User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'medstat-accordion-set article-series')]

Cutaneous lupus, dermatomyositis: Excitement growing around emerging therapies

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — Advances in treating medical conditions rarely emerge in a straight line. Oftentimes, progress comes in fits and starts, and therapies to treat cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) and dermatomyositis are no exception.

Beyond approved treatments that deserve more attention, like belimumab, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in 2011, and Octagam 10%, an intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) preparation approved for dermatomyositis in 2021, anticipation is growing for emerging therapies and their potential to provide relief to patients, Anthony Fernandez, MD, PhD, said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. The tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor deucravacitinib, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors brepocitinib and baricitinib, and the monoclonal antibody anifrolumab, he noted, are prime examples.

“. In my opinion, this is the start of what will be the most exciting decade in the history of these two diseases,” said Dr. Fernandez, director of medical dermatology at the Cleveland Clinic.

Emerging Treatments for Cutaneous Lupus

Although SLE can involve many organ systems, the skin is one of the most affected. There are specific cutaneous lesions categorized as either acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, or chronic cutaneous lupus.

The oral TYK2 inhibitor deucravacitinib, for example, should be able to dampen interleukin responses in people with CLE, Dr. Fernandez said. Deucravacitinib was approved by the FDA to treat psoriasis in September 2022.

A phase 2 study published in 2023 focused on this agent for relief of systemic lupus. Improvements in cutaneous disease were a secondary endpoint. The trial demonstrated that the patients treated with deucravacitinib achieved a 56%-70% CLASI-50 response, depending on dosing, compared with a 17% response among those on placebo at week 48.

Based on the trial results, recruitment has begun for a phase 2 trial to evaluate deucravacitinib, compared with placebo, in patients with discoid and/or subacute cutaneous lupus. “This may be another medicine we have available to give to any of our patients with cutaneous lupus,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Anifrolumab Appears Promising

The FDA approval of anifrolumab, a type I interferon (IFN) receptor antagonist, for treating moderate to severe SLE in July 2021, for example, is good news for dermatologists and their patients, added Dr. Fernandez. “Almost immediately after approval, case studies showed marked improvement in patients with refractory cutaneous lupus.” While the therapy was approved for treating systemic lupus, it allows for off-label treatment of the cutaneous predominant form of the disease, he said.

Furthermore, the manufacturer of anifrolumab, AstraZeneca, is launching the LAVENDER clinical trial to assess the monoclonal antibody specifically for treating CLE. “This is a big deal because we may be able to prescribe anifrolumab for our cutaneous lupus patients who don’t have systemic lupus,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Phase 3 data supported use the of anifrolumab in systemic lupus, including the TULIP-2 trial, which demonstrated its superiority to placebo for reducing severity of systemic disease and lowering corticosteroid use. A study published in March 2023 of 11 patients showed that they had a “very fast response” to the agent, Dr. Fernandez said, with a 50% or greater improvement in the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index activity score reached by all participants at week 16. Improvements of 50% or more in this scoring system are considered clinically meaningful, he added.

Upcoming Dermatomyositis Treatments

Why highlight emerging therapies for CLE and dermatomyositis in the same ODAC presentation? Although distinct conditions, these autoimmune conditions are both mediated by type 1 IFN inflammation.

Dermatomyositis is a relatively rare immune-mediated disease that most commonly affects the skin and muscle. Doctors score disease presentation, activity, and clinical improvements on a scale similar to CLASI for cutaneous lupus, the CDASI or Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index. Among people with CDASI activity scores of at least 14, which is the threshold for moderate to severe disease, a 20% improvement is clinically meaningful, Dr. Fernandez said. In addition, a 40% or greater improvement correlates with significant improvements in quality of life.

There is now more evidence for the use of IVIG to treat dermatomyositis. “Among those of us who treat dermatomyositis on a regular basis, we believe IVIG is the most potent treatment. We’ve known that for a long time,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Despite this tenet, for years, there was only one placebo-controlled trial, published in 1993, that evaluated IVIG treatment for dermatomyositis, and it included only 15 participants. That was until October 2022, he said, when the New England Journal of Medicine published a study comparing a specific brand of IVIG (Octagam) with placebo in 95 people with dermatomyositis.

In the study, 79% of participants treated with IVIG had a total improvement score of at least 20 (minimal improvement), the primary endpoint, at 16 weeks, compared with 44% of those receiving a placebo. Those treated with IVIG also had significant improvements in the CDASI score, a secondary endpoint, compared with those on placebo, he said.

Based on results of this trial, the FDA approved Octagam 10% for dermatomyositis in adults. Dr. Fernandez noted the approval is restricted to the brand of IVIG in the trial, not all IVIG products. However, “the FDA approval is most important to us because it gives us ammunition to fight for insurers to approve IVIG when we feel our patients with dermatomyositis need it,” regardless of the brand.

The Potential of JAK1 Inhibitors

An open-label study of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, published in December 2020, showed that mean changes in CDASI activity scores at 12 weeks were statistically significant compared with baseline in 10 people with dermatomyositis. “The importance of this study is that it is proof of concept that JAK inhibition can be effective for treating dermatomyositis, especially with active skin disease,” Dr. Fernandez said.

In addition, two large phase 3 trials are evaluating JAK inhibitor safety and efficacy for treating dermatomyositis. One is the VALOR trial, currently recruiting people with recalcitrant dermatomyositis to evaluate treatment with brepocitinib. Researchers in France are looking at another JAK inhibitor, baricitinib, for treating relapsing or treatment-naive dermatomyositis. Recruitment for the BIRD clinical trial is ongoing.

Monoclonal Antibody Showing Promise

“When it comes to looking specifically at dermatomyositis cutaneous disease, it’s been found that the levels of IFN beta correlate best with not only lesional skin type 1 IFN inflammatory signatures but also overall clinical disease activity,” Dr. Fernandez said. This correlation is stronger than for any other IFN-1-type cytokine active in the disorder.

“Perhaps blocking IFN beta might be best way to get control of dermatomyositis activity,” he added.

With that in mind, a phase 2 trial of dazukibart presented at the American Academy of Dermatology 2023 annual meeting highlighted the promise of this agent that targets type 1 IFN beta.

The primary endpoint was improvement in CDASI at 12 weeks. “This medication has remarkable efficacy,” Dr. Fernandez said. “We were one of the sites for this trial. Despite being blinded, there was no question about who was receiving drug and who was receiving placebo.”

“A minimal clinical improvement in disease activity was seen in more than 90%, so almost every patient who received this medication had meaningful improvement,” he added.

Based on the results, the manufacturer, Pfizer, is recruiting participants for a phase 3 trial to further assess dazukibart in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Dr. Fernandez said, “This is a story you should pay attention to if you treat any dermatomyositis patients at all.”

Regarding these emerging therapies for CLE and dermatomyositis, “This looks very much like the early days of psoriasis, in the early 2000s, when there was a lot of activity developing treatments,” Dr. Fernandez said. “I will predict that within 10 years, we will have multiple novel agents available that will probably work better than anything we have today.”

Dr. Fernandez reported receiving grant and/or research support from Alexion, Incyte, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer, and Priovant Therapeutics; acting as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Biogen, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals; and being a member of the speaker bureau or receiving honoraria for non-CME from AbbVie, Kyowa Kirin, and Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — Advances in treating medical conditions rarely emerge in a straight line. Oftentimes, progress comes in fits and starts, and therapies to treat cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) and dermatomyositis are no exception.

Beyond approved treatments that deserve more attention, like belimumab, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in 2011, and Octagam 10%, an intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) preparation approved for dermatomyositis in 2021, anticipation is growing for emerging therapies and their potential to provide relief to patients, Anthony Fernandez, MD, PhD, said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. The tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor deucravacitinib, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors brepocitinib and baricitinib, and the monoclonal antibody anifrolumab, he noted, are prime examples.

“. In my opinion, this is the start of what will be the most exciting decade in the history of these two diseases,” said Dr. Fernandez, director of medical dermatology at the Cleveland Clinic.

Emerging Treatments for Cutaneous Lupus

Although SLE can involve many organ systems, the skin is one of the most affected. There are specific cutaneous lesions categorized as either acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, or chronic cutaneous lupus.

The oral TYK2 inhibitor deucravacitinib, for example, should be able to dampen interleukin responses in people with CLE, Dr. Fernandez said. Deucravacitinib was approved by the FDA to treat psoriasis in September 2022.

A phase 2 study published in 2023 focused on this agent for relief of systemic lupus. Improvements in cutaneous disease were a secondary endpoint. The trial demonstrated that the patients treated with deucravacitinib achieved a 56%-70% CLASI-50 response, depending on dosing, compared with a 17% response among those on placebo at week 48.

Based on the trial results, recruitment has begun for a phase 2 trial to evaluate deucravacitinib, compared with placebo, in patients with discoid and/or subacute cutaneous lupus. “This may be another medicine we have available to give to any of our patients with cutaneous lupus,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Anifrolumab Appears Promising

The FDA approval of anifrolumab, a type I interferon (IFN) receptor antagonist, for treating moderate to severe SLE in July 2021, for example, is good news for dermatologists and their patients, added Dr. Fernandez. “Almost immediately after approval, case studies showed marked improvement in patients with refractory cutaneous lupus.” While the therapy was approved for treating systemic lupus, it allows for off-label treatment of the cutaneous predominant form of the disease, he said.

Furthermore, the manufacturer of anifrolumab, AstraZeneca, is launching the LAVENDER clinical trial to assess the monoclonal antibody specifically for treating CLE. “This is a big deal because we may be able to prescribe anifrolumab for our cutaneous lupus patients who don’t have systemic lupus,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Phase 3 data supported use the of anifrolumab in systemic lupus, including the TULIP-2 trial, which demonstrated its superiority to placebo for reducing severity of systemic disease and lowering corticosteroid use. A study published in March 2023 of 11 patients showed that they had a “very fast response” to the agent, Dr. Fernandez said, with a 50% or greater improvement in the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index activity score reached by all participants at week 16. Improvements of 50% or more in this scoring system are considered clinically meaningful, he added.

Upcoming Dermatomyositis Treatments

Why highlight emerging therapies for CLE and dermatomyositis in the same ODAC presentation? Although distinct conditions, these autoimmune conditions are both mediated by type 1 IFN inflammation.

Dermatomyositis is a relatively rare immune-mediated disease that most commonly affects the skin and muscle. Doctors score disease presentation, activity, and clinical improvements on a scale similar to CLASI for cutaneous lupus, the CDASI or Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index. Among people with CDASI activity scores of at least 14, which is the threshold for moderate to severe disease, a 20% improvement is clinically meaningful, Dr. Fernandez said. In addition, a 40% or greater improvement correlates with significant improvements in quality of life.

There is now more evidence for the use of IVIG to treat dermatomyositis. “Among those of us who treat dermatomyositis on a regular basis, we believe IVIG is the most potent treatment. We’ve known that for a long time,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Despite this tenet, for years, there was only one placebo-controlled trial, published in 1993, that evaluated IVIG treatment for dermatomyositis, and it included only 15 participants. That was until October 2022, he said, when the New England Journal of Medicine published a study comparing a specific brand of IVIG (Octagam) with placebo in 95 people with dermatomyositis.

In the study, 79% of participants treated with IVIG had a total improvement score of at least 20 (minimal improvement), the primary endpoint, at 16 weeks, compared with 44% of those receiving a placebo. Those treated with IVIG also had significant improvements in the CDASI score, a secondary endpoint, compared with those on placebo, he said.

Based on results of this trial, the FDA approved Octagam 10% for dermatomyositis in adults. Dr. Fernandez noted the approval is restricted to the brand of IVIG in the trial, not all IVIG products. However, “the FDA approval is most important to us because it gives us ammunition to fight for insurers to approve IVIG when we feel our patients with dermatomyositis need it,” regardless of the brand.

The Potential of JAK1 Inhibitors

An open-label study of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, published in December 2020, showed that mean changes in CDASI activity scores at 12 weeks were statistically significant compared with baseline in 10 people with dermatomyositis. “The importance of this study is that it is proof of concept that JAK inhibition can be effective for treating dermatomyositis, especially with active skin disease,” Dr. Fernandez said.

In addition, two large phase 3 trials are evaluating JAK inhibitor safety and efficacy for treating dermatomyositis. One is the VALOR trial, currently recruiting people with recalcitrant dermatomyositis to evaluate treatment with brepocitinib. Researchers in France are looking at another JAK inhibitor, baricitinib, for treating relapsing or treatment-naive dermatomyositis. Recruitment for the BIRD clinical trial is ongoing.

Monoclonal Antibody Showing Promise

“When it comes to looking specifically at dermatomyositis cutaneous disease, it’s been found that the levels of IFN beta correlate best with not only lesional skin type 1 IFN inflammatory signatures but also overall clinical disease activity,” Dr. Fernandez said. This correlation is stronger than for any other IFN-1-type cytokine active in the disorder.

“Perhaps blocking IFN beta might be best way to get control of dermatomyositis activity,” he added.

With that in mind, a phase 2 trial of dazukibart presented at the American Academy of Dermatology 2023 annual meeting highlighted the promise of this agent that targets type 1 IFN beta.

The primary endpoint was improvement in CDASI at 12 weeks. “This medication has remarkable efficacy,” Dr. Fernandez said. “We were one of the sites for this trial. Despite being blinded, there was no question about who was receiving drug and who was receiving placebo.”

“A minimal clinical improvement in disease activity was seen in more than 90%, so almost every patient who received this medication had meaningful improvement,” he added.

Based on the results, the manufacturer, Pfizer, is recruiting participants for a phase 3 trial to further assess dazukibart in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Dr. Fernandez said, “This is a story you should pay attention to if you treat any dermatomyositis patients at all.”

Regarding these emerging therapies for CLE and dermatomyositis, “This looks very much like the early days of psoriasis, in the early 2000s, when there was a lot of activity developing treatments,” Dr. Fernandez said. “I will predict that within 10 years, we will have multiple novel agents available that will probably work better than anything we have today.”

Dr. Fernandez reported receiving grant and/or research support from Alexion, Incyte, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer, and Priovant Therapeutics; acting as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Biogen, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals; and being a member of the speaker bureau or receiving honoraria for non-CME from AbbVie, Kyowa Kirin, and Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — Advances in treating medical conditions rarely emerge in a straight line. Oftentimes, progress comes in fits and starts, and therapies to treat cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) and dermatomyositis are no exception.

Beyond approved treatments that deserve more attention, like belimumab, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in 2011, and Octagam 10%, an intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) preparation approved for dermatomyositis in 2021, anticipation is growing for emerging therapies and their potential to provide relief to patients, Anthony Fernandez, MD, PhD, said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference. The tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor deucravacitinib, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors brepocitinib and baricitinib, and the monoclonal antibody anifrolumab, he noted, are prime examples.

“. In my opinion, this is the start of what will be the most exciting decade in the history of these two diseases,” said Dr. Fernandez, director of medical dermatology at the Cleveland Clinic.

Emerging Treatments for Cutaneous Lupus

Although SLE can involve many organ systems, the skin is one of the most affected. There are specific cutaneous lesions categorized as either acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, or chronic cutaneous lupus.

The oral TYK2 inhibitor deucravacitinib, for example, should be able to dampen interleukin responses in people with CLE, Dr. Fernandez said. Deucravacitinib was approved by the FDA to treat psoriasis in September 2022.

A phase 2 study published in 2023 focused on this agent for relief of systemic lupus. Improvements in cutaneous disease were a secondary endpoint. The trial demonstrated that the patients treated with deucravacitinib achieved a 56%-70% CLASI-50 response, depending on dosing, compared with a 17% response among those on placebo at week 48.

Based on the trial results, recruitment has begun for a phase 2 trial to evaluate deucravacitinib, compared with placebo, in patients with discoid and/or subacute cutaneous lupus. “This may be another medicine we have available to give to any of our patients with cutaneous lupus,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Anifrolumab Appears Promising

The FDA approval of anifrolumab, a type I interferon (IFN) receptor antagonist, for treating moderate to severe SLE in July 2021, for example, is good news for dermatologists and their patients, added Dr. Fernandez. “Almost immediately after approval, case studies showed marked improvement in patients with refractory cutaneous lupus.” While the therapy was approved for treating systemic lupus, it allows for off-label treatment of the cutaneous predominant form of the disease, he said.

Furthermore, the manufacturer of anifrolumab, AstraZeneca, is launching the LAVENDER clinical trial to assess the monoclonal antibody specifically for treating CLE. “This is a big deal because we may be able to prescribe anifrolumab for our cutaneous lupus patients who don’t have systemic lupus,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Phase 3 data supported use the of anifrolumab in systemic lupus, including the TULIP-2 trial, which demonstrated its superiority to placebo for reducing severity of systemic disease and lowering corticosteroid use. A study published in March 2023 of 11 patients showed that they had a “very fast response” to the agent, Dr. Fernandez said, with a 50% or greater improvement in the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index activity score reached by all participants at week 16. Improvements of 50% or more in this scoring system are considered clinically meaningful, he added.

Upcoming Dermatomyositis Treatments

Why highlight emerging therapies for CLE and dermatomyositis in the same ODAC presentation? Although distinct conditions, these autoimmune conditions are both mediated by type 1 IFN inflammation.

Dermatomyositis is a relatively rare immune-mediated disease that most commonly affects the skin and muscle. Doctors score disease presentation, activity, and clinical improvements on a scale similar to CLASI for cutaneous lupus, the CDASI or Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index. Among people with CDASI activity scores of at least 14, which is the threshold for moderate to severe disease, a 20% improvement is clinically meaningful, Dr. Fernandez said. In addition, a 40% or greater improvement correlates with significant improvements in quality of life.

There is now more evidence for the use of IVIG to treat dermatomyositis. “Among those of us who treat dermatomyositis on a regular basis, we believe IVIG is the most potent treatment. We’ve known that for a long time,” Dr. Fernandez said.

Despite this tenet, for years, there was only one placebo-controlled trial, published in 1993, that evaluated IVIG treatment for dermatomyositis, and it included only 15 participants. That was until October 2022, he said, when the New England Journal of Medicine published a study comparing a specific brand of IVIG (Octagam) with placebo in 95 people with dermatomyositis.

In the study, 79% of participants treated with IVIG had a total improvement score of at least 20 (minimal improvement), the primary endpoint, at 16 weeks, compared with 44% of those receiving a placebo. Those treated with IVIG also had significant improvements in the CDASI score, a secondary endpoint, compared with those on placebo, he said.

Based on results of this trial, the FDA approved Octagam 10% for dermatomyositis in adults. Dr. Fernandez noted the approval is restricted to the brand of IVIG in the trial, not all IVIG products. However, “the FDA approval is most important to us because it gives us ammunition to fight for insurers to approve IVIG when we feel our patients with dermatomyositis need it,” regardless of the brand.

The Potential of JAK1 Inhibitors

An open-label study of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, published in December 2020, showed that mean changes in CDASI activity scores at 12 weeks were statistically significant compared with baseline in 10 people with dermatomyositis. “The importance of this study is that it is proof of concept that JAK inhibition can be effective for treating dermatomyositis, especially with active skin disease,” Dr. Fernandez said.

In addition, two large phase 3 trials are evaluating JAK inhibitor safety and efficacy for treating dermatomyositis. One is the VALOR trial, currently recruiting people with recalcitrant dermatomyositis to evaluate treatment with brepocitinib. Researchers in France are looking at another JAK inhibitor, baricitinib, for treating relapsing or treatment-naive dermatomyositis. Recruitment for the BIRD clinical trial is ongoing.

Monoclonal Antibody Showing Promise

“When it comes to looking specifically at dermatomyositis cutaneous disease, it’s been found that the levels of IFN beta correlate best with not only lesional skin type 1 IFN inflammatory signatures but also overall clinical disease activity,” Dr. Fernandez said. This correlation is stronger than for any other IFN-1-type cytokine active in the disorder.

“Perhaps blocking IFN beta might be best way to get control of dermatomyositis activity,” he added.

With that in mind, a phase 2 trial of dazukibart presented at the American Academy of Dermatology 2023 annual meeting highlighted the promise of this agent that targets type 1 IFN beta.

The primary endpoint was improvement in CDASI at 12 weeks. “This medication has remarkable efficacy,” Dr. Fernandez said. “We were one of the sites for this trial. Despite being blinded, there was no question about who was receiving drug and who was receiving placebo.”

“A minimal clinical improvement in disease activity was seen in more than 90%, so almost every patient who received this medication had meaningful improvement,” he added.

Based on the results, the manufacturer, Pfizer, is recruiting participants for a phase 3 trial to further assess dazukibart in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Dr. Fernandez said, “This is a story you should pay attention to if you treat any dermatomyositis patients at all.”

Regarding these emerging therapies for CLE and dermatomyositis, “This looks very much like the early days of psoriasis, in the early 2000s, when there was a lot of activity developing treatments,” Dr. Fernandez said. “I will predict that within 10 years, we will have multiple novel agents available that will probably work better than anything we have today.”

Dr. Fernandez reported receiving grant and/or research support from Alexion, Incyte, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer, and Priovant Therapeutics; acting as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Biogen, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals; and being a member of the speaker bureau or receiving honoraria for non-CME from AbbVie, Kyowa Kirin, and Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ODAC 2024

Dana-Farber Moves to Retract, Correct Dozens of Cancer Papers Amid Allegations

News of the investigation follows a blog post by British molecular biologist Sholto David, MD, who flagged almost 60 papers published between 1997 and 2017 that contained image manipulation and other errors. Some of the papers were published by Dana-Farber’s chief executive officer, Laurie Glimcher, MD, and chief operating officer, William Hahn, MD, on topics including multiple myeloma and immune cells.

Mr. David, who blogs about research integrity, highlighted numerous errors and irregularities, including copying and pasting images across multiple experiments to represent different days within the same experiment, sometimes rotating or stretching images.

In one case, Mr. David equated the manipulation with tactics used by “hapless Chinese papermills” and concluded that “a swathe of research coming out of [Dana-Farber] authored by the most senior researchers and managers appears to be hopelessly corrupt with errors that are obvious from just a cursory reading the papers.”

“Imagine what mistakes might be found in the raw data if anyone was allowed to look!” he wrote.

Barrett Rollins, MD, PhD, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s research integrity officer, declined to comment on whether the errors represent scientific misconduct, according to STAT. Rollins told ScienceInsider that the “presence of image discrepancies in a paper is not evidence of an author’s intent to deceive.”

Access to new artificial intelligence tools is making it easier for data sleuths, like Mr. David, to unearth data manipulation and errors.

The current investigation closely follows two other investigations into the published work of Harvard University’s former president, Claudine Gay, and Stanford University’s former president, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, which led both to resign their posts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

News of the investigation follows a blog post by British molecular biologist Sholto David, MD, who flagged almost 60 papers published between 1997 and 2017 that contained image manipulation and other errors. Some of the papers were published by Dana-Farber’s chief executive officer, Laurie Glimcher, MD, and chief operating officer, William Hahn, MD, on topics including multiple myeloma and immune cells.

Mr. David, who blogs about research integrity, highlighted numerous errors and irregularities, including copying and pasting images across multiple experiments to represent different days within the same experiment, sometimes rotating or stretching images.

In one case, Mr. David equated the manipulation with tactics used by “hapless Chinese papermills” and concluded that “a swathe of research coming out of [Dana-Farber] authored by the most senior researchers and managers appears to be hopelessly corrupt with errors that are obvious from just a cursory reading the papers.”

“Imagine what mistakes might be found in the raw data if anyone was allowed to look!” he wrote.

Barrett Rollins, MD, PhD, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s research integrity officer, declined to comment on whether the errors represent scientific misconduct, according to STAT. Rollins told ScienceInsider that the “presence of image discrepancies in a paper is not evidence of an author’s intent to deceive.”

Access to new artificial intelligence tools is making it easier for data sleuths, like Mr. David, to unearth data manipulation and errors.

The current investigation closely follows two other investigations into the published work of Harvard University’s former president, Claudine Gay, and Stanford University’s former president, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, which led both to resign their posts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

News of the investigation follows a blog post by British molecular biologist Sholto David, MD, who flagged almost 60 papers published between 1997 and 2017 that contained image manipulation and other errors. Some of the papers were published by Dana-Farber’s chief executive officer, Laurie Glimcher, MD, and chief operating officer, William Hahn, MD, on topics including multiple myeloma and immune cells.

Mr. David, who blogs about research integrity, highlighted numerous errors and irregularities, including copying and pasting images across multiple experiments to represent different days within the same experiment, sometimes rotating or stretching images.

In one case, Mr. David equated the manipulation with tactics used by “hapless Chinese papermills” and concluded that “a swathe of research coming out of [Dana-Farber] authored by the most senior researchers and managers appears to be hopelessly corrupt with errors that are obvious from just a cursory reading the papers.”

“Imagine what mistakes might be found in the raw data if anyone was allowed to look!” he wrote.

Barrett Rollins, MD, PhD, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s research integrity officer, declined to comment on whether the errors represent scientific misconduct, according to STAT. Rollins told ScienceInsider that the “presence of image discrepancies in a paper is not evidence of an author’s intent to deceive.”

Access to new artificial intelligence tools is making it easier for data sleuths, like Mr. David, to unearth data manipulation and errors.

The current investigation closely follows two other investigations into the published work of Harvard University’s former president, Claudine Gay, and Stanford University’s former president, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, which led both to resign their posts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Even Intentional Weight Loss Linked With Cancer

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As anyone who has been through medical training will tell you, some little scenes just stick with you. I had been seeing a patient in our resident clinic in West Philly for a couple of years. She was in her mid-60s with diabetes and hypertension and a distant smoking history. She was overweight and had been trying to improve her diet and lose weight since I started seeing her. One day she came in and was delighted to report that she had finally started shedding some pounds — about 15 in the past 2 months.

I enthusiastically told my preceptor that my careful dietary counseling had finally done the job. She looked through the chart for a moment and asked, “Is she up to date on her cancer screening?” A workup revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. The patient did well, actually, but the story stuck with me.

The textbooks call it “unintentional weight loss,” often in big, scary letters, and every doctor will go just a bit pale if a patient tells them that, despite efforts not to, they are losing weight. But true unintentional weight loss is not that common. After all, most of us are at least half-heartedly trying to lose weight all the time. Should doctors be worried when we are successful?

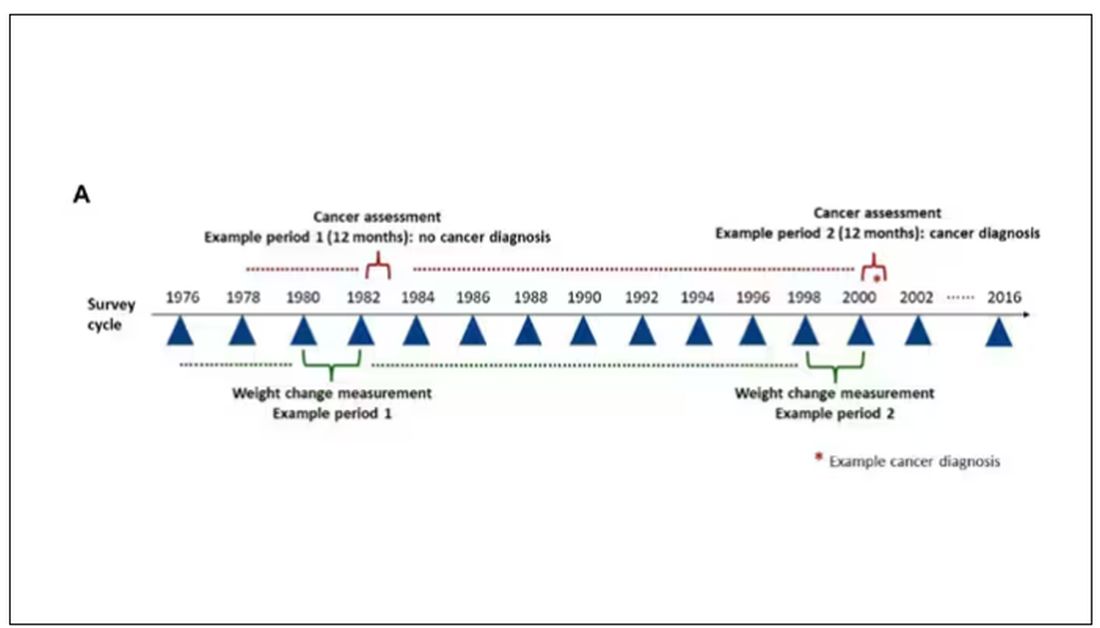

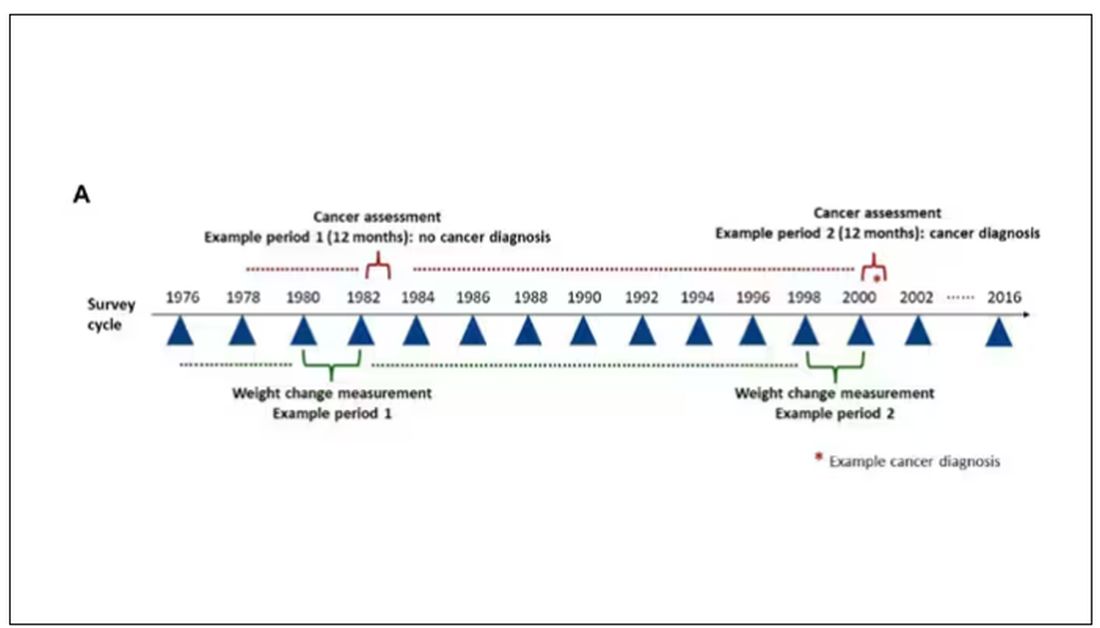

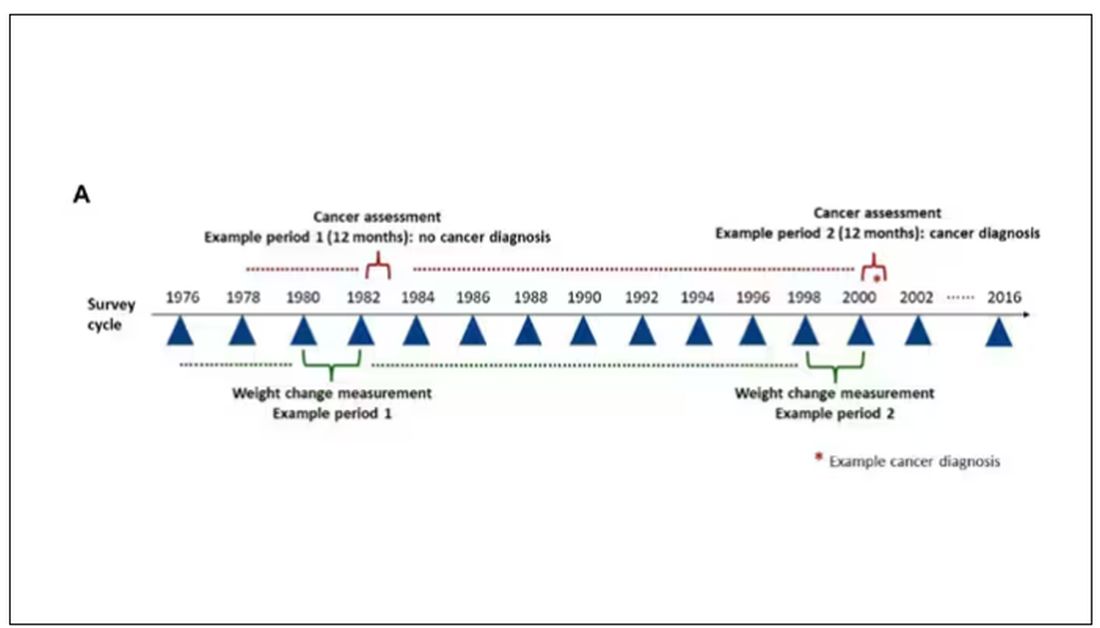

A new study suggests that perhaps they should. We’re talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, which combined participants from two long-running observational cohorts: 120,000 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, and 50,000 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. (These cohorts started in the 1970s and 1980s, so we’ll give them a pass on the gender-specific study designs.)

The rationale of enrolling healthcare providers in these cohort studies is that they would be reliable witnesses of their own health status. If a nurse or doctor says they have pancreatic cancer, it’s likely that they truly have pancreatic cancer. Detailed health surveys were distributed to the participants every other year, and the average follow-up was more than a decade.

Participants recorded their weight — as an aside, a nested study found that self-reported rate was extremely well correlated with professionally measured weight — and whether they had received a cancer diagnosis since the last survey.

This allowed researchers to look at the phenomenon described above. Would weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer? And, more interestingly, would intentional weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer.

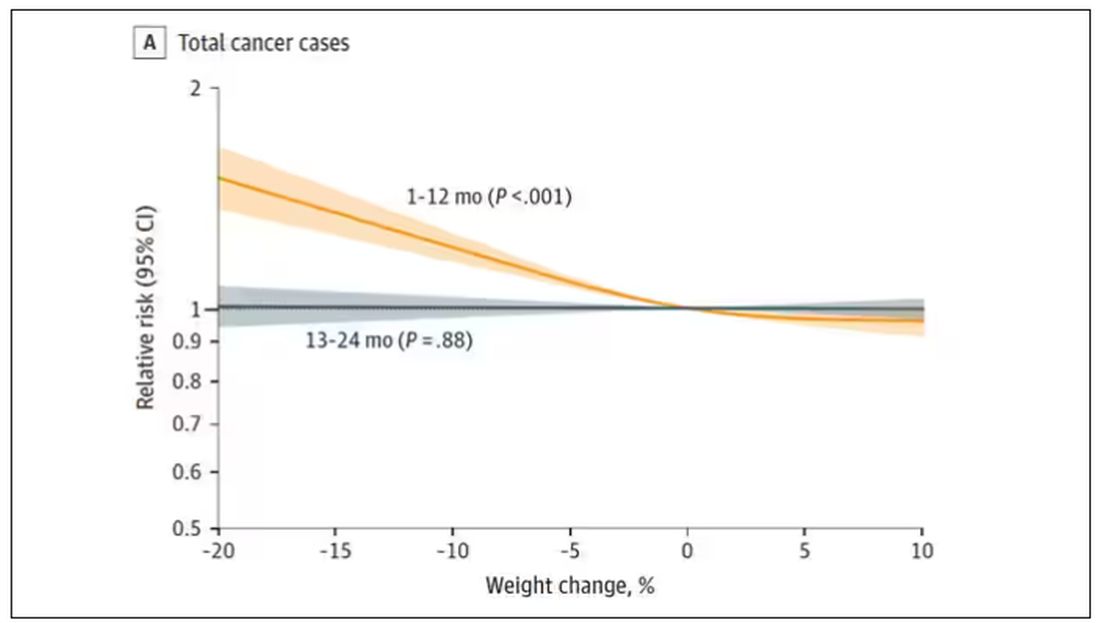

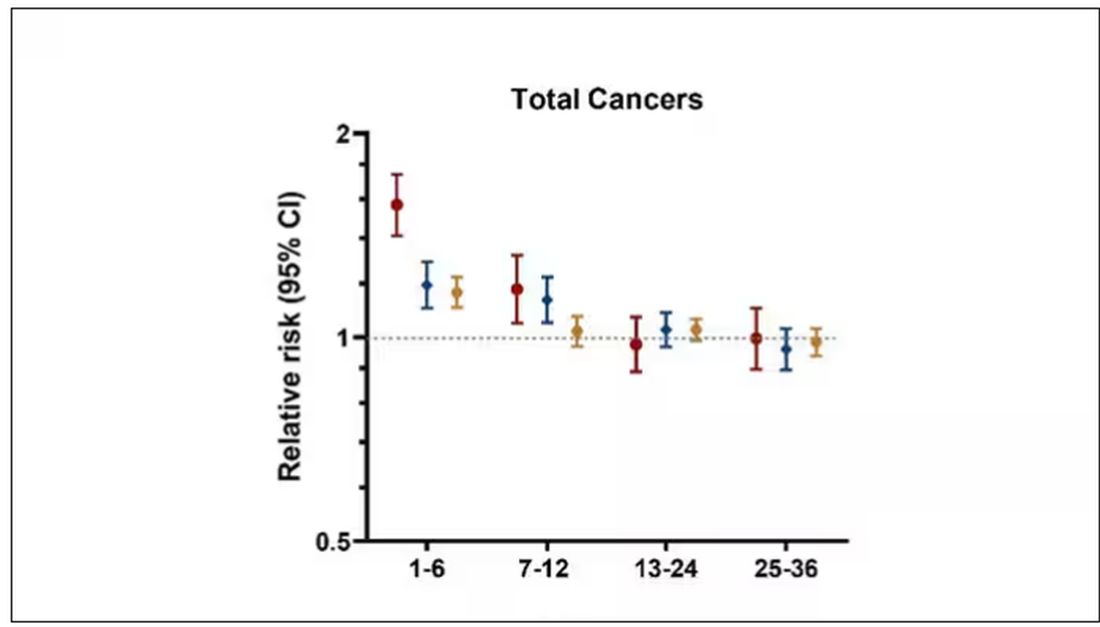

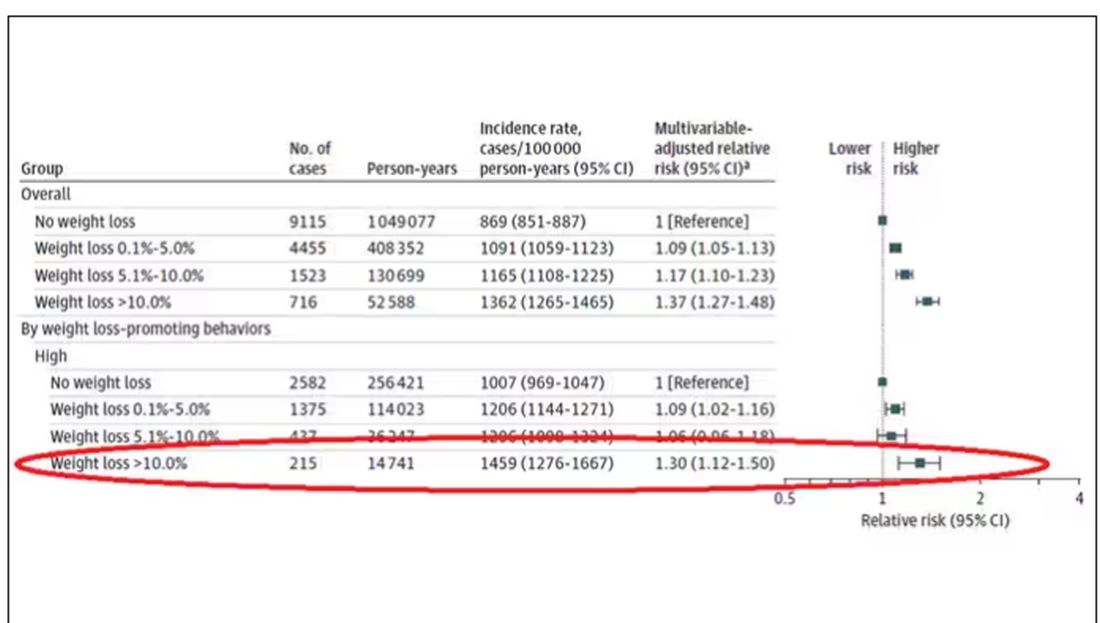

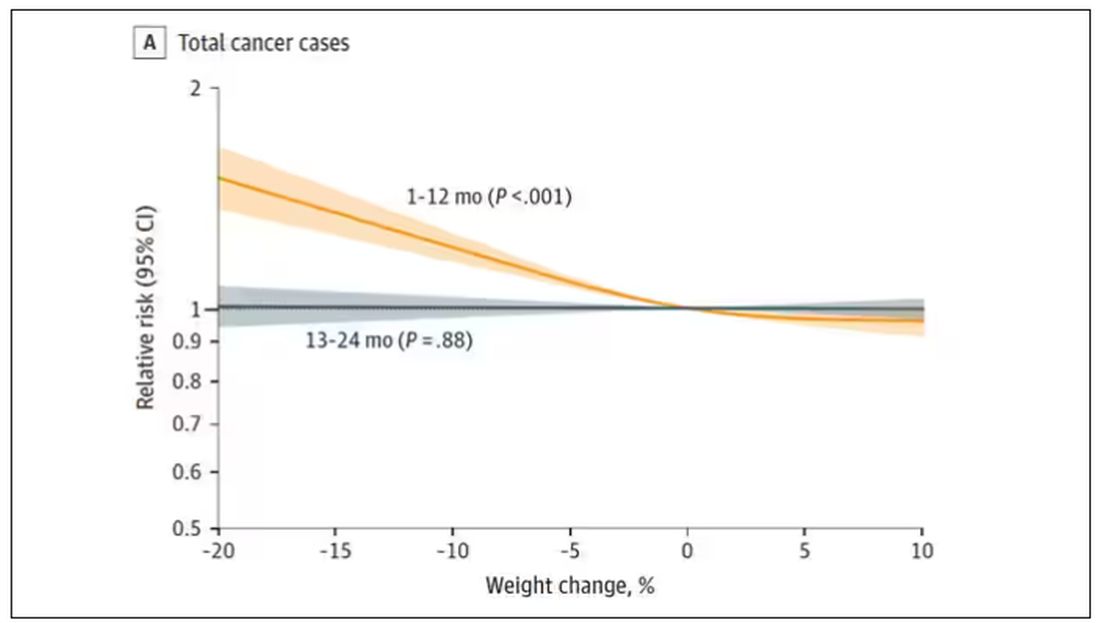

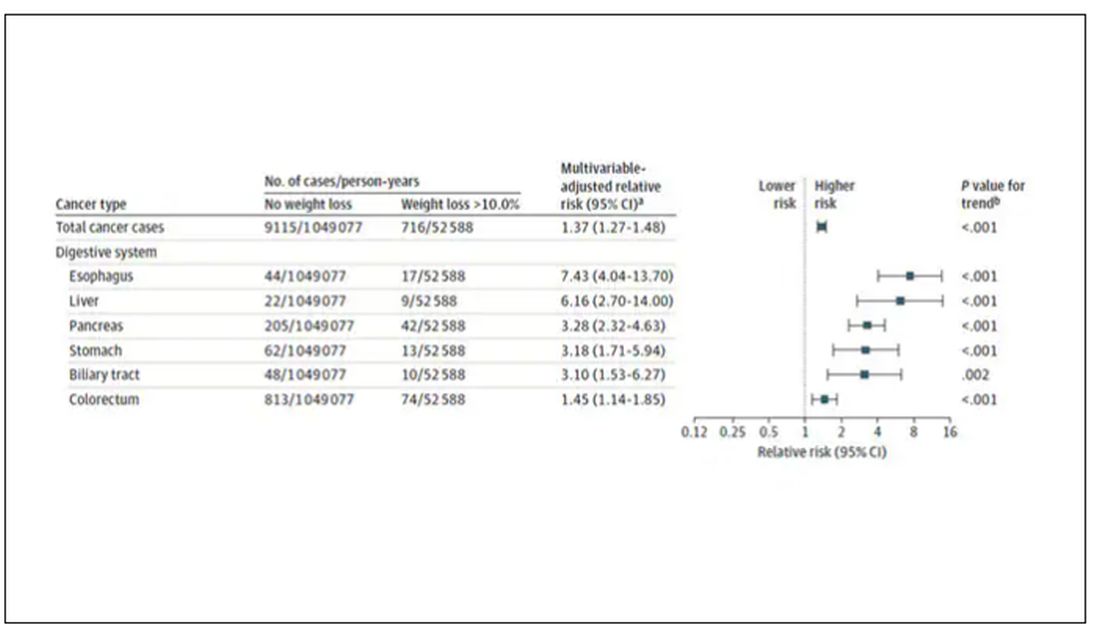

I don’t think it will surprise you to hear that individuals in the highest category of weight loss, those who lost more than 10% of their body weight over a 2-year period, had a larger risk of being diagnosed with cancer in the next year. That’s the yellow line in this graph. In fact, they had about a 40% higher risk than those who did not lose weight.

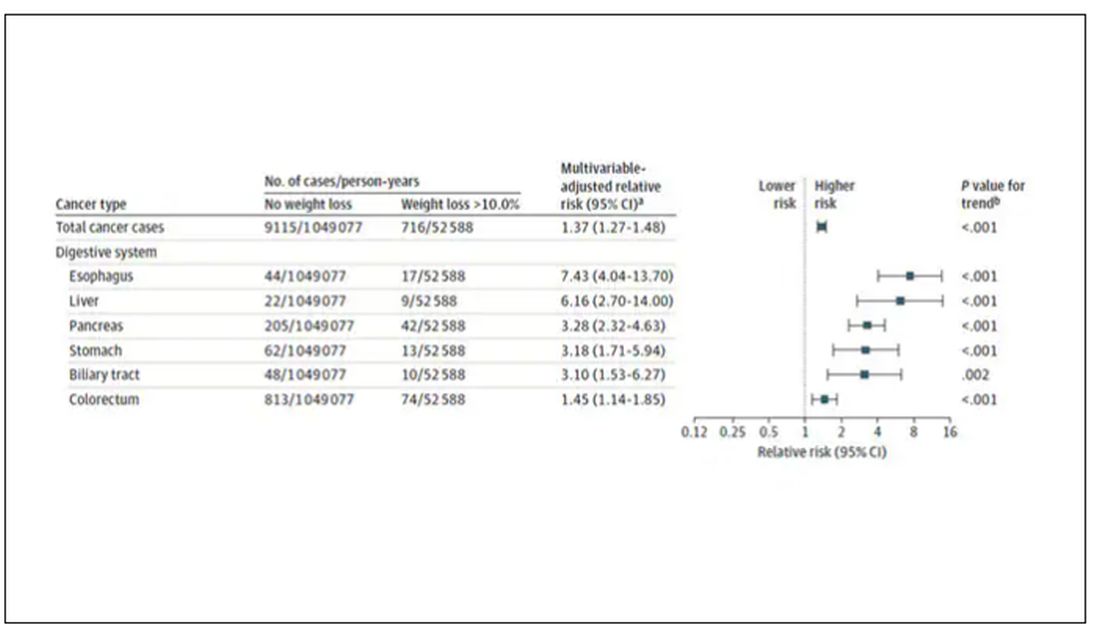

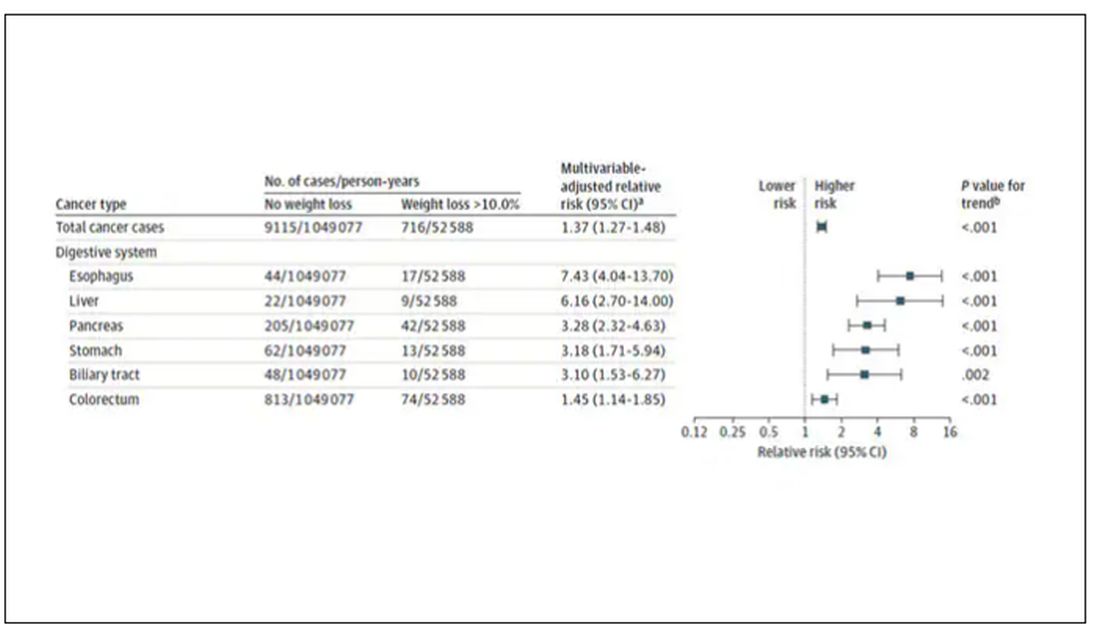

Increased risk was found across multiple cancer types, though cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, not surprisingly, were most strongly associated with antecedent weight loss.

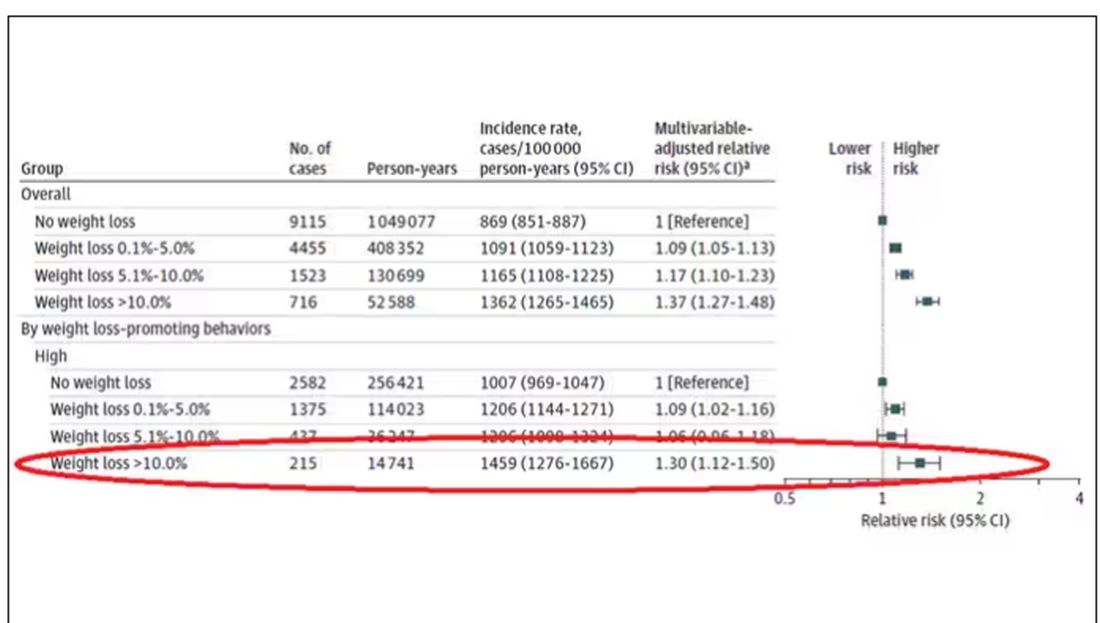

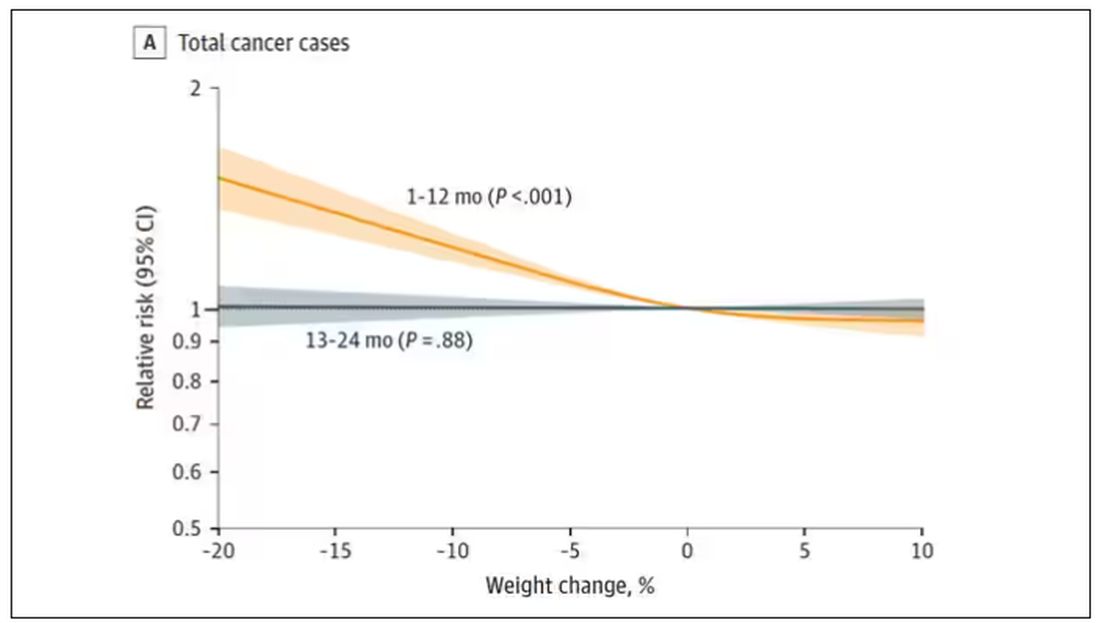

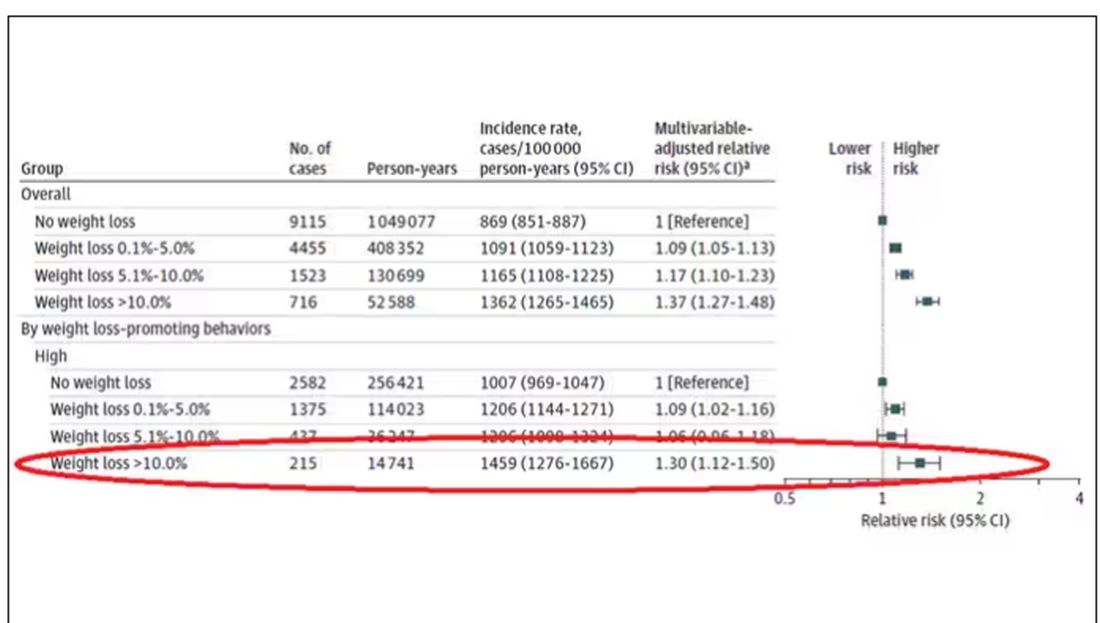

What about intentionality of weight loss? Unfortunately, the surveys did not ask participants whether they were trying to lose weight. Rather, the surveys asked about exercise and dietary habits. The researchers leveraged these responses to create three categories of participants: those who seemed to be trying to lose weight (defined as people who had increased their exercise and dietary quality); those who didn’t seem to be trying to lose weight (they changed neither exercise nor dietary behaviors); and a middle group, which changed one or the other of these behaviors but not both.

Let’s look at those who really seemed to be trying to lose weight. Over 2 years, they got more exercise and improved their diet.

If they succeeded in losing 10% or more of their body weight, they still had a higher risk for cancer than those who had not lost weight — about 30% higher, which is not that different from the 40% increased risk when you include those folks who weren’t changing their lifestyle.

This is why this study is important. The classic teaching is that unintentional weight loss is a bad thing and needs a workup. That’s fine. But we live in a world where perhaps the majority of people are, at any given time, trying to lose weight.

We need to be careful here. I am not by any means trying to say that people who have successfully lost weight have cancer. Both of the following statements can be true:

Significant weight loss, whether intentional or not, is associated with a higher risk for cancer.

Most people with significant weight loss will not have cancer.

Both of these can be true because cancer is, fortunately, rare. Of people who lose weight, the vast majority will lose weight because they are engaging in healthier behaviors. A small number may lose weight because something else is wrong. It’s just hard to tell the two apart.

Out of the nearly 200,000 people in this study, only around 16,000 developed cancer during follow-up. Again, although the chance of having cancer is slightly higher if someone has experienced weight loss, the chance is still very low.

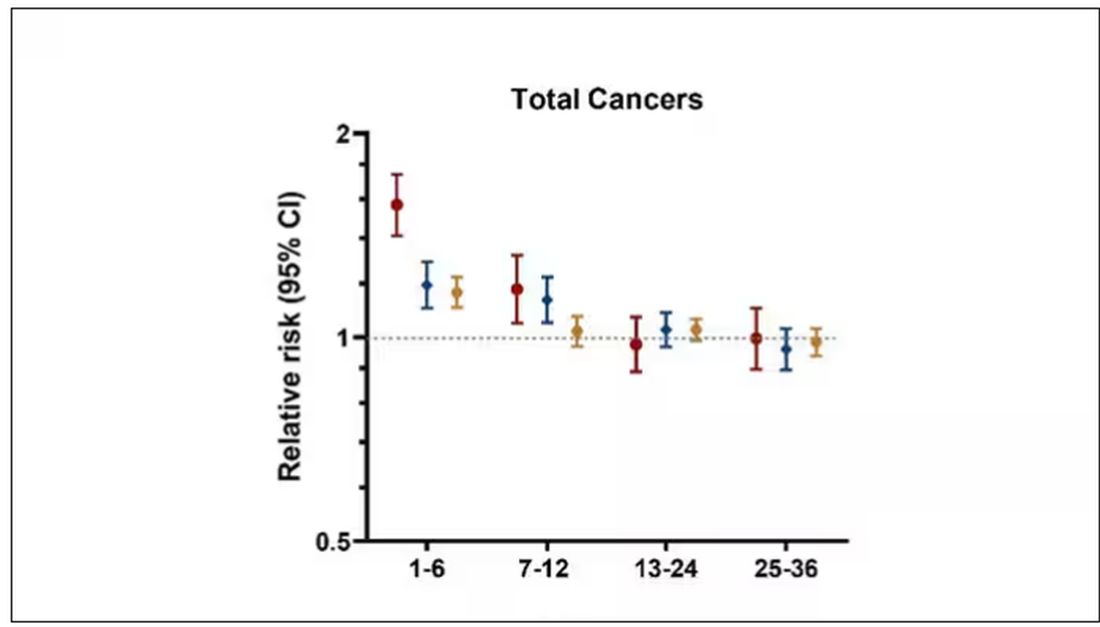

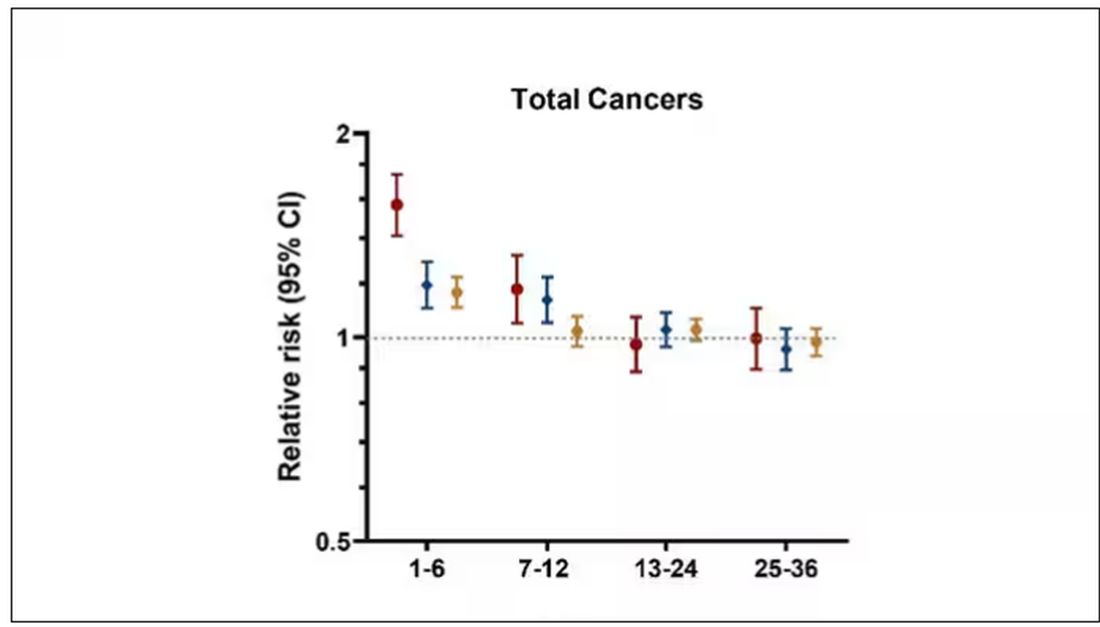

We also need to avoid suggesting that weight loss causes cancer. Some people lose weight because of an existing, as of yet undiagnosed cancer and its metabolic effects. This is borne out if you look at the risk of being diagnosed with cancer as you move further away from the interval of weight loss.

The further you get from the year of that 10% weight loss, the less likely you are to be diagnosed with cancer. Most of these cancers are diagnosed within a year of losing weight. In other words, if you’re reading this and getting worried that you lost weight 10 years ago, you’re probably out of the woods. That was, most likely, just you getting healthier.

Last thing: We have methods for weight loss now that are way more effective than diet or exercise. I’m looking at you, Ozempic. But aside from the weight loss wonder drugs, we have surgery and other interventions. This study did not capture any of that data. Ozempic wasn’t even on the market during this study, so we can’t say anything about the relationship between weight loss and cancer among people using nonlifestyle mechanisms to lose weight.

It’s a complicated system. But the clinically actionable point here is to notice if patients have lost weight. If they’ve lost it without trying, further workup is reasonable. If they’ve lost it but were trying to lose it, tell them “good job.” And consider a workup anyway.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As anyone who has been through medical training will tell you, some little scenes just stick with you. I had been seeing a patient in our resident clinic in West Philly for a couple of years. She was in her mid-60s with diabetes and hypertension and a distant smoking history. She was overweight and had been trying to improve her diet and lose weight since I started seeing her. One day she came in and was delighted to report that she had finally started shedding some pounds — about 15 in the past 2 months.

I enthusiastically told my preceptor that my careful dietary counseling had finally done the job. She looked through the chart for a moment and asked, “Is she up to date on her cancer screening?” A workup revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. The patient did well, actually, but the story stuck with me.

The textbooks call it “unintentional weight loss,” often in big, scary letters, and every doctor will go just a bit pale if a patient tells them that, despite efforts not to, they are losing weight. But true unintentional weight loss is not that common. After all, most of us are at least half-heartedly trying to lose weight all the time. Should doctors be worried when we are successful?

A new study suggests that perhaps they should. We’re talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, which combined participants from two long-running observational cohorts: 120,000 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, and 50,000 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. (These cohorts started in the 1970s and 1980s, so we’ll give them a pass on the gender-specific study designs.)

The rationale of enrolling healthcare providers in these cohort studies is that they would be reliable witnesses of their own health status. If a nurse or doctor says they have pancreatic cancer, it’s likely that they truly have pancreatic cancer. Detailed health surveys were distributed to the participants every other year, and the average follow-up was more than a decade.

Participants recorded their weight — as an aside, a nested study found that self-reported rate was extremely well correlated with professionally measured weight — and whether they had received a cancer diagnosis since the last survey.

This allowed researchers to look at the phenomenon described above. Would weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer? And, more interestingly, would intentional weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer.

I don’t think it will surprise you to hear that individuals in the highest category of weight loss, those who lost more than 10% of their body weight over a 2-year period, had a larger risk of being diagnosed with cancer in the next year. That’s the yellow line in this graph. In fact, they had about a 40% higher risk than those who did not lose weight.

Increased risk was found across multiple cancer types, though cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, not surprisingly, were most strongly associated with antecedent weight loss.

What about intentionality of weight loss? Unfortunately, the surveys did not ask participants whether they were trying to lose weight. Rather, the surveys asked about exercise and dietary habits. The researchers leveraged these responses to create three categories of participants: those who seemed to be trying to lose weight (defined as people who had increased their exercise and dietary quality); those who didn’t seem to be trying to lose weight (they changed neither exercise nor dietary behaviors); and a middle group, which changed one or the other of these behaviors but not both.

Let’s look at those who really seemed to be trying to lose weight. Over 2 years, they got more exercise and improved their diet.

If they succeeded in losing 10% or more of their body weight, they still had a higher risk for cancer than those who had not lost weight — about 30% higher, which is not that different from the 40% increased risk when you include those folks who weren’t changing their lifestyle.

This is why this study is important. The classic teaching is that unintentional weight loss is a bad thing and needs a workup. That’s fine. But we live in a world where perhaps the majority of people are, at any given time, trying to lose weight.

We need to be careful here. I am not by any means trying to say that people who have successfully lost weight have cancer. Both of the following statements can be true:

Significant weight loss, whether intentional or not, is associated with a higher risk for cancer.

Most people with significant weight loss will not have cancer.

Both of these can be true because cancer is, fortunately, rare. Of people who lose weight, the vast majority will lose weight because they are engaging in healthier behaviors. A small number may lose weight because something else is wrong. It’s just hard to tell the two apart.

Out of the nearly 200,000 people in this study, only around 16,000 developed cancer during follow-up. Again, although the chance of having cancer is slightly higher if someone has experienced weight loss, the chance is still very low.

We also need to avoid suggesting that weight loss causes cancer. Some people lose weight because of an existing, as of yet undiagnosed cancer and its metabolic effects. This is borne out if you look at the risk of being diagnosed with cancer as you move further away from the interval of weight loss.

The further you get from the year of that 10% weight loss, the less likely you are to be diagnosed with cancer. Most of these cancers are diagnosed within a year of losing weight. In other words, if you’re reading this and getting worried that you lost weight 10 years ago, you’re probably out of the woods. That was, most likely, just you getting healthier.

Last thing: We have methods for weight loss now that are way more effective than diet or exercise. I’m looking at you, Ozempic. But aside from the weight loss wonder drugs, we have surgery and other interventions. This study did not capture any of that data. Ozempic wasn’t even on the market during this study, so we can’t say anything about the relationship between weight loss and cancer among people using nonlifestyle mechanisms to lose weight.

It’s a complicated system. But the clinically actionable point here is to notice if patients have lost weight. If they’ve lost it without trying, further workup is reasonable. If they’ve lost it but were trying to lose it, tell them “good job.” And consider a workup anyway.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As anyone who has been through medical training will tell you, some little scenes just stick with you. I had been seeing a patient in our resident clinic in West Philly for a couple of years. She was in her mid-60s with diabetes and hypertension and a distant smoking history. She was overweight and had been trying to improve her diet and lose weight since I started seeing her. One day she came in and was delighted to report that she had finally started shedding some pounds — about 15 in the past 2 months.

I enthusiastically told my preceptor that my careful dietary counseling had finally done the job. She looked through the chart for a moment and asked, “Is she up to date on her cancer screening?” A workup revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. The patient did well, actually, but the story stuck with me.

The textbooks call it “unintentional weight loss,” often in big, scary letters, and every doctor will go just a bit pale if a patient tells them that, despite efforts not to, they are losing weight. But true unintentional weight loss is not that common. After all, most of us are at least half-heartedly trying to lose weight all the time. Should doctors be worried when we are successful?

A new study suggests that perhaps they should. We’re talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, which combined participants from two long-running observational cohorts: 120,000 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, and 50,000 men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. (These cohorts started in the 1970s and 1980s, so we’ll give them a pass on the gender-specific study designs.)

The rationale of enrolling healthcare providers in these cohort studies is that they would be reliable witnesses of their own health status. If a nurse or doctor says they have pancreatic cancer, it’s likely that they truly have pancreatic cancer. Detailed health surveys were distributed to the participants every other year, and the average follow-up was more than a decade.

Participants recorded their weight — as an aside, a nested study found that self-reported rate was extremely well correlated with professionally measured weight — and whether they had received a cancer diagnosis since the last survey.

This allowed researchers to look at the phenomenon described above. Would weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer? And, more interestingly, would intentional weight loss precede a new diagnosis of cancer.

I don’t think it will surprise you to hear that individuals in the highest category of weight loss, those who lost more than 10% of their body weight over a 2-year period, had a larger risk of being diagnosed with cancer in the next year. That’s the yellow line in this graph. In fact, they had about a 40% higher risk than those who did not lose weight.

Increased risk was found across multiple cancer types, though cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, not surprisingly, were most strongly associated with antecedent weight loss.

What about intentionality of weight loss? Unfortunately, the surveys did not ask participants whether they were trying to lose weight. Rather, the surveys asked about exercise and dietary habits. The researchers leveraged these responses to create three categories of participants: those who seemed to be trying to lose weight (defined as people who had increased their exercise and dietary quality); those who didn’t seem to be trying to lose weight (they changed neither exercise nor dietary behaviors); and a middle group, which changed one or the other of these behaviors but not both.

Let’s look at those who really seemed to be trying to lose weight. Over 2 years, they got more exercise and improved their diet.

If they succeeded in losing 10% or more of their body weight, they still had a higher risk for cancer than those who had not lost weight — about 30% higher, which is not that different from the 40% increased risk when you include those folks who weren’t changing their lifestyle.

This is why this study is important. The classic teaching is that unintentional weight loss is a bad thing and needs a workup. That’s fine. But we live in a world where perhaps the majority of people are, at any given time, trying to lose weight.

We need to be careful here. I am not by any means trying to say that people who have successfully lost weight have cancer. Both of the following statements can be true:

Significant weight loss, whether intentional or not, is associated with a higher risk for cancer.

Most people with significant weight loss will not have cancer.

Both of these can be true because cancer is, fortunately, rare. Of people who lose weight, the vast majority will lose weight because they are engaging in healthier behaviors. A small number may lose weight because something else is wrong. It’s just hard to tell the two apart.

Out of the nearly 200,000 people in this study, only around 16,000 developed cancer during follow-up. Again, although the chance of having cancer is slightly higher if someone has experienced weight loss, the chance is still very low.

We also need to avoid suggesting that weight loss causes cancer. Some people lose weight because of an existing, as of yet undiagnosed cancer and its metabolic effects. This is borne out if you look at the risk of being diagnosed with cancer as you move further away from the interval of weight loss.

The further you get from the year of that 10% weight loss, the less likely you are to be diagnosed with cancer. Most of these cancers are diagnosed within a year of losing weight. In other words, if you’re reading this and getting worried that you lost weight 10 years ago, you’re probably out of the woods. That was, most likely, just you getting healthier.

Last thing: We have methods for weight loss now that are way more effective than diet or exercise. I’m looking at you, Ozempic. But aside from the weight loss wonder drugs, we have surgery and other interventions. This study did not capture any of that data. Ozempic wasn’t even on the market during this study, so we can’t say anything about the relationship between weight loss and cancer among people using nonlifestyle mechanisms to lose weight.

It’s a complicated system. But the clinically actionable point here is to notice if patients have lost weight. If they’ve lost it without trying, further workup is reasonable. If they’ve lost it but were trying to lose it, tell them “good job.” And consider a workup anyway.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Corticosteroid Injections Don’t Move Blood Sugar for Most

TOPLINE:

Intra-articular corticosteroid (IACS) injections pose a minimal risk of accelerating diabetes for most people, despite temporarily elevating blood glucose levels, according to a study published in Clinical Diabetes.

METHODOLOGY:

- Almost half of Americans with diabetes have arthritis, so glycemic control is a concern for many receiving IACS injections.

- IACS injections are known to cause short-term hyperglycemia, but their long-term effects on glycemic control are not well studied.

- For the retrospective cohort study, researchers at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, used electronic health records from 1169 adults who had received an IACS injection in one large joint between 2012 and 2018.

- They analyzed data on A1C levels for study participants from 18 months before and after the injections.

- Researchers assessed if participants had a greater-than-expected (defined as an increase of more than 0.5% above expected) concentration of A1C after the injection, and examined rates of diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome in the 30 days following an injection.

TAKEAWAY:

- Nearly 16% of people experienced a greater-than-expected A1C level after receiving an injection.

- A1C levels rose by an average of 1.2% in the greater-than-expected group, but decreased by an average of 0.2% in the average group.

- One patient had an episode of severe hyperglycemia that was linked to the injection.

- A baseline level of A1C above 8% was the only factor associated with a greater-than-expected increase in the marker after an IACS injection.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although most patients do not experience an increase in A1C after IACS, clinicians should counsel patients with suboptimally controlled diabetes about risks of further hyperglycemia after IACS administration,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Terin T. Sytsma, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and could not establish causation. In addition, the population was of residents from one county in Minnesota, and was not racially or ethnically diverse. Details about the injection, such as location and total dose, were not available. The study also did not include a control group.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Mayo Clinic and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Intra-articular corticosteroid (IACS) injections pose a minimal risk of accelerating diabetes for most people, despite temporarily elevating blood glucose levels, according to a study published in Clinical Diabetes.

METHODOLOGY:

- Almost half of Americans with diabetes have arthritis, so glycemic control is a concern for many receiving IACS injections.

- IACS injections are known to cause short-term hyperglycemia, but their long-term effects on glycemic control are not well studied.

- For the retrospective cohort study, researchers at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, used electronic health records from 1169 adults who had received an IACS injection in one large joint between 2012 and 2018.

- They analyzed data on A1C levels for study participants from 18 months before and after the injections.

- Researchers assessed if participants had a greater-than-expected (defined as an increase of more than 0.5% above expected) concentration of A1C after the injection, and examined rates of diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome in the 30 days following an injection.

TAKEAWAY:

- Nearly 16% of people experienced a greater-than-expected A1C level after receiving an injection.

- A1C levels rose by an average of 1.2% in the greater-than-expected group, but decreased by an average of 0.2% in the average group.

- One patient had an episode of severe hyperglycemia that was linked to the injection.

- A baseline level of A1C above 8% was the only factor associated with a greater-than-expected increase in the marker after an IACS injection.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although most patients do not experience an increase in A1C after IACS, clinicians should counsel patients with suboptimally controlled diabetes about risks of further hyperglycemia after IACS administration,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Terin T. Sytsma, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and could not establish causation. In addition, the population was of residents from one county in Minnesota, and was not racially or ethnically diverse. Details about the injection, such as location and total dose, were not available. The study also did not include a control group.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Mayo Clinic and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Intra-articular corticosteroid (IACS) injections pose a minimal risk of accelerating diabetes for most people, despite temporarily elevating blood glucose levels, according to a study published in Clinical Diabetes.

METHODOLOGY:

- Almost half of Americans with diabetes have arthritis, so glycemic control is a concern for many receiving IACS injections.

- IACS injections are known to cause short-term hyperglycemia, but their long-term effects on glycemic control are not well studied.

- For the retrospective cohort study, researchers at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, used electronic health records from 1169 adults who had received an IACS injection in one large joint between 2012 and 2018.

- They analyzed data on A1C levels for study participants from 18 months before and after the injections.

- Researchers assessed if participants had a greater-than-expected (defined as an increase of more than 0.5% above expected) concentration of A1C after the injection, and examined rates of diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome in the 30 days following an injection.

TAKEAWAY:

- Nearly 16% of people experienced a greater-than-expected A1C level after receiving an injection.

- A1C levels rose by an average of 1.2% in the greater-than-expected group, but decreased by an average of 0.2% in the average group.

- One patient had an episode of severe hyperglycemia that was linked to the injection.

- A baseline level of A1C above 8% was the only factor associated with a greater-than-expected increase in the marker after an IACS injection.

IN PRACTICE:

“Although most patients do not experience an increase in A1C after IACS, clinicians should counsel patients with suboptimally controlled diabetes about risks of further hyperglycemia after IACS administration,” the researchers wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Terin T. Sytsma, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was retrospective and could not establish causation. In addition, the population was of residents from one county in Minnesota, and was not racially or ethnically diverse. Details about the injection, such as location and total dose, were not available. The study also did not include a control group.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Mayo Clinic and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hypocalcemia Risk Warning Added to Osteoporosis Drug

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has added a boxed warning to the label of the osteoporosis drug denosumab (Prolia) about increased risk for severe hypocalcemia in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody, indicated for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who are at increased risk for fracture for whom other treatments aren’t effective or can’t be tolerated. It’s also indicated to increase bone mass in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture, treat glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in men and women at high risk for fracture, increase bone mass in men at high risk for fracture receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for nonmetastatic prostate cancer, and increase bone mass in women at high risk for fracture receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer.

This new warning updates a November 2022 alert based on preliminary evidence for a “substantial risk” for hypocalcemia in patients with CKD on dialysis.

Upon further examination of the data from two trials including more than 500,000 denosumab-treated women with CKD, the FDA concluded that severe hypocalcemia appears to be more common in those with CKD who also have mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). And, for patients with advanced CKD taking denosumab, “severe hypocalcemia resulted in serious harm, including hospitalization, life-threatening events, and death.”

Most of the severe hypocalcemia events occurred 2-10 weeks after denosumab injection, with the greatest risk during weeks 2-5.

The new warning advises healthcare professionals to assess patients’ kidney function before prescribing denosumab, and for those with advanced CKD, “consider the risk of severe hypocalcemia with Prolia in the context of other available treatments for osteoporosis.”

If the drug is still being considered for those patients for initial or continued use, calcium blood levels should be checked, and patients should be evaluated for CKD-MBD. Prior to prescribing denosumab in these patients, CKD-MBD should be properly managed, hypocalcemia corrected, and patients supplemented with calcium and activated vitamin D to decrease the risk for severe hypocalcemia and associated complications.

“Treatment with denosumab in patients with advanced CKD, including those on dialysis, and particularly patients with diagnosed CKD-MBD should involve a health care provider with expertise in the diagnosis and management of CKD-MBD,” the FDA advises.

Once denosumab is administered, close monitoring of blood calcium levels and prompt hypocalcemia management is essential to prevent complications including seizures or arrythmias. Patients should be advised to promptly report symptoms that could be consistent with hypocalcemia, including confusion, seizures, irregular heartbeat, fainting, muscle spasms or weakness, face twitching, tingling, or numbness anywhere in the body.

In 2022, an estimated 2.2 million Prolia prefilled syringes were sold by the manufacturer to US healthcare settings.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has added a boxed warning to the label of the osteoporosis drug denosumab (Prolia) about increased risk for severe hypocalcemia in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody, indicated for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who are at increased risk for fracture for whom other treatments aren’t effective or can’t be tolerated. It’s also indicated to increase bone mass in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture, treat glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in men and women at high risk for fracture, increase bone mass in men at high risk for fracture receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for nonmetastatic prostate cancer, and increase bone mass in women at high risk for fracture receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer.

This new warning updates a November 2022 alert based on preliminary evidence for a “substantial risk” for hypocalcemia in patients with CKD on dialysis.

Upon further examination of the data from two trials including more than 500,000 denosumab-treated women with CKD, the FDA concluded that severe hypocalcemia appears to be more common in those with CKD who also have mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). And, for patients with advanced CKD taking denosumab, “severe hypocalcemia resulted in serious harm, including hospitalization, life-threatening events, and death.”

Most of the severe hypocalcemia events occurred 2-10 weeks after denosumab injection, with the greatest risk during weeks 2-5.

The new warning advises healthcare professionals to assess patients’ kidney function before prescribing denosumab, and for those with advanced CKD, “consider the risk of severe hypocalcemia with Prolia in the context of other available treatments for osteoporosis.”

If the drug is still being considered for those patients for initial or continued use, calcium blood levels should be checked, and patients should be evaluated for CKD-MBD. Prior to prescribing denosumab in these patients, CKD-MBD should be properly managed, hypocalcemia corrected, and patients supplemented with calcium and activated vitamin D to decrease the risk for severe hypocalcemia and associated complications.

“Treatment with denosumab in patients with advanced CKD, including those on dialysis, and particularly patients with diagnosed CKD-MBD should involve a health care provider with expertise in the diagnosis and management of CKD-MBD,” the FDA advises.

Once denosumab is administered, close monitoring of blood calcium levels and prompt hypocalcemia management is essential to prevent complications including seizures or arrythmias. Patients should be advised to promptly report symptoms that could be consistent with hypocalcemia, including confusion, seizures, irregular heartbeat, fainting, muscle spasms or weakness, face twitching, tingling, or numbness anywhere in the body.

In 2022, an estimated 2.2 million Prolia prefilled syringes were sold by the manufacturer to US healthcare settings.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has added a boxed warning to the label of the osteoporosis drug denosumab (Prolia) about increased risk for severe hypocalcemia in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody, indicated for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who are at increased risk for fracture for whom other treatments aren’t effective or can’t be tolerated. It’s also indicated to increase bone mass in men with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture, treat glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in men and women at high risk for fracture, increase bone mass in men at high risk for fracture receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for nonmetastatic prostate cancer, and increase bone mass in women at high risk for fracture receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy for breast cancer.

This new warning updates a November 2022 alert based on preliminary evidence for a “substantial risk” for hypocalcemia in patients with CKD on dialysis.

Upon further examination of the data from two trials including more than 500,000 denosumab-treated women with CKD, the FDA concluded that severe hypocalcemia appears to be more common in those with CKD who also have mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). And, for patients with advanced CKD taking denosumab, “severe hypocalcemia resulted in serious harm, including hospitalization, life-threatening events, and death.”

Most of the severe hypocalcemia events occurred 2-10 weeks after denosumab injection, with the greatest risk during weeks 2-5.

The new warning advises healthcare professionals to assess patients’ kidney function before prescribing denosumab, and for those with advanced CKD, “consider the risk of severe hypocalcemia with Prolia in the context of other available treatments for osteoporosis.”

If the drug is still being considered for those patients for initial or continued use, calcium blood levels should be checked, and patients should be evaluated for CKD-MBD. Prior to prescribing denosumab in these patients, CKD-MBD should be properly managed, hypocalcemia corrected, and patients supplemented with calcium and activated vitamin D to decrease the risk for severe hypocalcemia and associated complications.

“Treatment with denosumab in patients with advanced CKD, including those on dialysis, and particularly patients with diagnosed CKD-MBD should involve a health care provider with expertise in the diagnosis and management of CKD-MBD,” the FDA advises.

Once denosumab is administered, close monitoring of blood calcium levels and prompt hypocalcemia management is essential to prevent complications including seizures or arrythmias. Patients should be advised to promptly report symptoms that could be consistent with hypocalcemia, including confusion, seizures, irregular heartbeat, fainting, muscle spasms or weakness, face twitching, tingling, or numbness anywhere in the body.

In 2022, an estimated 2.2 million Prolia prefilled syringes were sold by the manufacturer to US healthcare settings.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A Look at the Evidence Linking Diet to Skin Conditions

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — Amid all the hype, claims, and confusion, there is evidence linking some foods and drinks to an increased risk for acne, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, rosacea, and other common skin conditions. So, what is the connection in each case? And how can people with any of these skin conditions potentially improve their health and quality of life with dietary changes?

What is clear is that there has been an explosion of interest in learning which foods can improve or worsen skin issues in recent years. It’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with the research and also to Google ‘diet’ and ‘skin’, said Vivian Shi, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock. “As practitioners, we should be well prepared to talk about what patients want to talk about.”

Acne

One of the major areas of interest is diet and acne. “We’ve all heard sugar and dairy are bad, and the Western diet is high in sugar and dairy,” Dr. Shi said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference.

Dairy, red meat, and carbohydrates can break down into leucine, an essential amino acid found in protein. Leucine and sugar together, in turn, can produce insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which, through different pathways, can reach the androgen receptors throughout the body, including the skin. This results in sebogenesis, lipogenesis, and keratinization, which triggers follicular inflammation and results in more of the acne-causing bacteria Cutibacterium acnes.

Milk and other dairy products also can increase IGF-1 levels, which can alter hormonal mediators and increase acne.

Not all types of dairy milk are created equal, however, when it comes to acne. Dr. Shi wondered why 2% milk has overall color and nutritional content very similar to that of whole milk. “I looked into this.” She discovered that when milk manufacturers remove the fat, they often add whey proteins to restore some nutrients. Whey protein can increase acne, Dr. Shi added.

“So, if you’re going to choose any milk to drink, I think from an acne perspective, it’s better to use whole milk. If you can get it organic, even better.” Skim milk is the most acnegenic, she said.

Psoriasis

A systematic review of 55 studies evaluating diet and psoriasis found obesity can be an exacerbating factor. The strongest evidence for dietary weight reduction points to a hypocaloric diet in people with overweight or obesity, according to the review. Other evidence suggests alcohol can lower response to treatment and is linked with more severe psoriasis. Furthermore, a gluten-free diet or vitamin D supplements can help some subpopulations of people with psoriasis.

“An overwhelming majority of our psoriasis patients are vitamin D deficient,” Dr. Shi said.

The National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) publishes dietary modification guidelines, updated as recently as November 2023. The NPF states that “there is no diet that will cure psoriatic disease, but there are many ways in which eating healthful food may lessen the severity of symptoms and play a role in lowering the likelihood of developing comorbidities.”

Healthier choices include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fat-free or low-fat dairy products. Include lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, eggs, and nuts. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet has been linked to a lower severity of psoriasis.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is “one of the prototypical diseases related to diet,” Dr. Shi said. A different meta-analysis looked at randomized controlled trials of synbiotics (a combination of prebiotics and probiotics) for treatment of AD.

These researchers found that synbiotics do not prevent AD, but they can help treat it in adults and children older than 1 year. In addition, synbiotics are more beneficial than probiotics in treating the condition, although there are no head-to-head comparison studies. In addition, the meta-analysis found that prebiotics alone can lower AD severity.

However, Dr. Shi said, there are no recommendations from the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) on prebiotics or probiotics for AD, and the AAD does not recommend any supplement or essential oil for AD.

In a 2022 review, investigators ranked the efficacy of different supplements for AD based on available evidence. They found the greatest benefit associated with vitamin D supplementation, followed by vitamin E, probiotics, hemp seed oil, histidine, and oolong tea. They also noted the ‘Six Food Elimination Diet and Autoimmune Protocol’ featured the least amount of evidence to back it up.

Rosacea

Rosacea appears to be caused by “all the fun things in life” like sunlight, alcohol, chocolate, spicy foods, and caffeine, Dr. Shi said. In people with rosacea, they can cause facial flushing, edema, burning, and an inflammatory response.

Certain foods can activate skin receptors and sensory neurons, which can release neuropeptides that act on mast cells in blood that lead to flushing. The skin-gut axis may also be involved, evidence suggests. “And that is why food has a pretty profound impact on rosacea,” Dr. Shi said.

Dr. Shi reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

ORLANDO, FLORIDA — Amid all the hype, claims, and confusion, there is evidence linking some foods and drinks to an increased risk for acne, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, rosacea, and other common skin conditions. So, what is the connection in each case? And how can people with any of these skin conditions potentially improve their health and quality of life with dietary changes?

What is clear is that there has been an explosion of interest in learning which foods can improve or worsen skin issues in recent years. It’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with the research and also to Google ‘diet’ and ‘skin’, said Vivian Shi, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock. “As practitioners, we should be well prepared to talk about what patients want to talk about.”

Acne

One of the major areas of interest is diet and acne. “We’ve all heard sugar and dairy are bad, and the Western diet is high in sugar and dairy,” Dr. Shi said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference.

Dairy, red meat, and carbohydrates can break down into leucine, an essential amino acid found in protein. Leucine and sugar together, in turn, can produce insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which, through different pathways, can reach the androgen receptors throughout the body, including the skin. This results in sebogenesis, lipogenesis, and keratinization, which triggers follicular inflammation and results in more of the acne-causing bacteria Cutibacterium acnes.

Milk and other dairy products also can increase IGF-1 levels, which can alter hormonal mediators and increase acne.

Not all types of dairy milk are created equal, however, when it comes to acne. Dr. Shi wondered why 2% milk has overall color and nutritional content very similar to that of whole milk. “I looked into this.” She discovered that when milk manufacturers remove the fat, they often add whey proteins to restore some nutrients. Whey protein can increase acne, Dr. Shi added.

“So, if you’re going to choose any milk to drink, I think from an acne perspective, it’s better to use whole milk. If you can get it organic, even better.” Skim milk is the most acnegenic, she said.

Psoriasis