User login

Low-risk adenomas may not elevate risk of CRC-related death

Unlike high-risk adenomas (HRAs), low-risk adenomas (LRAs) have a minimal association with risk of metachronous colorectal cancer (CRC), and no relationship with odds of metachronous CRC-related mortality, according to a meta-analysis of more than 500,000 individuals.

These findings should impact surveillance guidelines and make follow-up the same for individuals with LRAs or no adenomas, reported lead author Abhiram Duvvuri, MD, of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Kansas, Kansas City, and colleagues. Currently, the United States Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer advises colonoscopy intervals of 3 years for individuals with HRAs, 7-10 years for those with LRAs, and 10 years for those without adenomas.

“The evidence supporting these surveillance recommendations for clinically relevant endpoints such as cancer and cancer-related deaths among patients who undergo adenoma removal, particularly LRA, is minimal, because most of the evidence was based on the surrogate risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

To provide more solid evidence, the investigators performed a systematic review and meta-analysis, ultimately analyzing 12 studies with data from 510,019 individuals at a mean age of 59.2 years. All studies reported rates of LRA, HRA, or no adenoma at baseline colonoscopy, plus incidence of metachronous CRC and/or CRC-related mortality. With these data, the investigators determined incidence of metachronous CRC and CRC-related mortality for each of the adenoma groups and also compared these incidences per 10,000 person-years of follow-up across groups.

After a mean follow-up of 8.5 years, patients with HRAs had a significantly higher rate of CRC compared with patients who had LRAs (13.81 vs. 4.5; odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.72-3.20) or no adenomas (13.81 vs. 3.4; OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 2.31-3.69). Similarly, but to a lesser degree, LRAs were associated with significantly greater risk of CRC than that of no adenomas (4.5 vs. 3.4; OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.06-1.51).

Data on CRC- related mortality further supported these minimal risk profiles because LRAs did not significantly increase the risk of CRC-related mortality compared with no adenomas (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.76-1.74). In contrast, HRAs were associated with significantly greater risk of CRC-related death than that of both LRAs (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.30-4.75) and no adenomas (OR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.87-3.87).

The investigators acknowledged certain limitations of their study. For one, there were no randomized controlled trials in the meta-analysis, which can introduce bias. Loss of patients to follow-up is also possible; however, the investigators noted that there was a robust sample of patients available for study outcomes all the same. There is also risk of comparability bias in that HRA and LRA groups underwent more colonoscopies; however, the duration of follow-up and timing of last colonoscopy were similar among groups. Lastly, it’s possible the patient sample wasn’t representative because of healthy screenee bias, but the investigators compared groups against general population to minimize that bias.

The investigators also highlighted several strengths of their study that make their findings more reliable than those of past meta-analyses. For one, their study is the largest of its kind to date, and involved a significantly higher number of patients with LRA and no adenomas. Also, in contrast with previous studies, CRC and CRC-related mortality were evaluated rather than advanced adenomas, they noted.

“Furthermore, we also analyzed CRC incidence and mortality in the LRA group compared with the general population, with the [standardized incidence ratio] being lower and [standardized mortality ratio] being comparable, confirming that it is indeed a low-risk group,” they wrote.

Considering these strengths and the nature of their findings, Dr. Duvvuri and colleagues called for a more conservative approach to CRC surveillance among individuals with LRAs, and more research to investigate extending colonoscopy intervals even further.

“We recommend that the interval for follow-up colonoscopy should be the same in patients with LRAs or no adenomas but that the HRA group should have a more frequent surveillance interval for CRC surveillance compared with these groups,” they concluded. “Future studies should evaluate whether surveillance intervals could be lengthened beyond 10 years in the no-adenoma and LRA groups after an initial high-quality index colonoscopy.”

One author disclosed affiliations with Erbe, Cdx Labs, Aries, and others. Dr. Duvvuri and the remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

Despite evidence suggesting that colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality can be decreased through the endoscopic removal of adenomatous polyps, the question remains as to whether further endoscopic surveillance is necessary after polypectomy and, if so, how often. The most recent iteration of the United States Multi-Society Task Force guidelines endorsed a lengthening of the surveillance interval following the removal of low-risk adenomas (LRAs), defined as 1-2 tubular adenomas <10 mm with low-grade dysplasia, while maintaining a shorter interval for high-risk adenomas (HRAs), defined as advanced adenomas (villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or >10 mm) or >3 adenomas.

Dr. Duvvuri and colleagues present the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining metachronous CRC incidence and mortality following index colonoscopy. They found a small but statistically significant increase in the incidence of CRC but no significant difference in CRC mortality when comparing patients with LRAs to those with no adenomas. In contrast, they found both a statistically and clinically significant difference in CRC incidence/mortality when comparing patients with HRAs to both those with no adenomas and those with LRAs. They concluded that these results support a recommendation for no difference in follow-up surveillance between patients with LRAs and no adenomas but do support more frequent surveillance for patients with HRAs at index colonoscopy.

Future studies should better examine the timing of neoplasm incidence/recurrence following adenoma removal and also examine metachronous CRC incidence/mortality in patients with sessile serrated lesions at index colonoscopy.

Reid M. Ness, MD, MPH, AGAF, is an associate professor in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, campus. He is an investigator in the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. Dr. Ness has no financial relationships to disclose.

Despite evidence suggesting that colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality can be decreased through the endoscopic removal of adenomatous polyps, the question remains as to whether further endoscopic surveillance is necessary after polypectomy and, if so, how often. The most recent iteration of the United States Multi-Society Task Force guidelines endorsed a lengthening of the surveillance interval following the removal of low-risk adenomas (LRAs), defined as 1-2 tubular adenomas <10 mm with low-grade dysplasia, while maintaining a shorter interval for high-risk adenomas (HRAs), defined as advanced adenomas (villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or >10 mm) or >3 adenomas.

Dr. Duvvuri and colleagues present the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining metachronous CRC incidence and mortality following index colonoscopy. They found a small but statistically significant increase in the incidence of CRC but no significant difference in CRC mortality when comparing patients with LRAs to those with no adenomas. In contrast, they found both a statistically and clinically significant difference in CRC incidence/mortality when comparing patients with HRAs to both those with no adenomas and those with LRAs. They concluded that these results support a recommendation for no difference in follow-up surveillance between patients with LRAs and no adenomas but do support more frequent surveillance for patients with HRAs at index colonoscopy.

Future studies should better examine the timing of neoplasm incidence/recurrence following adenoma removal and also examine metachronous CRC incidence/mortality in patients with sessile serrated lesions at index colonoscopy.

Reid M. Ness, MD, MPH, AGAF, is an associate professor in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, campus. He is an investigator in the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. Dr. Ness has no financial relationships to disclose.

Despite evidence suggesting that colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality can be decreased through the endoscopic removal of adenomatous polyps, the question remains as to whether further endoscopic surveillance is necessary after polypectomy and, if so, how often. The most recent iteration of the United States Multi-Society Task Force guidelines endorsed a lengthening of the surveillance interval following the removal of low-risk adenomas (LRAs), defined as 1-2 tubular adenomas <10 mm with low-grade dysplasia, while maintaining a shorter interval for high-risk adenomas (HRAs), defined as advanced adenomas (villous histology, high-grade dysplasia, or >10 mm) or >3 adenomas.

Dr. Duvvuri and colleagues present the results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining metachronous CRC incidence and mortality following index colonoscopy. They found a small but statistically significant increase in the incidence of CRC but no significant difference in CRC mortality when comparing patients with LRAs to those with no adenomas. In contrast, they found both a statistically and clinically significant difference in CRC incidence/mortality when comparing patients with HRAs to both those with no adenomas and those with LRAs. They concluded that these results support a recommendation for no difference in follow-up surveillance between patients with LRAs and no adenomas but do support more frequent surveillance for patients with HRAs at index colonoscopy.

Future studies should better examine the timing of neoplasm incidence/recurrence following adenoma removal and also examine metachronous CRC incidence/mortality in patients with sessile serrated lesions at index colonoscopy.

Reid M. Ness, MD, MPH, AGAF, is an associate professor in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, campus. He is an investigator in the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. Dr. Ness has no financial relationships to disclose.

Unlike high-risk adenomas (HRAs), low-risk adenomas (LRAs) have a minimal association with risk of metachronous colorectal cancer (CRC), and no relationship with odds of metachronous CRC-related mortality, according to a meta-analysis of more than 500,000 individuals.

These findings should impact surveillance guidelines and make follow-up the same for individuals with LRAs or no adenomas, reported lead author Abhiram Duvvuri, MD, of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Kansas, Kansas City, and colleagues. Currently, the United States Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer advises colonoscopy intervals of 3 years for individuals with HRAs, 7-10 years for those with LRAs, and 10 years for those without adenomas.

“The evidence supporting these surveillance recommendations for clinically relevant endpoints such as cancer and cancer-related deaths among patients who undergo adenoma removal, particularly LRA, is minimal, because most of the evidence was based on the surrogate risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

To provide more solid evidence, the investigators performed a systematic review and meta-analysis, ultimately analyzing 12 studies with data from 510,019 individuals at a mean age of 59.2 years. All studies reported rates of LRA, HRA, or no adenoma at baseline colonoscopy, plus incidence of metachronous CRC and/or CRC-related mortality. With these data, the investigators determined incidence of metachronous CRC and CRC-related mortality for each of the adenoma groups and also compared these incidences per 10,000 person-years of follow-up across groups.

After a mean follow-up of 8.5 years, patients with HRAs had a significantly higher rate of CRC compared with patients who had LRAs (13.81 vs. 4.5; odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.72-3.20) or no adenomas (13.81 vs. 3.4; OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 2.31-3.69). Similarly, but to a lesser degree, LRAs were associated with significantly greater risk of CRC than that of no adenomas (4.5 vs. 3.4; OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.06-1.51).

Data on CRC- related mortality further supported these minimal risk profiles because LRAs did not significantly increase the risk of CRC-related mortality compared with no adenomas (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.76-1.74). In contrast, HRAs were associated with significantly greater risk of CRC-related death than that of both LRAs (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.30-4.75) and no adenomas (OR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.87-3.87).

The investigators acknowledged certain limitations of their study. For one, there were no randomized controlled trials in the meta-analysis, which can introduce bias. Loss of patients to follow-up is also possible; however, the investigators noted that there was a robust sample of patients available for study outcomes all the same. There is also risk of comparability bias in that HRA and LRA groups underwent more colonoscopies; however, the duration of follow-up and timing of last colonoscopy were similar among groups. Lastly, it’s possible the patient sample wasn’t representative because of healthy screenee bias, but the investigators compared groups against general population to minimize that bias.

The investigators also highlighted several strengths of their study that make their findings more reliable than those of past meta-analyses. For one, their study is the largest of its kind to date, and involved a significantly higher number of patients with LRA and no adenomas. Also, in contrast with previous studies, CRC and CRC-related mortality were evaluated rather than advanced adenomas, they noted.

“Furthermore, we also analyzed CRC incidence and mortality in the LRA group compared with the general population, with the [standardized incidence ratio] being lower and [standardized mortality ratio] being comparable, confirming that it is indeed a low-risk group,” they wrote.

Considering these strengths and the nature of their findings, Dr. Duvvuri and colleagues called for a more conservative approach to CRC surveillance among individuals with LRAs, and more research to investigate extending colonoscopy intervals even further.

“We recommend that the interval for follow-up colonoscopy should be the same in patients with LRAs or no adenomas but that the HRA group should have a more frequent surveillance interval for CRC surveillance compared with these groups,” they concluded. “Future studies should evaluate whether surveillance intervals could be lengthened beyond 10 years in the no-adenoma and LRA groups after an initial high-quality index colonoscopy.”

One author disclosed affiliations with Erbe, Cdx Labs, Aries, and others. Dr. Duvvuri and the remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

Unlike high-risk adenomas (HRAs), low-risk adenomas (LRAs) have a minimal association with risk of metachronous colorectal cancer (CRC), and no relationship with odds of metachronous CRC-related mortality, according to a meta-analysis of more than 500,000 individuals.

These findings should impact surveillance guidelines and make follow-up the same for individuals with LRAs or no adenomas, reported lead author Abhiram Duvvuri, MD, of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Kansas, Kansas City, and colleagues. Currently, the United States Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer advises colonoscopy intervals of 3 years for individuals with HRAs, 7-10 years for those with LRAs, and 10 years for those without adenomas.

“The evidence supporting these surveillance recommendations for clinically relevant endpoints such as cancer and cancer-related deaths among patients who undergo adenoma removal, particularly LRA, is minimal, because most of the evidence was based on the surrogate risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology.

To provide more solid evidence, the investigators performed a systematic review and meta-analysis, ultimately analyzing 12 studies with data from 510,019 individuals at a mean age of 59.2 years. All studies reported rates of LRA, HRA, or no adenoma at baseline colonoscopy, plus incidence of metachronous CRC and/or CRC-related mortality. With these data, the investigators determined incidence of metachronous CRC and CRC-related mortality for each of the adenoma groups and also compared these incidences per 10,000 person-years of follow-up across groups.

After a mean follow-up of 8.5 years, patients with HRAs had a significantly higher rate of CRC compared with patients who had LRAs (13.81 vs. 4.5; odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.72-3.20) or no adenomas (13.81 vs. 3.4; OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 2.31-3.69). Similarly, but to a lesser degree, LRAs were associated with significantly greater risk of CRC than that of no adenomas (4.5 vs. 3.4; OR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.06-1.51).

Data on CRC- related mortality further supported these minimal risk profiles because LRAs did not significantly increase the risk of CRC-related mortality compared with no adenomas (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.76-1.74). In contrast, HRAs were associated with significantly greater risk of CRC-related death than that of both LRAs (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.30-4.75) and no adenomas (OR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.87-3.87).

The investigators acknowledged certain limitations of their study. For one, there were no randomized controlled trials in the meta-analysis, which can introduce bias. Loss of patients to follow-up is also possible; however, the investigators noted that there was a robust sample of patients available for study outcomes all the same. There is also risk of comparability bias in that HRA and LRA groups underwent more colonoscopies; however, the duration of follow-up and timing of last colonoscopy were similar among groups. Lastly, it’s possible the patient sample wasn’t representative because of healthy screenee bias, but the investigators compared groups against general population to minimize that bias.

The investigators also highlighted several strengths of their study that make their findings more reliable than those of past meta-analyses. For one, their study is the largest of its kind to date, and involved a significantly higher number of patients with LRA and no adenomas. Also, in contrast with previous studies, CRC and CRC-related mortality were evaluated rather than advanced adenomas, they noted.

“Furthermore, we also analyzed CRC incidence and mortality in the LRA group compared with the general population, with the [standardized incidence ratio] being lower and [standardized mortality ratio] being comparable, confirming that it is indeed a low-risk group,” they wrote.

Considering these strengths and the nature of their findings, Dr. Duvvuri and colleagues called for a more conservative approach to CRC surveillance among individuals with LRAs, and more research to investigate extending colonoscopy intervals even further.

“We recommend that the interval for follow-up colonoscopy should be the same in patients with LRAs or no adenomas but that the HRA group should have a more frequent surveillance interval for CRC surveillance compared with these groups,” they concluded. “Future studies should evaluate whether surveillance intervals could be lengthened beyond 10 years in the no-adenoma and LRA groups after an initial high-quality index colonoscopy.”

One author disclosed affiliations with Erbe, Cdx Labs, Aries, and others. Dr. Duvvuri and the remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is the answer to childhood obesity

There is no question that none of us, not just pediatricians, is doing a very good job of dealing with the obesity problem this nation faces. We can agree that a more active lifestyle that includes spells of vigorous activity is important for weight management. We know that in general overweight people sleep less than do those whose basal metabolic rate is normal. And, of course, we know that a diet high in calorie-dense foods is associated with unhealthy weight gain.

Not surprisingly, overweight individuals are usually struggling with all three of these challenges. They are less active, get too little sleep, and are ingesting a diet that is too calorie dense. In other words, they would benefit from a total lifestyle reboot. But you know as well as I do a change of that magnitude is much easier said than done. Few families can afford nor would they have the appetite for sending their children to a “fat camp” for 6 months with no guarantee of success.

Instead of throwing up our hands in the face of this monumental task or attacking it at close range, maybe we should aim our efforts at the risk associations that will yield the best results for our efforts. A group of researchers at the University of South Australia has just published a study in Pediatrics in which they provide some data that may help us target our interventions with obese and overweight children. The researchers did not investigate diet, but used accelerometers to determine how much time each child spent sleeping and a variety of activity levels. They then determined what effect changes in the child’s allocation of activity had on their adiposity.

The investigators found on a minute-to-minute basis that an increase in a child’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was up to six times more effective at influencing adiposity than was a decrease in sedentary time or an increase in sleep duration. For example, 17 minutes of MVPA had the same beneficial effect as 52 minutes more sleep or 56 minutes less sedentary time. Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, the researchers found that light activity was positively associated with adiposity.

For those of us in primary care, this study from Australia suggests that our time (and the parents’ time) would be best spent figuring out how to include more MVPA in the child’s day and not focus so much on sleep duration and sedentary intervals.

However, before one can make any recommendation one must first have a clear understanding of how the child and his family spend the day. This process can be done in the office by interviewing the family. I have found that this is not as time consuming as one might think and often yields some valuable additional insight into the family’s dynamics. Sending the family home with an hourly log to be filled in or asking them to use a smartphone to record information will also work.

I must admit that at first I found the results of this study ran counter to my intuition. I have always felt that sleep is the linchpin to the solution of a variety of health style related problems. In my construct, more sleep has always been the first and easy answer and decreasing screen time the second. But, it turns out that increasing MVPA may give us the biggest bang for the buck. Which is fine with me.

The problem facing us is how we can be creative in adding that 20 minutes of vigorous activity. In most communities, we have allowed the school system to drop the ball. We can hope that this study will be confirmed or at least widely publicized. It feels like it is time to guarantee that every child gets a robust gym class every school day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

There is no question that none of us, not just pediatricians, is doing a very good job of dealing with the obesity problem this nation faces. We can agree that a more active lifestyle that includes spells of vigorous activity is important for weight management. We know that in general overweight people sleep less than do those whose basal metabolic rate is normal. And, of course, we know that a diet high in calorie-dense foods is associated with unhealthy weight gain.

Not surprisingly, overweight individuals are usually struggling with all three of these challenges. They are less active, get too little sleep, and are ingesting a diet that is too calorie dense. In other words, they would benefit from a total lifestyle reboot. But you know as well as I do a change of that magnitude is much easier said than done. Few families can afford nor would they have the appetite for sending their children to a “fat camp” for 6 months with no guarantee of success.

Instead of throwing up our hands in the face of this monumental task or attacking it at close range, maybe we should aim our efforts at the risk associations that will yield the best results for our efforts. A group of researchers at the University of South Australia has just published a study in Pediatrics in which they provide some data that may help us target our interventions with obese and overweight children. The researchers did not investigate diet, but used accelerometers to determine how much time each child spent sleeping and a variety of activity levels. They then determined what effect changes in the child’s allocation of activity had on their adiposity.

The investigators found on a minute-to-minute basis that an increase in a child’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was up to six times more effective at influencing adiposity than was a decrease in sedentary time or an increase in sleep duration. For example, 17 minutes of MVPA had the same beneficial effect as 52 minutes more sleep or 56 minutes less sedentary time. Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, the researchers found that light activity was positively associated with adiposity.

For those of us in primary care, this study from Australia suggests that our time (and the parents’ time) would be best spent figuring out how to include more MVPA in the child’s day and not focus so much on sleep duration and sedentary intervals.

However, before one can make any recommendation one must first have a clear understanding of how the child and his family spend the day. This process can be done in the office by interviewing the family. I have found that this is not as time consuming as one might think and often yields some valuable additional insight into the family’s dynamics. Sending the family home with an hourly log to be filled in or asking them to use a smartphone to record information will also work.

I must admit that at first I found the results of this study ran counter to my intuition. I have always felt that sleep is the linchpin to the solution of a variety of health style related problems. In my construct, more sleep has always been the first and easy answer and decreasing screen time the second. But, it turns out that increasing MVPA may give us the biggest bang for the buck. Which is fine with me.

The problem facing us is how we can be creative in adding that 20 minutes of vigorous activity. In most communities, we have allowed the school system to drop the ball. We can hope that this study will be confirmed or at least widely publicized. It feels like it is time to guarantee that every child gets a robust gym class every school day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

There is no question that none of us, not just pediatricians, is doing a very good job of dealing with the obesity problem this nation faces. We can agree that a more active lifestyle that includes spells of vigorous activity is important for weight management. We know that in general overweight people sleep less than do those whose basal metabolic rate is normal. And, of course, we know that a diet high in calorie-dense foods is associated with unhealthy weight gain.

Not surprisingly, overweight individuals are usually struggling with all three of these challenges. They are less active, get too little sleep, and are ingesting a diet that is too calorie dense. In other words, they would benefit from a total lifestyle reboot. But you know as well as I do a change of that magnitude is much easier said than done. Few families can afford nor would they have the appetite for sending their children to a “fat camp” for 6 months with no guarantee of success.

Instead of throwing up our hands in the face of this monumental task or attacking it at close range, maybe we should aim our efforts at the risk associations that will yield the best results for our efforts. A group of researchers at the University of South Australia has just published a study in Pediatrics in which they provide some data that may help us target our interventions with obese and overweight children. The researchers did not investigate diet, but used accelerometers to determine how much time each child spent sleeping and a variety of activity levels. They then determined what effect changes in the child’s allocation of activity had on their adiposity.

The investigators found on a minute-to-minute basis that an increase in a child’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was up to six times more effective at influencing adiposity than was a decrease in sedentary time or an increase in sleep duration. For example, 17 minutes of MVPA had the same beneficial effect as 52 minutes more sleep or 56 minutes less sedentary time. Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, the researchers found that light activity was positively associated with adiposity.

For those of us in primary care, this study from Australia suggests that our time (and the parents’ time) would be best spent figuring out how to include more MVPA in the child’s day and not focus so much on sleep duration and sedentary intervals.

However, before one can make any recommendation one must first have a clear understanding of how the child and his family spend the day. This process can be done in the office by interviewing the family. I have found that this is not as time consuming as one might think and often yields some valuable additional insight into the family’s dynamics. Sending the family home with an hourly log to be filled in or asking them to use a smartphone to record information will also work.

I must admit that at first I found the results of this study ran counter to my intuition. I have always felt that sleep is the linchpin to the solution of a variety of health style related problems. In my construct, more sleep has always been the first and easy answer and decreasing screen time the second. But, it turns out that increasing MVPA may give us the biggest bang for the buck. Which is fine with me.

The problem facing us is how we can be creative in adding that 20 minutes of vigorous activity. In most communities, we have allowed the school system to drop the ball. We can hope that this study will be confirmed or at least widely publicized. It feels like it is time to guarantee that every child gets a robust gym class every school day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Using (dynamic) ultrasound to make an earlier diagnosis of endometriosis

Can you provide some background on endometriosis and the importance of early diagnosis?

Dr. Goldstein: Endometriosis is an inflammatory condition, characterized by endometrial tissue at sites outside the uterus—this definition comes from the World Endometriosis Society.

Endometriosis is said to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age, and if you look at a group, a subset of women with pelvic pain or infertility, the numbers rise to the range of 35% to 50%. It can present in a multitude of locations, mainly in the pelvis, although occasionally even in places like the lung. When it occurs in the uterus, it is known as adenomyosis; when it occurs inside the ovary, it can cause an endometrioma (or what is sometimes referred to as chocolate cyst of the ovary), but you can see endometriotic implants anywhere in the peritoneum—along the urinary tract, rectum, uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, and even the vaginal wall occasionally.

What I am really interested in is an earlier diagnosis of superficial endometriosis, and it should be apparent to the reader why this is important—the quality of life from pain from endometriosis can be debilitating. It can be a source of infertility, a source of menstrual irregularities, and a source of not only quality of life but also economic consequences. Many women can also undergo as much as a 7-year delay in diagnosis, so the need for a timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment is extremely important.

What is the role of ultrasound in endometriosis diagnostics?

Dr. Goldstein: In an article that I authored 31 years ago, I wrote that there was a difference between an ultrasound examination by referral and examining one’s patients with ultrasound. I coined a phrase: the “ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam.” I believed that this term should become a routine part of the overall gynecologic exam. I wanted people to think about the bimanual that we had done for at least half a century, which, in my opinion, consists of 2 components:

- An objective component: Is this uterus normal? Is it enlarged or irregular in contour, suggesting maybe fibroids? Is an ovary enlarged? If so, does it feel cystic or solid?

- A subjective component: Does this patient have tenderness through the pelvis. Is there normal mobility of the pelvic organs?

Part of the thesis was that the objective portion could be replaced by an image that could be produced in seconds, dependent on the operator’s training and availability of equipment. The subjective portion, however, depended on the experience and, often, nuance of the examiner. Lately, I have been seeking to expand that thesis by having the imager use examination as part of their overall imaging—this is the concept of dynamic imaging.

Can you expand on the concept of dynamic ultrasound in this setting?

Dr. Goldstein: Presently, most imagers take a multitude of pictures, what I would call 2-dimensional snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. This is usually done by a sonographer, or a technician, who collects the images for viewing by the physician, who then often does so without holding the transducer. Increasing utilization of remote tools like teleradiology only makes this more likely, and for a minority of people who may use video clips instead of still images, they are still simply representations of anatomy. The guidelines for pelvic ultrasound are the underpinning of the expectation of those who are scanning the female pelvis. With dynamic imaging, the operator uses their other hand on the abdomen as well as some motion with the probe to see if they can elicit pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. Whether you are a sonographer, a radiologist, or an ObGyn, dynamic imaging can bring the examination process into the imager’s hands.

Can you tell us more about the indications for pelvic sonography for endometriosis and what data can you give to support this?

Dr. Goldstein: There is a document titled “Ultrasound Examination of the Female Pelvis,” that was originally developed by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). In this document, there are about 19 different indications for pelvic sonography (in no defined order), and it is interesting that the first indication listed is evaluation of pelvic pain. Well, I would ask you, how do you evaluate pelvic pain with a series of anatomic images? If you have a classic ovarian endometrioma, or you have a classic hydrosalpinx, you can surmise that these are the source of the pain that the patient is reporting. But how do you properly evaluate pain with just an anatomic image? Thus, the need to use dynamic assessment.

There was a concept first introduced by my colleague, Dr. Ilan Timor, known as the sliding organ sign, that was mainly used to determine if 2 structures were adherent or separate. This involved use of the abdominal hand, liberal use of the probe moving in and out, and under real-time vision, examining the patient with the ultrasound transducer; this is the concept of dynamic ultrasound. This practice can be expanded to verify if there is pelvic tenderness and can be a significant part of the nonlaparoscopic, presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis, even when there is no ovarian endometrioma.

To support this theory, I would point you toward a classic article by E Okaro and colleagues in the British Journal of OB-GYN. This study took 120 consecutive women with chronic pelvic pain who were scheduled for laparoscopy, but performed a transvaginal ultrasound prior, and they looked for anatomic abnormalities and divided this into hard markers and soft markers. Hard markers were obvious endometriomas and hydrosalpinges, while soft markers included things like reduced ovarian mobility, site-specific pelvic tenderness, and presence of loculated peritoneal fluid in the pelvis. These were typical of chronic pelvic pain patients that ranged from late teens to almost menopausal, as the average age was about 30 years old.

Patients had experienced pain for anywhere from 6 months to 12 years, but the average was about 4 years. At laparoscopy, 58% of these patients had pelvic pathology, and 42% had a normal pelvis. Of the 58% with pathology, the overwhelming majority—about 51 of 70 women—had endometriosis alone, and another 7 had endometriosis with adhesions. A normal ultrasound, based on the absence of hard markers, was found in 96 of 120 women. Thus, 24 of the 120 women had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these hard markers. At laparoscopy, all 24 women had abnormal laparoscopies. Of those 96 women who would have had a normal ultrasound, based on the anatomic absence of some pathology, 53% had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these soft markers while the remaining women had no soft- or hard-markers suggesting any pelvic pathology. At laparoscopy, 73% of the patients with soft markers had pelvic pathology and 27% had a normal laparoscopy. Of 45 patients who had a normal, transvaginal ultrasound, 9 were found to have small evidence of endometriosis without discrete endometriomas at laparoscopy.

To summarize the study data, 100% of patients with hard markers and chronic pelvic pain had abnormal anatomy at laparoscopy, but 73% of patients who had soft markers but otherwise would have been interpreted as normal anatomic findings had evidence of pelvic pathology. Such an approach, if used, could lead to a reduction in the number of unnecessary laparoscopies.

What it really boils down to is, if you have 100 women with chronic pelvic pain, are you willing to treat 100 patients without laparoscopy, knowing that 73 are going to have a positive laparoscopy and will require treatment anyway? You would treat 27% with a pharmaceutical agent that may provide relief of their pain, or may not, depending on what the true etiology was. I would be willing to do so, as a positive predictive value of 73% makes doing that worthwhile, and I believe a majority of clinicians would agree.

Do you have any other tips or ways to improve the reader’s understanding of transvaginal ultrasound?

Dr. Goldstein: Pelvic organs have mobility. If a premenopausal woman is examined in lithotomy position, if the ovaries are freely mobile, by gravity, they are going to go lateral to the uterus and are seen immediately adjacent to the iliac vessels. But remember, iliac vessels are retroperitoneal as they are outside the peritoneal cavity. If you were to turn that patient onto all fours, so that the ovaries are freely mobile, they are going to move somewhat toward the anterior abdominal wall. When an ovary is seen in a nonanatomic position, it could be normal or it could be held up by a loop of bowel, but it may indicate adhesions. This is where this sliding organ sign and liberal use of the other hand on the lower abdomen can be extremely important. The reader should also understand that our ability to localize ovaries on ultrasound depends on the amount of folliculogenesis. Follicles are black circles that are sonolucent, because they contain fluid, so they make it easy to localize ovaries, but also their anatomic position relative to the iliac vessels. However, there is a caveat—which is, sometimes an ovary might look like it is behind the uterus and not in its normal anatomic location. When dynamic imaging is used, you are able to cajole that ovary to move lateral and sit on top of the iliac vessels, which can enable you make the proper diagnosis.

Can you provide some background on endometriosis and the importance of early diagnosis?

Dr. Goldstein: Endometriosis is an inflammatory condition, characterized by endometrial tissue at sites outside the uterus—this definition comes from the World Endometriosis Society.

Endometriosis is said to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age, and if you look at a group, a subset of women with pelvic pain or infertility, the numbers rise to the range of 35% to 50%. It can present in a multitude of locations, mainly in the pelvis, although occasionally even in places like the lung. When it occurs in the uterus, it is known as adenomyosis; when it occurs inside the ovary, it can cause an endometrioma (or what is sometimes referred to as chocolate cyst of the ovary), but you can see endometriotic implants anywhere in the peritoneum—along the urinary tract, rectum, uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, and even the vaginal wall occasionally.

What I am really interested in is an earlier diagnosis of superficial endometriosis, and it should be apparent to the reader why this is important—the quality of life from pain from endometriosis can be debilitating. It can be a source of infertility, a source of menstrual irregularities, and a source of not only quality of life but also economic consequences. Many women can also undergo as much as a 7-year delay in diagnosis, so the need for a timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment is extremely important.

What is the role of ultrasound in endometriosis diagnostics?

Dr. Goldstein: In an article that I authored 31 years ago, I wrote that there was a difference between an ultrasound examination by referral and examining one’s patients with ultrasound. I coined a phrase: the “ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam.” I believed that this term should become a routine part of the overall gynecologic exam. I wanted people to think about the bimanual that we had done for at least half a century, which, in my opinion, consists of 2 components:

- An objective component: Is this uterus normal? Is it enlarged or irregular in contour, suggesting maybe fibroids? Is an ovary enlarged? If so, does it feel cystic or solid?

- A subjective component: Does this patient have tenderness through the pelvis. Is there normal mobility of the pelvic organs?

Part of the thesis was that the objective portion could be replaced by an image that could be produced in seconds, dependent on the operator’s training and availability of equipment. The subjective portion, however, depended on the experience and, often, nuance of the examiner. Lately, I have been seeking to expand that thesis by having the imager use examination as part of their overall imaging—this is the concept of dynamic imaging.

Can you expand on the concept of dynamic ultrasound in this setting?

Dr. Goldstein: Presently, most imagers take a multitude of pictures, what I would call 2-dimensional snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. This is usually done by a sonographer, or a technician, who collects the images for viewing by the physician, who then often does so without holding the transducer. Increasing utilization of remote tools like teleradiology only makes this more likely, and for a minority of people who may use video clips instead of still images, they are still simply representations of anatomy. The guidelines for pelvic ultrasound are the underpinning of the expectation of those who are scanning the female pelvis. With dynamic imaging, the operator uses their other hand on the abdomen as well as some motion with the probe to see if they can elicit pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. Whether you are a sonographer, a radiologist, or an ObGyn, dynamic imaging can bring the examination process into the imager’s hands.

Can you tell us more about the indications for pelvic sonography for endometriosis and what data can you give to support this?

Dr. Goldstein: There is a document titled “Ultrasound Examination of the Female Pelvis,” that was originally developed by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). In this document, there are about 19 different indications for pelvic sonography (in no defined order), and it is interesting that the first indication listed is evaluation of pelvic pain. Well, I would ask you, how do you evaluate pelvic pain with a series of anatomic images? If you have a classic ovarian endometrioma, or you have a classic hydrosalpinx, you can surmise that these are the source of the pain that the patient is reporting. But how do you properly evaluate pain with just an anatomic image? Thus, the need to use dynamic assessment.

There was a concept first introduced by my colleague, Dr. Ilan Timor, known as the sliding organ sign, that was mainly used to determine if 2 structures were adherent or separate. This involved use of the abdominal hand, liberal use of the probe moving in and out, and under real-time vision, examining the patient with the ultrasound transducer; this is the concept of dynamic ultrasound. This practice can be expanded to verify if there is pelvic tenderness and can be a significant part of the nonlaparoscopic, presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis, even when there is no ovarian endometrioma.

To support this theory, I would point you toward a classic article by E Okaro and colleagues in the British Journal of OB-GYN. This study took 120 consecutive women with chronic pelvic pain who were scheduled for laparoscopy, but performed a transvaginal ultrasound prior, and they looked for anatomic abnormalities and divided this into hard markers and soft markers. Hard markers were obvious endometriomas and hydrosalpinges, while soft markers included things like reduced ovarian mobility, site-specific pelvic tenderness, and presence of loculated peritoneal fluid in the pelvis. These were typical of chronic pelvic pain patients that ranged from late teens to almost menopausal, as the average age was about 30 years old.

Patients had experienced pain for anywhere from 6 months to 12 years, but the average was about 4 years. At laparoscopy, 58% of these patients had pelvic pathology, and 42% had a normal pelvis. Of the 58% with pathology, the overwhelming majority—about 51 of 70 women—had endometriosis alone, and another 7 had endometriosis with adhesions. A normal ultrasound, based on the absence of hard markers, was found in 96 of 120 women. Thus, 24 of the 120 women had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these hard markers. At laparoscopy, all 24 women had abnormal laparoscopies. Of those 96 women who would have had a normal ultrasound, based on the anatomic absence of some pathology, 53% had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these soft markers while the remaining women had no soft- or hard-markers suggesting any pelvic pathology. At laparoscopy, 73% of the patients with soft markers had pelvic pathology and 27% had a normal laparoscopy. Of 45 patients who had a normal, transvaginal ultrasound, 9 were found to have small evidence of endometriosis without discrete endometriomas at laparoscopy.

To summarize the study data, 100% of patients with hard markers and chronic pelvic pain had abnormal anatomy at laparoscopy, but 73% of patients who had soft markers but otherwise would have been interpreted as normal anatomic findings had evidence of pelvic pathology. Such an approach, if used, could lead to a reduction in the number of unnecessary laparoscopies.

What it really boils down to is, if you have 100 women with chronic pelvic pain, are you willing to treat 100 patients without laparoscopy, knowing that 73 are going to have a positive laparoscopy and will require treatment anyway? You would treat 27% with a pharmaceutical agent that may provide relief of their pain, or may not, depending on what the true etiology was. I would be willing to do so, as a positive predictive value of 73% makes doing that worthwhile, and I believe a majority of clinicians would agree.

Do you have any other tips or ways to improve the reader’s understanding of transvaginal ultrasound?

Dr. Goldstein: Pelvic organs have mobility. If a premenopausal woman is examined in lithotomy position, if the ovaries are freely mobile, by gravity, they are going to go lateral to the uterus and are seen immediately adjacent to the iliac vessels. But remember, iliac vessels are retroperitoneal as they are outside the peritoneal cavity. If you were to turn that patient onto all fours, so that the ovaries are freely mobile, they are going to move somewhat toward the anterior abdominal wall. When an ovary is seen in a nonanatomic position, it could be normal or it could be held up by a loop of bowel, but it may indicate adhesions. This is where this sliding organ sign and liberal use of the other hand on the lower abdomen can be extremely important. The reader should also understand that our ability to localize ovaries on ultrasound depends on the amount of folliculogenesis. Follicles are black circles that are sonolucent, because they contain fluid, so they make it easy to localize ovaries, but also their anatomic position relative to the iliac vessels. However, there is a caveat—which is, sometimes an ovary might look like it is behind the uterus and not in its normal anatomic location. When dynamic imaging is used, you are able to cajole that ovary to move lateral and sit on top of the iliac vessels, which can enable you make the proper diagnosis.

Can you provide some background on endometriosis and the importance of early diagnosis?

Dr. Goldstein: Endometriosis is an inflammatory condition, characterized by endometrial tissue at sites outside the uterus—this definition comes from the World Endometriosis Society.

Endometriosis is said to affect about 10% of women of reproductive age, and if you look at a group, a subset of women with pelvic pain or infertility, the numbers rise to the range of 35% to 50%. It can present in a multitude of locations, mainly in the pelvis, although occasionally even in places like the lung. When it occurs in the uterus, it is known as adenomyosis; when it occurs inside the ovary, it can cause an endometrioma (or what is sometimes referred to as chocolate cyst of the ovary), but you can see endometriotic implants anywhere in the peritoneum—along the urinary tract, rectum, uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, and even the vaginal wall occasionally.

What I am really interested in is an earlier diagnosis of superficial endometriosis, and it should be apparent to the reader why this is important—the quality of life from pain from endometriosis can be debilitating. It can be a source of infertility, a source of menstrual irregularities, and a source of not only quality of life but also economic consequences. Many women can also undergo as much as a 7-year delay in diagnosis, so the need for a timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment is extremely important.

What is the role of ultrasound in endometriosis diagnostics?

Dr. Goldstein: In an article that I authored 31 years ago, I wrote that there was a difference between an ultrasound examination by referral and examining one’s patients with ultrasound. I coined a phrase: the “ultrasound-enhanced bimanual exam.” I believed that this term should become a routine part of the overall gynecologic exam. I wanted people to think about the bimanual that we had done for at least half a century, which, in my opinion, consists of 2 components:

- An objective component: Is this uterus normal? Is it enlarged or irregular in contour, suggesting maybe fibroids? Is an ovary enlarged? If so, does it feel cystic or solid?

- A subjective component: Does this patient have tenderness through the pelvis. Is there normal mobility of the pelvic organs?

Part of the thesis was that the objective portion could be replaced by an image that could be produced in seconds, dependent on the operator’s training and availability of equipment. The subjective portion, however, depended on the experience and, often, nuance of the examiner. Lately, I have been seeking to expand that thesis by having the imager use examination as part of their overall imaging—this is the concept of dynamic imaging.

Can you expand on the concept of dynamic ultrasound in this setting?

Dr. Goldstein: Presently, most imagers take a multitude of pictures, what I would call 2-dimensional snapshots, to illustrate anatomy. This is usually done by a sonographer, or a technician, who collects the images for viewing by the physician, who then often does so without holding the transducer. Increasing utilization of remote tools like teleradiology only makes this more likely, and for a minority of people who may use video clips instead of still images, they are still simply representations of anatomy. The guidelines for pelvic ultrasound are the underpinning of the expectation of those who are scanning the female pelvis. With dynamic imaging, the operator uses their other hand on the abdomen as well as some motion with the probe to see if they can elicit pain with the vaginal probe, checking for mobility, asking the patient to bear down. Whether you are a sonographer, a radiologist, or an ObGyn, dynamic imaging can bring the examination process into the imager’s hands.

Can you tell us more about the indications for pelvic sonography for endometriosis and what data can you give to support this?

Dr. Goldstein: There is a document titled “Ultrasound Examination of the Female Pelvis,” that was originally developed by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). In this document, there are about 19 different indications for pelvic sonography (in no defined order), and it is interesting that the first indication listed is evaluation of pelvic pain. Well, I would ask you, how do you evaluate pelvic pain with a series of anatomic images? If you have a classic ovarian endometrioma, or you have a classic hydrosalpinx, you can surmise that these are the source of the pain that the patient is reporting. But how do you properly evaluate pain with just an anatomic image? Thus, the need to use dynamic assessment.

There was a concept first introduced by my colleague, Dr. Ilan Timor, known as the sliding organ sign, that was mainly used to determine if 2 structures were adherent or separate. This involved use of the abdominal hand, liberal use of the probe moving in and out, and under real-time vision, examining the patient with the ultrasound transducer; this is the concept of dynamic ultrasound. This practice can be expanded to verify if there is pelvic tenderness and can be a significant part of the nonlaparoscopic, presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis, even when there is no ovarian endometrioma.

To support this theory, I would point you toward a classic article by E Okaro and colleagues in the British Journal of OB-GYN. This study took 120 consecutive women with chronic pelvic pain who were scheduled for laparoscopy, but performed a transvaginal ultrasound prior, and they looked for anatomic abnormalities and divided this into hard markers and soft markers. Hard markers were obvious endometriomas and hydrosalpinges, while soft markers included things like reduced ovarian mobility, site-specific pelvic tenderness, and presence of loculated peritoneal fluid in the pelvis. These were typical of chronic pelvic pain patients that ranged from late teens to almost menopausal, as the average age was about 30 years old.

Patients had experienced pain for anywhere from 6 months to 12 years, but the average was about 4 years. At laparoscopy, 58% of these patients had pelvic pathology, and 42% had a normal pelvis. Of the 58% with pathology, the overwhelming majority—about 51 of 70 women—had endometriosis alone, and another 7 had endometriosis with adhesions. A normal ultrasound, based on the absence of hard markers, was found in 96 of 120 women. Thus, 24 of the 120 women had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these hard markers. At laparoscopy, all 24 women had abnormal laparoscopies. Of those 96 women who would have had a normal ultrasound, based on the anatomic absence of some pathology, 53% had an abnormal scan based on the presence of these soft markers while the remaining women had no soft- or hard-markers suggesting any pelvic pathology. At laparoscopy, 73% of the patients with soft markers had pelvic pathology and 27% had a normal laparoscopy. Of 45 patients who had a normal, transvaginal ultrasound, 9 were found to have small evidence of endometriosis without discrete endometriomas at laparoscopy.

To summarize the study data, 100% of patients with hard markers and chronic pelvic pain had abnormal anatomy at laparoscopy, but 73% of patients who had soft markers but otherwise would have been interpreted as normal anatomic findings had evidence of pelvic pathology. Such an approach, if used, could lead to a reduction in the number of unnecessary laparoscopies.

What it really boils down to is, if you have 100 women with chronic pelvic pain, are you willing to treat 100 patients without laparoscopy, knowing that 73 are going to have a positive laparoscopy and will require treatment anyway? You would treat 27% with a pharmaceutical agent that may provide relief of their pain, or may not, depending on what the true etiology was. I would be willing to do so, as a positive predictive value of 73% makes doing that worthwhile, and I believe a majority of clinicians would agree.

Do you have any other tips or ways to improve the reader’s understanding of transvaginal ultrasound?

Dr. Goldstein: Pelvic organs have mobility. If a premenopausal woman is examined in lithotomy position, if the ovaries are freely mobile, by gravity, they are going to go lateral to the uterus and are seen immediately adjacent to the iliac vessels. But remember, iliac vessels are retroperitoneal as they are outside the peritoneal cavity. If you were to turn that patient onto all fours, so that the ovaries are freely mobile, they are going to move somewhat toward the anterior abdominal wall. When an ovary is seen in a nonanatomic position, it could be normal or it could be held up by a loop of bowel, but it may indicate adhesions. This is where this sliding organ sign and liberal use of the other hand on the lower abdomen can be extremely important. The reader should also understand that our ability to localize ovaries on ultrasound depends on the amount of folliculogenesis. Follicles are black circles that are sonolucent, because they contain fluid, so they make it easy to localize ovaries, but also their anatomic position relative to the iliac vessels. However, there is a caveat—which is, sometimes an ovary might look like it is behind the uterus and not in its normal anatomic location. When dynamic imaging is used, you are able to cajole that ovary to move lateral and sit on top of the iliac vessels, which can enable you make the proper diagnosis.

37-year-old man • cough • increasing shortness of breath • pleuritic chest pain • Dx?

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

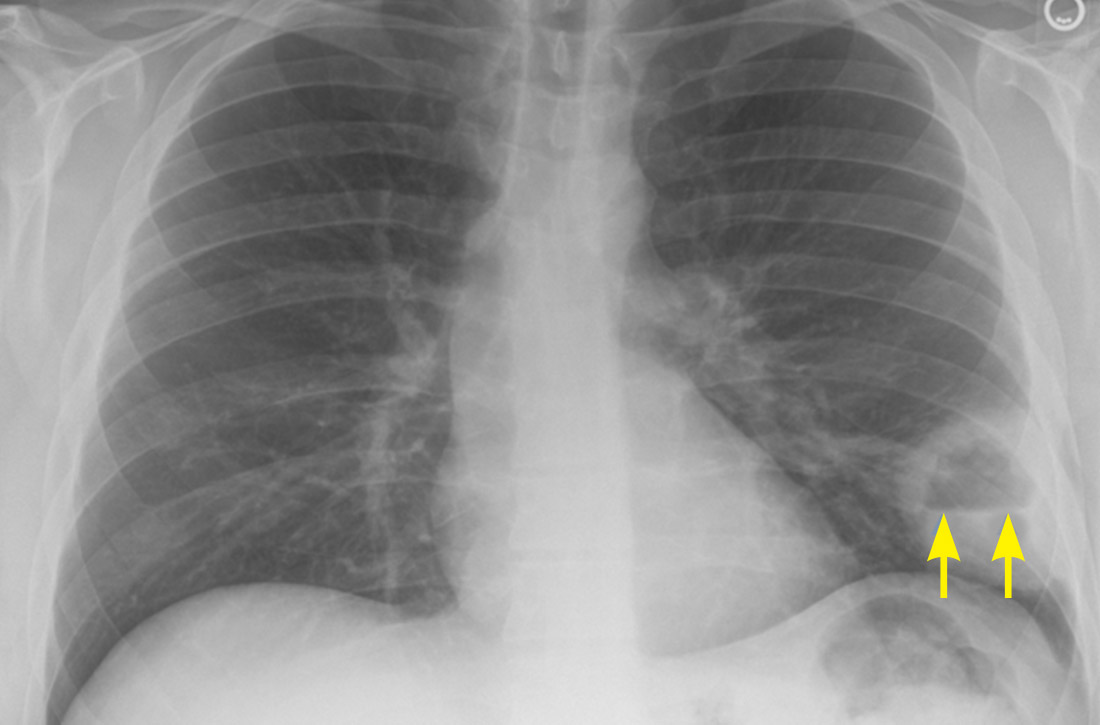

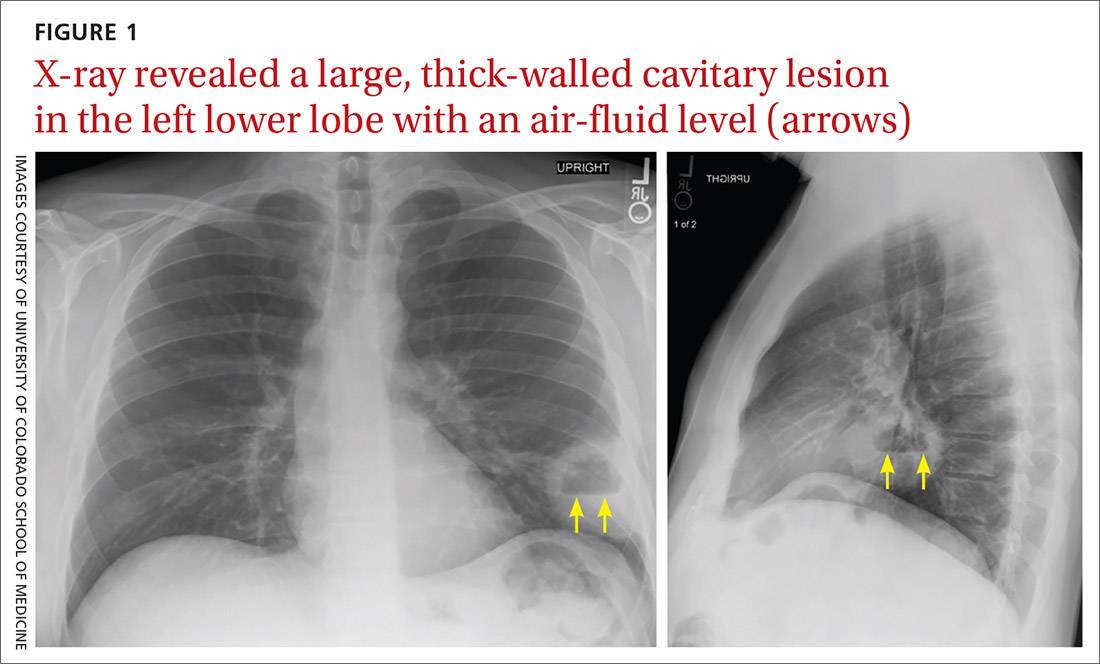

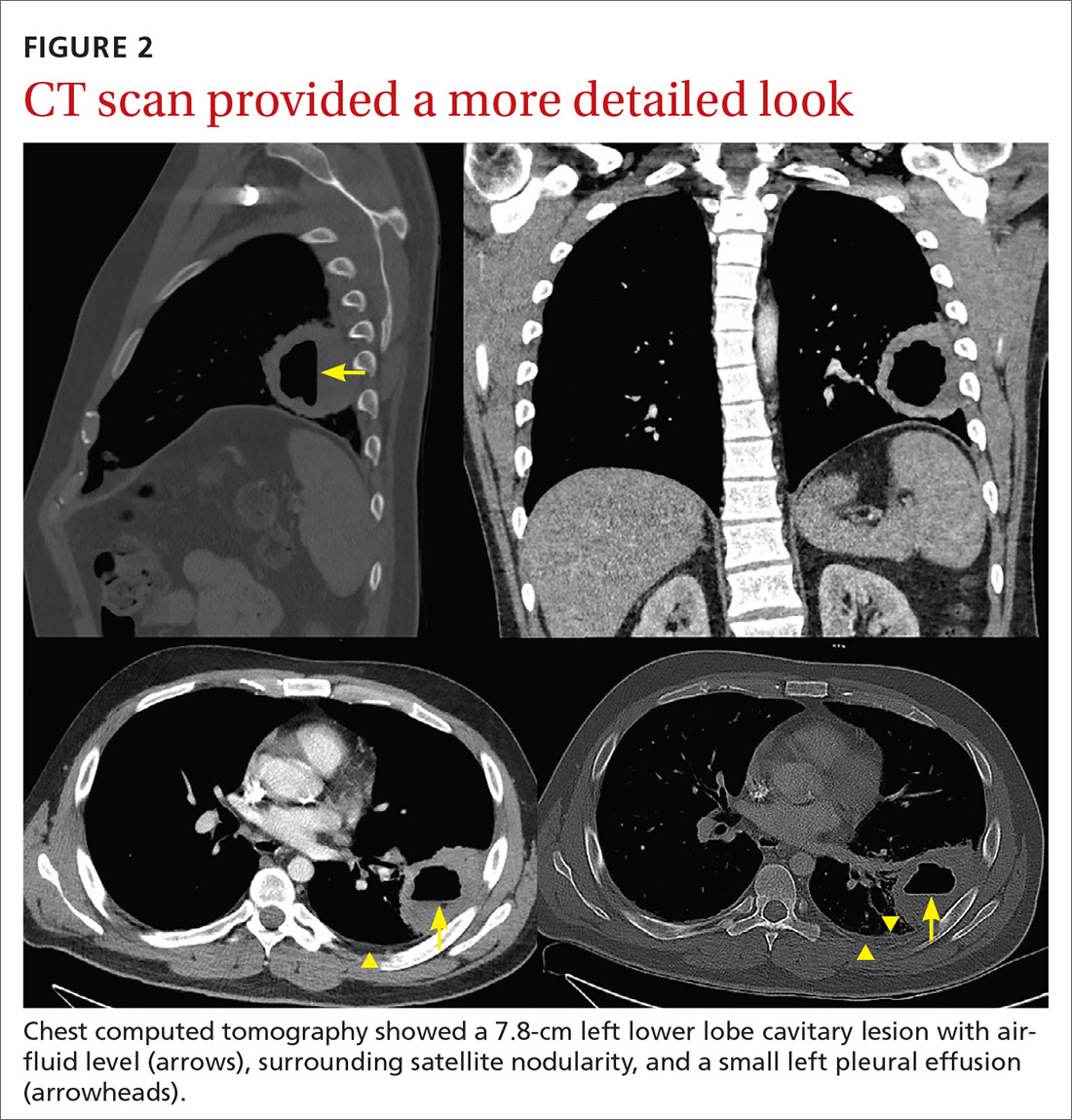

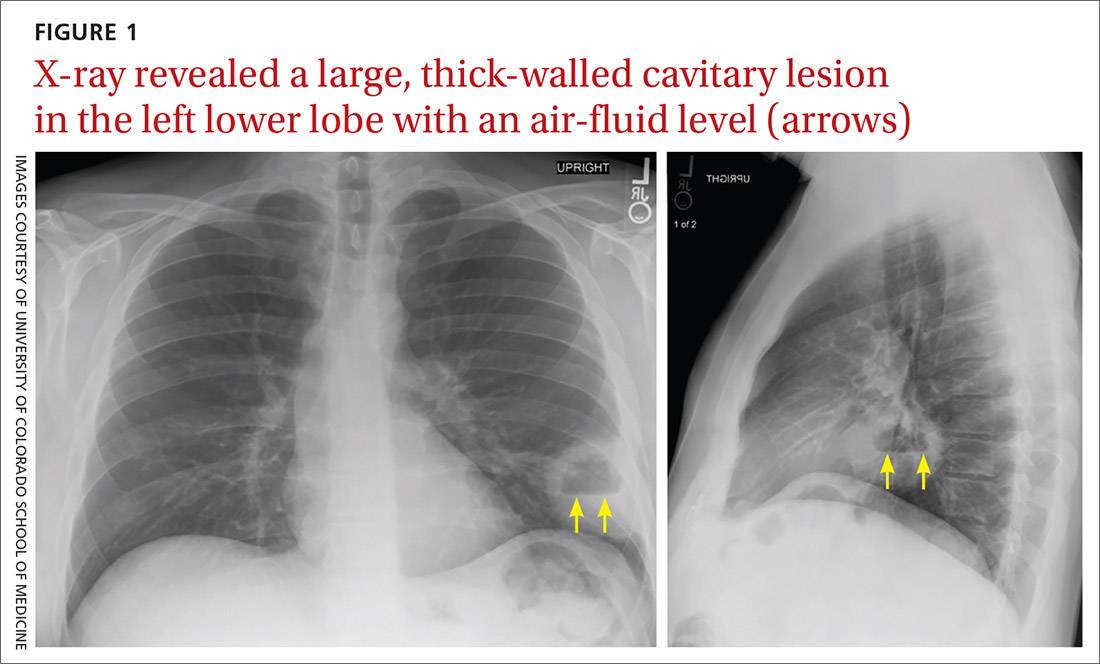

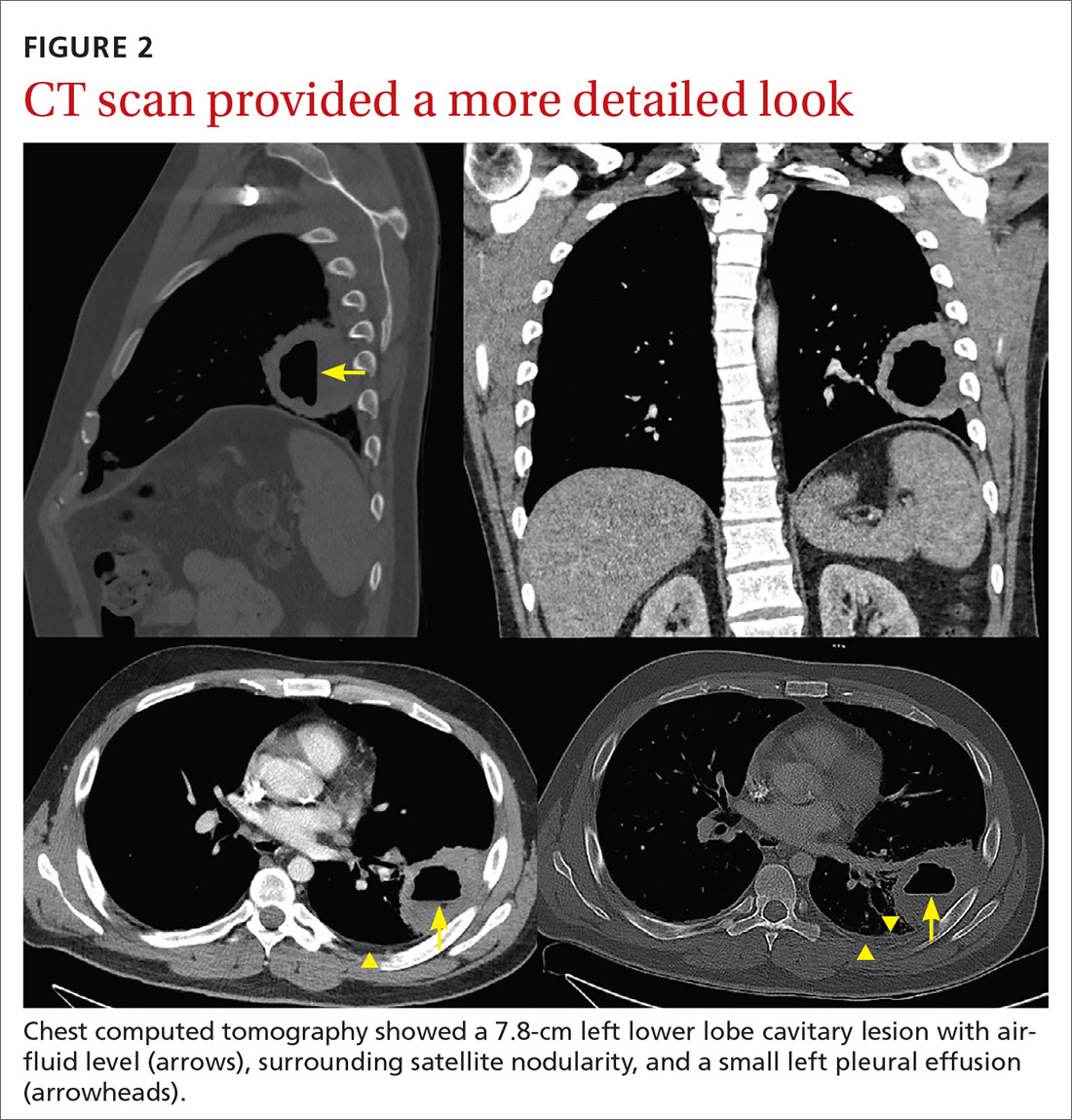

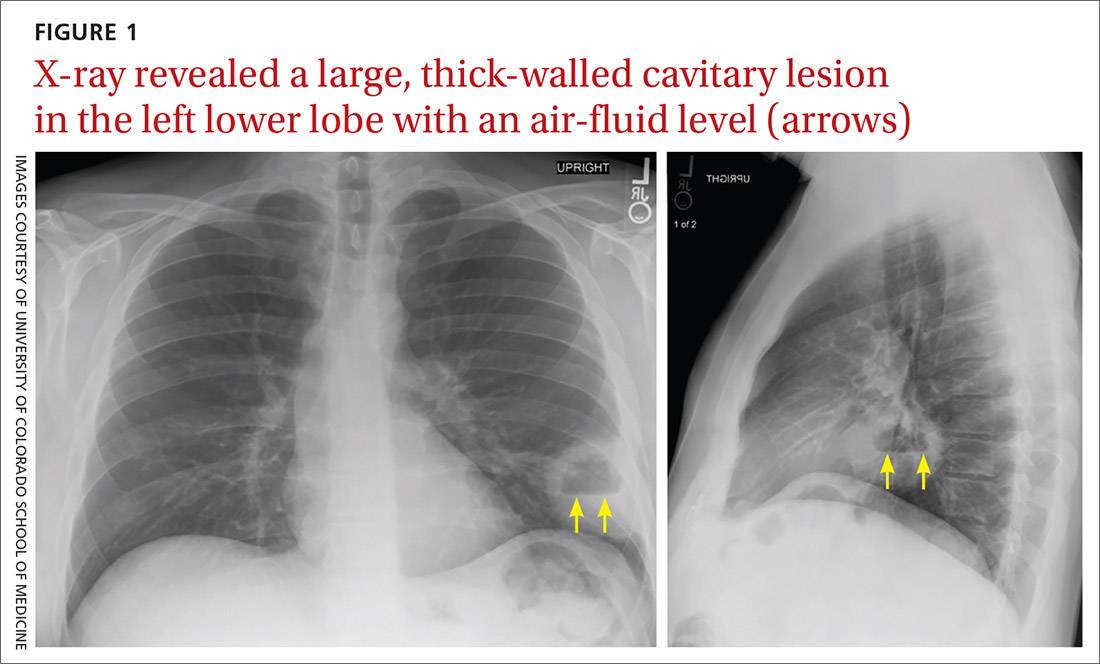

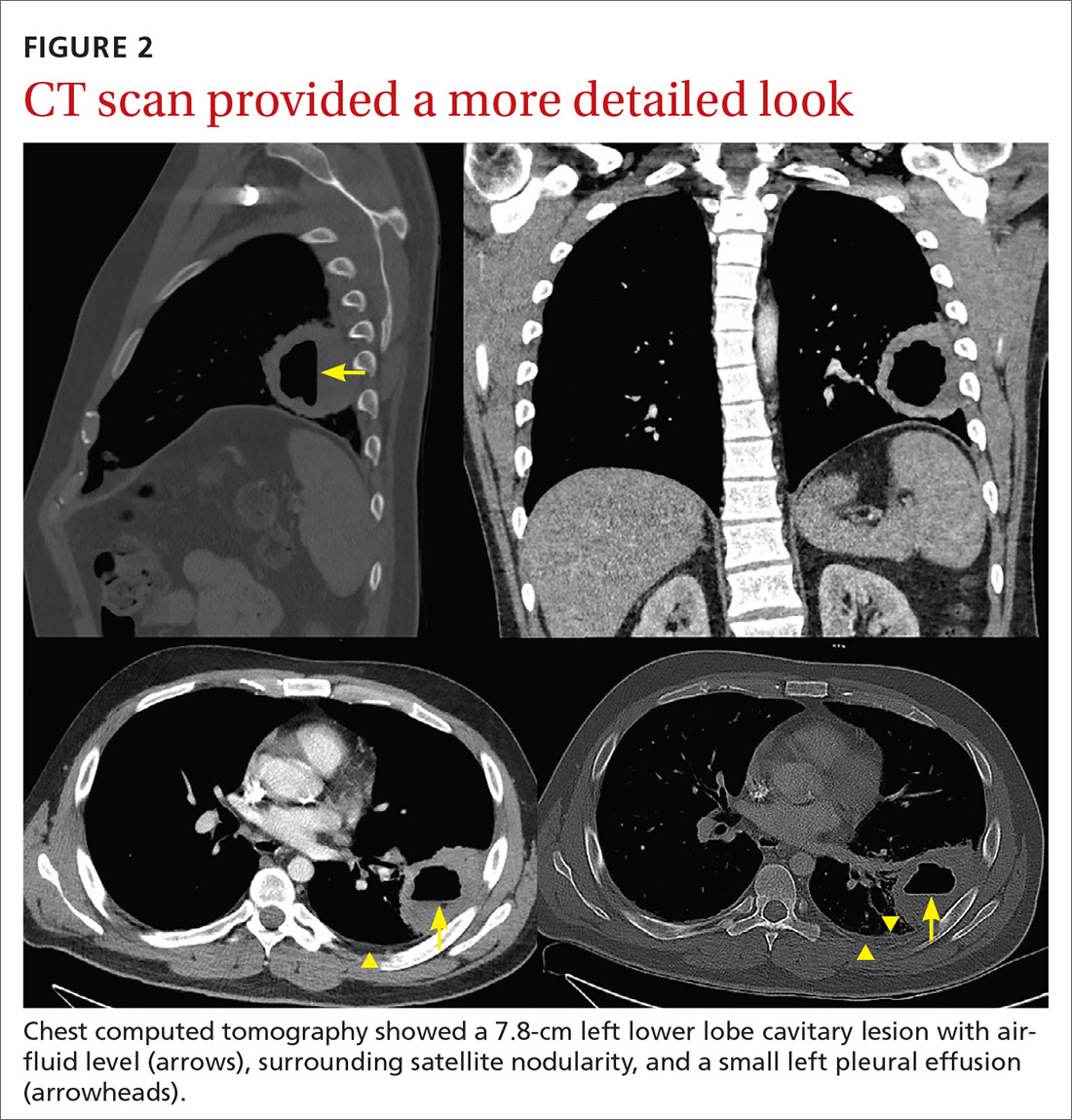

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

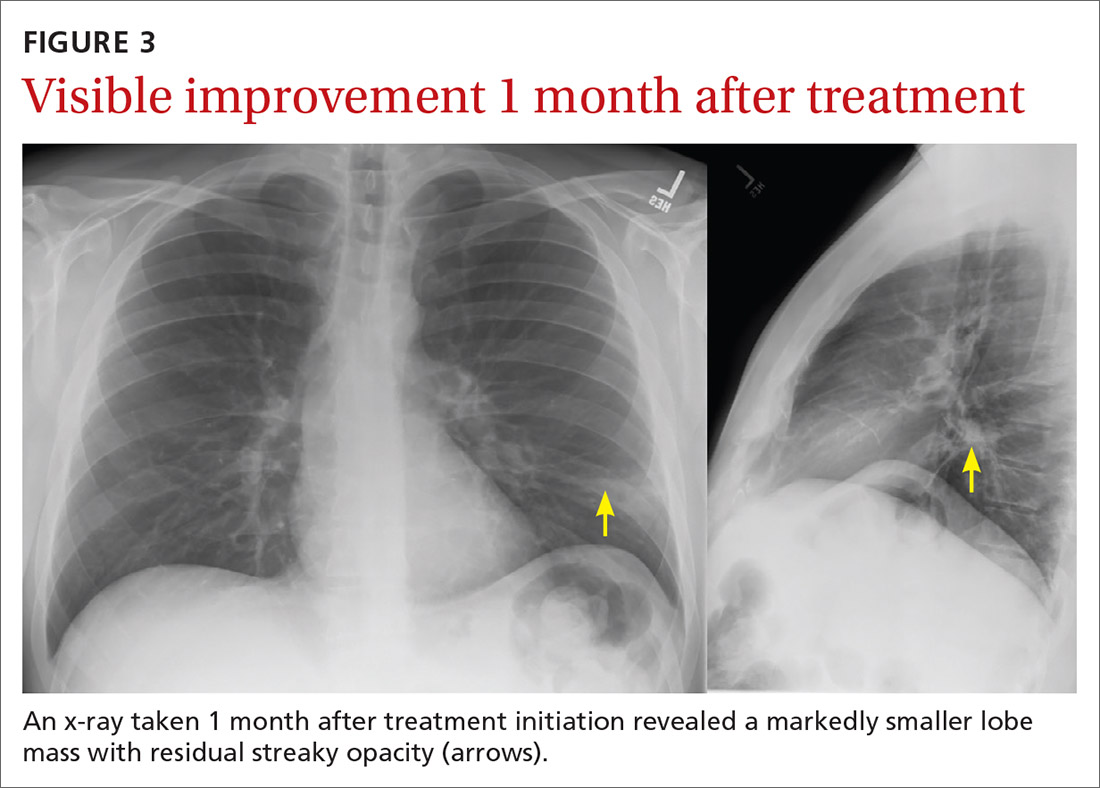

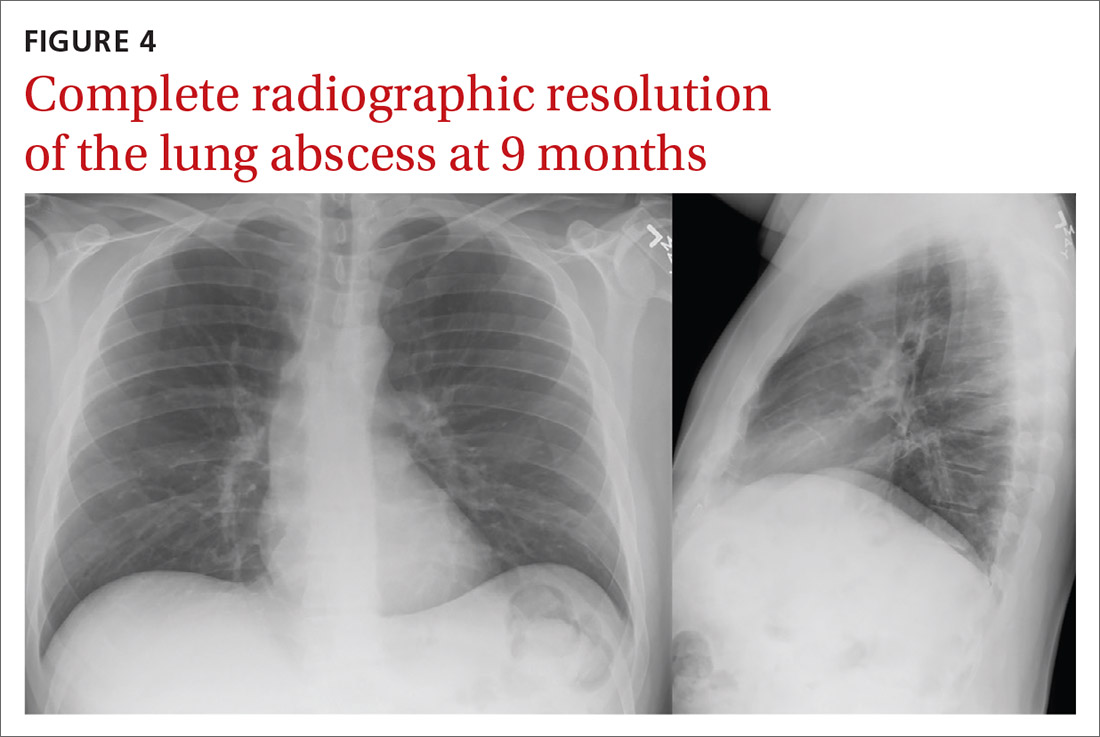

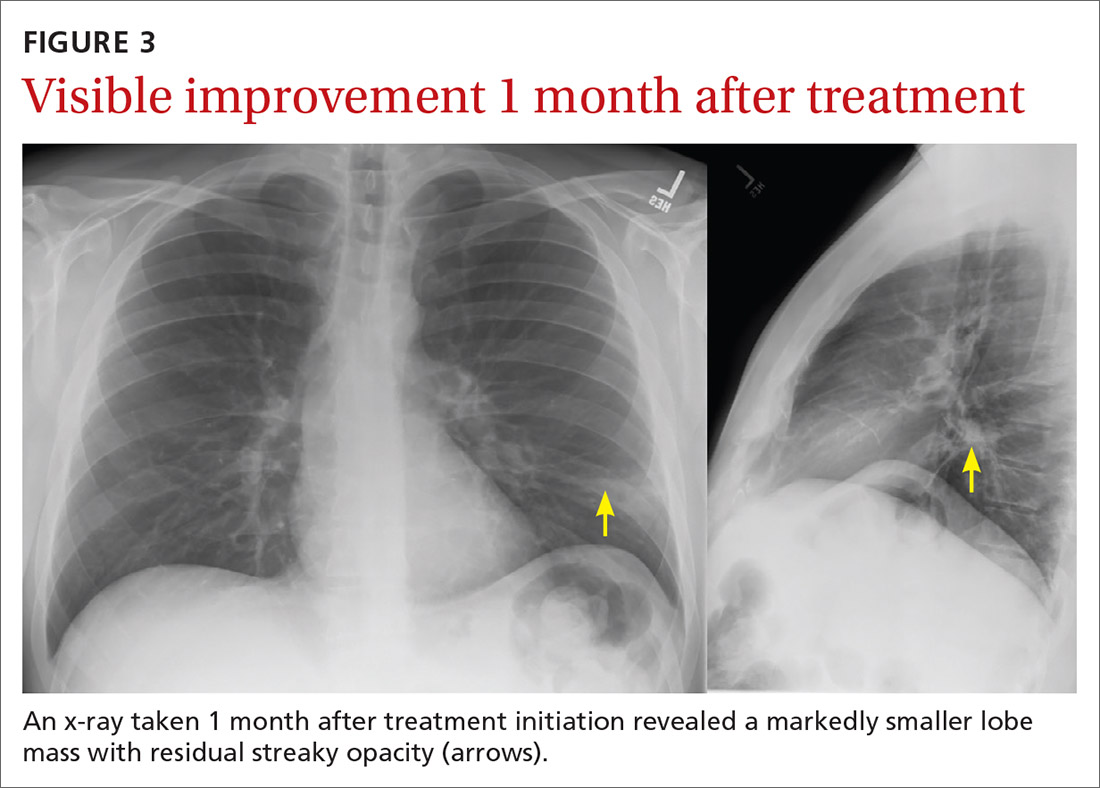

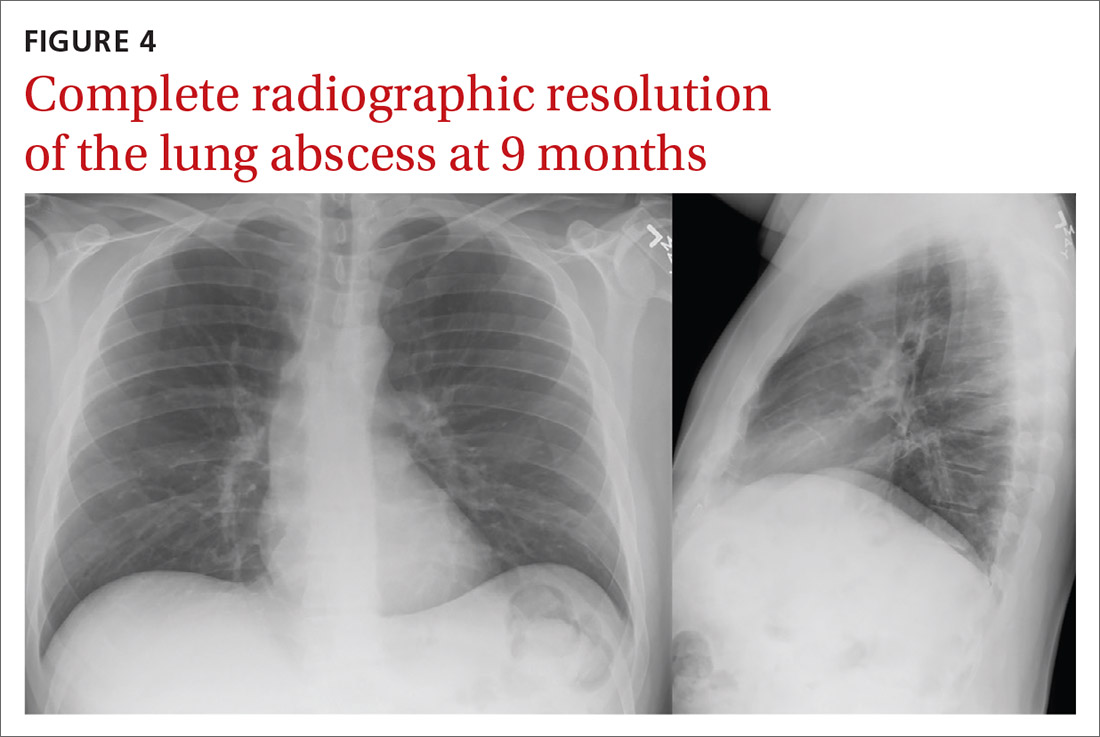

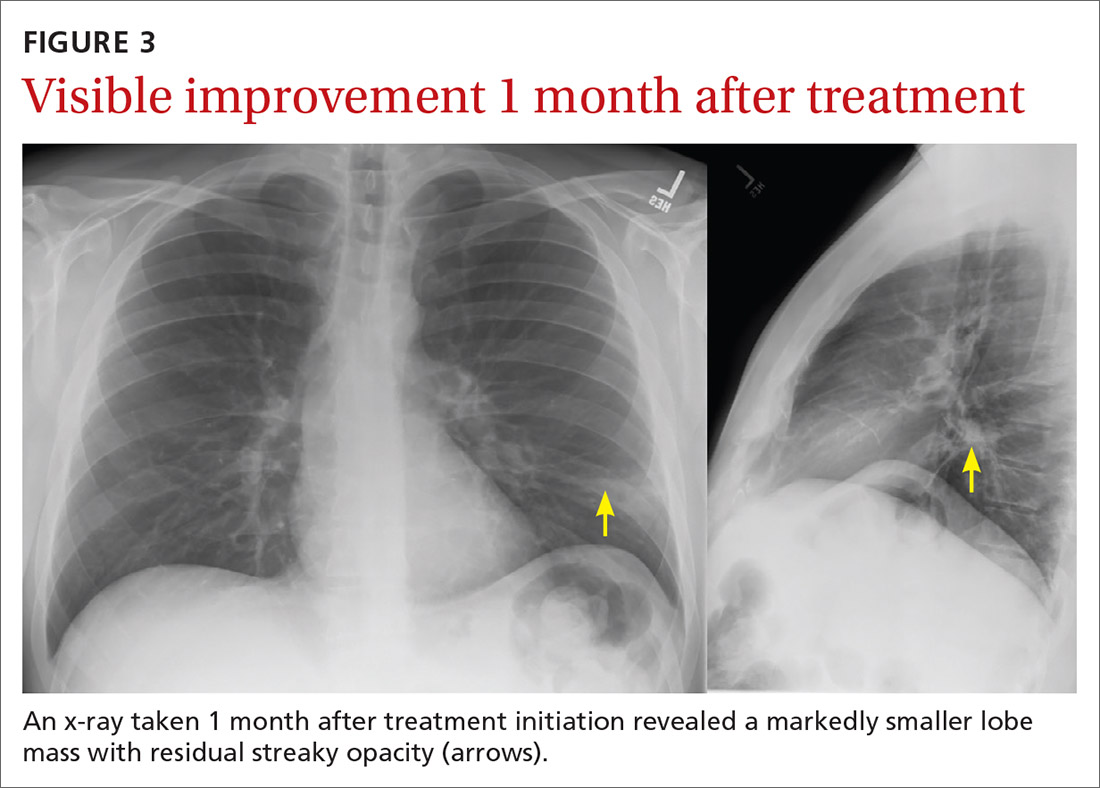

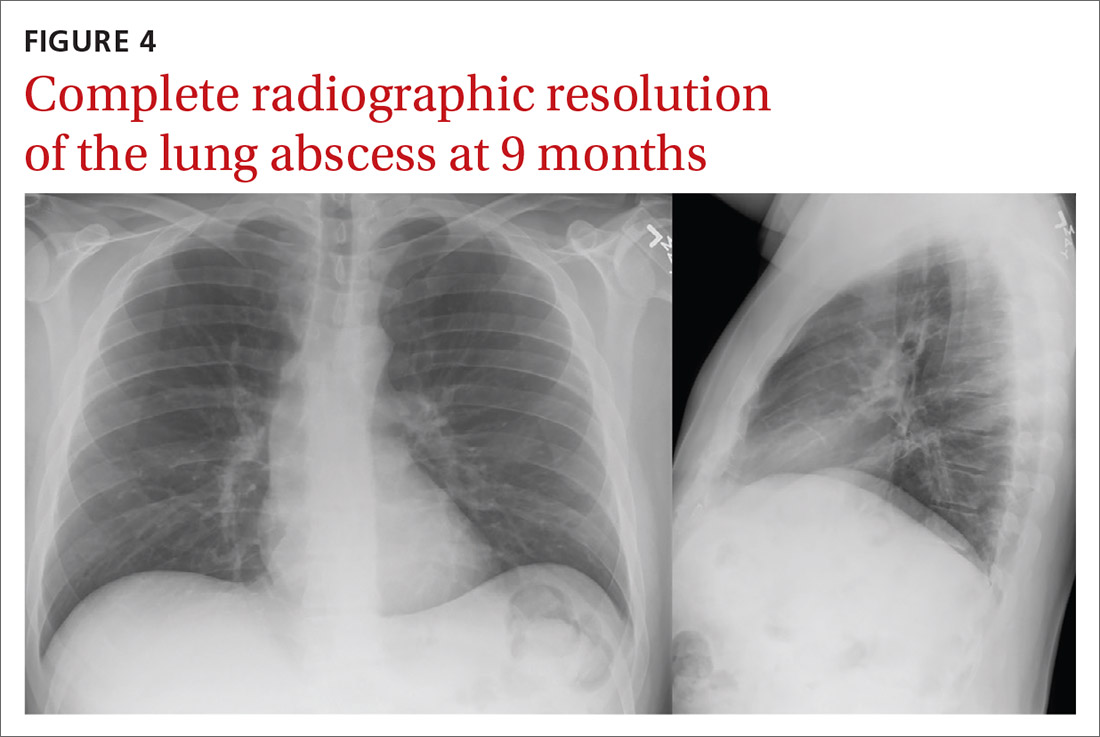

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4