User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

SPF is only the start when recommending sunscreens

CHICAGO – at the inaugural Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

Among the first factors physicians should consider before recommending sunscreen are a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type, risks for burning or tanning, underlying skin disorders, and medications the patient is taking, Dr. Taylor, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! If patients are on hypertensives, for example, medications can make them more photosensitive.

Consider skin type

Dr. Taylor said she was dismayed by the results of a recent study, which found that 43% of dermatologists who responded to a survey reported that they never, rarely, or only sometimes took a patient’s skin type into account when making sunscreen recommendations. The article is referenced in a 2022 expert panel consensus paper she coauthored on photoprotection “for skin of all color.” But she pointed out that considering skin type alone is inadequate.

Questions for patients in joint decision-making should include lifestyle and work choices such as whether they work inside or outside, and how much sun exposure they get in a typical day. Heat and humidity levels should also be considered as should a patient’s susceptibility to dyspigmentation. “That could be overall darkening of the skin, mottled hyperpigmentation, actinic dyspigmentation, and, of course, propensity for skin cancer,” she said.

Use differs by race

Dr. Taylor, who is also vice chair for diversity, equity and inclusion in the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, pointed out that sunscreen use differs considerably by race.

In study of 8,952 adults in the United States who reported that they were sun sensitive found that a subset of adults with skin of color were significantly less likely to use sunscreen when compared with non-Hispanic White adults: Non-Hispanic Black (adjusted odds ratio, 0.43); non-Hispanic Asian (aOR. 0.54); and Hispanic (aOR, 0.70) adults.

In the study, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults were significantly less likely to use sunscreens with an SPF greater than 15. In addition, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic adults were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to wear long sleeves when outside. Such differences are important to keep in mind when advising patients about sunscreens, she said.

Protection for lighter-colored skin

Dr. Taylor said that, for patients with lighter skin tones, “we really want to protect against ultraviolet B as well as ultraviolet A, particularly ultraviolet A2. Ultraviolet radiation is going to cause DNA damage.” Patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I, II, or III are most susceptible to the effects of UVB with sunburn inflammation, which will cause erythema and tanning, and immunosuppression.

“For those who are I, II, and III, we do want to recommend a broad-spectrum, photostable sunscreen with a critical wavelength of 370 nanometers, which is going to protect from both UVB and UVA2,” she said.

Sunscreen recommendations are meant to be paired with advice to avoid midday sun from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., wearing protective clothing and accessories, and seeking shade, she noted.

Dr. Taylor said, for those patients with lighter skin who are more susceptible to photodamage and premature aging, physicians should recommend sunscreens that contain DNA repair enzymes such as photolyases and sunscreens that contain antioxidants that can prevent or reverse DNA damage. “The exogenous form of these lyases have been manufactured and added to sunscreens,” Dr. Taylor said. “They’re readily available in the United States. That is something to consider for patients with significant photodamage.”

Retinoids can also help alleviate or reverse photodamage, she added.

Protection for darker-colored skin

“Many people of color do not believe they need sunscreen,” Dr. Taylor said. But studies show that, although there may be more intrinsic protection, sunscreen is still needed.

Over 30 years ago, Halder and colleagues reported that melanin in skin of color can filter two to five times more UV radiation, and in a paper on the photoprotective role of melanin, Kaidbey and colleagues found that skin types V and VI had an intrinsic SPF of 13 when compared with those who have lighter complexions, which had an SPF of 3.

Sunburns seem to occur less frequently in people with skin of color, but that may be because erythema is less apparent in people with darker skin tones or because of differences in personal definitions of sunburn, Dr. Taylor said.

“Skin of color can and does sustain sunburns and sunscreen will help prevent that,” she said, adding that a recommendation of an SPF 30 is likely sufficient for these patients. Dr. Taylor noted that sunscreens for patients with darker skin often cost substantially more than those for lighter skin, and that should be considered in recommendations.

Tinted sunscreens

Dr. Taylor said that, while broad-spectrum photostable sunscreens protect against UVB and UVA 2, they don’t protect from visible light and UVA1. Two methods to add that protection are using inorganic tinted sunscreens that contain iron oxide or pigmentary titanium dioxide. Dr. Taylor was a coauthor of a practical guide to tinted sunscreens published in 2022.

“For iron oxide, we want a concentration of 3% or greater,” she said, adding that the percentage often is not known because if it is contained in a sunscreen, it is listed as an inactive ingredient.

Another method to address visible light and UVA1 is the use of antioxidant-containing sunscreens with vitamin E, vitamin C, or licochalcone A, Dr. Taylor said.

During the question-and-answer period following her presentation, Amit Pandya, MD, adjunct professor of dermatology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, asked why “every makeup, every sunscreen, just says iron oxide,” since it is known that visible light will cause pigmentation, especially in those with darker skin tones.

He urged pushing for a law that would require listing the percentage of iron oxide on products to assure it is sufficient, according to what the literature recommends.

Conference Chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of the Vitiligo and Pigmentation Institute of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that she recommends tinted sunscreens almost exclusively for her patients, but those with darker skin colors struggle to match color.

Dr. Taylor referred to an analysis published in 2022 of 58 over-the counter sunscreens, which found that only 38% of tinted sunscreens was available in more than one shade, “which is a problem for many of our patients.” She said that providing samples with different hues and tactile sensations may help patients find the right product.

Dr. Taylor disclosed being on the advisory boards for AbbVie, Avita Medical, Beiersdorf, Biorez, Eli Lily, EPI Health, Evolus, Galderma, Hugel America, Johnson and Johnson, L’Oreal USA, MedScape, Pfizer, Scientis US, UCB, Vichy Laboratories. She is a consultant for Arcutis Biothermapeutics, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Dior, and Sanofi. She has done contracted research for Allergan Aesthetics, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Croma-Pharma, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer, and has an ownership interest in Armis Scientific, GloGetter, and Piction Health.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

CHICAGO – at the inaugural Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

Among the first factors physicians should consider before recommending sunscreen are a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type, risks for burning or tanning, underlying skin disorders, and medications the patient is taking, Dr. Taylor, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! If patients are on hypertensives, for example, medications can make them more photosensitive.

Consider skin type

Dr. Taylor said she was dismayed by the results of a recent study, which found that 43% of dermatologists who responded to a survey reported that they never, rarely, or only sometimes took a patient’s skin type into account when making sunscreen recommendations. The article is referenced in a 2022 expert panel consensus paper she coauthored on photoprotection “for skin of all color.” But she pointed out that considering skin type alone is inadequate.

Questions for patients in joint decision-making should include lifestyle and work choices such as whether they work inside or outside, and how much sun exposure they get in a typical day. Heat and humidity levels should also be considered as should a patient’s susceptibility to dyspigmentation. “That could be overall darkening of the skin, mottled hyperpigmentation, actinic dyspigmentation, and, of course, propensity for skin cancer,” she said.

Use differs by race

Dr. Taylor, who is also vice chair for diversity, equity and inclusion in the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, pointed out that sunscreen use differs considerably by race.

In study of 8,952 adults in the United States who reported that they were sun sensitive found that a subset of adults with skin of color were significantly less likely to use sunscreen when compared with non-Hispanic White adults: Non-Hispanic Black (adjusted odds ratio, 0.43); non-Hispanic Asian (aOR. 0.54); and Hispanic (aOR, 0.70) adults.

In the study, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults were significantly less likely to use sunscreens with an SPF greater than 15. In addition, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic adults were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to wear long sleeves when outside. Such differences are important to keep in mind when advising patients about sunscreens, she said.

Protection for lighter-colored skin

Dr. Taylor said that, for patients with lighter skin tones, “we really want to protect against ultraviolet B as well as ultraviolet A, particularly ultraviolet A2. Ultraviolet radiation is going to cause DNA damage.” Patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I, II, or III are most susceptible to the effects of UVB with sunburn inflammation, which will cause erythema and tanning, and immunosuppression.

“For those who are I, II, and III, we do want to recommend a broad-spectrum, photostable sunscreen with a critical wavelength of 370 nanometers, which is going to protect from both UVB and UVA2,” she said.

Sunscreen recommendations are meant to be paired with advice to avoid midday sun from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., wearing protective clothing and accessories, and seeking shade, she noted.

Dr. Taylor said, for those patients with lighter skin who are more susceptible to photodamage and premature aging, physicians should recommend sunscreens that contain DNA repair enzymes such as photolyases and sunscreens that contain antioxidants that can prevent or reverse DNA damage. “The exogenous form of these lyases have been manufactured and added to sunscreens,” Dr. Taylor said. “They’re readily available in the United States. That is something to consider for patients with significant photodamage.”

Retinoids can also help alleviate or reverse photodamage, she added.

Protection for darker-colored skin

“Many people of color do not believe they need sunscreen,” Dr. Taylor said. But studies show that, although there may be more intrinsic protection, sunscreen is still needed.

Over 30 years ago, Halder and colleagues reported that melanin in skin of color can filter two to five times more UV radiation, and in a paper on the photoprotective role of melanin, Kaidbey and colleagues found that skin types V and VI had an intrinsic SPF of 13 when compared with those who have lighter complexions, which had an SPF of 3.

Sunburns seem to occur less frequently in people with skin of color, but that may be because erythema is less apparent in people with darker skin tones or because of differences in personal definitions of sunburn, Dr. Taylor said.

“Skin of color can and does sustain sunburns and sunscreen will help prevent that,” she said, adding that a recommendation of an SPF 30 is likely sufficient for these patients. Dr. Taylor noted that sunscreens for patients with darker skin often cost substantially more than those for lighter skin, and that should be considered in recommendations.

Tinted sunscreens

Dr. Taylor said that, while broad-spectrum photostable sunscreens protect against UVB and UVA 2, they don’t protect from visible light and UVA1. Two methods to add that protection are using inorganic tinted sunscreens that contain iron oxide or pigmentary titanium dioxide. Dr. Taylor was a coauthor of a practical guide to tinted sunscreens published in 2022.

“For iron oxide, we want a concentration of 3% or greater,” she said, adding that the percentage often is not known because if it is contained in a sunscreen, it is listed as an inactive ingredient.

Another method to address visible light and UVA1 is the use of antioxidant-containing sunscreens with vitamin E, vitamin C, or licochalcone A, Dr. Taylor said.

During the question-and-answer period following her presentation, Amit Pandya, MD, adjunct professor of dermatology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, asked why “every makeup, every sunscreen, just says iron oxide,” since it is known that visible light will cause pigmentation, especially in those with darker skin tones.

He urged pushing for a law that would require listing the percentage of iron oxide on products to assure it is sufficient, according to what the literature recommends.

Conference Chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of the Vitiligo and Pigmentation Institute of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that she recommends tinted sunscreens almost exclusively for her patients, but those with darker skin colors struggle to match color.

Dr. Taylor referred to an analysis published in 2022 of 58 over-the counter sunscreens, which found that only 38% of tinted sunscreens was available in more than one shade, “which is a problem for many of our patients.” She said that providing samples with different hues and tactile sensations may help patients find the right product.

Dr. Taylor disclosed being on the advisory boards for AbbVie, Avita Medical, Beiersdorf, Biorez, Eli Lily, EPI Health, Evolus, Galderma, Hugel America, Johnson and Johnson, L’Oreal USA, MedScape, Pfizer, Scientis US, UCB, Vichy Laboratories. She is a consultant for Arcutis Biothermapeutics, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Dior, and Sanofi. She has done contracted research for Allergan Aesthetics, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Croma-Pharma, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer, and has an ownership interest in Armis Scientific, GloGetter, and Piction Health.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

CHICAGO – at the inaugural Pigmentary Disorders Exchange Symposium.

Among the first factors physicians should consider before recommending sunscreen are a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type, risks for burning or tanning, underlying skin disorders, and medications the patient is taking, Dr. Taylor, professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said at the meeting, provided by MedscapeLIVE! If patients are on hypertensives, for example, medications can make them more photosensitive.

Consider skin type

Dr. Taylor said she was dismayed by the results of a recent study, which found that 43% of dermatologists who responded to a survey reported that they never, rarely, or only sometimes took a patient’s skin type into account when making sunscreen recommendations. The article is referenced in a 2022 expert panel consensus paper she coauthored on photoprotection “for skin of all color.” But she pointed out that considering skin type alone is inadequate.

Questions for patients in joint decision-making should include lifestyle and work choices such as whether they work inside or outside, and how much sun exposure they get in a typical day. Heat and humidity levels should also be considered as should a patient’s susceptibility to dyspigmentation. “That could be overall darkening of the skin, mottled hyperpigmentation, actinic dyspigmentation, and, of course, propensity for skin cancer,” she said.

Use differs by race

Dr. Taylor, who is also vice chair for diversity, equity and inclusion in the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, pointed out that sunscreen use differs considerably by race.

In study of 8,952 adults in the United States who reported that they were sun sensitive found that a subset of adults with skin of color were significantly less likely to use sunscreen when compared with non-Hispanic White adults: Non-Hispanic Black (adjusted odds ratio, 0.43); non-Hispanic Asian (aOR. 0.54); and Hispanic (aOR, 0.70) adults.

In the study, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults were significantly less likely to use sunscreens with an SPF greater than 15. In addition, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic adults were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to wear long sleeves when outside. Such differences are important to keep in mind when advising patients about sunscreens, she said.

Protection for lighter-colored skin

Dr. Taylor said that, for patients with lighter skin tones, “we really want to protect against ultraviolet B as well as ultraviolet A, particularly ultraviolet A2. Ultraviolet radiation is going to cause DNA damage.” Patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I, II, or III are most susceptible to the effects of UVB with sunburn inflammation, which will cause erythema and tanning, and immunosuppression.

“For those who are I, II, and III, we do want to recommend a broad-spectrum, photostable sunscreen with a critical wavelength of 370 nanometers, which is going to protect from both UVB and UVA2,” she said.

Sunscreen recommendations are meant to be paired with advice to avoid midday sun from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., wearing protective clothing and accessories, and seeking shade, she noted.

Dr. Taylor said, for those patients with lighter skin who are more susceptible to photodamage and premature aging, physicians should recommend sunscreens that contain DNA repair enzymes such as photolyases and sunscreens that contain antioxidants that can prevent or reverse DNA damage. “The exogenous form of these lyases have been manufactured and added to sunscreens,” Dr. Taylor said. “They’re readily available in the United States. That is something to consider for patients with significant photodamage.”

Retinoids can also help alleviate or reverse photodamage, she added.

Protection for darker-colored skin

“Many people of color do not believe they need sunscreen,” Dr. Taylor said. But studies show that, although there may be more intrinsic protection, sunscreen is still needed.

Over 30 years ago, Halder and colleagues reported that melanin in skin of color can filter two to five times more UV radiation, and in a paper on the photoprotective role of melanin, Kaidbey and colleagues found that skin types V and VI had an intrinsic SPF of 13 when compared with those who have lighter complexions, which had an SPF of 3.

Sunburns seem to occur less frequently in people with skin of color, but that may be because erythema is less apparent in people with darker skin tones or because of differences in personal definitions of sunburn, Dr. Taylor said.

“Skin of color can and does sustain sunburns and sunscreen will help prevent that,” she said, adding that a recommendation of an SPF 30 is likely sufficient for these patients. Dr. Taylor noted that sunscreens for patients with darker skin often cost substantially more than those for lighter skin, and that should be considered in recommendations.

Tinted sunscreens

Dr. Taylor said that, while broad-spectrum photostable sunscreens protect against UVB and UVA 2, they don’t protect from visible light and UVA1. Two methods to add that protection are using inorganic tinted sunscreens that contain iron oxide or pigmentary titanium dioxide. Dr. Taylor was a coauthor of a practical guide to tinted sunscreens published in 2022.

“For iron oxide, we want a concentration of 3% or greater,” she said, adding that the percentage often is not known because if it is contained in a sunscreen, it is listed as an inactive ingredient.

Another method to address visible light and UVA1 is the use of antioxidant-containing sunscreens with vitamin E, vitamin C, or licochalcone A, Dr. Taylor said.

During the question-and-answer period following her presentation, Amit Pandya, MD, adjunct professor of dermatology at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, asked why “every makeup, every sunscreen, just says iron oxide,” since it is known that visible light will cause pigmentation, especially in those with darker skin tones.

He urged pushing for a law that would require listing the percentage of iron oxide on products to assure it is sufficient, according to what the literature recommends.

Conference Chair Pearl Grimes, MD, director of the Vitiligo and Pigmentation Institute of Southern California, Los Angeles, said that she recommends tinted sunscreens almost exclusively for her patients, but those with darker skin colors struggle to match color.

Dr. Taylor referred to an analysis published in 2022 of 58 over-the counter sunscreens, which found that only 38% of tinted sunscreens was available in more than one shade, “which is a problem for many of our patients.” She said that providing samples with different hues and tactile sensations may help patients find the right product.

Dr. Taylor disclosed being on the advisory boards for AbbVie, Avita Medical, Beiersdorf, Biorez, Eli Lily, EPI Health, Evolus, Galderma, Hugel America, Johnson and Johnson, L’Oreal USA, MedScape, Pfizer, Scientis US, UCB, Vichy Laboratories. She is a consultant for Arcutis Biothermapeutics, Beiersdorf, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cara Therapeutics, Dior, and Sanofi. She has done contracted research for Allergan Aesthetics, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Croma-Pharma, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer, and has an ownership interest in Armis Scientific, GloGetter, and Piction Health.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

AT THE MEDSCAPELIVE! PIGMENTARY DISORDERS SYMPOSIUM

Encouraging telitacicept results reported in phase 3 for lupus, phase 2 for Sjögren’s

MILAN – Results of a phase 3 trial with the investigational drug telitacicept show that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus have a significantly greater rate of response to SLE response criteria, compared with placebo, while results from a phase 2 trial of the drug in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) also show significant improvements versus placebo.

“With only a limited number of treatments available for patients with lupus, this additional option is certainly an advance and the trial shows a strong efficacy result,” said Ronald van Vollenhoven, MD, PhD, who was not an investigator for either trial but presented the results for both at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology. He is professor of clinical immunology and rheumatology at Amsterdam University Medical Center and VU University Medical Center, also in Amsterdam.

Telitacicept is a recombinant fusion protein that targets B-lymphocyte stimulator and a proliferating-inducing ligand. It is currently undergoing testing in another phase 3 trial (REMESLE-1) at sites in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The current SLE results relate to the phase 3 study conducted in China, Dr. van Vollenhoven clarified.

SLE trial

The double-blind, placebo-controlled trial included 335 patients with SLE who had an average age of 35 years, a body mass index of 22-23 kg/m2, and a mean SELENA-SLEDAI (Safety of Estrogens in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment–Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) score of at least 11.5, indicating high disease activity. Most patients were on glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to weekly subcutaneous injections of telitacicept (160 mg; n = 167) or placebo (n = 168) in combination with standard therapy for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was the SLE Responder Index-4 (SRI4) response rate at week 52, while key secondary endpoints included SELENA-SLEDAI, physician global assessment, and levels of immunologic biomarkers including C3, C4, IgM, IgG, IgA, and CD19+ B cells. Safety was also assessed.

At week 52, Dr. van Vollenhoven reported that significantly more patients taking telitacicept achieved a SRI4 response, compared with placebo, at 67.1% versus 32.7%, respectively (P < .001). “The difference was seen at 4-8 weeks and stabilized at around 20 weeks,” he said.

Time to first SLE flare was also reduced in patients on the trial drug at a median of 198 days (95% confidence interval, 169-254 days), compared with placebo at 115 days (95% CI, 92-140 days).

“The secondary outcomes also supported efficacy in these patients,” Dr. van Vollenhoven added, noting that there was a rapid and sustained increase of C3 and C4, the latter being significantly greater than placebo, and reduction of IgM, IgG, IgA, and CD19+ B cells observed following telitacicept treatment.

A significantly higher proportion of patients in the telitacicept group showed improvement in SELENA-SLEDAI at week 52, defined as a 4-point or greater reduction, compared with placebo (70.1% vs. 40.5%).

Telitacicept did not increase the risk of infections. Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 84.5% with telitacicept versus 91.6% with placebo, with infections (mostly upper respiratory) seen in 65.3% and 60.1%, respectively.

Sjögren’s trial

The second trial was a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, 24-week study in 42 patients with pSS. Patients (18-65 years) received telitacicept at 160 mg or 240 mg subcutaneously once a week, or placebo, for a total of 24 doses. Patients had a EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) score of 5 points or more, and were anti-SSA antibody positive.

“Compared with placebo, telitacicept treatment resulted in significant improvement in ESSDAI and MFI-20 [20-item Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory],” Dr. van Vollenhoven reported, adding that, “there was a trend for improvement in salivary gland function and lacrimal gland function relative to placebo, as well as a favorable safety profile.”

ESSDAI change from baseline was 0.5, –3.8, and –2.3 in placebo, 160-mg, and 240-mg telitacicept doses, respectively. MFI-20 change from baseline was 7.0, –4.0, and –5.1, respectively. Dr. Van Vollenhoven said the difference between the doses was not statistically significant.

“If these results are confirmed, it could be the first time a biologic is proven efficacious in this disease,” Dr. Van Vollenhoven said in an interview. “It’s encouraging to know that a new treatment is showing promise in this phase 2 trial. A phase 3 trial is warranted.”

Studies yield promising but confusing results

In an interview, Roy Fleischmann, MD, who was not involved with either study, wondered whether the results of the SLE study could be race specific given the magnitude of response to the drug and that the trial was conducted only in China, and whether the positive results of the small Sjögren’s study will pan out in a larger trial.

“The SLE study was very interesting, but the problem is that it’s a Chinese drug in Chinese patients with Chinese doctors, so they are very dramatic results,” he said, questioning whether “these results are race specific,” and that “we will find out when they do the multinational study, but we haven’t seen this type of separation before [in response]. It’s interesting.

“The Sjögren’s was a positive study, but it was confusing because the low dose seemed to be better than the higher dose, and there were very few patients,” said Dr. Fleischmann, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and codirector of the Metroplex Clinical Research Center, both in Dallas. The left and right eyes gave different results, which was strange, and the salivary gland test was the same [mixed results], so what can we conclude? All in all, it was a small study with a suggestion of efficacy, but we have to do the phase 3 and see what it shows.”

Both trials were sponsored by RemeGen. Dr. van Vollenhoven reported serving as a paid adviser to AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, RemeGen, and UCB. He has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and UCB and educational support from AstraZeneca, Galapagos, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB. Dr. Fleischmann said he had has no relevant financial relationships.

MILAN – Results of a phase 3 trial with the investigational drug telitacicept show that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus have a significantly greater rate of response to SLE response criteria, compared with placebo, while results from a phase 2 trial of the drug in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) also show significant improvements versus placebo.

“With only a limited number of treatments available for patients with lupus, this additional option is certainly an advance and the trial shows a strong efficacy result,” said Ronald van Vollenhoven, MD, PhD, who was not an investigator for either trial but presented the results for both at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology. He is professor of clinical immunology and rheumatology at Amsterdam University Medical Center and VU University Medical Center, also in Amsterdam.

Telitacicept is a recombinant fusion protein that targets B-lymphocyte stimulator and a proliferating-inducing ligand. It is currently undergoing testing in another phase 3 trial (REMESLE-1) at sites in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The current SLE results relate to the phase 3 study conducted in China, Dr. van Vollenhoven clarified.

SLE trial

The double-blind, placebo-controlled trial included 335 patients with SLE who had an average age of 35 years, a body mass index of 22-23 kg/m2, and a mean SELENA-SLEDAI (Safety of Estrogens in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment–Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) score of at least 11.5, indicating high disease activity. Most patients were on glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to weekly subcutaneous injections of telitacicept (160 mg; n = 167) or placebo (n = 168) in combination with standard therapy for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was the SLE Responder Index-4 (SRI4) response rate at week 52, while key secondary endpoints included SELENA-SLEDAI, physician global assessment, and levels of immunologic biomarkers including C3, C4, IgM, IgG, IgA, and CD19+ B cells. Safety was also assessed.

At week 52, Dr. van Vollenhoven reported that significantly more patients taking telitacicept achieved a SRI4 response, compared with placebo, at 67.1% versus 32.7%, respectively (P < .001). “The difference was seen at 4-8 weeks and stabilized at around 20 weeks,” he said.

Time to first SLE flare was also reduced in patients on the trial drug at a median of 198 days (95% confidence interval, 169-254 days), compared with placebo at 115 days (95% CI, 92-140 days).

“The secondary outcomes also supported efficacy in these patients,” Dr. van Vollenhoven added, noting that there was a rapid and sustained increase of C3 and C4, the latter being significantly greater than placebo, and reduction of IgM, IgG, IgA, and CD19+ B cells observed following telitacicept treatment.

A significantly higher proportion of patients in the telitacicept group showed improvement in SELENA-SLEDAI at week 52, defined as a 4-point or greater reduction, compared with placebo (70.1% vs. 40.5%).

Telitacicept did not increase the risk of infections. Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 84.5% with telitacicept versus 91.6% with placebo, with infections (mostly upper respiratory) seen in 65.3% and 60.1%, respectively.

Sjögren’s trial

The second trial was a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, 24-week study in 42 patients with pSS. Patients (18-65 years) received telitacicept at 160 mg or 240 mg subcutaneously once a week, or placebo, for a total of 24 doses. Patients had a EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) score of 5 points or more, and were anti-SSA antibody positive.

“Compared with placebo, telitacicept treatment resulted in significant improvement in ESSDAI and MFI-20 [20-item Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory],” Dr. van Vollenhoven reported, adding that, “there was a trend for improvement in salivary gland function and lacrimal gland function relative to placebo, as well as a favorable safety profile.”

ESSDAI change from baseline was 0.5, –3.8, and –2.3 in placebo, 160-mg, and 240-mg telitacicept doses, respectively. MFI-20 change from baseline was 7.0, –4.0, and –5.1, respectively. Dr. Van Vollenhoven said the difference between the doses was not statistically significant.

“If these results are confirmed, it could be the first time a biologic is proven efficacious in this disease,” Dr. Van Vollenhoven said in an interview. “It’s encouraging to know that a new treatment is showing promise in this phase 2 trial. A phase 3 trial is warranted.”

Studies yield promising but confusing results

In an interview, Roy Fleischmann, MD, who was not involved with either study, wondered whether the results of the SLE study could be race specific given the magnitude of response to the drug and that the trial was conducted only in China, and whether the positive results of the small Sjögren’s study will pan out in a larger trial.

“The SLE study was very interesting, but the problem is that it’s a Chinese drug in Chinese patients with Chinese doctors, so they are very dramatic results,” he said, questioning whether “these results are race specific,” and that “we will find out when they do the multinational study, but we haven’t seen this type of separation before [in response]. It’s interesting.

“The Sjögren’s was a positive study, but it was confusing because the low dose seemed to be better than the higher dose, and there were very few patients,” said Dr. Fleischmann, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and codirector of the Metroplex Clinical Research Center, both in Dallas. The left and right eyes gave different results, which was strange, and the salivary gland test was the same [mixed results], so what can we conclude? All in all, it was a small study with a suggestion of efficacy, but we have to do the phase 3 and see what it shows.”

Both trials were sponsored by RemeGen. Dr. van Vollenhoven reported serving as a paid adviser to AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, RemeGen, and UCB. He has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and UCB and educational support from AstraZeneca, Galapagos, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB. Dr. Fleischmann said he had has no relevant financial relationships.

MILAN – Results of a phase 3 trial with the investigational drug telitacicept show that patients with systemic lupus erythematosus have a significantly greater rate of response to SLE response criteria, compared with placebo, while results from a phase 2 trial of the drug in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) also show significant improvements versus placebo.

“With only a limited number of treatments available for patients with lupus, this additional option is certainly an advance and the trial shows a strong efficacy result,” said Ronald van Vollenhoven, MD, PhD, who was not an investigator for either trial but presented the results for both at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology. He is professor of clinical immunology and rheumatology at Amsterdam University Medical Center and VU University Medical Center, also in Amsterdam.

Telitacicept is a recombinant fusion protein that targets B-lymphocyte stimulator and a proliferating-inducing ligand. It is currently undergoing testing in another phase 3 trial (REMESLE-1) at sites in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The current SLE results relate to the phase 3 study conducted in China, Dr. van Vollenhoven clarified.

SLE trial

The double-blind, placebo-controlled trial included 335 patients with SLE who had an average age of 35 years, a body mass index of 22-23 kg/m2, and a mean SELENA-SLEDAI (Safety of Estrogens in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment–Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) score of at least 11.5, indicating high disease activity. Most patients were on glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants.

Patients were randomized 1:1 to weekly subcutaneous injections of telitacicept (160 mg; n = 167) or placebo (n = 168) in combination with standard therapy for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was the SLE Responder Index-4 (SRI4) response rate at week 52, while key secondary endpoints included SELENA-SLEDAI, physician global assessment, and levels of immunologic biomarkers including C3, C4, IgM, IgG, IgA, and CD19+ B cells. Safety was also assessed.

At week 52, Dr. van Vollenhoven reported that significantly more patients taking telitacicept achieved a SRI4 response, compared with placebo, at 67.1% versus 32.7%, respectively (P < .001). “The difference was seen at 4-8 weeks and stabilized at around 20 weeks,” he said.

Time to first SLE flare was also reduced in patients on the trial drug at a median of 198 days (95% confidence interval, 169-254 days), compared with placebo at 115 days (95% CI, 92-140 days).

“The secondary outcomes also supported efficacy in these patients,” Dr. van Vollenhoven added, noting that there was a rapid and sustained increase of C3 and C4, the latter being significantly greater than placebo, and reduction of IgM, IgG, IgA, and CD19+ B cells observed following telitacicept treatment.

A significantly higher proportion of patients in the telitacicept group showed improvement in SELENA-SLEDAI at week 52, defined as a 4-point or greater reduction, compared with placebo (70.1% vs. 40.5%).

Telitacicept did not increase the risk of infections. Treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 84.5% with telitacicept versus 91.6% with placebo, with infections (mostly upper respiratory) seen in 65.3% and 60.1%, respectively.

Sjögren’s trial

The second trial was a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, 24-week study in 42 patients with pSS. Patients (18-65 years) received telitacicept at 160 mg or 240 mg subcutaneously once a week, or placebo, for a total of 24 doses. Patients had a EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index (ESSDAI) score of 5 points or more, and were anti-SSA antibody positive.

“Compared with placebo, telitacicept treatment resulted in significant improvement in ESSDAI and MFI-20 [20-item Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory],” Dr. van Vollenhoven reported, adding that, “there was a trend for improvement in salivary gland function and lacrimal gland function relative to placebo, as well as a favorable safety profile.”

ESSDAI change from baseline was 0.5, –3.8, and –2.3 in placebo, 160-mg, and 240-mg telitacicept doses, respectively. MFI-20 change from baseline was 7.0, –4.0, and –5.1, respectively. Dr. Van Vollenhoven said the difference between the doses was not statistically significant.

“If these results are confirmed, it could be the first time a biologic is proven efficacious in this disease,” Dr. Van Vollenhoven said in an interview. “It’s encouraging to know that a new treatment is showing promise in this phase 2 trial. A phase 3 trial is warranted.”

Studies yield promising but confusing results

In an interview, Roy Fleischmann, MD, who was not involved with either study, wondered whether the results of the SLE study could be race specific given the magnitude of response to the drug and that the trial was conducted only in China, and whether the positive results of the small Sjögren’s study will pan out in a larger trial.

“The SLE study was very interesting, but the problem is that it’s a Chinese drug in Chinese patients with Chinese doctors, so they are very dramatic results,” he said, questioning whether “these results are race specific,” and that “we will find out when they do the multinational study, but we haven’t seen this type of separation before [in response]. It’s interesting.

“The Sjögren’s was a positive study, but it was confusing because the low dose seemed to be better than the higher dose, and there were very few patients,” said Dr. Fleischmann, clinical professor of medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and codirector of the Metroplex Clinical Research Center, both in Dallas. The left and right eyes gave different results, which was strange, and the salivary gland test was the same [mixed results], so what can we conclude? All in all, it was a small study with a suggestion of efficacy, but we have to do the phase 3 and see what it shows.”

Both trials were sponsored by RemeGen. Dr. van Vollenhoven reported serving as a paid adviser to AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Pfizer, RemeGen, and UCB. He has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and UCB and educational support from AstraZeneca, Galapagos, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB. Dr. Fleischmann said he had has no relevant financial relationships.

AT EULAR 2023

Scientists discover variants, therapy for disabling pansclerotic morphea

A team of especially in patients who have not responded to other interventions.

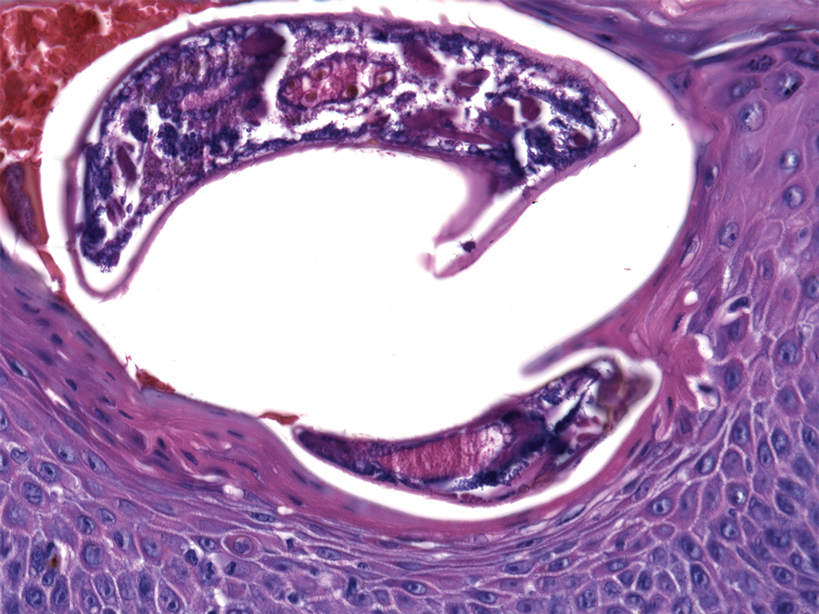

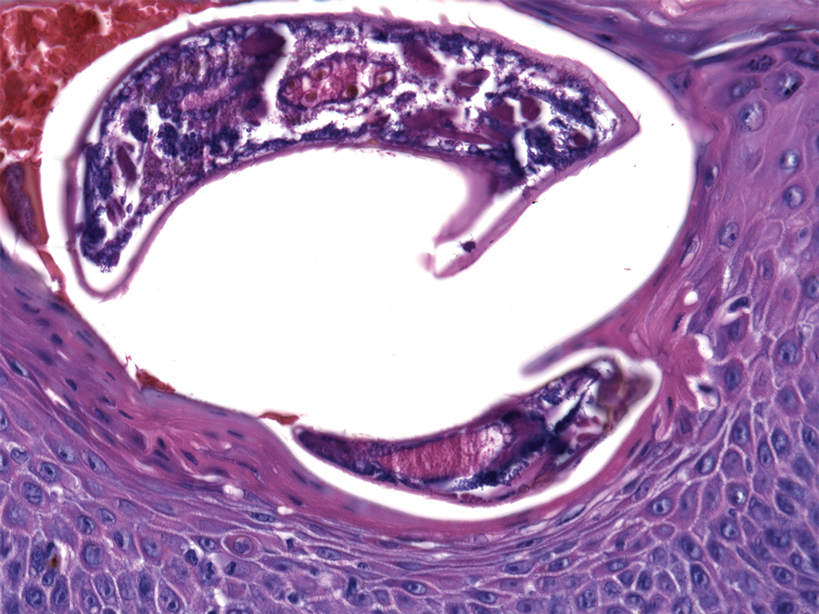

DPM was first reported in 1923, and while a genetic cause has been suspected, it had not been identified until now. The disease is the most severe form of deep morphea, which affects individuals with juvenile localized scleroderma. Patients, generally children under age 14, experience rapid sclerosis of all layers of the skin, fascia, muscle, and bone. DPM is also deadly: Most patients do not live more than 10 years after diagnosis, as they contract squamous cell carcinoma, restrictive pulmonary disease, sepsis, and gangrene.

In the study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers discovered that people with DPM have an overactive version of the protein STAT4, which regulates inflammation and wound healing. The scientists studied four patients from three unrelated families with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance of DPM.

“Researchers previously thought that this disorder was caused by the immune system attacking the skin,” Sarah Blackstone, a predoctoral fellow in the inflammatory disease section at the National Human Genome Research Institute and co–first author of the study, said in a statement from the National Institutes of Health describing the results. “However, we found that this is an oversimplification, and that both skin and the immune system play an active role in disabling pansclerotic morphea,” added Ms. Blackstone, also a medical student at the University of South Dakota, Sioux Falls.

The overactive STAT4 protein creates a positive feedback loop of inflammation and impaired wound-healing. By targeting JAK, the researchers were able to stop the feedback and patients’ wounds dramatically improved. After 18 months of treatment with oral ruxolitinib, one patient had discontinued all other medications, and had complete resolution of a chest rash, substantial clearing on the arms and legs, and global clinical improvement.

The authors said that oral systemic JAK inhibitor therapy is preferred over topical therapy. Their research also suggested that anti–interleukin-6 monoclonal antibodies – such as tocilizumab, approved for indications that include rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease, “may be an alternative therapy or may be useful in combination with JAK inhibitors in patients with DPM,” the authors wrote.

Most current DPM therapies – including methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and ultraviolet A light therapy – have been ineffective, and some have severe side effects.

“The findings of this study open doors for JAK inhibitors to be a potential treatment for other inflammatory skin disorders or disorders related to tissue scarring, whether it is scarring of the lungs, liver or bone marrow,” Dan Kastner, MD, PhD, an NIH distinguished investigator, head of the NHGRI’s inflammatory disease section, and a senior author of the paper, said in the NIH statement.

“We hope to continue studying other molecules in this pathway and how they are altered in patients with disabling pansclerotic morphea and related conditions to find clues to understanding a broader array of more common diseases,” Lori Broderick, MD, PhD, a senior author of the paper and an associate professor at University of California, San Diego, said in the statement.

The study was led by researchers at NHGRI in collaboration with researchers from UCSD and the University of Pittsburgh. Researchers from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases also participated.

The study was supported by grants from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Foundation; the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research; the University of California, San Diego, department of pediatrics; and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Additional support and grants were given by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, various institutes at the NIH, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the Hydrocephalus Association, the Scleroderma Research Foundation, the Biowulf High-Performance Computing Cluster of the Center for Information Technology, the Undiagnosed Diseases Program of the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the NIH, and the NIH Clinical Center.

A team of especially in patients who have not responded to other interventions.

DPM was first reported in 1923, and while a genetic cause has been suspected, it had not been identified until now. The disease is the most severe form of deep morphea, which affects individuals with juvenile localized scleroderma. Patients, generally children under age 14, experience rapid sclerosis of all layers of the skin, fascia, muscle, and bone. DPM is also deadly: Most patients do not live more than 10 years after diagnosis, as they contract squamous cell carcinoma, restrictive pulmonary disease, sepsis, and gangrene.

In the study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers discovered that people with DPM have an overactive version of the protein STAT4, which regulates inflammation and wound healing. The scientists studied four patients from three unrelated families with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance of DPM.

“Researchers previously thought that this disorder was caused by the immune system attacking the skin,” Sarah Blackstone, a predoctoral fellow in the inflammatory disease section at the National Human Genome Research Institute and co–first author of the study, said in a statement from the National Institutes of Health describing the results. “However, we found that this is an oversimplification, and that both skin and the immune system play an active role in disabling pansclerotic morphea,” added Ms. Blackstone, also a medical student at the University of South Dakota, Sioux Falls.

The overactive STAT4 protein creates a positive feedback loop of inflammation and impaired wound-healing. By targeting JAK, the researchers were able to stop the feedback and patients’ wounds dramatically improved. After 18 months of treatment with oral ruxolitinib, one patient had discontinued all other medications, and had complete resolution of a chest rash, substantial clearing on the arms and legs, and global clinical improvement.

The authors said that oral systemic JAK inhibitor therapy is preferred over topical therapy. Their research also suggested that anti–interleukin-6 monoclonal antibodies – such as tocilizumab, approved for indications that include rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease, “may be an alternative therapy or may be useful in combination with JAK inhibitors in patients with DPM,” the authors wrote.

Most current DPM therapies – including methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and ultraviolet A light therapy – have been ineffective, and some have severe side effects.

“The findings of this study open doors for JAK inhibitors to be a potential treatment for other inflammatory skin disorders or disorders related to tissue scarring, whether it is scarring of the lungs, liver or bone marrow,” Dan Kastner, MD, PhD, an NIH distinguished investigator, head of the NHGRI’s inflammatory disease section, and a senior author of the paper, said in the NIH statement.

“We hope to continue studying other molecules in this pathway and how they are altered in patients with disabling pansclerotic morphea and related conditions to find clues to understanding a broader array of more common diseases,” Lori Broderick, MD, PhD, a senior author of the paper and an associate professor at University of California, San Diego, said in the statement.

The study was led by researchers at NHGRI in collaboration with researchers from UCSD and the University of Pittsburgh. Researchers from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases also participated.

The study was supported by grants from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Foundation; the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research; the University of California, San Diego, department of pediatrics; and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Additional support and grants were given by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, various institutes at the NIH, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the Hydrocephalus Association, the Scleroderma Research Foundation, the Biowulf High-Performance Computing Cluster of the Center for Information Technology, the Undiagnosed Diseases Program of the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the NIH, and the NIH Clinical Center.

A team of especially in patients who have not responded to other interventions.

DPM was first reported in 1923, and while a genetic cause has been suspected, it had not been identified until now. The disease is the most severe form of deep morphea, which affects individuals with juvenile localized scleroderma. Patients, generally children under age 14, experience rapid sclerosis of all layers of the skin, fascia, muscle, and bone. DPM is also deadly: Most patients do not live more than 10 years after diagnosis, as they contract squamous cell carcinoma, restrictive pulmonary disease, sepsis, and gangrene.

In the study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers discovered that people with DPM have an overactive version of the protein STAT4, which regulates inflammation and wound healing. The scientists studied four patients from three unrelated families with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance of DPM.

“Researchers previously thought that this disorder was caused by the immune system attacking the skin,” Sarah Blackstone, a predoctoral fellow in the inflammatory disease section at the National Human Genome Research Institute and co–first author of the study, said in a statement from the National Institutes of Health describing the results. “However, we found that this is an oversimplification, and that both skin and the immune system play an active role in disabling pansclerotic morphea,” added Ms. Blackstone, also a medical student at the University of South Dakota, Sioux Falls.

The overactive STAT4 protein creates a positive feedback loop of inflammation and impaired wound-healing. By targeting JAK, the researchers were able to stop the feedback and patients’ wounds dramatically improved. After 18 months of treatment with oral ruxolitinib, one patient had discontinued all other medications, and had complete resolution of a chest rash, substantial clearing on the arms and legs, and global clinical improvement.

The authors said that oral systemic JAK inhibitor therapy is preferred over topical therapy. Their research also suggested that anti–interleukin-6 monoclonal antibodies – such as tocilizumab, approved for indications that include rheumatoid arthritis and systemic sclerosis–associated interstitial lung disease, “may be an alternative therapy or may be useful in combination with JAK inhibitors in patients with DPM,” the authors wrote.

Most current DPM therapies – including methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and ultraviolet A light therapy – have been ineffective, and some have severe side effects.

“The findings of this study open doors for JAK inhibitors to be a potential treatment for other inflammatory skin disorders or disorders related to tissue scarring, whether it is scarring of the lungs, liver or bone marrow,” Dan Kastner, MD, PhD, an NIH distinguished investigator, head of the NHGRI’s inflammatory disease section, and a senior author of the paper, said in the NIH statement.

“We hope to continue studying other molecules in this pathway and how they are altered in patients with disabling pansclerotic morphea and related conditions to find clues to understanding a broader array of more common diseases,” Lori Broderick, MD, PhD, a senior author of the paper and an associate professor at University of California, San Diego, said in the statement.

The study was led by researchers at NHGRI in collaboration with researchers from UCSD and the University of Pittsburgh. Researchers from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases also participated.

The study was supported by grants from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Foundation; the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research; the University of California, San Diego, department of pediatrics; and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Additional support and grants were given by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, various institutes at the NIH, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the Hydrocephalus Association, the Scleroderma Research Foundation, the Biowulf High-Performance Computing Cluster of the Center for Information Technology, the Undiagnosed Diseases Program of the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the NIH, and the NIH Clinical Center.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Enthesitis, arthritis, tenosynovitis linked to dupilumab use for atopic dermatitis

Around 5% of patients treated with dupilumab (Dupixent) for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis experience musculoskeletal (MSK) symptoms, according to the results of a descriptive study.

The main MSK symptom seen in the observational cohort was enthesitis, but some patients also experienced arthritis and tenosynovitis a median of 17 weeks after starting dupilumab treatment. Together these symptoms represent a new MSK syndrome, say researchers from the United Kingdom.

“The pattern of MSK symptoms and signs is characteristic of psoriatic arthritis/peripheral spondyloarthritis,” Bruce Kirkham, MD, and collaborators report in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“We started a few years ago and have been following the patients for quite a long time,” Dr. Kirkham, a consultant rheumatologist at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, told this news organization.

“We’re still seeing patients with the same type of syndrome presenting occasionally. It’s not a very common adverse event, but we think it continues,” he observed.

“Most of them don’t have very severe problems, and a lot of them can be treated with quite simple drugs or, alternatively, reducing the frequency of the injection,” Dr. Kirkham added.

Characterizing the MSK symptoms

Of 470 patients with atopic dermatitis who started treatment with dupilumab at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust between October 2018 and February 2021, 36 (7.65%) developed rheumatic symptoms and were referred to the rheumatology department. These individuals had their family history assessed and thorough MSK evaluations, which included antibody and inflammatory markers, ultrasound of the peripheral small joints, and MRI of the large joints and spine.

A total of 26 (5.5%) patients – 14 of whom were male – had inflammatory enthesitis, arthritis, and/or tenosynovitis. Of the others, seven had osteoarthritis and three had degenerative spine disease.

Enthesitis was the most common finding in those with rheumatic symptoms, occurring on its own in 11 patients, with arthritis in three patients, and tenosynovitis in two patients.

These symptoms appeared 2-48 weeks after starting dupilumab treatment and were categorized as mild in 16 (61%) cases, moderate in six cases, and severe in four cases.

No specific predictors of the MSK symptoms seen were noted. Patient age, sex, duration of their atopic dermatitis, or how their skin condition had been previously treated did not help identify those who might develop rheumatic problems.

Conservative management approach

All patients had “outstanding” responses to treatment, Dr. Kirkham noted: The mean Eczema Area and Severity Index score before dupilumab treatment was 21, falling to 4.2 with treatment, indicating a mean 80% improvement.

Co-author Joseph Nathan, MBChB, of London North West Healthcare NHS Trust, who collaborated on the research while working within Dr. Kirkham’s group, said separately: “The concern that patients have is that when they start a medication and develop a side effect is that the medication is going to be stopped.”

Clinicians treating the patients took a conservative approach, prescribing NSAIDs such as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors or altering the frequency with which dupilumab was given.

With this approach, MSK symptoms resolved in 15 patients who remained on treatment and in seven who had to stop dupilumab. There were four patients, however, who had unresolved symptoms even once dupilumab treatment had been stopped.

Altering the local cytokine balance

Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the alpha subunit of the interleukin-4 receptor. This results in blocking the function of not only IL-4 but also IL-13.

Dr. Kirkham and colleagues think this might not only alter the balance of cytokines in the skin but also in the joints and entheses with IL-17, IL-23, or even tumor necrosis factor playing a possible role. Another thought is that many circulating T-cells in the skin move to the joints and entheses to trigger symptoms.

IL-13 inhibition does seem to be important, as another British research team, from the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England), has found.

At the recent annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology, Sizheng Steven Zhao, MBChB, PhD, and colleagues reported that among people who carried a genetic variant predisposing them to having low IL-13 function, there was a higher risk for inflammatory diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and other spondyloarthropathy-related diseases.

Indeed, when the single nucleotide polymorphism rs20541 was present, the odds for having psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis were higher than when it was not.

The findings are consistent with the idea that IL-4 and IL-13 may be acting as a restraint towards MSK diseases in some patients, Dr. Zhao and co-authors suggest.

“The genetic data supports what [Dr. Kirkham and team] have said from a mechanistic point of view,” Dr. Zhao said in an interview. “What you’re observing has a genetic basis.”

Dermatology perspective

Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017, dupilumab has since been hailed as a “breakthrough” in atopic dermatitis treatment. Given as a subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks, it provides a much-needed option for people who have moderate-to-severe disease and have tried other available treatments, including corticosteroids.

Dupilumab has since also been approved for asthma, chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and prurigo nodularis and is used off-label for other skin conditions such as contact dermatitis, chronic spontaneous urticaria, and alopecia areata.

“Dupilumab, like a lot of medications for atopic dermatitis, is a relatively new drug, and we are still learning about its safety,” Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Inflammatory arthritis has been reported in patients treated with dupilumab, and this new study provides some useful estimates,” added Dr. Gelfand, who is a professor of dermatology and epidemiology and directs the Psoriasis and Phototherapy Treatment Center, Philadelphia.

“There was no control group,” Dr. Gelfand said, so “a causal relationship cannot be well established based on these data alone. The mechanism is not known but may result from a shifting of the immune system.”

Dr. Zhao observed: “We don’t know what the natural history of these adverse events is. We don’t know if stopping the drug early will prevent long-term adverse events. So, we don’t know if people will ultimately develop permanent psoriatic arthritis if we don’t intervene quick enough when we observe an adverse event.”

Being aware of the possibility of rheumatic side effects occurring with dupilumab and similar agents is key, Dr. Gelfand and Dr. Kirkham both said independently.

“I have personally seen this entity in my practice,” Dr. Gelfand said. “It is important to clinicians prescribing dupilumab to alert patients about this potential side effect and ask about joint symptoms in follow-up.”

Dr. Kirkham said: “Prescribers need to be aware of it, because up until now it’s been just very vaguely discussed as sort of aches and pains, arthralgias, and it’s a much more specific of a kind of syndrome of enthesitis, arthritis, tenosynovitis – a little like psoriatic arthritis.”

Not everyone has come across these side effects, however, as Steven Daveluy, MD, associate professor and dermatology program director at Wayne State University, Detroit, said in an interview.

“This article and the other case series both noted the musculoskeletal symptoms occurred in about 5% of patients, which surprised me since I haven’t seen it in my practice and have enough patients being treated with dupilumab that I would expect to see a case at that rate,” Dr. Daveluy said.

“The majority of cases are mild and respond to treatment with anti-inflammatories like naproxen, which is available over the counter. It’s likely that patients with a mild case could simply treat their pain with naproxen that’s already in their medicine cabinet until it resolves, never bringing it to the doctor’s attention,” he suggested.

“Dupilumab is still a safe and effective medication that can change the lives of patients suffering from atopic dermatitis,” he said.

“Awareness of this potential side effect can help dermatologists recognize it early and work together with patients to determine the best course of action.”

All research mentioned in this article was independently supported. Dr. Kirkham, Mr. Nathan, Dr. Zhao, and Dr. Daveluy report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Gelfand has served as a consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies and receives research grants from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer. He is a co-patent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Around 5% of patients treated with dupilumab (Dupixent) for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis experience musculoskeletal (MSK) symptoms, according to the results of a descriptive study.

The main MSK symptom seen in the observational cohort was enthesitis, but some patients also experienced arthritis and tenosynovitis a median of 17 weeks after starting dupilumab treatment. Together these symptoms represent a new MSK syndrome, say researchers from the United Kingdom.

“The pattern of MSK symptoms and signs is characteristic of psoriatic arthritis/peripheral spondyloarthritis,” Bruce Kirkham, MD, and collaborators report in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“We started a few years ago and have been following the patients for quite a long time,” Dr. Kirkham, a consultant rheumatologist at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, told this news organization.

“We’re still seeing patients with the same type of syndrome presenting occasionally. It’s not a very common adverse event, but we think it continues,” he observed.

“Most of them don’t have very severe problems, and a lot of them can be treated with quite simple drugs or, alternatively, reducing the frequency of the injection,” Dr. Kirkham added.

Characterizing the MSK symptoms

Of 470 patients with atopic dermatitis who started treatment with dupilumab at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust between October 2018 and February 2021, 36 (7.65%) developed rheumatic symptoms and were referred to the rheumatology department. These individuals had their family history assessed and thorough MSK evaluations, which included antibody and inflammatory markers, ultrasound of the peripheral small joints, and MRI of the large joints and spine.

A total of 26 (5.5%) patients – 14 of whom were male – had inflammatory enthesitis, arthritis, and/or tenosynovitis. Of the others, seven had osteoarthritis and three had degenerative spine disease.

Enthesitis was the most common finding in those with rheumatic symptoms, occurring on its own in 11 patients, with arthritis in three patients, and tenosynovitis in two patients.

These symptoms appeared 2-48 weeks after starting dupilumab treatment and were categorized as mild in 16 (61%) cases, moderate in six cases, and severe in four cases.

No specific predictors of the MSK symptoms seen were noted. Patient age, sex, duration of their atopic dermatitis, or how their skin condition had been previously treated did not help identify those who might develop rheumatic problems.

Conservative management approach

All patients had “outstanding” responses to treatment, Dr. Kirkham noted: The mean Eczema Area and Severity Index score before dupilumab treatment was 21, falling to 4.2 with treatment, indicating a mean 80% improvement.

Co-author Joseph Nathan, MBChB, of London North West Healthcare NHS Trust, who collaborated on the research while working within Dr. Kirkham’s group, said separately: “The concern that patients have is that when they start a medication and develop a side effect is that the medication is going to be stopped.”

Clinicians treating the patients took a conservative approach, prescribing NSAIDs such as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors or altering the frequency with which dupilumab was given.

With this approach, MSK symptoms resolved in 15 patients who remained on treatment and in seven who had to stop dupilumab. There were four patients, however, who had unresolved symptoms even once dupilumab treatment had been stopped.

Altering the local cytokine balance

Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the alpha subunit of the interleukin-4 receptor. This results in blocking the function of not only IL-4 but also IL-13.

Dr. Kirkham and colleagues think this might not only alter the balance of cytokines in the skin but also in the joints and entheses with IL-17, IL-23, or even tumor necrosis factor playing a possible role. Another thought is that many circulating T-cells in the skin move to the joints and entheses to trigger symptoms.

IL-13 inhibition does seem to be important, as another British research team, from the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England), has found.

At the recent annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology, Sizheng Steven Zhao, MBChB, PhD, and colleagues reported that among people who carried a genetic variant predisposing them to having low IL-13 function, there was a higher risk for inflammatory diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and other spondyloarthropathy-related diseases.

Indeed, when the single nucleotide polymorphism rs20541 was present, the odds for having psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis were higher than when it was not.

The findings are consistent with the idea that IL-4 and IL-13 may be acting as a restraint towards MSK diseases in some patients, Dr. Zhao and co-authors suggest.

“The genetic data supports what [Dr. Kirkham and team] have said from a mechanistic point of view,” Dr. Zhao said in an interview. “What you’re observing has a genetic basis.”

Dermatology perspective

Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2017, dupilumab has since been hailed as a “breakthrough” in atopic dermatitis treatment. Given as a subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks, it provides a much-needed option for people who have moderate-to-severe disease and have tried other available treatments, including corticosteroids.

Dupilumab has since also been approved for asthma, chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis, eosinophilic esophagitis, and prurigo nodularis and is used off-label for other skin conditions such as contact dermatitis, chronic spontaneous urticaria, and alopecia areata.

“Dupilumab, like a lot of medications for atopic dermatitis, is a relatively new drug, and we are still learning about its safety,” Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Inflammatory arthritis has been reported in patients treated with dupilumab, and this new study provides some useful estimates,” added Dr. Gelfand, who is a professor of dermatology and epidemiology and directs the Psoriasis and Phototherapy Treatment Center, Philadelphia.

“There was no control group,” Dr. Gelfand said, so “a causal relationship cannot be well established based on these data alone. The mechanism is not known but may result from a shifting of the immune system.”

Dr. Zhao observed: “We don’t know what the natural history of these adverse events is. We don’t know if stopping the drug early will prevent long-term adverse events. So, we don’t know if people will ultimately develop permanent psoriatic arthritis if we don’t intervene quick enough when we observe an adverse event.”

Being aware of the possibility of rheumatic side effects occurring with dupilumab and similar agents is key, Dr. Gelfand and Dr. Kirkham both said independently.

“I have personally seen this entity in my practice,” Dr. Gelfand said. “It is important to clinicians prescribing dupilumab to alert patients about this potential side effect and ask about joint symptoms in follow-up.”

Dr. Kirkham said: “Prescribers need to be aware of it, because up until now it’s been just very vaguely discussed as sort of aches and pains, arthralgias, and it’s a much more specific of a kind of syndrome of enthesitis, arthritis, tenosynovitis – a little like psoriatic arthritis.”

Not everyone has come across these side effects, however, as Steven Daveluy, MD, associate professor and dermatology program director at Wayne State University, Detroit, said in an interview.

“This article and the other case series both noted the musculoskeletal symptoms occurred in about 5% of patients, which surprised me since I haven’t seen it in my practice and have enough patients being treated with dupilumab that I would expect to see a case at that rate,” Dr. Daveluy said.

“The majority of cases are mild and respond to treatment with anti-inflammatories like naproxen, which is available over the counter. It’s likely that patients with a mild case could simply treat their pain with naproxen that’s already in their medicine cabinet until it resolves, never bringing it to the doctor’s attention,” he suggested.

“Dupilumab is still a safe and effective medication that can change the lives of patients suffering from atopic dermatitis,” he said.

“Awareness of this potential side effect can help dermatologists recognize it early and work together with patients to determine the best course of action.”

All research mentioned in this article was independently supported. Dr. Kirkham, Mr. Nathan, Dr. Zhao, and Dr. Daveluy report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Gelfand has served as a consultant for numerous pharmaceutical companies and receives research grants from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer. He is a co-patent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Around 5% of patients treated with dupilumab (Dupixent) for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis experience musculoskeletal (MSK) symptoms, according to the results of a descriptive study.

The main MSK symptom seen in the observational cohort was enthesitis, but some patients also experienced arthritis and tenosynovitis a median of 17 weeks after starting dupilumab treatment. Together these symptoms represent a new MSK syndrome, say researchers from the United Kingdom.

“The pattern of MSK symptoms and signs is characteristic of psoriatic arthritis/peripheral spondyloarthritis,” Bruce Kirkham, MD, and collaborators report in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

“We started a few years ago and have been following the patients for quite a long time,” Dr. Kirkham, a consultant rheumatologist at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, told this news organization.

“We’re still seeing patients with the same type of syndrome presenting occasionally. It’s not a very common adverse event, but we think it continues,” he observed.

“Most of them don’t have very severe problems, and a lot of them can be treated with quite simple drugs or, alternatively, reducing the frequency of the injection,” Dr. Kirkham added.

Characterizing the MSK symptoms

Of 470 patients with atopic dermatitis who started treatment with dupilumab at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust between October 2018 and February 2021, 36 (7.65%) developed rheumatic symptoms and were referred to the rheumatology department. These individuals had their family history assessed and thorough MSK evaluations, which included antibody and inflammatory markers, ultrasound of the peripheral small joints, and MRI of the large joints and spine.

A total of 26 (5.5%) patients – 14 of whom were male – had inflammatory enthesitis, arthritis, and/or tenosynovitis. Of the others, seven had osteoarthritis and three had degenerative spine disease.

Enthesitis was the most common finding in those with rheumatic symptoms, occurring on its own in 11 patients, with arthritis in three patients, and tenosynovitis in two patients.

These symptoms appeared 2-48 weeks after starting dupilumab treatment and were categorized as mild in 16 (61%) cases, moderate in six cases, and severe in four cases.

No specific predictors of the MSK symptoms seen were noted. Patient age, sex, duration of their atopic dermatitis, or how their skin condition had been previously treated did not help identify those who might develop rheumatic problems.

Conservative management approach

All patients had “outstanding” responses to treatment, Dr. Kirkham noted: The mean Eczema Area and Severity Index score before dupilumab treatment was 21, falling to 4.2 with treatment, indicating a mean 80% improvement.

Co-author Joseph Nathan, MBChB, of London North West Healthcare NHS Trust, who collaborated on the research while working within Dr. Kirkham’s group, said separately: “The concern that patients have is that when they start a medication and develop a side effect is that the medication is going to be stopped.”

Clinicians treating the patients took a conservative approach, prescribing NSAIDs such as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors or altering the frequency with which dupilumab was given.

With this approach, MSK symptoms resolved in 15 patients who remained on treatment and in seven who had to stop dupilumab. There were four patients, however, who had unresolved symptoms even once dupilumab treatment had been stopped.

Altering the local cytokine balance

Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the alpha subunit of the interleukin-4 receptor. This results in blocking the function of not only IL-4 but also IL-13.

Dr. Kirkham and colleagues think this might not only alter the balance of cytokines in the skin but also in the joints and entheses with IL-17, IL-23, or even tumor necrosis factor playing a possible role. Another thought is that many circulating T-cells in the skin move to the joints and entheses to trigger symptoms.

IL-13 inhibition does seem to be important, as another British research team, from the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis at the University of Manchester (England), has found.

At the recent annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology, Sizheng Steven Zhao, MBChB, PhD, and colleagues reported that among people who carried a genetic variant predisposing them to having low IL-13 function, there was a higher risk for inflammatory diseases such as psoriatic arthritis and other spondyloarthropathy-related diseases.

Indeed, when the single nucleotide polymorphism rs20541 was present, the odds for having psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis were higher than when it was not.

The findings are consistent with the idea that IL-4 and IL-13 may be acting as a restraint towards MSK diseases in some patients, Dr. Zhao and co-authors suggest.