User login

Children and COVID: Hospitalizations provide a tale of two sources

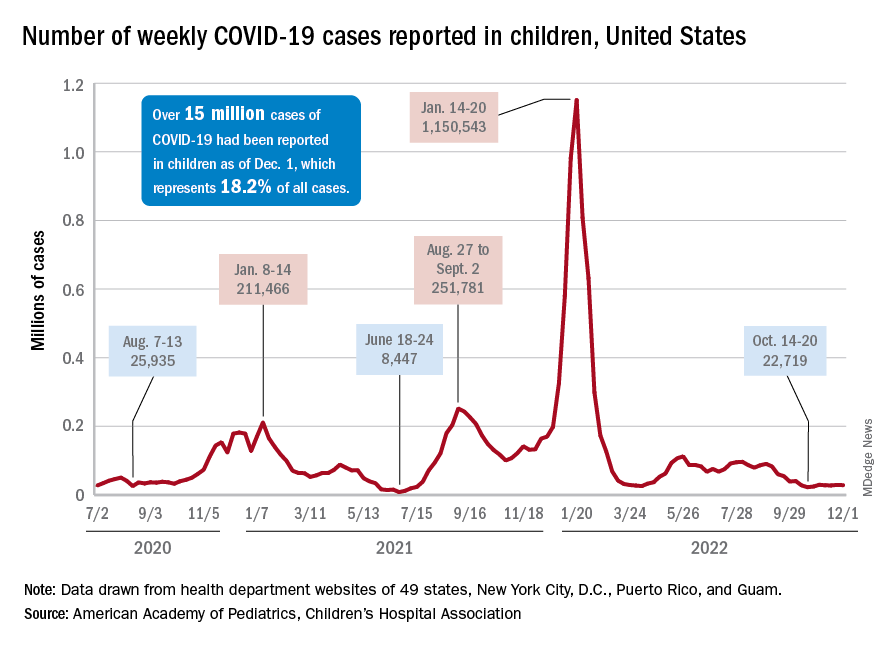

New cases of COVID-19 in children largely held steady over the Thanksgiving holiday, but hospital admissions are telling a somewhat different story.

New pediatric COVID cases for the week ending on Thanksgiving (11/18-11/24) were up by 5.3% over the previous week, but in the most recent week (11/25-12/1) new cases dropped by 2.6%, according to state data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

In both weeks, though, the total case count stayed below 30,000 – a streak that has now lasted 8 weeks – so the actual number of weekly cases remained fairly low, the AAP/CHA weekly report indicates.

The nation’s emergency departments also experienced a small Thanksgiving bump, as the proportion of visits with diagnosed COVID went from 1.0% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years on Nov. 14 to 2.0% on Nov. 27, just 3 days after the official holiday, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The rate was down to 1.5% on Dec. 1, and similar patterns can be seen for children aged 12-15 and 16-17 years.

New hospital admissions, on the other hand, seem to be following a different path, at least according to the CDC. The hospitalization rate for children aged 0-17 years bottomed out at 0.16 new admissions per 100,000 population back on Oct. 21 and has climbed fairly steadily since then. It was up to 0.20 per 100,000 by Nov. 14, had reached 0.22 per 100,000 on Thanksgiving day (11/24), and then continued to 0.26 per 100,000 by Dec. 2, the latest date for which CDC data are available.

The hospitalization story, however, offers yet another twist. The New York Times, using data from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, reports that new COVID-related admissions have held steady at 1.0 per 100,000 since Nov. 18. The rate is much higher than has been reported by the CDC, but no increase can be seen in recent weeks among children, which is not the case for Americans overall, Medscape recently reported.

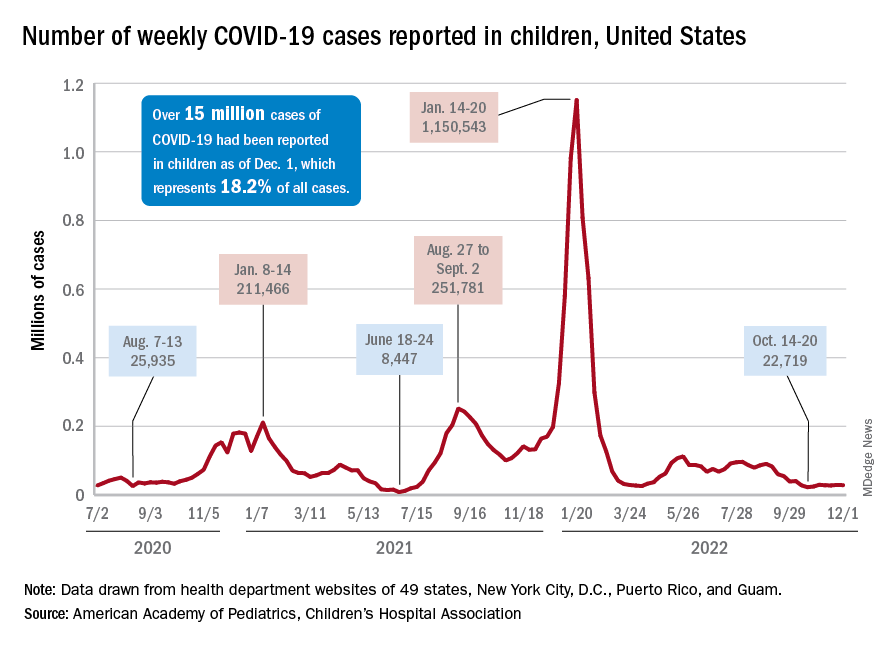

New cases of COVID-19 in children largely held steady over the Thanksgiving holiday, but hospital admissions are telling a somewhat different story.

New pediatric COVID cases for the week ending on Thanksgiving (11/18-11/24) were up by 5.3% over the previous week, but in the most recent week (11/25-12/1) new cases dropped by 2.6%, according to state data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

In both weeks, though, the total case count stayed below 30,000 – a streak that has now lasted 8 weeks – so the actual number of weekly cases remained fairly low, the AAP/CHA weekly report indicates.

The nation’s emergency departments also experienced a small Thanksgiving bump, as the proportion of visits with diagnosed COVID went from 1.0% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years on Nov. 14 to 2.0% on Nov. 27, just 3 days after the official holiday, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The rate was down to 1.5% on Dec. 1, and similar patterns can be seen for children aged 12-15 and 16-17 years.

New hospital admissions, on the other hand, seem to be following a different path, at least according to the CDC. The hospitalization rate for children aged 0-17 years bottomed out at 0.16 new admissions per 100,000 population back on Oct. 21 and has climbed fairly steadily since then. It was up to 0.20 per 100,000 by Nov. 14, had reached 0.22 per 100,000 on Thanksgiving day (11/24), and then continued to 0.26 per 100,000 by Dec. 2, the latest date for which CDC data are available.

The hospitalization story, however, offers yet another twist. The New York Times, using data from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, reports that new COVID-related admissions have held steady at 1.0 per 100,000 since Nov. 18. The rate is much higher than has been reported by the CDC, but no increase can be seen in recent weeks among children, which is not the case for Americans overall, Medscape recently reported.

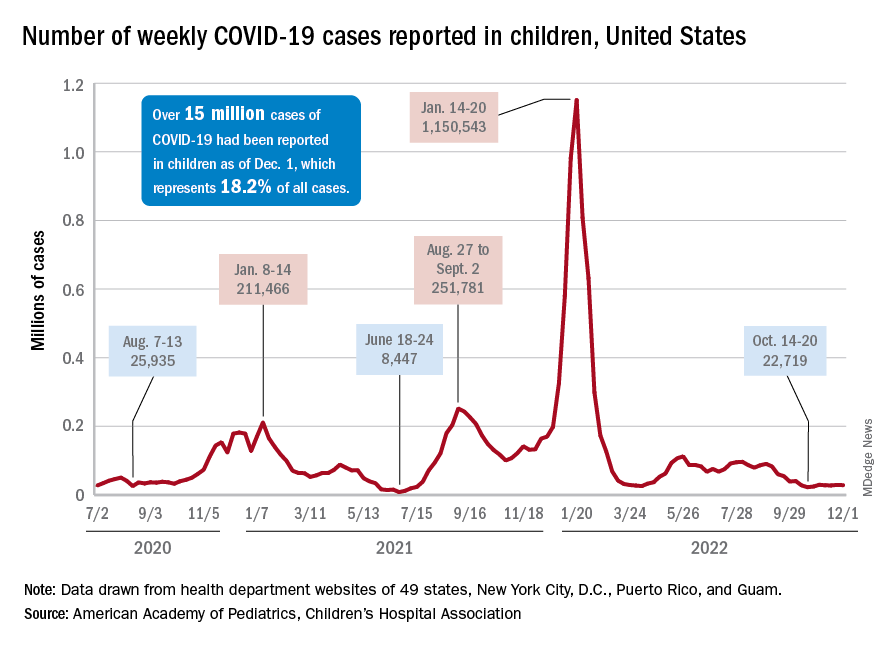

New cases of COVID-19 in children largely held steady over the Thanksgiving holiday, but hospital admissions are telling a somewhat different story.

New pediatric COVID cases for the week ending on Thanksgiving (11/18-11/24) were up by 5.3% over the previous week, but in the most recent week (11/25-12/1) new cases dropped by 2.6%, according to state data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

In both weeks, though, the total case count stayed below 30,000 – a streak that has now lasted 8 weeks – so the actual number of weekly cases remained fairly low, the AAP/CHA weekly report indicates.

The nation’s emergency departments also experienced a small Thanksgiving bump, as the proportion of visits with diagnosed COVID went from 1.0% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years on Nov. 14 to 2.0% on Nov. 27, just 3 days after the official holiday, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The rate was down to 1.5% on Dec. 1, and similar patterns can be seen for children aged 12-15 and 16-17 years.

New hospital admissions, on the other hand, seem to be following a different path, at least according to the CDC. The hospitalization rate for children aged 0-17 years bottomed out at 0.16 new admissions per 100,000 population back on Oct. 21 and has climbed fairly steadily since then. It was up to 0.20 per 100,000 by Nov. 14, had reached 0.22 per 100,000 on Thanksgiving day (11/24), and then continued to 0.26 per 100,000 by Dec. 2, the latest date for which CDC data are available.

The hospitalization story, however, offers yet another twist. The New York Times, using data from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, reports that new COVID-related admissions have held steady at 1.0 per 100,000 since Nov. 18. The rate is much higher than has been reported by the CDC, but no increase can be seen in recent weeks among children, which is not the case for Americans overall, Medscape recently reported.

Diagnosed too late

It had only been 3 weeks since I first met this patient. She presented with an advanced case of colon cancer, but instead of treatment,

Within the course of 2 weeks I saw another new patient, but this time with pancreatic cancer that metastasized to the liver. “When can we start treatment?” he asked. Like my female patient with colon cancer, he was diagnosed too late as he was already in an incurable stage. He was shocked to learn that his condition was in stage 4, that achieving remission would be difficult and a cure, not likely. Certainly, standard of care treatments and clinical trials offered him hope, but they were unlikely to change the outcome.

We take a course in this – that is, in giving bad news, but every doctor has his or her own approach. Some are so uncomfortable with the talk, they choose avoidance and adopt the “look like you gotta go approach.” Or, the doctor may schedule another treatment or another test with the intention of avoiding end-of-life discussions. Other doctors opt for straight talk: “I think you should get your affairs in order. You’ve got 3 months to live.” These are extreme behaviors I wouldn’t recommend.

In my practice, I sit with my patients and explain the diagnosis. After discussing all options and the advanced stage and diagnosis, it ultimately comes down to “Win or lose, I will be here to take care of you.” Sometimes there is therapy that may help, but either way, the patient understands that death is a real possibility.

I find that people just want to know if there is hope. A different treatment regimen or a clinical trial may (or may not) extend their life. And while we cannot predict outcomes, we can give them hope. You can’t shut down hope. True for some people the cup is always half empty, but most people want to live and are optimistic no matter how small the chances are.

These conversations are very difficult. I don’t like them, but then I don’t avoid them either. Fortunately, patients don’t usually come to my office for the first visit presenting with advanced disease. In the cases I described above, one patient had been experiencing unexplained weight loss, but didn’t share it with a physician. And, for the patient with pancreatic cancer, other than some discomfort in the last couple of weeks, the disease was not associated with other symptoms. But the absence of symptoms should not in any way rule out a malignant disease. A diagnosis should be based on a complete evaluation of signs and symptoms followed by testing.

We’ve got to be able to take the time to listen to our patients during these encounters. We may not spend as much time as we should because we’re so busy now and we’re slaves to EMRs. It helps if we take more time to probe symptoms a little longer, especially in the primary care setting.

It is possible for a patient with cancer to be asymptomatic up until the later stages of the disease. A study published in ESMO Open in 2020 found that fewer than half of patients with stage 4 non–small cell lung cancer have only one or two symptoms at diagnosis regardless of whether the patient was a smoker. In this study only 33% of patients reported having a cough and 25% had chest pain.

A study presented in October at the United European Gastroenterology Week found that of 600 pancreatic cancer cases, 46 of these were not detected by CT or MRI conducted 3-18 months prior to diagnosis. Of the 46 cases, 26% were not picked up by the radiologist and the rest were largely as a result of imaging changes over time. Radiology techniques are good, but they cannot pick up lesions that are too small. And some lesions, particularly in pancreatic cancer, can grow and metastasize rather quickly.

When a patient is diagnosed with advanced disease, it is most often simply because of the nature of the disease. But sometimes patients put off scheduling a doctor visit because of fear of the potential for bad news or fear of the doctor belittling their symptoms. Some tell me they were “just hoping the symptoms would disappear.” Waiting too long to see a doctor is never a good idea because timing is crucial. In many cases, there is a small window of opportunity to treat disease if remission is to be achieved.

Dr. Henry is a practicing clinical oncologist with PennMedicine in Philadelphia where he also serves as Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine at Pennsylvania Hospital.

This article was updated 12/7/22.

It had only been 3 weeks since I first met this patient. She presented with an advanced case of colon cancer, but instead of treatment,

Within the course of 2 weeks I saw another new patient, but this time with pancreatic cancer that metastasized to the liver. “When can we start treatment?” he asked. Like my female patient with colon cancer, he was diagnosed too late as he was already in an incurable stage. He was shocked to learn that his condition was in stage 4, that achieving remission would be difficult and a cure, not likely. Certainly, standard of care treatments and clinical trials offered him hope, but they were unlikely to change the outcome.

We take a course in this – that is, in giving bad news, but every doctor has his or her own approach. Some are so uncomfortable with the talk, they choose avoidance and adopt the “look like you gotta go approach.” Or, the doctor may schedule another treatment or another test with the intention of avoiding end-of-life discussions. Other doctors opt for straight talk: “I think you should get your affairs in order. You’ve got 3 months to live.” These are extreme behaviors I wouldn’t recommend.

In my practice, I sit with my patients and explain the diagnosis. After discussing all options and the advanced stage and diagnosis, it ultimately comes down to “Win or lose, I will be here to take care of you.” Sometimes there is therapy that may help, but either way, the patient understands that death is a real possibility.

I find that people just want to know if there is hope. A different treatment regimen or a clinical trial may (or may not) extend their life. And while we cannot predict outcomes, we can give them hope. You can’t shut down hope. True for some people the cup is always half empty, but most people want to live and are optimistic no matter how small the chances are.

These conversations are very difficult. I don’t like them, but then I don’t avoid them either. Fortunately, patients don’t usually come to my office for the first visit presenting with advanced disease. In the cases I described above, one patient had been experiencing unexplained weight loss, but didn’t share it with a physician. And, for the patient with pancreatic cancer, other than some discomfort in the last couple of weeks, the disease was not associated with other symptoms. But the absence of symptoms should not in any way rule out a malignant disease. A diagnosis should be based on a complete evaluation of signs and symptoms followed by testing.

We’ve got to be able to take the time to listen to our patients during these encounters. We may not spend as much time as we should because we’re so busy now and we’re slaves to EMRs. It helps if we take more time to probe symptoms a little longer, especially in the primary care setting.

It is possible for a patient with cancer to be asymptomatic up until the later stages of the disease. A study published in ESMO Open in 2020 found that fewer than half of patients with stage 4 non–small cell lung cancer have only one or two symptoms at diagnosis regardless of whether the patient was a smoker. In this study only 33% of patients reported having a cough and 25% had chest pain.

A study presented in October at the United European Gastroenterology Week found that of 600 pancreatic cancer cases, 46 of these were not detected by CT or MRI conducted 3-18 months prior to diagnosis. Of the 46 cases, 26% were not picked up by the radiologist and the rest were largely as a result of imaging changes over time. Radiology techniques are good, but they cannot pick up lesions that are too small. And some lesions, particularly in pancreatic cancer, can grow and metastasize rather quickly.

When a patient is diagnosed with advanced disease, it is most often simply because of the nature of the disease. But sometimes patients put off scheduling a doctor visit because of fear of the potential for bad news or fear of the doctor belittling their symptoms. Some tell me they were “just hoping the symptoms would disappear.” Waiting too long to see a doctor is never a good idea because timing is crucial. In many cases, there is a small window of opportunity to treat disease if remission is to be achieved.

Dr. Henry is a practicing clinical oncologist with PennMedicine in Philadelphia where he also serves as Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine at Pennsylvania Hospital.

This article was updated 12/7/22.

It had only been 3 weeks since I first met this patient. She presented with an advanced case of colon cancer, but instead of treatment,

Within the course of 2 weeks I saw another new patient, but this time with pancreatic cancer that metastasized to the liver. “When can we start treatment?” he asked. Like my female patient with colon cancer, he was diagnosed too late as he was already in an incurable stage. He was shocked to learn that his condition was in stage 4, that achieving remission would be difficult and a cure, not likely. Certainly, standard of care treatments and clinical trials offered him hope, but they were unlikely to change the outcome.

We take a course in this – that is, in giving bad news, but every doctor has his or her own approach. Some are so uncomfortable with the talk, they choose avoidance and adopt the “look like you gotta go approach.” Or, the doctor may schedule another treatment or another test with the intention of avoiding end-of-life discussions. Other doctors opt for straight talk: “I think you should get your affairs in order. You’ve got 3 months to live.” These are extreme behaviors I wouldn’t recommend.

In my practice, I sit with my patients and explain the diagnosis. After discussing all options and the advanced stage and diagnosis, it ultimately comes down to “Win or lose, I will be here to take care of you.” Sometimes there is therapy that may help, but either way, the patient understands that death is a real possibility.

I find that people just want to know if there is hope. A different treatment regimen or a clinical trial may (or may not) extend their life. And while we cannot predict outcomes, we can give them hope. You can’t shut down hope. True for some people the cup is always half empty, but most people want to live and are optimistic no matter how small the chances are.

These conversations are very difficult. I don’t like them, but then I don’t avoid them either. Fortunately, patients don’t usually come to my office for the first visit presenting with advanced disease. In the cases I described above, one patient had been experiencing unexplained weight loss, but didn’t share it with a physician. And, for the patient with pancreatic cancer, other than some discomfort in the last couple of weeks, the disease was not associated with other symptoms. But the absence of symptoms should not in any way rule out a malignant disease. A diagnosis should be based on a complete evaluation of signs and symptoms followed by testing.

We’ve got to be able to take the time to listen to our patients during these encounters. We may not spend as much time as we should because we’re so busy now and we’re slaves to EMRs. It helps if we take more time to probe symptoms a little longer, especially in the primary care setting.

It is possible for a patient with cancer to be asymptomatic up until the later stages of the disease. A study published in ESMO Open in 2020 found that fewer than half of patients with stage 4 non–small cell lung cancer have only one or two symptoms at diagnosis regardless of whether the patient was a smoker. In this study only 33% of patients reported having a cough and 25% had chest pain.

A study presented in October at the United European Gastroenterology Week found that of 600 pancreatic cancer cases, 46 of these were not detected by CT or MRI conducted 3-18 months prior to diagnosis. Of the 46 cases, 26% were not picked up by the radiologist and the rest were largely as a result of imaging changes over time. Radiology techniques are good, but they cannot pick up lesions that are too small. And some lesions, particularly in pancreatic cancer, can grow and metastasize rather quickly.

When a patient is diagnosed with advanced disease, it is most often simply because of the nature of the disease. But sometimes patients put off scheduling a doctor visit because of fear of the potential for bad news or fear of the doctor belittling their symptoms. Some tell me they were “just hoping the symptoms would disappear.” Waiting too long to see a doctor is never a good idea because timing is crucial. In many cases, there is a small window of opportunity to treat disease if remission is to be achieved.

Dr. Henry is a practicing clinical oncologist with PennMedicine in Philadelphia where he also serves as Vice Chair of the Department of Medicine at Pennsylvania Hospital.

This article was updated 12/7/22.

‘Game changer’: Thyroid cancer recurrence no higher with lobectomy

Patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer and lymph node metastasis show no significant increase in tumor recurrence when undergoing lobectomy compared with a total thyroidectomy, new research shows.

“Results of this cohort study suggest that patients with ipsilateral clinical lateral neck metastasis (cN1b) papillary thyroid cancer who underwent lobectomy exhibited recurrence-free survival rates similar to those who underwent total thyroidectomy after controlling for major prognostic factors,” the authors conclude in the study published online in JAMA Surgery.

“These findings suggest that cN1b alone should not be an absolute indication for total thyroidectomy,” they note.

The study, involving the largest cohort to date to compare patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer treated with lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy, “challenged the current guidelines and pushed the boundary of limited surgical treatment even further,” say Michelle B. Mulder, MD, and Quan-Yang Duh, MD, of the department of surgery, University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

“It can be a game changer if confirmed by future prospective and multicenter studies,” they add.

Guidelines still recommend total thyroidectomy with subsequent RAI

While lower-intensity treatment options, with a lower risk of complications, have gained favor in the treatment of low-risk papillary thyroid cancer, guidelines still recommend the consideration of total thyroidectomy and subsequent radioactive iodine ablation (RAI) for intermediate-risk cancers because of the higher chance of recurrence, particularly among those with clinically positive nodes.

However, data on the superiority of a total thyroidectomy, with or without RAI, versus lobectomy is inconsistent, prompting first author Siyuan Xu, MD, of the department of head and neck surgical oncology, National Cancer Center, Beijing, and colleagues to compare the risk of recurrence with the two approaches.

For the study, patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer treated at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Hospital in Beijing between January 2000 and December 2017, who had a lobectomy or total thyroidectomy, were paired 1:1 in a propensity score matching analysis.

Other than treatment type, the 265 pairs of patients were matched based on all other potential prognostic factors, including age, sex, primary tumor size, minor extrathyroidal extension, multifocality, number of lymph node metastases, and lymph node ratio.

Participants were a mean age of 37 years and 66% were female.

With a median follow-up of 60 months in the lobectomy group and 58 months in the total thyroidectomy group, structural recurrences occurred in 7.9% (21) and 6.4% (17) of patients, respectively, which was not significantly different.

The primary endpoint, 5-year rate of recurrence-free survival, was also not significantly different between the lobectomy (92.3%) and total thyroidectomy groups (93.7%) (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.10; P = .77).

In a further stratified analysis of patients treated with total thyroidectomy along with RAI (n = 75), the lack of a significant difference in recurrence-free survival versus lobectomy remained (aHR, 0.59; P = .46).

The results were similar in unadjusted as well as adjusted analyses, and a power analysis indicated that the study had a 90% power to detect a more than 4.9% difference in recurrence-free survival.

“Given the lower complication rate of lobectomy, a maximal 4.9% recurrence-free survival difference is acceptable, which enhances the reliability of the study results,” the authors say.

They conclude that “our findings call into question whether cN1b alone [ipsilateral clinical lateral neck metastasis papillary thyroid cancer] should be an absolute determinant for deciding the optimal extent of thyroid surgery for papillary thyroid cancer.”

With total thyroidectomy, RAI can be given

An important argument in favor of total thyroidectomy is that with the complete resection of thyroid tissue, RAI ablation can then be used for postoperative detection of residual or metastatic disease, as well as for treatment, the authors note.

Indeed, a study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database showed RAI ablation is associated with a 29% reduction in the risk of death in patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer, with a hazard risk of 0.71.

However, conflicting data from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, suggests no significant benefit with total thyroidectomy and RAI ablation.

The current study’s analysis of patients treated with RAI, though limited in size, supports the latter study’s findings, the authors note.

“When we performed further stratified analyses in patients treated with total thyroidectomy plus RAI ablation and their counterparts, no significant difference was found, which conformed with [the] result from the whole cohort.”

“Certainly, the stratified comparison did not have enough power to examine the effect of RAI ablation on tumor recurrence subject to the limitation of sample size and case selection [and] further study is needed on this topic,” they write.

Some limitations warrant cautious interpretation

In their editorial, Dr. Mulder and Dr. Duh note that while some previous studies have shown similar outcomes relating to tumor size, thyroid hormone suppression therapy, and multifocality, “few have addressed lateral neck involvement.”

They suggest cautious interpretation, however, due to limitations, acknowledged by the authors, including the single-center nature of the study.

“Appropriate propensity matching may mitigate selection bias but cannot eliminate it entirely and their findings may not be replicated in other institutions by other surgeons,” they note.

Other limitations include that changes in clinical practice and patient selection were likely over the course of the study because of significant changes in American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines between 2009 and 2017, and characteristics including molecular genetic testing, which could have influenced final results, were not taken into consideration.

Furthermore, for patients with intermediate-risk cancer, modifications in postoperative follow-up are necessary following lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy; “the role of radioiodine is limited and the levels of thyroglobulin more complicated to interpret,” they note.

The study and editorial authors had no disclosures to report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer and lymph node metastasis show no significant increase in tumor recurrence when undergoing lobectomy compared with a total thyroidectomy, new research shows.

“Results of this cohort study suggest that patients with ipsilateral clinical lateral neck metastasis (cN1b) papillary thyroid cancer who underwent lobectomy exhibited recurrence-free survival rates similar to those who underwent total thyroidectomy after controlling for major prognostic factors,” the authors conclude in the study published online in JAMA Surgery.

“These findings suggest that cN1b alone should not be an absolute indication for total thyroidectomy,” they note.

The study, involving the largest cohort to date to compare patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer treated with lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy, “challenged the current guidelines and pushed the boundary of limited surgical treatment even further,” say Michelle B. Mulder, MD, and Quan-Yang Duh, MD, of the department of surgery, University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

“It can be a game changer if confirmed by future prospective and multicenter studies,” they add.

Guidelines still recommend total thyroidectomy with subsequent RAI

While lower-intensity treatment options, with a lower risk of complications, have gained favor in the treatment of low-risk papillary thyroid cancer, guidelines still recommend the consideration of total thyroidectomy and subsequent radioactive iodine ablation (RAI) for intermediate-risk cancers because of the higher chance of recurrence, particularly among those with clinically positive nodes.

However, data on the superiority of a total thyroidectomy, with or without RAI, versus lobectomy is inconsistent, prompting first author Siyuan Xu, MD, of the department of head and neck surgical oncology, National Cancer Center, Beijing, and colleagues to compare the risk of recurrence with the two approaches.

For the study, patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer treated at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Hospital in Beijing between January 2000 and December 2017, who had a lobectomy or total thyroidectomy, were paired 1:1 in a propensity score matching analysis.

Other than treatment type, the 265 pairs of patients were matched based on all other potential prognostic factors, including age, sex, primary tumor size, minor extrathyroidal extension, multifocality, number of lymph node metastases, and lymph node ratio.

Participants were a mean age of 37 years and 66% were female.

With a median follow-up of 60 months in the lobectomy group and 58 months in the total thyroidectomy group, structural recurrences occurred in 7.9% (21) and 6.4% (17) of patients, respectively, which was not significantly different.

The primary endpoint, 5-year rate of recurrence-free survival, was also not significantly different between the lobectomy (92.3%) and total thyroidectomy groups (93.7%) (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.10; P = .77).

In a further stratified analysis of patients treated with total thyroidectomy along with RAI (n = 75), the lack of a significant difference in recurrence-free survival versus lobectomy remained (aHR, 0.59; P = .46).

The results were similar in unadjusted as well as adjusted analyses, and a power analysis indicated that the study had a 90% power to detect a more than 4.9% difference in recurrence-free survival.

“Given the lower complication rate of lobectomy, a maximal 4.9% recurrence-free survival difference is acceptable, which enhances the reliability of the study results,” the authors say.

They conclude that “our findings call into question whether cN1b alone [ipsilateral clinical lateral neck metastasis papillary thyroid cancer] should be an absolute determinant for deciding the optimal extent of thyroid surgery for papillary thyroid cancer.”

With total thyroidectomy, RAI can be given

An important argument in favor of total thyroidectomy is that with the complete resection of thyroid tissue, RAI ablation can then be used for postoperative detection of residual or metastatic disease, as well as for treatment, the authors note.

Indeed, a study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database showed RAI ablation is associated with a 29% reduction in the risk of death in patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer, with a hazard risk of 0.71.

However, conflicting data from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, suggests no significant benefit with total thyroidectomy and RAI ablation.

The current study’s analysis of patients treated with RAI, though limited in size, supports the latter study’s findings, the authors note.

“When we performed further stratified analyses in patients treated with total thyroidectomy plus RAI ablation and their counterparts, no significant difference was found, which conformed with [the] result from the whole cohort.”

“Certainly, the stratified comparison did not have enough power to examine the effect of RAI ablation on tumor recurrence subject to the limitation of sample size and case selection [and] further study is needed on this topic,” they write.

Some limitations warrant cautious interpretation

In their editorial, Dr. Mulder and Dr. Duh note that while some previous studies have shown similar outcomes relating to tumor size, thyroid hormone suppression therapy, and multifocality, “few have addressed lateral neck involvement.”

They suggest cautious interpretation, however, due to limitations, acknowledged by the authors, including the single-center nature of the study.

“Appropriate propensity matching may mitigate selection bias but cannot eliminate it entirely and their findings may not be replicated in other institutions by other surgeons,” they note.

Other limitations include that changes in clinical practice and patient selection were likely over the course of the study because of significant changes in American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines between 2009 and 2017, and characteristics including molecular genetic testing, which could have influenced final results, were not taken into consideration.

Furthermore, for patients with intermediate-risk cancer, modifications in postoperative follow-up are necessary following lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy; “the role of radioiodine is limited and the levels of thyroglobulin more complicated to interpret,” they note.

The study and editorial authors had no disclosures to report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer and lymph node metastasis show no significant increase in tumor recurrence when undergoing lobectomy compared with a total thyroidectomy, new research shows.

“Results of this cohort study suggest that patients with ipsilateral clinical lateral neck metastasis (cN1b) papillary thyroid cancer who underwent lobectomy exhibited recurrence-free survival rates similar to those who underwent total thyroidectomy after controlling for major prognostic factors,” the authors conclude in the study published online in JAMA Surgery.

“These findings suggest that cN1b alone should not be an absolute indication for total thyroidectomy,” they note.

The study, involving the largest cohort to date to compare patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer treated with lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy, “challenged the current guidelines and pushed the boundary of limited surgical treatment even further,” say Michelle B. Mulder, MD, and Quan-Yang Duh, MD, of the department of surgery, University of California, San Francisco, in an accompanying editorial.

“It can be a game changer if confirmed by future prospective and multicenter studies,” they add.

Guidelines still recommend total thyroidectomy with subsequent RAI

While lower-intensity treatment options, with a lower risk of complications, have gained favor in the treatment of low-risk papillary thyroid cancer, guidelines still recommend the consideration of total thyroidectomy and subsequent radioactive iodine ablation (RAI) for intermediate-risk cancers because of the higher chance of recurrence, particularly among those with clinically positive nodes.

However, data on the superiority of a total thyroidectomy, with or without RAI, versus lobectomy is inconsistent, prompting first author Siyuan Xu, MD, of the department of head and neck surgical oncology, National Cancer Center, Beijing, and colleagues to compare the risk of recurrence with the two approaches.

For the study, patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer treated at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Cancer Hospital in Beijing between January 2000 and December 2017, who had a lobectomy or total thyroidectomy, were paired 1:1 in a propensity score matching analysis.

Other than treatment type, the 265 pairs of patients were matched based on all other potential prognostic factors, including age, sex, primary tumor size, minor extrathyroidal extension, multifocality, number of lymph node metastases, and lymph node ratio.

Participants were a mean age of 37 years and 66% were female.

With a median follow-up of 60 months in the lobectomy group and 58 months in the total thyroidectomy group, structural recurrences occurred in 7.9% (21) and 6.4% (17) of patients, respectively, which was not significantly different.

The primary endpoint, 5-year rate of recurrence-free survival, was also not significantly different between the lobectomy (92.3%) and total thyroidectomy groups (93.7%) (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.10; P = .77).

In a further stratified analysis of patients treated with total thyroidectomy along with RAI (n = 75), the lack of a significant difference in recurrence-free survival versus lobectomy remained (aHR, 0.59; P = .46).

The results were similar in unadjusted as well as adjusted analyses, and a power analysis indicated that the study had a 90% power to detect a more than 4.9% difference in recurrence-free survival.

“Given the lower complication rate of lobectomy, a maximal 4.9% recurrence-free survival difference is acceptable, which enhances the reliability of the study results,” the authors say.

They conclude that “our findings call into question whether cN1b alone [ipsilateral clinical lateral neck metastasis papillary thyroid cancer] should be an absolute determinant for deciding the optimal extent of thyroid surgery for papillary thyroid cancer.”

With total thyroidectomy, RAI can be given

An important argument in favor of total thyroidectomy is that with the complete resection of thyroid tissue, RAI ablation can then be used for postoperative detection of residual or metastatic disease, as well as for treatment, the authors note.

Indeed, a study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database showed RAI ablation is associated with a 29% reduction in the risk of death in patients with intermediate-risk papillary thyroid cancer, with a hazard risk of 0.71.

However, conflicting data from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, suggests no significant benefit with total thyroidectomy and RAI ablation.

The current study’s analysis of patients treated with RAI, though limited in size, supports the latter study’s findings, the authors note.

“When we performed further stratified analyses in patients treated with total thyroidectomy plus RAI ablation and their counterparts, no significant difference was found, which conformed with [the] result from the whole cohort.”

“Certainly, the stratified comparison did not have enough power to examine the effect of RAI ablation on tumor recurrence subject to the limitation of sample size and case selection [and] further study is needed on this topic,” they write.

Some limitations warrant cautious interpretation

In their editorial, Dr. Mulder and Dr. Duh note that while some previous studies have shown similar outcomes relating to tumor size, thyroid hormone suppression therapy, and multifocality, “few have addressed lateral neck involvement.”

They suggest cautious interpretation, however, due to limitations, acknowledged by the authors, including the single-center nature of the study.

“Appropriate propensity matching may mitigate selection bias but cannot eliminate it entirely and their findings may not be replicated in other institutions by other surgeons,” they note.

Other limitations include that changes in clinical practice and patient selection were likely over the course of the study because of significant changes in American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines between 2009 and 2017, and characteristics including molecular genetic testing, which could have influenced final results, were not taken into consideration.

Furthermore, for patients with intermediate-risk cancer, modifications in postoperative follow-up are necessary following lobectomy versus total thyroidectomy; “the role of radioiodine is limited and the levels of thyroglobulin more complicated to interpret,” they note.

The study and editorial authors had no disclosures to report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Youths have strong opinions on language about body weight

With youth obesity on the rise – an estimated 1 in 5 youths are impacted by obesity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – conversations about healthy weight are becoming more commonplace, not only in the pediatrician’s office, but at home, too. But the language we use around this sensitive topic is important, as youths are acutely aware that words have a direct impact on their mental health.

Sixteen-year-old Avery DiCocco of Northbrook, Ill., knows how vulnerable teenagers feel.

“I think it definitely matters the way that parents and doctors address weight,” she said. “You never know who may be insecure, and using negative words could go a lot further than they think with impacting self-esteem.”

A new study published in Pediatrics brings light to the words that parents (and providers) use when speaking to youths (ages 10-17) about their weight.

Researchers from the University of Connecticut Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health, Hartford, led an online survey of youths and their parents. Those who took part were asked about 27 terms related to body weight. Parents were asked to comment on their use of these words, while youths commented on the emotional response. The researchers said 1,936 parents and 2,032 adolescents were surveyed between September and December 2021.

Although results skewed toward the use of more positive words, such as “healthy weight,” over terms like “obese,” “fat” or “large,” there was variation across ethnicity, sexual orientation, and weight status. For example, it was noted in the study, funded by WW International, that preference for the word “curvy” was higher among Hispanic/Latino youths, sexual minority youths, and those with a body mass index in the 95th percentile, compared with their White, heterosexual, and lower-weight peers.

Words matter

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics came out with a policy statement on weight stigma and the need for doctors to use more neutral language and less stigmatizing terms in practice when discussing weight among youths.

But one of the reasons this new study is important, said Gregory Germain, MD, associate chief of pediatrics at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Children’s Hospital, is that this study focuses on parents who interact with their kids much more often than a pediatrician who sees them a few times a year.

“Parental motivation, discussion, interaction on a consistent basis – that dialogue is so critical in kids with obesity,” said Germain, who stresses that all adults, coaches, and educators should consider this study as well.

“When we think about those detrimental impacts on mental health when more stigmatizing language is used, just us being more mindful in how we are talking to youth can make such a profound impact,” said Rebecca Kamody, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Yale University, with a research and clinical focus on eating and weight disorders.

“In essence, this is a low-hanging fruit intervention,” she said.

Dr. Kamody recommends we take a lesson from “cultural humility” in psychology to understand how to approach this with kids, calling for “the humbleness as parents or providers in asking someone what they want used to make it the safest place for a discussion with our youth.”

One piece of the puzzle

Dr. Germain and Dr. Kamody agreed that language in discussing this topic is important but that we need to recognize that this topic in general is extremely tricky.

For one, “there are these very real metabolic complications of having high weight at a young age,” said Kamody, who stresses the need for balance to make real change.

Dr. Germain agreed. “Finding a fine line between discussing obesity and not kicking your kid into disordered eating is important.”

The researchers also recognize the limits of an online study, where self-reporting parents may not want to admit using negative weight terminology, but certainly believe it’s a start in identifying some of the undesirable patterns that may be occurring when it comes to weight.

“The overarching message is a positive one, that with our preteens and teenage kids, we need to watch our language, to create a nonjudgmental and safe environment to discuss weight and any issue involved with taking care of themselves,” said Dr. Germain.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With youth obesity on the rise – an estimated 1 in 5 youths are impacted by obesity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – conversations about healthy weight are becoming more commonplace, not only in the pediatrician’s office, but at home, too. But the language we use around this sensitive topic is important, as youths are acutely aware that words have a direct impact on their mental health.

Sixteen-year-old Avery DiCocco of Northbrook, Ill., knows how vulnerable teenagers feel.

“I think it definitely matters the way that parents and doctors address weight,” she said. “You never know who may be insecure, and using negative words could go a lot further than they think with impacting self-esteem.”

A new study published in Pediatrics brings light to the words that parents (and providers) use when speaking to youths (ages 10-17) about their weight.

Researchers from the University of Connecticut Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health, Hartford, led an online survey of youths and their parents. Those who took part were asked about 27 terms related to body weight. Parents were asked to comment on their use of these words, while youths commented on the emotional response. The researchers said 1,936 parents and 2,032 adolescents were surveyed between September and December 2021.

Although results skewed toward the use of more positive words, such as “healthy weight,” over terms like “obese,” “fat” or “large,” there was variation across ethnicity, sexual orientation, and weight status. For example, it was noted in the study, funded by WW International, that preference for the word “curvy” was higher among Hispanic/Latino youths, sexual minority youths, and those with a body mass index in the 95th percentile, compared with their White, heterosexual, and lower-weight peers.

Words matter

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics came out with a policy statement on weight stigma and the need for doctors to use more neutral language and less stigmatizing terms in practice when discussing weight among youths.

But one of the reasons this new study is important, said Gregory Germain, MD, associate chief of pediatrics at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Children’s Hospital, is that this study focuses on parents who interact with their kids much more often than a pediatrician who sees them a few times a year.

“Parental motivation, discussion, interaction on a consistent basis – that dialogue is so critical in kids with obesity,” said Germain, who stresses that all adults, coaches, and educators should consider this study as well.

“When we think about those detrimental impacts on mental health when more stigmatizing language is used, just us being more mindful in how we are talking to youth can make such a profound impact,” said Rebecca Kamody, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Yale University, with a research and clinical focus on eating and weight disorders.

“In essence, this is a low-hanging fruit intervention,” she said.

Dr. Kamody recommends we take a lesson from “cultural humility” in psychology to understand how to approach this with kids, calling for “the humbleness as parents or providers in asking someone what they want used to make it the safest place for a discussion with our youth.”

One piece of the puzzle

Dr. Germain and Dr. Kamody agreed that language in discussing this topic is important but that we need to recognize that this topic in general is extremely tricky.

For one, “there are these very real metabolic complications of having high weight at a young age,” said Kamody, who stresses the need for balance to make real change.

Dr. Germain agreed. “Finding a fine line between discussing obesity and not kicking your kid into disordered eating is important.”

The researchers also recognize the limits of an online study, where self-reporting parents may not want to admit using negative weight terminology, but certainly believe it’s a start in identifying some of the undesirable patterns that may be occurring when it comes to weight.

“The overarching message is a positive one, that with our preteens and teenage kids, we need to watch our language, to create a nonjudgmental and safe environment to discuss weight and any issue involved with taking care of themselves,” said Dr. Germain.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With youth obesity on the rise – an estimated 1 in 5 youths are impacted by obesity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – conversations about healthy weight are becoming more commonplace, not only in the pediatrician’s office, but at home, too. But the language we use around this sensitive topic is important, as youths are acutely aware that words have a direct impact on their mental health.

Sixteen-year-old Avery DiCocco of Northbrook, Ill., knows how vulnerable teenagers feel.

“I think it definitely matters the way that parents and doctors address weight,” she said. “You never know who may be insecure, and using negative words could go a lot further than they think with impacting self-esteem.”

A new study published in Pediatrics brings light to the words that parents (and providers) use when speaking to youths (ages 10-17) about their weight.

Researchers from the University of Connecticut Rudd Center for Food Policy & Health, Hartford, led an online survey of youths and their parents. Those who took part were asked about 27 terms related to body weight. Parents were asked to comment on their use of these words, while youths commented on the emotional response. The researchers said 1,936 parents and 2,032 adolescents were surveyed between September and December 2021.

Although results skewed toward the use of more positive words, such as “healthy weight,” over terms like “obese,” “fat” or “large,” there was variation across ethnicity, sexual orientation, and weight status. For example, it was noted in the study, funded by WW International, that preference for the word “curvy” was higher among Hispanic/Latino youths, sexual minority youths, and those with a body mass index in the 95th percentile, compared with their White, heterosexual, and lower-weight peers.

Words matter

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics came out with a policy statement on weight stigma and the need for doctors to use more neutral language and less stigmatizing terms in practice when discussing weight among youths.

But one of the reasons this new study is important, said Gregory Germain, MD, associate chief of pediatrics at Yale New Haven (Conn.) Children’s Hospital, is that this study focuses on parents who interact with their kids much more often than a pediatrician who sees them a few times a year.

“Parental motivation, discussion, interaction on a consistent basis – that dialogue is so critical in kids with obesity,” said Germain, who stresses that all adults, coaches, and educators should consider this study as well.

“When we think about those detrimental impacts on mental health when more stigmatizing language is used, just us being more mindful in how we are talking to youth can make such a profound impact,” said Rebecca Kamody, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Yale University, with a research and clinical focus on eating and weight disorders.

“In essence, this is a low-hanging fruit intervention,” she said.

Dr. Kamody recommends we take a lesson from “cultural humility” in psychology to understand how to approach this with kids, calling for “the humbleness as parents or providers in asking someone what they want used to make it the safest place for a discussion with our youth.”

One piece of the puzzle

Dr. Germain and Dr. Kamody agreed that language in discussing this topic is important but that we need to recognize that this topic in general is extremely tricky.

For one, “there are these very real metabolic complications of having high weight at a young age,” said Kamody, who stresses the need for balance to make real change.

Dr. Germain agreed. “Finding a fine line between discussing obesity and not kicking your kid into disordered eating is important.”

The researchers also recognize the limits of an online study, where self-reporting parents may not want to admit using negative weight terminology, but certainly believe it’s a start in identifying some of the undesirable patterns that may be occurring when it comes to weight.

“The overarching message is a positive one, that with our preteens and teenage kids, we need to watch our language, to create a nonjudgmental and safe environment to discuss weight and any issue involved with taking care of themselves,” said Dr. Germain.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PEDIATRICS

FDA expands list of Getinge IABP system and component shortages

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a letter to health care providers describing a current shortage of Getinge intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) catheters and other components.

Earlier, the agency announced shortages of the company’s Maquet/Datascope IAB catheters, new Cardiosave IABP devices, and Cardiosave IABP parts. The new notification adds Getinge Maquet/Datascope IABP systems to the list.

The company’s letter explains that “ongoing supply chain issues have significantly impacted our ability to build intra-aortic balloon pumps, intra-aortic balloon catheters, and spare parts due to raw material shortages.”

It also offers guidance on maintaining Cardiosave Safety Disks and lithium-ion batteries in the face of the shortages. “In the event that you need a replacement pump while your IABP is undergoing service, please contact your local sales representative who may be able to assist with a temporary IABP.”

Providers are instructed to inform the company through its sales representatives “if you have any underutilized Maquet/Datascope IAB catheters or IABPs and are willing to share them with hospitals in need.”

The shortages are expected to continue into 2023, the FDA states in its letter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a letter to health care providers describing a current shortage of Getinge intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) catheters and other components.

Earlier, the agency announced shortages of the company’s Maquet/Datascope IAB catheters, new Cardiosave IABP devices, and Cardiosave IABP parts. The new notification adds Getinge Maquet/Datascope IABP systems to the list.

The company’s letter explains that “ongoing supply chain issues have significantly impacted our ability to build intra-aortic balloon pumps, intra-aortic balloon catheters, and spare parts due to raw material shortages.”

It also offers guidance on maintaining Cardiosave Safety Disks and lithium-ion batteries in the face of the shortages. “In the event that you need a replacement pump while your IABP is undergoing service, please contact your local sales representative who may be able to assist with a temporary IABP.”

Providers are instructed to inform the company through its sales representatives “if you have any underutilized Maquet/Datascope IAB catheters or IABPs and are willing to share them with hospitals in need.”

The shortages are expected to continue into 2023, the FDA states in its letter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a letter to health care providers describing a current shortage of Getinge intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) catheters and other components.

Earlier, the agency announced shortages of the company’s Maquet/Datascope IAB catheters, new Cardiosave IABP devices, and Cardiosave IABP parts. The new notification adds Getinge Maquet/Datascope IABP systems to the list.

The company’s letter explains that “ongoing supply chain issues have significantly impacted our ability to build intra-aortic balloon pumps, intra-aortic balloon catheters, and spare parts due to raw material shortages.”

It also offers guidance on maintaining Cardiosave Safety Disks and lithium-ion batteries in the face of the shortages. “In the event that you need a replacement pump while your IABP is undergoing service, please contact your local sales representative who may be able to assist with a temporary IABP.”

Providers are instructed to inform the company through its sales representatives “if you have any underutilized Maquet/Datascope IAB catheters or IABPs and are willing to share them with hospitals in need.”

The shortages are expected to continue into 2023, the FDA states in its letter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medically speaking, 2022 was the best year yet for children

Headlines from earlier in the fall were grim: Thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy in the United States has fallen for 2 years running. Last year, according to health officials, the average American newborn could hope to reach 76.1 years, down from 79 years in 2019.

So far, so bad. But the headlines don’t tell the full story, which is much less dire. In fact, 2022 is the best year in human history for a child to arrive on Earth.

For a child born this year, in a developed country, into a family with access to good health care, the odds of living into the 22nd century are almost 50%. One in three will live to be 100. Those estimates reflect only incremental progress in medicine and public health, with COVID-19 baked in. They don’t account for biotechnologies beckoning to take control of the cell cycle and aging itself – which could make the outlook much brighter.

For some perspective, consider that a century ago, life expectancy for an American neonate was about 60 years. That 1922 figure was itself nothing short of miraculous, representing a 25% jump since 1901 – a leap that far outstrips the first 2 decades of the current century, during which life expectancy rose by just 2.5 years.

A gain of 2.5 years over 2 decades might not sound impressive, even without COVID-19 causing life expectancy in this country and abroad to sag. But during the pandemic, exciting new technologies that could drive gains in lifespan and healthspan, even bigger than those seen in the early 20th century, have moved closer to clinical reality. Think Star Trek-ish technologies like human hibernation, universal blood, mRNA therapy able to reprogram immune cells to hunt malignancies and fibrotic tissue, even head transplantation.

How long that last one will take to reach a clinic near you is hard to predict, but advances in the needed technology to anastomose cephalic and somatic portions of the spinal cord are mind-boggling. All this means that, from a medical standpoint, the future for babies born in the early 2020s looks dazzlingly bright.

Those sunny rays of optimism likely have failed to pierce the gloom of public discourse. Between “breakthrough infections,” “long COVID,” “Paxlovid rebound,” vaccine-induced myopericarditis, the current respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) outbreak, school shootings, climate change, and the youth mental health crisis, news headlines are undoubtedly frightful.

RSV: What’s old is new again

For the youngest children, the RSV outbreak is currently the scariest story. With social interactions returning toward a pre-COVID state, RSV has rebounded with a vengeance. In many places, pediatric wards are close to, at, or even beyond capacity. With no antiviral treatment for RSV, no licensed vaccine quite yet, and passive immunization (intravenous palivizumab) reserved for children at greatest risk (those under age 6 months and born preterm 35 weeks or earlier), the situation does have the feel of the first year of COVID-19, when treatments were similarly limited.

But let’s keep some perspective. RSV has always been a devastating infection. Prior to COVID-19, in the United States alone RSV killed 100-300 children below age 5 and 6,000-10,000 adults above age 65. The toll has always been worse on the international level. In 2019, 3.6 million people around the world were hospitalized for RSV infections, mostly the very old and the very young. Among causes of death below the age of 5, RSV ranks second only to malaria.

Postvaccine myopericarditis, a favorite concern of the vaccine hesitant, is a real phenomenon in young males. But generally, the condition has a subclinical to mild manifestation and fully resolves within 2 weeks.

Vaccines on the horizon

Monkeypox also was putting a damper on health news in recent months. Yet outreach efforts and selective vaccination and other precautions based on risk stratification appear to have calmed the outbreak. That’s good news, as is the fact that the struggle against malaria may be about to change. After decades of trying, we now have a malaria vaccine with what appears to be 80% efficacy against the infection. The same goes for RSV; finally, not one but two RSV vaccines are showing promise in late-stage clinical trials.

To be sure, for many young people, the times don’t seem so wonderful. The rate of teen suicide is alarming – yet it remains well below that seen in the 1990s. Are social media to blame, or is it something more complex?

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it’s that development of vaccines and treatments need not take a decade or more. Operation Warp Speed may have seemed like a marketing gimmick and political grandstanding, but you can’t argue with the results.

Keep that perspective in mind to appreciate the moment – which I believe is coming soon – when the same type of intramuscular injection that we now use to trigger immunity against SARS-CoV-2 hits clinics, only this time as a way to cure cancer. Or when you read the stories of young victims of firearm violence who would have died but are rapidly cooled and kept hibernating for hours, so that their wounds can be repaired. And although you may not see that head transplant, one of these new babies might see it, or even might perform the procedure.

Dr. Warmflash is a freelance health and science writer living in Portland, Ore. His recent book, Moon: An Illustrated History: From Ancient Myths to the Colonies of Tomorrow, tells the story of the moon’s role in a plethora of historical events, from the origin of life to early calendar systems, the emergence of science and technology, and the dawn of the Space Age. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Headlines from earlier in the fall were grim: Thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy in the United States has fallen for 2 years running. Last year, according to health officials, the average American newborn could hope to reach 76.1 years, down from 79 years in 2019.

So far, so bad. But the headlines don’t tell the full story, which is much less dire. In fact, 2022 is the best year in human history for a child to arrive on Earth.

For a child born this year, in a developed country, into a family with access to good health care, the odds of living into the 22nd century are almost 50%. One in three will live to be 100. Those estimates reflect only incremental progress in medicine and public health, with COVID-19 baked in. They don’t account for biotechnologies beckoning to take control of the cell cycle and aging itself – which could make the outlook much brighter.

For some perspective, consider that a century ago, life expectancy for an American neonate was about 60 years. That 1922 figure was itself nothing short of miraculous, representing a 25% jump since 1901 – a leap that far outstrips the first 2 decades of the current century, during which life expectancy rose by just 2.5 years.

A gain of 2.5 years over 2 decades might not sound impressive, even without COVID-19 causing life expectancy in this country and abroad to sag. But during the pandemic, exciting new technologies that could drive gains in lifespan and healthspan, even bigger than those seen in the early 20th century, have moved closer to clinical reality. Think Star Trek-ish technologies like human hibernation, universal blood, mRNA therapy able to reprogram immune cells to hunt malignancies and fibrotic tissue, even head transplantation.

How long that last one will take to reach a clinic near you is hard to predict, but advances in the needed technology to anastomose cephalic and somatic portions of the spinal cord are mind-boggling. All this means that, from a medical standpoint, the future for babies born in the early 2020s looks dazzlingly bright.

Those sunny rays of optimism likely have failed to pierce the gloom of public discourse. Between “breakthrough infections,” “long COVID,” “Paxlovid rebound,” vaccine-induced myopericarditis, the current respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) outbreak, school shootings, climate change, and the youth mental health crisis, news headlines are undoubtedly frightful.

RSV: What’s old is new again

For the youngest children, the RSV outbreak is currently the scariest story. With social interactions returning toward a pre-COVID state, RSV has rebounded with a vengeance. In many places, pediatric wards are close to, at, or even beyond capacity. With no antiviral treatment for RSV, no licensed vaccine quite yet, and passive immunization (intravenous palivizumab) reserved for children at greatest risk (those under age 6 months and born preterm 35 weeks or earlier), the situation does have the feel of the first year of COVID-19, when treatments were similarly limited.

But let’s keep some perspective. RSV has always been a devastating infection. Prior to COVID-19, in the United States alone RSV killed 100-300 children below age 5 and 6,000-10,000 adults above age 65. The toll has always been worse on the international level. In 2019, 3.6 million people around the world were hospitalized for RSV infections, mostly the very old and the very young. Among causes of death below the age of 5, RSV ranks second only to malaria.

Postvaccine myopericarditis, a favorite concern of the vaccine hesitant, is a real phenomenon in young males. But generally, the condition has a subclinical to mild manifestation and fully resolves within 2 weeks.

Vaccines on the horizon

Monkeypox also was putting a damper on health news in recent months. Yet outreach efforts and selective vaccination and other precautions based on risk stratification appear to have calmed the outbreak. That’s good news, as is the fact that the struggle against malaria may be about to change. After decades of trying, we now have a malaria vaccine with what appears to be 80% efficacy against the infection. The same goes for RSV; finally, not one but two RSV vaccines are showing promise in late-stage clinical trials.

To be sure, for many young people, the times don’t seem so wonderful. The rate of teen suicide is alarming – yet it remains well below that seen in the 1990s. Are social media to blame, or is it something more complex?

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it’s that development of vaccines and treatments need not take a decade or more. Operation Warp Speed may have seemed like a marketing gimmick and political grandstanding, but you can’t argue with the results.

Keep that perspective in mind to appreciate the moment – which I believe is coming soon – when the same type of intramuscular injection that we now use to trigger immunity against SARS-CoV-2 hits clinics, only this time as a way to cure cancer. Or when you read the stories of young victims of firearm violence who would have died but are rapidly cooled and kept hibernating for hours, so that their wounds can be repaired. And although you may not see that head transplant, one of these new babies might see it, or even might perform the procedure.

Dr. Warmflash is a freelance health and science writer living in Portland, Ore. His recent book, Moon: An Illustrated History: From Ancient Myths to the Colonies of Tomorrow, tells the story of the moon’s role in a plethora of historical events, from the origin of life to early calendar systems, the emergence of science and technology, and the dawn of the Space Age. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Headlines from earlier in the fall were grim: Thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy in the United States has fallen for 2 years running. Last year, according to health officials, the average American newborn could hope to reach 76.1 years, down from 79 years in 2019.

So far, so bad. But the headlines don’t tell the full story, which is much less dire. In fact, 2022 is the best year in human history for a child to arrive on Earth.

For a child born this year, in a developed country, into a family with access to good health care, the odds of living into the 22nd century are almost 50%. One in three will live to be 100. Those estimates reflect only incremental progress in medicine and public health, with COVID-19 baked in. They don’t account for biotechnologies beckoning to take control of the cell cycle and aging itself – which could make the outlook much brighter.

For some perspective, consider that a century ago, life expectancy for an American neonate was about 60 years. That 1922 figure was itself nothing short of miraculous, representing a 25% jump since 1901 – a leap that far outstrips the first 2 decades of the current century, during which life expectancy rose by just 2.5 years.

A gain of 2.5 years over 2 decades might not sound impressive, even without COVID-19 causing life expectancy in this country and abroad to sag. But during the pandemic, exciting new technologies that could drive gains in lifespan and healthspan, even bigger than those seen in the early 20th century, have moved closer to clinical reality. Think Star Trek-ish technologies like human hibernation, universal blood, mRNA therapy able to reprogram immune cells to hunt malignancies and fibrotic tissue, even head transplantation.

How long that last one will take to reach a clinic near you is hard to predict, but advances in the needed technology to anastomose cephalic and somatic portions of the spinal cord are mind-boggling. All this means that, from a medical standpoint, the future for babies born in the early 2020s looks dazzlingly bright.

Those sunny rays of optimism likely have failed to pierce the gloom of public discourse. Between “breakthrough infections,” “long COVID,” “Paxlovid rebound,” vaccine-induced myopericarditis, the current respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) outbreak, school shootings, climate change, and the youth mental health crisis, news headlines are undoubtedly frightful.

RSV: What’s old is new again

For the youngest children, the RSV outbreak is currently the scariest story. With social interactions returning toward a pre-COVID state, RSV has rebounded with a vengeance. In many places, pediatric wards are close to, at, or even beyond capacity. With no antiviral treatment for RSV, no licensed vaccine quite yet, and passive immunization (intravenous palivizumab) reserved for children at greatest risk (those under age 6 months and born preterm 35 weeks or earlier), the situation does have the feel of the first year of COVID-19, when treatments were similarly limited.

But let’s keep some perspective. RSV has always been a devastating infection. Prior to COVID-19, in the United States alone RSV killed 100-300 children below age 5 and 6,000-10,000 adults above age 65. The toll has always been worse on the international level. In 2019, 3.6 million people around the world were hospitalized for RSV infections, mostly the very old and the very young. Among causes of death below the age of 5, RSV ranks second only to malaria.

Postvaccine myopericarditis, a favorite concern of the vaccine hesitant, is a real phenomenon in young males. But generally, the condition has a subclinical to mild manifestation and fully resolves within 2 weeks.

Vaccines on the horizon

Monkeypox also was putting a damper on health news in recent months. Yet outreach efforts and selective vaccination and other precautions based on risk stratification appear to have calmed the outbreak. That’s good news, as is the fact that the struggle against malaria may be about to change. After decades of trying, we now have a malaria vaccine with what appears to be 80% efficacy against the infection. The same goes for RSV; finally, not one but two RSV vaccines are showing promise in late-stage clinical trials.

To be sure, for many young people, the times don’t seem so wonderful. The rate of teen suicide is alarming – yet it remains well below that seen in the 1990s. Are social media to blame, or is it something more complex?

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it’s that development of vaccines and treatments need not take a decade or more. Operation Warp Speed may have seemed like a marketing gimmick and political grandstanding, but you can’t argue with the results.

Keep that perspective in mind to appreciate the moment – which I believe is coming soon – when the same type of intramuscular injection that we now use to trigger immunity against SARS-CoV-2 hits clinics, only this time as a way to cure cancer. Or when you read the stories of young victims of firearm violence who would have died but are rapidly cooled and kept hibernating for hours, so that their wounds can be repaired. And although you may not see that head transplant, one of these new babies might see it, or even might perform the procedure.

Dr. Warmflash is a freelance health and science writer living in Portland, Ore. His recent book, Moon: An Illustrated History: From Ancient Myths to the Colonies of Tomorrow, tells the story of the moon’s role in a plethora of historical events, from the origin of life to early calendar systems, the emergence of science and technology, and the dawn of the Space Age. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Employers use patient assistance programs to offset their own costs

Anna Sutton was shocked when she received a letter from her husband’s job-based health plan stating that Humira, an expensive drug used to treat her daughter’s juvenile arthritis, was now on a long list of medications considered “nonessential benefits.”

The July 2021 letter said the family could either participate in a new effort overseen by a company called SaveOnSP and get the drug free of charge or be saddled with a monthly copayment that could top $1,000.

“It really gave us no choice,” said Mrs. Sutton, of Woodinville, Wash. She added that “every single [Food and Drug Administration]–approved medication for juvenile arthritis” was on the list of nonessential benefits.

Mrs. Sutton had unwittingly become part of a strategy that employers are using to deal with the high cost of drugs prescribed to treat conditions such as arthritis, psoriasis, cancer, and hemophilia.

Those employers are tapping into dollars provided through programs they have previously criticized: patient financial assistance initiatives set up by drugmakers, which some benefit managers have complained encourage patients to stay on expensive brand-name drugs when less expensive options might be available.

Now, though, employers, or the vendors and insurers they hire specifically to oversee such efforts, are seeking that money to offset their own costs. Drugmakers object, saying the money was intended primarily for patients. But some benefit brokers and companies like SaveOnSP say they can help trim employers’ spending on insurance – which, they say, could be the difference between an employer offering coverage to workers or not.

It’s the latest twist in a long-running dispute between the drug industry and insurers over which group is more to blame for rising costs to patients. And patients are, again, caught in the middle.

Patient advocates say the term “nonessential” stresses patients out even though it doesn’t mean the drugs – often called “specialty” drugs because of their high prices or the way they are made – are unnecessary.

Some advocates fear the new strategies could be “a way to weed out those with costly health care needs,” said Rachel Klein, deputy executive director of the AIDS Institute, a nonprofit advocacy group. Workers who rely on the drugs may feel pressured to change insurers or jobs.

Two versions of the new strategy are in play. Both are used mainly by self-insured employers that hire vendors, like SaveOnSP, which then work with the employers’ pharmacy benefit managers, such as Express Scripts/Cigna, to implement the strategy. There are also smaller vendors, like SHARx and Payer Matrix, some of which work directly with employers.

In one approach, insurers or employers continue to cover the drugs but designate them as “nonessential,” which allows the health plans to bypass annual limits set by the Affordable Care Act on how much patients can pay in out-of-pocket costs for drugs. The employer or hired vendor then raises the copay required of the worker, often sharply, but offers to substantially cut or eliminate that copay if the patient participates in the new effort. Workers who agree enroll in drugmaker financial assistance programs meant to cover the drug copays, and the vendor monitoring the effort aims to capture the maximum amount the drugmaker provides annually, according to a lawsuit filed in May by drugmaker Johnson & Johnson against SaveOnSP, which is based in Elma, N.Y.

The employer must still cover part of the cost of the drug, but the amount is reduced by the amount of copay assistance that is accessed. That assistance can vary widely and be as much as $20,000 a year for some drugs.

In the other approach, employers don’t bother naming drugs nonessential; they simply drop coverage for specific drugs or classes of drugs. Then, the outside vendor helps patients provide the financial and other information needed to apply for free medication from drugmakers through charity programs intended for uninsured patients.

“We’re seeing it in every state at this point,” said Becky Burns, chief operating officer and chief financial officer at the Bleeding and Clotting Disorders Institute in Peoria, Ill., a federally funded hemophilia treatment center.

The strategies are mostly being used in self-insured employer health plans, which are governed by federal laws that give broad flexibility to employers in designing health benefits.

Still, some patient advocates say these programs can lead to delays for patients in accessing medications while applications are processed – and sometimes unexpected bills for consumers.