to screen children with CF early for respiratory infections, the researchers said.

The electronic Nose (eNose) is a technology that detects volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Although exhaled breath can be used to create distinct profiles, the ability of eNose to identify S. aureus (SA) in the breath of children with CF remains unclear, they wrote.

In a study published in the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, the researchers analyzed breath profiles data from 100 children with CF. The study population included children aged 5-18 years with clinically stable CF who were recruited from CF clinics during routine visits. Patients with a CF pulmonary exacerbation were excluded.

The children’s median predicted FEV1 was 91%. The researchers collected sputum from 67 patients and throat cultures for 33 patients. A group of 25 age-matched healthy controls served for comparison.

Eighty patients were positive for CF pathogens. Of these, 67 were positive for SA (44 with SA only and 23 with SA and at least one other pathogen).

Overall, patients with any CF pathogen on airway cultures were identified compared to airway cultures with no CF pathogens with an area under the curve accuracy of 79.0%.

Previous studies have shown a high rate of accuracy using eNose to detect Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA). In the current study, the area under the curve accuracy for PA infection compared to no CF pathogens was 78%. Both SA-specific and PA-specific signatures were driven by different sensors in the eNose, which suggests pathogen-specific breath signatures, the researchers wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small number of patients with positive airway cultures for PA and the lack of data on variability of measures over time or treatment-induced changes, the researchers noted.