User login

Hair Repigmentation as a Melanoma Warning Sign

To the Editor:

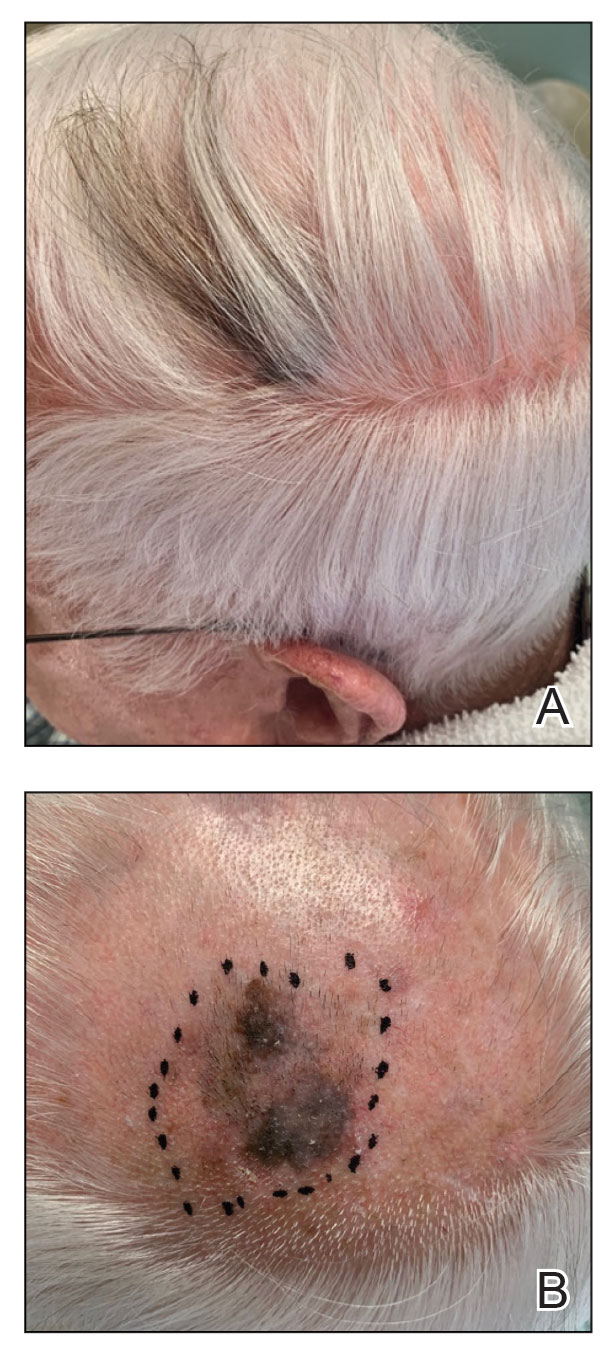

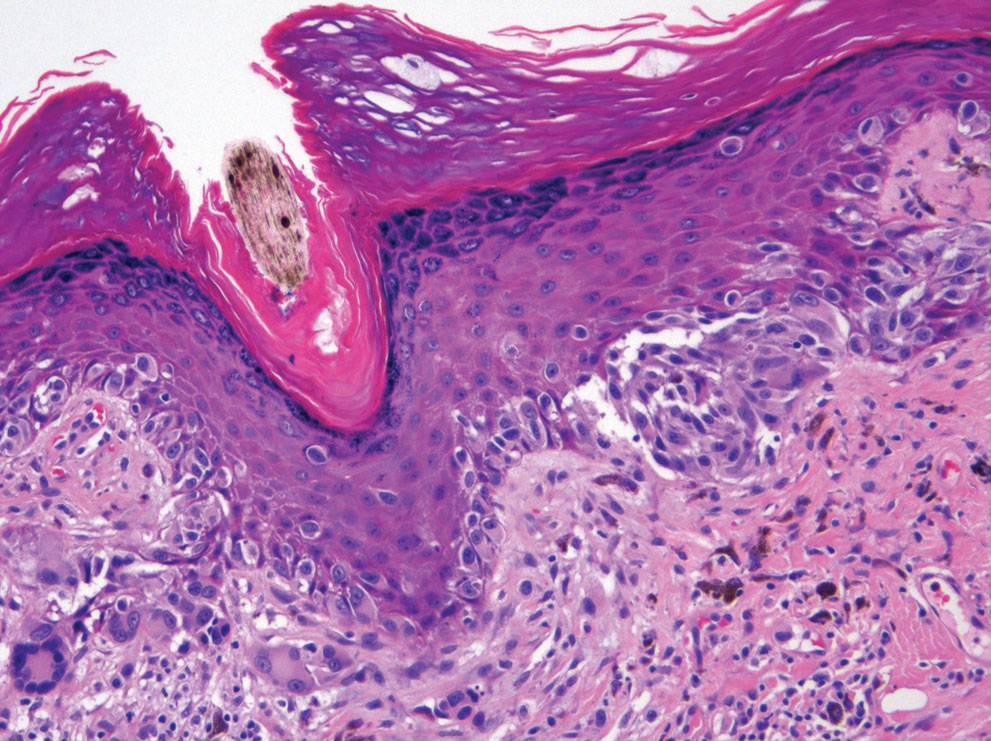

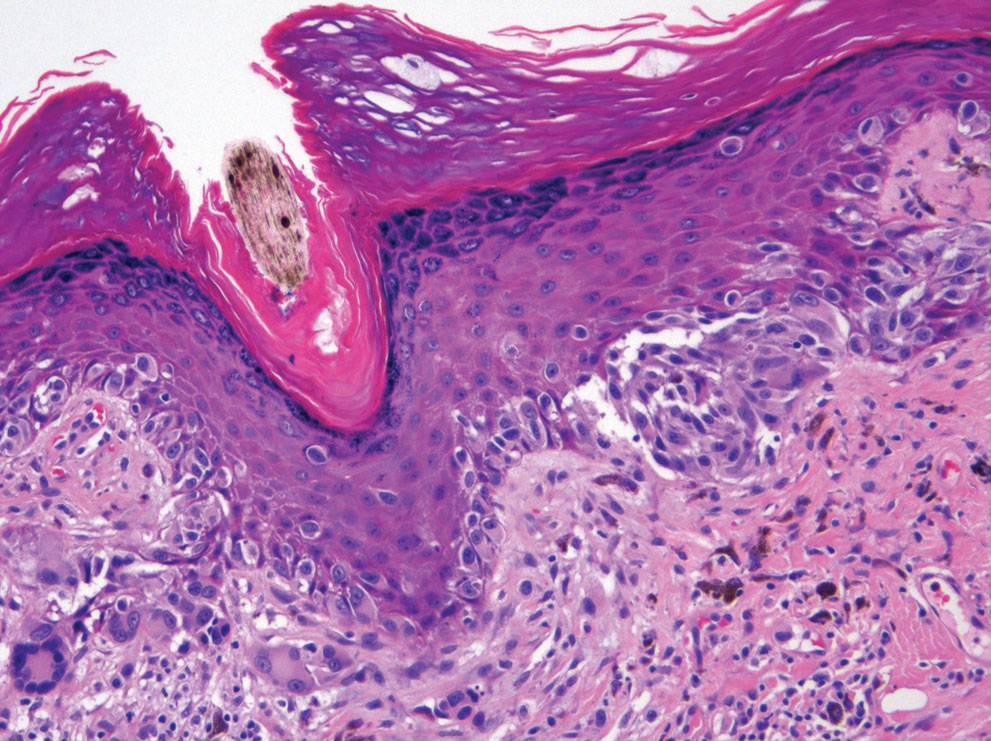

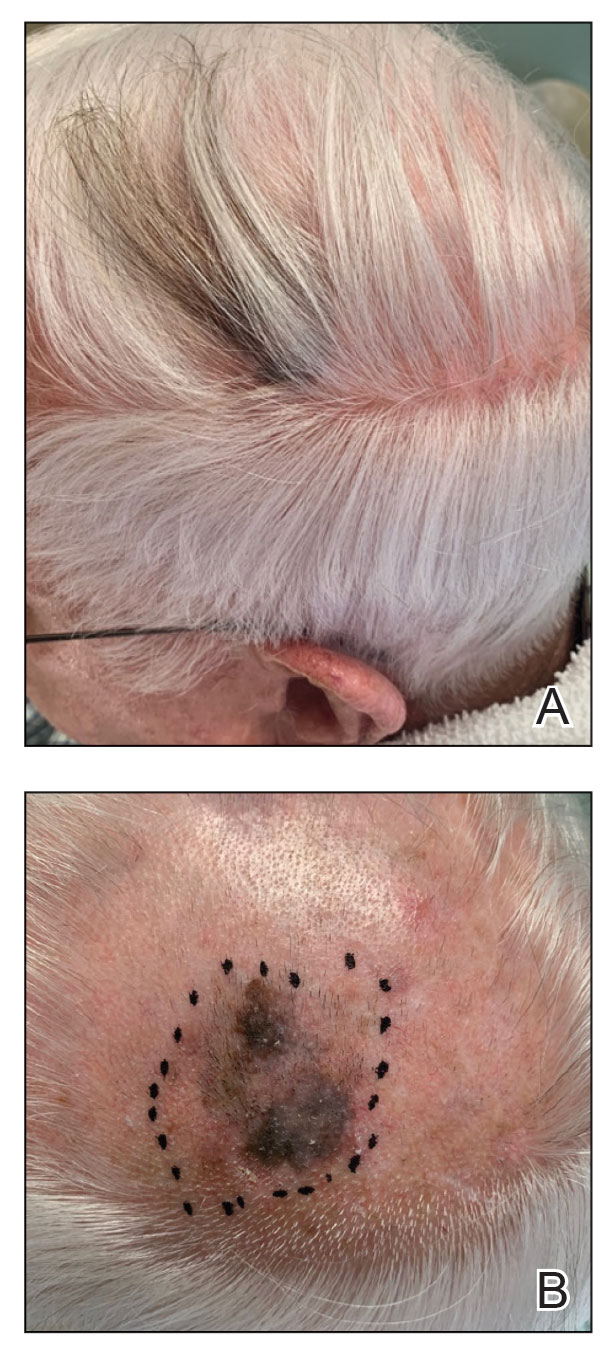

An 85-year-old man with a history of hypertension and chronic kidney disease presented with a localized darkening patch of hair on the left parietal scalp that had progressed over the last 7 years (Figure 1A). He had no prior history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed the remainder of the hair was gray. There was an irregularly pigmented plaque on the skin underlying the darkened hair measuring 5.0 cm in diameter that was confirmed to be melanoma (Figure 1B). He underwent a staged excision to remove the lesion. The surgical defect was closed via a 5.0×6.0-cm full-thickness skin graft.

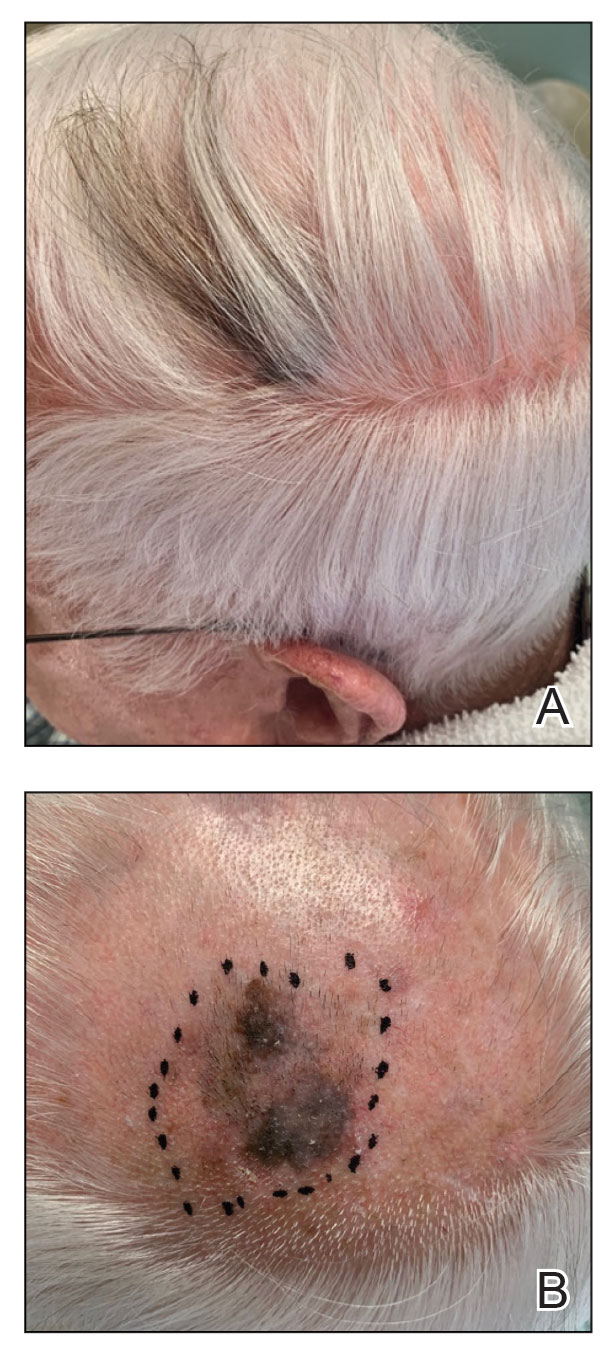

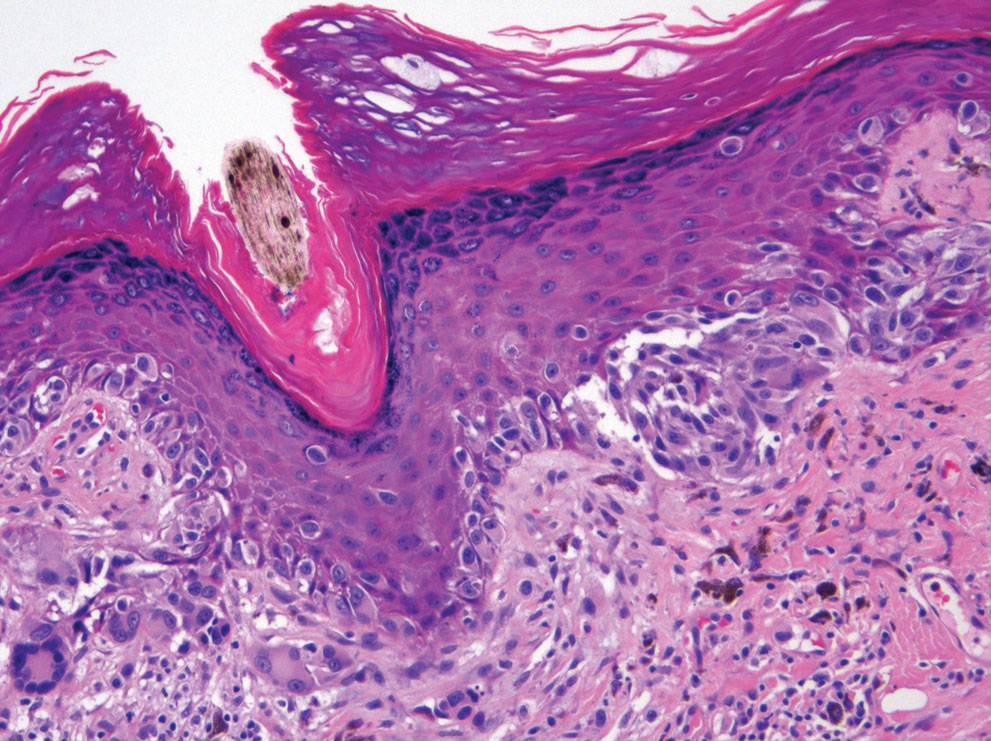

The initial biopsy showed melanoma in situ. However, the final pathology report following the excision revealed an invasive melanoma with a Breslow depth of 1.0 mm (Clark level IV; American Joint Committee on Cancer T1b).1 Histopathology showed pigment deposition with surrounding deep follicular extension of melanoma (Figure 2).

The patient declined a sentinel lymph node biopsy and agreed to a genetic profile assessment.2 The results of the test identified the patient had a low probability of a positive sentinel lymph node and the lowest risk of melanoma recurrence within 5 years. The patient was clear of disease at 12-month follow-up.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hair repigmentation and melanoma, there have been 11 other reported cases of hair repigmentation associated with melanoma (Table).3-13 It initially was suspected that this rare phenomenon primarily existed in the female population, as the first 5 cases were reported solely in females,3-7 possibly due to the prevalence of androgenetic alopecia in males.11 However, 6 cases of repigmentation associated with melanoma were later reported in males8-13; our patient represents an additional reported case in a male. It is unknown if there is a higher prevalence of this phenomenon among males or females.

Most previously reported cases of repigmentation were associated with melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type. Repigmentation also has been reported in malignant melanoma, as documented in our patient, as well as desmoplastic and amelanotic melanoma.5,6 In every case, the color of the repigmentation was darker than the rest of the patient’s hair; however, the repigmentation color can be different from the patient’s original hair color from their youth.4,5,11

The exact mechanism responsible for hair repigmentation in the setting of melanoma is unclear. It has been speculated from prior cases that repigmentation may be caused by paracrine stimulation from melanoma cells activating adjacent benign hair follicle melanocytes to produce melanin.7,14,15 This process likely is due to cytokines or growth factors, such as c-kit ligand.14,15 Several neural and immune networks and mediators activate the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT, which is thought to play a role in activating melanogenesis within the hair bulb.14 These signals also could originate from changes in the microenvironment instead of the melanoma cells themselves.6 Another possible mechanism is that repigmentation was caused by melanin-producing malignant melanocytes.4

Because this phenomenon typically occurs in older patients, the cause of repigmentation also could be related to chronic sun damage, which may result in upregulation of stem cell factor and α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone, as well as other molecules associated with melanogenesis, such as c-KIT receptor and tyrosinase.15,16 Upregulation of these molecules can lead to an increased number of melanocytes within the hair bulb. In addition, UVA and narrowband UVB have been recognized as major players in melanocyte stimulation. Phototherapy with UVA or narrowband UVB has been used for repigmentation in vitiligo patients.17

In cases without invasion of hair follicles by malignant cells, repigmentation more likely results from external signals stimulating benign bulbar melanocytes to produce melanin rather than melanoma cell growth extending into the hair bulb.6 In these cases, there is an increase in the number of hair bulbar melanocytes with a lack of malignant morphology in the hair bulb.8 If the signals are directly from melanoma cells in the hair bulb, it is unknown how the malignant cells upregulated melanogenesis in adjacent benign melanocytes or which specific signals required for normal pigmentation were involved in these repigmentation cases.6

Use of medications was ruled out as an underlying cause of the repigmentation in our patient. Drug-related repigmentation of the hair typically is observed in a diffuse generalized pattern. In our case, the repigmentation was localized to the area of the underlying dark patch, and the patient was not on any medications that could cause hair hyperpigmentation. Hyperpigmentation has been associated with acitretin, lenalidomide, corticosteroids, erlotinib, latanoprost, verapamil, tamoxifen, levodopa, thalidomide, PD-1 inhibitors, and tumor necrosis α inhibitors.18-30 Repigmentation also has been reported after local radiotherapy and herpes zoster infection.31,32

The underlying melanoma in our patient was removed by staged square excision. Excision was the treatment of choice for most similar reported cases. Radiotherapy was utilized in two different cases.3,4 In one case, radiotherapy was successfully used to treat melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type; the patient’s hair grew back to its original color, which suggests that normal hair physiology was restored once melanoma cells were eliminated.3 One reported case demonstrated successful treatment of lentigo maligna type–melanoma with imiquimod cream 5% applied 6 times weekly for 9 months with a positive cosmetic result.9 The exact mechanism of imiquimod is not fully understood. Imiquimod induces cytokines to stimulate the production of IFN-α via activation of toll-like receptor 7.33 There was complete clearing of the lesion as well as the hair pigmentation,9 which suggests that the treatment also eliminated deeper cells influencing pigmentation. A case of malignant amelanotic melanoma was successfully treated with anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks), with no recurrence at 12 months. Pembrolizumab acts as an immune checkpoint inhibitor by binding to the PD-1 receptor and allowing the immune system to recognize and attack melanoma cells. After 5 doses of pembrolizumab, the patient was clear of disease and his hair color returned to gray.5

In 2022, melanoma was estimated to be the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer among men and women in the United States.34 Early melanoma detection is a critical factor in achieving positive patient outcomes. Hair repigmentation is a potentially serious phenomenon that warrants a physician visit. Melanoma lesions under the hair may be overlooked because of limited visibility. Physicians must inspect spontaneous hair repigmentation with high suspicion and interpret the change as a possible indirect result of melanoma. Overall, it is important to increase public awareness of regular skin checks and melanoma warning signs.

- Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence‐based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472-492.

- Vetto JT, Hsueh EC, Gastman BR, et al. Guidance of sentinel lymph node biopsy decisions in patients with T1–T2 melanoma using gene expression profiling. Futur Oncol. 2019;15:1207-1217.

- Dummer R. Hair repigmentation in lentigo maligna. Lancet. 2001;357:598.

- Inzinger M, Massone C, Arzberger E, et al. Hair repigmentation in melanoma. Lancet. 2013;382:1224.

- Rahim RR, Husain A, Tobin DJ, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma presenting with localized hair repigmentation. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1371-1373.

- Tiger JB, Habeshian KA, Barton DT, et al. Repigmentation of hair associated with melanoma in situ of scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E144-E145.

- Amann VC, Dummer R. Localized hair repigmentation in a 91-year-old woman. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:81-82.

- Chan C, Magro CM, Pham AK, et al. Spontaneous hair repigmentation in an 80-year-old man: a case of melanoma-associated hair repigmentation and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:671-674.

- Lackey AE, Glassman G, Grichnik J, et al. Repigmentation of gray hairs with lentigo maligna and response to topical imiquimod. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:1015-1017.

- Chew T, Pannell M, Jeeves A. Focal hair re-pigmentation associated with melanoma of the scalp. ANZ J Surg. 2019;90:1175-1176.

- López-Sánchez C, Collgros H. Hair repigmentation as a clue for scalp melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;61:179-180.

- Gessler J, Tejasvi T, Bresler SC. Repigmentation of scalp hair: a feature of early melanoma. Am J Med. 2023;136:E7-E8.

- Hasegawa T, Iino S, Kitakaze K, et al. Repigmentation of aging gray hair associated with unrecognized development and progression of amelanotic melanoma of the scalp: a physiological alert underlying hair rejuvenation. J Dermatol. 2021;48:E281-E283. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15881

- D’Mello SAN, Finlay GJ, Baguley BC, et al. Signaling pathways in melanogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1144.

- Hachiya A, Kobayashi A, Ohuchi A, et al. The paracrine role of stem cell factor/c-kit signaling in the activation of human melanocytes in ultraviolet-B-induced pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:578-586.

- Slominski A, Wortsman J, Plonka PM, et al. Hair follicle pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:13-21.

- Falabella R. Vitiligo and the melanocyte reservoir. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:313.

- Seckin D, Yildiz A. Repigmentation and curling of hair after acitretin therapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:214-216.

- Dasanu CA, Mitsis D, Alexandrescu DT. Hair repigmentation associated with the use of lenalidomide: graying may not be an irreversible process! J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2013;19:165-169.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AI, Lowe PM. Hair repigmentation with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 immunotherapy: a novel hypothesis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:112-113. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4420

- Tintle SJ, Dabade TS, Kalish RA, et al. Repigmentation of hair following adalimumab therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6fn0t1xz.

- Penzi LR, Manatis-Lornell A, Saavedra A, et al. Hair repigmentation associated with the use of brentuximab. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:563-565.

- Khaled A, Trojjets S, Zeglaoui F, et al. Repigmentation of the white hair after systemic corticosteroids for bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2008;22:1018-1020.

- Cheng YP, Chen HJ, Chiu HC. Erlotinib-induced hair repigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E55-E57.

- Bellandi S, Amato L, Cipollini EM, et al. Repigmentation of hair after latanoprost therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2011;25:1485-1487.

- Read GM. Verapamil and hair colour change. Lancet. 1991;338:1520.

- Hampson JP, Donnelly A, Lewis‐Jones MS, et al. Tamoxifen‐induced hair colour change. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:483-484.

- Reynolds NJ, Crossley J, Ferguson I, et al. Darkening of white hair in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:317-318.

- Lovering S, Miao W, Bailie T, et al. Hair repigmentation associated with thalidomide use for the treatment of multiple myeloma. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215521.

- Rivera N, Boada A, Bielsa MI, et al. Hair repigmentation during immunotherapy treatment with an anti–programmed cell death 1 and anti–programmed cell death ligand 1 agent for lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1162-1165.

- Prasad S, Dougheney N, Hong A. Scalp hair repigmentation in the penumbral region of radiotherapy–a case series. Int J Radiol Radiat Ther. 2020;7:151-157.

- Adiga GU, Rehman KL, Wiernik PH. Permanent localized hair repigmentation following herpes zoster infection. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:569-570.

- Hanna E, Abadi R, Abbas O. Imiquimod in dermatology: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:831-844.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7-33.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old man with a history of hypertension and chronic kidney disease presented with a localized darkening patch of hair on the left parietal scalp that had progressed over the last 7 years (Figure 1A). He had no prior history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed the remainder of the hair was gray. There was an irregularly pigmented plaque on the skin underlying the darkened hair measuring 5.0 cm in diameter that was confirmed to be melanoma (Figure 1B). He underwent a staged excision to remove the lesion. The surgical defect was closed via a 5.0×6.0-cm full-thickness skin graft.

The initial biopsy showed melanoma in situ. However, the final pathology report following the excision revealed an invasive melanoma with a Breslow depth of 1.0 mm (Clark level IV; American Joint Committee on Cancer T1b).1 Histopathology showed pigment deposition with surrounding deep follicular extension of melanoma (Figure 2).

The patient declined a sentinel lymph node biopsy and agreed to a genetic profile assessment.2 The results of the test identified the patient had a low probability of a positive sentinel lymph node and the lowest risk of melanoma recurrence within 5 years. The patient was clear of disease at 12-month follow-up.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hair repigmentation and melanoma, there have been 11 other reported cases of hair repigmentation associated with melanoma (Table).3-13 It initially was suspected that this rare phenomenon primarily existed in the female population, as the first 5 cases were reported solely in females,3-7 possibly due to the prevalence of androgenetic alopecia in males.11 However, 6 cases of repigmentation associated with melanoma were later reported in males8-13; our patient represents an additional reported case in a male. It is unknown if there is a higher prevalence of this phenomenon among males or females.

Most previously reported cases of repigmentation were associated with melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type. Repigmentation also has been reported in malignant melanoma, as documented in our patient, as well as desmoplastic and amelanotic melanoma.5,6 In every case, the color of the repigmentation was darker than the rest of the patient’s hair; however, the repigmentation color can be different from the patient’s original hair color from their youth.4,5,11

The exact mechanism responsible for hair repigmentation in the setting of melanoma is unclear. It has been speculated from prior cases that repigmentation may be caused by paracrine stimulation from melanoma cells activating adjacent benign hair follicle melanocytes to produce melanin.7,14,15 This process likely is due to cytokines or growth factors, such as c-kit ligand.14,15 Several neural and immune networks and mediators activate the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT, which is thought to play a role in activating melanogenesis within the hair bulb.14 These signals also could originate from changes in the microenvironment instead of the melanoma cells themselves.6 Another possible mechanism is that repigmentation was caused by melanin-producing malignant melanocytes.4

Because this phenomenon typically occurs in older patients, the cause of repigmentation also could be related to chronic sun damage, which may result in upregulation of stem cell factor and α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone, as well as other molecules associated with melanogenesis, such as c-KIT receptor and tyrosinase.15,16 Upregulation of these molecules can lead to an increased number of melanocytes within the hair bulb. In addition, UVA and narrowband UVB have been recognized as major players in melanocyte stimulation. Phototherapy with UVA or narrowband UVB has been used for repigmentation in vitiligo patients.17

In cases without invasion of hair follicles by malignant cells, repigmentation more likely results from external signals stimulating benign bulbar melanocytes to produce melanin rather than melanoma cell growth extending into the hair bulb.6 In these cases, there is an increase in the number of hair bulbar melanocytes with a lack of malignant morphology in the hair bulb.8 If the signals are directly from melanoma cells in the hair bulb, it is unknown how the malignant cells upregulated melanogenesis in adjacent benign melanocytes or which specific signals required for normal pigmentation were involved in these repigmentation cases.6

Use of medications was ruled out as an underlying cause of the repigmentation in our patient. Drug-related repigmentation of the hair typically is observed in a diffuse generalized pattern. In our case, the repigmentation was localized to the area of the underlying dark patch, and the patient was not on any medications that could cause hair hyperpigmentation. Hyperpigmentation has been associated with acitretin, lenalidomide, corticosteroids, erlotinib, latanoprost, verapamil, tamoxifen, levodopa, thalidomide, PD-1 inhibitors, and tumor necrosis α inhibitors.18-30 Repigmentation also has been reported after local radiotherapy and herpes zoster infection.31,32

The underlying melanoma in our patient was removed by staged square excision. Excision was the treatment of choice for most similar reported cases. Radiotherapy was utilized in two different cases.3,4 In one case, radiotherapy was successfully used to treat melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type; the patient’s hair grew back to its original color, which suggests that normal hair physiology was restored once melanoma cells were eliminated.3 One reported case demonstrated successful treatment of lentigo maligna type–melanoma with imiquimod cream 5% applied 6 times weekly for 9 months with a positive cosmetic result.9 The exact mechanism of imiquimod is not fully understood. Imiquimod induces cytokines to stimulate the production of IFN-α via activation of toll-like receptor 7.33 There was complete clearing of the lesion as well as the hair pigmentation,9 which suggests that the treatment also eliminated deeper cells influencing pigmentation. A case of malignant amelanotic melanoma was successfully treated with anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks), with no recurrence at 12 months. Pembrolizumab acts as an immune checkpoint inhibitor by binding to the PD-1 receptor and allowing the immune system to recognize and attack melanoma cells. After 5 doses of pembrolizumab, the patient was clear of disease and his hair color returned to gray.5

In 2022, melanoma was estimated to be the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer among men and women in the United States.34 Early melanoma detection is a critical factor in achieving positive patient outcomes. Hair repigmentation is a potentially serious phenomenon that warrants a physician visit. Melanoma lesions under the hair may be overlooked because of limited visibility. Physicians must inspect spontaneous hair repigmentation with high suspicion and interpret the change as a possible indirect result of melanoma. Overall, it is important to increase public awareness of regular skin checks and melanoma warning signs.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old man with a history of hypertension and chronic kidney disease presented with a localized darkening patch of hair on the left parietal scalp that had progressed over the last 7 years (Figure 1A). He had no prior history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed the remainder of the hair was gray. There was an irregularly pigmented plaque on the skin underlying the darkened hair measuring 5.0 cm in diameter that was confirmed to be melanoma (Figure 1B). He underwent a staged excision to remove the lesion. The surgical defect was closed via a 5.0×6.0-cm full-thickness skin graft.

The initial biopsy showed melanoma in situ. However, the final pathology report following the excision revealed an invasive melanoma with a Breslow depth of 1.0 mm (Clark level IV; American Joint Committee on Cancer T1b).1 Histopathology showed pigment deposition with surrounding deep follicular extension of melanoma (Figure 2).

The patient declined a sentinel lymph node biopsy and agreed to a genetic profile assessment.2 The results of the test identified the patient had a low probability of a positive sentinel lymph node and the lowest risk of melanoma recurrence within 5 years. The patient was clear of disease at 12-month follow-up.

Based on a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms hair repigmentation and melanoma, there have been 11 other reported cases of hair repigmentation associated with melanoma (Table).3-13 It initially was suspected that this rare phenomenon primarily existed in the female population, as the first 5 cases were reported solely in females,3-7 possibly due to the prevalence of androgenetic alopecia in males.11 However, 6 cases of repigmentation associated with melanoma were later reported in males8-13; our patient represents an additional reported case in a male. It is unknown if there is a higher prevalence of this phenomenon among males or females.

Most previously reported cases of repigmentation were associated with melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type. Repigmentation also has been reported in malignant melanoma, as documented in our patient, as well as desmoplastic and amelanotic melanoma.5,6 In every case, the color of the repigmentation was darker than the rest of the patient’s hair; however, the repigmentation color can be different from the patient’s original hair color from their youth.4,5,11

The exact mechanism responsible for hair repigmentation in the setting of melanoma is unclear. It has been speculated from prior cases that repigmentation may be caused by paracrine stimulation from melanoma cells activating adjacent benign hair follicle melanocytes to produce melanin.7,14,15 This process likely is due to cytokines or growth factors, such as c-kit ligand.14,15 Several neural and immune networks and mediators activate the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT, which is thought to play a role in activating melanogenesis within the hair bulb.14 These signals also could originate from changes in the microenvironment instead of the melanoma cells themselves.6 Another possible mechanism is that repigmentation was caused by melanin-producing malignant melanocytes.4

Because this phenomenon typically occurs in older patients, the cause of repigmentation also could be related to chronic sun damage, which may result in upregulation of stem cell factor and α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone, as well as other molecules associated with melanogenesis, such as c-KIT receptor and tyrosinase.15,16 Upregulation of these molecules can lead to an increased number of melanocytes within the hair bulb. In addition, UVA and narrowband UVB have been recognized as major players in melanocyte stimulation. Phototherapy with UVA or narrowband UVB has been used for repigmentation in vitiligo patients.17

In cases without invasion of hair follicles by malignant cells, repigmentation more likely results from external signals stimulating benign bulbar melanocytes to produce melanin rather than melanoma cell growth extending into the hair bulb.6 In these cases, there is an increase in the number of hair bulbar melanocytes with a lack of malignant morphology in the hair bulb.8 If the signals are directly from melanoma cells in the hair bulb, it is unknown how the malignant cells upregulated melanogenesis in adjacent benign melanocytes or which specific signals required for normal pigmentation were involved in these repigmentation cases.6

Use of medications was ruled out as an underlying cause of the repigmentation in our patient. Drug-related repigmentation of the hair typically is observed in a diffuse generalized pattern. In our case, the repigmentation was localized to the area of the underlying dark patch, and the patient was not on any medications that could cause hair hyperpigmentation. Hyperpigmentation has been associated with acitretin, lenalidomide, corticosteroids, erlotinib, latanoprost, verapamil, tamoxifen, levodopa, thalidomide, PD-1 inhibitors, and tumor necrosis α inhibitors.18-30 Repigmentation also has been reported after local radiotherapy and herpes zoster infection.31,32

The underlying melanoma in our patient was removed by staged square excision. Excision was the treatment of choice for most similar reported cases. Radiotherapy was utilized in two different cases.3,4 In one case, radiotherapy was successfully used to treat melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type; the patient’s hair grew back to its original color, which suggests that normal hair physiology was restored once melanoma cells were eliminated.3 One reported case demonstrated successful treatment of lentigo maligna type–melanoma with imiquimod cream 5% applied 6 times weekly for 9 months with a positive cosmetic result.9 The exact mechanism of imiquimod is not fully understood. Imiquimod induces cytokines to stimulate the production of IFN-α via activation of toll-like receptor 7.33 There was complete clearing of the lesion as well as the hair pigmentation,9 which suggests that the treatment also eliminated deeper cells influencing pigmentation. A case of malignant amelanotic melanoma was successfully treated with anti–PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks), with no recurrence at 12 months. Pembrolizumab acts as an immune checkpoint inhibitor by binding to the PD-1 receptor and allowing the immune system to recognize and attack melanoma cells. After 5 doses of pembrolizumab, the patient was clear of disease and his hair color returned to gray.5

In 2022, melanoma was estimated to be the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer among men and women in the United States.34 Early melanoma detection is a critical factor in achieving positive patient outcomes. Hair repigmentation is a potentially serious phenomenon that warrants a physician visit. Melanoma lesions under the hair may be overlooked because of limited visibility. Physicians must inspect spontaneous hair repigmentation with high suspicion and interpret the change as a possible indirect result of melanoma. Overall, it is important to increase public awareness of regular skin checks and melanoma warning signs.

- Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence‐based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472-492.

- Vetto JT, Hsueh EC, Gastman BR, et al. Guidance of sentinel lymph node biopsy decisions in patients with T1–T2 melanoma using gene expression profiling. Futur Oncol. 2019;15:1207-1217.

- Dummer R. Hair repigmentation in lentigo maligna. Lancet. 2001;357:598.

- Inzinger M, Massone C, Arzberger E, et al. Hair repigmentation in melanoma. Lancet. 2013;382:1224.

- Rahim RR, Husain A, Tobin DJ, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma presenting with localized hair repigmentation. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1371-1373.

- Tiger JB, Habeshian KA, Barton DT, et al. Repigmentation of hair associated with melanoma in situ of scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E144-E145.

- Amann VC, Dummer R. Localized hair repigmentation in a 91-year-old woman. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:81-82.

- Chan C, Magro CM, Pham AK, et al. Spontaneous hair repigmentation in an 80-year-old man: a case of melanoma-associated hair repigmentation and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:671-674.

- Lackey AE, Glassman G, Grichnik J, et al. Repigmentation of gray hairs with lentigo maligna and response to topical imiquimod. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:1015-1017.

- Chew T, Pannell M, Jeeves A. Focal hair re-pigmentation associated with melanoma of the scalp. ANZ J Surg. 2019;90:1175-1176.

- López-Sánchez C, Collgros H. Hair repigmentation as a clue for scalp melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;61:179-180.

- Gessler J, Tejasvi T, Bresler SC. Repigmentation of scalp hair: a feature of early melanoma. Am J Med. 2023;136:E7-E8.

- Hasegawa T, Iino S, Kitakaze K, et al. Repigmentation of aging gray hair associated with unrecognized development and progression of amelanotic melanoma of the scalp: a physiological alert underlying hair rejuvenation. J Dermatol. 2021;48:E281-E283. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15881

- D’Mello SAN, Finlay GJ, Baguley BC, et al. Signaling pathways in melanogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1144.

- Hachiya A, Kobayashi A, Ohuchi A, et al. The paracrine role of stem cell factor/c-kit signaling in the activation of human melanocytes in ultraviolet-B-induced pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:578-586.

- Slominski A, Wortsman J, Plonka PM, et al. Hair follicle pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:13-21.

- Falabella R. Vitiligo and the melanocyte reservoir. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:313.

- Seckin D, Yildiz A. Repigmentation and curling of hair after acitretin therapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:214-216.

- Dasanu CA, Mitsis D, Alexandrescu DT. Hair repigmentation associated with the use of lenalidomide: graying may not be an irreversible process! J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2013;19:165-169.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AI, Lowe PM. Hair repigmentation with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 immunotherapy: a novel hypothesis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:112-113. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4420

- Tintle SJ, Dabade TS, Kalish RA, et al. Repigmentation of hair following adalimumab therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6fn0t1xz.

- Penzi LR, Manatis-Lornell A, Saavedra A, et al. Hair repigmentation associated with the use of brentuximab. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:563-565.

- Khaled A, Trojjets S, Zeglaoui F, et al. Repigmentation of the white hair after systemic corticosteroids for bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2008;22:1018-1020.

- Cheng YP, Chen HJ, Chiu HC. Erlotinib-induced hair repigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E55-E57.

- Bellandi S, Amato L, Cipollini EM, et al. Repigmentation of hair after latanoprost therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2011;25:1485-1487.

- Read GM. Verapamil and hair colour change. Lancet. 1991;338:1520.

- Hampson JP, Donnelly A, Lewis‐Jones MS, et al. Tamoxifen‐induced hair colour change. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:483-484.

- Reynolds NJ, Crossley J, Ferguson I, et al. Darkening of white hair in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:317-318.

- Lovering S, Miao W, Bailie T, et al. Hair repigmentation associated with thalidomide use for the treatment of multiple myeloma. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215521.

- Rivera N, Boada A, Bielsa MI, et al. Hair repigmentation during immunotherapy treatment with an anti–programmed cell death 1 and anti–programmed cell death ligand 1 agent for lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1162-1165.

- Prasad S, Dougheney N, Hong A. Scalp hair repigmentation in the penumbral region of radiotherapy–a case series. Int J Radiol Radiat Ther. 2020;7:151-157.

- Adiga GU, Rehman KL, Wiernik PH. Permanent localized hair repigmentation following herpes zoster infection. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:569-570.

- Hanna E, Abadi R, Abbas O. Imiquimod in dermatology: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:831-844.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7-33.

- Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence‐based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472-492.

- Vetto JT, Hsueh EC, Gastman BR, et al. Guidance of sentinel lymph node biopsy decisions in patients with T1–T2 melanoma using gene expression profiling. Futur Oncol. 2019;15:1207-1217.

- Dummer R. Hair repigmentation in lentigo maligna. Lancet. 2001;357:598.

- Inzinger M, Massone C, Arzberger E, et al. Hair repigmentation in melanoma. Lancet. 2013;382:1224.

- Rahim RR, Husain A, Tobin DJ, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma presenting with localized hair repigmentation. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1371-1373.

- Tiger JB, Habeshian KA, Barton DT, et al. Repigmentation of hair associated with melanoma in situ of scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:E144-E145.

- Amann VC, Dummer R. Localized hair repigmentation in a 91-year-old woman. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:81-82.

- Chan C, Magro CM, Pham AK, et al. Spontaneous hair repigmentation in an 80-year-old man: a case of melanoma-associated hair repigmentation and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2019;41:671-674.

- Lackey AE, Glassman G, Grichnik J, et al. Repigmentation of gray hairs with lentigo maligna and response to topical imiquimod. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:1015-1017.

- Chew T, Pannell M, Jeeves A. Focal hair re-pigmentation associated with melanoma of the scalp. ANZ J Surg. 2019;90:1175-1176.

- López-Sánchez C, Collgros H. Hair repigmentation as a clue for scalp melanoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;61:179-180.

- Gessler J, Tejasvi T, Bresler SC. Repigmentation of scalp hair: a feature of early melanoma. Am J Med. 2023;136:E7-E8.

- Hasegawa T, Iino S, Kitakaze K, et al. Repigmentation of aging gray hair associated with unrecognized development and progression of amelanotic melanoma of the scalp: a physiological alert underlying hair rejuvenation. J Dermatol. 2021;48:E281-E283. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.15881

- D’Mello SAN, Finlay GJ, Baguley BC, et al. Signaling pathways in melanogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1144.

- Hachiya A, Kobayashi A, Ohuchi A, et al. The paracrine role of stem cell factor/c-kit signaling in the activation of human melanocytes in ultraviolet-B-induced pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:578-586.

- Slominski A, Wortsman J, Plonka PM, et al. Hair follicle pigmentation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:13-21.

- Falabella R. Vitiligo and the melanocyte reservoir. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:313.

- Seckin D, Yildiz A. Repigmentation and curling of hair after acitretin therapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:214-216.

- Dasanu CA, Mitsis D, Alexandrescu DT. Hair repigmentation associated with the use of lenalidomide: graying may not be an irreversible process! J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2013;19:165-169.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AI, Lowe PM. Hair repigmentation with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 immunotherapy: a novel hypothesis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:112-113. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4420

- Tintle SJ, Dabade TS, Kalish RA, et al. Repigmentation of hair following adalimumab therapy. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6fn0t1xz.

- Penzi LR, Manatis-Lornell A, Saavedra A, et al. Hair repigmentation associated with the use of brentuximab. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:563-565.

- Khaled A, Trojjets S, Zeglaoui F, et al. Repigmentation of the white hair after systemic corticosteroids for bullous pemphigoid. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2008;22:1018-1020.

- Cheng YP, Chen HJ, Chiu HC. Erlotinib-induced hair repigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E55-E57.

- Bellandi S, Amato L, Cipollini EM, et al. Repigmentation of hair after latanoprost therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2011;25:1485-1487.

- Read GM. Verapamil and hair colour change. Lancet. 1991;338:1520.

- Hampson JP, Donnelly A, Lewis‐Jones MS, et al. Tamoxifen‐induced hair colour change. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:483-484.

- Reynolds NJ, Crossley J, Ferguson I, et al. Darkening of white hair in Parkinson’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:317-318.

- Lovering S, Miao W, Bailie T, et al. Hair repigmentation associated with thalidomide use for the treatment of multiple myeloma. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016215521.

- Rivera N, Boada A, Bielsa MI, et al. Hair repigmentation during immunotherapy treatment with an anti–programmed cell death 1 and anti–programmed cell death ligand 1 agent for lung cancer. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1162-1165.

- Prasad S, Dougheney N, Hong A. Scalp hair repigmentation in the penumbral region of radiotherapy–a case series. Int J Radiol Radiat Ther. 2020;7:151-157.

- Adiga GU, Rehman KL, Wiernik PH. Permanent localized hair repigmentation following herpes zoster infection. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:569-570.

- Hanna E, Abadi R, Abbas O. Imiquimod in dermatology: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:831-844.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7-33.

Practice Points

- Localized repigmentation of the hair is a rare phenomenon that may indicate underlying melanoma.

- Careful clinicopathologic correlation is necessary to appropriately diagnose and manage this unusual presentation of melanoma.

Increased cancer in military pilots and ground crew: Pentagon

“Military aircrew and ground crew were overall more likely to be diagnosed with cancer, but less likely to die from cancer compared to the U.S. population,” the report concludes.

The study involved 156,050 aircrew and 737,891 ground crew. Participants were followed between 1992 and 2017. Both groups were predominantly male and non-Hispanic.

Data on cancer incidence and mortality for these two groups were compared with data from groups of similar age in the general population through use of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database of the National Cancer Institute.

For aircrew, the study found an 87% higher rate of melanoma, a 39% higher rate of thyroid cancer, a 16% higher rate of prostate cancer, and a 24% higher rate of cancer for all sites combined.

A higher rate of melanoma and prostate cancer among aircrew has been reported previously, but the increased rate of thyroid cancer is a new finding, the authors note.

The uptick in melanoma has also been reported in studies of civilian pilots and cabin crew. It has been attributed to exposure to hazardous ultraviolet and cosmic radiation.

For ground crew members, the analysis found a 19% higher rate of cancers of the brain and nervous system, a 15% higher rate of thyroid cancer, a 9% higher rate of melanoma and of kidney and renal pelvis cancers, and a 3% higher rate of cancer for all sites combined.

There is little to compare these findings with: This is the first time that cancer risk has been evaluated in such a large population of military ground crew.

Lower rates of cancer mortality

In contrast to the increase in cancer incidence, the report found a decrease in cancer mortality.

When compared with a demographically similar U.S. population, the mortality rate among aircrew was 56% lower for all cancer sites; for ground crew, the mortality rate was 35% lower.

However, the report authors emphasize that “it is important to note that the military study population was relatively young.”

The median age at the end of follow-up for the cancer incidence analysis was 41 years for aircrew and 26 years for ground crew. The median age at the end of follow-up for the cancer mortality analysis was 48 years for aircrew and 41 years for ground crew.

“Results may have differed if additional older former Service members had been included in the study, since cancer risk and mortality rates increase with age,” the authors comment.

Other studies have found an increase in deaths from melanoma as well as an increase in the incidence of melanoma. A meta-analysis published in 2019 in the British Journal of Dermatology found that airline pilots and cabin crew have about twice the risk of melanoma and other skin cancers than the general population. Pilots are also more likely to die from melanoma.

Further study underway

The findings on military air and ground crew come from phase 1 of a study that was required by Congress in the 2021 defense bill. Because the investigators found an increase in the incidence of cancer, phase 2 of the study is now necessary.

The report authors explain that phase 2 will consist of identifying the carcinogenic toxicants or hazardous materials associated with military flight operations; identifying operating environments that could be associated with increased amounts of ionizing and nonionizing radiation; identifying specific duties, dates of service, and types of aircraft flown that could have increased the risk for cancer; identifying duty locations associated with a higher incidence of cancers; identifying potential exposures through military service that are not related to aviation; and determining the appropriate age to begin screening military aircrew and ground crew for cancers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Military aircrew and ground crew were overall more likely to be diagnosed with cancer, but less likely to die from cancer compared to the U.S. population,” the report concludes.

The study involved 156,050 aircrew and 737,891 ground crew. Participants were followed between 1992 and 2017. Both groups were predominantly male and non-Hispanic.

Data on cancer incidence and mortality for these two groups were compared with data from groups of similar age in the general population through use of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database of the National Cancer Institute.

For aircrew, the study found an 87% higher rate of melanoma, a 39% higher rate of thyroid cancer, a 16% higher rate of prostate cancer, and a 24% higher rate of cancer for all sites combined.

A higher rate of melanoma and prostate cancer among aircrew has been reported previously, but the increased rate of thyroid cancer is a new finding, the authors note.

The uptick in melanoma has also been reported in studies of civilian pilots and cabin crew. It has been attributed to exposure to hazardous ultraviolet and cosmic radiation.

For ground crew members, the analysis found a 19% higher rate of cancers of the brain and nervous system, a 15% higher rate of thyroid cancer, a 9% higher rate of melanoma and of kidney and renal pelvis cancers, and a 3% higher rate of cancer for all sites combined.

There is little to compare these findings with: This is the first time that cancer risk has been evaluated in such a large population of military ground crew.

Lower rates of cancer mortality

In contrast to the increase in cancer incidence, the report found a decrease in cancer mortality.

When compared with a demographically similar U.S. population, the mortality rate among aircrew was 56% lower for all cancer sites; for ground crew, the mortality rate was 35% lower.

However, the report authors emphasize that “it is important to note that the military study population was relatively young.”

The median age at the end of follow-up for the cancer incidence analysis was 41 years for aircrew and 26 years for ground crew. The median age at the end of follow-up for the cancer mortality analysis was 48 years for aircrew and 41 years for ground crew.

“Results may have differed if additional older former Service members had been included in the study, since cancer risk and mortality rates increase with age,” the authors comment.

Other studies have found an increase in deaths from melanoma as well as an increase in the incidence of melanoma. A meta-analysis published in 2019 in the British Journal of Dermatology found that airline pilots and cabin crew have about twice the risk of melanoma and other skin cancers than the general population. Pilots are also more likely to die from melanoma.

Further study underway

The findings on military air and ground crew come from phase 1 of a study that was required by Congress in the 2021 defense bill. Because the investigators found an increase in the incidence of cancer, phase 2 of the study is now necessary.

The report authors explain that phase 2 will consist of identifying the carcinogenic toxicants or hazardous materials associated with military flight operations; identifying operating environments that could be associated with increased amounts of ionizing and nonionizing radiation; identifying specific duties, dates of service, and types of aircraft flown that could have increased the risk for cancer; identifying duty locations associated with a higher incidence of cancers; identifying potential exposures through military service that are not related to aviation; and determining the appropriate age to begin screening military aircrew and ground crew for cancers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Military aircrew and ground crew were overall more likely to be diagnosed with cancer, but less likely to die from cancer compared to the U.S. population,” the report concludes.

The study involved 156,050 aircrew and 737,891 ground crew. Participants were followed between 1992 and 2017. Both groups were predominantly male and non-Hispanic.

Data on cancer incidence and mortality for these two groups were compared with data from groups of similar age in the general population through use of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database of the National Cancer Institute.

For aircrew, the study found an 87% higher rate of melanoma, a 39% higher rate of thyroid cancer, a 16% higher rate of prostate cancer, and a 24% higher rate of cancer for all sites combined.

A higher rate of melanoma and prostate cancer among aircrew has been reported previously, but the increased rate of thyroid cancer is a new finding, the authors note.

The uptick in melanoma has also been reported in studies of civilian pilots and cabin crew. It has been attributed to exposure to hazardous ultraviolet and cosmic radiation.

For ground crew members, the analysis found a 19% higher rate of cancers of the brain and nervous system, a 15% higher rate of thyroid cancer, a 9% higher rate of melanoma and of kidney and renal pelvis cancers, and a 3% higher rate of cancer for all sites combined.

There is little to compare these findings with: This is the first time that cancer risk has been evaluated in such a large population of military ground crew.

Lower rates of cancer mortality

In contrast to the increase in cancer incidence, the report found a decrease in cancer mortality.

When compared with a demographically similar U.S. population, the mortality rate among aircrew was 56% lower for all cancer sites; for ground crew, the mortality rate was 35% lower.

However, the report authors emphasize that “it is important to note that the military study population was relatively young.”

The median age at the end of follow-up for the cancer incidence analysis was 41 years for aircrew and 26 years for ground crew. The median age at the end of follow-up for the cancer mortality analysis was 48 years for aircrew and 41 years for ground crew.

“Results may have differed if additional older former Service members had been included in the study, since cancer risk and mortality rates increase with age,” the authors comment.

Other studies have found an increase in deaths from melanoma as well as an increase in the incidence of melanoma. A meta-analysis published in 2019 in the British Journal of Dermatology found that airline pilots and cabin crew have about twice the risk of melanoma and other skin cancers than the general population. Pilots are also more likely to die from melanoma.

Further study underway

The findings on military air and ground crew come from phase 1 of a study that was required by Congress in the 2021 defense bill. Because the investigators found an increase in the incidence of cancer, phase 2 of the study is now necessary.

The report authors explain that phase 2 will consist of identifying the carcinogenic toxicants or hazardous materials associated with military flight operations; identifying operating environments that could be associated with increased amounts of ionizing and nonionizing radiation; identifying specific duties, dates of service, and types of aircraft flown that could have increased the risk for cancer; identifying duty locations associated with a higher incidence of cancers; identifying potential exposures through military service that are not related to aviation; and determining the appropriate age to begin screening military aircrew and ground crew for cancers.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Melanoma screening: Consensus statement offers greater clarity

That is why a group of expert panelists evaluated the existing evidence and a range of clinical scenarios to help clarify the optimal strategies for early detection and assessment of cutaneous melanoma.

Overall, the panelists agreed that a risk-stratified approach is likely the most appropriate strategy for melanoma screening and follow-up and supported the use of visual and dermoscopic examination. However, the panelists did not reach consensus on the role for gene expression profile (GEP) testing in clinical decision-making, citing the need for these assays to be validated in large randomized clinical trials.

In an accompanying editorial, two experts highlighted the importance of carefully evaluating the role of diagnostic tests.

“Diagnostic tests such as GEP must face critical scrutiny; if not, there are immediate concerns for patient care, such as the patient being erroneously informed that they do not have cancer or told that they do have cancer when they do not,” write Alan C. Geller, MPH, RN, from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and Marvin A. Weinstock, MD, PhD, from Brown University, Providence, R.I.

The consensus statement was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The need for guidance

Although focusing melanoma screening on higher-risk populations may be cost effective, compared with population-based screening, the major guidelines lack consistent guidance to support a risk-stratified approach to skin cancer screening and best practices on diagnosing cutaneous melanoma.

In the prebiopsy setting, the appropriate use of diagnostic tools for evaluating the need for biopsy remain poorly defined, and, in the post-biopsy setting, questions remain concerning the diagnostic accuracy of molecular techniques, diagnostic GEP testing, next-generation sequencing, and immunohistochemical assessment for various markers of melanoma.

To provide consensus recommendations on optimal screening practices, prebiopsy and postbiopsy diagnostics, and prognostic assessment of cutaneous melanoma, a group of 42 panelists voted on hypothetical scenarios via an emailed survey. The panel then came together for a consensus conference, which included 51 experts who discussed their approach to the various clinical case scenarios. Most attendees (45 of the 51) answered a follow-up survey for their final recommendations.

The panelists reached a consensus, with 70% agreement, to support a risk-stratified approach to melanoma screening in clinical settings and public screening events. The experts agreed that higher-risk individuals (those with a relative risk of 5 or greater) could be appropriately screened by a general dermatologist or pigmented lesion evaluation. Higher-risk individuals included those with severe skin damage from the sun, systemic immunosuppression, or a personal history of nonmelanoma or melanoma skin cancer.

Panelists agreed that those at general or lower risk (RR < 2) could be screened by a primary care provider or through regular self- or partner examinations, whereas those at moderate risk could be screened by their primary care clinician or general dermatologist. The experts observed “a shift in acceptance” of primary care physicians screening the general population, and an acknowledgement of the importance of self- and partner examinations as screening adjuncts for all populations.

In the prebiopsy setting, panelists reached consensus that visual and dermoscopic examination was appropriate for evaluating patients with “no new, changing, or unusual skin lesions or with a new lesion that is not visually concerning.”

The panelists also reached consensus that lesions deemed clinically suspicious for cancer or showing features of cancer on reflectance confocal microscopy should be biopsied. Although most respondents (86%) did not currently use epidermal tape stripping routinely, they agreed that, in a hypothetical situation where epidermal tape stripping was used, that lesions positive for PRAME or LINC should be biopsied.

In the postbiopsy setting, views on the use of GEP scores varied. Although panelists agreed that a low-risk prognostic GEP score should not outweigh concerning histologic features when patients are selected to undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), they did not reach consensus for imaging recommendations in the setting of a high-risk prognostic GEP score and low-risk histology and/or negative nodal status.

“The panelists await future, well-designed prospective studies to determine if use of these and newer technologies improves the care of patients with melanoma,” the panelists write.

In the editorial, Mr. Geller and Dr. Weinstock highlighted concerns about the cost and potential access issues associated with these newer technologies, given that the current cost of GEP testing exceeds $7,000.

The editorialists also emphasize that “going forward, the field should be advanced by tackling one of the more pressing, common, potentially morbid, and costly procedures – the prognostic use of sentinel lymph node biopsy.”

Of critical importance is “whether GEP can reduce morbidity and cost by safely reducing the number of SLNBs performed,” Mr. Geller and Dr. Weinstock write.

The funding for the administration and facilitation of the consensus development conference and the development of the manuscript was provided by Dermtech, in an unrestricted award overseen by the Melanoma Research Foundation and managed and executed at UPMC by the principal investigator. Several of the coauthors disclosed relationships with industry. Mr. Geller is a contributor to UptoDate for which he receives royalties. Dr. Weinstock receives consulting fees from AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

That is why a group of expert panelists evaluated the existing evidence and a range of clinical scenarios to help clarify the optimal strategies for early detection and assessment of cutaneous melanoma.

Overall, the panelists agreed that a risk-stratified approach is likely the most appropriate strategy for melanoma screening and follow-up and supported the use of visual and dermoscopic examination. However, the panelists did not reach consensus on the role for gene expression profile (GEP) testing in clinical decision-making, citing the need for these assays to be validated in large randomized clinical trials.

In an accompanying editorial, two experts highlighted the importance of carefully evaluating the role of diagnostic tests.

“Diagnostic tests such as GEP must face critical scrutiny; if not, there are immediate concerns for patient care, such as the patient being erroneously informed that they do not have cancer or told that they do have cancer when they do not,” write Alan C. Geller, MPH, RN, from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and Marvin A. Weinstock, MD, PhD, from Brown University, Providence, R.I.

The consensus statement was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The need for guidance

Although focusing melanoma screening on higher-risk populations may be cost effective, compared with population-based screening, the major guidelines lack consistent guidance to support a risk-stratified approach to skin cancer screening and best practices on diagnosing cutaneous melanoma.

In the prebiopsy setting, the appropriate use of diagnostic tools for evaluating the need for biopsy remain poorly defined, and, in the post-biopsy setting, questions remain concerning the diagnostic accuracy of molecular techniques, diagnostic GEP testing, next-generation sequencing, and immunohistochemical assessment for various markers of melanoma.

To provide consensus recommendations on optimal screening practices, prebiopsy and postbiopsy diagnostics, and prognostic assessment of cutaneous melanoma, a group of 42 panelists voted on hypothetical scenarios via an emailed survey. The panel then came together for a consensus conference, which included 51 experts who discussed their approach to the various clinical case scenarios. Most attendees (45 of the 51) answered a follow-up survey for their final recommendations.

The panelists reached a consensus, with 70% agreement, to support a risk-stratified approach to melanoma screening in clinical settings and public screening events. The experts agreed that higher-risk individuals (those with a relative risk of 5 or greater) could be appropriately screened by a general dermatologist or pigmented lesion evaluation. Higher-risk individuals included those with severe skin damage from the sun, systemic immunosuppression, or a personal history of nonmelanoma or melanoma skin cancer.

Panelists agreed that those at general or lower risk (RR < 2) could be screened by a primary care provider or through regular self- or partner examinations, whereas those at moderate risk could be screened by their primary care clinician or general dermatologist. The experts observed “a shift in acceptance” of primary care physicians screening the general population, and an acknowledgement of the importance of self- and partner examinations as screening adjuncts for all populations.

In the prebiopsy setting, panelists reached consensus that visual and dermoscopic examination was appropriate for evaluating patients with “no new, changing, or unusual skin lesions or with a new lesion that is not visually concerning.”

The panelists also reached consensus that lesions deemed clinically suspicious for cancer or showing features of cancer on reflectance confocal microscopy should be biopsied. Although most respondents (86%) did not currently use epidermal tape stripping routinely, they agreed that, in a hypothetical situation where epidermal tape stripping was used, that lesions positive for PRAME or LINC should be biopsied.

In the postbiopsy setting, views on the use of GEP scores varied. Although panelists agreed that a low-risk prognostic GEP score should not outweigh concerning histologic features when patients are selected to undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), they did not reach consensus for imaging recommendations in the setting of a high-risk prognostic GEP score and low-risk histology and/or negative nodal status.

“The panelists await future, well-designed prospective studies to determine if use of these and newer technologies improves the care of patients with melanoma,” the panelists write.

In the editorial, Mr. Geller and Dr. Weinstock highlighted concerns about the cost and potential access issues associated with these newer technologies, given that the current cost of GEP testing exceeds $7,000.

The editorialists also emphasize that “going forward, the field should be advanced by tackling one of the more pressing, common, potentially morbid, and costly procedures – the prognostic use of sentinel lymph node biopsy.”

Of critical importance is “whether GEP can reduce morbidity and cost by safely reducing the number of SLNBs performed,” Mr. Geller and Dr. Weinstock write.

The funding for the administration and facilitation of the consensus development conference and the development of the manuscript was provided by Dermtech, in an unrestricted award overseen by the Melanoma Research Foundation and managed and executed at UPMC by the principal investigator. Several of the coauthors disclosed relationships with industry. Mr. Geller is a contributor to UptoDate for which he receives royalties. Dr. Weinstock receives consulting fees from AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

That is why a group of expert panelists evaluated the existing evidence and a range of clinical scenarios to help clarify the optimal strategies for early detection and assessment of cutaneous melanoma.

Overall, the panelists agreed that a risk-stratified approach is likely the most appropriate strategy for melanoma screening and follow-up and supported the use of visual and dermoscopic examination. However, the panelists did not reach consensus on the role for gene expression profile (GEP) testing in clinical decision-making, citing the need for these assays to be validated in large randomized clinical trials.

In an accompanying editorial, two experts highlighted the importance of carefully evaluating the role of diagnostic tests.

“Diagnostic tests such as GEP must face critical scrutiny; if not, there are immediate concerns for patient care, such as the patient being erroneously informed that they do not have cancer or told that they do have cancer when they do not,” write Alan C. Geller, MPH, RN, from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and Marvin A. Weinstock, MD, PhD, from Brown University, Providence, R.I.

The consensus statement was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The need for guidance

Although focusing melanoma screening on higher-risk populations may be cost effective, compared with population-based screening, the major guidelines lack consistent guidance to support a risk-stratified approach to skin cancer screening and best practices on diagnosing cutaneous melanoma.

In the prebiopsy setting, the appropriate use of diagnostic tools for evaluating the need for biopsy remain poorly defined, and, in the post-biopsy setting, questions remain concerning the diagnostic accuracy of molecular techniques, diagnostic GEP testing, next-generation sequencing, and immunohistochemical assessment for various markers of melanoma.

To provide consensus recommendations on optimal screening practices, prebiopsy and postbiopsy diagnostics, and prognostic assessment of cutaneous melanoma, a group of 42 panelists voted on hypothetical scenarios via an emailed survey. The panel then came together for a consensus conference, which included 51 experts who discussed their approach to the various clinical case scenarios. Most attendees (45 of the 51) answered a follow-up survey for their final recommendations.

The panelists reached a consensus, with 70% agreement, to support a risk-stratified approach to melanoma screening in clinical settings and public screening events. The experts agreed that higher-risk individuals (those with a relative risk of 5 or greater) could be appropriately screened by a general dermatologist or pigmented lesion evaluation. Higher-risk individuals included those with severe skin damage from the sun, systemic immunosuppression, or a personal history of nonmelanoma or melanoma skin cancer.

Panelists agreed that those at general or lower risk (RR < 2) could be screened by a primary care provider or through regular self- or partner examinations, whereas those at moderate risk could be screened by their primary care clinician or general dermatologist. The experts observed “a shift in acceptance” of primary care physicians screening the general population, and an acknowledgement of the importance of self- and partner examinations as screening adjuncts for all populations.

In the prebiopsy setting, panelists reached consensus that visual and dermoscopic examination was appropriate for evaluating patients with “no new, changing, or unusual skin lesions or with a new lesion that is not visually concerning.”

The panelists also reached consensus that lesions deemed clinically suspicious for cancer or showing features of cancer on reflectance confocal microscopy should be biopsied. Although most respondents (86%) did not currently use epidermal tape stripping routinely, they agreed that, in a hypothetical situation where epidermal tape stripping was used, that lesions positive for PRAME or LINC should be biopsied.

In the postbiopsy setting, views on the use of GEP scores varied. Although panelists agreed that a low-risk prognostic GEP score should not outweigh concerning histologic features when patients are selected to undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), they did not reach consensus for imaging recommendations in the setting of a high-risk prognostic GEP score and low-risk histology and/or negative nodal status.

“The panelists await future, well-designed prospective studies to determine if use of these and newer technologies improves the care of patients with melanoma,” the panelists write.

In the editorial, Mr. Geller and Dr. Weinstock highlighted concerns about the cost and potential access issues associated with these newer technologies, given that the current cost of GEP testing exceeds $7,000.

The editorialists also emphasize that “going forward, the field should be advanced by tackling one of the more pressing, common, potentially morbid, and costly procedures – the prognostic use of sentinel lymph node biopsy.”

Of critical importance is “whether GEP can reduce morbidity and cost by safely reducing the number of SLNBs performed,” Mr. Geller and Dr. Weinstock write.

The funding for the administration and facilitation of the consensus development conference and the development of the manuscript was provided by Dermtech, in an unrestricted award overseen by the Melanoma Research Foundation and managed and executed at UPMC by the principal investigator. Several of the coauthors disclosed relationships with industry. Mr. Geller is a contributor to UptoDate for which he receives royalties. Dr. Weinstock receives consulting fees from AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Dermatologic Implications of Sleep Deprivation in the US Military

Sleep deprivation can increase emotional distress and mood disorders; reduce quality of life; and lead to cognitive, memory, and performance deficits.1 Military service predisposes members to disordered sleep due to the rigors of deployments and field training, such as long shifts, shift changes, stressful work environments, and time zone changes. Evidence shows that sleep deprivation is associated with cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, and some cancers.2 We explore multiple mechanisms by which sleep deprivation may affect the skin. We also review the potential impacts of sleep deprivation on specific topics in dermatology, including atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical attractiveness, wound healing, and skin cancer.

Sleep and Military Service

Approximately 35.2% of Americans experience short sleep duration, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as sleeping fewer than 7 hours per 24-hour period.3 Short sleep duration is even more common among individuals working in protective services and the military (50.4%).4 United States military service members experience multiple contributors to disordered sleep, including combat operations, shift work, psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.5 Bramoweth and Germain6 described the case of a 27-year-old man who served 2 combat tours as an infantryman in Afghanistan, during which time he routinely remained awake for more than 24 hours at a time due to night missions and extended operations. Even when he was not directly involved in combat operations, he was rarely able to keep a regular sleep schedule.6 Service members returning from deployment also report decreased sleep. In one study (N=2717), 43% of respondents reported short sleep duration (<7 hours of sleep per night) and 29% reported very short sleep duration (<6 hours of sleep per night).7 Even stateside, service members experience acute sleep deprivation during training.8

Sleep and Skin

The idea that skin conditions can affect quality of sleep is not controversial. Pruritus, pain, and emotional distress associated with different dermatologic conditions have all been implicated in adversely affecting sleep.9 Given the effects of sleep deprivation on other organ systems, it also can affect the skin. Possible mechanisms of action include negative effects of sleep deprivation on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, cutaneous barrier function, and immune function. First, the HPA axis activity follows a circadian rhythm.10 Activation outside of the bounds of this normal rhythm can have adverse effects on sleep. Alternatively, sleep deprivation and decreased sleep quality can negatively affect the HPA axis.10 These changes can adversely affect cutaneous barrier and immune function.11 Cutaneous barrier function is vitally important in the context of inflammatory dermatologic conditions. Transepidermal water loss, a measurement used to estimate cutaneous barrier function, is increased by sleep deprivation.12 Finally, the cutaneous immune system is an important component of inflammatory dermatologic conditions, cancer immune surveillance, and wound healing, and it also is negatively impacted by sleep deprivation.13 This framework of sleep deprivation affecting the HPA axis, cutaneous barrier function, and cutaneous immune function will help to guide the following discussion on the effects of decreased sleep on specific dermatologic conditions.

Atopic Dermatitis—Individuals with AD are at higher odds of having insomnia, fatigue, and overall poorer health status, including more sick days and increased visits to a physician.14 Additionally, it is possible that the relationship between AD and sleep is not unidirectional. Chang and Chiang15 discussed the possibility of sleep disturbances contributing to AD flares and listed 3 possible mechanisms by which sleep disturbance could potentially flare AD: exacerbation of the itch-scratch cycle; changes in the immune system, including a possible shift to helper T cell (TH2) dominance; and worsening of chronic stress in patients with AD. These changes may lead to a vicious cycle of impaired sleep and AD exacerbations. It may be helpful to view sleep impairment and AD as comorbid conditions requiring co-management for optimal outcomes. This perspective has military relevance because even without considering sleep deprivation, deployment and field conditions are known to increase the risk for AD flares.16

Psoriasis—Psoriasis also may have a bidirectional relationship with sleep. A study utilizing data from the Nurses’ Health Study showed that working a night shift increased the risk for psoriasis.17 Importantly, this connection is associative and not causative. It is possible that other factors in those who worked night shifts such as probable decreased UV exposure or reported increased body mass index played a role. Studies using psoriasis mice models have shown increased inflammation with sleep deprivation.18 Another possible connection is the effect of sleep deprivation on the gut microbiome. Sleep dysfunction is associated with altered gut bacteria ratios, and similar gut bacteria ratios were found in patients with psoriasis, which may indicate an association between sleep deprivation and psoriasis disease progression.19 There also is an increased association of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with psoriasis compared to the general population.20 Fortunately, the rate of consultations for psoriasis in deployed soldiers in the last several conflicts has been quite low, making up only 2.1% of diagnosed dermatologic conditions,21 which is because service members with moderate to severe psoriasis likely will not be deployed.

Alopecia Areata—Alopecia areata also may be associated with sleep deprivation. A large retrospective cohort study looking at the risk for alopecia in patients with sleep disorders showed that a sleep disorder was an independent risk factor for alopecia areata.22 The impact of sleep on the HPA axis portrays a possible mechanism for the negative effects of sleep deprivation on the immune system. Interestingly, in this study, the association was strongest for the 0- to 24-year-old age group. According to the 2020 demographics profile of the military community, 45% of active-duty personnel are 25 years or younger.23 Fortunately, although alopecia areata can be a distressing condition, it should not have much effect on military readiness, as most individuals with this diagnosis are still deployable.

Physical Appearance—

Wound Healing—Wound healing is of particular importance to the health of military members. Research is suggestive but not definitive of the relationship between sleep and wound healing. One intriguing study looked at the healing of blisters induced via suction in well-rested and sleep-deprived individuals. The results showed a difference, with the sleep-deprived individuals taking approximately 1 day longer to heal.13 This has some specific relevance to the military, as friction blisters can be common.30 A cross-sectional survey looking at a group of service members deployed in Iraq showed a prevalence of foot friction blisters of 33%, with 11% of individuals requiring medical care.31 Although this is an interesting example, it is not necessarily applicable to full-thickness wounds. A study utilizing rat models did not identify any differences between sleep-deprived and well-rested models in the healing of punch biopsy sites.32

Skin Cancer—Altered circadian rhythms resulting in changes in melatonin levels, changes in circadian rhythm–related gene pathways, and immunologic changes have been proposed as possible contributing mechanisms for the observed increased risk for skin cancers in military and civilian pilots.33,34 One study showed that UV-related erythema resolved quicker in well-rested individuals compared with those with short sleep duration, which could represent more efficient DNA repair given the relationship between UV-associated erythema and DNA damage and repair.35 Another study looking at circadian changes in the repair of UV-related DNA damage showed that mice exposed to UV radiation in the early morning had higher rates of squamous cell carcinoma than those exposed in the afternoon.36 However, a large cohort study using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II did not support a positive connection between short sleep duration and skin cancer; rather, it showed that a short sleep duration was associated with a decreased risk for melanoma and basal cell carcinoma, with no effect noted for squamous cell carcinoma.37 This does not support a positive association between short sleep duration and skin cancer and in some cases actually suggests a negative association.

Final Thoughts

Although more research is needed, there is evidence that sleep deprivation can negatively affect the skin. Randomized controlled trials looking at groups of individuals with specific dermatologic conditions with a very short sleep duration group (<6 hours of sleep per night), short sleep duration group (<7 hours of sleep per night), and a well-rested group (>7 hours of sleep per night) could be very helpful in this endeavor. Possible mechanisms include the HPA axis, immune system, and skin barrier function that are associated with sleep deprivation. Specific dermatologic conditions that may be affected by sleep deprivation include AD, psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical appearance, wound healing, and skin cancer. The impact of sleep deprivation on dermatologic conditions is particularly relevant to the military, as service members are at an increased risk for short sleep duration. It is possible that improving sleep may lead to better disease control for many dermatologic conditions.

- Carskadon M, Dement WC. Cumulative effects of sleep restriction on daytime sleepiness. Psychophysiology. 1981;18:107-113.

- Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;19;9:151-161.

- Sleep and sleep disorders. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Reviewed September 12, 2022. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html

- Khubchandani J, Price JH. Short sleep duration in working American adults, 2010-2018. J Community Health. 2020;45:219-227.

- Good CH, Brager AJ, Capaldi VF, et al. Sleep in the United States military. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:176-191.

- Bramoweth AD, Germain A. Deployment-related insomnia in military personnel and veterans. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:401.

- Luxton DD, Greenburg D, Ryan J, et al. Prevalence and impact of short sleep duration in redeployed OIF soldiers. Sleep. 2011;34:1189-1195.

- Crowley SK, Wilkinson LL, Burroughs EL, et al. Sleep during basic combat training: a qualitative study. Mil Med. 2012;177:823-828.

- Spindler M, Przybyłowicz K, Hawro M, et al. Sleep disturbance in adult dermatologic patients: a cross-sectional study on prevalence, burden, and associated factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:910-922.

- Guyon A, Balbo M, Morselli LL, et al. Adverse effects of two nights of sleep restriction on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:2861-2868.

- Lin TK, Zhong L, Santiago JL. Association between stress and the HPA axis in the atopic dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2131.

- Pinnagoda J, Tupker RA, Agner T, et al. Guidelines for transepidermal water loss (TEWL) measurement. a report from theStandardization Group of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:164-178.

- Smith TJ, Wilson MA, Karl JP, et al. Impact of sleep restriction on local immune response and skin barrier restoration with and without “multinutrient” nutrition intervention. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2018;124:190-200.

- Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, et al. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:56-66.

- Chang YS, Chiang BL. Sleep disorders and atopic dermatitis: a 2-way street? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1033-1040.

- Riegleman KL, Farnsworth GS, Wong EB. Atopic dermatitis in the US military. Cutis. 2019;104:144-147.

- Li WQ, Qureshi AA, Schernhammer ES, et al. Rotating night-shift work and risk of psoriasis in US women. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:565-567.

- Hirotsu C, Rydlewski M, Araújo MS, et al. Sleep loss and cytokines levels in an experimental model of psoriasis. PLoS One. 2012;7:E51183.

- Myers B, Vidhatha R, Nicholas B, et al. Sleep and the gut microbiome in psoriasis: clinical implications for disease progression and the development of cardiometabolic comorbidities. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2021;6:27-37.

- Gupta MA, Simpson FC, Gupta AK. Psoriasis and sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;29:63-75.

- Gelman AB, Norton SA, Valdes-Rodriguez R, et al. A review of skin conditions in modern warfare and peacekeeping operations. Mil Med. 2015;180:32-37.