User login

What does it mean to be a trustworthy male ally?

“If you want to be trusted, be trustworthy” – Stephen Covey

A few years ago, while working in my office, a female colleague stopped by for a casual chat. During the course of the conversation, she noticed that I did not have any diplomas or certificates hanging on my office walls. Instead, there were clusters of pictures drawn by my children, family photos, and a white board with my “to-do” list. The only wall art was a print of Banksy’s “The Thinker Monkey,” which depicts a monkey with its fist to its chin similar to Rodin’s famous sculpture, “Le Penseur.”

When asked why I didn’t hang any diplomas or awards, I replied that I preferred to keep my office atmosphere light and fun, and to focus on future goals rather than past accomplishments. I could see her jaw tense. Her frustration appeared deep, but it was for reasons beyond just my self-righteous tone. She said, “You know, I appreciate your focus on future goals, but it’s a pretty privileged position to not have to worry about sharing your accomplishments publicly.”

What followed was a discussion that was generative, enlightening, uncomfortable, and necessary. I had never considered what I chose to hang (or not hang) on my office walls as a privilege, and that was exactly the point. She described numerous episodes when her accomplishments were overlooked or (worse) attributed to a male colleague because she was a woman. I began to understand that graceful self-promotion is not optional for many women in medicine, it is a necessary skill.

This is just one example of how my privilege as a male in medicine contributed to my ignorance of the gender inequities that my female coworkers have faced throughout their careers. My colleague showed a lot of grace by taking the time to help me navigate my male privilege in a constructive manner. I decided to learn more about gender inequities, and eventually determined that I was woefully inadequate as a male ally, not by refusal but by ignorance. I wanted to start earning my colleague’s trust that I would be an ally that she could count on.

Trustworthiness

I wanted to be a trustworthy ally, but what does that entail? Perhaps we can learn from medical education. Trust is a complex construct that is increasingly used as a framework for assessing medical students and residents, such as with entrustable professional activities (EPAs).1,2 Multiple studies have examined the characteristics that make a learner “trustworthy” when determining how much supervision is required.3-8 Ten Cate and Chen performed an interpretivist, narrative review to synthesize the medical education literature on learner trustworthiness in the past 15 years,9 developing five major themes that contribute to trustworthiness: Humility, Capability, Agency, Reliability, and Integrity. Let’s examine each of these through the lens of male allyship.

Humility

Humility involves knowing one’s limits, asking for help, and being receptive to feedback.9 The first thing men need to do is to put their egos in check and recognize that women do not need rescuing; they need partnership. Systemic inequities have led to men holding the majority of leadership positions and significant sociopolitical capital, and correcting these inequities is more feasible when those in leadership and positions of power contribute. Women don’t need knights in shining armor, they need collaborative activism.

Humility also means a willingness to admit fallibility and to ask for help. Men often don’t know what they don’t know (see my foibles in the opening). As David G. Smith, PhD, and W. Brad Johnson, PhD, write in their book, “Good Guys,” “There are no perfect allies. As you work to become a better ally for the women around you, you will undoubtedly make a mistake.”10 Men must accept feedback on their shortcomings as allies without feeling as though they are losing their sociopolitical standing. Allyship for women does not mean there is a devaluing of men. We must escape a “zero-sum” mindset. Mistakes are where growth happens, but only if we approach our missteps with humility.

Capability

Capability entails having the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be a strong ally. Allyship is not intuitive for most men for several reasons. Many men do not experience the same biases or systemic inequities that women do, and therefore perceive them less frequently. I want to acknowledge that men can be victims of other systemic biases such as those against one’s race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or any number of factors. Men who face inequities for these other reasons may be more cognizant of the biases women face. Even so, allyship is a skill that few men have been explicitly taught. Even if taught, few standard or organized mechanisms for feedback on allyship capability exist. How, then, can men become capable allies?

Just like in medical education, men must become self-directed learners who seek to build capability and receive feedback on their performance as allies. Men should seek allyship training through local women-in-medicine programs or organizations, or through the increasing number of national education options such as the recent ADVANCE PHM Gender Equity Symposium. As with learning any skill, men should go to the literature, seeking knowledge from experts in the field. I recommend starting with “Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace10 or “Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women.”11 Both books, by Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson, are great entry points into the gender allyship literature. Seek out other resources from local experts on gender equity and allyship. Both aforementioned books were recommended to me by a friend and gender equity expert; without her guidance I would not have known where to start.

Agency

Agency involves being proactive and engaged rather than passive or apathetic. Men must be enthusiastic allies who seek out opportunities to mentor and sponsor women rather than waiting for others to ask. Agency requires being curious and passionate about improving. Most men in medicine are not openly and explicitly misogynistic or sexist, but many are only passive when it comes to gender equity and allyship. Trustworthy allyship entails turning passive support into active change. Not sure how to start? A good first step is to ask female colleagues questions such as, “What can I do to be a better ally for you in the workplace?” or “What are some things at work that are most challenging to you, but I might not notice because I’m a man?” Curiosity is the springboard toward agency.

Reliability

Reliability means being conscientious, accountable, and doing what we say we will do. Nothing undermines trustworthiness faster than making a commitment and not following through. Allyship cannot be a show or an attempt to get public plaudits. It is a longitudinal commitment to supporting women through individual mentorship and sponsorship, and to work toward institutional and systems change.

Reliability also means taking an equitable approach to what Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson call “office housework.” They define this as “administrative work that is necessary but undervalued, unlikely to lead to promotion, and disproportionately assigned to women.”10 In medicine, these tasks include organizing meetings, taking notes, planning social events, and remembering to celebrate colleagues’ achievements and milestones. Men should take on more of these tasks and advocate for change when the distribution of office housework in their workplace is inequitably directed toward women.

Integrity

Integrity involves honesty, professionalism, and benevolence. It is about making the morally correct choice even if there is potential risk. When men see gender inequity, they have an obligation to speak up. Whether it is overtly misogynistic behavior, subtle sexism, use of gendered language, inequitable distribution of office housework, lack of inclusivity and recognition for women, or another form of inequity, men must act with integrity and make it clear that they are partnering with women for change. Integrity means being an ally even when women are not present, and advocating that women be “at the table” for important conversations.

Beyond the individual

Allyship cannot end with individual actions; systems changes that build trustworthy institutions are necessary. Organizational leaders must approach gender conversations with humility to critically examine inequities and agency to implement meaningful changes. Workplace cultures and institutional policies should be reviewed with an eye toward system-level integrity and reliability for promoting and supporting women. Ongoing faculty and staff development programs must provide men with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (capability) to be strong allies. We have a long history of male-dominated institutions that are unfair or (worse) unsafe for women. Many systems are designed in a way that disadvantages women. These systems must be redesigned through an equity lens to start building trust with women in medicine.

Becoming trustworthy is a process

Even the best male allies have room to improve their trustworthiness. Many men (myself included) have a LOT of room to improve, but they should not get discouraged by the amount of ground to be gained. Steady, deliberate improvement in men’s humility, capability, agency, reliability, and integrity can build the foundation of trust with female colleagues. Trust takes time. It takes effort. It takes vulnerability. It is an ongoing, developmental process that requires deliberate practice, frequent reflection, and feedback from our female colleagues.

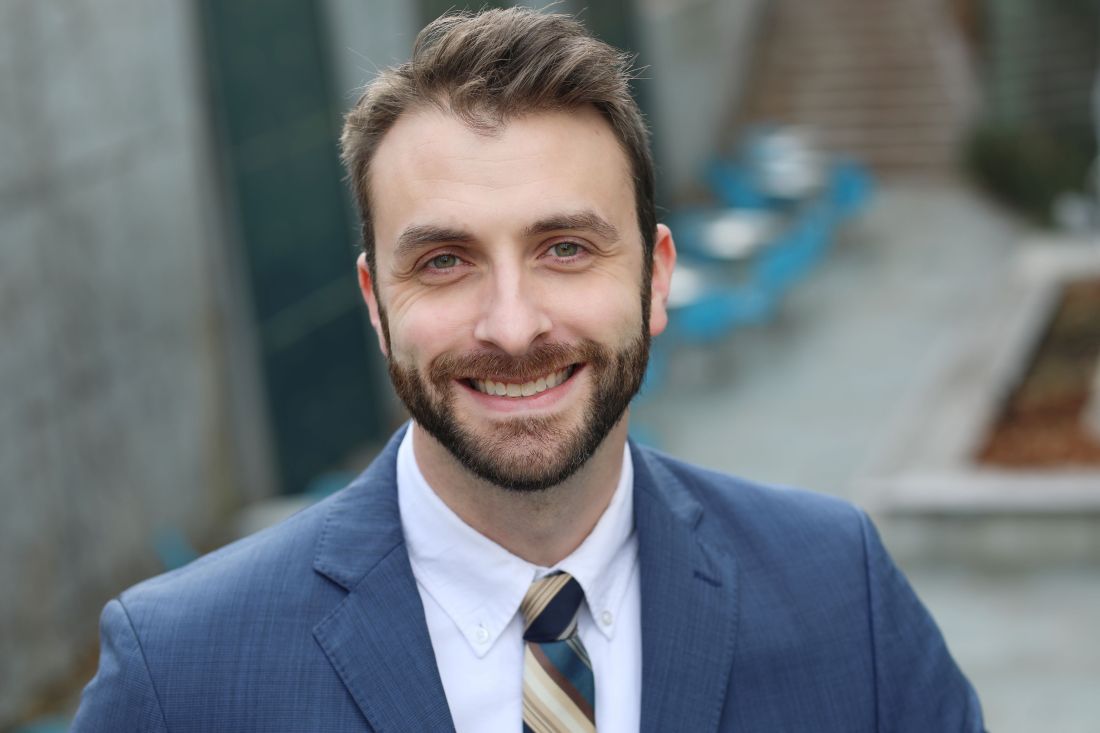

Dr. Kinnear is associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati Medical Center. He is associate program director for the Med-Peds and Internal Medicine residency programs.

References

1. Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013 Mar;5(1):157-8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1.

2. Ten Cate O. Entrustment decisions: Bringing the patient into the assessment equation. Acad Med. 2017 Jun;92(6):736-8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001623.

3. Kennedy TJT et al. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008 Oct;83(10 Suppl):S89-92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7.

4. Choo KJ et al. How do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014 Mar;9(3):169-75. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2150.

5. Hauer KE et al. How clinical supervisors develop trust in their trainees: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2015 Aug;49(8):783-95. doi: 10.1111/medu.12745.

6. Sterkenburg A et al. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1408-17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab0ec.

7. Sheu L et al. How supervisor experience influences trust, supervision, and trainee learning: A qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017 Sep;92(9):1320-7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001560.

8. Pingree EW et al. Encouraging entrustment: A qualitative study of resident behaviors that promote entrustment. Acad Med. 2020 Nov;95(11):1718-25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003487.

9. Ten Cate O, Chen HC. The ingredients of a rich entrustment decision. Med Teach. 2020 Dec;42(12):1413-20. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1817348.

10. Smith DG, Johnson WB. Good guys: How men can be better allies for women in the workplace: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation 2020.

11. Johnson WB, Smith D. Athena rising: How and why men should mentor women: Routledge 2016.

“If you want to be trusted, be trustworthy” – Stephen Covey

A few years ago, while working in my office, a female colleague stopped by for a casual chat. During the course of the conversation, she noticed that I did not have any diplomas or certificates hanging on my office walls. Instead, there were clusters of pictures drawn by my children, family photos, and a white board with my “to-do” list. The only wall art was a print of Banksy’s “The Thinker Monkey,” which depicts a monkey with its fist to its chin similar to Rodin’s famous sculpture, “Le Penseur.”

When asked why I didn’t hang any diplomas or awards, I replied that I preferred to keep my office atmosphere light and fun, and to focus on future goals rather than past accomplishments. I could see her jaw tense. Her frustration appeared deep, but it was for reasons beyond just my self-righteous tone. She said, “You know, I appreciate your focus on future goals, but it’s a pretty privileged position to not have to worry about sharing your accomplishments publicly.”

What followed was a discussion that was generative, enlightening, uncomfortable, and necessary. I had never considered what I chose to hang (or not hang) on my office walls as a privilege, and that was exactly the point. She described numerous episodes when her accomplishments were overlooked or (worse) attributed to a male colleague because she was a woman. I began to understand that graceful self-promotion is not optional for many women in medicine, it is a necessary skill.

This is just one example of how my privilege as a male in medicine contributed to my ignorance of the gender inequities that my female coworkers have faced throughout their careers. My colleague showed a lot of grace by taking the time to help me navigate my male privilege in a constructive manner. I decided to learn more about gender inequities, and eventually determined that I was woefully inadequate as a male ally, not by refusal but by ignorance. I wanted to start earning my colleague’s trust that I would be an ally that she could count on.

Trustworthiness

I wanted to be a trustworthy ally, but what does that entail? Perhaps we can learn from medical education. Trust is a complex construct that is increasingly used as a framework for assessing medical students and residents, such as with entrustable professional activities (EPAs).1,2 Multiple studies have examined the characteristics that make a learner “trustworthy” when determining how much supervision is required.3-8 Ten Cate and Chen performed an interpretivist, narrative review to synthesize the medical education literature on learner trustworthiness in the past 15 years,9 developing five major themes that contribute to trustworthiness: Humility, Capability, Agency, Reliability, and Integrity. Let’s examine each of these through the lens of male allyship.

Humility

Humility involves knowing one’s limits, asking for help, and being receptive to feedback.9 The first thing men need to do is to put their egos in check and recognize that women do not need rescuing; they need partnership. Systemic inequities have led to men holding the majority of leadership positions and significant sociopolitical capital, and correcting these inequities is more feasible when those in leadership and positions of power contribute. Women don’t need knights in shining armor, they need collaborative activism.

Humility also means a willingness to admit fallibility and to ask for help. Men often don’t know what they don’t know (see my foibles in the opening). As David G. Smith, PhD, and W. Brad Johnson, PhD, write in their book, “Good Guys,” “There are no perfect allies. As you work to become a better ally for the women around you, you will undoubtedly make a mistake.”10 Men must accept feedback on their shortcomings as allies without feeling as though they are losing their sociopolitical standing. Allyship for women does not mean there is a devaluing of men. We must escape a “zero-sum” mindset. Mistakes are where growth happens, but only if we approach our missteps with humility.

Capability

Capability entails having the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be a strong ally. Allyship is not intuitive for most men for several reasons. Many men do not experience the same biases or systemic inequities that women do, and therefore perceive them less frequently. I want to acknowledge that men can be victims of other systemic biases such as those against one’s race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or any number of factors. Men who face inequities for these other reasons may be more cognizant of the biases women face. Even so, allyship is a skill that few men have been explicitly taught. Even if taught, few standard or organized mechanisms for feedback on allyship capability exist. How, then, can men become capable allies?

Just like in medical education, men must become self-directed learners who seek to build capability and receive feedback on their performance as allies. Men should seek allyship training through local women-in-medicine programs or organizations, or through the increasing number of national education options such as the recent ADVANCE PHM Gender Equity Symposium. As with learning any skill, men should go to the literature, seeking knowledge from experts in the field. I recommend starting with “Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace10 or “Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women.”11 Both books, by Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson, are great entry points into the gender allyship literature. Seek out other resources from local experts on gender equity and allyship. Both aforementioned books were recommended to me by a friend and gender equity expert; without her guidance I would not have known where to start.

Agency

Agency involves being proactive and engaged rather than passive or apathetic. Men must be enthusiastic allies who seek out opportunities to mentor and sponsor women rather than waiting for others to ask. Agency requires being curious and passionate about improving. Most men in medicine are not openly and explicitly misogynistic or sexist, but many are only passive when it comes to gender equity and allyship. Trustworthy allyship entails turning passive support into active change. Not sure how to start? A good first step is to ask female colleagues questions such as, “What can I do to be a better ally for you in the workplace?” or “What are some things at work that are most challenging to you, but I might not notice because I’m a man?” Curiosity is the springboard toward agency.

Reliability

Reliability means being conscientious, accountable, and doing what we say we will do. Nothing undermines trustworthiness faster than making a commitment and not following through. Allyship cannot be a show or an attempt to get public plaudits. It is a longitudinal commitment to supporting women through individual mentorship and sponsorship, and to work toward institutional and systems change.

Reliability also means taking an equitable approach to what Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson call “office housework.” They define this as “administrative work that is necessary but undervalued, unlikely to lead to promotion, and disproportionately assigned to women.”10 In medicine, these tasks include organizing meetings, taking notes, planning social events, and remembering to celebrate colleagues’ achievements and milestones. Men should take on more of these tasks and advocate for change when the distribution of office housework in their workplace is inequitably directed toward women.

Integrity

Integrity involves honesty, professionalism, and benevolence. It is about making the morally correct choice even if there is potential risk. When men see gender inequity, they have an obligation to speak up. Whether it is overtly misogynistic behavior, subtle sexism, use of gendered language, inequitable distribution of office housework, lack of inclusivity and recognition for women, or another form of inequity, men must act with integrity and make it clear that they are partnering with women for change. Integrity means being an ally even when women are not present, and advocating that women be “at the table” for important conversations.

Beyond the individual

Allyship cannot end with individual actions; systems changes that build trustworthy institutions are necessary. Organizational leaders must approach gender conversations with humility to critically examine inequities and agency to implement meaningful changes. Workplace cultures and institutional policies should be reviewed with an eye toward system-level integrity and reliability for promoting and supporting women. Ongoing faculty and staff development programs must provide men with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (capability) to be strong allies. We have a long history of male-dominated institutions that are unfair or (worse) unsafe for women. Many systems are designed in a way that disadvantages women. These systems must be redesigned through an equity lens to start building trust with women in medicine.

Becoming trustworthy is a process

Even the best male allies have room to improve their trustworthiness. Many men (myself included) have a LOT of room to improve, but they should not get discouraged by the amount of ground to be gained. Steady, deliberate improvement in men’s humility, capability, agency, reliability, and integrity can build the foundation of trust with female colleagues. Trust takes time. It takes effort. It takes vulnerability. It is an ongoing, developmental process that requires deliberate practice, frequent reflection, and feedback from our female colleagues.

Dr. Kinnear is associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati Medical Center. He is associate program director for the Med-Peds and Internal Medicine residency programs.

References

1. Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013 Mar;5(1):157-8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1.

2. Ten Cate O. Entrustment decisions: Bringing the patient into the assessment equation. Acad Med. 2017 Jun;92(6):736-8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001623.

3. Kennedy TJT et al. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008 Oct;83(10 Suppl):S89-92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7.

4. Choo KJ et al. How do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014 Mar;9(3):169-75. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2150.

5. Hauer KE et al. How clinical supervisors develop trust in their trainees: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2015 Aug;49(8):783-95. doi: 10.1111/medu.12745.

6. Sterkenburg A et al. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1408-17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab0ec.

7. Sheu L et al. How supervisor experience influences trust, supervision, and trainee learning: A qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017 Sep;92(9):1320-7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001560.

8. Pingree EW et al. Encouraging entrustment: A qualitative study of resident behaviors that promote entrustment. Acad Med. 2020 Nov;95(11):1718-25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003487.

9. Ten Cate O, Chen HC. The ingredients of a rich entrustment decision. Med Teach. 2020 Dec;42(12):1413-20. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1817348.

10. Smith DG, Johnson WB. Good guys: How men can be better allies for women in the workplace: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation 2020.

11. Johnson WB, Smith D. Athena rising: How and why men should mentor women: Routledge 2016.

“If you want to be trusted, be trustworthy” – Stephen Covey

A few years ago, while working in my office, a female colleague stopped by for a casual chat. During the course of the conversation, she noticed that I did not have any diplomas or certificates hanging on my office walls. Instead, there were clusters of pictures drawn by my children, family photos, and a white board with my “to-do” list. The only wall art was a print of Banksy’s “The Thinker Monkey,” which depicts a monkey with its fist to its chin similar to Rodin’s famous sculpture, “Le Penseur.”

When asked why I didn’t hang any diplomas or awards, I replied that I preferred to keep my office atmosphere light and fun, and to focus on future goals rather than past accomplishments. I could see her jaw tense. Her frustration appeared deep, but it was for reasons beyond just my self-righteous tone. She said, “You know, I appreciate your focus on future goals, but it’s a pretty privileged position to not have to worry about sharing your accomplishments publicly.”

What followed was a discussion that was generative, enlightening, uncomfortable, and necessary. I had never considered what I chose to hang (or not hang) on my office walls as a privilege, and that was exactly the point. She described numerous episodes when her accomplishments were overlooked or (worse) attributed to a male colleague because she was a woman. I began to understand that graceful self-promotion is not optional for many women in medicine, it is a necessary skill.

This is just one example of how my privilege as a male in medicine contributed to my ignorance of the gender inequities that my female coworkers have faced throughout their careers. My colleague showed a lot of grace by taking the time to help me navigate my male privilege in a constructive manner. I decided to learn more about gender inequities, and eventually determined that I was woefully inadequate as a male ally, not by refusal but by ignorance. I wanted to start earning my colleague’s trust that I would be an ally that she could count on.

Trustworthiness

I wanted to be a trustworthy ally, but what does that entail? Perhaps we can learn from medical education. Trust is a complex construct that is increasingly used as a framework for assessing medical students and residents, such as with entrustable professional activities (EPAs).1,2 Multiple studies have examined the characteristics that make a learner “trustworthy” when determining how much supervision is required.3-8 Ten Cate and Chen performed an interpretivist, narrative review to synthesize the medical education literature on learner trustworthiness in the past 15 years,9 developing five major themes that contribute to trustworthiness: Humility, Capability, Agency, Reliability, and Integrity. Let’s examine each of these through the lens of male allyship.

Humility

Humility involves knowing one’s limits, asking for help, and being receptive to feedback.9 The first thing men need to do is to put their egos in check and recognize that women do not need rescuing; they need partnership. Systemic inequities have led to men holding the majority of leadership positions and significant sociopolitical capital, and correcting these inequities is more feasible when those in leadership and positions of power contribute. Women don’t need knights in shining armor, they need collaborative activism.

Humility also means a willingness to admit fallibility and to ask for help. Men often don’t know what they don’t know (see my foibles in the opening). As David G. Smith, PhD, and W. Brad Johnson, PhD, write in their book, “Good Guys,” “There are no perfect allies. As you work to become a better ally for the women around you, you will undoubtedly make a mistake.”10 Men must accept feedback on their shortcomings as allies without feeling as though they are losing their sociopolitical standing. Allyship for women does not mean there is a devaluing of men. We must escape a “zero-sum” mindset. Mistakes are where growth happens, but only if we approach our missteps with humility.

Capability

Capability entails having the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be a strong ally. Allyship is not intuitive for most men for several reasons. Many men do not experience the same biases or systemic inequities that women do, and therefore perceive them less frequently. I want to acknowledge that men can be victims of other systemic biases such as those against one’s race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or any number of factors. Men who face inequities for these other reasons may be more cognizant of the biases women face. Even so, allyship is a skill that few men have been explicitly taught. Even if taught, few standard or organized mechanisms for feedback on allyship capability exist. How, then, can men become capable allies?

Just like in medical education, men must become self-directed learners who seek to build capability and receive feedback on their performance as allies. Men should seek allyship training through local women-in-medicine programs or organizations, or through the increasing number of national education options such as the recent ADVANCE PHM Gender Equity Symposium. As with learning any skill, men should go to the literature, seeking knowledge from experts in the field. I recommend starting with “Good Guys: How Men Can Be Better Allies for Women in the Workplace10 or “Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women.”11 Both books, by Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson, are great entry points into the gender allyship literature. Seek out other resources from local experts on gender equity and allyship. Both aforementioned books were recommended to me by a friend and gender equity expert; without her guidance I would not have known where to start.

Agency

Agency involves being proactive and engaged rather than passive or apathetic. Men must be enthusiastic allies who seek out opportunities to mentor and sponsor women rather than waiting for others to ask. Agency requires being curious and passionate about improving. Most men in medicine are not openly and explicitly misogynistic or sexist, but many are only passive when it comes to gender equity and allyship. Trustworthy allyship entails turning passive support into active change. Not sure how to start? A good first step is to ask female colleagues questions such as, “What can I do to be a better ally for you in the workplace?” or “What are some things at work that are most challenging to you, but I might not notice because I’m a man?” Curiosity is the springboard toward agency.

Reliability

Reliability means being conscientious, accountable, and doing what we say we will do. Nothing undermines trustworthiness faster than making a commitment and not following through. Allyship cannot be a show or an attempt to get public plaudits. It is a longitudinal commitment to supporting women through individual mentorship and sponsorship, and to work toward institutional and systems change.

Reliability also means taking an equitable approach to what Dr. Smith and Dr. Johnson call “office housework.” They define this as “administrative work that is necessary but undervalued, unlikely to lead to promotion, and disproportionately assigned to women.”10 In medicine, these tasks include organizing meetings, taking notes, planning social events, and remembering to celebrate colleagues’ achievements and milestones. Men should take on more of these tasks and advocate for change when the distribution of office housework in their workplace is inequitably directed toward women.

Integrity

Integrity involves honesty, professionalism, and benevolence. It is about making the morally correct choice even if there is potential risk. When men see gender inequity, they have an obligation to speak up. Whether it is overtly misogynistic behavior, subtle sexism, use of gendered language, inequitable distribution of office housework, lack of inclusivity and recognition for women, or another form of inequity, men must act with integrity and make it clear that they are partnering with women for change. Integrity means being an ally even when women are not present, and advocating that women be “at the table” for important conversations.

Beyond the individual

Allyship cannot end with individual actions; systems changes that build trustworthy institutions are necessary. Organizational leaders must approach gender conversations with humility to critically examine inequities and agency to implement meaningful changes. Workplace cultures and institutional policies should be reviewed with an eye toward system-level integrity and reliability for promoting and supporting women. Ongoing faculty and staff development programs must provide men with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (capability) to be strong allies. We have a long history of male-dominated institutions that are unfair or (worse) unsafe for women. Many systems are designed in a way that disadvantages women. These systems must be redesigned through an equity lens to start building trust with women in medicine.

Becoming trustworthy is a process

Even the best male allies have room to improve their trustworthiness. Many men (myself included) have a LOT of room to improve, but they should not get discouraged by the amount of ground to be gained. Steady, deliberate improvement in men’s humility, capability, agency, reliability, and integrity can build the foundation of trust with female colleagues. Trust takes time. It takes effort. It takes vulnerability. It is an ongoing, developmental process that requires deliberate practice, frequent reflection, and feedback from our female colleagues.

Dr. Kinnear is associate professor of internal medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati Medical Center. He is associate program director for the Med-Peds and Internal Medicine residency programs.

References

1. Ten Cate O. Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. J Grad Med Educ. 2013 Mar;5(1):157-8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1.

2. Ten Cate O. Entrustment decisions: Bringing the patient into the assessment equation. Acad Med. 2017 Jun;92(6):736-8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001623.

3. Kennedy TJT et al. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008 Oct;83(10 Suppl):S89-92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7.

4. Choo KJ et al. How do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014 Mar;9(3):169-75. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2150.

5. Hauer KE et al. How clinical supervisors develop trust in their trainees: A qualitative study. Med Educ. 2015 Aug;49(8):783-95. doi: 10.1111/medu.12745.

6. Sterkenburg A et al. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010 Sep;85(9):1408-17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab0ec.

7. Sheu L et al. How supervisor experience influences trust, supervision, and trainee learning: A qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017 Sep;92(9):1320-7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001560.

8. Pingree EW et al. Encouraging entrustment: A qualitative study of resident behaviors that promote entrustment. Acad Med. 2020 Nov;95(11):1718-25. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003487.

9. Ten Cate O, Chen HC. The ingredients of a rich entrustment decision. Med Teach. 2020 Dec;42(12):1413-20. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1817348.

10. Smith DG, Johnson WB. Good guys: How men can be better allies for women in the workplace: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation 2020.

11. Johnson WB, Smith D. Athena rising: How and why men should mentor women: Routledge 2016.

Hormone blocker sticker shock – again – as patients lose cheaper drug option

In 2020, he’d fought to get insurance to cover a lower-priced version of a drug his then-8-year-old needed. She’d been diagnosed with central precocious puberty, a rare condition marked by early onset of sexual development – often years earlier than one’s peers. KHN and NPR wrote about Dr. Taksali and his family as part of the Bill of the Month series.

The girl’s doctors and the Taksalis decided to put her puberty on pause with a hormone-blocking drug implant that would be placed under the skin in her arm and release a little bit of the medication each day.

Dr. Taksali, an orthopedic surgeon, learned there were two nearly identical drug products made by Endo Pharmaceuticals, both containing 50 mg of the hormone blocker histrelin. One cost more than eight times more than the other. He wanted to use the cheaper one, Vantas, which costs about $4,800 per implant. But his insurer would not initially cover it, instead preferring Supprelin LA, which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat central precocious puberty, and costs about $43,000.

Vantas can be prescribed off label for the condition, and after much back-and-forth dialogue, Dr. Taksali finally got the insurer to cover it.

Then this summer, it was time to replace the implant.

“I thought we would just get a Vantas replacement,” Dr. Taksali said. “In my mind, I was like: ‘Well, she got it the first time, and we’ve already kind of fought the battle with the insurance company and, you know, got it approved.”

But during a virtual appointment with his daughter’s doctor, he learned they couldn’t get Vantas. No one could. There was a Vantas shortage.

Endo cited a manufacturing problem. Batches of Vantas weren’t coming out right and couldn’t be released to the public, the company’s vice president of corporate affairs, Heather Zoumas Lubeski, said in an email. Vantas and Supprelin were made in the same facility, but the problem affected only Vantas, she wrote, stressing that the drugs are “not identical products.”

In August, Endo’s president and CEO, Blaise Coleman, told investors Supprelin was doing particularly well for the company. Revenue had grown by 79%, compared with the same quarter the year before. The growth was driven in part, Mr. Coleman explained, “by stronger-than-expected demand resulting from expanded patient awareness and a competitor product shortage,” he said.

What competitor product shortage? Could that be Vantas?

Asked about this, Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said Mr. Coleman wasn’t referring to Vantas. Since Vantas isn’t approved to treat central precocious puberty, it can’t technically be considered a competitor to Supprelin. Mr. Coleman was referring to the rival product Lupron Depot-Ped, not an implant, but an injection made by AbbVie, Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said.

Dr. Taksali was skeptical.

“It’s all very curious, like, huh, you know, when this particular option went away and your profits went up nearly 80% from the more expensive drug,” he said.

Then, in September, Endo told the FDA it stopped making Vantas for good.

Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said that, when Endo investigated its Vantas manufacturing problem, it wasn’t able to find “a suitable corrective action that resolves the issue.”

“As a result, and after analysis of the market for the availability of alternative therapies, we made the difficult decision to discontinue the supply of this product,” she said via email. “Endo is committed to maintaining the highest quality standards for all of its products.”

Dr. Taksali said he felt resigned to giving his daughter Supprelin even before the shortage turned into a discontinuation. Ultimately, he won’t pay much more out-of-pocket, but his insurance will pay the rest. And that could raise his business’s premiums.

The FDA cannot force Endo to keep making the drug or set a lower price for the remaining one. It doesn’t have the authority. That decision lies with Endo Pharmaceuticals. A drugmaker discontinuing a product isn’t anything new, said Erin Fox, who directs drug information and support services at University of Utah Health hospitals.

“The FDA has very little leverage because there is no requirement for any company to make any drug, no matter how lifesaving,” she said. “We have a capitalist society. We have a free market. And so any company can discontinue anything ... at any time for any reason.”

Still, companies are supposed to tell the FDA about potential shortages and discontinuations ahead of time so it can minimize the impact on public health. It can help a firm resolve a manufacturing issue, decide whether it’s safe to extend an expiration date or help a company making an alternative product to ramp up production.

“The FDA expects that manufacturers will notify the agency before a meaningful disruption in their own supply occurs,” FDA spokesperson Jeremy Kahn wrote in an email. “When the FDA does not receive timely, informative notifications, the agency’s ability to respond appropriately is limited.”

But the rules are somewhat flexible. A company is required to notify the FDA of an upcoming drug supply disruption 6 months before it affects consumers or “as soon as practicable” after that. But their true deadline is 5 business days after manufacturing stops, according to the FDA website.

“They’re supposed to tell the FDA, but even if they don’t, there’s no penalty,” Ms. Fox said. “There’s no teeth in that law. ... Their name can go on the FDA naughty list. That’s pretty much it.”

In rare cases, the FDA will send a noncompliance letter to the drugmaker and require it to explain itself. This has happened only five times since 2015. There is no such letter about Vantas, suggesting that Endo met the FDA’s requirements for notification.

Concerned about potential drug shortages caused by COVID-19 in March 2020, a bipartisan group of legislators introduced the Preventing Drug Shortages Act, which aimed to increase transparency around shortages. But the legislation gained no traction.

As a result of limited FDA power, the intricacies of drug shortages remain opaque, Ms. Fox said. Companies don’t have to make the reasons for shortages public. That sets the Vantas shortage and discontinuation apart from many others. The company is saying more about what happened than most do.

“Many companies will actually just put drugs on temporarily unavailable or long-term backorder, and sometimes that can last years before the company finally makes a decision” on whether to discontinue a product, she said. “It can take a long time, and so it can be frustrating to not know – or to kind of stake your hopes on a product coming back to the market once it’s been in shortage for so long.”

It’s hard to know exactly how many children will be affected by the Vantas discontinuation because data about off-label use is hard to come by.

Erica Eugster, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Indiana University, Indianapolis, said central precocious puberty patients weren’t her first thought when she learned of the Vantas discontinuation.

“I immediately thought about our transgender population,” she said. “They’re the ones that are really going to suffer from this.”

No medications have been FDA approved to treat patients with gender dysphoria, the medical term for when the sex assigned at birth doesn’t match someone’s gender identity, causing them psychological distress. As a result, any drug to stop puberty in this population would be off label, making it difficult for families to get health insurance coverage. Vantas had been a lower-cost option.

The number of transgender patients receiving histrelin implants rose significantly from 2004 to 2016, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

In 2020, he’d fought to get insurance to cover a lower-priced version of a drug his then-8-year-old needed. She’d been diagnosed with central precocious puberty, a rare condition marked by early onset of sexual development – often years earlier than one’s peers. KHN and NPR wrote about Dr. Taksali and his family as part of the Bill of the Month series.

The girl’s doctors and the Taksalis decided to put her puberty on pause with a hormone-blocking drug implant that would be placed under the skin in her arm and release a little bit of the medication each day.

Dr. Taksali, an orthopedic surgeon, learned there were two nearly identical drug products made by Endo Pharmaceuticals, both containing 50 mg of the hormone blocker histrelin. One cost more than eight times more than the other. He wanted to use the cheaper one, Vantas, which costs about $4,800 per implant. But his insurer would not initially cover it, instead preferring Supprelin LA, which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat central precocious puberty, and costs about $43,000.

Vantas can be prescribed off label for the condition, and after much back-and-forth dialogue, Dr. Taksali finally got the insurer to cover it.

Then this summer, it was time to replace the implant.

“I thought we would just get a Vantas replacement,” Dr. Taksali said. “In my mind, I was like: ‘Well, she got it the first time, and we’ve already kind of fought the battle with the insurance company and, you know, got it approved.”

But during a virtual appointment with his daughter’s doctor, he learned they couldn’t get Vantas. No one could. There was a Vantas shortage.

Endo cited a manufacturing problem. Batches of Vantas weren’t coming out right and couldn’t be released to the public, the company’s vice president of corporate affairs, Heather Zoumas Lubeski, said in an email. Vantas and Supprelin were made in the same facility, but the problem affected only Vantas, she wrote, stressing that the drugs are “not identical products.”

In August, Endo’s president and CEO, Blaise Coleman, told investors Supprelin was doing particularly well for the company. Revenue had grown by 79%, compared with the same quarter the year before. The growth was driven in part, Mr. Coleman explained, “by stronger-than-expected demand resulting from expanded patient awareness and a competitor product shortage,” he said.

What competitor product shortage? Could that be Vantas?

Asked about this, Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said Mr. Coleman wasn’t referring to Vantas. Since Vantas isn’t approved to treat central precocious puberty, it can’t technically be considered a competitor to Supprelin. Mr. Coleman was referring to the rival product Lupron Depot-Ped, not an implant, but an injection made by AbbVie, Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said.

Dr. Taksali was skeptical.

“It’s all very curious, like, huh, you know, when this particular option went away and your profits went up nearly 80% from the more expensive drug,” he said.

Then, in September, Endo told the FDA it stopped making Vantas for good.

Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said that, when Endo investigated its Vantas manufacturing problem, it wasn’t able to find “a suitable corrective action that resolves the issue.”

“As a result, and after analysis of the market for the availability of alternative therapies, we made the difficult decision to discontinue the supply of this product,” she said via email. “Endo is committed to maintaining the highest quality standards for all of its products.”

Dr. Taksali said he felt resigned to giving his daughter Supprelin even before the shortage turned into a discontinuation. Ultimately, he won’t pay much more out-of-pocket, but his insurance will pay the rest. And that could raise his business’s premiums.

The FDA cannot force Endo to keep making the drug or set a lower price for the remaining one. It doesn’t have the authority. That decision lies with Endo Pharmaceuticals. A drugmaker discontinuing a product isn’t anything new, said Erin Fox, who directs drug information and support services at University of Utah Health hospitals.

“The FDA has very little leverage because there is no requirement for any company to make any drug, no matter how lifesaving,” she said. “We have a capitalist society. We have a free market. And so any company can discontinue anything ... at any time for any reason.”

Still, companies are supposed to tell the FDA about potential shortages and discontinuations ahead of time so it can minimize the impact on public health. It can help a firm resolve a manufacturing issue, decide whether it’s safe to extend an expiration date or help a company making an alternative product to ramp up production.

“The FDA expects that manufacturers will notify the agency before a meaningful disruption in their own supply occurs,” FDA spokesperson Jeremy Kahn wrote in an email. “When the FDA does not receive timely, informative notifications, the agency’s ability to respond appropriately is limited.”

But the rules are somewhat flexible. A company is required to notify the FDA of an upcoming drug supply disruption 6 months before it affects consumers or “as soon as practicable” after that. But their true deadline is 5 business days after manufacturing stops, according to the FDA website.

“They’re supposed to tell the FDA, but even if they don’t, there’s no penalty,” Ms. Fox said. “There’s no teeth in that law. ... Their name can go on the FDA naughty list. That’s pretty much it.”

In rare cases, the FDA will send a noncompliance letter to the drugmaker and require it to explain itself. This has happened only five times since 2015. There is no such letter about Vantas, suggesting that Endo met the FDA’s requirements for notification.

Concerned about potential drug shortages caused by COVID-19 in March 2020, a bipartisan group of legislators introduced the Preventing Drug Shortages Act, which aimed to increase transparency around shortages. But the legislation gained no traction.

As a result of limited FDA power, the intricacies of drug shortages remain opaque, Ms. Fox said. Companies don’t have to make the reasons for shortages public. That sets the Vantas shortage and discontinuation apart from many others. The company is saying more about what happened than most do.

“Many companies will actually just put drugs on temporarily unavailable or long-term backorder, and sometimes that can last years before the company finally makes a decision” on whether to discontinue a product, she said. “It can take a long time, and so it can be frustrating to not know – or to kind of stake your hopes on a product coming back to the market once it’s been in shortage for so long.”

It’s hard to know exactly how many children will be affected by the Vantas discontinuation because data about off-label use is hard to come by.

Erica Eugster, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Indiana University, Indianapolis, said central precocious puberty patients weren’t her first thought when she learned of the Vantas discontinuation.

“I immediately thought about our transgender population,” she said. “They’re the ones that are really going to suffer from this.”

No medications have been FDA approved to treat patients with gender dysphoria, the medical term for when the sex assigned at birth doesn’t match someone’s gender identity, causing them psychological distress. As a result, any drug to stop puberty in this population would be off label, making it difficult for families to get health insurance coverage. Vantas had been a lower-cost option.

The number of transgender patients receiving histrelin implants rose significantly from 2004 to 2016, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

In 2020, he’d fought to get insurance to cover a lower-priced version of a drug his then-8-year-old needed. She’d been diagnosed with central precocious puberty, a rare condition marked by early onset of sexual development – often years earlier than one’s peers. KHN and NPR wrote about Dr. Taksali and his family as part of the Bill of the Month series.

The girl’s doctors and the Taksalis decided to put her puberty on pause with a hormone-blocking drug implant that would be placed under the skin in her arm and release a little bit of the medication each day.

Dr. Taksali, an orthopedic surgeon, learned there were two nearly identical drug products made by Endo Pharmaceuticals, both containing 50 mg of the hormone blocker histrelin. One cost more than eight times more than the other. He wanted to use the cheaper one, Vantas, which costs about $4,800 per implant. But his insurer would not initially cover it, instead preferring Supprelin LA, which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat central precocious puberty, and costs about $43,000.

Vantas can be prescribed off label for the condition, and after much back-and-forth dialogue, Dr. Taksali finally got the insurer to cover it.

Then this summer, it was time to replace the implant.

“I thought we would just get a Vantas replacement,” Dr. Taksali said. “In my mind, I was like: ‘Well, she got it the first time, and we’ve already kind of fought the battle with the insurance company and, you know, got it approved.”

But during a virtual appointment with his daughter’s doctor, he learned they couldn’t get Vantas. No one could. There was a Vantas shortage.

Endo cited a manufacturing problem. Batches of Vantas weren’t coming out right and couldn’t be released to the public, the company’s vice president of corporate affairs, Heather Zoumas Lubeski, said in an email. Vantas and Supprelin were made in the same facility, but the problem affected only Vantas, she wrote, stressing that the drugs are “not identical products.”

In August, Endo’s president and CEO, Blaise Coleman, told investors Supprelin was doing particularly well for the company. Revenue had grown by 79%, compared with the same quarter the year before. The growth was driven in part, Mr. Coleman explained, “by stronger-than-expected demand resulting from expanded patient awareness and a competitor product shortage,” he said.

What competitor product shortage? Could that be Vantas?

Asked about this, Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said Mr. Coleman wasn’t referring to Vantas. Since Vantas isn’t approved to treat central precocious puberty, it can’t technically be considered a competitor to Supprelin. Mr. Coleman was referring to the rival product Lupron Depot-Ped, not an implant, but an injection made by AbbVie, Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said.

Dr. Taksali was skeptical.

“It’s all very curious, like, huh, you know, when this particular option went away and your profits went up nearly 80% from the more expensive drug,” he said.

Then, in September, Endo told the FDA it stopped making Vantas for good.

Ms. Zoumas Lubeski said that, when Endo investigated its Vantas manufacturing problem, it wasn’t able to find “a suitable corrective action that resolves the issue.”

“As a result, and after analysis of the market for the availability of alternative therapies, we made the difficult decision to discontinue the supply of this product,” she said via email. “Endo is committed to maintaining the highest quality standards for all of its products.”

Dr. Taksali said he felt resigned to giving his daughter Supprelin even before the shortage turned into a discontinuation. Ultimately, he won’t pay much more out-of-pocket, but his insurance will pay the rest. And that could raise his business’s premiums.

The FDA cannot force Endo to keep making the drug or set a lower price for the remaining one. It doesn’t have the authority. That decision lies with Endo Pharmaceuticals. A drugmaker discontinuing a product isn’t anything new, said Erin Fox, who directs drug information and support services at University of Utah Health hospitals.

“The FDA has very little leverage because there is no requirement for any company to make any drug, no matter how lifesaving,” she said. “We have a capitalist society. We have a free market. And so any company can discontinue anything ... at any time for any reason.”

Still, companies are supposed to tell the FDA about potential shortages and discontinuations ahead of time so it can minimize the impact on public health. It can help a firm resolve a manufacturing issue, decide whether it’s safe to extend an expiration date or help a company making an alternative product to ramp up production.

“The FDA expects that manufacturers will notify the agency before a meaningful disruption in their own supply occurs,” FDA spokesperson Jeremy Kahn wrote in an email. “When the FDA does not receive timely, informative notifications, the agency’s ability to respond appropriately is limited.”

But the rules are somewhat flexible. A company is required to notify the FDA of an upcoming drug supply disruption 6 months before it affects consumers or “as soon as practicable” after that. But their true deadline is 5 business days after manufacturing stops, according to the FDA website.

“They’re supposed to tell the FDA, but even if they don’t, there’s no penalty,” Ms. Fox said. “There’s no teeth in that law. ... Their name can go on the FDA naughty list. That’s pretty much it.”

In rare cases, the FDA will send a noncompliance letter to the drugmaker and require it to explain itself. This has happened only five times since 2015. There is no such letter about Vantas, suggesting that Endo met the FDA’s requirements for notification.

Concerned about potential drug shortages caused by COVID-19 in March 2020, a bipartisan group of legislators introduced the Preventing Drug Shortages Act, which aimed to increase transparency around shortages. But the legislation gained no traction.

As a result of limited FDA power, the intricacies of drug shortages remain opaque, Ms. Fox said. Companies don’t have to make the reasons for shortages public. That sets the Vantas shortage and discontinuation apart from many others. The company is saying more about what happened than most do.

“Many companies will actually just put drugs on temporarily unavailable or long-term backorder, and sometimes that can last years before the company finally makes a decision” on whether to discontinue a product, she said. “It can take a long time, and so it can be frustrating to not know – or to kind of stake your hopes on a product coming back to the market once it’s been in shortage for so long.”

It’s hard to know exactly how many children will be affected by the Vantas discontinuation because data about off-label use is hard to come by.

Erica Eugster, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Indiana University, Indianapolis, said central precocious puberty patients weren’t her first thought when she learned of the Vantas discontinuation.

“I immediately thought about our transgender population,” she said. “They’re the ones that are really going to suffer from this.”

No medications have been FDA approved to treat patients with gender dysphoria, the medical term for when the sex assigned at birth doesn’t match someone’s gender identity, causing them psychological distress. As a result, any drug to stop puberty in this population would be off label, making it difficult for families to get health insurance coverage. Vantas had been a lower-cost option.

The number of transgender patients receiving histrelin implants rose significantly from 2004 to 2016, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

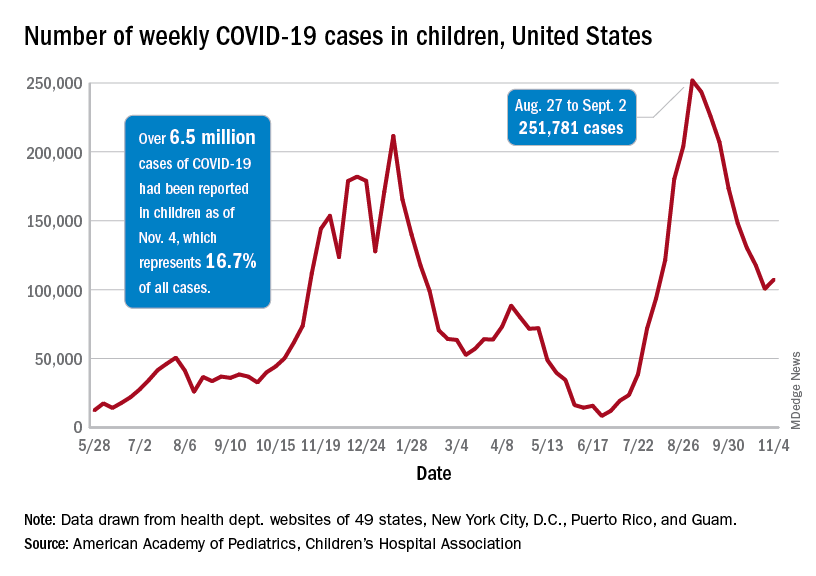

Drug combo at outset of polyarticular JIA benefits patients most

Initiating treatment of polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (polyJIA) with both a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug and a biologic DMARD resulted in more patients achieving clinical inactive disease 2 years later than did starting with only a csDMARD and stepping up to a biologic, according to data presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

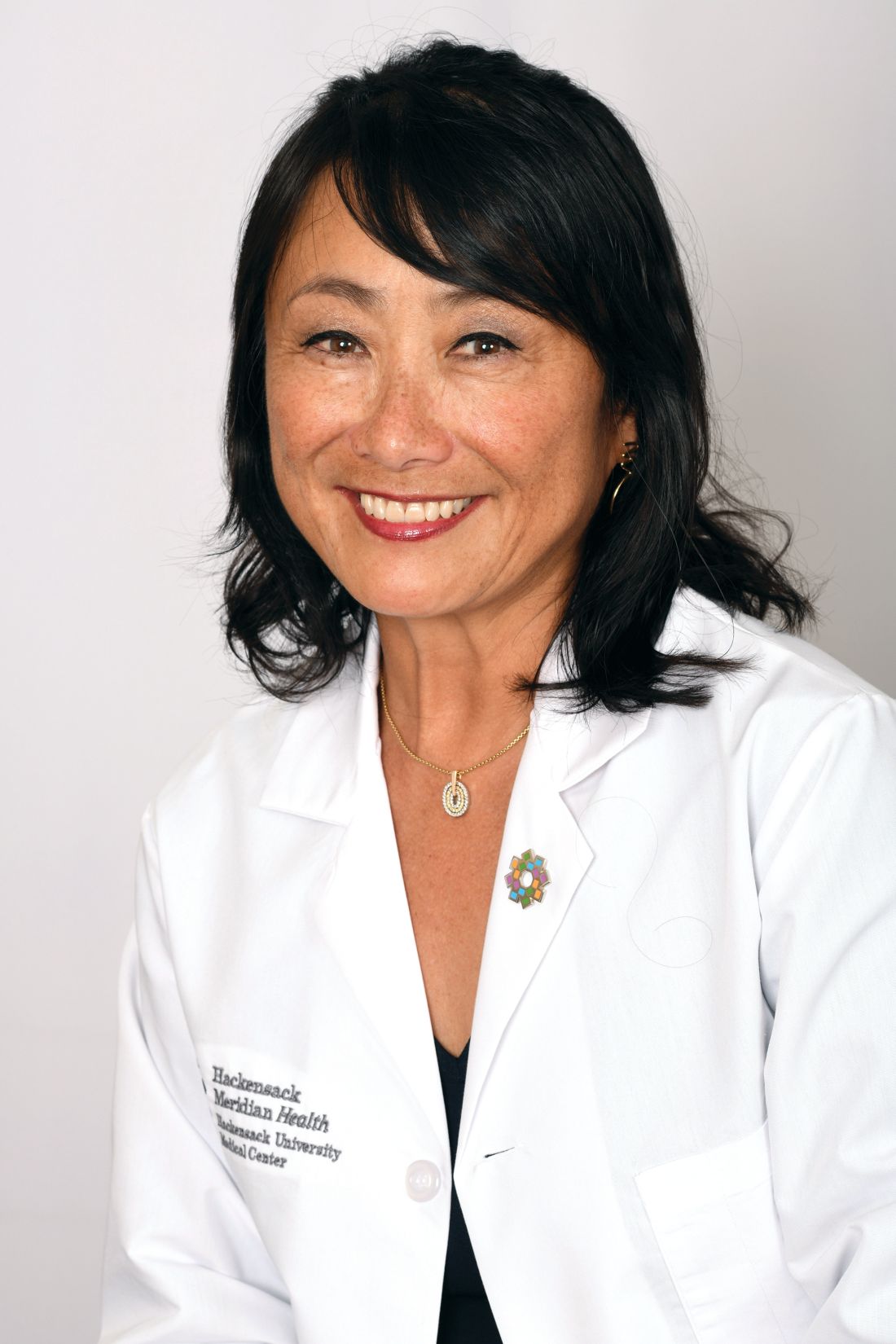

“The 24-month results support the 12-month primary results that suggested that the early-combination group was superior and that, at 24 months, more early combination CTP [consensus treatment plan] patients achieve CID [clinical inactive disease], compared to step up,” Yukiko Kimura, MD, division chief of pediatric rheumatology at HMH Hackensack (N.J.) University Medical Center, told attendees. “This suggests that starting biologics early in polyJIA may lead to better long-term outcomes in many patients.”

Dr. Kimura noted that polyarticular JIA patients are already at risk for poor outcomes, and initial therapy can especially impact outcomes. Further, little evidence exists to suggest when the best time is to start biologics, a gap this study aimed to address.

Diane Brown, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles who was not involved in the study, was pleased to see the results, which she said support her own preferences and practice patterns.

“Starting sooner with combination therapy, taking advantage of the advances with biologics and our long history with methotrexate at the same time, gives better outcomes for the long run,” Dr. Brown said in an interview. “Having studies like this to back up my own recommendations can be very powerful when talking to families, and it is absolutely invaluable when battling with insurance companies who always want you to take the cheapest road.”

Study details

The findings were an update of 12-month results in the CARRA STOP-JIA study that enrolled 400 untreated patients with polyJIA and compared three Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) CTPs. Overall, 49.5% of participants received biologics within 3 months of starting the study. For these updated results, 275 participants had complete data at 24 months for the three CTPs:

- A step-up group of 177 patients who started therapy with a csDMARD and added a biologic if needed at least 3 months later

- An early-combination group of 73 patients who started therapy with a csDMARD and biologic together

- A biologic-first group of 25 patients who started with biologic monotherapy, adding a csDMARD only if needed at least 3 months later.

The primary outcome was the percentage of participants who reached CID without taking glucocorticoids at 24 months. Since the participants were not randomized, the researchers made adjustments to account for baseline differences between the groups, including differences in JIA categories, number of active joints, physician global assessment of disease activity, and the clinical Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score based on 10 joints (cJADAS10).

At 24 months in an intention to treat analysis, 59.4% of the early-combination group had achieved CID, compared with 48% of the biologic-first group and 40.1% of the step-up group (P = .009 for early combination vs. step up). All three groups had improved since the 12-month time point, when 37% of the early-combination group, 24% of the biologic-first group, and 32% of the step-up group had reached CID.

There were no significant differences between the groups in secondary outcomes of achieving cJADAS10 inactive disease of 2.5 or less or 70% improvement in pediatric ACR response criteria at 24 months. All groups improved in PROMIS pain interference or mobility measures from baseline. Most of the 17 severe adverse events were infections.

Moving from step-up therapy to early-combination treatment

Dr. Brown said that she spent many years in her practice using the step-up therapy because it was difficult to get insurance companies to pay for biologics without first showing that methotrexate was insufficient.

”But methotrexate takes so long to control the disease that you need a lot of steroids, with all of their side effects, at least temporarily, or you must simply accept a longer period of active and symptomatic disease before you get to that desired state of clinically inactive disease,” Dr. Brown said. “And during that time, you can be accumulating what may be permanent damage to joints, as well as increase in risk of contractures and deconditioning for that child who is too uncomfortable to move and exercise and play normally.”

Dr. Brown is also wary of using a biologic as an initial therapy by itself because the actions of biologics are so specific. ”I like to back up the powerful, rapid, and specific actions of a biologic with the broader, if slower, action of methotrexate to minimize chances that the immune system is going to find a way around blockade of a single cytokine by your biologic,” she said.

While patient preference will also play a role in what CTP patients with polyJIA start with, Dr. Brown said that she believes more medication upfront can result in less medication and better outcomes in the long run, as the findings of this study suggest. The results here are helpful when speaking with families who are anxious about “so much medicine” or “such powerful medicines,” she said. ”I hope it will also help ease the fears of other providers who share the same concerns about ‘so much medicine.’ ”

The study’s biggest limitation is not being a randomized, controlled trial, but Dr. Brown said the researchers demonstrated effectively that the disease burden remains similar across the groups at baseline.

”It would also be useful to have a clear breakdown of adverse events and opportunistic infections because an excess of opportunistic infections would be a key concern with early combination therapy,” she said, although she added that the study overall was a ”beautiful example of the value of registry data.”

Dr. Kimura emphasized that polyJIA remains a challenging disease to treat, with 40%-60% of participants not reaching CID at 24 months. The registry follow-up will continue for up to 10 years to hopefully provide more information about longer-term outcomes from different treatments.

The research was funded by a grant from Genentech to CARRA. Dr. Kimura reported royalties from UpToDate and salary support from CARRA. Dr. Brown had no disclosures.

Initiating treatment of polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (polyJIA) with both a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug and a biologic DMARD resulted in more patients achieving clinical inactive disease 2 years later than did starting with only a csDMARD and stepping up to a biologic, according to data presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The 24-month results support the 12-month primary results that suggested that the early-combination group was superior and that, at 24 months, more early combination CTP [consensus treatment plan] patients achieve CID [clinical inactive disease], compared to step up,” Yukiko Kimura, MD, division chief of pediatric rheumatology at HMH Hackensack (N.J.) University Medical Center, told attendees. “This suggests that starting biologics early in polyJIA may lead to better long-term outcomes in many patients.”

Dr. Kimura noted that polyarticular JIA patients are already at risk for poor outcomes, and initial therapy can especially impact outcomes. Further, little evidence exists to suggest when the best time is to start biologics, a gap this study aimed to address.

Diane Brown, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles who was not involved in the study, was pleased to see the results, which she said support her own preferences and practice patterns.

“Starting sooner with combination therapy, taking advantage of the advances with biologics and our long history with methotrexate at the same time, gives better outcomes for the long run,” Dr. Brown said in an interview. “Having studies like this to back up my own recommendations can be very powerful when talking to families, and it is absolutely invaluable when battling with insurance companies who always want you to take the cheapest road.”

Study details

The findings were an update of 12-month results in the CARRA STOP-JIA study that enrolled 400 untreated patients with polyJIA and compared three Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) CTPs. Overall, 49.5% of participants received biologics within 3 months of starting the study. For these updated results, 275 participants had complete data at 24 months for the three CTPs:

- A step-up group of 177 patients who started therapy with a csDMARD and added a biologic if needed at least 3 months later

- An early-combination group of 73 patients who started therapy with a csDMARD and biologic together

- A biologic-first group of 25 patients who started with biologic monotherapy, adding a csDMARD only if needed at least 3 months later.

The primary outcome was the percentage of participants who reached CID without taking glucocorticoids at 24 months. Since the participants were not randomized, the researchers made adjustments to account for baseline differences between the groups, including differences in JIA categories, number of active joints, physician global assessment of disease activity, and the clinical Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score based on 10 joints (cJADAS10).

At 24 months in an intention to treat analysis, 59.4% of the early-combination group had achieved CID, compared with 48% of the biologic-first group and 40.1% of the step-up group (P = .009 for early combination vs. step up). All three groups had improved since the 12-month time point, when 37% of the early-combination group, 24% of the biologic-first group, and 32% of the step-up group had reached CID.

There were no significant differences between the groups in secondary outcomes of achieving cJADAS10 inactive disease of 2.5 or less or 70% improvement in pediatric ACR response criteria at 24 months. All groups improved in PROMIS pain interference or mobility measures from baseline. Most of the 17 severe adverse events were infections.

Moving from step-up therapy to early-combination treatment

Dr. Brown said that she spent many years in her practice using the step-up therapy because it was difficult to get insurance companies to pay for biologics without first showing that methotrexate was insufficient.

”But methotrexate takes so long to control the disease that you need a lot of steroids, with all of their side effects, at least temporarily, or you must simply accept a longer period of active and symptomatic disease before you get to that desired state of clinically inactive disease,” Dr. Brown said. “And during that time, you can be accumulating what may be permanent damage to joints, as well as increase in risk of contractures and deconditioning for that child who is too uncomfortable to move and exercise and play normally.”

Dr. Brown is also wary of using a biologic as an initial therapy by itself because the actions of biologics are so specific. ”I like to back up the powerful, rapid, and specific actions of a biologic with the broader, if slower, action of methotrexate to minimize chances that the immune system is going to find a way around blockade of a single cytokine by your biologic,” she said.

While patient preference will also play a role in what CTP patients with polyJIA start with, Dr. Brown said that she believes more medication upfront can result in less medication and better outcomes in the long run, as the findings of this study suggest. The results here are helpful when speaking with families who are anxious about “so much medicine” or “such powerful medicines,” she said. ”I hope it will also help ease the fears of other providers who share the same concerns about ‘so much medicine.’ ”

The study’s biggest limitation is not being a randomized, controlled trial, but Dr. Brown said the researchers demonstrated effectively that the disease burden remains similar across the groups at baseline.

”It would also be useful to have a clear breakdown of adverse events and opportunistic infections because an excess of opportunistic infections would be a key concern with early combination therapy,” she said, although she added that the study overall was a ”beautiful example of the value of registry data.”

Dr. Kimura emphasized that polyJIA remains a challenging disease to treat, with 40%-60% of participants not reaching CID at 24 months. The registry follow-up will continue for up to 10 years to hopefully provide more information about longer-term outcomes from different treatments.

The research was funded by a grant from Genentech to CARRA. Dr. Kimura reported royalties from UpToDate and salary support from CARRA. Dr. Brown had no disclosures.

Initiating treatment of polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (polyJIA) with both a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug and a biologic DMARD resulted in more patients achieving clinical inactive disease 2 years later than did starting with only a csDMARD and stepping up to a biologic, according to data presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“The 24-month results support the 12-month primary results that suggested that the early-combination group was superior and that, at 24 months, more early combination CTP [consensus treatment plan] patients achieve CID [clinical inactive disease], compared to step up,” Yukiko Kimura, MD, division chief of pediatric rheumatology at HMH Hackensack (N.J.) University Medical Center, told attendees. “This suggests that starting biologics early in polyJIA may lead to better long-term outcomes in many patients.”

Dr. Kimura noted that polyarticular JIA patients are already at risk for poor outcomes, and initial therapy can especially impact outcomes. Further, little evidence exists to suggest when the best time is to start biologics, a gap this study aimed to address.

Diane Brown, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles who was not involved in the study, was pleased to see the results, which she said support her own preferences and practice patterns.

“Starting sooner with combination therapy, taking advantage of the advances with biologics and our long history with methotrexate at the same time, gives better outcomes for the long run,” Dr. Brown said in an interview. “Having studies like this to back up my own recommendations can be very powerful when talking to families, and it is absolutely invaluable when battling with insurance companies who always want you to take the cheapest road.”

Study details

The findings were an update of 12-month results in the CARRA STOP-JIA study that enrolled 400 untreated patients with polyJIA and compared three Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) CTPs. Overall, 49.5% of participants received biologics within 3 months of starting the study. For these updated results, 275 participants had complete data at 24 months for the three CTPs:

- A step-up group of 177 patients who started therapy with a csDMARD and added a biologic if needed at least 3 months later

- An early-combination group of 73 patients who started therapy with a csDMARD and biologic together

- A biologic-first group of 25 patients who started with biologic monotherapy, adding a csDMARD only if needed at least 3 months later.

The primary outcome was the percentage of participants who reached CID without taking glucocorticoids at 24 months. Since the participants were not randomized, the researchers made adjustments to account for baseline differences between the groups, including differences in JIA categories, number of active joints, physician global assessment of disease activity, and the clinical Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score based on 10 joints (cJADAS10).

At 24 months in an intention to treat analysis, 59.4% of the early-combination group had achieved CID, compared with 48% of the biologic-first group and 40.1% of the step-up group (P = .009 for early combination vs. step up). All three groups had improved since the 12-month time point, when 37% of the early-combination group, 24% of the biologic-first group, and 32% of the step-up group had reached CID.

There were no significant differences between the groups in secondary outcomes of achieving cJADAS10 inactive disease of 2.5 or less or 70% improvement in pediatric ACR response criteria at 24 months. All groups improved in PROMIS pain interference or mobility measures from baseline. Most of the 17 severe adverse events were infections.

Moving from step-up therapy to early-combination treatment

Dr. Brown said that she spent many years in her practice using the step-up therapy because it was difficult to get insurance companies to pay for biologics without first showing that methotrexate was insufficient.

”But methotrexate takes so long to control the disease that you need a lot of steroids, with all of their side effects, at least temporarily, or you must simply accept a longer period of active and symptomatic disease before you get to that desired state of clinically inactive disease,” Dr. Brown said. “And during that time, you can be accumulating what may be permanent damage to joints, as well as increase in risk of contractures and deconditioning for that child who is too uncomfortable to move and exercise and play normally.”

Dr. Brown is also wary of using a biologic as an initial therapy by itself because the actions of biologics are so specific. ”I like to back up the powerful, rapid, and specific actions of a biologic with the broader, if slower, action of methotrexate to minimize chances that the immune system is going to find a way around blockade of a single cytokine by your biologic,” she said.

While patient preference will also play a role in what CTP patients with polyJIA start with, Dr. Brown said that she believes more medication upfront can result in less medication and better outcomes in the long run, as the findings of this study suggest. The results here are helpful when speaking with families who are anxious about “so much medicine” or “such powerful medicines,” she said. ”I hope it will also help ease the fears of other providers who share the same concerns about ‘so much medicine.’ ”

The study’s biggest limitation is not being a randomized, controlled trial, but Dr. Brown said the researchers demonstrated effectively that the disease burden remains similar across the groups at baseline.