User login

Group Clinic for Chemoprevention of Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Pilot Study

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has an estimated incidence of more than 2.5 million cases per year in the United States.1 Its precursor lesion, actinic keratosis (AK), had an estimated prevalence of 39.5 million cases in the United States in 2004.2 The dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center in Rhode Island exerts consistent efforts to treat both SCC and AK by prescribing topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and lifestyle changes that include avoiding sun exposure, wearing protective clothing, and using effective sunscreen.3 A single course of topical 5-FU in veterans has been shown to decrease the risk for SCC by 74% during the year after treatment and also improve AK clearance rates.4,5

Effectiveness of 5-FU for secondary prevention can be decreased by patient misunderstandings, such as applying 5-FU for too short a time or using the corticosteroid cream prematurely, as well as patient nonadherence due to expected adverse skin reactions to 5-FU.6 Education and reassurance before and during therapy maximize patient compliance but can be difficult to accomplish in clinics when time is in short supply. During standard 5-FU treatment at the Providence VA Medical Center, the provider prescribes 5-FU and posttherapy corticosteroid cream at a clinic visit after an informed consent process that includes reviewing with the patient a color handout depicting the expected adverse skin reaction. Patients who later experience severe inflammation and anxiety call the clinic and are overbooked as needed.

To address the practical obstacles to the patient experience with topical 5-FU therapy, we developed a group chemoprevention clinic based on the shared medical appointment (SMA) model. Shared medical appointments, during which multiple patients are scheduled at the same visit with 1 or more health care providers, promote patient risk reduction and guideline adherence in complex diseases, such as chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus, through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral changes through group support.7-13 To increase efficiency in the group chemoprevention clinic, we integrated dermatology nurses and nurse practitioners from the chronic care model into the group medical visits, which ran from September 2016 through March 2017. Because veterans could interact with peers undergoing the same treatment, we hypothesized that use of the cream in a group setting would provide positive reinforcement during the course of therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. We conducted a retrospective review of medical records of the patients involved in this pilot study to evaluate this model.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Providence VA Medical Center. Informed consent was waived because this study was a retrospective review of medical records.

Study Population

We offered participation in a group chemoprevention clinic based on the SMA model for patients of the dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center who were planning to start 5-FU in the fall of 2016. Patients were asked if they were interested in participating in a group clinic to receive their 5-FU treatment. Patients who were established dermatology patients within the Veterans Affairs system and had scheduled annual full-body skin examinations were included; patients were not excluded if they had a prior diagnosis of AK but had not been previously treated with 5-FU.

Design

Each SMA group consisted of 3 to 4 patients who met initially to receive the 5-FU medication and attend a 10-minute live presentation that included information on the dangers and causes of SCC and AK, treatment options, directions for using 5-FU, expected spectrum of side effects, and how to minimize the discomfort of treatment side effects. Patients had field treatment limited to areas with clinically apparent AKs on the face and ears. They were prescribed 5-FU cream 5% twice daily.

One physician, one nurse practitioner, and one registered nurse were present at each 1-hour clinic. Patients arrived and were checked in individually by the providers. At check-in, the provider handed the patient a printout of his/her current medication list and a pen to make any necessary corrections. This list was reviewed privately with the patient so the provider could reconcile the medication list and review the patient’s medical history and so the patient could provide informed consent. After, the patient had the opportunity to select a seat from chairs arranged in a circle. There was a live PowerPoint presentation given at the beginning of the clinic with a question-and-answer session immediately following that contained information about the disease and medication process. Clinicians assisted the patients with the initial application of 5-FU in the large group room, and each patient received a handout with information about AKs and a 40-g tube of the 5-FU cream.

This same group then met again 2 weeks later, at which time most patients were experiencing expected adverse skin reactions. At that time, there was a 10-minute live presentation that congratulated the patients on their success in the treatment process, reviewed what to expect in the following weeks, and reinforced the importance of future sun-protective practices. At each visit, photographs and feedback about the group setting were obtained in the large group room. After photographing and rating each patient’s skin reaction severity, the clinicians advised each patient either to continue the 5-FU medication for another week or to discontinue it and apply the triamcinolone cream 0.1% up to 4 times daily as needed for up to 7 days. Each patient received the prescription corticosteroid cream and a gift, courtesy of the VA Voluntary Service Program, of a 360-degree brimmed hat and sunscreen. Time for questions or concerns was available at both sessions.

Data Collection

We reviewed medical records via the Computerized Patient Record System, a nationally accessible electronic health record system, for all patients who participated in the SMA visits from September 2016 through March 2017. Any patient who attended the initial visit but declined therapy at that time was excluded.

Outcomes included attendance at both appointments, stated completion of 14 days of 5-FU treatment, and evidence of 5-FU use according to a validated numeric scale of skin reaction severity.14 We recorded telephone calls and other dermatology clinic and teledermatology appointments during the 3 weeks after the first appointment and the number of dermatology clinic appointments 6 months before and after the SMA for side effects related to 5-FU treatment. Feedback about treatment in the group setting was obtained at both visits.

Results

A total of 16 male patients attended the SMAs, and 14 attended both sessions. Of the 2 patients who were excluded from the study, 1 declined to be scheduled for the second group appointment, and the other was scheduled and confirmed but did not come for his appointment. The mean age was 72 years.

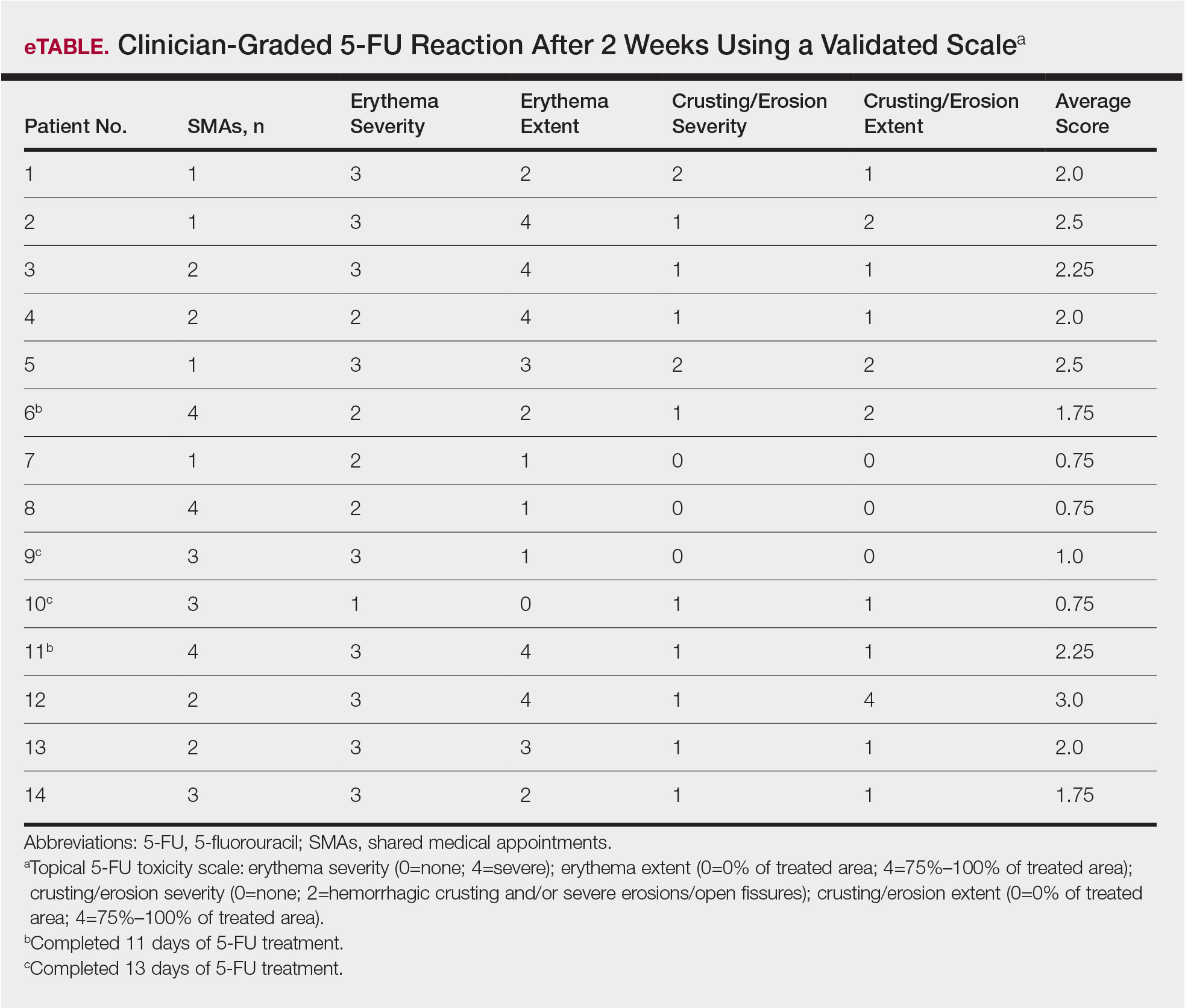

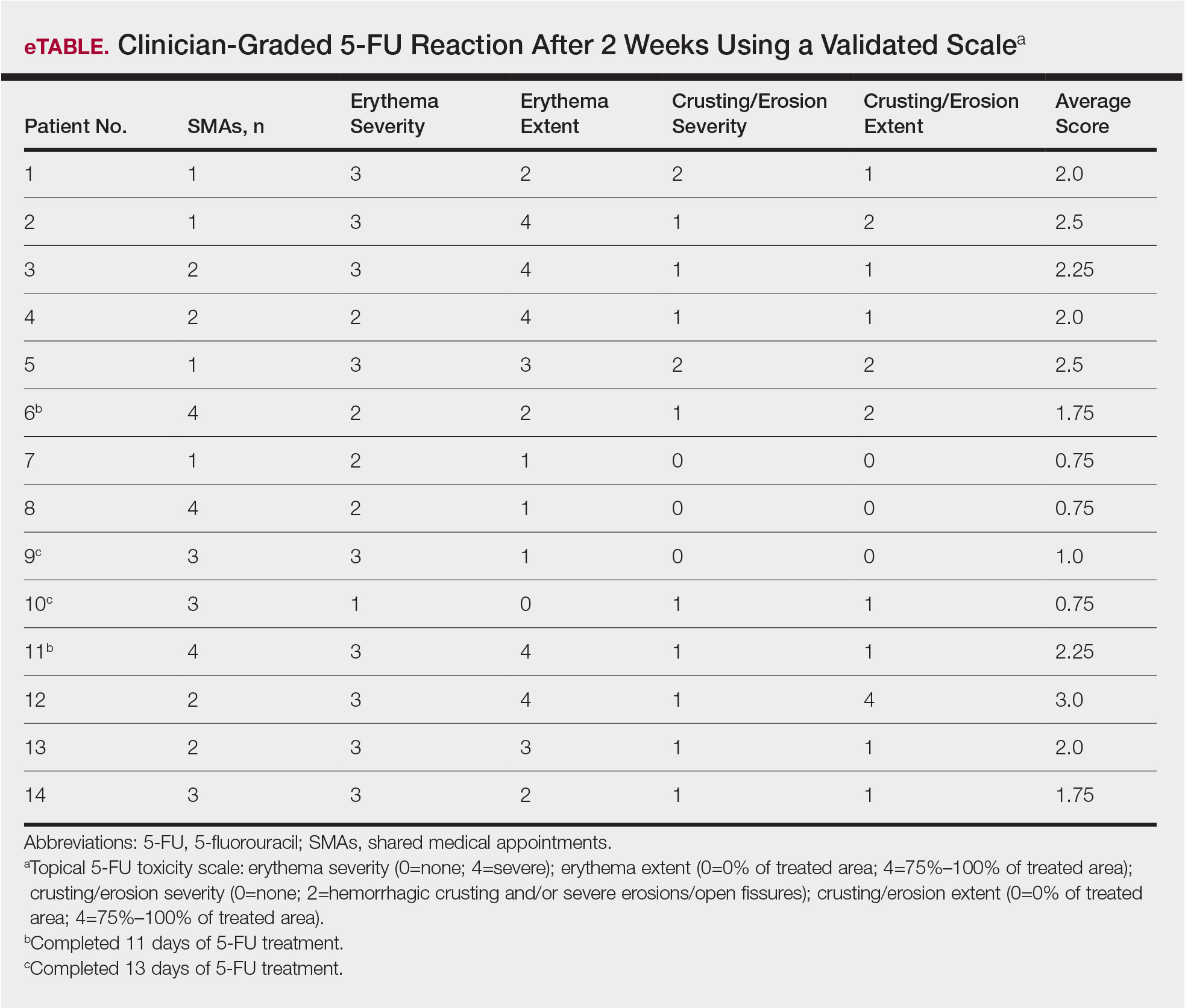

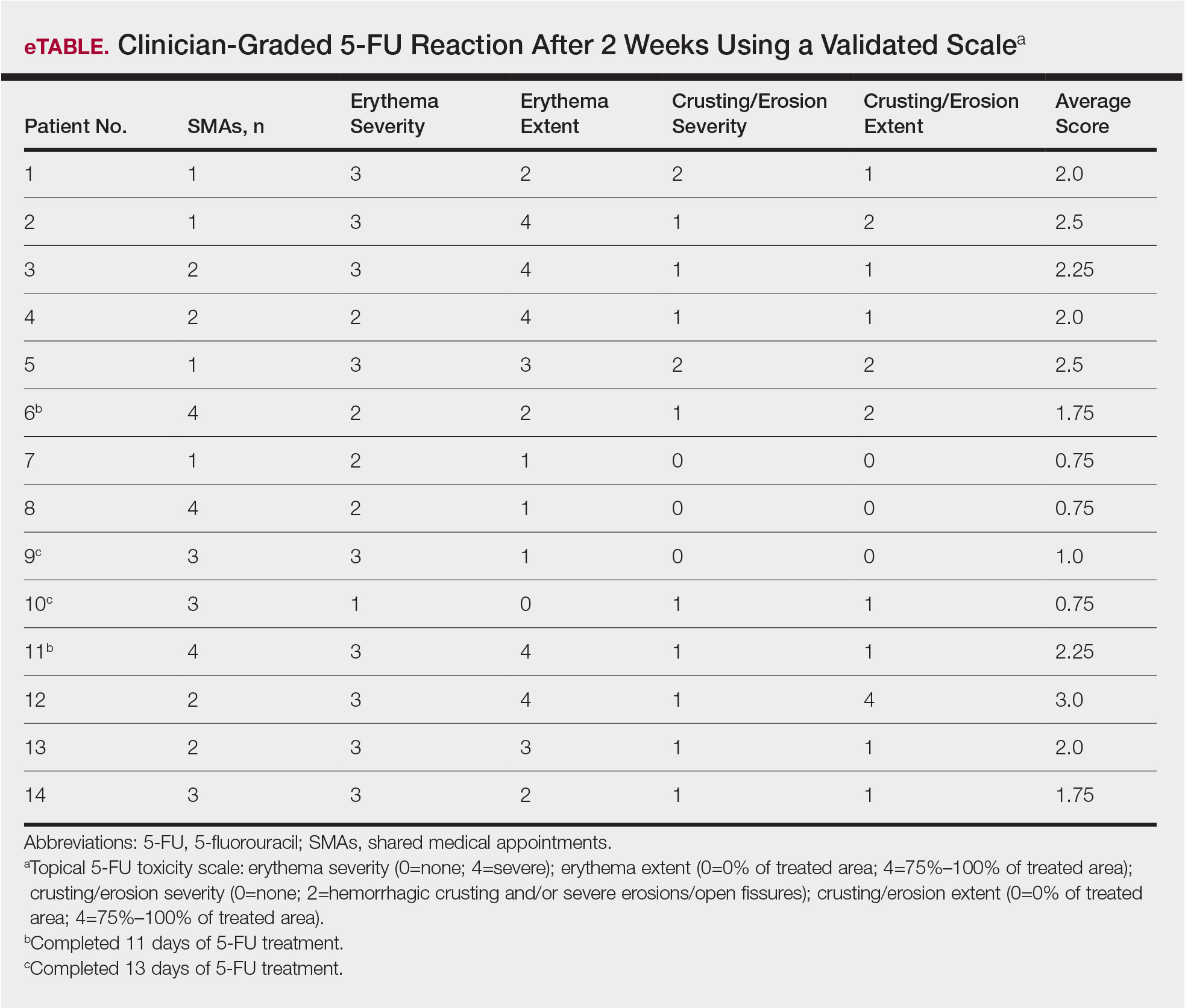

Of the 14 study patients who attended both sessions of the group clinic, 10 stated that they completed 2 weeks of 5-FU therapy, and the other 4 stated that they completed at least 11 days. Results of the validated scale used by clinicians during the second visit to grade the patients’ 5-FU reactions showed that all 14 patients demonstrated at least some expected adverse reactions (eTable). Eleven of 14 patients showed crusting and erosion; 13 showed grade 2 or higher erythema severity. One patient who stopped treatment after 11 days telephoned the dermatology clinic within 1 week of his second SMA. Another patient who stopped treatment after 11 days had a separate dermatology surgery clinic appointment within the 3-week period after starting 5-FU for a recent basal cell carcinoma excision. None of the 14 patients had a dermatology appointment scheduled within 6 months before or after for a 5-FU adverse reaction. One patient who completed the 14-day course was referred to teledermatology for insect bites within that period.

None of the patients were prophylaxed for herpes simplex virus during the treatment period, and none developed a herpes simplex virus eruption during this study. None of the patients required antibiotics for secondary impetiginization of the treatment site.

The verbal feedback about the group setting from patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers. At the conclusion of the second appointment, all of the patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors.

Comment

Shared medical appointments promote treatment adherence in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral change through group support.7-13 Within the dermatology literature, SMAs are more profitable than regular clinic appointments.15 In SMAs designed to improve patient education for preoperative consultations for Mohs micrographic surgery, patient satisfaction reported in postvisit surveys was high, with 84.7% of 149 patients reporting they found the session useful, highlighting how SMAs have potential as practical alternatives to regular medical appointments.16 Similarly, the feedback about the group setting from our patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers.

The group setting—where patients were interacting with peers undergoing the same treatment—provided an encouraging environment during the course of 5-FU therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. Additionally, at the conclusion of the second visit, patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors, further demonstrating the impact of this pilot initiative.

The Veterans Affairs’ Current Procedural Terminology code for a group clinic is 99078. Veterans Affairs medical centers and private practices have different approaches to billing and compensation. As more accountable care organizations are formed, there may be a different mixture of ways for handling these SMAs.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the small sample size, selection bias, and self-reported measure of adherence. Adherence to 5-FU is excellent without group support, and without a control group, it is unclear how beneficial the group setting was for adherence.17 The presence of the expected skin reactions at the 2-week return visit cannot account for adherence during the interval between the visits, and this close follow-up may be responsible for the high adherence in this group setting. The major side effects with 5-FU are short-term. Nonetheless, longer-term follow-up would be helpful and a worthy future endeavor.

Veterans share a common bond of military service that may not be shared in a typical private practice setting, which may have facilitated success of this pilot study. We recommend group clinics be evaluated independently in private practices and other systems. However, despite these limitations, the patients in the SMAs demonstrated positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, suggesting the potential for utilizing group clinics as a practical alternative to regular medical appointments.

Conclusion

Our pilot group clinics for AK treatment and chemoprevention of SCC with 5-FU suggest that this model is well received. The group format, which demonstrated uniformly positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, shows promise in battling an epidemic of skin cancer that demands cost-effective interventions.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Siegel JA, Korgavkar K, Weinstock MA. Current perspective on actinic keratosis: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:350-358.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

- Pomerantz H, Hogan D, Eilers D, et al. Long-term efficacy of topical fluorouracil cream, 5%, for treating actinic keratosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:952-960.

- Foley P, Stockfleth E, Peris K, et al. Adherence to topical therapies in actinic keratosis: a literature review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:538-545.

- Desouza CV, Rentschler L, Haynatzki G. The effect of group clinics in the control of diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4:251-254.

- Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, et al. Shared Medical Appointments for Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

- Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:99-106.

- Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, et al. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:995-1000.

- Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:695-700.

- Harris MD, Kirsh S, Higgins PA. Shared medical appointments: impact on clinical and quality outcomes in veterans with diabetes. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25:176-180.

- Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:349-353.

- Pomerantz H, Korgavkar K, Lee KC, et al. Validation of photograph-based toxicity score for topical 5-fluorouracil cream application. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:458-466.

- Sidorsky T, Huang Z, Dinulos JG. A business case for shared medical appointments in dermatology: improving access and the bottom line. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:374-381.

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344.

- Yentzer B, Hick J, Williams L, et al. Adherence to a topical regimen of 5-fluorouracil, 0.5%, cream for the treatment of actinic keratoses. JAMA Dermatol. 2009;145:203-205.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has an estimated incidence of more than 2.5 million cases per year in the United States.1 Its precursor lesion, actinic keratosis (AK), had an estimated prevalence of 39.5 million cases in the United States in 2004.2 The dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center in Rhode Island exerts consistent efforts to treat both SCC and AK by prescribing topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and lifestyle changes that include avoiding sun exposure, wearing protective clothing, and using effective sunscreen.3 A single course of topical 5-FU in veterans has been shown to decrease the risk for SCC by 74% during the year after treatment and also improve AK clearance rates.4,5

Effectiveness of 5-FU for secondary prevention can be decreased by patient misunderstandings, such as applying 5-FU for too short a time or using the corticosteroid cream prematurely, as well as patient nonadherence due to expected adverse skin reactions to 5-FU.6 Education and reassurance before and during therapy maximize patient compliance but can be difficult to accomplish in clinics when time is in short supply. During standard 5-FU treatment at the Providence VA Medical Center, the provider prescribes 5-FU and posttherapy corticosteroid cream at a clinic visit after an informed consent process that includes reviewing with the patient a color handout depicting the expected adverse skin reaction. Patients who later experience severe inflammation and anxiety call the clinic and are overbooked as needed.

To address the practical obstacles to the patient experience with topical 5-FU therapy, we developed a group chemoprevention clinic based on the shared medical appointment (SMA) model. Shared medical appointments, during which multiple patients are scheduled at the same visit with 1 or more health care providers, promote patient risk reduction and guideline adherence in complex diseases, such as chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus, through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral changes through group support.7-13 To increase efficiency in the group chemoprevention clinic, we integrated dermatology nurses and nurse practitioners from the chronic care model into the group medical visits, which ran from September 2016 through March 2017. Because veterans could interact with peers undergoing the same treatment, we hypothesized that use of the cream in a group setting would provide positive reinforcement during the course of therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. We conducted a retrospective review of medical records of the patients involved in this pilot study to evaluate this model.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Providence VA Medical Center. Informed consent was waived because this study was a retrospective review of medical records.

Study Population

We offered participation in a group chemoprevention clinic based on the SMA model for patients of the dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center who were planning to start 5-FU in the fall of 2016. Patients were asked if they were interested in participating in a group clinic to receive their 5-FU treatment. Patients who were established dermatology patients within the Veterans Affairs system and had scheduled annual full-body skin examinations were included; patients were not excluded if they had a prior diagnosis of AK but had not been previously treated with 5-FU.

Design

Each SMA group consisted of 3 to 4 patients who met initially to receive the 5-FU medication and attend a 10-minute live presentation that included information on the dangers and causes of SCC and AK, treatment options, directions for using 5-FU, expected spectrum of side effects, and how to minimize the discomfort of treatment side effects. Patients had field treatment limited to areas with clinically apparent AKs on the face and ears. They were prescribed 5-FU cream 5% twice daily.

One physician, one nurse practitioner, and one registered nurse were present at each 1-hour clinic. Patients arrived and were checked in individually by the providers. At check-in, the provider handed the patient a printout of his/her current medication list and a pen to make any necessary corrections. This list was reviewed privately with the patient so the provider could reconcile the medication list and review the patient’s medical history and so the patient could provide informed consent. After, the patient had the opportunity to select a seat from chairs arranged in a circle. There was a live PowerPoint presentation given at the beginning of the clinic with a question-and-answer session immediately following that contained information about the disease and medication process. Clinicians assisted the patients with the initial application of 5-FU in the large group room, and each patient received a handout with information about AKs and a 40-g tube of the 5-FU cream.

This same group then met again 2 weeks later, at which time most patients were experiencing expected adverse skin reactions. At that time, there was a 10-minute live presentation that congratulated the patients on their success in the treatment process, reviewed what to expect in the following weeks, and reinforced the importance of future sun-protective practices. At each visit, photographs and feedback about the group setting were obtained in the large group room. After photographing and rating each patient’s skin reaction severity, the clinicians advised each patient either to continue the 5-FU medication for another week or to discontinue it and apply the triamcinolone cream 0.1% up to 4 times daily as needed for up to 7 days. Each patient received the prescription corticosteroid cream and a gift, courtesy of the VA Voluntary Service Program, of a 360-degree brimmed hat and sunscreen. Time for questions or concerns was available at both sessions.

Data Collection

We reviewed medical records via the Computerized Patient Record System, a nationally accessible electronic health record system, for all patients who participated in the SMA visits from September 2016 through March 2017. Any patient who attended the initial visit but declined therapy at that time was excluded.

Outcomes included attendance at both appointments, stated completion of 14 days of 5-FU treatment, and evidence of 5-FU use according to a validated numeric scale of skin reaction severity.14 We recorded telephone calls and other dermatology clinic and teledermatology appointments during the 3 weeks after the first appointment and the number of dermatology clinic appointments 6 months before and after the SMA for side effects related to 5-FU treatment. Feedback about treatment in the group setting was obtained at both visits.

Results

A total of 16 male patients attended the SMAs, and 14 attended both sessions. Of the 2 patients who were excluded from the study, 1 declined to be scheduled for the second group appointment, and the other was scheduled and confirmed but did not come for his appointment. The mean age was 72 years.

Of the 14 study patients who attended both sessions of the group clinic, 10 stated that they completed 2 weeks of 5-FU therapy, and the other 4 stated that they completed at least 11 days. Results of the validated scale used by clinicians during the second visit to grade the patients’ 5-FU reactions showed that all 14 patients demonstrated at least some expected adverse reactions (eTable). Eleven of 14 patients showed crusting and erosion; 13 showed grade 2 or higher erythema severity. One patient who stopped treatment after 11 days telephoned the dermatology clinic within 1 week of his second SMA. Another patient who stopped treatment after 11 days had a separate dermatology surgery clinic appointment within the 3-week period after starting 5-FU for a recent basal cell carcinoma excision. None of the 14 patients had a dermatology appointment scheduled within 6 months before or after for a 5-FU adverse reaction. One patient who completed the 14-day course was referred to teledermatology for insect bites within that period.

None of the patients were prophylaxed for herpes simplex virus during the treatment period, and none developed a herpes simplex virus eruption during this study. None of the patients required antibiotics for secondary impetiginization of the treatment site.

The verbal feedback about the group setting from patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers. At the conclusion of the second appointment, all of the patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors.

Comment

Shared medical appointments promote treatment adherence in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral change through group support.7-13 Within the dermatology literature, SMAs are more profitable than regular clinic appointments.15 In SMAs designed to improve patient education for preoperative consultations for Mohs micrographic surgery, patient satisfaction reported in postvisit surveys was high, with 84.7% of 149 patients reporting they found the session useful, highlighting how SMAs have potential as practical alternatives to regular medical appointments.16 Similarly, the feedback about the group setting from our patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers.

The group setting—where patients were interacting with peers undergoing the same treatment—provided an encouraging environment during the course of 5-FU therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. Additionally, at the conclusion of the second visit, patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors, further demonstrating the impact of this pilot initiative.

The Veterans Affairs’ Current Procedural Terminology code for a group clinic is 99078. Veterans Affairs medical centers and private practices have different approaches to billing and compensation. As more accountable care organizations are formed, there may be a different mixture of ways for handling these SMAs.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the small sample size, selection bias, and self-reported measure of adherence. Adherence to 5-FU is excellent without group support, and without a control group, it is unclear how beneficial the group setting was for adherence.17 The presence of the expected skin reactions at the 2-week return visit cannot account for adherence during the interval between the visits, and this close follow-up may be responsible for the high adherence in this group setting. The major side effects with 5-FU are short-term. Nonetheless, longer-term follow-up would be helpful and a worthy future endeavor.

Veterans share a common bond of military service that may not be shared in a typical private practice setting, which may have facilitated success of this pilot study. We recommend group clinics be evaluated independently in private practices and other systems. However, despite these limitations, the patients in the SMAs demonstrated positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, suggesting the potential for utilizing group clinics as a practical alternative to regular medical appointments.

Conclusion

Our pilot group clinics for AK treatment and chemoprevention of SCC with 5-FU suggest that this model is well received. The group format, which demonstrated uniformly positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, shows promise in battling an epidemic of skin cancer that demands cost-effective interventions.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) has an estimated incidence of more than 2.5 million cases per year in the United States.1 Its precursor lesion, actinic keratosis (AK), had an estimated prevalence of 39.5 million cases in the United States in 2004.2 The dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center in Rhode Island exerts consistent efforts to treat both SCC and AK by prescribing topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and lifestyle changes that include avoiding sun exposure, wearing protective clothing, and using effective sunscreen.3 A single course of topical 5-FU in veterans has been shown to decrease the risk for SCC by 74% during the year after treatment and also improve AK clearance rates.4,5

Effectiveness of 5-FU for secondary prevention can be decreased by patient misunderstandings, such as applying 5-FU for too short a time or using the corticosteroid cream prematurely, as well as patient nonadherence due to expected adverse skin reactions to 5-FU.6 Education and reassurance before and during therapy maximize patient compliance but can be difficult to accomplish in clinics when time is in short supply. During standard 5-FU treatment at the Providence VA Medical Center, the provider prescribes 5-FU and posttherapy corticosteroid cream at a clinic visit after an informed consent process that includes reviewing with the patient a color handout depicting the expected adverse skin reaction. Patients who later experience severe inflammation and anxiety call the clinic and are overbooked as needed.

To address the practical obstacles to the patient experience with topical 5-FU therapy, we developed a group chemoprevention clinic based on the shared medical appointment (SMA) model. Shared medical appointments, during which multiple patients are scheduled at the same visit with 1 or more health care providers, promote patient risk reduction and guideline adherence in complex diseases, such as chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus, through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral changes through group support.7-13 To increase efficiency in the group chemoprevention clinic, we integrated dermatology nurses and nurse practitioners from the chronic care model into the group medical visits, which ran from September 2016 through March 2017. Because veterans could interact with peers undergoing the same treatment, we hypothesized that use of the cream in a group setting would provide positive reinforcement during the course of therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. We conducted a retrospective review of medical records of the patients involved in this pilot study to evaluate this model.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Providence VA Medical Center. Informed consent was waived because this study was a retrospective review of medical records.

Study Population

We offered participation in a group chemoprevention clinic based on the SMA model for patients of the dermatology clinic at the Providence VA Medical Center who were planning to start 5-FU in the fall of 2016. Patients were asked if they were interested in participating in a group clinic to receive their 5-FU treatment. Patients who were established dermatology patients within the Veterans Affairs system and had scheduled annual full-body skin examinations were included; patients were not excluded if they had a prior diagnosis of AK but had not been previously treated with 5-FU.

Design

Each SMA group consisted of 3 to 4 patients who met initially to receive the 5-FU medication and attend a 10-minute live presentation that included information on the dangers and causes of SCC and AK, treatment options, directions for using 5-FU, expected spectrum of side effects, and how to minimize the discomfort of treatment side effects. Patients had field treatment limited to areas with clinically apparent AKs on the face and ears. They were prescribed 5-FU cream 5% twice daily.

One physician, one nurse practitioner, and one registered nurse were present at each 1-hour clinic. Patients arrived and were checked in individually by the providers. At check-in, the provider handed the patient a printout of his/her current medication list and a pen to make any necessary corrections. This list was reviewed privately with the patient so the provider could reconcile the medication list and review the patient’s medical history and so the patient could provide informed consent. After, the patient had the opportunity to select a seat from chairs arranged in a circle. There was a live PowerPoint presentation given at the beginning of the clinic with a question-and-answer session immediately following that contained information about the disease and medication process. Clinicians assisted the patients with the initial application of 5-FU in the large group room, and each patient received a handout with information about AKs and a 40-g tube of the 5-FU cream.

This same group then met again 2 weeks later, at which time most patients were experiencing expected adverse skin reactions. At that time, there was a 10-minute live presentation that congratulated the patients on their success in the treatment process, reviewed what to expect in the following weeks, and reinforced the importance of future sun-protective practices. At each visit, photographs and feedback about the group setting were obtained in the large group room. After photographing and rating each patient’s skin reaction severity, the clinicians advised each patient either to continue the 5-FU medication for another week or to discontinue it and apply the triamcinolone cream 0.1% up to 4 times daily as needed for up to 7 days. Each patient received the prescription corticosteroid cream and a gift, courtesy of the VA Voluntary Service Program, of a 360-degree brimmed hat and sunscreen. Time for questions or concerns was available at both sessions.

Data Collection

We reviewed medical records via the Computerized Patient Record System, a nationally accessible electronic health record system, for all patients who participated in the SMA visits from September 2016 through March 2017. Any patient who attended the initial visit but declined therapy at that time was excluded.

Outcomes included attendance at both appointments, stated completion of 14 days of 5-FU treatment, and evidence of 5-FU use according to a validated numeric scale of skin reaction severity.14 We recorded telephone calls and other dermatology clinic and teledermatology appointments during the 3 weeks after the first appointment and the number of dermatology clinic appointments 6 months before and after the SMA for side effects related to 5-FU treatment. Feedback about treatment in the group setting was obtained at both visits.

Results

A total of 16 male patients attended the SMAs, and 14 attended both sessions. Of the 2 patients who were excluded from the study, 1 declined to be scheduled for the second group appointment, and the other was scheduled and confirmed but did not come for his appointment. The mean age was 72 years.

Of the 14 study patients who attended both sessions of the group clinic, 10 stated that they completed 2 weeks of 5-FU therapy, and the other 4 stated that they completed at least 11 days. Results of the validated scale used by clinicians during the second visit to grade the patients’ 5-FU reactions showed that all 14 patients demonstrated at least some expected adverse reactions (eTable). Eleven of 14 patients showed crusting and erosion; 13 showed grade 2 or higher erythema severity. One patient who stopped treatment after 11 days telephoned the dermatology clinic within 1 week of his second SMA. Another patient who stopped treatment after 11 days had a separate dermatology surgery clinic appointment within the 3-week period after starting 5-FU for a recent basal cell carcinoma excision. None of the 14 patients had a dermatology appointment scheduled within 6 months before or after for a 5-FU adverse reaction. One patient who completed the 14-day course was referred to teledermatology for insect bites within that period.

None of the patients were prophylaxed for herpes simplex virus during the treatment period, and none developed a herpes simplex virus eruption during this study. None of the patients required antibiotics for secondary impetiginization of the treatment site.

The verbal feedback about the group setting from patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers. At the conclusion of the second appointment, all of the patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors.

Comment

Shared medical appointments promote treatment adherence in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes mellitus through efficient resource use, improvement of access to care, and promotion of behavioral change through group support.7-13 Within the dermatology literature, SMAs are more profitable than regular clinic appointments.15 In SMAs designed to improve patient education for preoperative consultations for Mohs micrographic surgery, patient satisfaction reported in postvisit surveys was high, with 84.7% of 149 patients reporting they found the session useful, highlighting how SMAs have potential as practical alternatives to regular medical appointments.16 Similarly, the feedback about the group setting from our patients who completed both appointments was uniformly positive, with specific appreciation for the normalization of the treatment process and opportunity to ask questions with their peers.

The group setting—where patients were interacting with peers undergoing the same treatment—provided an encouraging environment during the course of 5-FU therapy, resulting in a positive treatment experience. Additionally, at the conclusion of the second visit, patients reported an increased understanding of their condition and the importance of future sun-protective behaviors, further demonstrating the impact of this pilot initiative.

The Veterans Affairs’ Current Procedural Terminology code for a group clinic is 99078. Veterans Affairs medical centers and private practices have different approaches to billing and compensation. As more accountable care organizations are formed, there may be a different mixture of ways for handling these SMAs.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the small sample size, selection bias, and self-reported measure of adherence. Adherence to 5-FU is excellent without group support, and without a control group, it is unclear how beneficial the group setting was for adherence.17 The presence of the expected skin reactions at the 2-week return visit cannot account for adherence during the interval between the visits, and this close follow-up may be responsible for the high adherence in this group setting. The major side effects with 5-FU are short-term. Nonetheless, longer-term follow-up would be helpful and a worthy future endeavor.

Veterans share a common bond of military service that may not be shared in a typical private practice setting, which may have facilitated success of this pilot study. We recommend group clinics be evaluated independently in private practices and other systems. However, despite these limitations, the patients in the SMAs demonstrated positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, suggesting the potential for utilizing group clinics as a practical alternative to regular medical appointments.

Conclusion

Our pilot group clinics for AK treatment and chemoprevention of SCC with 5-FU suggest that this model is well received. The group format, which demonstrated uniformly positive reactions to 5-FU therapy, shows promise in battling an epidemic of skin cancer that demands cost-effective interventions.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Siegel JA, Korgavkar K, Weinstock MA. Current perspective on actinic keratosis: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:350-358.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

- Pomerantz H, Hogan D, Eilers D, et al. Long-term efficacy of topical fluorouracil cream, 5%, for treating actinic keratosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:952-960.

- Foley P, Stockfleth E, Peris K, et al. Adherence to topical therapies in actinic keratosis: a literature review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:538-545.

- Desouza CV, Rentschler L, Haynatzki G. The effect of group clinics in the control of diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4:251-254.

- Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, et al. Shared Medical Appointments for Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

- Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:99-106.

- Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, et al. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:995-1000.

- Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:695-700.

- Harris MD, Kirsh S, Higgins PA. Shared medical appointments: impact on clinical and quality outcomes in veterans with diabetes. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25:176-180.

- Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:349-353.

- Pomerantz H, Korgavkar K, Lee KC, et al. Validation of photograph-based toxicity score for topical 5-fluorouracil cream application. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:458-466.

- Sidorsky T, Huang Z, Dinulos JG. A business case for shared medical appointments in dermatology: improving access and the bottom line. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:374-381.

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344.

- Yentzer B, Hick J, Williams L, et al. Adherence to a topical regimen of 5-fluorouracil, 0.5%, cream for the treatment of actinic keratoses. JAMA Dermatol. 2009;145:203-205.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the U.S. population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:490-500.

- Siegel JA, Korgavkar K, Weinstock MA. Current perspective on actinic keratosis: a review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:350-358.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

- Pomerantz H, Hogan D, Eilers D, et al. Long-term efficacy of topical fluorouracil cream, 5%, for treating actinic keratosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:952-960.

- Foley P, Stockfleth E, Peris K, et al. Adherence to topical therapies in actinic keratosis: a literature review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27:538-545.

- Desouza CV, Rentschler L, Haynatzki G. The effect of group clinics in the control of diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4:251-254.

- Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, et al. Shared Medical Appointments for Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

- Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:99-106.

- Trento M, Passera P, Tomalino M, et al. Group visits improve metabolic control in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:995-1000.

- Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:695-700.

- Harris MD, Kirsh S, Higgins PA. Shared medical appointments: impact on clinical and quality outcomes in veterans with diabetes. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25:176-180.

- Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:349-353.

- Pomerantz H, Korgavkar K, Lee KC, et al. Validation of photograph-based toxicity score for topical 5-fluorouracil cream application. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:458-466.

- Sidorsky T, Huang Z, Dinulos JG. A business case for shared medical appointments in dermatology: improving access and the bottom line. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:374-381.

- Knackstedt TJ, Samie FH. Shared medical appointments for the preoperative consultation visit of Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:340-344.

- Yentzer B, Hick J, Williams L, et al. Adherence to a topical regimen of 5-fluorouracil, 0.5%, cream for the treatment of actinic keratoses. JAMA Dermatol. 2009;145:203-205.

Practice Points

- Shared medical appointments (SMAs) enhance patient experience with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment of actinic keratosis (AK).

- Dermatologists should consider utilizing the SMA model for their patients being treated with 5-FU, as patients demonstrated a positive emotional response to 5-FU therapy in the group clinic setting.

COVID-19 death rate was twice as high in cancer patients in NYC study

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

COVID-19 patients with cancer had double the fatality rate of COVID-19 patients without cancer treated in an urban New York hospital system, according to data from a retrospective study.

with COVID-19 treated during the same time period in the same hospital system.

Vikas Mehta, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and colleagues reported these results in Cancer Discovery.

“As New York has emerged as the current epicenter of the pandemic, we sought to investigate the risk posed by COVID-19 to our cancer population,” the authors wrote.

They identified 218 cancer patients treated for COVID-19 in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020. Three-quarters of patients had solid tumors, and 25% had hematologic malignancies. Most patients were adults (98.6%), their median age was 69 years (range, 10-92 years), and 58% were men.

In all, 28% of the cancer patients (61/218) died from COVID-19, including 25% (41/164) of those with solid tumors and 37% (20/54) of those with hematologic malignancies.

Deaths by cancer type

Among the 164 patients with solid tumors, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Pancreatic – 67% (2/3)

- Lung – 55% (6/11)

- Colorectal – 38% (8/21)

- Upper gastrointestinal – 38% (3/8)

- Gynecologic – 38% (5/13)

- Skin – 33% (1/3)

- Hepatobiliary – 29% (2/7)

- Bone/soft tissue – 20% (1/5)

- Genitourinary – 15% (7/46)

- Breast – 14% (4/28)

- Neurologic – 13% (1/8)

- Head and neck – 13% (1/8).

None of the three patients with neuroendocrine tumors died.

Among the 54 patients with hematologic malignancies, case fatality rates were as follows:

- Chronic myeloid leukemia – 100% (1/1)

- Hodgkin lymphoma – 60% (3/5)

- Myelodysplastic syndromes – 60% (3/5)

- Multiple myeloma – 38% (5/13)

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma – 33% (5/15)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia – 33% (1/3)

- Myeloproliferative neoplasms – 29% (2/7).

None of the four patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia died, and there was one patient with acute myeloid leukemia who did not die.

Factors associated with increased mortality

The researchers compared the 218 cancer patients with COVID-19 with 1,090 age- and sex-matched noncancer patients with COVID-19 treated in the Montefiore Health System between March 18 and April 8, 2020.

Case fatality rates in cancer patients with COVID-19 were significantly increased in all age groups, but older age was associated with higher mortality.

“We observed case fatality rates were elevated in all age cohorts in cancer patients and achieved statistical significance in the age groups 45-64 and in patients older than 75 years of age,” the authors reported.

Other factors significantly associated with higher mortality in a multivariable analysis included the presence of multiple comorbidities; the need for ICU support; and increased levels of d-dimer, lactate, and lactate dehydrogenase.

Additional factors, such as socioeconomic and health disparities, may also be significant predictors of mortality, according to the authors. They noted that this cohort largely consisted of patients from a socioeconomically underprivileged community where mortality because of COVID-19 is reportedly higher.

Proactive strategies moving forward

“We have been addressing the significant burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on our vulnerable cancer patients through a variety of ways,” said study author Balazs Halmos, MD, of Montefiore Medical Center.

The center set up a separate infusion unit exclusively for COVID-positive patients and established separate inpatient areas. Dr. Halmos and colleagues are also providing telemedicine, virtual supportive care services, telephonic counseling, and bilingual peer-support programs.

“Many questions remain as we continue to establish new practices for our cancer patients,” Dr. Halmos said. “We will find answers to these questions as we continue to focus on adaptation and not acceptance in response to the COVID crisis. Our patients deserve nothing less.”

The Albert Einstein Cancer Center supported this study. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mehta V et al. Cancer Discov. 2020 May 1. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0516.

FROM CANCER DISCOVERY

Excess cancer deaths predicted as care is disrupted by COVID-19

The majority of patients who have cancer or are suspected of having cancer are not accessing healthcare services in the United Kingdom or the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first report of its kind estimates.

As a result, there will be an excess of deaths among patients who have cancer and multiple comorbidities in both countries during the current coronavirus emergency, the report warns.

The authors calculate that there will be 6,270 excess deaths among cancer patients 1 year from now in England and 33,890 excess deaths among cancer patients in the United States. (In the United States, the estimated excess number of deaths applies only to patients older than 40 years, they note.)

“The recorded underlying cause of these excess deaths may be cancer, COVID-19, or comorbidity (such as myocardial infarction),” Alvina Lai, PhD, University College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues observe.

“Our data have highlighted how cancer patients with multimorbidity are a particularly at-risk group during the current pandemic,” they emphasize.

The study was published on ResearchGate as a preprint and has not undergone peer review.

Commenting on the study on the UK Science Media Center, several experts emphasized the lack of peer review, noting that interpretation of these data needs to be further refined on the basis of that input. One expert suggested that there are “substantial uncertainties that this paper does not adequately communicate.” But others argued that this topic was important enough to warrant early release of the data.

Chris Bunce, PhD, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, said this study represents “a highly valuable contribution.”

“It is universally accepted that early diagnosis and treatment and adherence to treatment regimens saves lives,” he pointed out.

“Therefore, these COVID-19-related impacts will cost lives,” Bunce said.

“And if this information is to influence cancer care and guide policy during the COVID-19 crisis, then it is important that the findings are disseminated and discussed immediately, warranting their release ahead of peer view,” he added.

In a Medscape UK commentary, oncologist Karol Sikora, MD, PhD, argues that “restarting cancer services can’t come soon enough.”

“Resonably Argued Numerical Estimate”

“It’s well known that there have been considerable changes in the provision of health care for many conditions, including cancers, as a result of all the measures to deal with the COVID-19 crisis,” said Kevin McConway, PhD, professor emeritus of applied statistics, the Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom.

“It seems inevitable that there will be increased deaths in cancer patients if they are infected with the virus or because of changes in the health services available to them, and quite possibly also from socio-economic effects of the responses to the crisis,” he continued.

“This study is the first that I have seen that produces a reasonably argued numerical estimate of the number of excess deaths of people with cancer arising from these factors in the UK and the USA,” he added.

Declines in Urgent Referrals and Chemo Attendance

For the study, the team used DATA-CAN, the UK National Health Data Research Hub for Cancer, to assess weekly returns for urgent cancer referrals for early diagnosis and also chemotherapy attendances for hospitals in Leeds, London, and Northern Ireland going back to 2018.

The data revealed that there have been major declines in chemotherapy attendances. There has been, on average, a 60% decrease from prepandemic levels in eight hospitals in the three regions that were assessed.

Urgent cancer referrals have dropped by an average of 76% compared to prepandemic levels in the three regions.

On the conservative assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic will only affect patients with newly diagnosed cancer (incident cases), the researchers estimate that the proportion of the population affected by the emergency (PAE) is 40% and that the relative impact of the emergency (RIE) is 1.5.

PAE is a summary measure of exposure to the adverse health consequences of the emergency; RIE is a summary measure of the combined impact on mortality of infection, health service change, physical distancing, and economic downturn, the authors explain.

Comorbidities Common

“Comorbidities were common in people with cancer,” the study authors note. For example, more than one quarter of the study population had at least one comorbidity; more than 14% had two.

For incident cancers, the number of excess deaths steadily increased in conjunction with an increase in the number of comorbidities, such that more than 80% of deaths occurred in patients with one or more comorbidities.

“When considering both prevalent and incident cancers together with a COVID-19 PAE of 40%, we estimated 17,991 excess deaths at a RIE of 1.5; 78.1% of these deaths occur in patients with ≥1 comorbidities,” the authors report.

“The excess risk of death in people living with cancer during the COVID-19 emergency may be due not only to COVID-19 infection, but also to the unintended health consequences of changes in health service provision, the physical or psychological effects of social distancing, and economic upheaval,” they state.

“This is the first study demonstrating profound recent changes in cancer care delivery in multiple centers,” the authors observe.

Lai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have various relationships with industry, as listed in their article. The commentators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The majority of patients who have cancer or are suspected of having cancer are not accessing healthcare services in the United Kingdom or the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first report of its kind estimates.

As a result, there will be an excess of deaths among patients who have cancer and multiple comorbidities in both countries during the current coronavirus emergency, the report warns.

The authors calculate that there will be 6,270 excess deaths among cancer patients 1 year from now in England and 33,890 excess deaths among cancer patients in the United States. (In the United States, the estimated excess number of deaths applies only to patients older than 40 years, they note.)

“The recorded underlying cause of these excess deaths may be cancer, COVID-19, or comorbidity (such as myocardial infarction),” Alvina Lai, PhD, University College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues observe.

“Our data have highlighted how cancer patients with multimorbidity are a particularly at-risk group during the current pandemic,” they emphasize.

The study was published on ResearchGate as a preprint and has not undergone peer review.

Commenting on the study on the UK Science Media Center, several experts emphasized the lack of peer review, noting that interpretation of these data needs to be further refined on the basis of that input. One expert suggested that there are “substantial uncertainties that this paper does not adequately communicate.” But others argued that this topic was important enough to warrant early release of the data.

Chris Bunce, PhD, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, said this study represents “a highly valuable contribution.”

“It is universally accepted that early diagnosis and treatment and adherence to treatment regimens saves lives,” he pointed out.

“Therefore, these COVID-19-related impacts will cost lives,” Bunce said.

“And if this information is to influence cancer care and guide policy during the COVID-19 crisis, then it is important that the findings are disseminated and discussed immediately, warranting their release ahead of peer view,” he added.

In a Medscape UK commentary, oncologist Karol Sikora, MD, PhD, argues that “restarting cancer services can’t come soon enough.”

“Resonably Argued Numerical Estimate”

“It’s well known that there have been considerable changes in the provision of health care for many conditions, including cancers, as a result of all the measures to deal with the COVID-19 crisis,” said Kevin McConway, PhD, professor emeritus of applied statistics, the Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom.

“It seems inevitable that there will be increased deaths in cancer patients if they are infected with the virus or because of changes in the health services available to them, and quite possibly also from socio-economic effects of the responses to the crisis,” he continued.

“This study is the first that I have seen that produces a reasonably argued numerical estimate of the number of excess deaths of people with cancer arising from these factors in the UK and the USA,” he added.

Declines in Urgent Referrals and Chemo Attendance

For the study, the team used DATA-CAN, the UK National Health Data Research Hub for Cancer, to assess weekly returns for urgent cancer referrals for early diagnosis and also chemotherapy attendances for hospitals in Leeds, London, and Northern Ireland going back to 2018.

The data revealed that there have been major declines in chemotherapy attendances. There has been, on average, a 60% decrease from prepandemic levels in eight hospitals in the three regions that were assessed.

Urgent cancer referrals have dropped by an average of 76% compared to prepandemic levels in the three regions.

On the conservative assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic will only affect patients with newly diagnosed cancer (incident cases), the researchers estimate that the proportion of the population affected by the emergency (PAE) is 40% and that the relative impact of the emergency (RIE) is 1.5.

PAE is a summary measure of exposure to the adverse health consequences of the emergency; RIE is a summary measure of the combined impact on mortality of infection, health service change, physical distancing, and economic downturn, the authors explain.

Comorbidities Common

“Comorbidities were common in people with cancer,” the study authors note. For example, more than one quarter of the study population had at least one comorbidity; more than 14% had two.

For incident cancers, the number of excess deaths steadily increased in conjunction with an increase in the number of comorbidities, such that more than 80% of deaths occurred in patients with one or more comorbidities.

“When considering both prevalent and incident cancers together with a COVID-19 PAE of 40%, we estimated 17,991 excess deaths at a RIE of 1.5; 78.1% of these deaths occur in patients with ≥1 comorbidities,” the authors report.

“The excess risk of death in people living with cancer during the COVID-19 emergency may be due not only to COVID-19 infection, but also to the unintended health consequences of changes in health service provision, the physical or psychological effects of social distancing, and economic upheaval,” they state.

“This is the first study demonstrating profound recent changes in cancer care delivery in multiple centers,” the authors observe.

Lai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have various relationships with industry, as listed in their article. The commentators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The majority of patients who have cancer or are suspected of having cancer are not accessing healthcare services in the United Kingdom or the United States because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first report of its kind estimates.

As a result, there will be an excess of deaths among patients who have cancer and multiple comorbidities in both countries during the current coronavirus emergency, the report warns.

The authors calculate that there will be 6,270 excess deaths among cancer patients 1 year from now in England and 33,890 excess deaths among cancer patients in the United States. (In the United States, the estimated excess number of deaths applies only to patients older than 40 years, they note.)

“The recorded underlying cause of these excess deaths may be cancer, COVID-19, or comorbidity (such as myocardial infarction),” Alvina Lai, PhD, University College London, United Kingdom, and colleagues observe.

“Our data have highlighted how cancer patients with multimorbidity are a particularly at-risk group during the current pandemic,” they emphasize.

The study was published on ResearchGate as a preprint and has not undergone peer review.

Commenting on the study on the UK Science Media Center, several experts emphasized the lack of peer review, noting that interpretation of these data needs to be further refined on the basis of that input. One expert suggested that there are “substantial uncertainties that this paper does not adequately communicate.” But others argued that this topic was important enough to warrant early release of the data.

Chris Bunce, PhD, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, said this study represents “a highly valuable contribution.”

“It is universally accepted that early diagnosis and treatment and adherence to treatment regimens saves lives,” he pointed out.

“Therefore, these COVID-19-related impacts will cost lives,” Bunce said.

“And if this information is to influence cancer care and guide policy during the COVID-19 crisis, then it is important that the findings are disseminated and discussed immediately, warranting their release ahead of peer view,” he added.

In a Medscape UK commentary, oncologist Karol Sikora, MD, PhD, argues that “restarting cancer services can’t come soon enough.”

“Resonably Argued Numerical Estimate”

“It’s well known that there have been considerable changes in the provision of health care for many conditions, including cancers, as a result of all the measures to deal with the COVID-19 crisis,” said Kevin McConway, PhD, professor emeritus of applied statistics, the Open University, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom.

“It seems inevitable that there will be increased deaths in cancer patients if they are infected with the virus or because of changes in the health services available to them, and quite possibly also from socio-economic effects of the responses to the crisis,” he continued.

“This study is the first that I have seen that produces a reasonably argued numerical estimate of the number of excess deaths of people with cancer arising from these factors in the UK and the USA,” he added.

Declines in Urgent Referrals and Chemo Attendance

For the study, the team used DATA-CAN, the UK National Health Data Research Hub for Cancer, to assess weekly returns for urgent cancer referrals for early diagnosis and also chemotherapy attendances for hospitals in Leeds, London, and Northern Ireland going back to 2018.

The data revealed that there have been major declines in chemotherapy attendances. There has been, on average, a 60% decrease from prepandemic levels in eight hospitals in the three regions that were assessed.

Urgent cancer referrals have dropped by an average of 76% compared to prepandemic levels in the three regions.

On the conservative assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic will only affect patients with newly diagnosed cancer (incident cases), the researchers estimate that the proportion of the population affected by the emergency (PAE) is 40% and that the relative impact of the emergency (RIE) is 1.5.

PAE is a summary measure of exposure to the adverse health consequences of the emergency; RIE is a summary measure of the combined impact on mortality of infection, health service change, physical distancing, and economic downturn, the authors explain.

Comorbidities Common

“Comorbidities were common in people with cancer,” the study authors note. For example, more than one quarter of the study population had at least one comorbidity; more than 14% had two.

For incident cancers, the number of excess deaths steadily increased in conjunction with an increase in the number of comorbidities, such that more than 80% of deaths occurred in patients with one or more comorbidities.

“When considering both prevalent and incident cancers together with a COVID-19 PAE of 40%, we estimated 17,991 excess deaths at a RIE of 1.5; 78.1% of these deaths occur in patients with ≥1 comorbidities,” the authors report.

“The excess risk of death in people living with cancer during the COVID-19 emergency may be due not only to COVID-19 infection, but also to the unintended health consequences of changes in health service provision, the physical or psychological effects of social distancing, and economic upheaval,” they state.

“This is the first study demonstrating profound recent changes in cancer care delivery in multiple centers,” the authors observe.

Lai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have various relationships with industry, as listed in their article. The commentators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

ASCO panel outlines cancer care challenges during COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to exact a heavy price on cancer patients, cancer care, and clinical trials, an expert panel reported during a presscast.

“Limited data available thus far are sobering: In Italy, about 20% of COVID-related deaths occurred in people with cancer, and, in China, COVID-19 patients who had cancer were about five times more likely than others to die or be placed on a ventilator in an intensive care unit,” said Howard A “Skip” Burris, MD, president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and president and CEO of the Sarah Cannon Cancer Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

“We also have little evidence on returning COVID-19 patients with cancer. Physicians have to rely on limited data, anecdotal reports, and their own professional expertise” regarding the extent of increased risk to cancer patients with COVID-19, whether to interrupt or modify treatment, and the effects of cancer on recovery from COVID-19 infection, Dr. Burris said during the ASCO-sponsored online presscast.

Care of COVID-free patients

For cancer patients without COVID-19, the picture is equally dim, with the prospect of delayed surgery, chemotherapy, or screening; shortages of medications and equipment needed for critical care; the shift to telemedicine that may increase patient anxiety; and the potential loss of access to innovative therapies through clinical trials, Dr. Burris said.

“We’re concerned that some hospitals have effectively deemed all cancer surgeries to be elective, requiring them to be postponed. For patients with fast-moving or hard-to-treat cancer, this delay may be devastating,” he said.

Dr. Burris also cited concerns about delayed cancer diagnosis. “In a typical month, roughly 150,000 Americans are diagnosed with cancer. But right now, routine screening visits are postponed, and patients with pain or other warning signs may put off a doctor’s visit because of social distancing,” he said.

The pandemic has also exacerbated shortages of sedatives and opioid analgesics required for intubation and mechanical ventilation of patients.

Trials halted or slowed

Dr. Burris also briefly discussed results of a new survey, which were posted online ahead of publication in JCO Oncology Practice. The survey showed that, of 14 academic and 18 community-based cancer programs, 59.4% reported halting screening and/or enrollment for at least some clinical trials and suspending research-based clinical visits except for those where cancer treatment was delivered.

“Half of respondents reported ceasing research-only blood and/or tissue collections,” the authors of the article reported.

“Trial interruptions are devastating news for thousands of patients; in many cases, clinical trials are the best or only appropriate option for care,” Dr. Burris said.

The article authors, led by David Waterhouse, MD, of Oncology Hematology Care in Cincinnati, pointed to a silver lining in the pandemic cloud in the form of opportunities to improve clinical trials going forward.