User login

Financial Empowerment Journey

Dear Friends,

One of the challenges I faced during training was managing my life outside of work. Many astute trainees started their financial empowerment journey early. However, I was too overwhelmed with what I did not know (the financial world) and just avoided it. Over the last year, I finally decided to embrace my lack of knowledge and find the support of experts, just as we would in medicine. A lot of questions from my journey translated into several articles in the “Finance” section of The New Gastroenterologist, so I encourage those who need guidance on embarking on their financial journeys to explore that section!

In the “In Focus” section, Dr. Patrick Chang, Dr. Supisara Tintara, and Dr. Jennifer Phan – all from the University of Southern California – review diagnostic modalities to assess gastroesophageal reflux disease with an emphasis on medical, endoscopic, and surgical managements.

With the rise in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), patient education is starting in the primary care and gastroenterologist’s office. Dr. Newsha Nikzad, medical student Daniel Huynh, and Dr. Nikki Duong share their approach to ask effectively about and communicate lifestyle modifications, with examples of using sensitive language and prompts to help guide patients, in the “Short Clinical Review” section.

The “Finance” section highlights the ins and outs of a physician mortgage loan and additional information for first time home buyers, reviewed by John G. Kelley II, a physician mortgage specialist and vice president of mortgage lending at Arvest Bank.

Lastly, in the “Early Career” section, Dr. Neil Gupta shares his experiences of transitioning from academic medicine to building a private practice group. He reflects on lessons learned from the first year after establishing his practice.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The first proton pump inhibitor was omeprazole, discovered 45 years ago in 1979 in Sweden, and clinically available in the United States only 36 years ago in 1988.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

One of the challenges I faced during training was managing my life outside of work. Many astute trainees started their financial empowerment journey early. However, I was too overwhelmed with what I did not know (the financial world) and just avoided it. Over the last year, I finally decided to embrace my lack of knowledge and find the support of experts, just as we would in medicine. A lot of questions from my journey translated into several articles in the “Finance” section of The New Gastroenterologist, so I encourage those who need guidance on embarking on their financial journeys to explore that section!

In the “In Focus” section, Dr. Patrick Chang, Dr. Supisara Tintara, and Dr. Jennifer Phan – all from the University of Southern California – review diagnostic modalities to assess gastroesophageal reflux disease with an emphasis on medical, endoscopic, and surgical managements.

With the rise in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), patient education is starting in the primary care and gastroenterologist’s office. Dr. Newsha Nikzad, medical student Daniel Huynh, and Dr. Nikki Duong share their approach to ask effectively about and communicate lifestyle modifications, with examples of using sensitive language and prompts to help guide patients, in the “Short Clinical Review” section.

The “Finance” section highlights the ins and outs of a physician mortgage loan and additional information for first time home buyers, reviewed by John G. Kelley II, a physician mortgage specialist and vice president of mortgage lending at Arvest Bank.

Lastly, in the “Early Career” section, Dr. Neil Gupta shares his experiences of transitioning from academic medicine to building a private practice group. He reflects on lessons learned from the first year after establishing his practice.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The first proton pump inhibitor was omeprazole, discovered 45 years ago in 1979 in Sweden, and clinically available in the United States only 36 years ago in 1988.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

One of the challenges I faced during training was managing my life outside of work. Many astute trainees started their financial empowerment journey early. However, I was too overwhelmed with what I did not know (the financial world) and just avoided it. Over the last year, I finally decided to embrace my lack of knowledge and find the support of experts, just as we would in medicine. A lot of questions from my journey translated into several articles in the “Finance” section of The New Gastroenterologist, so I encourage those who need guidance on embarking on their financial journeys to explore that section!

In the “In Focus” section, Dr. Patrick Chang, Dr. Supisara Tintara, and Dr. Jennifer Phan – all from the University of Southern California – review diagnostic modalities to assess gastroesophageal reflux disease with an emphasis on medical, endoscopic, and surgical managements.

With the rise in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), patient education is starting in the primary care and gastroenterologist’s office. Dr. Newsha Nikzad, medical student Daniel Huynh, and Dr. Nikki Duong share their approach to ask effectively about and communicate lifestyle modifications, with examples of using sensitive language and prompts to help guide patients, in the “Short Clinical Review” section.

The “Finance” section highlights the ins and outs of a physician mortgage loan and additional information for first time home buyers, reviewed by John G. Kelley II, a physician mortgage specialist and vice president of mortgage lending at Arvest Bank.

Lastly, in the “Early Career” section, Dr. Neil Gupta shares his experiences of transitioning from academic medicine to building a private practice group. He reflects on lessons learned from the first year after establishing his practice.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]) or Danielle Kiefer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The first proton pump inhibitor was omeprazole, discovered 45 years ago in 1979 in Sweden, and clinically available in the United States only 36 years ago in 1988.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Aliens, Ian McShane, and Heart Disease Risk

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

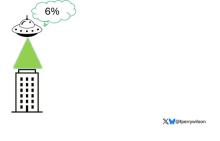

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

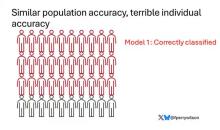

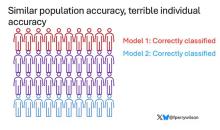

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A Portrait of the Patient

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

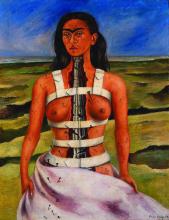

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

Gentle Parenting

In one my recent Letters, I concluded with the concern that infant-led weaning, which makes some sense, can be confused with child-led family meals, which make none. I referred to an increasingly popular style of parenting overemphasizing child autonomy that seems to be a major contributor to the mealtime chaos that occurs when pleasing every palate at the table becomes the goal.

In the intervening weeks, I have learned that this parenting style is called “gentle parenting.” Despite its growing popularity, possibly fueled by the pandemic, it has not been well-defined nor its effectiveness investigated. In a recent paper published in PLOS ONE, two professors of developmental psychology have attempted correct this deficit in our understanding of this parenting style, which doesn’t appear to make sense to many of us with experience in child behavior and development.

Gentle Parents

By surveying a group of 100 parents of young children, the investigators were able to sort out a group of parents (n = 49) who self-identified as employing gentle parenting. Their responses emphasized a high level of parental affection and emotional regulation by both their children and themselves.

Investigators found that 40% of the self-defined gentle parents “had negative difference scores indicating misbehavior response descriptions that included more child directed responses. I interpret this to mean that almost half of the time the parents failed to evenly include themselves in a solution to a conflict, which indicates incomplete or unsuccessful emotional regulation on their part. The investigators also observed that, like many other parenting styles, gentle parenting includes an emphasis on boundaries “yet, enactment of those boundaries is not uniform.”

More telling was the authors’ observation that “statements of parenting uncertainty and burnout were present in over one third of the gentle of the gentle parenting sample.” While some parents were pleased with their experience, the downside seems unacceptable to me. When asked to explain this finding, Annie Pezalla, PhD, one of the coauthors, has said “gentle parenting practices work best when a parent is emotionally regulated and unconstrained for time — commodities that parents struggle with the most.”

Abundance Advice on Parenting Styles

I find this to be a very sad story. Parenting can be difficult. Creating and then gently and effectively policing those boundaries is often the hardest part. It is not surprising to me that of the four books I have written for parents, the one titled How to Say No to Your Toddler is the only one popular enough to be published in four languages.

Of course I am troubled, as I suspect you may be, with the label “gentle parenting.” It implies that the rest of us are doing something terrible, “harsh” maybe, “cruel” maybe. We can dispense with the “affectionate” descriptor immediately because gentle parenting can’t claim sole ownership to it. Every, behavior management scheme I am aware of touts being caring and loving at its core.

I completely agree that emotional regulation for both parent and child are worthy goals, but I’m not hearing much on how that is to be achieved other than by trying to avoid the inevitable conflict by failing to even say “No” when poorly crafted boundaries are breached.

There are scores of parenting styles out there. And there should be, because we are all different. Parents have strengths and weaknesses and they have begotten children with different personalities and vulnerabilities. And, families come from different cultures and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Across all of these differences there are two primary roles for every parent. The first is to lead by example. If a parent wants his/her child to be kind and caring and polite, then the parent has no choice but to behave that way. If the parent can’t always be present, the environment where the child spends most of his/her day should model the desired behavior. I’m not talking about teaching because you can’t preach good behavior. It must be modeled.

The second role for the parent is to keep his/her child safe from dangers that exist in every environment. This can mean accepting vaccines and seeking available medical care. But, it also means creating some limits — the current buzzword is “guardrails” — to keep the child from veering into the ditch.

Setting Limits

Limits will, of necessity, vary with the environment. The risks of a child growing on a farm differ from those of child living in the city. And they must be tailored to the personality and developmental stage of the child. A parent may need advice from someone experienced in child behavior to create individualized limits. You may be able to allow your 3-year-old to roam freely in an environment in which I would have to monitor my risk-taking 3-year-old every second. A parent must learn and accept his/her child’s personality and the environment they can provide.

Limits should be inanimate objects whenever possible. Fences, gates, doors with latches, and locked cabinets to keep temptations out of view, etc. Creative environmental manipulations should be employed to keep the annoying verbal warnings, unenforceable threats, and direct child-to-parent confrontations to a minimum.

Consequences

Challenges to even the most carefully crafted limits are inevitable, and this is where we get to the third-rail topic of consequences. Yes, when prevention has failed for whatever reason, I believe that an intelligently and affectionately applied time-out is the most efficient and most effective consequence. This is not the place for me to explore or defend the details, but before you write me off as an octogenarian hard-ass (or hard-liner if you prefer) I urge you to read a few chapters in How to Say No to Your Toddler.

Far more important than which consequence a parent chooses are the steps the family has taken to keep both parent and child in a state of balanced emotional regulation. Is everyone well rested and getting enough sleep? Sleep deprivation is one of the most potent triggers of a tantrum; it also leaves parents vulnerable to saying things and making threats they will regret later. Does the child’s schedule leave him or her enough time to decompress? Does the parent’s schedule sync with a developmentally appropriate schedule for the child? Is he/she getting the right kind of attention when it makes the most sense to him/her?

Intelligent Parenting

If a family has created an environment in which limits are appropriate for the child’s personality and developmental stage, used physical barriers whenever possible, and kept everyone as well rested as possible, both challenges to the limits and consequences can be kept to a minimum.

But achieving this state requires time as free of constraints as possible. For the few families that have the luxury of meeting these conditions, gentle parenting might be the answer. For the rest of us, intelligent parenting that acknowledges the realities and limits of our own abilities and our children’s vulnerabilities is the better answer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

In one my recent Letters, I concluded with the concern that infant-led weaning, which makes some sense, can be confused with child-led family meals, which make none. I referred to an increasingly popular style of parenting overemphasizing child autonomy that seems to be a major contributor to the mealtime chaos that occurs when pleasing every palate at the table becomes the goal.

In the intervening weeks, I have learned that this parenting style is called “gentle parenting.” Despite its growing popularity, possibly fueled by the pandemic, it has not been well-defined nor its effectiveness investigated. In a recent paper published in PLOS ONE, two professors of developmental psychology have attempted correct this deficit in our understanding of this parenting style, which doesn’t appear to make sense to many of us with experience in child behavior and development.

Gentle Parents

By surveying a group of 100 parents of young children, the investigators were able to sort out a group of parents (n = 49) who self-identified as employing gentle parenting. Their responses emphasized a high level of parental affection and emotional regulation by both their children and themselves.

Investigators found that 40% of the self-defined gentle parents “had negative difference scores indicating misbehavior response descriptions that included more child directed responses. I interpret this to mean that almost half of the time the parents failed to evenly include themselves in a solution to a conflict, which indicates incomplete or unsuccessful emotional regulation on their part. The investigators also observed that, like many other parenting styles, gentle parenting includes an emphasis on boundaries “yet, enactment of those boundaries is not uniform.”

More telling was the authors’ observation that “statements of parenting uncertainty and burnout were present in over one third of the gentle of the gentle parenting sample.” While some parents were pleased with their experience, the downside seems unacceptable to me. When asked to explain this finding, Annie Pezalla, PhD, one of the coauthors, has said “gentle parenting practices work best when a parent is emotionally regulated and unconstrained for time — commodities that parents struggle with the most.”

Abundance Advice on Parenting Styles

I find this to be a very sad story. Parenting can be difficult. Creating and then gently and effectively policing those boundaries is often the hardest part. It is not surprising to me that of the four books I have written for parents, the one titled How to Say No to Your Toddler is the only one popular enough to be published in four languages.

Of course I am troubled, as I suspect you may be, with the label “gentle parenting.” It implies that the rest of us are doing something terrible, “harsh” maybe, “cruel” maybe. We can dispense with the “affectionate” descriptor immediately because gentle parenting can’t claim sole ownership to it. Every, behavior management scheme I am aware of touts being caring and loving at its core.

I completely agree that emotional regulation for both parent and child are worthy goals, but I’m not hearing much on how that is to be achieved other than by trying to avoid the inevitable conflict by failing to even say “No” when poorly crafted boundaries are breached.

There are scores of parenting styles out there. And there should be, because we are all different. Parents have strengths and weaknesses and they have begotten children with different personalities and vulnerabilities. And, families come from different cultures and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Across all of these differences there are two primary roles for every parent. The first is to lead by example. If a parent wants his/her child to be kind and caring and polite, then the parent has no choice but to behave that way. If the parent can’t always be present, the environment where the child spends most of his/her day should model the desired behavior. I’m not talking about teaching because you can’t preach good behavior. It must be modeled.

The second role for the parent is to keep his/her child safe from dangers that exist in every environment. This can mean accepting vaccines and seeking available medical care. But, it also means creating some limits — the current buzzword is “guardrails” — to keep the child from veering into the ditch.

Setting Limits

Limits will, of necessity, vary with the environment. The risks of a child growing on a farm differ from those of child living in the city. And they must be tailored to the personality and developmental stage of the child. A parent may need advice from someone experienced in child behavior to create individualized limits. You may be able to allow your 3-year-old to roam freely in an environment in which I would have to monitor my risk-taking 3-year-old every second. A parent must learn and accept his/her child’s personality and the environment they can provide.

Limits should be inanimate objects whenever possible. Fences, gates, doors with latches, and locked cabinets to keep temptations out of view, etc. Creative environmental manipulations should be employed to keep the annoying verbal warnings, unenforceable threats, and direct child-to-parent confrontations to a minimum.

Consequences

Challenges to even the most carefully crafted limits are inevitable, and this is where we get to the third-rail topic of consequences. Yes, when prevention has failed for whatever reason, I believe that an intelligently and affectionately applied time-out is the most efficient and most effective consequence. This is not the place for me to explore or defend the details, but before you write me off as an octogenarian hard-ass (or hard-liner if you prefer) I urge you to read a few chapters in How to Say No to Your Toddler.

Far more important than which consequence a parent chooses are the steps the family has taken to keep both parent and child in a state of balanced emotional regulation. Is everyone well rested and getting enough sleep? Sleep deprivation is one of the most potent triggers of a tantrum; it also leaves parents vulnerable to saying things and making threats they will regret later. Does the child’s schedule leave him or her enough time to decompress? Does the parent’s schedule sync with a developmentally appropriate schedule for the child? Is he/she getting the right kind of attention when it makes the most sense to him/her?

Intelligent Parenting

If a family has created an environment in which limits are appropriate for the child’s personality and developmental stage, used physical barriers whenever possible, and kept everyone as well rested as possible, both challenges to the limits and consequences can be kept to a minimum.

But achieving this state requires time as free of constraints as possible. For the few families that have the luxury of meeting these conditions, gentle parenting might be the answer. For the rest of us, intelligent parenting that acknowledges the realities and limits of our own abilities and our children’s vulnerabilities is the better answer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

In one my recent Letters, I concluded with the concern that infant-led weaning, which makes some sense, can be confused with child-led family meals, which make none. I referred to an increasingly popular style of parenting overemphasizing child autonomy that seems to be a major contributor to the mealtime chaos that occurs when pleasing every palate at the table becomes the goal.

In the intervening weeks, I have learned that this parenting style is called “gentle parenting.” Despite its growing popularity, possibly fueled by the pandemic, it has not been well-defined nor its effectiveness investigated. In a recent paper published in PLOS ONE, two professors of developmental psychology have attempted correct this deficit in our understanding of this parenting style, which doesn’t appear to make sense to many of us with experience in child behavior and development.

Gentle Parents

By surveying a group of 100 parents of young children, the investigators were able to sort out a group of parents (n = 49) who self-identified as employing gentle parenting. Their responses emphasized a high level of parental affection and emotional regulation by both their children and themselves.

Investigators found that 40% of the self-defined gentle parents “had negative difference scores indicating misbehavior response descriptions that included more child directed responses. I interpret this to mean that almost half of the time the parents failed to evenly include themselves in a solution to a conflict, which indicates incomplete or unsuccessful emotional regulation on their part. The investigators also observed that, like many other parenting styles, gentle parenting includes an emphasis on boundaries “yet, enactment of those boundaries is not uniform.”

More telling was the authors’ observation that “statements of parenting uncertainty and burnout were present in over one third of the gentle of the gentle parenting sample.” While some parents were pleased with their experience, the downside seems unacceptable to me. When asked to explain this finding, Annie Pezalla, PhD, one of the coauthors, has said “gentle parenting practices work best when a parent is emotionally regulated and unconstrained for time — commodities that parents struggle with the most.”

Abundance Advice on Parenting Styles

I find this to be a very sad story. Parenting can be difficult. Creating and then gently and effectively policing those boundaries is often the hardest part. It is not surprising to me that of the four books I have written for parents, the one titled How to Say No to Your Toddler is the only one popular enough to be published in four languages.

Of course I am troubled, as I suspect you may be, with the label “gentle parenting.” It implies that the rest of us are doing something terrible, “harsh” maybe, “cruel” maybe. We can dispense with the “affectionate” descriptor immediately because gentle parenting can’t claim sole ownership to it. Every, behavior management scheme I am aware of touts being caring and loving at its core.

I completely agree that emotional regulation for both parent and child are worthy goals, but I’m not hearing much on how that is to be achieved other than by trying to avoid the inevitable conflict by failing to even say “No” when poorly crafted boundaries are breached.

There are scores of parenting styles out there. And there should be, because we are all different. Parents have strengths and weaknesses and they have begotten children with different personalities and vulnerabilities. And, families come from different cultures and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Across all of these differences there are two primary roles for every parent. The first is to lead by example. If a parent wants his/her child to be kind and caring and polite, then the parent has no choice but to behave that way. If the parent can’t always be present, the environment where the child spends most of his/her day should model the desired behavior. I’m not talking about teaching because you can’t preach good behavior. It must be modeled.

The second role for the parent is to keep his/her child safe from dangers that exist in every environment. This can mean accepting vaccines and seeking available medical care. But, it also means creating some limits — the current buzzword is “guardrails” — to keep the child from veering into the ditch.

Setting Limits

Limits will, of necessity, vary with the environment. The risks of a child growing on a farm differ from those of child living in the city. And they must be tailored to the personality and developmental stage of the child. A parent may need advice from someone experienced in child behavior to create individualized limits. You may be able to allow your 3-year-old to roam freely in an environment in which I would have to monitor my risk-taking 3-year-old every second. A parent must learn and accept his/her child’s personality and the environment they can provide.

Limits should be inanimate objects whenever possible. Fences, gates, doors with latches, and locked cabinets to keep temptations out of view, etc. Creative environmental manipulations should be employed to keep the annoying verbal warnings, unenforceable threats, and direct child-to-parent confrontations to a minimum.

Consequences

Challenges to even the most carefully crafted limits are inevitable, and this is where we get to the third-rail topic of consequences. Yes, when prevention has failed for whatever reason, I believe that an intelligently and affectionately applied time-out is the most efficient and most effective consequence. This is not the place for me to explore or defend the details, but before you write me off as an octogenarian hard-ass (or hard-liner if you prefer) I urge you to read a few chapters in How to Say No to Your Toddler.

Far more important than which consequence a parent chooses are the steps the family has taken to keep both parent and child in a state of balanced emotional regulation. Is everyone well rested and getting enough sleep? Sleep deprivation is one of the most potent triggers of a tantrum; it also leaves parents vulnerable to saying things and making threats they will regret later. Does the child’s schedule leave him or her enough time to decompress? Does the parent’s schedule sync with a developmentally appropriate schedule for the child? Is he/she getting the right kind of attention when it makes the most sense to him/her?

Intelligent Parenting

If a family has created an environment in which limits are appropriate for the child’s personality and developmental stage, used physical barriers whenever possible, and kept everyone as well rested as possible, both challenges to the limits and consequences can be kept to a minimum.

But achieving this state requires time as free of constraints as possible. For the few families that have the luxury of meeting these conditions, gentle parenting might be the answer. For the rest of us, intelligent parenting that acknowledges the realities and limits of our own abilities and our children’s vulnerabilities is the better answer.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Navigating the Physician Mortgage Loan

Navigating the path to homeownership can be particularly challenging for physicians, who often face a unique set of financial circumstances. With substantial student loan debt, limited savings, and a delayed peak earning potential, traditional mortgage options may seem out of reach.

Enter physician mortgage loans—specialized financing designed specifically for medical professionals. These loans offer tailored solutions that address the common barriers faced by doctors, making it easier for them to achieve their homeownership goals. In this article, we’ll

What Is a Physician Mortgage Loan?

A physician mortgage loan, also known as a ‘doctor loan,’ is a specialized mortgage product designed for a specific group of qualifying medical professionals. These loans are particularly attractive to new doctors who may have substantial student loan debt, limited savings, and an income that is expected to increase significantly over time. As unique portfolio loans, physician mortgage products can vary considerably between lending institutions. However, a common feature is that they typically require little to no down payment and do not require private mortgage insurance (PMI).

Beyond the common features, loan options and qualifying parameters can vary significantly from one institution to another. Therefore, it’s important to start gathering information as early as possible, giving you ample time to evaluate which institution and loan option best meet your needs.

How Do I Know if I Am Eligible for a Physician Mortgage Loan?

Physician loans are typically offered to MDs, DOs, DDSs, DMDs, and ODs, though some institutions expand this list to include DPMs, PAs, CRNAs, NPs, PharmDs, and DVMs. Additionally, most of these loan products are available to residents, fellows, and attending or practicing physicians.

How Do I Know What Physician Mortgage Loan Is Best for Me?

When selecting the optimal physician loan option for your home purchase, consider several important metrics:

- Duration of Stay: Consider how long you expect to live in the home. If you’re in a lengthy residency or fellowship program, or if you plan to move for a new job soon after, a 30-year fixed-rate loan might not be ideal. Instead, evaluate loan options that match your anticipated duration of stay. For example, a 5-year or 7-year ARM (adjustable rate mortgage) could offer a lower interest rate and reduced monthly payments for the initial fixed period, which aligns with your shorter-term stay. This can result in substantial savings if you do not plan to stay in the home for the full term of a traditional mortgage.

- Underwriting Guidelines: Each lender has different underwriting standards and qualifying criteria, so it’s essential to understand these differences. For instance, some lenders may have higher minimum credit score requirements or stricter debt-to-income (DTI) ratio limits. Others might require a larger down payment or have different rules regarding student loan payments and closing costs. Flexibility in these guidelines can impact your ability to qualify for a loan and the terms you receive. For example, some lenders may allow you to include student loan payments at a lower percentage of your income, which could improve your DTI ratio and help you secure a better loan offer.

- Closing Timing: The timing of your home closing relative to your job start date can be crucial, especially if you’re relocating. Some lenders permit closing up to 60-90 days before your job begins, while others offer up to 120 days. If you need to relocate your family before starting your new position, having the ability to close earlier can provide you with more flexibility in finding and moving into a home. This additional time can ease the transition and allow you to settle in before your new job starts.

Given the wide range of options and standards, it’s important to strategically identify which factors are most meaningful to you. Beyond interest rates, consider the overall cost of the loan, the flexibility of terms, and how well the loan aligns with your financial goals and career plans. For example, if you value lower monthly payments over a longer period or need to accommodate significant student loan debt, ensure that the loan program you choose aligns with these priorities.

What Attributes Should I Look for in My Loan Officer?

When interviewing multiple loan officers for your upcoming loan needs, it’s essential to use the right metrics—beyond just the interest rate—to determine the best fit for your situation. Some critical factors to consider include the loan officer’s experience working with physicians, that person’s availability and responsiveness, and the potential for building a long-term relationship.

As in most professions, experience is paramount—it’s something that cannot be taught or simply read in a training manual. Physicians, especially those in training or just stepping into an attending role, often have unique financial situations. This makes it crucial to work with a loan officer who has extensive experience serving physician clients. An experienced loan officer will better understand how to customize a loan solution that aligns with your specific needs, resulting in a much more tailored and meaningful mortgage. There is no one-size-fits-all mortgage. You are unique, and your loan officer should be crafting a mortgage solution that reflects your individuality and financial circumstances.

In my opinion, availability and responsiveness are among the most critical attributes your chosen loan officer should possess. Interestingly, this factor doesn’t directly influence the ‘cost’ of your loan but can significantly impact your experience. As a physician with a demanding schedule, it’s unrealistic to expect that all communication will take place strictly during business hours—this is true for any consumer. Pay close attention to how promptly loan officers respond during your initial interactions, and evaluate how thoroughly they explain loan terms, out-of-pocket costs, and the overall loan process. Your loan officer should be your trusted guide as you navigate through the complexities of the loan process, so setting yourself up for success starts with choosing someone who meets your expectations in this regard.

It’s crucial to build a good rapport with the loan officer you choose, as this likely won’t be the last mortgage or financial need you encounter in your lifetime. Establishing a personal connection with your loan officer fosters a level of trust that is invaluable. Whether you’re considering refinancing your current mortgage or exploring additional loan products for other financial needs, having a trusted advisor you can rely on as a financial resource is immensely beneficial as you progress in your career. A strong, long-standing relationship with a loan officer ensures you receive reliable and sound financial advice tailored to your unique needs.

Additional Things to Consider if You Are a First-Time Home Buyer

Interview multiple lenders and make those conversations about more than just interest rates. This approach will help you gauge their knowledge of physician mortgage loans while allowing you to assess who might be the best fit for you in terms of compatibility. Relying solely on an email blast to inquire about rates could easily lead you to a subpar lender and result in an unfavorable experience.

Don’t be afraid to ask a lot of questions! As a first-time home buyer, it’s natural to feel a bit overwhelmed by the process—it can seem daunting if you’ve never been through it before. That’s why it’s crucial to ask any questions that come to mind and to work with a lender who is willing to take the time to answer them while educating you throughout the home-buying journey. With a trusted guide and the right education, the process will feel far less overwhelming, leading to a smoother and more positive experience from start to finish.

In conclusion, choosing the right lender for a physician mortgage loan is a crucial step in securing your financial future and achieving homeownership. By thoroughly evaluating interest rates, down payment requirements, loan terms, and other key metrics, you can find a lender that offers competitive rates and favorable terms tailored to your unique needs. Consider factors such as customer service, closing costs, and the lender’s experience with physician loans to ensure a smooth and supportive mortgage process. By taking the time to compare options and select the best fit for your financial situation, you can confidently move forward in your home-buying journey and set the stage for a successful and fulfilling homeownership experience.

Mr. Kelley is vice president of mortgage lending and a physician mortgage specialist at Arvest Bank in Overland Park, Kansas.

Navigating the path to homeownership can be particularly challenging for physicians, who often face a unique set of financial circumstances. With substantial student loan debt, limited savings, and a delayed peak earning potential, traditional mortgage options may seem out of reach.

Enter physician mortgage loans—specialized financing designed specifically for medical professionals. These loans offer tailored solutions that address the common barriers faced by doctors, making it easier for them to achieve their homeownership goals. In this article, we’ll

What Is a Physician Mortgage Loan?

A physician mortgage loan, also known as a ‘doctor loan,’ is a specialized mortgage product designed for a specific group of qualifying medical professionals. These loans are particularly attractive to new doctors who may have substantial student loan debt, limited savings, and an income that is expected to increase significantly over time. As unique portfolio loans, physician mortgage products can vary considerably between lending institutions. However, a common feature is that they typically require little to no down payment and do not require private mortgage insurance (PMI).

Beyond the common features, loan options and qualifying parameters can vary significantly from one institution to another. Therefore, it’s important to start gathering information as early as possible, giving you ample time to evaluate which institution and loan option best meet your needs.

How Do I Know if I Am Eligible for a Physician Mortgage Loan?

Physician loans are typically offered to MDs, DOs, DDSs, DMDs, and ODs, though some institutions expand this list to include DPMs, PAs, CRNAs, NPs, PharmDs, and DVMs. Additionally, most of these loan products are available to residents, fellows, and attending or practicing physicians.

How Do I Know What Physician Mortgage Loan Is Best for Me?