User login

Gram Stain Doesn’t Improve UTI Diagnosis in the ED

TOPLINE:

Compared with other urine analysis methods, urine Gram stain has a moderate predictive value for detecting gram-negative bacteria in urine culture but does not significantly improve urinary tract infection (UTI) diagnosis in the emergency department (ED).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted an observational cohort study at the University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands, encompassing 1358 episodes across 1136 patients suspected of having a UTI.

- The study included the following predefined subgroups: patients using urinary catheters and patients with leukopenia (< 4.0×10⁹ leucocytes/L). Urine dipstick nitrite, automated urinalysis, Gram stain, and urine cultures were performed on urine samples collected from patients presenting at the ED.

- The sensitivity and specificity of Gram stain for “many” bacteria (quantified as > 15/high power field) were compared with those of urine dipstick nitrite and automated bacterial counting in urinalysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The sensitivity and specificity of Gram stain for “many” bacteria were 51.3% and 91.0%, respectively, with an accuracy of 76.8%.

- Gram stain showed a positive predictive value (PPV) of 84.7% for gram-negative rods in urine culture; however, the PPV was only 38.4% for gram-positive cocci.

- In the catheter subgroup, the presence of monomorphic bacteria quantified as “many” had a higher PPV for diagnosing a UTI than the presence of polymorphic bacteria with the same quantification.

- The overall performance of Gram stain in diagnosing a UTI in the ED was comparable to that of automated bacterial counting in urinalysis but better than that of urine dipstick nitrite.

IN PRACTICE:

“With the exception of a moderate prediction of gram-negative bacteria in the UC [urine culture], urine GS [Gram stain] does not improve UTI diagnosis at the ED compared to other urine parameters,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Stephanie J.M. Middelkoop, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands. It was published online on August 16, 2024, in Infectious Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s limitations included a small sample size within the leukopenia subgroup, which may have affected the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the potential influence of refrigeration of urine samples on bacterial growth could have affected the results. In this study, indwelling catheters were not replaced before urine sample collection, which may have affected the accuracy of UTI diagnosis in patients using catheters.

DISCLOSURES:

No conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Compared with other urine analysis methods, urine Gram stain has a moderate predictive value for detecting gram-negative bacteria in urine culture but does not significantly improve urinary tract infection (UTI) diagnosis in the emergency department (ED).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted an observational cohort study at the University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands, encompassing 1358 episodes across 1136 patients suspected of having a UTI.

- The study included the following predefined subgroups: patients using urinary catheters and patients with leukopenia (< 4.0×10⁹ leucocytes/L). Urine dipstick nitrite, automated urinalysis, Gram stain, and urine cultures were performed on urine samples collected from patients presenting at the ED.

- The sensitivity and specificity of Gram stain for “many” bacteria (quantified as > 15/high power field) were compared with those of urine dipstick nitrite and automated bacterial counting in urinalysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The sensitivity and specificity of Gram stain for “many” bacteria were 51.3% and 91.0%, respectively, with an accuracy of 76.8%.

- Gram stain showed a positive predictive value (PPV) of 84.7% for gram-negative rods in urine culture; however, the PPV was only 38.4% for gram-positive cocci.

- In the catheter subgroup, the presence of monomorphic bacteria quantified as “many” had a higher PPV for diagnosing a UTI than the presence of polymorphic bacteria with the same quantification.

- The overall performance of Gram stain in diagnosing a UTI in the ED was comparable to that of automated bacterial counting in urinalysis but better than that of urine dipstick nitrite.

IN PRACTICE:

“With the exception of a moderate prediction of gram-negative bacteria in the UC [urine culture], urine GS [Gram stain] does not improve UTI diagnosis at the ED compared to other urine parameters,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Stephanie J.M. Middelkoop, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands. It was published online on August 16, 2024, in Infectious Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s limitations included a small sample size within the leukopenia subgroup, which may have affected the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the potential influence of refrigeration of urine samples on bacterial growth could have affected the results. In this study, indwelling catheters were not replaced before urine sample collection, which may have affected the accuracy of UTI diagnosis in patients using catheters.

DISCLOSURES:

No conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Compared with other urine analysis methods, urine Gram stain has a moderate predictive value for detecting gram-negative bacteria in urine culture but does not significantly improve urinary tract infection (UTI) diagnosis in the emergency department (ED).

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted an observational cohort study at the University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands, encompassing 1358 episodes across 1136 patients suspected of having a UTI.

- The study included the following predefined subgroups: patients using urinary catheters and patients with leukopenia (< 4.0×10⁹ leucocytes/L). Urine dipstick nitrite, automated urinalysis, Gram stain, and urine cultures were performed on urine samples collected from patients presenting at the ED.

- The sensitivity and specificity of Gram stain for “many” bacteria (quantified as > 15/high power field) were compared with those of urine dipstick nitrite and automated bacterial counting in urinalysis.

TAKEAWAY:

- The sensitivity and specificity of Gram stain for “many” bacteria were 51.3% and 91.0%, respectively, with an accuracy of 76.8%.

- Gram stain showed a positive predictive value (PPV) of 84.7% for gram-negative rods in urine culture; however, the PPV was only 38.4% for gram-positive cocci.

- In the catheter subgroup, the presence of monomorphic bacteria quantified as “many” had a higher PPV for diagnosing a UTI than the presence of polymorphic bacteria with the same quantification.

- The overall performance of Gram stain in diagnosing a UTI in the ED was comparable to that of automated bacterial counting in urinalysis but better than that of urine dipstick nitrite.

IN PRACTICE:

“With the exception of a moderate prediction of gram-negative bacteria in the UC [urine culture], urine GS [Gram stain] does not improve UTI diagnosis at the ED compared to other urine parameters,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Stephanie J.M. Middelkoop, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands. It was published online on August 16, 2024, in Infectious Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s limitations included a small sample size within the leukopenia subgroup, which may have affected the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the potential influence of refrigeration of urine samples on bacterial growth could have affected the results. In this study, indwelling catheters were not replaced before urine sample collection, which may have affected the accuracy of UTI diagnosis in patients using catheters.

DISCLOSURES:

No conflicts of interest were disclosed by the authors.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Listeriosis During Pregnancy Can Be Fatal for the Fetus

Listeriosis during pregnancy, when invasive, can be fatal for the fetus, with a rate of fetal loss or neonatal death of 29%, investigators reported in an article alerting clinicians to this condition.

The article was prompted when the Reproductive Infectious Diseases team at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, “received many phone calls from concerned doctors and patients after the plant-based milk recall in early July,” Jeffrey Man Hay Wong, MD, told this news organization. “With such concerns, we updated our British Columbia guidelines for our patients but quickly realized that our recommendations would be useful across the country.”

The article was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Five Key Points

Dr. Wong and colleagues provided the following five points and recommendations:

First, invasive listeriosis (bacteremia or meningitis) in pregnancy can have major fetal consequences, including fetal loss or neonatal death in 29% of cases. Affected patients can be asymptomatic or experience gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, fevers, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or sepsis.

Second, pregnant people should avoid foods at a high risk for Listeria monocytogenes contamination, including unpasteurized dairy products, luncheon meats, refrigerated meat spreads, and prepared salads. They also should stay aware of Health Canada recalls.

Third, it is not necessary to investigate or treat patients who may have ingested contaminated food but are asymptomatic. Listeriosis can present at 2-3 months after exposure because the incubation period can be as long as 70 days.

Fourth, for patients with mild gastroenteritis or flu-like symptoms who may have ingested contaminated food, obtaining blood cultures or starting a 2-week course of oral amoxicillin (500 mg, three times daily) could be considered.

Fifth, for patients with fever and possible exposure to L monocytogenes, blood cultures should be drawn immediately, and high-dose ampicillin should be initiated, along with electronic fetal heart rate monitoring.

“While choosing safer foods in pregnancy is recommended, it is most important to be aware of Health Canada food recalls and pay attention to symptoms if you’ve ingested these foods,” said Dr. Wong. “Working with the BC Centre for Disease Control, our teams are actively monitoring for cases of listeriosis in pregnancy here in British Columbia.

“Thankfully,” he said, “there haven’t been any confirmed cases in British Columbia related to the plant-based milk recall, though the bacteria’s incubation period can be up to 70 days in pregnancy.”

No Increase Suspected

Commenting on the article, Khady Diouf, MD, director of global obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said, “It summarizes the main management, which is based mostly on expert opinion.”

US clinicians also should be reminded about listeriosis in pregnancy, she noted, pointing to “helpful guidance” from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Although the United States similarly experienced a recent listeriosis outbreak resulting from contaminated deli meats, both Dr. Wong and Dr. Diouf said that these outbreaks do not seem to signal an increase in listeriosis cases overall.

“Food-borne listeriosis seems to come in waves,” said Dr. Wong. “At a public health level, we certainly have better surveillance programs for Listeria infections. In 2023, Health Canada updated its Policy on L monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods, which emphasizes the good manufacturing practices recommended for food processing environments to identify outbreaks earlier.”

“I think we get these recalls yearly, and this has been the case for as long as I can remember,” Dr. Diouf agreed.

No funding was declared, and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Listeriosis during pregnancy, when invasive, can be fatal for the fetus, with a rate of fetal loss or neonatal death of 29%, investigators reported in an article alerting clinicians to this condition.

The article was prompted when the Reproductive Infectious Diseases team at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, “received many phone calls from concerned doctors and patients after the plant-based milk recall in early July,” Jeffrey Man Hay Wong, MD, told this news organization. “With such concerns, we updated our British Columbia guidelines for our patients but quickly realized that our recommendations would be useful across the country.”

The article was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Five Key Points

Dr. Wong and colleagues provided the following five points and recommendations:

First, invasive listeriosis (bacteremia or meningitis) in pregnancy can have major fetal consequences, including fetal loss or neonatal death in 29% of cases. Affected patients can be asymptomatic or experience gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, fevers, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or sepsis.

Second, pregnant people should avoid foods at a high risk for Listeria monocytogenes contamination, including unpasteurized dairy products, luncheon meats, refrigerated meat spreads, and prepared salads. They also should stay aware of Health Canada recalls.

Third, it is not necessary to investigate or treat patients who may have ingested contaminated food but are asymptomatic. Listeriosis can present at 2-3 months after exposure because the incubation period can be as long as 70 days.

Fourth, for patients with mild gastroenteritis or flu-like symptoms who may have ingested contaminated food, obtaining blood cultures or starting a 2-week course of oral amoxicillin (500 mg, three times daily) could be considered.

Fifth, for patients with fever and possible exposure to L monocytogenes, blood cultures should be drawn immediately, and high-dose ampicillin should be initiated, along with electronic fetal heart rate monitoring.

“While choosing safer foods in pregnancy is recommended, it is most important to be aware of Health Canada food recalls and pay attention to symptoms if you’ve ingested these foods,” said Dr. Wong. “Working with the BC Centre for Disease Control, our teams are actively monitoring for cases of listeriosis in pregnancy here in British Columbia.

“Thankfully,” he said, “there haven’t been any confirmed cases in British Columbia related to the plant-based milk recall, though the bacteria’s incubation period can be up to 70 days in pregnancy.”

No Increase Suspected

Commenting on the article, Khady Diouf, MD, director of global obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said, “It summarizes the main management, which is based mostly on expert opinion.”

US clinicians also should be reminded about listeriosis in pregnancy, she noted, pointing to “helpful guidance” from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Although the United States similarly experienced a recent listeriosis outbreak resulting from contaminated deli meats, both Dr. Wong and Dr. Diouf said that these outbreaks do not seem to signal an increase in listeriosis cases overall.

“Food-borne listeriosis seems to come in waves,” said Dr. Wong. “At a public health level, we certainly have better surveillance programs for Listeria infections. In 2023, Health Canada updated its Policy on L monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods, which emphasizes the good manufacturing practices recommended for food processing environments to identify outbreaks earlier.”

“I think we get these recalls yearly, and this has been the case for as long as I can remember,” Dr. Diouf agreed.

No funding was declared, and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Listeriosis during pregnancy, when invasive, can be fatal for the fetus, with a rate of fetal loss or neonatal death of 29%, investigators reported in an article alerting clinicians to this condition.

The article was prompted when the Reproductive Infectious Diseases team at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, “received many phone calls from concerned doctors and patients after the plant-based milk recall in early July,” Jeffrey Man Hay Wong, MD, told this news organization. “With such concerns, we updated our British Columbia guidelines for our patients but quickly realized that our recommendations would be useful across the country.”

The article was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Five Key Points

Dr. Wong and colleagues provided the following five points and recommendations:

First, invasive listeriosis (bacteremia or meningitis) in pregnancy can have major fetal consequences, including fetal loss or neonatal death in 29% of cases. Affected patients can be asymptomatic or experience gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, fevers, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or sepsis.

Second, pregnant people should avoid foods at a high risk for Listeria monocytogenes contamination, including unpasteurized dairy products, luncheon meats, refrigerated meat spreads, and prepared salads. They also should stay aware of Health Canada recalls.

Third, it is not necessary to investigate or treat patients who may have ingested contaminated food but are asymptomatic. Listeriosis can present at 2-3 months after exposure because the incubation period can be as long as 70 days.

Fourth, for patients with mild gastroenteritis or flu-like symptoms who may have ingested contaminated food, obtaining blood cultures or starting a 2-week course of oral amoxicillin (500 mg, three times daily) could be considered.

Fifth, for patients with fever and possible exposure to L monocytogenes, blood cultures should be drawn immediately, and high-dose ampicillin should be initiated, along with electronic fetal heart rate monitoring.

“While choosing safer foods in pregnancy is recommended, it is most important to be aware of Health Canada food recalls and pay attention to symptoms if you’ve ingested these foods,” said Dr. Wong. “Working with the BC Centre for Disease Control, our teams are actively monitoring for cases of listeriosis in pregnancy here in British Columbia.

“Thankfully,” he said, “there haven’t been any confirmed cases in British Columbia related to the plant-based milk recall, though the bacteria’s incubation period can be up to 70 days in pregnancy.”

No Increase Suspected

Commenting on the article, Khady Diouf, MD, director of global obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said, “It summarizes the main management, which is based mostly on expert opinion.”

US clinicians also should be reminded about listeriosis in pregnancy, she noted, pointing to “helpful guidance” from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Although the United States similarly experienced a recent listeriosis outbreak resulting from contaminated deli meats, both Dr. Wong and Dr. Diouf said that these outbreaks do not seem to signal an increase in listeriosis cases overall.

“Food-borne listeriosis seems to come in waves,” said Dr. Wong. “At a public health level, we certainly have better surveillance programs for Listeria infections. In 2023, Health Canada updated its Policy on L monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods, which emphasizes the good manufacturing practices recommended for food processing environments to identify outbreaks earlier.”

“I think we get these recalls yearly, and this has been the case for as long as I can remember,” Dr. Diouf agreed.

No funding was declared, and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

Multiple Draining Sinus Tracts on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

An injury sustained in a wet environment that results in chronic indolent abscesses, nodules, or draining sinus tracts suggests a mycobacterial infection. In our patient, a culture revealed MycobacteriuM fortuitum, which is classified in the rapid grower nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) group, along with Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus.1 The patient’s history of skin injury while cutting wet grass and the common presence of M fortuitum in the environment suggested that the organism entered the wound. The patient healed completely following surgical excision and a 2-month course of clarithromycin 1 g daily and rifampin 600 mg daily.

MycobacteriuM fortuitum was first isolated from an amphibian source in 1905 and later identified in a human with cutaneous infection in 1938. It commonly is found in soil and water.2 Skin and soft-tissue infections with M fortuitum usually are acquired from direct entry of the organism through a damaged skin barrier from trauma, medical injection, surgery, or tattoo placement.2,3

Skin lesions caused by NTM often are nonspecific and can mimic a variety of other dermatologic conditions, making clinical diagnosis challenging. As such, cutaneous manifestations of M fortuitum infection can include recurrent cutaneous abscesses, nodular lesions, chronic discharging sinuses, cellulitis, and surgical site infections.4 Although cutaneous infection with M fortuitum classically manifests with a single subcutaneous nodule at the site of trauma or surgery,5 it also can manifest as multiple draining sinus tracts, as seen in our patient. Hence, the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous NTM infection is challenging, especially when M fortuitum skin manifestations can take up to 4 to 6 weeks to develop after inoculation. Diagnosis often requires a detailed patient history, tissue cultures, and histopathology.5

In recent years, rapid detection with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques has been employed more widely. Notably, a molecular system based on multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting was shown to have a sensitivity of up to 54% for distinguishing M fortuitum from other NTM.6 More recently, a 2-step real-time PCR method has demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for differentiating NTM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and identifying the causative NTM agent.7

Compared to immunocompetent individuals, those who are immunocompromised are more susceptible to less pathogenic strains of NTM, which can cause dissemination and lead to tenosynovitis, myositis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis.8-12 Nonetheless, cases of infections with NTM—including M fortuitum—are becoming harder to treat. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms and point mutations have been demonstrated in the ribosomal RNA methylase gene erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in the rrl gene related to linezolid resistance.13 Due to increasing inducible resistance to common classes of antibiotics, such as macrolides and linezolid, treatment of M fortuitum requires multidrug regimens.13,14 Drug susceptibility testing also may be required, as M fortuitum has shown low resistance to tigecycline, tetracycline, cefmetazole, imipenem, and aminoglycosides (eg, amikacin, tobramycin, neomycin, gentamycin). Surgery is an important adjunctive tool in treating M fortuitum infections; patients with a single lesion are more likely to undergo surgical treatment alone or in combination with antibiotic therapy.15 More recently, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy has been explored as an alternative to eliminate NTM, including M fortuitum.16

The differential diagnosis for skin lesions manifesting with draining fistulae and sinus tracts includes conditions with infectious (cellulitis and chromomycosis) and inflammatory (pyoderma gangrenosum [PG] and hidradenitis suppurativa [HS]) causes.

Cellulitis is a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that predominantly is caused by gram-positive organisms such as β-hemolytic streptococci.17 Clinical manifestations include acute skin erythema, swelling, tenderness, and warmth. The legs are the most common sites of infection, but any area of the skin can be involved.17 Cellulitis comprises 10% of all infectious disease hospitalizations and up to 11% of all dermatologic admissions.18,19 It frequently is misdiagnosed, perhaps due to the lack of a reliable confirmatory laboratory test or imaging study, in addition to the plethora of diseases that mimic cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, contact dermatitis, lymphedema, eosinophilic cellulitis, and papular urticaria.20,21 The consequences of misdiagnosis include but are not limited to unnecessary hospitalizations, inappropriate antibiotic use, and delayed management of the disease; thus, there is an urgent need for a reliable standard test to confirm the diagnosis, especially among nonspecialist physicians. 20 Most patients with uncomplicated cellulitis can be treated with empiric oral antibiotics that target β-hemolytic streptococci (ie, penicillin V potassium, amoxicillin).17 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus coverage generally is unnecessary for nonpurulent cellulitis, but clinicians can consider adding amoxicillin-clavulanate, dicloxacillin, and cephalexin to the regimen. For purulent cellulitis, incision and drainage should be performed. In severe cases that manifest with sepsis, altered mental status, or hemodynamic instability, inpatient management is required.17

Chromomycosis (also known as chromoblastomycosis) is a chronic, indolent, granulomatous, suppurative mycosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue22 that is caused by traumatic inoculation of various fungi of the order Chaetothyriales and family Herpotrichiellaceae, which are present in soil, plants, and decomposing wood. Chromomycosis is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions.23,24 Clinically, it manifests as oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic lesions around an infection site that can manifest as papules with centrifugal growth evolving into nodular, verrucous, plaque, tumoral, or atrophic forms.22 Diagnosis is made with direct microscopy using potassium hydroxide, which reveals muriform bodies. Fungal culture in Sabouraud agar also can be used to isolate the causative pathogen.22 Unfortunately, chromomycosis is difficult to treat, with low cure rates and high relapse rates. Antifungal agents combined with surgery, cryotherapy, or thermotherapy often are used, with cure rates ranging from 15% to 80%.22,25

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a reactive noninfectious inflammatory dermatosis associated with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. The exact etiology is not clearly understood, but it generally is considered an autoinflammatory disorder.26 The most common form—classical PG—occurs in approximately 85% of cases and manifests as a painful erythematous lesion that progresses to a blistered or necrotic ulcer. It primarily affects the lower legs but can occur in other body sites.27 The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms after excluding other similar conditions; histopathology of biopsied wound tissues often are required for confirmation. Treatment of PG starts with fast-acting immunosuppressive drugs (corticosteroids and/or cyclosporine) followed by slowacting immunosuppressive drugs (biologics).26

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic recurrent disease of the hair follicle unit that develops after puberty.28 Clinically, HS manifests with painful nodules, abscesses, chronically draining fistulas, and scarring in areas of the body rich in apocrine glands.29,30 Treatment of HS is challenging due to its diverse clinical manifestations and unclear etiology. Topical therapy, systemic treatments, biologic agents, surgery, and light therapy have shown variable results.28,31

- Franco-Paredes C, Marcos LA, Henao-Martínez AF, et al. Cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;32: E00069-18. doi:10.1128/CMR.00069-18

- Brown TH. The rapidly growing mycobacteria—MycobacteriuM fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Infect Control. 1985;6:283-238. doi:10.1017/s0195941700061762

- Hooper J; Beltrami EJ; Santoro F; et al. Remember the fite: a case of cutaneous MycobacteriuM fortuitum infection. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:214-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002336

- Franco-Paredes C, Chastain DB, Allen L, et al. Overview of cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:228-232. doi:10.1007/s40475-018-0161-7

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-77. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.017

- Peixoto ADS, Montenegro LML, Lima AS, et al. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria species by multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:E20200211. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0211-2020

- Park J, Kwak N, Chae JC, et al. A two-step real-time PCR method to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and six dominant nontuberculous mycobacterial infections from clinical specimens. Microbiol Spectr. 2023:E0160623. doi:10.1128/spectrum.01606-23

- Fowler J, Mahlen SD. Localized cutaneous infections in immunocompetent individuals due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1106-1109. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0203-RS

- Gardini G, Gregori N, Matteelli A, et al. Mycobacterial skin infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022;35:79-87. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000820

- Wang SH, Pancholi P. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16:438. doi:10.1007/s11908-014-0438-5

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Mougari F, Guglielmetti L, Raskine L, et al. Infections caused by Mycobacterium abscessus: epidemiology, diagnostic tools and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14:1139-1154. doi:10.1080/14787210.201 6.1238304

- Tu HZ, Lee HS, Chen YS, et al. High rates of antimicrobial resistance in rapidly growing mycobacterial infections in Taiwan. Pathogens. 2022;11:969. doi:10.3390/pathogens11090969

- Hashemzadeh M, Zadegan Dezfuli AA, Khosravi AD, et al. F requency of mutations in erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in rrl related to linezolid resistance in clinical isolates of MycobacteriuM fortuitum in Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2023;70:167-176. doi:10.1556/030.2023.02020

- Uslan DZ, Kowalski TJ, Wengenack NL, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria: comparison of clinical features, treatment, and susceptibility. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1287-1292. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1287

- Miretti M, Juri L, Peralta A, et al. Photoinactivation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria using Zn-phthalocyanine loaded into liposomes. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2022;136:102247. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2022.102247

- Bystritsky RJ. Cellulitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:49-60. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2020.10.002

- Christensen K, Holman R, Steiner C, et al. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1025-1035. doi:10.1086/605562

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2020.07.055

- Cutler TS, Jannat-Khah DP, Kam B, et al. Prevalence of misdiagnosis of cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2023;18:254-261. doi:10.1002/jhm.12977

- Keller EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-52. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11121

- Brito AC, Bittencourt MJS. Chromoblastomycosis: an etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:495-506. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187321

- McGinnis MR. Chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: new concepts, diagnosis, and mycology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:1-16.

- Rubin HA, Bruce S, Rosen T, et al. Evidence for percutaneous inoculation as the mode of transmission for chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:951-954.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís V, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Maverakis E, Marzano AV, Le ST, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:81. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0213-x

- George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum—a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:224-228. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-224

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Daxhelet M, Suppa M, White J, et al. Proposed definitions of typical lesions in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2020;236:431-438. doi:10.1159/000507348

- Amat-Samaranch V, Agut-Busquet E, Vilarrasa E, et al. New perspectives on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211055920. doi:10.1177/20406223211055920

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

An injury sustained in a wet environment that results in chronic indolent abscesses, nodules, or draining sinus tracts suggests a mycobacterial infection. In our patient, a culture revealed MycobacteriuM fortuitum, which is classified in the rapid grower nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) group, along with Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus.1 The patient’s history of skin injury while cutting wet grass and the common presence of M fortuitum in the environment suggested that the organism entered the wound. The patient healed completely following surgical excision and a 2-month course of clarithromycin 1 g daily and rifampin 600 mg daily.

MycobacteriuM fortuitum was first isolated from an amphibian source in 1905 and later identified in a human with cutaneous infection in 1938. It commonly is found in soil and water.2 Skin and soft-tissue infections with M fortuitum usually are acquired from direct entry of the organism through a damaged skin barrier from trauma, medical injection, surgery, or tattoo placement.2,3

Skin lesions caused by NTM often are nonspecific and can mimic a variety of other dermatologic conditions, making clinical diagnosis challenging. As such, cutaneous manifestations of M fortuitum infection can include recurrent cutaneous abscesses, nodular lesions, chronic discharging sinuses, cellulitis, and surgical site infections.4 Although cutaneous infection with M fortuitum classically manifests with a single subcutaneous nodule at the site of trauma or surgery,5 it also can manifest as multiple draining sinus tracts, as seen in our patient. Hence, the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous NTM infection is challenging, especially when M fortuitum skin manifestations can take up to 4 to 6 weeks to develop after inoculation. Diagnosis often requires a detailed patient history, tissue cultures, and histopathology.5

In recent years, rapid detection with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques has been employed more widely. Notably, a molecular system based on multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting was shown to have a sensitivity of up to 54% for distinguishing M fortuitum from other NTM.6 More recently, a 2-step real-time PCR method has demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for differentiating NTM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and identifying the causative NTM agent.7

Compared to immunocompetent individuals, those who are immunocompromised are more susceptible to less pathogenic strains of NTM, which can cause dissemination and lead to tenosynovitis, myositis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis.8-12 Nonetheless, cases of infections with NTM—including M fortuitum—are becoming harder to treat. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms and point mutations have been demonstrated in the ribosomal RNA methylase gene erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in the rrl gene related to linezolid resistance.13 Due to increasing inducible resistance to common classes of antibiotics, such as macrolides and linezolid, treatment of M fortuitum requires multidrug regimens.13,14 Drug susceptibility testing also may be required, as M fortuitum has shown low resistance to tigecycline, tetracycline, cefmetazole, imipenem, and aminoglycosides (eg, amikacin, tobramycin, neomycin, gentamycin). Surgery is an important adjunctive tool in treating M fortuitum infections; patients with a single lesion are more likely to undergo surgical treatment alone or in combination with antibiotic therapy.15 More recently, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy has been explored as an alternative to eliminate NTM, including M fortuitum.16

The differential diagnosis for skin lesions manifesting with draining fistulae and sinus tracts includes conditions with infectious (cellulitis and chromomycosis) and inflammatory (pyoderma gangrenosum [PG] and hidradenitis suppurativa [HS]) causes.

Cellulitis is a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that predominantly is caused by gram-positive organisms such as β-hemolytic streptococci.17 Clinical manifestations include acute skin erythema, swelling, tenderness, and warmth. The legs are the most common sites of infection, but any area of the skin can be involved.17 Cellulitis comprises 10% of all infectious disease hospitalizations and up to 11% of all dermatologic admissions.18,19 It frequently is misdiagnosed, perhaps due to the lack of a reliable confirmatory laboratory test or imaging study, in addition to the plethora of diseases that mimic cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, contact dermatitis, lymphedema, eosinophilic cellulitis, and papular urticaria.20,21 The consequences of misdiagnosis include but are not limited to unnecessary hospitalizations, inappropriate antibiotic use, and delayed management of the disease; thus, there is an urgent need for a reliable standard test to confirm the diagnosis, especially among nonspecialist physicians. 20 Most patients with uncomplicated cellulitis can be treated with empiric oral antibiotics that target β-hemolytic streptococci (ie, penicillin V potassium, amoxicillin).17 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus coverage generally is unnecessary for nonpurulent cellulitis, but clinicians can consider adding amoxicillin-clavulanate, dicloxacillin, and cephalexin to the regimen. For purulent cellulitis, incision and drainage should be performed. In severe cases that manifest with sepsis, altered mental status, or hemodynamic instability, inpatient management is required.17

Chromomycosis (also known as chromoblastomycosis) is a chronic, indolent, granulomatous, suppurative mycosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue22 that is caused by traumatic inoculation of various fungi of the order Chaetothyriales and family Herpotrichiellaceae, which are present in soil, plants, and decomposing wood. Chromomycosis is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions.23,24 Clinically, it manifests as oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic lesions around an infection site that can manifest as papules with centrifugal growth evolving into nodular, verrucous, plaque, tumoral, or atrophic forms.22 Diagnosis is made with direct microscopy using potassium hydroxide, which reveals muriform bodies. Fungal culture in Sabouraud agar also can be used to isolate the causative pathogen.22 Unfortunately, chromomycosis is difficult to treat, with low cure rates and high relapse rates. Antifungal agents combined with surgery, cryotherapy, or thermotherapy often are used, with cure rates ranging from 15% to 80%.22,25

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a reactive noninfectious inflammatory dermatosis associated with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. The exact etiology is not clearly understood, but it generally is considered an autoinflammatory disorder.26 The most common form—classical PG—occurs in approximately 85% of cases and manifests as a painful erythematous lesion that progresses to a blistered or necrotic ulcer. It primarily affects the lower legs but can occur in other body sites.27 The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms after excluding other similar conditions; histopathology of biopsied wound tissues often are required for confirmation. Treatment of PG starts with fast-acting immunosuppressive drugs (corticosteroids and/or cyclosporine) followed by slowacting immunosuppressive drugs (biologics).26

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic recurrent disease of the hair follicle unit that develops after puberty.28 Clinically, HS manifests with painful nodules, abscesses, chronically draining fistulas, and scarring in areas of the body rich in apocrine glands.29,30 Treatment of HS is challenging due to its diverse clinical manifestations and unclear etiology. Topical therapy, systemic treatments, biologic agents, surgery, and light therapy have shown variable results.28,31

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

An injury sustained in a wet environment that results in chronic indolent abscesses, nodules, or draining sinus tracts suggests a mycobacterial infection. In our patient, a culture revealed MycobacteriuM fortuitum, which is classified in the rapid grower nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) group, along with Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus.1 The patient’s history of skin injury while cutting wet grass and the common presence of M fortuitum in the environment suggested that the organism entered the wound. The patient healed completely following surgical excision and a 2-month course of clarithromycin 1 g daily and rifampin 600 mg daily.

MycobacteriuM fortuitum was first isolated from an amphibian source in 1905 and later identified in a human with cutaneous infection in 1938. It commonly is found in soil and water.2 Skin and soft-tissue infections with M fortuitum usually are acquired from direct entry of the organism through a damaged skin barrier from trauma, medical injection, surgery, or tattoo placement.2,3

Skin lesions caused by NTM often are nonspecific and can mimic a variety of other dermatologic conditions, making clinical diagnosis challenging. As such, cutaneous manifestations of M fortuitum infection can include recurrent cutaneous abscesses, nodular lesions, chronic discharging sinuses, cellulitis, and surgical site infections.4 Although cutaneous infection with M fortuitum classically manifests with a single subcutaneous nodule at the site of trauma or surgery,5 it also can manifest as multiple draining sinus tracts, as seen in our patient. Hence, the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous NTM infection is challenging, especially when M fortuitum skin manifestations can take up to 4 to 6 weeks to develop after inoculation. Diagnosis often requires a detailed patient history, tissue cultures, and histopathology.5

In recent years, rapid detection with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques has been employed more widely. Notably, a molecular system based on multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting was shown to have a sensitivity of up to 54% for distinguishing M fortuitum from other NTM.6 More recently, a 2-step real-time PCR method has demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for differentiating NTM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and identifying the causative NTM agent.7

Compared to immunocompetent individuals, those who are immunocompromised are more susceptible to less pathogenic strains of NTM, which can cause dissemination and lead to tenosynovitis, myositis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis.8-12 Nonetheless, cases of infections with NTM—including M fortuitum—are becoming harder to treat. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms and point mutations have been demonstrated in the ribosomal RNA methylase gene erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in the rrl gene related to linezolid resistance.13 Due to increasing inducible resistance to common classes of antibiotics, such as macrolides and linezolid, treatment of M fortuitum requires multidrug regimens.13,14 Drug susceptibility testing also may be required, as M fortuitum has shown low resistance to tigecycline, tetracycline, cefmetazole, imipenem, and aminoglycosides (eg, amikacin, tobramycin, neomycin, gentamycin). Surgery is an important adjunctive tool in treating M fortuitum infections; patients with a single lesion are more likely to undergo surgical treatment alone or in combination with antibiotic therapy.15 More recently, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy has been explored as an alternative to eliminate NTM, including M fortuitum.16

The differential diagnosis for skin lesions manifesting with draining fistulae and sinus tracts includes conditions with infectious (cellulitis and chromomycosis) and inflammatory (pyoderma gangrenosum [PG] and hidradenitis suppurativa [HS]) causes.

Cellulitis is a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that predominantly is caused by gram-positive organisms such as β-hemolytic streptococci.17 Clinical manifestations include acute skin erythema, swelling, tenderness, and warmth. The legs are the most common sites of infection, but any area of the skin can be involved.17 Cellulitis comprises 10% of all infectious disease hospitalizations and up to 11% of all dermatologic admissions.18,19 It frequently is misdiagnosed, perhaps due to the lack of a reliable confirmatory laboratory test or imaging study, in addition to the plethora of diseases that mimic cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, contact dermatitis, lymphedema, eosinophilic cellulitis, and papular urticaria.20,21 The consequences of misdiagnosis include but are not limited to unnecessary hospitalizations, inappropriate antibiotic use, and delayed management of the disease; thus, there is an urgent need for a reliable standard test to confirm the diagnosis, especially among nonspecialist physicians. 20 Most patients with uncomplicated cellulitis can be treated with empiric oral antibiotics that target β-hemolytic streptococci (ie, penicillin V potassium, amoxicillin).17 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus coverage generally is unnecessary for nonpurulent cellulitis, but clinicians can consider adding amoxicillin-clavulanate, dicloxacillin, and cephalexin to the regimen. For purulent cellulitis, incision and drainage should be performed. In severe cases that manifest with sepsis, altered mental status, or hemodynamic instability, inpatient management is required.17

Chromomycosis (also known as chromoblastomycosis) is a chronic, indolent, granulomatous, suppurative mycosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue22 that is caused by traumatic inoculation of various fungi of the order Chaetothyriales and family Herpotrichiellaceae, which are present in soil, plants, and decomposing wood. Chromomycosis is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions.23,24 Clinically, it manifests as oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic lesions around an infection site that can manifest as papules with centrifugal growth evolving into nodular, verrucous, plaque, tumoral, or atrophic forms.22 Diagnosis is made with direct microscopy using potassium hydroxide, which reveals muriform bodies. Fungal culture in Sabouraud agar also can be used to isolate the causative pathogen.22 Unfortunately, chromomycosis is difficult to treat, with low cure rates and high relapse rates. Antifungal agents combined with surgery, cryotherapy, or thermotherapy often are used, with cure rates ranging from 15% to 80%.22,25

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a reactive noninfectious inflammatory dermatosis associated with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. The exact etiology is not clearly understood, but it generally is considered an autoinflammatory disorder.26 The most common form—classical PG—occurs in approximately 85% of cases and manifests as a painful erythematous lesion that progresses to a blistered or necrotic ulcer. It primarily affects the lower legs but can occur in other body sites.27 The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms after excluding other similar conditions; histopathology of biopsied wound tissues often are required for confirmation. Treatment of PG starts with fast-acting immunosuppressive drugs (corticosteroids and/or cyclosporine) followed by slowacting immunosuppressive drugs (biologics).26

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic recurrent disease of the hair follicle unit that develops after puberty.28 Clinically, HS manifests with painful nodules, abscesses, chronically draining fistulas, and scarring in areas of the body rich in apocrine glands.29,30 Treatment of HS is challenging due to its diverse clinical manifestations and unclear etiology. Topical therapy, systemic treatments, biologic agents, surgery, and light therapy have shown variable results.28,31

- Franco-Paredes C, Marcos LA, Henao-Martínez AF, et al. Cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;32: E00069-18. doi:10.1128/CMR.00069-18

- Brown TH. The rapidly growing mycobacteria—MycobacteriuM fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Infect Control. 1985;6:283-238. doi:10.1017/s0195941700061762

- Hooper J; Beltrami EJ; Santoro F; et al. Remember the fite: a case of cutaneous MycobacteriuM fortuitum infection. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:214-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002336

- Franco-Paredes C, Chastain DB, Allen L, et al. Overview of cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:228-232. doi:10.1007/s40475-018-0161-7

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-77. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.017

- Peixoto ADS, Montenegro LML, Lima AS, et al. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria species by multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:E20200211. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0211-2020

- Park J, Kwak N, Chae JC, et al. A two-step real-time PCR method to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and six dominant nontuberculous mycobacterial infections from clinical specimens. Microbiol Spectr. 2023:E0160623. doi:10.1128/spectrum.01606-23

- Fowler J, Mahlen SD. Localized cutaneous infections in immunocompetent individuals due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1106-1109. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0203-RS

- Gardini G, Gregori N, Matteelli A, et al. Mycobacterial skin infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022;35:79-87. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000820

- Wang SH, Pancholi P. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16:438. doi:10.1007/s11908-014-0438-5

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Mougari F, Guglielmetti L, Raskine L, et al. Infections caused by Mycobacterium abscessus: epidemiology, diagnostic tools and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14:1139-1154. doi:10.1080/14787210.201 6.1238304

- Tu HZ, Lee HS, Chen YS, et al. High rates of antimicrobial resistance in rapidly growing mycobacterial infections in Taiwan. Pathogens. 2022;11:969. doi:10.3390/pathogens11090969

- Hashemzadeh M, Zadegan Dezfuli AA, Khosravi AD, et al. F requency of mutations in erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in rrl related to linezolid resistance in clinical isolates of MycobacteriuM fortuitum in Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2023;70:167-176. doi:10.1556/030.2023.02020

- Uslan DZ, Kowalski TJ, Wengenack NL, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria: comparison of clinical features, treatment, and susceptibility. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1287-1292. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1287

- Miretti M, Juri L, Peralta A, et al. Photoinactivation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria using Zn-phthalocyanine loaded into liposomes. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2022;136:102247. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2022.102247

- Bystritsky RJ. Cellulitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:49-60. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2020.10.002

- Christensen K, Holman R, Steiner C, et al. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1025-1035. doi:10.1086/605562

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2020.07.055

- Cutler TS, Jannat-Khah DP, Kam B, et al. Prevalence of misdiagnosis of cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2023;18:254-261. doi:10.1002/jhm.12977

- Keller EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-52. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11121

- Brito AC, Bittencourt MJS. Chromoblastomycosis: an etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:495-506. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187321

- McGinnis MR. Chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: new concepts, diagnosis, and mycology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:1-16.

- Rubin HA, Bruce S, Rosen T, et al. Evidence for percutaneous inoculation as the mode of transmission for chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:951-954.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís V, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Maverakis E, Marzano AV, Le ST, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:81. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0213-x

- George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum—a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:224-228. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-224

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Daxhelet M, Suppa M, White J, et al. Proposed definitions of typical lesions in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2020;236:431-438. doi:10.1159/000507348

- Amat-Samaranch V, Agut-Busquet E, Vilarrasa E, et al. New perspectives on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211055920. doi:10.1177/20406223211055920

- Franco-Paredes C, Marcos LA, Henao-Martínez AF, et al. Cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;32: E00069-18. doi:10.1128/CMR.00069-18

- Brown TH. The rapidly growing mycobacteria—MycobacteriuM fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Infect Control. 1985;6:283-238. doi:10.1017/s0195941700061762

- Hooper J; Beltrami EJ; Santoro F; et al. Remember the fite: a case of cutaneous MycobacteriuM fortuitum infection. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:214-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002336

- Franco-Paredes C, Chastain DB, Allen L, et al. Overview of cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:228-232. doi:10.1007/s40475-018-0161-7

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-77. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.017

- Peixoto ADS, Montenegro LML, Lima AS, et al. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria species by multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:E20200211. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0211-2020

- Park J, Kwak N, Chae JC, et al. A two-step real-time PCR method to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and six dominant nontuberculous mycobacterial infections from clinical specimens. Microbiol Spectr. 2023:E0160623. doi:10.1128/spectrum.01606-23

- Fowler J, Mahlen SD. Localized cutaneous infections in immunocompetent individuals due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1106-1109. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0203-RS

- Gardini G, Gregori N, Matteelli A, et al. Mycobacterial skin infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022;35:79-87. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000820

- Wang SH, Pancholi P. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16:438. doi:10.1007/s11908-014-0438-5

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Mougari F, Guglielmetti L, Raskine L, et al. Infections caused by Mycobacterium abscessus: epidemiology, diagnostic tools and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14:1139-1154. doi:10.1080/14787210.201 6.1238304

- Tu HZ, Lee HS, Chen YS, et al. High rates of antimicrobial resistance in rapidly growing mycobacterial infections in Taiwan. Pathogens. 2022;11:969. doi:10.3390/pathogens11090969

- Hashemzadeh M, Zadegan Dezfuli AA, Khosravi AD, et al. F requency of mutations in erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in rrl related to linezolid resistance in clinical isolates of MycobacteriuM fortuitum in Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2023;70:167-176. doi:10.1556/030.2023.02020

- Uslan DZ, Kowalski TJ, Wengenack NL, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria: comparison of clinical features, treatment, and susceptibility. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1287-1292. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1287

- Miretti M, Juri L, Peralta A, et al. Photoinactivation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria using Zn-phthalocyanine loaded into liposomes. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2022;136:102247. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2022.102247

- Bystritsky RJ. Cellulitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:49-60. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2020.10.002

- Christensen K, Holman R, Steiner C, et al. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1025-1035. doi:10.1086/605562

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2020.07.055

- Cutler TS, Jannat-Khah DP, Kam B, et al. Prevalence of misdiagnosis of cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2023;18:254-261. doi:10.1002/jhm.12977

- Keller EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-52. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11121

- Brito AC, Bittencourt MJS. Chromoblastomycosis: an etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:495-506. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187321

- McGinnis MR. Chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: new concepts, diagnosis, and mycology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:1-16.

- Rubin HA, Bruce S, Rosen T, et al. Evidence for percutaneous inoculation as the mode of transmission for chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:951-954.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís V, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Maverakis E, Marzano AV, Le ST, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:81. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0213-x

- George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum—a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:224-228. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-224

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Daxhelet M, Suppa M, White J, et al. Proposed definitions of typical lesions in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2020;236:431-438. doi:10.1159/000507348

- Amat-Samaranch V, Agut-Busquet E, Vilarrasa E, et al. New perspectives on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211055920. doi:10.1177/20406223211055920

A 40-year-old woman presented with multiple draining sinus tracts on the right thigh following an injury sustained weeks earlier while mowing wet grass.

Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia: Diagnostic Criteria, Treatment, and COVID-19

- Torres A, Cilloniz C, Niederman MS, et al. Pneumonia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):25. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00259-0

- Niederman MS, Torres A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(166):220123. doi:10.1183/16000617.0123-2022

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67. doi:10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST

- Memon RA, Rashid MA, Avva S, et al. The use of the SMART-COP score in predicting severity outcomes among patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e27248. doi:10.7759/cureus.27248

- Regunath H, Oba Y. Community-acquired pneumonia. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated January 26, 2024. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430749/

- Dequin PF, Meziani F, Quenot JP, et al; for the CRICS-TriGGERSep Network. Hydrocortisone in severe community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(21):1931-1941. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2215145

- Eizaguirre S, Sabater G, Belda S, et al. Long-term respiratory consequences of COVID-19 related pneumonia: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):439. doi:10.1186/s12890-023-02627-w

- Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al; for the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study Group. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1806-1812. doi:10.1093/cid/cix647

- Morgan AJ, Glossop AJ. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. BJA Educ. 2016;16(5):167-172. doi:10.1093/bjaed/mkv052

- Haessler S, Guo N, Deshpande A, et al. Etiology, treatments, and outcomes of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia in a large U.S. sample. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(7):1063-1071. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000005498

- Nolley EP, Sahetya SK, Hochberg CH, et al. Outcomes among mechanically ventilated patients with severe pneumonia and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure from SARS-CoV-2 and other etiologies. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2250401. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.50401

- Hino T, Nishino M, Valtchinov VI, et al. Severe COVID-19 pneumonia leads to post-COVID-19 lung abnormalities on follow-up CT scans. Eur J Radiol Open. 2023;10:100483. doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2023.100483

- Torres A, Cilloniz C, Niederman MS, et al. Pneumonia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):25. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00259-0

- Niederman MS, Torres A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(166):220123. doi:10.1183/16000617.0123-2022

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67. doi:10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST

- Memon RA, Rashid MA, Avva S, et al. The use of the SMART-COP score in predicting severity outcomes among patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e27248. doi:10.7759/cureus.27248

- Regunath H, Oba Y. Community-acquired pneumonia. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated January 26, 2024. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430749/

- Dequin PF, Meziani F, Quenot JP, et al; for the CRICS-TriGGERSep Network. Hydrocortisone in severe community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(21):1931-1941. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2215145

- Eizaguirre S, Sabater G, Belda S, et al. Long-term respiratory consequences of COVID-19 related pneumonia: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):439. doi:10.1186/s12890-023-02627-w

- Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al; for the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study Group. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1806-1812. doi:10.1093/cid/cix647

- Morgan AJ, Glossop AJ. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. BJA Educ. 2016;16(5):167-172. doi:10.1093/bjaed/mkv052

- Haessler S, Guo N, Deshpande A, et al. Etiology, treatments, and outcomes of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia in a large U.S. sample. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(7):1063-1071. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000005498

- Nolley EP, Sahetya SK, Hochberg CH, et al. Outcomes among mechanically ventilated patients with severe pneumonia and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure from SARS-CoV-2 and other etiologies. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2250401. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.50401

- Hino T, Nishino M, Valtchinov VI, et al. Severe COVID-19 pneumonia leads to post-COVID-19 lung abnormalities on follow-up CT scans. Eur J Radiol Open. 2023;10:100483. doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2023.100483

- Torres A, Cilloniz C, Niederman MS, et al. Pneumonia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):25. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00259-0

- Niederman MS, Torres A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(166):220123. doi:10.1183/16000617.0123-2022

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45-e67. doi:10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST

- Memon RA, Rashid MA, Avva S, et al. The use of the SMART-COP score in predicting severity outcomes among patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e27248. doi:10.7759/cureus.27248

- Regunath H, Oba Y. Community-acquired pneumonia. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated January 26, 2024. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430749/

- Dequin PF, Meziani F, Quenot JP, et al; for the CRICS-TriGGERSep Network. Hydrocortisone in severe community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(21):1931-1941. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2215145

- Eizaguirre S, Sabater G, Belda S, et al. Long-term respiratory consequences of COVID-19 related pneumonia: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23(1):439. doi:10.1186/s12890-023-02627-w

- Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al; for the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study Group. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1806-1812. doi:10.1093/cid/cix647

- Morgan AJ, Glossop AJ. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. BJA Educ. 2016;16(5):167-172. doi:10.1093/bjaed/mkv052

- Haessler S, Guo N, Deshpande A, et al. Etiology, treatments, and outcomes of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia in a large U.S. sample. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(7):1063-1071. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000005498

- Nolley EP, Sahetya SK, Hochberg CH, et al. Outcomes among mechanically ventilated patients with severe pneumonia and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure from SARS-CoV-2 and other etiologies. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2250401. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.50401

- Hino T, Nishino M, Valtchinov VI, et al. Severe COVID-19 pneumonia leads to post-COVID-19 lung abnormalities on follow-up CT scans. Eur J Radiol Open. 2023;10:100483. doi:10.1016/j.ejro.2023.100483

Acute Tender Papules on the Arms and Legs

The Diagnosis: Erythema Nodosum Leprosum

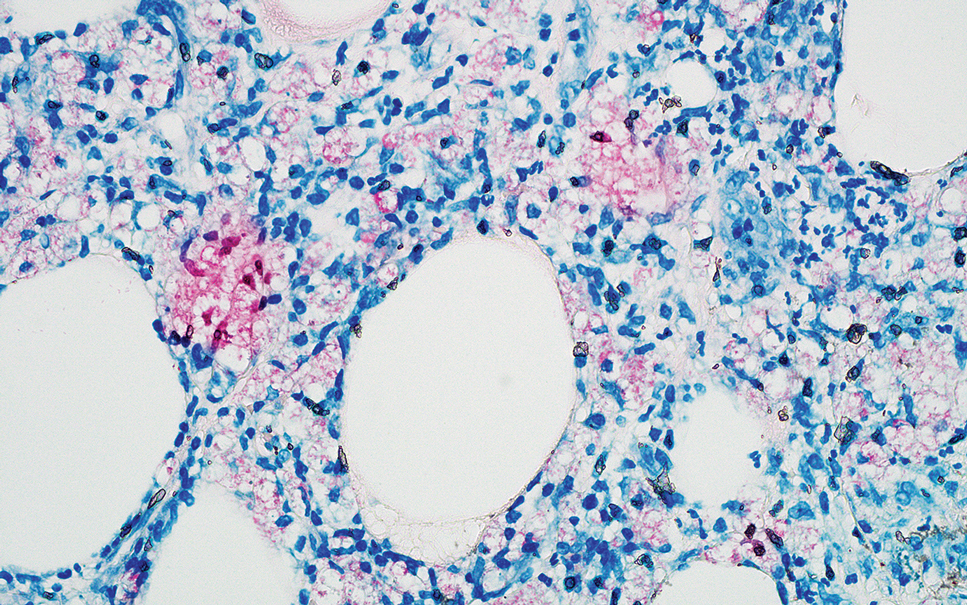

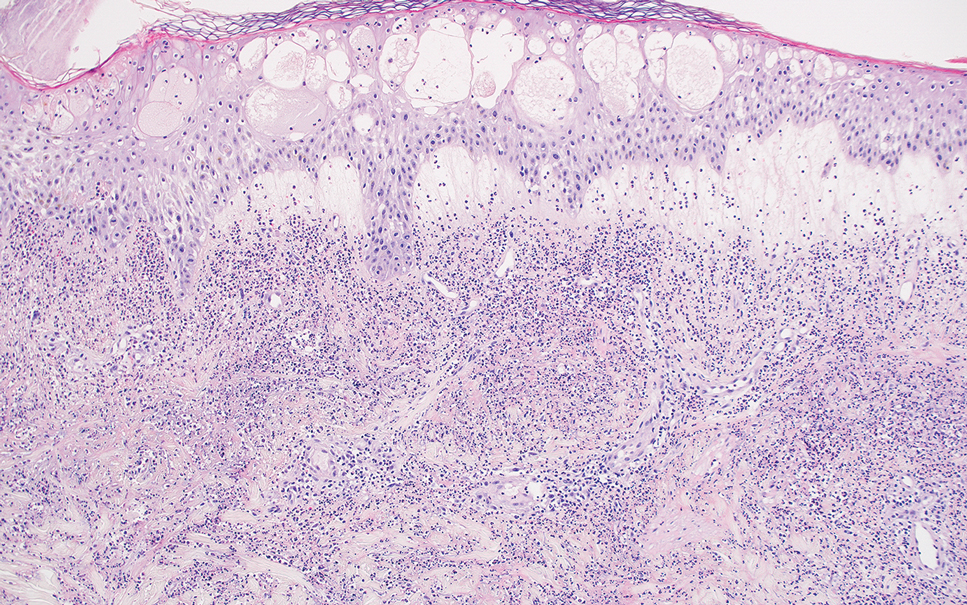

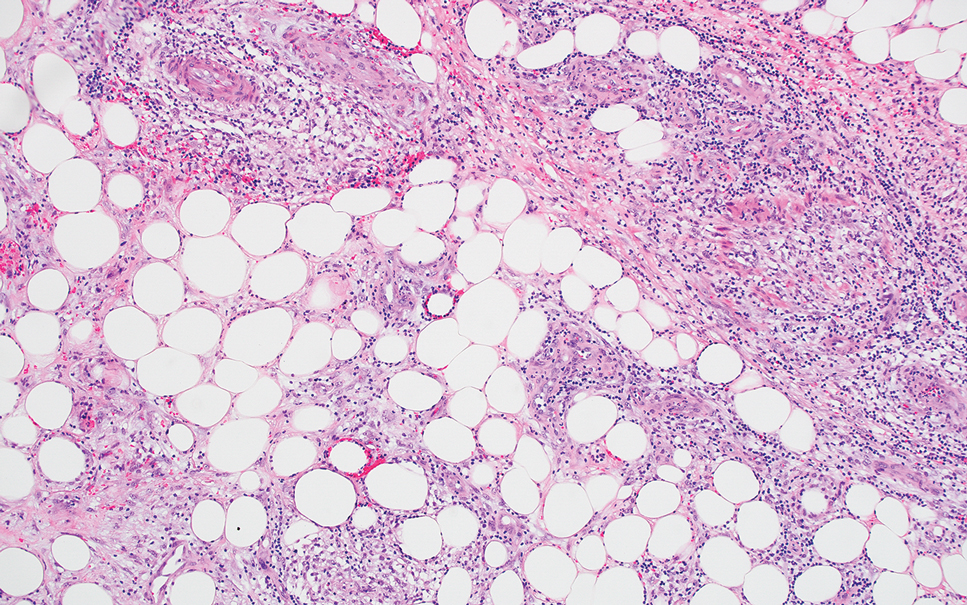

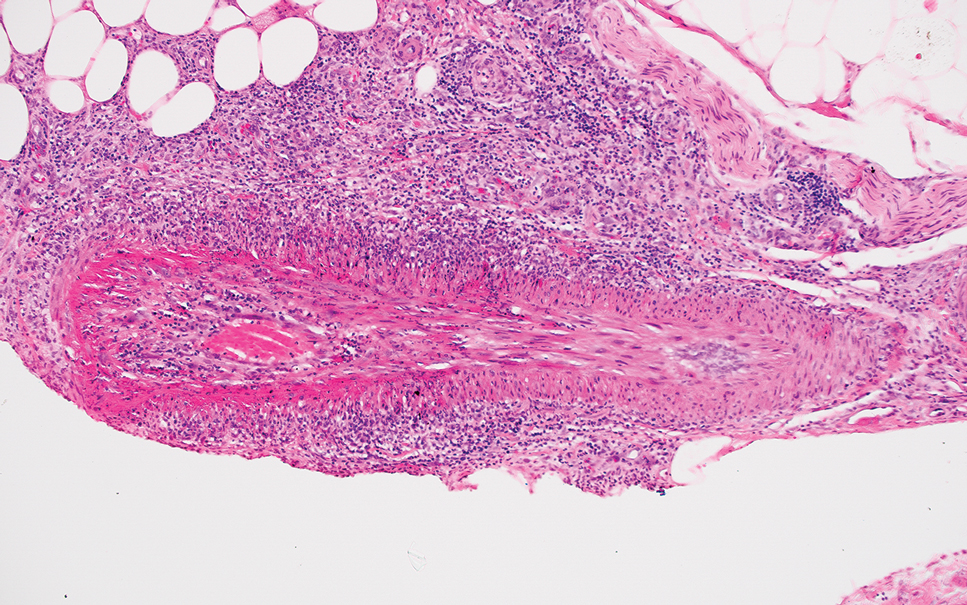

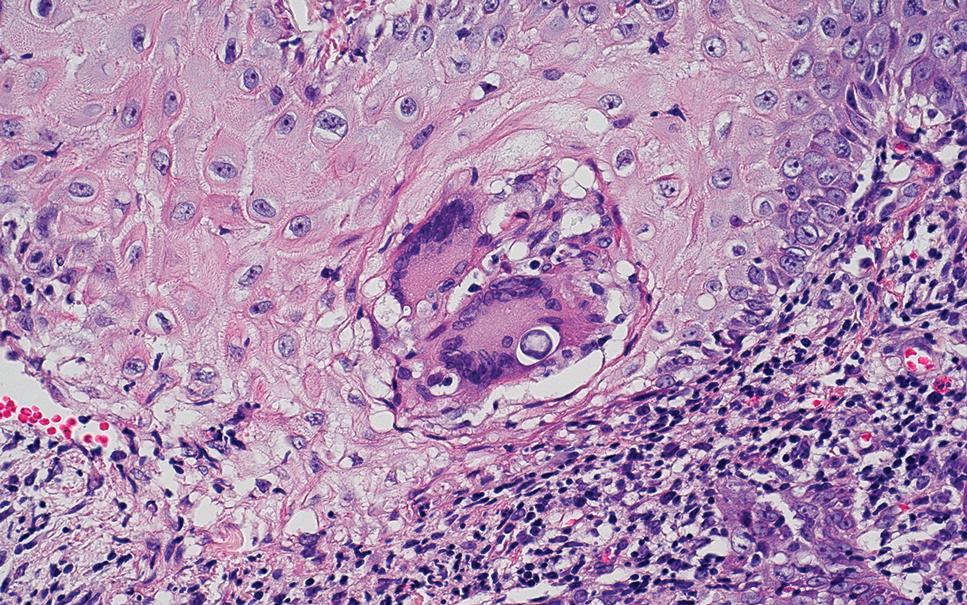

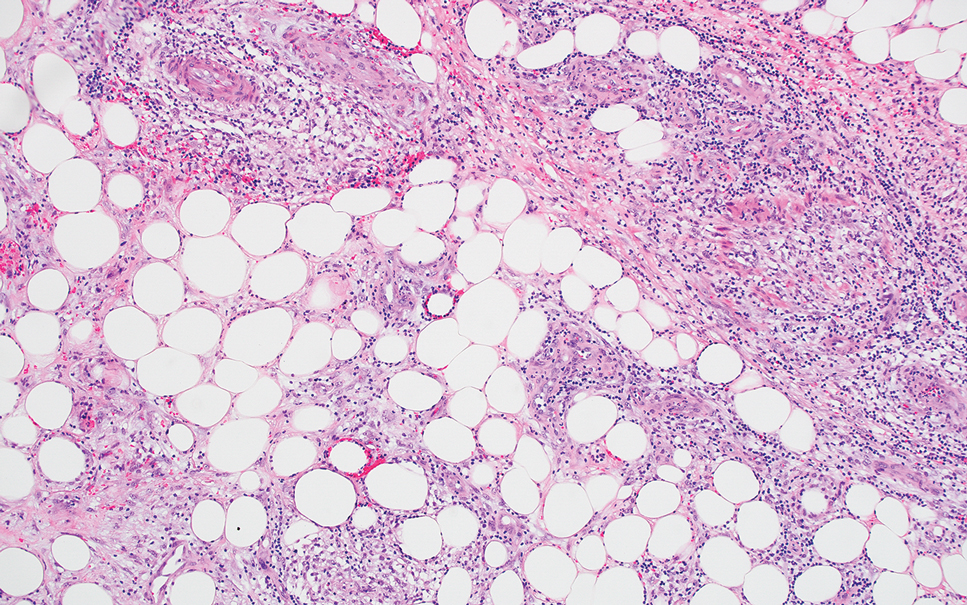

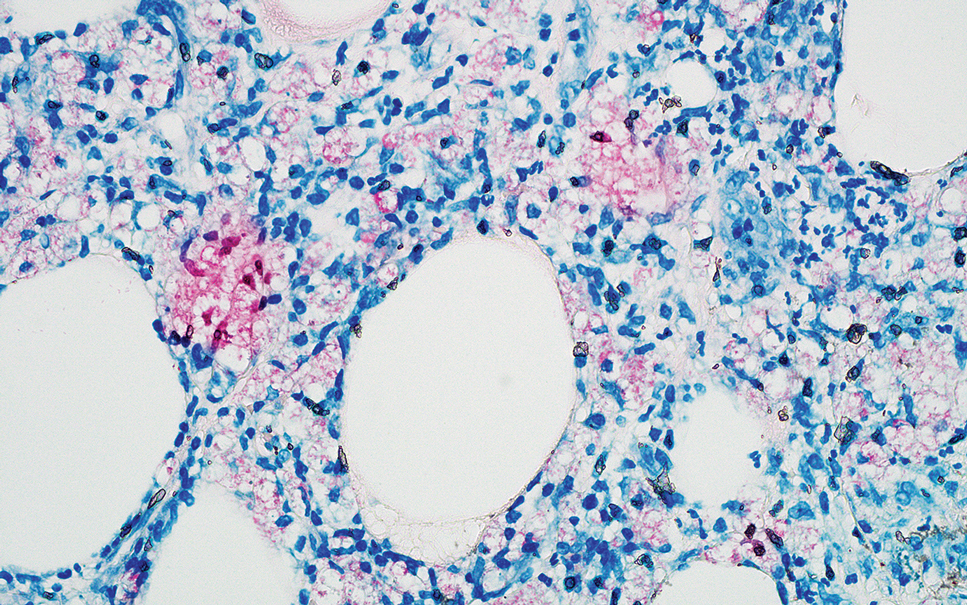

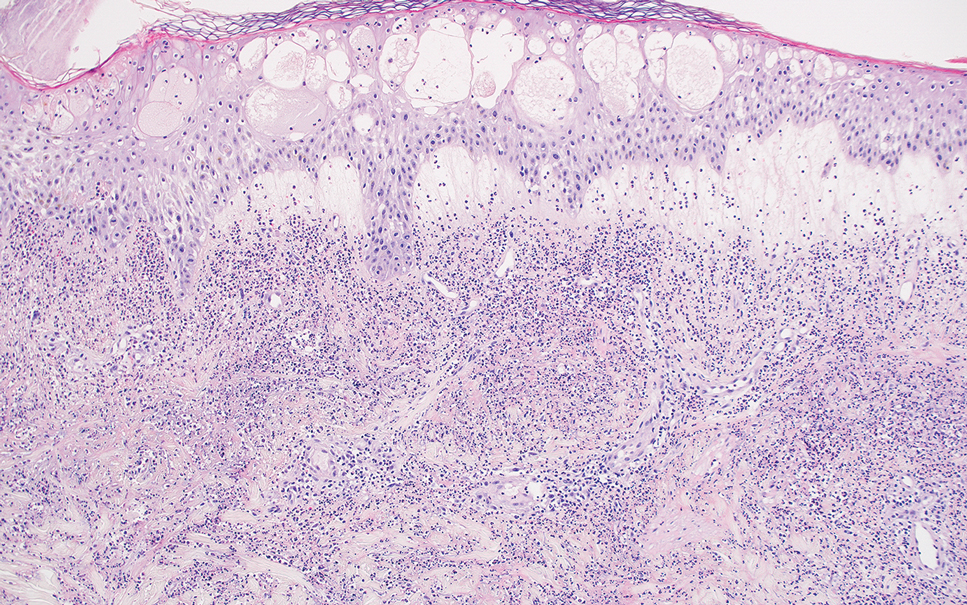

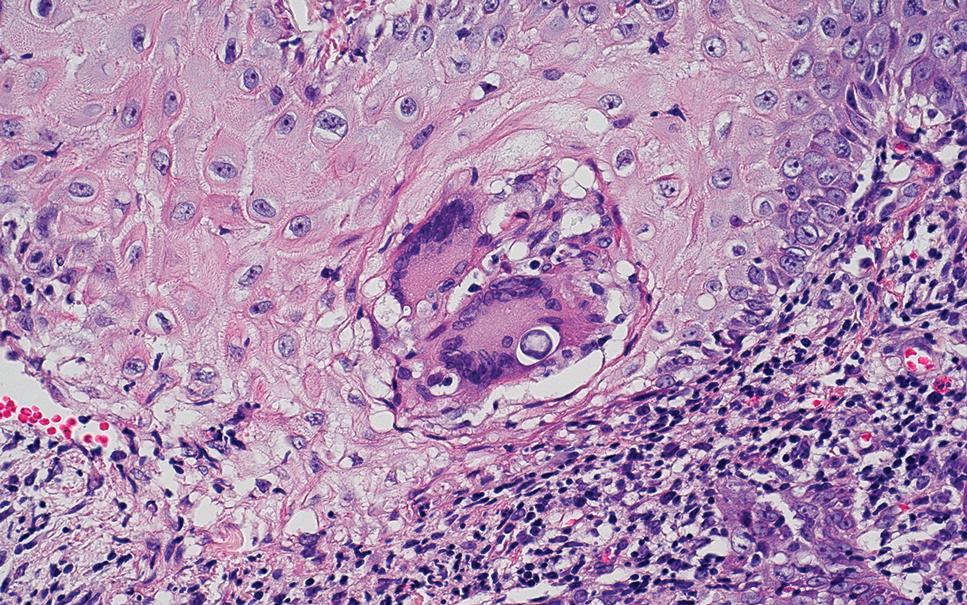

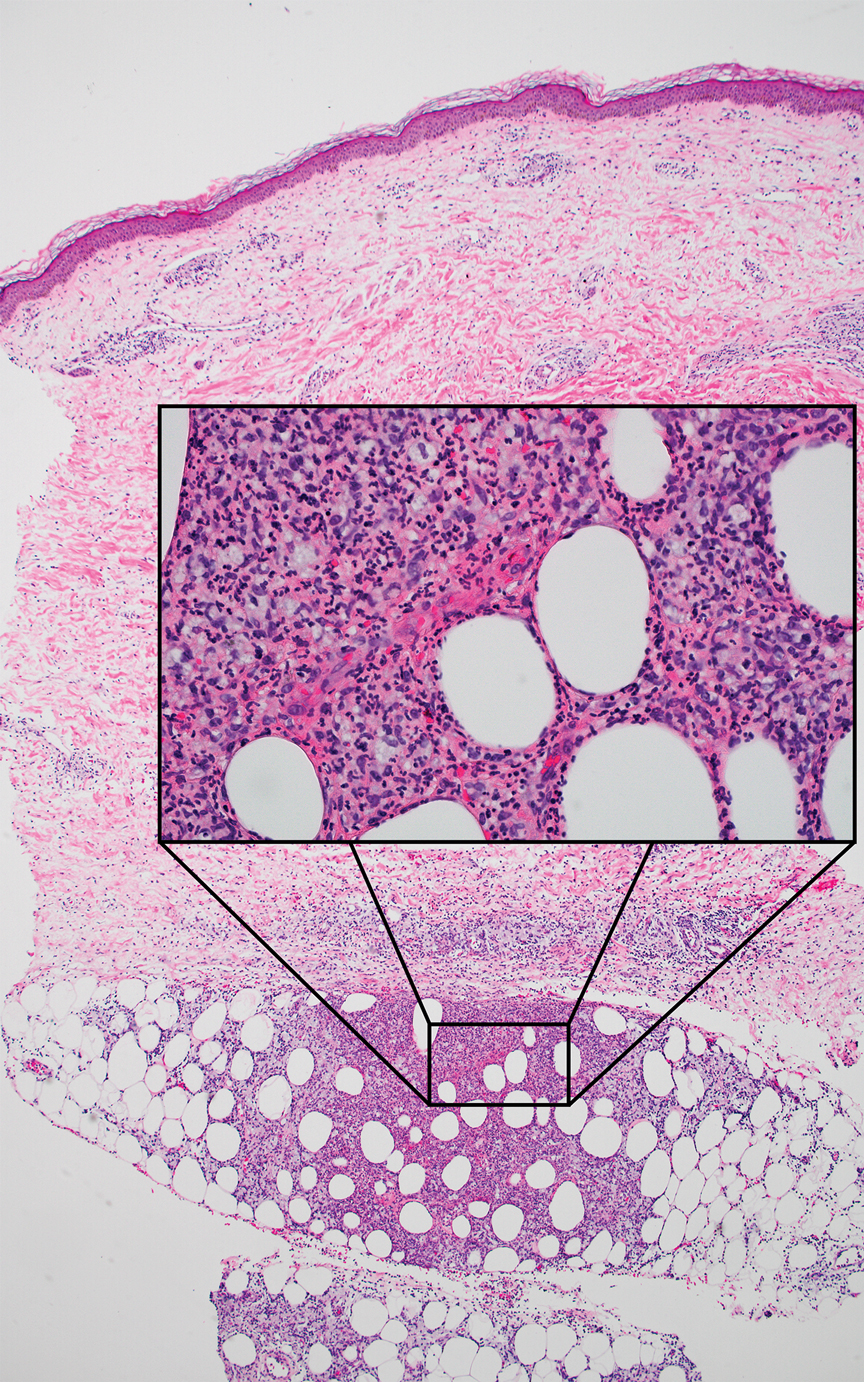

Erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) is a type 2 reaction sometimes seen in patients infected with Mycobacterium leprae—primarily those with lepromatous or borderline lepromatous subtypes. Clinically, ENL manifests with abrupt onset of tender erythematous papules with associated fevers and general malaise. Studies have demonstrated a complex immune system reaction in ENL, but the detailed pathophysiology is not fully understood.1 Biopsies conducted within 24 hours of lesion formation are most elucidating. Foamy histiocytes admixed with neutrophils are seen in the subcutis, often causing a lobular panniculitis (quiz image).2 Neutrophils rarely are seen in other types of leprosy and thus are a useful diagnostic clue for ENL. Vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels can be seen but is not a necessary diagnostic criterion. Fite staining will highlight many acid-fast bacilli within the histiocytes (Figure 1).

Erythema nodosum leprosum is treated with a combination of immunosuppressants such as prednisone and thalidomide. Our patient was taking triple-antibiotic therapy—dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine—for lepromatous leprosy when the erythematous papules developed on the arms and legs. After a skin biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of ENL, he was started on prednisone 20 mg daily with plans for close follow-up. Unfortunately, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

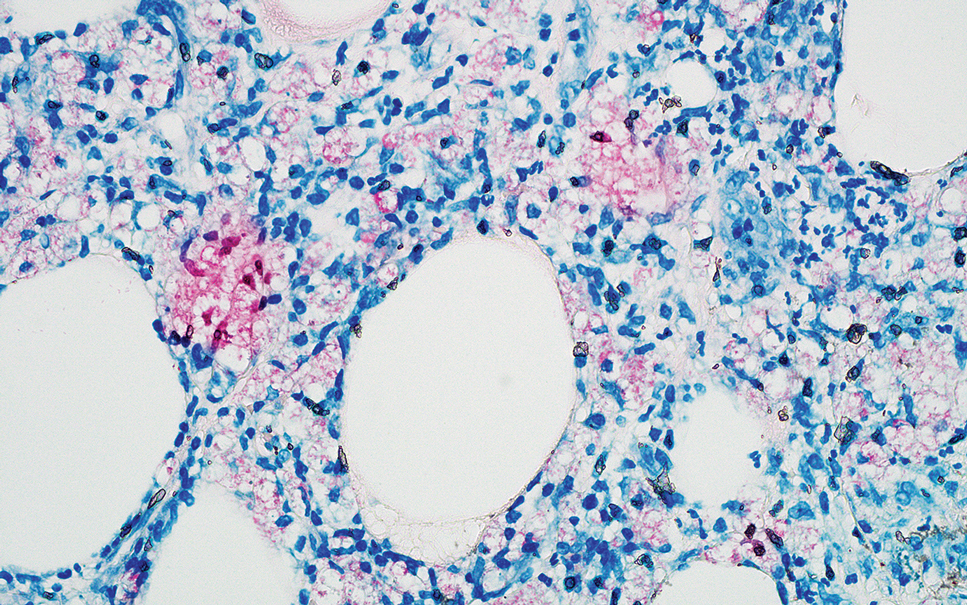

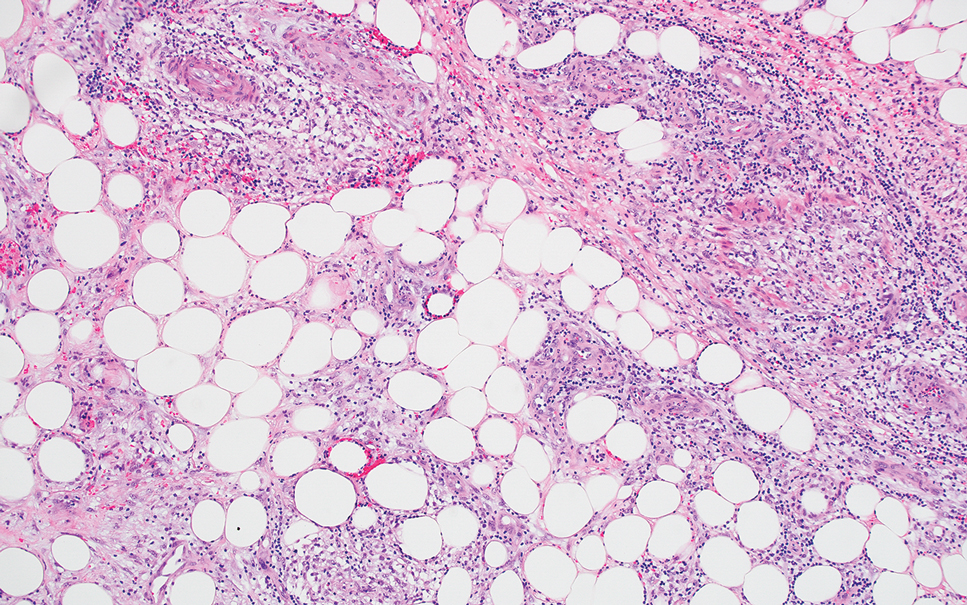

Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (also known as Sweet syndrome) is an acute inflammatory disease characterized by abrupt onset of painful erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules on the skin. It often is seen in association with preceding infections (especially those in the upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tracts), hematologic malignancies, inflammatory bowel disease, or exposure to certain classes of medications (eg, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, various antibiotics).3 Histologically, acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis is characterized by dense neutrophilic infiltrates, often with notable dermal edema (Figure 2).4 Many cases also show leukocytoclastic vasculitis; however, foamy histiocytes are not a notable component of the inflammatory infiltrate, though a histiocytoid form of acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis has been described.5 Infections must be rigorously ruled out prior to diagnosing a patient with acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, making it a diagnosis of exclusion.

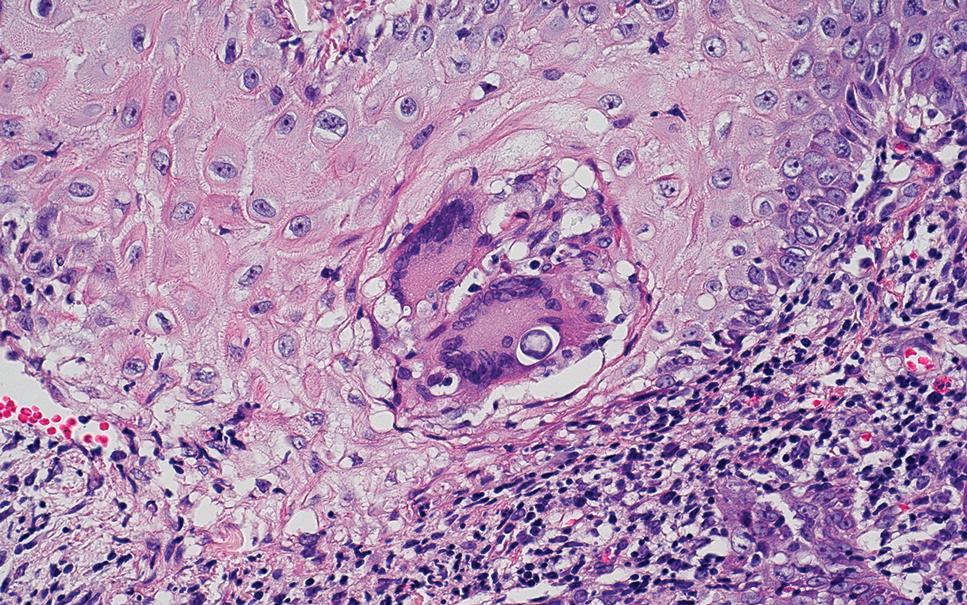

Cutaneous coccidioidomycosis is an infection caused by the dimorphic fungi Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii. Cutaneous disease is rare but can occur from direct inoculation or dissemination from pulmonary disease in immunocompetent or immunocompromised patients. Papules, pustules, or plaques are seen clinically. Histologically, cutaneous coccidioidomycosis shows spherules that vary from 10 to 100 μm and are filled with multiple smaller endospores (Figure 3).6 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with dense suppurative and granulomatous infiltrates also is seen.

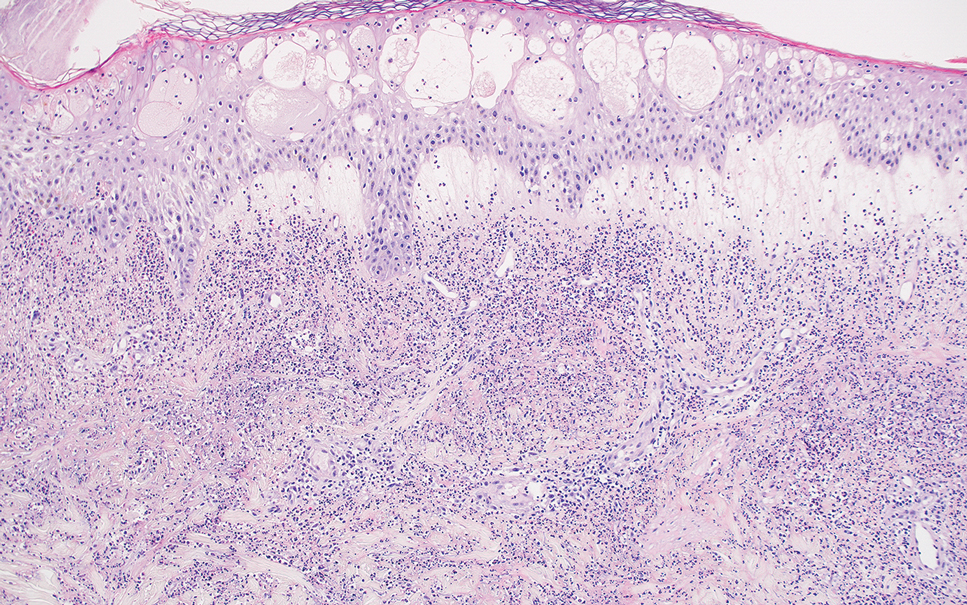

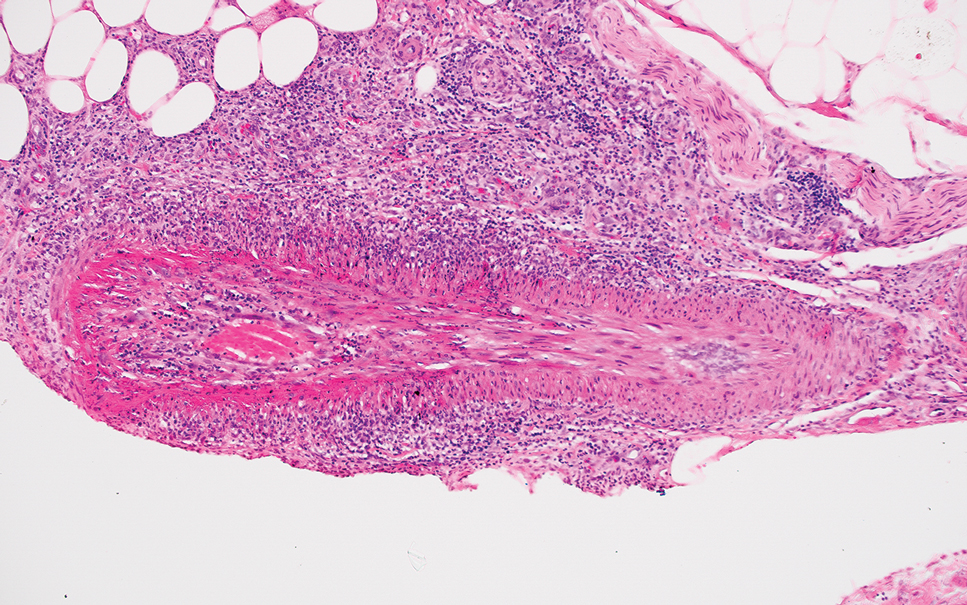

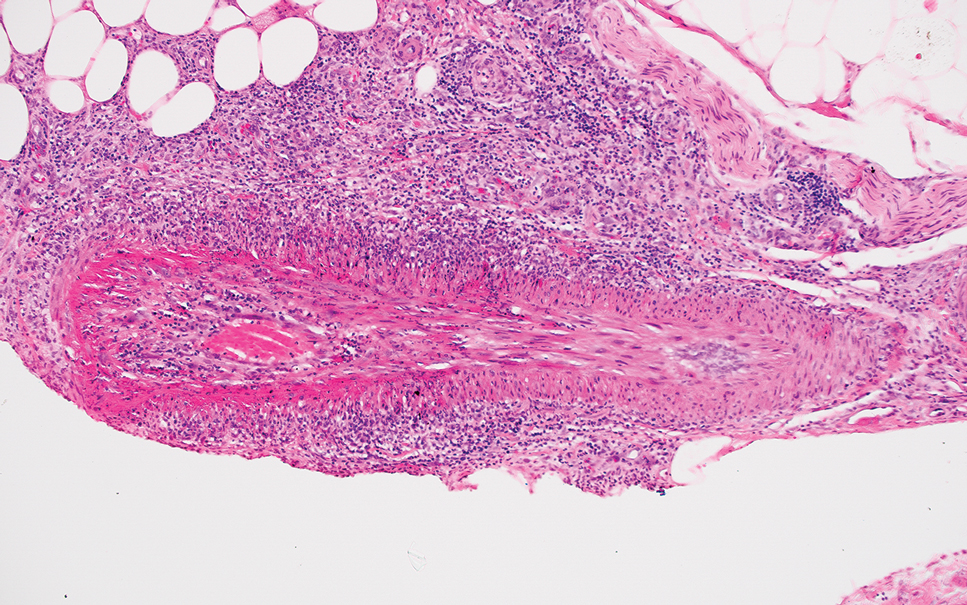

Erythema induratum is characterized by tender nodules on the lower extremities and has a substantial female predominance. Many cases are associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. The bacteria are not seen directly in the skin but are instead detectable through DNA polymerase chain reaction testing or investigation of other organ systems.7,8 Histologically, lesions show a lobular panniculitis with a mixed infiltrate. Vasculitis is seen in approximately 90% of erythema induratum cases vs approximately 25% of classic ENL cases (Figure 4),2,9 which has led some to use the term nodular vasculitis to describe this disease entity. Nodular vasculitis is considered by others to be a distinct disease entity in which there are clinical and histologic features similar to erythema induratum but no evidence of M tuberculosis infection.9

Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis that affects medium- sized vessels of various organ systems. The presenting signs and symptoms vary based on the affected organ systems. Palpable to retiform purpura, livedo racemosa, subcutaneous nodules, or ulcers are seen when the skin is involved. The histologic hallmark is necrotizing vasculitis of medium-sized arterioles (Figure 5), although leukocytoclastic vasculitis of small-caliber vessels also can be seen in biopsies of affected skin.10 The vascular changes are said to be segmental, with uninvolved segments interspersed with involved segments. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)– associated vasculitis also must be considered when one sees leukocytoclastic vasculitis of small-caliber vessels in the skin, as it can be distinguished most readily by detecting circulating antibodies specific for myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA) or proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA).

- Polycarpou A, Walker SL, Lockwood DNJ. A systematic review of immunological studies of erythema nodosum leprosum. Front Immunol. 2017;8:233. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00233

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.10.003

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:1-28. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-34

- Ratzinger G, Burgdorf W, Zelger BG, et al. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathologic study of 31 cases with review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:125-133. doi:10.1097/01.dad.0000249887.59810.76

- Wilson TC, Stone MS, Swick BL. Histiocytoid Sweet syndrome with haloed myeloid cells masquerading as a cryptococcal infection. Am J Dermatopathology. 2014;36:264-269. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31828b811b

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280. doi:10.1128/CMR.00053-10

- Schneider JW, Jordaan HF, Geiger DH, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin: a clinicopathological study of 20 cases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in skin lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:350-356. doi:10.1097/00000372-199508000-00008

- Boonchai W, Suthipinittharm P, Mahaisavariya P. Panniculitis in tuberculosis: a clinicopathologic study of nodular panniculitis associated with tuberculosis. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:361-363. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00299.x

- Segura S, Pujol RM, Trindade F, et al. Vasculitis in erythema induratum of Bazin: a histopathologic study of 101 biopsy specimens from 86 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:839-851. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.030

- Ishiguro N, Kawashima M. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: a report of 16 cases with clinical and histopathological analysis and a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2010;37:85-93. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00752.x

The Diagnosis: Erythema Nodosum Leprosum

Erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) is a type 2 reaction sometimes seen in patients infected with Mycobacterium leprae—primarily those with lepromatous or borderline lepromatous subtypes. Clinically, ENL manifests with abrupt onset of tender erythematous papules with associated fevers and general malaise. Studies have demonstrated a complex immune system reaction in ENL, but the detailed pathophysiology is not fully understood.1 Biopsies conducted within 24 hours of lesion formation are most elucidating. Foamy histiocytes admixed with neutrophils are seen in the subcutis, often causing a lobular panniculitis (quiz image).2 Neutrophils rarely are seen in other types of leprosy and thus are a useful diagnostic clue for ENL. Vasculitis of small- to medium-sized vessels can be seen but is not a necessary diagnostic criterion. Fite staining will highlight many acid-fast bacilli within the histiocytes (Figure 1).

Erythema nodosum leprosum is treated with a combination of immunosuppressants such as prednisone and thalidomide. Our patient was taking triple-antibiotic therapy—dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine—for lepromatous leprosy when the erythematous papules developed on the arms and legs. After a skin biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of ENL, he was started on prednisone 20 mg daily with plans for close follow-up. Unfortunately, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.