User login

How long is it safe to delay gynecologic cancer surgery?

As I write this column, there are more than 25,000 current cases of COVID-19 in the United States with an expected exponential rise in these numbers. Hospitals are issuing directives to cancel or postpone “elective” surgery to preserve the finite essential personal protective equipment (PPE), encourage social distancing, prevent exposure of at-risk patients within the hospital, and ensure bed and ventilator capacity for the impending surge in COVID-19 patients.

Many health systems have defined which surgeries they consider permissible, typically by using time parameters such as would not cause patient harm if not performed within 4 weeks, or 7 days, or 24 hours. This leaves surgeons in the unfamiliar position of rationing health care, a role with which, over the coming months, we may have to become increasingly comfortable. This is an enormous responsibility, the shift of resources between one population in need and another, and decisions should be based on data, not bias or hunch. We know that untreated cancer is life threatening, but there is a difference between untreated and delayed. What is a safe time to wait for gynecologic cancer surgery after diagnosis without negatively affecting survival from that cancer?

As I looked through my own upcoming surgical schedule, I sought guidance from the American College of Surgeons’ website, updated on March 17, 2020. In this site they tabulate an “Elective Surgery Acuity Scale” in which “most cancers” fit into tier 3a, which corresponds to high acuity surgery – “do not postpone.” This definition is fairly generalized and blunt; it does not account for the differences in cancers and occasional voluntary needs to postpone a patient’s cancer surgery for health optimization. There are limited data that measure the impact of surgical wait times on survival from gynecologic cancer. Most of this research is observational, and therefore, is influenced by confounders causing delay in surgery (e.g., comorbid conditions or socioeconomic factors that limit access to care). However, the current enforced delays are involuntary; driven by the system, not the patient; and access is universally restricted.

Endometrial cancer

Most data regarding outcomes and gynecologic cancer delay come from endometrial cancer. In 2016, Shalowitz et al. evaluated 182,000 endometrial cancer cases documented within the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which captures approximately 70% of cancer surgeries in the United States.1 They separated these patients into groups of low-grade (grade 1 and 2 endometrioid) and high-grade (grade 3 endometrioid and nonendometrioid) cancers, and evaluated the groups for their overall survival, stratified by the time period between diagnosis and surgery. Interestingly, those whose surgery was performed under 2 weeks from diagnosis had worse perioperative mortality and long-term survival. This seems to be a function of lack of medical optimization; low-volume, nonspecialized centers having less wait time; and the presentation of more advanced and symptomatic disease demanding a more urgent surgery. After those initial 2 weeks of worse outcomes, there was a period of stable outcomes and safety in waiting that extended up to 8 weeks for patients with low-grade cancers and up to 18 weeks for patients with high-grade cancers.

It may be counterintuitive to think that surgical delay affects patients with high-grade endometrial cancers less. These are more aggressive cancers, and there is patient and provider concern for metastatic spread with time elapsed. But an expedited surgery does not appear to be necessary for this group. The Shalowitz study demonstrated no risk for upstaging with surgical delay, meaning that advanced stage was not more likely to be identified in patients whose surgery was delayed, compared with those performed earlier. This observation suggests that the survival from high-grade endometrial cancers is largely determined by factors that cannot be controlled by the surgeon such as the stage at diagnosis, occult spread, and decreased responsiveness of the tumor to adjuvant therapy. In other words, fast-tracking these patients to surgery has limited influence on the outcomes for high-grade endometrial cancers.

For low-grade cancers, adverse outcomes were seen with a surgical delay of more than 8 weeks. But this may not have been caused by progression of disease (low-grade cancers also were not upstaged with delays), but rather may reflect that, in normal times, elective delays of more than 8 weeks are a function of necessary complex medical optimization of comorbidities (such as obesity-related disease). The survival that is measured by NCDB is not disease specific, and patients with comorbidities will be more likely to have impaired overall survival.

A systematic review of all papers that looked at endometrial cancer outcomes associated with surgical delay determined that it is reasonable to delay surgery for up to 8 weeks.2

Ovarian cancer

The data for ovarian cancer surgery is more limited. Most literature discusses the impact of delay in the time between surgery and the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, but there are limited data exploring how a delay in primary debulking negatively affects patients. This is perhaps because advanced ovarian cancer surgery rarely is delayed because of symptoms and apparent advanced stage at diagnosis. When a patient’s surgery does need to be voluntarily delayed, for example for medical optimization, there is the option of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in which surgery is performed after three or more cycles of chemotherapy. NACT has been shown in multiple studies to have noninferior cancer outcomes, compared with primary debulking surgery.3,4

Perhaps in this current environment in which access to operating rooms and supplies is rationed, we should consider offering more, or all, patients NACT? Hospital stays after primary cytoreductive surgeries are typically 3-7 days in length, and these patients are at a higher risk, compared with other gynecologic cancer surgeries, of ICU admission and blood transfusions, both limited resources in this current environment. The disadvantage of this approach is that, while chemotherapy can keep patients out of the hospital so that they can practice social distancing, this particular therapy adds to the immunocompromised population. However, even patients who undergo primary surgical cytoreductive surgery will need to rapidly transition to immunosuppressive cytotoxic therapy; therefore it is unlikely that this can be avoided entirely during this time.

Lower genital tract cancers

Surgery for patients with lower genital tract cancers – such as cervical and vulvar cancer – also can probably be safely delayed for a 4-week period, and possibly longer. A Canadian retrospective study looked collectively at cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancers evaluating for disease progression associated with delay to surgery, using 28 days as a benchmark for delayed surgery.5 They found no significant increased progression associated with surgical delay greater than 28 days. This study evaluated progression of cancer and did not measure cancer survival, although it is unlikely we would see impaired survival without a significant increase in disease progression.

We also can look to outcomes from delayed radical hysterectomy for stage I cervical cancer in pregnancy to provided us with some data. A retrospective cohort study observed no difference in survival when 28 women with early-stage cervical cancer who were diagnosed in pregnancy (average wait time 20 weeks from diagnosis to treatment) were compared with the outcomes of 52 matched nonpregnant control patients (average wait time 8 weeks). Their survival was 89% versus 94% respectively (P = .08).6

Summary

Synthesizing this data, it appears that, in an environment of competing needs and resources, it is reasonable and safe to delay surgery for patients with gynecologic cancers for 4-6 weeks and potentially longer. This includes patients with high-grade endometrial cancers. Clearly, these decisions should be individualized to patients and different health systems. For example, a patient who presents with a cancer-associated life-threatening bowel obstruction or hemorrhage may need an immediate intervention, and communities minimally affected by the coronavirus pandemic may have more allowances for surgery. With respect to patient anxiety, most patients with cancer are keen to have surgery promptly, and breaking the news to them that their surgery may be delayed because of institutional and public health needs will be difficult. However, the data support that this is likely safe.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):268 e1-68 e18.

2. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;246:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.01.004.

3. N Engl J Med 2010;363(10):943-53.

4. Lancet 2015;386(9990):249-57.

5. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37(4):338-44.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):276 e1-76 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.034.

As I write this column, there are more than 25,000 current cases of COVID-19 in the United States with an expected exponential rise in these numbers. Hospitals are issuing directives to cancel or postpone “elective” surgery to preserve the finite essential personal protective equipment (PPE), encourage social distancing, prevent exposure of at-risk patients within the hospital, and ensure bed and ventilator capacity for the impending surge in COVID-19 patients.

Many health systems have defined which surgeries they consider permissible, typically by using time parameters such as would not cause patient harm if not performed within 4 weeks, or 7 days, or 24 hours. This leaves surgeons in the unfamiliar position of rationing health care, a role with which, over the coming months, we may have to become increasingly comfortable. This is an enormous responsibility, the shift of resources between one population in need and another, and decisions should be based on data, not bias or hunch. We know that untreated cancer is life threatening, but there is a difference between untreated and delayed. What is a safe time to wait for gynecologic cancer surgery after diagnosis without negatively affecting survival from that cancer?

As I looked through my own upcoming surgical schedule, I sought guidance from the American College of Surgeons’ website, updated on March 17, 2020. In this site they tabulate an “Elective Surgery Acuity Scale” in which “most cancers” fit into tier 3a, which corresponds to high acuity surgery – “do not postpone.” This definition is fairly generalized and blunt; it does not account for the differences in cancers and occasional voluntary needs to postpone a patient’s cancer surgery for health optimization. There are limited data that measure the impact of surgical wait times on survival from gynecologic cancer. Most of this research is observational, and therefore, is influenced by confounders causing delay in surgery (e.g., comorbid conditions or socioeconomic factors that limit access to care). However, the current enforced delays are involuntary; driven by the system, not the patient; and access is universally restricted.

Endometrial cancer

Most data regarding outcomes and gynecologic cancer delay come from endometrial cancer. In 2016, Shalowitz et al. evaluated 182,000 endometrial cancer cases documented within the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which captures approximately 70% of cancer surgeries in the United States.1 They separated these patients into groups of low-grade (grade 1 and 2 endometrioid) and high-grade (grade 3 endometrioid and nonendometrioid) cancers, and evaluated the groups for their overall survival, stratified by the time period between diagnosis and surgery. Interestingly, those whose surgery was performed under 2 weeks from diagnosis had worse perioperative mortality and long-term survival. This seems to be a function of lack of medical optimization; low-volume, nonspecialized centers having less wait time; and the presentation of more advanced and symptomatic disease demanding a more urgent surgery. After those initial 2 weeks of worse outcomes, there was a period of stable outcomes and safety in waiting that extended up to 8 weeks for patients with low-grade cancers and up to 18 weeks for patients with high-grade cancers.

It may be counterintuitive to think that surgical delay affects patients with high-grade endometrial cancers less. These are more aggressive cancers, and there is patient and provider concern for metastatic spread with time elapsed. But an expedited surgery does not appear to be necessary for this group. The Shalowitz study demonstrated no risk for upstaging with surgical delay, meaning that advanced stage was not more likely to be identified in patients whose surgery was delayed, compared with those performed earlier. This observation suggests that the survival from high-grade endometrial cancers is largely determined by factors that cannot be controlled by the surgeon such as the stage at diagnosis, occult spread, and decreased responsiveness of the tumor to adjuvant therapy. In other words, fast-tracking these patients to surgery has limited influence on the outcomes for high-grade endometrial cancers.

For low-grade cancers, adverse outcomes were seen with a surgical delay of more than 8 weeks. But this may not have been caused by progression of disease (low-grade cancers also were not upstaged with delays), but rather may reflect that, in normal times, elective delays of more than 8 weeks are a function of necessary complex medical optimization of comorbidities (such as obesity-related disease). The survival that is measured by NCDB is not disease specific, and patients with comorbidities will be more likely to have impaired overall survival.

A systematic review of all papers that looked at endometrial cancer outcomes associated with surgical delay determined that it is reasonable to delay surgery for up to 8 weeks.2

Ovarian cancer

The data for ovarian cancer surgery is more limited. Most literature discusses the impact of delay in the time between surgery and the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, but there are limited data exploring how a delay in primary debulking negatively affects patients. This is perhaps because advanced ovarian cancer surgery rarely is delayed because of symptoms and apparent advanced stage at diagnosis. When a patient’s surgery does need to be voluntarily delayed, for example for medical optimization, there is the option of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in which surgery is performed after three or more cycles of chemotherapy. NACT has been shown in multiple studies to have noninferior cancer outcomes, compared with primary debulking surgery.3,4

Perhaps in this current environment in which access to operating rooms and supplies is rationed, we should consider offering more, or all, patients NACT? Hospital stays after primary cytoreductive surgeries are typically 3-7 days in length, and these patients are at a higher risk, compared with other gynecologic cancer surgeries, of ICU admission and blood transfusions, both limited resources in this current environment. The disadvantage of this approach is that, while chemotherapy can keep patients out of the hospital so that they can practice social distancing, this particular therapy adds to the immunocompromised population. However, even patients who undergo primary surgical cytoreductive surgery will need to rapidly transition to immunosuppressive cytotoxic therapy; therefore it is unlikely that this can be avoided entirely during this time.

Lower genital tract cancers

Surgery for patients with lower genital tract cancers – such as cervical and vulvar cancer – also can probably be safely delayed for a 4-week period, and possibly longer. A Canadian retrospective study looked collectively at cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancers evaluating for disease progression associated with delay to surgery, using 28 days as a benchmark for delayed surgery.5 They found no significant increased progression associated with surgical delay greater than 28 days. This study evaluated progression of cancer and did not measure cancer survival, although it is unlikely we would see impaired survival without a significant increase in disease progression.

We also can look to outcomes from delayed radical hysterectomy for stage I cervical cancer in pregnancy to provided us with some data. A retrospective cohort study observed no difference in survival when 28 women with early-stage cervical cancer who were diagnosed in pregnancy (average wait time 20 weeks from diagnosis to treatment) were compared with the outcomes of 52 matched nonpregnant control patients (average wait time 8 weeks). Their survival was 89% versus 94% respectively (P = .08).6

Summary

Synthesizing this data, it appears that, in an environment of competing needs and resources, it is reasonable and safe to delay surgery for patients with gynecologic cancers for 4-6 weeks and potentially longer. This includes patients with high-grade endometrial cancers. Clearly, these decisions should be individualized to patients and different health systems. For example, a patient who presents with a cancer-associated life-threatening bowel obstruction or hemorrhage may need an immediate intervention, and communities minimally affected by the coronavirus pandemic may have more allowances for surgery. With respect to patient anxiety, most patients with cancer are keen to have surgery promptly, and breaking the news to them that their surgery may be delayed because of institutional and public health needs will be difficult. However, the data support that this is likely safe.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):268 e1-68 e18.

2. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;246:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.01.004.

3. N Engl J Med 2010;363(10):943-53.

4. Lancet 2015;386(9990):249-57.

5. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37(4):338-44.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):276 e1-76 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.034.

As I write this column, there are more than 25,000 current cases of COVID-19 in the United States with an expected exponential rise in these numbers. Hospitals are issuing directives to cancel or postpone “elective” surgery to preserve the finite essential personal protective equipment (PPE), encourage social distancing, prevent exposure of at-risk patients within the hospital, and ensure bed and ventilator capacity for the impending surge in COVID-19 patients.

Many health systems have defined which surgeries they consider permissible, typically by using time parameters such as would not cause patient harm if not performed within 4 weeks, or 7 days, or 24 hours. This leaves surgeons in the unfamiliar position of rationing health care, a role with which, over the coming months, we may have to become increasingly comfortable. This is an enormous responsibility, the shift of resources between one population in need and another, and decisions should be based on data, not bias or hunch. We know that untreated cancer is life threatening, but there is a difference between untreated and delayed. What is a safe time to wait for gynecologic cancer surgery after diagnosis without negatively affecting survival from that cancer?

As I looked through my own upcoming surgical schedule, I sought guidance from the American College of Surgeons’ website, updated on March 17, 2020. In this site they tabulate an “Elective Surgery Acuity Scale” in which “most cancers” fit into tier 3a, which corresponds to high acuity surgery – “do not postpone.” This definition is fairly generalized and blunt; it does not account for the differences in cancers and occasional voluntary needs to postpone a patient’s cancer surgery for health optimization. There are limited data that measure the impact of surgical wait times on survival from gynecologic cancer. Most of this research is observational, and therefore, is influenced by confounders causing delay in surgery (e.g., comorbid conditions or socioeconomic factors that limit access to care). However, the current enforced delays are involuntary; driven by the system, not the patient; and access is universally restricted.

Endometrial cancer

Most data regarding outcomes and gynecologic cancer delay come from endometrial cancer. In 2016, Shalowitz et al. evaluated 182,000 endometrial cancer cases documented within the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which captures approximately 70% of cancer surgeries in the United States.1 They separated these patients into groups of low-grade (grade 1 and 2 endometrioid) and high-grade (grade 3 endometrioid and nonendometrioid) cancers, and evaluated the groups for their overall survival, stratified by the time period between diagnosis and surgery. Interestingly, those whose surgery was performed under 2 weeks from diagnosis had worse perioperative mortality and long-term survival. This seems to be a function of lack of medical optimization; low-volume, nonspecialized centers having less wait time; and the presentation of more advanced and symptomatic disease demanding a more urgent surgery. After those initial 2 weeks of worse outcomes, there was a period of stable outcomes and safety in waiting that extended up to 8 weeks for patients with low-grade cancers and up to 18 weeks for patients with high-grade cancers.

It may be counterintuitive to think that surgical delay affects patients with high-grade endometrial cancers less. These are more aggressive cancers, and there is patient and provider concern for metastatic spread with time elapsed. But an expedited surgery does not appear to be necessary for this group. The Shalowitz study demonstrated no risk for upstaging with surgical delay, meaning that advanced stage was not more likely to be identified in patients whose surgery was delayed, compared with those performed earlier. This observation suggests that the survival from high-grade endometrial cancers is largely determined by factors that cannot be controlled by the surgeon such as the stage at diagnosis, occult spread, and decreased responsiveness of the tumor to adjuvant therapy. In other words, fast-tracking these patients to surgery has limited influence on the outcomes for high-grade endometrial cancers.

For low-grade cancers, adverse outcomes were seen with a surgical delay of more than 8 weeks. But this may not have been caused by progression of disease (low-grade cancers also were not upstaged with delays), but rather may reflect that, in normal times, elective delays of more than 8 weeks are a function of necessary complex medical optimization of comorbidities (such as obesity-related disease). The survival that is measured by NCDB is not disease specific, and patients with comorbidities will be more likely to have impaired overall survival.

A systematic review of all papers that looked at endometrial cancer outcomes associated with surgical delay determined that it is reasonable to delay surgery for up to 8 weeks.2

Ovarian cancer

The data for ovarian cancer surgery is more limited. Most literature discusses the impact of delay in the time between surgery and the receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, but there are limited data exploring how a delay in primary debulking negatively affects patients. This is perhaps because advanced ovarian cancer surgery rarely is delayed because of symptoms and apparent advanced stage at diagnosis. When a patient’s surgery does need to be voluntarily delayed, for example for medical optimization, there is the option of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in which surgery is performed after three or more cycles of chemotherapy. NACT has been shown in multiple studies to have noninferior cancer outcomes, compared with primary debulking surgery.3,4

Perhaps in this current environment in which access to operating rooms and supplies is rationed, we should consider offering more, or all, patients NACT? Hospital stays after primary cytoreductive surgeries are typically 3-7 days in length, and these patients are at a higher risk, compared with other gynecologic cancer surgeries, of ICU admission and blood transfusions, both limited resources in this current environment. The disadvantage of this approach is that, while chemotherapy can keep patients out of the hospital so that they can practice social distancing, this particular therapy adds to the immunocompromised population. However, even patients who undergo primary surgical cytoreductive surgery will need to rapidly transition to immunosuppressive cytotoxic therapy; therefore it is unlikely that this can be avoided entirely during this time.

Lower genital tract cancers

Surgery for patients with lower genital tract cancers – such as cervical and vulvar cancer – also can probably be safely delayed for a 4-week period, and possibly longer. A Canadian retrospective study looked collectively at cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancers evaluating for disease progression associated with delay to surgery, using 28 days as a benchmark for delayed surgery.5 They found no significant increased progression associated with surgical delay greater than 28 days. This study evaluated progression of cancer and did not measure cancer survival, although it is unlikely we would see impaired survival without a significant increase in disease progression.

We also can look to outcomes from delayed radical hysterectomy for stage I cervical cancer in pregnancy to provided us with some data. A retrospective cohort study observed no difference in survival when 28 women with early-stage cervical cancer who were diagnosed in pregnancy (average wait time 20 weeks from diagnosis to treatment) were compared with the outcomes of 52 matched nonpregnant control patients (average wait time 8 weeks). Their survival was 89% versus 94% respectively (P = .08).6

Summary

Synthesizing this data, it appears that, in an environment of competing needs and resources, it is reasonable and safe to delay surgery for patients with gynecologic cancers for 4-6 weeks and potentially longer. This includes patients with high-grade endometrial cancers. Clearly, these decisions should be individualized to patients and different health systems. For example, a patient who presents with a cancer-associated life-threatening bowel obstruction or hemorrhage may need an immediate intervention, and communities minimally affected by the coronavirus pandemic may have more allowances for surgery. With respect to patient anxiety, most patients with cancer are keen to have surgery promptly, and breaking the news to them that their surgery may be delayed because of institutional and public health needs will be difficult. However, the data support that this is likely safe.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):268 e1-68 e18.

2. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;246:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.01.004.

3. N Engl J Med 2010;363(10):943-53.

4. Lancet 2015;386(9990):249-57.

5. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37(4):338-44.

6. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):276 e1-76 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.034.

Preventable diseases could gain a foothold because of COVID-19

There is a highly infectious virus spreading around the world and it is targeting the most vulnerable among us. It is among the most contagious of human diseases, spreading through the air unseen. No, it isn’t the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. It’s measles.

Remember measles? Outbreaks in recent years have brought the disease, which once was declared eliminated in the United States, back into the news and public awareness, but measles never has really gone away. Every year there are millions of cases worldwide – in 2018 alone there were nearly 10 million estimated cases and 142,300 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. The good news is that measles vaccination is highly effective, at about 97% after the recommended two doses. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “because of vaccination, more than 21 million lives have been saved and measles deaths have been reduced by 80% since 2000.” This is a tremendous public health success and a cause for celebration. But our work is not done. The recent increases in vaccine hesitancy and refusal in many countries has contributed to the resurgence of measles worldwide.

Influenza still is in full swing with the CDC reporting high activity in 1 states for the week ending April 4th. Seasonal influenza, according to currently available data, has a lower fatality rate than COVID-19, but that doesn’t mean it is harmless. Thus far in the 2019-2020 flu season, there have been at least 24,000 deaths because of influenza in the United States alone, 166 of which were among pediatric patients.*

Like many pediatricians, I have seen firsthand the impact of vaccine-preventable illnesses like influenza, pertussis, and varicella. I have personally cared for an infant with pertussis who had to be intubated and on a ventilator for nearly a week. I have told the family of a child with cancer that they would have to be admitted to the hospital yet again for intravenous antiviral medication because that little rash turned out to be varicella. I have performed CPR on a previously healthy teenager with the flu whose heart was failing despite maximum ventilator support. All these illnesses might have been prevented had these patients or those around them been appropriately vaccinated.

Right now, the United States and governments around the world are taking unprecedented public health measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, directing the public to stay home, avoid unnecessary contact with other people, practice good hand-washing and infection-control techniques. In order to promote social distancing, many primary care clinics are canceling nonurgent appointments or converting them to virtual visits, including some visits for routine vaccinations for older children, teens, and adults. This is a responsible choice to keep potentially asymptomatic people from spreading COVID-19, but once restrictions begin to lift, we all will need to act to help our patients catch up on these missing vaccinations.

This pandemic has made it more apparent than ever that we all rely upon each other to stay healthy. While this pandemic has disrupted nearly every aspect of daily life, we can’t let it disrupt one of the great successes in health care today: the prevention of serious illnesses. As soon as it is safe to do so, we must help and encourage patients to catch up on missing vaccinations. It’s rare that preventative public health measures and vaccine developments are in the nightly news, so we should use this increased public awareness to ensure patients are well educated and protected from every disease. As part of this, we must continue our efforts to share accurate information on the safety and efficacy of routine vaccination. And when there is a vaccine for COVID-19? Let’s make sure everyone gets that too.

Dr. Leighton is a pediatrician in the ED at Children’s National Hospital and currently is completing her MPH in health policy at George Washington University, both in Washington. She had no relevant financial disclosures.*

* This article was updated 4/10/2020.

There is a highly infectious virus spreading around the world and it is targeting the most vulnerable among us. It is among the most contagious of human diseases, spreading through the air unseen. No, it isn’t the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. It’s measles.

Remember measles? Outbreaks in recent years have brought the disease, which once was declared eliminated in the United States, back into the news and public awareness, but measles never has really gone away. Every year there are millions of cases worldwide – in 2018 alone there were nearly 10 million estimated cases and 142,300 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. The good news is that measles vaccination is highly effective, at about 97% after the recommended two doses. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “because of vaccination, more than 21 million lives have been saved and measles deaths have been reduced by 80% since 2000.” This is a tremendous public health success and a cause for celebration. But our work is not done. The recent increases in vaccine hesitancy and refusal in many countries has contributed to the resurgence of measles worldwide.

Influenza still is in full swing with the CDC reporting high activity in 1 states for the week ending April 4th. Seasonal influenza, according to currently available data, has a lower fatality rate than COVID-19, but that doesn’t mean it is harmless. Thus far in the 2019-2020 flu season, there have been at least 24,000 deaths because of influenza in the United States alone, 166 of which were among pediatric patients.*

Like many pediatricians, I have seen firsthand the impact of vaccine-preventable illnesses like influenza, pertussis, and varicella. I have personally cared for an infant with pertussis who had to be intubated and on a ventilator for nearly a week. I have told the family of a child with cancer that they would have to be admitted to the hospital yet again for intravenous antiviral medication because that little rash turned out to be varicella. I have performed CPR on a previously healthy teenager with the flu whose heart was failing despite maximum ventilator support. All these illnesses might have been prevented had these patients or those around them been appropriately vaccinated.

Right now, the United States and governments around the world are taking unprecedented public health measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, directing the public to stay home, avoid unnecessary contact with other people, practice good hand-washing and infection-control techniques. In order to promote social distancing, many primary care clinics are canceling nonurgent appointments or converting them to virtual visits, including some visits for routine vaccinations for older children, teens, and adults. This is a responsible choice to keep potentially asymptomatic people from spreading COVID-19, but once restrictions begin to lift, we all will need to act to help our patients catch up on these missing vaccinations.

This pandemic has made it more apparent than ever that we all rely upon each other to stay healthy. While this pandemic has disrupted nearly every aspect of daily life, we can’t let it disrupt one of the great successes in health care today: the prevention of serious illnesses. As soon as it is safe to do so, we must help and encourage patients to catch up on missing vaccinations. It’s rare that preventative public health measures and vaccine developments are in the nightly news, so we should use this increased public awareness to ensure patients are well educated and protected from every disease. As part of this, we must continue our efforts to share accurate information on the safety and efficacy of routine vaccination. And when there is a vaccine for COVID-19? Let’s make sure everyone gets that too.

Dr. Leighton is a pediatrician in the ED at Children’s National Hospital and currently is completing her MPH in health policy at George Washington University, both in Washington. She had no relevant financial disclosures.*

* This article was updated 4/10/2020.

There is a highly infectious virus spreading around the world and it is targeting the most vulnerable among us. It is among the most contagious of human diseases, spreading through the air unseen. No, it isn’t the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. It’s measles.

Remember measles? Outbreaks in recent years have brought the disease, which once was declared eliminated in the United States, back into the news and public awareness, but measles never has really gone away. Every year there are millions of cases worldwide – in 2018 alone there were nearly 10 million estimated cases and 142,300 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. The good news is that measles vaccination is highly effective, at about 97% after the recommended two doses. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “because of vaccination, more than 21 million lives have been saved and measles deaths have been reduced by 80% since 2000.” This is a tremendous public health success and a cause for celebration. But our work is not done. The recent increases in vaccine hesitancy and refusal in many countries has contributed to the resurgence of measles worldwide.

Influenza still is in full swing with the CDC reporting high activity in 1 states for the week ending April 4th. Seasonal influenza, according to currently available data, has a lower fatality rate than COVID-19, but that doesn’t mean it is harmless. Thus far in the 2019-2020 flu season, there have been at least 24,000 deaths because of influenza in the United States alone, 166 of which were among pediatric patients.*

Like many pediatricians, I have seen firsthand the impact of vaccine-preventable illnesses like influenza, pertussis, and varicella. I have personally cared for an infant with pertussis who had to be intubated and on a ventilator for nearly a week. I have told the family of a child with cancer that they would have to be admitted to the hospital yet again for intravenous antiviral medication because that little rash turned out to be varicella. I have performed CPR on a previously healthy teenager with the flu whose heart was failing despite maximum ventilator support. All these illnesses might have been prevented had these patients or those around them been appropriately vaccinated.

Right now, the United States and governments around the world are taking unprecedented public health measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, directing the public to stay home, avoid unnecessary contact with other people, practice good hand-washing and infection-control techniques. In order to promote social distancing, many primary care clinics are canceling nonurgent appointments or converting them to virtual visits, including some visits for routine vaccinations for older children, teens, and adults. This is a responsible choice to keep potentially asymptomatic people from spreading COVID-19, but once restrictions begin to lift, we all will need to act to help our patients catch up on these missing vaccinations.

This pandemic has made it more apparent than ever that we all rely upon each other to stay healthy. While this pandemic has disrupted nearly every aspect of daily life, we can’t let it disrupt one of the great successes in health care today: the prevention of serious illnesses. As soon as it is safe to do so, we must help and encourage patients to catch up on missing vaccinations. It’s rare that preventative public health measures and vaccine developments are in the nightly news, so we should use this increased public awareness to ensure patients are well educated and protected from every disease. As part of this, we must continue our efforts to share accurate information on the safety and efficacy of routine vaccination. And when there is a vaccine for COVID-19? Let’s make sure everyone gets that too.

Dr. Leighton is a pediatrician in the ED at Children’s National Hospital and currently is completing her MPH in health policy at George Washington University, both in Washington. She had no relevant financial disclosures.*

* This article was updated 4/10/2020.

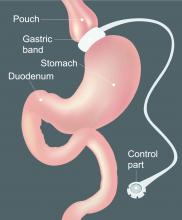

The hospitalized postbariatric surgery patient

What every hospitalist should know

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

What every hospitalist should know

What every hospitalist should know

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

COVID-19 in China: Children have less severe disease, but are vulnerable

Clinical manifestations of COVID-19 infection among children in mainland China generally have been less severe than those among adults, but children of all ages – and infants in particular – are vulnerable to infection, according to a review of 2,143 cases.

Further, infection patterns in the nationwide series of all pediatric patients reported to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention from Jan. 16 to Feb. 8, 2020, provide strong evidence of human-to-human transmission, Yuanyuan Dong, MPH, a research assistant at Shanghai Children’s Medical Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China, and colleagues reported in Pediatrics.

Of the 2,143 patients included in the review, 57% were boys and the median age was 7 years; 34% had laboratory-confirmed infection and 67% had suspected infection. More than 90% had asymptomatic, mild, or moderate disease (4%, 51%, and 39%, respectively), and 46% were from Hubei Province, where the first cases were reported, the investigators found.

The median time from illness onset to diagnosis was 2 days, and there was a trend of rapid increase of disease at the early stage of the epidemic – with rapid spread from Hubei Province to surrounding provinces – followed by a gradual and steady decrease, they noted.

“The total number of pediatric patients increased remarkably between mid-January and early February, peaked around February 1, and then declined since early February 2020,” they wrote. The proportion of severe and critical cases was 11% for infants under 1 year of age, compared with 7% for those aged 1-5 years; 4% for those aged 6-10 years; 4% for those 11-15 years; and 3% for those 16 years and older.

As of Feb. 8, 2020, only one child in this group of study patients died and most cases of COVID-19 symptoms were mild. There were many fewer severe and critical cases among the children (6%), compared with those reported in adult patients in other studies (19%). “It suggests that, compared with adult patients, clinical manifestations of children’s COVID-19 may be less severe,” the investigators suggested.

“As most of these children were likely to expose themselves to family members and/or other children with COVID-19, it clearly indicates person-to-person transmission ” of novel coronavirus 2019, they said, adding that similar evidence of such transmission also has been reported from studies of adult patients.

The reasons for reduced severity in children versus adults remain unclear, but may be related to both exposure and host factors, Ms. Dong and associates said. “Children were usually well cared for at home and might have relatively [fewer] opportunities to expose themselves to pathogens and/or sick patients.”

The findings demonstrate a pediatric distribution that varied across time and space, with most cases concentrated in the Hubei province and surrounding areas. No significant gender-related difference in infection rates was observed, and although the median patient age was 7 years, the range was 1 day to 18 years, suggesting that “all ages at childhood were susceptible” to the virus, they added.

The declining number of cases over time further suggests that disease control measures implemented by the government were effective, and that cases will “continue to decline, and finally stop in the near future unless sustained human-to-human transmissions occur,” Ms. Dong and associates concluded.