User login

Long COVID doubles risk of some serious outcomes in children, teens

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that

Heart inflammation; a blood clot in the lung; or a blood clot in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis were the most common bad outcomes in a new study. Even though the risk was higher for these and some other serious events, the overall numbers were small.

“Many of these conditions were rare or uncommon among children in this analysis, but even a small increase in these conditions is notable,” a CDC new release stated.

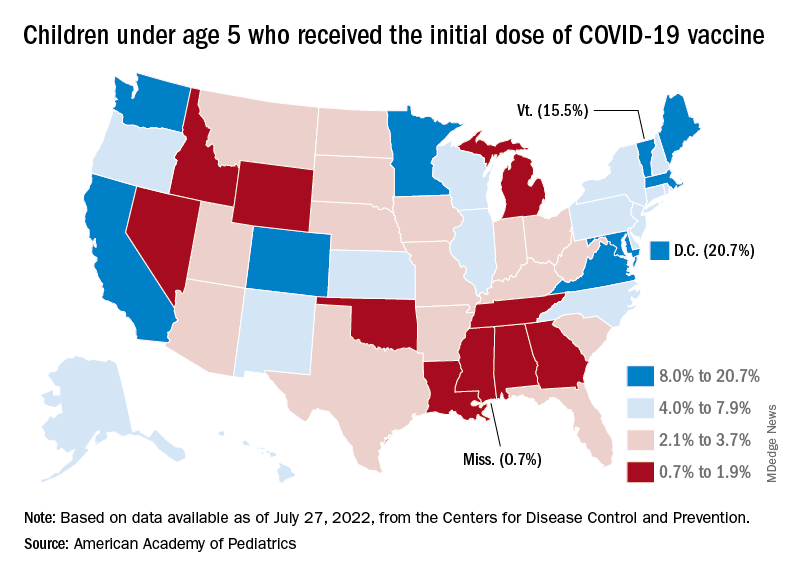

The investigators said their findings stress the importance of COVID-19 vaccination in Americans under the age of 18.

The study was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Less is known about long COVID in children

Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues noted that most research on long COVID to date has been done in adults, so little information is available about the risks to Americans ages 17 and younger.

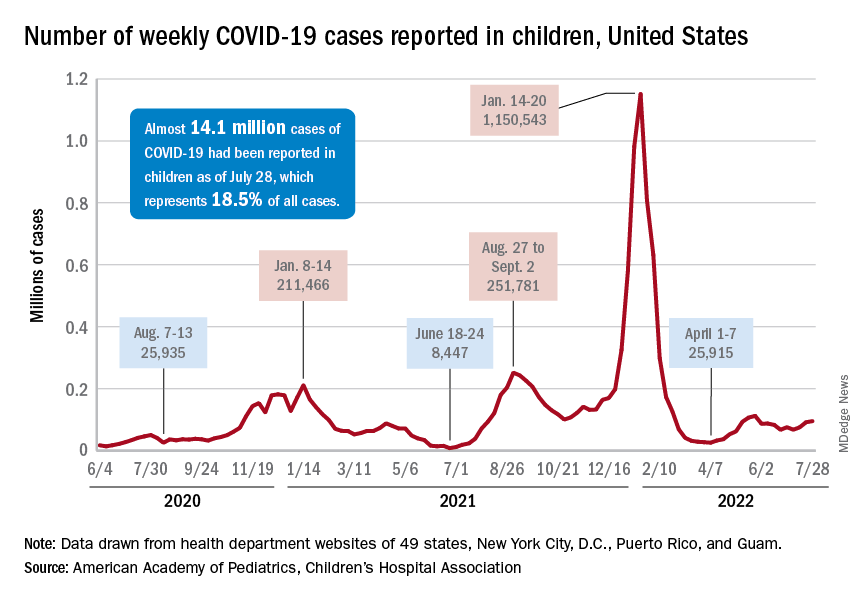

To learn more, they compared post–COVID-19 symptoms and conditions between 781,419 children and teenagers with confirmed COVID-19 to another 2,344,257 without COVID-19. They looked at medical claims and laboratory data for these children and teenagers from March 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2022, to see who got any of 15 specific outcomes linked to long COVID-19.

Long COVID was defined as a condition where symptoms that last for or begin at least 4 weeks after a COVID-19 diagnosis.

Compared to children with no history of a COVID-19 diagnosis, the long COVID-19 group was 101% more likely to have an acute pulmonary embolism, 99% more likely to have myocarditis or cardiomyopathy, 87% more likely to have a venous thromboembolic event, 32% more likely to have acute and unspecified renal failure, and 23% more likely to have type 1 diabetes.

“This report points to the fact that the risks of COVID infection itself, both in terms of the acute effects, MIS-C [multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children], as well as the long-term effects, are real, are concerning, and are potentially very serious,” said Stuart Berger, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery.

“The message that we should take away from this is that we should be very keen on all the methods of prevention for COVID, especially the vaccine,” said Dr. Berger, chief of cardiology in the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

A ‘wake-up call’

The study findings are “sobering” and are “a reminder of the seriousness of COVID infection,” says Gregory Poland, MD, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“When you look in particular at the more serious complications from COVID in this young age group, those are life-altering complications that will have consequences and ramifications throughout their lives,” he said.

“I would take this as a serious wake-up call to parents [at a time when] the immunization rates in younger children are so pitifully low,” Dr. Poland said.

Still early days

The study is suggestive but not definitive, said Peter Katona, MD, professor of medicine and infectious diseases expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

It’s still too early to draw conclusions about long COVID, including in children, because many questions remain, he said: Should long COVID be defined as symptoms at 1 month or 3 months after infection? How do you define brain fog?

Dr. Katona and colleagues are studying long COVID intervention among students at UCLA to answer some of these questions, including the incidence and effect of early intervention.

The study had “at least seven limitations,” the researchers noted. Among them was the use of medical claims data that noted long COVID outcomes but not how severe they were; some people in the no COVID group might have had the illness but not been diagnosed; and the researchers did not adjust for vaccination status.

Dr. Poland noted that the study was done during surges in COVID variants including Delta and Omicron. In other words, any long COVID effects linked to more recent variants such as BA.5 or BA.2.75 are unknown.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that

Heart inflammation; a blood clot in the lung; or a blood clot in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis were the most common bad outcomes in a new study. Even though the risk was higher for these and some other serious events, the overall numbers were small.

“Many of these conditions were rare or uncommon among children in this analysis, but even a small increase in these conditions is notable,” a CDC new release stated.

The investigators said their findings stress the importance of COVID-19 vaccination in Americans under the age of 18.

The study was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Less is known about long COVID in children

Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues noted that most research on long COVID to date has been done in adults, so little information is available about the risks to Americans ages 17 and younger.

To learn more, they compared post–COVID-19 symptoms and conditions between 781,419 children and teenagers with confirmed COVID-19 to another 2,344,257 without COVID-19. They looked at medical claims and laboratory data for these children and teenagers from March 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2022, to see who got any of 15 specific outcomes linked to long COVID-19.

Long COVID was defined as a condition where symptoms that last for or begin at least 4 weeks after a COVID-19 diagnosis.

Compared to children with no history of a COVID-19 diagnosis, the long COVID-19 group was 101% more likely to have an acute pulmonary embolism, 99% more likely to have myocarditis or cardiomyopathy, 87% more likely to have a venous thromboembolic event, 32% more likely to have acute and unspecified renal failure, and 23% more likely to have type 1 diabetes.

“This report points to the fact that the risks of COVID infection itself, both in terms of the acute effects, MIS-C [multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children], as well as the long-term effects, are real, are concerning, and are potentially very serious,” said Stuart Berger, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery.

“The message that we should take away from this is that we should be very keen on all the methods of prevention for COVID, especially the vaccine,” said Dr. Berger, chief of cardiology in the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

A ‘wake-up call’

The study findings are “sobering” and are “a reminder of the seriousness of COVID infection,” says Gregory Poland, MD, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“When you look in particular at the more serious complications from COVID in this young age group, those are life-altering complications that will have consequences and ramifications throughout their lives,” he said.

“I would take this as a serious wake-up call to parents [at a time when] the immunization rates in younger children are so pitifully low,” Dr. Poland said.

Still early days

The study is suggestive but not definitive, said Peter Katona, MD, professor of medicine and infectious diseases expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

It’s still too early to draw conclusions about long COVID, including in children, because many questions remain, he said: Should long COVID be defined as symptoms at 1 month or 3 months after infection? How do you define brain fog?

Dr. Katona and colleagues are studying long COVID intervention among students at UCLA to answer some of these questions, including the incidence and effect of early intervention.

The study had “at least seven limitations,” the researchers noted. Among them was the use of medical claims data that noted long COVID outcomes but not how severe they were; some people in the no COVID group might have had the illness but not been diagnosed; and the researchers did not adjust for vaccination status.

Dr. Poland noted that the study was done during surges in COVID variants including Delta and Omicron. In other words, any long COVID effects linked to more recent variants such as BA.5 or BA.2.75 are unknown.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that

Heart inflammation; a blood clot in the lung; or a blood clot in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis were the most common bad outcomes in a new study. Even though the risk was higher for these and some other serious events, the overall numbers were small.

“Many of these conditions were rare or uncommon among children in this analysis, but even a small increase in these conditions is notable,” a CDC new release stated.

The investigators said their findings stress the importance of COVID-19 vaccination in Americans under the age of 18.

The study was published online in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Less is known about long COVID in children

Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues noted that most research on long COVID to date has been done in adults, so little information is available about the risks to Americans ages 17 and younger.

To learn more, they compared post–COVID-19 symptoms and conditions between 781,419 children and teenagers with confirmed COVID-19 to another 2,344,257 without COVID-19. They looked at medical claims and laboratory data for these children and teenagers from March 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2022, to see who got any of 15 specific outcomes linked to long COVID-19.

Long COVID was defined as a condition where symptoms that last for or begin at least 4 weeks after a COVID-19 diagnosis.

Compared to children with no history of a COVID-19 diagnosis, the long COVID-19 group was 101% more likely to have an acute pulmonary embolism, 99% more likely to have myocarditis or cardiomyopathy, 87% more likely to have a venous thromboembolic event, 32% more likely to have acute and unspecified renal failure, and 23% more likely to have type 1 diabetes.

“This report points to the fact that the risks of COVID infection itself, both in terms of the acute effects, MIS-C [multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children], as well as the long-term effects, are real, are concerning, and are potentially very serious,” said Stuart Berger, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery.

“The message that we should take away from this is that we should be very keen on all the methods of prevention for COVID, especially the vaccine,” said Dr. Berger, chief of cardiology in the department of pediatrics at Northwestern University in Chicago.

A ‘wake-up call’

The study findings are “sobering” and are “a reminder of the seriousness of COVID infection,” says Gregory Poland, MD, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“When you look in particular at the more serious complications from COVID in this young age group, those are life-altering complications that will have consequences and ramifications throughout their lives,” he said.

“I would take this as a serious wake-up call to parents [at a time when] the immunization rates in younger children are so pitifully low,” Dr. Poland said.

Still early days

The study is suggestive but not definitive, said Peter Katona, MD, professor of medicine and infectious diseases expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

It’s still too early to draw conclusions about long COVID, including in children, because many questions remain, he said: Should long COVID be defined as symptoms at 1 month or 3 months after infection? How do you define brain fog?

Dr. Katona and colleagues are studying long COVID intervention among students at UCLA to answer some of these questions, including the incidence and effect of early intervention.

The study had “at least seven limitations,” the researchers noted. Among them was the use of medical claims data that noted long COVID outcomes but not how severe they were; some people in the no COVID group might have had the illness but not been diagnosed; and the researchers did not adjust for vaccination status.

Dr. Poland noted that the study was done during surges in COVID variants including Delta and Omicron. In other words, any long COVID effects linked to more recent variants such as BA.5 or BA.2.75 are unknown.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM THE MMWR

‘Children are not little adults’ and need special protection during heat waves

After more than a week of record-breaking temperatures across much of the country, public health experts are cautioning that children are more susceptible to heat illness than adults are – even more so when they’re on the athletic field, living without air conditioning, or waiting in a parked car.

Cases of heat-related illness are rising with average air temperatures, and experts say almost half of those getting sick are children. The reason is twofold: Children’s bodies have more trouble regulating temperature than do those of adults, and they rely on adults to help protect them from overheating.

Parents, coaches, and other caretakers, who can experience the same heat very differently from the way children do, may struggle to identify a dangerous situation or catch the early symptoms of heat-related illness in children.

“Children are not little adults,” said Dr. Aaron Bernstein, a pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Jan Null, a meteorologist in California, recalled being surprised at the effect of heat in a car. It was 86 degrees on a July afternoon more than 2 decades ago when an infant in San Jose was forgotten in a parked car and died of heatstroke.

Mr. Null said a reporter asked him after the death, “How hot could it have gotten in that car?”

Mr. Null’s research with two emergency doctors at Stanford University eventually produced a startling answer. Within an hour, the temperature in that car could have exceeded 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Their work revealed that a quick errand can be dangerous for a child left behind in the car – even for less than 15 minutes, even with the windows cracked, and even on a mild day.

As record heat becomes more frequent, posing serious risks even to healthy adults, the number of cases of heat-related illnesses has gone up, including among children. Those most at risk are young children in parked vehicles and adolescents returning to school and participating in sports during the hottest days of the year.

More than 9,000 high school athletes are treated for heat-related illnesses every year.

Heat-related illnesses occur when exposure to high temperatures and humidity, which can be intensified by physical exertion, overwhelms the body’s ability to cool itself. Cases range from mild, like benign heat rashes in infants, to more serious, when the body’s core temperature increases. That can lead to life-threatening instances of heatstroke, diagnosed once the body temperature rises above 104 degrees, potentially causing organ failure.

Prevention is key. Experts emphasize that drinking plenty of water, avoiding the outdoors during the hot midday and afternoon hours, and taking it slow when adjusting to exercise are the most effective ways to avoid getting sick.

Children’s bodies take longer to increase sweat production and otherwise acclimatize in a warm environment than adults’ do, research shows. Young children are more susceptible to dehydration because a larger percentage of their body weight is water.

Infants and younger children have more trouble regulating their body temperature, in part because they often don’t recognize when they should drink more water or remove clothing to cool down. A 1995 study showed that young children who spent 30 minutes in a 95-degree room saw their core temperatures rise significantly higher and faster than their mothers’ – even though they sweat more than adults do relative to their size.

Pediatricians advise caretakers to monitor how much water children consume and encourage them to drink before they ask for it. Thirst indicates the body is already dehydrated.

They should dress children in light-colored, lightweight clothes; limit outdoor time during the hottest hours; and look for ways to cool down, such as by visiting an air-conditioned place like a library, taking a cool bath, or going for a swim.

To address the risks to student athletes, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association recommends that high school athletes acclimatize by gradually building their activity over the course of 2 weeks when returning to their sport for a new season – including by slowly stepping up the amount of any protective equipment they wear.

“You’re gradually increasing that intensity over a week to 2 weeks so your body can get used to the heat,” said Kathy Dieringer, president of NATA.

Warning signs and solutions

Experts note a flushed face, fatigue, muscle cramps, headache, dizziness, vomiting, and a lot of sweating are among the symptoms of heat exhaustion, which can develop into heatstroke if untreated. A doctor should be notified if symptoms worsen, such as if the child seems disoriented or cannot drink.

Taking immediate steps to cool a child experiencing heat exhaustion or heatstroke is critical. The child should be taken to a shaded or cool area; be given cool fluids with salt, like sports drinks; and have any sweaty or heavy garments removed.

For adolescents, being submerged in an ice bath is the most effective way to cool the body, while younger children can be wrapped in cold, wet towels or misted with lukewarm water and placed in front of a fan.

Although children’s deaths in parked cars have been well documented, the tragic incidents continue to occur. According to federal statistics, 23 children died of vehicular heatstroke in 2021. Mr. Null, who collects his own data, said 13 children have died so far this year.

Caretakers should never leave children alone in a parked car, Mr. Null said. Take steps to prevent young children from entering the car themselves and becoming trapped, including locking the car while it’s parked at home.

More than half of cases of vehicular pediatric heatstroke occur because a caretaker accidentally left a child behind, he said. While in-car technology reminding adults to check their back seats has become more common, only a fraction of vehicles have it, requiring parents to come up with their own methods, like leaving a stuffed animal in the front seat.

The good news, Mr. Null said, is that simple behavioral changes can protect youngsters. “This is preventable in 100% of the cases,” he said.

A lopsided risk

People living in low-income areas fare worse when temperatures climb. Access to air conditioning, which includes the ability to afford the electricity bill, is a serious health concern.

A study of heat in urban areas released last year showed that low-income neighborhoods and communities of color experience much higher temperatures than those of wealthier, White residents. In more impoverished areas during the summer, temperatures can be as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer.

The study’s authors said their findings in the United States reflect that “the legacy of redlining looms large,” referring to a federal housing policy that refused to insure mortgages in or near predominantly Black neighborhoods.

“These areas have less tree canopy, more streets, and higher building densities, meaning that in addition to their other racist outcomes, redlining policies directly codified into law existing disparity in urban land use and reinforced urban design choices that magnify urban heating into the present,” they concluded.

Dr. Bernstein, who leads Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment, coauthored a commentary in JAMA arguing that advancing health equity is critical to action on climate change.

The center works with front-line health clinics to help their predominantly low-income patients respond to the health impacts of climate change. Federally backed clinics alone provide care to about 30 million Americans, including many children, he said.

Dr. Bernstein also recently led a nationwide study that found that from May through September, days with higher temperatures are associated with more visits to children’s hospital emergency rooms. Many visits were more directly linked to heat, although the study also pointed to how high temperatures can exacerbate existing health conditions such as neurological disorders.

“Children are more vulnerable to climate change through how these climate shocks reshape the world in which they grow up,” Dr. Bernstein said.

Helping people better understand the health risks of extreme heat and how to protect themselves and their families are among the public health system’s major challenges, experts said.

The National Weather Service’s heat alert system is mainly based on the heat index, a measure of how hot it feels when relative humidity is factored in with air temperature.

But the alerts are not related to effects on health, said Kathy Baughman McLeod, director of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center. By the time temperatures rise to the level that a weather alert is issued, many vulnerable people – like children, pregnant women, and the elderly – may already be experiencing heat exhaustion or heatstroke.

The center developed a new heat alert system, which is being tested in Seville, Spain, historically one of the hottest cities in Europe.

The system marries metrics such as air temperature and humidity with public health data to categorize heat waves and, when they are serious enough, give them names – making it easier for people to understand heat as an environmental threat that requires prevention measures.

The categories are determined through a metric known as excess deaths, which compares how many people died on a day with the forecast temperature versus an average day. That may help health officials understand how severe a heat wave is expected to be and make informed recommendations to the public based on risk factors such as age or medical history.

The health-based alert system would also allow officials to target caretakers of children and seniors through school systems, preschools, and senior centers, Ms. Baughman McLeod said.

Giving people better ways to conceptualize heat is critical, she said.

“It’s not dramatic. It doesn’t rip the roof off of your house,” Ms. Baughman McLeod said. “It’s silent and invisible.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

After more than a week of record-breaking temperatures across much of the country, public health experts are cautioning that children are more susceptible to heat illness than adults are – even more so when they’re on the athletic field, living without air conditioning, or waiting in a parked car.

Cases of heat-related illness are rising with average air temperatures, and experts say almost half of those getting sick are children. The reason is twofold: Children’s bodies have more trouble regulating temperature than do those of adults, and they rely on adults to help protect them from overheating.

Parents, coaches, and other caretakers, who can experience the same heat very differently from the way children do, may struggle to identify a dangerous situation or catch the early symptoms of heat-related illness in children.

“Children are not little adults,” said Dr. Aaron Bernstein, a pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Jan Null, a meteorologist in California, recalled being surprised at the effect of heat in a car. It was 86 degrees on a July afternoon more than 2 decades ago when an infant in San Jose was forgotten in a parked car and died of heatstroke.

Mr. Null said a reporter asked him after the death, “How hot could it have gotten in that car?”

Mr. Null’s research with two emergency doctors at Stanford University eventually produced a startling answer. Within an hour, the temperature in that car could have exceeded 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Their work revealed that a quick errand can be dangerous for a child left behind in the car – even for less than 15 minutes, even with the windows cracked, and even on a mild day.

As record heat becomes more frequent, posing serious risks even to healthy adults, the number of cases of heat-related illnesses has gone up, including among children. Those most at risk are young children in parked vehicles and adolescents returning to school and participating in sports during the hottest days of the year.

More than 9,000 high school athletes are treated for heat-related illnesses every year.

Heat-related illnesses occur when exposure to high temperatures and humidity, which can be intensified by physical exertion, overwhelms the body’s ability to cool itself. Cases range from mild, like benign heat rashes in infants, to more serious, when the body’s core temperature increases. That can lead to life-threatening instances of heatstroke, diagnosed once the body temperature rises above 104 degrees, potentially causing organ failure.

Prevention is key. Experts emphasize that drinking plenty of water, avoiding the outdoors during the hot midday and afternoon hours, and taking it slow when adjusting to exercise are the most effective ways to avoid getting sick.

Children’s bodies take longer to increase sweat production and otherwise acclimatize in a warm environment than adults’ do, research shows. Young children are more susceptible to dehydration because a larger percentage of their body weight is water.

Infants and younger children have more trouble regulating their body temperature, in part because they often don’t recognize when they should drink more water or remove clothing to cool down. A 1995 study showed that young children who spent 30 minutes in a 95-degree room saw their core temperatures rise significantly higher and faster than their mothers’ – even though they sweat more than adults do relative to their size.

Pediatricians advise caretakers to monitor how much water children consume and encourage them to drink before they ask for it. Thirst indicates the body is already dehydrated.

They should dress children in light-colored, lightweight clothes; limit outdoor time during the hottest hours; and look for ways to cool down, such as by visiting an air-conditioned place like a library, taking a cool bath, or going for a swim.

To address the risks to student athletes, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association recommends that high school athletes acclimatize by gradually building their activity over the course of 2 weeks when returning to their sport for a new season – including by slowly stepping up the amount of any protective equipment they wear.

“You’re gradually increasing that intensity over a week to 2 weeks so your body can get used to the heat,” said Kathy Dieringer, president of NATA.

Warning signs and solutions

Experts note a flushed face, fatigue, muscle cramps, headache, dizziness, vomiting, and a lot of sweating are among the symptoms of heat exhaustion, which can develop into heatstroke if untreated. A doctor should be notified if symptoms worsen, such as if the child seems disoriented or cannot drink.

Taking immediate steps to cool a child experiencing heat exhaustion or heatstroke is critical. The child should be taken to a shaded or cool area; be given cool fluids with salt, like sports drinks; and have any sweaty or heavy garments removed.

For adolescents, being submerged in an ice bath is the most effective way to cool the body, while younger children can be wrapped in cold, wet towels or misted with lukewarm water and placed in front of a fan.

Although children’s deaths in parked cars have been well documented, the tragic incidents continue to occur. According to federal statistics, 23 children died of vehicular heatstroke in 2021. Mr. Null, who collects his own data, said 13 children have died so far this year.

Caretakers should never leave children alone in a parked car, Mr. Null said. Take steps to prevent young children from entering the car themselves and becoming trapped, including locking the car while it’s parked at home.

More than half of cases of vehicular pediatric heatstroke occur because a caretaker accidentally left a child behind, he said. While in-car technology reminding adults to check their back seats has become more common, only a fraction of vehicles have it, requiring parents to come up with their own methods, like leaving a stuffed animal in the front seat.

The good news, Mr. Null said, is that simple behavioral changes can protect youngsters. “This is preventable in 100% of the cases,” he said.

A lopsided risk

People living in low-income areas fare worse when temperatures climb. Access to air conditioning, which includes the ability to afford the electricity bill, is a serious health concern.

A study of heat in urban areas released last year showed that low-income neighborhoods and communities of color experience much higher temperatures than those of wealthier, White residents. In more impoverished areas during the summer, temperatures can be as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer.

The study’s authors said their findings in the United States reflect that “the legacy of redlining looms large,” referring to a federal housing policy that refused to insure mortgages in or near predominantly Black neighborhoods.

“These areas have less tree canopy, more streets, and higher building densities, meaning that in addition to their other racist outcomes, redlining policies directly codified into law existing disparity in urban land use and reinforced urban design choices that magnify urban heating into the present,” they concluded.

Dr. Bernstein, who leads Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment, coauthored a commentary in JAMA arguing that advancing health equity is critical to action on climate change.

The center works with front-line health clinics to help their predominantly low-income patients respond to the health impacts of climate change. Federally backed clinics alone provide care to about 30 million Americans, including many children, he said.

Dr. Bernstein also recently led a nationwide study that found that from May through September, days with higher temperatures are associated with more visits to children’s hospital emergency rooms. Many visits were more directly linked to heat, although the study also pointed to how high temperatures can exacerbate existing health conditions such as neurological disorders.

“Children are more vulnerable to climate change through how these climate shocks reshape the world in which they grow up,” Dr. Bernstein said.

Helping people better understand the health risks of extreme heat and how to protect themselves and their families are among the public health system’s major challenges, experts said.

The National Weather Service’s heat alert system is mainly based on the heat index, a measure of how hot it feels when relative humidity is factored in with air temperature.

But the alerts are not related to effects on health, said Kathy Baughman McLeod, director of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center. By the time temperatures rise to the level that a weather alert is issued, many vulnerable people – like children, pregnant women, and the elderly – may already be experiencing heat exhaustion or heatstroke.

The center developed a new heat alert system, which is being tested in Seville, Spain, historically one of the hottest cities in Europe.

The system marries metrics such as air temperature and humidity with public health data to categorize heat waves and, when they are serious enough, give them names – making it easier for people to understand heat as an environmental threat that requires prevention measures.

The categories are determined through a metric known as excess deaths, which compares how many people died on a day with the forecast temperature versus an average day. That may help health officials understand how severe a heat wave is expected to be and make informed recommendations to the public based on risk factors such as age or medical history.

The health-based alert system would also allow officials to target caretakers of children and seniors through school systems, preschools, and senior centers, Ms. Baughman McLeod said.

Giving people better ways to conceptualize heat is critical, she said.

“It’s not dramatic. It doesn’t rip the roof off of your house,” Ms. Baughman McLeod said. “It’s silent and invisible.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

After more than a week of record-breaking temperatures across much of the country, public health experts are cautioning that children are more susceptible to heat illness than adults are – even more so when they’re on the athletic field, living without air conditioning, or waiting in a parked car.

Cases of heat-related illness are rising with average air temperatures, and experts say almost half of those getting sick are children. The reason is twofold: Children’s bodies have more trouble regulating temperature than do those of adults, and they rely on adults to help protect them from overheating.

Parents, coaches, and other caretakers, who can experience the same heat very differently from the way children do, may struggle to identify a dangerous situation or catch the early symptoms of heat-related illness in children.

“Children are not little adults,” said Dr. Aaron Bernstein, a pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Jan Null, a meteorologist in California, recalled being surprised at the effect of heat in a car. It was 86 degrees on a July afternoon more than 2 decades ago when an infant in San Jose was forgotten in a parked car and died of heatstroke.

Mr. Null said a reporter asked him after the death, “How hot could it have gotten in that car?”

Mr. Null’s research with two emergency doctors at Stanford University eventually produced a startling answer. Within an hour, the temperature in that car could have exceeded 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Their work revealed that a quick errand can be dangerous for a child left behind in the car – even for less than 15 minutes, even with the windows cracked, and even on a mild day.

As record heat becomes more frequent, posing serious risks even to healthy adults, the number of cases of heat-related illnesses has gone up, including among children. Those most at risk are young children in parked vehicles and adolescents returning to school and participating in sports during the hottest days of the year.

More than 9,000 high school athletes are treated for heat-related illnesses every year.

Heat-related illnesses occur when exposure to high temperatures and humidity, which can be intensified by physical exertion, overwhelms the body’s ability to cool itself. Cases range from mild, like benign heat rashes in infants, to more serious, when the body’s core temperature increases. That can lead to life-threatening instances of heatstroke, diagnosed once the body temperature rises above 104 degrees, potentially causing organ failure.

Prevention is key. Experts emphasize that drinking plenty of water, avoiding the outdoors during the hot midday and afternoon hours, and taking it slow when adjusting to exercise are the most effective ways to avoid getting sick.

Children’s bodies take longer to increase sweat production and otherwise acclimatize in a warm environment than adults’ do, research shows. Young children are more susceptible to dehydration because a larger percentage of their body weight is water.

Infants and younger children have more trouble regulating their body temperature, in part because they often don’t recognize when they should drink more water or remove clothing to cool down. A 1995 study showed that young children who spent 30 minutes in a 95-degree room saw their core temperatures rise significantly higher and faster than their mothers’ – even though they sweat more than adults do relative to their size.

Pediatricians advise caretakers to monitor how much water children consume and encourage them to drink before they ask for it. Thirst indicates the body is already dehydrated.

They should dress children in light-colored, lightweight clothes; limit outdoor time during the hottest hours; and look for ways to cool down, such as by visiting an air-conditioned place like a library, taking a cool bath, or going for a swim.

To address the risks to student athletes, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association recommends that high school athletes acclimatize by gradually building their activity over the course of 2 weeks when returning to their sport for a new season – including by slowly stepping up the amount of any protective equipment they wear.

“You’re gradually increasing that intensity over a week to 2 weeks so your body can get used to the heat,” said Kathy Dieringer, president of NATA.

Warning signs and solutions

Experts note a flushed face, fatigue, muscle cramps, headache, dizziness, vomiting, and a lot of sweating are among the symptoms of heat exhaustion, which can develop into heatstroke if untreated. A doctor should be notified if symptoms worsen, such as if the child seems disoriented or cannot drink.

Taking immediate steps to cool a child experiencing heat exhaustion or heatstroke is critical. The child should be taken to a shaded or cool area; be given cool fluids with salt, like sports drinks; and have any sweaty or heavy garments removed.

For adolescents, being submerged in an ice bath is the most effective way to cool the body, while younger children can be wrapped in cold, wet towels or misted with lukewarm water and placed in front of a fan.

Although children’s deaths in parked cars have been well documented, the tragic incidents continue to occur. According to federal statistics, 23 children died of vehicular heatstroke in 2021. Mr. Null, who collects his own data, said 13 children have died so far this year.

Caretakers should never leave children alone in a parked car, Mr. Null said. Take steps to prevent young children from entering the car themselves and becoming trapped, including locking the car while it’s parked at home.

More than half of cases of vehicular pediatric heatstroke occur because a caretaker accidentally left a child behind, he said. While in-car technology reminding adults to check their back seats has become more common, only a fraction of vehicles have it, requiring parents to come up with their own methods, like leaving a stuffed animal in the front seat.

The good news, Mr. Null said, is that simple behavioral changes can protect youngsters. “This is preventable in 100% of the cases,” he said.

A lopsided risk

People living in low-income areas fare worse when temperatures climb. Access to air conditioning, which includes the ability to afford the electricity bill, is a serious health concern.

A study of heat in urban areas released last year showed that low-income neighborhoods and communities of color experience much higher temperatures than those of wealthier, White residents. In more impoverished areas during the summer, temperatures can be as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer.

The study’s authors said their findings in the United States reflect that “the legacy of redlining looms large,” referring to a federal housing policy that refused to insure mortgages in or near predominantly Black neighborhoods.

“These areas have less tree canopy, more streets, and higher building densities, meaning that in addition to their other racist outcomes, redlining policies directly codified into law existing disparity in urban land use and reinforced urban design choices that magnify urban heating into the present,” they concluded.

Dr. Bernstein, who leads Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment, coauthored a commentary in JAMA arguing that advancing health equity is critical to action on climate change.

The center works with front-line health clinics to help their predominantly low-income patients respond to the health impacts of climate change. Federally backed clinics alone provide care to about 30 million Americans, including many children, he said.

Dr. Bernstein also recently led a nationwide study that found that from May through September, days with higher temperatures are associated with more visits to children’s hospital emergency rooms. Many visits were more directly linked to heat, although the study also pointed to how high temperatures can exacerbate existing health conditions such as neurological disorders.

“Children are more vulnerable to climate change through how these climate shocks reshape the world in which they grow up,” Dr. Bernstein said.

Helping people better understand the health risks of extreme heat and how to protect themselves and their families are among the public health system’s major challenges, experts said.

The National Weather Service’s heat alert system is mainly based on the heat index, a measure of how hot it feels when relative humidity is factored in with air temperature.

But the alerts are not related to effects on health, said Kathy Baughman McLeod, director of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center. By the time temperatures rise to the level that a weather alert is issued, many vulnerable people – like children, pregnant women, and the elderly – may already be experiencing heat exhaustion or heatstroke.

The center developed a new heat alert system, which is being tested in Seville, Spain, historically one of the hottest cities in Europe.

The system marries metrics such as air temperature and humidity with public health data to categorize heat waves and, when they are serious enough, give them names – making it easier for people to understand heat as an environmental threat that requires prevention measures.

The categories are determined through a metric known as excess deaths, which compares how many people died on a day with the forecast temperature versus an average day. That may help health officials understand how severe a heat wave is expected to be and make informed recommendations to the public based on risk factors such as age or medical history.

The health-based alert system would also allow officials to target caretakers of children and seniors through school systems, preschools, and senior centers, Ms. Baughman McLeod said.

Giving people better ways to conceptualize heat is critical, she said.

“It’s not dramatic. It doesn’t rip the roof off of your house,” Ms. Baughman McLeod said. “It’s silent and invisible.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

‘Go Ask Alice’: A fake view of teen mental health

If you grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, chances are high you’re familiar with “Go Ask Alice.”

What was then said to be the real diary of a 15-year-old promising teen turned drug addict was released in 1971 as a cautionary tale and has since sold over 5 million copies. The diary was harrowing against the backdrop of the war on drugs and soon became both acclaimed and banned from classrooms across the country.

Schools citied “inappropriate” language that “borders on pornography” as grounds to prohibit teenagers from reading Alice’s story. But as much as the book’s vivid writing offended readers, it drew millions in with its profanity and graphic descriptions of sex, drugs, and mental health struggles.

At the time, The New York Times reviewed the book as “a strong, painfully honest, nakedly candid and true story ... a document of horrifying reality,” but the popular diary was later found to be a ploy – a fake story written by a 54-year-old Mormon youth counselor named Beatrice Sparks.

Now, Ms. Sparks, who died in 2012, has been further exposed in radio personality Rick Emerson’s new book, “Unmask Alice: LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries.” Mr. Emerson published the exposé in July, years after he had the idea to investigate Ms. Sparks’s work in 2015. The book details Ms. Sparks’s background, her journey in creating Alice, and her quest to be recognized for the teen diary she had published as “Anonymous.”

“After 30 years of trying, Beatrice Sparks had changed the world. And nobody knew it,” Mr. Emerson told the New York Post.In his work, Mr. Emerson also dives into the profound impact of the diary at a time when not as much research existed on teen mental health.

When the teenager whose diary inspired Ms. Sparks’s writing “died in March 1971, the very first true study of adolescent psychology had just barely come out,” Mr. Emerson said to Rolling Stone. “Mental health, especially for young people, was still very much on training wheels.”

According to Mr. Emerson, a lack of insight into mental health issues allowed Ms. Sparks’s description to go relatively unchallenged and for the book’s influence to spread despite its misinformation.

“It’s indisputable that large sections of ‘Go Ask Alice’ are just embellished and/or false,” he told the Post.

Then versus now

This landscape is in stark contrast to today, where thousands of studies on the topic have been done, compared with the mere dozens in the 1970s.

Anxiety and depression in minors have increased over time, a trend worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the CDC. Studies have shown that reported drug use in teens has decreased over time, proving significant during the pandemic, according to the National Institutes of Health.

While Alice from “Go Ask Alice” has not existed in either, comparing the two periods can offer insight into teen struggles in the 1970s versus today and sheds light on how literature – fiction or even faked nonfiction – can transform a nation.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

If you grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, chances are high you’re familiar with “Go Ask Alice.”

What was then said to be the real diary of a 15-year-old promising teen turned drug addict was released in 1971 as a cautionary tale and has since sold over 5 million copies. The diary was harrowing against the backdrop of the war on drugs and soon became both acclaimed and banned from classrooms across the country.

Schools citied “inappropriate” language that “borders on pornography” as grounds to prohibit teenagers from reading Alice’s story. But as much as the book’s vivid writing offended readers, it drew millions in with its profanity and graphic descriptions of sex, drugs, and mental health struggles.

At the time, The New York Times reviewed the book as “a strong, painfully honest, nakedly candid and true story ... a document of horrifying reality,” but the popular diary was later found to be a ploy – a fake story written by a 54-year-old Mormon youth counselor named Beatrice Sparks.

Now, Ms. Sparks, who died in 2012, has been further exposed in radio personality Rick Emerson’s new book, “Unmask Alice: LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries.” Mr. Emerson published the exposé in July, years after he had the idea to investigate Ms. Sparks’s work in 2015. The book details Ms. Sparks’s background, her journey in creating Alice, and her quest to be recognized for the teen diary she had published as “Anonymous.”

“After 30 years of trying, Beatrice Sparks had changed the world. And nobody knew it,” Mr. Emerson told the New York Post.In his work, Mr. Emerson also dives into the profound impact of the diary at a time when not as much research existed on teen mental health.

When the teenager whose diary inspired Ms. Sparks’s writing “died in March 1971, the very first true study of adolescent psychology had just barely come out,” Mr. Emerson said to Rolling Stone. “Mental health, especially for young people, was still very much on training wheels.”

According to Mr. Emerson, a lack of insight into mental health issues allowed Ms. Sparks’s description to go relatively unchallenged and for the book’s influence to spread despite its misinformation.

“It’s indisputable that large sections of ‘Go Ask Alice’ are just embellished and/or false,” he told the Post.

Then versus now

This landscape is in stark contrast to today, where thousands of studies on the topic have been done, compared with the mere dozens in the 1970s.

Anxiety and depression in minors have increased over time, a trend worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the CDC. Studies have shown that reported drug use in teens has decreased over time, proving significant during the pandemic, according to the National Institutes of Health.

While Alice from “Go Ask Alice” has not existed in either, comparing the two periods can offer insight into teen struggles in the 1970s versus today and sheds light on how literature – fiction or even faked nonfiction – can transform a nation.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

If you grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, chances are high you’re familiar with “Go Ask Alice.”

What was then said to be the real diary of a 15-year-old promising teen turned drug addict was released in 1971 as a cautionary tale and has since sold over 5 million copies. The diary was harrowing against the backdrop of the war on drugs and soon became both acclaimed and banned from classrooms across the country.

Schools citied “inappropriate” language that “borders on pornography” as grounds to prohibit teenagers from reading Alice’s story. But as much as the book’s vivid writing offended readers, it drew millions in with its profanity and graphic descriptions of sex, drugs, and mental health struggles.

At the time, The New York Times reviewed the book as “a strong, painfully honest, nakedly candid and true story ... a document of horrifying reality,” but the popular diary was later found to be a ploy – a fake story written by a 54-year-old Mormon youth counselor named Beatrice Sparks.

Now, Ms. Sparks, who died in 2012, has been further exposed in radio personality Rick Emerson’s new book, “Unmask Alice: LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries.” Mr. Emerson published the exposé in July, years after he had the idea to investigate Ms. Sparks’s work in 2015. The book details Ms. Sparks’s background, her journey in creating Alice, and her quest to be recognized for the teen diary she had published as “Anonymous.”

“After 30 years of trying, Beatrice Sparks had changed the world. And nobody knew it,” Mr. Emerson told the New York Post.In his work, Mr. Emerson also dives into the profound impact of the diary at a time when not as much research existed on teen mental health.

When the teenager whose diary inspired Ms. Sparks’s writing “died in March 1971, the very first true study of adolescent psychology had just barely come out,” Mr. Emerson said to Rolling Stone. “Mental health, especially for young people, was still very much on training wheels.”

According to Mr. Emerson, a lack of insight into mental health issues allowed Ms. Sparks’s description to go relatively unchallenged and for the book’s influence to spread despite its misinformation.

“It’s indisputable that large sections of ‘Go Ask Alice’ are just embellished and/or false,” he told the Post.

Then versus now

This landscape is in stark contrast to today, where thousands of studies on the topic have been done, compared with the mere dozens in the 1970s.

Anxiety and depression in minors have increased over time, a trend worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the CDC. Studies have shown that reported drug use in teens has decreased over time, proving significant during the pandemic, according to the National Institutes of Health.

While Alice from “Go Ask Alice” has not existed in either, comparing the two periods can offer insight into teen struggles in the 1970s versus today and sheds light on how literature – fiction or even faked nonfiction – can transform a nation.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

AAP updates hyperbilirubinemia guideline

Raising phototherapy thresholds and revising risk assessment are among the key changes in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ updated guidelines for managing hyperbilirubinemia in infants 35 weeks’ gestation and older.

“More than 80% of newborn infants will have some degree of jaundice,” Alex R. Kemper, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and coauthors wrote. Careful monitoring is needed manage high bilirubin concentrations and avoid acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE) and kernicterus, a disabling neurologic condition.

The current revision, published in Pediatrics, updates and replaces the 2004 AAP clinical practice guidelines for the management and prevention of hyperbilirubinemia in newborns of at least 35 weeks’ gestation.

The guideline committee reviewed evidence published since the previous guidelines were issued in 2004, and addressed similar issues of prevention, risk assessment, monitoring, and treatment.

A notable change from 2004 was the inclusion of a 2009 recommendation update for “universal predischarge bilirubin screening with measures of total serum bilirubin (TSB) or transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) linked to specific recommendations for follow-up,” the authors wrote.

In terms of prevention, recommendations include a direct antiglobulin test (DAT) for infants whose mother’s antibody screen was positive or unknown. In addition, exclusive breastfeeding is known to be associated with hyperbilirubinemia, but clinicians should support breastfeeding while monitoring for signs of hyperbilirubinemia because of suboptimal feeding, the authors noted. However, the guidelines recommend against oral supplementation with water or dextrose water to prevent hyperbilirubinemia.

For assessment and monitoring, the guidelines advise the use of total serum bilirubin (TSB) as the definitive test for hyperbilirubinemia to guide phototherapy and escalation of care, including exchange transfusion. “The presence of hyperbilirubinemia neurotoxicity risk factors lowers the threshold for treatment with phototherapy and the level at which care should be escalated,” the authors wrote. They also emphasized the need to consider glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, a genetic condition that decreases protection against oxidative stress and has been identified as a leading cause of hazardous hyperbilirubinemia worldwide.

The guidelines recommend assessing all infants for jaundice at least every 12 hours after delivery until discharge, with TSB or TcB measured as soon as possible for those with suspected jaundice. The complete guidelines include charts for TSB levels to guide escalation of care. “Blood for TSB can be obtained at the time it is collected for newborn screening tests to avoid an additional heel stick,” the authors noted.

The rate of increase in TSB or TcB, if more than one measure is available, may identify infants at higher risk of hyperbilirubinemia, according to the guidelines, and a possible delay of hospital discharge may be needed for infants if appropriate follow-up is not feasible.

In terms of treatment, new evidence that bilirubin neurotoxicity does not occur until concentrations well above those given in the 2004 guidelines justified raising the treatment thresholds, although by a narrow range. “With the increased phototherapy thresholds, appropriately following the current guidelines including bilirubin screening during the birth hospitalization and timely postdischarge follow-up is important,” the authors wrote. The new thresholds, outlined in the complete guidelines, are based on gestational age, hyperbilirubinemia neurotoxicity risk factors, and the age of the infant in hours. However, infants may be treated at lower levels, based on individual circumstances, family preferences, and shared decision-making with clinicians. Home-based phototherapy may be used in some infants, but should not be used if there is a question about the device quality, delivery time, and ability of caregivers to use the device correctly.

“Discontinuing phototherapy is an option when the TSB has decreased by at least 2 mg/dL below the hour-specific threshold at the initiation of phototherapy,” and follow-up should be based on risk of rebound hyperbilirubinemia, according to the guidelines.

“This clinical practice guideline provides indications and approaches for phototherapy and escalation of care and when treatment and monitoring can be safely discontinued,” However, clinicians should understand the rationale for the recommendations and combine them with their clinical judgment, including shared decision-making when appropriate, the authors concluded.

Updated evidence supports escalating care

The take-home message for pediatricians is that neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is a very common finding, and complications are rare, but the condition can result in devastating life-long results, Cathy Haut, DNP, CPNP-AC, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in Rehoboth Beach, Del., said in an interview.

“Previous guidelines published in 2004 and updated in 2009 included evidence-based recommendations, but additional research was still needed to provide guidance for providers to prevent complications of hyperbilirubinemia,” said Dr. Haut, who was not involved in producing the guidelines.

“New data documenting additional risk factors, the importance of ongoing breastfeeding support, and addressing hyperbilirubinemia as an urgent problem” are additions to prevention methods in the latest published guidelines, she said.

“Acute encephalopathy and kernicterus can result from hyperbilirubinemia with severe and devastating neurologic effects, but are preventable by early identification and treatment,” said Dr. Haut. Therefore, “it is not surprising that the AAP utilized continuing and more recent evidence to support new recommendations. Both maternal and neonatal risk factors have long been considered in the development of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, but recent recommendations incorporate additional risk factor evaluation and urgency in time to appropriate care. Detailed thresholds for phototherapy and exchange transfusion will benefit the families of full-term infants without other risk factors and escalate care for those neonates with risk factors.”

However, potential barriers to following the guidelines persist, Dr. Haut noted.

“Frequent infant follow-up can be challenging for busy primary care offices with outpatient laboratory results often taking much longer to obtain than in a hospital setting,” she said.

Also, “taking a newborn to the emergency department or an inpatient laboratory can be frightening for families with the risk of illness exposure. Frequent monitoring of serum bilirubin levels is disturbing for parents and inconvenient immediately postpartum,” Dr. Haut explained. “Few practices utilize transcutaneous bilirubin monitoring which may be one method of added screening.”

In addition, “despite the importance of breastfeeding, ongoing support is not readily available for mothers after hospital discharge. A lactation specialist in the office setting can take the burden off providers and add opportunity for family education.”

As for additional research, “continued evaluation of the comparison of transcutaneous bilirubin monitoring and serum levels along with the use of transcutaneous monitoring in facilities outside the hospital setting may be warranted,” Dr. Haut said. “Data collection on incidence and accompanying risk factors of neonates who develop acute hyperbilirubinemia encephalopathy and kernicterus is a long-term study opportunity.”

The guidelines received no external funding. Lead author Dr. Kemper had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Haut had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Raising phototherapy thresholds and revising risk assessment are among the key changes in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ updated guidelines for managing hyperbilirubinemia in infants 35 weeks’ gestation and older.

“More than 80% of newborn infants will have some degree of jaundice,” Alex R. Kemper, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and coauthors wrote. Careful monitoring is needed manage high bilirubin concentrations and avoid acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE) and kernicterus, a disabling neurologic condition.

The current revision, published in Pediatrics, updates and replaces the 2004 AAP clinical practice guidelines for the management and prevention of hyperbilirubinemia in newborns of at least 35 weeks’ gestation.

The guideline committee reviewed evidence published since the previous guidelines were issued in 2004, and addressed similar issues of prevention, risk assessment, monitoring, and treatment.

A notable change from 2004 was the inclusion of a 2009 recommendation update for “universal predischarge bilirubin screening with measures of total serum bilirubin (TSB) or transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) linked to specific recommendations for follow-up,” the authors wrote.

In terms of prevention, recommendations include a direct antiglobulin test (DAT) for infants whose mother’s antibody screen was positive or unknown. In addition, exclusive breastfeeding is known to be associated with hyperbilirubinemia, but clinicians should support breastfeeding while monitoring for signs of hyperbilirubinemia because of suboptimal feeding, the authors noted. However, the guidelines recommend against oral supplementation with water or dextrose water to prevent hyperbilirubinemia.

For assessment and monitoring, the guidelines advise the use of total serum bilirubin (TSB) as the definitive test for hyperbilirubinemia to guide phototherapy and escalation of care, including exchange transfusion. “The presence of hyperbilirubinemia neurotoxicity risk factors lowers the threshold for treatment with phototherapy and the level at which care should be escalated,” the authors wrote. They also emphasized the need to consider glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, a genetic condition that decreases protection against oxidative stress and has been identified as a leading cause of hazardous hyperbilirubinemia worldwide.

The guidelines recommend assessing all infants for jaundice at least every 12 hours after delivery until discharge, with TSB or TcB measured as soon as possible for those with suspected jaundice. The complete guidelines include charts for TSB levels to guide escalation of care. “Blood for TSB can be obtained at the time it is collected for newborn screening tests to avoid an additional heel stick,” the authors noted.

The rate of increase in TSB or TcB, if more than one measure is available, may identify infants at higher risk of hyperbilirubinemia, according to the guidelines, and a possible delay of hospital discharge may be needed for infants if appropriate follow-up is not feasible.

In terms of treatment, new evidence that bilirubin neurotoxicity does not occur until concentrations well above those given in the 2004 guidelines justified raising the treatment thresholds, although by a narrow range. “With the increased phototherapy thresholds, appropriately following the current guidelines including bilirubin screening during the birth hospitalization and timely postdischarge follow-up is important,” the authors wrote. The new thresholds, outlined in the complete guidelines, are based on gestational age, hyperbilirubinemia neurotoxicity risk factors, and the age of the infant in hours. However, infants may be treated at lower levels, based on individual circumstances, family preferences, and shared decision-making with clinicians. Home-based phototherapy may be used in some infants, but should not be used if there is a question about the device quality, delivery time, and ability of caregivers to use the device correctly.

“Discontinuing phototherapy is an option when the TSB has decreased by at least 2 mg/dL below the hour-specific threshold at the initiation of phototherapy,” and follow-up should be based on risk of rebound hyperbilirubinemia, according to the guidelines.

“This clinical practice guideline provides indications and approaches for phototherapy and escalation of care and when treatment and monitoring can be safely discontinued,” However, clinicians should understand the rationale for the recommendations and combine them with their clinical judgment, including shared decision-making when appropriate, the authors concluded.

Updated evidence supports escalating care

The take-home message for pediatricians is that neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is a very common finding, and complications are rare, but the condition can result in devastating life-long results, Cathy Haut, DNP, CPNP-AC, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in Rehoboth Beach, Del., said in an interview.

“Previous guidelines published in 2004 and updated in 2009 included evidence-based recommendations, but additional research was still needed to provide guidance for providers to prevent complications of hyperbilirubinemia,” said Dr. Haut, who was not involved in producing the guidelines.

“New data documenting additional risk factors, the importance of ongoing breastfeeding support, and addressing hyperbilirubinemia as an urgent problem” are additions to prevention methods in the latest published guidelines, she said.

“Acute encephalopathy and kernicterus can result from hyperbilirubinemia with severe and devastating neurologic effects, but are preventable by early identification and treatment,” said Dr. Haut. Therefore, “it is not surprising that the AAP utilized continuing and more recent evidence to support new recommendations. Both maternal and neonatal risk factors have long been considered in the development of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, but recent recommendations incorporate additional risk factor evaluation and urgency in time to appropriate care. Detailed thresholds for phototherapy and exchange transfusion will benefit the families of full-term infants without other risk factors and escalate care for those neonates with risk factors.”

However, potential barriers to following the guidelines persist, Dr. Haut noted.

“Frequent infant follow-up can be challenging for busy primary care offices with outpatient laboratory results often taking much longer to obtain than in a hospital setting,” she said.

Also, “taking a newborn to the emergency department or an inpatient laboratory can be frightening for families with the risk of illness exposure. Frequent monitoring of serum bilirubin levels is disturbing for parents and inconvenient immediately postpartum,” Dr. Haut explained. “Few practices utilize transcutaneous bilirubin monitoring which may be one method of added screening.”

In addition, “despite the importance of breastfeeding, ongoing support is not readily available for mothers after hospital discharge. A lactation specialist in the office setting can take the burden off providers and add opportunity for family education.”

As for additional research, “continued evaluation of the comparison of transcutaneous bilirubin monitoring and serum levels along with the use of transcutaneous monitoring in facilities outside the hospital setting may be warranted,” Dr. Haut said. “Data collection on incidence and accompanying risk factors of neonates who develop acute hyperbilirubinemia encephalopathy and kernicterus is a long-term study opportunity.”

The guidelines received no external funding. Lead author Dr. Kemper had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Haut had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Raising phototherapy thresholds and revising risk assessment are among the key changes in the American Academy of Pediatrics’ updated guidelines for managing hyperbilirubinemia in infants 35 weeks’ gestation and older.

“More than 80% of newborn infants will have some degree of jaundice,” Alex R. Kemper, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, and coauthors wrote. Careful monitoring is needed manage high bilirubin concentrations and avoid acute bilirubin encephalopathy (ABE) and kernicterus, a disabling neurologic condition.

The current revision, published in Pediatrics, updates and replaces the 2004 AAP clinical practice guidelines for the management and prevention of hyperbilirubinemia in newborns of at least 35 weeks’ gestation.

The guideline committee reviewed evidence published since the previous guidelines were issued in 2004, and addressed similar issues of prevention, risk assessment, monitoring, and treatment.

A notable change from 2004 was the inclusion of a 2009 recommendation update for “universal predischarge bilirubin screening with measures of total serum bilirubin (TSB) or transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) linked to specific recommendations for follow-up,” the authors wrote.

In terms of prevention, recommendations include a direct antiglobulin test (DAT) for infants whose mother’s antibody screen was positive or unknown. In addition, exclusive breastfeeding is known to be associated with hyperbilirubinemia, but clinicians should support breastfeeding while monitoring for signs of hyperbilirubinemia because of suboptimal feeding, the authors noted. However, the guidelines recommend against oral supplementation with water or dextrose water to prevent hyperbilirubinemia.

For assessment and monitoring, the guidelines advise the use of total serum bilirubin (TSB) as the definitive test for hyperbilirubinemia to guide phototherapy and escalation of care, including exchange transfusion. “The presence of hyperbilirubinemia neurotoxicity risk factors lowers the threshold for treatment with phototherapy and the level at which care should be escalated,” the authors wrote. They also emphasized the need to consider glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, a genetic condition that decreases protection against oxidative stress and has been identified as a leading cause of hazardous hyperbilirubinemia worldwide.

The guidelines recommend assessing all infants for jaundice at least every 12 hours after delivery until discharge, with TSB or TcB measured as soon as possible for those with suspected jaundice. The complete guidelines include charts for TSB levels to guide escalation of care. “Blood for TSB can be obtained at the time it is collected for newborn screening tests to avoid an additional heel stick,” the authors noted.

The rate of increase in TSB or TcB, if more than one measure is available, may identify infants at higher risk of hyperbilirubinemia, according to the guidelines, and a possible delay of hospital discharge may be needed for infants if appropriate follow-up is not feasible.

In terms of treatment, new evidence that bilirubin neurotoxicity does not occur until concentrations well above those given in the 2004 guidelines justified raising the treatment thresholds, although by a narrow range. “With the increased phototherapy thresholds, appropriately following the current guidelines including bilirubin screening during the birth hospitalization and timely postdischarge follow-up is important,” the authors wrote. The new thresholds, outlined in the complete guidelines, are based on gestational age, hyperbilirubinemia neurotoxicity risk factors, and the age of the infant in hours. However, infants may be treated at lower levels, based on individual circumstances, family preferences, and shared decision-making with clinicians. Home-based phototherapy may be used in some infants, but should not be used if there is a question about the device quality, delivery time, and ability of caregivers to use the device correctly.

“Discontinuing phototherapy is an option when the TSB has decreased by at least 2 mg/dL below the hour-specific threshold at the initiation of phototherapy,” and follow-up should be based on risk of rebound hyperbilirubinemia, according to the guidelines.

“This clinical practice guideline provides indications and approaches for phototherapy and escalation of care and when treatment and monitoring can be safely discontinued,” However, clinicians should understand the rationale for the recommendations and combine them with their clinical judgment, including shared decision-making when appropriate, the authors concluded.

Updated evidence supports escalating care

The take-home message for pediatricians is that neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is a very common finding, and complications are rare, but the condition can result in devastating life-long results, Cathy Haut, DNP, CPNP-AC, CPNP-PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in Rehoboth Beach, Del., said in an interview.

“Previous guidelines published in 2004 and updated in 2009 included evidence-based recommendations, but additional research was still needed to provide guidance for providers to prevent complications of hyperbilirubinemia,” said Dr. Haut, who was not involved in producing the guidelines.

“New data documenting additional risk factors, the importance of ongoing breastfeeding support, and addressing hyperbilirubinemia as an urgent problem” are additions to prevention methods in the latest published guidelines, she said.

“Acute encephalopathy and kernicterus can result from hyperbilirubinemia with severe and devastating neurologic effects, but are preventable by early identification and treatment,” said Dr. Haut. Therefore, “it is not surprising that the AAP utilized continuing and more recent evidence to support new recommendations. Both maternal and neonatal risk factors have long been considered in the development of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, but recent recommendations incorporate additional risk factor evaluation and urgency in time to appropriate care. Detailed thresholds for phototherapy and exchange transfusion will benefit the families of full-term infants without other risk factors and escalate care for those neonates with risk factors.”

However, potential barriers to following the guidelines persist, Dr. Haut noted.

“Frequent infant follow-up can be challenging for busy primary care offices with outpatient laboratory results often taking much longer to obtain than in a hospital setting,” she said.

Also, “taking a newborn to the emergency department or an inpatient laboratory can be frightening for families with the risk of illness exposure. Frequent monitoring of serum bilirubin levels is disturbing for parents and inconvenient immediately postpartum,” Dr. Haut explained. “Few practices utilize transcutaneous bilirubin monitoring which may be one method of added screening.”

In addition, “despite the importance of breastfeeding, ongoing support is not readily available for mothers after hospital discharge. A lactation specialist in the office setting can take the burden off providers and add opportunity for family education.”

As for additional research, “continued evaluation of the comparison of transcutaneous bilirubin monitoring and serum levels along with the use of transcutaneous monitoring in facilities outside the hospital setting may be warranted,” Dr. Haut said. “Data collection on incidence and accompanying risk factors of neonates who develop acute hyperbilirubinemia encephalopathy and kernicterus is a long-term study opportunity.”

The guidelines received no external funding. Lead author Dr. Kemper had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Haut had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Death risk doubles for Black infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) who were born to Black mothers were significantly more likely to die or to have a longer hospital stay than infants of other ethnicities, based on data from more than 800 infants.

The overall incidence of BPD is rising, in part because of improved survival for extremely preterm infants, wrote Tamorah R. Lewis, MD, of the University of Missouri, Kansas City, and colleagues.

Previous studies suggest that racial disparities may affect outcomes for preterm infants with a range of neonatal morbidities during neonatal ICU (NICU) hospitalization, including respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage, and necrotizing enterocolitis. However, the association of racial disparities with outcomes for preterm infants with BPD remains unclear, they said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers, on behalf of the Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Collaborative, reviewed data from 834 preterm infants enrolled in the BPD Collaborative registry from Jan. 1, 2015, to July 19, 2021, at eight centers in the United States.

The study infants were born at less than 32 weeks’ gestation and were diagnosed with severe BPD according to the 2001 National Institutes of Health Consensus Criteria. The study population included 276 Black infants and 558 white infants. The median gestational age was 24 weeks, and 41% of the infants were female.

The primary outcomes were infant death and length of hospital stay.