User login

Long-Awaited RSV Vaccines Now Available for Older Adults and Pediatric Patients

- Jha A et al. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Hui DS, Rossi GA, Johnston SL, eds. Respiratory Syncytial Virus. SARS, MERS and Other Viral Lung Infections. European Respiratory Society; 2016:chap 5. Accessed May 17, 2023.

- Ginsburg SA, Srikantiah P. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(12):e1644-e6145. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00455-1

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine [press release]. Published May 3, 2023. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Drug to Prevent RSV in Babies and Toddlers [press release]. Published July 17, 2023. Accessed August 11, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-prevent-rsv-babies-and-toddlers

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Vaccine for Pregnant Individuals to Prevent RSV in Infants. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants

- Madhi SA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):426-439. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa1908380

- Centers for Disease Control. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Meeting recommendations, August 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

- Hammit LL et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837-846. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa2110275

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in infants and young children. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/ high-risk/infants-young-children.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in older adults and adults with chronic medical conditions. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/older-adults.html

- Widmer K et al. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):56-62. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis309

- Hall CB et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588-598. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804877

- McLaughlin JM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac300. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac300

- Thompson et al. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179-186. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.179

- Hansen CL et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220527. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527

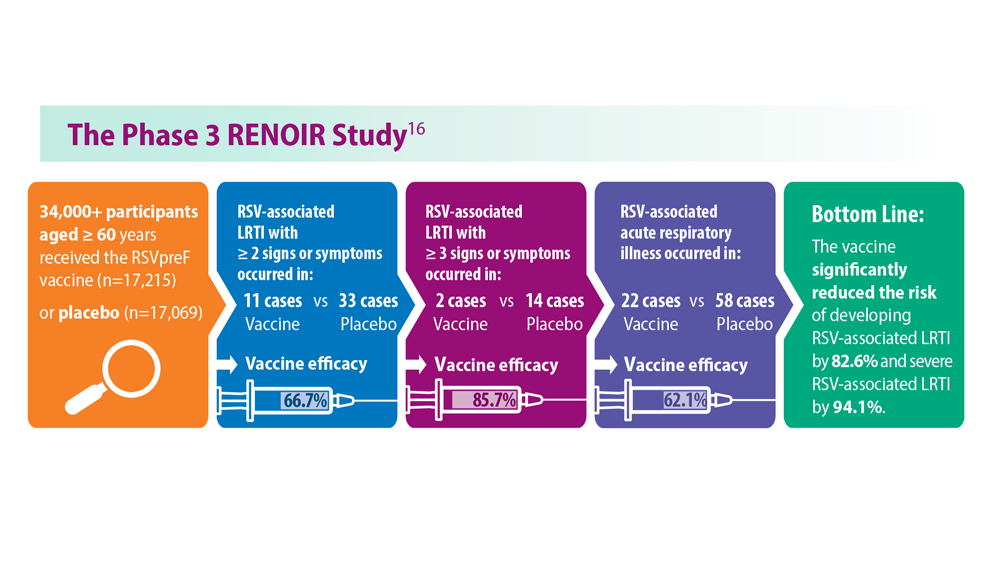

- Walsh EE et al; RENOIR Clinical Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1465-1477. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213836

- Martin JA et al. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1-47. PMID:32501202

- Townsi N et al. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5(1):1487214. doi:10.1080/20018525.20 18.1487214

- Malek A et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1994;32(1):8-14. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1994.tb00873.x

- Kampmann B et al; MATISSE Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1451- 1464. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2216480

- Synagis (palivizumab) injection prescribing information. Published June 2023. Accessed August 2023. https://www.synagis.com/synagis.pdf

- Jha A et al. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Hui DS, Rossi GA, Johnston SL, eds. Respiratory Syncytial Virus. SARS, MERS and Other Viral Lung Infections. European Respiratory Society; 2016:chap 5. Accessed May 17, 2023.

- Ginsburg SA, Srikantiah P. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(12):e1644-e6145. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00455-1

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine [press release]. Published May 3, 2023. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Drug to Prevent RSV in Babies and Toddlers [press release]. Published July 17, 2023. Accessed August 11, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-prevent-rsv-babies-and-toddlers

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Vaccine for Pregnant Individuals to Prevent RSV in Infants. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants

- Madhi SA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):426-439. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa1908380

- Centers for Disease Control. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Meeting recommendations, August 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

- Hammit LL et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837-846. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa2110275

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in infants and young children. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/ high-risk/infants-young-children.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in older adults and adults with chronic medical conditions. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/older-adults.html

- Widmer K et al. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):56-62. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis309

- Hall CB et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588-598. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804877

- McLaughlin JM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac300. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac300

- Thompson et al. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179-186. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.179

- Hansen CL et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220527. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527

- Walsh EE et al; RENOIR Clinical Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1465-1477. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213836

- Martin JA et al. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1-47. PMID:32501202

- Townsi N et al. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5(1):1487214. doi:10.1080/20018525.20 18.1487214

- Malek A et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1994;32(1):8-14. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1994.tb00873.x

- Kampmann B et al; MATISSE Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1451- 1464. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2216480

- Synagis (palivizumab) injection prescribing information. Published June 2023. Accessed August 2023. https://www.synagis.com/synagis.pdf

- Jha A et al. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Hui DS, Rossi GA, Johnston SL, eds. Respiratory Syncytial Virus. SARS, MERS and Other Viral Lung Infections. European Respiratory Society; 2016:chap 5. Accessed May 17, 2023.

- Ginsburg SA, Srikantiah P. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(12):e1644-e6145. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00455-1

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine [press release]. Published May 3, 2023. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Drug to Prevent RSV in Babies and Toddlers [press release]. Published July 17, 2023. Accessed August 11, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-prevent-rsv-babies-and-toddlers

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Vaccine for Pregnant Individuals to Prevent RSV in Infants. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants

- Madhi SA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):426-439. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa1908380

- Centers for Disease Control. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Meeting recommendations, August 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

- Hammit LL et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837-846. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa2110275

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in infants and young children. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/ high-risk/infants-young-children.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in older adults and adults with chronic medical conditions. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/older-adults.html

- Widmer K et al. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):56-62. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis309

- Hall CB et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588-598. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804877

- McLaughlin JM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac300. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac300

- Thompson et al. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179-186. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.179

- Hansen CL et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220527. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527

- Walsh EE et al; RENOIR Clinical Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1465-1477. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213836

- Martin JA et al. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1-47. PMID:32501202

- Townsi N et al. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5(1):1487214. doi:10.1080/20018525.20 18.1487214

- Malek A et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1994;32(1):8-14. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1994.tb00873.x

- Kampmann B et al; MATISSE Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1451- 1464. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2216480

- Synagis (palivizumab) injection prescribing information. Published June 2023. Accessed August 2023. https://www.synagis.com/synagis.pdf

How exercise boosts the body’s ability to prevent cancer

That amount of exercise made the immune system more able to stamp out cancer cells, researchers at the found. The intervention was specific by design, said Eduardo Vilar-Sanchez, MD, PhD, a professor of clinical cancer prevention at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and the study’s lead author.

“We wanted to be very concrete on the recommendation,” he said. “People don’t adhere to vague lifestyle advice like ‘just exercise.’ We wanted to link a specific biologic effect to a very concrete intervention.”

The study was small (just 21 people), but it builds on a vast body of evidence linking regular exercise to a decreased risk of cancer, particularly colorectal cancer. But the researchers went a step further, investigating how exercise might lower cancer risk.

Exercise and the immune system

All 21 people in the study had Lynch syndrome, and they were divided into two groups. One was given a 12-month exercise program; the other was not. The scientists checked their cardio and respiratory fitness and tracked immune cells – natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells – in the blood and colon tissues.

“These are the immune cells that are in charge of attacking foreign entities like cancer cells,” Dr. Vilar-Sanchez said, “and they were more active with the participants who exercised.”

People in the exercise group also saw a drop in levels of the inflammatory marker prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). The drop was closely linked to the increase in immune cells. Both changes suggest a stronger immune response.

The researchers believe the changes relate to a boost in the body’s “immune surveillance” system for hunting down and clearing out cells that would otherwise become cancerous.

Building on prior research

Science already offers a lot of support that regular exercise can help prevent cancer. A massive 2019 systematic review of more than 45 studies and several million people found strong evidence that exercise can reduce the risk of several cancers – including bladder, breast, colorectal, and gastric cancers – by up to 20%.

But the MD Anderson study is the first to show a link between exercise and changes in immune biomarkers, the researchers said.

“One thing is having the epidemiological correlation, but it’s another thing to know the biological basis,” added Xavier Llor, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn, who was not involved in the study.

Two previous studies looked at exercise and inflammation markers in healthy people and in those with a history of colon polyps, but neither study produced meaningful results. This new study’s success could be caused by the higher-intensity exercise or extra colon tissue samples. But also, advances in technology now allow for more sensitive measurements, the researchers said.

Wider implications?

Dr. Vilar-Sanchez hesitated to extend the study findings beyond people with Lynch syndrome, but he’s optimistic that they may apply to the general population as well.

Dr. Llor agreed: “Exercise could be protective against other types of cancer through some of these mechanisms.”

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 15% of all cancer deaths (aside from tobacco-related cancers) in the United States are related to lifestyle factors, including physical inactivity, excess body weight, alcohol use, and poor nutrition. It recommends 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise a week to reduce cancer risk. People in the study saw a significant immune response with 135 minutes of high-intensity exercise a week.

“The public should know that engaging in any form of exercise will somehow lead to effects in cancer prevention,” Dr. Vilar-Sanchez said.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

That amount of exercise made the immune system more able to stamp out cancer cells, researchers at the found. The intervention was specific by design, said Eduardo Vilar-Sanchez, MD, PhD, a professor of clinical cancer prevention at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and the study’s lead author.

“We wanted to be very concrete on the recommendation,” he said. “People don’t adhere to vague lifestyle advice like ‘just exercise.’ We wanted to link a specific biologic effect to a very concrete intervention.”

The study was small (just 21 people), but it builds on a vast body of evidence linking regular exercise to a decreased risk of cancer, particularly colorectal cancer. But the researchers went a step further, investigating how exercise might lower cancer risk.

Exercise and the immune system

All 21 people in the study had Lynch syndrome, and they were divided into two groups. One was given a 12-month exercise program; the other was not. The scientists checked their cardio and respiratory fitness and tracked immune cells – natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells – in the blood and colon tissues.

“These are the immune cells that are in charge of attacking foreign entities like cancer cells,” Dr. Vilar-Sanchez said, “and they were more active with the participants who exercised.”

People in the exercise group also saw a drop in levels of the inflammatory marker prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). The drop was closely linked to the increase in immune cells. Both changes suggest a stronger immune response.

The researchers believe the changes relate to a boost in the body’s “immune surveillance” system for hunting down and clearing out cells that would otherwise become cancerous.

Building on prior research

Science already offers a lot of support that regular exercise can help prevent cancer. A massive 2019 systematic review of more than 45 studies and several million people found strong evidence that exercise can reduce the risk of several cancers – including bladder, breast, colorectal, and gastric cancers – by up to 20%.

But the MD Anderson study is the first to show a link between exercise and changes in immune biomarkers, the researchers said.

“One thing is having the epidemiological correlation, but it’s another thing to know the biological basis,” added Xavier Llor, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn, who was not involved in the study.

Two previous studies looked at exercise and inflammation markers in healthy people and in those with a history of colon polyps, but neither study produced meaningful results. This new study’s success could be caused by the higher-intensity exercise or extra colon tissue samples. But also, advances in technology now allow for more sensitive measurements, the researchers said.

Wider implications?

Dr. Vilar-Sanchez hesitated to extend the study findings beyond people with Lynch syndrome, but he’s optimistic that they may apply to the general population as well.

Dr. Llor agreed: “Exercise could be protective against other types of cancer through some of these mechanisms.”

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 15% of all cancer deaths (aside from tobacco-related cancers) in the United States are related to lifestyle factors, including physical inactivity, excess body weight, alcohol use, and poor nutrition. It recommends 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise a week to reduce cancer risk. People in the study saw a significant immune response with 135 minutes of high-intensity exercise a week.

“The public should know that engaging in any form of exercise will somehow lead to effects in cancer prevention,” Dr. Vilar-Sanchez said.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

That amount of exercise made the immune system more able to stamp out cancer cells, researchers at the found. The intervention was specific by design, said Eduardo Vilar-Sanchez, MD, PhD, a professor of clinical cancer prevention at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and the study’s lead author.

“We wanted to be very concrete on the recommendation,” he said. “People don’t adhere to vague lifestyle advice like ‘just exercise.’ We wanted to link a specific biologic effect to a very concrete intervention.”

The study was small (just 21 people), but it builds on a vast body of evidence linking regular exercise to a decreased risk of cancer, particularly colorectal cancer. But the researchers went a step further, investigating how exercise might lower cancer risk.

Exercise and the immune system

All 21 people in the study had Lynch syndrome, and they were divided into two groups. One was given a 12-month exercise program; the other was not. The scientists checked their cardio and respiratory fitness and tracked immune cells – natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells – in the blood and colon tissues.

“These are the immune cells that are in charge of attacking foreign entities like cancer cells,” Dr. Vilar-Sanchez said, “and they were more active with the participants who exercised.”

People in the exercise group also saw a drop in levels of the inflammatory marker prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). The drop was closely linked to the increase in immune cells. Both changes suggest a stronger immune response.

The researchers believe the changes relate to a boost in the body’s “immune surveillance” system for hunting down and clearing out cells that would otherwise become cancerous.

Building on prior research

Science already offers a lot of support that regular exercise can help prevent cancer. A massive 2019 systematic review of more than 45 studies and several million people found strong evidence that exercise can reduce the risk of several cancers – including bladder, breast, colorectal, and gastric cancers – by up to 20%.

But the MD Anderson study is the first to show a link between exercise and changes in immune biomarkers, the researchers said.

“One thing is having the epidemiological correlation, but it’s another thing to know the biological basis,” added Xavier Llor, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn, who was not involved in the study.

Two previous studies looked at exercise and inflammation markers in healthy people and in those with a history of colon polyps, but neither study produced meaningful results. This new study’s success could be caused by the higher-intensity exercise or extra colon tissue samples. But also, advances in technology now allow for more sensitive measurements, the researchers said.

Wider implications?

Dr. Vilar-Sanchez hesitated to extend the study findings beyond people with Lynch syndrome, but he’s optimistic that they may apply to the general population as well.

Dr. Llor agreed: “Exercise could be protective against other types of cancer through some of these mechanisms.”

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 15% of all cancer deaths (aside from tobacco-related cancers) in the United States are related to lifestyle factors, including physical inactivity, excess body weight, alcohol use, and poor nutrition. It recommends 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise a week to reduce cancer risk. People in the study saw a significant immune response with 135 minutes of high-intensity exercise a week.

“The public should know that engaging in any form of exercise will somehow lead to effects in cancer prevention,” Dr. Vilar-Sanchez said.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH

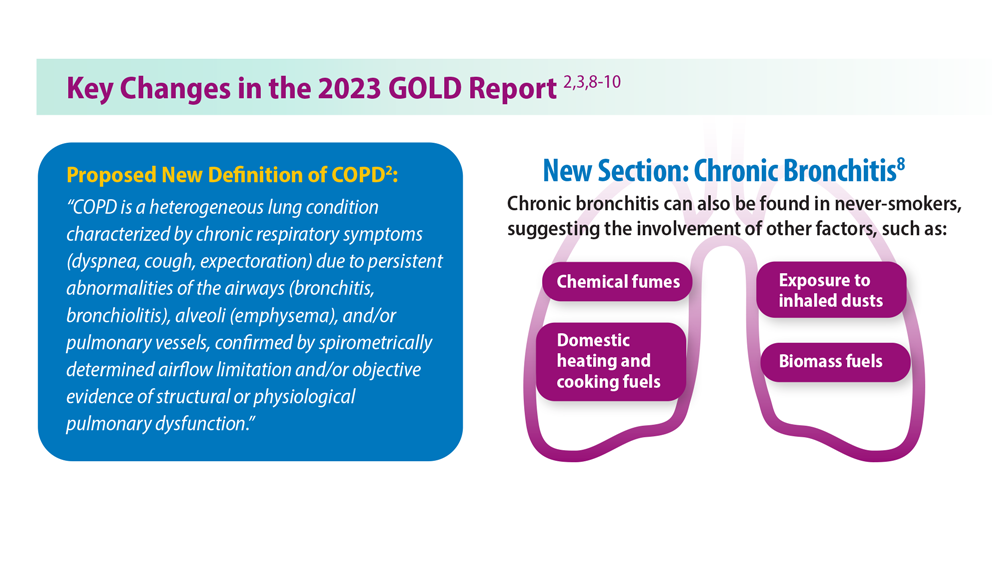

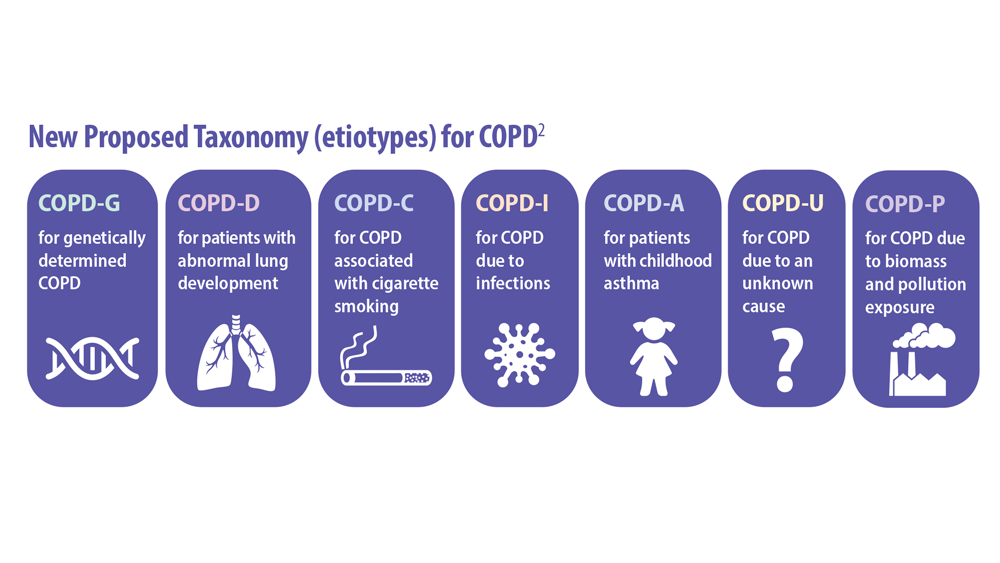

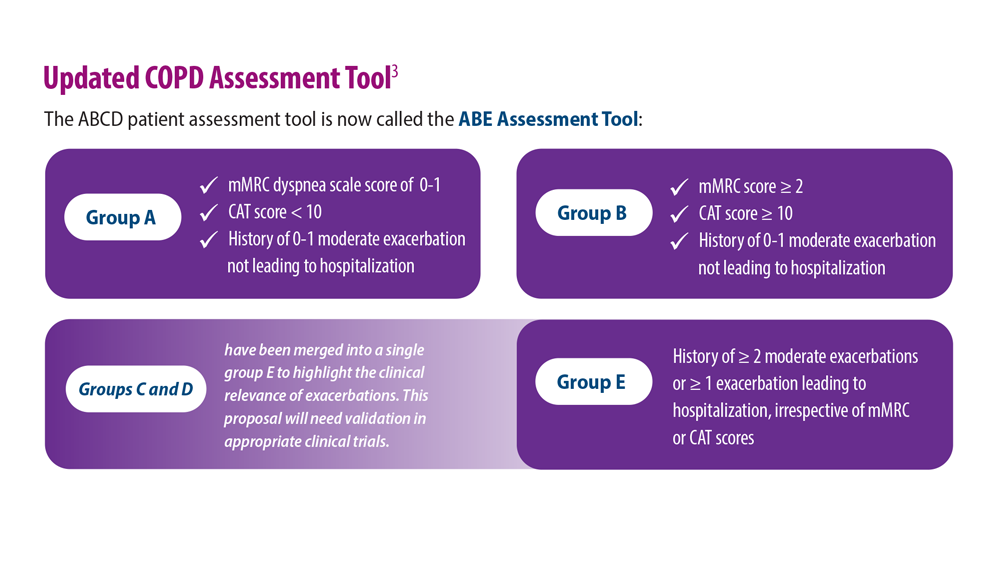

Updated Guidelines for COPD Management: 2023 GOLD Strategy Report

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Published 2023. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

- Celli B et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(11):1317. doi:10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP

- Han M et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):43-50. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70044-9

- Klijn SL et al. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):24. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0022-1

- Chan AH et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):335-349.e1-e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.024

- Brusselle G et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207-2217. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91694

- Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):733-743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9

- Trupin L et al. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):462-469. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00094203

- Celli BR et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(11):1251-1258. doi:10.1164/rccm.202108-1819PP

- Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165-1185. doi:10.1183/09031936.00128008

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Published 2023. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

- Celli B et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(11):1317. doi:10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP

- Han M et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):43-50. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70044-9

- Klijn SL et al. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):24. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0022-1

- Chan AH et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):335-349.e1-e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.024

- Brusselle G et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207-2217. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91694

- Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):733-743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9

- Trupin L et al. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):462-469. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00094203

- Celli BR et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(11):1251-1258. doi:10.1164/rccm.202108-1819PP

- Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165-1185. doi:10.1183/09031936.00128008

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (2023 Report). Published 2023. Accessed June 6, 2023. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

- Celli B et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(11):1317. doi:10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP

- Han M et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):43-50. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70044-9

- Klijn SL et al. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):24. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0022-1

- Chan AH et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3):335-349.e1-e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.01.024

- Brusselle G et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207-2217. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91694

- Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Lancet. 2009;374(9691):733-743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9

- Trupin L et al. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(3):462-469. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00094203

- Celli BR et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(11):1251-1258. doi:10.1164/rccm.202108-1819PP

- Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165-1185. doi:10.1183/09031936.00128008

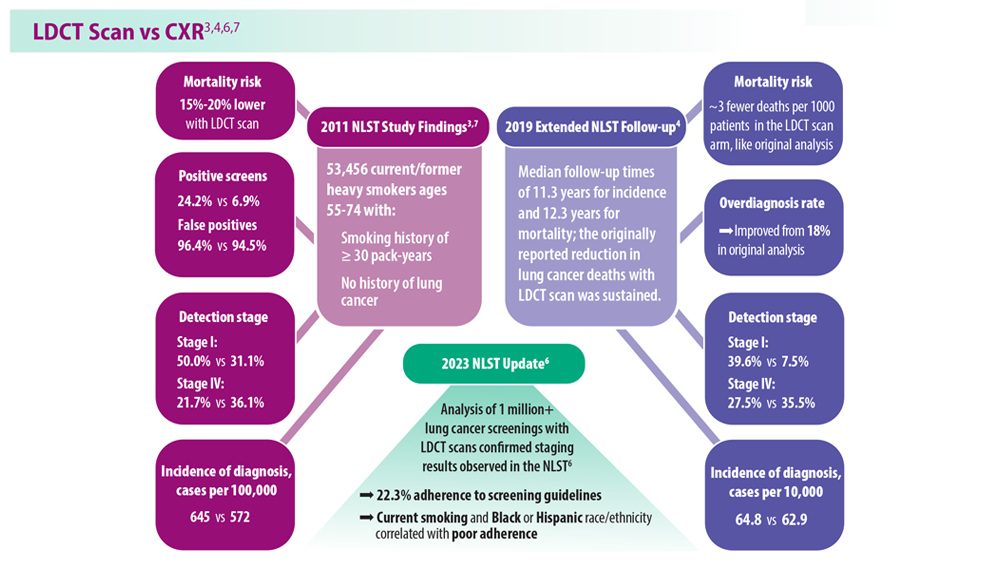

Lung Cancer Screening: A Need for Adjunctive Testing

- Naidch DP et al. Radiology. 1990;175(3):729-731. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343122

- Kaneko M et al. Radiology. 1996;201(3):798-802. doi:10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939234

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Radiology. 2011;258(1):243-253. doi:10.1148/radiol.10091808

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

- Mazzone PJ et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

- Tanner NT et al. Chest. 2023;S0012-3692(23)00175-7. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.003

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395- 409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Marmor HN et al. Curr Chall Thorac Surg. 2023;5:5. doi:10.21037/ccts-20-171

- Naidch DP et al. Radiology. 1990;175(3):729-731. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343122

- Kaneko M et al. Radiology. 1996;201(3):798-802. doi:10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939234

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Radiology. 2011;258(1):243-253. doi:10.1148/radiol.10091808

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

- Mazzone PJ et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

- Tanner NT et al. Chest. 2023;S0012-3692(23)00175-7. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.003

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395- 409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Marmor HN et al. Curr Chall Thorac Surg. 2023;5:5. doi:10.21037/ccts-20-171

- Naidch DP et al. Radiology. 1990;175(3):729-731. doi:10.1148/radiology.175.3.2343122

- Kaneko M et al. Radiology. 1996;201(3):798-802. doi:10.1148/radiology.201.3.8939234

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Radiology. 2011;258(1):243-253. doi:10.1148/radiol.10091808

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1732-1742. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044

- Mazzone PJ et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):e427-e494. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.063

- Tanner NT et al. Chest. 2023;S0012-3692(23)00175-7. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.003

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395- 409. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

- Marmor HN et al. Curr Chall Thorac Surg. 2023;5:5. doi:10.21037/ccts-20-171

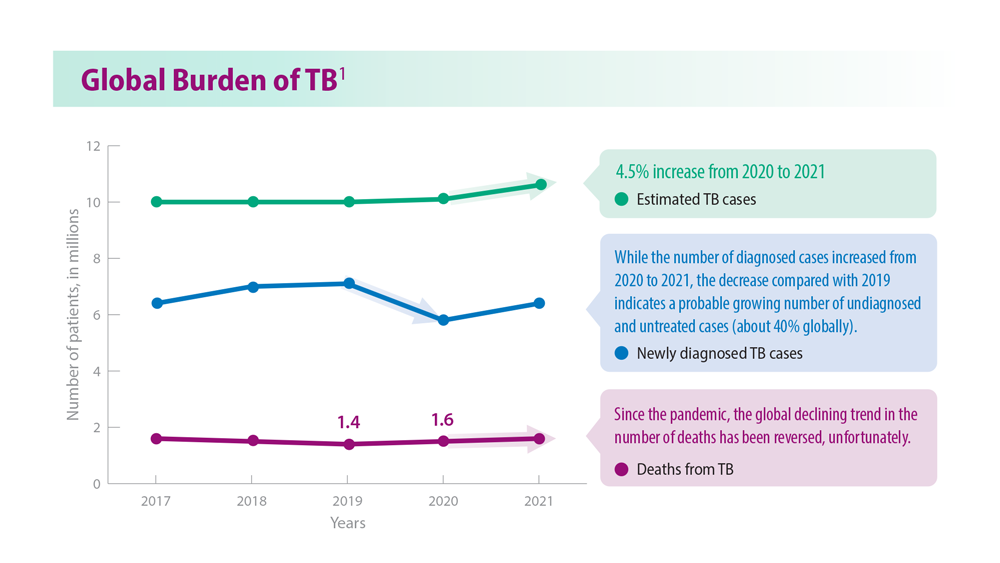

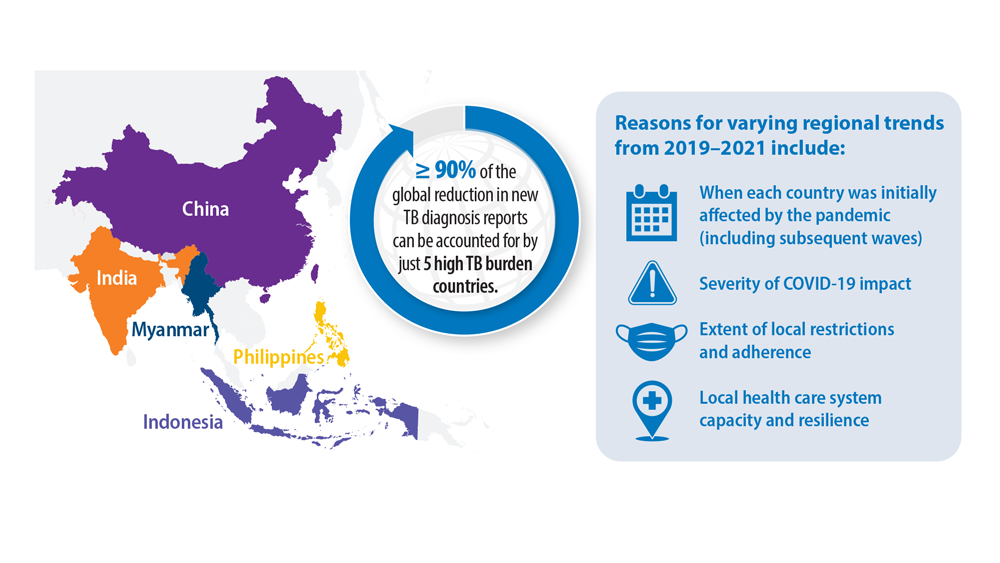

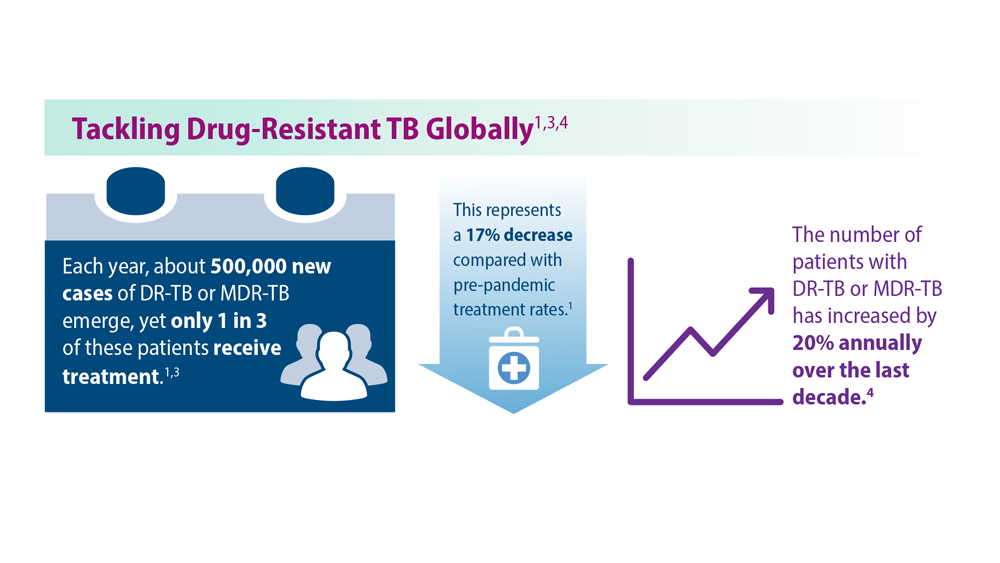

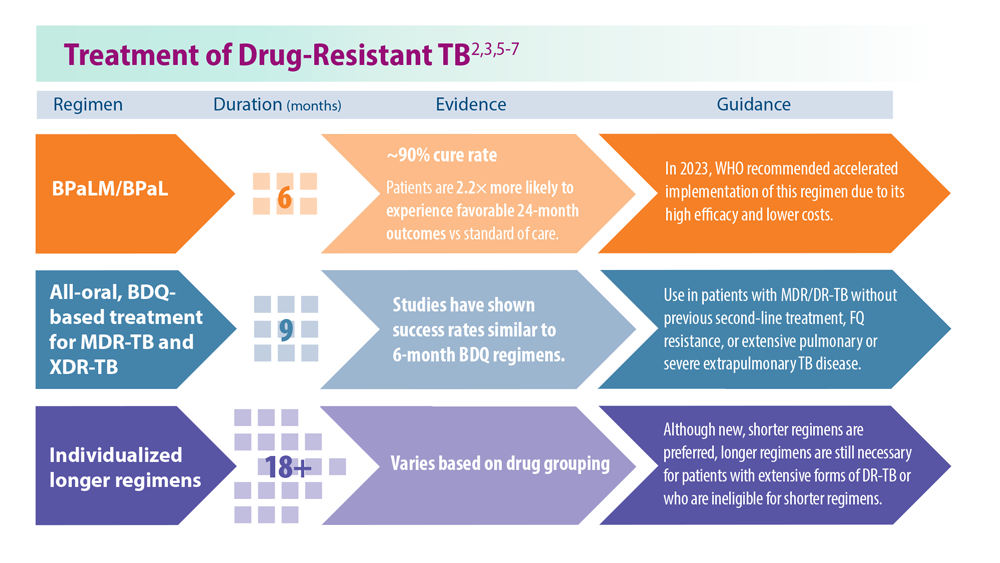

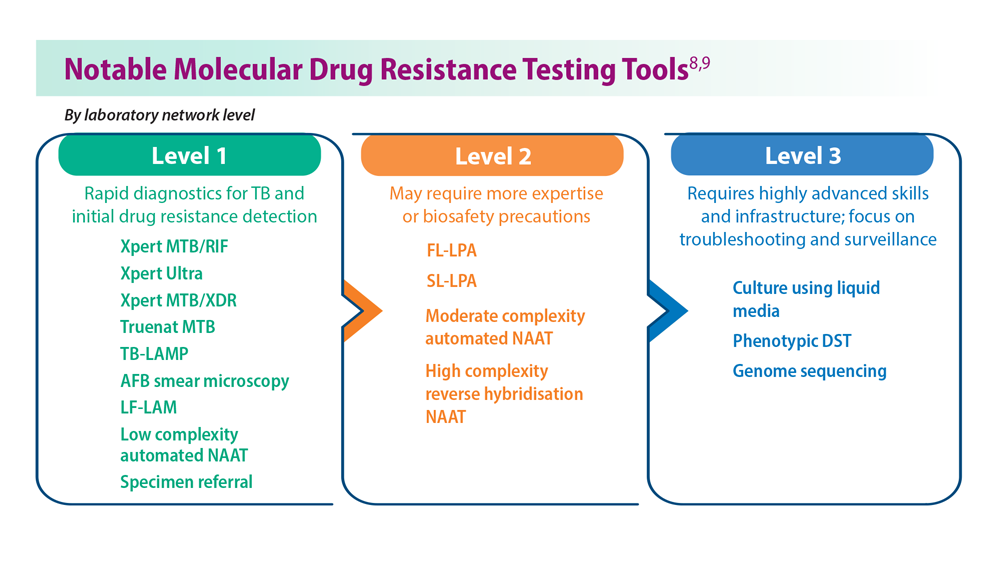

Tuberculosis Management: Returning to Pre-Pandemic Priorities

- Global tuberculosis report 2022. World Health Organization. Published October 27, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment – drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, 2022 update. World Health Organization. Published December 15, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063129

- Migliori GB, Tiberi S. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022 ;26(7):590-591. doi:10.5588/ijtld.22.0263.

- Lange C et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1142-1144. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0393ED

- Esmail A et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1214-1227. doi:10.1164/rccm.202107-1779OC

- WHO BPaLM Accelerator Platform: to support the call to action for implementation of the shorter and more effective treatment for all people suffering from drug-resistant TB. World Health Organization. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/05/09/default-calendar/who-bpalm-accelerator-platform–to-support-the-call-to-action-for-implementation-of-the-shorter-and-moreeffective-

- Trevisi L et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(11):1525-1532. doi:10.1164/rccm.202211-2125OC

- Domínguez J et al; TBnet and RESIST-TB networks. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(4):e122-e137. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00875-1

- WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis: module 3: diagnosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. World Health Organization. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030589treatment-for-all-people-suffering-from-drug-resistant-tb

- Global tuberculosis report 2022. World Health Organization. Published October 27, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment – drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, 2022 update. World Health Organization. Published December 15, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063129

- Migliori GB, Tiberi S. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022 ;26(7):590-591. doi:10.5588/ijtld.22.0263.

- Lange C et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1142-1144. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0393ED

- Esmail A et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1214-1227. doi:10.1164/rccm.202107-1779OC

- WHO BPaLM Accelerator Platform: to support the call to action for implementation of the shorter and more effective treatment for all people suffering from drug-resistant TB. World Health Organization. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/05/09/default-calendar/who-bpalm-accelerator-platform–to-support-the-call-to-action-for-implementation-of-the-shorter-and-moreeffective-

- Trevisi L et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(11):1525-1532. doi:10.1164/rccm.202211-2125OC

- Domínguez J et al; TBnet and RESIST-TB networks. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(4):e122-e137. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00875-1

- WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis: module 3: diagnosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. World Health Organization. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030589treatment-for-all-people-suffering-from-drug-resistant-tb

- Global tuberculosis report 2022. World Health Organization. Published October 27, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment – drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, 2022 update. World Health Organization. Published December 15, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063129

- Migliori GB, Tiberi S. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022 ;26(7):590-591. doi:10.5588/ijtld.22.0263.

- Lange C et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1142-1144. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0393ED

- Esmail A et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1214-1227. doi:10.1164/rccm.202107-1779OC

- WHO BPaLM Accelerator Platform: to support the call to action for implementation of the shorter and more effective treatment for all people suffering from drug-resistant TB. World Health Organization. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/05/09/default-calendar/who-bpalm-accelerator-platform–to-support-the-call-to-action-for-implementation-of-the-shorter-and-moreeffective-

- Trevisi L et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(11):1525-1532. doi:10.1164/rccm.202211-2125OC

- Domínguez J et al; TBnet and RESIST-TB networks. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(4):e122-e137. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00875-1

- WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis: module 3: diagnosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. World Health Organization. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030589treatment-for-all-people-suffering-from-drug-resistant-tb

CPAP adherence curbs severe cardiovascular disease outcomes

, based on data from more than 4,000 individuals.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, but the association between management of OSA with a continuous positive-airway pressure device (CPAP) and major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) remains unclear, wrote Manuel Sánchez-de-la-Torre, PhD, of the University of Lleida, Spain, and colleagues.

In a meta-analysis published in JAMA, the researchers reviewed data from 4,186 individuals with a mean age of 61.2 years; 82.1% were men. The study population included 2,097 patients who used CPAP and 2,089 who did not. The mean apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was 31.2 events per hour, and OSA was defined as an oxygen desaturation index of 12 events or more per hour or an AHI of 15 events or more per hour. The composite primary outcome included the first MACCE, or death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, stroke, revascularization procedure, hospital admission for heart failure, hospital admission for unstable angina, or hospital admission for transient ischemic attack. Each of these components was a secondary endpoint.

Overall, the primary outcome of MACCE was similar for CPAP and non-CPAP using patients (hazard ratio, 1.01) with a total of 349 MACCE events in the CPAP group and 342 in the non-CPAP group. The mean adherence to CPAP was 3.1 hours per day. A total of 38.5% of patients in the CPAP group met the criteria for good adherence, defined as a mean of 4 or more hours per day.

However, as defined, good adherence to CPAP significantly reduced the risk of MACCE, compared with no CPAP use (HR, 0.69), and a sensitivity analysis showed a significant risk reduction, compared with patients who did not meet the criteria for good adherence (HR, 0.55; P = .005).

“Adherence to treatment is complex to determine and there are other potential factors that could affect patient adherence, such as health education, motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, psychosocial factors, and other health care system–related features,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the evaluation only of CPAP as a treatment for OSA, and the inability to assess separate components of the composite endpoint, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the relatively small number of female patients, reliance mainly on at-home sleep apnea tests, and the potential for selection bias, they said.

However, the results suggest that CPAP adherence is important to prevention of secondary cardiovascular outcomes in OSA patients, and that implementation of specific and personalized strategies to improve adherence to treatment should be a clinical priority, they concluded.

The study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the European Union and FEDER, IRBLleida–Fundació Dr Pifarré, SEPAR, ResMed Ltd. (Australia), Associació Lleidatana de Respiratori, and CIBERES. Dr Sánchez-de-la-Torre also disclosed financial support from a Ramón y Cajal grant.

, based on data from more than 4,000 individuals.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, but the association between management of OSA with a continuous positive-airway pressure device (CPAP) and major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) remains unclear, wrote Manuel Sánchez-de-la-Torre, PhD, of the University of Lleida, Spain, and colleagues.

In a meta-analysis published in JAMA, the researchers reviewed data from 4,186 individuals with a mean age of 61.2 years; 82.1% were men. The study population included 2,097 patients who used CPAP and 2,089 who did not. The mean apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was 31.2 events per hour, and OSA was defined as an oxygen desaturation index of 12 events or more per hour or an AHI of 15 events or more per hour. The composite primary outcome included the first MACCE, or death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, stroke, revascularization procedure, hospital admission for heart failure, hospital admission for unstable angina, or hospital admission for transient ischemic attack. Each of these components was a secondary endpoint.

Overall, the primary outcome of MACCE was similar for CPAP and non-CPAP using patients (hazard ratio, 1.01) with a total of 349 MACCE events in the CPAP group and 342 in the non-CPAP group. The mean adherence to CPAP was 3.1 hours per day. A total of 38.5% of patients in the CPAP group met the criteria for good adherence, defined as a mean of 4 or more hours per day.

However, as defined, good adherence to CPAP significantly reduced the risk of MACCE, compared with no CPAP use (HR, 0.69), and a sensitivity analysis showed a significant risk reduction, compared with patients who did not meet the criteria for good adherence (HR, 0.55; P = .005).

“Adherence to treatment is complex to determine and there are other potential factors that could affect patient adherence, such as health education, motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, psychosocial factors, and other health care system–related features,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the evaluation only of CPAP as a treatment for OSA, and the inability to assess separate components of the composite endpoint, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the relatively small number of female patients, reliance mainly on at-home sleep apnea tests, and the potential for selection bias, they said.

However, the results suggest that CPAP adherence is important to prevention of secondary cardiovascular outcomes in OSA patients, and that implementation of specific and personalized strategies to improve adherence to treatment should be a clinical priority, they concluded.

The study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the European Union and FEDER, IRBLleida–Fundació Dr Pifarré, SEPAR, ResMed Ltd. (Australia), Associació Lleidatana de Respiratori, and CIBERES. Dr Sánchez-de-la-Torre also disclosed financial support from a Ramón y Cajal grant.

, based on data from more than 4,000 individuals.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, but the association between management of OSA with a continuous positive-airway pressure device (CPAP) and major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) remains unclear, wrote Manuel Sánchez-de-la-Torre, PhD, of the University of Lleida, Spain, and colleagues.

In a meta-analysis published in JAMA, the researchers reviewed data from 4,186 individuals with a mean age of 61.2 years; 82.1% were men. The study population included 2,097 patients who used CPAP and 2,089 who did not. The mean apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was 31.2 events per hour, and OSA was defined as an oxygen desaturation index of 12 events or more per hour or an AHI of 15 events or more per hour. The composite primary outcome included the first MACCE, or death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, stroke, revascularization procedure, hospital admission for heart failure, hospital admission for unstable angina, or hospital admission for transient ischemic attack. Each of these components was a secondary endpoint.

Overall, the primary outcome of MACCE was similar for CPAP and non-CPAP using patients (hazard ratio, 1.01) with a total of 349 MACCE events in the CPAP group and 342 in the non-CPAP group. The mean adherence to CPAP was 3.1 hours per day. A total of 38.5% of patients in the CPAP group met the criteria for good adherence, defined as a mean of 4 or more hours per day.

However, as defined, good adherence to CPAP significantly reduced the risk of MACCE, compared with no CPAP use (HR, 0.69), and a sensitivity analysis showed a significant risk reduction, compared with patients who did not meet the criteria for good adherence (HR, 0.55; P = .005).

“Adherence to treatment is complex to determine and there are other potential factors that could affect patient adherence, such as health education, motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, psychosocial factors, and other health care system–related features,” the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the evaluation only of CPAP as a treatment for OSA, and the inability to assess separate components of the composite endpoint, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the relatively small number of female patients, reliance mainly on at-home sleep apnea tests, and the potential for selection bias, they said.

However, the results suggest that CPAP adherence is important to prevention of secondary cardiovascular outcomes in OSA patients, and that implementation of specific and personalized strategies to improve adherence to treatment should be a clinical priority, they concluded.

The study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the European Union and FEDER, IRBLleida–Fundació Dr Pifarré, SEPAR, ResMed Ltd. (Australia), Associació Lleidatana de Respiratori, and CIBERES. Dr Sánchez-de-la-Torre also disclosed financial support from a Ramón y Cajal grant.

FROM JAMA

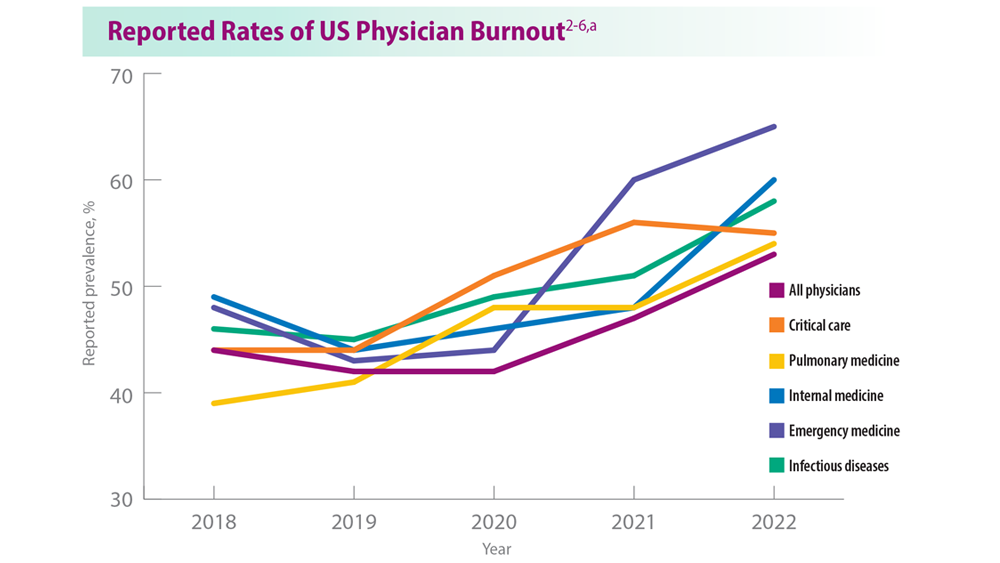

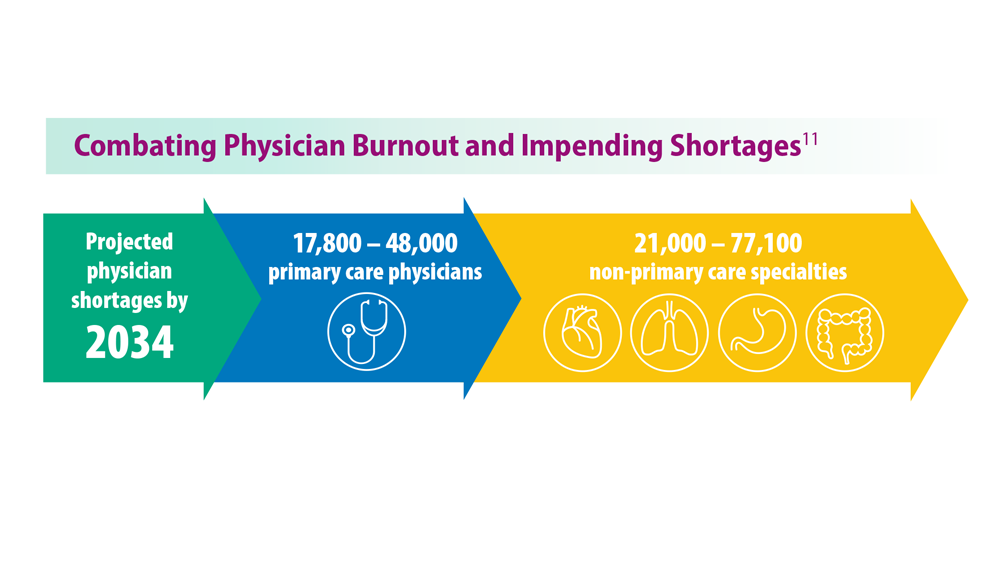

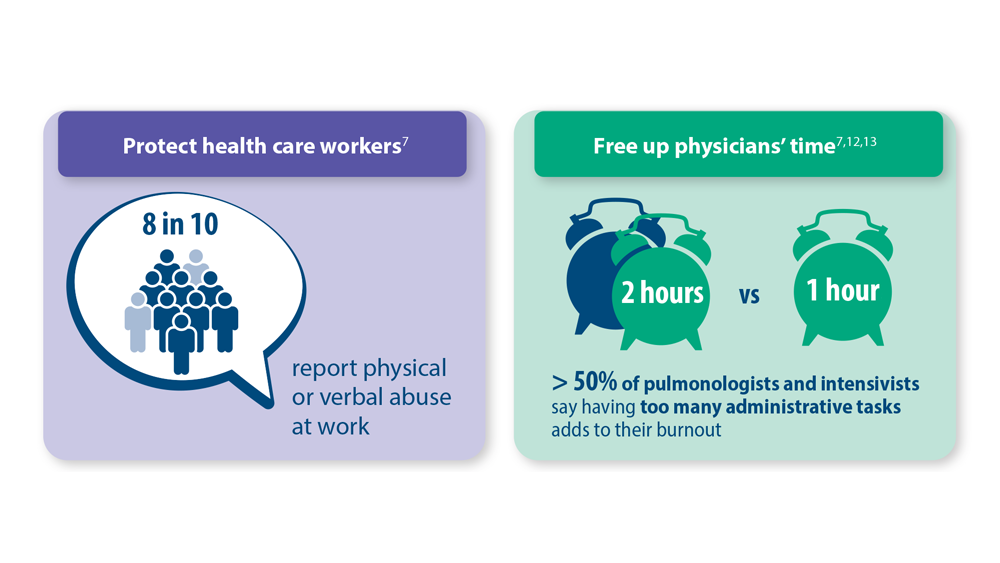

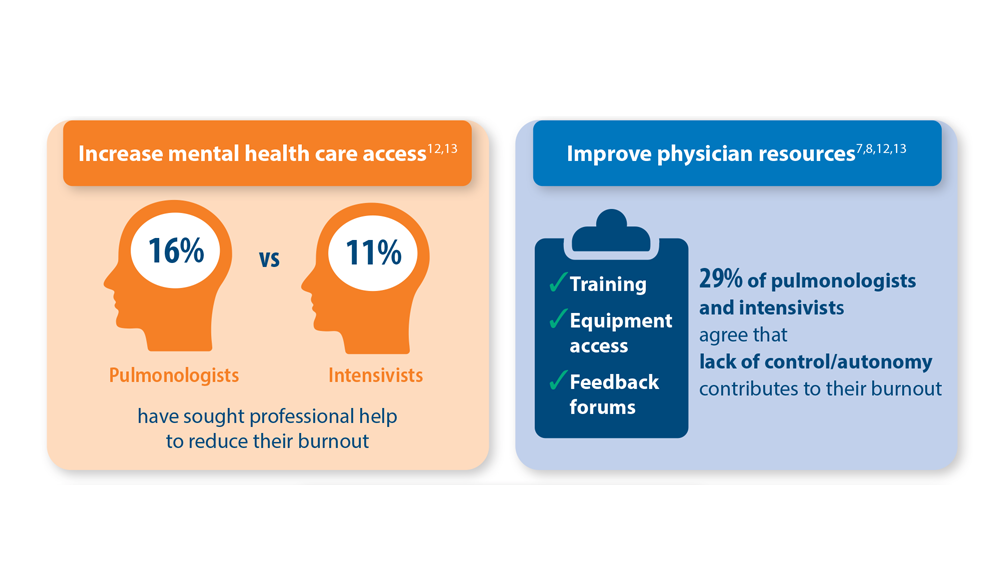

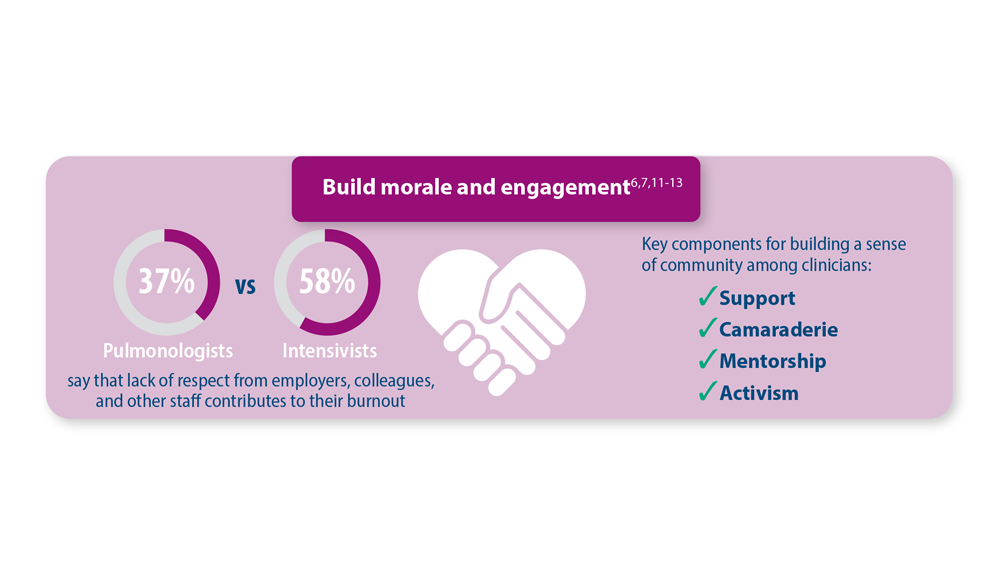

Addressing Physician Burnout in Pulmonology and Critical Care

- Moss M et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1414-1421. doi:10.1097/CCM.000000000000188

- Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape. January 16, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1

- Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide. Medscape. January 15, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460#1

- ‘Death by 1000 Cuts’: Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021. Medscape. January 22, 2021. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456#2

- Physician Burnout Report 2022: Stress, Anxiety, and Anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664#1

- ‘I Cry but No One Cares’: Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023. Medscape. January 27, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-burnout-6016058#1

- Murthy VH. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2207252

- Vranas KC et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):1714-1728. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.041

- Kerlin MP et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(2):329-331. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202105-567RL

- Dean W et al. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402. PMID: 31571807

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. June 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?attachment

- Medscape Pulmonologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-pulmonologist-6016092#1

- Medscape Intensivist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-intensivist-6016072#1

- Moss M et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1414-1421. doi:10.1097/CCM.000000000000188

- Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape. January 16, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1

- Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide. Medscape. January 15, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460#1

- ‘Death by 1000 Cuts’: Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021. Medscape. January 22, 2021. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456#2

- Physician Burnout Report 2022: Stress, Anxiety, and Anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664#1

- ‘I Cry but No One Cares’: Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023. Medscape. January 27, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-burnout-6016058#1

- Murthy VH. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2207252

- Vranas KC et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):1714-1728. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.041

- Kerlin MP et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(2):329-331. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202105-567RL

- Dean W et al. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402. PMID: 31571807

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. June 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?attachment

- Medscape Pulmonologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-pulmonologist-6016092#1

- Medscape Intensivist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-intensivist-6016072#1

- Moss M et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1414-1421. doi:10.1097/CCM.000000000000188

- Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression & Suicide Report 2019. Medscape. January 16, 2019. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1

- Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide. Medscape. January 15, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460#1

- ‘Death by 1000 Cuts’: Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021. Medscape. January 22, 2021. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456#2

- Physician Burnout Report 2022: Stress, Anxiety, and Anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664#1

- ‘I Cry but No One Cares’: Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023. Medscape. January 27, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-burnout-6016058#1

- Murthy VH. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2207252

- Vranas KC et al. Chest. 2021;160(5):1714-1728. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.041

- Kerlin MP et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(2):329-331. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202105-567RL

- Dean W et al. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402. PMID: 31571807

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034. June 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?attachment

- Medscape Pulmonologist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-pulmonologist-6016092#1

- Medscape Intensivist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report 2023: Contentment Amid Stress. February 24, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-intensivist-6016072#1

Reducing cognitive impairment from SCLC brain metastases

For patients with up to 10 brain metastases from small cell lung cancer (SCLC), stereotactic radiosurgery was associated with less cognitive impairment than whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) without compromising overall survival, results of the randomized ENCEPHALON (ARO 2018-9) trial suggest.

Among 56 patients with one to 10 SCLC brain metastases, 24% of those who received WBRT demonstrated significant declines in memory function 3 months after treatment, compared with 7% of patients whose metastases were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery alone. Preliminary data showed no significant differences in overall survival between the treatment groups at 6 months of follow-up, Denise Bernhardt, MD, from the Technical University of Munich, reported at the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting.

“We propose stereotactic radiosurgery should be an option for patients with up to 10 brain metastases in small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Bernhardt said during her presentation.

Vinai Gondi, MD, who was not involved in the study, said that the primary results from the trial – while limited by the study’s small size and missing data – are notable.

Patients with brain metastases from most cancer types typically receive stereotactic radiosurgery but WBRT has remained the standard of care to control brain metastases among patients with SCLC.

“This is the first prospective trial of radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy for small cell lung cancer brain metastases, and it’s important to recognize how important this is,” said Dr. Gondi, director of Radiation Oncology and codirector of the Brain Tumor Center at Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center, Warrenville, Ill.

Prior trials that have asked the same question did not include SCLC because many of those patients received prophylactic cranial irradiation, Dr. Gondi explained. Prophylactic cranial irradiation, however, has been on the decline among patients with brain metastases from SCLC, following a study from Japan showing no difference in survival among those who received the therapy and those followed with observation as well as evidence demonstrating significant toxicities associated with the technique.

Now “with the declining use of prophylactic cranial irradiation, the emergence of brain metastases is increasing significantly in volume in the small cell lung cancer population,” said Dr. Gondi, who is principal investigator on a phase 3 trial exploring stereotactic radiosurgery versus WBRT in a similar patient population.

In a previous retrospective trial), Dr. Bernhardt and colleagues found that first-line stereotactic radiosurgery did not compromise survival, compared with WBRT, but patients receiving stereotactic radiosurgery did have a higher risk for intracranial failure.

In the current study, the investigators compared the neurocognitive responses in patients with brain metastases from SCLC treated with stereotactic radiosurgery or WBRT.

Enrolled patients had histologically confirmed extensive disease with up to 10 metastatic brain lesions and had not previously received either therapeutic or prophylactic brain irradiation. After stratifying patients by synchronous versus metachronous disease, 56 patients were randomly assigned to either WBRT, at a total dose of 30 Gy delivered in 10 fractions, or to stereotactic radiosurgery with 20 Gy, 18 Gy, or fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery with 30 Gy in 5 Gy fractions for lesions larger than 3 cm.

The primary endpoint was neurocognition after radiation therapy as defined by a decline from baseline of at least five points on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) total recall subscale at 3 months. Secondary endpoints included survival outcomes, additional neurocognitive assessments of motor skills, executive function, attention, memory, and processing as well as quality-of-life measures.

The investigators expected a high rate of study dropout and planned their statistical analysis accordingly, using a method for estimating the likely values of missing data based on observed data.

Among 26 patients who eventually underwent stereotactic radiosurgery, 18 did not meet the primary endpoint and 2 (7%) demonstrated declines on the HVLT-R subscale of 5 or more points. Data for the remaining 6 patients were missing.

Among the 25 who underwent WBRT, 13 did not meet the primary endpoint and 6 (24%) demonstrated declines of at least 5 points. Data for 6 of the remaining patients were missing.

Although more patients in the WBRT arm had significant declines in neurocognitive function, the difference between the groups was not significant, due to the high proportion of study dropouts – approximately one-fourth of patients in each arm. But the analysis suggested that the neuroprotective effect of stereotactic radiosurgery was notable, Dr. Bernhardt said.

At 6 months, the team also found no significant difference in the survival probability between the treatment groups (P = .36). The median time to death was 124 days among patients who received stereotactic radiosurgery and 131 days among patients who received WBRT.

Dr. Gondi said the data from ENCEPHALON, while promising, need to be carefully scrutinized because of the small sample sizes and the possibility for unintended bias.

ARO 2018-9 is an investigator-initiated trial funded by Accuray. Dr. Bernhardt disclosed consulting actives, fees, travel expenses, and research funding from Accuray and others. Dr. Gondi disclosed honoraria from UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with up to 10 brain metastases from small cell lung cancer (SCLC), stereotactic radiosurgery was associated with less cognitive impairment than whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) without compromising overall survival, results of the randomized ENCEPHALON (ARO 2018-9) trial suggest.

Among 56 patients with one to 10 SCLC brain metastases, 24% of those who received WBRT demonstrated significant declines in memory function 3 months after treatment, compared with 7% of patients whose metastases were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery alone. Preliminary data showed no significant differences in overall survival between the treatment groups at 6 months of follow-up, Denise Bernhardt, MD, from the Technical University of Munich, reported at the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting.

“We propose stereotactic radiosurgery should be an option for patients with up to 10 brain metastases in small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Bernhardt said during her presentation.

Vinai Gondi, MD, who was not involved in the study, said that the primary results from the trial – while limited by the study’s small size and missing data – are notable.

Patients with brain metastases from most cancer types typically receive stereotactic radiosurgery but WBRT has remained the standard of care to control brain metastases among patients with SCLC.

“This is the first prospective trial of radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy for small cell lung cancer brain metastases, and it’s important to recognize how important this is,” said Dr. Gondi, director of Radiation Oncology and codirector of the Brain Tumor Center at Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center, Warrenville, Ill.

Prior trials that have asked the same question did not include SCLC because many of those patients received prophylactic cranial irradiation, Dr. Gondi explained. Prophylactic cranial irradiation, however, has been on the decline among patients with brain metastases from SCLC, following a study from Japan showing no difference in survival among those who received the therapy and those followed with observation as well as evidence demonstrating significant toxicities associated with the technique.

Now “with the declining use of prophylactic cranial irradiation, the emergence of brain metastases is increasing significantly in volume in the small cell lung cancer population,” said Dr. Gondi, who is principal investigator on a phase 3 trial exploring stereotactic radiosurgery versus WBRT in a similar patient population.

In a previous retrospective trial), Dr. Bernhardt and colleagues found that first-line stereotactic radiosurgery did not compromise survival, compared with WBRT, but patients receiving stereotactic radiosurgery did have a higher risk for intracranial failure.

In the current study, the investigators compared the neurocognitive responses in patients with brain metastases from SCLC treated with stereotactic radiosurgery or WBRT.

Enrolled patients had histologically confirmed extensive disease with up to 10 metastatic brain lesions and had not previously received either therapeutic or prophylactic brain irradiation. After stratifying patients by synchronous versus metachronous disease, 56 patients were randomly assigned to either WBRT, at a total dose of 30 Gy delivered in 10 fractions, or to stereotactic radiosurgery with 20 Gy, 18 Gy, or fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery with 30 Gy in 5 Gy fractions for lesions larger than 3 cm.

The primary endpoint was neurocognition after radiation therapy as defined by a decline from baseline of at least five points on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) total recall subscale at 3 months. Secondary endpoints included survival outcomes, additional neurocognitive assessments of motor skills, executive function, attention, memory, and processing as well as quality-of-life measures.

The investigators expected a high rate of study dropout and planned their statistical analysis accordingly, using a method for estimating the likely values of missing data based on observed data.

Among 26 patients who eventually underwent stereotactic radiosurgery, 18 did not meet the primary endpoint and 2 (7%) demonstrated declines on the HVLT-R subscale of 5 or more points. Data for the remaining 6 patients were missing.

Among the 25 who underwent WBRT, 13 did not meet the primary endpoint and 6 (24%) demonstrated declines of at least 5 points. Data for 6 of the remaining patients were missing.

Although more patients in the WBRT arm had significant declines in neurocognitive function, the difference between the groups was not significant, due to the high proportion of study dropouts – approximately one-fourth of patients in each arm. But the analysis suggested that the neuroprotective effect of stereotactic radiosurgery was notable, Dr. Bernhardt said.

At 6 months, the team also found no significant difference in the survival probability between the treatment groups (P = .36). The median time to death was 124 days among patients who received stereotactic radiosurgery and 131 days among patients who received WBRT.

Dr. Gondi said the data from ENCEPHALON, while promising, need to be carefully scrutinized because of the small sample sizes and the possibility for unintended bias.

ARO 2018-9 is an investigator-initiated trial funded by Accuray. Dr. Bernhardt disclosed consulting actives, fees, travel expenses, and research funding from Accuray and others. Dr. Gondi disclosed honoraria from UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with up to 10 brain metastases from small cell lung cancer (SCLC), stereotactic radiosurgery was associated with less cognitive impairment than whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) without compromising overall survival, results of the randomized ENCEPHALON (ARO 2018-9) trial suggest.

Among 56 patients with one to 10 SCLC brain metastases, 24% of those who received WBRT demonstrated significant declines in memory function 3 months after treatment, compared with 7% of patients whose metastases were treated with stereotactic radiosurgery alone. Preliminary data showed no significant differences in overall survival between the treatment groups at 6 months of follow-up, Denise Bernhardt, MD, from the Technical University of Munich, reported at the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting.

“We propose stereotactic radiosurgery should be an option for patients with up to 10 brain metastases in small cell lung cancer,” Dr. Bernhardt said during her presentation.

Vinai Gondi, MD, who was not involved in the study, said that the primary results from the trial – while limited by the study’s small size and missing data – are notable.

Patients with brain metastases from most cancer types typically receive stereotactic radiosurgery but WBRT has remained the standard of care to control brain metastases among patients with SCLC.

“This is the first prospective trial of radiosurgery versus whole-brain radiotherapy for small cell lung cancer brain metastases, and it’s important to recognize how important this is,” said Dr. Gondi, director of Radiation Oncology and codirector of the Brain Tumor Center at Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center, Warrenville, Ill.

Prior trials that have asked the same question did not include SCLC because many of those patients received prophylactic cranial irradiation, Dr. Gondi explained. Prophylactic cranial irradiation, however, has been on the decline among patients with brain metastases from SCLC, following a study from Japan showing no difference in survival among those who received the therapy and those followed with observation as well as evidence demonstrating significant toxicities associated with the technique.

Now “with the declining use of prophylactic cranial irradiation, the emergence of brain metastases is increasing significantly in volume in the small cell lung cancer population,” said Dr. Gondi, who is principal investigator on a phase 3 trial exploring stereotactic radiosurgery versus WBRT in a similar patient population.

In a previous retrospective trial), Dr. Bernhardt and colleagues found that first-line stereotactic radiosurgery did not compromise survival, compared with WBRT, but patients receiving stereotactic radiosurgery did have a higher risk for intracranial failure.

In the current study, the investigators compared the neurocognitive responses in patients with brain metastases from SCLC treated with stereotactic radiosurgery or WBRT.

Enrolled patients had histologically confirmed extensive disease with up to 10 metastatic brain lesions and had not previously received either therapeutic or prophylactic brain irradiation. After stratifying patients by synchronous versus metachronous disease, 56 patients were randomly assigned to either WBRT, at a total dose of 30 Gy delivered in 10 fractions, or to stereotactic radiosurgery with 20 Gy, 18 Gy, or fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery with 30 Gy in 5 Gy fractions for lesions larger than 3 cm.

The primary endpoint was neurocognition after radiation therapy as defined by a decline from baseline of at least five points on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R) total recall subscale at 3 months. Secondary endpoints included survival outcomes, additional neurocognitive assessments of motor skills, executive function, attention, memory, and processing as well as quality-of-life measures.

The investigators expected a high rate of study dropout and planned their statistical analysis accordingly, using a method for estimating the likely values of missing data based on observed data.

Among 26 patients who eventually underwent stereotactic radiosurgery, 18 did not meet the primary endpoint and 2 (7%) demonstrated declines on the HVLT-R subscale of 5 or more points. Data for the remaining 6 patients were missing.

Among the 25 who underwent WBRT, 13 did not meet the primary endpoint and 6 (24%) demonstrated declines of at least 5 points. Data for 6 of the remaining patients were missing.

Although more patients in the WBRT arm had significant declines in neurocognitive function, the difference between the groups was not significant, due to the high proportion of study dropouts – approximately one-fourth of patients in each arm. But the analysis suggested that the neuroprotective effect of stereotactic radiosurgery was notable, Dr. Bernhardt said.

At 6 months, the team also found no significant difference in the survival probability between the treatment groups (P = .36). The median time to death was 124 days among patients who received stereotactic radiosurgery and 131 days among patients who received WBRT.

Dr. Gondi said the data from ENCEPHALON, while promising, need to be carefully scrutinized because of the small sample sizes and the possibility for unintended bias.

ARO 2018-9 is an investigator-initiated trial funded by Accuray. Dr. Bernhardt disclosed consulting actives, fees, travel expenses, and research funding from Accuray and others. Dr. Gondi disclosed honoraria from UpToDate.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Hormone therapy less effective in menopausal women with obesity

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a small, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

More than 40% of women over age 40 in the United States have obesity, presenter Anita Pershad, MD, an ob.gyn. medical resident at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, told attendees. Yet most of the large-scale studies investigating perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormone therapy included participants without major medical comorbidities, so little data exist on how effectively HT works in women with these comorbidities, she said

“The main takeaway of our study is that obesity may worsen a woman’s menopausal symptoms and limit the amount of relief she gets from hormone therapy,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “It remains unclear if hormone therapy is less effective in women with obesity overall, or if the expected efficacy can be achieved with alternative design and administration routes. A potential mechanism of action for the observed decreased effect could be due to adipose tissue acting as a heat insulator, promoting the effects of vasomotor symptoms.”

Dr. Pershad and her colleagues conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of 119 patients who presented to a menopause clinic at a Midsouth urban academic medical center between July 2018 and December 2022. Obesity was defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The patients with and without obesity were similar in terms of age, duration of menopause, use of hormone therapy, and therapy acceptance, but patients with obesity were more likely to identify themselves as Black (71% vs. 40%). Women with obesity were also significantly more likely than women without obesity to report vasomotor symptoms (74% vs. 45%, P = .002), genitourinary/vulvovaginal symptoms (60% vs. 21%, P < .001), mood disturbances (11% vs. 0%, P = .18), and decreased libido (29% vs. 11%, P = .017).

There were no significant differences in comorbidities between women with and without obesity, and among women who received systemic or localized HT, the same standard dosing was used for both groups.

Women with obesity were much less likely to see a satisfying reduction in their menopausal symptoms than women without obesity (odds ratio 0.07, 95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.64; P = .006), though the subgroups for each category of HT were small. Among the 20 women receiving systemic hormone therapy, only 1 of the 12 with obesity (8.3%) reported improvement in symptoms, compared with 7 of the 8 women without obesity (88%; P = .0004). Among 33 women using localized hormone therapy, 46% of the 24 women with obesity vs. 89% of the 9 women without obesity experienced symptom improvement (P = .026).

The proportions of women reporting relief from only lifestyle modifications or from nonhormonal medications, such as SSRIs/SNRIs, trazodone, and clonidine, were not statistically different. There were 33 women who relied only on lifestyle modifications, with 31% of the 16 women with obesity and 59% of the 17 women without obesity reporting improvement in their symptoms (P = .112). Similarly, among the 33 women using nonhormonal medications, 75% of the 20 women with obesity and 77% of the 13 women without obesity experienced relief (P = .9).

Women with obesity are undertreated

Dr. Pershad emphasized the need to improve care and counseling for diverse patients seeking treatment for menopausal symptoms.

“More research is needed to examine how women with medical comorbidities are uniquely impacted by menopause and respond to therapies,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “This can be achieved by actively including more diverse patient populations in women’s health studies, burdened by the social determinants of health and medical comorbidities such as obesity.”

Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health, Rochester, Minn., and medical director for The Menopause Society, was not surprised by the findings, particularly given that women with obesity tend to have more hot flashes and night sweats as a result of their extra weight. However, dosage data was not adjusted for BMI in the study and data on hormone levels was unavailable, she said, so it’s difficult to determine from the data whether HT was less effective for women with obesity or whether they were underdosed.

“I think women with obesity are undertreated,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. “My guess is people are afraid. Women with obesity also may have other comorbidities,” such as hypertension and diabetes, she said, and “the greater the number of cardiovascular risk factors, the higher risk hormone therapy is.” Providers may therefore be leery of prescribing HT or prescribing it at an appropriately high enough dose to treat menopausal symptoms.

Common practice is to start patients at the lowest dose and titrate up according to symptoms, but “if people are afraid of it, they’re going to start the lowest dose” and may not increase it, Dr. Faubion said. She noted that other nonhormonal options are available, though providers should be conscientious about selecting ones whose adverse events do not include weight gain.

Although the study focused on an understudied population within hormone therapy research, the study was limited by its small size, low overall use of hormone therapy, recall bias, and the researchers’ inability to control for other medications the participants may have been taking.

Dr. Pershad said she is continuing research to try to identify the mechanisms underlying the reduced efficacy in women with obesity.

The research did not use any external funding. Dr. Pershad had no industry disclosures, but her colleagues reported honoraria from or speaking for TherapeuticsMD, Astella Pharma, Scynexis, Pharmavite, and Pfizer. Dr. Faubion had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a small, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

More than 40% of women over age 40 in the United States have obesity, presenter Anita Pershad, MD, an ob.gyn. medical resident at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, told attendees. Yet most of the large-scale studies investigating perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormone therapy included participants without major medical comorbidities, so little data exist on how effectively HT works in women with these comorbidities, she said

“The main takeaway of our study is that obesity may worsen a woman’s menopausal symptoms and limit the amount of relief she gets from hormone therapy,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “It remains unclear if hormone therapy is less effective in women with obesity overall, or if the expected efficacy can be achieved with alternative design and administration routes. A potential mechanism of action for the observed decreased effect could be due to adipose tissue acting as a heat insulator, promoting the effects of vasomotor symptoms.”

Dr. Pershad and her colleagues conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of 119 patients who presented to a menopause clinic at a Midsouth urban academic medical center between July 2018 and December 2022. Obesity was defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The patients with and without obesity were similar in terms of age, duration of menopause, use of hormone therapy, and therapy acceptance, but patients with obesity were more likely to identify themselves as Black (71% vs. 40%). Women with obesity were also significantly more likely than women without obesity to report vasomotor symptoms (74% vs. 45%, P = .002), genitourinary/vulvovaginal symptoms (60% vs. 21%, P < .001), mood disturbances (11% vs. 0%, P = .18), and decreased libido (29% vs. 11%, P = .017).

There were no significant differences in comorbidities between women with and without obesity, and among women who received systemic or localized HT, the same standard dosing was used for both groups.

Women with obesity were much less likely to see a satisfying reduction in their menopausal symptoms than women without obesity (odds ratio 0.07, 95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.64; P = .006), though the subgroups for each category of HT were small. Among the 20 women receiving systemic hormone therapy, only 1 of the 12 with obesity (8.3%) reported improvement in symptoms, compared with 7 of the 8 women without obesity (88%; P = .0004). Among 33 women using localized hormone therapy, 46% of the 24 women with obesity vs. 89% of the 9 women without obesity experienced symptom improvement (P = .026).

The proportions of women reporting relief from only lifestyle modifications or from nonhormonal medications, such as SSRIs/SNRIs, trazodone, and clonidine, were not statistically different. There were 33 women who relied only on lifestyle modifications, with 31% of the 16 women with obesity and 59% of the 17 women without obesity reporting improvement in their symptoms (P = .112). Similarly, among the 33 women using nonhormonal medications, 75% of the 20 women with obesity and 77% of the 13 women without obesity experienced relief (P = .9).

Women with obesity are undertreated

Dr. Pershad emphasized the need to improve care and counseling for diverse patients seeking treatment for menopausal symptoms.

“More research is needed to examine how women with medical comorbidities are uniquely impacted by menopause and respond to therapies,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “This can be achieved by actively including more diverse patient populations in women’s health studies, burdened by the social determinants of health and medical comorbidities such as obesity.”

Stephanie S. Faubion, MD, MBA, director for Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health, Rochester, Minn., and medical director for The Menopause Society, was not surprised by the findings, particularly given that women with obesity tend to have more hot flashes and night sweats as a result of their extra weight. However, dosage data was not adjusted for BMI in the study and data on hormone levels was unavailable, she said, so it’s difficult to determine from the data whether HT was less effective for women with obesity or whether they were underdosed.

“I think women with obesity are undertreated,” Dr. Faubion said in an interview. “My guess is people are afraid. Women with obesity also may have other comorbidities,” such as hypertension and diabetes, she said, and “the greater the number of cardiovascular risk factors, the higher risk hormone therapy is.” Providers may therefore be leery of prescribing HT or prescribing it at an appropriately high enough dose to treat menopausal symptoms.

Common practice is to start patients at the lowest dose and titrate up according to symptoms, but “if people are afraid of it, they’re going to start the lowest dose” and may not increase it, Dr. Faubion said. She noted that other nonhormonal options are available, though providers should be conscientious about selecting ones whose adverse events do not include weight gain.

Although the study focused on an understudied population within hormone therapy research, the study was limited by its small size, low overall use of hormone therapy, recall bias, and the researchers’ inability to control for other medications the participants may have been taking.

Dr. Pershad said she is continuing research to try to identify the mechanisms underlying the reduced efficacy in women with obesity.

The research did not use any external funding. Dr. Pershad had no industry disclosures, but her colleagues reported honoraria from or speaking for TherapeuticsMD, Astella Pharma, Scynexis, Pharmavite, and Pfizer. Dr. Faubion had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to a small, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the Menopause Society (formerly the North American Menopause Society).

More than 40% of women over age 40 in the United States have obesity, presenter Anita Pershad, MD, an ob.gyn. medical resident at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, told attendees. Yet most of the large-scale studies investigating perimenopausal and postmenopausal hormone therapy included participants without major medical comorbidities, so little data exist on how effectively HT works in women with these comorbidities, she said

“The main takeaway of our study is that obesity may worsen a woman’s menopausal symptoms and limit the amount of relief she gets from hormone therapy,” Dr. Pershad said in an interview. “It remains unclear if hormone therapy is less effective in women with obesity overall, or if the expected efficacy can be achieved with alternative design and administration routes. A potential mechanism of action for the observed decreased effect could be due to adipose tissue acting as a heat insulator, promoting the effects of vasomotor symptoms.”

Dr. Pershad and her colleagues conducted a retrospective review of the medical records of 119 patients who presented to a menopause clinic at a Midsouth urban academic medical center between July 2018 and December 2022. Obesity was defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater.

The patients with and without obesity were similar in terms of age, duration of menopause, use of hormone therapy, and therapy acceptance, but patients with obesity were more likely to identify themselves as Black (71% vs. 40%). Women with obesity were also significantly more likely than women without obesity to report vasomotor symptoms (74% vs. 45%, P = .002), genitourinary/vulvovaginal symptoms (60% vs. 21%, P < .001), mood disturbances (11% vs. 0%, P = .18), and decreased libido (29% vs. 11%, P = .017).

There were no significant differences in comorbidities between women with and without obesity, and among women who received systemic or localized HT, the same standard dosing was used for both groups.

Women with obesity were much less likely to see a satisfying reduction in their menopausal symptoms than women without obesity (odds ratio 0.07, 95% confidence interval, 0.01-0.64; P = .006), though the subgroups for each category of HT were small. Among the 20 women receiving systemic hormone therapy, only 1 of the 12 with obesity (8.3%) reported improvement in symptoms, compared with 7 of the 8 women without obesity (88%; P = .0004). Among 33 women using localized hormone therapy, 46% of the 24 women with obesity vs. 89% of the 9 women without obesity experienced symptom improvement (P = .026).