User login

Telangiectatic Patch on the Forehead

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

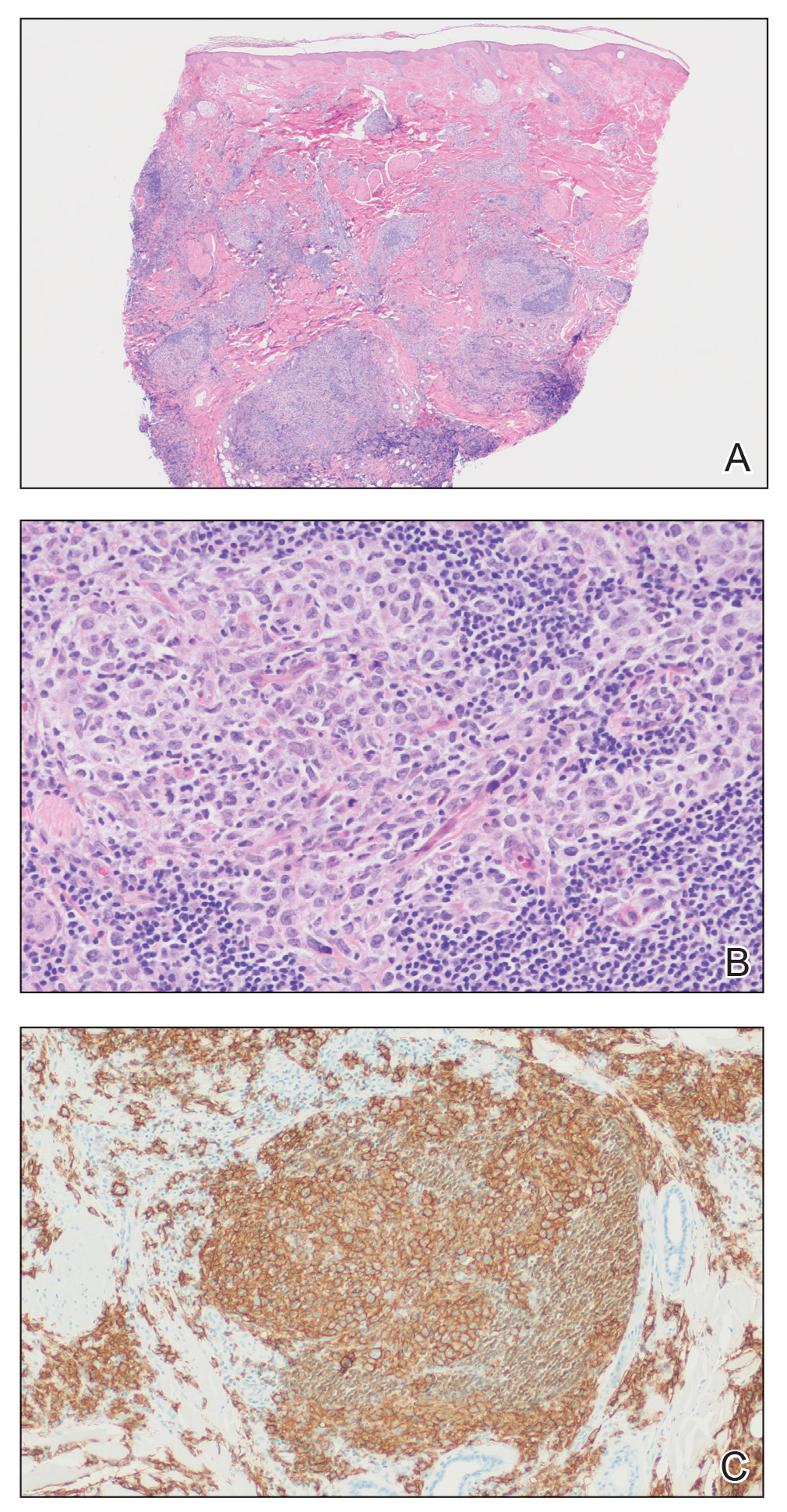

Histopathology was suggestive of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Figure). Further immunohistochemical studies including Bcl-6 positivity and Bcl-2 negativity in the large atypical cells supported a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). The designation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma includes several different types of lymphoma, including marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and intravascular lymphoma. To be considered a primary cutaneous lymphoma, there must be evidence of the lymphoma in the skin without concomitant evidence of systemic involvement, as determined through a full staging workup. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that most commonly presents as solitary or grouped, pink to plum-colored papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors on the scalp, forehead, or back.1 The lesions often are biopsied as suspected basal cell carcinomas or Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs). Lesions on the face or scalp may easily evade diagnosis, as they initially may mimic rosacea or insect bites. Less common presentations include infiltrative lesions that cause rhinophymatous changes or scarring alopecia. Multifocal or disseminated lesions rarely can be observed. This case presentation is unique in its patchy appearance that clinically resembled angiosarcoma.2 When identified and treated, the disease-specific 5-year survival rate for PCFCL is greater than 95%.3

Merkel cell carcinoma was first described in 1972 and has been diagnosed with increasing frequency each year.4 It generally presents as an erythematous or violaceous, tender, indurated nodule on sun-exposed skin of the head or neck in elderly White men. However, other presentations have been reported, including papules, plaques, cystlike structures, pruritic tumors, pedunculated lesions, subcutaneous masses, and telangiectatic papules.5 Histopathologically, MCC is characterized by dermal nests and sheets of basaloid cells with finely granular salt and pepper-like chromatin. The histologic features can resemble other small blue cell tumors; therefore, the differential diagnosis can be broad.5 Immunohistochemistry that can confirm the diagnosis of MCC generally will be positive for cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers but negative for cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with a high risk for local recurrence and distant metastasis that carries a generally poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of metastatic disease at presentation.5,6

Rosacea can appear as telangiectatic patches, though generally not as one discrete patch limited to the forehead, as in our patient. Histologic features vary based on the age of the lesion and clinical variant. In early lesions there is a mild perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the dermis, while older lesions can have a mixed infiltrate crowded around vessels and adnexal structures. Granulomas often are seen near hair follicles and interspersed throughout the dermis with ectatic vessels and dermal edema.7

Angiosarcoma is divided into 3 clinicopathological subtypes: idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck, angiosarcoma in the setting of lymphedema, and postirradiation angiosarcoma.7 Idiopathic angiosarcoma most closely mimics PCFCL, as it can present as single or multifocal nodules, plaques, or patches. Histologically, the 3 groups appear similar with poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, dermal tumors. The neoplastic endothelial cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei that protrude into vascular lumens. The prognosis for idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 34%, which often is due to delayed diagnosis.7

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are chronic skin disorders characterized by purpura due to extravasation of blood from capillaries; the resulting hemosiderin deposition leads to pigmentation.7 There are various forms of PPD, which are classified into groups based on clinical appearance including Schamberg disease, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and others including eczematid and itching variants, which some consider to be distinct entities. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi is the specific PPD that should be included in the clinical differential for PCFCL because it presents as annular patches with telangiectasias. Histologically, PPDs are characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis with extravasated red blood cells and the presence of hemosiderin mostly within macrophages and a lack of true vasculitis. Clonality of the T cells has been shown, and there is some evidence that PPD may overlap with mycosis fungoides. However, this overlap mainly has been seen in patients with widespread lesions and would not apply to this case. In general, patients with PPD can be reassured of the benign process. In cases of widespread PPD, patients should be followed clinically to assess for progression to mycosis fungoides, though the likelihood is low.7

Our patient underwent a full staging workup, which confirmed the diagnosis of PCFCL. He was treated with radiation to the forehead that resulted in clearance of the lesion. Approximately 2 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was alive and well with no evidence of recurrence of PCFCL.

In conclusion, it is imperative to identify unusual, macular, vascular-appearing patches, especially on the head and neck in older individuals. Because the clinical presentations of PCFCL, angiosarcoma, rosacea, MCC, and PPD can overlap with one another as well as with other entities, it is necessary to have a high level of suspicion and low threshold to biopsy these types of lesions, as outcomes can be drastically different.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Atypical clinical presentation of primary and secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) on the head characterized by macular lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1000-1006.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Conic RRZ, Ko J, Saridakis S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity and association with overall survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:364-372

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:445-454.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology was suggestive of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Figure). Further immunohistochemical studies including Bcl-6 positivity and Bcl-2 negativity in the large atypical cells supported a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). The designation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma includes several different types of lymphoma, including marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and intravascular lymphoma. To be considered a primary cutaneous lymphoma, there must be evidence of the lymphoma in the skin without concomitant evidence of systemic involvement, as determined through a full staging workup. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that most commonly presents as solitary or grouped, pink to plum-colored papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors on the scalp, forehead, or back.1 The lesions often are biopsied as suspected basal cell carcinomas or Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs). Lesions on the face or scalp may easily evade diagnosis, as they initially may mimic rosacea or insect bites. Less common presentations include infiltrative lesions that cause rhinophymatous changes or scarring alopecia. Multifocal or disseminated lesions rarely can be observed. This case presentation is unique in its patchy appearance that clinically resembled angiosarcoma.2 When identified and treated, the disease-specific 5-year survival rate for PCFCL is greater than 95%.3

Merkel cell carcinoma was first described in 1972 and has been diagnosed with increasing frequency each year.4 It generally presents as an erythematous or violaceous, tender, indurated nodule on sun-exposed skin of the head or neck in elderly White men. However, other presentations have been reported, including papules, plaques, cystlike structures, pruritic tumors, pedunculated lesions, subcutaneous masses, and telangiectatic papules.5 Histopathologically, MCC is characterized by dermal nests and sheets of basaloid cells with finely granular salt and pepper-like chromatin. The histologic features can resemble other small blue cell tumors; therefore, the differential diagnosis can be broad.5 Immunohistochemistry that can confirm the diagnosis of MCC generally will be positive for cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers but negative for cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with a high risk for local recurrence and distant metastasis that carries a generally poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of metastatic disease at presentation.5,6

Rosacea can appear as telangiectatic patches, though generally not as one discrete patch limited to the forehead, as in our patient. Histologic features vary based on the age of the lesion and clinical variant. In early lesions there is a mild perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the dermis, while older lesions can have a mixed infiltrate crowded around vessels and adnexal structures. Granulomas often are seen near hair follicles and interspersed throughout the dermis with ectatic vessels and dermal edema.7

Angiosarcoma is divided into 3 clinicopathological subtypes: idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck, angiosarcoma in the setting of lymphedema, and postirradiation angiosarcoma.7 Idiopathic angiosarcoma most closely mimics PCFCL, as it can present as single or multifocal nodules, plaques, or patches. Histologically, the 3 groups appear similar with poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, dermal tumors. The neoplastic endothelial cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei that protrude into vascular lumens. The prognosis for idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 34%, which often is due to delayed diagnosis.7

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are chronic skin disorders characterized by purpura due to extravasation of blood from capillaries; the resulting hemosiderin deposition leads to pigmentation.7 There are various forms of PPD, which are classified into groups based on clinical appearance including Schamberg disease, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and others including eczematid and itching variants, which some consider to be distinct entities. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi is the specific PPD that should be included in the clinical differential for PCFCL because it presents as annular patches with telangiectasias. Histologically, PPDs are characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis with extravasated red blood cells and the presence of hemosiderin mostly within macrophages and a lack of true vasculitis. Clonality of the T cells has been shown, and there is some evidence that PPD may overlap with mycosis fungoides. However, this overlap mainly has been seen in patients with widespread lesions and would not apply to this case. In general, patients with PPD can be reassured of the benign process. In cases of widespread PPD, patients should be followed clinically to assess for progression to mycosis fungoides, though the likelihood is low.7

Our patient underwent a full staging workup, which confirmed the diagnosis of PCFCL. He was treated with radiation to the forehead that resulted in clearance of the lesion. Approximately 2 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was alive and well with no evidence of recurrence of PCFCL.

In conclusion, it is imperative to identify unusual, macular, vascular-appearing patches, especially on the head and neck in older individuals. Because the clinical presentations of PCFCL, angiosarcoma, rosacea, MCC, and PPD can overlap with one another as well as with other entities, it is necessary to have a high level of suspicion and low threshold to biopsy these types of lesions, as outcomes can be drastically different.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology was suggestive of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Figure). Further immunohistochemical studies including Bcl-6 positivity and Bcl-2 negativity in the large atypical cells supported a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). The designation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma includes several different types of lymphoma, including marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and intravascular lymphoma. To be considered a primary cutaneous lymphoma, there must be evidence of the lymphoma in the skin without concomitant evidence of systemic involvement, as determined through a full staging workup. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that most commonly presents as solitary or grouped, pink to plum-colored papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors on the scalp, forehead, or back.1 The lesions often are biopsied as suspected basal cell carcinomas or Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs). Lesions on the face or scalp may easily evade diagnosis, as they initially may mimic rosacea or insect bites. Less common presentations include infiltrative lesions that cause rhinophymatous changes or scarring alopecia. Multifocal or disseminated lesions rarely can be observed. This case presentation is unique in its patchy appearance that clinically resembled angiosarcoma.2 When identified and treated, the disease-specific 5-year survival rate for PCFCL is greater than 95%.3

Merkel cell carcinoma was first described in 1972 and has been diagnosed with increasing frequency each year.4 It generally presents as an erythematous or violaceous, tender, indurated nodule on sun-exposed skin of the head or neck in elderly White men. However, other presentations have been reported, including papules, plaques, cystlike structures, pruritic tumors, pedunculated lesions, subcutaneous masses, and telangiectatic papules.5 Histopathologically, MCC is characterized by dermal nests and sheets of basaloid cells with finely granular salt and pepper-like chromatin. The histologic features can resemble other small blue cell tumors; therefore, the differential diagnosis can be broad.5 Immunohistochemistry that can confirm the diagnosis of MCC generally will be positive for cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers but negative for cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with a high risk for local recurrence and distant metastasis that carries a generally poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of metastatic disease at presentation.5,6

Rosacea can appear as telangiectatic patches, though generally not as one discrete patch limited to the forehead, as in our patient. Histologic features vary based on the age of the lesion and clinical variant. In early lesions there is a mild perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the dermis, while older lesions can have a mixed infiltrate crowded around vessels and adnexal structures. Granulomas often are seen near hair follicles and interspersed throughout the dermis with ectatic vessels and dermal edema.7

Angiosarcoma is divided into 3 clinicopathological subtypes: idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck, angiosarcoma in the setting of lymphedema, and postirradiation angiosarcoma.7 Idiopathic angiosarcoma most closely mimics PCFCL, as it can present as single or multifocal nodules, plaques, or patches. Histologically, the 3 groups appear similar with poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, dermal tumors. The neoplastic endothelial cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei that protrude into vascular lumens. The prognosis for idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 34%, which often is due to delayed diagnosis.7

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are chronic skin disorders characterized by purpura due to extravasation of blood from capillaries; the resulting hemosiderin deposition leads to pigmentation.7 There are various forms of PPD, which are classified into groups based on clinical appearance including Schamberg disease, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and others including eczematid and itching variants, which some consider to be distinct entities. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi is the specific PPD that should be included in the clinical differential for PCFCL because it presents as annular patches with telangiectasias. Histologically, PPDs are characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis with extravasated red blood cells and the presence of hemosiderin mostly within macrophages and a lack of true vasculitis. Clonality of the T cells has been shown, and there is some evidence that PPD may overlap with mycosis fungoides. However, this overlap mainly has been seen in patients with widespread lesions and would not apply to this case. In general, patients with PPD can be reassured of the benign process. In cases of widespread PPD, patients should be followed clinically to assess for progression to mycosis fungoides, though the likelihood is low.7

Our patient underwent a full staging workup, which confirmed the diagnosis of PCFCL. He was treated with radiation to the forehead that resulted in clearance of the lesion. Approximately 2 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was alive and well with no evidence of recurrence of PCFCL.

In conclusion, it is imperative to identify unusual, macular, vascular-appearing patches, especially on the head and neck in older individuals. Because the clinical presentations of PCFCL, angiosarcoma, rosacea, MCC, and PPD can overlap with one another as well as with other entities, it is necessary to have a high level of suspicion and low threshold to biopsy these types of lesions, as outcomes can be drastically different.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Atypical clinical presentation of primary and secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) on the head characterized by macular lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1000-1006.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Conic RRZ, Ko J, Saridakis S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity and association with overall survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:364-372

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:445-454.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Atypical clinical presentation of primary and secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) on the head characterized by macular lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1000-1006.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Conic RRZ, Ko J, Saridakis S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity and association with overall survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:364-372

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:445-454.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

FDA gives guidance on allergy, pregnancy concerns for Pfizer COVID vaccine

stating that it is safe for people with any history of allergies, but not for those who might have a known history of severe allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine.

The warning is included in the FDA’s information sheet for health care providers, but questions are arising as to whether the vaccine – which was authorized for emergency use by the FDA on Friday – should not be given to anyone with a history of allergies.

Sara Oliver, MD, an epidemic intelligence service officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported at a Dec. 11 meeting of the agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that two U.K. health care workers with a history of significant allergic reactions had a reaction to the Pfizer vaccine. A third health care worker with no history of allergies developed tachycardia, Dr. Oliver said.

“I want to reassure the public that although there were these few reactions in Great Britain, these were not seen in the larger clinical trial datasets,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA, during a press briefing on Dec. 12.

The Pfizer vaccine “is one that we’re comfortable giving to patients who have had other allergic reactions besides those other than severe allergic reactions to a vaccine or one of its components,” he said.

Dr. Marks suggested that individuals let their physicians know about any history of allergic reactions. He also noted that the federal government will be supplying vaccine administration sites, at least initially, with epinephrine, diphenhydramine, hydrocortisone, and other medications needed to manage allergic reactions.

The FDA is going to monitor side effects such as allergic reactions very closely, “but I think we still need to learn more and that’s why we’re going to be taking precautions. We may have to modify things as we move forward,” said Dr. Marks.

Dr. Oliver said that on Dec. 12 the CDC convened an external panel with experience in vaccine safety, immunology, and allergies “to collate expert knowledge regarding possible cases,” and that the FDA is getting more data from U.K. regulatory authorities.

Pregnancy concerns

Agency officials had little to say, however, about the safety or efficacy of the vaccine for pregnant or breastfeeding women.

The FDA’s information to health care professionals noted that “available data on Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine administered to pregnant women are insufficient to inform vaccine-associated risks in pregnancy.”

Additionally, the agency stated, “data are not available to assess the effects of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine on the breastfed infant or on milk production/excretion.”

Dr. Marks said that, for pregnant women and people who are immunocompromised, “it will be something that providers will need to consider on an individual basis.” He suggested that individuals consult with physicians to weigh the potential benefits and potential risks.

“Certainly, COVID-19 in a pregnant woman is not a good thing,” Dr. Marks said.

An individual might decide to go ahead with vaccination. “But that’s not something we’re recommending, that’s something we’re leaving up to the individual,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

stating that it is safe for people with any history of allergies, but not for those who might have a known history of severe allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine.

The warning is included in the FDA’s information sheet for health care providers, but questions are arising as to whether the vaccine – which was authorized for emergency use by the FDA on Friday – should not be given to anyone with a history of allergies.

Sara Oliver, MD, an epidemic intelligence service officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported at a Dec. 11 meeting of the agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that two U.K. health care workers with a history of significant allergic reactions had a reaction to the Pfizer vaccine. A third health care worker with no history of allergies developed tachycardia, Dr. Oliver said.

“I want to reassure the public that although there were these few reactions in Great Britain, these were not seen in the larger clinical trial datasets,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA, during a press briefing on Dec. 12.

The Pfizer vaccine “is one that we’re comfortable giving to patients who have had other allergic reactions besides those other than severe allergic reactions to a vaccine or one of its components,” he said.

Dr. Marks suggested that individuals let their physicians know about any history of allergic reactions. He also noted that the federal government will be supplying vaccine administration sites, at least initially, with epinephrine, diphenhydramine, hydrocortisone, and other medications needed to manage allergic reactions.

The FDA is going to monitor side effects such as allergic reactions very closely, “but I think we still need to learn more and that’s why we’re going to be taking precautions. We may have to modify things as we move forward,” said Dr. Marks.

Dr. Oliver said that on Dec. 12 the CDC convened an external panel with experience in vaccine safety, immunology, and allergies “to collate expert knowledge regarding possible cases,” and that the FDA is getting more data from U.K. regulatory authorities.

Pregnancy concerns

Agency officials had little to say, however, about the safety or efficacy of the vaccine for pregnant or breastfeeding women.

The FDA’s information to health care professionals noted that “available data on Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine administered to pregnant women are insufficient to inform vaccine-associated risks in pregnancy.”

Additionally, the agency stated, “data are not available to assess the effects of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine on the breastfed infant or on milk production/excretion.”

Dr. Marks said that, for pregnant women and people who are immunocompromised, “it will be something that providers will need to consider on an individual basis.” He suggested that individuals consult with physicians to weigh the potential benefits and potential risks.

“Certainly, COVID-19 in a pregnant woman is not a good thing,” Dr. Marks said.

An individual might decide to go ahead with vaccination. “But that’s not something we’re recommending, that’s something we’re leaving up to the individual,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

stating that it is safe for people with any history of allergies, but not for those who might have a known history of severe allergic reaction to any component of the vaccine.

The warning is included in the FDA’s information sheet for health care providers, but questions are arising as to whether the vaccine – which was authorized for emergency use by the FDA on Friday – should not be given to anyone with a history of allergies.

Sara Oliver, MD, an epidemic intelligence service officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported at a Dec. 11 meeting of the agency’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices that two U.K. health care workers with a history of significant allergic reactions had a reaction to the Pfizer vaccine. A third health care worker with no history of allergies developed tachycardia, Dr. Oliver said.

“I want to reassure the public that although there were these few reactions in Great Britain, these were not seen in the larger clinical trial datasets,” said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA, during a press briefing on Dec. 12.

The Pfizer vaccine “is one that we’re comfortable giving to patients who have had other allergic reactions besides those other than severe allergic reactions to a vaccine or one of its components,” he said.

Dr. Marks suggested that individuals let their physicians know about any history of allergic reactions. He also noted that the federal government will be supplying vaccine administration sites, at least initially, with epinephrine, diphenhydramine, hydrocortisone, and other medications needed to manage allergic reactions.

The FDA is going to monitor side effects such as allergic reactions very closely, “but I think we still need to learn more and that’s why we’re going to be taking precautions. We may have to modify things as we move forward,” said Dr. Marks.

Dr. Oliver said that on Dec. 12 the CDC convened an external panel with experience in vaccine safety, immunology, and allergies “to collate expert knowledge regarding possible cases,” and that the FDA is getting more data from U.K. regulatory authorities.

Pregnancy concerns

Agency officials had little to say, however, about the safety or efficacy of the vaccine for pregnant or breastfeeding women.

The FDA’s information to health care professionals noted that “available data on Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine administered to pregnant women are insufficient to inform vaccine-associated risks in pregnancy.”

Additionally, the agency stated, “data are not available to assess the effects of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine on the breastfed infant or on milk production/excretion.”

Dr. Marks said that, for pregnant women and people who are immunocompromised, “it will be something that providers will need to consider on an individual basis.” He suggested that individuals consult with physicians to weigh the potential benefits and potential risks.

“Certainly, COVID-19 in a pregnant woman is not a good thing,” Dr. Marks said.

An individual might decide to go ahead with vaccination. “But that’s not something we’re recommending, that’s something we’re leaving up to the individual,” he said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Understanding messenger RNA and other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

In mid-November, Pfizer/BioNTech were the first with surprising positive protection interim data for their coronavirus vaccine, BNT162b2. A week later, Moderna released interim efficacy results showing its coronavirus vaccine, mRNA-1273, also protected patients from developing SARS-CoV-2 infections. Both studies included mostly healthy adults. A diverse ethnic and racial vaccinated population was included. A reasonable number of persons aged over 65 years, and persons with stable compromising medical conditions were included. Adolescents aged 16 years and over were included. Younger adolescents have been vaccinated or such studies are in the planning or early implementation stage as 2020 came to a close.

These are new and revolutionary vaccines, although the ability to inject mRNA into animals dates back to 1990, technological advances today make it a reality.1 Traditional vaccines typically involve injection with antigens such as purified proteins or polysaccharides or inactivated/attenuated viruses. In the case of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines, the mRNA provides the genetic information to synthesize the spike protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and infect human cells. Each type of vaccine is packaged in proprietary lipid nanoparticles to protect the mRNA from rapid degradation, and the nanoparticles serve as an adjuvant to attract immune cells to the site of injection. (The properties of the respective lipid nanoparticle packaging may be the factor that impacts storage requirements discussed below.) When injected into muscle (myocyte), the lipid nanoparticles containing the mRNA inside are taken into muscle cells, where the cytoplasmic ribosomes detect and decode the mRNA resulting in the production of the spike protein antigen. It should be noted that the mRNA does not enter the nucleus, where the genetic information (DNA) of a cell is located, and can’t be reproduced or integrated into the DNA. The antigen is exported to the myocyte cell surface where the immune system’s antigen presenting cells detect the protein, ingest it, and take it to regional lymph nodes where interactions with T cells and B cells results in antibodies, T cell–mediated immunity, and generation of immune memory T cells and B cells. A particular subset of T cells – cytotoxic or killer T cells – destroy cells that have been infected by a pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine from Pfizer was reported to induce powerful cytotoxic T-cell responses. Results for Moderna’s vaccine had not been reported at the time this column was prepared, but I anticipate the same positive results.

The revolutionary aspect of mRNA vaccines is the speed at which they can be designed and produced. This is why they lead the pack among the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates and why the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided financial, technical, and/or clinical support. Indeed, once the amino acid sequence of a protein can be determined (a relatively easy task these days) it’s straightforward to synthesize mRNA in the lab – and it can be done incredibly fast. It is reported that the mRNA code for the vaccine by Moderna was made in 2 days and production development was completed in about 2 months.2

A 2007 World Health Organization report noted that infectious diseases are emerging at “the historically unprecedented rate of one per year.”3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Zika, Ebola, and avian and swine flu are recent examples. For most vaccines against emerging diseases, the challenge is about speed: developing and manufacturing a vaccine and getting it to persons who need it as quickly as possible. The current seasonal flu vaccine takes about 6 months to develop; it takes years for most of the traditional vaccines. That’s why once the infrastructure is in place, mRNA vaccines may prove to offer a big advantage as vaccines against emerging pathogens.

Early efficacy results have been surprising

Both vaccines were reported to produce about 95% efficacy in the final analysis. That was unexpectedly high because most vaccines for respiratory illness achieve efficacy of 60%-80%, e.g., flu vaccines. However, the efficacy rate may drop as time goes by because stimulation of short-term immunity would be in the earliest reported results.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 cases is an important aspect of a coronavirus vaccine, but preventing severe illness is especially important considering that severe cases can result in prolonged intubation/artificial ventilation, prolonged disability and death. Pfizer/BioNTech had not released any data on the breakdown of severe cases as this column was finalized. In Moderna’s clinical trial, a secondary endpoint analyzed severe cases of COVID-19 and included 30 severe cases (as defined in the study protocol) in this analysis. All 30 cases occurred in the placebo group and none in the mRNA-1273–vaccinated group. In the Pfizer/BioNTech trial there were too few cases of severe illness to calculate efficacy.

Duration of immunity and need to revaccinate after initial primary vaccination are unknowns. Study of induction of B- and T-cell memory and levels of long-term protection have not been reported thus far.

Could mRNA COVID-19 vaccines be dangerous in the long term?

These will be the first-ever mRNA vaccines brought to market for humans. In order to receive Food and Drug Administration approval, the companies had to prove there were no immediate or short-term negative adverse effects from the vaccines. The companies reported that their independent data-monitoring committees hadn’t “reported any serious safety concerns.” However, fairly significant local reactions at the site of injection, fever, malaise, and fatigue occur with modest frequency following vaccinations with these products, reportedly in 10%-15% of vaccinees. Overall, the immediate reaction profile appears to be more severe than what occurs following seasonal influenza vaccination. When mass inoculations with these completely new and revolutionary vaccines begins, we will know virtually nothing about their long-term side effects. The possibility of systemic inflammatory responses that could lead to autoimmune conditions, persistence of the induced immunogen expression, development of autoreactive antibodies, and toxic effects of delivery components have been raised as theoretical concerns.4-6 None of these theoretical risks have been observed to date and postmarketing phase 4 safety monitoring studies are in place from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the companies that produce the vaccines. This is a risk public health authorities are willing to take because the risk to benefit calculation strongly favors taking theoretical risks, compared with clear benefits in preventing severe illnesses and death.

What about availability?

Pfizer/BioNTech expects to be able to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Moderna expects to produce 20 million doses by the end of 2020, and 500 million to 1 billion doses in 2021. Storage requirements are inherent to the composition of the vaccines with their differing lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2 has to be stored and transported at –80° C, which requires specialized freezers, which most doctors’ offices and pharmacies are unlikely to have on site, or dry ice containers. Once the vaccine is thawed, it can only remain in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Moderna’s mRNA-1273 will be much easier to distribute. The vaccine is stable in a standard freezer at –20° C for up to 6 months, in a refrigerator for up to 30 days within that 6-month shelf life, and at room temperature for up to 12 hours.

Timelines and testing other vaccines

Strong efficacy data from the two leading SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and emergency-use authorization Food and Drug Administration approval suggest the window for testing additional vaccine candidates in the United States could soon start to close. Of the more than 200 vaccines in development for SARS-CoV-2, at least 7 have a chance of gathering pivotal data before the front-runners become broadly available.

Testing diverse vaccine candidates, based on different technologies, is important for ensuring sufficient supply and could lead to products with tolerability and safety profiles that make them better suited, or more attractive, to subsets of the population. Different vaccine antigens and technologies also may yield different durations of protection, a question that will not be answered until long after the first products are on the market.

AstraZeneca enrolled about 23,000 subjects into its two phase 3 trials of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19): a 40,000-subject U.S. trial and a 10,000-subject study in Brazil. AstraZeneca’s AZD1222, developed with the University of Oxford (England), uses a replication defective simian adenovirus vector called ChAdOx1.AZD1222 which encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. After injection, the viral vector delivers recombinant DNA that is decoded to mRNA, followed by mRNA decoding to become a protein. A serendipitous manufacturing error for the first 3,000 doses resulted in a half dose for those subjects before the error was discovered. Full doses were given to those subjects on second injections and those subjects showed 90% efficacy. Subjects who received 2 full doses showed 62% efficacy. A vaccine cannot be licensed based on 3,000 subjects so AstraZeneca has started a new phase 3 trial involving many more subjects to receive the combination lower dose followed by the full dose.

Johnson and Johnson (J&J) started its phase 3 trial evaluating a single dose of JNJ-78436735 in September. Phase 3 data may be reported by the end of2020. In November, J&J announced it was starting a second phase 3 trial to test two doses of the candidate. J&J’s JNJ-78436735 encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in an adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector, which is one of the two adenovirus vectors used in Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine reported to have 90% efficacy at an early interim analysis.

Sanofi and Novavax are both developing protein-based vaccines, a proven modality. Sanofi, in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline started a phase 1/2 clinical trial in the Fall 2020 with plans to commence a phase 3 trial in late December. Sanofi developed the protein ingredients and GlaxoSmithKline added one of their novel adjuvants. Novavax expects data from a U.K. phase 3 trial of NVX-CoV2373 in early 2021 and began a U.S. phase 3 study in late November. NVX-CoV2373 was created using Novavax’ recombinant nanoparticle technology to generate antigen derived from the coronavirus spike protein and contains Novavax’s patented saponin-based Matrix-M adjuvant.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals was gearing up to start a U.S. phase 2/3 trial of DNA vaccine INO-4800 by the end of 2020.

After Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, CureVac has the next most advanced mRNA vaccine. It was planned that a phase 2b/3 trial of CVnCoV would be conducted in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Sanofi is also developing a mRNA vaccine as a second product in addition to its protein vaccine.

Vaxxinity planned to begin phase 3 testing of UB-612, a multitope peptide–based vaccine, in Brazil by the end of 2020.

However, emergency-use authorizations for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines could hinder trial recruitment in at least two ways. Given the gravity of the pandemic, some stakeholders believe it would be ethical to unblind ongoing trials to give subjects the opportunity to switch to a vaccine proven to be effective. Even if unblinding doesn’t occur, as the two authorized vaccines start to become widely available, volunteering for clinical trials may become less attractive.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Pichichero at [email protected].

References

1. Wolff JA et al. Science. 1990 Mar 23. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918.

2. Jackson LA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483.

3. Prentice T and Reinders LT. The world health report 2007. (Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007).

4. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

5. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

6. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

In mid-November, Pfizer/BioNTech were the first with surprising positive protection interim data for their coronavirus vaccine, BNT162b2. A week later, Moderna released interim efficacy results showing its coronavirus vaccine, mRNA-1273, also protected patients from developing SARS-CoV-2 infections. Both studies included mostly healthy adults. A diverse ethnic and racial vaccinated population was included. A reasonable number of persons aged over 65 years, and persons with stable compromising medical conditions were included. Adolescents aged 16 years and over were included. Younger adolescents have been vaccinated or such studies are in the planning or early implementation stage as 2020 came to a close.

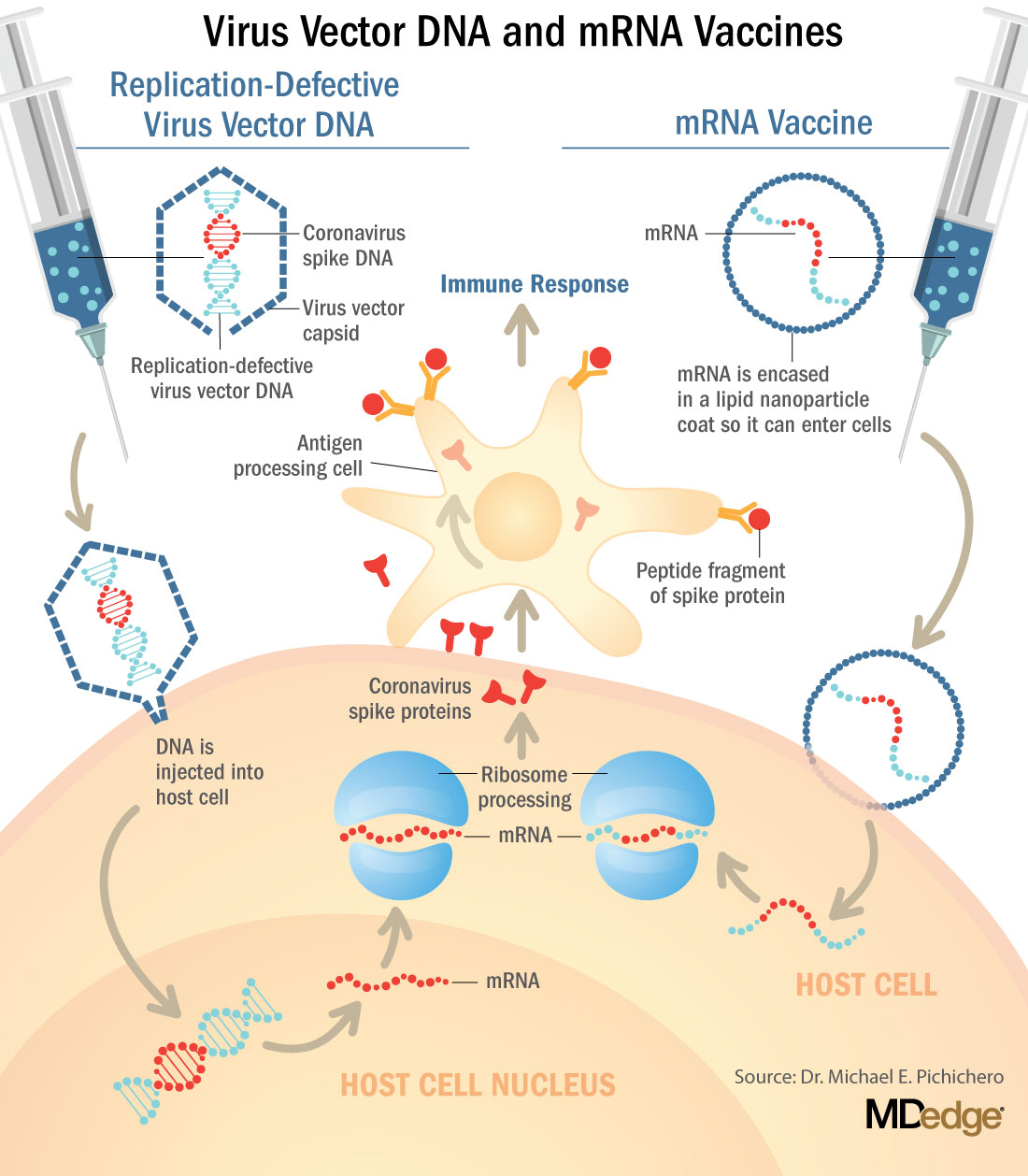

These are new and revolutionary vaccines, although the ability to inject mRNA into animals dates back to 1990, technological advances today make it a reality.1 Traditional vaccines typically involve injection with antigens such as purified proteins or polysaccharides or inactivated/attenuated viruses. In the case of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines, the mRNA provides the genetic information to synthesize the spike protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and infect human cells. Each type of vaccine is packaged in proprietary lipid nanoparticles to protect the mRNA from rapid degradation, and the nanoparticles serve as an adjuvant to attract immune cells to the site of injection. (The properties of the respective lipid nanoparticle packaging may be the factor that impacts storage requirements discussed below.) When injected into muscle (myocyte), the lipid nanoparticles containing the mRNA inside are taken into muscle cells, where the cytoplasmic ribosomes detect and decode the mRNA resulting in the production of the spike protein antigen. It should be noted that the mRNA does not enter the nucleus, where the genetic information (DNA) of a cell is located, and can’t be reproduced or integrated into the DNA. The antigen is exported to the myocyte cell surface where the immune system’s antigen presenting cells detect the protein, ingest it, and take it to regional lymph nodes where interactions with T cells and B cells results in antibodies, T cell–mediated immunity, and generation of immune memory T cells and B cells. A particular subset of T cells – cytotoxic or killer T cells – destroy cells that have been infected by a pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine from Pfizer was reported to induce powerful cytotoxic T-cell responses. Results for Moderna’s vaccine had not been reported at the time this column was prepared, but I anticipate the same positive results.

The revolutionary aspect of mRNA vaccines is the speed at which they can be designed and produced. This is why they lead the pack among the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates and why the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided financial, technical, and/or clinical support. Indeed, once the amino acid sequence of a protein can be determined (a relatively easy task these days) it’s straightforward to synthesize mRNA in the lab – and it can be done incredibly fast. It is reported that the mRNA code for the vaccine by Moderna was made in 2 days and production development was completed in about 2 months.2

A 2007 World Health Organization report noted that infectious diseases are emerging at “the historically unprecedented rate of one per year.”3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Zika, Ebola, and avian and swine flu are recent examples. For most vaccines against emerging diseases, the challenge is about speed: developing and manufacturing a vaccine and getting it to persons who need it as quickly as possible. The current seasonal flu vaccine takes about 6 months to develop; it takes years for most of the traditional vaccines. That’s why once the infrastructure is in place, mRNA vaccines may prove to offer a big advantage as vaccines against emerging pathogens.

Early efficacy results have been surprising

Both vaccines were reported to produce about 95% efficacy in the final analysis. That was unexpectedly high because most vaccines for respiratory illness achieve efficacy of 60%-80%, e.g., flu vaccines. However, the efficacy rate may drop as time goes by because stimulation of short-term immunity would be in the earliest reported results.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 cases is an important aspect of a coronavirus vaccine, but preventing severe illness is especially important considering that severe cases can result in prolonged intubation/artificial ventilation, prolonged disability and death. Pfizer/BioNTech had not released any data on the breakdown of severe cases as this column was finalized. In Moderna’s clinical trial, a secondary endpoint analyzed severe cases of COVID-19 and included 30 severe cases (as defined in the study protocol) in this analysis. All 30 cases occurred in the placebo group and none in the mRNA-1273–vaccinated group. In the Pfizer/BioNTech trial there were too few cases of severe illness to calculate efficacy.

Duration of immunity and need to revaccinate after initial primary vaccination are unknowns. Study of induction of B- and T-cell memory and levels of long-term protection have not been reported thus far.

Could mRNA COVID-19 vaccines be dangerous in the long term?

These will be the first-ever mRNA vaccines brought to market for humans. In order to receive Food and Drug Administration approval, the companies had to prove there were no immediate or short-term negative adverse effects from the vaccines. The companies reported that their independent data-monitoring committees hadn’t “reported any serious safety concerns.” However, fairly significant local reactions at the site of injection, fever, malaise, and fatigue occur with modest frequency following vaccinations with these products, reportedly in 10%-15% of vaccinees. Overall, the immediate reaction profile appears to be more severe than what occurs following seasonal influenza vaccination. When mass inoculations with these completely new and revolutionary vaccines begins, we will know virtually nothing about their long-term side effects. The possibility of systemic inflammatory responses that could lead to autoimmune conditions, persistence of the induced immunogen expression, development of autoreactive antibodies, and toxic effects of delivery components have been raised as theoretical concerns.4-6 None of these theoretical risks have been observed to date and postmarketing phase 4 safety monitoring studies are in place from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the companies that produce the vaccines. This is a risk public health authorities are willing to take because the risk to benefit calculation strongly favors taking theoretical risks, compared with clear benefits in preventing severe illnesses and death.

What about availability?

Pfizer/BioNTech expects to be able to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Moderna expects to produce 20 million doses by the end of 2020, and 500 million to 1 billion doses in 2021. Storage requirements are inherent to the composition of the vaccines with their differing lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2 has to be stored and transported at –80° C, which requires specialized freezers, which most doctors’ offices and pharmacies are unlikely to have on site, or dry ice containers. Once the vaccine is thawed, it can only remain in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Moderna’s mRNA-1273 will be much easier to distribute. The vaccine is stable in a standard freezer at –20° C for up to 6 months, in a refrigerator for up to 30 days within that 6-month shelf life, and at room temperature for up to 12 hours.

Timelines and testing other vaccines

Strong efficacy data from the two leading SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and emergency-use authorization Food and Drug Administration approval suggest the window for testing additional vaccine candidates in the United States could soon start to close. Of the more than 200 vaccines in development for SARS-CoV-2, at least 7 have a chance of gathering pivotal data before the front-runners become broadly available.

Testing diverse vaccine candidates, based on different technologies, is important for ensuring sufficient supply and could lead to products with tolerability and safety profiles that make them better suited, or more attractive, to subsets of the population. Different vaccine antigens and technologies also may yield different durations of protection, a question that will not be answered until long after the first products are on the market.

AstraZeneca enrolled about 23,000 subjects into its two phase 3 trials of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19): a 40,000-subject U.S. trial and a 10,000-subject study in Brazil. AstraZeneca’s AZD1222, developed with the University of Oxford (England), uses a replication defective simian adenovirus vector called ChAdOx1.AZD1222 which encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. After injection, the viral vector delivers recombinant DNA that is decoded to mRNA, followed by mRNA decoding to become a protein. A serendipitous manufacturing error for the first 3,000 doses resulted in a half dose for those subjects before the error was discovered. Full doses were given to those subjects on second injections and those subjects showed 90% efficacy. Subjects who received 2 full doses showed 62% efficacy. A vaccine cannot be licensed based on 3,000 subjects so AstraZeneca has started a new phase 3 trial involving many more subjects to receive the combination lower dose followed by the full dose.

Johnson and Johnson (J&J) started its phase 3 trial evaluating a single dose of JNJ-78436735 in September. Phase 3 data may be reported by the end of2020. In November, J&J announced it was starting a second phase 3 trial to test two doses of the candidate. J&J’s JNJ-78436735 encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in an adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector, which is one of the two adenovirus vectors used in Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine reported to have 90% efficacy at an early interim analysis.

Sanofi and Novavax are both developing protein-based vaccines, a proven modality. Sanofi, in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline started a phase 1/2 clinical trial in the Fall 2020 with plans to commence a phase 3 trial in late December. Sanofi developed the protein ingredients and GlaxoSmithKline added one of their novel adjuvants. Novavax expects data from a U.K. phase 3 trial of NVX-CoV2373 in early 2021 and began a U.S. phase 3 study in late November. NVX-CoV2373 was created using Novavax’ recombinant nanoparticle technology to generate antigen derived from the coronavirus spike protein and contains Novavax’s patented saponin-based Matrix-M adjuvant.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals was gearing up to start a U.S. phase 2/3 trial of DNA vaccine INO-4800 by the end of 2020.

After Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, CureVac has the next most advanced mRNA vaccine. It was planned that a phase 2b/3 trial of CVnCoV would be conducted in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Sanofi is also developing a mRNA vaccine as a second product in addition to its protein vaccine.

Vaxxinity planned to begin phase 3 testing of UB-612, a multitope peptide–based vaccine, in Brazil by the end of 2020.

However, emergency-use authorizations for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines could hinder trial recruitment in at least two ways. Given the gravity of the pandemic, some stakeholders believe it would be ethical to unblind ongoing trials to give subjects the opportunity to switch to a vaccine proven to be effective. Even if unblinding doesn’t occur, as the two authorized vaccines start to become widely available, volunteering for clinical trials may become less attractive.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Pichichero at [email protected].

References

1. Wolff JA et al. Science. 1990 Mar 23. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918.

2. Jackson LA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483.

3. Prentice T and Reinders LT. The world health report 2007. (Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007).

4. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

5. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

6. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

In mid-November, Pfizer/BioNTech were the first with surprising positive protection interim data for their coronavirus vaccine, BNT162b2. A week later, Moderna released interim efficacy results showing its coronavirus vaccine, mRNA-1273, also protected patients from developing SARS-CoV-2 infections. Both studies included mostly healthy adults. A diverse ethnic and racial vaccinated population was included. A reasonable number of persons aged over 65 years, and persons with stable compromising medical conditions were included. Adolescents aged 16 years and over were included. Younger adolescents have been vaccinated or such studies are in the planning or early implementation stage as 2020 came to a close.

These are new and revolutionary vaccines, although the ability to inject mRNA into animals dates back to 1990, technological advances today make it a reality.1 Traditional vaccines typically involve injection with antigens such as purified proteins or polysaccharides or inactivated/attenuated viruses. In the case of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s vaccines, the mRNA provides the genetic information to synthesize the spike protein that the SARS-CoV-2 virus uses to attach to and infect human cells. Each type of vaccine is packaged in proprietary lipid nanoparticles to protect the mRNA from rapid degradation, and the nanoparticles serve as an adjuvant to attract immune cells to the site of injection. (The properties of the respective lipid nanoparticle packaging may be the factor that impacts storage requirements discussed below.) When injected into muscle (myocyte), the lipid nanoparticles containing the mRNA inside are taken into muscle cells, where the cytoplasmic ribosomes detect and decode the mRNA resulting in the production of the spike protein antigen. It should be noted that the mRNA does not enter the nucleus, where the genetic information (DNA) of a cell is located, and can’t be reproduced or integrated into the DNA. The antigen is exported to the myocyte cell surface where the immune system’s antigen presenting cells detect the protein, ingest it, and take it to regional lymph nodes where interactions with T cells and B cells results in antibodies, T cell–mediated immunity, and generation of immune memory T cells and B cells. A particular subset of T cells – cytotoxic or killer T cells – destroy cells that have been infected by a pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine from Pfizer was reported to induce powerful cytotoxic T-cell responses. Results for Moderna’s vaccine had not been reported at the time this column was prepared, but I anticipate the same positive results.

The revolutionary aspect of mRNA vaccines is the speed at which they can be designed and produced. This is why they lead the pack among the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates and why the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases provided financial, technical, and/or clinical support. Indeed, once the amino acid sequence of a protein can be determined (a relatively easy task these days) it’s straightforward to synthesize mRNA in the lab – and it can be done incredibly fast. It is reported that the mRNA code for the vaccine by Moderna was made in 2 days and production development was completed in about 2 months.2

A 2007 World Health Organization report noted that infectious diseases are emerging at “the historically unprecedented rate of one per year.”3 Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Zika, Ebola, and avian and swine flu are recent examples. For most vaccines against emerging diseases, the challenge is about speed: developing and manufacturing a vaccine and getting it to persons who need it as quickly as possible. The current seasonal flu vaccine takes about 6 months to develop; it takes years for most of the traditional vaccines. That’s why once the infrastructure is in place, mRNA vaccines may prove to offer a big advantage as vaccines against emerging pathogens.

Early efficacy results have been surprising

Both vaccines were reported to produce about 95% efficacy in the final analysis. That was unexpectedly high because most vaccines for respiratory illness achieve efficacy of 60%-80%, e.g., flu vaccines. However, the efficacy rate may drop as time goes by because stimulation of short-term immunity would be in the earliest reported results.

Preventing SARS-CoV-2 cases is an important aspect of a coronavirus vaccine, but preventing severe illness is especially important considering that severe cases can result in prolonged intubation/artificial ventilation, prolonged disability and death. Pfizer/BioNTech had not released any data on the breakdown of severe cases as this column was finalized. In Moderna’s clinical trial, a secondary endpoint analyzed severe cases of COVID-19 and included 30 severe cases (as defined in the study protocol) in this analysis. All 30 cases occurred in the placebo group and none in the mRNA-1273–vaccinated group. In the Pfizer/BioNTech trial there were too few cases of severe illness to calculate efficacy.

Duration of immunity and need to revaccinate after initial primary vaccination are unknowns. Study of induction of B- and T-cell memory and levels of long-term protection have not been reported thus far.

Could mRNA COVID-19 vaccines be dangerous in the long term?

These will be the first-ever mRNA vaccines brought to market for humans. In order to receive Food and Drug Administration approval, the companies had to prove there were no immediate or short-term negative adverse effects from the vaccines. The companies reported that their independent data-monitoring committees hadn’t “reported any serious safety concerns.” However, fairly significant local reactions at the site of injection, fever, malaise, and fatigue occur with modest frequency following vaccinations with these products, reportedly in 10%-15% of vaccinees. Overall, the immediate reaction profile appears to be more severe than what occurs following seasonal influenza vaccination. When mass inoculations with these completely new and revolutionary vaccines begins, we will know virtually nothing about their long-term side effects. The possibility of systemic inflammatory responses that could lead to autoimmune conditions, persistence of the induced immunogen expression, development of autoreactive antibodies, and toxic effects of delivery components have been raised as theoretical concerns.4-6 None of these theoretical risks have been observed to date and postmarketing phase 4 safety monitoring studies are in place from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the companies that produce the vaccines. This is a risk public health authorities are willing to take because the risk to benefit calculation strongly favors taking theoretical risks, compared with clear benefits in preventing severe illnesses and death.

What about availability?

Pfizer/BioNTech expects to be able to produce up to 50 million vaccine doses in 2020 and up to 1.3 billion doses in 2021. Moderna expects to produce 20 million doses by the end of 2020, and 500 million to 1 billion doses in 2021. Storage requirements are inherent to the composition of the vaccines with their differing lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT162b2 has to be stored and transported at –80° C, which requires specialized freezers, which most doctors’ offices and pharmacies are unlikely to have on site, or dry ice containers. Once the vaccine is thawed, it can only remain in the refrigerator for 24 hours. Moderna’s mRNA-1273 will be much easier to distribute. The vaccine is stable in a standard freezer at –20° C for up to 6 months, in a refrigerator for up to 30 days within that 6-month shelf life, and at room temperature for up to 12 hours.

Timelines and testing other vaccines

Strong efficacy data from the two leading SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and emergency-use authorization Food and Drug Administration approval suggest the window for testing additional vaccine candidates in the United States could soon start to close. Of the more than 200 vaccines in development for SARS-CoV-2, at least 7 have a chance of gathering pivotal data before the front-runners become broadly available.

Testing diverse vaccine candidates, based on different technologies, is important for ensuring sufficient supply and could lead to products with tolerability and safety profiles that make them better suited, or more attractive, to subsets of the population. Different vaccine antigens and technologies also may yield different durations of protection, a question that will not be answered until long after the first products are on the market.

AstraZeneca enrolled about 23,000 subjects into its two phase 3 trials of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19): a 40,000-subject U.S. trial and a 10,000-subject study in Brazil. AstraZeneca’s AZD1222, developed with the University of Oxford (England), uses a replication defective simian adenovirus vector called ChAdOx1.AZD1222 which encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. After injection, the viral vector delivers recombinant DNA that is decoded to mRNA, followed by mRNA decoding to become a protein. A serendipitous manufacturing error for the first 3,000 doses resulted in a half dose for those subjects before the error was discovered. Full doses were given to those subjects on second injections and those subjects showed 90% efficacy. Subjects who received 2 full doses showed 62% efficacy. A vaccine cannot be licensed based on 3,000 subjects so AstraZeneca has started a new phase 3 trial involving many more subjects to receive the combination lower dose followed by the full dose.

Johnson and Johnson (J&J) started its phase 3 trial evaluating a single dose of JNJ-78436735 in September. Phase 3 data may be reported by the end of2020. In November, J&J announced it was starting a second phase 3 trial to test two doses of the candidate. J&J’s JNJ-78436735 encodes the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in an adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vector, which is one of the two adenovirus vectors used in Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine reported to have 90% efficacy at an early interim analysis.

Sanofi and Novavax are both developing protein-based vaccines, a proven modality. Sanofi, in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline started a phase 1/2 clinical trial in the Fall 2020 with plans to commence a phase 3 trial in late December. Sanofi developed the protein ingredients and GlaxoSmithKline added one of their novel adjuvants. Novavax expects data from a U.K. phase 3 trial of NVX-CoV2373 in early 2021 and began a U.S. phase 3 study in late November. NVX-CoV2373 was created using Novavax’ recombinant nanoparticle technology to generate antigen derived from the coronavirus spike protein and contains Novavax’s patented saponin-based Matrix-M adjuvant.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals was gearing up to start a U.S. phase 2/3 trial of DNA vaccine INO-4800 by the end of 2020.

After Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, CureVac has the next most advanced mRNA vaccine. It was planned that a phase 2b/3 trial of CVnCoV would be conducted in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Sanofi is also developing a mRNA vaccine as a second product in addition to its protein vaccine.

Vaxxinity planned to begin phase 3 testing of UB-612, a multitope peptide–based vaccine, in Brazil by the end of 2020.

However, emergency-use authorizations for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines could hinder trial recruitment in at least two ways. Given the gravity of the pandemic, some stakeholders believe it would be ethical to unblind ongoing trials to give subjects the opportunity to switch to a vaccine proven to be effective. Even if unblinding doesn’t occur, as the two authorized vaccines start to become widely available, volunteering for clinical trials may become less attractive.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He said he has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Pichichero at [email protected].

References

1. Wolff JA et al. Science. 1990 Mar 23. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918.

2. Jackson LA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483.

3. Prentice T and Reinders LT. The world health report 2007. (Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007).

4. Peck KM and Lauring AS. J Virol. 2018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01031-17.

5. Pepini T et al. J Immunol. 2017 May 15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601877.

6. Theofilopoulos AN et al. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843.

Diet and Skin: A Primer

Dermatologists frequently learn about skin conditions that are directly linked to diet. For example, we know that nutritional deficiencies can impact the hair, skin, and nails, and that celiac disease manifests with dermatitis herpetiformis of the skin. Patients commonly ask their dermatologists about the impact of diet on their skin. There are many outdated myths, but research on the subject is increasingly demonstrating important associations. Dermatologists must become familiar with the data on this topic so that we can provide informed counseling for our patients. This article reviews the current literature on associations between diet and 3 common cutaneous conditions—acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis [AD]—and provides tips on how to best address our patients’ questions on this topic.

Acne

Studies increasingly support an association between a high glycemic diet (foods that lead to a spike in serum glucose) and acne; Bowe et al1 provided an excellent summary of the topic in 2010. This year, a large prospective cohort study of more than 24,000 participants demonstrated an association between adult acne and a diet high in milk, sugary beverages and foods, and fatty foods.2 In prospective cohort studies of more than 6000 adolescent girls and 4000 adolescent boys, Adebamowo et al3,4 demonstrated a correlation between skim milk consumption and acne. Whey protein supplementation also has been implicated in acne flares.5,6 The biological mechanism of the impact of high glycemic index foods and acne is believed to be mainly via activation of the insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) pathway, which promotes androgen synthesis and increases androgen bioavailability via decreased synthesis of sex hormone binding globulin.1,2 Insulinlike growth factor 1 also stimulates its downstream target, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), leading to activation of antiapoptotic and proliferation signaling, ultimately resulting in oxidative stress and inflammation causing acne.2 Penso et al2 noted that patients with IGF-1 deficiency (Laron syndrome) never develop acne unless treated with exogenous IGF-1, further supporting its role in acne formation.7 There currently is a paucity of randomized controlled trials assessing the impact of diet on acne.

Psoriasis

The literature consistently shows that obesity is a predisposing factor for psoriasis. Additionally, weight gain may cause flares of existing psoriasis.8 Promotion of a healthy diet is an important factor in the management of obesity, alongside physical activity and, in some cases, medication and bariatric surgery.9 Patients with psoriasis who are overweight have been shown to experience improvement in their psoriasis after weight loss secondary to diet and exercise.8,10 The joint American Academy of Dermatology and National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines recommend that dermatologists advise patients to practice a healthy lifestyle including a healthy diet and communicate with a patient’s primary care provider so they can be appropriately evaluated and treated for comorbidities including metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.11 In the NutriNet-Santé cohort study, investigators found an inverse correlation between psoriasis severity and adherence to a Mediterranean diet, which the authors conclude supports the hypothesis that this may slow the progression of psoriasis.12 In a single meta-analysis, it was reported that patients with psoriasis have a 3-fold increased risk for celiac disease compared to the general population.13 It remains unknown if these data are generalizable to the US population. Dermatologists should consider screening patients with psoriasis for celiac disease based on reported symptoms. When suspected, it is necessary to order appropriate serologies and consider referral to gastroenterology prior to recommending a gluten-free diet, as elimination of gluten prior to testing may lead to false-negative results.

Atopic Dermatitis

Patients and parents/guardians of children with AD often ask about the impact of diet on the condition. A small minority of patients may experience flares of AD due to ongoing, non–IgE-mediated allergen exposure.14 Diet as a trigger for flares should be suspected in children with persistent, moderate to severe AD. In these patients, allergen avoidance may lead to improvement but not resolution of AD. Allergens ordered from most common to least common are the following: eggs, milk, peanuts/tree nuts, shellfish, soy, and wheat.15 Additionally, it is important to note that children with AD are at higher risk for developing life-threatening, IgE-mediated food allergies compared to the general population (37% vs 6.8%).16,17 The LEAP (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy) study led to a paradigm shift in prevention of peanut allergies in high-risk children (ie, those with severe AD and/or egg allergy), providing data to support the idea that early introduction of allergenic foods such as peanuts may prevent severe allergies.18 Further studies are necessary to clarify the population in which allergen testing and recommendations on food avoidance are warranted vs early introduction.19

Conclusion

Early data support the relationship between diet and many common dermatologic conditions, including acne, psoriasis, and AD. Dermatologists should be familiar with the evidence supporting the relationship between diet and various skin conditions to best answer patients’ questions and counsel as appropriate. It is important for dermatologists to continue to stay up-to-date on the literature on this subject as new data emerge. Knowledge about the relationship between diet and skin allows dermatologists to not only support our patients’ skin health but their overall health as well.

- Bowe WP, Joshi SS, Shalita AR. Diet and acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:124-141.

- Penso L, Touvier M, Deschasaux M, et al. Association between adult acne and dietary behaviors: findings from the NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:854-862.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:787-793.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in adolescent girls. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:1.

- Silverberg NB. Whey protein precipitating moderate to severe acne flares in 5 teenaged athletes. Cutis. 2012;90:70-72.

- Cengiz FP, Cemil BC, Emiroglu N, et al. Acne located on the trunk, whey protein supplementation: is there any association? Health Promot Perspect. 2017;7:106-108.

- Ben-Amitai D, Laron Z. Effect of insulin-like growth factor-1 deficiency or administration on the occurrence of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:950-954.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity [published online February 23, 2017]. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Extreme obesity, and what you can do. American Heart Association website. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/losing-weight/extreme-obesity-and-what-you-can-do. Updated April 18, 2014. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- Naldi L, Conti A, Cazzaniga S, et al. Diet and physical exercise in psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:634-642.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Phan C, Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Association between Mediterranean anti-inflammatory dietary profile and severity of psoriasis: results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1017-1024.

- Ungprasert P, Wijarnpreecha K, Kittanamongkolchai W. Psoriasis and risk of celiac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:41-46.

- Silverberg NB, Lee-Wong M, Yosipovitch G. Diet and atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2016;97:227-232.

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:203-218.

- Eigenmann PA, Sicherer SH, Borkowski TA, et al. Prevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1998;101:E8.

- Age-adjusted percentages (with standard errors) of hay fever, respiratory allergies, food allergies, and skin allergies in the past 12 months for children under age 18 years, by selected characteristics: United States, 2016. CDC website. https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2016_SHS_Table_C-2.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2020.

- Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al; LEAP study team. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803-813.

- Sugita K, Akdis CA. Recent developments and advances in atopic dermatitis and food allergy [published online October 22, 2019]. Allergol Int. 2020;69:204-214.

Dermatologists frequently learn about skin conditions that are directly linked to diet. For example, we know that nutritional deficiencies can impact the hair, skin, and nails, and that celiac disease manifests with dermatitis herpetiformis of the skin. Patients commonly ask their dermatologists about the impact of diet on their skin. There are many outdated myths, but research on the subject is increasingly demonstrating important associations. Dermatologists must become familiar with the data on this topic so that we can provide informed counseling for our patients. This article reviews the current literature on associations between diet and 3 common cutaneous conditions—acne, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis [AD]—and provides tips on how to best address our patients’ questions on this topic.

Acne