User login

Seen or viewed: A black hematologist’s perspective

After a long day in hematology clinic, I skimmed the inpatient list to see if any of my patients had been admitted. Seeing Ms. Short’s name (changed for privacy), a delightful African American woman I met during my early days of fellowship, had me making the trek to the hospital. She was living with multiple myeloma complicated by extramedullary manifestations that had significantly impacted her quality of life.

During our first encounter, she showed me a growing left subscapular mass the size of an orange that was erythematous, hot, painful, and irritated. As an enthusiastic first-year fellow, I wanted to be aggressive in addressing her concerns in response to her obvious distress about this mass. Ultimately, she left clinic with antibiotics and an appointment with radiation oncology to see if they could use radiation to shrink the subscapular mass.

When I went back in to discuss the plan with her, she grabbed my hand, looked me in my eyes and said: “Thank you, I’ve been mentioning this for a while and you’re the first person to get something done about it.” In that moment I knew that she felt seen.

By the time I made it over to the hospital, she was getting settled in her room to start another cycle of cytoreductive chemotherapy.

“I told them I had a Black doctor!” she exclaimed as I walked into her hospital room. “I was looking for you today in clinic ... I kept telling them I had a Black doctor, but the nurses kept telling me no, that there were only Black nurse practitioners.” She had repeatedly told the staff that I, her “Black doctor,” did indeed exist, and she went on to describe me as “you know, the [heavy-chested] and short Black doctor I saw early this fall.” To this day, her description still makes me chuckle.

Though I laughed at her description, it hurt that I had worked in a clinic for 6 months yet was invisible. Initially disappointed, I left Ms. Short’s room with a smile on my face, energized and encouraged.

My time with Ms. Short prompted me to ruminate on my experience as a Black physician. To put it in perspective, 5% of all physicians are Black, 2% are Black women, and 2.3% are oncologists, even though African Americans make up 13% of the general U.S. population. I reside in a space where I am simultaneously scrutinized because I am one of the few (or the only) Black physicians in the building, and yet I am invisible because my colleagues and coworkers routinely ignore my presence.

Black physicians, let alone hematologists, are so rare that nurses often cannot fathom that a Black woman could be more than a nurse practitioner. Sadly, this is the tip of the iceberg of some of the negative experiences I, and other Black doctors, have had.

How I present myself must be carefully curated to make progress in my career. My peers and superiors seem to hear me better when my hair is straight and not in its naturally curly state. My introversion has been interpreted as being standoffish or disinterested. Any tone other than happy is interpreted as “aggressive” or “angry”. Talking “too much” to Black support staff was reported to my program, as it was viewed as suspicious, disruptive, and “appearances matter”.

I am also expected to be nurturing in ways that White physicians are not required to be. In my presence, White physicians have denigrated an entire patient population that is disproportionately Black by calling them “sicklers.” If there is an interpersonal conflict, I must think about the long-term consequences of voicing my perspective. My non-Black colleagues do not have to think about these things.

Imagine dealing with this at work, then on your commute home being worried about the reality that you may be pulled over and become the next name on the ever-growing list of Black women and men murdered at the hands of police. The cognitive and emotional impact of being invisible is immense and cumulative over the years.

My Blackness creates a bias of inferiority that cannot be overcome by respectability, compliance, professionalism, training, and expertise. This is glaringly apparent on both sides of the physician-patient relationship. Black patients’ concerns are routinely overlooked and dismissed, as seen with Ms. Short, and are reflected in the Black maternal death rate, pain control in Black versus White patients, and personal experience as a patient and an advocate for my family members.

Patients have looked me in the face and said, “all lives matter,” displaying their refusal to recognize that systematic racism and inequality exist. These facts and experiences are the antithesis of “primum non nocere.”

Sadly, my and Ms. Short’s experiences are not singular ones, and racial bias in medicine is a diagnosed, but untreated cancer. Like the malignancies I treat, ignoring the problem has not made it go away; therefore, it continues to fester and spread, causing more destruction. It is of great importance and concern that all physicians recognize, reflect, and correct their implicit biases not only toward their patients, but also colleagues and trainees.

It seems that health care professionals can talk the talk, as many statements have been made against racism and implicit bias in medicine, but can we take true and meaningful action to begin the journey to equity and justice?

I would like to thank Adrienne Glover, MD, MaKenzie Hodge, MD, Maranatha McLean, MD, and Darion Showell, MD, for our stimulating conversations that helped me put pen to paper. I’d also like to thank my family for being my editors.

Daphanie D. Taylor, MD, is a hematology/oncology fellow PGY-6 at Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C.

References and further reading

Roy L. “‘It’s My Calling To Change The Statistics’: Why We Need More Black Female Physicians.” Forbes Magazine, 27 Feb. 2020.

“Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019.” Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019.

“Facts & Figures: Diversity in Oncology.” American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Jan 16.

After a long day in hematology clinic, I skimmed the inpatient list to see if any of my patients had been admitted. Seeing Ms. Short’s name (changed for privacy), a delightful African American woman I met during my early days of fellowship, had me making the trek to the hospital. She was living with multiple myeloma complicated by extramedullary manifestations that had significantly impacted her quality of life.

During our first encounter, she showed me a growing left subscapular mass the size of an orange that was erythematous, hot, painful, and irritated. As an enthusiastic first-year fellow, I wanted to be aggressive in addressing her concerns in response to her obvious distress about this mass. Ultimately, she left clinic with antibiotics and an appointment with radiation oncology to see if they could use radiation to shrink the subscapular mass.

When I went back in to discuss the plan with her, she grabbed my hand, looked me in my eyes and said: “Thank you, I’ve been mentioning this for a while and you’re the first person to get something done about it.” In that moment I knew that she felt seen.

By the time I made it over to the hospital, she was getting settled in her room to start another cycle of cytoreductive chemotherapy.

“I told them I had a Black doctor!” she exclaimed as I walked into her hospital room. “I was looking for you today in clinic ... I kept telling them I had a Black doctor, but the nurses kept telling me no, that there were only Black nurse practitioners.” She had repeatedly told the staff that I, her “Black doctor,” did indeed exist, and she went on to describe me as “you know, the [heavy-chested] and short Black doctor I saw early this fall.” To this day, her description still makes me chuckle.

Though I laughed at her description, it hurt that I had worked in a clinic for 6 months yet was invisible. Initially disappointed, I left Ms. Short’s room with a smile on my face, energized and encouraged.

My time with Ms. Short prompted me to ruminate on my experience as a Black physician. To put it in perspective, 5% of all physicians are Black, 2% are Black women, and 2.3% are oncologists, even though African Americans make up 13% of the general U.S. population. I reside in a space where I am simultaneously scrutinized because I am one of the few (or the only) Black physicians in the building, and yet I am invisible because my colleagues and coworkers routinely ignore my presence.

Black physicians, let alone hematologists, are so rare that nurses often cannot fathom that a Black woman could be more than a nurse practitioner. Sadly, this is the tip of the iceberg of some of the negative experiences I, and other Black doctors, have had.

How I present myself must be carefully curated to make progress in my career. My peers and superiors seem to hear me better when my hair is straight and not in its naturally curly state. My introversion has been interpreted as being standoffish or disinterested. Any tone other than happy is interpreted as “aggressive” or “angry”. Talking “too much” to Black support staff was reported to my program, as it was viewed as suspicious, disruptive, and “appearances matter”.

I am also expected to be nurturing in ways that White physicians are not required to be. In my presence, White physicians have denigrated an entire patient population that is disproportionately Black by calling them “sicklers.” If there is an interpersonal conflict, I must think about the long-term consequences of voicing my perspective. My non-Black colleagues do not have to think about these things.

Imagine dealing with this at work, then on your commute home being worried about the reality that you may be pulled over and become the next name on the ever-growing list of Black women and men murdered at the hands of police. The cognitive and emotional impact of being invisible is immense and cumulative over the years.

My Blackness creates a bias of inferiority that cannot be overcome by respectability, compliance, professionalism, training, and expertise. This is glaringly apparent on both sides of the physician-patient relationship. Black patients’ concerns are routinely overlooked and dismissed, as seen with Ms. Short, and are reflected in the Black maternal death rate, pain control in Black versus White patients, and personal experience as a patient and an advocate for my family members.

Patients have looked me in the face and said, “all lives matter,” displaying their refusal to recognize that systematic racism and inequality exist. These facts and experiences are the antithesis of “primum non nocere.”

Sadly, my and Ms. Short’s experiences are not singular ones, and racial bias in medicine is a diagnosed, but untreated cancer. Like the malignancies I treat, ignoring the problem has not made it go away; therefore, it continues to fester and spread, causing more destruction. It is of great importance and concern that all physicians recognize, reflect, and correct their implicit biases not only toward their patients, but also colleagues and trainees.

It seems that health care professionals can talk the talk, as many statements have been made against racism and implicit bias in medicine, but can we take true and meaningful action to begin the journey to equity and justice?

I would like to thank Adrienne Glover, MD, MaKenzie Hodge, MD, Maranatha McLean, MD, and Darion Showell, MD, for our stimulating conversations that helped me put pen to paper. I’d also like to thank my family for being my editors.

Daphanie D. Taylor, MD, is a hematology/oncology fellow PGY-6 at Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C.

References and further reading

Roy L. “‘It’s My Calling To Change The Statistics’: Why We Need More Black Female Physicians.” Forbes Magazine, 27 Feb. 2020.

“Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019.” Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019.

“Facts & Figures: Diversity in Oncology.” American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Jan 16.

After a long day in hematology clinic, I skimmed the inpatient list to see if any of my patients had been admitted. Seeing Ms. Short’s name (changed for privacy), a delightful African American woman I met during my early days of fellowship, had me making the trek to the hospital. She was living with multiple myeloma complicated by extramedullary manifestations that had significantly impacted her quality of life.

During our first encounter, she showed me a growing left subscapular mass the size of an orange that was erythematous, hot, painful, and irritated. As an enthusiastic first-year fellow, I wanted to be aggressive in addressing her concerns in response to her obvious distress about this mass. Ultimately, she left clinic with antibiotics and an appointment with radiation oncology to see if they could use radiation to shrink the subscapular mass.

When I went back in to discuss the plan with her, she grabbed my hand, looked me in my eyes and said: “Thank you, I’ve been mentioning this for a while and you’re the first person to get something done about it.” In that moment I knew that she felt seen.

By the time I made it over to the hospital, she was getting settled in her room to start another cycle of cytoreductive chemotherapy.

“I told them I had a Black doctor!” she exclaimed as I walked into her hospital room. “I was looking for you today in clinic ... I kept telling them I had a Black doctor, but the nurses kept telling me no, that there were only Black nurse practitioners.” She had repeatedly told the staff that I, her “Black doctor,” did indeed exist, and she went on to describe me as “you know, the [heavy-chested] and short Black doctor I saw early this fall.” To this day, her description still makes me chuckle.

Though I laughed at her description, it hurt that I had worked in a clinic for 6 months yet was invisible. Initially disappointed, I left Ms. Short’s room with a smile on my face, energized and encouraged.

My time with Ms. Short prompted me to ruminate on my experience as a Black physician. To put it in perspective, 5% of all physicians are Black, 2% are Black women, and 2.3% are oncologists, even though African Americans make up 13% of the general U.S. population. I reside in a space where I am simultaneously scrutinized because I am one of the few (or the only) Black physicians in the building, and yet I am invisible because my colleagues and coworkers routinely ignore my presence.

Black physicians, let alone hematologists, are so rare that nurses often cannot fathom that a Black woman could be more than a nurse practitioner. Sadly, this is the tip of the iceberg of some of the negative experiences I, and other Black doctors, have had.

How I present myself must be carefully curated to make progress in my career. My peers and superiors seem to hear me better when my hair is straight and not in its naturally curly state. My introversion has been interpreted as being standoffish or disinterested. Any tone other than happy is interpreted as “aggressive” or “angry”. Talking “too much” to Black support staff was reported to my program, as it was viewed as suspicious, disruptive, and “appearances matter”.

I am also expected to be nurturing in ways that White physicians are not required to be. In my presence, White physicians have denigrated an entire patient population that is disproportionately Black by calling them “sicklers.” If there is an interpersonal conflict, I must think about the long-term consequences of voicing my perspective. My non-Black colleagues do not have to think about these things.

Imagine dealing with this at work, then on your commute home being worried about the reality that you may be pulled over and become the next name on the ever-growing list of Black women and men murdered at the hands of police. The cognitive and emotional impact of being invisible is immense and cumulative over the years.

My Blackness creates a bias of inferiority that cannot be overcome by respectability, compliance, professionalism, training, and expertise. This is glaringly apparent on both sides of the physician-patient relationship. Black patients’ concerns are routinely overlooked and dismissed, as seen with Ms. Short, and are reflected in the Black maternal death rate, pain control in Black versus White patients, and personal experience as a patient and an advocate for my family members.

Patients have looked me in the face and said, “all lives matter,” displaying their refusal to recognize that systematic racism and inequality exist. These facts and experiences are the antithesis of “primum non nocere.”

Sadly, my and Ms. Short’s experiences are not singular ones, and racial bias in medicine is a diagnosed, but untreated cancer. Like the malignancies I treat, ignoring the problem has not made it go away; therefore, it continues to fester and spread, causing more destruction. It is of great importance and concern that all physicians recognize, reflect, and correct their implicit biases not only toward their patients, but also colleagues and trainees.

It seems that health care professionals can talk the talk, as many statements have been made against racism and implicit bias in medicine, but can we take true and meaningful action to begin the journey to equity and justice?

I would like to thank Adrienne Glover, MD, MaKenzie Hodge, MD, Maranatha McLean, MD, and Darion Showell, MD, for our stimulating conversations that helped me put pen to paper. I’d also like to thank my family for being my editors.

Daphanie D. Taylor, MD, is a hematology/oncology fellow PGY-6 at Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C.

References and further reading

Roy L. “‘It’s My Calling To Change The Statistics’: Why We Need More Black Female Physicians.” Forbes Magazine, 27 Feb. 2020.

“Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019.” Association of American Medical Colleges, 2019.

“Facts & Figures: Diversity in Oncology.” American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2020 Jan 16.

What Tom Brady and Patrick Mahomes can teach us about physicians

Warning: This article will be about Tom Brady. If you love Tom Brady, hate Tom Brady, previously loved and now hate Tom Brady, I’m just warning you so you’ll be in the right frame of mind to continue. (If you don’t know who Tom Brady is, he’s Gisele’s husband).

Brady, who plays for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, has played in the NFL for 21 seasons, an unbelievable number given the average career for a quarterback is 3 years. He’s 43 years old and was the oldest player in a Super Bowl, ever. He faced Patrick Mahomes, the quarterback for the opposing Kansas City Chiefs. Mahomes is one of the most athletic and talented quarterbacks of all time, and Mahomes is nearly 20 years younger than Brady. Yet, in a shot heard around the NFL world, Brady won.

But, was a Brady victory so shocking? Hot-shot residents may have a lot of moxie and talent, but experienced doctors often prevail by simply making sound decisions and avoiding mistakes. In our department, we’ve been discussing this lately: We’re hiring two dermatologists and we’re fortunate to have some amazing candidates apply. Some, like Mahomes, are young all-stars with outstanding ability and potential, right out of residency. Others, Brady-like, have been in practice for years and are ready to move to a new franchise.

Our medical group’s experiences are probably similar to many practices: New physicians out of residency often bring energy, inspiration, and ease with the latest therapies, devices, and surgical techniques. Yet, they sometimes struggle with efficiency and unforced errors. Experienced physicians might not know what’s hot, but they can often see where the best course of action lies, understanding not only the physiology but also the patient in ways that only experience can teach you. Fortunately, for those like me who’ve crossed midlife, there doesn’t seem to be an upper limit to experience – it is possible to keep getting better. Yes, I’m just like Tom Brady. (I wrote this article just to print that line.)

Some of the best doctors I’ve ever seen in action were emeritus physicians. In medical school at Wake Forest University, one of my professors was Dr. Eben Alexander. A retired neurosurgeon, he taught a case-based critical thinking skills class. I recall his brilliant insight and coaching, working through cases that had nothing to do with the brain or with surgery. He used his vast experience and wisdom to teach us how to practice medicine. He was, at that time, nearly 90 years old. Despite having been retired for decades, he was still writing articles and editing journals. He was inspiring. For a minute, he had me thinking I’d like to be a neurosurgeon, so I could be just like Eben Alexander. I did not, but I learned things from him that still impact my practice as a dermatologist today.

I’m sure you’ve had similar experiences of older colleagues or mentors who were the best doctor in the clinic or the O.R. They are the Dr. Anthony Faucis, not just practicing, but leading while in their 8th or 9th decade. We are all so fortunate that they keep playing.

We’ve not made our final choices on whom to hire, but with two positions, I expect we’ll choose both a young doctor and an experienced one to add to our team. It will be fun to watch and learn from them. Just like it will be fun to watch Tom Brady in the Super Bowl again next year.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Warning: This article will be about Tom Brady. If you love Tom Brady, hate Tom Brady, previously loved and now hate Tom Brady, I’m just warning you so you’ll be in the right frame of mind to continue. (If you don’t know who Tom Brady is, he’s Gisele’s husband).

Brady, who plays for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, has played in the NFL for 21 seasons, an unbelievable number given the average career for a quarterback is 3 years. He’s 43 years old and was the oldest player in a Super Bowl, ever. He faced Patrick Mahomes, the quarterback for the opposing Kansas City Chiefs. Mahomes is one of the most athletic and talented quarterbacks of all time, and Mahomes is nearly 20 years younger than Brady. Yet, in a shot heard around the NFL world, Brady won.

But, was a Brady victory so shocking? Hot-shot residents may have a lot of moxie and talent, but experienced doctors often prevail by simply making sound decisions and avoiding mistakes. In our department, we’ve been discussing this lately: We’re hiring two dermatologists and we’re fortunate to have some amazing candidates apply. Some, like Mahomes, are young all-stars with outstanding ability and potential, right out of residency. Others, Brady-like, have been in practice for years and are ready to move to a new franchise.

Our medical group’s experiences are probably similar to many practices: New physicians out of residency often bring energy, inspiration, and ease with the latest therapies, devices, and surgical techniques. Yet, they sometimes struggle with efficiency and unforced errors. Experienced physicians might not know what’s hot, but they can often see where the best course of action lies, understanding not only the physiology but also the patient in ways that only experience can teach you. Fortunately, for those like me who’ve crossed midlife, there doesn’t seem to be an upper limit to experience – it is possible to keep getting better. Yes, I’m just like Tom Brady. (I wrote this article just to print that line.)

Some of the best doctors I’ve ever seen in action were emeritus physicians. In medical school at Wake Forest University, one of my professors was Dr. Eben Alexander. A retired neurosurgeon, he taught a case-based critical thinking skills class. I recall his brilliant insight and coaching, working through cases that had nothing to do with the brain or with surgery. He used his vast experience and wisdom to teach us how to practice medicine. He was, at that time, nearly 90 years old. Despite having been retired for decades, he was still writing articles and editing journals. He was inspiring. For a minute, he had me thinking I’d like to be a neurosurgeon, so I could be just like Eben Alexander. I did not, but I learned things from him that still impact my practice as a dermatologist today.

I’m sure you’ve had similar experiences of older colleagues or mentors who were the best doctor in the clinic or the O.R. They are the Dr. Anthony Faucis, not just practicing, but leading while in their 8th or 9th decade. We are all so fortunate that they keep playing.

We’ve not made our final choices on whom to hire, but with two positions, I expect we’ll choose both a young doctor and an experienced one to add to our team. It will be fun to watch and learn from them. Just like it will be fun to watch Tom Brady in the Super Bowl again next year.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Warning: This article will be about Tom Brady. If you love Tom Brady, hate Tom Brady, previously loved and now hate Tom Brady, I’m just warning you so you’ll be in the right frame of mind to continue. (If you don’t know who Tom Brady is, he’s Gisele’s husband).

Brady, who plays for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, has played in the NFL for 21 seasons, an unbelievable number given the average career for a quarterback is 3 years. He’s 43 years old and was the oldest player in a Super Bowl, ever. He faced Patrick Mahomes, the quarterback for the opposing Kansas City Chiefs. Mahomes is one of the most athletic and talented quarterbacks of all time, and Mahomes is nearly 20 years younger than Brady. Yet, in a shot heard around the NFL world, Brady won.

But, was a Brady victory so shocking? Hot-shot residents may have a lot of moxie and talent, but experienced doctors often prevail by simply making sound decisions and avoiding mistakes. In our department, we’ve been discussing this lately: We’re hiring two dermatologists and we’re fortunate to have some amazing candidates apply. Some, like Mahomes, are young all-stars with outstanding ability and potential, right out of residency. Others, Brady-like, have been in practice for years and are ready to move to a new franchise.

Our medical group’s experiences are probably similar to many practices: New physicians out of residency often bring energy, inspiration, and ease with the latest therapies, devices, and surgical techniques. Yet, they sometimes struggle with efficiency and unforced errors. Experienced physicians might not know what’s hot, but they can often see where the best course of action lies, understanding not only the physiology but also the patient in ways that only experience can teach you. Fortunately, for those like me who’ve crossed midlife, there doesn’t seem to be an upper limit to experience – it is possible to keep getting better. Yes, I’m just like Tom Brady. (I wrote this article just to print that line.)

Some of the best doctors I’ve ever seen in action were emeritus physicians. In medical school at Wake Forest University, one of my professors was Dr. Eben Alexander. A retired neurosurgeon, he taught a case-based critical thinking skills class. I recall his brilliant insight and coaching, working through cases that had nothing to do with the brain or with surgery. He used his vast experience and wisdom to teach us how to practice medicine. He was, at that time, nearly 90 years old. Despite having been retired for decades, he was still writing articles and editing journals. He was inspiring. For a minute, he had me thinking I’d like to be a neurosurgeon, so I could be just like Eben Alexander. I did not, but I learned things from him that still impact my practice as a dermatologist today.

I’m sure you’ve had similar experiences of older colleagues or mentors who were the best doctor in the clinic or the O.R. They are the Dr. Anthony Faucis, not just practicing, but leading while in their 8th or 9th decade. We are all so fortunate that they keep playing.

We’ve not made our final choices on whom to hire, but with two positions, I expect we’ll choose both a young doctor and an experienced one to add to our team. It will be fun to watch and learn from them. Just like it will be fun to watch Tom Brady in the Super Bowl again next year.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Cluster of hyperpigmented spots

A large hyperpigmented patch with overlying darker macules and papules is characteristic of a speckled lentiginous nevus (SLN), also called a nevus spilus.

SLN is a cafe-au-lait˗like nevus that initially appears with a hyperpigmented background, usually at or around birth. Later, a speckled or polka-dot pattern of dark macules and papules appears over time. SLN is believed to be a form of congenital melanocytic nevus. There are believed to be 2 subtypes of SLN: nevus spilus maculosus and nevus spilus papulosus.

The maculosus subtype is characterized by flat and evenly distributed macules, that look like polka-dots. Histopathology reveals elongated interpapillary ridges containing increased numbers of melanocytes that form nests at the dermo-epidermal junction.

The papulosus subtype (which this patient had) is differentiated by superimposed speckles and papules whose size and distribution vary; this subype looks similar to a starry sky. Histopathology of the papulosus subtype shows melanocytic nevi of either the dermal or compound type—hence the papular appearance.

Given that SLN is a congenital melanocytic nevus, there is a small risk of transformation to malignant melanoma. The papulosus subtype is believed to have a more dynamic course with more lesions appearing over time. The maculosus subtype is considered to have a slightly higher risk of transformation into malignant melanoma compared to the papulosus subtype.

It is important to recognize that SLN is a distinct clinical entity, rather than a large irregular nevus. Mistaking it for a large suspicious nevus would require multiple biopsies of the most suspicious areas or excision of the entire lesion. Treatment for SLN includes serial surveillance with biopsy or excision of any suspicious areas that arise. In this case, the patient did not have any areas warranting biopsy, so the plan was to have him followed with annual clinical surveillance.

Photo and text courtesy of Erik Unruh, MD, MPH, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Happl, R. Speckled lentiginous naevus: which of the two disorders do you mean? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:133-135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02966.x.

A large hyperpigmented patch with overlying darker macules and papules is characteristic of a speckled lentiginous nevus (SLN), also called a nevus spilus.

SLN is a cafe-au-lait˗like nevus that initially appears with a hyperpigmented background, usually at or around birth. Later, a speckled or polka-dot pattern of dark macules and papules appears over time. SLN is believed to be a form of congenital melanocytic nevus. There are believed to be 2 subtypes of SLN: nevus spilus maculosus and nevus spilus papulosus.

The maculosus subtype is characterized by flat and evenly distributed macules, that look like polka-dots. Histopathology reveals elongated interpapillary ridges containing increased numbers of melanocytes that form nests at the dermo-epidermal junction.

The papulosus subtype (which this patient had) is differentiated by superimposed speckles and papules whose size and distribution vary; this subype looks similar to a starry sky. Histopathology of the papulosus subtype shows melanocytic nevi of either the dermal or compound type—hence the papular appearance.

Given that SLN is a congenital melanocytic nevus, there is a small risk of transformation to malignant melanoma. The papulosus subtype is believed to have a more dynamic course with more lesions appearing over time. The maculosus subtype is considered to have a slightly higher risk of transformation into malignant melanoma compared to the papulosus subtype.

It is important to recognize that SLN is a distinct clinical entity, rather than a large irregular nevus. Mistaking it for a large suspicious nevus would require multiple biopsies of the most suspicious areas or excision of the entire lesion. Treatment for SLN includes serial surveillance with biopsy or excision of any suspicious areas that arise. In this case, the patient did not have any areas warranting biopsy, so the plan was to have him followed with annual clinical surveillance.

Photo and text courtesy of Erik Unruh, MD, MPH, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

A large hyperpigmented patch with overlying darker macules and papules is characteristic of a speckled lentiginous nevus (SLN), also called a nevus spilus.

SLN is a cafe-au-lait˗like nevus that initially appears with a hyperpigmented background, usually at or around birth. Later, a speckled or polka-dot pattern of dark macules and papules appears over time. SLN is believed to be a form of congenital melanocytic nevus. There are believed to be 2 subtypes of SLN: nevus spilus maculosus and nevus spilus papulosus.

The maculosus subtype is characterized by flat and evenly distributed macules, that look like polka-dots. Histopathology reveals elongated interpapillary ridges containing increased numbers of melanocytes that form nests at the dermo-epidermal junction.

The papulosus subtype (which this patient had) is differentiated by superimposed speckles and papules whose size and distribution vary; this subype looks similar to a starry sky. Histopathology of the papulosus subtype shows melanocytic nevi of either the dermal or compound type—hence the papular appearance.

Given that SLN is a congenital melanocytic nevus, there is a small risk of transformation to malignant melanoma. The papulosus subtype is believed to have a more dynamic course with more lesions appearing over time. The maculosus subtype is considered to have a slightly higher risk of transformation into malignant melanoma compared to the papulosus subtype.

It is important to recognize that SLN is a distinct clinical entity, rather than a large irregular nevus. Mistaking it for a large suspicious nevus would require multiple biopsies of the most suspicious areas or excision of the entire lesion. Treatment for SLN includes serial surveillance with biopsy or excision of any suspicious areas that arise. In this case, the patient did not have any areas warranting biopsy, so the plan was to have him followed with annual clinical surveillance.

Photo and text courtesy of Erik Unruh, MD, MPH, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Happl, R. Speckled lentiginous naevus: which of the two disorders do you mean? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:133-135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02966.x.

Happl, R. Speckled lentiginous naevus: which of the two disorders do you mean? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:133-135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02966.x.

When the X-Waiver gets X’ed: Implications for hospitalists

There are two pandemics permeating the United States: COVID-19 and addiction. To date, more than 468,000 people have died from COVID-19 in the U.S. In the 12-month period ending in May 2020, over 80,000 died from a drug related cause – the highest number ever recorded in a year. Many of these deaths involved opioids.

COVID-19 has worsened outcomes for people with addiction. There is less access to treatment, increased isolation, and worsening psychosocial and economic stressors. These factors may drive new, increased, or more risky substance use and return to use for people in recovery. As hospitalists, we have been responders in both COVID-19 and our country’s worsening overdose and addiction crisis.

In December 2020’s Journal of Hospital Medicine article “Converging Crises: Caring for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder in the time of COVID-19”, Dr. Honora Englander and her coauthors called on hospitalists to actively engage patients with substance use disorders during hospitalization. The article highlights the colliding crises of addiction and COVID-19 and provides eight practical approaches for hospitalists to address substance use disorders during the pandemic, including initiating buprenorphine for opioid withdrawal and prescribing it for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

Buprenorphine effectively treats opioid withdrawal, reduces OUD-related mortality, and decreases hospital readmissions related to OUD. To prescribe buprenorphine for OUD in the outpatient setting or on hospital discharge, providers need an X-Waiver. The X-Waiver is a result of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act 2000 (DATA 2000), which was enacted in 2000. It permits physicians to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD treatment after an 8-hour training. In 2016, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act extended buprenorphine prescribing to physician assistants (PAs) and advanced-practice nurses (APNs). However, PAs and APNs are required to complete a 24-hour training to receive the waiver.

On Jan. 14, 2021, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under the Trump administration announced it was removing the X-Waiver training previously required for physicians to prescribe this life-saving medication. However, on Jan. 20, 2021, the Biden administration froze the training requirement removal pending a 60-day review. The excitement about the waiver’s eradication further dampened on Jan. 25, when the plan was halted due to procedural factors coupled with the concern that HHS may not have the authority to void requirements mandated by Congress.

Many of us continue to be hopeful that the X-Waiver will soon be gone. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has committed to working with federal agencies to increase access to buprenorphine. The Biden administration also committed to addressing our country’s addiction crisis, including a plan to “make effective prevention, treatment, and recovery services available to all, including through a $125 billion federal investment.”

Despite the pause on HHS’s recent attempt to “X the X-Waiver,” we now have renewed attention and interest in this critical issue and an opportunity for greater and longer-lasting legislative impact. SHM supports that Congress repeal the legislative requirement for buprenorphine training dictated by DATA 2000 so that it cannot be rolled back by future administrations. To further increase access to buprenorphine treatment, the training requirement should be removed for all providers who care for individuals with OUD.

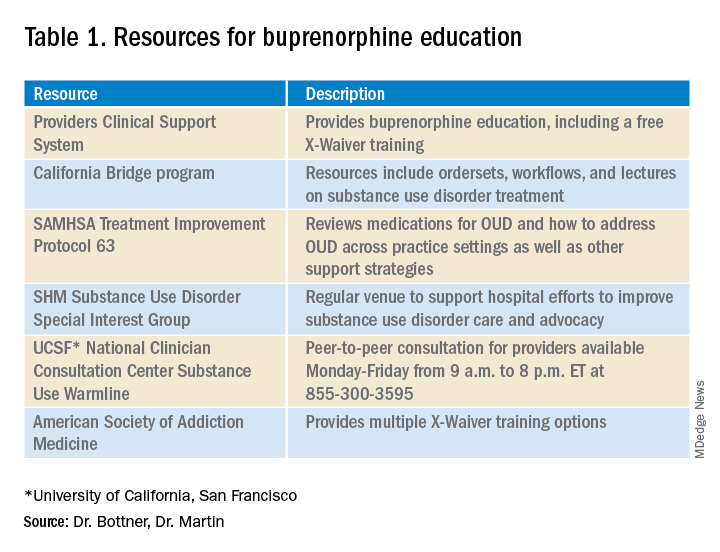

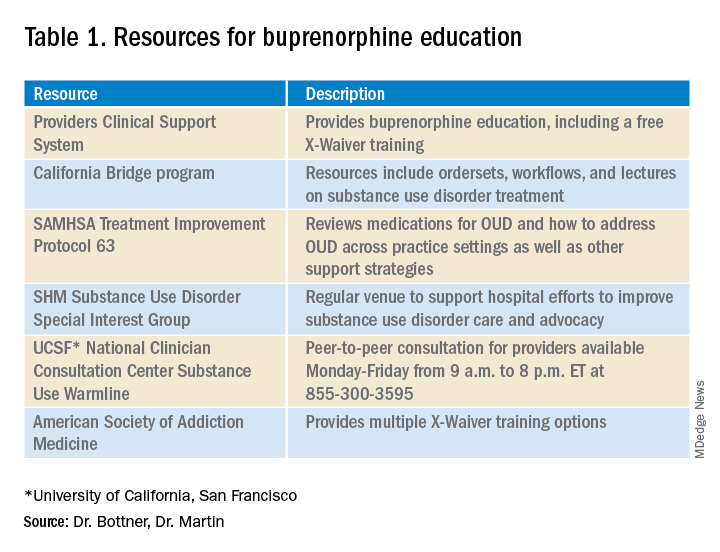

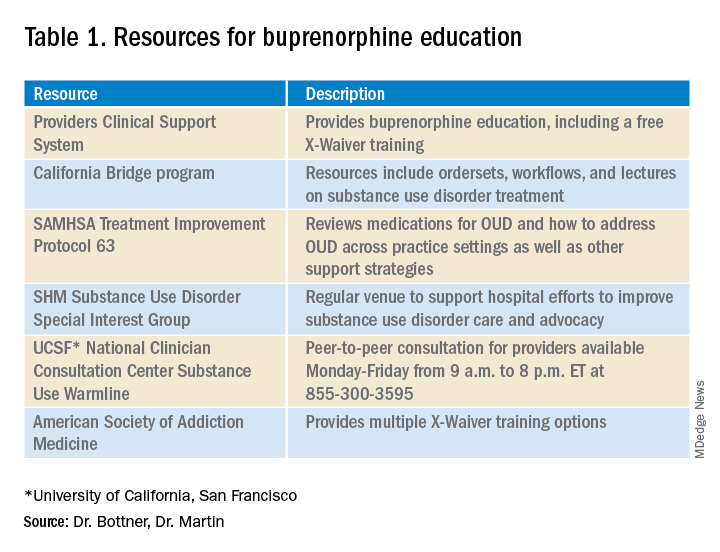

The X-Waiver has been a barrier to hospitalist adoption of this critical, life-saving medication. HHS’s stance to nix the waiver, though fleeting, should be interpreted as an urgent call to the medical community, including us as hospitalists, to learn about buprenorphine with the many resources available (see table 1). As hospital medicine providers, we can order buprenorphine for patients with OUD during hospitalization. It is discharge prescriptions that have been limited to providers with an X-Waiver.

What can we do now to prepare for the eventual X-Waiver training removal? We can start by educating ourselves with the resources listed in table 1. Those of us who are already buprenorphine champions could lead trainings in our home institutions. In a future without the waiver there will be more flexibility to develop hospitalist-focused buprenorphine trainings, as the previous ones were geared for outpatient providers. Hospitalist organizations could support hospitalist-specific buprenorphine trainings and extend the models to include additional medications for addiction.

There is a large body of evidence regarding buprenorphine’s safety and efficacy in OUD treatment. With a worsening overdose crisis, there have been increasing opioid-related hospitalizations. When new medications for diabetes, hypertension, or DVT treatment become available, as hospitalists we incorporate them into our toolbox. As buprenorphine becomes more accessible, we can be leaders in further adopting it (and other substance use disorder medications while we are at it) as our standard of care for people with OUD.

Dr. Bottner is a physician assistant in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin and director of the hospital’s Buprenorphine Team. Dr. Martin is a board-certified addiction medicine physician and hospitalist at University of California, San Francisco, and director of the Addiction Care Team at San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Bottner and Dr. Martin colead the SHM Substance Use Disorder Special Interest Group.

There are two pandemics permeating the United States: COVID-19 and addiction. To date, more than 468,000 people have died from COVID-19 in the U.S. In the 12-month period ending in May 2020, over 80,000 died from a drug related cause – the highest number ever recorded in a year. Many of these deaths involved opioids.

COVID-19 has worsened outcomes for people with addiction. There is less access to treatment, increased isolation, and worsening psychosocial and economic stressors. These factors may drive new, increased, or more risky substance use and return to use for people in recovery. As hospitalists, we have been responders in both COVID-19 and our country’s worsening overdose and addiction crisis.

In December 2020’s Journal of Hospital Medicine article “Converging Crises: Caring for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder in the time of COVID-19”, Dr. Honora Englander and her coauthors called on hospitalists to actively engage patients with substance use disorders during hospitalization. The article highlights the colliding crises of addiction and COVID-19 and provides eight practical approaches for hospitalists to address substance use disorders during the pandemic, including initiating buprenorphine for opioid withdrawal and prescribing it for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

Buprenorphine effectively treats opioid withdrawal, reduces OUD-related mortality, and decreases hospital readmissions related to OUD. To prescribe buprenorphine for OUD in the outpatient setting or on hospital discharge, providers need an X-Waiver. The X-Waiver is a result of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act 2000 (DATA 2000), which was enacted in 2000. It permits physicians to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD treatment after an 8-hour training. In 2016, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act extended buprenorphine prescribing to physician assistants (PAs) and advanced-practice nurses (APNs). However, PAs and APNs are required to complete a 24-hour training to receive the waiver.

On Jan. 14, 2021, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under the Trump administration announced it was removing the X-Waiver training previously required for physicians to prescribe this life-saving medication. However, on Jan. 20, 2021, the Biden administration froze the training requirement removal pending a 60-day review. The excitement about the waiver’s eradication further dampened on Jan. 25, when the plan was halted due to procedural factors coupled with the concern that HHS may not have the authority to void requirements mandated by Congress.

Many of us continue to be hopeful that the X-Waiver will soon be gone. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has committed to working with federal agencies to increase access to buprenorphine. The Biden administration also committed to addressing our country’s addiction crisis, including a plan to “make effective prevention, treatment, and recovery services available to all, including through a $125 billion federal investment.”

Despite the pause on HHS’s recent attempt to “X the X-Waiver,” we now have renewed attention and interest in this critical issue and an opportunity for greater and longer-lasting legislative impact. SHM supports that Congress repeal the legislative requirement for buprenorphine training dictated by DATA 2000 so that it cannot be rolled back by future administrations. To further increase access to buprenorphine treatment, the training requirement should be removed for all providers who care for individuals with OUD.

The X-Waiver has been a barrier to hospitalist adoption of this critical, life-saving medication. HHS’s stance to nix the waiver, though fleeting, should be interpreted as an urgent call to the medical community, including us as hospitalists, to learn about buprenorphine with the many resources available (see table 1). As hospital medicine providers, we can order buprenorphine for patients with OUD during hospitalization. It is discharge prescriptions that have been limited to providers with an X-Waiver.

What can we do now to prepare for the eventual X-Waiver training removal? We can start by educating ourselves with the resources listed in table 1. Those of us who are already buprenorphine champions could lead trainings in our home institutions. In a future without the waiver there will be more flexibility to develop hospitalist-focused buprenorphine trainings, as the previous ones were geared for outpatient providers. Hospitalist organizations could support hospitalist-specific buprenorphine trainings and extend the models to include additional medications for addiction.

There is a large body of evidence regarding buprenorphine’s safety and efficacy in OUD treatment. With a worsening overdose crisis, there have been increasing opioid-related hospitalizations. When new medications for diabetes, hypertension, or DVT treatment become available, as hospitalists we incorporate them into our toolbox. As buprenorphine becomes more accessible, we can be leaders in further adopting it (and other substance use disorder medications while we are at it) as our standard of care for people with OUD.

Dr. Bottner is a physician assistant in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin and director of the hospital’s Buprenorphine Team. Dr. Martin is a board-certified addiction medicine physician and hospitalist at University of California, San Francisco, and director of the Addiction Care Team at San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Bottner and Dr. Martin colead the SHM Substance Use Disorder Special Interest Group.

There are two pandemics permeating the United States: COVID-19 and addiction. To date, more than 468,000 people have died from COVID-19 in the U.S. In the 12-month period ending in May 2020, over 80,000 died from a drug related cause – the highest number ever recorded in a year. Many of these deaths involved opioids.

COVID-19 has worsened outcomes for people with addiction. There is less access to treatment, increased isolation, and worsening psychosocial and economic stressors. These factors may drive new, increased, or more risky substance use and return to use for people in recovery. As hospitalists, we have been responders in both COVID-19 and our country’s worsening overdose and addiction crisis.

In December 2020’s Journal of Hospital Medicine article “Converging Crises: Caring for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder in the time of COVID-19”, Dr. Honora Englander and her coauthors called on hospitalists to actively engage patients with substance use disorders during hospitalization. The article highlights the colliding crises of addiction and COVID-19 and provides eight practical approaches for hospitalists to address substance use disorders during the pandemic, including initiating buprenorphine for opioid withdrawal and prescribing it for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

Buprenorphine effectively treats opioid withdrawal, reduces OUD-related mortality, and decreases hospital readmissions related to OUD. To prescribe buprenorphine for OUD in the outpatient setting or on hospital discharge, providers need an X-Waiver. The X-Waiver is a result of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act 2000 (DATA 2000), which was enacted in 2000. It permits physicians to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD treatment after an 8-hour training. In 2016, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act extended buprenorphine prescribing to physician assistants (PAs) and advanced-practice nurses (APNs). However, PAs and APNs are required to complete a 24-hour training to receive the waiver.

On Jan. 14, 2021, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services under the Trump administration announced it was removing the X-Waiver training previously required for physicians to prescribe this life-saving medication. However, on Jan. 20, 2021, the Biden administration froze the training requirement removal pending a 60-day review. The excitement about the waiver’s eradication further dampened on Jan. 25, when the plan was halted due to procedural factors coupled with the concern that HHS may not have the authority to void requirements mandated by Congress.

Many of us continue to be hopeful that the X-Waiver will soon be gone. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has committed to working with federal agencies to increase access to buprenorphine. The Biden administration also committed to addressing our country’s addiction crisis, including a plan to “make effective prevention, treatment, and recovery services available to all, including through a $125 billion federal investment.”

Despite the pause on HHS’s recent attempt to “X the X-Waiver,” we now have renewed attention and interest in this critical issue and an opportunity for greater and longer-lasting legislative impact. SHM supports that Congress repeal the legislative requirement for buprenorphine training dictated by DATA 2000 so that it cannot be rolled back by future administrations. To further increase access to buprenorphine treatment, the training requirement should be removed for all providers who care for individuals with OUD.

The X-Waiver has been a barrier to hospitalist adoption of this critical, life-saving medication. HHS’s stance to nix the waiver, though fleeting, should be interpreted as an urgent call to the medical community, including us as hospitalists, to learn about buprenorphine with the many resources available (see table 1). As hospital medicine providers, we can order buprenorphine for patients with OUD during hospitalization. It is discharge prescriptions that have been limited to providers with an X-Waiver.

What can we do now to prepare for the eventual X-Waiver training removal? We can start by educating ourselves with the resources listed in table 1. Those of us who are already buprenorphine champions could lead trainings in our home institutions. In a future without the waiver there will be more flexibility to develop hospitalist-focused buprenorphine trainings, as the previous ones were geared for outpatient providers. Hospitalist organizations could support hospitalist-specific buprenorphine trainings and extend the models to include additional medications for addiction.

There is a large body of evidence regarding buprenorphine’s safety and efficacy in OUD treatment. With a worsening overdose crisis, there have been increasing opioid-related hospitalizations. When new medications for diabetes, hypertension, or DVT treatment become available, as hospitalists we incorporate them into our toolbox. As buprenorphine becomes more accessible, we can be leaders in further adopting it (and other substance use disorder medications while we are at it) as our standard of care for people with OUD.

Dr. Bottner is a physician assistant in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin and director of the hospital’s Buprenorphine Team. Dr. Martin is a board-certified addiction medicine physician and hospitalist at University of California, San Francisco, and director of the Addiction Care Team at San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Bottner and Dr. Martin colead the SHM Substance Use Disorder Special Interest Group.

Chronic GVHD therapies offer hope for treating refractory disease

Despite improvements in prevention of graft-versus-host disease, chronic GVHD still occurs in 10%-50% of patients who undergo an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and these patients may require prolonged treatment with multiple lines of therapy, said a hematologist and transplant researcher.

“More effective, less toxic therapies for chronic GVHD are needed,” Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle said at the Transplant & Cellular Therapies Meetings.

Dr. Lee reviewed clinical trials for chronic GVHD at the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Although the incidence of chronic GVHD has gradually declined over the last 40 years and both relapse-free and overall survival following a chronic GVHD diagnosis have improved, “for patients who are diagnosed with chronic GVHD, they still will see many lines of therapy and many years of therapy,” she said.

Among 148 patients with chronic GVHD treated at her center, for example, 66% went on to two lines of therapy, 50% went on to three lines, 37% required four lines of therapy, and 20% needed five lines or more.

Salvage therapies for patients with chronic GVHD have evolved away from immunomodulators and immunosuppressants in the early 1990s, toward monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab in the early 2000s, to interleukin-2 and to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as ruxolitinib (Jakafi) and ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

There are currently 36 agents that are FDA approved for at least one indication and can also be prescribed for the treatment of chronic GVHD, Dr. Lee noted.

Treatment goals

Dr. Lee laid out six goals for treating patients with chronic GVHD. They include:

- Controlling current signs and symptoms, measured by response rates and patient-reported outcomes

- Preventing further tissue and organ damage

- Minimizing toxicity

- Maintaining graft-versus-tumor effect

- Achieving graft tolerance and stopping immunosuppression

- Decreasing nonrelapse mortality and improving survival

Active trials

Dr. Lee identified 33 trials with chronic GVHD as an indication that are currently recruiting, and an additional 13 trials that are active but closed to recruiting. The trials can be generally grouped by mechanism of action, and involve agents targeting T-regulatory cells, B cells and/or B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, monocytes/macrophages, costimulatory blockage, a proteasome inhibition, Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitors, ROCK2 inhibitors, hedgehog pathway inhibition, cellular therapy, and organ-targeted therapy.

Most of the trials have overall response rate as the primary endpoint, and all but five are currently in phase 1 or 2. The currently active phase 3 trials include two with ibrutinib, one with the investigational agent itacitinib, one with ruxolitinib, and one with mesenchymal stem cells.

“I’ll note that, when results are reported, the denominator really matters for the overall response rate, especially if you’re talking about small trials, because if you require the patient to be treated with an agent for a certain period of time, and you take out all the people who didn’t make it to that time point, then your overall response rate looks better,” she said.

BTK inhibitors

The first-in-class Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was the first and thus far only agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration for chronic GVHD. The approval was based on a single-arm, multicenter trial with 42 patients.

The ORR in this trial was 69%, consisting of 31% complete responses and 38% partial responses, with a duration of response longer than 10 months in slightly more than half of all patients. In all, 24% of patients had improvement of symptoms in two consecutive visits, and 29% continued on ibrutinib at the time of the primary analysis in 2017.

Based on these promising results, acalabrutinib, which is more potent and selective for BTK than ibrutinib, with no effect on either platelets or natural killer cells, is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial in 50 patients at a dose of 100 mg orally twice daily.

JAK1/2 inhibition

The JAK1 inhibitor itacitinib failed to meet its primary ORR endpoint in the phase 3 GRAVITAS-301 study, according to a press release, but the manufacturer (Incyte) said that it is continuing its commitment to JAK inhibitors with ruxolitinib, which has shown activity against acute, steroid-refractory GVHD, and is being explored for prevention of chronic GVHD in the randomized, phase 3 REACH3 study.

The trial met its primary endpoint for a higher ORR at week 24 with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy, at 49.7% versus 25.6%, respectively, which translated into an odds ratio for response with the JAK inhibitor of 2.99 (P < .0001).

Selective T-cell expansion

Efavaleukin alfa is an IL-2-mutated protein (mutein), with a mutation in the IL-2RB-binding portion of IL-2 causing increased selectivity for regulatory T-cell expansion. It is bound to an IgG-Fc domain that is itself mutated, with reduced Fc receptor binding and IgG effector function to give it a longer half life. This agent is being studied in a phase 1/2 trial in a subcutaneous formulation delivered every 1 or 2 weeks to 68 patients.

Monocyte/macrophage depletion

Axatilimab is a high-affinity antibody targeting colony stimulating factor–1 receptor (CSF-1R) expressed on monocytes and macrophages. By blocking CSF-1R, it depletes circulation of nonclassical monocytes and prevents the differentiation and survival of M2 macrophages in tissue.

It is currently being investigated 30 patients in a phase 1/2 study in an intravenous formulation delivered over 30 minutes every 2-4 weeks.

Hedgehog pathway inhibition

There is evidence suggesting that hedgehog pathway inhibition can lessen fibrosis. Glasdegib (Daurismo) a potent selective oral inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is approved for use with low-dose cytarabine for patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia aged older than 75 years or have comorbidities precluding intensive chemotherapy.

This agent is associated with drug intolerance because of muscle spasms, dysgeusia, and alopecia, however.

The drug is currently in phase 1/2 at a dose of 50 mg orally per day in 20 patients.

ROCK2 inhibition

Belumosudil (formerly KD025) “appears to rebalance the immune system,” Dr. Lee said. Investigators think that the drug dampens an autoaggressive inflammatory response by selective inhibition of ROCK2.

This drug has been studied in a dose-escalation study and a phase 2 trial, in which 132 participants were randomized to receive belumosudil 200 mg either once or twice daily.

At a median follow-up of 8 months, the ORR with belumosudil 200 mg once and twice daily was 73% and 74%, respectively. Similar results were seen in patients who had previously received either ruxolitinib or ibrutinib. High response rates were seen in patients with severe chronic GVHD, involvement of four or more organs and a refractory response to their last line of therapy.

Hard-to-manage patients

“We’re very hopeful for many of these agents, but we have to acknowledge that there are still many management dilemmas, patients that we just don’t really know what to do with,” Dr. Lee said. “These include patients who have bad sclerosis and fasciitis, nonhealing skin ulcers, bronchiolitis obliterans, serositis that can be very difficult to manage, severe keratoconjunctivitis that can be eyesight threatening, nonhealing mouth ulcers, esophageal structures, and always patients who have frequent infections.

“We are hopeful that some these agents will be useful for our patients who have severe manifestations, but often the number of patients with these manifestations in the trials is too low to say something specific about them,” she added.

‘Exciting time’

“It’s an exciting time because there are a lot of different drugs that are being studied for chronic GVHD,” commented Betty Hamilton, MD, a hematologist/oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic.

“I think that where the field is going in terms of treatment is recognizing that chronic GVHD is a pretty heterogeneous disease, and we have to learn even more about the underlying biologic pathways to be able to determine which class of drugs to use and when,” she said in an interview.

She agreed with Dr. Lee that the goals of treating patients with chronic GVHD include improving symptoms and quality, preventing progression, ideally tapering patients off immunosuppression, and achieving a balance between preventing negative consequences of GVHD while maintain the benefits of a graft-versus-leukemia effect.

“In our center, drug choice is based on physician preference and comfort with how often they’ve used the drug, patients’ comorbidities, toxicities of the drug, and logistical considerations,” Dr. Hamilton said.

Dr. Lee disclosed consulting activities for Pfizer and Kadmon, travel and lodging from Amgen, and research funding from those companies and others. Dr. Hamilton disclosed consulting for Syndax and Incyte.

Despite improvements in prevention of graft-versus-host disease, chronic GVHD still occurs in 10%-50% of patients who undergo an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and these patients may require prolonged treatment with multiple lines of therapy, said a hematologist and transplant researcher.

“More effective, less toxic therapies for chronic GVHD are needed,” Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle said at the Transplant & Cellular Therapies Meetings.

Dr. Lee reviewed clinical trials for chronic GVHD at the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Although the incidence of chronic GVHD has gradually declined over the last 40 years and both relapse-free and overall survival following a chronic GVHD diagnosis have improved, “for patients who are diagnosed with chronic GVHD, they still will see many lines of therapy and many years of therapy,” she said.

Among 148 patients with chronic GVHD treated at her center, for example, 66% went on to two lines of therapy, 50% went on to three lines, 37% required four lines of therapy, and 20% needed five lines or more.

Salvage therapies for patients with chronic GVHD have evolved away from immunomodulators and immunosuppressants in the early 1990s, toward monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab in the early 2000s, to interleukin-2 and to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as ruxolitinib (Jakafi) and ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

There are currently 36 agents that are FDA approved for at least one indication and can also be prescribed for the treatment of chronic GVHD, Dr. Lee noted.

Treatment goals

Dr. Lee laid out six goals for treating patients with chronic GVHD. They include:

- Controlling current signs and symptoms, measured by response rates and patient-reported outcomes

- Preventing further tissue and organ damage

- Minimizing toxicity

- Maintaining graft-versus-tumor effect

- Achieving graft tolerance and stopping immunosuppression

- Decreasing nonrelapse mortality and improving survival

Active trials

Dr. Lee identified 33 trials with chronic GVHD as an indication that are currently recruiting, and an additional 13 trials that are active but closed to recruiting. The trials can be generally grouped by mechanism of action, and involve agents targeting T-regulatory cells, B cells and/or B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, monocytes/macrophages, costimulatory blockage, a proteasome inhibition, Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitors, ROCK2 inhibitors, hedgehog pathway inhibition, cellular therapy, and organ-targeted therapy.

Most of the trials have overall response rate as the primary endpoint, and all but five are currently in phase 1 or 2. The currently active phase 3 trials include two with ibrutinib, one with the investigational agent itacitinib, one with ruxolitinib, and one with mesenchymal stem cells.

“I’ll note that, when results are reported, the denominator really matters for the overall response rate, especially if you’re talking about small trials, because if you require the patient to be treated with an agent for a certain period of time, and you take out all the people who didn’t make it to that time point, then your overall response rate looks better,” she said.

BTK inhibitors

The first-in-class Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was the first and thus far only agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration for chronic GVHD. The approval was based on a single-arm, multicenter trial with 42 patients.

The ORR in this trial was 69%, consisting of 31% complete responses and 38% partial responses, with a duration of response longer than 10 months in slightly more than half of all patients. In all, 24% of patients had improvement of symptoms in two consecutive visits, and 29% continued on ibrutinib at the time of the primary analysis in 2017.

Based on these promising results, acalabrutinib, which is more potent and selective for BTK than ibrutinib, with no effect on either platelets or natural killer cells, is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial in 50 patients at a dose of 100 mg orally twice daily.

JAK1/2 inhibition

The JAK1 inhibitor itacitinib failed to meet its primary ORR endpoint in the phase 3 GRAVITAS-301 study, according to a press release, but the manufacturer (Incyte) said that it is continuing its commitment to JAK inhibitors with ruxolitinib, which has shown activity against acute, steroid-refractory GVHD, and is being explored for prevention of chronic GVHD in the randomized, phase 3 REACH3 study.

The trial met its primary endpoint for a higher ORR at week 24 with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy, at 49.7% versus 25.6%, respectively, which translated into an odds ratio for response with the JAK inhibitor of 2.99 (P < .0001).

Selective T-cell expansion

Efavaleukin alfa is an IL-2-mutated protein (mutein), with a mutation in the IL-2RB-binding portion of IL-2 causing increased selectivity for regulatory T-cell expansion. It is bound to an IgG-Fc domain that is itself mutated, with reduced Fc receptor binding and IgG effector function to give it a longer half life. This agent is being studied in a phase 1/2 trial in a subcutaneous formulation delivered every 1 or 2 weeks to 68 patients.

Monocyte/macrophage depletion

Axatilimab is a high-affinity antibody targeting colony stimulating factor–1 receptor (CSF-1R) expressed on monocytes and macrophages. By blocking CSF-1R, it depletes circulation of nonclassical monocytes and prevents the differentiation and survival of M2 macrophages in tissue.

It is currently being investigated 30 patients in a phase 1/2 study in an intravenous formulation delivered over 30 minutes every 2-4 weeks.

Hedgehog pathway inhibition

There is evidence suggesting that hedgehog pathway inhibition can lessen fibrosis. Glasdegib (Daurismo) a potent selective oral inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is approved for use with low-dose cytarabine for patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia aged older than 75 years or have comorbidities precluding intensive chemotherapy.

This agent is associated with drug intolerance because of muscle spasms, dysgeusia, and alopecia, however.

The drug is currently in phase 1/2 at a dose of 50 mg orally per day in 20 patients.

ROCK2 inhibition

Belumosudil (formerly KD025) “appears to rebalance the immune system,” Dr. Lee said. Investigators think that the drug dampens an autoaggressive inflammatory response by selective inhibition of ROCK2.

This drug has been studied in a dose-escalation study and a phase 2 trial, in which 132 participants were randomized to receive belumosudil 200 mg either once or twice daily.

At a median follow-up of 8 months, the ORR with belumosudil 200 mg once and twice daily was 73% and 74%, respectively. Similar results were seen in patients who had previously received either ruxolitinib or ibrutinib. High response rates were seen in patients with severe chronic GVHD, involvement of four or more organs and a refractory response to their last line of therapy.

Hard-to-manage patients

“We’re very hopeful for many of these agents, but we have to acknowledge that there are still many management dilemmas, patients that we just don’t really know what to do with,” Dr. Lee said. “These include patients who have bad sclerosis and fasciitis, nonhealing skin ulcers, bronchiolitis obliterans, serositis that can be very difficult to manage, severe keratoconjunctivitis that can be eyesight threatening, nonhealing mouth ulcers, esophageal structures, and always patients who have frequent infections.

“We are hopeful that some these agents will be useful for our patients who have severe manifestations, but often the number of patients with these manifestations in the trials is too low to say something specific about them,” she added.

‘Exciting time’

“It’s an exciting time because there are a lot of different drugs that are being studied for chronic GVHD,” commented Betty Hamilton, MD, a hematologist/oncologist at the Cleveland Clinic.

“I think that where the field is going in terms of treatment is recognizing that chronic GVHD is a pretty heterogeneous disease, and we have to learn even more about the underlying biologic pathways to be able to determine which class of drugs to use and when,” she said in an interview.

She agreed with Dr. Lee that the goals of treating patients with chronic GVHD include improving symptoms and quality, preventing progression, ideally tapering patients off immunosuppression, and achieving a balance between preventing negative consequences of GVHD while maintain the benefits of a graft-versus-leukemia effect.

“In our center, drug choice is based on physician preference and comfort with how often they’ve used the drug, patients’ comorbidities, toxicities of the drug, and logistical considerations,” Dr. Hamilton said.

Dr. Lee disclosed consulting activities for Pfizer and Kadmon, travel and lodging from Amgen, and research funding from those companies and others. Dr. Hamilton disclosed consulting for Syndax and Incyte.

Despite improvements in prevention of graft-versus-host disease, chronic GVHD still occurs in 10%-50% of patients who undergo an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and these patients may require prolonged treatment with multiple lines of therapy, said a hematologist and transplant researcher.

“More effective, less toxic therapies for chronic GVHD are needed,” Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle said at the Transplant & Cellular Therapies Meetings.

Dr. Lee reviewed clinical trials for chronic GVHD at the meeting held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Although the incidence of chronic GVHD has gradually declined over the last 40 years and both relapse-free and overall survival following a chronic GVHD diagnosis have improved, “for patients who are diagnosed with chronic GVHD, they still will see many lines of therapy and many years of therapy,” she said.

Among 148 patients with chronic GVHD treated at her center, for example, 66% went on to two lines of therapy, 50% went on to three lines, 37% required four lines of therapy, and 20% needed five lines or more.

Salvage therapies for patients with chronic GVHD have evolved away from immunomodulators and immunosuppressants in the early 1990s, toward monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab in the early 2000s, to interleukin-2 and to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as ruxolitinib (Jakafi) and ibrutinib (Imbruvica).

There are currently 36 agents that are FDA approved for at least one indication and can also be prescribed for the treatment of chronic GVHD, Dr. Lee noted.

Treatment goals

Dr. Lee laid out six goals for treating patients with chronic GVHD. They include:

- Controlling current signs and symptoms, measured by response rates and patient-reported outcomes

- Preventing further tissue and organ damage

- Minimizing toxicity

- Maintaining graft-versus-tumor effect

- Achieving graft tolerance and stopping immunosuppression

- Decreasing nonrelapse mortality and improving survival

Active trials

Dr. Lee identified 33 trials with chronic GVHD as an indication that are currently recruiting, and an additional 13 trials that are active but closed to recruiting. The trials can be generally grouped by mechanism of action, and involve agents targeting T-regulatory cells, B cells and/or B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling, monocytes/macrophages, costimulatory blockage, a proteasome inhibition, Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitors, ROCK2 inhibitors, hedgehog pathway inhibition, cellular therapy, and organ-targeted therapy.

Most of the trials have overall response rate as the primary endpoint, and all but five are currently in phase 1 or 2. The currently active phase 3 trials include two with ibrutinib, one with the investigational agent itacitinib, one with ruxolitinib, and one with mesenchymal stem cells.

“I’ll note that, when results are reported, the denominator really matters for the overall response rate, especially if you’re talking about small trials, because if you require the patient to be treated with an agent for a certain period of time, and you take out all the people who didn’t make it to that time point, then your overall response rate looks better,” she said.

BTK inhibitors

The first-in-class Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was the first and thus far only agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration for chronic GVHD. The approval was based on a single-arm, multicenter trial with 42 patients.

The ORR in this trial was 69%, consisting of 31% complete responses and 38% partial responses, with a duration of response longer than 10 months in slightly more than half of all patients. In all, 24% of patients had improvement of symptoms in two consecutive visits, and 29% continued on ibrutinib at the time of the primary analysis in 2017.

Based on these promising results, acalabrutinib, which is more potent and selective for BTK than ibrutinib, with no effect on either platelets or natural killer cells, is currently under investigation in a phase 2 trial in 50 patients at a dose of 100 mg orally twice daily.

JAK1/2 inhibition

The JAK1 inhibitor itacitinib failed to meet its primary ORR endpoint in the phase 3 GRAVITAS-301 study, according to a press release, but the manufacturer (Incyte) said that it is continuing its commitment to JAK inhibitors with ruxolitinib, which has shown activity against acute, steroid-refractory GVHD, and is being explored for prevention of chronic GVHD in the randomized, phase 3 REACH3 study.

The trial met its primary endpoint for a higher ORR at week 24 with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy, at 49.7% versus 25.6%, respectively, which translated into an odds ratio for response with the JAK inhibitor of 2.99 (P < .0001).

Selective T-cell expansion

Efavaleukin alfa is an IL-2-mutated protein (mutein), with a mutation in the IL-2RB-binding portion of IL-2 causing increased selectivity for regulatory T-cell expansion. It is bound to an IgG-Fc domain that is itself mutated, with reduced Fc receptor binding and IgG effector function to give it a longer half life. This agent is being studied in a phase 1/2 trial in a subcutaneous formulation delivered every 1 or 2 weeks to 68 patients.

Monocyte/macrophage depletion

Axatilimab is a high-affinity antibody targeting colony stimulating factor–1 receptor (CSF-1R) expressed on monocytes and macrophages. By blocking CSF-1R, it depletes circulation of nonclassical monocytes and prevents the differentiation and survival of M2 macrophages in tissue.

It is currently being investigated 30 patients in a phase 1/2 study in an intravenous formulation delivered over 30 minutes every 2-4 weeks.

Hedgehog pathway inhibition

There is evidence suggesting that hedgehog pathway inhibition can lessen fibrosis. Glasdegib (Daurismo) a potent selective oral inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is approved for use with low-dose cytarabine for patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia aged older than 75 years or have comorbidities precluding intensive chemotherapy.

This agent is associated with drug intolerance because of muscle spasms, dysgeusia, and alopecia, however.

The drug is currently in phase 1/2 at a dose of 50 mg orally per day in 20 patients.

ROCK2 inhibition

Belumosudil (formerly KD025) “appears to rebalance the immune system,” Dr. Lee said. Investigators think that the drug dampens an autoaggressive inflammatory response by selective inhibition of ROCK2.

This drug has been studied in a dose-escalation study and a phase 2 trial, in which 132 participants were randomized to receive belumosudil 200 mg either once or twice daily.

At a median follow-up of 8 months, the ORR with belumosudil 200 mg once and twice daily was 73% and 74%, respectively. Similar results were seen in patients who had previously received either ruxolitinib or ibrutinib. High response rates were seen in patients with severe chronic GVHD, involvement of four or more organs and a refractory response to their last line of therapy.

Hard-to-manage patients