User login

Hypertension worsened by commonly used prescription meds

Nearly half of these American adults had hypertension, and in this subgroup, 18.5% reported using a prescription drug known to increase blood pressure. The most widely used class of agents with this effect was antidepressants, used by 8.7%; followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), used by 6.5%; steroids, 1.9%; estrogens, 1.7%; and several other agents each used by fewer than 1% of the study cohort, John Vitarello, MD, said during a press briefing on reports from the upcoming annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

He and his associates estimated that this use of prescription drugs known to raise blood pressure could be what stands in the way of some 560,000-2.2 million Americans from having their hypertension under control, depending on the exact blood pressure impact that various pressure-increasing drugs have and presuming that half of those on blood pressure increasing agents could stop them and switch to alternative agents, said Dr. Vitarello, a researcher at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

He also highlighted that the study assessed only prescription drugs and did not examine OTC drug use, which may be especially relevant for the many people who regularly take NSAIDs.

“Clinicians should review the prescription and OTC drug use of patients with hypertension and consider stopping drugs that increase blood pressure or switching the patient to alternatives” that are blood pressure neutral, Dr. Vitarello said during the briefing. He cautioned that maintaining hypertensive patients on agents that raise their blood pressure can result in “prescribing cascades” where taking drugs that boost blood pressure results in need for intensified antihypertensive treatment.

An opportunity for NSAID alternatives

“This study hopefully raises awareness that there is a very high use of medications that increase blood pressure, and use of OTC agents could increase the rate even higher” said Eugene Yang, MD, a cardiologist and codirector of the Cardiovascular Wellness and Prevention Program of the University of Washington, Seattle. Substituting for certain antidepressant agents may often not be realistic, but an opportunity exists for reducing NSAID use, a class also linked with an increased risk for bleeding and other adverse effects, Dr. Yang said during the briefing. Minimizing use of NSAIDs including ibuprofen and naproxen use “is something to think about,” he suggested.

“The effect of NSAIDs on blood pressure is not well studied and can vary from person to person” noted Dr. Vitarello, who added that higher NSAID dosages and more prolonged use likely increase the risk for an adverse effect on blood pressure. One reasonable option is to encourage patients to use an alternative class of pain reliever such as acetaminophen.

It remains “a challenge” to discern differences in adverse blood pressure effects, and in all adverse cardiovascular effects among different NSAIDs, said Dr. Yang. Results from “some studies show that certain NSAIDs may be safer, but other studies did not. We need to be very careful using NSAIDs because, on average, they increase blood pressure by about 3 mm Hg. We need to be mindful to try to prescribe alternative agents, like acetaminophen.”

A decade of data from NHANES

The analysis run by Dr. Vitarello and associates used data from 27,599 American adults included in the NHANES during 2009-2018, and focused on the 44% who either had an average blood pressure measurement of at least 130/80 mm Hg or reported having ever been told by a clinician that they had hypertension. The NHANES assessments included the prescription medications taken by each participant. The prevalence of using at least one prescription drug known to raise blood pressure was 24% among women and 14% among men, and 4% of those with hypertension were on two or more pressure-increasing agents.

The researchers based their identification of pressure-increasing prescription drugs on the list included in the 2017 guideline for managing high blood pressure from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association. This list specifies that the antidepressants that raise blood pressure are the monoamine oxidase inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Dr. Vitarello and Dr. Yang had no disclosures.

Nearly half of these American adults had hypertension, and in this subgroup, 18.5% reported using a prescription drug known to increase blood pressure. The most widely used class of agents with this effect was antidepressants, used by 8.7%; followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), used by 6.5%; steroids, 1.9%; estrogens, 1.7%; and several other agents each used by fewer than 1% of the study cohort, John Vitarello, MD, said during a press briefing on reports from the upcoming annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

He and his associates estimated that this use of prescription drugs known to raise blood pressure could be what stands in the way of some 560,000-2.2 million Americans from having their hypertension under control, depending on the exact blood pressure impact that various pressure-increasing drugs have and presuming that half of those on blood pressure increasing agents could stop them and switch to alternative agents, said Dr. Vitarello, a researcher at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

He also highlighted that the study assessed only prescription drugs and did not examine OTC drug use, which may be especially relevant for the many people who regularly take NSAIDs.

“Clinicians should review the prescription and OTC drug use of patients with hypertension and consider stopping drugs that increase blood pressure or switching the patient to alternatives” that are blood pressure neutral, Dr. Vitarello said during the briefing. He cautioned that maintaining hypertensive patients on agents that raise their blood pressure can result in “prescribing cascades” where taking drugs that boost blood pressure results in need for intensified antihypertensive treatment.

An opportunity for NSAID alternatives

“This study hopefully raises awareness that there is a very high use of medications that increase blood pressure, and use of OTC agents could increase the rate even higher” said Eugene Yang, MD, a cardiologist and codirector of the Cardiovascular Wellness and Prevention Program of the University of Washington, Seattle. Substituting for certain antidepressant agents may often not be realistic, but an opportunity exists for reducing NSAID use, a class also linked with an increased risk for bleeding and other adverse effects, Dr. Yang said during the briefing. Minimizing use of NSAIDs including ibuprofen and naproxen use “is something to think about,” he suggested.

“The effect of NSAIDs on blood pressure is not well studied and can vary from person to person” noted Dr. Vitarello, who added that higher NSAID dosages and more prolonged use likely increase the risk for an adverse effect on blood pressure. One reasonable option is to encourage patients to use an alternative class of pain reliever such as acetaminophen.

It remains “a challenge” to discern differences in adverse blood pressure effects, and in all adverse cardiovascular effects among different NSAIDs, said Dr. Yang. Results from “some studies show that certain NSAIDs may be safer, but other studies did not. We need to be very careful using NSAIDs because, on average, they increase blood pressure by about 3 mm Hg. We need to be mindful to try to prescribe alternative agents, like acetaminophen.”

A decade of data from NHANES

The analysis run by Dr. Vitarello and associates used data from 27,599 American adults included in the NHANES during 2009-2018, and focused on the 44% who either had an average blood pressure measurement of at least 130/80 mm Hg or reported having ever been told by a clinician that they had hypertension. The NHANES assessments included the prescription medications taken by each participant. The prevalence of using at least one prescription drug known to raise blood pressure was 24% among women and 14% among men, and 4% of those with hypertension were on two or more pressure-increasing agents.

The researchers based their identification of pressure-increasing prescription drugs on the list included in the 2017 guideline for managing high blood pressure from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association. This list specifies that the antidepressants that raise blood pressure are the monoamine oxidase inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Dr. Vitarello and Dr. Yang had no disclosures.

Nearly half of these American adults had hypertension, and in this subgroup, 18.5% reported using a prescription drug known to increase blood pressure. The most widely used class of agents with this effect was antidepressants, used by 8.7%; followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), used by 6.5%; steroids, 1.9%; estrogens, 1.7%; and several other agents each used by fewer than 1% of the study cohort, John Vitarello, MD, said during a press briefing on reports from the upcoming annual scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology.

He and his associates estimated that this use of prescription drugs known to raise blood pressure could be what stands in the way of some 560,000-2.2 million Americans from having their hypertension under control, depending on the exact blood pressure impact that various pressure-increasing drugs have and presuming that half of those on blood pressure increasing agents could stop them and switch to alternative agents, said Dr. Vitarello, a researcher at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

He also highlighted that the study assessed only prescription drugs and did not examine OTC drug use, which may be especially relevant for the many people who regularly take NSAIDs.

“Clinicians should review the prescription and OTC drug use of patients with hypertension and consider stopping drugs that increase blood pressure or switching the patient to alternatives” that are blood pressure neutral, Dr. Vitarello said during the briefing. He cautioned that maintaining hypertensive patients on agents that raise their blood pressure can result in “prescribing cascades” where taking drugs that boost blood pressure results in need for intensified antihypertensive treatment.

An opportunity for NSAID alternatives

“This study hopefully raises awareness that there is a very high use of medications that increase blood pressure, and use of OTC agents could increase the rate even higher” said Eugene Yang, MD, a cardiologist and codirector of the Cardiovascular Wellness and Prevention Program of the University of Washington, Seattle. Substituting for certain antidepressant agents may often not be realistic, but an opportunity exists for reducing NSAID use, a class also linked with an increased risk for bleeding and other adverse effects, Dr. Yang said during the briefing. Minimizing use of NSAIDs including ibuprofen and naproxen use “is something to think about,” he suggested.

“The effect of NSAIDs on blood pressure is not well studied and can vary from person to person” noted Dr. Vitarello, who added that higher NSAID dosages and more prolonged use likely increase the risk for an adverse effect on blood pressure. One reasonable option is to encourage patients to use an alternative class of pain reliever such as acetaminophen.

It remains “a challenge” to discern differences in adverse blood pressure effects, and in all adverse cardiovascular effects among different NSAIDs, said Dr. Yang. Results from “some studies show that certain NSAIDs may be safer, but other studies did not. We need to be very careful using NSAIDs because, on average, they increase blood pressure by about 3 mm Hg. We need to be mindful to try to prescribe alternative agents, like acetaminophen.”

A decade of data from NHANES

The analysis run by Dr. Vitarello and associates used data from 27,599 American adults included in the NHANES during 2009-2018, and focused on the 44% who either had an average blood pressure measurement of at least 130/80 mm Hg or reported having ever been told by a clinician that they had hypertension. The NHANES assessments included the prescription medications taken by each participant. The prevalence of using at least one prescription drug known to raise blood pressure was 24% among women and 14% among men, and 4% of those with hypertension were on two or more pressure-increasing agents.

The researchers based their identification of pressure-increasing prescription drugs on the list included in the 2017 guideline for managing high blood pressure from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association. This list specifies that the antidepressants that raise blood pressure are the monoamine oxidase inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Dr. Vitarello and Dr. Yang had no disclosures.

FROM ACC 2021

Pediatric cancer survivors at risk for opioid misuse

Survivors of childhood cancers are at increased risk for prescription opioid misuse compared with their peers, a review of a claims database revealed.

Among more than 8,000 patients age 21 or younger who had completed treatment for hematologic, central nervous system, bone, or gonadal cancers, survivors were significantly more likely than were their peers to have an opioid prescription, longer duration of prescription, and higher daily doses of opioids, and to have opioid prescriptions overlapping for a week or more, reported Xu Ji, PhD, of Emory University in Atlanta.

Teenage and young adult patients were at higher risk than were patients younger than 12, and the risk was highest among patients who had been treated for bone malignancies, as well as those who had undergone any hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

“These findings suggest that health care providers who regularly see survivors should explore nonopioid options to help prevent opioid misuse, and screen for potential misuse in those who actually receive opioids,” she said in an oral abstract presented during the annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

“This is a really important topic, and something that’s probably been underinvestigated and underexplored in our patient population,” said session comoderator Sheri Spunt, MD, Endowed Professor of Pediatric Cancer at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Database review

Dr. Ji and colleagues used the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database from 2009 to 2018 to examine prescription opioid use, potential misuse, and substance use disorders in pediatric cancer survivors in the first year after completion of therapy, and to identify factors associated with risk for misuse or substance use disorders. Specifically, the period of interest was the first year after completion of all treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and stem cell transplant (Abstract 2015).

They looked at deidentified records on any opioid prescription and for treatment of any opioid use or substance use disorder (alcohol, psychotherapeutic drugs, marijuana, or illicit drug use disorders).

They defined indicators of potential misuse as either prescriptions for long-acting or extended-release opioids for acute pain conditions; opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions overlapping by a week or more; opioid prescriptions overlapping by a week or more; high daily opioid dosage (prescribed daily dose of 100 or greater morphine milligram equivalent [MME]; and/or opioid dose escalation (an increase of at least 50% in mean MMEs per month twice consecutively within 1 year).

They compared outcomes between a total of 8,635 survivors and 44,175 controls, matched on a 1:5 basis with survivors by age, sex, and region, and continuous enrollment during the 1-year posttherapy period.

In each of three age categories – 0 to 11 years, 12 to 17 years, and 18 years and older – survivors were significantly more likely to have received an opioid prescription, at 15% for the youngest survivors vs. 2% of controls, 25% vs. 8% for 12- to 17-year-olds, and 28% vs. 12% for those 18 and older (P < .01 for all three comparisons).

Survivors were also significantly more likely to have any indicator of potential misuse (1.6% vs. 0.1%, 4.6% vs. 0.5%, and 7.4% vs. 1.2%, respectively, P < .001 for all) and both the youngest and oldest groups (but not 12- to 17-year-olds) were significantly more like to have opioid or substance use disorder (0.4% vs. 0% for 0-11 years, 5.76% vs. 4.2% for 18 years and older, P < .001 for both).

Among patients with any opioid prescription, survivors were significantly more likely than were controls of any age to have indicators for potential misuse. For example, 13% of survivors aged 18 years and older had prescriptions for high opioid doses, compared with 5% of controls, and 12% had prescription overlap, vs. 2%.

Compared with patients with leukemia, patients treated for bone malignancies had a 6% greater risk for having any indicator of misuse, while patients with other malignancies were at slightly lower risk for misuse than those who completed leukemia therapy.

Patients who received any stem cell transplant had an 8.4% greater risk for misuse compared with patients who had surgery only.

Opioids pre- and posttreatment?

“Being someone who takes care of a lot of bone cancer patients, I do see patients with these issues,” Dr. Spunt said.

Audience member Jack H. Staddon, MD, PhD, of the Billings (Montana) Clinic, noted the possibility that opioid use during treatment may have been carried on into the posttreatment period, and asked whether use of narcotics during treatment was an independent risk factor for posttreatment narcotic use or misuse.

The researchers plan to investigate this question in future studies, Dr. Ji replied.

They did not report a study funding source. Dr. Ji and coauthors and Dr. Staddon reported no relevant disclosures.

Survivors of childhood cancers are at increased risk for prescription opioid misuse compared with their peers, a review of a claims database revealed.

Among more than 8,000 patients age 21 or younger who had completed treatment for hematologic, central nervous system, bone, or gonadal cancers, survivors were significantly more likely than were their peers to have an opioid prescription, longer duration of prescription, and higher daily doses of opioids, and to have opioid prescriptions overlapping for a week or more, reported Xu Ji, PhD, of Emory University in Atlanta.

Teenage and young adult patients were at higher risk than were patients younger than 12, and the risk was highest among patients who had been treated for bone malignancies, as well as those who had undergone any hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

“These findings suggest that health care providers who regularly see survivors should explore nonopioid options to help prevent opioid misuse, and screen for potential misuse in those who actually receive opioids,” she said in an oral abstract presented during the annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

“This is a really important topic, and something that’s probably been underinvestigated and underexplored in our patient population,” said session comoderator Sheri Spunt, MD, Endowed Professor of Pediatric Cancer at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Database review

Dr. Ji and colleagues used the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database from 2009 to 2018 to examine prescription opioid use, potential misuse, and substance use disorders in pediatric cancer survivors in the first year after completion of therapy, and to identify factors associated with risk for misuse or substance use disorders. Specifically, the period of interest was the first year after completion of all treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and stem cell transplant (Abstract 2015).

They looked at deidentified records on any opioid prescription and for treatment of any opioid use or substance use disorder (alcohol, psychotherapeutic drugs, marijuana, or illicit drug use disorders).

They defined indicators of potential misuse as either prescriptions for long-acting or extended-release opioids for acute pain conditions; opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions overlapping by a week or more; opioid prescriptions overlapping by a week or more; high daily opioid dosage (prescribed daily dose of 100 or greater morphine milligram equivalent [MME]; and/or opioid dose escalation (an increase of at least 50% in mean MMEs per month twice consecutively within 1 year).

They compared outcomes between a total of 8,635 survivors and 44,175 controls, matched on a 1:5 basis with survivors by age, sex, and region, and continuous enrollment during the 1-year posttherapy period.

In each of three age categories – 0 to 11 years, 12 to 17 years, and 18 years and older – survivors were significantly more likely to have received an opioid prescription, at 15% for the youngest survivors vs. 2% of controls, 25% vs. 8% for 12- to 17-year-olds, and 28% vs. 12% for those 18 and older (P < .01 for all three comparisons).

Survivors were also significantly more likely to have any indicator of potential misuse (1.6% vs. 0.1%, 4.6% vs. 0.5%, and 7.4% vs. 1.2%, respectively, P < .001 for all) and both the youngest and oldest groups (but not 12- to 17-year-olds) were significantly more like to have opioid or substance use disorder (0.4% vs. 0% for 0-11 years, 5.76% vs. 4.2% for 18 years and older, P < .001 for both).

Among patients with any opioid prescription, survivors were significantly more likely than were controls of any age to have indicators for potential misuse. For example, 13% of survivors aged 18 years and older had prescriptions for high opioid doses, compared with 5% of controls, and 12% had prescription overlap, vs. 2%.

Compared with patients with leukemia, patients treated for bone malignancies had a 6% greater risk for having any indicator of misuse, while patients with other malignancies were at slightly lower risk for misuse than those who completed leukemia therapy.

Patients who received any stem cell transplant had an 8.4% greater risk for misuse compared with patients who had surgery only.

Opioids pre- and posttreatment?

“Being someone who takes care of a lot of bone cancer patients, I do see patients with these issues,” Dr. Spunt said.

Audience member Jack H. Staddon, MD, PhD, of the Billings (Montana) Clinic, noted the possibility that opioid use during treatment may have been carried on into the posttreatment period, and asked whether use of narcotics during treatment was an independent risk factor for posttreatment narcotic use or misuse.

The researchers plan to investigate this question in future studies, Dr. Ji replied.

They did not report a study funding source. Dr. Ji and coauthors and Dr. Staddon reported no relevant disclosures.

Survivors of childhood cancers are at increased risk for prescription opioid misuse compared with their peers, a review of a claims database revealed.

Among more than 8,000 patients age 21 or younger who had completed treatment for hematologic, central nervous system, bone, or gonadal cancers, survivors were significantly more likely than were their peers to have an opioid prescription, longer duration of prescription, and higher daily doses of opioids, and to have opioid prescriptions overlapping for a week or more, reported Xu Ji, PhD, of Emory University in Atlanta.

Teenage and young adult patients were at higher risk than were patients younger than 12, and the risk was highest among patients who had been treated for bone malignancies, as well as those who had undergone any hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

“These findings suggest that health care providers who regularly see survivors should explore nonopioid options to help prevent opioid misuse, and screen for potential misuse in those who actually receive opioids,” she said in an oral abstract presented during the annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

“This is a really important topic, and something that’s probably been underinvestigated and underexplored in our patient population,” said session comoderator Sheri Spunt, MD, Endowed Professor of Pediatric Cancer at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Database review

Dr. Ji and colleagues used the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database from 2009 to 2018 to examine prescription opioid use, potential misuse, and substance use disorders in pediatric cancer survivors in the first year after completion of therapy, and to identify factors associated with risk for misuse or substance use disorders. Specifically, the period of interest was the first year after completion of all treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and stem cell transplant (Abstract 2015).

They looked at deidentified records on any opioid prescription and for treatment of any opioid use or substance use disorder (alcohol, psychotherapeutic drugs, marijuana, or illicit drug use disorders).

They defined indicators of potential misuse as either prescriptions for long-acting or extended-release opioids for acute pain conditions; opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions overlapping by a week or more; opioid prescriptions overlapping by a week or more; high daily opioid dosage (prescribed daily dose of 100 or greater morphine milligram equivalent [MME]; and/or opioid dose escalation (an increase of at least 50% in mean MMEs per month twice consecutively within 1 year).

They compared outcomes between a total of 8,635 survivors and 44,175 controls, matched on a 1:5 basis with survivors by age, sex, and region, and continuous enrollment during the 1-year posttherapy period.

In each of three age categories – 0 to 11 years, 12 to 17 years, and 18 years and older – survivors were significantly more likely to have received an opioid prescription, at 15% for the youngest survivors vs. 2% of controls, 25% vs. 8% for 12- to 17-year-olds, and 28% vs. 12% for those 18 and older (P < .01 for all three comparisons).

Survivors were also significantly more likely to have any indicator of potential misuse (1.6% vs. 0.1%, 4.6% vs. 0.5%, and 7.4% vs. 1.2%, respectively, P < .001 for all) and both the youngest and oldest groups (but not 12- to 17-year-olds) were significantly more like to have opioid or substance use disorder (0.4% vs. 0% for 0-11 years, 5.76% vs. 4.2% for 18 years and older, P < .001 for both).

Among patients with any opioid prescription, survivors were significantly more likely than were controls of any age to have indicators for potential misuse. For example, 13% of survivors aged 18 years and older had prescriptions for high opioid doses, compared with 5% of controls, and 12% had prescription overlap, vs. 2%.

Compared with patients with leukemia, patients treated for bone malignancies had a 6% greater risk for having any indicator of misuse, while patients with other malignancies were at slightly lower risk for misuse than those who completed leukemia therapy.

Patients who received any stem cell transplant had an 8.4% greater risk for misuse compared with patients who had surgery only.

Opioids pre- and posttreatment?

“Being someone who takes care of a lot of bone cancer patients, I do see patients with these issues,” Dr. Spunt said.

Audience member Jack H. Staddon, MD, PhD, of the Billings (Montana) Clinic, noted the possibility that opioid use during treatment may have been carried on into the posttreatment period, and asked whether use of narcotics during treatment was an independent risk factor for posttreatment narcotic use or misuse.

The researchers plan to investigate this question in future studies, Dr. Ji replied.

They did not report a study funding source. Dr. Ji and coauthors and Dr. Staddon reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM 2021 ASPHO CONFERENCE

High variability found in studies assessing hemophilia-related pain

Chronic pain is a common condition among people with hemophilia and is associated with joint deterioration because of repeated joint bleeds. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the prevalence of chronic pain because of hemophilia and to analyze its interference in the lives of patients, according to Ana Cristina Paredes, a PhD student at the University of Minho, Braga, Portugal, and colleagues.

The manuscripts included in the study, which was published online in the Journal of Pain, were mostly observational, cross-sectional studies and one prospective investigation, published between 2009 and 2019.

The issue of pain is particularly important among people with hemophilia, as many adult patients suffer from distinct degrees of arthropathy and associated chronic pain, due to the lifelong occurrence of hemarthrosis, the authors noted. In an important distinction, according to the authors, people with hemophilia may therefore experience both acute pain during bleeds and chronic pain caused by joint deterioration. Acute pain ceases with the resolution of the bleeding episode, but the chronic pain is significantly more challenging, since it persists in time and may trigger changes in the nervous system, leading to peripheral or central sensitization.

Data in the assessed studies were collected from a variety of sources: hemophilia centers, online surveys, by mail, or through a national database, with return rates ranging from 29.2% to 98%. Overall, these studies comprised 4,772 adults, with individual sample sizes ranging from 21 to 2,253 patients, the authors added.

Conflicting results

Overall, there was a widely varying prevalence of hemophilia-related chronic pain reported across studies. Additionally, methodologies and sample characteristics varied widely. The meta-analyses revealed high heterogeneity between studies, and, therefore, pooled prevalence estimates values must be interpreted with caution, the authors stated.

All of the 11 selected studies included for meta-analysis and review reported on the prevalence of chronic pain caused by hemophilia. Chronic pain was assessed using direct questions developed by the authors in eight studies and using the European Haemophilia Therapy Standardization Board definition in three studies. The prevalence for global samples ranged widely from 17% to 84%.

Although there was high heterogeneity, the random-effects meta-analysis including all studies demonstrated a pooled prevalence of 46% of patients reporting chronic pain. Subgroup analyses of studies including all disease severities (mild, moderate, and severe; seven studies) revealed a pooled prevalence of 48%, but also with high heterogeneity. Looking at severe patients only (six studies), the chronic pain prevalence ranged from 33% to 86.4%, with a pooled prevalence of 53% and high heterogeneity, the authors added.

The wide disparity of the chronic pain prevalence seen across the studies is likely because of the fact that some investigations inquired about pain without distinguishing between acute (hemarthrosis-related) or chronic (arthropathy-related) pain, and without clarifying if the only focus is pain caused by hemophilia, or including all causes of pain complaints, according to the researchers.

“Concerning hemophilia-related chronic pain interference, it is striking that the existing literature does not distinguish between the impact of acute or chronic pain. Such a distinction is needed and should be made in future studies to ensure accurate accounts of hemophilia-related pain and to fully understand its interference according to the type of pain (acute vs. chronic). This information is relevant to promote targeted and effective treatment approaches,” the researchers concluded.

The research was supported by a Novo Nordisk HERO Research Grant 2015, the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, and the Foundation for Science and Technology in Portugal. The authors declared they had no conflicts of interest.

Chronic pain is a common condition among people with hemophilia and is associated with joint deterioration because of repeated joint bleeds. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the prevalence of chronic pain because of hemophilia and to analyze its interference in the lives of patients, according to Ana Cristina Paredes, a PhD student at the University of Minho, Braga, Portugal, and colleagues.

The manuscripts included in the study, which was published online in the Journal of Pain, were mostly observational, cross-sectional studies and one prospective investigation, published between 2009 and 2019.

The issue of pain is particularly important among people with hemophilia, as many adult patients suffer from distinct degrees of arthropathy and associated chronic pain, due to the lifelong occurrence of hemarthrosis, the authors noted. In an important distinction, according to the authors, people with hemophilia may therefore experience both acute pain during bleeds and chronic pain caused by joint deterioration. Acute pain ceases with the resolution of the bleeding episode, but the chronic pain is significantly more challenging, since it persists in time and may trigger changes in the nervous system, leading to peripheral or central sensitization.

Data in the assessed studies were collected from a variety of sources: hemophilia centers, online surveys, by mail, or through a national database, with return rates ranging from 29.2% to 98%. Overall, these studies comprised 4,772 adults, with individual sample sizes ranging from 21 to 2,253 patients, the authors added.

Conflicting results

Overall, there was a widely varying prevalence of hemophilia-related chronic pain reported across studies. Additionally, methodologies and sample characteristics varied widely. The meta-analyses revealed high heterogeneity between studies, and, therefore, pooled prevalence estimates values must be interpreted with caution, the authors stated.

All of the 11 selected studies included for meta-analysis and review reported on the prevalence of chronic pain caused by hemophilia. Chronic pain was assessed using direct questions developed by the authors in eight studies and using the European Haemophilia Therapy Standardization Board definition in three studies. The prevalence for global samples ranged widely from 17% to 84%.

Although there was high heterogeneity, the random-effects meta-analysis including all studies demonstrated a pooled prevalence of 46% of patients reporting chronic pain. Subgroup analyses of studies including all disease severities (mild, moderate, and severe; seven studies) revealed a pooled prevalence of 48%, but also with high heterogeneity. Looking at severe patients only (six studies), the chronic pain prevalence ranged from 33% to 86.4%, with a pooled prevalence of 53% and high heterogeneity, the authors added.

The wide disparity of the chronic pain prevalence seen across the studies is likely because of the fact that some investigations inquired about pain without distinguishing between acute (hemarthrosis-related) or chronic (arthropathy-related) pain, and without clarifying if the only focus is pain caused by hemophilia, or including all causes of pain complaints, according to the researchers.

“Concerning hemophilia-related chronic pain interference, it is striking that the existing literature does not distinguish between the impact of acute or chronic pain. Such a distinction is needed and should be made in future studies to ensure accurate accounts of hemophilia-related pain and to fully understand its interference according to the type of pain (acute vs. chronic). This information is relevant to promote targeted and effective treatment approaches,” the researchers concluded.

The research was supported by a Novo Nordisk HERO Research Grant 2015, the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, and the Foundation for Science and Technology in Portugal. The authors declared they had no conflicts of interest.

Chronic pain is a common condition among people with hemophilia and is associated with joint deterioration because of repeated joint bleeds. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the prevalence of chronic pain because of hemophilia and to analyze its interference in the lives of patients, according to Ana Cristina Paredes, a PhD student at the University of Minho, Braga, Portugal, and colleagues.

The manuscripts included in the study, which was published online in the Journal of Pain, were mostly observational, cross-sectional studies and one prospective investigation, published between 2009 and 2019.

The issue of pain is particularly important among people with hemophilia, as many adult patients suffer from distinct degrees of arthropathy and associated chronic pain, due to the lifelong occurrence of hemarthrosis, the authors noted. In an important distinction, according to the authors, people with hemophilia may therefore experience both acute pain during bleeds and chronic pain caused by joint deterioration. Acute pain ceases with the resolution of the bleeding episode, but the chronic pain is significantly more challenging, since it persists in time and may trigger changes in the nervous system, leading to peripheral or central sensitization.

Data in the assessed studies were collected from a variety of sources: hemophilia centers, online surveys, by mail, or through a national database, with return rates ranging from 29.2% to 98%. Overall, these studies comprised 4,772 adults, with individual sample sizes ranging from 21 to 2,253 patients, the authors added.

Conflicting results

Overall, there was a widely varying prevalence of hemophilia-related chronic pain reported across studies. Additionally, methodologies and sample characteristics varied widely. The meta-analyses revealed high heterogeneity between studies, and, therefore, pooled prevalence estimates values must be interpreted with caution, the authors stated.

All of the 11 selected studies included for meta-analysis and review reported on the prevalence of chronic pain caused by hemophilia. Chronic pain was assessed using direct questions developed by the authors in eight studies and using the European Haemophilia Therapy Standardization Board definition in three studies. The prevalence for global samples ranged widely from 17% to 84%.

Although there was high heterogeneity, the random-effects meta-analysis including all studies demonstrated a pooled prevalence of 46% of patients reporting chronic pain. Subgroup analyses of studies including all disease severities (mild, moderate, and severe; seven studies) revealed a pooled prevalence of 48%, but also with high heterogeneity. Looking at severe patients only (six studies), the chronic pain prevalence ranged from 33% to 86.4%, with a pooled prevalence of 53% and high heterogeneity, the authors added.

The wide disparity of the chronic pain prevalence seen across the studies is likely because of the fact that some investigations inquired about pain without distinguishing between acute (hemarthrosis-related) or chronic (arthropathy-related) pain, and without clarifying if the only focus is pain caused by hemophilia, or including all causes of pain complaints, according to the researchers.

“Concerning hemophilia-related chronic pain interference, it is striking that the existing literature does not distinguish between the impact of acute or chronic pain. Such a distinction is needed and should be made in future studies to ensure accurate accounts of hemophilia-related pain and to fully understand its interference according to the type of pain (acute vs. chronic). This information is relevant to promote targeted and effective treatment approaches,” the researchers concluded.

The research was supported by a Novo Nordisk HERO Research Grant 2015, the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, and the Foundation for Science and Technology in Portugal. The authors declared they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PAIN

FDA OKs higher-dose naloxone nasal spray for opioid overdose

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a higher-dose naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Kloxxado) for the emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose, as manifested by respiratory and/or central nervous system depression.

Kloxxado delivers 8 mg of naloxone into the nasal cavity, which is twice as much as the 4 mg of naloxone contained in Narcan nasal spray.

When administered quickly, naloxone can counter opioid overdose effects, usually within minutes. A higher dose of naloxone provides an additional option for the treatment of opioid overdoses, the FDA said in a news release.

“This approval meets another critical need in combating opioid overdose,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

“Addressing the opioid crisis is a top priority for the FDA, and we will continue our efforts to increase access to naloxone and place this important medicine in the hands of those who need it most,” said Dr. Cavazzoni.

In a company news release announcing the approval, manufacturer Hikma Pharmaceuticals noted that a recent survey of community organizations in which the 4-mg naloxone nasal spray had been distributed showed that for 34% of attempted reversals, two or more doses of naloxone were used.

A separate study found that the percentage of overdose-related emergency medical service calls in the United States that led to the administration of multiple doses of naloxone increased to 21% during the period of 2013-2016, which represents a 43% increase over 4 years.

“The approval of Kloxxado is an important step in providing patients, friends, and family members – as well as the public health community – with an important new option for treating opioid overdose,” Brian Hoffmann, president of Hikma Generics, said in the release.

The FDA approved Kloxxado through the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway, which allows the agency to refer to previous findings of safety and efficacy for an already-approved product, as well as to review findings from further studies of the product.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a higher-dose naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Kloxxado) for the emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose, as manifested by respiratory and/or central nervous system depression.

Kloxxado delivers 8 mg of naloxone into the nasal cavity, which is twice as much as the 4 mg of naloxone contained in Narcan nasal spray.

When administered quickly, naloxone can counter opioid overdose effects, usually within minutes. A higher dose of naloxone provides an additional option for the treatment of opioid overdoses, the FDA said in a news release.

“This approval meets another critical need in combating opioid overdose,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

“Addressing the opioid crisis is a top priority for the FDA, and we will continue our efforts to increase access to naloxone and place this important medicine in the hands of those who need it most,” said Dr. Cavazzoni.

In a company news release announcing the approval, manufacturer Hikma Pharmaceuticals noted that a recent survey of community organizations in which the 4-mg naloxone nasal spray had been distributed showed that for 34% of attempted reversals, two or more doses of naloxone were used.

A separate study found that the percentage of overdose-related emergency medical service calls in the United States that led to the administration of multiple doses of naloxone increased to 21% during the period of 2013-2016, which represents a 43% increase over 4 years.

“The approval of Kloxxado is an important step in providing patients, friends, and family members – as well as the public health community – with an important new option for treating opioid overdose,” Brian Hoffmann, president of Hikma Generics, said in the release.

The FDA approved Kloxxado through the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway, which allows the agency to refer to previous findings of safety and efficacy for an already-approved product, as well as to review findings from further studies of the product.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a higher-dose naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray (Kloxxado) for the emergency treatment of known or suspected opioid overdose, as manifested by respiratory and/or central nervous system depression.

Kloxxado delivers 8 mg of naloxone into the nasal cavity, which is twice as much as the 4 mg of naloxone contained in Narcan nasal spray.

When administered quickly, naloxone can counter opioid overdose effects, usually within minutes. A higher dose of naloxone provides an additional option for the treatment of opioid overdoses, the FDA said in a news release.

“This approval meets another critical need in combating opioid overdose,” Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD, director, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the release.

“Addressing the opioid crisis is a top priority for the FDA, and we will continue our efforts to increase access to naloxone and place this important medicine in the hands of those who need it most,” said Dr. Cavazzoni.

In a company news release announcing the approval, manufacturer Hikma Pharmaceuticals noted that a recent survey of community organizations in which the 4-mg naloxone nasal spray had been distributed showed that for 34% of attempted reversals, two or more doses of naloxone were used.

A separate study found that the percentage of overdose-related emergency medical service calls in the United States that led to the administration of multiple doses of naloxone increased to 21% during the period of 2013-2016, which represents a 43% increase over 4 years.

“The approval of Kloxxado is an important step in providing patients, friends, and family members – as well as the public health community – with an important new option for treating opioid overdose,” Brian Hoffmann, president of Hikma Generics, said in the release.

The FDA approved Kloxxado through the 505(b)(2) regulatory pathway, which allows the agency to refer to previous findings of safety and efficacy for an already-approved product, as well as to review findings from further studies of the product.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The cloudy role of cannabis as a neuropsychiatric treatment

Although the healing properties of cannabis have been touted for millennia, research into its potential neuropsychiatric applications truly began to take off in the 1990s following the discovery of the cannabinoid system in the brain. This led to speculation that cannabis could play a therapeutic role in regulating dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters and offer a new means of treating various ailments.

At the same time, efforts to liberalize marijuana laws have successfully played out in several nations, including the United States, where, as of April 29, 36 states provide some access to cannabis. These dual tracks – medical and political – have made cannabis an increasingly accepted part of the cultural fabric.

Yet with this development has come a new quandary for clinicians. Medical cannabis has been made widely available to patients and has largely outpaced the clinical evidence, leaving it unclear how and for which indications it should be used.

The many forms of medical cannabis

Cannabis is a genus of plants that includes marijuana (Cannabis sativa) and hemp. These plants contain over 100 compounds, including terpenes, flavonoids, and – most importantly for medicinal applications – cannabinoids.

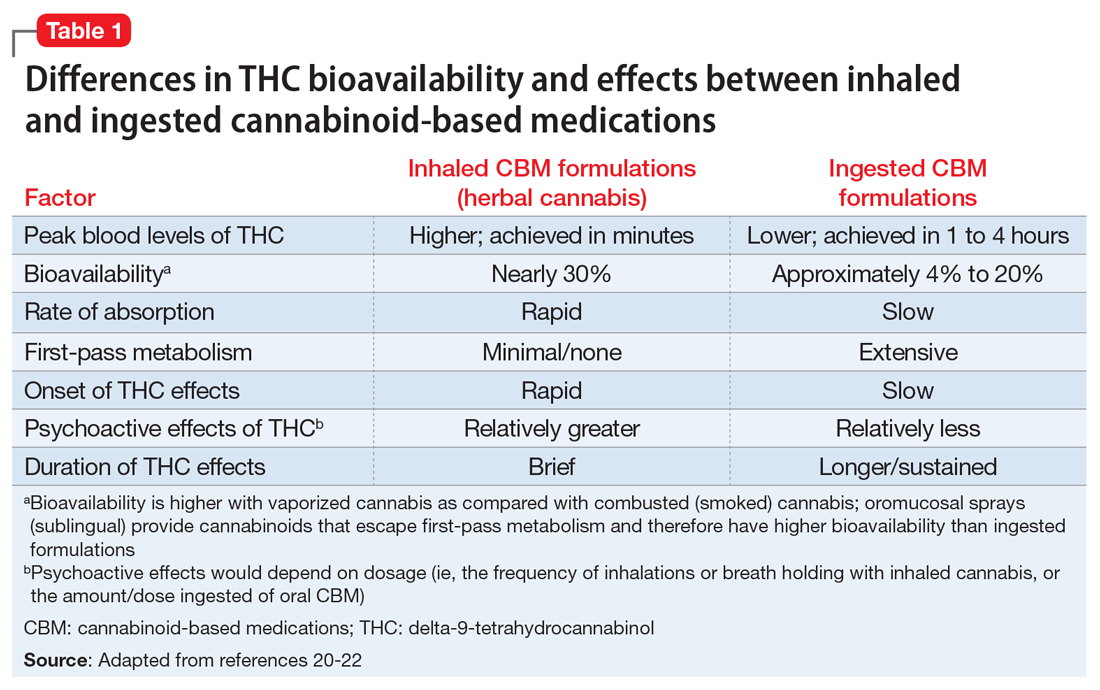

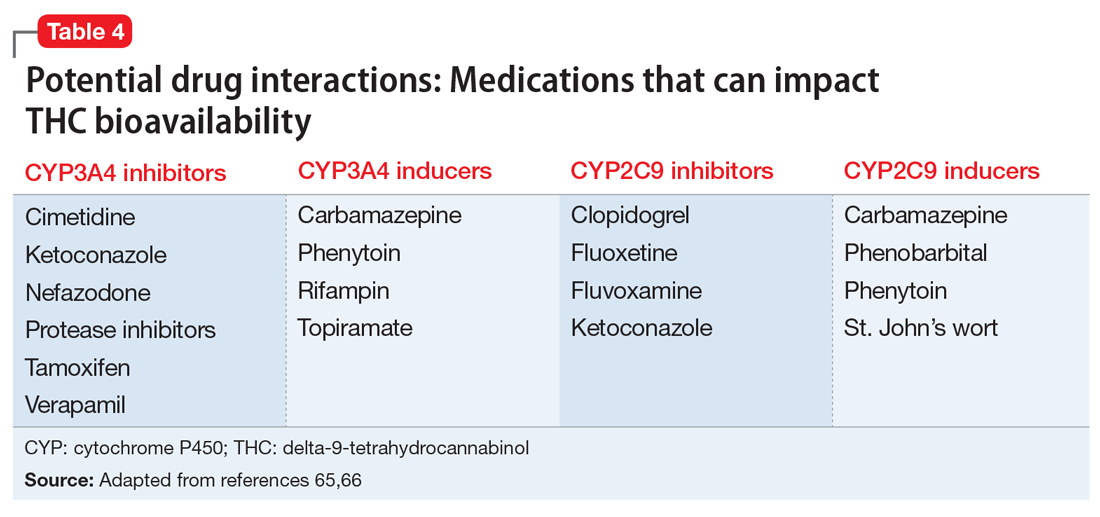

The most abundant cannabinoid in marijuana is the psychotropic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which imparts the “high” sensation. The next most abundant cannabinoid is cannabidiol (CBD), which is the nonpsychotropic. THC and CBD are the most extensively studied cannabinoids, together and in isolation. Evidence suggests that other cannabinoids and terpenoids may also hold medical promise and that cannabis’ various compounds can work synergistically to produce a so-called entourage effect.

Patients walking into a typical medical cannabis dispensary will be faced with several plant-derived and synthetic options, which can differ considerably in terms of the ratios and amounts of THC and CBD they contain, as well in how they are consumed (i.e., via smoke, vapor, ingestion, topical administration, or oromucosal spray), all of which can alter their effects. Further complicating matters is the varying level of oversight each state and country has in how and whether they test for and accurately label products’ potency, cannabinoid content, and possible impurities.

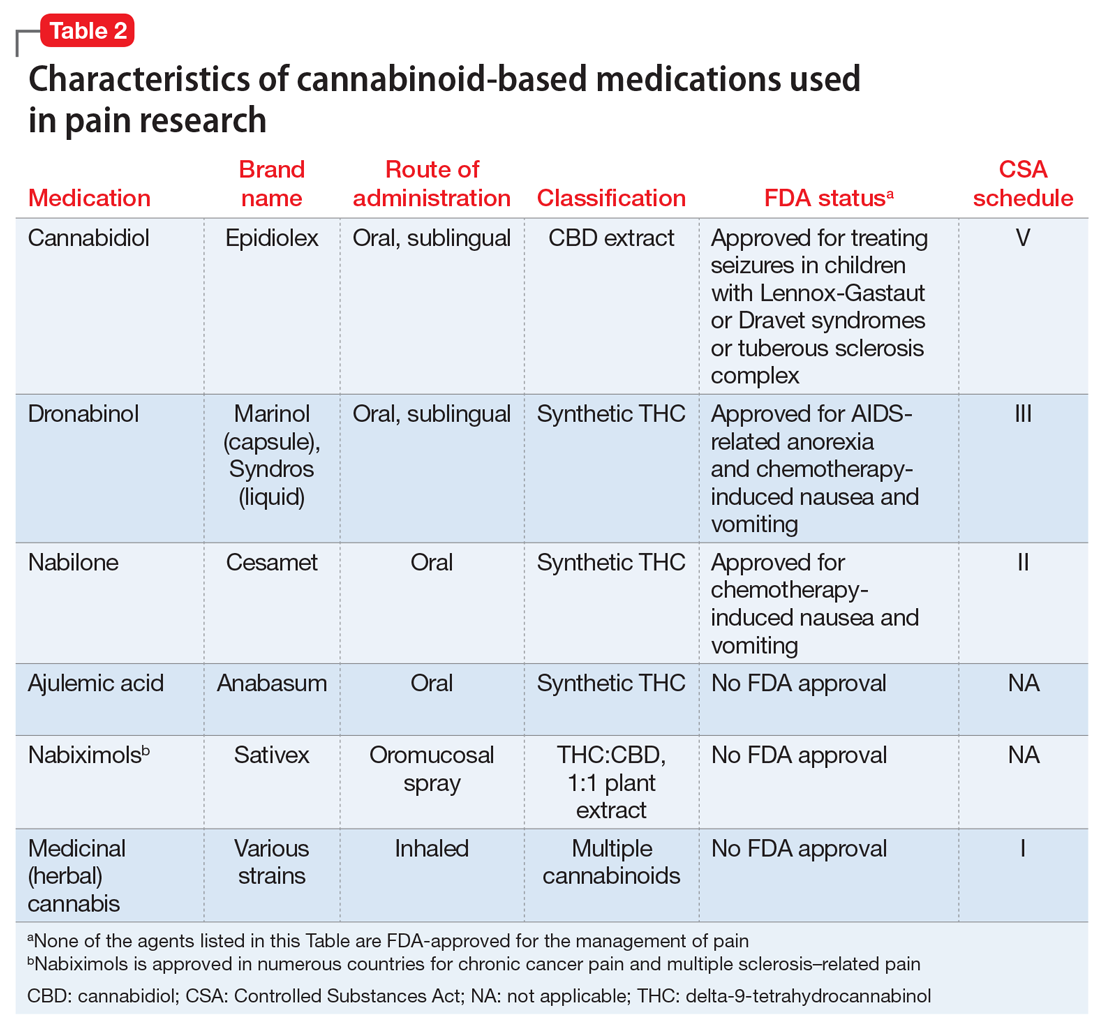

Medically authorized, prescription cannabis products go through an official regulatory review process, and indications/contraindications have been established for them. To date, the Food and Drug Administration has approved one cannabis-derived drug product – Epidiolex (purified CBD) – for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients aged 2 years and older. The FDA has also approved three synthetic cannabis-related drug products – Marinol, Syndros (or dronabinol, created from synthetic THC), and Cesamet (or nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid similar to THC) – all of which are indicated for treatment-related nausea and anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients.

Surveys of medical cannabis consumers indicate that most people cannot distinguish between THC and CBD, so the first role that physicians find themselves in when recommending this treatment may be in helping patients navigate the volume of options.

Promising treatment for pain

Chronic pain is the leading reason patients seek out medical cannabis. It is also the indication that most researchers agree has the strongest evidence to support its use.

“In my mind, the most promising immediate use for medical cannabis is with THC for pain,” Diana M. Martinez, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, who specializes in addiction research, said in a recent MDedge podcast. “THC could be added to the armamentarium of pain medications that we use today.”

In a 2015 systematic literature review, researchers assessed 28 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of the use of cannabinoids for chronic pain. They reported that a variety of formulations resulted in at least a 30% reduction in the odds of pain, compared with placebo. A meta-analysis of five RCTs involving patients with neuropathic pain found a 30% reduction in pain over placebo with inhaled, vaporized cannabis. Varying results have been reported in additional studies for this indication. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that there was a substantial body of evidence that cannabis is an effective treatment for chronic pain in adults.

The ongoing opioid epidemic has lent these results additional relevance.

Seeing this firsthand has caused Mark Steven Wallace, MD, a pain management specialist and chair of the division of pain medicine at the University of California San Diego Health, to reconsider offering cannabis to his patients.

“I think it’s probably more efficacious, just from my personal experience, and it’s a much lower risk of abuse and dependence than the opioids,” he said.

Dr. Wallace advised that clinicians who treat pain consider the ratios of cannabinoids.

“This is anecdotal, but we do find that with the combination of the two, CBD reduces the psychoactive effects of the THC. The ratios we use during the daytime range around 20 mg of CBD to 1 mg of THC,” he said.

In a recent secondary analysis of an RCT involving patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Dr. Wallace and colleagues showed that THC’s effects appear to reverse themselves at a certain level.

“As the THC level goes up, the pain reduces until you reach about 16 ng/mL; then it starts going in the opposite direction, and pain will start to increase,” he said. “Even recreational cannabis users have reported that they avoid high doses because it’s very aversive. Using cannabis is all about, start low and go slow.”

A mixed bag for neurologic indications

There are relatively limited data on the use of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, and results have varied. For uses other than pain management, the evidence that does exist is strongest regarding epilepsy, said Daniel Freedman, DO, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Texas at Austin. He noted “multiple high-quality RCTs showing that pharmaceutical-grade CBD can reduce seizures associated with two particular epilepsy syndromes: Dravet Syndrome and Lennox Gastaut.”

These findings led to the FDA’s 2018 approval of Epidiolex for these syndromes. In earlier years, interest in CBD for pediatric seizures was largely driven by anecdotal parental reports of its benefits. NASEM’s 2017 overview on medical cannabis found evidence from subsequent RCTs in this indication to be insufficient. Clinicians who prescribe CBD for this indication must be vigilant because it can interact with several commonly used antiepileptic drugs.

Cannabinoid treatments have also shown success in alleviating muscle spasticity resulting from multiple sclerosis, most prominently in the form of nabiximols (Sativex), a standardized oralmucosal spray containing approximately equal quantities of THC and CBD. Nabiximols is approved in Europe but not in the United States. Moderate evidence supports the efficacy of these and other treatments over placebo in reducing muscle spasticity. Patient ratings of its effects tend to be higher than clinician assessment.

Parkinson’s disease has not yet been approved as an indication for treatment with cannabis or cannabinoids, yet a growing body of preclinical data suggests these could influence the dopaminergic system, said Carsten Buhmann, MD, from the department of neurology at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

“In general, cannabinoids modulate basal-ganglia function on two levels which are especially relevant in Parkinson’s disease, i.e., the glutamatergic/dopaminergic synaptic neurotransmission and the corticostriatal plasticity,” he said. “Furthermore, activation of the endocannabinoid system might induce neuroprotective effects related to direct receptor-independent mechanisms, activation of anti-inflammatory cascades in glial cells via the cannabinoid receptor type 2, and antiglutamatergic antiexcitotoxic properties.”

Dr. Buhmann said that currently, clinical evidence is scarce, consisting of only four double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs involving 49 patients. Various cannabinoids and methods of administering treatment were employed. Improvement was only observed in one of these RCTs, which found that the cannabinoid receptor agonist nabilone significantly reduced levodopa-induced dyskinesia for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Subjective data support a beneficial effect. In a nationwide survey of 1,348 respondents conducted by Dr. Buhmann and colleagues, the majority of medical cannabis users reported that it improved their symptoms (54% with oral CBD and 68% with inhaled THC-containing cannabis).

NASEM concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, including Tourette syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease, dystonia, or dementia. A 2020 position statement from the American Academy of Neurology cited the lack of sufficient peer-reviewed research as the reason it could not currently support the use of cannabis for neurologic disorders.

Yet, according to Dr. Freedman, who served as a coauthor of the AAN position statement, this hasn’t stymied research interest in the topic. He’s seen a substantial uptick in studies of CBD over the past 2 years. “The body of evidence grows, but I still see many claims being made without evidence. And no one seems to care about all the negative trials.”

Cannabis as a treatment for, and cause of, psychiatric disorders

Mental health problems – such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD – are among the most common reasons patients seek out medical cannabis. There is an understandable interest in using cannabis and cannabinoids to treat psychiatric disorders. Preclinical studies suggest that the endocannabinoid system plays a prominent role in modulating feelings of anxiety, mood, and fear. As with opioids and chronic pain management, there is hope that medical cannabis may provide a means of reducing prescription anxiolytics and their associated risks.

The authors of the first systematic review (BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 16;20[1]:24) of the use of medical cannabis for major psychiatric disorders noted that the current evidence was “encouraging, albeit embryonic.”

Meta-analyses have indicated a small but positive association between cannabis use and anxiety, although this may reflect the fact that patients with anxiety sought out this treatment. Given the risks for substance use disorders among patients with anxiety, CBD may present a more viable option. Positive results have been shown as treatment for generalized social anxiety disorder.

Limited but encouraging results have also been reported regarding the alleviation of PTSD symptoms with both cannabis and CBD, although the body of high-quality evidence hasn’t notably progressed since 2017, when NASEM declared that the evidence was insufficient. Supportive evidence is similarly lacking regarding the treatment of depression. Longitudinal studies suggest that cannabis use, particularly heavy use, may increase the risk of developing this disorder. Because THC is psychoactive, it is advised that it be avoided by patients at risk for psychotic disorders. However, CBD has yielded limited benefits for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and for young people at risk for psychosis.

The use of medical cannabis for psychiatric conditions requires a complex balancing act, inasmuch as these treatments may exacerbate the very problems they are intended to alleviate.

Marta Di Forti, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatric research at Kings College London, has been at the forefront of determining the mental health risks of continued cannabis use. In 2019, Dr. Di Forti developed the first and only Cannabis Clinic for Patients With Psychosis in London where she and her colleagues have continued to elucidate this connection.

Dr. Di Forti and colleagues have linked daily cannabis use to an increase in the risk of experiencing psychotic disorder, compared with never using it. That risk was further increased among users of high-potency cannabis (≥10% THC). The latter finding has troubling implications, because concentrations of THC have steadily risen since 1970. By contrast, CBD concentrations have remained generally stable. High-potency cannabis products are common in both recreational and medicinal settings.

“For somebody prescribing medicinal cannabis that has a ≥10% concentration of THC, I’d be particularly wary of the risk of psychosis,” said Dr. Di Forti. “If you’re expecting people to use a high content of THC daily to medicate pain or a chronic condition, you even more so need to be aware that this is a potential side effect.”

Dr. Di Forti noted that her findings come from a cohort of recreational users, most of whom were aged 18-35 years.

“There have actually not been studies developed from collecting data in this area from groups specifically using cannabis for medicinal rather than recreational purposes,” she said.

She added that she personally has no concerns about the use of medical cannabis but wants clinicians to be aware of the risk for psychosis, to structure their patient conversations to identify risk factors or family histories of psychosis, and to become knowledgeable in detecting the often subtle signs of its initial onset.

When cannabis-associated psychosis occurs, Dr. Di Forti said it is primarily treated with conventional means, such as antipsychotics and therapeutic interventions and by refraining from using cannabis. Achieving the latter goal can be a challenge for patients who are daily users of high-potency cannabis. Currently, there are no treatment options such as those offered to patients withdrawing from the use of alcohol or opioids. Dr. Di Forti and colleagues are currently researching a solution to that problem through the use of another medical cannabis, the oromucosal spray Sativex, which has been approved in the European Union.

The regulatory obstacles to clarifying cannabis’ role in medicine

That currently there is limited or no evidence to support the use of medical cannabis for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions points to the inherent difficulties in conducting high-level research in this area.

“There’s a tremendous shortage of reliable data, largely due to regulatory barriers,” said Dr. Martinez.

Since 1970, cannabis has been listed as a Schedule I drug that is illegal to prescribe (the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 removed hemp from such restrictions). The FDA has issued guidance for researchers who wish to investigate treatments using Cannabis sativa or its derivatives in which the THC content is greater than 0.3%. Such research requires regular interactions with several federal agencies, including the Drug Enforcement Administration.

“It’s impossible to do multicenter RCTs with large numbers of patients, because you can’t transport cannabis across state lines,” said Dr. Wallace.

Regulatory restrictions regarding medical cannabis vary considerably throughout the world (the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction provides a useful breakdown of this on their website). The lack of consistency in regulatory oversight acts as an impediment for conducting large-scale international multicenter studies on the topic.

Dr. Buhmann noted that, in Germany, cannabis has been broadly approved for treatment-resistant conditions with severe symptoms that impair quality of life. In addition, it is easy to be reimbursed for the use of cannabis as a medical treatment. These factors serve as disincentives for the funding of high-quality studies.

“It’s likely that no pharmaceutical company will do an expensive RCT to get an approval for Parkinson’s disease because it is already possible to prescribe medical cannabis of any type of THC-containing cannabinoid, dose, or route of application,” Dr. Buhmann said.

In the face of such restrictions and barriers, researchers are turning to ambitious real-world data projects to better understand medical cannabis’ efficacy and safety. A notable example is ProjectTwenty21, which is supported by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The project is collecting outcomes of the use of medical cannabis among 20,000 U.K. patients whose conventional treatments of chronic pain, anxiety disorder, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, PTSD, substance use disorder, and Tourette syndrome failed.

Dr. Freedman noted that the continued lack of high-quality data creates a void that commercial interests fill with unfounded claims.

“The danger is that patients might abandon a medication or intervention backed by robust science in favor of something without any science or evidence behind it,” he said. “There is no reason not to expect the same level of data for claims about cannabis products as we would expect from pharmaceutical products.”

Getting to that point, however, will require that the authorities governing clinical trials begin to view cannabis as the research community does, as a possible treatment with potential value, rather than as an illicit drug that needs to be tamped down.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although the healing properties of cannabis have been touted for millennia, research into its potential neuropsychiatric applications truly began to take off in the 1990s following the discovery of the cannabinoid system in the brain. This led to speculation that cannabis could play a therapeutic role in regulating dopamine, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters and offer a new means of treating various ailments.

At the same time, efforts to liberalize marijuana laws have successfully played out in several nations, including the United States, where, as of April 29, 36 states provide some access to cannabis. These dual tracks – medical and political – have made cannabis an increasingly accepted part of the cultural fabric.

Yet with this development has come a new quandary for clinicians. Medical cannabis has been made widely available to patients and has largely outpaced the clinical evidence, leaving it unclear how and for which indications it should be used.

The many forms of medical cannabis

Cannabis is a genus of plants that includes marijuana (Cannabis sativa) and hemp. These plants contain over 100 compounds, including terpenes, flavonoids, and – most importantly for medicinal applications – cannabinoids.

The most abundant cannabinoid in marijuana is the psychotropic delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which imparts the “high” sensation. The next most abundant cannabinoid is cannabidiol (CBD), which is the nonpsychotropic. THC and CBD are the most extensively studied cannabinoids, together and in isolation. Evidence suggests that other cannabinoids and terpenoids may also hold medical promise and that cannabis’ various compounds can work synergistically to produce a so-called entourage effect.

Patients walking into a typical medical cannabis dispensary will be faced with several plant-derived and synthetic options, which can differ considerably in terms of the ratios and amounts of THC and CBD they contain, as well in how they are consumed (i.e., via smoke, vapor, ingestion, topical administration, or oromucosal spray), all of which can alter their effects. Further complicating matters is the varying level of oversight each state and country has in how and whether they test for and accurately label products’ potency, cannabinoid content, and possible impurities.

Medically authorized, prescription cannabis products go through an official regulatory review process, and indications/contraindications have been established for them. To date, the Food and Drug Administration has approved one cannabis-derived drug product – Epidiolex (purified CBD) – for the treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome or Dravet syndrome in patients aged 2 years and older. The FDA has also approved three synthetic cannabis-related drug products – Marinol, Syndros (or dronabinol, created from synthetic THC), and Cesamet (or nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid similar to THC) – all of which are indicated for treatment-related nausea and anorexia associated with weight loss in AIDS patients.

Surveys of medical cannabis consumers indicate that most people cannot distinguish between THC and CBD, so the first role that physicians find themselves in when recommending this treatment may be in helping patients navigate the volume of options.

Promising treatment for pain

Chronic pain is the leading reason patients seek out medical cannabis. It is also the indication that most researchers agree has the strongest evidence to support its use.

“In my mind, the most promising immediate use for medical cannabis is with THC for pain,” Diana M. Martinez, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, who specializes in addiction research, said in a recent MDedge podcast. “THC could be added to the armamentarium of pain medications that we use today.”

In a 2015 systematic literature review, researchers assessed 28 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of the use of cannabinoids for chronic pain. They reported that a variety of formulations resulted in at least a 30% reduction in the odds of pain, compared with placebo. A meta-analysis of five RCTs involving patients with neuropathic pain found a 30% reduction in pain over placebo with inhaled, vaporized cannabis. Varying results have been reported in additional studies for this indication. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that there was a substantial body of evidence that cannabis is an effective treatment for chronic pain in adults.

The ongoing opioid epidemic has lent these results additional relevance.

Seeing this firsthand has caused Mark Steven Wallace, MD, a pain management specialist and chair of the division of pain medicine at the University of California San Diego Health, to reconsider offering cannabis to his patients.

“I think it’s probably more efficacious, just from my personal experience, and it’s a much lower risk of abuse and dependence than the opioids,” he said.

Dr. Wallace advised that clinicians who treat pain consider the ratios of cannabinoids.

“This is anecdotal, but we do find that with the combination of the two, CBD reduces the psychoactive effects of the THC. The ratios we use during the daytime range around 20 mg of CBD to 1 mg of THC,” he said.

In a recent secondary analysis of an RCT involving patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Dr. Wallace and colleagues showed that THC’s effects appear to reverse themselves at a certain level.

“As the THC level goes up, the pain reduces until you reach about 16 ng/mL; then it starts going in the opposite direction, and pain will start to increase,” he said. “Even recreational cannabis users have reported that they avoid high doses because it’s very aversive. Using cannabis is all about, start low and go slow.”

A mixed bag for neurologic indications

There are relatively limited data on the use of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, and results have varied. For uses other than pain management, the evidence that does exist is strongest regarding epilepsy, said Daniel Freedman, DO, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Texas at Austin. He noted “multiple high-quality RCTs showing that pharmaceutical-grade CBD can reduce seizures associated with two particular epilepsy syndromes: Dravet Syndrome and Lennox Gastaut.”

These findings led to the FDA’s 2018 approval of Epidiolex for these syndromes. In earlier years, interest in CBD for pediatric seizures was largely driven by anecdotal parental reports of its benefits. NASEM’s 2017 overview on medical cannabis found evidence from subsequent RCTs in this indication to be insufficient. Clinicians who prescribe CBD for this indication must be vigilant because it can interact with several commonly used antiepileptic drugs.

Cannabinoid treatments have also shown success in alleviating muscle spasticity resulting from multiple sclerosis, most prominently in the form of nabiximols (Sativex), a standardized oralmucosal spray containing approximately equal quantities of THC and CBD. Nabiximols is approved in Europe but not in the United States. Moderate evidence supports the efficacy of these and other treatments over placebo in reducing muscle spasticity. Patient ratings of its effects tend to be higher than clinician assessment.

Parkinson’s disease has not yet been approved as an indication for treatment with cannabis or cannabinoids, yet a growing body of preclinical data suggests these could influence the dopaminergic system, said Carsten Buhmann, MD, from the department of neurology at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

“In general, cannabinoids modulate basal-ganglia function on two levels which are especially relevant in Parkinson’s disease, i.e., the glutamatergic/dopaminergic synaptic neurotransmission and the corticostriatal plasticity,” he said. “Furthermore, activation of the endocannabinoid system might induce neuroprotective effects related to direct receptor-independent mechanisms, activation of anti-inflammatory cascades in glial cells via the cannabinoid receptor type 2, and antiglutamatergic antiexcitotoxic properties.”

Dr. Buhmann said that currently, clinical evidence is scarce, consisting of only four double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs involving 49 patients. Various cannabinoids and methods of administering treatment were employed. Improvement was only observed in one of these RCTs, which found that the cannabinoid receptor agonist nabilone significantly reduced levodopa-induced dyskinesia for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Subjective data support a beneficial effect. In a nationwide survey of 1,348 respondents conducted by Dr. Buhmann and colleagues, the majority of medical cannabis users reported that it improved their symptoms (54% with oral CBD and 68% with inhaled THC-containing cannabis).

NASEM concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the efficacy of medical cannabis for other neurologic conditions, including Tourette syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease, dystonia, or dementia. A 2020 position statement from the American Academy of Neurology cited the lack of sufficient peer-reviewed research as the reason it could not currently support the use of cannabis for neurologic disorders.

Yet, according to Dr. Freedman, who served as a coauthor of the AAN position statement, this hasn’t stymied research interest in the topic. He’s seen a substantial uptick in studies of CBD over the past 2 years. “The body of evidence grows, but I still see many claims being made without evidence. And no one seems to care about all the negative trials.”

Cannabis as a treatment for, and cause of, psychiatric disorders

Mental health problems – such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD – are among the most common reasons patients seek out medical cannabis. There is an understandable interest in using cannabis and cannabinoids to treat psychiatric disorders. Preclinical studies suggest that the endocannabinoid system plays a prominent role in modulating feelings of anxiety, mood, and fear. As with opioids and chronic pain management, there is hope that medical cannabis may provide a means of reducing prescription anxiolytics and their associated risks.

The authors of the first systematic review (BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 16;20[1]:24) of the use of medical cannabis for major psychiatric disorders noted that the current evidence was “encouraging, albeit embryonic.”

Meta-analyses have indicated a small but positive association between cannabis use and anxiety, although this may reflect the fact that patients with anxiety sought out this treatment. Given the risks for substance use disorders among patients with anxiety, CBD may present a more viable option. Positive results have been shown as treatment for generalized social anxiety disorder.

Limited but encouraging results have also been reported regarding the alleviation of PTSD symptoms with both cannabis and CBD, although the body of high-quality evidence hasn’t notably progressed since 2017, when NASEM declared that the evidence was insufficient. Supportive evidence is similarly lacking regarding the treatment of depression. Longitudinal studies suggest that cannabis use, particularly heavy use, may increase the risk of developing this disorder. Because THC is psychoactive, it is advised that it be avoided by patients at risk for psychotic disorders. However, CBD has yielded limited benefits for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia and for young people at risk for psychosis.

The use of medical cannabis for psychiatric conditions requires a complex balancing act, inasmuch as these treatments may exacerbate the very problems they are intended to alleviate.

Marta Di Forti, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatric research at Kings College London, has been at the forefront of determining the mental health risks of continued cannabis use. In 2019, Dr. Di Forti developed the first and only Cannabis Clinic for Patients With Psychosis in London where she and her colleagues have continued to elucidate this connection.

Dr. Di Forti and colleagues have linked daily cannabis use to an increase in the risk of experiencing psychotic disorder, compared with never using it. That risk was further increased among users of high-potency cannabis (≥10% THC). The latter finding has troubling implications, because concentrations of THC have steadily risen since 1970. By contrast, CBD concentrations have remained generally stable. High-potency cannabis products are common in both recreational and medicinal settings.

“For somebody prescribing medicinal cannabis that has a ≥10% concentration of THC, I’d be particularly wary of the risk of psychosis,” said Dr. Di Forti. “If you’re expecting people to use a high content of THC daily to medicate pain or a chronic condition, you even more so need to be aware that this is a potential side effect.”

Dr. Di Forti noted that her findings come from a cohort of recreational users, most of whom were aged 18-35 years.

“There have actually not been studies developed from collecting data in this area from groups specifically using cannabis for medicinal rather than recreational purposes,” she said.

She added that she personally has no concerns about the use of medical cannabis but wants clinicians to be aware of the risk for psychosis, to structure their patient conversations to identify risk factors or family histories of psychosis, and to become knowledgeable in detecting the often subtle signs of its initial onset.

When cannabis-associated psychosis occurs, Dr. Di Forti said it is primarily treated with conventional means, such as antipsychotics and therapeutic interventions and by refraining from using cannabis. Achieving the latter goal can be a challenge for patients who are daily users of high-potency cannabis. Currently, there are no treatment options such as those offered to patients withdrawing from the use of alcohol or opioids. Dr. Di Forti and colleagues are currently researching a solution to that problem through the use of another medical cannabis, the oromucosal spray Sativex, which has been approved in the European Union.

The regulatory obstacles to clarifying cannabis’ role in medicine