User login

For MD-IQ use only

For Richer, for Poorer: Low-Carb Diets Work for All Incomes

For 3 years, Ajala Efem’s type 2 diabetes was so poorly controlled that her blood sugar often soared northward of 500 mg/dL despite insulin shots three to five times a day. She would experience dizziness, vomiting, severe headaches, and the neuropathy in her feet made walking painful. She was also — literally — frothing at the mouth. The 47-year-old single mother of two adult children with mental disabilities feared that she would die.

Ms. Efem lives in the South Bronx, which is among the poorest areas of New York City, where the combined rate of prediabetes and diabetes is close to 30%, the highest rate of any borough in the city.

She had to wait 8 months for an appointment with an endocrinologist, but that visit proved to be life-changing. She lost 28 pounds and got off 15 medications in a single month. She did not join a gym or count calories; she simply changed the food she ate and adopted a low-carb diet.

“I went from being sick to feeling so great,” she told her endocrinologist recently: “My feet aren’t hurting; I’m not in pain; I’m eating as much as I want, and I really enjoy my food so much.”

Ms. Efem’s life-changing visit was with Mariela Glandt, MD, at the offices of Essen Health Care. One month earlier, Dr. Glandt’s company, OwnaHealth, was contracted by Essen to conduct a 100-person pilot program for endocrinology patients. Essen is the largest Medicaid provider in New York City, and “they were desperate for an endocrinologist,” said Dr. Glandt, who trained at Columbia University in New York. So she came — all the way from Madrid, Spain. She commutes monthly, staying for a week each visit.

Dr. Glandt keeps up this punishing schedule because, as she explains, “it’s such a high for me to see these incredible transformations.” Her mostly Black and Hispanic patients are poor and lack resources, yet they lose significant amounts of weight, and their health issues resolve.

“Food is medicine” is an idea very much in vogue. The concept was central to the landmark White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health in 2022 and is now the focus of a number of a wide range of government programs. Recently, the Senate held a hearing aimed at further expanding food as medicine programs.

Still, only a single randomized controlled clinical trial has been conducted on this nutritional approach, with unexpectedly disappointing results. In the mid-Atlantic region, 456 food-insecure adults with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to usual care or the provision of weekly groceries for their entire families for about 1 year. Provisions for a Mediterranean-style diet included whole grains, fruits and vegetables, lean protein, low-fat dairy products, cereal, brown rice, and bread. In addition, participants received dietary consultations. Yet, those who got free food and coaching did not see improvements in their average blood sugar (the study’s primary outcome), and their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels appeared to have worsened.

“To be honest, I was surprised,” the study’s lead author, Joseph Doyle, PhD, professor at the Sloan School of Management at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told me. “I was hoping we would show improved outcomes, but the way to make progress is to do well-randomized trials to find out what works.”

I was not surprised by these results because a recent rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis in The BMJ did not show a Mediterranean-style diet to be the most effective for glycemic control. And Ms. Efem was not in fact following a Mediterranean-style diet.

Ms. Efem’s low-carb success story is anecdotal, but Dr. Glandt has an established track record from her 9 years’ experience as the medical director of the eponymous diabetes center she founded in Tel Aviv. A recent audit of 344 patients from the center found that after 6 months of following a very low–carbohydrate diet, 96.3% of those with diabetes saw their A1c fall from a median 7.6% to 6.3%. Weight loss was significant, with a median drop of 6.5 kg (14 pounds) for patients with diabetes and 5.7 kg for those with prediabetes. The diet comprises 5%-10% of calories from carbs, but Dr. Glandt does not use numeric targets with her patients.

Blood pressure, triglycerides, and liver enzymes also improved. And though LDL cholesterol went up by 8%, this result may have been offset by an accompanying 13% rise in HDL cholesterol. Of the 78 patients initially on insulin, 62 were able to stop this medication entirely.

Although these results aren’t from a clinical trial, they’re still highly meaningful because the current dietary standard of care for type 2 diabetes can only slow the progression of the disease, not cause remission. Indeed, the idea that type 2 diabetes could be put into remission was not seriously considered by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) until 2009. By 2019, an ADA report concluded that “[r]educing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated the most evidence for improving glycemia.” In other words, the best way to improve the key factor in diabetes is to reduce total carbohydrates. Yet, the ADA still advocates filling one quarter of one’s plate with carbohydrate-based foods, an amount that will prevent remission. Given that the ADA’s vision statement is “a life free of diabetes,” it seems negligent not to tell people with a deadly condition that they can reverse this diagnosis.

A 2023 meta-analysis of 42 controlled clinical trials on 4809 patients showed that a very low–carbohydrate ketogenic diet (keto) was “superior” to alternatives for glycemic control. A more recent review of 11 clinical trials found that this diet was equal but not superior to other nutritional approaches in terms of blood sugar control, but this review also concluded that keto led to greater increases in HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides.

Dr. Glandt’s patients in the Bronx might not seem like obvious low-carb candidates. The diet is considered expensive and difficult to sustain. My interviews with a half dozen patients revealed some of these difficulties, but even for a woman living in a homeless shelter, the obstacles are not insurmountable.

Jerrilyn, who preferred that I use only her first name, lives in a shelter in Queens. While we strolled through a nearby park, she told me about her desire to lose weight and recover from polycystic ovary syndrome, which terrified her because it had caused dramatic hair loss. When she landed in Dr. Glandt’s office at age 28, she weighed 180 pounds.

Less than 5 months later, Jerrilyn had lost 25 pounds, and her period had returned with some regularity. She said she used “food stamps,” known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to buy most of her food at local delis because the meals served at the shelter were too heavy in starches. She starts her day with eggs, turkey bacon, and avocado.

“It was hard to give up carbohydrates because in my culture [Latina], we have nothing but carbs: rice, potatoes, yuca,” Jerrilyn shared. She noticed that carbs make her hungrier, but after 3 days of going low-carb, her cravings diminished. “It was like getting over an addiction,” she said.

Jerrilyn told me she’d seen many doctors but none as involved as Dr. Glandt. “It feels awesome to know that I have a lot of really useful information coming from her all the time.” The OwnaHealth app tracks weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, ketones, meals, mood, and cravings. Patients wear continuous glucose monitors and enter other information manually. Ketone bodies are used to measure dietary adherence and are obtained through finger pricks and test strips provided by OwnaHealth. Dr. Glandt gives patients her own food plan, along with free visual guides to low-carbohydrate foods by dietdoctor.com.

Dr. Glandt also sends her patients for regular blood work. She says she does not frequently see a rise in LDL cholesterol, which can sometimes occur on a low-carbohydrate diet. This effect is most common among people who are lean and fit. She says she doesn’t discontinue statins unless cholesterol levels improve significantly.

Samuel Gonzalez, age 56, weighed 275 pounds when he walked into Dr. Glandt’s office this past November. His A1c was 9.2%, but none of his previous doctors had diagnosed him with diabetes. “I was like a walking bag of sugar!” he joked.

A low-carbohydrate diet seemed absurd to a Puerto Rican like himself: “Having coffee without sugar? That’s like sacrilegious in my culture!” exclaimed Mr. Gonzalez. Still, he managed, with SNAP, to cook eggs and bacon for breakfast and some kind of protein for dinner. He keeps lunch light, “like tuna fish,” and finds checking in with the OwnaHealth app to be very helpful. “Every day, I’m on it,” he said. In the past 7 months, he’s lost 50 pounds, normalized his cholesterol and blood pressure levels, and lowered his A1c to 5.5%.

Mr. Gonzalez gets disability payments due to a back injury, and Ms. Efem receives government payments because her husband died serving in the military. Ms. Efem says her new diet challenges her budget, but Mr. Gonzalez says he manages easily.

Mélissa Cruz, a 28-year-old studying to be a nail technician while also doing back office work at a physical therapy practice, says she’s stretched thin. “I end up sad because I can’t put energy into looking up recipes and cooking for me and my boyfriend,” she told me. She’ll often cook rice and plantains for him and meat for herself, but “it’s frustrating when I’m low on funds and can’t figure out what to eat.”

Low-carbohydrate diets have a reputation for being expensive because people often start eating pricier foods, like meat and cheese, to replace cheaper starchy foods such as pasta and rice.

A 2019 cost analysis published in Nutrition & Dietetics compared a low-carbohydrate dietary pattern with the New Zealand government’s recommended guidelines (which are almost identical to those in the United States) and found that it cost only an extra $1.27 in US dollars per person per day. One explanation is that protein and fat are more satiating than carbohydrates, so people who mostly consume these macronutrients often cut back on snacks like packaged chips, crackers, and even fruits. Also, those on a ketogenic diet usually cut down on medications, so the additional $1.27 daily is likely offset by reduced spending at the pharmacy.

It’s not just Bronx residents with low socioeconomic status (SES) who adapt well to low-carbohydrate diets. Among Alabama state employees with diabetes enrolled in a low-carbohydrate dietary program provided by a company called Virta, the low SES population had the best outcomes. Virta also published survey data in 2023 showing that participants in a program with the Veteran’s Administration did not find additional costs to be an obstacle to dietary adherence. In fact, some participants saw cost reductions due to decreased spending on processed snacks and fast foods.

Ms. Cruz told me she struggles financially, yet she’s still lost nearly 30 pounds in 5 months, and her A1c went from 7.1% down to 5.9%, putting her diabetes into remission. Equally motivating for her are the improvements she’s seen in other hormonal issues. Since childhood, she’s had acanthosis, a condition that causes the skin to darken in velvety patches, and more recently, she developed severe hirsutism to the point of growing sideburns. “I had tried going vegan and fasting, but these just weren’t sustainable for me, and I was so overwhelmed with counting calories all the time.” Now, on a low-carbohydrate diet, which doesn’t require calorie counting, she’s finally seeing both these conditions improve significantly.

When I last checked in with Ms. Cruz, she said she had “kind of ghosted” Dr. Glandt due to her work and school constraints, but she hadn’t abandoned the diet. She appreciated, too, that Dr. Glandt had not given up on her and kept calling and messaging. “She’s not at all like a typical doctor who would just tell me to lose weight and shake their head at me,” Ms. Cruz said.

Because Dr. Glandt’s approach is time-intensive and high-touch, it might seem impractical to scale up, but Dr. Glandt’s app uses artificial intelligence to help with communications thus allowing her, with help from part-time health coaches, to care for patients.

This early success in one of the United States’ poorest and sickest neighborhoods should give us hope that type 2 diabetes need not to be a progressive irreversible disease, even among the disadvantaged.

OwnaHealth’s track record, along with that of Virta and other similar low-carbohydrate medical practices also give hope to the food-is-medicine idea. Diabetes can go into remission, and people can be healed, provided that health practitioners prescribe the right foods. And in truth, it’s not a diet. It’s a way of eating that must be maintained. The sustainability of low-carbohydrate diets has been a point of contention, but the Virta trial, with 38% of patients sustaining remission at 2 years, showed that it’s possible. (OwnaHealth, for its part, offers long-term maintenance plans to help patients stay very low-carb permanently.)

Given the tremendous costs and health burden of diabetes, this approach should no doubt be the first line of treatment for doctors and the ADA. The past two decades of clinical trial research have demonstrated that remission of type 2 diabetes is possible through diet alone. It turns out that for metabolic diseases, only certain foods are truly medicine.

Tools and Tips for Clinicians:

- Free two-page keto starter’s guide by OwnaHealth; Dr. Glandt uses this guide with her patients.

- Illustrated low-carb guides by dietdoctor.com

- Free low-carbohydrate starter guide by the Michigan Collaborative for Type 2 Diabetes

- Low-Carb for Any Budget, a free digital booklet by Mark Cucuzzella, MD, and Kristie Sullivan, PhD

- Recipe and meal ideas from Ruled.me, Keto-Mojo.com, and

Dr. Teicholz is the founder of Nutrition Coalition, an independent nonprofit dedicated to ensuring that US dietary guidelines align with current science. She disclosed receiving book royalties from The Big Fat Surprise, and received honorarium not exceeding $2000 for speeches from various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For 3 years, Ajala Efem’s type 2 diabetes was so poorly controlled that her blood sugar often soared northward of 500 mg/dL despite insulin shots three to five times a day. She would experience dizziness, vomiting, severe headaches, and the neuropathy in her feet made walking painful. She was also — literally — frothing at the mouth. The 47-year-old single mother of two adult children with mental disabilities feared that she would die.

Ms. Efem lives in the South Bronx, which is among the poorest areas of New York City, where the combined rate of prediabetes and diabetes is close to 30%, the highest rate of any borough in the city.

She had to wait 8 months for an appointment with an endocrinologist, but that visit proved to be life-changing. She lost 28 pounds and got off 15 medications in a single month. She did not join a gym or count calories; she simply changed the food she ate and adopted a low-carb diet.

“I went from being sick to feeling so great,” she told her endocrinologist recently: “My feet aren’t hurting; I’m not in pain; I’m eating as much as I want, and I really enjoy my food so much.”

Ms. Efem’s life-changing visit was with Mariela Glandt, MD, at the offices of Essen Health Care. One month earlier, Dr. Glandt’s company, OwnaHealth, was contracted by Essen to conduct a 100-person pilot program for endocrinology patients. Essen is the largest Medicaid provider in New York City, and “they were desperate for an endocrinologist,” said Dr. Glandt, who trained at Columbia University in New York. So she came — all the way from Madrid, Spain. She commutes monthly, staying for a week each visit.

Dr. Glandt keeps up this punishing schedule because, as she explains, “it’s such a high for me to see these incredible transformations.” Her mostly Black and Hispanic patients are poor and lack resources, yet they lose significant amounts of weight, and their health issues resolve.

“Food is medicine” is an idea very much in vogue. The concept was central to the landmark White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health in 2022 and is now the focus of a number of a wide range of government programs. Recently, the Senate held a hearing aimed at further expanding food as medicine programs.

Still, only a single randomized controlled clinical trial has been conducted on this nutritional approach, with unexpectedly disappointing results. In the mid-Atlantic region, 456 food-insecure adults with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to usual care or the provision of weekly groceries for their entire families for about 1 year. Provisions for a Mediterranean-style diet included whole grains, fruits and vegetables, lean protein, low-fat dairy products, cereal, brown rice, and bread. In addition, participants received dietary consultations. Yet, those who got free food and coaching did not see improvements in their average blood sugar (the study’s primary outcome), and their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels appeared to have worsened.

“To be honest, I was surprised,” the study’s lead author, Joseph Doyle, PhD, professor at the Sloan School of Management at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told me. “I was hoping we would show improved outcomes, but the way to make progress is to do well-randomized trials to find out what works.”

I was not surprised by these results because a recent rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis in The BMJ did not show a Mediterranean-style diet to be the most effective for glycemic control. And Ms. Efem was not in fact following a Mediterranean-style diet.

Ms. Efem’s low-carb success story is anecdotal, but Dr. Glandt has an established track record from her 9 years’ experience as the medical director of the eponymous diabetes center she founded in Tel Aviv. A recent audit of 344 patients from the center found that after 6 months of following a very low–carbohydrate diet, 96.3% of those with diabetes saw their A1c fall from a median 7.6% to 6.3%. Weight loss was significant, with a median drop of 6.5 kg (14 pounds) for patients with diabetes and 5.7 kg for those with prediabetes. The diet comprises 5%-10% of calories from carbs, but Dr. Glandt does not use numeric targets with her patients.

Blood pressure, triglycerides, and liver enzymes also improved. And though LDL cholesterol went up by 8%, this result may have been offset by an accompanying 13% rise in HDL cholesterol. Of the 78 patients initially on insulin, 62 were able to stop this medication entirely.

Although these results aren’t from a clinical trial, they’re still highly meaningful because the current dietary standard of care for type 2 diabetes can only slow the progression of the disease, not cause remission. Indeed, the idea that type 2 diabetes could be put into remission was not seriously considered by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) until 2009. By 2019, an ADA report concluded that “[r]educing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated the most evidence for improving glycemia.” In other words, the best way to improve the key factor in diabetes is to reduce total carbohydrates. Yet, the ADA still advocates filling one quarter of one’s plate with carbohydrate-based foods, an amount that will prevent remission. Given that the ADA’s vision statement is “a life free of diabetes,” it seems negligent not to tell people with a deadly condition that they can reverse this diagnosis.

A 2023 meta-analysis of 42 controlled clinical trials on 4809 patients showed that a very low–carbohydrate ketogenic diet (keto) was “superior” to alternatives for glycemic control. A more recent review of 11 clinical trials found that this diet was equal but not superior to other nutritional approaches in terms of blood sugar control, but this review also concluded that keto led to greater increases in HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides.

Dr. Glandt’s patients in the Bronx might not seem like obvious low-carb candidates. The diet is considered expensive and difficult to sustain. My interviews with a half dozen patients revealed some of these difficulties, but even for a woman living in a homeless shelter, the obstacles are not insurmountable.

Jerrilyn, who preferred that I use only her first name, lives in a shelter in Queens. While we strolled through a nearby park, she told me about her desire to lose weight and recover from polycystic ovary syndrome, which terrified her because it had caused dramatic hair loss. When she landed in Dr. Glandt’s office at age 28, she weighed 180 pounds.

Less than 5 months later, Jerrilyn had lost 25 pounds, and her period had returned with some regularity. She said she used “food stamps,” known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to buy most of her food at local delis because the meals served at the shelter were too heavy in starches. She starts her day with eggs, turkey bacon, and avocado.

“It was hard to give up carbohydrates because in my culture [Latina], we have nothing but carbs: rice, potatoes, yuca,” Jerrilyn shared. She noticed that carbs make her hungrier, but after 3 days of going low-carb, her cravings diminished. “It was like getting over an addiction,” she said.

Jerrilyn told me she’d seen many doctors but none as involved as Dr. Glandt. “It feels awesome to know that I have a lot of really useful information coming from her all the time.” The OwnaHealth app tracks weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, ketones, meals, mood, and cravings. Patients wear continuous glucose monitors and enter other information manually. Ketone bodies are used to measure dietary adherence and are obtained through finger pricks and test strips provided by OwnaHealth. Dr. Glandt gives patients her own food plan, along with free visual guides to low-carbohydrate foods by dietdoctor.com.

Dr. Glandt also sends her patients for regular blood work. She says she does not frequently see a rise in LDL cholesterol, which can sometimes occur on a low-carbohydrate diet. This effect is most common among people who are lean and fit. She says she doesn’t discontinue statins unless cholesterol levels improve significantly.

Samuel Gonzalez, age 56, weighed 275 pounds when he walked into Dr. Glandt’s office this past November. His A1c was 9.2%, but none of his previous doctors had diagnosed him with diabetes. “I was like a walking bag of sugar!” he joked.

A low-carbohydrate diet seemed absurd to a Puerto Rican like himself: “Having coffee without sugar? That’s like sacrilegious in my culture!” exclaimed Mr. Gonzalez. Still, he managed, with SNAP, to cook eggs and bacon for breakfast and some kind of protein for dinner. He keeps lunch light, “like tuna fish,” and finds checking in with the OwnaHealth app to be very helpful. “Every day, I’m on it,” he said. In the past 7 months, he’s lost 50 pounds, normalized his cholesterol and blood pressure levels, and lowered his A1c to 5.5%.

Mr. Gonzalez gets disability payments due to a back injury, and Ms. Efem receives government payments because her husband died serving in the military. Ms. Efem says her new diet challenges her budget, but Mr. Gonzalez says he manages easily.

Mélissa Cruz, a 28-year-old studying to be a nail technician while also doing back office work at a physical therapy practice, says she’s stretched thin. “I end up sad because I can’t put energy into looking up recipes and cooking for me and my boyfriend,” she told me. She’ll often cook rice and plantains for him and meat for herself, but “it’s frustrating when I’m low on funds and can’t figure out what to eat.”

Low-carbohydrate diets have a reputation for being expensive because people often start eating pricier foods, like meat and cheese, to replace cheaper starchy foods such as pasta and rice.

A 2019 cost analysis published in Nutrition & Dietetics compared a low-carbohydrate dietary pattern with the New Zealand government’s recommended guidelines (which are almost identical to those in the United States) and found that it cost only an extra $1.27 in US dollars per person per day. One explanation is that protein and fat are more satiating than carbohydrates, so people who mostly consume these macronutrients often cut back on snacks like packaged chips, crackers, and even fruits. Also, those on a ketogenic diet usually cut down on medications, so the additional $1.27 daily is likely offset by reduced spending at the pharmacy.

It’s not just Bronx residents with low socioeconomic status (SES) who adapt well to low-carbohydrate diets. Among Alabama state employees with diabetes enrolled in a low-carbohydrate dietary program provided by a company called Virta, the low SES population had the best outcomes. Virta also published survey data in 2023 showing that participants in a program with the Veteran’s Administration did not find additional costs to be an obstacle to dietary adherence. In fact, some participants saw cost reductions due to decreased spending on processed snacks and fast foods.

Ms. Cruz told me she struggles financially, yet she’s still lost nearly 30 pounds in 5 months, and her A1c went from 7.1% down to 5.9%, putting her diabetes into remission. Equally motivating for her are the improvements she’s seen in other hormonal issues. Since childhood, she’s had acanthosis, a condition that causes the skin to darken in velvety patches, and more recently, she developed severe hirsutism to the point of growing sideburns. “I had tried going vegan and fasting, but these just weren’t sustainable for me, and I was so overwhelmed with counting calories all the time.” Now, on a low-carbohydrate diet, which doesn’t require calorie counting, she’s finally seeing both these conditions improve significantly.

When I last checked in with Ms. Cruz, she said she had “kind of ghosted” Dr. Glandt due to her work and school constraints, but she hadn’t abandoned the diet. She appreciated, too, that Dr. Glandt had not given up on her and kept calling and messaging. “She’s not at all like a typical doctor who would just tell me to lose weight and shake their head at me,” Ms. Cruz said.

Because Dr. Glandt’s approach is time-intensive and high-touch, it might seem impractical to scale up, but Dr. Glandt’s app uses artificial intelligence to help with communications thus allowing her, with help from part-time health coaches, to care for patients.

This early success in one of the United States’ poorest and sickest neighborhoods should give us hope that type 2 diabetes need not to be a progressive irreversible disease, even among the disadvantaged.

OwnaHealth’s track record, along with that of Virta and other similar low-carbohydrate medical practices also give hope to the food-is-medicine idea. Diabetes can go into remission, and people can be healed, provided that health practitioners prescribe the right foods. And in truth, it’s not a diet. It’s a way of eating that must be maintained. The sustainability of low-carbohydrate diets has been a point of contention, but the Virta trial, with 38% of patients sustaining remission at 2 years, showed that it’s possible. (OwnaHealth, for its part, offers long-term maintenance plans to help patients stay very low-carb permanently.)

Given the tremendous costs and health burden of diabetes, this approach should no doubt be the first line of treatment for doctors and the ADA. The past two decades of clinical trial research have demonstrated that remission of type 2 diabetes is possible through diet alone. It turns out that for metabolic diseases, only certain foods are truly medicine.

Tools and Tips for Clinicians:

- Free two-page keto starter’s guide by OwnaHealth; Dr. Glandt uses this guide with her patients.

- Illustrated low-carb guides by dietdoctor.com

- Free low-carbohydrate starter guide by the Michigan Collaborative for Type 2 Diabetes

- Low-Carb for Any Budget, a free digital booklet by Mark Cucuzzella, MD, and Kristie Sullivan, PhD

- Recipe and meal ideas from Ruled.me, Keto-Mojo.com, and

Dr. Teicholz is the founder of Nutrition Coalition, an independent nonprofit dedicated to ensuring that US dietary guidelines align with current science. She disclosed receiving book royalties from The Big Fat Surprise, and received honorarium not exceeding $2000 for speeches from various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

For 3 years, Ajala Efem’s type 2 diabetes was so poorly controlled that her blood sugar often soared northward of 500 mg/dL despite insulin shots three to five times a day. She would experience dizziness, vomiting, severe headaches, and the neuropathy in her feet made walking painful. She was also — literally — frothing at the mouth. The 47-year-old single mother of two adult children with mental disabilities feared that she would die.

Ms. Efem lives in the South Bronx, which is among the poorest areas of New York City, where the combined rate of prediabetes and diabetes is close to 30%, the highest rate of any borough in the city.

She had to wait 8 months for an appointment with an endocrinologist, but that visit proved to be life-changing. She lost 28 pounds and got off 15 medications in a single month. She did not join a gym or count calories; she simply changed the food she ate and adopted a low-carb diet.

“I went from being sick to feeling so great,” she told her endocrinologist recently: “My feet aren’t hurting; I’m not in pain; I’m eating as much as I want, and I really enjoy my food so much.”

Ms. Efem’s life-changing visit was with Mariela Glandt, MD, at the offices of Essen Health Care. One month earlier, Dr. Glandt’s company, OwnaHealth, was contracted by Essen to conduct a 100-person pilot program for endocrinology patients. Essen is the largest Medicaid provider in New York City, and “they were desperate for an endocrinologist,” said Dr. Glandt, who trained at Columbia University in New York. So she came — all the way from Madrid, Spain. She commutes monthly, staying for a week each visit.

Dr. Glandt keeps up this punishing schedule because, as she explains, “it’s such a high for me to see these incredible transformations.” Her mostly Black and Hispanic patients are poor and lack resources, yet they lose significant amounts of weight, and their health issues resolve.

“Food is medicine” is an idea very much in vogue. The concept was central to the landmark White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health in 2022 and is now the focus of a number of a wide range of government programs. Recently, the Senate held a hearing aimed at further expanding food as medicine programs.

Still, only a single randomized controlled clinical trial has been conducted on this nutritional approach, with unexpectedly disappointing results. In the mid-Atlantic region, 456 food-insecure adults with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to usual care or the provision of weekly groceries for their entire families for about 1 year. Provisions for a Mediterranean-style diet included whole grains, fruits and vegetables, lean protein, low-fat dairy products, cereal, brown rice, and bread. In addition, participants received dietary consultations. Yet, those who got free food and coaching did not see improvements in their average blood sugar (the study’s primary outcome), and their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels appeared to have worsened.

“To be honest, I was surprised,” the study’s lead author, Joseph Doyle, PhD, professor at the Sloan School of Management at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told me. “I was hoping we would show improved outcomes, but the way to make progress is to do well-randomized trials to find out what works.”

I was not surprised by these results because a recent rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis in The BMJ did not show a Mediterranean-style diet to be the most effective for glycemic control. And Ms. Efem was not in fact following a Mediterranean-style diet.

Ms. Efem’s low-carb success story is anecdotal, but Dr. Glandt has an established track record from her 9 years’ experience as the medical director of the eponymous diabetes center she founded in Tel Aviv. A recent audit of 344 patients from the center found that after 6 months of following a very low–carbohydrate diet, 96.3% of those with diabetes saw their A1c fall from a median 7.6% to 6.3%. Weight loss was significant, with a median drop of 6.5 kg (14 pounds) for patients with diabetes and 5.7 kg for those with prediabetes. The diet comprises 5%-10% of calories from carbs, but Dr. Glandt does not use numeric targets with her patients.

Blood pressure, triglycerides, and liver enzymes also improved. And though LDL cholesterol went up by 8%, this result may have been offset by an accompanying 13% rise in HDL cholesterol. Of the 78 patients initially on insulin, 62 were able to stop this medication entirely.

Although these results aren’t from a clinical trial, they’re still highly meaningful because the current dietary standard of care for type 2 diabetes can only slow the progression of the disease, not cause remission. Indeed, the idea that type 2 diabetes could be put into remission was not seriously considered by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) until 2009. By 2019, an ADA report concluded that “[r]educing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated the most evidence for improving glycemia.” In other words, the best way to improve the key factor in diabetes is to reduce total carbohydrates. Yet, the ADA still advocates filling one quarter of one’s plate with carbohydrate-based foods, an amount that will prevent remission. Given that the ADA’s vision statement is “a life free of diabetes,” it seems negligent not to tell people with a deadly condition that they can reverse this diagnosis.

A 2023 meta-analysis of 42 controlled clinical trials on 4809 patients showed that a very low–carbohydrate ketogenic diet (keto) was “superior” to alternatives for glycemic control. A more recent review of 11 clinical trials found that this diet was equal but not superior to other nutritional approaches in terms of blood sugar control, but this review also concluded that keto led to greater increases in HDL cholesterol and lower triglycerides.

Dr. Glandt’s patients in the Bronx might not seem like obvious low-carb candidates. The diet is considered expensive and difficult to sustain. My interviews with a half dozen patients revealed some of these difficulties, but even for a woman living in a homeless shelter, the obstacles are not insurmountable.

Jerrilyn, who preferred that I use only her first name, lives in a shelter in Queens. While we strolled through a nearby park, she told me about her desire to lose weight and recover from polycystic ovary syndrome, which terrified her because it had caused dramatic hair loss. When she landed in Dr. Glandt’s office at age 28, she weighed 180 pounds.

Less than 5 months later, Jerrilyn had lost 25 pounds, and her period had returned with some regularity. She said she used “food stamps,” known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), to buy most of her food at local delis because the meals served at the shelter were too heavy in starches. She starts her day with eggs, turkey bacon, and avocado.

“It was hard to give up carbohydrates because in my culture [Latina], we have nothing but carbs: rice, potatoes, yuca,” Jerrilyn shared. She noticed that carbs make her hungrier, but after 3 days of going low-carb, her cravings diminished. “It was like getting over an addiction,” she said.

Jerrilyn told me she’d seen many doctors but none as involved as Dr. Glandt. “It feels awesome to know that I have a lot of really useful information coming from her all the time.” The OwnaHealth app tracks weight, blood pressure, blood sugar, ketones, meals, mood, and cravings. Patients wear continuous glucose monitors and enter other information manually. Ketone bodies are used to measure dietary adherence and are obtained through finger pricks and test strips provided by OwnaHealth. Dr. Glandt gives patients her own food plan, along with free visual guides to low-carbohydrate foods by dietdoctor.com.

Dr. Glandt also sends her patients for regular blood work. She says she does not frequently see a rise in LDL cholesterol, which can sometimes occur on a low-carbohydrate diet. This effect is most common among people who are lean and fit. She says she doesn’t discontinue statins unless cholesterol levels improve significantly.

Samuel Gonzalez, age 56, weighed 275 pounds when he walked into Dr. Glandt’s office this past November. His A1c was 9.2%, but none of his previous doctors had diagnosed him with diabetes. “I was like a walking bag of sugar!” he joked.

A low-carbohydrate diet seemed absurd to a Puerto Rican like himself: “Having coffee without sugar? That’s like sacrilegious in my culture!” exclaimed Mr. Gonzalez. Still, he managed, with SNAP, to cook eggs and bacon for breakfast and some kind of protein for dinner. He keeps lunch light, “like tuna fish,” and finds checking in with the OwnaHealth app to be very helpful. “Every day, I’m on it,” he said. In the past 7 months, he’s lost 50 pounds, normalized his cholesterol and blood pressure levels, and lowered his A1c to 5.5%.

Mr. Gonzalez gets disability payments due to a back injury, and Ms. Efem receives government payments because her husband died serving in the military. Ms. Efem says her new diet challenges her budget, but Mr. Gonzalez says he manages easily.

Mélissa Cruz, a 28-year-old studying to be a nail technician while also doing back office work at a physical therapy practice, says she’s stretched thin. “I end up sad because I can’t put energy into looking up recipes and cooking for me and my boyfriend,” she told me. She’ll often cook rice and plantains for him and meat for herself, but “it’s frustrating when I’m low on funds and can’t figure out what to eat.”

Low-carbohydrate diets have a reputation for being expensive because people often start eating pricier foods, like meat and cheese, to replace cheaper starchy foods such as pasta and rice.

A 2019 cost analysis published in Nutrition & Dietetics compared a low-carbohydrate dietary pattern with the New Zealand government’s recommended guidelines (which are almost identical to those in the United States) and found that it cost only an extra $1.27 in US dollars per person per day. One explanation is that protein and fat are more satiating than carbohydrates, so people who mostly consume these macronutrients often cut back on snacks like packaged chips, crackers, and even fruits. Also, those on a ketogenic diet usually cut down on medications, so the additional $1.27 daily is likely offset by reduced spending at the pharmacy.

It’s not just Bronx residents with low socioeconomic status (SES) who adapt well to low-carbohydrate diets. Among Alabama state employees with diabetes enrolled in a low-carbohydrate dietary program provided by a company called Virta, the low SES population had the best outcomes. Virta also published survey data in 2023 showing that participants in a program with the Veteran’s Administration did not find additional costs to be an obstacle to dietary adherence. In fact, some participants saw cost reductions due to decreased spending on processed snacks and fast foods.

Ms. Cruz told me she struggles financially, yet she’s still lost nearly 30 pounds in 5 months, and her A1c went from 7.1% down to 5.9%, putting her diabetes into remission. Equally motivating for her are the improvements she’s seen in other hormonal issues. Since childhood, she’s had acanthosis, a condition that causes the skin to darken in velvety patches, and more recently, she developed severe hirsutism to the point of growing sideburns. “I had tried going vegan and fasting, but these just weren’t sustainable for me, and I was so overwhelmed with counting calories all the time.” Now, on a low-carbohydrate diet, which doesn’t require calorie counting, she’s finally seeing both these conditions improve significantly.

When I last checked in with Ms. Cruz, she said she had “kind of ghosted” Dr. Glandt due to her work and school constraints, but she hadn’t abandoned the diet. She appreciated, too, that Dr. Glandt had not given up on her and kept calling and messaging. “She’s not at all like a typical doctor who would just tell me to lose weight and shake their head at me,” Ms. Cruz said.

Because Dr. Glandt’s approach is time-intensive and high-touch, it might seem impractical to scale up, but Dr. Glandt’s app uses artificial intelligence to help with communications thus allowing her, with help from part-time health coaches, to care for patients.

This early success in one of the United States’ poorest and sickest neighborhoods should give us hope that type 2 diabetes need not to be a progressive irreversible disease, even among the disadvantaged.

OwnaHealth’s track record, along with that of Virta and other similar low-carbohydrate medical practices also give hope to the food-is-medicine idea. Diabetes can go into remission, and people can be healed, provided that health practitioners prescribe the right foods. And in truth, it’s not a diet. It’s a way of eating that must be maintained. The sustainability of low-carbohydrate diets has been a point of contention, but the Virta trial, with 38% of patients sustaining remission at 2 years, showed that it’s possible. (OwnaHealth, for its part, offers long-term maintenance plans to help patients stay very low-carb permanently.)

Given the tremendous costs and health burden of diabetes, this approach should no doubt be the first line of treatment for doctors and the ADA. The past two decades of clinical trial research have demonstrated that remission of type 2 diabetes is possible through diet alone. It turns out that for metabolic diseases, only certain foods are truly medicine.

Tools and Tips for Clinicians:

- Free two-page keto starter’s guide by OwnaHealth; Dr. Glandt uses this guide with her patients.

- Illustrated low-carb guides by dietdoctor.com

- Free low-carbohydrate starter guide by the Michigan Collaborative for Type 2 Diabetes

- Low-Carb for Any Budget, a free digital booklet by Mark Cucuzzella, MD, and Kristie Sullivan, PhD

- Recipe and meal ideas from Ruled.me, Keto-Mojo.com, and

Dr. Teicholz is the founder of Nutrition Coalition, an independent nonprofit dedicated to ensuring that US dietary guidelines align with current science. She disclosed receiving book royalties from The Big Fat Surprise, and received honorarium not exceeding $2000 for speeches from various sources.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

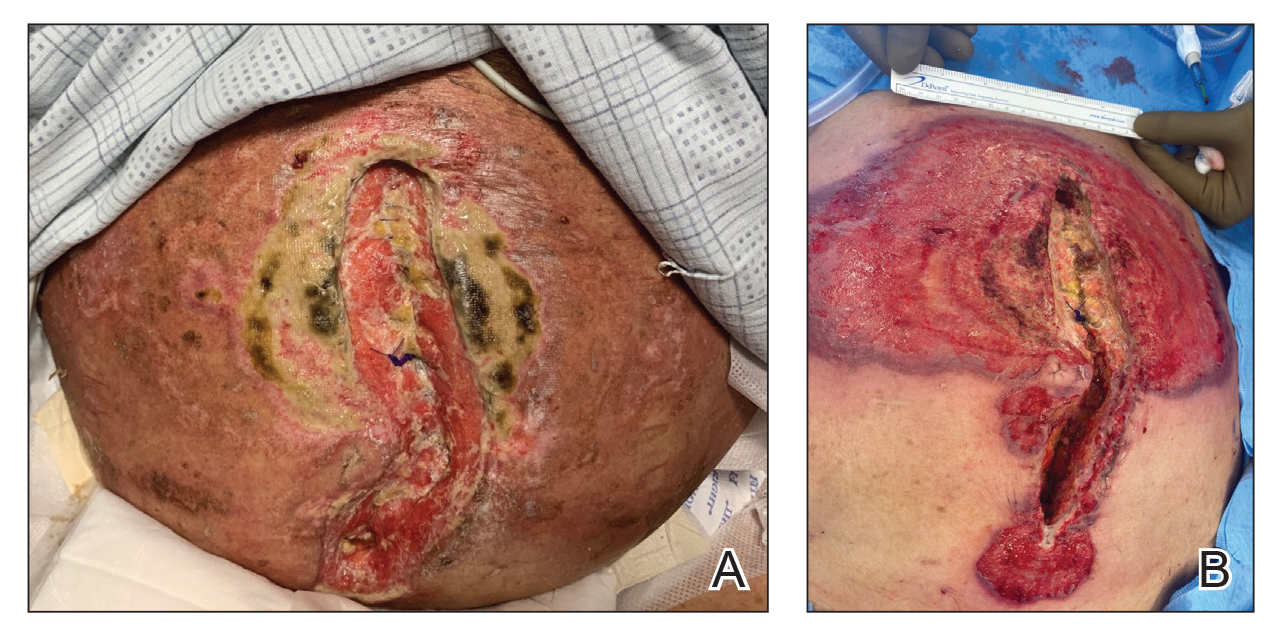

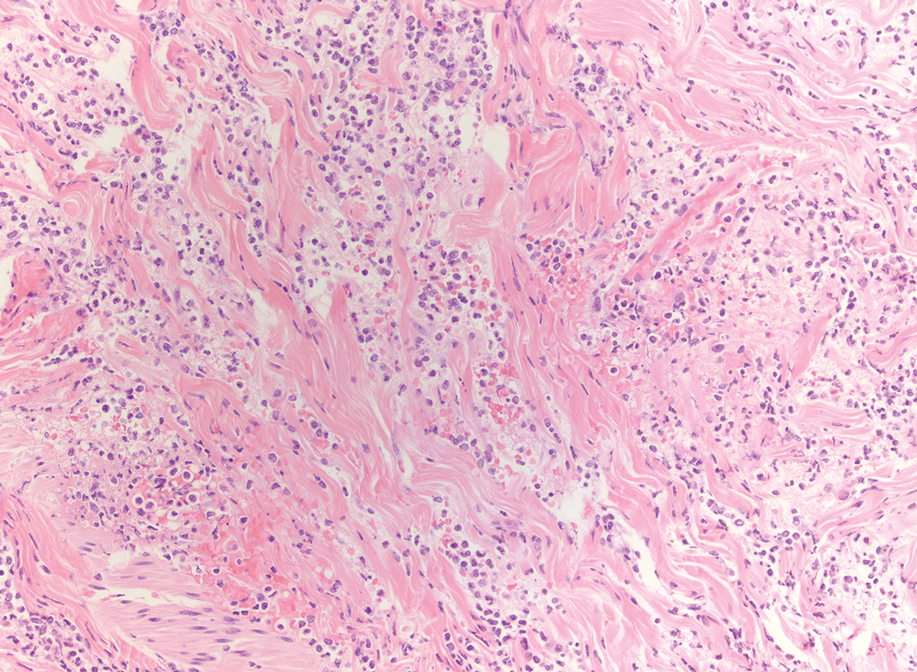

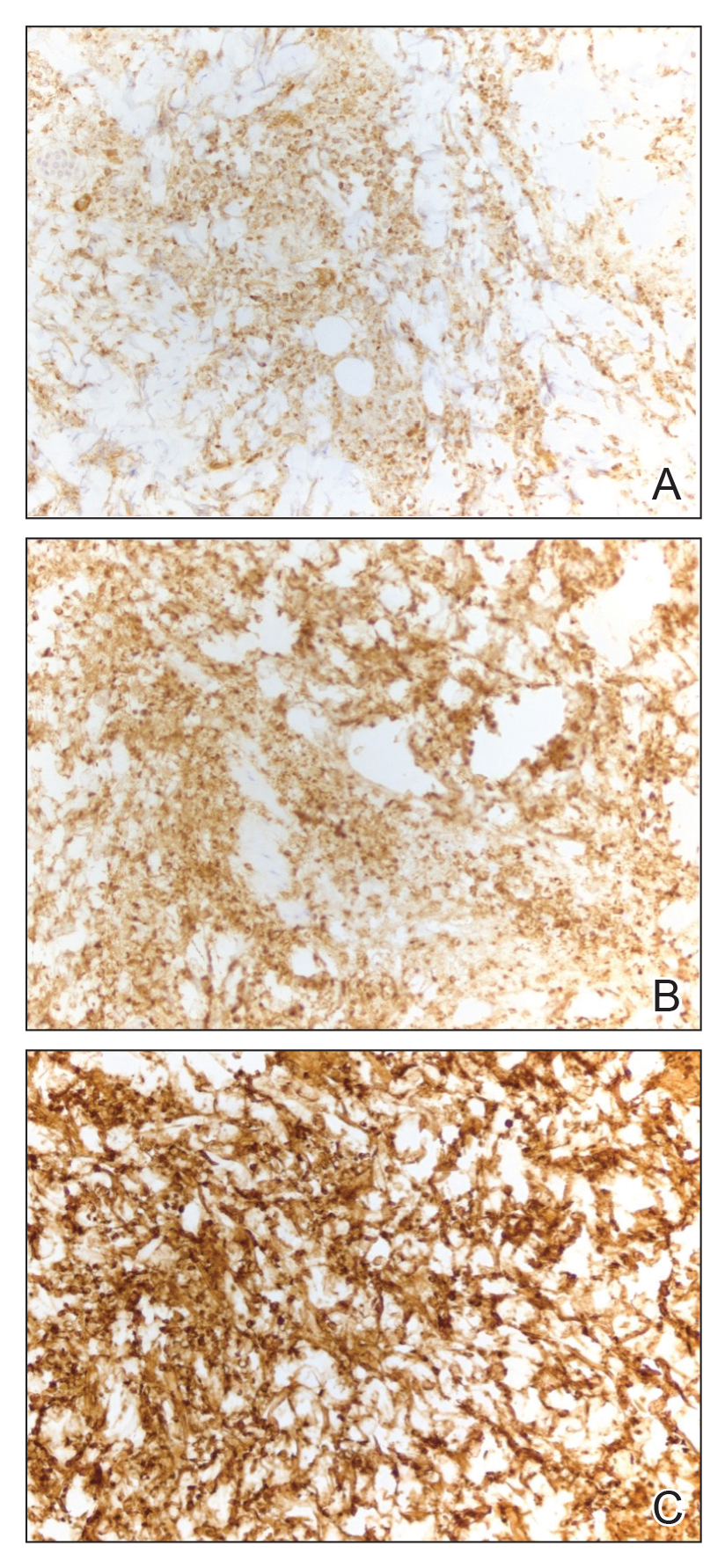

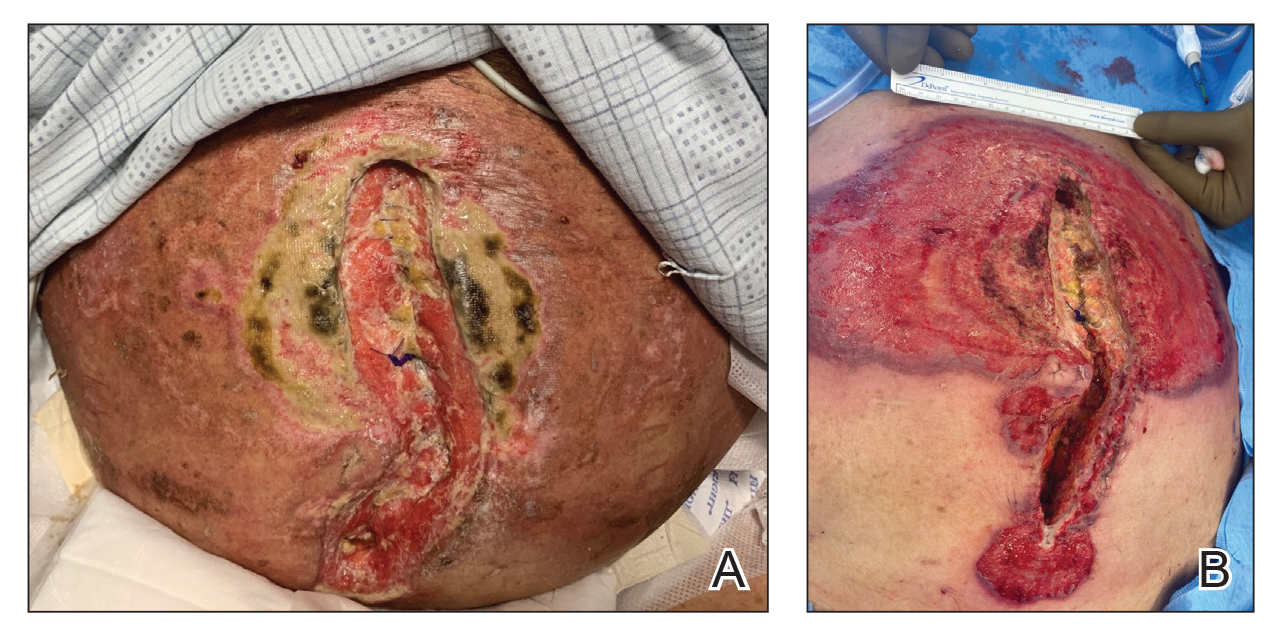

In Some Patients, Antiseizure Medications Can Cause Severe Skin Reactions

according to authors of a recent review. And if putting higher-risk patients on drugs most associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–related reaction risk before test results are available, authors advised starting at low doses and titrating slowly.

“When someone is having a seizure drug prescribed,” said senior author Ram Mani, MD, MSCE, chief of epilepsy at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, New Jersey, “it’s often a tense clinical situation because the patient has either had the first few seizures of their life, or they’ve had a worsening in their seizures.”

To help physicians optimize choices, Dr. Mani and colleagues reviewed literature regarding 31 ASMs. Their study was published in Current Treatment Options in Neurology.

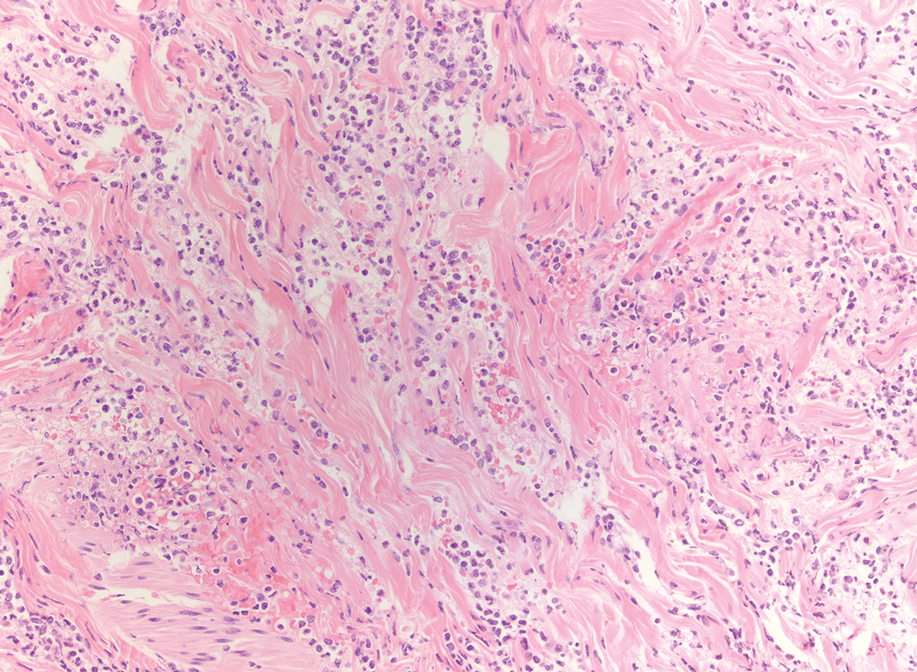

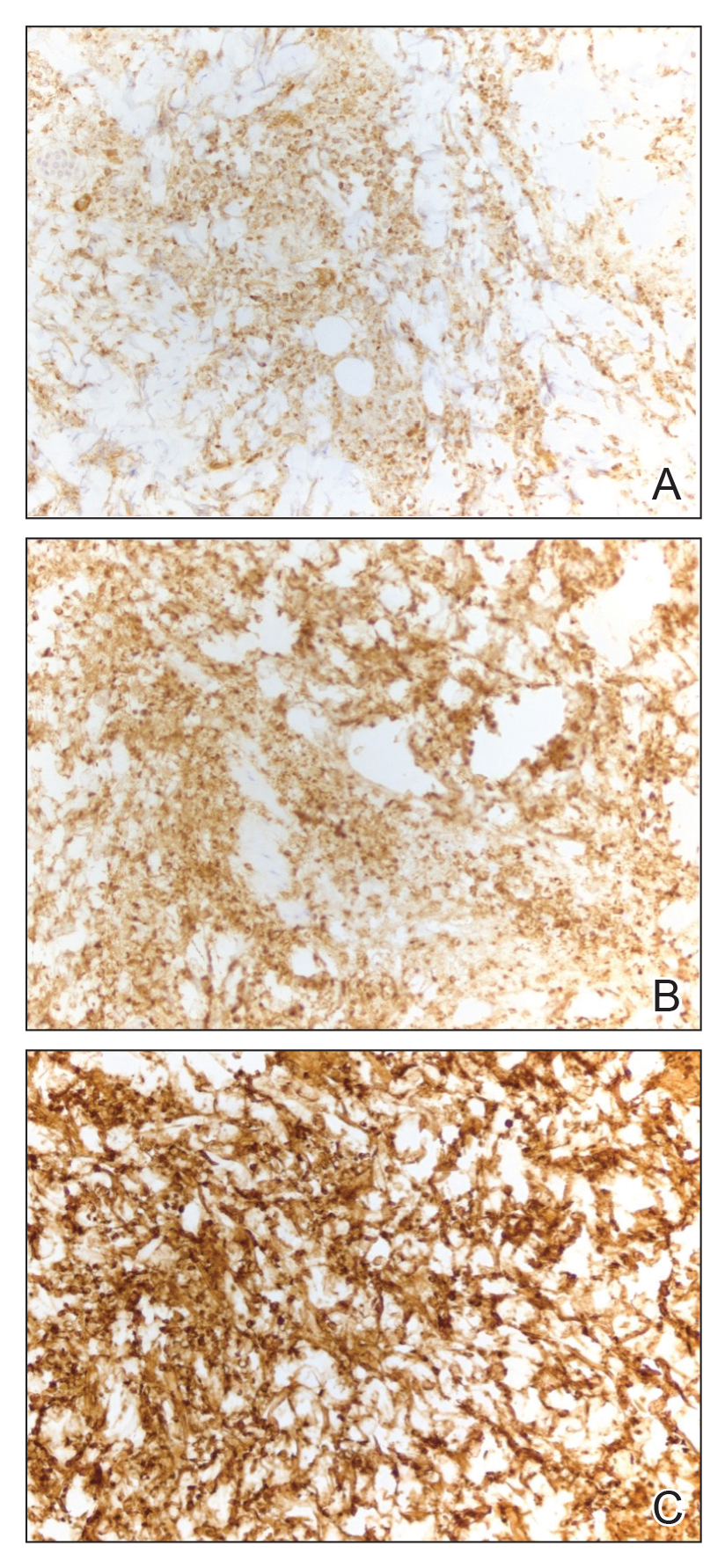

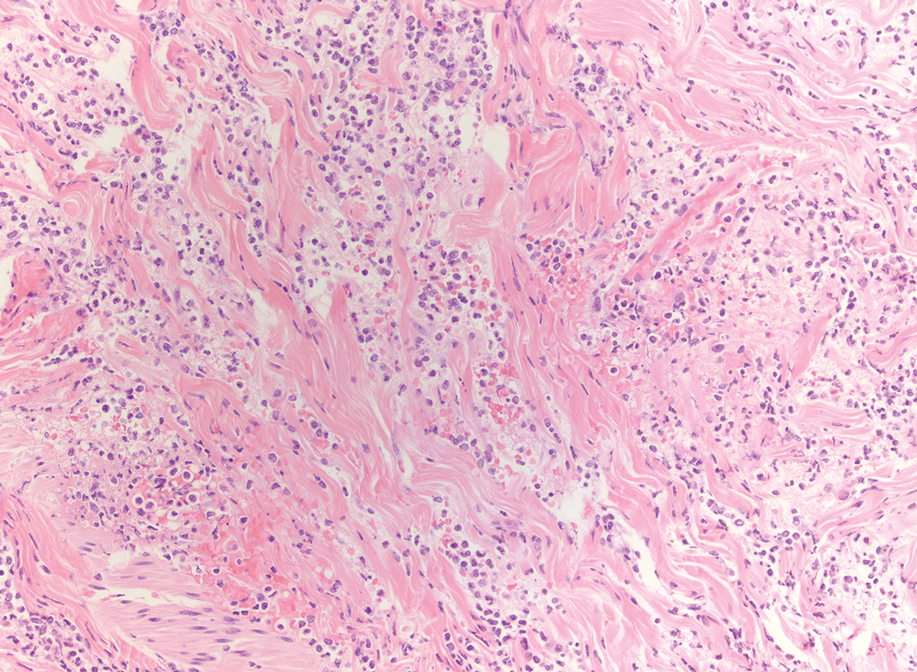

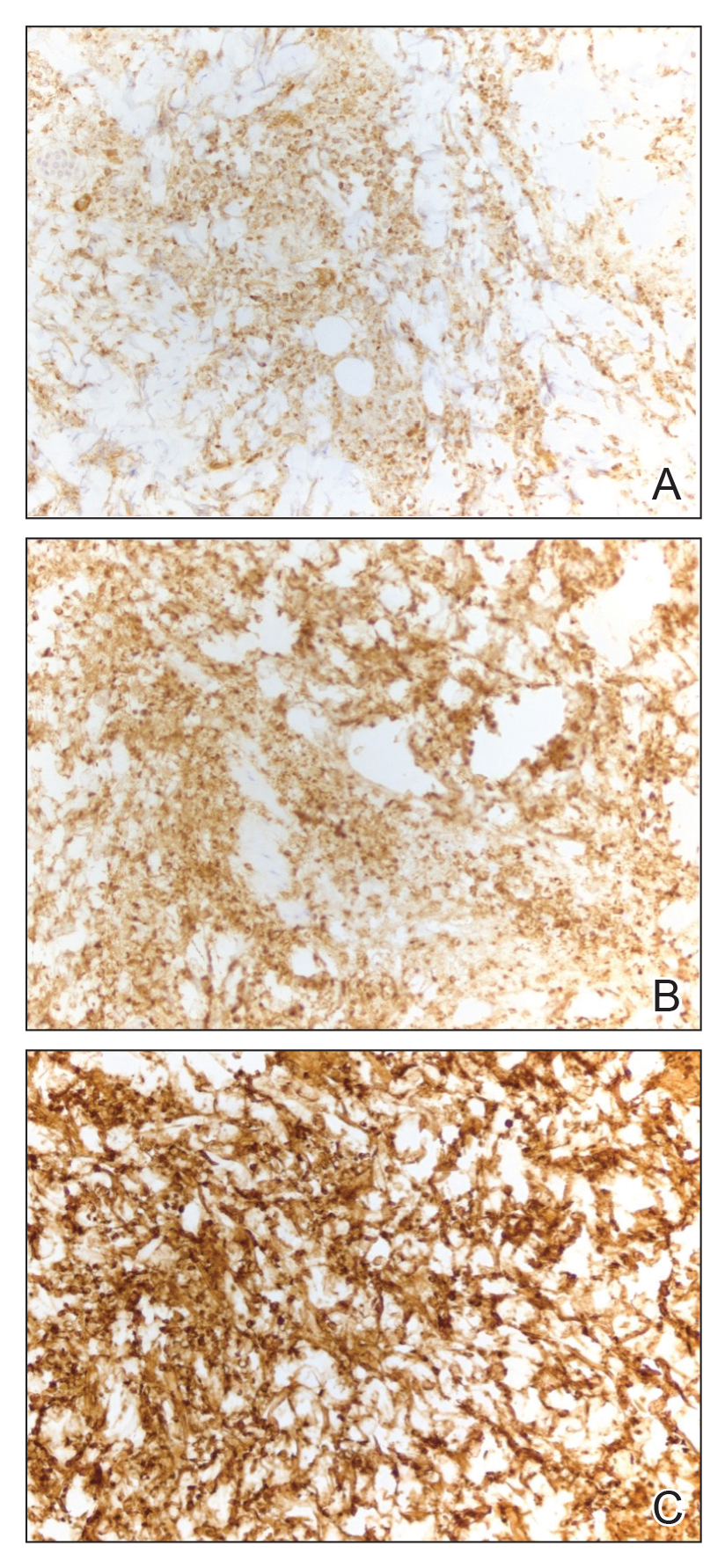

Overall, said Dr. Mani, incidence of benign skin reactions such as morbilliform exanthematous eruptions, which account for 95% of cutaneous adverse drug reactions (CADRs), ranges from a few percent up to 15%. “It’s a somewhat common occurrence. Fortunately, the reactions that can lead to morbidity and mortality are fairly rare.”

Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions

Among the five ASMs approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 2018, cenobamate has sparked the greatest concern. In early clinical development for epilepsy, a fast titration schedule (starting at 50 mg/day and increasing by 50 mg every 2 weeks to at least 200 mg/day) resulted in three cases of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS, also called drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction/DIHS), including one fatal case. Based on a phase 3 trial, the drug’s manufacturer now recommends starting at 12.5 mg and titrating more slowly.

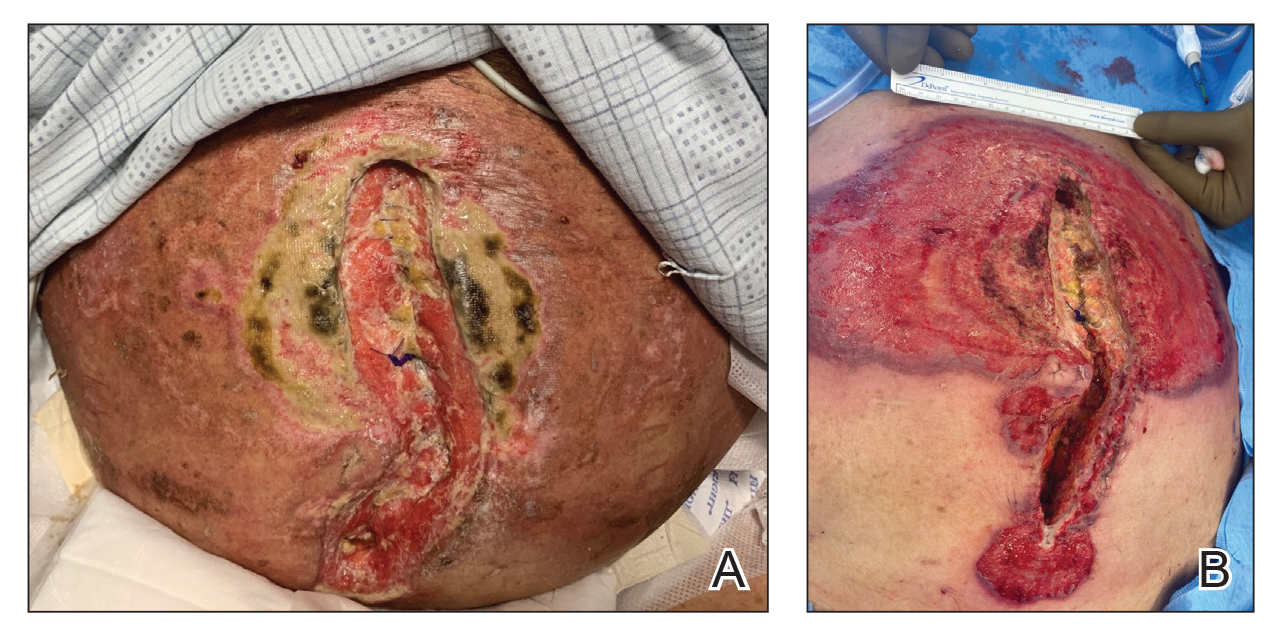

DRESS/DIHS appears within 2-6 weeks of drug exposure. Along with malaise, fever, and conjunctivitis, symptoms can include skin eruptions ranging from morbilliform to hemorrhagic and bullous. “Facial edema and early facial rash are classic findings,” the authors added. DRESS also can involve painful lymphadenopathy and potentially life-threatening damage to the liver, heart, and other organs.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), which is characterized by detached skin measuring less than 10% of the entire body surface area, typically happens within the first month of drug exposure. Flu-like symptoms can appear 1-3 days before erythematous to dusky macules, commonly on the chest, as well as cutaneous and mucosal erosions. Along with the skin and conjunctiva, SJS can affect the eyes, lungs, liver, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract.

When patients present with possible DRESS or SJS, the authors recommended inpatient multidisciplinary care. Having ready access to blood tests can help assess severity and prognosis, Dr. Mani explained. Inpatient evaluation and treatment also may allow faster access to other specialists as needed, and monitoring of potential seizure exacerbation in patients with uncontrolled seizures for whom the drug provided benefit but required abrupt discontinuation.

Often, he added, all hope is not lost for future use of the medication after a minor skin reaction. A case series and literature review of mild lamotrigine-associated CADRs showed that most patients could reintroduce and titrate lamotrigine by waiting at least 4 weeks, beginning at 5 mg/day, and gradually increasing to 25 mg/day.

Identifying Those at Risk

With millions of patients being newly prescribed ASMs annually, accurately screening out all people at risk of severe cutaneous adverse reactions based on available genetic information is impossible. The complexity of evolving recommendations for HLA testing makes them hard to remember, Dr. Mani said. “Development and better use of clinical decision support systems can help.”

Accordingly, he starts with a thorough history and physical examination, inquiring about prior skin reactions or hypersensitivity, which are risk factors for future reactions to drugs such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, rufinamide, and zonisamide. “Most of the medicines that the HLA tests are being done for are not the initial medicines I typically prescribe for a patient with newly diagnosed epilepsy,” said Dr. Mani. For ASM-naive patients with moderate or high risk of skin hypersensitivity reactions, he usually starts with lacosamide, levetiracetam, or brivaracetam. Additional low-risk drugs he considers in more complex cases include valproate, topiramate, and clobazam.

Only if a patient’s initial ASM causes problems will Dr. Mani consider higher-risk options and order HLA tests for patients belonging to indicated groups — such as testing for HLA-B*15:02 in Asian patients being considered for carbamazepine. About once weekly, he must put a patient on a potentially higher-risk drug before test results are available. If after a thorough risk-benefit discussion, he and the patient agree that the higher-risk drug is warranted, Dr. Mani starts at a lower-than-labeled dose, with a slower titration schedule that typically extends the ramp-up period by 1 week.

Fortunately, Dr. Mani said that, in 20 years of practice, he has seen more misdiagnoses — involving rashes from poison ivy, viral infections, or allergies — than actual ASM-induced reactions. “That’s why the patient, family, and practitioner need to be open-minded about what could be causing the rash.”

Dr. Mani reported no relevant conflicts. The study authors reported no funding sources.

according to authors of a recent review. And if putting higher-risk patients on drugs most associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–related reaction risk before test results are available, authors advised starting at low doses and titrating slowly.

“When someone is having a seizure drug prescribed,” said senior author Ram Mani, MD, MSCE, chief of epilepsy at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, New Jersey, “it’s often a tense clinical situation because the patient has either had the first few seizures of their life, or they’ve had a worsening in their seizures.”

To help physicians optimize choices, Dr. Mani and colleagues reviewed literature regarding 31 ASMs. Their study was published in Current Treatment Options in Neurology.

Overall, said Dr. Mani, incidence of benign skin reactions such as morbilliform exanthematous eruptions, which account for 95% of cutaneous adverse drug reactions (CADRs), ranges from a few percent up to 15%. “It’s a somewhat common occurrence. Fortunately, the reactions that can lead to morbidity and mortality are fairly rare.”

Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions

Among the five ASMs approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 2018, cenobamate has sparked the greatest concern. In early clinical development for epilepsy, a fast titration schedule (starting at 50 mg/day and increasing by 50 mg every 2 weeks to at least 200 mg/day) resulted in three cases of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS, also called drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction/DIHS), including one fatal case. Based on a phase 3 trial, the drug’s manufacturer now recommends starting at 12.5 mg and titrating more slowly.

DRESS/DIHS appears within 2-6 weeks of drug exposure. Along with malaise, fever, and conjunctivitis, symptoms can include skin eruptions ranging from morbilliform to hemorrhagic and bullous. “Facial edema and early facial rash are classic findings,” the authors added. DRESS also can involve painful lymphadenopathy and potentially life-threatening damage to the liver, heart, and other organs.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), which is characterized by detached skin measuring less than 10% of the entire body surface area, typically happens within the first month of drug exposure. Flu-like symptoms can appear 1-3 days before erythematous to dusky macules, commonly on the chest, as well as cutaneous and mucosal erosions. Along with the skin and conjunctiva, SJS can affect the eyes, lungs, liver, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract.

When patients present with possible DRESS or SJS, the authors recommended inpatient multidisciplinary care. Having ready access to blood tests can help assess severity and prognosis, Dr. Mani explained. Inpatient evaluation and treatment also may allow faster access to other specialists as needed, and monitoring of potential seizure exacerbation in patients with uncontrolled seizures for whom the drug provided benefit but required abrupt discontinuation.

Often, he added, all hope is not lost for future use of the medication after a minor skin reaction. A case series and literature review of mild lamotrigine-associated CADRs showed that most patients could reintroduce and titrate lamotrigine by waiting at least 4 weeks, beginning at 5 mg/day, and gradually increasing to 25 mg/day.

Identifying Those at Risk

With millions of patients being newly prescribed ASMs annually, accurately screening out all people at risk of severe cutaneous adverse reactions based on available genetic information is impossible. The complexity of evolving recommendations for HLA testing makes them hard to remember, Dr. Mani said. “Development and better use of clinical decision support systems can help.”

Accordingly, he starts with a thorough history and physical examination, inquiring about prior skin reactions or hypersensitivity, which are risk factors for future reactions to drugs such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, rufinamide, and zonisamide. “Most of the medicines that the HLA tests are being done for are not the initial medicines I typically prescribe for a patient with newly diagnosed epilepsy,” said Dr. Mani. For ASM-naive patients with moderate or high risk of skin hypersensitivity reactions, he usually starts with lacosamide, levetiracetam, or brivaracetam. Additional low-risk drugs he considers in more complex cases include valproate, topiramate, and clobazam.

Only if a patient’s initial ASM causes problems will Dr. Mani consider higher-risk options and order HLA tests for patients belonging to indicated groups — such as testing for HLA-B*15:02 in Asian patients being considered for carbamazepine. About once weekly, he must put a patient on a potentially higher-risk drug before test results are available. If after a thorough risk-benefit discussion, he and the patient agree that the higher-risk drug is warranted, Dr. Mani starts at a lower-than-labeled dose, with a slower titration schedule that typically extends the ramp-up period by 1 week.

Fortunately, Dr. Mani said that, in 20 years of practice, he has seen more misdiagnoses — involving rashes from poison ivy, viral infections, or allergies — than actual ASM-induced reactions. “That’s why the patient, family, and practitioner need to be open-minded about what could be causing the rash.”

Dr. Mani reported no relevant conflicts. The study authors reported no funding sources.

according to authors of a recent review. And if putting higher-risk patients on drugs most associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–related reaction risk before test results are available, authors advised starting at low doses and titrating slowly.

“When someone is having a seizure drug prescribed,” said senior author Ram Mani, MD, MSCE, chief of epilepsy at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, New Jersey, “it’s often a tense clinical situation because the patient has either had the first few seizures of their life, or they’ve had a worsening in their seizures.”

To help physicians optimize choices, Dr. Mani and colleagues reviewed literature regarding 31 ASMs. Their study was published in Current Treatment Options in Neurology.

Overall, said Dr. Mani, incidence of benign skin reactions such as morbilliform exanthematous eruptions, which account for 95% of cutaneous adverse drug reactions (CADRs), ranges from a few percent up to 15%. “It’s a somewhat common occurrence. Fortunately, the reactions that can lead to morbidity and mortality are fairly rare.”

Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions

Among the five ASMs approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 2018, cenobamate has sparked the greatest concern. In early clinical development for epilepsy, a fast titration schedule (starting at 50 mg/day and increasing by 50 mg every 2 weeks to at least 200 mg/day) resulted in three cases of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS, also called drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction/DIHS), including one fatal case. Based on a phase 3 trial, the drug’s manufacturer now recommends starting at 12.5 mg and titrating more slowly.

DRESS/DIHS appears within 2-6 weeks of drug exposure. Along with malaise, fever, and conjunctivitis, symptoms can include skin eruptions ranging from morbilliform to hemorrhagic and bullous. “Facial edema and early facial rash are classic findings,” the authors added. DRESS also can involve painful lymphadenopathy and potentially life-threatening damage to the liver, heart, and other organs.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), which is characterized by detached skin measuring less than 10% of the entire body surface area, typically happens within the first month of drug exposure. Flu-like symptoms can appear 1-3 days before erythematous to dusky macules, commonly on the chest, as well as cutaneous and mucosal erosions. Along with the skin and conjunctiva, SJS can affect the eyes, lungs, liver, bone marrow, and gastrointestinal tract.

When patients present with possible DRESS or SJS, the authors recommended inpatient multidisciplinary care. Having ready access to blood tests can help assess severity and prognosis, Dr. Mani explained. Inpatient evaluation and treatment also may allow faster access to other specialists as needed, and monitoring of potential seizure exacerbation in patients with uncontrolled seizures for whom the drug provided benefit but required abrupt discontinuation.

Often, he added, all hope is not lost for future use of the medication after a minor skin reaction. A case series and literature review of mild lamotrigine-associated CADRs showed that most patients could reintroduce and titrate lamotrigine by waiting at least 4 weeks, beginning at 5 mg/day, and gradually increasing to 25 mg/day.

Identifying Those at Risk

With millions of patients being newly prescribed ASMs annually, accurately screening out all people at risk of severe cutaneous adverse reactions based on available genetic information is impossible. The complexity of evolving recommendations for HLA testing makes them hard to remember, Dr. Mani said. “Development and better use of clinical decision support systems can help.”

Accordingly, he starts with a thorough history and physical examination, inquiring about prior skin reactions or hypersensitivity, which are risk factors for future reactions to drugs such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, rufinamide, and zonisamide. “Most of the medicines that the HLA tests are being done for are not the initial medicines I typically prescribe for a patient with newly diagnosed epilepsy,” said Dr. Mani. For ASM-naive patients with moderate or high risk of skin hypersensitivity reactions, he usually starts with lacosamide, levetiracetam, or brivaracetam. Additional low-risk drugs he considers in more complex cases include valproate, topiramate, and clobazam.

Only if a patient’s initial ASM causes problems will Dr. Mani consider higher-risk options and order HLA tests for patients belonging to indicated groups — such as testing for HLA-B*15:02 in Asian patients being considered for carbamazepine. About once weekly, he must put a patient on a potentially higher-risk drug before test results are available. If after a thorough risk-benefit discussion, he and the patient agree that the higher-risk drug is warranted, Dr. Mani starts at a lower-than-labeled dose, with a slower titration schedule that typically extends the ramp-up period by 1 week.

Fortunately, Dr. Mani said that, in 20 years of practice, he has seen more misdiagnoses — involving rashes from poison ivy, viral infections, or allergies — than actual ASM-induced reactions. “That’s why the patient, family, and practitioner need to be open-minded about what could be causing the rash.”

Dr. Mani reported no relevant conflicts. The study authors reported no funding sources.

FROM CURRENT TREATMENT OPTIONS IN NEUROLOGY

Study Estimates Global Prevalence of Seborrheic Dermatitis

TOPLINE:

, according to a meta-analysis that also found a higher prevalence in adults than in children.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 121 studies, which included 1,260,163 people with clinician-diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis.

- The included studies represented nine countries; most were from India (n = 18), Turkey (n = 13), and the United States (n = 8).

- The primary outcome was the pooled prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall pooled prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis was 4.38%, 4.08% in clinical settings, and 4.71% in the studies conducted in the general population.

- The prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis was higher among adults (5.64%) than in children (3.7%) and neonates (0.23%).

- A significant variation was observed across countries, with South Africa having the highest prevalence at 8.82%, followed by the United States at 5.86% and Turkey at 3.74%, while India had the lowest prevalence at 2.62%.

IN PRACTICE:

The global prevalence in this meta-analysis was “higher than previous large-scale global estimates, with notable geographic and sociodemographic variability, highlighting the potential impact of environmental factors and cultural practices,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Meredith Tyree Polaskey, MS, Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, Illinois, and was published online on July 3, 2024, in the JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Interpretation of the findings is limited by research gaps in Central Asia, much of Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, Latin America (excluding Brazil), and the Caribbean, along with potential underreporting in regions with restricted healthcare access and significant heterogeneity across studies.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding information was not available. One author reported serving as an advisor, consultant, speaker, and/or investigator for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Amgen, and Pfizer.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a meta-analysis that also found a higher prevalence in adults than in children.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 121 studies, which included 1,260,163 people with clinician-diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis.

- The included studies represented nine countries; most were from India (n = 18), Turkey (n = 13), and the United States (n = 8).

- The primary outcome was the pooled prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall pooled prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis was 4.38%, 4.08% in clinical settings, and 4.71% in the studies conducted in the general population.

- The prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis was higher among adults (5.64%) than in children (3.7%) and neonates (0.23%).

- A significant variation was observed across countries, with South Africa having the highest prevalence at 8.82%, followed by the United States at 5.86% and Turkey at 3.74%, while India had the lowest prevalence at 2.62%.

IN PRACTICE:

The global prevalence in this meta-analysis was “higher than previous large-scale global estimates, with notable geographic and sociodemographic variability, highlighting the potential impact of environmental factors and cultural practices,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Meredith Tyree Polaskey, MS, Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, Illinois, and was published online on July 3, 2024, in the JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Interpretation of the findings is limited by research gaps in Central Asia, much of Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, Latin America (excluding Brazil), and the Caribbean, along with potential underreporting in regions with restricted healthcare access and significant heterogeneity across studies.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding information was not available. One author reported serving as an advisor, consultant, speaker, and/or investigator for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Amgen, and Pfizer.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a meta-analysis that also found a higher prevalence in adults than in children.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 121 studies, which included 1,260,163 people with clinician-diagnosed seborrheic dermatitis.

- The included studies represented nine countries; most were from India (n = 18), Turkey (n = 13), and the United States (n = 8).

- The primary outcome was the pooled prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The overall pooled prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis was 4.38%, 4.08% in clinical settings, and 4.71% in the studies conducted in the general population.

- The prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis was higher among adults (5.64%) than in children (3.7%) and neonates (0.23%).

- A significant variation was observed across countries, with South Africa having the highest prevalence at 8.82%, followed by the United States at 5.86% and Turkey at 3.74%, while India had the lowest prevalence at 2.62%.

IN PRACTICE:

The global prevalence in this meta-analysis was “higher than previous large-scale global estimates, with notable geographic and sociodemographic variability, highlighting the potential impact of environmental factors and cultural practices,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Meredith Tyree Polaskey, MS, Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, Illinois, and was published online on July 3, 2024, in the JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Interpretation of the findings is limited by research gaps in Central Asia, much of Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, Latin America (excluding Brazil), and the Caribbean, along with potential underreporting in regions with restricted healthcare access and significant heterogeneity across studies.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding information was not available. One author reported serving as an advisor, consultant, speaker, and/or investigator for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Amgen, and Pfizer.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Should Cancer Trial Eligibility Become More Inclusive?

The study, published online in Clinical Cancer Research, highlighted the potential benefits of broadening eligibility criteria for clinical trials.

“It is well known that results in an ‘ideal’ population do not always translate to the real-world population,” senior author Hans Gelderblom, MD, chair of the Department of Medical Oncology at the Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands, said in a press release. “Eligibility criteria are often too strict, and educated exemptions by experienced investigators can help individual patients, especially in a last-resort trial.”

Although experts have expressed interest in improving trial inclusivity, it’s unclear how doing so might impact treatment safety and efficacy.

In the Drug Rediscovery Protocol (DRUP), Dr. Gelderblom and colleagues examined the impact of broadening trial eligibility on patient outcomes. DRUP is an ongoing Dutch national, multicenter, pan-cancer, nonrandomized clinical trial in which patients are treated off-label with approved molecularly targeted or immunotherapies.

In the trial, 1019 patients with treatment-refractory disease were matched to one of the available study drugs based on their tumor molecular profile and enrolled in parallel cohorts. Cohorts were defined by tumor type, molecular profile, and study drug.

Among these patients, 82 patients — 8% of the cohort — were granted waivers to participate. Most waivers (45%) were granted as exceptions to general- or drug-related eligibility criteria, often because of out-of-range lab results. Other categories included treatment and testing exceptions, as well as out-of-window testing.

The researchers then compared safety and efficacy outcomes between the 82 participants granted waivers and the 937 who did not receive waivers.

Overall, Dr. Gelderblom’s team found that the rate of serious adverse events was similar between patients who received a waiver and those who did not: 39% vs 41%, respectively.

A relationship between waivers and serious adverse events was deemed “unlikely” for 86% of patients and “possible” for 14%. In two cases concerning a direct relationship, for instance, patients who received waivers for decreased hemoglobin levels developed anemia.

The rate of clinical benefit — defined as an objective response or stable disease for at least 16 weeks — was similar between the groups. Overall, 40% of patients who received a waiver (33 of 82) had a clinical benefit vs 33% of patients without a waiver (P = .43). Median overall survival for patients that received a waiver was also similar — 11 months in the waiver group and 8 months in the nonwaiver group (hazard ratio, 0.87; P = .33).

“Safety and clinical benefit were preserved in patients for whom a waiver was granted,” the authors concluded.

The study had several limitations. The diversity of cancer types, treatments, and reasons for protocol exemptions precluded subgroup analyses. In addition, because the decision to grant waivers depended in large part on the likelihood of clinical benefit, “it is possible that patients who received waivers were positively selected for clinical benefit compared with the general study population,” the authors wrote.

So, “although the clinical benefit rate of the patient group for whom a waiver was granted appears to be slightly higher, this difference might be explained by the selection process of the central study team, in which each waiver request was carefully considered, weighing the risks and potential benefits for the patient in question,” the authors explained.

Overall, “these findings advocate for a broader and more inclusive design when establishing novel trials, paving the way for a more effective and tailored application of cancer therapies in patients with advanced or refractory disease,” Dr. Gelderblom said.

Commenting on the study, Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, said that “relaxing eligibility criteria is important, and I support this. Trials should include patients that are more representative of the real-world, so that results are generalizable.”

However, “the paper overemphasized efficacy,” said Dr. Gyawali, from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. The sample size of waiver-granted patients was small, plus “the clinical benefit rate is not a marker of efficacy.

“The response rate is somewhat better, but for a heterogeneous study with multiple targets and drugs, it is difficult to say much about treatment effects here,” Dr. Gyawali added. Overall, “we shouldn’t read too much into treatment benefits based on these numbers.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Stelvio for Life Foundation, the Dutch Cancer Society, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, pharma&, Eisai Co., Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. Dr. Gelderblom declared no conflicts of interest, and Dr. Gyawali declared no conflicts of interest related to his comment.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The study, published online in Clinical Cancer Research, highlighted the potential benefits of broadening eligibility criteria for clinical trials.

“It is well known that results in an ‘ideal’ population do not always translate to the real-world population,” senior author Hans Gelderblom, MD, chair of the Department of Medical Oncology at the Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands, said in a press release. “Eligibility criteria are often too strict, and educated exemptions by experienced investigators can help individual patients, especially in a last-resort trial.”

Although experts have expressed interest in improving trial inclusivity, it’s unclear how doing so might impact treatment safety and efficacy.

In the Drug Rediscovery Protocol (DRUP), Dr. Gelderblom and colleagues examined the impact of broadening trial eligibility on patient outcomes. DRUP is an ongoing Dutch national, multicenter, pan-cancer, nonrandomized clinical trial in which patients are treated off-label with approved molecularly targeted or immunotherapies.

In the trial, 1019 patients with treatment-refractory disease were matched to one of the available study drugs based on their tumor molecular profile and enrolled in parallel cohorts. Cohorts were defined by tumor type, molecular profile, and study drug.

Among these patients, 82 patients — 8% of the cohort — were granted waivers to participate. Most waivers (45%) were granted as exceptions to general- or drug-related eligibility criteria, often because of out-of-range lab results. Other categories included treatment and testing exceptions, as well as out-of-window testing.

The researchers then compared safety and efficacy outcomes between the 82 participants granted waivers and the 937 who did not receive waivers.

Overall, Dr. Gelderblom’s team found that the rate of serious adverse events was similar between patients who received a waiver and those who did not: 39% vs 41%, respectively.

A relationship between waivers and serious adverse events was deemed “unlikely” for 86% of patients and “possible” for 14%. In two cases concerning a direct relationship, for instance, patients who received waivers for decreased hemoglobin levels developed anemia.

The rate of clinical benefit — defined as an objective response or stable disease for at least 16 weeks — was similar between the groups. Overall, 40% of patients who received a waiver (33 of 82) had a clinical benefit vs 33% of patients without a waiver (P = .43). Median overall survival for patients that received a waiver was also similar — 11 months in the waiver group and 8 months in the nonwaiver group (hazard ratio, 0.87; P = .33).

“Safety and clinical benefit were preserved in patients for whom a waiver was granted,” the authors concluded.

The study had several limitations. The diversity of cancer types, treatments, and reasons for protocol exemptions precluded subgroup analyses. In addition, because the decision to grant waivers depended in large part on the likelihood of clinical benefit, “it is possible that patients who received waivers were positively selected for clinical benefit compared with the general study population,” the authors wrote.

So, “although the clinical benefit rate of the patient group for whom a waiver was granted appears to be slightly higher, this difference might be explained by the selection process of the central study team, in which each waiver request was carefully considered, weighing the risks and potential benefits for the patient in question,” the authors explained.

Overall, “these findings advocate for a broader and more inclusive design when establishing novel trials, paving the way for a more effective and tailored application of cancer therapies in patients with advanced or refractory disease,” Dr. Gelderblom said.

Commenting on the study, Bishal Gyawali, MD, PhD, said that “relaxing eligibility criteria is important, and I support this. Trials should include patients that are more representative of the real-world, so that results are generalizable.”

However, “the paper overemphasized efficacy,” said Dr. Gyawali, from Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. The sample size of waiver-granted patients was small, plus “the clinical benefit rate is not a marker of efficacy.

“The response rate is somewhat better, but for a heterogeneous study with multiple targets and drugs, it is difficult to say much about treatment effects here,” Dr. Gyawali added. Overall, “we shouldn’t read too much into treatment benefits based on these numbers.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Stelvio for Life Foundation, the Dutch Cancer Society, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, pharma&, Eisai Co., Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. Dr. Gelderblom declared no conflicts of interest, and Dr. Gyawali declared no conflicts of interest related to his comment.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The study, published online in Clinical Cancer Research, highlighted the potential benefits of broadening eligibility criteria for clinical trials.

“It is well known that results in an ‘ideal’ population do not always translate to the real-world population,” senior author Hans Gelderblom, MD, chair of the Department of Medical Oncology at the Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands, said in a press release. “Eligibility criteria are often too strict, and educated exemptions by experienced investigators can help individual patients, especially in a last-resort trial.”

Although experts have expressed interest in improving trial inclusivity, it’s unclear how doing so might impact treatment safety and efficacy.

In the Drug Rediscovery Protocol (DRUP), Dr. Gelderblom and colleagues examined the impact of broadening trial eligibility on patient outcomes. DRUP is an ongoing Dutch national, multicenter, pan-cancer, nonrandomized clinical trial in which patients are treated off-label with approved molecularly targeted or immunotherapies.

In the trial, 1019 patients with treatment-refractory disease were matched to one of the available study drugs based on their tumor molecular profile and enrolled in parallel cohorts. Cohorts were defined by tumor type, molecular profile, and study drug.

Among these patients, 82 patients — 8% of the cohort — were granted waivers to participate. Most waivers (45%) were granted as exceptions to general- or drug-related eligibility criteria, often because of out-of-range lab results. Other categories included treatment and testing exceptions, as well as out-of-window testing.

The researchers then compared safety and efficacy outcomes between the 82 participants granted waivers and the 937 who did not receive waivers.

Overall, Dr. Gelderblom’s team found that the rate of serious adverse events was similar between patients who received a waiver and those who did not: 39% vs 41%, respectively.