User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Untreatable, drug-resistant fungus found in Texas and Washington, D.C.

The CDC has reported two clusters of Candida auris infections resistant to all antifungal medications in long-term care facilities in 2021. Because these panresistant infections occurred without any exposure to antifungal drugs, the cases are even more worrisome. These clusters are the first time such nosocomial transmission has been detected.

In the District of Columbia, three panresistant isolates were discovered through screening for skin colonization with resistant organisms at a long-term acute care facility (LTAC) that cares for patients who are seriously ill, often on mechanical ventilation.

In Texas, the resistant organisms were found both by screening and in specimens from ill patients at an LTAC and a short-term acute care hospital that share patients. Two were panresistant, and five others were resistant to fluconazole and echinocandins.

These clusters occurred simultaneously and independently of each other; there were no links between the two institutions.

Colonization of skin with C. auris can lead to invasive infections in 5%-10% of affected patients. Routine skin surveillance cultures are not commonly done for Candida, although perirectal cultures for vancomycin-resistant enterococci and nasal swabs for MRSA have been done for years. Some areas, like Los Angeles, have recommended screening for C. auris in high-risk patients – defined as those who were on a ventilator or had a tracheostomy admitted from an LTAC or skilled nursing facility in Los Angeles County, New York, New Jersey, or Illinois.

In the past, about 85% of C. auris isolates in the United States have been resistant to azoles (for example, fluconazole), 33% to amphotericin B, and 1% to echinocandins. Because of generally strong susceptibility, an echinocandin such as micafungin or caspofungin has been the drug of choice for an invasive Candida infection.

C. auris is particularly difficult to deal with for several reasons. First, it can continue to live in the environment, on both dry or moist surfaces, for up to 2 weeks. Outbreaks have occurred both from hand (person-to-person) transmission or via inanimate surfaces that have become contaminated. Equally troublesome is that people become colonized with the yeast indefinitely.

Meghan Lyman, MD, of the fungal diseases branch of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said in an interview that facilities might be slow in recognizing the problem and in identifying the organism. “We encounter problems in noninvasive specimens, especially urine,” Dr. Lyman added.

“Sometimes ... they consider Candida [to represent] colonization so they will often not speciate it.” She emphasized the need for facilities that care for ventilated patients to consider screening. “Higher priority ... are places in areas where there’s a lot of C. auris transmission or in nearby areas that are likely to get introductions.” Even those that do speciate may have difficulty identifying C. auris.

Further, Dr. Lyman stressed “the importance of antifungal susceptibility testing and testing for resistance. Because that’s also something that’s not widely available at all hospitals and clinical labs ... you can send it to the [CDC’s] antimicrobial resistance lab network” for testing.

COVID-19 has brought particular challenges. Rodney E. Rohde, PhD, MS, professor and chair, clinical lab science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, said in an interview that he is worried about all the steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics patients receive.

They’re “being given medical interventions, whether it’s ventilators or [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or IVs or central lines or catheters for UTIs and you’re creating highways, right for something that may be right there,” said Dr. Rohde, who was not involved in the CDC study. “It’s a perfect storm, not just for C. auris, but I worry about bacterial resistance agents, too, like MRSA and so forth, having kind of a spike in those types of infections with COVID. So, it’s kind of a doubly dangerous time, I think.”

Multiresistant bacteria are a major health problem, causing illnesses in 2.8 million people annually in the United States, and causing about 35,000 deaths.

Dr. Rohde raised another, rarely mentioned concern. “We’re in crisis mode. People are leaving our field more than they ever had before. The medical laboratory is being decimated because people have burned out after these past 14 months. And so I worry just about competent medical laboratory professionals that are on board to deal with these types of other crises that are popping up within hospitals and long-term care facilities. It kind of keeps me awake.”

Dr. Rohde and Dr. Lyman shared their concern that COVID caused a decrease in screening for other infections and drug-resistant organisms. Bare-bones staffing and shortages of personal protective equipment have likely fueled the spread of these infections as well.

In an outbreak of C. auris in a Florida hospital’s COVID unit in 2020, 35 of 67 patients became colonized, and 6 became ill. The epidemiologists investigating thought that contaminated gowns or gloves, computers, and other equipment were likely sources of transmission.

Low pay, especially in nursing homes, is another problem Dr. Rohde mentioned. It’s an additional problem in both acute and long-term care that “some of the lowest-paid people are the environmental services people, and so the turnover is crazy.” Yet, we rely on them to keep everyone safe. He added that, in addition to pay, he “tries to give them the appreciation and the recognition that they really deserve.”

There are a few specific measures that can be taken to protect patients. Dr. Lyman concluded. “The best way is identifying cases and really ensuring good infection control to prevent the spread.” It’s back to basics – limiting broad-spectrum antibiotics and invasive medical devices, and especially good handwashing and thorough cleaning.

Dr. Lyman and Dr. Rohde have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The CDC has reported two clusters of Candida auris infections resistant to all antifungal medications in long-term care facilities in 2021. Because these panresistant infections occurred without any exposure to antifungal drugs, the cases are even more worrisome. These clusters are the first time such nosocomial transmission has been detected.

In the District of Columbia, three panresistant isolates were discovered through screening for skin colonization with resistant organisms at a long-term acute care facility (LTAC) that cares for patients who are seriously ill, often on mechanical ventilation.

In Texas, the resistant organisms were found both by screening and in specimens from ill patients at an LTAC and a short-term acute care hospital that share patients. Two were panresistant, and five others were resistant to fluconazole and echinocandins.

These clusters occurred simultaneously and independently of each other; there were no links between the two institutions.

Colonization of skin with C. auris can lead to invasive infections in 5%-10% of affected patients. Routine skin surveillance cultures are not commonly done for Candida, although perirectal cultures for vancomycin-resistant enterococci and nasal swabs for MRSA have been done for years. Some areas, like Los Angeles, have recommended screening for C. auris in high-risk patients – defined as those who were on a ventilator or had a tracheostomy admitted from an LTAC or skilled nursing facility in Los Angeles County, New York, New Jersey, or Illinois.

In the past, about 85% of C. auris isolates in the United States have been resistant to azoles (for example, fluconazole), 33% to amphotericin B, and 1% to echinocandins. Because of generally strong susceptibility, an echinocandin such as micafungin or caspofungin has been the drug of choice for an invasive Candida infection.

C. auris is particularly difficult to deal with for several reasons. First, it can continue to live in the environment, on both dry or moist surfaces, for up to 2 weeks. Outbreaks have occurred both from hand (person-to-person) transmission or via inanimate surfaces that have become contaminated. Equally troublesome is that people become colonized with the yeast indefinitely.

Meghan Lyman, MD, of the fungal diseases branch of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said in an interview that facilities might be slow in recognizing the problem and in identifying the organism. “We encounter problems in noninvasive specimens, especially urine,” Dr. Lyman added.

“Sometimes ... they consider Candida [to represent] colonization so they will often not speciate it.” She emphasized the need for facilities that care for ventilated patients to consider screening. “Higher priority ... are places in areas where there’s a lot of C. auris transmission or in nearby areas that are likely to get introductions.” Even those that do speciate may have difficulty identifying C. auris.

Further, Dr. Lyman stressed “the importance of antifungal susceptibility testing and testing for resistance. Because that’s also something that’s not widely available at all hospitals and clinical labs ... you can send it to the [CDC’s] antimicrobial resistance lab network” for testing.

COVID-19 has brought particular challenges. Rodney E. Rohde, PhD, MS, professor and chair, clinical lab science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, said in an interview that he is worried about all the steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics patients receive.

They’re “being given medical interventions, whether it’s ventilators or [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or IVs or central lines or catheters for UTIs and you’re creating highways, right for something that may be right there,” said Dr. Rohde, who was not involved in the CDC study. “It’s a perfect storm, not just for C. auris, but I worry about bacterial resistance agents, too, like MRSA and so forth, having kind of a spike in those types of infections with COVID. So, it’s kind of a doubly dangerous time, I think.”

Multiresistant bacteria are a major health problem, causing illnesses in 2.8 million people annually in the United States, and causing about 35,000 deaths.

Dr. Rohde raised another, rarely mentioned concern. “We’re in crisis mode. People are leaving our field more than they ever had before. The medical laboratory is being decimated because people have burned out after these past 14 months. And so I worry just about competent medical laboratory professionals that are on board to deal with these types of other crises that are popping up within hospitals and long-term care facilities. It kind of keeps me awake.”

Dr. Rohde and Dr. Lyman shared their concern that COVID caused a decrease in screening for other infections and drug-resistant organisms. Bare-bones staffing and shortages of personal protective equipment have likely fueled the spread of these infections as well.

In an outbreak of C. auris in a Florida hospital’s COVID unit in 2020, 35 of 67 patients became colonized, and 6 became ill. The epidemiologists investigating thought that contaminated gowns or gloves, computers, and other equipment were likely sources of transmission.

Low pay, especially in nursing homes, is another problem Dr. Rohde mentioned. It’s an additional problem in both acute and long-term care that “some of the lowest-paid people are the environmental services people, and so the turnover is crazy.” Yet, we rely on them to keep everyone safe. He added that, in addition to pay, he “tries to give them the appreciation and the recognition that they really deserve.”

There are a few specific measures that can be taken to protect patients. Dr. Lyman concluded. “The best way is identifying cases and really ensuring good infection control to prevent the spread.” It’s back to basics – limiting broad-spectrum antibiotics and invasive medical devices, and especially good handwashing and thorough cleaning.

Dr. Lyman and Dr. Rohde have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The CDC has reported two clusters of Candida auris infections resistant to all antifungal medications in long-term care facilities in 2021. Because these panresistant infections occurred without any exposure to antifungal drugs, the cases are even more worrisome. These clusters are the first time such nosocomial transmission has been detected.

In the District of Columbia, three panresistant isolates were discovered through screening for skin colonization with resistant organisms at a long-term acute care facility (LTAC) that cares for patients who are seriously ill, often on mechanical ventilation.

In Texas, the resistant organisms were found both by screening and in specimens from ill patients at an LTAC and a short-term acute care hospital that share patients. Two were panresistant, and five others were resistant to fluconazole and echinocandins.

These clusters occurred simultaneously and independently of each other; there were no links between the two institutions.

Colonization of skin with C. auris can lead to invasive infections in 5%-10% of affected patients. Routine skin surveillance cultures are not commonly done for Candida, although perirectal cultures for vancomycin-resistant enterococci and nasal swabs for MRSA have been done for years. Some areas, like Los Angeles, have recommended screening for C. auris in high-risk patients – defined as those who were on a ventilator or had a tracheostomy admitted from an LTAC or skilled nursing facility in Los Angeles County, New York, New Jersey, or Illinois.

In the past, about 85% of C. auris isolates in the United States have been resistant to azoles (for example, fluconazole), 33% to amphotericin B, and 1% to echinocandins. Because of generally strong susceptibility, an echinocandin such as micafungin or caspofungin has been the drug of choice for an invasive Candida infection.

C. auris is particularly difficult to deal with for several reasons. First, it can continue to live in the environment, on both dry or moist surfaces, for up to 2 weeks. Outbreaks have occurred both from hand (person-to-person) transmission or via inanimate surfaces that have become contaminated. Equally troublesome is that people become colonized with the yeast indefinitely.

Meghan Lyman, MD, of the fungal diseases branch of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, said in an interview that facilities might be slow in recognizing the problem and in identifying the organism. “We encounter problems in noninvasive specimens, especially urine,” Dr. Lyman added.

“Sometimes ... they consider Candida [to represent] colonization so they will often not speciate it.” She emphasized the need for facilities that care for ventilated patients to consider screening. “Higher priority ... are places in areas where there’s a lot of C. auris transmission or in nearby areas that are likely to get introductions.” Even those that do speciate may have difficulty identifying C. auris.

Further, Dr. Lyman stressed “the importance of antifungal susceptibility testing and testing for resistance. Because that’s also something that’s not widely available at all hospitals and clinical labs ... you can send it to the [CDC’s] antimicrobial resistance lab network” for testing.

COVID-19 has brought particular challenges. Rodney E. Rohde, PhD, MS, professor and chair, clinical lab science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, said in an interview that he is worried about all the steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics patients receive.

They’re “being given medical interventions, whether it’s ventilators or [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] or IVs or central lines or catheters for UTIs and you’re creating highways, right for something that may be right there,” said Dr. Rohde, who was not involved in the CDC study. “It’s a perfect storm, not just for C. auris, but I worry about bacterial resistance agents, too, like MRSA and so forth, having kind of a spike in those types of infections with COVID. So, it’s kind of a doubly dangerous time, I think.”

Multiresistant bacteria are a major health problem, causing illnesses in 2.8 million people annually in the United States, and causing about 35,000 deaths.

Dr. Rohde raised another, rarely mentioned concern. “We’re in crisis mode. People are leaving our field more than they ever had before. The medical laboratory is being decimated because people have burned out after these past 14 months. And so I worry just about competent medical laboratory professionals that are on board to deal with these types of other crises that are popping up within hospitals and long-term care facilities. It kind of keeps me awake.”

Dr. Rohde and Dr. Lyman shared their concern that COVID caused a decrease in screening for other infections and drug-resistant organisms. Bare-bones staffing and shortages of personal protective equipment have likely fueled the spread of these infections as well.

In an outbreak of C. auris in a Florida hospital’s COVID unit in 2020, 35 of 67 patients became colonized, and 6 became ill. The epidemiologists investigating thought that contaminated gowns or gloves, computers, and other equipment were likely sources of transmission.

Low pay, especially in nursing homes, is another problem Dr. Rohde mentioned. It’s an additional problem in both acute and long-term care that “some of the lowest-paid people are the environmental services people, and so the turnover is crazy.” Yet, we rely on them to keep everyone safe. He added that, in addition to pay, he “tries to give them the appreciation and the recognition that they really deserve.”

There are a few specific measures that can be taken to protect patients. Dr. Lyman concluded. “The best way is identifying cases and really ensuring good infection control to prevent the spread.” It’s back to basics – limiting broad-spectrum antibiotics and invasive medical devices, and especially good handwashing and thorough cleaning.

Dr. Lyman and Dr. Rohde have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Persistent Panniculitis in Dermatomyositis

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman with a history of dermatomyositis (DM) presented to dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple subcutaneous nodules. Two years prior to the current presentation, the patient was diagnosed by her primary care physician with DM based on clinical presentation. She initially developed body aches, muscle pain, and weakness of the upper extremities, specifically around the shoulders, and later the lower extremities, specifically around the thighs. The initial physical examination revealed pain with movement, tenderness to palpation, and proximal extremity weakness. The patient also noted a 50-lb weight loss. Over the next year, she noted dysphagia and developed multiple subcutaneous nodules on the right arm, chest, and left axilla. Subsequently, she developed a violaceous, hyperpigmented, periorbital rash and erythema of the anterior chest. She did not experience hair loss, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, or joint pain.

Laboratory testing in the months following the initial presentation revealed a creatine phosphokinase level of 436 U/L (reference range, 20–200 U/L), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h (reference range, <31 mm/h), and an aldolase level of 10.4 U/L (reference range, 1.0–8.0 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. Antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith antibodies, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti–Jo-1 antibodies, and anti–smooth muscle antibodies all were negative. Total blood complement levels were elevated, but complement C3 and C4 were within normal limits. Imaging demonstrated normal chest radiographs, and a modified barium swallow confirmed swallowing dysfunction. A right quadricep muscle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of DM. A malignancy work-up including mammography, colonoscopy, and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative aside from nodular opacities in the chest. She was treated with prednisone (60 mg, 0.9 mg/kg) daily and methotrexate (15–20 mg) weekly for several months. While the treatment attenuated the rash and improved weakness, the nodules persisted, prompting a referral to dermatology.

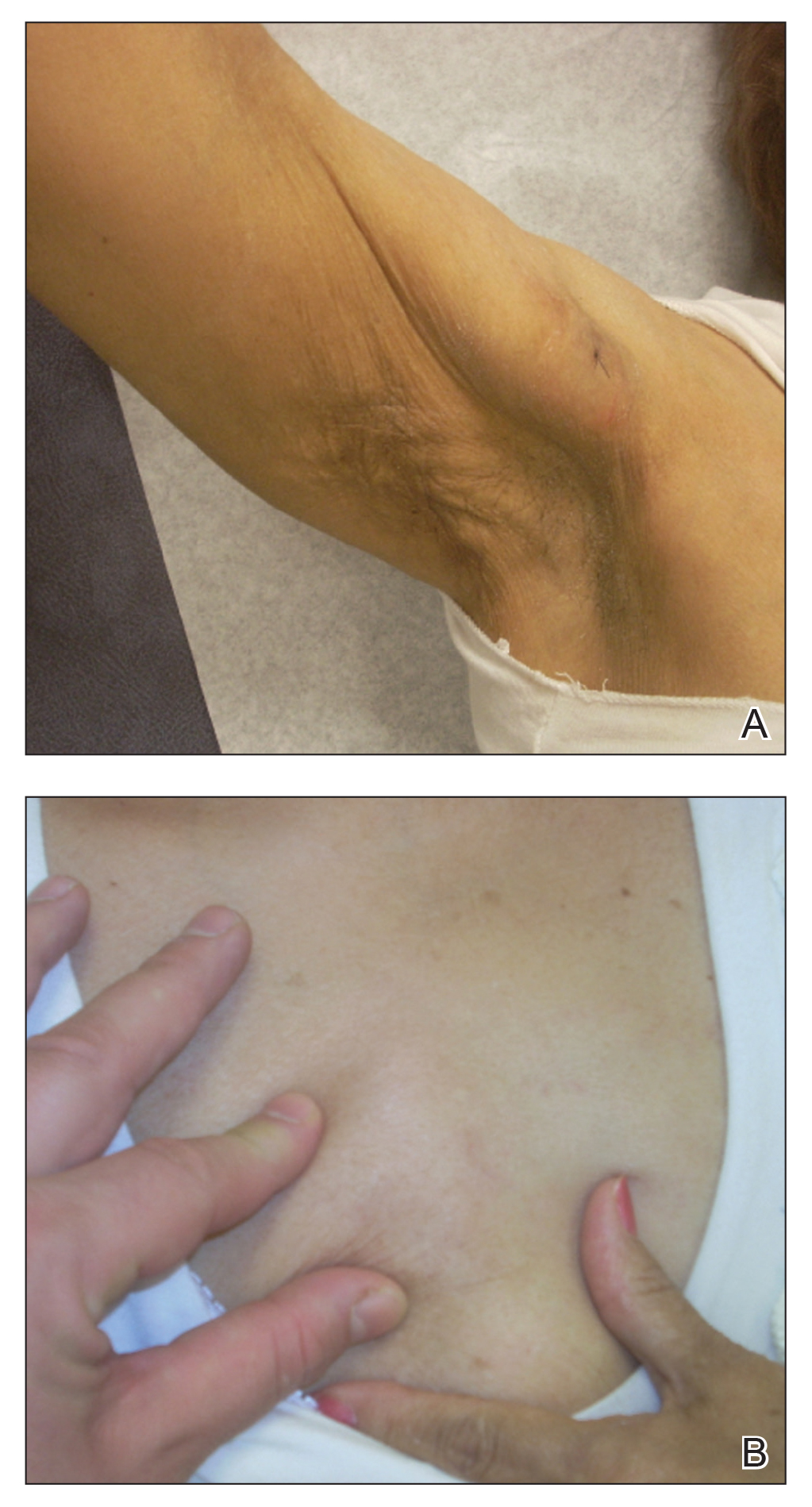

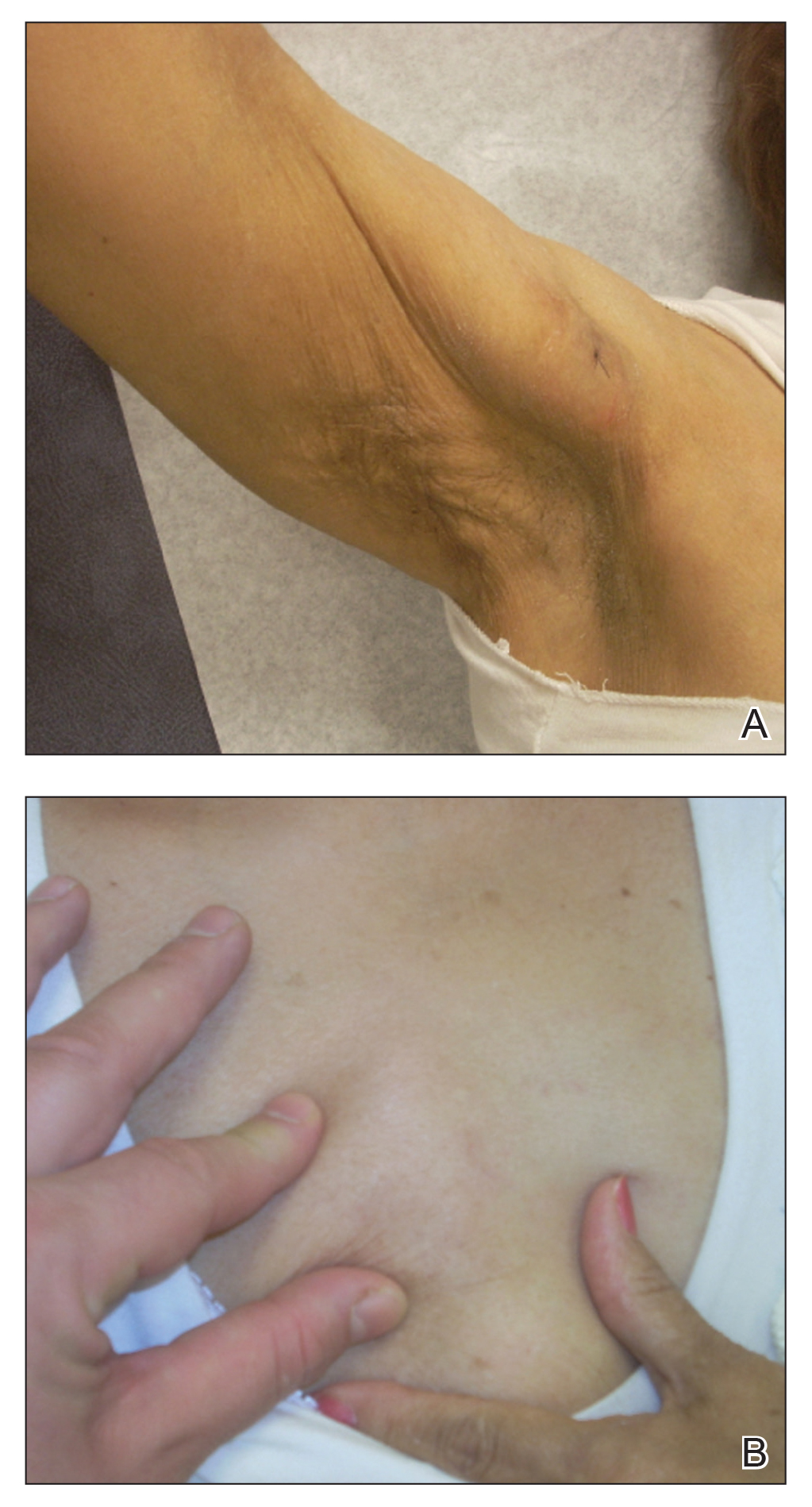

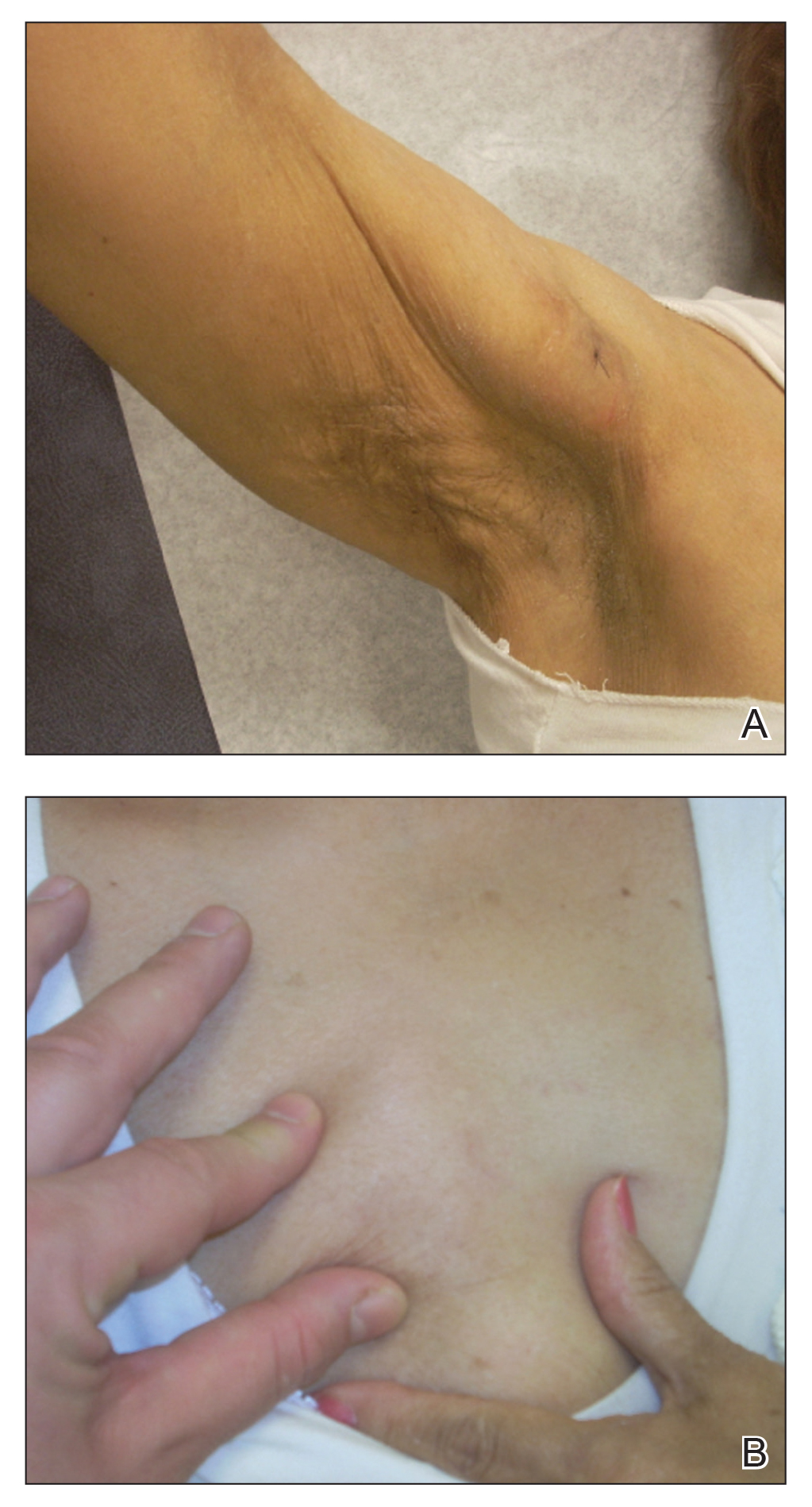

Physical examination at the dermatology clinic demonstrated the persistent subcutaneous nodules were indurated and bilaterally located on the arms, axillae, chest, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs with no pain or erythema (Figure). Laboratory tests demonstrated a normal creatine phosphokinase level, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (70 mm/h), and elevated aldolase level (9.3 U/L). Complement levels were elevated, though complement C3 and C4 remained within normal limits. Histopathology of nodules from the medial right upper arm and left thigh showed lobular panniculitis with fat necrosis, calcification, and interface changes. The patient was treated for several months with daily mycophenolate mofetil (1 g increased to 3 g) and daily hydroxychloroquine (200 mg) without any effect on the nodules.

The histologic features of panniculitis in lupus and DM are similar and include multifocal hyalinization of the subcuticular fat and diffuse lobular infiltrates of mature lymphocytes without nuclear atypia.1 Though clinical panniculitis is a rare finding in DM, histologic panniculitis is a relatively common finding.2 Despite the similar histopathology of lupus and DM, the presence of typical DM clinical and laboratory features in our patient (body aches, muscle pain, proximal weakness, cutaneous manifestations, elevated creatine phosphokinase, normal complement C3 and C4) made a diagnosis of DM more likely.

Clinical panniculitis is a rare subcutaneous manifestation of DM with around 50 cases reported in the literature (Table). A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms dermatomyositis and panniculitis through July 2019. Additionally, a full-text review and search of references within these articles was used to identify all cases of patients presenting with panniculitis in the setting of DM. Exclusion criteria were cases in which another etiology was considered likely (infectious panniculitis and lupus panniculitis) as well as those without an English translation. We identified 43 cases; the average age of the patients was 39.6 years, and 36 (83.7%) of the cases were women. Patients typically presented with persistent, indurated, painful, erythematous, nodular lesions localized to the arms, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs.

While panniculitis has been reported preceding and concurrent with a diagnosis of DM, a number of cases described presentation as late as 5 years following onset of classic DM symptoms.12,13,31 In some cases (3/43 [7.0%]), panniculitis was the only cutaneous manifestation of DM.15,33,36 However, it occurred more commonly with other characteristic skin findings, such as heliotrope rash or Gottron sign.Some investigators have recommended that panniculitis be included as a diagnostic feature of DM and that DM be considered in the differential diagnosis in isolated cases of panniculitis.25,33

Though it seems panniculitis in DM may correlate with a better prognosis, we identified underlying malignancies in 3 cases. Malignancies associated with panniculitis in DM included ovarian adenocarcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and parotid carcinoma, indicating that appropriate cancer screening still is critical in the diagnostic workup.2,11,22

A majority of the reported panniculitis cases in DM have responded to treatment with prednisone; however, treatment with prednisone has been more recalcitrant in other cases. Reports of successful additional therapies include methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin, mepacrine, or a combination of these entities.19,22 In most cases, improvement of the panniculitis and other DM symptoms occurred simultaneously.25 It is noteworthy that the muscular symptoms often resolved more rapidly than cutaneous manifestations.33 Few reported cases (6 including the current case) found a persistent panniculitis despite improvement and remission of the myositis.3,5,10,11,30

Our patient was treated with both prednisone and methotrexate for several months, leading to remission of muscular symptoms (along with return to baseline of creatine phosphokinase), yet the panniculitis did not improve. The subcutaneous nodules also did not respond to treatment with mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine.

Recent immunohistochemical studies have suggested that panniculitic lesions show better outcomes with immunosuppressive therapy when compared with other DM-related skin lesions.40 However, this was not the case for our patient, who after months of immunosuppressive therapy showed complete resolution of the periorbital and chest rashes with persistence of multiple indurated subcutaneous nodules.

Our case adds to a number of reports of DM presenting with panniculitis. Our patient fit the classic demographic of previously reported cases, as she was an adult woman without evidence of underlying malignancy; however, our case remains an example of the therapeutic challenge that exists when encountering a persistent, treatment-resistant panniculitis despite resolution of all other features of DM.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Girouard SD, Velez NF, Penson RT, et al. Panniculitis associated with dermatomyositis and recurrent ovarian cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:740-744.

- van Dongen HM, van Vugt RM, Stoof TJ. Extensive persistent panniculitis in the context of dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26:E187-E188.

- Choi YJ, Yoo WH. Panniculitis, a rare presentation of onset and exacerbation of juvenile dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33:367-371.

- Azevedo PO, Castellen NR, Salai AF, et al. Panniculitis associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:119-121.

- Agulló A, Hinds B, Larrea M, et al. Livedo racemosa, reticulated ulcerations, panniculitis and violaceous plaques in a 46-year-old woman. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:47-49.

- Hattori Y, Matsuyama K, Takahashi T, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis presenting with cellulitis-like erythema on the mandible as an initial symptom. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018;10:110-114.

- Hasegawa A, Shimomura Y, Kibune N, et al. Panniculitis as the initial manifestation of dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibody. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:551-553.

- Salman A, Kasapcopur O, Ergun T, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis: report of a case and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2016;43:951-953.

- Carroll M, Mellick N, Wagner G. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a case report. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:224‐226.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kulthanan K, Manapajon A. Calcific panniculitis and nasopharyngeal cancer-associated adult-onset dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Springerplus. 2015;4:201.

- Otero Rivas MM, Vicente Villa A, González Lara L, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:574-575.

- Yanaba K, Tanito K, Hamaguchi Y, et al. Anti‐transcription intermediary factor‐1γ/α/β antibody‐positive dermatomyositis associated with multiple panniculitis lesions. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;20:1831-1834.

- Pau-Charles I, Moreno PJ, Ortiz-Ibanez K, et al. Anti-MDA5 positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis presenting with severe cardiomyopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1097-1102.

- Lamb R, Digby S, Stewart W, et al. Cutaneous ulceration: more than skin deep? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:443-445.

- Arias M, Hernández MI, Cunha LG, et al. Panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:146-148.

- Hemmi S, Kushida R, Nishimura H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of panniculitis in dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:151-153.

- Geddes MR, Sinnreich M, Chalk C. Minocycline-induced dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:547-549.

- Abdul‐Wahab A, Holden CA, Harland C, et al Calcific panniculitis in adult‐onset dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E854-E856.

- Carneiro S, Alvim G, Resende P, et al. Dermatomyositis with panniculitis. Skinmed. 2007;6:46-47.

- Carrera E, Lobrinus JA, Spertini O, et al. Dermatomyositis, lobarpanniculitis and inflammatory myopathy with abundant macrophages. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:468-471.

- Lin JH, Chu CY, Lin RY. Panniculitis in adult onset dermatomyositis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Sinica. 2006;24:194-200.

- Chen GY, Liu MF, Lee JY, et al. Combination of massive mucinosis, dermatomyositis, pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcer, bullae and fatal intestinal vasculopathy in a young female. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:396-400.

- Nakamori A, Yamaguchi Y, Kurimoto I, et al. Vesiculobullous dermatomyositis with panniculitis without muscle disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1136-1139.

- Solans R, Cortés J, Selva A, et al. Panniculitis: a cutaneous manifestation of dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:S148-S150.

- Chao YY, Yang LJ. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:141-144.

- Lee MW, Lim YS, Choi JH, et al. Panniculitis showing membranocystic changes in the dermatomyositis. J Dermatol. 1999;26:608‐610.

- Ghali FE, Reed AM, Groben PA, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:270-272.

- Molnar K, Kemeny L, Korom I, et al. Panniculitis in dermatomyositis: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:161‐163.

- Ishikawa O, Tamura A, Ryuzaki K, et al. Membranocystic changes in the panniculitis of dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:773-776.

- Sabroe RA, Wallington TB, Kennedy CT. Dermatomyositis treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins and associated with panniculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:164-167.

- Neidenbach PJ, Sahn EE, Helton J. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:305-307.

- Fusade T, Belanyi P, Joly P, et al. Subcutaneous changes in dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:451-453.

- Winkelmann WJ, Billick RC, Srolovitz H. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:127-128.

- Commens C, O’Neill P, Walker G. Dermatomyositis associated with multifocal lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:966-969.

- Raimer SS, Solomon AR, Daniels JC. Polymyositis presenting with panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2 pt 2):366‐369.

- Feldman D, Hochberg MC, Zizic TM, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis in adult polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:85-89.

- Kimura S, Fukuyama Y. Tubular cytoplasmic inclusions in a case of childhood dermatomyositis with migratory subcutaneous nodules. Eur J Pediatr. 1977;125:275-283.

- Weber FP, Gray AMH. Chronic relapsing polydermatomyositis with predominant involvement of the subcutaneous fat. Br J Dermatol. 1924;36:544-560.

- Santos‐Briz A, Calle A, Linos K, et al. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 18 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1352-1359.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman with a history of dermatomyositis (DM) presented to dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple subcutaneous nodules. Two years prior to the current presentation, the patient was diagnosed by her primary care physician with DM based on clinical presentation. She initially developed body aches, muscle pain, and weakness of the upper extremities, specifically around the shoulders, and later the lower extremities, specifically around the thighs. The initial physical examination revealed pain with movement, tenderness to palpation, and proximal extremity weakness. The patient also noted a 50-lb weight loss. Over the next year, she noted dysphagia and developed multiple subcutaneous nodules on the right arm, chest, and left axilla. Subsequently, she developed a violaceous, hyperpigmented, periorbital rash and erythema of the anterior chest. She did not experience hair loss, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, or joint pain.

Laboratory testing in the months following the initial presentation revealed a creatine phosphokinase level of 436 U/L (reference range, 20–200 U/L), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h (reference range, <31 mm/h), and an aldolase level of 10.4 U/L (reference range, 1.0–8.0 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. Antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith antibodies, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti–Jo-1 antibodies, and anti–smooth muscle antibodies all were negative. Total blood complement levels were elevated, but complement C3 and C4 were within normal limits. Imaging demonstrated normal chest radiographs, and a modified barium swallow confirmed swallowing dysfunction. A right quadricep muscle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of DM. A malignancy work-up including mammography, colonoscopy, and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative aside from nodular opacities in the chest. She was treated with prednisone (60 mg, 0.9 mg/kg) daily and methotrexate (15–20 mg) weekly for several months. While the treatment attenuated the rash and improved weakness, the nodules persisted, prompting a referral to dermatology.

Physical examination at the dermatology clinic demonstrated the persistent subcutaneous nodules were indurated and bilaterally located on the arms, axillae, chest, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs with no pain or erythema (Figure). Laboratory tests demonstrated a normal creatine phosphokinase level, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (70 mm/h), and elevated aldolase level (9.3 U/L). Complement levels were elevated, though complement C3 and C4 remained within normal limits. Histopathology of nodules from the medial right upper arm and left thigh showed lobular panniculitis with fat necrosis, calcification, and interface changes. The patient was treated for several months with daily mycophenolate mofetil (1 g increased to 3 g) and daily hydroxychloroquine (200 mg) without any effect on the nodules.

The histologic features of panniculitis in lupus and DM are similar and include multifocal hyalinization of the subcuticular fat and diffuse lobular infiltrates of mature lymphocytes without nuclear atypia.1 Though clinical panniculitis is a rare finding in DM, histologic panniculitis is a relatively common finding.2 Despite the similar histopathology of lupus and DM, the presence of typical DM clinical and laboratory features in our patient (body aches, muscle pain, proximal weakness, cutaneous manifestations, elevated creatine phosphokinase, normal complement C3 and C4) made a diagnosis of DM more likely.

Clinical panniculitis is a rare subcutaneous manifestation of DM with around 50 cases reported in the literature (Table). A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms dermatomyositis and panniculitis through July 2019. Additionally, a full-text review and search of references within these articles was used to identify all cases of patients presenting with panniculitis in the setting of DM. Exclusion criteria were cases in which another etiology was considered likely (infectious panniculitis and lupus panniculitis) as well as those without an English translation. We identified 43 cases; the average age of the patients was 39.6 years, and 36 (83.7%) of the cases were women. Patients typically presented with persistent, indurated, painful, erythematous, nodular lesions localized to the arms, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs.

While panniculitis has been reported preceding and concurrent with a diagnosis of DM, a number of cases described presentation as late as 5 years following onset of classic DM symptoms.12,13,31 In some cases (3/43 [7.0%]), panniculitis was the only cutaneous manifestation of DM.15,33,36 However, it occurred more commonly with other characteristic skin findings, such as heliotrope rash or Gottron sign.Some investigators have recommended that panniculitis be included as a diagnostic feature of DM and that DM be considered in the differential diagnosis in isolated cases of panniculitis.25,33

Though it seems panniculitis in DM may correlate with a better prognosis, we identified underlying malignancies in 3 cases. Malignancies associated with panniculitis in DM included ovarian adenocarcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and parotid carcinoma, indicating that appropriate cancer screening still is critical in the diagnostic workup.2,11,22

A majority of the reported panniculitis cases in DM have responded to treatment with prednisone; however, treatment with prednisone has been more recalcitrant in other cases. Reports of successful additional therapies include methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin, mepacrine, or a combination of these entities.19,22 In most cases, improvement of the panniculitis and other DM symptoms occurred simultaneously.25 It is noteworthy that the muscular symptoms often resolved more rapidly than cutaneous manifestations.33 Few reported cases (6 including the current case) found a persistent panniculitis despite improvement and remission of the myositis.3,5,10,11,30

Our patient was treated with both prednisone and methotrexate for several months, leading to remission of muscular symptoms (along with return to baseline of creatine phosphokinase), yet the panniculitis did not improve. The subcutaneous nodules also did not respond to treatment with mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine.

Recent immunohistochemical studies have suggested that panniculitic lesions show better outcomes with immunosuppressive therapy when compared with other DM-related skin lesions.40 However, this was not the case for our patient, who after months of immunosuppressive therapy showed complete resolution of the periorbital and chest rashes with persistence of multiple indurated subcutaneous nodules.

Our case adds to a number of reports of DM presenting with panniculitis. Our patient fit the classic demographic of previously reported cases, as she was an adult woman without evidence of underlying malignancy; however, our case remains an example of the therapeutic challenge that exists when encountering a persistent, treatment-resistant panniculitis despite resolution of all other features of DM.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman with a history of dermatomyositis (DM) presented to dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple subcutaneous nodules. Two years prior to the current presentation, the patient was diagnosed by her primary care physician with DM based on clinical presentation. She initially developed body aches, muscle pain, and weakness of the upper extremities, specifically around the shoulders, and later the lower extremities, specifically around the thighs. The initial physical examination revealed pain with movement, tenderness to palpation, and proximal extremity weakness. The patient also noted a 50-lb weight loss. Over the next year, she noted dysphagia and developed multiple subcutaneous nodules on the right arm, chest, and left axilla. Subsequently, she developed a violaceous, hyperpigmented, periorbital rash and erythema of the anterior chest. She did not experience hair loss, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, or joint pain.

Laboratory testing in the months following the initial presentation revealed a creatine phosphokinase level of 436 U/L (reference range, 20–200 U/L), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h (reference range, <31 mm/h), and an aldolase level of 10.4 U/L (reference range, 1.0–8.0 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. Antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith antibodies, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti–Jo-1 antibodies, and anti–smooth muscle antibodies all were negative. Total blood complement levels were elevated, but complement C3 and C4 were within normal limits. Imaging demonstrated normal chest radiographs, and a modified barium swallow confirmed swallowing dysfunction. A right quadricep muscle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of DM. A malignancy work-up including mammography, colonoscopy, and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative aside from nodular opacities in the chest. She was treated with prednisone (60 mg, 0.9 mg/kg) daily and methotrexate (15–20 mg) weekly for several months. While the treatment attenuated the rash and improved weakness, the nodules persisted, prompting a referral to dermatology.

Physical examination at the dermatology clinic demonstrated the persistent subcutaneous nodules were indurated and bilaterally located on the arms, axillae, chest, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs with no pain or erythema (Figure). Laboratory tests demonstrated a normal creatine phosphokinase level, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (70 mm/h), and elevated aldolase level (9.3 U/L). Complement levels were elevated, though complement C3 and C4 remained within normal limits. Histopathology of nodules from the medial right upper arm and left thigh showed lobular panniculitis with fat necrosis, calcification, and interface changes. The patient was treated for several months with daily mycophenolate mofetil (1 g increased to 3 g) and daily hydroxychloroquine (200 mg) without any effect on the nodules.

The histologic features of panniculitis in lupus and DM are similar and include multifocal hyalinization of the subcuticular fat and diffuse lobular infiltrates of mature lymphocytes without nuclear atypia.1 Though clinical panniculitis is a rare finding in DM, histologic panniculitis is a relatively common finding.2 Despite the similar histopathology of lupus and DM, the presence of typical DM clinical and laboratory features in our patient (body aches, muscle pain, proximal weakness, cutaneous manifestations, elevated creatine phosphokinase, normal complement C3 and C4) made a diagnosis of DM more likely.

Clinical panniculitis is a rare subcutaneous manifestation of DM with around 50 cases reported in the literature (Table). A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms dermatomyositis and panniculitis through July 2019. Additionally, a full-text review and search of references within these articles was used to identify all cases of patients presenting with panniculitis in the setting of DM. Exclusion criteria were cases in which another etiology was considered likely (infectious panniculitis and lupus panniculitis) as well as those without an English translation. We identified 43 cases; the average age of the patients was 39.6 years, and 36 (83.7%) of the cases were women. Patients typically presented with persistent, indurated, painful, erythematous, nodular lesions localized to the arms, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs.

While panniculitis has been reported preceding and concurrent with a diagnosis of DM, a number of cases described presentation as late as 5 years following onset of classic DM symptoms.12,13,31 In some cases (3/43 [7.0%]), panniculitis was the only cutaneous manifestation of DM.15,33,36 However, it occurred more commonly with other characteristic skin findings, such as heliotrope rash or Gottron sign.Some investigators have recommended that panniculitis be included as a diagnostic feature of DM and that DM be considered in the differential diagnosis in isolated cases of panniculitis.25,33

Though it seems panniculitis in DM may correlate with a better prognosis, we identified underlying malignancies in 3 cases. Malignancies associated with panniculitis in DM included ovarian adenocarcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and parotid carcinoma, indicating that appropriate cancer screening still is critical in the diagnostic workup.2,11,22

A majority of the reported panniculitis cases in DM have responded to treatment with prednisone; however, treatment with prednisone has been more recalcitrant in other cases. Reports of successful additional therapies include methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin, mepacrine, or a combination of these entities.19,22 In most cases, improvement of the panniculitis and other DM symptoms occurred simultaneously.25 It is noteworthy that the muscular symptoms often resolved more rapidly than cutaneous manifestations.33 Few reported cases (6 including the current case) found a persistent panniculitis despite improvement and remission of the myositis.3,5,10,11,30

Our patient was treated with both prednisone and methotrexate for several months, leading to remission of muscular symptoms (along with return to baseline of creatine phosphokinase), yet the panniculitis did not improve. The subcutaneous nodules also did not respond to treatment with mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine.

Recent immunohistochemical studies have suggested that panniculitic lesions show better outcomes with immunosuppressive therapy when compared with other DM-related skin lesions.40 However, this was not the case for our patient, who after months of immunosuppressive therapy showed complete resolution of the periorbital and chest rashes with persistence of multiple indurated subcutaneous nodules.

Our case adds to a number of reports of DM presenting with panniculitis. Our patient fit the classic demographic of previously reported cases, as she was an adult woman without evidence of underlying malignancy; however, our case remains an example of the therapeutic challenge that exists when encountering a persistent, treatment-resistant panniculitis despite resolution of all other features of DM.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Girouard SD, Velez NF, Penson RT, et al. Panniculitis associated with dermatomyositis and recurrent ovarian cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:740-744.

- van Dongen HM, van Vugt RM, Stoof TJ. Extensive persistent panniculitis in the context of dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26:E187-E188.

- Choi YJ, Yoo WH. Panniculitis, a rare presentation of onset and exacerbation of juvenile dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33:367-371.

- Azevedo PO, Castellen NR, Salai AF, et al. Panniculitis associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:119-121.

- Agulló A, Hinds B, Larrea M, et al. Livedo racemosa, reticulated ulcerations, panniculitis and violaceous plaques in a 46-year-old woman. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:47-49.

- Hattori Y, Matsuyama K, Takahashi T, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis presenting with cellulitis-like erythema on the mandible as an initial symptom. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018;10:110-114.

- Hasegawa A, Shimomura Y, Kibune N, et al. Panniculitis as the initial manifestation of dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibody. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:551-553.

- Salman A, Kasapcopur O, Ergun T, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis: report of a case and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2016;43:951-953.

- Carroll M, Mellick N, Wagner G. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a case report. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:224‐226.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kulthanan K, Manapajon A. Calcific panniculitis and nasopharyngeal cancer-associated adult-onset dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Springerplus. 2015;4:201.

- Otero Rivas MM, Vicente Villa A, González Lara L, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:574-575.

- Yanaba K, Tanito K, Hamaguchi Y, et al. Anti‐transcription intermediary factor‐1γ/α/β antibody‐positive dermatomyositis associated with multiple panniculitis lesions. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;20:1831-1834.

- Pau-Charles I, Moreno PJ, Ortiz-Ibanez K, et al. Anti-MDA5 positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis presenting with severe cardiomyopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1097-1102.

- Lamb R, Digby S, Stewart W, et al. Cutaneous ulceration: more than skin deep? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:443-445.

- Arias M, Hernández MI, Cunha LG, et al. Panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:146-148.

- Hemmi S, Kushida R, Nishimura H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of panniculitis in dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:151-153.

- Geddes MR, Sinnreich M, Chalk C. Minocycline-induced dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:547-549.

- Abdul‐Wahab A, Holden CA, Harland C, et al Calcific panniculitis in adult‐onset dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E854-E856.

- Carneiro S, Alvim G, Resende P, et al. Dermatomyositis with panniculitis. Skinmed. 2007;6:46-47.

- Carrera E, Lobrinus JA, Spertini O, et al. Dermatomyositis, lobarpanniculitis and inflammatory myopathy with abundant macrophages. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:468-471.

- Lin JH, Chu CY, Lin RY. Panniculitis in adult onset dermatomyositis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Sinica. 2006;24:194-200.

- Chen GY, Liu MF, Lee JY, et al. Combination of massive mucinosis, dermatomyositis, pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcer, bullae and fatal intestinal vasculopathy in a young female. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:396-400.

- Nakamori A, Yamaguchi Y, Kurimoto I, et al. Vesiculobullous dermatomyositis with panniculitis without muscle disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1136-1139.

- Solans R, Cortés J, Selva A, et al. Panniculitis: a cutaneous manifestation of dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:S148-S150.

- Chao YY, Yang LJ. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:141-144.

- Lee MW, Lim YS, Choi JH, et al. Panniculitis showing membranocystic changes in the dermatomyositis. J Dermatol. 1999;26:608‐610.

- Ghali FE, Reed AM, Groben PA, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:270-272.

- Molnar K, Kemeny L, Korom I, et al. Panniculitis in dermatomyositis: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:161‐163.

- Ishikawa O, Tamura A, Ryuzaki K, et al. Membranocystic changes in the panniculitis of dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:773-776.

- Sabroe RA, Wallington TB, Kennedy CT. Dermatomyositis treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins and associated with panniculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:164-167.

- Neidenbach PJ, Sahn EE, Helton J. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:305-307.

- Fusade T, Belanyi P, Joly P, et al. Subcutaneous changes in dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:451-453.

- Winkelmann WJ, Billick RC, Srolovitz H. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:127-128.

- Commens C, O’Neill P, Walker G. Dermatomyositis associated with multifocal lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:966-969.

- Raimer SS, Solomon AR, Daniels JC. Polymyositis presenting with panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2 pt 2):366‐369.

- Feldman D, Hochberg MC, Zizic TM, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis in adult polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:85-89.

- Kimura S, Fukuyama Y. Tubular cytoplasmic inclusions in a case of childhood dermatomyositis with migratory subcutaneous nodules. Eur J Pediatr. 1977;125:275-283.

- Weber FP, Gray AMH. Chronic relapsing polydermatomyositis with predominant involvement of the subcutaneous fat. Br J Dermatol. 1924;36:544-560.

- Santos‐Briz A, Calle A, Linos K, et al. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 18 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1352-1359.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Girouard SD, Velez NF, Penson RT, et al. Panniculitis associated with dermatomyositis and recurrent ovarian cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:740-744.

- van Dongen HM, van Vugt RM, Stoof TJ. Extensive persistent panniculitis in the context of dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26:E187-E188.

- Choi YJ, Yoo WH. Panniculitis, a rare presentation of onset and exacerbation of juvenile dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33:367-371.

- Azevedo PO, Castellen NR, Salai AF, et al. Panniculitis associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:119-121.

- Agulló A, Hinds B, Larrea M, et al. Livedo racemosa, reticulated ulcerations, panniculitis and violaceous plaques in a 46-year-old woman. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:47-49.

- Hattori Y, Matsuyama K, Takahashi T, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis presenting with cellulitis-like erythema on the mandible as an initial symptom. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018;10:110-114.

- Hasegawa A, Shimomura Y, Kibune N, et al. Panniculitis as the initial manifestation of dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibody. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:551-553.

- Salman A, Kasapcopur O, Ergun T, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis: report of a case and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2016;43:951-953.

- Carroll M, Mellick N, Wagner G. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a case report. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:224‐226.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kulthanan K, Manapajon A. Calcific panniculitis and nasopharyngeal cancer-associated adult-onset dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Springerplus. 2015;4:201.

- Otero Rivas MM, Vicente Villa A, González Lara L, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:574-575.

- Yanaba K, Tanito K, Hamaguchi Y, et al. Anti‐transcription intermediary factor‐1γ/α/β antibody‐positive dermatomyositis associated with multiple panniculitis lesions. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;20:1831-1834.

- Pau-Charles I, Moreno PJ, Ortiz-Ibanez K, et al. Anti-MDA5 positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis presenting with severe cardiomyopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1097-1102.

- Lamb R, Digby S, Stewart W, et al. Cutaneous ulceration: more than skin deep? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:443-445.

- Arias M, Hernández MI, Cunha LG, et al. Panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:146-148.

- Hemmi S, Kushida R, Nishimura H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of panniculitis in dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:151-153.

- Geddes MR, Sinnreich M, Chalk C. Minocycline-induced dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:547-549.

- Abdul‐Wahab A, Holden CA, Harland C, et al Calcific panniculitis in adult‐onset dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E854-E856.

- Carneiro S, Alvim G, Resende P, et al. Dermatomyositis with panniculitis. Skinmed. 2007;6:46-47.

- Carrera E, Lobrinus JA, Spertini O, et al. Dermatomyositis, lobarpanniculitis and inflammatory myopathy with abundant macrophages. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:468-471.

- Lin JH, Chu CY, Lin RY. Panniculitis in adult onset dermatomyositis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Sinica. 2006;24:194-200.

- Chen GY, Liu MF, Lee JY, et al. Combination of massive mucinosis, dermatomyositis, pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcer, bullae and fatal intestinal vasculopathy in a young female. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:396-400.

- Nakamori A, Yamaguchi Y, Kurimoto I, et al. Vesiculobullous dermatomyositis with panniculitis without muscle disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1136-1139.

- Solans R, Cortés J, Selva A, et al. Panniculitis: a cutaneous manifestation of dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:S148-S150.

- Chao YY, Yang LJ. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:141-144.

- Lee MW, Lim YS, Choi JH, et al. Panniculitis showing membranocystic changes in the dermatomyositis. J Dermatol. 1999;26:608‐610.

- Ghali FE, Reed AM, Groben PA, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:270-272.

- Molnar K, Kemeny L, Korom I, et al. Panniculitis in dermatomyositis: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:161‐163.

- Ishikawa O, Tamura A, Ryuzaki K, et al. Membranocystic changes in the panniculitis of dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:773-776.

- Sabroe RA, Wallington TB, Kennedy CT. Dermatomyositis treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins and associated with panniculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:164-167.

- Neidenbach PJ, Sahn EE, Helton J. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:305-307.

- Fusade T, Belanyi P, Joly P, et al. Subcutaneous changes in dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:451-453.

- Winkelmann WJ, Billick RC, Srolovitz H. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:127-128.

- Commens C, O’Neill P, Walker G. Dermatomyositis associated with multifocal lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:966-969.

- Raimer SS, Solomon AR, Daniels JC. Polymyositis presenting with panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2 pt 2):366‐369.

- Feldman D, Hochberg MC, Zizic TM, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis in adult polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:85-89.

- Kimura S, Fukuyama Y. Tubular cytoplasmic inclusions in a case of childhood dermatomyositis with migratory subcutaneous nodules. Eur J Pediatr. 1977;125:275-283.

- Weber FP, Gray AMH. Chronic relapsing polydermatomyositis with predominant involvement of the subcutaneous fat. Br J Dermatol. 1924;36:544-560.

- Santos‐Briz A, Calle A, Linos K, et al. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 18 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1352-1359.

Practice Points

- Clinical panniculitis is a rare subcutaneous manifestation of dermatomyositis (DM) that dermatologists must consider when evaluating patients with this condition.

- Panniculitis can precede, occur simultaneously with, or develop up to 5 years after onset of DM.

- Many patients suffer from treatment-resistant panniculitis in DM, suggesting that therapeutic management of this condition may require long-term and more aggressive treatment modalities.

COVID-19: Delta variant is raising the stakes

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people desperately needed

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

Like many colleagues, I have been working to change the minds and behaviors of acquaintances and patients who are opting to forgo a COVID vaccine. The large numbers of these unvaccinated Americans, combined with the surging Delta coronavirus variant, are endangering the health of us all.

When I spoke with the 22-year-old daughter of a family friend about what was holding her back, she told me that she would “never” get vaccinated. I shared my vaccination experience and told her that, except for a sore arm both times for a day, I felt no side effects. Likewise, I said, all of my adult family members are vaccinated, and everyone is fine. She was neither moved nor convinced.

Finally, I asked her whether she attended school (knowing that she was a college graduate), and she said “yes.” So I told her that all 50 states require children attending public schools to be vaccinated for diseases such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and the chickenpox – with certain religious, philosophical, and medical exemptions. Her response was simple: “I didn’t know that. Anyway, my parents were in charge.” Suddenly, her thinking shifted. “You’re right,” she said. She got a COVID shot the next day. Success for me.

When I asked another acquaintance whether he’d been vaccinated, he said he’d heard people were getting very sick from the vaccine – and was going to wait. Another gentleman I spoke with said that, at age 45, he was healthy. Besides, he added, he “doesn’t get sick.” When I asked another acquaintance about her vaccination status, her retort was that this was none of my business. So far, I’m batting about .300.

But as a physician, I believe that we – and other health care providers – must continue to encourage the people in our lives to care for themselves and others by getting vaccinated. One concrete step advised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is to help people make an appointment for a shot. Some sites no longer require appointments, and New York City, for example, offers in-home vaccinations to all NYC residents.

Also, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Aug. 3 the “Key to NYC Pass,” which he called a “first-in-the-nation approach” to vaccination. Under this new policy, vaccine-eligible people aged 12 and older in New York City will need to prove with a vaccination card, an app, or an Excelsior Pass that they have received at least one dose of vaccine before participating in indoor venues such as restaurants, bars, gyms, and movie theaters within the city. Mayor de Blasio said the new initiative, which is still being finalized, will be phased in starting the week of Aug. 16. I see this as a major public health measure that will keep people healthy – and get them vaccinated.

The medical community should support this move by the city of New York and encourage people to follow CDC guidance on wearing face coverings in public settings, especially schools. New research shows that physicians continue to be among the most trusted sources of vaccine-related information.

Another strategy we might use is to point to the longtime practices of surgeons. We could ask: Why do surgeons wear face masks in the operating room? For years, these coverings have been used to protect patients from the nasal and oral bacteria generated by operating room staff. Likewise, we can tell those who remain on the fence that, by wearing face masks, we are protecting others from all variants, but specifically from Delta – which the CDC now says can be transmitted by people who are fully vaccinated.

Why did the CDC lift face mask guidance for fully vaccinated people in indoor spaces in May? It was clear to me and other colleagues back then that this was not a good idea. Despite that guidance, I continued to wear a mask in public places and advised anyone who would listen to do the same.

The development of vaccines in the 20th and 21st centuries has saved millions of lives. The World Health Organization reports that 4 million to 5 million lives a year are saved by immunizations. In addition, research shows that, before the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, vaccinations led to the eradication of smallpox and polio, and a 74% drop in measles-related deaths between 2004 and 2014.

Protecting the most vulnerable

With COVID cases surging, particularly in parts of the South and Midwest, I am concerned about children under age 12 who do not yet qualify for a vaccine. Certainly, unvaccinated parents could spread the virus to their young children, and unvaccinated children could transmit the illness to immediate and extended family. Now that the CDC has said that there is a risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection among fully vaccinated people in areas with high community transmission, should we worry about unvaccinated young children with vaccinated parents? I recently spoke with James C. Fagin, MD, a board-certified pediatrician and immunologist, to get his views on this issue.

Dr. Fagin, who is retired, said he is in complete agreement with the Food and Drug Administration when it comes to approving medications for children. However, given the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to get our children back to in-person learning, he would like to see the approval process safely expedited. Large numbers of unvaccinated people increase the pool for the Delta variant and could increase the likelihood of a new variant that is more resistant to the vaccines, said Dr. Fagin, former chief of academic pediatrics at North Shore University Hospital and a former faculty member in the allergy/immunology division of Cohen Children’s Medical Center, both in New York.

Meanwhile, I agree with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendations that children, teachers, and school staff and other adults in school settings should wear masks regardless of vaccination status. Kids adjust well to masks – as my grandchildren and their friends have.

The bottom line is that we need to get as many people as possible vaccinated as soon as possible, and while doing so, we must continue to wear face coverings in public spaces. As clinicians, we have a special responsibility to do all that we can to change minds – and behaviors.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist who has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.