User login

Does zinc really help treat colds?

A new study published in BMJ Open adds to the evidence that zinc is effective against viral respiratory infections, such as colds.

Jennifer Hunter, PhD, BMed, of Western Sydney University’s NICM Health Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 28 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). They searched 17 English and Chinese databases to identify the trials and then used the Cochrane rapid review technique for the analysis.

The trials included 5,446 adults who had received zinc in a variety of formulations and routes — oral, sublingual, and nasal spray. The researchers separately analyzed whether zinc prevented or treated respiratory tract infections (RTIs)

Oral or intranasal zinc prevented five RTIs per 100 person-months (95% CI, 1 – 8; numbers needed to treat, 20). There was a 32% lower relative risk (RR) of developing mild to moderate symptoms consistent with a viral RTI.

Use of zinc was also associated with an 87% lower risk of developing moderately severe symptoms (incidence rate ratio, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.04 – 0.38) and a 28% lower risk of developing milder symptoms. The largest reductions in RR were for moderately severe symptoms consistent with an influenza-like illness.

Symptoms resolved 2 days earlier with sublingual or intranasal zinc compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.61 – 3.50; very low-certainty quality of evidence). There were clinically significant reductions in day 3 symptom severity scores (mean difference, -1.20 points; 95% CI, -0.66 to -1.74; low-certainty quality of evidence) but not in overall symptom severity. Participants who used sublingual or topical nasal zinc early in the course of illness were 1.8 times more likely to recover before those who used a placebo.

However, the investigators found no benefit of zinc when patients were inoculated with rhinovirus; there was no reduction in the risk of developing a cold. Asked about this disparity, Dr. Hunter said, “It might well be that when inoculating people to make sure they get infected, you give them a really high dose of the virus. [This] doesn’t really mimic what happens in the real world.”

On the downside of supplemental zinc, there were more side effects among those who used zinc, including nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort, mouth irritation, or soreness from sublingual lozenges (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.17 – 1.69; number needed to harm, 7; moderate-certainty quality of evidence). The risk for a serious adverse event, such as loss of smell or copper deficiency, was low. Although not found in these studies, postmarketing studies have found that there is a risk for severe and in some cases permanent loss of smell associated with the use of nasal gels or sprays containing zinc. Three such products were recalled from the market.

The trial could not provide answers about the comparative efficacy of different types of zinc formulations, nor could the investigators recommend specific doses. The trial was not designed to assess zinc for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

Asked for independent comment, pediatrician Aamer Imdad, MBBS, assistant professor at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, told this news organization, “It’s a very comprehensive review for zinc-related studies in adults” but was challenging because of the “significant clinical heterogeneity in the population.”

Dr. Imdad explained that zinc has “absolutely” been shown to be effective for children with diarrhea. The World Health Organization has recommended it since 2004. “The way it works in diarrhea is that it helps with the regeneration of the epithelium.... It also improves the immunity itself, especially the cell-mediated immunity.” He raised the question of whether it might work similarly in the respiratory tract. Dr. Imdad has a long-standing interest in the use of zinc for pediatric infections. Regarding this study, he concluded, “I think we still need to know the nuts and bolts of this intervention before we can recommend it more specifically.”

Dr. Hunter said, “We don’t have any high-quality studies that have evaluated zinc orally as treatment once you’re actually infected and have symptoms of the cold or influenza, or COVID.”

Asked about zinc’s possible role, Dr. Hunter said, “So I do think it gives us a viable alternative. More people are going, ‘What can I do?’ And you know as well as I do people come to you, and [they say], ‘Well, just give me something. Even if it’s a day or a little bit of symptom relief, anything to make me feel better that isn’t going to hurt me and doesn’t have any major risks.’ So I think in the short term, clinicians and consumers can consider trying it.”

Dr. Hunter was not keen on giving zinc to family members after they develop an RTI: “Consider it. But I don’t think we have enough evidence to say definitely yes.” But she does see a potential role for “people who are at risk of suboptimal zinc absorption, like people who are taking a variety of pharmaceuticals [notably proton pump inhibitors] that block or reduce the absorption of zinc, people with a whole lot of the chronic diseases that we know are associated with an increased risk of worse outcomes from respiratory viral infections, and older adults. Yes, I think [for] those high-risk groups, you could consider using zinc, either in a moderate dose longer term or in a higher dose for very short bursts of, like, 1 to 2 weeks.”

Dr. Hunter concluded, “Up until now, we all commonly thought that zinc’s role was only for people who were zinc deficient, and now we’ve got some signals pointing towards its potential role as an anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agent in people who don’t have zinc deficiency.”

But both Dr. Hunter and Dr. Imdad emphasized that zinc is not a game changer. There is a hint that it produces a small benefit in prevention and may slightly shorten the duration of RTIs. More research is needed.

Dr. Hunter has received payment for providing expert advice about traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine, including nutraceuticals, to industry, government bodies, and nongovernmental organizations and has spoken at workshops, seminars, and conferences for which registration, travel, and/or accommodation has been paid for by the organizers. Dr. Imdad has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study published in BMJ Open adds to the evidence that zinc is effective against viral respiratory infections, such as colds.

Jennifer Hunter, PhD, BMed, of Western Sydney University’s NICM Health Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 28 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). They searched 17 English and Chinese databases to identify the trials and then used the Cochrane rapid review technique for the analysis.

The trials included 5,446 adults who had received zinc in a variety of formulations and routes — oral, sublingual, and nasal spray. The researchers separately analyzed whether zinc prevented or treated respiratory tract infections (RTIs)

Oral or intranasal zinc prevented five RTIs per 100 person-months (95% CI, 1 – 8; numbers needed to treat, 20). There was a 32% lower relative risk (RR) of developing mild to moderate symptoms consistent with a viral RTI.

Use of zinc was also associated with an 87% lower risk of developing moderately severe symptoms (incidence rate ratio, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.04 – 0.38) and a 28% lower risk of developing milder symptoms. The largest reductions in RR were for moderately severe symptoms consistent with an influenza-like illness.

Symptoms resolved 2 days earlier with sublingual or intranasal zinc compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.61 – 3.50; very low-certainty quality of evidence). There were clinically significant reductions in day 3 symptom severity scores (mean difference, -1.20 points; 95% CI, -0.66 to -1.74; low-certainty quality of evidence) but not in overall symptom severity. Participants who used sublingual or topical nasal zinc early in the course of illness were 1.8 times more likely to recover before those who used a placebo.

However, the investigators found no benefit of zinc when patients were inoculated with rhinovirus; there was no reduction in the risk of developing a cold. Asked about this disparity, Dr. Hunter said, “It might well be that when inoculating people to make sure they get infected, you give them a really high dose of the virus. [This] doesn’t really mimic what happens in the real world.”

On the downside of supplemental zinc, there were more side effects among those who used zinc, including nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort, mouth irritation, or soreness from sublingual lozenges (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.17 – 1.69; number needed to harm, 7; moderate-certainty quality of evidence). The risk for a serious adverse event, such as loss of smell or copper deficiency, was low. Although not found in these studies, postmarketing studies have found that there is a risk for severe and in some cases permanent loss of smell associated with the use of nasal gels or sprays containing zinc. Three such products were recalled from the market.

The trial could not provide answers about the comparative efficacy of different types of zinc formulations, nor could the investigators recommend specific doses. The trial was not designed to assess zinc for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

Asked for independent comment, pediatrician Aamer Imdad, MBBS, assistant professor at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, told this news organization, “It’s a very comprehensive review for zinc-related studies in adults” but was challenging because of the “significant clinical heterogeneity in the population.”

Dr. Imdad explained that zinc has “absolutely” been shown to be effective for children with diarrhea. The World Health Organization has recommended it since 2004. “The way it works in diarrhea is that it helps with the regeneration of the epithelium.... It also improves the immunity itself, especially the cell-mediated immunity.” He raised the question of whether it might work similarly in the respiratory tract. Dr. Imdad has a long-standing interest in the use of zinc for pediatric infections. Regarding this study, he concluded, “I think we still need to know the nuts and bolts of this intervention before we can recommend it more specifically.”

Dr. Hunter said, “We don’t have any high-quality studies that have evaluated zinc orally as treatment once you’re actually infected and have symptoms of the cold or influenza, or COVID.”

Asked about zinc’s possible role, Dr. Hunter said, “So I do think it gives us a viable alternative. More people are going, ‘What can I do?’ And you know as well as I do people come to you, and [they say], ‘Well, just give me something. Even if it’s a day or a little bit of symptom relief, anything to make me feel better that isn’t going to hurt me and doesn’t have any major risks.’ So I think in the short term, clinicians and consumers can consider trying it.”

Dr. Hunter was not keen on giving zinc to family members after they develop an RTI: “Consider it. But I don’t think we have enough evidence to say definitely yes.” But she does see a potential role for “people who are at risk of suboptimal zinc absorption, like people who are taking a variety of pharmaceuticals [notably proton pump inhibitors] that block or reduce the absorption of zinc, people with a whole lot of the chronic diseases that we know are associated with an increased risk of worse outcomes from respiratory viral infections, and older adults. Yes, I think [for] those high-risk groups, you could consider using zinc, either in a moderate dose longer term or in a higher dose for very short bursts of, like, 1 to 2 weeks.”

Dr. Hunter concluded, “Up until now, we all commonly thought that zinc’s role was only for people who were zinc deficient, and now we’ve got some signals pointing towards its potential role as an anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agent in people who don’t have zinc deficiency.”

But both Dr. Hunter and Dr. Imdad emphasized that zinc is not a game changer. There is a hint that it produces a small benefit in prevention and may slightly shorten the duration of RTIs. More research is needed.

Dr. Hunter has received payment for providing expert advice about traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine, including nutraceuticals, to industry, government bodies, and nongovernmental organizations and has spoken at workshops, seminars, and conferences for which registration, travel, and/or accommodation has been paid for by the organizers. Dr. Imdad has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study published in BMJ Open adds to the evidence that zinc is effective against viral respiratory infections, such as colds.

Jennifer Hunter, PhD, BMed, of Western Sydney University’s NICM Health Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia, and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 28 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). They searched 17 English and Chinese databases to identify the trials and then used the Cochrane rapid review technique for the analysis.

The trials included 5,446 adults who had received zinc in a variety of formulations and routes — oral, sublingual, and nasal spray. The researchers separately analyzed whether zinc prevented or treated respiratory tract infections (RTIs)

Oral or intranasal zinc prevented five RTIs per 100 person-months (95% CI, 1 – 8; numbers needed to treat, 20). There was a 32% lower relative risk (RR) of developing mild to moderate symptoms consistent with a viral RTI.

Use of zinc was also associated with an 87% lower risk of developing moderately severe symptoms (incidence rate ratio, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.04 – 0.38) and a 28% lower risk of developing milder symptoms. The largest reductions in RR were for moderately severe symptoms consistent with an influenza-like illness.

Symptoms resolved 2 days earlier with sublingual or intranasal zinc compared with placebo (95% CI, 0.61 – 3.50; very low-certainty quality of evidence). There were clinically significant reductions in day 3 symptom severity scores (mean difference, -1.20 points; 95% CI, -0.66 to -1.74; low-certainty quality of evidence) but not in overall symptom severity. Participants who used sublingual or topical nasal zinc early in the course of illness were 1.8 times more likely to recover before those who used a placebo.

However, the investigators found no benefit of zinc when patients were inoculated with rhinovirus; there was no reduction in the risk of developing a cold. Asked about this disparity, Dr. Hunter said, “It might well be that when inoculating people to make sure they get infected, you give them a really high dose of the virus. [This] doesn’t really mimic what happens in the real world.”

On the downside of supplemental zinc, there were more side effects among those who used zinc, including nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort, mouth irritation, or soreness from sublingual lozenges (RR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.17 – 1.69; number needed to harm, 7; moderate-certainty quality of evidence). The risk for a serious adverse event, such as loss of smell or copper deficiency, was low. Although not found in these studies, postmarketing studies have found that there is a risk for severe and in some cases permanent loss of smell associated with the use of nasal gels or sprays containing zinc. Three such products were recalled from the market.

The trial could not provide answers about the comparative efficacy of different types of zinc formulations, nor could the investigators recommend specific doses. The trial was not designed to assess zinc for the prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

Asked for independent comment, pediatrician Aamer Imdad, MBBS, assistant professor at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, told this news organization, “It’s a very comprehensive review for zinc-related studies in adults” but was challenging because of the “significant clinical heterogeneity in the population.”

Dr. Imdad explained that zinc has “absolutely” been shown to be effective for children with diarrhea. The World Health Organization has recommended it since 2004. “The way it works in diarrhea is that it helps with the regeneration of the epithelium.... It also improves the immunity itself, especially the cell-mediated immunity.” He raised the question of whether it might work similarly in the respiratory tract. Dr. Imdad has a long-standing interest in the use of zinc for pediatric infections. Regarding this study, he concluded, “I think we still need to know the nuts and bolts of this intervention before we can recommend it more specifically.”

Dr. Hunter said, “We don’t have any high-quality studies that have evaluated zinc orally as treatment once you’re actually infected and have symptoms of the cold or influenza, or COVID.”

Asked about zinc’s possible role, Dr. Hunter said, “So I do think it gives us a viable alternative. More people are going, ‘What can I do?’ And you know as well as I do people come to you, and [they say], ‘Well, just give me something. Even if it’s a day or a little bit of symptom relief, anything to make me feel better that isn’t going to hurt me and doesn’t have any major risks.’ So I think in the short term, clinicians and consumers can consider trying it.”

Dr. Hunter was not keen on giving zinc to family members after they develop an RTI: “Consider it. But I don’t think we have enough evidence to say definitely yes.” But she does see a potential role for “people who are at risk of suboptimal zinc absorption, like people who are taking a variety of pharmaceuticals [notably proton pump inhibitors] that block or reduce the absorption of zinc, people with a whole lot of the chronic diseases that we know are associated with an increased risk of worse outcomes from respiratory viral infections, and older adults. Yes, I think [for] those high-risk groups, you could consider using zinc, either in a moderate dose longer term or in a higher dose for very short bursts of, like, 1 to 2 weeks.”

Dr. Hunter concluded, “Up until now, we all commonly thought that zinc’s role was only for people who were zinc deficient, and now we’ve got some signals pointing towards its potential role as an anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agent in people who don’t have zinc deficiency.”

But both Dr. Hunter and Dr. Imdad emphasized that zinc is not a game changer. There is a hint that it produces a small benefit in prevention and may slightly shorten the duration of RTIs. More research is needed.

Dr. Hunter has received payment for providing expert advice about traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine, including nutraceuticals, to industry, government bodies, and nongovernmental organizations and has spoken at workshops, seminars, and conferences for which registration, travel, and/or accommodation has been paid for by the organizers. Dr. Imdad has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN

‘First reliable estimate’ of breast cancer metastasis

The data come from a massive meta-analysis of more than 400 studies conducted around the world, involving tens of thousands of women.

It found that the overall risk of metastasis is between 6% and 22%, with younger women having a higher risk.

While women aged 50 years or older when they were diagnosed with breast cancer have a risk of developing metastasis that ranged from 3.7% to 28.6%, women diagnosed with breast cancer before age 35 had a higher risk – 12.7% to 38%. The investigators speculate that this may be because younger women have a more aggressive form of breast cancer or because they are diagnosed at a later stage.

The risk of metastasis also varies by tumor type, with luminal B cancers having a 4.2% to 35.5% risk of metastasis versus a 2.3% to 11.8% risk with luminal A tumors.

“The quantification of recurrence and disease progression is important to assess the effectiveness of treatment, evaluate prognosis, and allocate resources,” commented lead investigator Eileen Morgan, PhD, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Dr. Morgan and colleagues presented the new meta-analysis at the virtual Advanced Breast Cancer Sixth International Consensus Conference.

She added that this information has not been available until now “because cancer registries have not been routinely collecting this data.”

In fact, the U.S. National Cancer Institute began a project earlier this year to track this information, after 48 years of not doing so.

Reacting to the findings, Shani Paluch-Shimon, MBBS, director of the Breast Unit at Hadassah University Hospital, Jerusalem, commented that this work “provides the first reliable estimate of how many breast cancer patients go on to develop advanced disease in contemporary cohorts.”

“This information is, of course, important for patients who want to understand their prognosis,” she continued.

“But it’s also vital at a public health level for those of us working to treat and prevent advanced breast cancer, to help us understand the scale of the disease around the world,” she said. “It will help us identify at-risk groups across different populations and demonstrate how disease course is changing with contemporary treatments.”

“It will also help us understand what resources are needed and where, to ensure we can collect and analyze quality data in real-time as this is key for resource allocation and planning future studies.”

The work was funded by a grant from the Susan G. Komen Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The data come from a massive meta-analysis of more than 400 studies conducted around the world, involving tens of thousands of women.

It found that the overall risk of metastasis is between 6% and 22%, with younger women having a higher risk.

While women aged 50 years or older when they were diagnosed with breast cancer have a risk of developing metastasis that ranged from 3.7% to 28.6%, women diagnosed with breast cancer before age 35 had a higher risk – 12.7% to 38%. The investigators speculate that this may be because younger women have a more aggressive form of breast cancer or because they are diagnosed at a later stage.

The risk of metastasis also varies by tumor type, with luminal B cancers having a 4.2% to 35.5% risk of metastasis versus a 2.3% to 11.8% risk with luminal A tumors.

“The quantification of recurrence and disease progression is important to assess the effectiveness of treatment, evaluate prognosis, and allocate resources,” commented lead investigator Eileen Morgan, PhD, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Dr. Morgan and colleagues presented the new meta-analysis at the virtual Advanced Breast Cancer Sixth International Consensus Conference.

She added that this information has not been available until now “because cancer registries have not been routinely collecting this data.”

In fact, the U.S. National Cancer Institute began a project earlier this year to track this information, after 48 years of not doing so.

Reacting to the findings, Shani Paluch-Shimon, MBBS, director of the Breast Unit at Hadassah University Hospital, Jerusalem, commented that this work “provides the first reliable estimate of how many breast cancer patients go on to develop advanced disease in contemporary cohorts.”

“This information is, of course, important for patients who want to understand their prognosis,” she continued.

“But it’s also vital at a public health level for those of us working to treat and prevent advanced breast cancer, to help us understand the scale of the disease around the world,” she said. “It will help us identify at-risk groups across different populations and demonstrate how disease course is changing with contemporary treatments.”

“It will also help us understand what resources are needed and where, to ensure we can collect and analyze quality data in real-time as this is key for resource allocation and planning future studies.”

The work was funded by a grant from the Susan G. Komen Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The data come from a massive meta-analysis of more than 400 studies conducted around the world, involving tens of thousands of women.

It found that the overall risk of metastasis is between 6% and 22%, with younger women having a higher risk.

While women aged 50 years or older when they were diagnosed with breast cancer have a risk of developing metastasis that ranged from 3.7% to 28.6%, women diagnosed with breast cancer before age 35 had a higher risk – 12.7% to 38%. The investigators speculate that this may be because younger women have a more aggressive form of breast cancer or because they are diagnosed at a later stage.

The risk of metastasis also varies by tumor type, with luminal B cancers having a 4.2% to 35.5% risk of metastasis versus a 2.3% to 11.8% risk with luminal A tumors.

“The quantification of recurrence and disease progression is important to assess the effectiveness of treatment, evaluate prognosis, and allocate resources,” commented lead investigator Eileen Morgan, PhD, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Dr. Morgan and colleagues presented the new meta-analysis at the virtual Advanced Breast Cancer Sixth International Consensus Conference.

She added that this information has not been available until now “because cancer registries have not been routinely collecting this data.”

In fact, the U.S. National Cancer Institute began a project earlier this year to track this information, after 48 years of not doing so.

Reacting to the findings, Shani Paluch-Shimon, MBBS, director of the Breast Unit at Hadassah University Hospital, Jerusalem, commented that this work “provides the first reliable estimate of how many breast cancer patients go on to develop advanced disease in contemporary cohorts.”

“This information is, of course, important for patients who want to understand their prognosis,” she continued.

“But it’s also vital at a public health level for those of us working to treat and prevent advanced breast cancer, to help us understand the scale of the disease around the world,” she said. “It will help us identify at-risk groups across different populations and demonstrate how disease course is changing with contemporary treatments.”

“It will also help us understand what resources are needed and where, to ensure we can collect and analyze quality data in real-time as this is key for resource allocation and planning future studies.”

The work was funded by a grant from the Susan G. Komen Foundation.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Improving Unadjusted and Adjusted Mortality With an Early Warning Sepsis System in the Emergency Department and Inpatient Wards

In 1997, Elizabeth McGlynn wrote, “Measuring quality is no simple task.”1 We are reminded of this seminal Health Affairs article at a very pertinent point—as health care practice progresses, measuring the impact of performance improvement initiatives on clinical care delivery remains integral to monitoring overall effectiveness of quality. Mortality outcomes are a major focus of quality.

Inpatient mortality within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) was measured as actual number of deaths (unadjusted mortality), and adjusted mortality was calculated using the standardized mortality ratio (SMR). SMR included actual number of deaths during hospitalization or within 1 day of hospital discharge divided by predicted number of deaths using a risk-adjusted formula and was calculated separately for acute level of care (LOC) and the intensive care unit (ICU). Using risk-adjusted SMR, if an observed/expected ratio was > 1.0, there were more inpatient deaths than expected; if < 1.0, fewer inpatient deaths occurred than predicted; and if 1.0, observed number of inpatient deaths was equivalent to expected number of deaths.2

Mortality reduction is a complex area of performance improvement. Health care facilities often focus their efforts on the biggest mortality contributors. According to Dantes and Epstein, sepsis results in about 265,000 deaths annually in the United States.3 Reinhart and colleagues demonstrated that sepsis is a worldwide issue resulting in approximately 30 million cases and 6 million deaths annually.4 Furthermore, Kumar and colleagues have noted that when sepsis progresses to septic shock, survival decreases by almost 8% for each hour delay in sepsis identification and treatment.5

Improvements in sepsis management have been multifaceted. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines created sepsis treatment bundles to guide early diagnosis/treatment of sepsis.6 In addition to awareness and sepsis care bundles, a plethora of informatics solutions within electronic health record (EHR) systems have demonstrated improved sepsis care.7-16 Various approaches to early diagnosis and management of sepsis have been collectively referred to as an early warning sepsis system (EWSS).

An EWSS typically contains automated decision support tools that are integrated in the EHR and meant to assist health care professionals with clinical workflow decision-making. Automated decision support tools within the EHR have a variety of functions, such as clinical care reminders and alerts.17

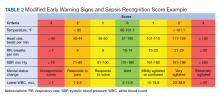

Sepsis screening tools function as a form of automated decision support and may be incorporated into the EHR to support the EWSS. Although sepsis screening tools vary, they frequently include a combination of data involving vital signs, laboratory values and/or physical examination findings, such as mental status evaluation.The Modified Early Warning Signs (MEWS) + Sepsis Recognition Score (SRS) is one example of a sepsis screening tool.7,16

At Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MRVAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, we identified a quality improvement project opportunity to improve sepsis care in the emergency department (ED) and inpatient wards using the VHA EHR system, the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which is supported by the Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA).18 A VistA/CPRS EWSS was developed using Lean Six Sigma DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) methodology.19 During the improve stage, informatics solutions were applied and included a combination of EHR interventions, such as template design, an order set, and clinical reminders. Clinical reminders have a wide variety of use, such as reminders for clinical tasks and as automated decision support within clinical workflows using Boolean logic.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no published application of an EWSS within VistA/CPRS. In this study, we outline the strategic development of an EWSS in VistA/CPRS that assisted clinical staff with identification and treatment of sepsis; improved documentation of sepsis when present; and associated with improvement in unadjusted and adjusted inpatient mortality.

Methods

According to policy activities that constitute research at MRVAMC, no institutional review board approval was required as this work met criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.

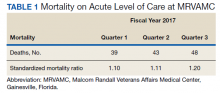

The North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS) includes MRVAMC, a large academic hospital with rotating residents/fellows and multiple specialty care services. MRVAMC comprised 144 beds on the medicine/surgery wards; 48 beds in the psychiatry unit; 18 intermediate LOC beds; and 27 ICU beds. The MRVAMC SMR was identified as an improvement opportunity during fiscal year (FY) 2017 (Table 1). Its adjusted mortality for acute LOC demonstrated an observed/expected ratio of > 1.0 suggesting more inpatient deaths were observed than expected. The number of deaths (unadjusted mortality) on acute LOC at MRVAMC was noted to be rising during the first 3 quarters of FY 2017. A deeper examination of data by Pyramid Analytics (www.pyramidanalytics.com) discovered that sepsis was the primary driver for inpatient mortality on acute LOC at MRVAMC. Our goal was to reduce inpatient sepsis-related mortality via development of an EWSS that leveraged VistA/CPRS to improve early identification and treatment of sepsis in the ED and inpatient wards.

Emergency Department

Given the importance of recognizing sepsis early, the sepsis team focused on improvement opportunities at the initial point of patient contact: ED triage. The goal was to incorporate automated VistA/CPRS decision support to assist clinicians with identifying sepsis in triage using MEWS, which was chosen to optimize immediate hospital-wide buy-in. Clinical staff were already familiar with MEWS, which was in use on the inpatient wards.

Flow through the ED and availability of resources differed from the wards. Hence, modification to MEWS on the wards was necessary to fit clinical workflow in the ED. Temperature, heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), mental status, and white blood cell count (WBC) factored into a MEWS + SRS score on the wards (Table 2). For the ED, MEWS included temperature, HR, RR and SBP, but excluded mental status and WBC. Mental status assessment was excluded due to technical infeasibility (while vital signs could be automatically calculated in real time for a MEWS score, that was not possible for mental status changes). WBC was excluded from the ED as laboratory test results would not be available in triage.

MEWS + SRS scores were calculated in VistA by using clinical reminders. Clinical reminder logic included a series of conditional statements based on various combinations of MEWS + SRS clinical data entered in the EHR. When ED triage vital signs data were entered in CPRS, clinical data were stored and processed according to clinical reminder logic in VistA and displayed to the user in CPRS. While MEWS of ≥ 5 triggered a sepsis alert on the wards, the ≥ 4 threshold was used in the ED given mental status and WBC were excluded from calculations in triage (eAppendix 1 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0194).

Once a sepsis alert was triggered in triage for MEWS ≥ 4, ED nursing staff prioritized bed location and expedited staffing with an ED attending physician for early assessment. The ED attending then performed an assessment to confirm whether sepsis was present and direct early treatment. Although every patient who triggered a sepsis alert in triage did not meet clinical findings of sepsis, patients with MEWS ≥ 4 were frequently ill and required timely intervention.

If an ED attending physician agreed with a sepsis diagnosis, the physician had access to a sepsis workup and treatment order set in CPRS (eAppendix 2 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0194). The sepsis order set incorporated recommendations from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines and included orders for 2 large-bore peripheral IV lines; aggressive fluid resuscitation (30 mL/kg) for patients with clinical findings of hypoperfusion; broad-spectrum antibiotics; and frequent ordering of laboratory tests and imaging during initial sepsis workup.6 Vancomycin and cefepime were selected as routine broad-spectrum antibiotics in the order set when sepsis was suspected based on local antimicrobial stewardship and safety-efficacy profiles. For example, Luther and colleagues demonstrated that cefepime has lower rates of acute kidney injury when combined with vancomycin vs vancomycin + piperacillin-tazobactam.20 If a β-lactam antibiotic could not be used due to a patient’s drug allergy history, aztreonam was available as an alternative option.

The design of the order set also functioned as a communication interface with clinical pharmacists. Given the large volume of antibiotics ordered in the ED, it was difficult for pharmacists to prioritize antibiotic order verification. While stat orders convey high priority, they often lack specificity. When antibiotic orders were selected from the sepsis order set, comments were already included that stated: “STAT. First dose for sepsis protocol” (eAppendix 3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0194). This standardized communication conveyed a sense of urgency and a collective understanding that patients with suspected sepsis required timely order verification and administration of antibiotics.

Hospital Ward

Mental status and WBC were included on the wards to monitor for possible signs of sepsis, using MEWS + SRS, which was routinely monitored by nursing every 4 to 8 hours. When MEWS + SRS was ≥ 5 points, ward nursing staff called a sepsis alert.7,16 Early response team (ERT) members received telephone notifications of the alert. ERT staff proceeded with immediate evaluation and treatment at the bedside along with determination for most appropriate LOC. The ERT members included an ICU physician and nurse; respiratory therapist; and nursing supervisor/bed flow coordinator. During bedside evaluation, if the ERT or primary team agreed with a sepsis diagnosis, the ERT or primary team used the sepsis order set to ensure standardized procedures. Stat orders generated through the sepsis order set pathway conveyed a sense of urgency and need for immediate order verification and administration of antibiotics.

In addition to clinical care process improvement, accurate documentation also was emphasized in the EWSS. When a sepsis alert was called, a clinician from the primary team was expected to complete a standardized progress note, which communicated clinical findings, a treatment plan, and captured severity of illness (eAppendix 4 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0194). It included sections for subjective, objective, assessment, and plan. In addition, data objects were created for vital signs and common laboratory findings that retrieved important clinical data from VistA and inserted it into the CPRS note.21

Nursing staff on the wards were expected to communicate results with the primary team for clinical decision making when a patient had a MEWS + SRS of 3 to 4. A sepsis alert may have been called at the discretion of clinical team members but was not required if the score was < 5. Additionally, vital signs were expected to be checked by the nursing staff on the wards at least every 4 hours for closer monitoring.

Sepsis Review Meetings

Weekly meetings were scheduled to review sepsis cases to assess diagnosis, treatment, and documentation entered in the patient record. The team conducting sepsis reviews comprised the chief of staff, chief of quality management, director of patient safety, physician utilization management advisor, chief resident in quality and patient safety (CRQS), and inpatient pharmacy supervisor. In addition, ad hoc physicians and nurses from different specialty areas, such as infectious diseases, hospitalist section, ICU, and the ED participated on request for subject matter expertise when needed. At the conclusion of weekly sepsis meetings, sepsis team members provided feedback to the clinical staff for continuous improvement purposes.

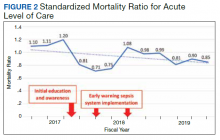

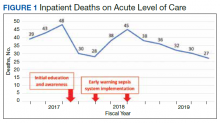

Results

Before implementation of an EWSS at NF/SGVHS, a plan was devised to increase awareness and educate staff on sepsis-related mortality in late FY 2017. Awareness and education about sepsis-related mortality was organized at physician, nursing, and pharmacy leadership clinical staff meetings. Posters about early warning signs of sepsis also were displayed on the nursing units for educational purposes and to convey the importance of early recognition/treatment of sepsis. In addition, the CRQS was the quality leader for house staff and led sepsis campaign change efforts for residents/fellows. An immediate improvement in unadjusted mortality at MRVAMC was noted with initial sepsis awareness and education. From FY 2017, quarter 3 to FY 2018, quarter 1, the number of acute LOC inpatient deaths decreased from 48 to 28, a 42% reduction in unadjusted mortality at MRVAMC (Figure 1). Additionally, the acute LOC SMR improved from 1.20 during FY 2017, quarter 3 down to as low as 0.71 during FY 2018, quarter 1 (Figure 2).

The number of MRVAMC inpatient deaths increased from 28 in FY 2018, quarter 1 to 45 in FY 2018, quarter 3. While acute LOC showed improvement in unadjusted mortality after sepsis education/awareness, it was felt continuous improvement could not be sustained with education alone. An EWSS was designed and implemented within the EHR system in FY 2018. Following implementation of EWSS and reeducating staff on early recognition and treatment of sepsis, acute LOC inpatient deaths decreased from 45 in FY 2018, quarter 3 through FY 2019 where unadjusted mortality was as low as 27 during FY 2019, quarter 4. The MRVAMC acute LOC SMR was consistently < 1.0 from FY 2018, quarter 4 through FY 2019, quarter 4.

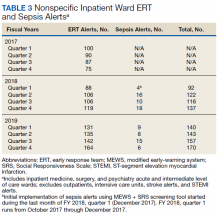

In addition to the observed decrease in acute LOC inpatient deaths and improved SMR, the number of ERT alerts and sepsis alerts on the inpatient wards were monitored from FY 2017 through FY 2019. ERT alerts listed in Table 3 were nonspecific and initiated by nursing staff on the wards where a patient’s clinical status was identified as worsening while sepsis alerts were specific ERT alerts called by the ward nursing staff due to concerns for sepsis. The inpatient wards included inpatient medicine, surgery, and psychiatry acute care and the intermediate level of care unit while outpatient clinical areas of treatment, intensive care units, stroke alerts, and STEMI alerts were excluded.

From FY 2017 to FY 2018, quarter 1, the number of nonspecific ERT alerts varied between 75 to 100. Sepsis alerts were not available until December 2017 while the EWSS was in development. Afterward, nonspecific ERT alerts and sepsis alerts were monitored each quarter. Sepsis alerts ranged from 4 to 18. Nonspecific ERT alerts + sepsis alerts continued to increase from FY 2018, quarter 3 through FY 2019, quarter 4.

Discussion

Implementation of the EWSS was associated with improved unadjusted mortality and adjusted mortality for acute LOC at MRVAMC. Although variation exists with application of EWSS at other medical centers, there was similarity with improved sepsis outcomes reported at other health care systems after EWSS implementation.7-16

Improved unadjusted mortality and adjusted mortality for acute LOC at MRVAMC was likely due to multiple contributing factors. First, during design and implementation of the EWSS, project work was interdisciplinary with input from physicians, nurses, and pharmacists from multiple specialties (ie, ED, ICU, and the medicine service); quality management and data analysis specialists; and clinical informatics. Second, facility commitment to improving early recognition and treatment of sepsis from leadership level down to front-line staff was evident. Weekly sepsis meetings with the NF/SGVHS chief of staff helped to sustain EWSS efforts and to identify additional improvement opportunities. Third, integrated informatics solutions within the EHR helped identify early sepsis and minimized human error as well as assisted with coordination of sepsis care across services. Fourth, the focus was on both early identification and treatment of sepsis in the ED and hospital wards. Although it cannot be deduced whether there was causation between reduced inpatient mortality and an increased number of nonspecific ERT alerts+ sepsis alerts on the inpatient wards after EWSS implementation, inpatient deaths decreased and SMR improved. Finally, the EWSS emphasized both the importance of evidence-based clinical care of sepsis and standardized documentation to appropriately capture clinical severity of illness.

Limitations

This program has limitations. The EWSS was studied at a single VHA facility. Veteran demographics and local epidemiology may limit conclusion of outcomes to an individual VHA facility located in a specific geographical region. Additional research is necessary to demonstrate reproducibility and determine whether applicable to other VHA facilities and community care settings.

SMR is a risk-adjusted formula developed by the VHA Inpatient Evaluation Center, which included numerous factors such as diagnosis, comorbid conditions, age, marital status, procedures, source of admission, specific laboratory values, medical or surgical diagnosis-related group, ICU stays, immunosuppressive status, and a COVID-19 positive indicator (added after this study). Further research is needed to evaluate sepsis-related outcomes using the EWSS during the COVID-19 pandemic.

EWSS in the literature have demonstrated various approaches to early identification and treatment of sepsis and have used different sepsis screening tools.22 Evidence suggests that the MEWS + SRS sepsis screening tool may result in false-positive screenings.23-27 Additional research into the specificity of this sepsis screening tool is needed. Ward nursing staff were encouraged to initiate automatic sepsis alerts when MEWS + SRS was ≥ 5; however, this still depended on human factors. Because sepsis alerts are software-specific and others were incompatible with the VHA EHR, it was necessary to design our own EWSS.

Despite improvement with MRVAMC acute LOC unadjusted and adjusted mortality with our EWSS, we did not identify any actual improvement in earlier antibiotic administration times once sepsis was recognized. While accurate documentation regarding degree of sepsis improved, a MRVAMC clinical documentation improvement program was expanded in FY 2018. Therefore, it is difficult to demonstrate causation related to improved sepsis documentation with template changes alone. While sepsis alerts on the inpatient wards were variable since EWSS implementation, nonspecific ERT alerts increased. It is unclear whether some sepsis alerts were called as nonspecific ERT alerts, making it impossible to know the true number of sepsis alerts.

MRVAMC experienced an increase in nurse turnover during FY 2018 and as a teaching hospital had frequent rotating residents and fellows new to processes/protocols. These factors may have contributed to variations in unadjusted mortality. Also the decrease in inpatient mortality and improvement in SMR on acute LOC could have been the result of factors other than the EWSS and the effect of education alone may have been at least as good as that of the EWSS intervention.

Conclusions

Education along with the possible implementation of an EWSS at NF/SGVHS was associated with a decrease in the number of inpatient deaths on MRVAMC’s acute LOC wards from as high as 48 in FY 2017, quarter 3 to as low as 27 in FY 2019, quarter 4 resulting in as large of an improvement as a 44% reduction in unadjusted mortality from FY 2017 to FY 2019. In addition, MRVAMC’s acute LOC SMR improved from > 1.0 to < 1.0, demonstrating fewer inpatient mortalities than predicted from FY 2017 to FY 2019.

This multifaceted interventional strategy may be effectively applied at other VHA health care facilities that use the same EHR system. Next steps may include determining the specificity of MEWS + SRS as a sepsis screening tool; studying outcomes of MRVAMC’s EWSS during the COVID-19 era; and conducting a multicentered study on this EWSS across multiple VHA facilities.

1. McGlynn EA. Six challenges in measuring the quality of health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 1997;16(3):7-21. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.16.3.7

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) value model measure definitions. Updated May 15, 2019. Accessed October 11, 2021. https://www.va.gov/QUALITYOFCARE/measure-up/SAIL_definitions.asp

3. Dantes RB, Epstein L. Combatting sepsis: a public health perspective. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(8):1300-1302. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy342

4. Reinhart K, Daniels R, Kissoon N, Machado FR, Schachter RD, Finfer S. Recognizing sepsis as a global health priority - a WHO resolution. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):414-417. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1707170

5. Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1589-1596. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9

6. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486-552. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255

7. Guirgis FW, Jones L, Esma R, et al. Managing sepsis: electronic recognition, rapid response teams, and standardized care save lives. J Crit Care. 2017;40:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.04.005

8. Whippy A, Skeath M, Crawford B, et al. Kaiser Permanente’s performance improvement system, part 3: multisite improvements in care for patients with sepsis. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(11):483-493. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37061-4

9. Harrison AM, Thongprayoon C, Kashyap R, et al. Developing the surveillance algorithm for detection of failure to recognize and treat severe sepsis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(2):166-175. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.014

10. Rothman M, Levy M, Dellinger RP, et al. Sepsis as 2 problems: identifying sepsis at admission and predicting onset in the hospital using an electronic medical record-based acuity score. J Crit Care. 2017;38:237-244. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.11.037

11. Back JS, Jin Y, Jin T, Lee SM. Development and validation of an automated sepsis risk assessment system. Res Nurs Health. 2016;39(5):317-327. doi:10.1002/nur.21734

12. Khurana HS, Groves RH Jr, Simons MP, et al. Real-time automated sampling of electronic medical records predicts hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2016;129(7):688-698.e2. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.037

13. Umscheid CA, Betesh J, VanZandbergen C, et al. Development, implementation, and impact of an automated early warning and response system for sepsis. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(1):26-31. doi:10.1002/jhm.2259

14. Vogel L. EMR alert cuts sepsis deaths. CMAJ. 2014;186(2):E80. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4686

15. Jones SL, Ashton CM, Kiehne L, et al. Reductions in sepsis mortality and costs after design and implementation of a nurse-based early recognition and response program. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015;41(11):483-491. doi:10.1016/s1553-7250(15)41063-3

16. Croft CA, Moore FA, Efron PA, et al. Computer versus paper system for recognition and management of sepsis in surgical intensive care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(2):311-319. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000000121

17. Tcheng JE, Bakken S, Bates DW, et al, eds. Optimizing Strategies for Clinical Decision Support: Summary of a Meeting Series. National Academy of Medicine; 2017. Accessed October 11, 2021. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Optimizing-Strategies-for-Clinical-Decision-Support.pdf

18. US Department of Veterans Affairs. History of IT at VA. Updated January 1, 2020. Accessed October 11, 2021. https://www.oit.va.gov/about/history.cfm

19. GoLeanSixSigma. DMAIC: The 5 Phases of Lean Six Sigma. Published 2012. Accessed October 11, 2021. https://goleansixsigma.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/DMAIC-The-5-Phases-of-Lean-Six-Sigma-www.GoLeanSixSigma.com_.pdf

20. Luther MK, Timbrook TT, Caffrey AR, Dosa D, Lodise TP, LaPlante KL. Vancomycin plus piperacillin-tazobactam and acute kidney injury in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(1):12-20. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002769

21. International Business Machines Corp. Overview of data objects. Accessed October 11, 2021. https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/en/SSLTBW_2.3.0/com.ibm.zos.v2r3.cbclx01/data_objects.htm

22. Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, et al. Quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and early warning scores for detecting clinical deterioration in infected patients outside the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(7):906-911. doi:10.1164/rccm.201604-0854OC

23. Ghanem-Zoubi NO, Vardi M, Laor A, Weber G, Bitterman H. Assessment of disease-severity scoring systems for patients with sepsis in general internal medicine departments. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):R95. doi:10.1186/cc10102

24. Hamilton F, Arnold D, Baird A, Albur M, Whiting P. Early Warning scores do not accurately predict mortality in sepsis: a meta-analysis and systematic review of the literature. J Infect. 2018;76(3):241-248. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2018.01.002

25. Martino IF, Figgiaconi V, Seminari E, Muzzi A, Corbella M, Perlini S. The role of qSOFA compared to other prognostic scores in septic patients upon admission to the emergency department. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;53:e11-e13. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2018.05.022

26. Nannan Panday RS, Minderhoud TC, Alam N, Nanayakkara PWB. Prognostic value of early warning scores in the emergency department (ED) and acute medical unit (AMU): A narrative review. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;45:20-31. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2017.09.027

27. Jayasundera R, Neilly M, Smith TO, Myint PK. Are early warning scores useful predictors for mortality and morbidity in hospitalised acutely unwell older patients? A systematic review. J Clin Med. 2018;7(10):309. Published 2018 Sep 28. doi:10.3390/jcm7100309

In 1997, Elizabeth McGlynn wrote, “Measuring quality is no simple task.”1 We are reminded of this seminal Health Affairs article at a very pertinent point—as health care practice progresses, measuring the impact of performance improvement initiatives on clinical care delivery remains integral to monitoring overall effectiveness of quality. Mortality outcomes are a major focus of quality.

Inpatient mortality within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) was measured as actual number of deaths (unadjusted mortality), and adjusted mortality was calculated using the standardized mortality ratio (SMR). SMR included actual number of deaths during hospitalization or within 1 day of hospital discharge divided by predicted number of deaths using a risk-adjusted formula and was calculated separately for acute level of care (LOC) and the intensive care unit (ICU). Using risk-adjusted SMR, if an observed/expected ratio was > 1.0, there were more inpatient deaths than expected; if < 1.0, fewer inpatient deaths occurred than predicted; and if 1.0, observed number of inpatient deaths was equivalent to expected number of deaths.2

Mortality reduction is a complex area of performance improvement. Health care facilities often focus their efforts on the biggest mortality contributors. According to Dantes and Epstein, sepsis results in about 265,000 deaths annually in the United States.3 Reinhart and colleagues demonstrated that sepsis is a worldwide issue resulting in approximately 30 million cases and 6 million deaths annually.4 Furthermore, Kumar and colleagues have noted that when sepsis progresses to septic shock, survival decreases by almost 8% for each hour delay in sepsis identification and treatment.5

Improvements in sepsis management have been multifaceted. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines created sepsis treatment bundles to guide early diagnosis/treatment of sepsis.6 In addition to awareness and sepsis care bundles, a plethora of informatics solutions within electronic health record (EHR) systems have demonstrated improved sepsis care.7-16 Various approaches to early diagnosis and management of sepsis have been collectively referred to as an early warning sepsis system (EWSS).

An EWSS typically contains automated decision support tools that are integrated in the EHR and meant to assist health care professionals with clinical workflow decision-making. Automated decision support tools within the EHR have a variety of functions, such as clinical care reminders and alerts.17

Sepsis screening tools function as a form of automated decision support and may be incorporated into the EHR to support the EWSS. Although sepsis screening tools vary, they frequently include a combination of data involving vital signs, laboratory values and/or physical examination findings, such as mental status evaluation.The Modified Early Warning Signs (MEWS) + Sepsis Recognition Score (SRS) is one example of a sepsis screening tool.7,16

At Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MRVAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, we identified a quality improvement project opportunity to improve sepsis care in the emergency department (ED) and inpatient wards using the VHA EHR system, the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which is supported by the Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA).18 A VistA/CPRS EWSS was developed using Lean Six Sigma DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) methodology.19 During the improve stage, informatics solutions were applied and included a combination of EHR interventions, such as template design, an order set, and clinical reminders. Clinical reminders have a wide variety of use, such as reminders for clinical tasks and as automated decision support within clinical workflows using Boolean logic.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no published application of an EWSS within VistA/CPRS. In this study, we outline the strategic development of an EWSS in VistA/CPRS that assisted clinical staff with identification and treatment of sepsis; improved documentation of sepsis when present; and associated with improvement in unadjusted and adjusted inpatient mortality.

Methods

According to policy activities that constitute research at MRVAMC, no institutional review board approval was required as this work met criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.

The North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS) includes MRVAMC, a large academic hospital with rotating residents/fellows and multiple specialty care services. MRVAMC comprised 144 beds on the medicine/surgery wards; 48 beds in the psychiatry unit; 18 intermediate LOC beds; and 27 ICU beds. The MRVAMC SMR was identified as an improvement opportunity during fiscal year (FY) 2017 (Table 1). Its adjusted mortality for acute LOC demonstrated an observed/expected ratio of > 1.0 suggesting more inpatient deaths were observed than expected. The number of deaths (unadjusted mortality) on acute LOC at MRVAMC was noted to be rising during the first 3 quarters of FY 2017. A deeper examination of data by Pyramid Analytics (www.pyramidanalytics.com) discovered that sepsis was the primary driver for inpatient mortality on acute LOC at MRVAMC. Our goal was to reduce inpatient sepsis-related mortality via development of an EWSS that leveraged VistA/CPRS to improve early identification and treatment of sepsis in the ED and inpatient wards.

Emergency Department

Given the importance of recognizing sepsis early, the sepsis team focused on improvement opportunities at the initial point of patient contact: ED triage. The goal was to incorporate automated VistA/CPRS decision support to assist clinicians with identifying sepsis in triage using MEWS, which was chosen to optimize immediate hospital-wide buy-in. Clinical staff were already familiar with MEWS, which was in use on the inpatient wards.

Flow through the ED and availability of resources differed from the wards. Hence, modification to MEWS on the wards was necessary to fit clinical workflow in the ED. Temperature, heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), mental status, and white blood cell count (WBC) factored into a MEWS + SRS score on the wards (Table 2). For the ED, MEWS included temperature, HR, RR and SBP, but excluded mental status and WBC. Mental status assessment was excluded due to technical infeasibility (while vital signs could be automatically calculated in real time for a MEWS score, that was not possible for mental status changes). WBC was excluded from the ED as laboratory test results would not be available in triage.

MEWS + SRS scores were calculated in VistA by using clinical reminders. Clinical reminder logic included a series of conditional statements based on various combinations of MEWS + SRS clinical data entered in the EHR. When ED triage vital signs data were entered in CPRS, clinical data were stored and processed according to clinical reminder logic in VistA and displayed to the user in CPRS. While MEWS of ≥ 5 triggered a sepsis alert on the wards, the ≥ 4 threshold was used in the ED given mental status and WBC were excluded from calculations in triage (eAppendix 1 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0194).

Once a sepsis alert was triggered in triage for MEWS ≥ 4, ED nursing staff prioritized bed location and expedited staffing with an ED attending physician for early assessment. The ED attending then performed an assessment to confirm whether sepsis was present and direct early treatment. Although every patient who triggered a sepsis alert in triage did not meet clinical findings of sepsis, patients with MEWS ≥ 4 were frequently ill and required timely intervention.

If an ED attending physician agreed with a sepsis diagnosis, the physician had access to a sepsis workup and treatment order set in CPRS (eAppendix 2 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0194). The sepsis order set incorporated recommendations from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines and included orders for 2 large-bore peripheral IV lines; aggressive fluid resuscitation (30 mL/kg) for patients with clinical findings of hypoperfusion; broad-spectrum antibiotics; and frequent ordering of laboratory tests and imaging during initial sepsis workup.6 Vancomycin and cefepime were selected as routine broad-spectrum antibiotics in the order set when sepsis was suspected based on local antimicrobial stewardship and safety-efficacy profiles. For example, Luther and colleagues demonstrated that cefepime has lower rates of acute kidney injury when combined with vancomycin vs vancomycin + piperacillin-tazobactam.20 If a β-lactam antibiotic could not be used due to a patient’s drug allergy history, aztreonam was available as an alternative option.

The design of the order set also functioned as a communication interface with clinical pharmacists. Given the large volume of antibiotics ordered in the ED, it was difficult for pharmacists to prioritize antibiotic order verification. While stat orders convey high priority, they often lack specificity. When antibiotic orders were selected from the sepsis order set, comments were already included that stated: “STAT. First dose for sepsis protocol” (eAppendix 3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0194). This standardized communication conveyed a sense of urgency and a collective understanding that patients with suspected sepsis required timely order verification and administration of antibiotics.

Hospital Ward

Mental status and WBC were included on the wards to monitor for possible signs of sepsis, using MEWS + SRS, which was routinely monitored by nursing every 4 to 8 hours. When MEWS + SRS was ≥ 5 points, ward nursing staff called a sepsis alert.7,16 Early response team (ERT) members received telephone notifications of the alert. ERT staff proceeded with immediate evaluation and treatment at the bedside along with determination for most appropriate LOC. The ERT members included an ICU physician and nurse; respiratory therapist; and nursing supervisor/bed flow coordinator. During bedside evaluation, if the ERT or primary team agreed with a sepsis diagnosis, the ERT or primary team used the sepsis order set to ensure standardized procedures. Stat orders generated through the sepsis order set pathway conveyed a sense of urgency and need for immediate order verification and administration of antibiotics.

In addition to clinical care process improvement, accurate documentation also was emphasized in the EWSS. When a sepsis alert was called, a clinician from the primary team was expected to complete a standardized progress note, which communicated clinical findings, a treatment plan, and captured severity of illness (eAppendix 4 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0194). It included sections for subjective, objective, assessment, and plan. In addition, data objects were created for vital signs and common laboratory findings that retrieved important clinical data from VistA and inserted it into the CPRS note.21

Nursing staff on the wards were expected to communicate results with the primary team for clinical decision making when a patient had a MEWS + SRS of 3 to 4. A sepsis alert may have been called at the discretion of clinical team members but was not required if the score was < 5. Additionally, vital signs were expected to be checked by the nursing staff on the wards at least every 4 hours for closer monitoring.

Sepsis Review Meetings

Weekly meetings were scheduled to review sepsis cases to assess diagnosis, treatment, and documentation entered in the patient record. The team conducting sepsis reviews comprised the chief of staff, chief of quality management, director of patient safety, physician utilization management advisor, chief resident in quality and patient safety (CRQS), and inpatient pharmacy supervisor. In addition, ad hoc physicians and nurses from different specialty areas, such as infectious diseases, hospitalist section, ICU, and the ED participated on request for subject matter expertise when needed. At the conclusion of weekly sepsis meetings, sepsis team members provided feedback to the clinical staff for continuous improvement purposes.

Results

Before implementation of an EWSS at NF/SGVHS, a plan was devised to increase awareness and educate staff on sepsis-related mortality in late FY 2017. Awareness and education about sepsis-related mortality was organized at physician, nursing, and pharmacy leadership clinical staff meetings. Posters about early warning signs of sepsis also were displayed on the nursing units for educational purposes and to convey the importance of early recognition/treatment of sepsis. In addition, the CRQS was the quality leader for house staff and led sepsis campaign change efforts for residents/fellows. An immediate improvement in unadjusted mortality at MRVAMC was noted with initial sepsis awareness and education. From FY 2017, quarter 3 to FY 2018, quarter 1, the number of acute LOC inpatient deaths decreased from 48 to 28, a 42% reduction in unadjusted mortality at MRVAMC (Figure 1). Additionally, the acute LOC SMR improved from 1.20 during FY 2017, quarter 3 down to as low as 0.71 during FY 2018, quarter 1 (Figure 2).

The number of MRVAMC inpatient deaths increased from 28 in FY 2018, quarter 1 to 45 in FY 2018, quarter 3. While acute LOC showed improvement in unadjusted mortality after sepsis education/awareness, it was felt continuous improvement could not be sustained with education alone. An EWSS was designed and implemented within the EHR system in FY 2018. Following implementation of EWSS and reeducating staff on early recognition and treatment of sepsis, acute LOC inpatient deaths decreased from 45 in FY 2018, quarter 3 through FY 2019 where unadjusted mortality was as low as 27 during FY 2019, quarter 4. The MRVAMC acute LOC SMR was consistently < 1.0 from FY 2018, quarter 4 through FY 2019, quarter 4.

In addition to the observed decrease in acute LOC inpatient deaths and improved SMR, the number of ERT alerts and sepsis alerts on the inpatient wards were monitored from FY 2017 through FY 2019. ERT alerts listed in Table 3 were nonspecific and initiated by nursing staff on the wards where a patient’s clinical status was identified as worsening while sepsis alerts were specific ERT alerts called by the ward nursing staff due to concerns for sepsis. The inpatient wards included inpatient medicine, surgery, and psychiatry acute care and the intermediate level of care unit while outpatient clinical areas of treatment, intensive care units, stroke alerts, and STEMI alerts were excluded.

From FY 2017 to FY 2018, quarter 1, the number of nonspecific ERT alerts varied between 75 to 100. Sepsis alerts were not available until December 2017 while the EWSS was in development. Afterward, nonspecific ERT alerts and sepsis alerts were monitored each quarter. Sepsis alerts ranged from 4 to 18. Nonspecific ERT alerts + sepsis alerts continued to increase from FY 2018, quarter 3 through FY 2019, quarter 4.

Discussion

Implementation of the EWSS was associated with improved unadjusted mortality and adjusted mortality for acute LOC at MRVAMC. Although variation exists with application of EWSS at other medical centers, there was similarity with improved sepsis outcomes reported at other health care systems after EWSS implementation.7-16

Improved unadjusted mortality and adjusted mortality for acute LOC at MRVAMC was likely due to multiple contributing factors. First, during design and implementation of the EWSS, project work was interdisciplinary with input from physicians, nurses, and pharmacists from multiple specialties (ie, ED, ICU, and the medicine service); quality management and data analysis specialists; and clinical informatics. Second, facility commitment to improving early recognition and treatment of sepsis from leadership level down to front-line staff was evident. Weekly sepsis meetings with the NF/SGVHS chief of staff helped to sustain EWSS efforts and to identify additional improvement opportunities. Third, integrated informatics solutions within the EHR helped identify early sepsis and minimized human error as well as assisted with coordination of sepsis care across services. Fourth, the focus was on both early identification and treatment of sepsis in the ED and hospital wards. Although it cannot be deduced whether there was causation between reduced inpatient mortality and an increased number of nonspecific ERT alerts+ sepsis alerts on the inpatient wards after EWSS implementation, inpatient deaths decreased and SMR improved. Finally, the EWSS emphasized both the importance of evidence-based clinical care of sepsis and standardized documentation to appropriately capture clinical severity of illness.

Limitations

This program has limitations. The EWSS was studied at a single VHA facility. Veteran demographics and local epidemiology may limit conclusion of outcomes to an individual VHA facility located in a specific geographical region. Additional research is necessary to demonstrate reproducibility and determine whether applicable to other VHA facilities and community care settings.

SMR is a risk-adjusted formula developed by the VHA Inpatient Evaluation Center, which included numerous factors such as diagnosis, comorbid conditions, age, marital status, procedures, source of admission, specific laboratory values, medical or surgical diagnosis-related group, ICU stays, immunosuppressive status, and a COVID-19 positive indicator (added after this study). Further research is needed to evaluate sepsis-related outcomes using the EWSS during the COVID-19 pandemic.

EWSS in the literature have demonstrated various approaches to early identification and treatment of sepsis and have used different sepsis screening tools.22 Evidence suggests that the MEWS + SRS sepsis screening tool may result in false-positive screenings.23-27 Additional research into the specificity of this sepsis screening tool is needed. Ward nursing staff were encouraged to initiate automatic sepsis alerts when MEWS + SRS was ≥ 5; however, this still depended on human factors. Because sepsis alerts are software-specific and others were incompatible with the VHA EHR, it was necessary to design our own EWSS.

Despite improvement with MRVAMC acute LOC unadjusted and adjusted mortality with our EWSS, we did not identify any actual improvement in earlier antibiotic administration times once sepsis was recognized. While accurate documentation regarding degree of sepsis improved, a MRVAMC clinical documentation improvement program was expanded in FY 2018. Therefore, it is difficult to demonstrate causation related to improved sepsis documentation with template changes alone. While sepsis alerts on the inpatient wards were variable since EWSS implementation, nonspecific ERT alerts increased. It is unclear whether some sepsis alerts were called as nonspecific ERT alerts, making it impossible to know the true number of sepsis alerts.

MRVAMC experienced an increase in nurse turnover during FY 2018 and as a teaching hospital had frequent rotating residents and fellows new to processes/protocols. These factors may have contributed to variations in unadjusted mortality. Also the decrease in inpatient mortality and improvement in SMR on acute LOC could have been the result of factors other than the EWSS and the effect of education alone may have been at least as good as that of the EWSS intervention.

Conclusions

Education along with the possible implementation of an EWSS at NF/SGVHS was associated with a decrease in the number of inpatient deaths on MRVAMC’s acute LOC wards from as high as 48 in FY 2017, quarter 3 to as low as 27 in FY 2019, quarter 4 resulting in as large of an improvement as a 44% reduction in unadjusted mortality from FY 2017 to FY 2019. In addition, MRVAMC’s acute LOC SMR improved from > 1.0 to < 1.0, demonstrating fewer inpatient mortalities than predicted from FY 2017 to FY 2019.

This multifaceted interventional strategy may be effectively applied at other VHA health care facilities that use the same EHR system. Next steps may include determining the specificity of MEWS + SRS as a sepsis screening tool; studying outcomes of MRVAMC’s EWSS during the COVID-19 era; and conducting a multicentered study on this EWSS across multiple VHA facilities.

In 1997, Elizabeth McGlynn wrote, “Measuring quality is no simple task.”1 We are reminded of this seminal Health Affairs article at a very pertinent point—as health care practice progresses, measuring the impact of performance improvement initiatives on clinical care delivery remains integral to monitoring overall effectiveness of quality. Mortality outcomes are a major focus of quality.

Inpatient mortality within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) was measured as actual number of deaths (unadjusted mortality), and adjusted mortality was calculated using the standardized mortality ratio (SMR). SMR included actual number of deaths during hospitalization or within 1 day of hospital discharge divided by predicted number of deaths using a risk-adjusted formula and was calculated separately for acute level of care (LOC) and the intensive care unit (ICU). Using risk-adjusted SMR, if an observed/expected ratio was > 1.0, there were more inpatient deaths than expected; if < 1.0, fewer inpatient deaths occurred than predicted; and if 1.0, observed number of inpatient deaths was equivalent to expected number of deaths.2

Mortality reduction is a complex area of performance improvement. Health care facilities often focus their efforts on the biggest mortality contributors. According to Dantes and Epstein, sepsis results in about 265,000 deaths annually in the United States.3 Reinhart and colleagues demonstrated that sepsis is a worldwide issue resulting in approximately 30 million cases and 6 million deaths annually.4 Furthermore, Kumar and colleagues have noted that when sepsis progresses to septic shock, survival decreases by almost 8% for each hour delay in sepsis identification and treatment.5

Improvements in sepsis management have been multifaceted. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines created sepsis treatment bundles to guide early diagnosis/treatment of sepsis.6 In addition to awareness and sepsis care bundles, a plethora of informatics solutions within electronic health record (EHR) systems have demonstrated improved sepsis care.7-16 Various approaches to early diagnosis and management of sepsis have been collectively referred to as an early warning sepsis system (EWSS).

An EWSS typically contains automated decision support tools that are integrated in the EHR and meant to assist health care professionals with clinical workflow decision-making. Automated decision support tools within the EHR have a variety of functions, such as clinical care reminders and alerts.17

Sepsis screening tools function as a form of automated decision support and may be incorporated into the EHR to support the EWSS. Although sepsis screening tools vary, they frequently include a combination of data involving vital signs, laboratory values and/or physical examination findings, such as mental status evaluation.The Modified Early Warning Signs (MEWS) + Sepsis Recognition Score (SRS) is one example of a sepsis screening tool.7,16

At Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MRVAMC) in Gainesville, Florida, we identified a quality improvement project opportunity to improve sepsis care in the emergency department (ED) and inpatient wards using the VHA EHR system, the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), which is supported by the Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA).18 A VistA/CPRS EWSS was developed using Lean Six Sigma DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) methodology.19 During the improve stage, informatics solutions were applied and included a combination of EHR interventions, such as template design, an order set, and clinical reminders. Clinical reminders have a wide variety of use, such as reminders for clinical tasks and as automated decision support within clinical workflows using Boolean logic.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no published application of an EWSS within VistA/CPRS. In this study, we outline the strategic development of an EWSS in VistA/CPRS that assisted clinical staff with identification and treatment of sepsis; improved documentation of sepsis when present; and associated with improvement in unadjusted and adjusted inpatient mortality.

Methods

According to policy activities that constitute research at MRVAMC, no institutional review board approval was required as this work met criteria for operational improvement activities exempt from ethics review.