User login

Pandemic tied to misdiagnosis of rare pneumonia

Psittacosis, a rare disease, has been underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic, likely because the symptoms of the disease are similar to COVID-19 symptoms, researchers suggest on the basis of data from 32 individuals.

Diagnosis of and screening for COVID-19 continues to increase; however, cases of atypical pneumonia caused by uncommon pathogens, which presents with similar symptoms, may be missed, wrote Qiaoqiao Yin, MS, of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, China, and colleagues.

“The clinical manifestations of human psittacosis can present as rapidly progressing severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and multiple organ failure,” but human cases have not been well studied, they say.

In a study published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, the researchers reviewed data from 32 adults diagnosed with Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia during the COVID-19 pandemic between April 2020 and June 2021 in China. The median age of the patients was 63 years, 20 were men, and 20 had underlying diseases.

A total of 17 patients presented with fever, cough, and expectoration of yellow-white sputum. At the time of hospital admission, three patients had myalgia, two had headache, and two had hypertension. The patients were originally suspected of having COVID-19.

all of which could be observed in COVID-19 patients as well, the researchers wrote.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing were used to rule out COVID-19. The researchers then used metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) to identify the disease-causing pathogens. They collected 18 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples, 9 peripheral blood samples, and 5 sputum samples. The mNGS identified C. psittaci as the suspected pathogen within 48 hours. Suspected C. psittaci infections were confirmed by endpoint PCR for the BALF and sputum samples and six of nine blood samples, “indicating a lower sensitivity of PCR compared to mNGS for blood samples,” the researchers say. No other potential pathogens were identified.

Psittacosis is common in birds but is rare in humans. C. psittaci is responsible for 1%-8% of cases involving community-acquired pneumonia in China, the researchers note. Although poultry is a source of infection, 25 of the patients in the study did not report a history of exposure to poultry or pigeons at the time of their initial hospital admission. Many patients may be unaware of exposures to poultry, which further complicates the C. psittaci diagnosis, they note.

All patients were treated with doxycycline-based regimens and showed improvement.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of a definitive diagnostic tool for C. psittaci and the lack of convalescent serum samples to confirm cases, the researchers note. In addition, molecular detections for PCR are unavailable in most hospitals in China, they say. The results represent the largest known collection of suspected C. psittaci pneumonia cases and highlight the need for clinician vigilance and awareness of this rare condition, especially in light of the potential for misdiagnosis during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, they conclude.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Psittacosis, a rare disease, has been underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic, likely because the symptoms of the disease are similar to COVID-19 symptoms, researchers suggest on the basis of data from 32 individuals.

Diagnosis of and screening for COVID-19 continues to increase; however, cases of atypical pneumonia caused by uncommon pathogens, which presents with similar symptoms, may be missed, wrote Qiaoqiao Yin, MS, of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, China, and colleagues.

“The clinical manifestations of human psittacosis can present as rapidly progressing severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and multiple organ failure,” but human cases have not been well studied, they say.

In a study published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, the researchers reviewed data from 32 adults diagnosed with Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia during the COVID-19 pandemic between April 2020 and June 2021 in China. The median age of the patients was 63 years, 20 were men, and 20 had underlying diseases.

A total of 17 patients presented with fever, cough, and expectoration of yellow-white sputum. At the time of hospital admission, three patients had myalgia, two had headache, and two had hypertension. The patients were originally suspected of having COVID-19.

all of which could be observed in COVID-19 patients as well, the researchers wrote.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing were used to rule out COVID-19. The researchers then used metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) to identify the disease-causing pathogens. They collected 18 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples, 9 peripheral blood samples, and 5 sputum samples. The mNGS identified C. psittaci as the suspected pathogen within 48 hours. Suspected C. psittaci infections were confirmed by endpoint PCR for the BALF and sputum samples and six of nine blood samples, “indicating a lower sensitivity of PCR compared to mNGS for blood samples,” the researchers say. No other potential pathogens were identified.

Psittacosis is common in birds but is rare in humans. C. psittaci is responsible for 1%-8% of cases involving community-acquired pneumonia in China, the researchers note. Although poultry is a source of infection, 25 of the patients in the study did not report a history of exposure to poultry or pigeons at the time of their initial hospital admission. Many patients may be unaware of exposures to poultry, which further complicates the C. psittaci diagnosis, they note.

All patients were treated with doxycycline-based regimens and showed improvement.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of a definitive diagnostic tool for C. psittaci and the lack of convalescent serum samples to confirm cases, the researchers note. In addition, molecular detections for PCR are unavailable in most hospitals in China, they say. The results represent the largest known collection of suspected C. psittaci pneumonia cases and highlight the need for clinician vigilance and awareness of this rare condition, especially in light of the potential for misdiagnosis during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, they conclude.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Psittacosis, a rare disease, has been underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic, likely because the symptoms of the disease are similar to COVID-19 symptoms, researchers suggest on the basis of data from 32 individuals.

Diagnosis of and screening for COVID-19 continues to increase; however, cases of atypical pneumonia caused by uncommon pathogens, which presents with similar symptoms, may be missed, wrote Qiaoqiao Yin, MS, of Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, China, and colleagues.

“The clinical manifestations of human psittacosis can present as rapidly progressing severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and multiple organ failure,” but human cases have not been well studied, they say.

In a study published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, the researchers reviewed data from 32 adults diagnosed with Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia during the COVID-19 pandemic between April 2020 and June 2021 in China. The median age of the patients was 63 years, 20 were men, and 20 had underlying diseases.

A total of 17 patients presented with fever, cough, and expectoration of yellow-white sputum. At the time of hospital admission, three patients had myalgia, two had headache, and two had hypertension. The patients were originally suspected of having COVID-19.

all of which could be observed in COVID-19 patients as well, the researchers wrote.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing were used to rule out COVID-19. The researchers then used metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) to identify the disease-causing pathogens. They collected 18 bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples, 9 peripheral blood samples, and 5 sputum samples. The mNGS identified C. psittaci as the suspected pathogen within 48 hours. Suspected C. psittaci infections were confirmed by endpoint PCR for the BALF and sputum samples and six of nine blood samples, “indicating a lower sensitivity of PCR compared to mNGS for blood samples,” the researchers say. No other potential pathogens were identified.

Psittacosis is common in birds but is rare in humans. C. psittaci is responsible for 1%-8% of cases involving community-acquired pneumonia in China, the researchers note. Although poultry is a source of infection, 25 of the patients in the study did not report a history of exposure to poultry or pigeons at the time of their initial hospital admission. Many patients may be unaware of exposures to poultry, which further complicates the C. psittaci diagnosis, they note.

All patients were treated with doxycycline-based regimens and showed improvement.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of a definitive diagnostic tool for C. psittaci and the lack of convalescent serum samples to confirm cases, the researchers note. In addition, molecular detections for PCR are unavailable in most hospitals in China, they say. The results represent the largest known collection of suspected C. psittaci pneumonia cases and highlight the need for clinician vigilance and awareness of this rare condition, especially in light of the potential for misdiagnosis during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, they conclude.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

FDA approves belimumab for children with lupus nephritis

The Food and Drug Administration has approved belimumab (Benlysta) for treating active lupus nephritis (LN) in children aged 5-17 years. The drug can now be used to treat adult and pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and LN. The decision expands therapeutic options for the estimated 1.5 million Americans currently living with lupus.

“This approval marks a significant step forward in providing treatment options to these children at risk of incurring kidney damage early on in life,” Stevan W. Gibson, president and CEO of the Lupus Foundation of America, said in a press release issued by the manufacturer, GlaxoSmithKline. LN is a condition that sometimes develops in people with lupus. In LN, the autoimmune cells produced by the disease attack the kidney. Roughly 40% of people with SLE experience LN.

Damage to the kidneys causes the body to have difficulty processing waste and toxins. This can create a host of problems, including end-stage kidney disease, which may be treated only with dialysis or kidney transplant. These situations significantly increase mortality among people with lupus, especially children.

Prior to the approval, the only treatment pathway for children with active LN included immunosuppressants and corticosteroids. While they may be effective, use of these classes of drugs may come with many side effects, including susceptibility to other diseases and infections. Belimumab, by contrast, is a B-lymphocyte stimulator protein inhibitor. It inhibits the survival of B cells, which are thought to play a role in the disease’s pathophysiology.

Belimumab was first approved to treat patients with SLE in 2011. It was approved for children with SLE 8 years later. The drug’s indications were expanded to include adults with LN in 2020.

Organizations within the lupus research community have communicated their support of the FDA’s decision. “Our community has much to celebrate with the approval of the first and much-needed treatment for children with lupus nephritis,” Lupus Research Alliance President and CEO Kenneth M. Farber said in a release from the organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved belimumab (Benlysta) for treating active lupus nephritis (LN) in children aged 5-17 years. The drug can now be used to treat adult and pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and LN. The decision expands therapeutic options for the estimated 1.5 million Americans currently living with lupus.

“This approval marks a significant step forward in providing treatment options to these children at risk of incurring kidney damage early on in life,” Stevan W. Gibson, president and CEO of the Lupus Foundation of America, said in a press release issued by the manufacturer, GlaxoSmithKline. LN is a condition that sometimes develops in people with lupus. In LN, the autoimmune cells produced by the disease attack the kidney. Roughly 40% of people with SLE experience LN.

Damage to the kidneys causes the body to have difficulty processing waste and toxins. This can create a host of problems, including end-stage kidney disease, which may be treated only with dialysis or kidney transplant. These situations significantly increase mortality among people with lupus, especially children.

Prior to the approval, the only treatment pathway for children with active LN included immunosuppressants and corticosteroids. While they may be effective, use of these classes of drugs may come with many side effects, including susceptibility to other diseases and infections. Belimumab, by contrast, is a B-lymphocyte stimulator protein inhibitor. It inhibits the survival of B cells, which are thought to play a role in the disease’s pathophysiology.

Belimumab was first approved to treat patients with SLE in 2011. It was approved for children with SLE 8 years later. The drug’s indications were expanded to include adults with LN in 2020.

Organizations within the lupus research community have communicated their support of the FDA’s decision. “Our community has much to celebrate with the approval of the first and much-needed treatment for children with lupus nephritis,” Lupus Research Alliance President and CEO Kenneth M. Farber said in a release from the organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved belimumab (Benlysta) for treating active lupus nephritis (LN) in children aged 5-17 years. The drug can now be used to treat adult and pediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and LN. The decision expands therapeutic options for the estimated 1.5 million Americans currently living with lupus.

“This approval marks a significant step forward in providing treatment options to these children at risk of incurring kidney damage early on in life,” Stevan W. Gibson, president and CEO of the Lupus Foundation of America, said in a press release issued by the manufacturer, GlaxoSmithKline. LN is a condition that sometimes develops in people with lupus. In LN, the autoimmune cells produced by the disease attack the kidney. Roughly 40% of people with SLE experience LN.

Damage to the kidneys causes the body to have difficulty processing waste and toxins. This can create a host of problems, including end-stage kidney disease, which may be treated only with dialysis or kidney transplant. These situations significantly increase mortality among people with lupus, especially children.

Prior to the approval, the only treatment pathway for children with active LN included immunosuppressants and corticosteroids. While they may be effective, use of these classes of drugs may come with many side effects, including susceptibility to other diseases and infections. Belimumab, by contrast, is a B-lymphocyte stimulator protein inhibitor. It inhibits the survival of B cells, which are thought to play a role in the disease’s pathophysiology.

Belimumab was first approved to treat patients with SLE in 2011. It was approved for children with SLE 8 years later. The drug’s indications were expanded to include adults with LN in 2020.

Organizations within the lupus research community have communicated their support of the FDA’s decision. “Our community has much to celebrate with the approval of the first and much-needed treatment for children with lupus nephritis,” Lupus Research Alliance President and CEO Kenneth M. Farber said in a release from the organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Peristomal Pyoderma Gangrenosum at an Ileostomy Site

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

To the Editor:

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare entity first described in 1984.1 Lesions usually begin as pustules that coalesce into an erythematous skin ulceration that contains purulent material. The lesion appears on the skin that surrounds an abdominal stoma. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically is associated with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, cancer, blood dyscrasia, diabetes mellitus, and hepatitis.2 We describe a case of PPG following an ileostomy in a patient with colon cancer and a related history of Crohn disease.

A 32-year-old woman presented to a dermatology office with a spontaneously painful, 3.2-cm ulceration that was extremely tender to palpation, located immediately adjacent to the site of an ileostomy (Figure). The patient had a history of refractory constipation that failed to respond to standard conservative measures 4 years prior. She underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed a 6.5-cm, irregularly shaped, exophytic mass in the rectosigmoid portion of the colon. Histopathologic examination of several biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of moderately well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, and additional evaluation determined the cancer to be stage IIB. She had a medical history of pancolonic Crohn disease since high school that was treated with periodic infusions of infliximab at the standard dose of 5 mg/kg. Colon cancer treatment consisted of preoperative radiotherapy, complete colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis, and creation of a J-pouch and formation of a temporary ileostomy, along with postoperative capecitabine chemotherapy.

The ileostomy eventually was reversed, and the patient did well for 3 years. When the patient developed severe abdominal pain, the J-pouch was examined and found to be remarkably involved with Crohn disease. However, during the colonoscopy, the J-pouch was inadvertently punctured, leading to the formation of a large pelvic abscess. The latter necessitated diversion of stool, and the patient had the original ileostomy recreated.

Prior to presentation to dermatology, various consultants suspected the ulceration was possibly a deep fungal infection, cutaneous Crohn disease, a factitious ulceration, or acute allergic contact dermatitis related to some element of ostomy care. However, dermatologic consultation suggested that the troublesome lesion was classic PPG and recommended administration of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α–blocking agent and concomitant intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide.

The patient was treated with subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg once weekly, and received near weekly subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL. After 2 months, the discomfort subsided, and the ulceration gradually resolved into a depressed scar. Eighteen months later, the scar was barely perceptible as a minimally erythematous depression. Adalimumab ultimately was discontinued, as the residual J-pouch was removed, and the biologic drug was associated with extensive alopecia areata–like hair loss. There has been no recurrence of PPG in the 40 months since clinical resolution.

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is an uncommon subtype of pyoderma gangrenosum, which is characterized by chronic, persistent, or recurrent painful ulceration(s) close to an abdominal stoma. In total, fewer than 100 cases of PPG have been reported thus far in the readily available medical literature.3 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the most frequently diagnosed systemic condition associated with PPG, though other associated conditions include diverticular disease, abdominal malignancy, and neurologic dysfunction. Approximately 2% to 4.3% of all patients who have stoma creation surgery related to underlying IBD develop PPG. It is estimated that the yearly incidence rate of PPG in all abdominal stomas is quite low (approximately 0.6%).4

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum can occur at any age, but it tends to predominate in young to middle-aged adults, with a slight female predilection. The etiology and pathogenesis of PPG are largely unknown, though studies have shown that an abnormal immune response may be critical to its development. Risk factors for PPG are not well defined but potentially include autoimmune disorders, a high body mass index, and females or African Americans with IBD.4 Because PPG does not have characteristic histopathologic features, it is a diagnosis of exclusion that is based on the clinical examination and histologic findings that rule out other potential disorders.

There are 4 types of PPG based on the clinical and histopathologic characteristics: ulcerative, pustular, bullous, and vegetative. Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum tends to be either ulcerative or vegetative, with ulcerative being by far the predominant type. The onset of PPG is quite variable, occurring a few weeks to several years after stoma formation.5 Ulcer size can range from less than 3 cm to 30 cm.4 Lesions begin as deep painful nodules or as superficial hemorrhagic pustules, either idiopathic or following ostensibly minimal trauma. Subsequently, they become necrotic and form an ulceration. The ulcers can be single or multiple lesions, typically with erythematous raised borders and purulent discharge. The ulcers are extremely painful and rapidly progressive. After the ulcers heal, they often leave a characteristic weblike atrophic scar that can break down further following any form of irritation or trauma.5

A prompt diagnosis of PPG is important. A diagnosis of PPG should be considered when dealing with a noninfectious ulcer surrounding a stoma in patients with IBD or other autoimmune conditions.6 Because PPG is a rare skin disorder, it is likely to be missed and lead to unnecessary diagnostic workup and a delay in proper therapy. In our patient, a diagnosis of PPG was overlooked for other infectious and autoimmune causes. The diagnostic evaluation of a patient with PPG is based on 3 principles: (1) ruling out other causes of a peristomal ulcer, such as an abscess, contact dermatitis, or wound infection; (2) determining whether there is an underlying intestinal bowel disease in the stoma; and (3) identifying associated systemic disorders such as vasculitis, erythema nodosum, or similar processes.4 The differential diagnosis depends on the type and stage of PPG and can include malignancy, vasculitis, extraintestinal IBD, infectious disease, and insect bites. A review of the history of the ulcer is helpful in ruling out other diseases, and a colonoscopy or ileoscopy can identify if patients have an underlying active IBD. Swabs for smear and both bacterial and fungal cultures should be taken from the exudate and directly from the ulcer base. Biopsy of the ulcer also helps to exclude alternative diagnoses.6

The primary goals of treating PPG include to reduce pain and the risk for secondary infection, increase pouch adherence, and decrease purulent exudate.7 Although there is not one well-defined optimal therapeutic intervention, there are a variety of effective approaches that may be considered and used. In mild cases, management methods such as dressings, topical agents, or intralesional steroids may be capable of controlling the disease. Daily wound care is important. Moisture-retentive dressings can control pain, induce collagen formation, promote angiogenesis, and prevent contamination. Cleaning the wound with sterile saline and applying an anti-infective agent also may be effective. Application of ultrapotent topical steroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.3% can be used in patients without concomitant secondary infection. In patients who are in remission, human platelet-derived growth factor may be used. Intralesional injections of dilute triamcinolone acetonide or cyclosporine solution also can be helpful. Cyclosporin A was used as a systemic monotherapy to treat a 48-year-old man and 50-year-old woman with the idiopathic form of PPG. After 3 months of treatment, PPG had completely resolved and there were no major side effects.8 Other potential topical therapies that control inflammation and promote wound healing include benzoyl peroxide, chlormethine (topical alkylating agent and nitrogen mustard that has anti-inflammatory properties), nicotine, and 5-aminosalicylic acid. If an ulcer becomes infected, empiric antibiotic therapy should be given immediately and adjusted based on culture and sensitivity results.4

Systemic therapy should be considered in patients who do not respond to topical or local interventions, have a rapid and severe course, or have an active underlying bowel disease. Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) has proved to be one of the most successful drugs used to treat PPG. Treatment should be continued until complete lesion healing, and low-dose maintenance therapy should be administered in recurrent cases. Intravenous corticosteroid therapy—hydrocortisone 100 mg 4 times daily or pulse therapy with intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/d)—can be used for up to 5 days and may be effective. Oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily may be helpful as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids. When corticosteroids fail, oral cyclosporine 3 to 5 mg/kg/d often is prescribed. Studies have shown that patients demonstrate clinical improvement within 3 weeks of cyclosporine initiation, and it has been shown further to be more effective than either azathioprine or methotrexate.4,8

Infliximab, a chimeric antibody that binds both circulating and tissue-bound TNF-α, has been shown to effectively treat PPG. A clinical trial conducted by Brooklyn et al9 found that 46% of patients (6/13) treated with infliximab responded compared with only 6% in a placebo control group (1/17). Although infliximab may result in sepsis, the benefits far outweigh the risks, especially for patients with steroid-refractory PPG.4 Adalimumab is a human monoclonal IgG1 antibody to TNF-α that neutralizes its function by blocking the interaction between the molecule and its receptor. Many clinical studies have shown that adalimumab induces and maintains a clinical response in patients with active Crohn disease. The biologic proved to be effective in our patient, but it is associated with potential side effects that should be monitored including injection-site reactions, pruritus, leukopenia, urticaria, and rare instances of alopecia.10 Etanercept is another potentially effective biologic agent.7 Plasma exchange, immunoglobulin infusion, and interferon-alfa therapy also can be used in refractory PPG cases, though data on these treatments are very limited.4

Unlike routine pyoderma gangrenosum—for which surgical intervention is contraindicated—surgical intervention may be appropriate for the peristomal variant. Surgical treatment options include stoma revision and/or relocation; however, both of these procedures are accompanied by failure rates ranging from 40% to 100%.5 Removal of a diseased intestinal segment, especially one with active IBD, may result in healing of the skin lesion. In our patient, removal of the residual and diseased J-pouch was part of the management plan. However,it generally is recommended that any surgical intervention be accompanied by medical therapy including oral metronidazole 500 mg/d and concomitant administration of an immunosuppressant.1,3

Because PPG tends to recur, long-term maintenance therapy should always be considered. Pain reduction, anemia correction, proper nutrition, and management of associated and underlying diseases should be performed. Meticulous care of the stoma and prevention of leaks also should be emphasized. Overall, if PPG is detected and diagnosed early as well as treated appropriately and aggressively, the patient likely will have a good prognosis.4

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

- Sheldon DG, Sawchuk LL, Kozarek RA, et al. Twenty cases of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: diagnostic implications and management. Arch Surg. 2000;135:564-569.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP. Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546-1548.

- Afifi L, Sanchez IM, Wallace MM, et al. Diagnosis and management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1195-1204.

- Wu XR, Shen B. Diagnosis and management of parastomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2013;1:1-8.

- Javed A, Pal S, Ahuja V, et al. Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: two different approaches for the same clinical problem. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:153-156.

- Toh JW, Whiteley I. Devastating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges in diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:A19-A20.

- DeMartyn LE, Faller NA, Miller L. Treating peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum with topical crushed prednisone: a report of three cases. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2014;60:50-54.

- V’lckova-Laskoska MT, Laskoski DS, Caca-Biljanovska NG, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with cyclosporin A.Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:541-555.

- Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, at al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509.

- Alkhouri N, Hupertz V, Mahajan L. Adalimumab treatment for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:803-806.

Practice Points

- A pyoderma gangrenosum subtype occurs in close proximity to an abdominal stoma.

- Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum is a diagnosis of exclusion.

- Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum typically responds best to tumor necrosis factor α blockers and corticosteroid therapy (intralesional and systemic).

Topical gene therapy for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa shows promise

INDIANAPOLIS – An investigational compared with placebo, according to results from a small phase 3 study.

DEB is a serious, ultra-rare genetic blistering disease caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, encoding for type VII collagen and leading to skin fragility and wounds. No approved therapies are currently available. In the study, treatment was generally well tolerated.

“B-VEC is the first treatment that has not only been shown to be effective, but the first to directly target the defect through topical application,” the study’s principal investigator, Shireen V. Guide, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It delivers type VII collagen gene therapy to these patients, which allows healing in areas that they may have had open since birth. It’s been life-changing for them.”

B-VEC is a herpes simplex virus (HSV-1)-based topical, redosable gene therapy being developed by Krystal Biotech that is designed to restore functional COL7 protein by delivering the COL7A1 gene. For the phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study known GEM-3, Dr. Guide, who practices dermatology in Rancho Santa Margarita, Calif., and her colleagues, including Peter Marinkovich, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, and Mercedes Gonzalez, MD, from the University of Miami, enrolled 31 patients aged 6 months and older with genetically confirmed DEB. Each patient had one wound treated randomized 1:1 to treatment with B-VEC once a week or placebo for 6 months. The mean age of the 31 study participants was 17 years, 65% were male, 65% were White, and 19% were Asian.

The primary endpoint was complete wound healing (defined as 100% wound closure from exact wound area at baseline, specified as skin re-epithelialization without drainage) at 6 months. Additional endpoints included complete wound healing at 3 months and change in pain associated with wound dressing changes.

At 3 months, 70% of wounds treated with B-VEC met the endpoint of complete wound healing, compared with 20% of wounds treated with placebo (P < .005). At 6 months, 67% of wounds treated with B-VEC met the endpoint of complete wound healing compared with 22% of those treated with placebo (P < .005).

Of the total wounds that closed at 3 months, 67% of wounds treated with B-VEC were also closed at 6 months, compared with 33% of those treated with placebo (P = .02). In other findings, a trend toward decreased pain was observed in wounds treated with B-VEC vs. those treated with placebo.

B-VEC was well tolerated with no treatment-related serious adverse events or discontinuations. Three patients experienced a total of five serious adverse events during the study: anemia (two events), and cellulitis, diarrhea, and positive blood culture (one event each). None were considered related to the study drug.

Dr. Guide, who is on staff at Children’s Health of Orange County, Orange, Calif., characterized B-VEC as “very novel because it’s very practical.”

To date, all treatments for DEB “have been extremely labor intensive, including skin grafting and hospitalizations. It’s a topical application that can be done in the office and potentially applied at home in the future. It’s also durable. Not only are the [treated] areas closing, but they are staying closed.”

Kalyani S. Marathe, MD, MPH, director of the dermatology division at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who was asked to comment on the study, said that topical application of B-VEC “allows the side effect profile to be very favorable. The results are remarkable in the amount of wound healing and reduction in pain.”

The tolerability of this medication “is crucial,” she added. “EB patients have a lot of pain from their wounds and so any treatment needs to be as painless as possible for it to be usable. I’m very excited about the next phase of studies for this medication and hopeful that it heralds new treatments for our EB patients.”

In June 2022, the manufacturer announced that it had submitted a biologics license application to the Food and Drug Administration for approval of B-VEC for the treatment of DEB, and that it anticipates submitting an application for marketing authorization with the European Medical Agency (EMA) in the second half of 2022.

Dr. Guide disclosed that she has served as an investigator for Krystal Biotech, Innovaderm Research, Arcutis, Premier Research, Paidion, and Castle Biosciences. Dr. Marathe disclosed that she has served as an adviser for Verrica, and that Cincinnati Children’s Hospital is a site for the next phase studies for B-VEC.

*This story was updated on July 25.

INDIANAPOLIS – An investigational compared with placebo, according to results from a small phase 3 study.

DEB is a serious, ultra-rare genetic blistering disease caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, encoding for type VII collagen and leading to skin fragility and wounds. No approved therapies are currently available. In the study, treatment was generally well tolerated.

“B-VEC is the first treatment that has not only been shown to be effective, but the first to directly target the defect through topical application,” the study’s principal investigator, Shireen V. Guide, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It delivers type VII collagen gene therapy to these patients, which allows healing in areas that they may have had open since birth. It’s been life-changing for them.”

B-VEC is a herpes simplex virus (HSV-1)-based topical, redosable gene therapy being developed by Krystal Biotech that is designed to restore functional COL7 protein by delivering the COL7A1 gene. For the phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study known GEM-3, Dr. Guide, who practices dermatology in Rancho Santa Margarita, Calif., and her colleagues, including Peter Marinkovich, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, and Mercedes Gonzalez, MD, from the University of Miami, enrolled 31 patients aged 6 months and older with genetically confirmed DEB. Each patient had one wound treated randomized 1:1 to treatment with B-VEC once a week or placebo for 6 months. The mean age of the 31 study participants was 17 years, 65% were male, 65% were White, and 19% were Asian.

The primary endpoint was complete wound healing (defined as 100% wound closure from exact wound area at baseline, specified as skin re-epithelialization without drainage) at 6 months. Additional endpoints included complete wound healing at 3 months and change in pain associated with wound dressing changes.

At 3 months, 70% of wounds treated with B-VEC met the endpoint of complete wound healing, compared with 20% of wounds treated with placebo (P < .005). At 6 months, 67% of wounds treated with B-VEC met the endpoint of complete wound healing compared with 22% of those treated with placebo (P < .005).

Of the total wounds that closed at 3 months, 67% of wounds treated with B-VEC were also closed at 6 months, compared with 33% of those treated with placebo (P = .02). In other findings, a trend toward decreased pain was observed in wounds treated with B-VEC vs. those treated with placebo.

B-VEC was well tolerated with no treatment-related serious adverse events or discontinuations. Three patients experienced a total of five serious adverse events during the study: anemia (two events), and cellulitis, diarrhea, and positive blood culture (one event each). None were considered related to the study drug.

Dr. Guide, who is on staff at Children’s Health of Orange County, Orange, Calif., characterized B-VEC as “very novel because it’s very practical.”

To date, all treatments for DEB “have been extremely labor intensive, including skin grafting and hospitalizations. It’s a topical application that can be done in the office and potentially applied at home in the future. It’s also durable. Not only are the [treated] areas closing, but they are staying closed.”

Kalyani S. Marathe, MD, MPH, director of the dermatology division at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who was asked to comment on the study, said that topical application of B-VEC “allows the side effect profile to be very favorable. The results are remarkable in the amount of wound healing and reduction in pain.”

The tolerability of this medication “is crucial,” she added. “EB patients have a lot of pain from their wounds and so any treatment needs to be as painless as possible for it to be usable. I’m very excited about the next phase of studies for this medication and hopeful that it heralds new treatments for our EB patients.”

In June 2022, the manufacturer announced that it had submitted a biologics license application to the Food and Drug Administration for approval of B-VEC for the treatment of DEB, and that it anticipates submitting an application for marketing authorization with the European Medical Agency (EMA) in the second half of 2022.

Dr. Guide disclosed that she has served as an investigator for Krystal Biotech, Innovaderm Research, Arcutis, Premier Research, Paidion, and Castle Biosciences. Dr. Marathe disclosed that she has served as an adviser for Verrica, and that Cincinnati Children’s Hospital is a site for the next phase studies for B-VEC.

*This story was updated on July 25.

INDIANAPOLIS – An investigational compared with placebo, according to results from a small phase 3 study.

DEB is a serious, ultra-rare genetic blistering disease caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, encoding for type VII collagen and leading to skin fragility and wounds. No approved therapies are currently available. In the study, treatment was generally well tolerated.

“B-VEC is the first treatment that has not only been shown to be effective, but the first to directly target the defect through topical application,” the study’s principal investigator, Shireen V. Guide, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It delivers type VII collagen gene therapy to these patients, which allows healing in areas that they may have had open since birth. It’s been life-changing for them.”

B-VEC is a herpes simplex virus (HSV-1)-based topical, redosable gene therapy being developed by Krystal Biotech that is designed to restore functional COL7 protein by delivering the COL7A1 gene. For the phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study known GEM-3, Dr. Guide, who practices dermatology in Rancho Santa Margarita, Calif., and her colleagues, including Peter Marinkovich, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, and Mercedes Gonzalez, MD, from the University of Miami, enrolled 31 patients aged 6 months and older with genetically confirmed DEB. Each patient had one wound treated randomized 1:1 to treatment with B-VEC once a week or placebo for 6 months. The mean age of the 31 study participants was 17 years, 65% were male, 65% were White, and 19% were Asian.

The primary endpoint was complete wound healing (defined as 100% wound closure from exact wound area at baseline, specified as skin re-epithelialization without drainage) at 6 months. Additional endpoints included complete wound healing at 3 months and change in pain associated with wound dressing changes.

At 3 months, 70% of wounds treated with B-VEC met the endpoint of complete wound healing, compared with 20% of wounds treated with placebo (P < .005). At 6 months, 67% of wounds treated with B-VEC met the endpoint of complete wound healing compared with 22% of those treated with placebo (P < .005).

Of the total wounds that closed at 3 months, 67% of wounds treated with B-VEC were also closed at 6 months, compared with 33% of those treated with placebo (P = .02). In other findings, a trend toward decreased pain was observed in wounds treated with B-VEC vs. those treated with placebo.

B-VEC was well tolerated with no treatment-related serious adverse events or discontinuations. Three patients experienced a total of five serious adverse events during the study: anemia (two events), and cellulitis, diarrhea, and positive blood culture (one event each). None were considered related to the study drug.

Dr. Guide, who is on staff at Children’s Health of Orange County, Orange, Calif., characterized B-VEC as “very novel because it’s very practical.”

To date, all treatments for DEB “have been extremely labor intensive, including skin grafting and hospitalizations. It’s a topical application that can be done in the office and potentially applied at home in the future. It’s also durable. Not only are the [treated] areas closing, but they are staying closed.”

Kalyani S. Marathe, MD, MPH, director of the dermatology division at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, who was asked to comment on the study, said that topical application of B-VEC “allows the side effect profile to be very favorable. The results are remarkable in the amount of wound healing and reduction in pain.”

The tolerability of this medication “is crucial,” she added. “EB patients have a lot of pain from their wounds and so any treatment needs to be as painless as possible for it to be usable. I’m very excited about the next phase of studies for this medication and hopeful that it heralds new treatments for our EB patients.”

In June 2022, the manufacturer announced that it had submitted a biologics license application to the Food and Drug Administration for approval of B-VEC for the treatment of DEB, and that it anticipates submitting an application for marketing authorization with the European Medical Agency (EMA) in the second half of 2022.

Dr. Guide disclosed that she has served as an investigator for Krystal Biotech, Innovaderm Research, Arcutis, Premier Research, Paidion, and Castle Biosciences. Dr. Marathe disclosed that she has served as an adviser for Verrica, and that Cincinnati Children’s Hospital is a site for the next phase studies for B-VEC.

*This story was updated on July 25.

AT SPD 2022

Focal Palmoplantar Keratoderma and Gingival Keratosis Caused by a KRT16 Mutation

To the Editor:

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis (FPGK)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 148730) is a rare autosomal-dominant syndrome featuring focal, pressure-related, painful palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival hyperkeratosis presenting as leukokeratosis. Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis was first defined by Gorlin1 in 1976. Since then, only a few cases have been reported, but no causative mutations have been identified.2

Focal pressure-related palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) and oral hyperkeratosis also are seen in pachyonychia congenita (PC)(OMIM 167200, 615726, 615728, 167210), a rare autosomal-dominant disorder of keratinization characterized by PPK and nail dystrophy. Patients with PC often present with plantar pain; more variable features include oral leukokeratosis, follicular hyperkeratosis, pilosebaceous and epidermal inclusion cysts, hoarseness, hyperhidrosis, and natal teeth. Pachyonychia congenita is caused by mutation in keratin genes KRT6A, KRT6B, KRT16, or KRT17.

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis as well as PC are distinct from other forms of PPK with gingival involvement such as

Despite the common features of FPGK and PC, they are considered distinct disorders due to absence of nail changes in FPGK and no prior evidence of a common genetic cause. We present a patient with familial FPGK found by whole exome sequencing to be caused by a mutation in KRT16.

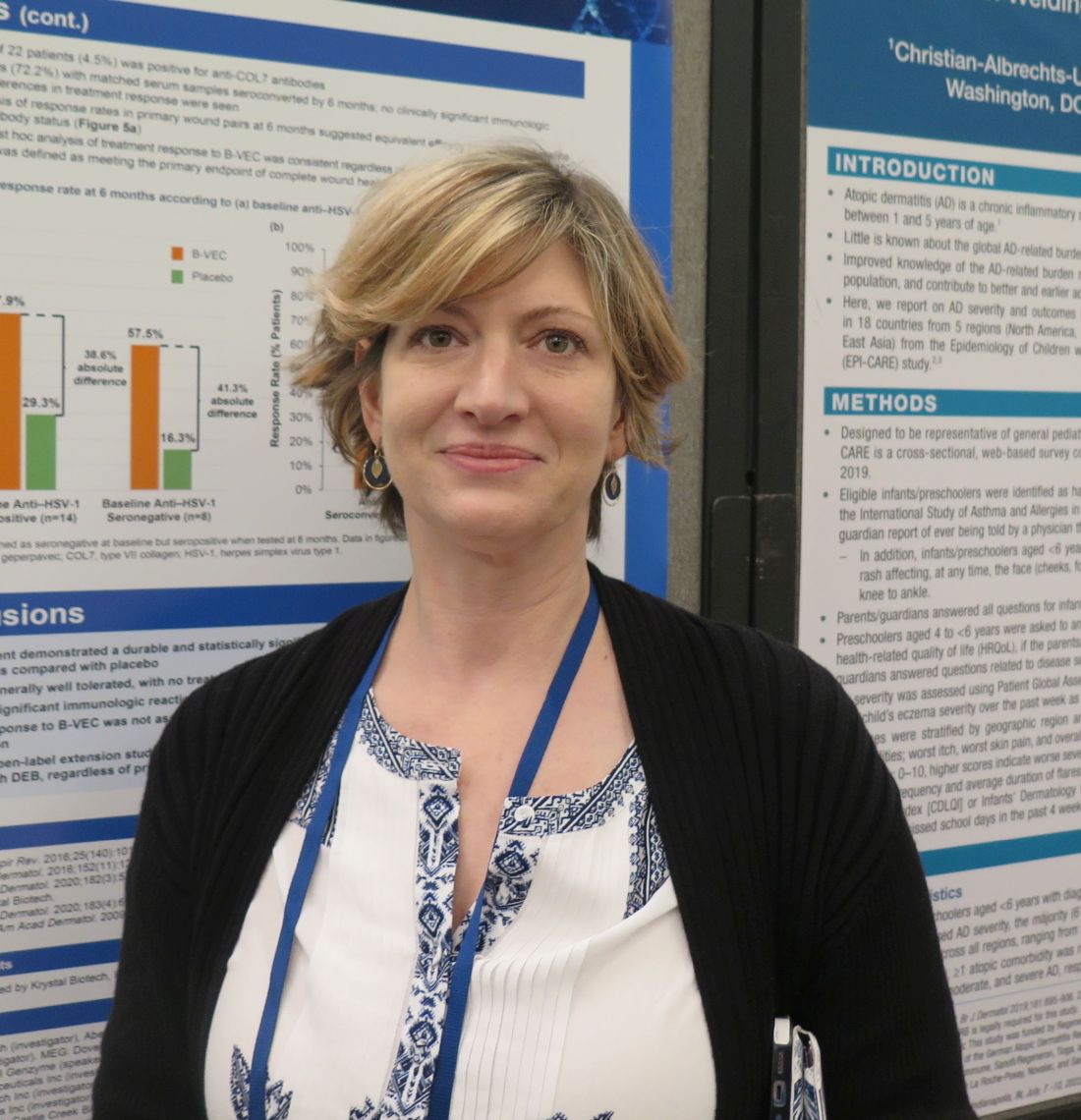

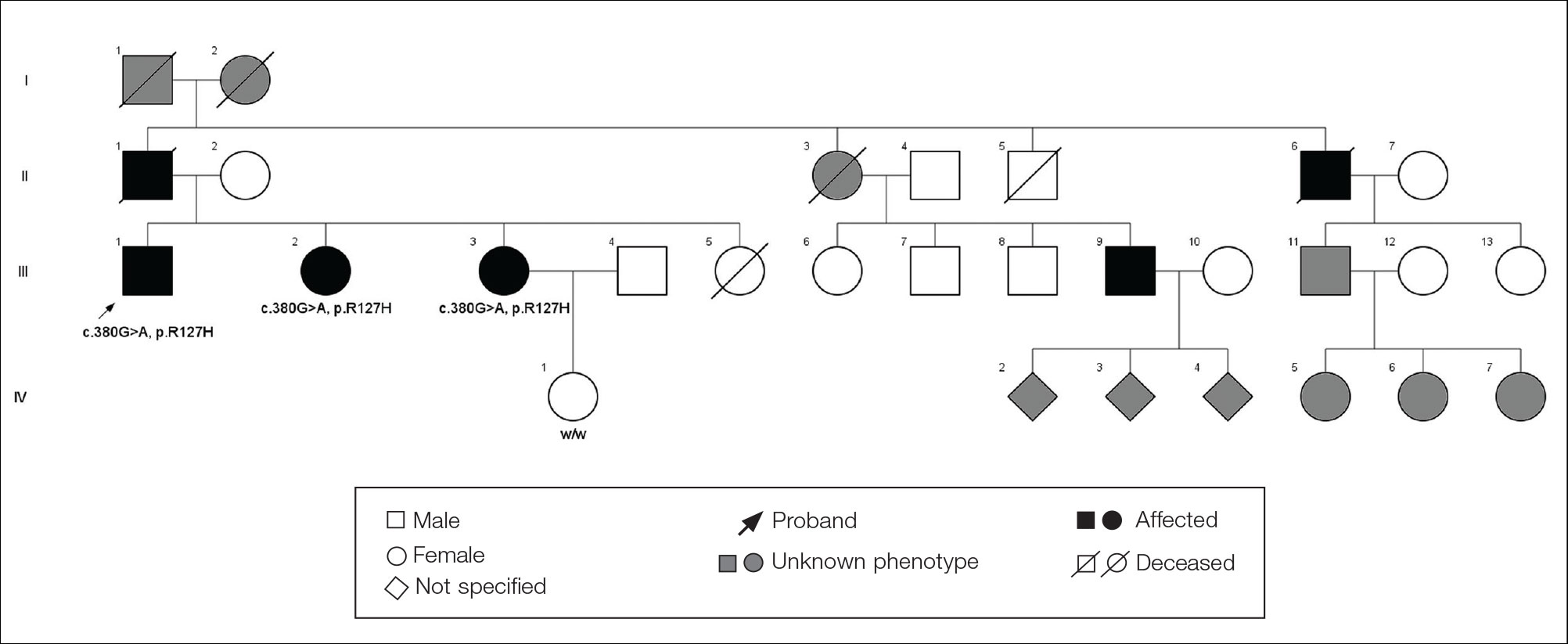

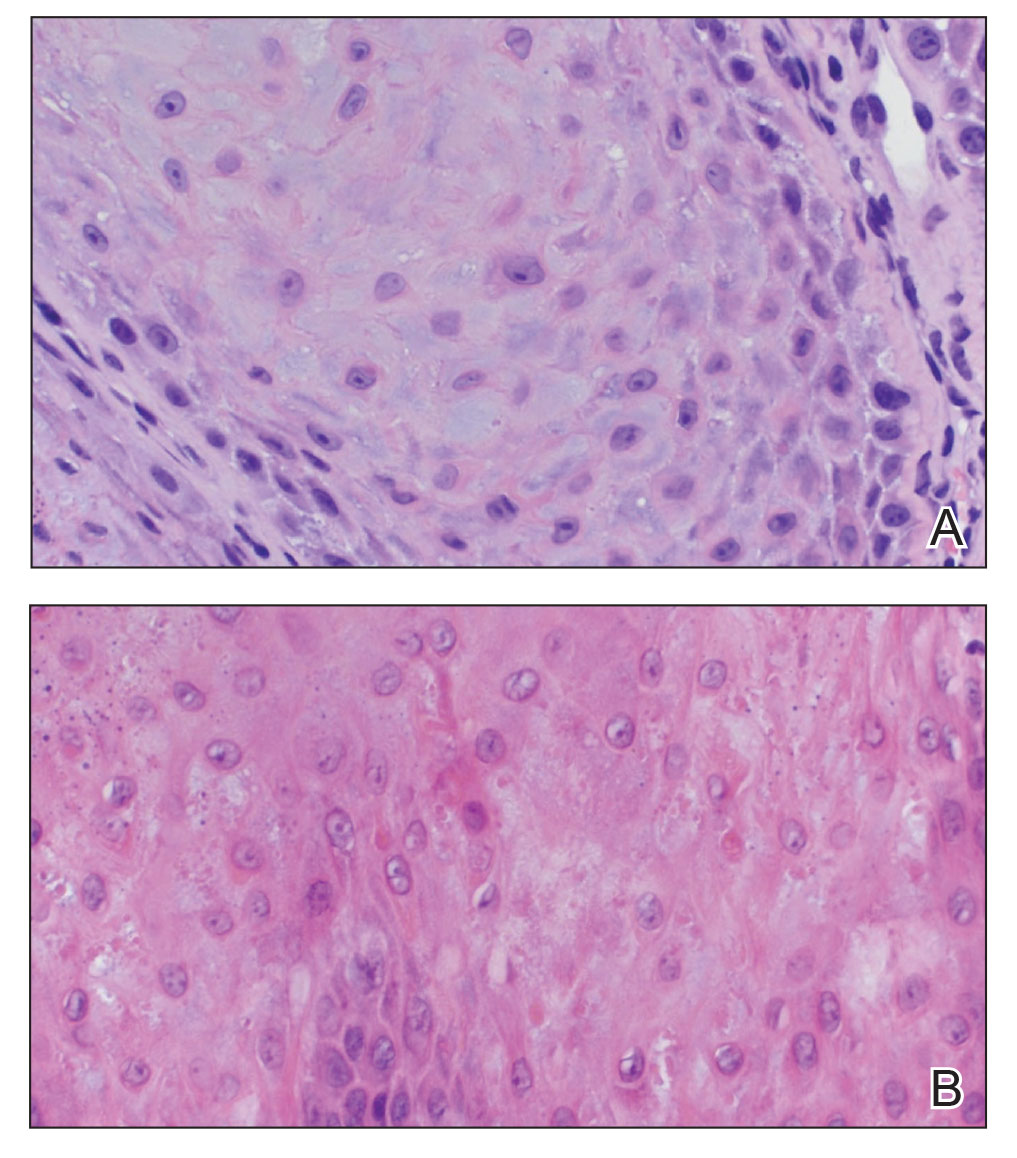

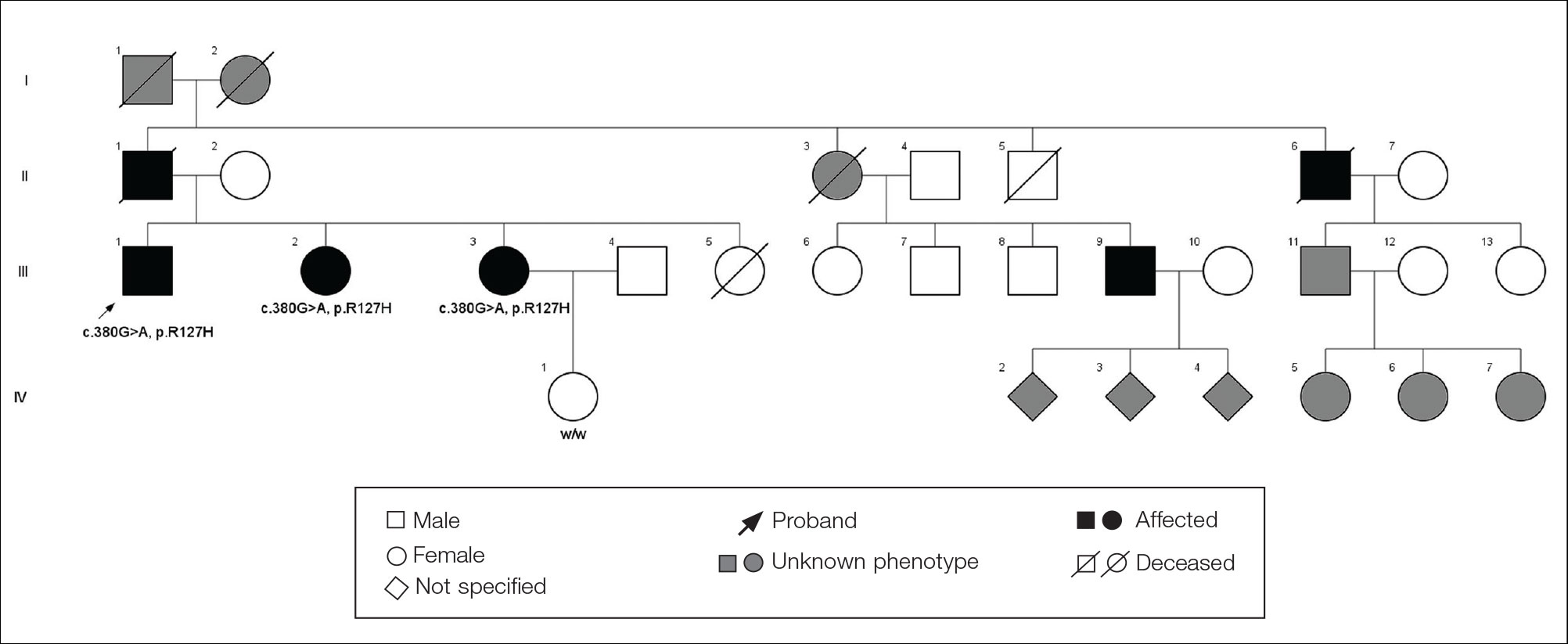

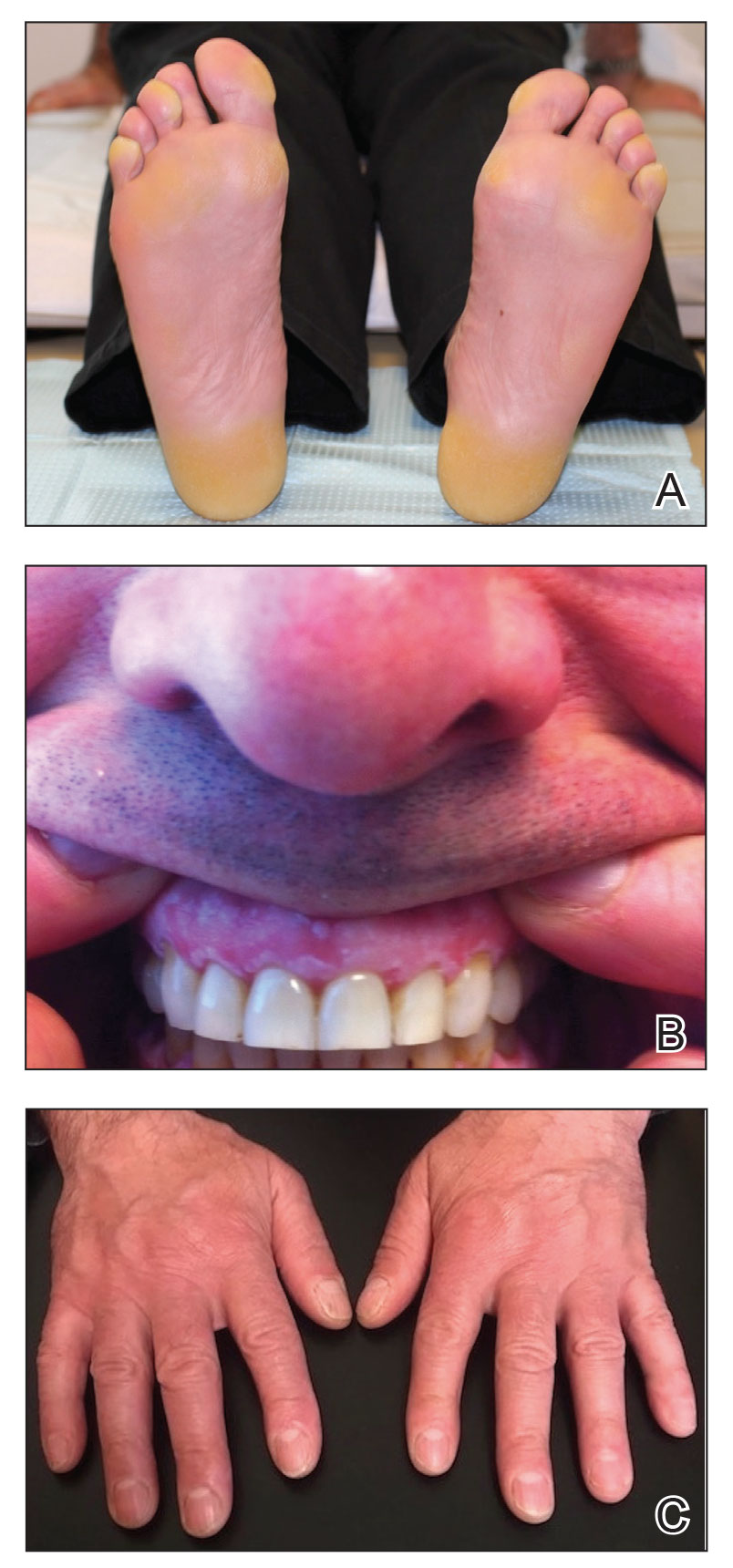

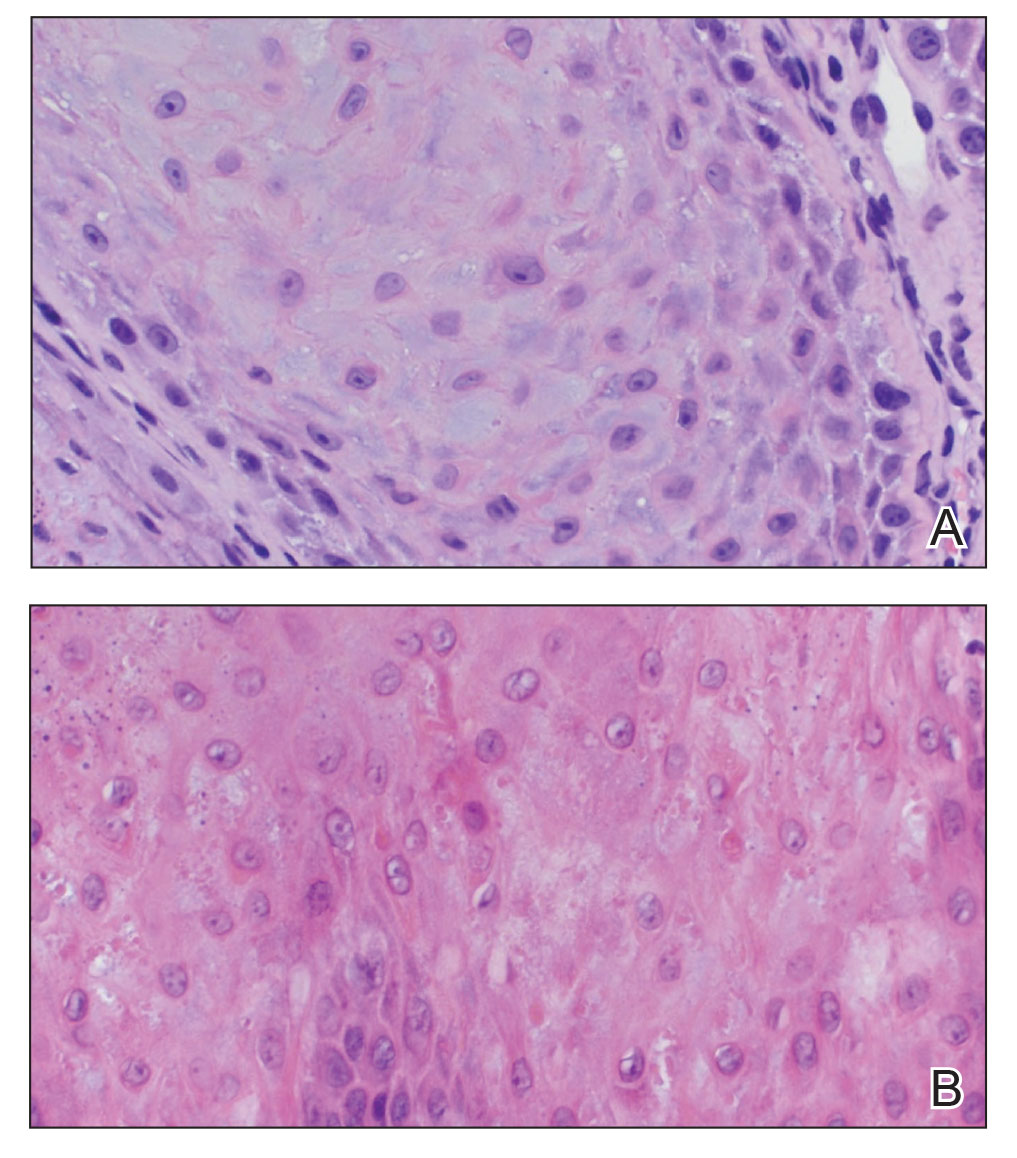

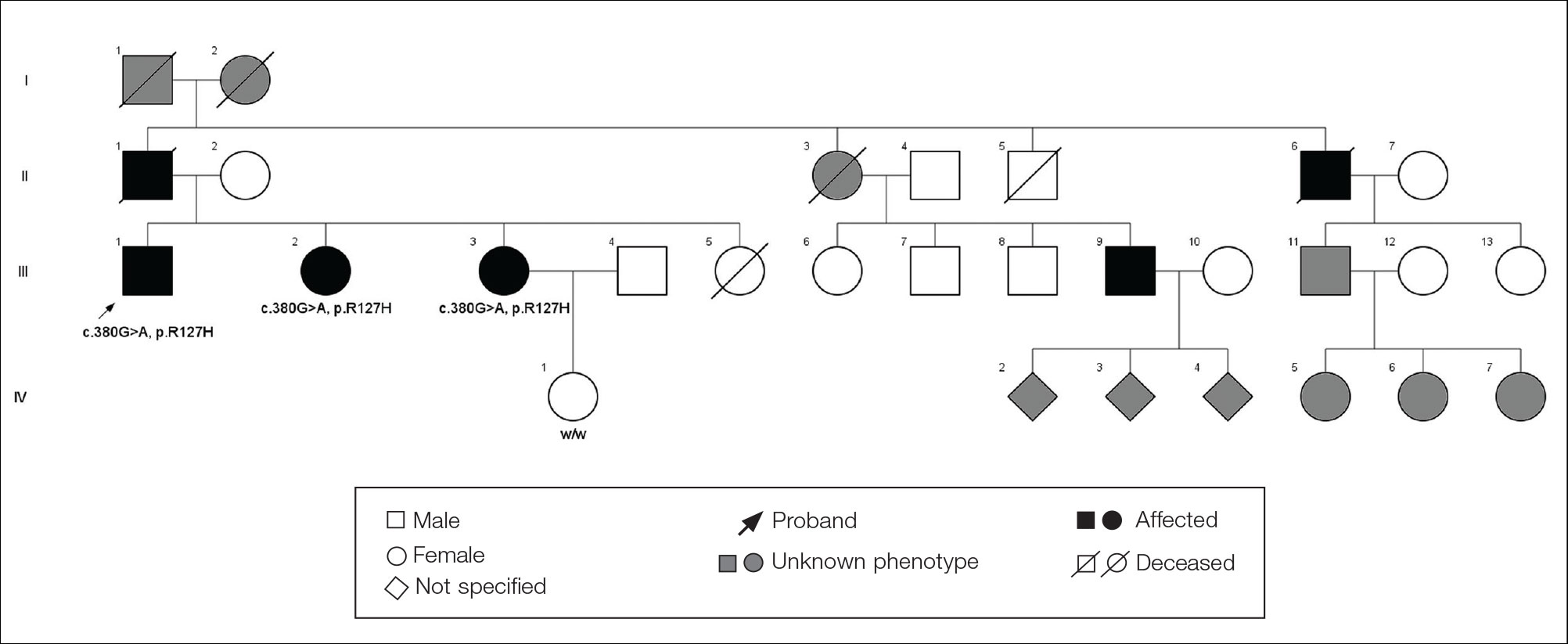

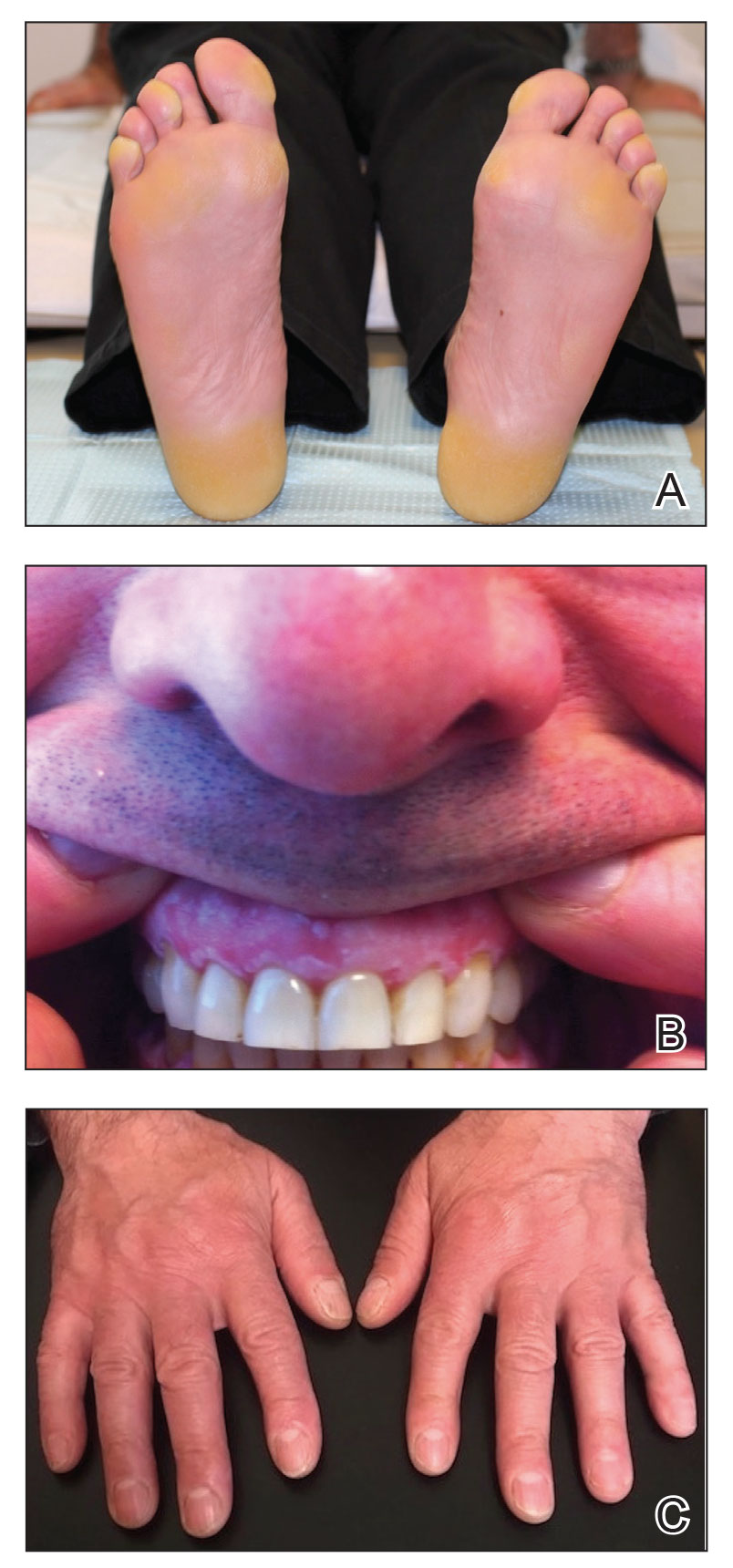

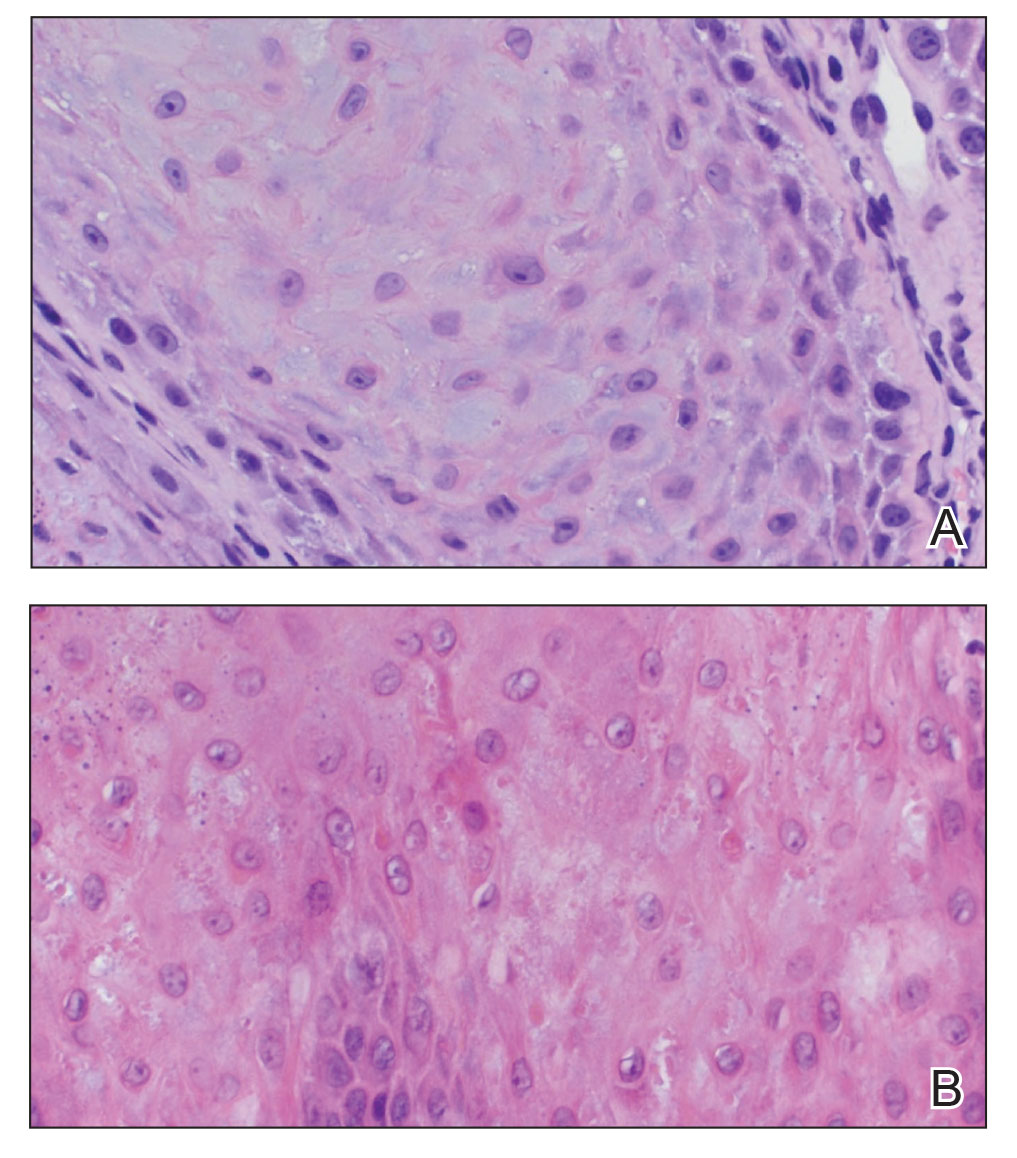

The proband was a 57-year-old man born to unrelated parents (Figure 1). He had no skin problems at birth, and his development was normal. He had painful focal keratoderma since childhood that were most prominent at pressure points on the soles and toes (Figure 2A), in addition to gingival hyperkeratosis and oral leukokeratosis (Figure 2B). He had no associated abnormalities of the skin, hair, or teeth and no nail findings (Figure 2C). He reported that his father and 2 of his 3 sisters were affected with similar symptoms. A punch biopsy of the right fifth toe was consistent with verrucous epidermal hyperplasia with perinuclear keratinization in the spinous layer (Figure 3A). A gingival biopsy showed perinuclear eosinophilic globules and basophilic stranding in the cytoplasm (Figure 3B). His older sister had more severe and painful focal keratoderma of the soles, punctate keratoderma of the palms, gingival hyperkeratosis, and leukokeratosis of the tongue.

Whole exome sequencing of the proband revealed a heterozygous missense mutation in KRT16 (c.380G>A, p.R127H, rs57424749). Sanger sequencing confirmed this mutation and showed that it was heterozygous in both of his affected sisters and absent in his unaffected niece (Figure 1). The patient was treated with topical and systemic retinoids, keratolytics, and mechanical removal to moderate effect, with noted improvement in the appearance and associated pain of the plantar keratoderma.

Phenotypic heterogeneity is common in PC, though PC due to KRT6A mutations demonstrates more severe nail disease with oral lesions, cysts, and follicular hyperkeratosis, while PC caused by KRT16 mutations generally presents with more extensive and painful PPK.4KRT16 mutations affecting p.R127 are frequent causes of PC, and genotype-phenotype correlations have been observed. Individuals with p.R127P mutations exhibit more severe disease with earlier age of onset, more extensive nail involvement and oral leukokeratosis, and greater impact on daily quality of life than in individuals with p.R127C mutations.5 Cases of PC with KRT16 p.R127S and p.R127G mutations also have been observed. The KRT16 c.380G>A, p.R127H mutation we documented has been reported in one kindred with PC who presented with PPK, oral leukokeratosis, toenail thickening, and pilosebaceous and follicular hyperkeratosis.6

Although patients with FPGK lack the thickening of fingernails and/or toenails considered a defining feature of PC, the disorders otherwise are phenotypically similar, suggesting the possibility of common pathogenesis. One linkage study of familial FPGK excluded genetic intervals containing type I and type II keratins but was limited to a single small kindred.2 This study and our data together suggest that, similar to PC, there are multiple genes in which mutations cause FPGK.

Murine Krt16 knockouts show distinct phenotypes depending on the mouse strain in which they are propagated, ranging from perinatal lethality to differences in the severity of oral and PPK lesions.7 These observations provide evidence that additional genetic variants contribute to Krt16 phenotypes in mice and suggest the same could be true for humans.

We propose that some cases of FPGK are due to mutations in KRT16 and thus share a genetic pathogenesis with PC, underscoring the utility of whole exome sequencing in providing genetic diagnoses for disorders that are genetically and clinically heterogeneous. Further biologic investigation of phenotypes caused by KRT16 mutation may reveal respective contributions of additional genetic variation and environmental effects to the variable clinical presentations.

- Gorlin RJ. Focal palmoplantar and marginal gingival hyperkeratosis—a syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1976;12:239-242.

- Kolde G, Hennies HC, Bethke G, et al. Focal palmoplantar and gingival keratosis: a distinct palmoplantar ectodermal dysplasia with epidermolytic alterations but lack of mutations in known keratins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3 pt 1):403-409.

- Duchatelet S, Hovnanian A. Olmsted syndrome: clinical, molecular and therapeutic aspects. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:33.

- Spaunhurst KM, Hogendorf AM, Smith FJ, et al. Pachyonychia congenita patients with mutations in KRT6A have more extensive disease compared with patients who have mutations in KRT16. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:875-878.

- Fu T, Leachman SA, Wilson NJ, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations among pachyonychia congenita patients with K16 mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1025-1028.

- Wilson NJ, O’Toole EA, Milstone LM, et al. The molecular genetic analysis of the expanding pachyonychia congenita case collection. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:343-355.

- Zieman A, Coulombe PA. The keratin 16 null phenotype is modestly impacted by genetic strain background in mice. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:672-674.

To the Editor:

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis (FPGK)(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 148730) is a rare autosomal-dominant syndrome featuring focal, pressure-related, painful palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival hyperkeratosis presenting as leukokeratosis. Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis was first defined by Gorlin1 in 1976. Since then, only a few cases have been reported, but no causative mutations have been identified.2

Focal pressure-related palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK) and oral hyperkeratosis also are seen in pachyonychia congenita (PC)(OMIM 167200, 615726, 615728, 167210), a rare autosomal-dominant disorder of keratinization characterized by PPK and nail dystrophy. Patients with PC often present with plantar pain; more variable features include oral leukokeratosis, follicular hyperkeratosis, pilosebaceous and epidermal inclusion cysts, hoarseness, hyperhidrosis, and natal teeth. Pachyonychia congenita is caused by mutation in keratin genes KRT6A, KRT6B, KRT16, or KRT17.

Focal palmoplantar keratoderma and gingival keratosis as well as PC are distinct from other forms of PPK with gingival involvement such as