User login

There are new things we can do to improve early autism detection

We are all seeing more children on the autism spectrum than we ever expected. With a Centers for Disease Control–estimated prevalence of 1 in 44, the average pediatrician will be caring for 45 children with autism. It may feel like even more as parents bring in their children with related concerns or fears. Early entry into services has been shown to improve functioning, making early identification important. However, screening at the youngest ages has important limitations.

Sharing a concern about possible autism with parents is a painful aspect of primary care practice. We want to get it right, not frighten parents unnecessarily, nor miss children and delay intervention.

Autism screening is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics at 18- and 24-month pediatric well-child visits. There are several reasons for screening repeatedly: Autism symptoms emerge gradually in the toddler period; about 32% of children later found to have autism were developing in a typical pattern and appeared normal at 18 months only to regress by age 24 months; children may miss the 18 month screen; and all screens have false negatives as well as false positives. But even screening at these two ages is not enough.

One criticism of current screening tests pointed out by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has been a problem with the sample used to develop or validate the tool. Many test development studies included only children at risk by being in early intervention, siblings of children with diagnosed autism, or children only failing the screening tests rather than a community sample that the screen in actually used for.

Another obstacle to prediction of autism diagnoses made years later is that some children may not have had any clinical manifestations at the younger age even as judged by the best gold standard testing and, thus, negative screens were ambiguous. Additionally, data from prospective studies of high-risk infant siblings reveal that only 18% of children diagnosed with autism at 36 months were given that diagnosis at 18 months of age despite use of comprehensive diagnostic assessments.

Prevalence is also reported as 30% higher at age 8-12 years as at 3-7 years on gold-standard tests. Children identified later with autism tend to have milder symptoms and higher cognitive functioning. Therefore, we need some humility in thinking we can identify children as early as 18 months; rather, we need to use the best available methods at all ages and remain vigilant to symptoms as they evolve as well as to new screening and testing measures.

The most commonly used parent report screen is the 20-item Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers–Revised (M-CHAT-R), a modification of the original CHAT screen. To have reasonable positive predictive value, the M-CHAT-R authors recommend a clinician or trained staff member conduct a structured follow-up interview with the parent when the M-CHAT-R has a score of 3-7. Scores of 8 or more reflect enough symptoms to more strongly predict an autism diagnosis and thus the interview may be skipped in those cases. The recommended two-step process is called M-CHAT-R/F. At 18 months without the R/F, a positive M-CHAT-R only is associated with an autism diagnosis 27% of the time (PPV, 0.27); which is unacceptable for primary care use.

Unfortunately, the M-CHAT-R/F appears to be less accurate for 18-month-olds than 24-month-olds, in part because its yes/no response options are harder for a caregiver to answer, especially for behaviors just developing, or because of lack of experience with toddlers.

An alternative modification of the original CHAT called the Quantitative CHAT or Q-CHAT-10 has a range of response options for the caregiver; for example, always/usually/sometimes/rarely/never or many times a day/a few times a day/a few times a week/less than once a week/never. The authors of the Q-CHAT-10, however, recommend a summary pass/fail result for ease of use rather than using the range of response option values in the score. We recently published a study testing accuracy using add-up scoring that utilized the entire range of response option values, called Q-CHAT-10-O (O for ordinal), for children 16-20 months old as well as cartoon depictions of the behaviors. Our study also included diagnostic testing of screen-negative as well as screen-positive children to accurately calculate sensitivity and specificity for this method. In our study, Q-CHAT-10-O with a cutoff score greater than 11 showed higher sensitivity (0.63) than either M-CHAT-R/F (0.34) or Q-CHAT-10 (0.31) for this age range although the PPV (0.35) and negative predictive value (0.92) were comparable with M-CHAT R/F. Although Q-CHAT-10-O sensitivity (0.63) is less than M-CHAT-R (without follow-up; 0.73) and specificity (0.79) is less than the two-stage R/F procedure (0.90), on balance, it is more accurate and more practical for a primary care population. After 20 months of age, the M-CHAT-R/F has adequate accuracy to rescreen, if indicated, and for the subsequent 24 month screening. Language items are often of highest value in predicting outcomes in several tools including in the screen we are now validating for 18 month olds.

The Q-CHAT-10-O with ordinal scoring and pictures can also be recommended because it shows advantages over M-CHAT-R/F with half the number of items (10 vs. 20), no requirement for a follow-up interview, and improved sensitivity. Unlike M-CHAT-R, it also contributes to equity in screening because results did not differ depending on race or socioeconomic background.

Is there an even better way to detect autism in primary care? In 2022 an article was published regarding an exciting method of early autism detection called the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised (SACS-R), an eight-item observation checklist completed at public health nurse check-ups in Australia. The observers had 4 years of nursing degree education and a 3.5-hour training session.

The SACS-R and the preschool version (for older children) had significant associations with diagnostic testing at 12, 18, 24, and 42 months. The SACS-R had excellent PPV (82.6%), NPV (98.7%), and specificity (99.6%) and moderate sensitivity (61.5%) when used between 12 and 24 months of age. Pointing, eye contact, waving “bye, bye,” social communication by showing, and pretend play were the key indicators for observations at 18 months, with absence of three or more indicating risk for autism. Different key indicators were used at the other ages, reflecting the evolution of autism symptoms. This hybrid (observation and scoring) surveillance method by professionals shows hopeful data for the critical ability to identify children at risk for autism in primary care very early but requires more than parent report, that is, new levels of autism-specific clinician training and direct observations at multiple visits over time.

The takeaway is to remember that we should all watch closely for early signs of autism, informed by research on the key findings that a professional might observe, as well as by using the best screens available. We should remember that both false positives and false negatives are inherent in screening, especially at the youngest ages. We need to combine our concern with the parent’s concern as well as screen results and be sure to follow-up closely as symptoms can change in even a few months. Many factors may prevent a family from returning to see us or following our advice to go for testing or intervention, so tracking the child and their service use is an important part of the good care we strive to provide children with autism.

Other screening tools

You may have heard of other parent-report screens for autism. It is important to compare their accuracy specifically for 18-month-olds in a community setting.

- The Infant Toddler Checklist (https://psychology-tools.com/test/infant-toddler-checklist) has moderate overall psychometrics with sensitivity ranging from 0.55 to 0.77; specificity from 0.42 to 0.85; PPV from 0.20 to 0.55; and NPV from 0.83 to 0.94. However, the data were based on a sample including both community-dwelling toddlers and those with a family history of autism.

- The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/brief-infant-toddler-social-emotional-assessment/) – the screen’s four autism-specific scales had high specificity (84%-90%) but low sensitivity (40%-52%).

- Canvas Dx (https://canvasdx.com/) from the Cognoa company is not a parent-report measure but rather a three-part evaluation including an app-based parent questionnaire, parent uploads of home videos analyzed by a specialist, and a 13- to 15-item primary care physician observational checklist. There were 56 diagnosed of the 426 children in the 18- to 24-month-old range from a sample of children presenting with parent or clinician concerns rather than from a community sample.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

References

Sturner R et al. Autism screening at 18 months of age: A comparison of the Q-CHAT-10 and M-CHAT screeners. Molecular Autism. Jan 3;13(1):2.

Barbaro J et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised with preschool tool for early autism detection in very young children. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e2146415.

We are all seeing more children on the autism spectrum than we ever expected. With a Centers for Disease Control–estimated prevalence of 1 in 44, the average pediatrician will be caring for 45 children with autism. It may feel like even more as parents bring in their children with related concerns or fears. Early entry into services has been shown to improve functioning, making early identification important. However, screening at the youngest ages has important limitations.

Sharing a concern about possible autism with parents is a painful aspect of primary care practice. We want to get it right, not frighten parents unnecessarily, nor miss children and delay intervention.

Autism screening is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics at 18- and 24-month pediatric well-child visits. There are several reasons for screening repeatedly: Autism symptoms emerge gradually in the toddler period; about 32% of children later found to have autism were developing in a typical pattern and appeared normal at 18 months only to regress by age 24 months; children may miss the 18 month screen; and all screens have false negatives as well as false positives. But even screening at these two ages is not enough.

One criticism of current screening tests pointed out by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has been a problem with the sample used to develop or validate the tool. Many test development studies included only children at risk by being in early intervention, siblings of children with diagnosed autism, or children only failing the screening tests rather than a community sample that the screen in actually used for.

Another obstacle to prediction of autism diagnoses made years later is that some children may not have had any clinical manifestations at the younger age even as judged by the best gold standard testing and, thus, negative screens were ambiguous. Additionally, data from prospective studies of high-risk infant siblings reveal that only 18% of children diagnosed with autism at 36 months were given that diagnosis at 18 months of age despite use of comprehensive diagnostic assessments.

Prevalence is also reported as 30% higher at age 8-12 years as at 3-7 years on gold-standard tests. Children identified later with autism tend to have milder symptoms and higher cognitive functioning. Therefore, we need some humility in thinking we can identify children as early as 18 months; rather, we need to use the best available methods at all ages and remain vigilant to symptoms as they evolve as well as to new screening and testing measures.

The most commonly used parent report screen is the 20-item Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers–Revised (M-CHAT-R), a modification of the original CHAT screen. To have reasonable positive predictive value, the M-CHAT-R authors recommend a clinician or trained staff member conduct a structured follow-up interview with the parent when the M-CHAT-R has a score of 3-7. Scores of 8 or more reflect enough symptoms to more strongly predict an autism diagnosis and thus the interview may be skipped in those cases. The recommended two-step process is called M-CHAT-R/F. At 18 months without the R/F, a positive M-CHAT-R only is associated with an autism diagnosis 27% of the time (PPV, 0.27); which is unacceptable for primary care use.

Unfortunately, the M-CHAT-R/F appears to be less accurate for 18-month-olds than 24-month-olds, in part because its yes/no response options are harder for a caregiver to answer, especially for behaviors just developing, or because of lack of experience with toddlers.

An alternative modification of the original CHAT called the Quantitative CHAT or Q-CHAT-10 has a range of response options for the caregiver; for example, always/usually/sometimes/rarely/never or many times a day/a few times a day/a few times a week/less than once a week/never. The authors of the Q-CHAT-10, however, recommend a summary pass/fail result for ease of use rather than using the range of response option values in the score. We recently published a study testing accuracy using add-up scoring that utilized the entire range of response option values, called Q-CHAT-10-O (O for ordinal), for children 16-20 months old as well as cartoon depictions of the behaviors. Our study also included diagnostic testing of screen-negative as well as screen-positive children to accurately calculate sensitivity and specificity for this method. In our study, Q-CHAT-10-O with a cutoff score greater than 11 showed higher sensitivity (0.63) than either M-CHAT-R/F (0.34) or Q-CHAT-10 (0.31) for this age range although the PPV (0.35) and negative predictive value (0.92) were comparable with M-CHAT R/F. Although Q-CHAT-10-O sensitivity (0.63) is less than M-CHAT-R (without follow-up; 0.73) and specificity (0.79) is less than the two-stage R/F procedure (0.90), on balance, it is more accurate and more practical for a primary care population. After 20 months of age, the M-CHAT-R/F has adequate accuracy to rescreen, if indicated, and for the subsequent 24 month screening. Language items are often of highest value in predicting outcomes in several tools including in the screen we are now validating for 18 month olds.

The Q-CHAT-10-O with ordinal scoring and pictures can also be recommended because it shows advantages over M-CHAT-R/F with half the number of items (10 vs. 20), no requirement for a follow-up interview, and improved sensitivity. Unlike M-CHAT-R, it also contributes to equity in screening because results did not differ depending on race or socioeconomic background.

Is there an even better way to detect autism in primary care? In 2022 an article was published regarding an exciting method of early autism detection called the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised (SACS-R), an eight-item observation checklist completed at public health nurse check-ups in Australia. The observers had 4 years of nursing degree education and a 3.5-hour training session.

The SACS-R and the preschool version (for older children) had significant associations with diagnostic testing at 12, 18, 24, and 42 months. The SACS-R had excellent PPV (82.6%), NPV (98.7%), and specificity (99.6%) and moderate sensitivity (61.5%) when used between 12 and 24 months of age. Pointing, eye contact, waving “bye, bye,” social communication by showing, and pretend play were the key indicators for observations at 18 months, with absence of three or more indicating risk for autism. Different key indicators were used at the other ages, reflecting the evolution of autism symptoms. This hybrid (observation and scoring) surveillance method by professionals shows hopeful data for the critical ability to identify children at risk for autism in primary care very early but requires more than parent report, that is, new levels of autism-specific clinician training and direct observations at multiple visits over time.

The takeaway is to remember that we should all watch closely for early signs of autism, informed by research on the key findings that a professional might observe, as well as by using the best screens available. We should remember that both false positives and false negatives are inherent in screening, especially at the youngest ages. We need to combine our concern with the parent’s concern as well as screen results and be sure to follow-up closely as symptoms can change in even a few months. Many factors may prevent a family from returning to see us or following our advice to go for testing or intervention, so tracking the child and their service use is an important part of the good care we strive to provide children with autism.

Other screening tools

You may have heard of other parent-report screens for autism. It is important to compare their accuracy specifically for 18-month-olds in a community setting.

- The Infant Toddler Checklist (https://psychology-tools.com/test/infant-toddler-checklist) has moderate overall psychometrics with sensitivity ranging from 0.55 to 0.77; specificity from 0.42 to 0.85; PPV from 0.20 to 0.55; and NPV from 0.83 to 0.94. However, the data were based on a sample including both community-dwelling toddlers and those with a family history of autism.

- The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/brief-infant-toddler-social-emotional-assessment/) – the screen’s four autism-specific scales had high specificity (84%-90%) but low sensitivity (40%-52%).

- Canvas Dx (https://canvasdx.com/) from the Cognoa company is not a parent-report measure but rather a three-part evaluation including an app-based parent questionnaire, parent uploads of home videos analyzed by a specialist, and a 13- to 15-item primary care physician observational checklist. There were 56 diagnosed of the 426 children in the 18- to 24-month-old range from a sample of children presenting with parent or clinician concerns rather than from a community sample.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

References

Sturner R et al. Autism screening at 18 months of age: A comparison of the Q-CHAT-10 and M-CHAT screeners. Molecular Autism. Jan 3;13(1):2.

Barbaro J et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised with preschool tool for early autism detection in very young children. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e2146415.

We are all seeing more children on the autism spectrum than we ever expected. With a Centers for Disease Control–estimated prevalence of 1 in 44, the average pediatrician will be caring for 45 children with autism. It may feel like even more as parents bring in their children with related concerns or fears. Early entry into services has been shown to improve functioning, making early identification important. However, screening at the youngest ages has important limitations.

Sharing a concern about possible autism with parents is a painful aspect of primary care practice. We want to get it right, not frighten parents unnecessarily, nor miss children and delay intervention.

Autism screening is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics at 18- and 24-month pediatric well-child visits. There are several reasons for screening repeatedly: Autism symptoms emerge gradually in the toddler period; about 32% of children later found to have autism were developing in a typical pattern and appeared normal at 18 months only to regress by age 24 months; children may miss the 18 month screen; and all screens have false negatives as well as false positives. But even screening at these two ages is not enough.

One criticism of current screening tests pointed out by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has been a problem with the sample used to develop or validate the tool. Many test development studies included only children at risk by being in early intervention, siblings of children with diagnosed autism, or children only failing the screening tests rather than a community sample that the screen in actually used for.

Another obstacle to prediction of autism diagnoses made years later is that some children may not have had any clinical manifestations at the younger age even as judged by the best gold standard testing and, thus, negative screens were ambiguous. Additionally, data from prospective studies of high-risk infant siblings reveal that only 18% of children diagnosed with autism at 36 months were given that diagnosis at 18 months of age despite use of comprehensive diagnostic assessments.

Prevalence is also reported as 30% higher at age 8-12 years as at 3-7 years on gold-standard tests. Children identified later with autism tend to have milder symptoms and higher cognitive functioning. Therefore, we need some humility in thinking we can identify children as early as 18 months; rather, we need to use the best available methods at all ages and remain vigilant to symptoms as they evolve as well as to new screening and testing measures.

The most commonly used parent report screen is the 20-item Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers–Revised (M-CHAT-R), a modification of the original CHAT screen. To have reasonable positive predictive value, the M-CHAT-R authors recommend a clinician or trained staff member conduct a structured follow-up interview with the parent when the M-CHAT-R has a score of 3-7. Scores of 8 or more reflect enough symptoms to more strongly predict an autism diagnosis and thus the interview may be skipped in those cases. The recommended two-step process is called M-CHAT-R/F. At 18 months without the R/F, a positive M-CHAT-R only is associated with an autism diagnosis 27% of the time (PPV, 0.27); which is unacceptable for primary care use.

Unfortunately, the M-CHAT-R/F appears to be less accurate for 18-month-olds than 24-month-olds, in part because its yes/no response options are harder for a caregiver to answer, especially for behaviors just developing, or because of lack of experience with toddlers.

An alternative modification of the original CHAT called the Quantitative CHAT or Q-CHAT-10 has a range of response options for the caregiver; for example, always/usually/sometimes/rarely/never or many times a day/a few times a day/a few times a week/less than once a week/never. The authors of the Q-CHAT-10, however, recommend a summary pass/fail result for ease of use rather than using the range of response option values in the score. We recently published a study testing accuracy using add-up scoring that utilized the entire range of response option values, called Q-CHAT-10-O (O for ordinal), for children 16-20 months old as well as cartoon depictions of the behaviors. Our study also included diagnostic testing of screen-negative as well as screen-positive children to accurately calculate sensitivity and specificity for this method. In our study, Q-CHAT-10-O with a cutoff score greater than 11 showed higher sensitivity (0.63) than either M-CHAT-R/F (0.34) or Q-CHAT-10 (0.31) for this age range although the PPV (0.35) and negative predictive value (0.92) were comparable with M-CHAT R/F. Although Q-CHAT-10-O sensitivity (0.63) is less than M-CHAT-R (without follow-up; 0.73) and specificity (0.79) is less than the two-stage R/F procedure (0.90), on balance, it is more accurate and more practical for a primary care population. After 20 months of age, the M-CHAT-R/F has adequate accuracy to rescreen, if indicated, and for the subsequent 24 month screening. Language items are often of highest value in predicting outcomes in several tools including in the screen we are now validating for 18 month olds.

The Q-CHAT-10-O with ordinal scoring and pictures can also be recommended because it shows advantages over M-CHAT-R/F with half the number of items (10 vs. 20), no requirement for a follow-up interview, and improved sensitivity. Unlike M-CHAT-R, it also contributes to equity in screening because results did not differ depending on race or socioeconomic background.

Is there an even better way to detect autism in primary care? In 2022 an article was published regarding an exciting method of early autism detection called the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised (SACS-R), an eight-item observation checklist completed at public health nurse check-ups in Australia. The observers had 4 years of nursing degree education and a 3.5-hour training session.

The SACS-R and the preschool version (for older children) had significant associations with diagnostic testing at 12, 18, 24, and 42 months. The SACS-R had excellent PPV (82.6%), NPV (98.7%), and specificity (99.6%) and moderate sensitivity (61.5%) when used between 12 and 24 months of age. Pointing, eye contact, waving “bye, bye,” social communication by showing, and pretend play were the key indicators for observations at 18 months, with absence of three or more indicating risk for autism. Different key indicators were used at the other ages, reflecting the evolution of autism symptoms. This hybrid (observation and scoring) surveillance method by professionals shows hopeful data for the critical ability to identify children at risk for autism in primary care very early but requires more than parent report, that is, new levels of autism-specific clinician training and direct observations at multiple visits over time.

The takeaway is to remember that we should all watch closely for early signs of autism, informed by research on the key findings that a professional might observe, as well as by using the best screens available. We should remember that both false positives and false negatives are inherent in screening, especially at the youngest ages. We need to combine our concern with the parent’s concern as well as screen results and be sure to follow-up closely as symptoms can change in even a few months. Many factors may prevent a family from returning to see us or following our advice to go for testing or intervention, so tracking the child and their service use is an important part of the good care we strive to provide children with autism.

Other screening tools

You may have heard of other parent-report screens for autism. It is important to compare their accuracy specifically for 18-month-olds in a community setting.

- The Infant Toddler Checklist (https://psychology-tools.com/test/infant-toddler-checklist) has moderate overall psychometrics with sensitivity ranging from 0.55 to 0.77; specificity from 0.42 to 0.85; PPV from 0.20 to 0.55; and NPV from 0.83 to 0.94. However, the data were based on a sample including both community-dwelling toddlers and those with a family history of autism.

- The Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/brief-infant-toddler-social-emotional-assessment/) – the screen’s four autism-specific scales had high specificity (84%-90%) but low sensitivity (40%-52%).

- Canvas Dx (https://canvasdx.com/) from the Cognoa company is not a parent-report measure but rather a three-part evaluation including an app-based parent questionnaire, parent uploads of home videos analyzed by a specialist, and a 13- to 15-item primary care physician observational checklist. There were 56 diagnosed of the 426 children in the 18- to 24-month-old range from a sample of children presenting with parent or clinician concerns rather than from a community sample.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

References

Sturner R et al. Autism screening at 18 months of age: A comparison of the Q-CHAT-10 and M-CHAT screeners. Molecular Autism. Jan 3;13(1):2.

Barbaro J et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Social Attention and Communication Surveillance–Revised with preschool tool for early autism detection in very young children. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e2146415.

The kids may not be alright, but psychiatry can help

When I was growing up, I can remember experiencing “duck and cover” drills at school. If a flash appeared in our peripheral vision, we were told we should not look at it but crawl under our desks. My classmates and I were being taught how to protect ourselves in case of a nuclear attack.

Clearly, had there been such an attack, ducking under our desks would not have saved us. Thankfully, such a conflict never occurred – and hopefully never will. Still, the warning did penetrate our psyches. In those days, families and children in schools were worried, and some were scared.

The situation is quite different today. Our children and grandchildren are being taught to protect themselves not from actions overseas – that never happened – but from what someone living in their community might do that has been occurring in real time. According to my daughter-in-law, her young children are taught during “lockdowns” to hide in their classrooms’ closets. During these drills, some children are directed to line up against a wall that would be out of sight of a shooter, and to stay as still as possible.

Since 2017, the number of intentional shootings in U.S. kindergarten through grade 12 schools increased precipitously (Prev Med. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107280). Imagine the psychological impact that the vigilance required to deal with such impending threats must be having on our children, as they learn to fear injury and possible death every day they go to school. I’ve talked with numerous parents about this, including my own adult children, and this is clearly a new dimension of life that is on everyone’s minds. Schools, once bastions of safety, are no longer that safe.

For many years, I’ve written about the need to destigmatize mental illness so that it is treated on a par with physical illness. As we look at the challenges faced by young people, reframing mental illness is more important now than ever. This means finding ways to increase the funding of studies that help us understand young people with mental health issues. It also means encouraging patients to pursue treatment from psychiatrists, psychologists, or mental health counselors who specialize in short-term therapy.

The emphasis here on short-term therapy is not to discourage longer-term care when needed, but clearly short-term care strategies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapies, not only work for problem resolution, they also help in the destigmatization of mental health care – as the circumscribed treatment with a clear beginning, middle, and end is consistent with CBT and consistent with much of medical care for physical disorders.

Furthermore, as we aim to destigmatize mental health care, it’s important to equate it with physical care. For example, taking a day or two from school or work for a sprained ankle, seeing a dentist, or an eye exam, plus a myriad of physical issues is quite acceptable. Why is it not also acceptable for a mental health issue and evaluation, such as for anxiety or PTSD, plus being able to talk about it without stigma? Seeing the “shrink” needs to be removed as a negative but viewed as a very positive move toward care for oneself.

In addition, children and adolescents are battling countless other health challenges that could have implications for mental health professionals, for example:

- During the height of the coronavirus pandemic, pediatric endocrinologists reportedly saw a surge of referrals for girls experiencing early puberty. Puberty should never be medicalized, but early maturation has been linked to numerous psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and eating disorders (J Pediatr Adolec Gynecol. 2022 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2022.05.005).

- A global epidemiologic study of children estimates that nearly 8 million youth lost a parent or caregiver because of a pandemic-related cause between Jan. 1, 2020, and May 1, 2022. An additional 2.5 million children were affected by the loss of secondary caregivers such as grandparents (JAMA Pediatr. 2022 Sept. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.3157).

- The inpatient and outpatient volume of adolescents and young adults receiving care for eating disorders skyrocketed before and after the pandemic, according to the results of case study series (JAMA Pediatrics. 2022 Nov 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.4346).

- Children and adolescents who developed COVID-19 suffered tremendously during the height of the pandemic. A nationwide analysis shows that COVID-19 nearly tripled children’s risks of developing new mental health illnesses, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, trauma, or stress disorder (Psychiatric Services. 2022 Jun 2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100646).

In addition to those challenges, young children are facing an increase in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. We were told the “flu” would be quite bad this year and to beware of monkeypox. However, very little mention is made of the equally distressing “epidemic” of mental health issues, PTSD, anxiety, and depression as we are still in the midst of the COVID pandemic in the United States with almost 400 deaths a day – a very unacceptable number.

Interestingly, we seem to have abandoned the use of masks as protection against COVID and other respiratory diseases, despite their effectiveness. A study in Boston that looked at children in two school districts that did not lift mask mandates demonstrated that mask wearing does indeed lead to significant reductions in the number of pediatric COVID cases. In addition to societal violence and school shootings – which certainly exacerbate anxiety – the fear of dying or the death of a loved one, tied to COVID, may lead to epidemic proportions of PTSD in children. As an article in WebMD noted, “pediatricians are imploring the federal government to declare a national emergency as cases of pediatric respiratory illnesses continue to soar.”

In light of the acknowledged mental health crisis in children, which appears epidemic, I would hope the psychiatric and psychological associations would publicly sound an alarm so that resources could be brought to bear to address this critical issue. I believe doing so would also aid in destigmatizing mental disorders, and increase education and treatment.

Layered on top of those issues are natural disasters, such as the fallout from Tropical Storm Nicole when it recently caused devastation across western Florida. The mental health trauma caused by recent tropical storms seems all but forgotten – except for those who are still suffering. All of this adds up to a society-wide mental health crisis, which seems far more expansive than monkeypox, for example. Yet monkeypox, which did lead to thousands of cases and approximately 29 deaths in the United States, was declared a national public health emergency.

Additionally, RSV killed 100-500 U.S. children under age 5 each year before the pandemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and currently it appears even worse. Yet despite the seriousness of RSV, it nowhere matches the emotional toll COVID has taken on children globally.

Let’s make it standard practice for children – and of course, adults – to be taught that anxiety is a normal response at times. We should teach that, in some cases, feeling “down” or in despair and even experiencing symptoms of PTSD based on what’s going on personally and within our environment (i.e., COVID, school shootings, etc.) are triggers and responses that can be addressed and often quickly treated by talking with a mental health professional.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

When I was growing up, I can remember experiencing “duck and cover” drills at school. If a flash appeared in our peripheral vision, we were told we should not look at it but crawl under our desks. My classmates and I were being taught how to protect ourselves in case of a nuclear attack.

Clearly, had there been such an attack, ducking under our desks would not have saved us. Thankfully, such a conflict never occurred – and hopefully never will. Still, the warning did penetrate our psyches. In those days, families and children in schools were worried, and some were scared.

The situation is quite different today. Our children and grandchildren are being taught to protect themselves not from actions overseas – that never happened – but from what someone living in their community might do that has been occurring in real time. According to my daughter-in-law, her young children are taught during “lockdowns” to hide in their classrooms’ closets. During these drills, some children are directed to line up against a wall that would be out of sight of a shooter, and to stay as still as possible.

Since 2017, the number of intentional shootings in U.S. kindergarten through grade 12 schools increased precipitously (Prev Med. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107280). Imagine the psychological impact that the vigilance required to deal with such impending threats must be having on our children, as they learn to fear injury and possible death every day they go to school. I’ve talked with numerous parents about this, including my own adult children, and this is clearly a new dimension of life that is on everyone’s minds. Schools, once bastions of safety, are no longer that safe.

For many years, I’ve written about the need to destigmatize mental illness so that it is treated on a par with physical illness. As we look at the challenges faced by young people, reframing mental illness is more important now than ever. This means finding ways to increase the funding of studies that help us understand young people with mental health issues. It also means encouraging patients to pursue treatment from psychiatrists, psychologists, or mental health counselors who specialize in short-term therapy.

The emphasis here on short-term therapy is not to discourage longer-term care when needed, but clearly short-term care strategies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapies, not only work for problem resolution, they also help in the destigmatization of mental health care – as the circumscribed treatment with a clear beginning, middle, and end is consistent with CBT and consistent with much of medical care for physical disorders.

Furthermore, as we aim to destigmatize mental health care, it’s important to equate it with physical care. For example, taking a day or two from school or work for a sprained ankle, seeing a dentist, or an eye exam, plus a myriad of physical issues is quite acceptable. Why is it not also acceptable for a mental health issue and evaluation, such as for anxiety or PTSD, plus being able to talk about it without stigma? Seeing the “shrink” needs to be removed as a negative but viewed as a very positive move toward care for oneself.

In addition, children and adolescents are battling countless other health challenges that could have implications for mental health professionals, for example:

- During the height of the coronavirus pandemic, pediatric endocrinologists reportedly saw a surge of referrals for girls experiencing early puberty. Puberty should never be medicalized, but early maturation has been linked to numerous psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and eating disorders (J Pediatr Adolec Gynecol. 2022 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2022.05.005).

- A global epidemiologic study of children estimates that nearly 8 million youth lost a parent or caregiver because of a pandemic-related cause between Jan. 1, 2020, and May 1, 2022. An additional 2.5 million children were affected by the loss of secondary caregivers such as grandparents (JAMA Pediatr. 2022 Sept. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.3157).

- The inpatient and outpatient volume of adolescents and young adults receiving care for eating disorders skyrocketed before and after the pandemic, according to the results of case study series (JAMA Pediatrics. 2022 Nov 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.4346).

- Children and adolescents who developed COVID-19 suffered tremendously during the height of the pandemic. A nationwide analysis shows that COVID-19 nearly tripled children’s risks of developing new mental health illnesses, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, trauma, or stress disorder (Psychiatric Services. 2022 Jun 2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100646).

In addition to those challenges, young children are facing an increase in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. We were told the “flu” would be quite bad this year and to beware of monkeypox. However, very little mention is made of the equally distressing “epidemic” of mental health issues, PTSD, anxiety, and depression as we are still in the midst of the COVID pandemic in the United States with almost 400 deaths a day – a very unacceptable number.

Interestingly, we seem to have abandoned the use of masks as protection against COVID and other respiratory diseases, despite their effectiveness. A study in Boston that looked at children in two school districts that did not lift mask mandates demonstrated that mask wearing does indeed lead to significant reductions in the number of pediatric COVID cases. In addition to societal violence and school shootings – which certainly exacerbate anxiety – the fear of dying or the death of a loved one, tied to COVID, may lead to epidemic proportions of PTSD in children. As an article in WebMD noted, “pediatricians are imploring the federal government to declare a national emergency as cases of pediatric respiratory illnesses continue to soar.”

In light of the acknowledged mental health crisis in children, which appears epidemic, I would hope the psychiatric and psychological associations would publicly sound an alarm so that resources could be brought to bear to address this critical issue. I believe doing so would also aid in destigmatizing mental disorders, and increase education and treatment.

Layered on top of those issues are natural disasters, such as the fallout from Tropical Storm Nicole when it recently caused devastation across western Florida. The mental health trauma caused by recent tropical storms seems all but forgotten – except for those who are still suffering. All of this adds up to a society-wide mental health crisis, which seems far more expansive than monkeypox, for example. Yet monkeypox, which did lead to thousands of cases and approximately 29 deaths in the United States, was declared a national public health emergency.

Additionally, RSV killed 100-500 U.S. children under age 5 each year before the pandemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and currently it appears even worse. Yet despite the seriousness of RSV, it nowhere matches the emotional toll COVID has taken on children globally.

Let’s make it standard practice for children – and of course, adults – to be taught that anxiety is a normal response at times. We should teach that, in some cases, feeling “down” or in despair and even experiencing symptoms of PTSD based on what’s going on personally and within our environment (i.e., COVID, school shootings, etc.) are triggers and responses that can be addressed and often quickly treated by talking with a mental health professional.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

When I was growing up, I can remember experiencing “duck and cover” drills at school. If a flash appeared in our peripheral vision, we were told we should not look at it but crawl under our desks. My classmates and I were being taught how to protect ourselves in case of a nuclear attack.

Clearly, had there been such an attack, ducking under our desks would not have saved us. Thankfully, such a conflict never occurred – and hopefully never will. Still, the warning did penetrate our psyches. In those days, families and children in schools were worried, and some were scared.

The situation is quite different today. Our children and grandchildren are being taught to protect themselves not from actions overseas – that never happened – but from what someone living in their community might do that has been occurring in real time. According to my daughter-in-law, her young children are taught during “lockdowns” to hide in their classrooms’ closets. During these drills, some children are directed to line up against a wall that would be out of sight of a shooter, and to stay as still as possible.

Since 2017, the number of intentional shootings in U.S. kindergarten through grade 12 schools increased precipitously (Prev Med. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107280). Imagine the psychological impact that the vigilance required to deal with such impending threats must be having on our children, as they learn to fear injury and possible death every day they go to school. I’ve talked with numerous parents about this, including my own adult children, and this is clearly a new dimension of life that is on everyone’s minds. Schools, once bastions of safety, are no longer that safe.

For many years, I’ve written about the need to destigmatize mental illness so that it is treated on a par with physical illness. As we look at the challenges faced by young people, reframing mental illness is more important now than ever. This means finding ways to increase the funding of studies that help us understand young people with mental health issues. It also means encouraging patients to pursue treatment from psychiatrists, psychologists, or mental health counselors who specialize in short-term therapy.

The emphasis here on short-term therapy is not to discourage longer-term care when needed, but clearly short-term care strategies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapies, not only work for problem resolution, they also help in the destigmatization of mental health care – as the circumscribed treatment with a clear beginning, middle, and end is consistent with CBT and consistent with much of medical care for physical disorders.

Furthermore, as we aim to destigmatize mental health care, it’s important to equate it with physical care. For example, taking a day or two from school or work for a sprained ankle, seeing a dentist, or an eye exam, plus a myriad of physical issues is quite acceptable. Why is it not also acceptable for a mental health issue and evaluation, such as for anxiety or PTSD, plus being able to talk about it without stigma? Seeing the “shrink” needs to be removed as a negative but viewed as a very positive move toward care for oneself.

In addition, children and adolescents are battling countless other health challenges that could have implications for mental health professionals, for example:

- During the height of the coronavirus pandemic, pediatric endocrinologists reportedly saw a surge of referrals for girls experiencing early puberty. Puberty should never be medicalized, but early maturation has been linked to numerous psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and eating disorders (J Pediatr Adolec Gynecol. 2022 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2022.05.005).

- A global epidemiologic study of children estimates that nearly 8 million youth lost a parent or caregiver because of a pandemic-related cause between Jan. 1, 2020, and May 1, 2022. An additional 2.5 million children were affected by the loss of secondary caregivers such as grandparents (JAMA Pediatr. 2022 Sept. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.3157).

- The inpatient and outpatient volume of adolescents and young adults receiving care for eating disorders skyrocketed before and after the pandemic, according to the results of case study series (JAMA Pediatrics. 2022 Nov 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.4346).

- Children and adolescents who developed COVID-19 suffered tremendously during the height of the pandemic. A nationwide analysis shows that COVID-19 nearly tripled children’s risks of developing new mental health illnesses, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, trauma, or stress disorder (Psychiatric Services. 2022 Jun 2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100646).

In addition to those challenges, young children are facing an increase in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection. We were told the “flu” would be quite bad this year and to beware of monkeypox. However, very little mention is made of the equally distressing “epidemic” of mental health issues, PTSD, anxiety, and depression as we are still in the midst of the COVID pandemic in the United States with almost 400 deaths a day – a very unacceptable number.

Interestingly, we seem to have abandoned the use of masks as protection against COVID and other respiratory diseases, despite their effectiveness. A study in Boston that looked at children in two school districts that did not lift mask mandates demonstrated that mask wearing does indeed lead to significant reductions in the number of pediatric COVID cases. In addition to societal violence and school shootings – which certainly exacerbate anxiety – the fear of dying or the death of a loved one, tied to COVID, may lead to epidemic proportions of PTSD in children. As an article in WebMD noted, “pediatricians are imploring the federal government to declare a national emergency as cases of pediatric respiratory illnesses continue to soar.”

In light of the acknowledged mental health crisis in children, which appears epidemic, I would hope the psychiatric and psychological associations would publicly sound an alarm so that resources could be brought to bear to address this critical issue. I believe doing so would also aid in destigmatizing mental disorders, and increase education and treatment.

Layered on top of those issues are natural disasters, such as the fallout from Tropical Storm Nicole when it recently caused devastation across western Florida. The mental health trauma caused by recent tropical storms seems all but forgotten – except for those who are still suffering. All of this adds up to a society-wide mental health crisis, which seems far more expansive than monkeypox, for example. Yet monkeypox, which did lead to thousands of cases and approximately 29 deaths in the United States, was declared a national public health emergency.

Additionally, RSV killed 100-500 U.S. children under age 5 each year before the pandemic, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and currently it appears even worse. Yet despite the seriousness of RSV, it nowhere matches the emotional toll COVID has taken on children globally.

Let’s make it standard practice for children – and of course, adults – to be taught that anxiety is a normal response at times. We should teach that, in some cases, feeling “down” or in despair and even experiencing symptoms of PTSD based on what’s going on personally and within our environment (i.e., COVID, school shootings, etc.) are triggers and responses that can be addressed and often quickly treated by talking with a mental health professional.

Dr. London is a practicing psychiatrist and has been a newspaper columnist for 35 years, specializing in and writing about short-term therapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and guided imagery. He is author of “Find Freedom Fast” (New York: Kettlehole Publishing, 2019). He has no conflicts of interest.

A 17-year-old male was referred by his pediatrician for evaluation of a year-long rash

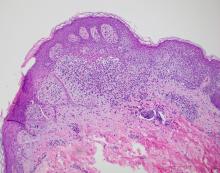

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A biopsy of the edge of one of lesions on the torso was performed. Histopathology demonstrated hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum with focal thickening of the granular cell layer, basal layer degeneration of the epidermis, and a band-like subepidermal lymphocytic infiltrate with Civatte bodies consistent with lichen planus. There was some reduction in the elastic fibers on the papillary dermis.

Given the morphology of the lesions and the histopathologic presentation, he was diagnosed with annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP). Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the skin, nails, hair, and mucosa. Lichen planus is seen in less than 1% of the population, occurring mainly in middle-aged adults and rarely seen in children. Though, there appears to be no clear racial predilection, a small study in the United States showed a higher incidence of lichen planus in Black children. Lesions with classic characteristics are pruritic, polygonal, violaceous, flat-topped papules and plaques.

There are different subtypes of lichen planus, which include papular or classic form, hypertrophic, vesiculobullous, actinic, annular, atrophic, annular atrophic, linear, follicular, lichen planus pigmentosus, lichen pigmentosa pigmentosus-inversus, lichen planus–lupus erythematosus overlap syndrome, and lichen planus pemphigoides. The annular atrophic form is the least common of all, and there are few reports in the pediatric population. AALP presents as annular papules and plaques with atrophic centers that resolve within a few months leaving postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation and, in some patients, permanent atrophic scarring.

In histopathology, the lesions show the classic characteristics of lichen planus including vacuolar interface changes and necrotic keratinocytes, hypergranulosis, band-like infiltrate in the dermis, melanin incontinence, and Civatte bodies. In AALP, the center of the lesion shows an atrophic epidermis, and there is also a characteristic partial reduction to complete destruction of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of the lesion and sometimes in the periphery as well, which helps differentiate AALP from other forms of lichen planus.

The differential diagnosis for AALP includes tinea corporis, which can present with annular lesions, but they are usually scaly and rarely resolve on their own. Pityriasis rosea lesions can also look very similar to AALP lesions, but the difference is the presence of an inner collaret of scale and a lack of atrophy in pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea is a rash that can be triggered by viral infections, medications, and vaccines and self-resolves within 10-12 weeks. Secondary syphilis can also be annular and resemble lesions of AALP. Syphilis patients are usually sexually active and may have lesions present on the palms and soles, which were not seen in our patient.

Granuloma annulare should also be included in the differential diagnosis of AALP. Granuloma annulare lesions present as annular papules or plaques with raised borders and a slightly hyperpigmented center that may appear more depressed compared to the edges of the lesion, though not atrophic as seen in AALP. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica is an inflammatory condition of the skin in which patients present with erythematous to brown papules in different stages which may have a mica-like scale, usually not seen on AALP. Sometimes a skin biopsy will be needed to differentiate between these conditions.

It is very important to make a timely diagnosis of AALP and treat the lesions early as it may leave long-lasting dyspigmentation and scarring. Though AAPL lesions can be resistant to treatment with topical medications, there are reports of improvement with superpotent topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors. In recalcitrant cases, systemic therapy with isotretinoin, acitretin, methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids, dapsone, and hydroxychloroquine can be considered. Our patient was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% with good response.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Bowers S and Warshaw EM. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-72; quiz 573-6.

Gorouhi F et al. Scientific World Journal. 2014 Jan 30;2014:742826.

Santhosh P and George M. Int J Dermatol. 2022.61:1213-7.

Sears S et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1283-7.

Weston G and Payette M. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015 Sep 16;1(3):140-9.

A 17-year-old healthy male was referred by his pediatrician for evaluation of a rash on the skin which has been present on and off for a year. During the initial presentation, the lesions were clustered on the back, were slightly itchy, and resolved after 3 months. Several new lesions have developed on the neck, torso, and extremities, leaving hypopigmented marks on the skin. He has previously been treated with topical antifungal creams, oral fluconazole, and triamcinolone ointment without resolution of the lesions.

He is not involved in any contact sports, he has not traveled outside the country, and is not taking any other medications. He is not sexually active. He also has a diagnosis of mild acne that he is currently treating with over-the-counter medications.

On physical exam he had several annular plaques with central atrophic centers and no scale. He also had some hypo- and hyperpigmented macules at the sites of prior skin lesions

Does paying people to lose weight work?

It denies the impact of the thousands of genes and dozens of hormones involved in our individual levels of hunger, cravings, and fullness. It denies the torrential current of our ultraprocessed and calorific food environment. It denies the constant push of food advertising and the role food has taken on as the star of even the smallest of events and celebrations. It denies the role of food as a seminal pleasure in a world that, even for those possessing great degrees of privilege is challenging, let alone for those facing tremendous and varied difficulties. And of course, it upholds the hateful notion that, if people just wanted it badly enough, they’d manage their weight, the corollary of which is that people with obesity are unmotivated and lazy.

Yet the notion that, if people want it badly enough, they’d make it happen, is incredibly commonplace. It’s so commonplace that NBC aired their prime-time televised reality show The Biggest Loser from 2004 through 2016, featuring people with obesity competing for a $500,000 prize during a 30-week–long orgy of fat-shaming, victim-blaming, hugely restrictive eating, and injury. It’s also so commonplace that studies are still being conducted exploring the impact of paying people to lose weight.

The most recent of these – “Effectiveness of Goal-Directed and Outcome-Based Financial Incentives for Weight Loss in Primary Care Patients With Obesity Living in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: A Randomized Clinical Trial” – examined the effects of randomly assigning participants whose annual household incomes were less than $40,000 to either a free year of Weight Watchers and the provisions of basic weight loss advice (exercise, track your food, eat healthfully, et cetera) or to an incentivized program that would see them earning up to $750 over 6 months, with dollars being awarded for such things as attendance in education sessions, keeping a food diary, recording their weight, and obtaining a certain amount of exercise or for weight loss.

Resultswise – though you might not have gathered it from the conclusion of the paper, which states that incentives were more effective at 12 months – the average incentivized participant lost roughly 6 pounds more than those given only resources. It should also be mentioned that over half of the incentivized group did not complete the study.

That these sorts of studies are still being conducted is depressing. Medicine and academia need to actively stop promoting harmful stereotypes when it comes to the genesis of a chronic noncommunicable disease that is not caused by a lack of desire, needing the right incentive, but is rather caused by the interaction of millions of years of evolution during extreme dietary insecurity with a modern-day food environment and culture that constantly offers, provides, and encourages consumption. This is especially true now that there are effective antiobesity medications whose success underwrites the notion that it’s physiology, rather than a lack of wanting it enough, that gets in the way of sustained success.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It denies the impact of the thousands of genes and dozens of hormones involved in our individual levels of hunger, cravings, and fullness. It denies the torrential current of our ultraprocessed and calorific food environment. It denies the constant push of food advertising and the role food has taken on as the star of even the smallest of events and celebrations. It denies the role of food as a seminal pleasure in a world that, even for those possessing great degrees of privilege is challenging, let alone for those facing tremendous and varied difficulties. And of course, it upholds the hateful notion that, if people just wanted it badly enough, they’d manage their weight, the corollary of which is that people with obesity are unmotivated and lazy.

Yet the notion that, if people want it badly enough, they’d make it happen, is incredibly commonplace. It’s so commonplace that NBC aired their prime-time televised reality show The Biggest Loser from 2004 through 2016, featuring people with obesity competing for a $500,000 prize during a 30-week–long orgy of fat-shaming, victim-blaming, hugely restrictive eating, and injury. It’s also so commonplace that studies are still being conducted exploring the impact of paying people to lose weight.

The most recent of these – “Effectiveness of Goal-Directed and Outcome-Based Financial Incentives for Weight Loss in Primary Care Patients With Obesity Living in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: A Randomized Clinical Trial” – examined the effects of randomly assigning participants whose annual household incomes were less than $40,000 to either a free year of Weight Watchers and the provisions of basic weight loss advice (exercise, track your food, eat healthfully, et cetera) or to an incentivized program that would see them earning up to $750 over 6 months, with dollars being awarded for such things as attendance in education sessions, keeping a food diary, recording their weight, and obtaining a certain amount of exercise or for weight loss.

Resultswise – though you might not have gathered it from the conclusion of the paper, which states that incentives were more effective at 12 months – the average incentivized participant lost roughly 6 pounds more than those given only resources. It should also be mentioned that over half of the incentivized group did not complete the study.

That these sorts of studies are still being conducted is depressing. Medicine and academia need to actively stop promoting harmful stereotypes when it comes to the genesis of a chronic noncommunicable disease that is not caused by a lack of desire, needing the right incentive, but is rather caused by the interaction of millions of years of evolution during extreme dietary insecurity with a modern-day food environment and culture that constantly offers, provides, and encourages consumption. This is especially true now that there are effective antiobesity medications whose success underwrites the notion that it’s physiology, rather than a lack of wanting it enough, that gets in the way of sustained success.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It denies the impact of the thousands of genes and dozens of hormones involved in our individual levels of hunger, cravings, and fullness. It denies the torrential current of our ultraprocessed and calorific food environment. It denies the constant push of food advertising and the role food has taken on as the star of even the smallest of events and celebrations. It denies the role of food as a seminal pleasure in a world that, even for those possessing great degrees of privilege is challenging, let alone for those facing tremendous and varied difficulties. And of course, it upholds the hateful notion that, if people just wanted it badly enough, they’d manage their weight, the corollary of which is that people with obesity are unmotivated and lazy.

Yet the notion that, if people want it badly enough, they’d make it happen, is incredibly commonplace. It’s so commonplace that NBC aired their prime-time televised reality show The Biggest Loser from 2004 through 2016, featuring people with obesity competing for a $500,000 prize during a 30-week–long orgy of fat-shaming, victim-blaming, hugely restrictive eating, and injury. It’s also so commonplace that studies are still being conducted exploring the impact of paying people to lose weight.

The most recent of these – “Effectiveness of Goal-Directed and Outcome-Based Financial Incentives for Weight Loss in Primary Care Patients With Obesity Living in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: A Randomized Clinical Trial” – examined the effects of randomly assigning participants whose annual household incomes were less than $40,000 to either a free year of Weight Watchers and the provisions of basic weight loss advice (exercise, track your food, eat healthfully, et cetera) or to an incentivized program that would see them earning up to $750 over 6 months, with dollars being awarded for such things as attendance in education sessions, keeping a food diary, recording their weight, and obtaining a certain amount of exercise or for weight loss.

Resultswise – though you might not have gathered it from the conclusion of the paper, which states that incentives were more effective at 12 months – the average incentivized participant lost roughly 6 pounds more than those given only resources. It should also be mentioned that over half of the incentivized group did not complete the study.

That these sorts of studies are still being conducted is depressing. Medicine and academia need to actively stop promoting harmful stereotypes when it comes to the genesis of a chronic noncommunicable disease that is not caused by a lack of desire, needing the right incentive, but is rather caused by the interaction of millions of years of evolution during extreme dietary insecurity with a modern-day food environment and culture that constantly offers, provides, and encourages consumption. This is especially true now that there are effective antiobesity medications whose success underwrites the notion that it’s physiology, rather than a lack of wanting it enough, that gets in the way of sustained success.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What in medicine is “permissible but not edifying”?

Morality is often talked about in binary terms, black and white, right or wrong. That is how children 4-8 years old first conceive of it. Moral development progresses alongside motor, language, and social skills, but pediatricians typically do not screen for it or chart it. In adolescence, the ability for abstract thought develops and, once susceptibility to peer pressure lessens, nuances begin to shade the binary model. Honor codes become possible by the college years; scandals at colleges and military academies demonstrate that some 18- to 22-year-old young adults still lack that maturity. Lawrence Kohlberg, PhD, in the 1950s proposed a six-stage model of moral development and indicated that some people never achieve the upper stages.

Recently, neuroimaging research has demonstrated that the prefrontal cortex is still developing up to 25 years of age. Those data have ramifications for obtaining truly informed consent for medical procedures. Arbitrarily, driver’s licenses are issued at 16 years of age, the right to vote comes at age 18, and the purchase of alcohol allowed at age 21. Consent for medical care varies by state and by procedure. Treatment for general medical care, pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and mental health problems often have different age requirements. In some states, a 14-year-old can give consent for treatment of depression or pregnancy but cannot get a tattoo.

The rules for firearms are also complex and vary by state. Perhaps more important is the determination of medical, psychological, moral, and criminal conditions for which guns should be removed from someone’s access. Some states have created formalized red flag laws to accomplish this. Other states have informal procedures used by police and social workers rather than involving medical personnel. Recent gun-related tragedies at a St. Louis high school near me and at a Colorado Springs bar demonstrate deficiencies in the red flag approach, with multiple fatal consequences.