User login

Tinted Sunscreens: Consumer Preferences Based on Light, Medium, and Dark Skin Tones

Sunscreen formulations typically protect from UV radiation (290–400 nm), as this is a well-established cause of photodamage, photoaging, and skin cancer.1 However, sunlight also consists of visible (400–700 nm) and infrared (>700 nm) radiation.2 In fact, UV radiation only comprises 5% to 7% of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the earth, while visible and infrared lights comprise 44% and 53%, respectively.3 Visible light (VL) is the only portion of the solar spectrum visible to the human eye; it penetrates the skin to a depth range of 90 to 750 µm compared to 1.5 to 90 µm for UV radiation.4 Visible light also may come from artificial sources such as light bulbs and digital screens. The rapidly increasing use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other digital screens that emit high levels of short-wavelength VL has increased concerns about the safety of these devices. Although blue light exposure from screens is small compared with the amount of exposure from the sun, there is concern about the long-term effects of excessive screen time. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to light emitted from electronic devices, even for as little as 1 hour, may cause reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, collagen degradation, and necrosis of skin cells.5 Visible light increases tyrosinase activity and induces immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.4,6

Sunscreens consist of chemical and mineral active ingredients that contain UV filters designed to absorb, scatter, and reflect UV photons with wavelengths up to 380 nm. Historically, traditional options do not protect against the effects induced by VL, as these sunscreens use nanosized particles that help to reduce the white appearance and result in transparency of the product.7 To block VL, the topical agent must be visible. Tinted sunscreens (TSs) are products that combine UV and VL filters. They give a colored base coverage that is achieved by incorporating a blend of black, red, and yellow iron oxides (IOs) and/or pigmentary titanium dioxide (PTD)(ie, titanium dioxide [TD] that is not nanosized). Because TSs offer an instant glow and protect the skin from both sun and artificial light, they have become increasingly popular and have been incorporated into makeup and skin care products to facilitate daily convenient use.

The purpose of this analysis was to study current available options and product factors that may influence consumer preference when choosing a TS based on the reviewer characteristics.

Methods

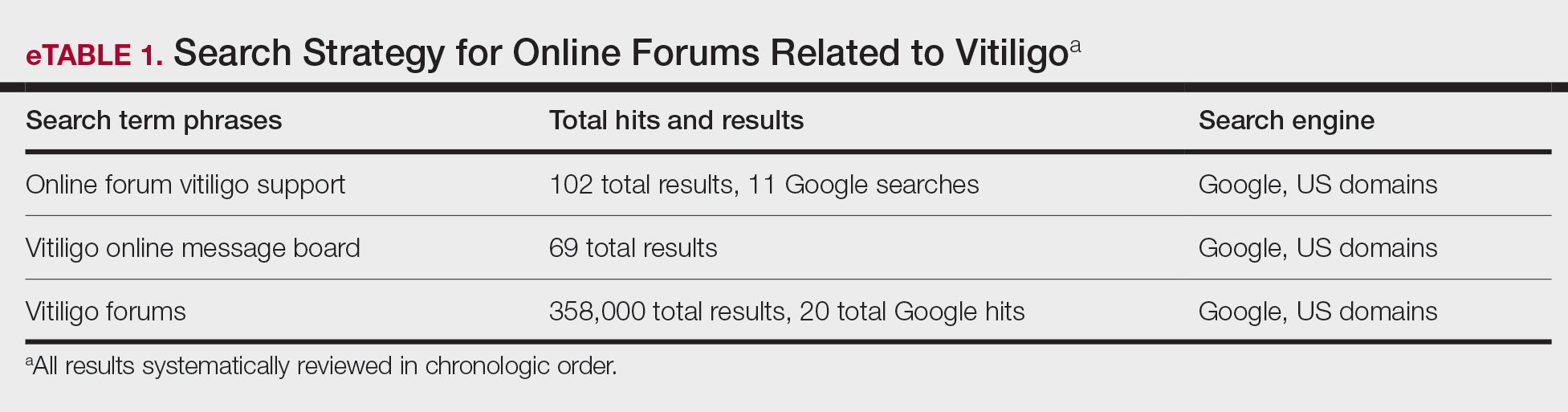

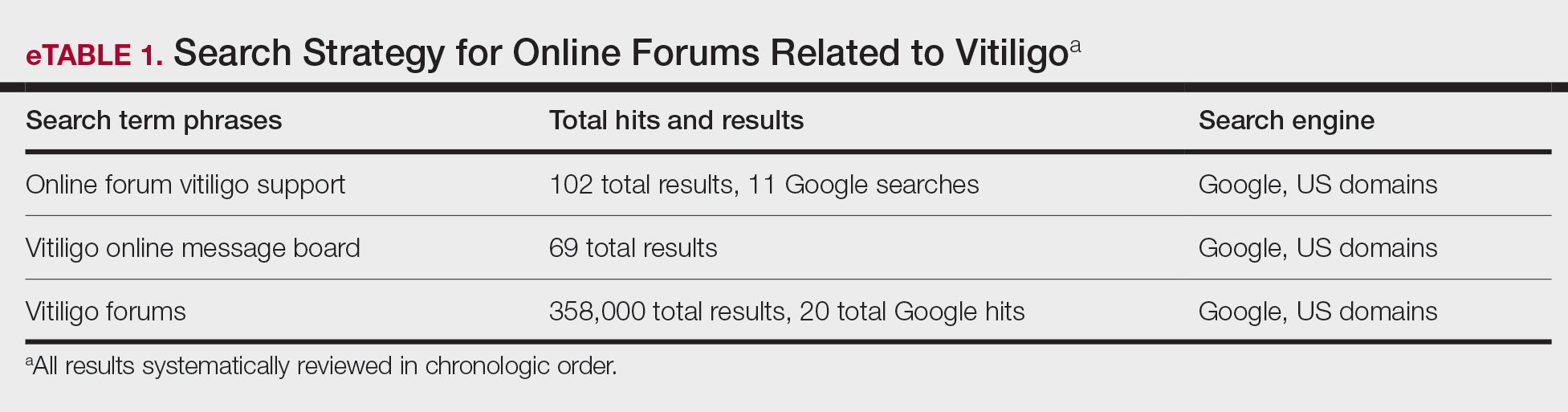

The keyword sunscreen was searched in the broader category of skin care products on an online supplier of sunscreens (www.sephora.com). This supplier was chosen because, unlike other sources, specific reviewer characteristics regarding underlying skin tone also were available. The search produced 161 results. For the purpose of this analysis, only facial TSs containing IO and/or PTD were included. Each sunscreen was checked by the authors, and 58 sunscreens that met the inclusion criteria were identified and further reviewed. Descriptive data, including formulation, sun protection factor (SPF), ingredient type (chemical or physical), pigments used, shades available, additional benefits, price range, rating, and user reviews, were gathered. The authors extracted these data from the product information on the website, manufacturer claims, ratings, and reviewer comments on each of the listed sunscreens.

For each product, the content of the top 10 most helpful positive and negative reviews as voted by consumers (1160 total reviews, consisting of 1 or more comments) was analyzed. Two authors (H.D.L.G. and P.V.) coded consumer-reported comments for positive and negative descriptors into the categories of cosmetic elegance, performance, skin compatibility and tolerance, tone compatibility, and affordability. Cosmetic elegance was defined as any feature associated with skin sensation (eg, greasy), color (eg, white cast), scent, ability to blend, and overall appearance of the product on the skin. Product performance included SPF, effectiveness in preventing sunburn, coverage, and finish claims (ie, matte, glow, invisible). Skin compatibility and tolerance were represented in the reviewers’ comments and reflected how the product performed in association with underlying dermatologic conditions, skin type, and if there were any side effects such as irritation or allergic reactions. Tone compatibility referred to TS color similarity with users’ skin and shades available for individual products. Affordability reflected consumers’ perceptions of the product price. Comments may be included in multiple categories (eg, a product was noted to blend well on the skin but did not provide enough coverage). Of entries, 10% (116/1160 reviews) were coded by first author (H.D.L.G.) to ensure internal validity. Reviewer characteristics were consistently available and were used to determine the top 5 recommended products for light-, medium-, and dark-skinned individuals based on the number of 5-star ratings in each group. Porcelain, fair, and light were considered light skin tones. Medium, tan, and olive were considered medium skin tones. Deep, dark, and ebony were considered dark skin tones.

Results

Sunscreen Characteristics—Among the 161 screened products, 58 met the inclusion criteria. Four types of formulations were included: lotion, cream, liquid, and powder. Twenty-nine (50%) were creams, followed by lotions (19%), liquids (28%), and powders (3%). More than 79% (46/58) of products had a reported SPF of 30 or higher. Sunscreens with an active physical ingredient—the minerals TD and/or zinc oxide (ZO)—were most common (33/58 [57%]), followed by the chemical sunscreens avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and/or octocrylene active ingredients (14/58 [24%]), and a combination of chemical and physical sunscreens (11/58 [19%]). Nearly all products (55/58 [95%]) contained pigmentary IO (red, CI 77491; yellow, CI 77492; black, CI 77499). Notably, only 38% (22/58) of products had more than 1 shade. All products had additional claims associated with being hydrating, having antiaging effects, smoothing texture, minimizing the appearance of pores, softening lines, and/or promoting even skin tone. Traditional physical sunscreens (those containing TD and/or ZO) were more expensive than chemical sunscreens, with a median price of $30. The median review rating was 4.5 of 5 stars, with a median of 2300 customer reviews per product. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

Positive Features of Sunscreens—Based on an analysis of total reviews (N=1160), cosmetic elegance was the most cited positive feature associated with TS products (31%), followed by product performance (10%). Skin compatibility and tolerance (7%), tone compatibility (7%), and affordability (7%) were cited less commonly as positive features. When negative features were cited, consumers mostly noted tone incompatibility (16%) and cosmetic elegance concerns (14%). Product performance (13%) was comparatively cited as a negative feature (Table 1). Exemplary positive comments categorized in cosmetic elegance included the subthemes of rubs in well and natural glow. Exemplary negative comments in cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility categories included the subthemes patchy/dry finish and color mismatch. Table 1 illustrates these findings.

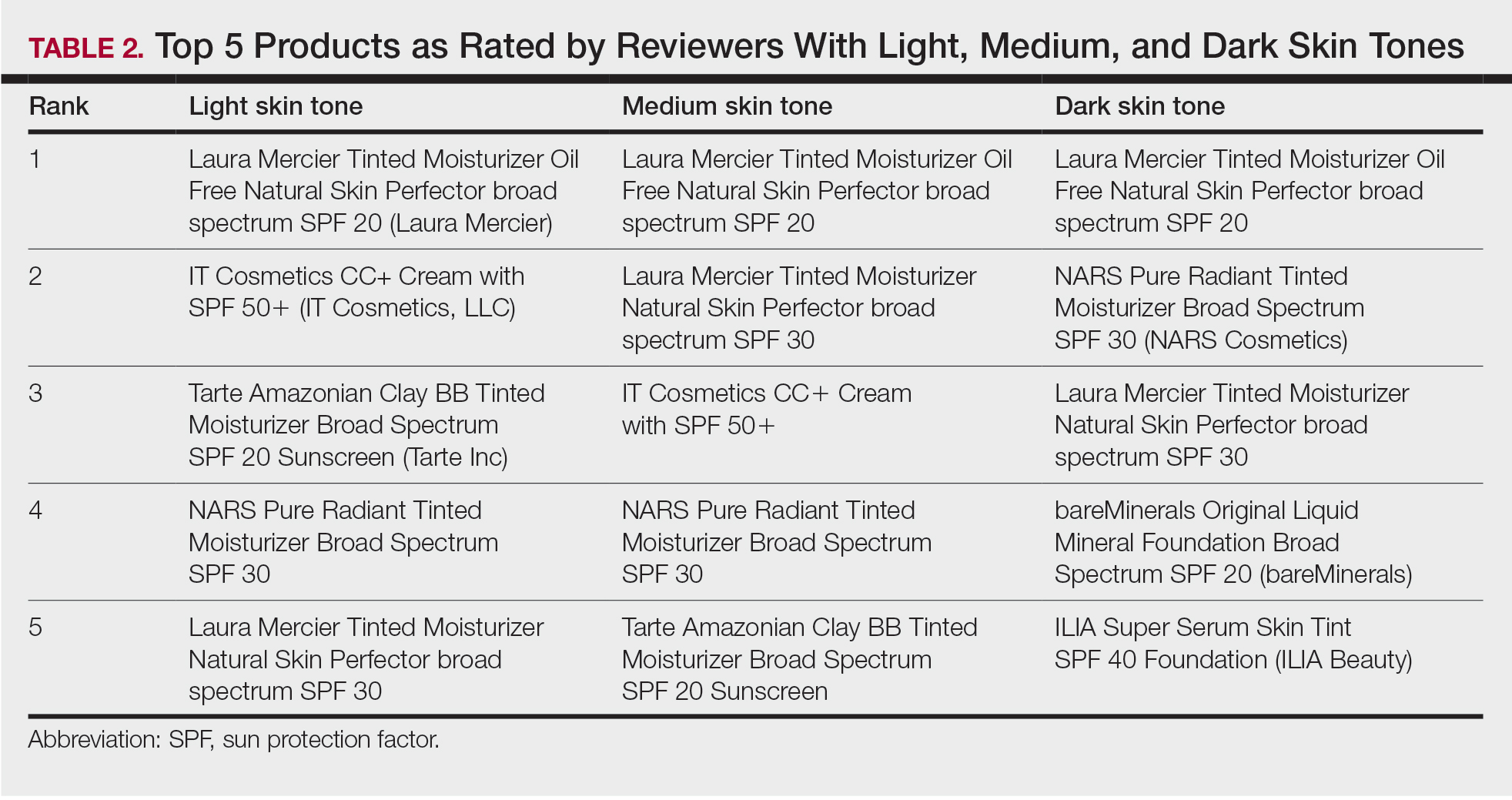

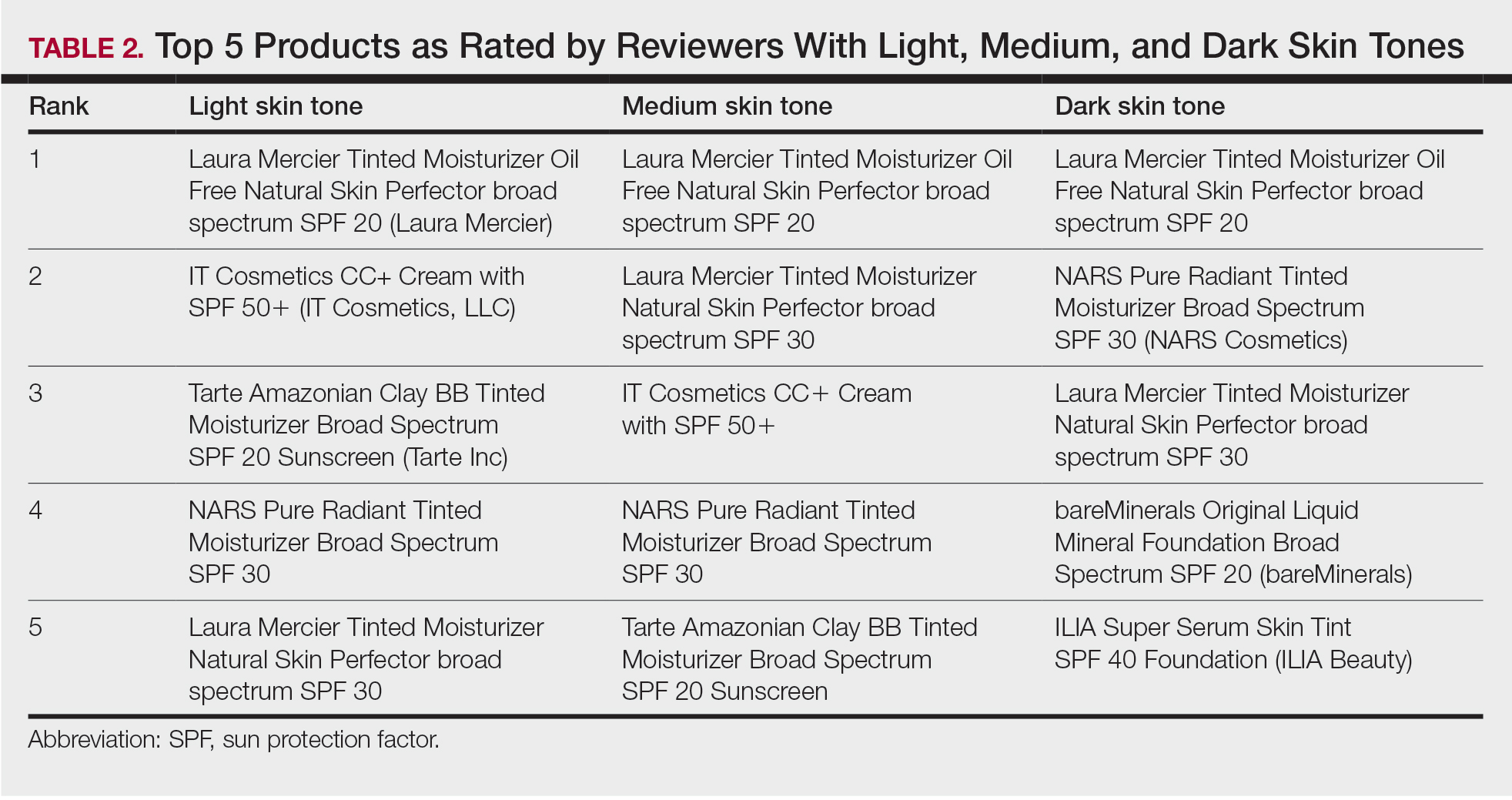

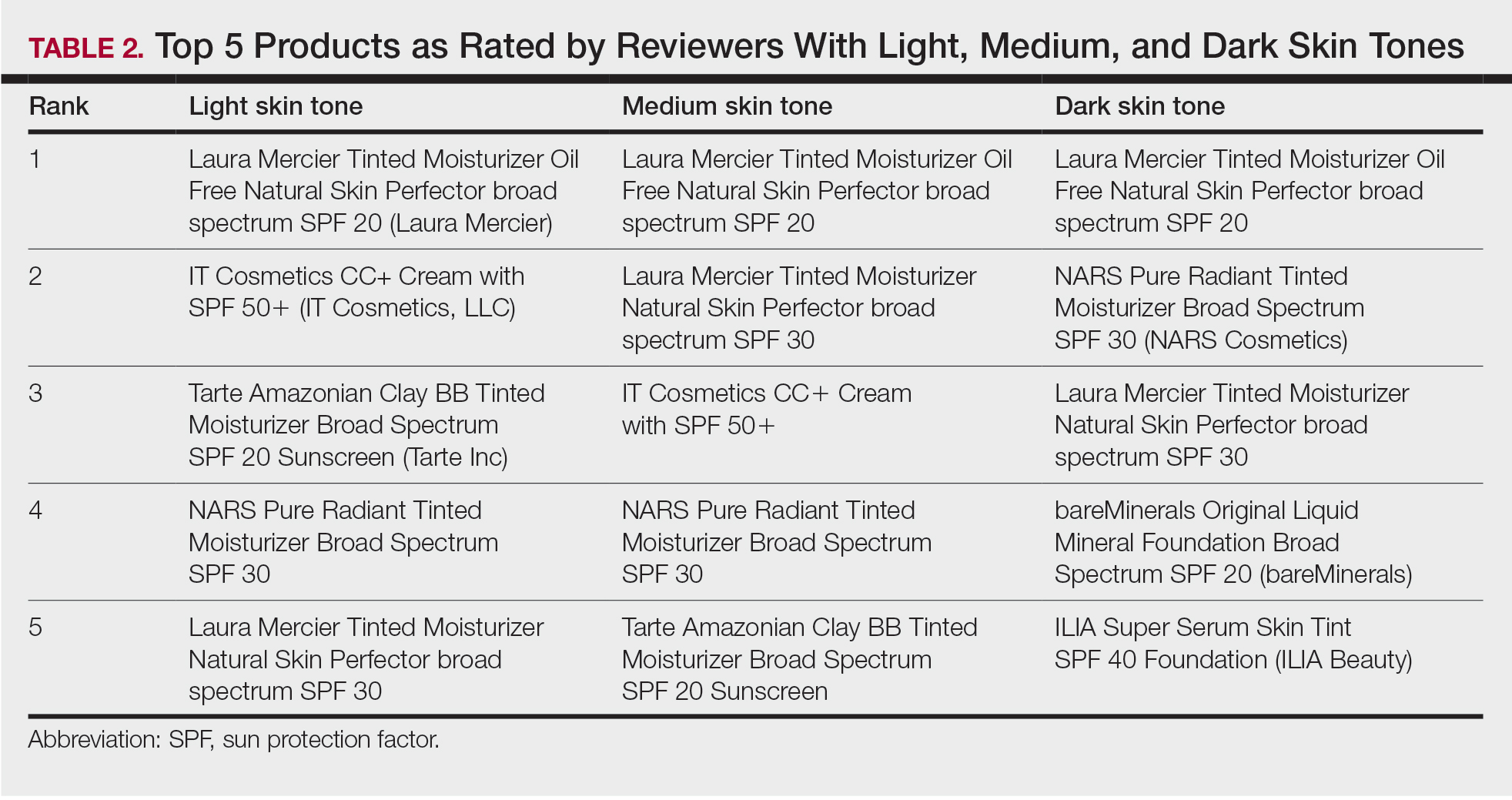

Product Recommendations—The top 5 recommendations of the best TS for each skin tone are listed in Table 2. The mean price of the recommended products was $42 for 1 to 1.9 oz. Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20 (Laura Mercier) was the top product for all 3 groups. Similarly, of 58 products available, the same 5 products—Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20, IT Cosmetics CC+ Cream with SPF 50 (IT Cosmetics, LLC), Tarte Amazonian Clay BB Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 20 (Tarte Cosmetics), NARS Pure Radiant Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 30 (NARS Cosmetics), and Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 30—were considered the best among consumers of all skin tones, with the addition of 2 different products (bareMinerals Original Liquid Mineral Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 [bareMinerals] and ILIA Super Serum Skin Tint SPF 40 Foundation [ILIA Beauty]) in the dark skin group. Notably, these products were the only ones on Sephora’s website that offered up to 30 (22 on average) different shades.

Comment

Tone Compatibility—Tinted sunscreens were created to extend the range of photoprotection into the VL spectrum. The goal of TSs is to incorporate pigments that blend in with the natural skin tone, produce a glow, and have an aesthetically pleasing appearance. To accommodate a variety of skin colors, different shades can be obtained by mixing different amounts of yellow, red, and black IO with or without PTD. The pigments and reflective compounds provide color, opacity, and a natural coverage. Our qualitative analysis provides information on the lack of diversity among shades available for TS, especially for darker skin tones. Of the 58 products evaluated, 62% (32/58) only had 1 shade. In our cohort, tone compatibility was the most commonly cited negative feature. Of note, 89% of these comments were from consumers with dark skin tones, and there was a disproportional number of reviews by darker-skinned individuals compared to users with light and medium skin tones. This is of particular importance, as TSs have been shown to protect against dermatoses that disproportionally affect individuals with skin of color. When comparing sunscreen formulations containing IO with regular mineral sunscreens, Dumbuya et al3 found that IO-containing formulations significantly protected against VL-induced pigmentation compared with untreated skin or mineral sunscreen with SPF 50 or higher in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type IV (P<.001). Similarly, Bernstein et al8 found that exposing patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV to blue-violet light resulted in marked hyperpigmentation that lasted up to 3 months. Visible light elicits immediate and persistent pigment darkening in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin phototype III and above via the photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin and de novo melanogenesis.9 Tinted sunscreens formulated with IO have been shown to aid in the treatment of melasma and prevent hyperpigmentation in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.10 Patients with darker skin tones with dermatoses aggravated or induced by VL, such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, may seek photoprotection provided by TS but find the lack of matching shades unappealing. The dearth of shade diversity that matches all skin tones can lead to inequities and disproportionally affect those with darker skin.

Performance—Tinted sunscreen formulations containing IO have been proven effective in protecting against high-energy VL, especially when combined synergistically with ZO.11 Kaye et al12 found that TSs containing IO and the inorganic filters TD or ZO reduced transmittance of VL more effectively than nontinted sunscreens containing TD or ZO alone or products containing organic filters. The decreased VL transmittance in the former is due to synergistic effects of the VL-scattering properties of the TD and the VL absorption properties of the IO. Similarly, Sayre et al13 demonstrated that IO was superior to TD and ZO in attenuating the transmission of VL. Bernstein et al14 found that darker shades containing higher percentages of IO increased the attenuation of VL to 98% compared with lighter shades attenuating 93%. This correlates with the results of prior studies highlighting the potential of TSs in protecting individuals with skin of color.3 In our cohort, comments regarding product performance and protection were mostly positive, claiming that consistent use reduced hyperpigmentation on the skin surface, giving the appearance of a more even skin tone.

Tolerability—Iron oxides are minerals known to be safe, gentle, and nontoxic on the surface of the skin.15 Two case reports of contact dermatitis due to IO have been reported.16,17 Within our cohort, only a few of the comments (6%) described negative product tolerance or compatibility with their skin type. However, it is more likely that these incompatibilities were due to other ingredients in the product or the individuals’ underlying dermatologic conditions.

Cosmetic Elegance—Most of the sunscreens available on the market today contain micronized forms of TD and ZO particles because they have better cosmetic acceptability.18 However, their reduced size compromises the protection provided against VL whereby the addition of IO is of vital importance. According to the RealSelf Sun Safety Report, only 11% of Americans wear sunscreen daily, and 46% never wear sunscreen.19 The most common reasons consumers reported for not wearing sunscreen included not liking how it looks on the skin, forgetting to apply it, and/or believing that application is inconvenient and time-consuming. Currently, TSs have been incorporated into daily-life products such as makeup, moisturizers, and serums, making application for users easy and convenient, decreasing the necessity of using multiple products, and offering the opportunity to choose from different presentations to make decisions for convenience and/or diverse occasions. Products containing IO blend in with the natural skin tone and have an aesthetically pleasing cosmetic appearance. In our cohort, comments regarding cosmetic elegance were highly valued and were present in multiple reviews (45%), with 69% being positive.

Affordability—In our cohort, product price was not predominantly mentioned in consumers’ reviews. However, negative comments regarding affordability were slightly higher than the positive (56% vs 44%). Notably, the mean price of our top recommendations was $42. Higher price was associated with products with a wider range of shades available. Prior studies have found similar results demonstrating that websites with recommendations on sunscreens for patients with skin of color compared with sunscreens for white or fair skin were more likely to recommend more expensive products (median, $14/oz vs $11.3/oz) despite the lower SPF level.20 According to Schneider,21 daily use of the cheapest sunscreen on the head/neck region recommended for white/pale skin ($2/oz) would lead to an annual cost of $61 compared to $182 for darker skin ($6/oz). This showcases the considerable variation in sunscreen prices for both populations that could potentiate disparities and vulnerability in the latter group.

Conclusion

Tinted sunscreens provide both functional and cosmetic benefits and are a safe, effective, and convenient way to protect against high-energy VL. This study suggests that patients with skin of color encounter difficulties in finding matching shades in TS products. These difficulties may stem from the lack of knowledge regarding dark complexions and undertones and the lack of representation of black and brown skin that has persisted in dermatology research journals and textbooks for decades.22 Our study provides important insights to help dermatologists improve their familiarity with the brands and characteristics of TSs geared to patients with all skin tones, including skin of color. Limitations include single-retailer information and inclusion of both highly and poorly rated comments with subjective data, limiting generalizability. The limited selection of shades for darker skin poses a roadblock to proper treatment and prevention. These data represent an area for improvement within the beauty industry and the dermatologic field to deliver culturally sensitive care by being knowledgeable about darker skin tones and TS formulations tailored to people with skin of color.

- McDaniel D, Farris P, Valacchi G. Atmospheric skin aging-contributors and inhibitors. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:124-137.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Dumbuya H, Grimes PE, Lynch S, et al. Impact of iron-oxide containing formulations against visible light-induced skin pigmentation in skin of color individuals. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:712-717.

- Lyons AB, Trullas C, Kohli I, et al. Photoprotection beyond ultraviolet radiation: a review of tinted sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1393-1397.

- Austin E, Huang A, Adar T, et al. Electronic device generated light increases reactive oxygen species in human fibroblasts [published online February 5, 2018]. Lasers Surg Med. doi:10.1002/lsm.22794

- Randhawa M, Seo I, Liebel F, et al. Visible light induces melanogenesis in human skin through a photoadaptive response. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130949.

- Yeager DG, Lim HW. What’s new in photoprotection: a review of new concepts and controversies. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:149-157.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P. Iron oxides in novel skin care formulations attenuate blue light for enhanced protection against skin damage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:532-537.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Ruvolo E, Fair M, Hutson A, et al. Photoprotection against visible light-induced pigmentation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:589-595.

- Cohen L, Brodsky MA, Zubair R, et al. Cutaneous interaction with visible light: what do we know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30551-X.

- Kaye ET, Levin JA, Blank IH, et al. Efficiency of opaque photoprotective agents in the visible light range. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:351-355.

- Sayre RM, Kollias N, Roberts RL, et al. Physical sunscreens. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1990;41:103-109.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P, et al. Beyond sun protection factor: an approach to environmental protection with novel mineral coatings in a vehicle containing a blend of skincare ingredients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:407-415.

- MacLeman E. Why are iron oxides used? Deep Science website. February 10, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://thedermreview.com/iron-oxides-ci-77491-ci-77492-ci-77499/

- Zugerman C. Contact dermatitis to yellow iron oxide. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:107-109.

- Saxena M, Warshaw E, Ahmed DD. Eyelid allergic contact dermatitis to black iron oxide. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:38-39.

- Smijs TG, Pavel S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2011;4:95-112.

- 2020 RealSelf Sun Safety Report: majority of Americans don’t use sunscreen daily. Practical Dermatology. May 6, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://practicaldermatology.com/news/realself-sun-safety-report-majority-of-americans-dont-use-sunscreen-daily

- Song H, Beckles A, Salian P, et al. Sunscreen recommendations for patients with skin of color in the popular press and in the dermatology clinic. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:165-170.

- Schneider J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Nelson B. How dermatology is failing melanoma patients with skin of color: unanswered questions on risk and eye-opening disparities in outcomes are weighing heavily on melanoma patients with darker skin. in this article, part 1 of a 2-part series, we explore the deadly consequences of racism and inequality in cancer care. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128:7-8.

Sunscreen formulations typically protect from UV radiation (290–400 nm), as this is a well-established cause of photodamage, photoaging, and skin cancer.1 However, sunlight also consists of visible (400–700 nm) and infrared (>700 nm) radiation.2 In fact, UV radiation only comprises 5% to 7% of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the earth, while visible and infrared lights comprise 44% and 53%, respectively.3 Visible light (VL) is the only portion of the solar spectrum visible to the human eye; it penetrates the skin to a depth range of 90 to 750 µm compared to 1.5 to 90 µm for UV radiation.4 Visible light also may come from artificial sources such as light bulbs and digital screens. The rapidly increasing use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other digital screens that emit high levels of short-wavelength VL has increased concerns about the safety of these devices. Although blue light exposure from screens is small compared with the amount of exposure from the sun, there is concern about the long-term effects of excessive screen time. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to light emitted from electronic devices, even for as little as 1 hour, may cause reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, collagen degradation, and necrosis of skin cells.5 Visible light increases tyrosinase activity and induces immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.4,6

Sunscreens consist of chemical and mineral active ingredients that contain UV filters designed to absorb, scatter, and reflect UV photons with wavelengths up to 380 nm. Historically, traditional options do not protect against the effects induced by VL, as these sunscreens use nanosized particles that help to reduce the white appearance and result in transparency of the product.7 To block VL, the topical agent must be visible. Tinted sunscreens (TSs) are products that combine UV and VL filters. They give a colored base coverage that is achieved by incorporating a blend of black, red, and yellow iron oxides (IOs) and/or pigmentary titanium dioxide (PTD)(ie, titanium dioxide [TD] that is not nanosized). Because TSs offer an instant glow and protect the skin from both sun and artificial light, they have become increasingly popular and have been incorporated into makeup and skin care products to facilitate daily convenient use.

The purpose of this analysis was to study current available options and product factors that may influence consumer preference when choosing a TS based on the reviewer characteristics.

Methods

The keyword sunscreen was searched in the broader category of skin care products on an online supplier of sunscreens (www.sephora.com). This supplier was chosen because, unlike other sources, specific reviewer characteristics regarding underlying skin tone also were available. The search produced 161 results. For the purpose of this analysis, only facial TSs containing IO and/or PTD were included. Each sunscreen was checked by the authors, and 58 sunscreens that met the inclusion criteria were identified and further reviewed. Descriptive data, including formulation, sun protection factor (SPF), ingredient type (chemical or physical), pigments used, shades available, additional benefits, price range, rating, and user reviews, were gathered. The authors extracted these data from the product information on the website, manufacturer claims, ratings, and reviewer comments on each of the listed sunscreens.

For each product, the content of the top 10 most helpful positive and negative reviews as voted by consumers (1160 total reviews, consisting of 1 or more comments) was analyzed. Two authors (H.D.L.G. and P.V.) coded consumer-reported comments for positive and negative descriptors into the categories of cosmetic elegance, performance, skin compatibility and tolerance, tone compatibility, and affordability. Cosmetic elegance was defined as any feature associated with skin sensation (eg, greasy), color (eg, white cast), scent, ability to blend, and overall appearance of the product on the skin. Product performance included SPF, effectiveness in preventing sunburn, coverage, and finish claims (ie, matte, glow, invisible). Skin compatibility and tolerance were represented in the reviewers’ comments and reflected how the product performed in association with underlying dermatologic conditions, skin type, and if there were any side effects such as irritation or allergic reactions. Tone compatibility referred to TS color similarity with users’ skin and shades available for individual products. Affordability reflected consumers’ perceptions of the product price. Comments may be included in multiple categories (eg, a product was noted to blend well on the skin but did not provide enough coverage). Of entries, 10% (116/1160 reviews) were coded by first author (H.D.L.G.) to ensure internal validity. Reviewer characteristics were consistently available and were used to determine the top 5 recommended products for light-, medium-, and dark-skinned individuals based on the number of 5-star ratings in each group. Porcelain, fair, and light were considered light skin tones. Medium, tan, and olive were considered medium skin tones. Deep, dark, and ebony were considered dark skin tones.

Results

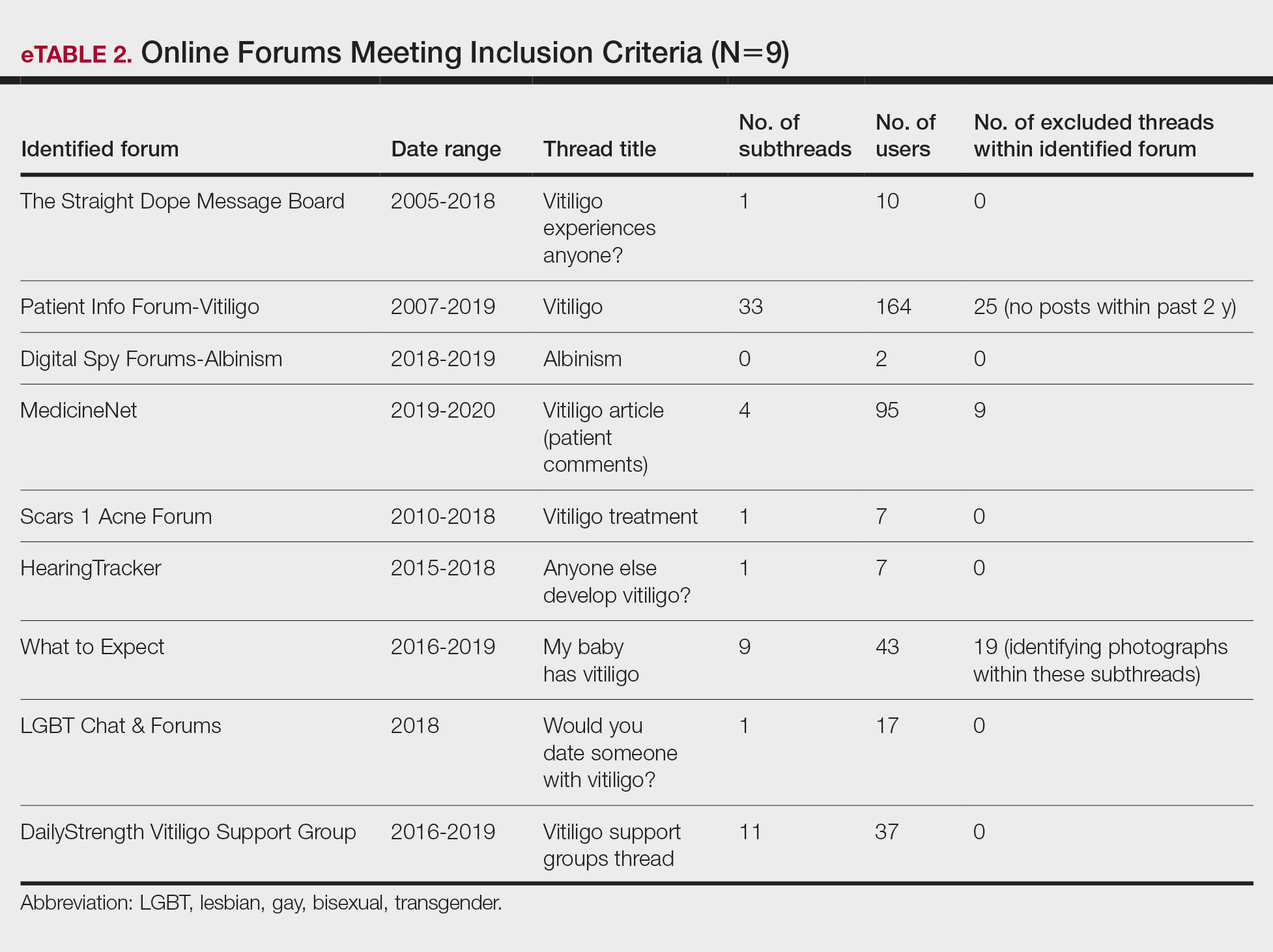

Sunscreen Characteristics—Among the 161 screened products, 58 met the inclusion criteria. Four types of formulations were included: lotion, cream, liquid, and powder. Twenty-nine (50%) were creams, followed by lotions (19%), liquids (28%), and powders (3%). More than 79% (46/58) of products had a reported SPF of 30 or higher. Sunscreens with an active physical ingredient—the minerals TD and/or zinc oxide (ZO)—were most common (33/58 [57%]), followed by the chemical sunscreens avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and/or octocrylene active ingredients (14/58 [24%]), and a combination of chemical and physical sunscreens (11/58 [19%]). Nearly all products (55/58 [95%]) contained pigmentary IO (red, CI 77491; yellow, CI 77492; black, CI 77499). Notably, only 38% (22/58) of products had more than 1 shade. All products had additional claims associated with being hydrating, having antiaging effects, smoothing texture, minimizing the appearance of pores, softening lines, and/or promoting even skin tone. Traditional physical sunscreens (those containing TD and/or ZO) were more expensive than chemical sunscreens, with a median price of $30. The median review rating was 4.5 of 5 stars, with a median of 2300 customer reviews per product. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

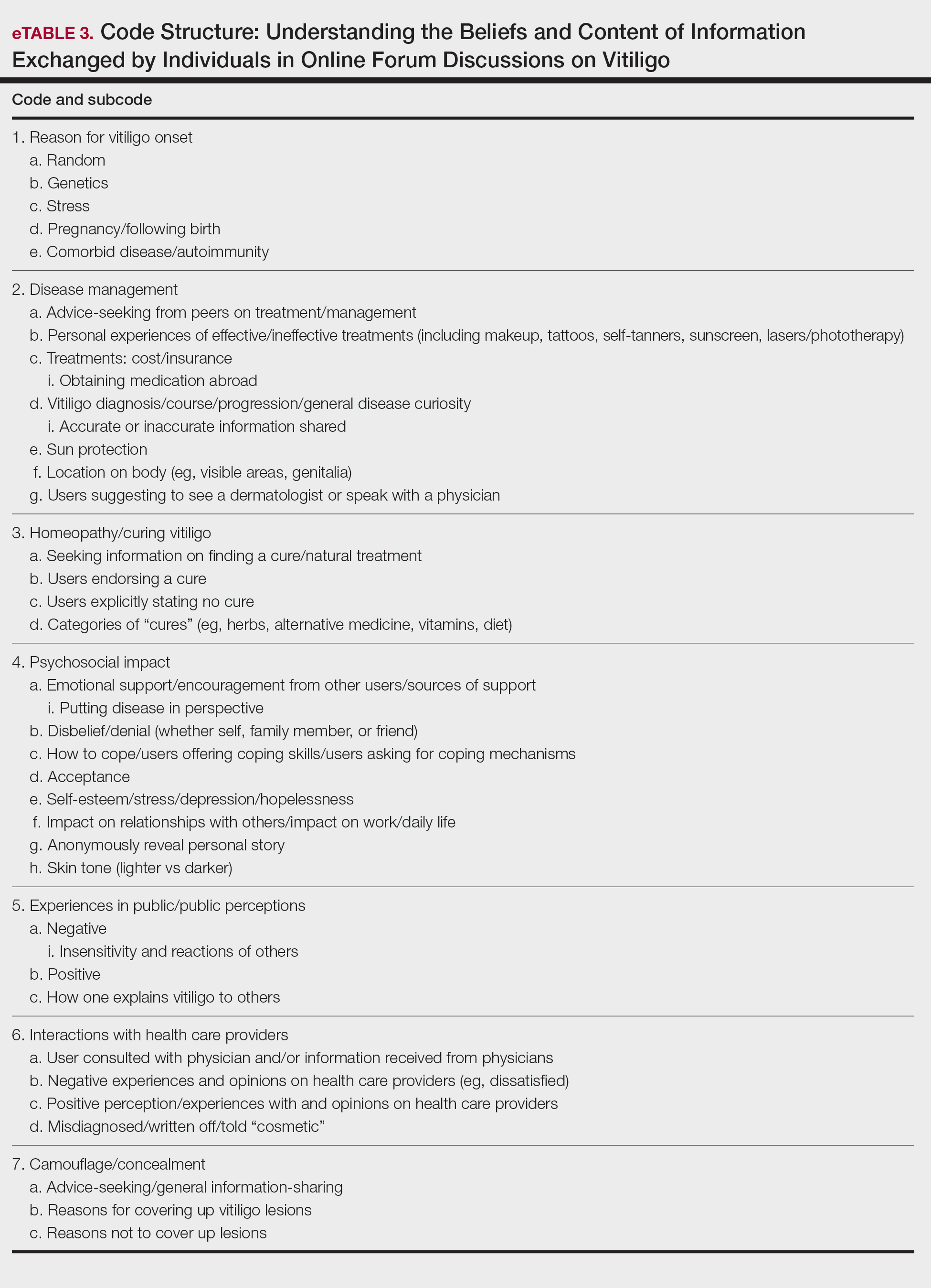

Positive Features of Sunscreens—Based on an analysis of total reviews (N=1160), cosmetic elegance was the most cited positive feature associated with TS products (31%), followed by product performance (10%). Skin compatibility and tolerance (7%), tone compatibility (7%), and affordability (7%) were cited less commonly as positive features. When negative features were cited, consumers mostly noted tone incompatibility (16%) and cosmetic elegance concerns (14%). Product performance (13%) was comparatively cited as a negative feature (Table 1). Exemplary positive comments categorized in cosmetic elegance included the subthemes of rubs in well and natural glow. Exemplary negative comments in cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility categories included the subthemes patchy/dry finish and color mismatch. Table 1 illustrates these findings.

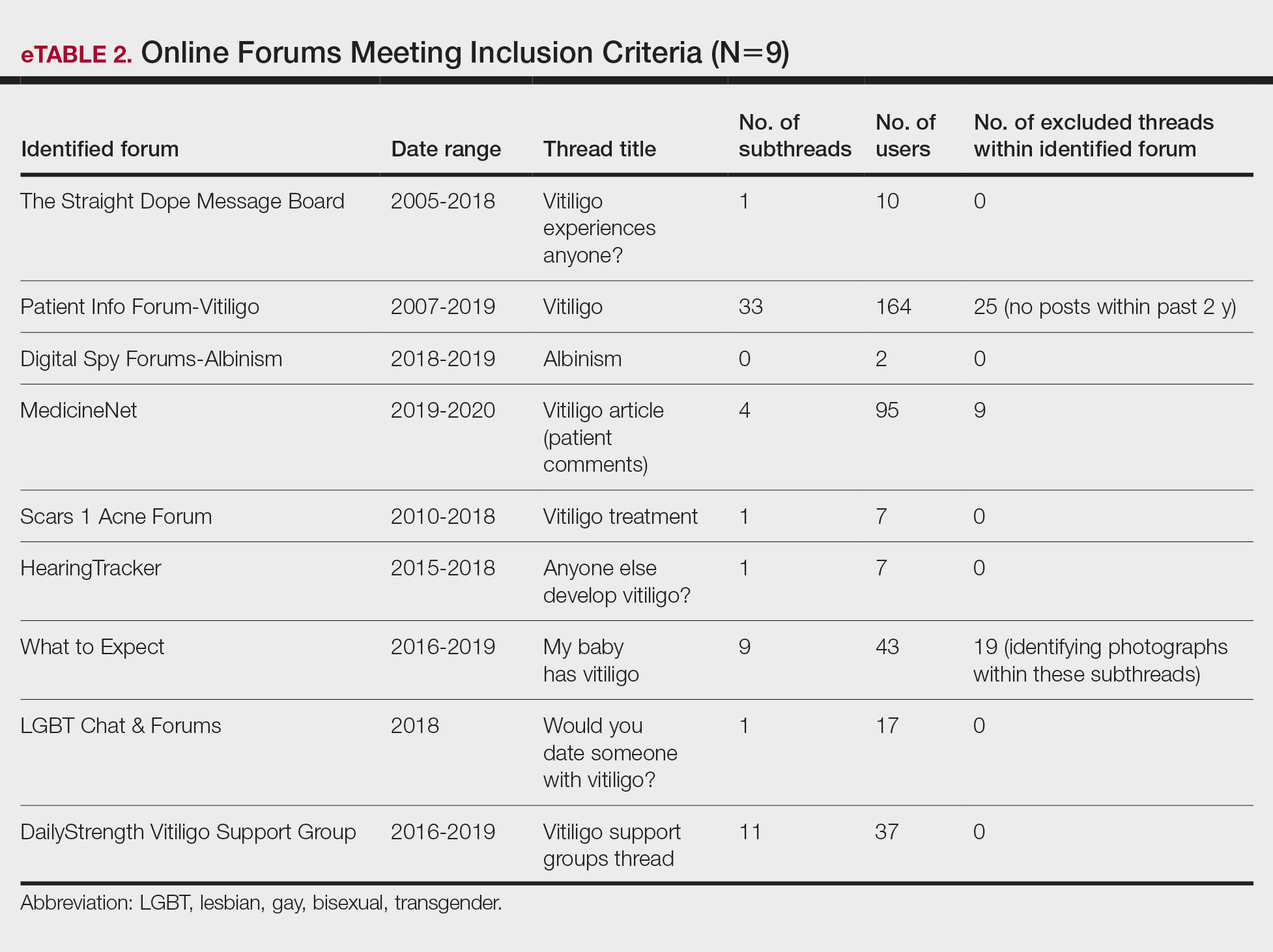

Product Recommendations—The top 5 recommendations of the best TS for each skin tone are listed in Table 2. The mean price of the recommended products was $42 for 1 to 1.9 oz. Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20 (Laura Mercier) was the top product for all 3 groups. Similarly, of 58 products available, the same 5 products—Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20, IT Cosmetics CC+ Cream with SPF 50 (IT Cosmetics, LLC), Tarte Amazonian Clay BB Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 20 (Tarte Cosmetics), NARS Pure Radiant Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 30 (NARS Cosmetics), and Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 30—were considered the best among consumers of all skin tones, with the addition of 2 different products (bareMinerals Original Liquid Mineral Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 [bareMinerals] and ILIA Super Serum Skin Tint SPF 40 Foundation [ILIA Beauty]) in the dark skin group. Notably, these products were the only ones on Sephora’s website that offered up to 30 (22 on average) different shades.

Comment

Tone Compatibility—Tinted sunscreens were created to extend the range of photoprotection into the VL spectrum. The goal of TSs is to incorporate pigments that blend in with the natural skin tone, produce a glow, and have an aesthetically pleasing appearance. To accommodate a variety of skin colors, different shades can be obtained by mixing different amounts of yellow, red, and black IO with or without PTD. The pigments and reflective compounds provide color, opacity, and a natural coverage. Our qualitative analysis provides information on the lack of diversity among shades available for TS, especially for darker skin tones. Of the 58 products evaluated, 62% (32/58) only had 1 shade. In our cohort, tone compatibility was the most commonly cited negative feature. Of note, 89% of these comments were from consumers with dark skin tones, and there was a disproportional number of reviews by darker-skinned individuals compared to users with light and medium skin tones. This is of particular importance, as TSs have been shown to protect against dermatoses that disproportionally affect individuals with skin of color. When comparing sunscreen formulations containing IO with regular mineral sunscreens, Dumbuya et al3 found that IO-containing formulations significantly protected against VL-induced pigmentation compared with untreated skin or mineral sunscreen with SPF 50 or higher in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type IV (P<.001). Similarly, Bernstein et al8 found that exposing patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV to blue-violet light resulted in marked hyperpigmentation that lasted up to 3 months. Visible light elicits immediate and persistent pigment darkening in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin phototype III and above via the photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin and de novo melanogenesis.9 Tinted sunscreens formulated with IO have been shown to aid in the treatment of melasma and prevent hyperpigmentation in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.10 Patients with darker skin tones with dermatoses aggravated or induced by VL, such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, may seek photoprotection provided by TS but find the lack of matching shades unappealing. The dearth of shade diversity that matches all skin tones can lead to inequities and disproportionally affect those with darker skin.

Performance—Tinted sunscreen formulations containing IO have been proven effective in protecting against high-energy VL, especially when combined synergistically with ZO.11 Kaye et al12 found that TSs containing IO and the inorganic filters TD or ZO reduced transmittance of VL more effectively than nontinted sunscreens containing TD or ZO alone or products containing organic filters. The decreased VL transmittance in the former is due to synergistic effects of the VL-scattering properties of the TD and the VL absorption properties of the IO. Similarly, Sayre et al13 demonstrated that IO was superior to TD and ZO in attenuating the transmission of VL. Bernstein et al14 found that darker shades containing higher percentages of IO increased the attenuation of VL to 98% compared with lighter shades attenuating 93%. This correlates with the results of prior studies highlighting the potential of TSs in protecting individuals with skin of color.3 In our cohort, comments regarding product performance and protection were mostly positive, claiming that consistent use reduced hyperpigmentation on the skin surface, giving the appearance of a more even skin tone.

Tolerability—Iron oxides are minerals known to be safe, gentle, and nontoxic on the surface of the skin.15 Two case reports of contact dermatitis due to IO have been reported.16,17 Within our cohort, only a few of the comments (6%) described negative product tolerance or compatibility with their skin type. However, it is more likely that these incompatibilities were due to other ingredients in the product or the individuals’ underlying dermatologic conditions.

Cosmetic Elegance—Most of the sunscreens available on the market today contain micronized forms of TD and ZO particles because they have better cosmetic acceptability.18 However, their reduced size compromises the protection provided against VL whereby the addition of IO is of vital importance. According to the RealSelf Sun Safety Report, only 11% of Americans wear sunscreen daily, and 46% never wear sunscreen.19 The most common reasons consumers reported for not wearing sunscreen included not liking how it looks on the skin, forgetting to apply it, and/or believing that application is inconvenient and time-consuming. Currently, TSs have been incorporated into daily-life products such as makeup, moisturizers, and serums, making application for users easy and convenient, decreasing the necessity of using multiple products, and offering the opportunity to choose from different presentations to make decisions for convenience and/or diverse occasions. Products containing IO blend in with the natural skin tone and have an aesthetically pleasing cosmetic appearance. In our cohort, comments regarding cosmetic elegance were highly valued and were present in multiple reviews (45%), with 69% being positive.

Affordability—In our cohort, product price was not predominantly mentioned in consumers’ reviews. However, negative comments regarding affordability were slightly higher than the positive (56% vs 44%). Notably, the mean price of our top recommendations was $42. Higher price was associated with products with a wider range of shades available. Prior studies have found similar results demonstrating that websites with recommendations on sunscreens for patients with skin of color compared with sunscreens for white or fair skin were more likely to recommend more expensive products (median, $14/oz vs $11.3/oz) despite the lower SPF level.20 According to Schneider,21 daily use of the cheapest sunscreen on the head/neck region recommended for white/pale skin ($2/oz) would lead to an annual cost of $61 compared to $182 for darker skin ($6/oz). This showcases the considerable variation in sunscreen prices for both populations that could potentiate disparities and vulnerability in the latter group.

Conclusion

Tinted sunscreens provide both functional and cosmetic benefits and are a safe, effective, and convenient way to protect against high-energy VL. This study suggests that patients with skin of color encounter difficulties in finding matching shades in TS products. These difficulties may stem from the lack of knowledge regarding dark complexions and undertones and the lack of representation of black and brown skin that has persisted in dermatology research journals and textbooks for decades.22 Our study provides important insights to help dermatologists improve their familiarity with the brands and characteristics of TSs geared to patients with all skin tones, including skin of color. Limitations include single-retailer information and inclusion of both highly and poorly rated comments with subjective data, limiting generalizability. The limited selection of shades for darker skin poses a roadblock to proper treatment and prevention. These data represent an area for improvement within the beauty industry and the dermatologic field to deliver culturally sensitive care by being knowledgeable about darker skin tones and TS formulations tailored to people with skin of color.

Sunscreen formulations typically protect from UV radiation (290–400 nm), as this is a well-established cause of photodamage, photoaging, and skin cancer.1 However, sunlight also consists of visible (400–700 nm) and infrared (>700 nm) radiation.2 In fact, UV radiation only comprises 5% to 7% of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the earth, while visible and infrared lights comprise 44% and 53%, respectively.3 Visible light (VL) is the only portion of the solar spectrum visible to the human eye; it penetrates the skin to a depth range of 90 to 750 µm compared to 1.5 to 90 µm for UV radiation.4 Visible light also may come from artificial sources such as light bulbs and digital screens. The rapidly increasing use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other digital screens that emit high levels of short-wavelength VL has increased concerns about the safety of these devices. Although blue light exposure from screens is small compared with the amount of exposure from the sun, there is concern about the long-term effects of excessive screen time. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to light emitted from electronic devices, even for as little as 1 hour, may cause reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, collagen degradation, and necrosis of skin cells.5 Visible light increases tyrosinase activity and induces immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.4,6

Sunscreens consist of chemical and mineral active ingredients that contain UV filters designed to absorb, scatter, and reflect UV photons with wavelengths up to 380 nm. Historically, traditional options do not protect against the effects induced by VL, as these sunscreens use nanosized particles that help to reduce the white appearance and result in transparency of the product.7 To block VL, the topical agent must be visible. Tinted sunscreens (TSs) are products that combine UV and VL filters. They give a colored base coverage that is achieved by incorporating a blend of black, red, and yellow iron oxides (IOs) and/or pigmentary titanium dioxide (PTD)(ie, titanium dioxide [TD] that is not nanosized). Because TSs offer an instant glow and protect the skin from both sun and artificial light, they have become increasingly popular and have been incorporated into makeup and skin care products to facilitate daily convenient use.

The purpose of this analysis was to study current available options and product factors that may influence consumer preference when choosing a TS based on the reviewer characteristics.

Methods

The keyword sunscreen was searched in the broader category of skin care products on an online supplier of sunscreens (www.sephora.com). This supplier was chosen because, unlike other sources, specific reviewer characteristics regarding underlying skin tone also were available. The search produced 161 results. For the purpose of this analysis, only facial TSs containing IO and/or PTD were included. Each sunscreen was checked by the authors, and 58 sunscreens that met the inclusion criteria were identified and further reviewed. Descriptive data, including formulation, sun protection factor (SPF), ingredient type (chemical or physical), pigments used, shades available, additional benefits, price range, rating, and user reviews, were gathered. The authors extracted these data from the product information on the website, manufacturer claims, ratings, and reviewer comments on each of the listed sunscreens.

For each product, the content of the top 10 most helpful positive and negative reviews as voted by consumers (1160 total reviews, consisting of 1 or more comments) was analyzed. Two authors (H.D.L.G. and P.V.) coded consumer-reported comments for positive and negative descriptors into the categories of cosmetic elegance, performance, skin compatibility and tolerance, tone compatibility, and affordability. Cosmetic elegance was defined as any feature associated with skin sensation (eg, greasy), color (eg, white cast), scent, ability to blend, and overall appearance of the product on the skin. Product performance included SPF, effectiveness in preventing sunburn, coverage, and finish claims (ie, matte, glow, invisible). Skin compatibility and tolerance were represented in the reviewers’ comments and reflected how the product performed in association with underlying dermatologic conditions, skin type, and if there were any side effects such as irritation or allergic reactions. Tone compatibility referred to TS color similarity with users’ skin and shades available for individual products. Affordability reflected consumers’ perceptions of the product price. Comments may be included in multiple categories (eg, a product was noted to blend well on the skin but did not provide enough coverage). Of entries, 10% (116/1160 reviews) were coded by first author (H.D.L.G.) to ensure internal validity. Reviewer characteristics were consistently available and were used to determine the top 5 recommended products for light-, medium-, and dark-skinned individuals based on the number of 5-star ratings in each group. Porcelain, fair, and light were considered light skin tones. Medium, tan, and olive were considered medium skin tones. Deep, dark, and ebony were considered dark skin tones.

Results

Sunscreen Characteristics—Among the 161 screened products, 58 met the inclusion criteria. Four types of formulations were included: lotion, cream, liquid, and powder. Twenty-nine (50%) were creams, followed by lotions (19%), liquids (28%), and powders (3%). More than 79% (46/58) of products had a reported SPF of 30 or higher. Sunscreens with an active physical ingredient—the minerals TD and/or zinc oxide (ZO)—were most common (33/58 [57%]), followed by the chemical sunscreens avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and/or octocrylene active ingredients (14/58 [24%]), and a combination of chemical and physical sunscreens (11/58 [19%]). Nearly all products (55/58 [95%]) contained pigmentary IO (red, CI 77491; yellow, CI 77492; black, CI 77499). Notably, only 38% (22/58) of products had more than 1 shade. All products had additional claims associated with being hydrating, having antiaging effects, smoothing texture, minimizing the appearance of pores, softening lines, and/or promoting even skin tone. Traditional physical sunscreens (those containing TD and/or ZO) were more expensive than chemical sunscreens, with a median price of $30. The median review rating was 4.5 of 5 stars, with a median of 2300 customer reviews per product. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

Positive Features of Sunscreens—Based on an analysis of total reviews (N=1160), cosmetic elegance was the most cited positive feature associated with TS products (31%), followed by product performance (10%). Skin compatibility and tolerance (7%), tone compatibility (7%), and affordability (7%) were cited less commonly as positive features. When negative features were cited, consumers mostly noted tone incompatibility (16%) and cosmetic elegance concerns (14%). Product performance (13%) was comparatively cited as a negative feature (Table 1). Exemplary positive comments categorized in cosmetic elegance included the subthemes of rubs in well and natural glow. Exemplary negative comments in cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility categories included the subthemes patchy/dry finish and color mismatch. Table 1 illustrates these findings.

Product Recommendations—The top 5 recommendations of the best TS for each skin tone are listed in Table 2. The mean price of the recommended products was $42 for 1 to 1.9 oz. Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20 (Laura Mercier) was the top product for all 3 groups. Similarly, of 58 products available, the same 5 products—Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20, IT Cosmetics CC+ Cream with SPF 50 (IT Cosmetics, LLC), Tarte Amazonian Clay BB Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 20 (Tarte Cosmetics), NARS Pure Radiant Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 30 (NARS Cosmetics), and Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 30—were considered the best among consumers of all skin tones, with the addition of 2 different products (bareMinerals Original Liquid Mineral Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 [bareMinerals] and ILIA Super Serum Skin Tint SPF 40 Foundation [ILIA Beauty]) in the dark skin group. Notably, these products were the only ones on Sephora’s website that offered up to 30 (22 on average) different shades.

Comment

Tone Compatibility—Tinted sunscreens were created to extend the range of photoprotection into the VL spectrum. The goal of TSs is to incorporate pigments that blend in with the natural skin tone, produce a glow, and have an aesthetically pleasing appearance. To accommodate a variety of skin colors, different shades can be obtained by mixing different amounts of yellow, red, and black IO with or without PTD. The pigments and reflective compounds provide color, opacity, and a natural coverage. Our qualitative analysis provides information on the lack of diversity among shades available for TS, especially for darker skin tones. Of the 58 products evaluated, 62% (32/58) only had 1 shade. In our cohort, tone compatibility was the most commonly cited negative feature. Of note, 89% of these comments were from consumers with dark skin tones, and there was a disproportional number of reviews by darker-skinned individuals compared to users with light and medium skin tones. This is of particular importance, as TSs have been shown to protect against dermatoses that disproportionally affect individuals with skin of color. When comparing sunscreen formulations containing IO with regular mineral sunscreens, Dumbuya et al3 found that IO-containing formulations significantly protected against VL-induced pigmentation compared with untreated skin or mineral sunscreen with SPF 50 or higher in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type IV (P<.001). Similarly, Bernstein et al8 found that exposing patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV to blue-violet light resulted in marked hyperpigmentation that lasted up to 3 months. Visible light elicits immediate and persistent pigment darkening in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin phototype III and above via the photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin and de novo melanogenesis.9 Tinted sunscreens formulated with IO have been shown to aid in the treatment of melasma and prevent hyperpigmentation in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.10 Patients with darker skin tones with dermatoses aggravated or induced by VL, such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, may seek photoprotection provided by TS but find the lack of matching shades unappealing. The dearth of shade diversity that matches all skin tones can lead to inequities and disproportionally affect those with darker skin.

Performance—Tinted sunscreen formulations containing IO have been proven effective in protecting against high-energy VL, especially when combined synergistically with ZO.11 Kaye et al12 found that TSs containing IO and the inorganic filters TD or ZO reduced transmittance of VL more effectively than nontinted sunscreens containing TD or ZO alone or products containing organic filters. The decreased VL transmittance in the former is due to synergistic effects of the VL-scattering properties of the TD and the VL absorption properties of the IO. Similarly, Sayre et al13 demonstrated that IO was superior to TD and ZO in attenuating the transmission of VL. Bernstein et al14 found that darker shades containing higher percentages of IO increased the attenuation of VL to 98% compared with lighter shades attenuating 93%. This correlates with the results of prior studies highlighting the potential of TSs in protecting individuals with skin of color.3 In our cohort, comments regarding product performance and protection were mostly positive, claiming that consistent use reduced hyperpigmentation on the skin surface, giving the appearance of a more even skin tone.

Tolerability—Iron oxides are minerals known to be safe, gentle, and nontoxic on the surface of the skin.15 Two case reports of contact dermatitis due to IO have been reported.16,17 Within our cohort, only a few of the comments (6%) described negative product tolerance or compatibility with their skin type. However, it is more likely that these incompatibilities were due to other ingredients in the product or the individuals’ underlying dermatologic conditions.

Cosmetic Elegance—Most of the sunscreens available on the market today contain micronized forms of TD and ZO particles because they have better cosmetic acceptability.18 However, their reduced size compromises the protection provided against VL whereby the addition of IO is of vital importance. According to the RealSelf Sun Safety Report, only 11% of Americans wear sunscreen daily, and 46% never wear sunscreen.19 The most common reasons consumers reported for not wearing sunscreen included not liking how it looks on the skin, forgetting to apply it, and/or believing that application is inconvenient and time-consuming. Currently, TSs have been incorporated into daily-life products such as makeup, moisturizers, and serums, making application for users easy and convenient, decreasing the necessity of using multiple products, and offering the opportunity to choose from different presentations to make decisions for convenience and/or diverse occasions. Products containing IO blend in with the natural skin tone and have an aesthetically pleasing cosmetic appearance. In our cohort, comments regarding cosmetic elegance were highly valued and were present in multiple reviews (45%), with 69% being positive.

Affordability—In our cohort, product price was not predominantly mentioned in consumers’ reviews. However, negative comments regarding affordability were slightly higher than the positive (56% vs 44%). Notably, the mean price of our top recommendations was $42. Higher price was associated with products with a wider range of shades available. Prior studies have found similar results demonstrating that websites with recommendations on sunscreens for patients with skin of color compared with sunscreens for white or fair skin were more likely to recommend more expensive products (median, $14/oz vs $11.3/oz) despite the lower SPF level.20 According to Schneider,21 daily use of the cheapest sunscreen on the head/neck region recommended for white/pale skin ($2/oz) would lead to an annual cost of $61 compared to $182 for darker skin ($6/oz). This showcases the considerable variation in sunscreen prices for both populations that could potentiate disparities and vulnerability in the latter group.

Conclusion

Tinted sunscreens provide both functional and cosmetic benefits and are a safe, effective, and convenient way to protect against high-energy VL. This study suggests that patients with skin of color encounter difficulties in finding matching shades in TS products. These difficulties may stem from the lack of knowledge regarding dark complexions and undertones and the lack of representation of black and brown skin that has persisted in dermatology research journals and textbooks for decades.22 Our study provides important insights to help dermatologists improve their familiarity with the brands and characteristics of TSs geared to patients with all skin tones, including skin of color. Limitations include single-retailer information and inclusion of both highly and poorly rated comments with subjective data, limiting generalizability. The limited selection of shades for darker skin poses a roadblock to proper treatment and prevention. These data represent an area for improvement within the beauty industry and the dermatologic field to deliver culturally sensitive care by being knowledgeable about darker skin tones and TS formulations tailored to people with skin of color.

- McDaniel D, Farris P, Valacchi G. Atmospheric skin aging-contributors and inhibitors. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:124-137.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Dumbuya H, Grimes PE, Lynch S, et al. Impact of iron-oxide containing formulations against visible light-induced skin pigmentation in skin of color individuals. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:712-717.

- Lyons AB, Trullas C, Kohli I, et al. Photoprotection beyond ultraviolet radiation: a review of tinted sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1393-1397.

- Austin E, Huang A, Adar T, et al. Electronic device generated light increases reactive oxygen species in human fibroblasts [published online February 5, 2018]. Lasers Surg Med. doi:10.1002/lsm.22794

- Randhawa M, Seo I, Liebel F, et al. Visible light induces melanogenesis in human skin through a photoadaptive response. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130949.

- Yeager DG, Lim HW. What’s new in photoprotection: a review of new concepts and controversies. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:149-157.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P. Iron oxides in novel skin care formulations attenuate blue light for enhanced protection against skin damage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:532-537.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Ruvolo E, Fair M, Hutson A, et al. Photoprotection against visible light-induced pigmentation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:589-595.

- Cohen L, Brodsky MA, Zubair R, et al. Cutaneous interaction with visible light: what do we know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30551-X.

- Kaye ET, Levin JA, Blank IH, et al. Efficiency of opaque photoprotective agents in the visible light range. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:351-355.

- Sayre RM, Kollias N, Roberts RL, et al. Physical sunscreens. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1990;41:103-109.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P, et al. Beyond sun protection factor: an approach to environmental protection with novel mineral coatings in a vehicle containing a blend of skincare ingredients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:407-415.

- MacLeman E. Why are iron oxides used? Deep Science website. February 10, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://thedermreview.com/iron-oxides-ci-77491-ci-77492-ci-77499/

- Zugerman C. Contact dermatitis to yellow iron oxide. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:107-109.

- Saxena M, Warshaw E, Ahmed DD. Eyelid allergic contact dermatitis to black iron oxide. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:38-39.

- Smijs TG, Pavel S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2011;4:95-112.

- 2020 RealSelf Sun Safety Report: majority of Americans don’t use sunscreen daily. Practical Dermatology. May 6, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://practicaldermatology.com/news/realself-sun-safety-report-majority-of-americans-dont-use-sunscreen-daily

- Song H, Beckles A, Salian P, et al. Sunscreen recommendations for patients with skin of color in the popular press and in the dermatology clinic. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:165-170.

- Schneider J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Nelson B. How dermatology is failing melanoma patients with skin of color: unanswered questions on risk and eye-opening disparities in outcomes are weighing heavily on melanoma patients with darker skin. in this article, part 1 of a 2-part series, we explore the deadly consequences of racism and inequality in cancer care. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128:7-8.

- McDaniel D, Farris P, Valacchi G. Atmospheric skin aging-contributors and inhibitors. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:124-137.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Dumbuya H, Grimes PE, Lynch S, et al. Impact of iron-oxide containing formulations against visible light-induced skin pigmentation in skin of color individuals. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:712-717.

- Lyons AB, Trullas C, Kohli I, et al. Photoprotection beyond ultraviolet radiation: a review of tinted sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1393-1397.

- Austin E, Huang A, Adar T, et al. Electronic device generated light increases reactive oxygen species in human fibroblasts [published online February 5, 2018]. Lasers Surg Med. doi:10.1002/lsm.22794

- Randhawa M, Seo I, Liebel F, et al. Visible light induces melanogenesis in human skin through a photoadaptive response. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130949.

- Yeager DG, Lim HW. What’s new in photoprotection: a review of new concepts and controversies. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:149-157.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P. Iron oxides in novel skin care formulations attenuate blue light for enhanced protection against skin damage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:532-537.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Ruvolo E, Fair M, Hutson A, et al. Photoprotection against visible light-induced pigmentation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:589-595.

- Cohen L, Brodsky MA, Zubair R, et al. Cutaneous interaction with visible light: what do we know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30551-X.

- Kaye ET, Levin JA, Blank IH, et al. Efficiency of opaque photoprotective agents in the visible light range. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:351-355.

- Sayre RM, Kollias N, Roberts RL, et al. Physical sunscreens. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1990;41:103-109.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P, et al. Beyond sun protection factor: an approach to environmental protection with novel mineral coatings in a vehicle containing a blend of skincare ingredients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:407-415.

- MacLeman E. Why are iron oxides used? Deep Science website. February 10, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://thedermreview.com/iron-oxides-ci-77491-ci-77492-ci-77499/

- Zugerman C. Contact dermatitis to yellow iron oxide. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:107-109.

- Saxena M, Warshaw E, Ahmed DD. Eyelid allergic contact dermatitis to black iron oxide. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:38-39.

- Smijs TG, Pavel S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2011;4:95-112.

- 2020 RealSelf Sun Safety Report: majority of Americans don’t use sunscreen daily. Practical Dermatology. May 6, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://practicaldermatology.com/news/realself-sun-safety-report-majority-of-americans-dont-use-sunscreen-daily

- Song H, Beckles A, Salian P, et al. Sunscreen recommendations for patients with skin of color in the popular press and in the dermatology clinic. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:165-170.

- Schneider J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Nelson B. How dermatology is failing melanoma patients with skin of color: unanswered questions on risk and eye-opening disparities in outcomes are weighing heavily on melanoma patients with darker skin. in this article, part 1 of a 2-part series, we explore the deadly consequences of racism and inequality in cancer care. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128:7-8.

Practice Points

- Visible light has been shown to increase tyrosinase activity and induce immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.

- The formulation of sunscreens with iron oxides and pigmentary titanium dioxide are a safe and effective way to protect against high-energy visible light, especially when combined with zinc oxide.

- Physicians should be aware of sunscreen characteristics that patients like and dislike to tailor recommendations that are appropriate for each individual to enhance adherence.

- Cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility are the most important criteria for individuals seeking tinted sunscreens.

Photoprotection strategies for melasma are increasing

BOSTON – Untinted chemical sunscreens on the market are not sufficient to protect the skin from the effects of visible light, complicating sun protection efforts for patients with melasma and other conditions aggravated by sun exposure, according to Henry W. Lim, MD.

A , Dr. Lim, former chair of the department of dermatology at Henry Ford Health, Detroit, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Tinted sunscreens contain iron oxides; some also contain pigmentary titanium dioxide.

“Black, red, and yellow iron oxide all reflect visible light,” he added, noting that currently, there are no regulations as to how tinted sunscreens are marketed, making it difficult for practicing clinicians to advise patients about what products to choose. However, he said, “unlike ‘SPF’ and ‘broad spectrum’ labeling, there is no specific guidance on tinted sunscreens. “ ‘Universal’ shade is a good start but might not be ideal for users with very fair or deep skin tones,” he noted.

In December 2021, a guide to tinted sunscreens, written by Dr. Lim and colleagues, was published, recommending that consumers choose a product that contains iron oxides, is labeled as broad spectrum, and has an SPF of at least 30.

A comprehensive list of 54 tinted sunscreens with an SPF of 30 or greater that contain iron oxide is also available . The authors of the guide contributed to this resource, which lists sunscreens by average price per ounce.

At the meeting, Dr. Lim highlighted tinted sunscreens that cost about $20 or less per ounce. They include Supergoop 100% Mineral CC Cream (SPF 50); Bare Republic Mineral Tinted Face Sunscreen Lotion (SPF 30); CeraVe Hydrating Sunscreen with Sheer Tint (SPF 30); Tizo Ultra Zinc Body & Face Sunscreen (SPF 40); Vichy Capital Soleil Tinted Face Mineral Sunscreen (SPF 60); EltaMD UV Elements Tinted (SPF 44); La Roche-Posay Anthelios Ultra-Light Tinted Mineral (SPF 50), SkinMedica Essential Defense Mineral Shield (SPF 32), ISDIN Eryfotona Ageless Ultralight Tinted Mineral Sunscreen (SPF 50), and SkinCeuticals Physical Fusion UV Defense (SPF 50).

Sunscreens with antioxidants

Sunscreens with biologically active antioxidants may be another option for patients with melasma. A proof-of-concept study that Dr. Lim and colleagues conducted in 20 patients found that application of a blend of topical antioxidants (2%) was associated with less erythema at the application sites among those with skin phototypes I-III and less pigmentation at the application sites among those with skin phototypes IV-VI after exposure to visible light and UVA-1, compared with controls.

Certain antioxidants have been added to sunscreens currently on the market, including niacinamide (vitamin B3), licochalcone A, carotenoids (beta-carotene), vitamin E, vitamin C, glycyrrhetinic acid, and diethylhexyl syringylidenemalonate.

A recently published paper on the role of antioxidants and free radical quenchers in protecting skin from visible light referred to unpublished data from Dr. Lim (the first author) and colleagues, which demonstrated a significant reduction in visual light–induced hyperpigmentation on skin with sunscreen that contained the antioxidants vitamin E, vitamin C, diethylhexyl syringylidenemalonate, licochalcone A, and a glycyrrhetinic acid, compared with sunscreen that had no antioxidants.

Novel filters

Another emerging option is sunscreen with new filters that cover UVA-1 and visible light. In a randomized, controlled trial of 19 patients, researchers evaluated the addition of methoxypropylamino cyclohexenylidene ethoxyethylcyanoacetate (MCE) absorber, a new UVA-1 filter known as Mexoryl 400, which has a peak absorption of 385 nm, to a sunscreen formulation.

“Currently, peak absorption in the U.S. is with avobenzone, which peaks at about 357 nm,” but MCE “covers a longer spectrum of UVA-1,” Dr. Lim said. The researchers found that the addition of MCE reduced UVA-1-induced dermal and epidermal alterations at cellular, biochemical, and molecular levels; and decreased UVA-1-induced pigmentation.

Another relatively new filter, phenylene bis-diphenyltriazine (also known as TriAsorB) not only protects against UVA but it extends into the blue light portion of visible light, according to a recently published paper. According to a press release from Pierre Fabre, which has developed the filter, studies have shown that TriAsorB is not toxic for three key species of marine biodiversity: a coral species, a phytoplankton species, and a zooplankton.

This filter and MCE are available in Europe but not in the United States.

Dr. Lim reported that he is an investigator for Incyte, L’Oréal, Pfizer, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

BOSTON – Untinted chemical sunscreens on the market are not sufficient to protect the skin from the effects of visible light, complicating sun protection efforts for patients with melasma and other conditions aggravated by sun exposure, according to Henry W. Lim, MD.

A , Dr. Lim, former chair of the department of dermatology at Henry Ford Health, Detroit, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Tinted sunscreens contain iron oxides; some also contain pigmentary titanium dioxide.

“Black, red, and yellow iron oxide all reflect visible light,” he added, noting that currently, there are no regulations as to how tinted sunscreens are marketed, making it difficult for practicing clinicians to advise patients about what products to choose. However, he said, “unlike ‘SPF’ and ‘broad spectrum’ labeling, there is no specific guidance on tinted sunscreens. “ ‘Universal’ shade is a good start but might not be ideal for users with very fair or deep skin tones,” he noted.

In December 2021, a guide to tinted sunscreens, written by Dr. Lim and colleagues, was published, recommending that consumers choose a product that contains iron oxides, is labeled as broad spectrum, and has an SPF of at least 30.

A comprehensive list of 54 tinted sunscreens with an SPF of 30 or greater that contain iron oxide is also available . The authors of the guide contributed to this resource, which lists sunscreens by average price per ounce.

At the meeting, Dr. Lim highlighted tinted sunscreens that cost about $20 or less per ounce. They include Supergoop 100% Mineral CC Cream (SPF 50); Bare Republic Mineral Tinted Face Sunscreen Lotion (SPF 30); CeraVe Hydrating Sunscreen with Sheer Tint (SPF 30); Tizo Ultra Zinc Body & Face Sunscreen (SPF 40); Vichy Capital Soleil Tinted Face Mineral Sunscreen (SPF 60); EltaMD UV Elements Tinted (SPF 44); La Roche-Posay Anthelios Ultra-Light Tinted Mineral (SPF 50), SkinMedica Essential Defense Mineral Shield (SPF 32), ISDIN Eryfotona Ageless Ultralight Tinted Mineral Sunscreen (SPF 50), and SkinCeuticals Physical Fusion UV Defense (SPF 50).

Sunscreens with antioxidants

Sunscreens with biologically active antioxidants may be another option for patients with melasma. A proof-of-concept study that Dr. Lim and colleagues conducted in 20 patients found that application of a blend of topical antioxidants (2%) was associated with less erythema at the application sites among those with skin phototypes I-III and less pigmentation at the application sites among those with skin phototypes IV-VI after exposure to visible light and UVA-1, compared with controls.

Certain antioxidants have been added to sunscreens currently on the market, including niacinamide (vitamin B3), licochalcone A, carotenoids (beta-carotene), vitamin E, vitamin C, glycyrrhetinic acid, and diethylhexyl syringylidenemalonate.

A recently published paper on the role of antioxidants and free radical quenchers in protecting skin from visible light referred to unpublished data from Dr. Lim (the first author) and colleagues, which demonstrated a significant reduction in visual light–induced hyperpigmentation on skin with sunscreen that contained the antioxidants vitamin E, vitamin C, diethylhexyl syringylidenemalonate, licochalcone A, and a glycyrrhetinic acid, compared with sunscreen that had no antioxidants.

Novel filters

Another emerging option is sunscreen with new filters that cover UVA-1 and visible light. In a randomized, controlled trial of 19 patients, researchers evaluated the addition of methoxypropylamino cyclohexenylidene ethoxyethylcyanoacetate (MCE) absorber, a new UVA-1 filter known as Mexoryl 400, which has a peak absorption of 385 nm, to a sunscreen formulation.

“Currently, peak absorption in the U.S. is with avobenzone, which peaks at about 357 nm,” but MCE “covers a longer spectrum of UVA-1,” Dr. Lim said. The researchers found that the addition of MCE reduced UVA-1-induced dermal and epidermal alterations at cellular, biochemical, and molecular levels; and decreased UVA-1-induced pigmentation.

Another relatively new filter, phenylene bis-diphenyltriazine (also known as TriAsorB) not only protects against UVA but it extends into the blue light portion of visible light, according to a recently published paper. According to a press release from Pierre Fabre, which has developed the filter, studies have shown that TriAsorB is not toxic for three key species of marine biodiversity: a coral species, a phytoplankton species, and a zooplankton.

This filter and MCE are available in Europe but not in the United States.

Dr. Lim reported that he is an investigator for Incyte, L’Oréal, Pfizer, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

BOSTON – Untinted chemical sunscreens on the market are not sufficient to protect the skin from the effects of visible light, complicating sun protection efforts for patients with melasma and other conditions aggravated by sun exposure, according to Henry W. Lim, MD.

A , Dr. Lim, former chair of the department of dermatology at Henry Ford Health, Detroit, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. Tinted sunscreens contain iron oxides; some also contain pigmentary titanium dioxide.

“Black, red, and yellow iron oxide all reflect visible light,” he added, noting that currently, there are no regulations as to how tinted sunscreens are marketed, making it difficult for practicing clinicians to advise patients about what products to choose. However, he said, “unlike ‘SPF’ and ‘broad spectrum’ labeling, there is no specific guidance on tinted sunscreens. “ ‘Universal’ shade is a good start but might not be ideal for users with very fair or deep skin tones,” he noted.

In December 2021, a guide to tinted sunscreens, written by Dr. Lim and colleagues, was published, recommending that consumers choose a product that contains iron oxides, is labeled as broad spectrum, and has an SPF of at least 30.

A comprehensive list of 54 tinted sunscreens with an SPF of 30 or greater that contain iron oxide is also available . The authors of the guide contributed to this resource, which lists sunscreens by average price per ounce.

At the meeting, Dr. Lim highlighted tinted sunscreens that cost about $20 or less per ounce. They include Supergoop 100% Mineral CC Cream (SPF 50); Bare Republic Mineral Tinted Face Sunscreen Lotion (SPF 30); CeraVe Hydrating Sunscreen with Sheer Tint (SPF 30); Tizo Ultra Zinc Body & Face Sunscreen (SPF 40); Vichy Capital Soleil Tinted Face Mineral Sunscreen (SPF 60); EltaMD UV Elements Tinted (SPF 44); La Roche-Posay Anthelios Ultra-Light Tinted Mineral (SPF 50), SkinMedica Essential Defense Mineral Shield (SPF 32), ISDIN Eryfotona Ageless Ultralight Tinted Mineral Sunscreen (SPF 50), and SkinCeuticals Physical Fusion UV Defense (SPF 50).

Sunscreens with antioxidants

Sunscreens with biologically active antioxidants may be another option for patients with melasma. A proof-of-concept study that Dr. Lim and colleagues conducted in 20 patients found that application of a blend of topical antioxidants (2%) was associated with less erythema at the application sites among those with skin phototypes I-III and less pigmentation at the application sites among those with skin phototypes IV-VI after exposure to visible light and UVA-1, compared with controls.

Certain antioxidants have been added to sunscreens currently on the market, including niacinamide (vitamin B3), licochalcone A, carotenoids (beta-carotene), vitamin E, vitamin C, glycyrrhetinic acid, and diethylhexyl syringylidenemalonate.

A recently published paper on the role of antioxidants and free radical quenchers in protecting skin from visible light referred to unpublished data from Dr. Lim (the first author) and colleagues, which demonstrated a significant reduction in visual light–induced hyperpigmentation on skin with sunscreen that contained the antioxidants vitamin E, vitamin C, diethylhexyl syringylidenemalonate, licochalcone A, and a glycyrrhetinic acid, compared with sunscreen that had no antioxidants.

Novel filters

Another emerging option is sunscreen with new filters that cover UVA-1 and visible light. In a randomized, controlled trial of 19 patients, researchers evaluated the addition of methoxypropylamino cyclohexenylidene ethoxyethylcyanoacetate (MCE) absorber, a new UVA-1 filter known as Mexoryl 400, which has a peak absorption of 385 nm, to a sunscreen formulation.

“Currently, peak absorption in the U.S. is with avobenzone, which peaks at about 357 nm,” but MCE “covers a longer spectrum of UVA-1,” Dr. Lim said. The researchers found that the addition of MCE reduced UVA-1-induced dermal and epidermal alterations at cellular, biochemical, and molecular levels; and decreased UVA-1-induced pigmentation.

Another relatively new filter, phenylene bis-diphenyltriazine (also known as TriAsorB) not only protects against UVA but it extends into the blue light portion of visible light, according to a recently published paper. According to a press release from Pierre Fabre, which has developed the filter, studies have shown that TriAsorB is not toxic for three key species of marine biodiversity: a coral species, a phytoplankton species, and a zooplankton.

This filter and MCE are available in Europe but not in the United States.

Dr. Lim reported that he is an investigator for Incyte, L’Oréal, Pfizer, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

AT AAD 22

Topical options for treating melasma continue to expand

BOSTON – In the opinion of Seemal R. Desai, MD, dermatologists are obligated to tell their patients with melasma that their condition is a chronic disease with no cure.

“We have to set expectations upfront, because you all know the history,” Dr. Desai, founder and medical director of Innovative Dermatology in Dallas, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “You get someone better, their melasma gets lighter, and then they’re lost to follow-up for a year. Then they’re back to your office after that beach vacation because their melasma has come back with a vengeance because they were out in the sun too much. We have to tell our patients that melasma therapy is a journey of skin lightening but it’s not going to be a one-stop shop of getting it completely cured.”

As for treatment of melasma, “hydroquinone is still our workhorse, our gold standard.” Dr. Desai said. “I tell patients, ‘I’m going to keep you on it for 16 weeks. Then you’re going to come back. I’m going to see where you are, and we’ll move into the nonhydroquinone therapies once your disease is under control.’ ”

However, new therapies for melasma are needed because long-term use of hydroquinone can lead to complications such as ochronosis, nail discoloration, conjunctival melanosis, and corneal degeneration.

Emerging treatments

. Dr. Desai described azelaic acid as his “go to” nonhydroquinone option for skin lightening. In one study, 20% azelaic acid was used twice daily in 155 patients with facial melasma. Of these, 73% showed improvement after 6 months of therapy. Side effects were minimal and included erythema, pruritus, and burning.

Another option is topically compounded methimazole, a potent peroxidase inhibitor that causes morphologic change in melanocytes. “You can get it compounded as a 5% cream,” he said of the antithyroid agent. “It’s not that expensive, and even high concentrations are not melanocytotoxic. There’s minimal systemic absorption because the molecule is large, so there really is not any effect on TSH [thyroid-stimulating hormone] or T4 levels.”

Kojic acid dipalmitate, an antibiotic produced by many species of Aspergillus and Penicillium, can also be used as a second-line melasma treatment. Unlike kojic acid, kojic acid dipalmitate is more stable to light, heat, pH, and oxidation, and is also compatible with most organic sunscreens. It works by inhibiting tyrosinase. “It’s already available overseas and will soon be available in the U.S. as a derivative of kojic acid,” he said.

There is also vitamin C serum, which reduces tyrosinase activity via an antioxidant effect. “When you combine it with azelaic acid or sunscreen, vitamin C helps to augment the response,” Dr. Desai said. In one study that compared 5% ascorbic acid with 4% hydroquinone, 62.5% vs. 93% of patients improved, respectively, but side effects were more prominent in those who received 4% hydroquinone (68.7% vs. 6.2%).

An additional off-label option for melasma is oral tranexamic acid, which controls pigmentation by inhibiting the release of inflammatory mediators, specifically prostaglandins and arachidonic acid, which are involved in melanogenesis.

Dr. Desai often uses a dose of 325 mg twice daily. “Think of tranexamic acid as an anti-inflammatory,” he said. Tranexamic acid is contraindicated in patients who are currently taking or have previously taken anticoagulant medications; those who are pregnant or breastfeeding, or are smokers; and in those with renal, cardiac, and/or pulmonary disease. It has a half-life of about 7.5 hours, so the twice daily dosing “is quite effective,” he said.

“Do I leave my patients on this for years at a time to see if it’s going to work? No. When this works in treating melasma it works very quickly. I tell patients they’re going to see results in the first 8-12 weeks. That’s the beauty of using this orally.”