User login

Nebulized amphotericin B does not affect aspergillosis exacerbation-free status at 1 year

Topline

Nebulized amphotericin B does not improve exacerbation-free status at 1 year for patients with bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, though it may delay onset and incidence.

Methodology

Investigators searched PubMed and Embase databases for studies that included at least five patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis who were managed with nebulized amphotericin B.

They included five studies, two of which were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and three were observational studies; there was a total of 188 patients.

The primary objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the frequency of patients remaining exacerbation free 1 year after initiating treatment with nebulized amphotericin B.

Takeaway

From the studies (one observational, two RCTs; n = 84) with exacerbation data at 1 or 2 years, the pooled proportion of patients who remained exacerbation free with nebulized amphotericin B at 1 year was 76% (I2 = 64.6%).

The pooled difference in risk with the two RCTs that assessed exacerbation-free status at 1 year was 0.33 and was not significantly different between the nebulized amphotericin B and control arms, which received nebulized saline.

Two RCTs provided the time to first exacerbation, which was significantly longer with nebulized amphotericin B than with nebulized saline (337 vs. 177 days; P = .004; I2 = 82%).

The proportion of patients who experienced two or more exacerbations was significantly lower with nebulized amphotericin B than with nebulized saline (9/33 [27.3%] vs 20/38 [52.6%]; P = .03).

In practice

Also, the proportion of subjects experiencing ≥ 2 exacerbations was also lesser with NAB than in the control,” concluded Valliappan Muthu, MD, and colleagues. However, “the ideal duration and optimal dose of LAMB for nebulization are unclear.”

Study details

“Nebulized amphotericin B for preventing exacerbations in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis” was published online in Pulmonary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

Limitations

The current review is limited by the small number of included trials and may have a high risk of bias. Therefore, more evidence is required for the use of nebulized amphotericin B in routine care. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Topline

Nebulized amphotericin B does not improve exacerbation-free status at 1 year for patients with bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, though it may delay onset and incidence.

Methodology

Investigators searched PubMed and Embase databases for studies that included at least five patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis who were managed with nebulized amphotericin B.

They included five studies, two of which were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and three were observational studies; there was a total of 188 patients.

The primary objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the frequency of patients remaining exacerbation free 1 year after initiating treatment with nebulized amphotericin B.

Takeaway

From the studies (one observational, two RCTs; n = 84) with exacerbation data at 1 or 2 years, the pooled proportion of patients who remained exacerbation free with nebulized amphotericin B at 1 year was 76% (I2 = 64.6%).

The pooled difference in risk with the two RCTs that assessed exacerbation-free status at 1 year was 0.33 and was not significantly different between the nebulized amphotericin B and control arms, which received nebulized saline.

Two RCTs provided the time to first exacerbation, which was significantly longer with nebulized amphotericin B than with nebulized saline (337 vs. 177 days; P = .004; I2 = 82%).

The proportion of patients who experienced two or more exacerbations was significantly lower with nebulized amphotericin B than with nebulized saline (9/33 [27.3%] vs 20/38 [52.6%]; P = .03).

In practice

Also, the proportion of subjects experiencing ≥ 2 exacerbations was also lesser with NAB than in the control,” concluded Valliappan Muthu, MD, and colleagues. However, “the ideal duration and optimal dose of LAMB for nebulization are unclear.”

Study details

“Nebulized amphotericin B for preventing exacerbations in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis” was published online in Pulmonary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

Limitations

The current review is limited by the small number of included trials and may have a high risk of bias. Therefore, more evidence is required for the use of nebulized amphotericin B in routine care. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Topline

Nebulized amphotericin B does not improve exacerbation-free status at 1 year for patients with bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, though it may delay onset and incidence.

Methodology

Investigators searched PubMed and Embase databases for studies that included at least five patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis who were managed with nebulized amphotericin B.

They included five studies, two of which were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and three were observational studies; there was a total of 188 patients.

The primary objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the frequency of patients remaining exacerbation free 1 year after initiating treatment with nebulized amphotericin B.

Takeaway

From the studies (one observational, two RCTs; n = 84) with exacerbation data at 1 or 2 years, the pooled proportion of patients who remained exacerbation free with nebulized amphotericin B at 1 year was 76% (I2 = 64.6%).

The pooled difference in risk with the two RCTs that assessed exacerbation-free status at 1 year was 0.33 and was not significantly different between the nebulized amphotericin B and control arms, which received nebulized saline.

Two RCTs provided the time to first exacerbation, which was significantly longer with nebulized amphotericin B than with nebulized saline (337 vs. 177 days; P = .004; I2 = 82%).

The proportion of patients who experienced two or more exacerbations was significantly lower with nebulized amphotericin B than with nebulized saline (9/33 [27.3%] vs 20/38 [52.6%]; P = .03).

In practice

Also, the proportion of subjects experiencing ≥ 2 exacerbations was also lesser with NAB than in the control,” concluded Valliappan Muthu, MD, and colleagues. However, “the ideal duration and optimal dose of LAMB for nebulization are unclear.”

Study details

“Nebulized amphotericin B for preventing exacerbations in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis” was published online in Pulmonary Pharmacology and Therapeutics.

Limitations

The current review is limited by the small number of included trials and may have a high risk of bias. Therefore, more evidence is required for the use of nebulized amphotericin B in routine care. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Palliative Care: Utilization Patterns in Inpatient Dermatology

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

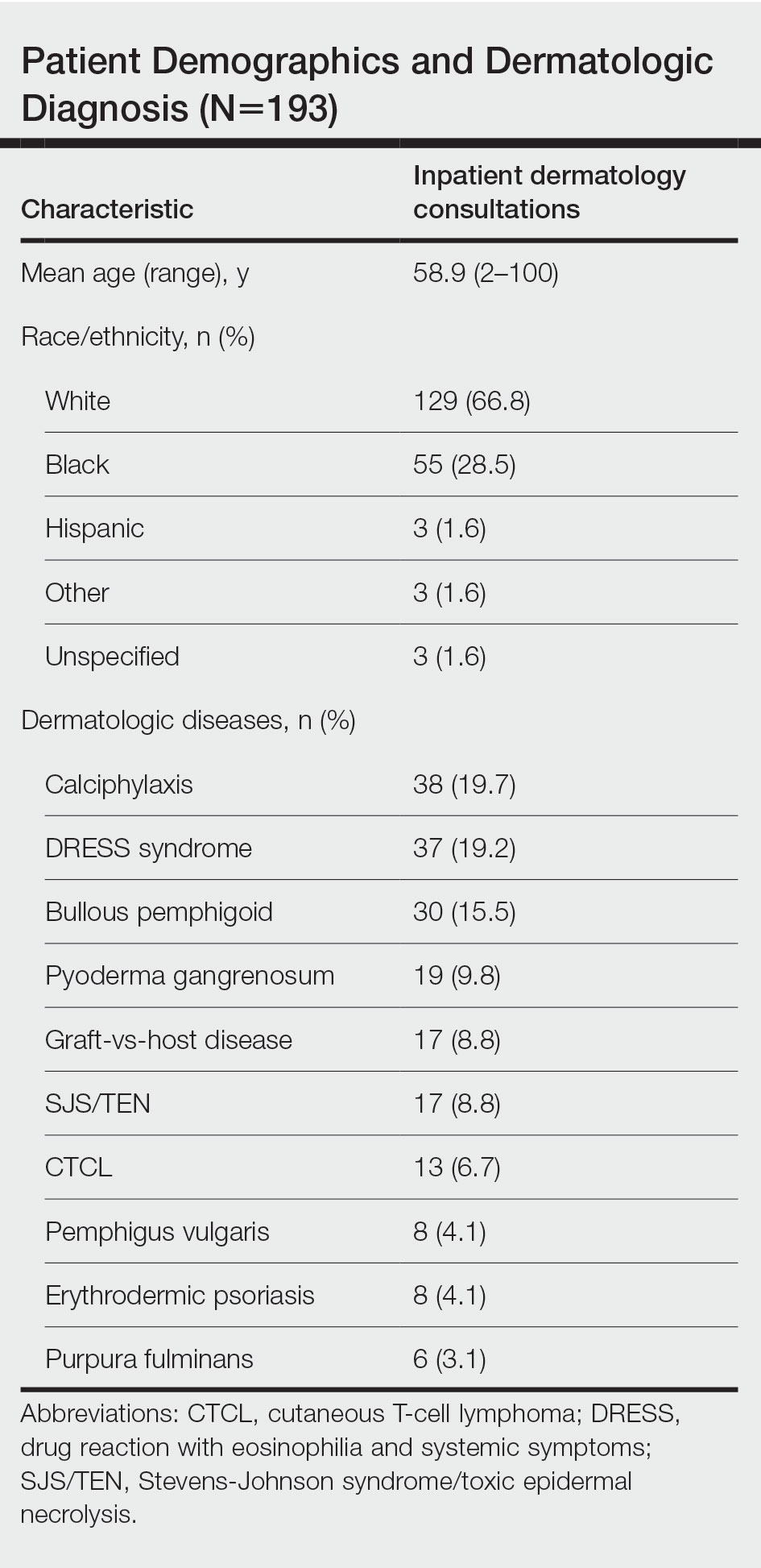

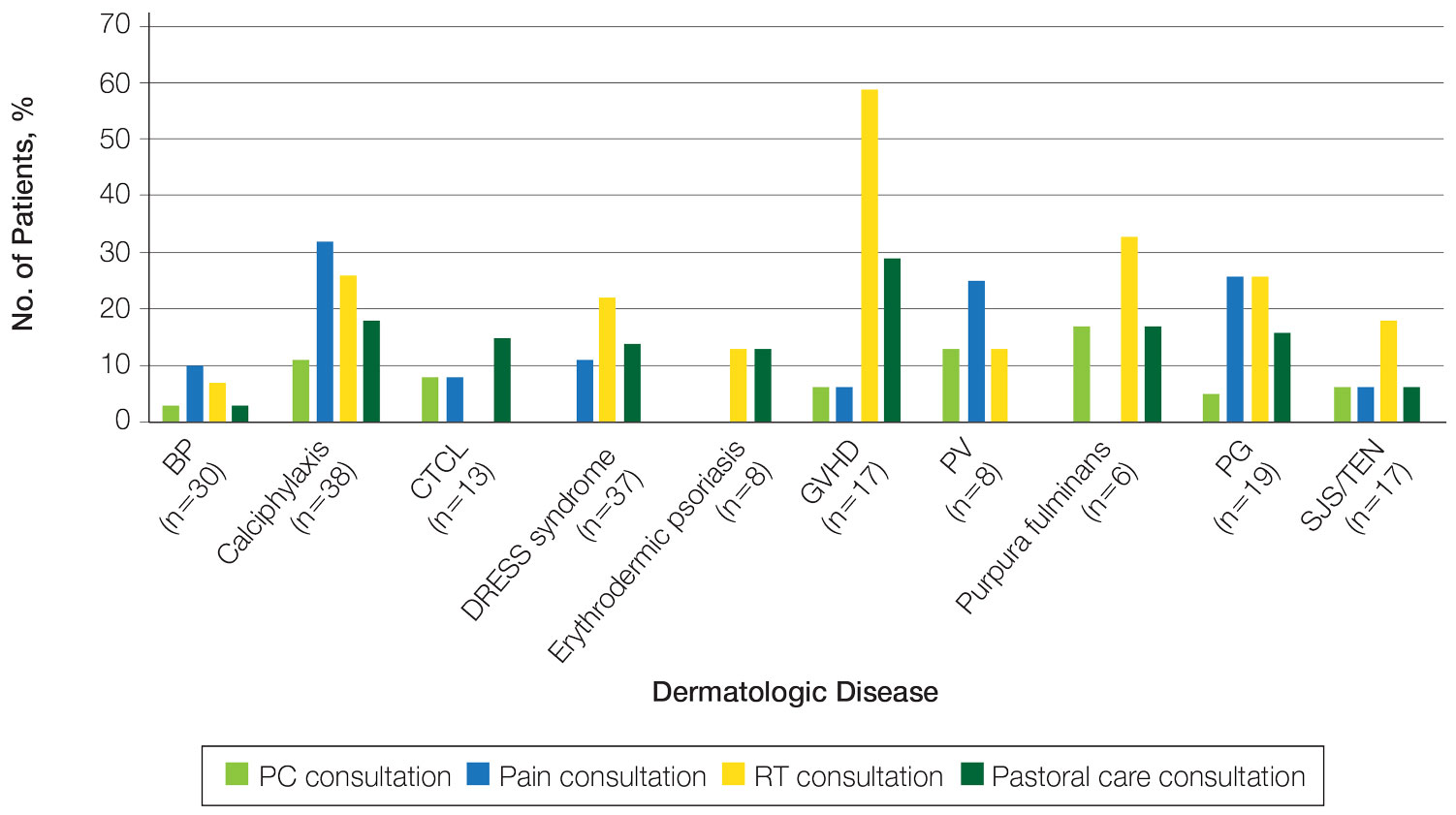

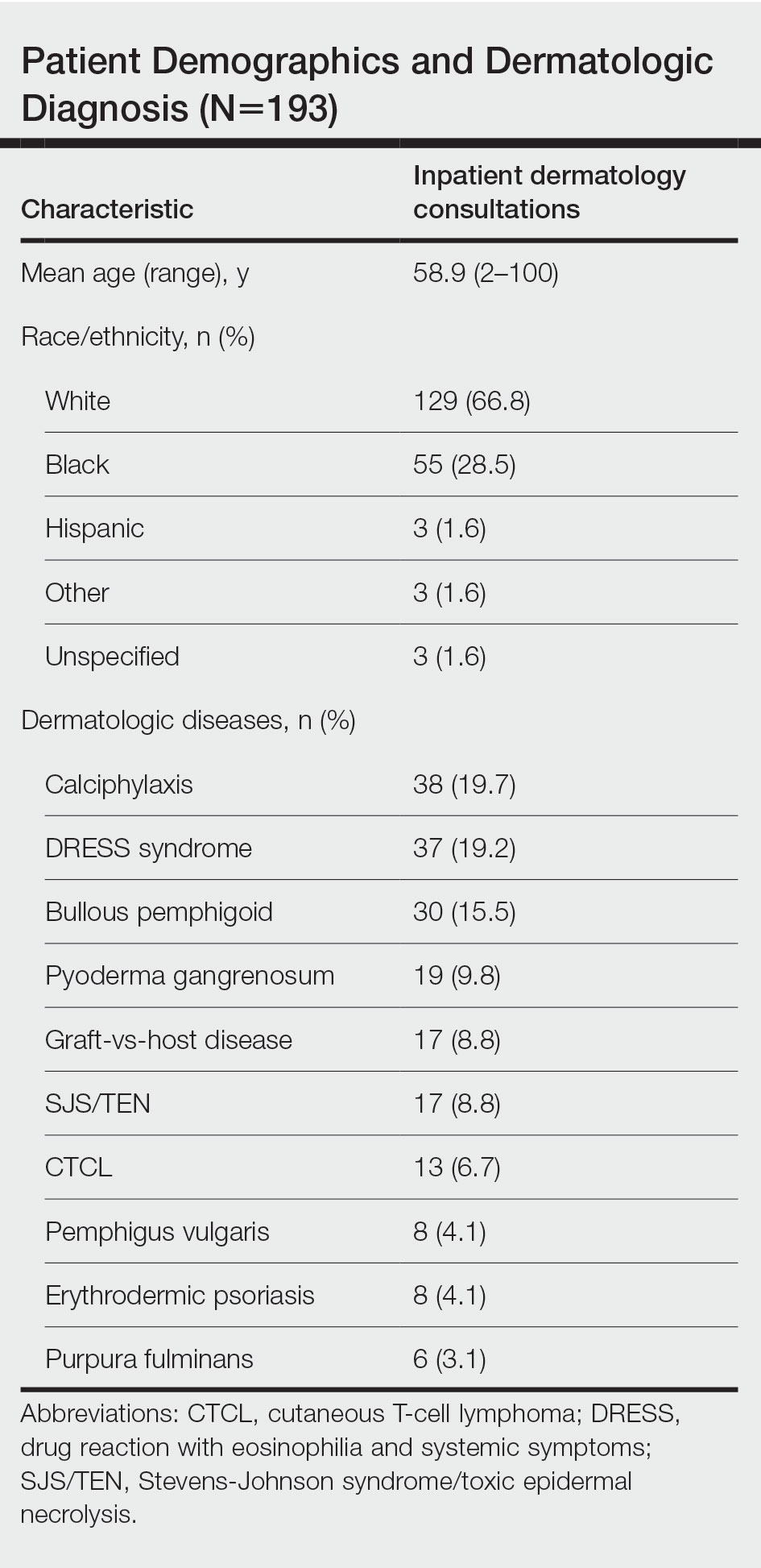

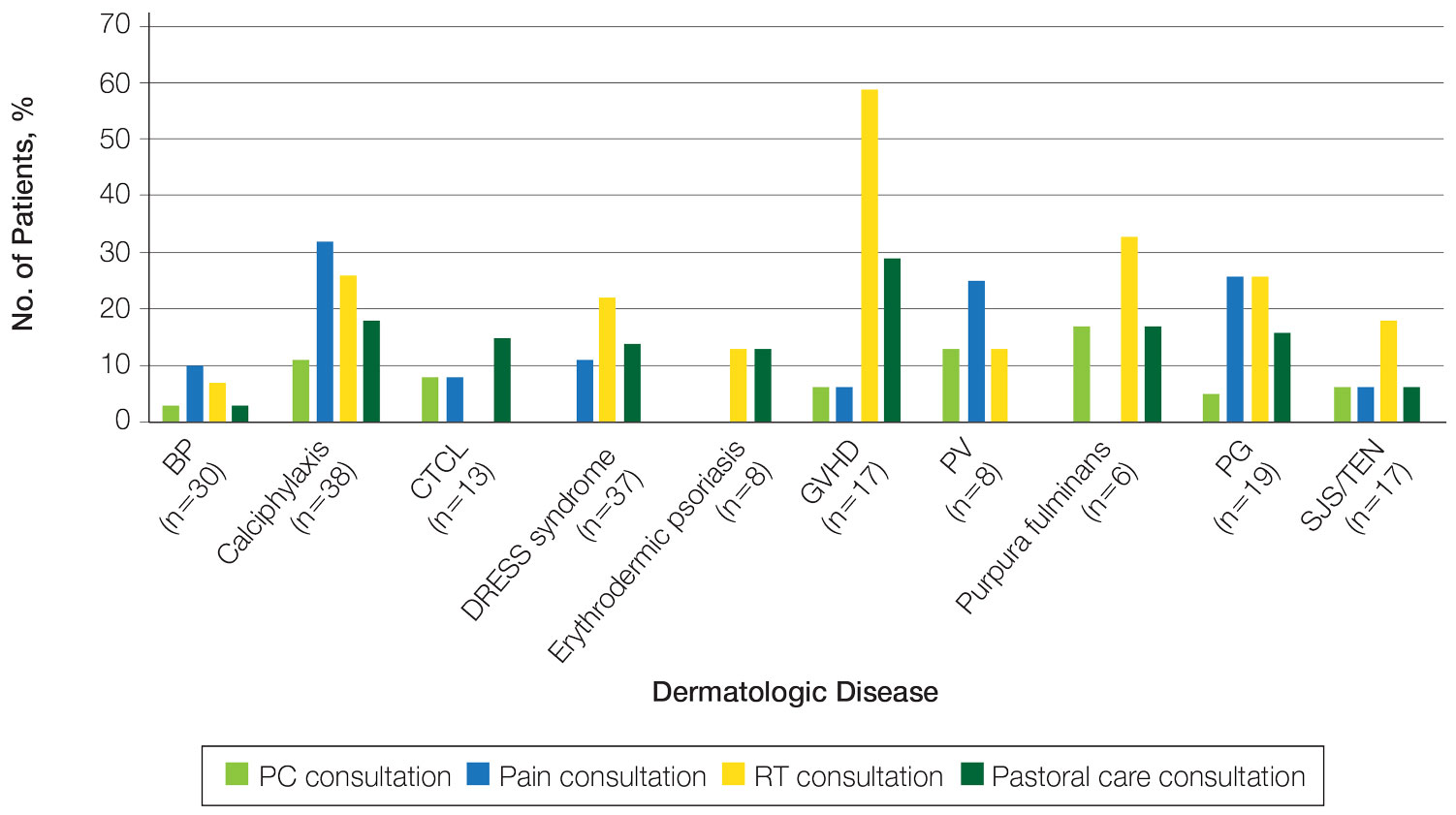

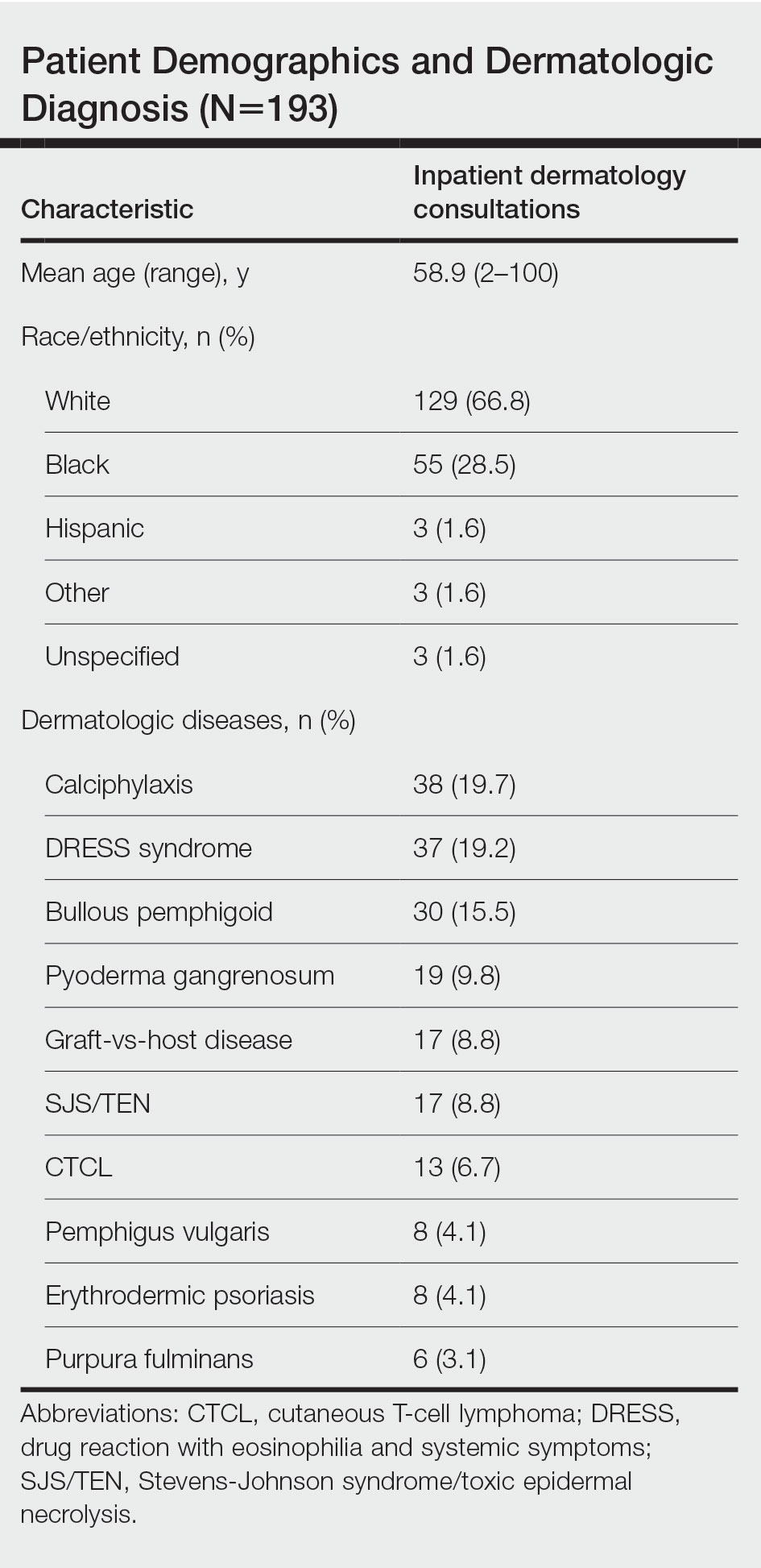

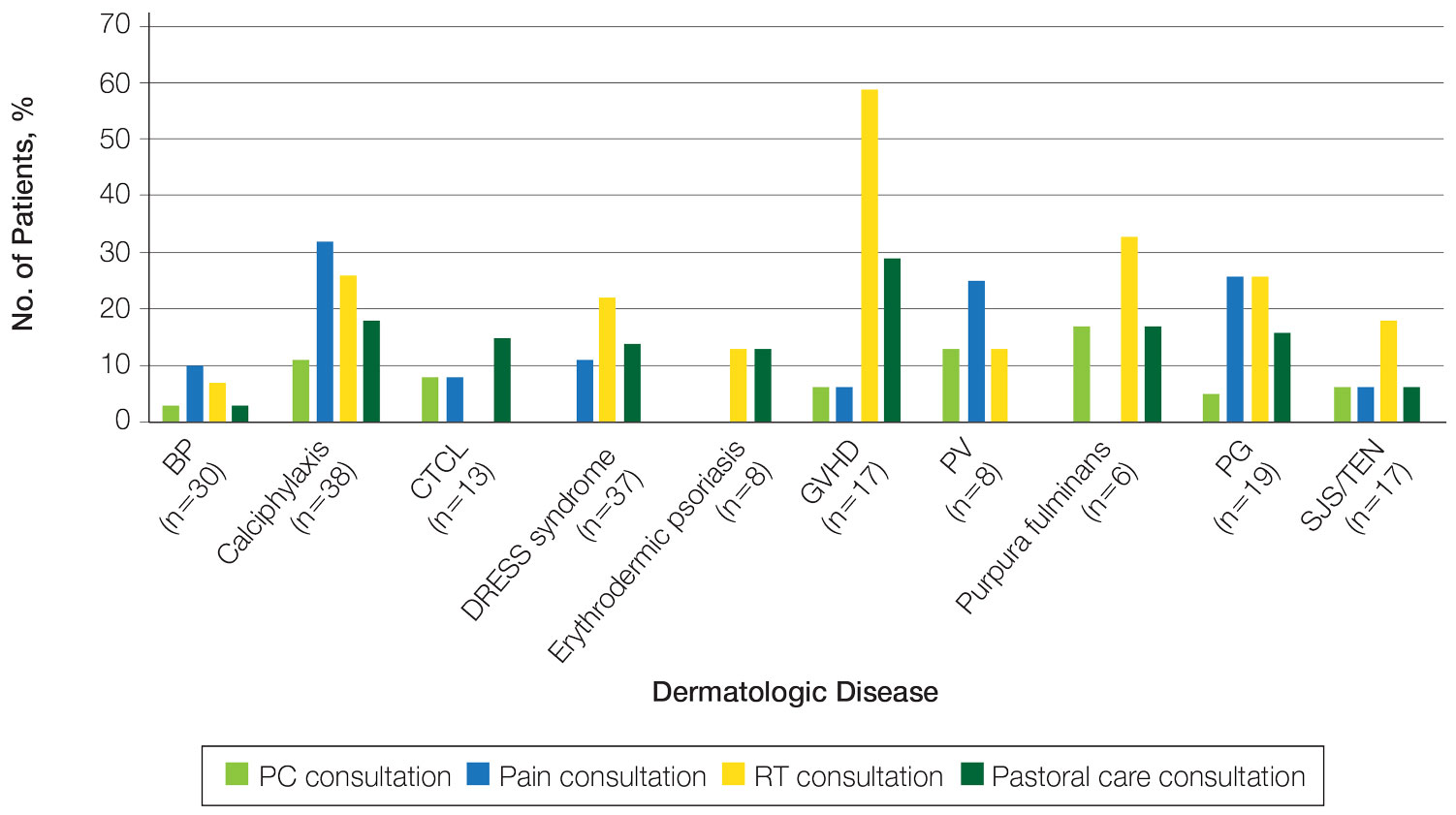

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

Palliative care (PC) is a field of medicine that focuses on improving quality of life by managing physical symptoms as well as mental and spiritual well-being in patients with severe illnesses.1,2 Despite cases of severe dermatologic disease, the use of PC in the field of dermatology is limited, often leaving patients with a range of unmet needs.2,3 In one study that explored PC in patients with melanoma, only one-third of patients with advanced melanoma had a PC consultation.4 Reasons behind the lack of utilization of PC in dermatology include time constraints and limited training in addressing the complex psychosocial needs of patients with severe dermatologic illnesses.1 We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, single-institution study of specific inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period to describe PC utilization among patients who were hospitalized with select severe dermatologic diseases.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study of inpatient dermatology consultations over a 5-year period (October 2016 to October 2021) was performed at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Patients’ medical records were reviewed if they had one of the following diseases: bullous pemphigoid, calciphylaxis, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, erythrodermic psoriasis, graft-vs-host disease, pemphigus vulgaris (PV), purpura fulminans, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. These diseases were selected for inclusion because they have been associated with a documented increase in inpatient mortality and have been described in the published literature on PC in dermatology.2 This study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest University institutional review board.

Use of PC consultative services along with other associated consultative care (ie, recreation therapy [RT], acute pain management, pastoral care) was assessed for each patient. Recreation therapy included specific interventions such as music therapy, arts/craft therapy, pet therapy, and other services with the goal of improving patient cognitive, emotional, and social function. For patients with a completed PC consultation, goals for PC intervention were recorded.

Results

The total study sample included 193 inpatient dermatology consultations. The mean age of the patients was 58.9 years (range, 2–100 years); 66.8% (129/193) were White and 28.5% (55/193) were Black (Table). Palliative care was consulted in 5.7% of cases, with consultations being requested by the primary care team. Reasons for PC consultation included assessment of the patient’s goals of care (4.1% [8/193]), pain management (3.6% [7/193]), non–pain symptom management (2.6% [5/193]), psychosocial support (1.6% [3/193]), and transitions of care (1.0% [2/193]). The average length of patients’ hospital stay prior to PC consultation was 11.5 days(range, 1–32 days). Acute pain management was the reason for consultation in 15.0% of cases (29/193), RT in 21.8% (42/193), and pastoral care in 13.5% (26/193) of cases. Patients with calciphylaxis received the most PC and pain consultations, but fewer than half received these services. Patients with calciphylaxis, PV, purpura fulminans, and CTCL received a higher percentage of PC consultations than the overall cohort, while patients with calciphylaxis, DRESS syndrome, PV, and pyoderma gangrenosum received relatively more pain consultations than the overall cohort (Figure).

Comment

Clinical practice guidelines for quality PC stress the importance of specialists being familiar with these services and the ability to involve PC as part of the treatment plan to achieve better care for patients with serious illnesses.5 Our results demonstrated low rates of PC consultation services for dermatology patients, which supports the existing literature and suggests that PC may be highly underutilized in inpatient settings for patients with serious skin diseases. Use of PC was infrequent and was initiated relatively late in the course of hospital admission, which can negatively impact a patient’s well-being and care experience and can increase the care burden on their caregivers and families.2

Our results suggest a discrepancy in the frequency of formal PC and other palliative consultative services used for dermatologic diseases, with non-PC services including RT, acute pain management, and pastoral care more likely to be utilized. Impacting this finding may be that RT, pastoral care, and acute pain management are provided by nonphysician providers at our institution, not attending faculty staffing PC services. Patients with calciphylaxis were more likely to have PC consultations, potentially due to medicine providers’ familiarity with its morbidity and mortality, as it is commonly associated with end-stage renal disease. Similarly, internal medicine providers may be more familiar with pain classically associated with PG and PV and may be more likely to engage pain experts. Some diseases with notable morbidity and potential mortality were underrepresented including SJS/TEN, erythrodermic psoriasis, CTCL, and GVHD.

Limitations of our study included examination of data from a single institution, as well as the small sample sizes in specific subgroups, which prevented us from making comparisons between diseases. The cross-sectional design also limited our ability to control for confounding variables.

Conclusion

We urge dermatology consultation services to advocate for patients with serious skin diseases andinclude PC consultation as part of their recommendations to primary care teams. Further research should characterize the specific needs of patients that may be addressed by PC services and explore ways dermatologists and others can identify and provide specialty care to hospitalized patients.

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

- Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747-755.

- Thompson LL, Chen ST, Lawton A, et al. Palliative care in dermatology: a clinical primer, review of the literature, and needs assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:708-717. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.029

- Yang CS, Quan VL, Charrow A. The power of a palliative perspective in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:609-610. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.1298

- Osagiede O, Colibaseanu DT, Spaulding AC, et al. Palliative care use among patients with solid cancer tumors. J Palliat Care. 2018;33:149-158.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

Practice Points

- Although severe dermatologic disease negatively impacts patients’ quality of life, palliative care may be underutilized in this population.

- Palliative care should be an integral part of caring for patients who are admitted to the hospital with serious dermatologic illnesses.

Dangerous grandparents

Many decades ago I wrote a book I brazenly titled: “The Good Grandmother Handbook.” I had been a parent for a scant 7 or 8 years but based on my experiences in the office I felt I had accumulated enough wisdom to suggest to women in their fifth to seventh decades how they might conduct themselves around their grandchildren. Luckily, the book never got further than several hundred pages of crudely typed manuscript. This was before word processing programs had settled into the home computer industry, which was still in its infancy.

But I continue find the subject of grandparents interesting. Now, with grandchildren of my own (the oldest has just graduated from high school) and scores of peers knee deep in their own grandparenting adventures, I hope that my perspective now has a bit less of a holier-than-thou aroma.

My most recent muse-prodding event came when I stumbled across an article about the epidemiology of unintentional pediatric firearm fatalities. Looking at 10 years of data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, the investigators found that in 80% of the cases the firearm owner was a relative of the victim; in slightly more than 60% of the cases the event occurred in the victim’s home.

The data set was not granular enough to define the exact relationship between the child and relative who owned the gun. I suspect that most often the relative was a parent or an uncle or aunt. However, viewed through my septuagenarian prism, this paper prompted me to wonder in how many of these fatalities the firearm owner was a grandparent.

I have only anecdotal observations, but I can easily recall situations here in Maine in which a child has been injured by his or her grandfather’s gun. The data from the study show that pediatric fatalities are bimodal, with the majority occurring in the 1- to 5-year age group and a second peak in adolescence. The grandparent-involved cases I can recall were in the younger demographic.

Unfortunately, firearms aren’t the only threat that other grandparents and I pose to the health and safety of our grandchildren. I can remember before the development of, and the widespread use of, tamper-proof pill bottles, “grandma’s purse” overdoses were an unfortunately common occurrence.

More recently, at least here in Maine, we have been hearing more about motorized vehicle–related injuries and fatalities – grandparents backing over their grandchildren in the driveway or, more often, grandfathers (usually) taking their young grandchildren for rides on their snowmobiles, ATVs, lawn tractors, (fill in the blank). Whenever one of these events occurs, my mind quickly jumps beyond the tragic loss of life to imagining what terrible and long-lasting emotional chaos these incidents have spawned in those families.

During the pandemic, many parents and grandparents became aware of the threat that viral-spewing young children pose to the older and more vulnerable generation. On the other hand, many parents have been told that having a grandparent around can present a risk to the health and safety of their grandchildren. It can be a touchy subject in families, and grandparents may bristle at “being treated like a child” when they are reminded that children aren’t small adults and that their own behavior may be setting a bad example or putting their grandchildren at risk.

My generation had to learn how to buckle infants and toddlers into car seats because it was something that wasn’t done for our children. Fortunately, most new grandparents now already have those buckle-and-click skills and mindset. But,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Many decades ago I wrote a book I brazenly titled: “The Good Grandmother Handbook.” I had been a parent for a scant 7 or 8 years but based on my experiences in the office I felt I had accumulated enough wisdom to suggest to women in their fifth to seventh decades how they might conduct themselves around their grandchildren. Luckily, the book never got further than several hundred pages of crudely typed manuscript. This was before word processing programs had settled into the home computer industry, which was still in its infancy.

But I continue find the subject of grandparents interesting. Now, with grandchildren of my own (the oldest has just graduated from high school) and scores of peers knee deep in their own grandparenting adventures, I hope that my perspective now has a bit less of a holier-than-thou aroma.

My most recent muse-prodding event came when I stumbled across an article about the epidemiology of unintentional pediatric firearm fatalities. Looking at 10 years of data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, the investigators found that in 80% of the cases the firearm owner was a relative of the victim; in slightly more than 60% of the cases the event occurred in the victim’s home.

The data set was not granular enough to define the exact relationship between the child and relative who owned the gun. I suspect that most often the relative was a parent or an uncle or aunt. However, viewed through my septuagenarian prism, this paper prompted me to wonder in how many of these fatalities the firearm owner was a grandparent.

I have only anecdotal observations, but I can easily recall situations here in Maine in which a child has been injured by his or her grandfather’s gun. The data from the study show that pediatric fatalities are bimodal, with the majority occurring in the 1- to 5-year age group and a second peak in adolescence. The grandparent-involved cases I can recall were in the younger demographic.

Unfortunately, firearms aren’t the only threat that other grandparents and I pose to the health and safety of our grandchildren. I can remember before the development of, and the widespread use of, tamper-proof pill bottles, “grandma’s purse” overdoses were an unfortunately common occurrence.

More recently, at least here in Maine, we have been hearing more about motorized vehicle–related injuries and fatalities – grandparents backing over their grandchildren in the driveway or, more often, grandfathers (usually) taking their young grandchildren for rides on their snowmobiles, ATVs, lawn tractors, (fill in the blank). Whenever one of these events occurs, my mind quickly jumps beyond the tragic loss of life to imagining what terrible and long-lasting emotional chaos these incidents have spawned in those families.

During the pandemic, many parents and grandparents became aware of the threat that viral-spewing young children pose to the older and more vulnerable generation. On the other hand, many parents have been told that having a grandparent around can present a risk to the health and safety of their grandchildren. It can be a touchy subject in families, and grandparents may bristle at “being treated like a child” when they are reminded that children aren’t small adults and that their own behavior may be setting a bad example or putting their grandchildren at risk.

My generation had to learn how to buckle infants and toddlers into car seats because it was something that wasn’t done for our children. Fortunately, most new grandparents now already have those buckle-and-click skills and mindset. But,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Many decades ago I wrote a book I brazenly titled: “The Good Grandmother Handbook.” I had been a parent for a scant 7 or 8 years but based on my experiences in the office I felt I had accumulated enough wisdom to suggest to women in their fifth to seventh decades how they might conduct themselves around their grandchildren. Luckily, the book never got further than several hundred pages of crudely typed manuscript. This was before word processing programs had settled into the home computer industry, which was still in its infancy.

But I continue find the subject of grandparents interesting. Now, with grandchildren of my own (the oldest has just graduated from high school) and scores of peers knee deep in their own grandparenting adventures, I hope that my perspective now has a bit less of a holier-than-thou aroma.

My most recent muse-prodding event came when I stumbled across an article about the epidemiology of unintentional pediatric firearm fatalities. Looking at 10 years of data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, the investigators found that in 80% of the cases the firearm owner was a relative of the victim; in slightly more than 60% of the cases the event occurred in the victim’s home.

The data set was not granular enough to define the exact relationship between the child and relative who owned the gun. I suspect that most often the relative was a parent or an uncle or aunt. However, viewed through my septuagenarian prism, this paper prompted me to wonder in how many of these fatalities the firearm owner was a grandparent.

I have only anecdotal observations, but I can easily recall situations here in Maine in which a child has been injured by his or her grandfather’s gun. The data from the study show that pediatric fatalities are bimodal, with the majority occurring in the 1- to 5-year age group and a second peak in adolescence. The grandparent-involved cases I can recall were in the younger demographic.

Unfortunately, firearms aren’t the only threat that other grandparents and I pose to the health and safety of our grandchildren. I can remember before the development of, and the widespread use of, tamper-proof pill bottles, “grandma’s purse” overdoses were an unfortunately common occurrence.

More recently, at least here in Maine, we have been hearing more about motorized vehicle–related injuries and fatalities – grandparents backing over their grandchildren in the driveway or, more often, grandfathers (usually) taking their young grandchildren for rides on their snowmobiles, ATVs, lawn tractors, (fill in the blank). Whenever one of these events occurs, my mind quickly jumps beyond the tragic loss of life to imagining what terrible and long-lasting emotional chaos these incidents have spawned in those families.

During the pandemic, many parents and grandparents became aware of the threat that viral-spewing young children pose to the older and more vulnerable generation. On the other hand, many parents have been told that having a grandparent around can present a risk to the health and safety of their grandchildren. It can be a touchy subject in families, and grandparents may bristle at “being treated like a child” when they are reminded that children aren’t small adults and that their own behavior may be setting a bad example or putting their grandchildren at risk.

My generation had to learn how to buckle infants and toddlers into car seats because it was something that wasn’t done for our children. Fortunately, most new grandparents now already have those buckle-and-click skills and mindset. But,

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

What is the proper treatment for posttraumatic headache? Expert debate

AUSTIN, TEX – There are no guidelines available, nor is there much quality evidence to support one decision or another, according to two experts who debated the question at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Early treatment

Frank Conidi, DO, spoke first, and pointed out the need to define both early treatment and the condition being treated. Is it early-treatment abortive, is it preventative, and if the patient has a concussion, is it a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), or severe TBI?

The majority of patients with posttraumatic headache will meet criteria for migraine or probable migraine. “It can be anywhere from 58% to upwards of 90%. And if you see these patients, it makes sense, because posttraumatic headache patients are disabled by their headaches,” said Dr. Conidi, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology.

He argued for early treatment to reduce chronification. “We know that if headaches are left untreated, they’re going to start to spiral up and become daily. This leads to the development of peripheral and central sensitization and lowers the threshold for further migraine attacks,” said Dr. Conidi.

He noted that patients with posttraumatic headache often have comorbidities such as sleep issues, neck pain, or posttraumatic stress disorder, all of which are risk factors for chronification. Treatment does not necessarily mean medication, however. “The mainstay of posttraumatic headache treatment is actually physical and cognitive activity to tolerance. And what I call the 20/5 rule: 20 minutes of physical activity with 5-minute chill breaks. In addition, we use light sub-aerobic exercise 3 to 5 days out in concussion, [which] has been shown to improve concussion recovery time,” he said.

Dr. Conidi suggested treatment of triggers, such as neck issues and whiplash symptoms. “Probably the best treatment I’ve ever seen, and I published on this, are pericranial nerve blocks. Pericranial nerve blocks work wonderfully. If you’re going to block the pericranial nerves, block them all, not just the occipital. Block the trigeminal branches. I’ve actually been able to locate a little two-and-a-half-inch plastic Luer-lock catheter that I can hook on a 1-cc syringe with viscous lidocaine, and I can do sphenopalatine ganglion blocks on all my patients now for under 25 cents. So we’ve been combining the nerve blocks, and we’ve been using them early. Oftentimes the patients won’t have any further headaches, especially if it’s [after] a concussion,” he said.

With respect to concussion-related posttraumatic headache, he summed up: “We’re aggressive early. We’re using intervention. We’re layering our treatment. We’re using medications: prednisone, NSAIDS, and now we have gepants. We’ve been having good success with using gepants,” he said.

Treatment of TBI patients is broadly similar, with the main difference being that neurologists typically won’t see such patients early on as they may be in rehab facilities or hospitals for extended periods. “You may not be getting [to see] them for 1 or 2 months. In that case, you want to educate your neurosurgery and your [physical medicine and rehabilitation] colleagues on the treatment.

Finally, he described work that his group has done in using stimulants for posttraumatic headache. “Stimulants not only treat the cognitive symptoms, but they give the patient cognitive reserve and we find that it gets the patient through the day so they actually have less headaches. It’s a form of prevention. I know there are shortages nationally of both Adderall and Ritalin, but we have had excellent results in our posttraumatic patients using these types of medications,” said Dr. Conidi.

Delayed treatment

Amaal J. Starling, MD, offered a counterargument, but she narrowed the question down to whether preventive treatment should be used within one and a half months of the injury, which she defined as early treatment. Her argument against early preventive treatment centered around the core value of beneficence – to act for the benefit of the patient, and avoid harm.

She discussed the natural history of posttraumatic headache, which is largely self-limited. For example, an NCAA study that found 88% of concussions had symptom resolution within 1 week, and 86% of posttraumatic headache resolved within 1 week. “If individuals routinely are having a self-limited course, there is no need for early treatment with a preventive treatment option because the majority of posttraumatic headache is resolving within that one-and-a-half-month postinjury threshold. The better recommendation, as provided in evidence from Dr. Conidi’s presentation, is to provide supportive care, including acute medications or acute treatment options like nerve blocks for acute pain relief and symptom relief,” said Dr. Starling, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Dr. Starling expressed concern that preventive medications could lead to worsening of comorbidities. For example, posttraumatic headache is often associated with autonomic dysfunction and visual vestibular dysfunction. The former commonly occurs with concussion and is similar to postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and the second most common symptom of POTS is headache, according to Dr. Starling. Posttraumatic POTS is treated similarly to idiopathic POTS, with a nonpharmacologic approach. One element of POTS management is to withdraw exacerbating medications such as beta-blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and SNRIs. “These look strikingly similar to some of the headache preventive medications that we might consider for somebody, and so the concern is early preventive treatment with these medications to treat the posttraumatic headache may actually worsen some of these comorbidities that are present in our posttraumatic headache patients. We have to be careful about potentially exacerbating comorbidities with early preventive treatment,” she said.

Prevention medications for headache can also worsen visual vestibular dysfunction, such as dizziness. There are some data suggesting that vestibular rehabilitation and vision therapy can improve dizziness, but also headache. “We all know that many of our preventive medications for headache could potentially exacerbate visual vestibular symptoms, so we have to be careful about that. So again, first do no harm. Posttraumatic POTS is common and causes headache. Posttraumatic vestibular dysfunction is common and causes headache. Instead of initiating a headache preventive medication early, we recommend to identify these comorbidities and provide targeted treatment. Treatment of these comorbidities may, in and of itself, improve the headache. We also we have to be careful because some preventive medications may worsen the comorbidities,” said Dr. Starling.

Areas of agreement

Dr. Conidi agreed that preventative treatment is less likely to be needed for concussion patients, but said that TBI patients are more likely to require it to prevent chronification. Dr. Starling agreed that chronification is an important concern, but she noted that many posttraumatic headache patients are athletes, and preventative medications can also lead to issues that might interfere with return to play, such as decreased sweating, or weight gain or loss. This is complicated by the fact that titration and weaning periods can be long. “We have to be very careful about these medications’ side effects, especially when we don’t have the evidence to demonstrate that it is worth the potential risk of being put on these medications,” she said.

The debate led Catherin Chong, PhD, to ask about the state of the field. “There’s a posttraumatic headache special interest section here [at AHS 2023], and the question that really is coming up at every meeting is, is there some coherence in the field? Is it too early or is it time for a position statement?” asked Dr. Chong, a career scientist at Mayo Clinic (Phoenix). Dr. Chong comoderated the debate and ensuing discussion.

Dr. Starling felt it’s too early for a position statement, but a scoping review could identify research questions that could lead to a position statement. “I’m really excited about the work that’s being done to identify the cohort of individuals with acute posttraumatic headache that may chronify to persistent posttraumatic headache so that we can minimize the risk of exposing the large cohort that’s going to be likely self-limited to a treatment option. Then we can identify those individuals where that risk is worth it because they’re the ones that could lead to chronification. Figuring out if that’s looking at levels of allodynia or other factors that can [help identify those at most risk] would be important,” she said.

Dr. Conidi agreed with the need for more information on the parameters to be studied, but he expressed the belief that any position statement would be a consensus statement. “It’s not going to have any hard evidence behind it, but I do think we need [a position statement]. Even in the general neurology world, there’s a huge lack of understanding of how to treat these patients,” he said.

Dr. Conidi did not make any disclosures. Dr. Starling has consulted for AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Axsome Therapeutics, Everyday Health, Lundbeck, Med-IQ, Medscape, Neurolief, Satsuma, and WebMD. Dr. Chong has no relevant financial disclosures.

AUSTIN, TEX – There are no guidelines available, nor is there much quality evidence to support one decision or another, according to two experts who debated the question at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Early treatment

Frank Conidi, DO, spoke first, and pointed out the need to define both early treatment and the condition being treated. Is it early-treatment abortive, is it preventative, and if the patient has a concussion, is it a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), or severe TBI?

The majority of patients with posttraumatic headache will meet criteria for migraine or probable migraine. “It can be anywhere from 58% to upwards of 90%. And if you see these patients, it makes sense, because posttraumatic headache patients are disabled by their headaches,” said Dr. Conidi, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology.

He argued for early treatment to reduce chronification. “We know that if headaches are left untreated, they’re going to start to spiral up and become daily. This leads to the development of peripheral and central sensitization and lowers the threshold for further migraine attacks,” said Dr. Conidi.

He noted that patients with posttraumatic headache often have comorbidities such as sleep issues, neck pain, or posttraumatic stress disorder, all of which are risk factors for chronification. Treatment does not necessarily mean medication, however. “The mainstay of posttraumatic headache treatment is actually physical and cognitive activity to tolerance. And what I call the 20/5 rule: 20 minutes of physical activity with 5-minute chill breaks. In addition, we use light sub-aerobic exercise 3 to 5 days out in concussion, [which] has been shown to improve concussion recovery time,” he said.

Dr. Conidi suggested treatment of triggers, such as neck issues and whiplash symptoms. “Probably the best treatment I’ve ever seen, and I published on this, are pericranial nerve blocks. Pericranial nerve blocks work wonderfully. If you’re going to block the pericranial nerves, block them all, not just the occipital. Block the trigeminal branches. I’ve actually been able to locate a little two-and-a-half-inch plastic Luer-lock catheter that I can hook on a 1-cc syringe with viscous lidocaine, and I can do sphenopalatine ganglion blocks on all my patients now for under 25 cents. So we’ve been combining the nerve blocks, and we’ve been using them early. Oftentimes the patients won’t have any further headaches, especially if it’s [after] a concussion,” he said.

With respect to concussion-related posttraumatic headache, he summed up: “We’re aggressive early. We’re using intervention. We’re layering our treatment. We’re using medications: prednisone, NSAIDS, and now we have gepants. We’ve been having good success with using gepants,” he said.

Treatment of TBI patients is broadly similar, with the main difference being that neurologists typically won’t see such patients early on as they may be in rehab facilities or hospitals for extended periods. “You may not be getting [to see] them for 1 or 2 months. In that case, you want to educate your neurosurgery and your [physical medicine and rehabilitation] colleagues on the treatment.

Finally, he described work that his group has done in using stimulants for posttraumatic headache. “Stimulants not only treat the cognitive symptoms, but they give the patient cognitive reserve and we find that it gets the patient through the day so they actually have less headaches. It’s a form of prevention. I know there are shortages nationally of both Adderall and Ritalin, but we have had excellent results in our posttraumatic patients using these types of medications,” said Dr. Conidi.

Delayed treatment

Amaal J. Starling, MD, offered a counterargument, but she narrowed the question down to whether preventive treatment should be used within one and a half months of the injury, which she defined as early treatment. Her argument against early preventive treatment centered around the core value of beneficence – to act for the benefit of the patient, and avoid harm.

She discussed the natural history of posttraumatic headache, which is largely self-limited. For example, an NCAA study that found 88% of concussions had symptom resolution within 1 week, and 86% of posttraumatic headache resolved within 1 week. “If individuals routinely are having a self-limited course, there is no need for early treatment with a preventive treatment option because the majority of posttraumatic headache is resolving within that one-and-a-half-month postinjury threshold. The better recommendation, as provided in evidence from Dr. Conidi’s presentation, is to provide supportive care, including acute medications or acute treatment options like nerve blocks for acute pain relief and symptom relief,” said Dr. Starling, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Dr. Starling expressed concern that preventive medications could lead to worsening of comorbidities. For example, posttraumatic headache is often associated with autonomic dysfunction and visual vestibular dysfunction. The former commonly occurs with concussion and is similar to postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and the second most common symptom of POTS is headache, according to Dr. Starling. Posttraumatic POTS is treated similarly to idiopathic POTS, with a nonpharmacologic approach. One element of POTS management is to withdraw exacerbating medications such as beta-blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and SNRIs. “These look strikingly similar to some of the headache preventive medications that we might consider for somebody, and so the concern is early preventive treatment with these medications to treat the posttraumatic headache may actually worsen some of these comorbidities that are present in our posttraumatic headache patients. We have to be careful about potentially exacerbating comorbidities with early preventive treatment,” she said.

Prevention medications for headache can also worsen visual vestibular dysfunction, such as dizziness. There are some data suggesting that vestibular rehabilitation and vision therapy can improve dizziness, but also headache. “We all know that many of our preventive medications for headache could potentially exacerbate visual vestibular symptoms, so we have to be careful about that. So again, first do no harm. Posttraumatic POTS is common and causes headache. Posttraumatic vestibular dysfunction is common and causes headache. Instead of initiating a headache preventive medication early, we recommend to identify these comorbidities and provide targeted treatment. Treatment of these comorbidities may, in and of itself, improve the headache. We also we have to be careful because some preventive medications may worsen the comorbidities,” said Dr. Starling.

Areas of agreement

Dr. Conidi agreed that preventative treatment is less likely to be needed for concussion patients, but said that TBI patients are more likely to require it to prevent chronification. Dr. Starling agreed that chronification is an important concern, but she noted that many posttraumatic headache patients are athletes, and preventative medications can also lead to issues that might interfere with return to play, such as decreased sweating, or weight gain or loss. This is complicated by the fact that titration and weaning periods can be long. “We have to be very careful about these medications’ side effects, especially when we don’t have the evidence to demonstrate that it is worth the potential risk of being put on these medications,” she said.

The debate led Catherin Chong, PhD, to ask about the state of the field. “There’s a posttraumatic headache special interest section here [at AHS 2023], and the question that really is coming up at every meeting is, is there some coherence in the field? Is it too early or is it time for a position statement?” asked Dr. Chong, a career scientist at Mayo Clinic (Phoenix). Dr. Chong comoderated the debate and ensuing discussion.

Dr. Starling felt it’s too early for a position statement, but a scoping review could identify research questions that could lead to a position statement. “I’m really excited about the work that’s being done to identify the cohort of individuals with acute posttraumatic headache that may chronify to persistent posttraumatic headache so that we can minimize the risk of exposing the large cohort that’s going to be likely self-limited to a treatment option. Then we can identify those individuals where that risk is worth it because they’re the ones that could lead to chronification. Figuring out if that’s looking at levels of allodynia or other factors that can [help identify those at most risk] would be important,” she said.

Dr. Conidi agreed with the need for more information on the parameters to be studied, but he expressed the belief that any position statement would be a consensus statement. “It’s not going to have any hard evidence behind it, but I do think we need [a position statement]. Even in the general neurology world, there’s a huge lack of understanding of how to treat these patients,” he said.

Dr. Conidi did not make any disclosures. Dr. Starling has consulted for AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Axsome Therapeutics, Everyday Health, Lundbeck, Med-IQ, Medscape, Neurolief, Satsuma, and WebMD. Dr. Chong has no relevant financial disclosures.

AUSTIN, TEX – There are no guidelines available, nor is there much quality evidence to support one decision or another, according to two experts who debated the question at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Early treatment

Frank Conidi, DO, spoke first, and pointed out the need to define both early treatment and the condition being treated. Is it early-treatment abortive, is it preventative, and if the patient has a concussion, is it a mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), or severe TBI?

The majority of patients with posttraumatic headache will meet criteria for migraine or probable migraine. “It can be anywhere from 58% to upwards of 90%. And if you see these patients, it makes sense, because posttraumatic headache patients are disabled by their headaches,” said Dr. Conidi, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology.

He argued for early treatment to reduce chronification. “We know that if headaches are left untreated, they’re going to start to spiral up and become daily. This leads to the development of peripheral and central sensitization and lowers the threshold for further migraine attacks,” said Dr. Conidi.

He noted that patients with posttraumatic headache often have comorbidities such as sleep issues, neck pain, or posttraumatic stress disorder, all of which are risk factors for chronification. Treatment does not necessarily mean medication, however. “The mainstay of posttraumatic headache treatment is actually physical and cognitive activity to tolerance. And what I call the 20/5 rule: 20 minutes of physical activity with 5-minute chill breaks. In addition, we use light sub-aerobic exercise 3 to 5 days out in concussion, [which] has been shown to improve concussion recovery time,” he said.

Dr. Conidi suggested treatment of triggers, such as neck issues and whiplash symptoms. “Probably the best treatment I’ve ever seen, and I published on this, are pericranial nerve blocks. Pericranial nerve blocks work wonderfully. If you’re going to block the pericranial nerves, block them all, not just the occipital. Block the trigeminal branches. I’ve actually been able to locate a little two-and-a-half-inch plastic Luer-lock catheter that I can hook on a 1-cc syringe with viscous lidocaine, and I can do sphenopalatine ganglion blocks on all my patients now for under 25 cents. So we’ve been combining the nerve blocks, and we’ve been using them early. Oftentimes the patients won’t have any further headaches, especially if it’s [after] a concussion,” he said.

With respect to concussion-related posttraumatic headache, he summed up: “We’re aggressive early. We’re using intervention. We’re layering our treatment. We’re using medications: prednisone, NSAIDS, and now we have gepants. We’ve been having good success with using gepants,” he said.

Treatment of TBI patients is broadly similar, with the main difference being that neurologists typically won’t see such patients early on as they may be in rehab facilities or hospitals for extended periods. “You may not be getting [to see] them for 1 or 2 months. In that case, you want to educate your neurosurgery and your [physical medicine and rehabilitation] colleagues on the treatment.

Finally, he described work that his group has done in using stimulants for posttraumatic headache. “Stimulants not only treat the cognitive symptoms, but they give the patient cognitive reserve and we find that it gets the patient through the day so they actually have less headaches. It’s a form of prevention. I know there are shortages nationally of both Adderall and Ritalin, but we have had excellent results in our posttraumatic patients using these types of medications,” said Dr. Conidi.

Delayed treatment

Amaal J. Starling, MD, offered a counterargument, but she narrowed the question down to whether preventive treatment should be used within one and a half months of the injury, which she defined as early treatment. Her argument against early preventive treatment centered around the core value of beneficence – to act for the benefit of the patient, and avoid harm.

She discussed the natural history of posttraumatic headache, which is largely self-limited. For example, an NCAA study that found 88% of concussions had symptom resolution within 1 week, and 86% of posttraumatic headache resolved within 1 week. “If individuals routinely are having a self-limited course, there is no need for early treatment with a preventive treatment option because the majority of posttraumatic headache is resolving within that one-and-a-half-month postinjury threshold. The better recommendation, as provided in evidence from Dr. Conidi’s presentation, is to provide supportive care, including acute medications or acute treatment options like nerve blocks for acute pain relief and symptom relief,” said Dr. Starling, associate professor of neurology at Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Dr. Starling expressed concern that preventive medications could lead to worsening of comorbidities. For example, posttraumatic headache is often associated with autonomic dysfunction and visual vestibular dysfunction. The former commonly occurs with concussion and is similar to postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and the second most common symptom of POTS is headache, according to Dr. Starling. Posttraumatic POTS is treated similarly to idiopathic POTS, with a nonpharmacologic approach. One element of POTS management is to withdraw exacerbating medications such as beta-blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and SNRIs. “These look strikingly similar to some of the headache preventive medications that we might consider for somebody, and so the concern is early preventive treatment with these medications to treat the posttraumatic headache may actually worsen some of these comorbidities that are present in our posttraumatic headache patients. We have to be careful about potentially exacerbating comorbidities with early preventive treatment,” she said.

Prevention medications for headache can also worsen visual vestibular dysfunction, such as dizziness. There are some data suggesting that vestibular rehabilitation and vision therapy can improve dizziness, but also headache. “We all know that many of our preventive medications for headache could potentially exacerbate visual vestibular symptoms, so we have to be careful about that. So again, first do no harm. Posttraumatic POTS is common and causes headache. Posttraumatic vestibular dysfunction is common and causes headache. Instead of initiating a headache preventive medication early, we recommend to identify these comorbidities and provide targeted treatment. Treatment of these comorbidities may, in and of itself, improve the headache. We also we have to be careful because some preventive medications may worsen the comorbidities,” said Dr. Starling.

Areas of agreement

Dr. Conidi agreed that preventative treatment is less likely to be needed for concussion patients, but said that TBI patients are more likely to require it to prevent chronification. Dr. Starling agreed that chronification is an important concern, but she noted that many posttraumatic headache patients are athletes, and preventative medications can also lead to issues that might interfere with return to play, such as decreased sweating, or weight gain or loss. This is complicated by the fact that titration and weaning periods can be long. “We have to be very careful about these medications’ side effects, especially when we don’t have the evidence to demonstrate that it is worth the potential risk of being put on these medications,” she said.

The debate led Catherin Chong, PhD, to ask about the state of the field. “There’s a posttraumatic headache special interest section here [at AHS 2023], and the question that really is coming up at every meeting is, is there some coherence in the field? Is it too early or is it time for a position statement?” asked Dr. Chong, a career scientist at Mayo Clinic (Phoenix). Dr. Chong comoderated the debate and ensuing discussion.

Dr. Starling felt it’s too early for a position statement, but a scoping review could identify research questions that could lead to a position statement. “I’m really excited about the work that’s being done to identify the cohort of individuals with acute posttraumatic headache that may chronify to persistent posttraumatic headache so that we can minimize the risk of exposing the large cohort that’s going to be likely self-limited to a treatment option. Then we can identify those individuals where that risk is worth it because they’re the ones that could lead to chronification. Figuring out if that’s looking at levels of allodynia or other factors that can [help identify those at most risk] would be important,” she said.

Dr. Conidi agreed with the need for more information on the parameters to be studied, but he expressed the belief that any position statement would be a consensus statement. “It’s not going to have any hard evidence behind it, but I do think we need [a position statement]. Even in the general neurology world, there’s a huge lack of understanding of how to treat these patients,” he said.

Dr. Conidi did not make any disclosures. Dr. Starling has consulted for AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Axsome Therapeutics, Everyday Health, Lundbeck, Med-IQ, Medscape, Neurolief, Satsuma, and WebMD. Dr. Chong has no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AHS 2023

Painful, Nonhealing, Violaceus Plaque on the Right Breast

The Diagnosis: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

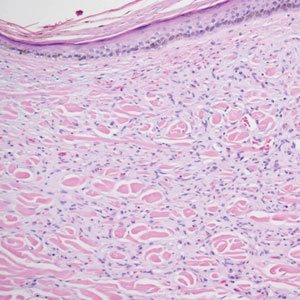

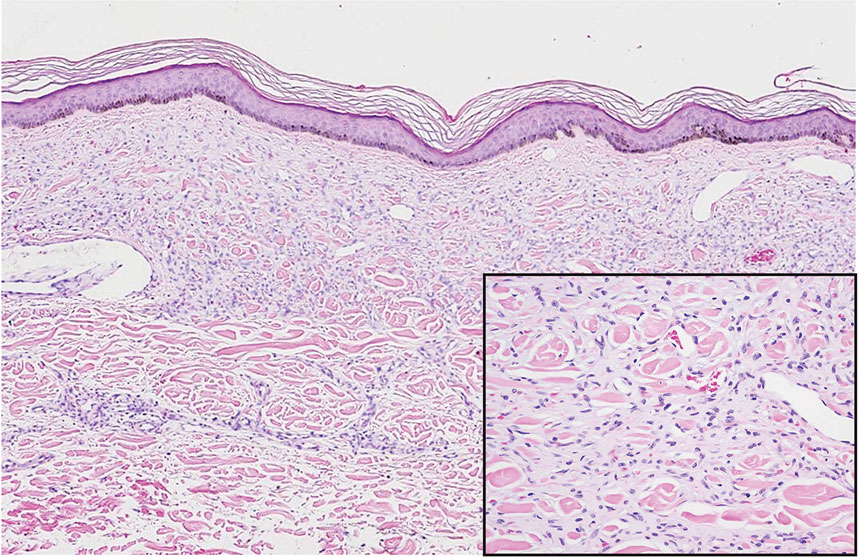

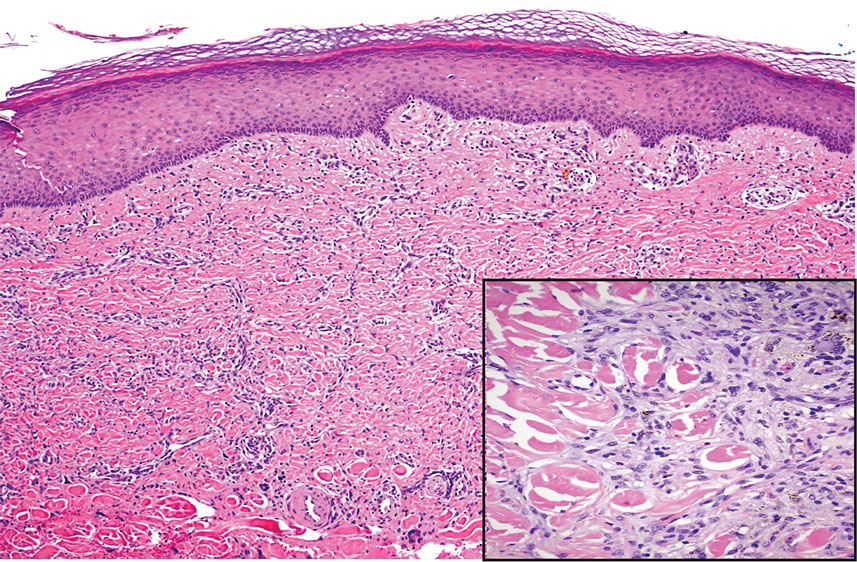

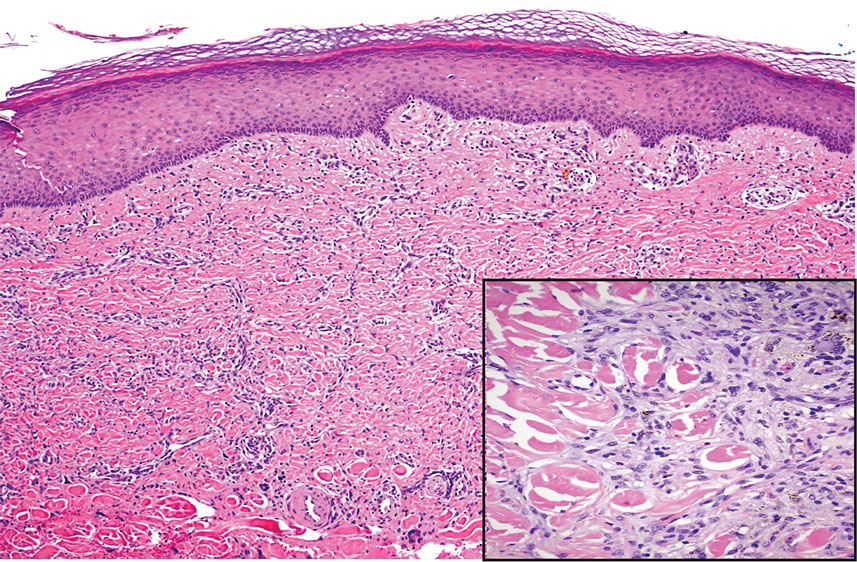

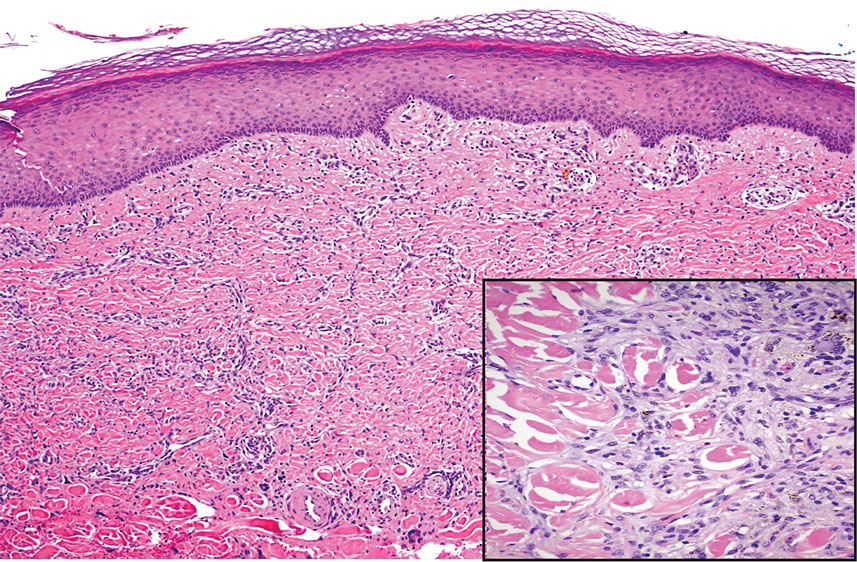

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is an acquired reactive vascular proliferation in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Clinically, DDA presents as violaceous reticulated plaques, often with secondary ulceration and sometimes necrosis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis more commonly presents in patients with a history of severe peripheral vascular disease, coagulopathies, or infection, and it frequently arises on the extremities. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis also has been shown to develop on the breasts, particularly in patients with pendulous breast tissue. Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to be from ischemia and hypoxia, leading to angiogenesis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized histologically by the presence of a diffuse proliferation of spindled endothelial cells distributed between the collagen bundles throughout the dermis (quiz image and Figure 1). Spindle-shaped endothelial cells exhibit a vacuolated cytoplasm. On immunohistochemistry, these dermal spindle cells classically stain positive for CD31, CD34, and erythroblast transformation specific–related gene (Erg) and stain negative for both human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and factor XIIIa.

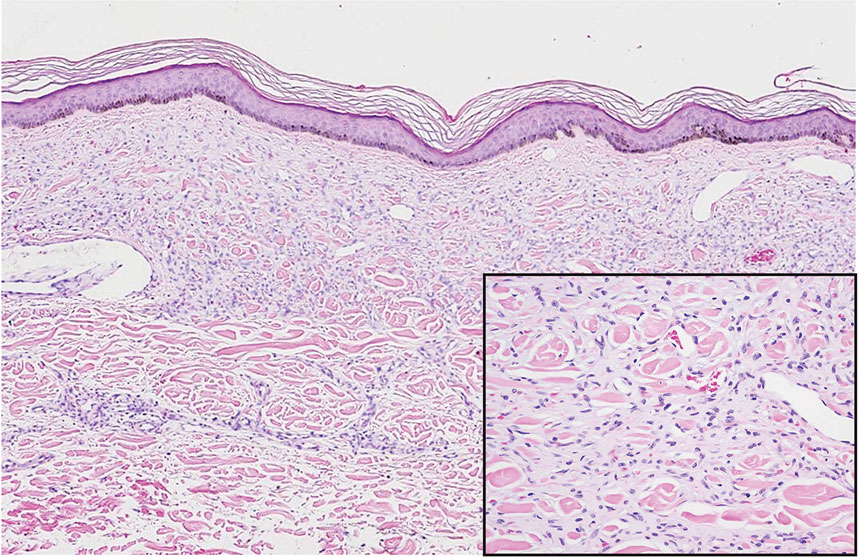

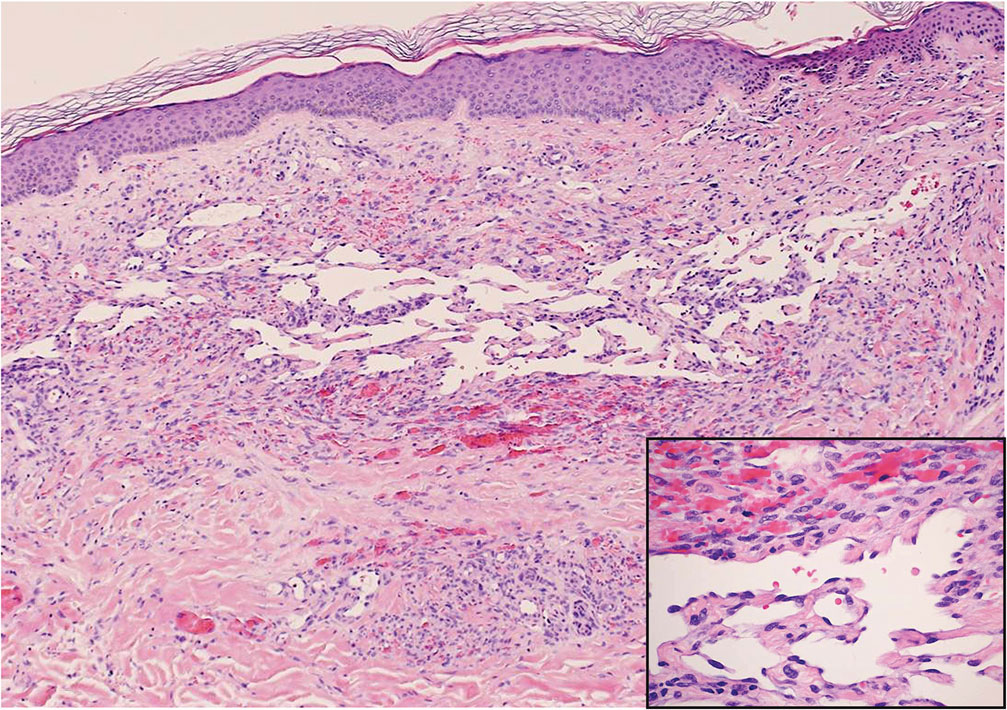

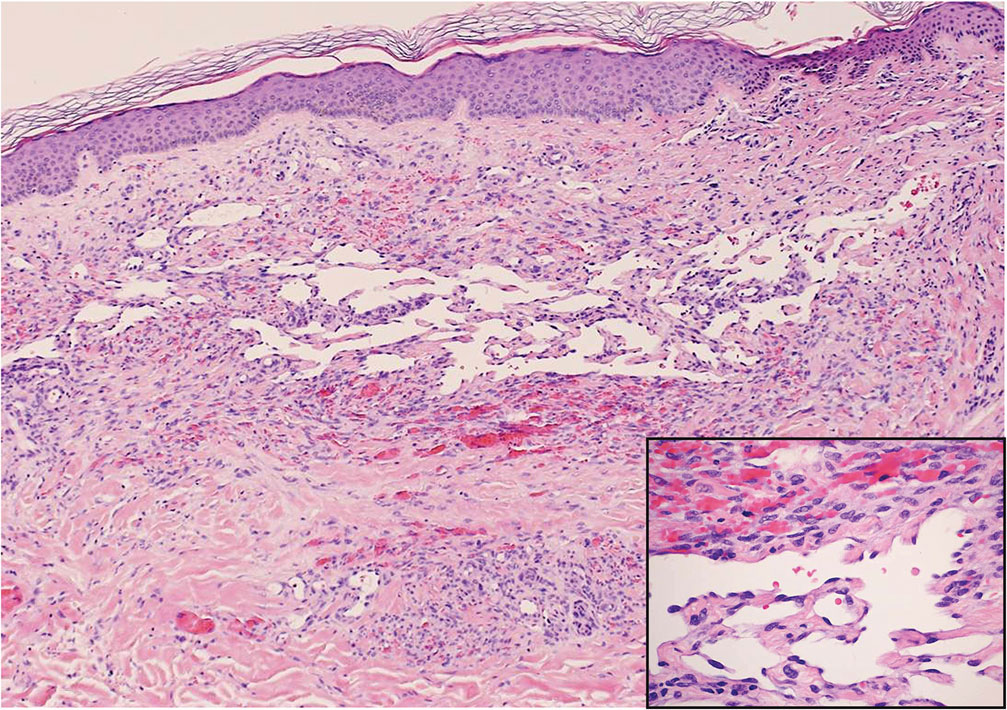

Cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma, more commonly referred to as dermatofibroma, is a common benign lesion that presents clinically as a solitary firm nodule most commonly on the extremities in areas of repetitive trauma or pressure. It classically exhibits dimpling of the overlaying skin with lateral pressure on the lesion, known as the dimple sign.4 Histologically, dermatofibromas share similar features to DDA and demonstrate the presence of bland-appearing spindle cells within the dermis between the collagen bundles, resulting in collagen trapping. However, a distinguishing histologic feature of a dermatofibroma in comparison to DDA is the presence of epidermal hyperplasia overlying the dermatofibroma, leading to tabled rete ridges (Figure 2). Spindle cells in dermatofibromas are fibroblasts and have a distinct immunophenotype that includes factor XIIIa positivity and negative staining for CD31, CD34, and Erg.4,5

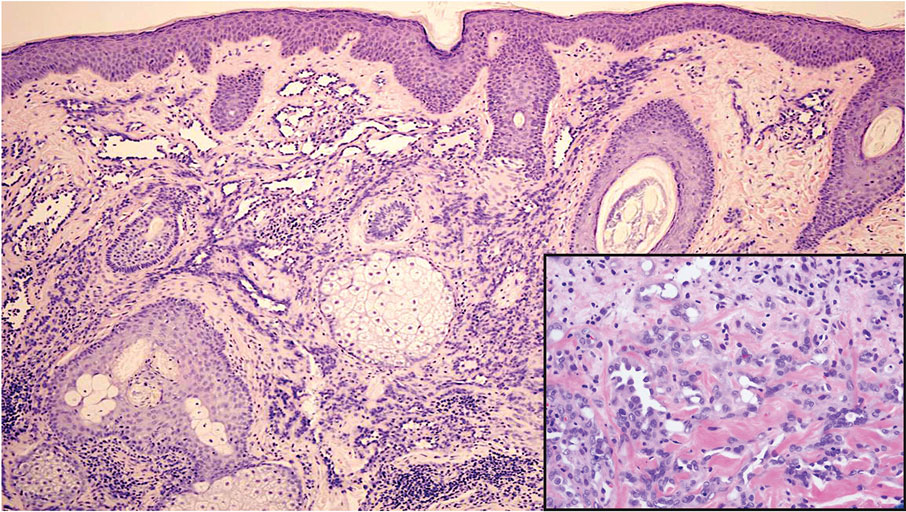

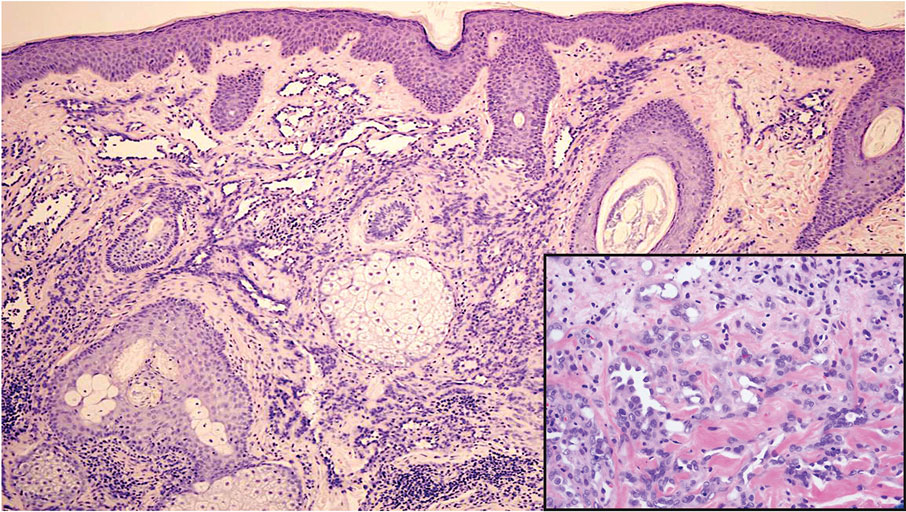

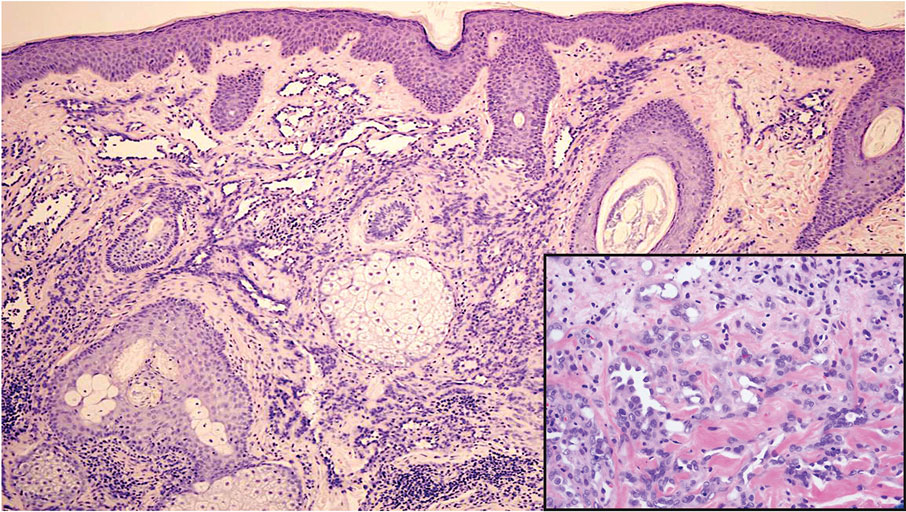

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that clinically presents as a firm, flesh-colored, dermal plaque on the trunk, proximal extremities, head, or neck.5 Histologically, DFSP can be distinguished from DDA by the high density of spindle cells that are arranged in a storiform pattern, extending and infiltrating the underlying subcutaneous fat in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 3). Spindle cells in DFSP typically show expression of CD34 but are negative for CD31, Erg, and factor XIIIa.5

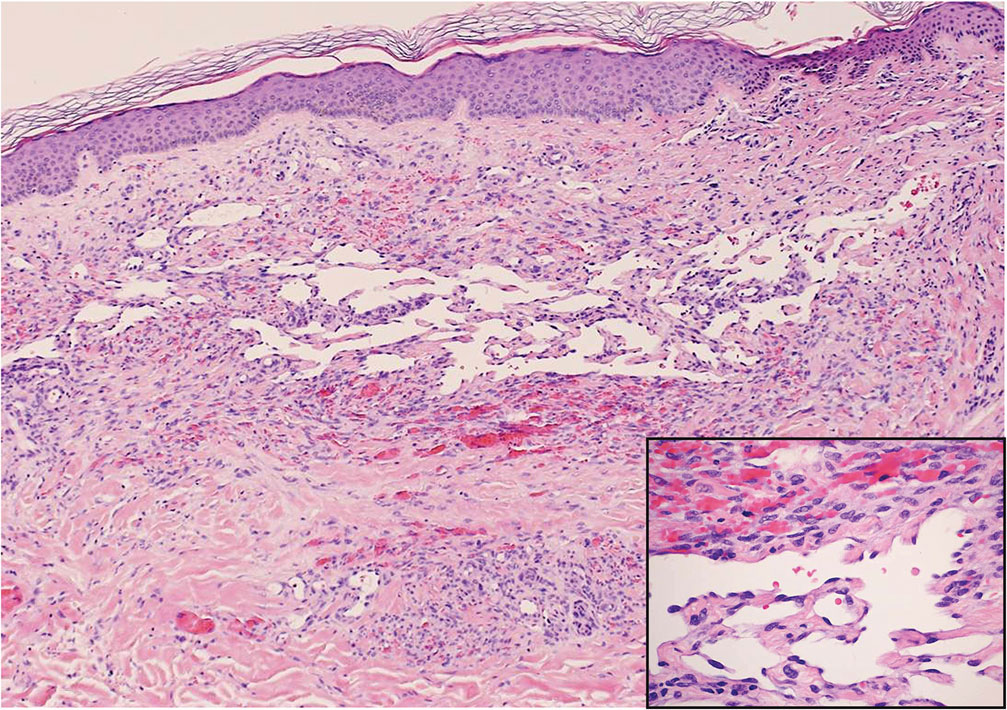

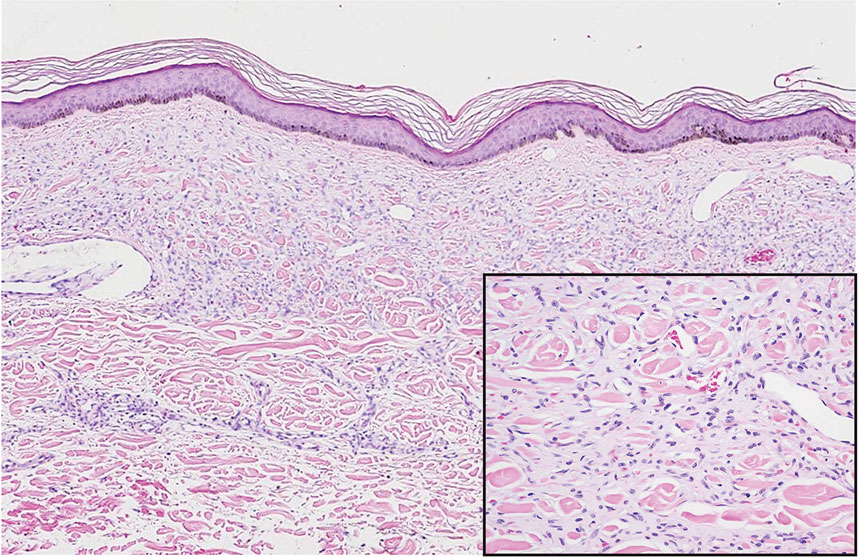

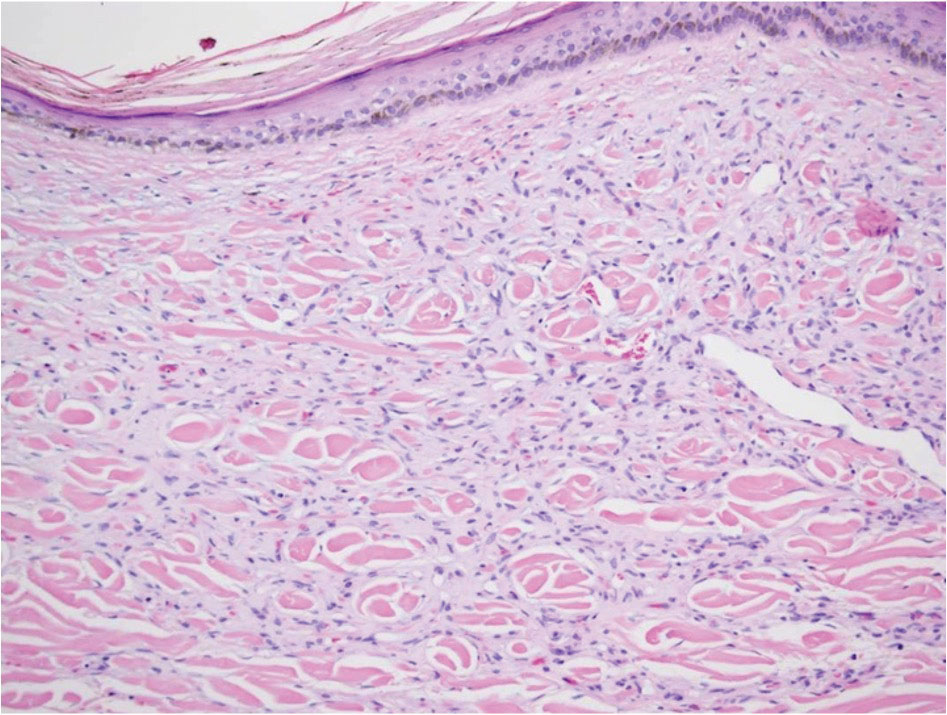

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an endothelial cell–driven angioproliferative neoplasm that is associated with HHV-8 infection.6 The clinical presentation of KS can range from isolated pink or purple papules and patches to more extensive ulcerated plaques or nodules. Histopathology exhibits proliferation of monomorphic spindled endothelial cells within the dermis staining positive for HHV-8, Erg, CD31, and CD34, in conjunction with extravasated erythrocytes arranged within slitlike vascular spaces (Figure 4). Additionally, KS classically exhibits aberrant endothelial cell proliferation and vessel formation around preexisting vessels, which is referred to as the promontory sign (Figure 4).

Angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive vascular tumor arising from endothelial cells lining the blood vessels and lymphatics.7,8 Clinically, angiosarcoma presents as ulcerated violaceous nodules or plaques on the head, neck, or trunk. Histologic evaluation of angiosarcoma reveals a complex and poorly demarcated vascular network dissecting between collagen bundles in the dermis (Figure 5). Multilayering of endothelial cells, papillary projections extending into the vessel lumina, and mitoses frequently are seen. On immunohistochemistry, endothelial cells demonstrate prominent cellular atypia and stain positive with CD31, CD34, and Erg.

- Touloei K, Tongdee E, Smirnov B, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Cutis. 2019;103:181-184.

- Nguyen N, Silfvast-Kaiser AS, Frieder J, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2020;33:273-275.

- Frikha F, Boudaya S, Abid N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with adjacent fat necrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt1vq114n7.

- Luzar B, Calonje E. Cutaneous fibrohistiocytic tumours—an update. Histopathology. 2010;56:148-165.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Etemad SA, Dewan AK. Kaposi sarcoma updates. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:505-517.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Shon W, Billings SD. Cutaneous malignant vascular neoplasms. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:633-646.

The Diagnosis: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is an acquired reactive vascular proliferation in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Clinically, DDA presents as violaceous reticulated plaques, often with secondary ulceration and sometimes necrosis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis more commonly presents in patients with a history of severe peripheral vascular disease, coagulopathies, or infection, and it frequently arises on the extremities. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis also has been shown to develop on the breasts, particularly in patients with pendulous breast tissue. Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to be from ischemia and hypoxia, leading to angiogenesis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized histologically by the presence of a diffuse proliferation of spindled endothelial cells distributed between the collagen bundles throughout the dermis (quiz image and Figure 1). Spindle-shaped endothelial cells exhibit a vacuolated cytoplasm. On immunohistochemistry, these dermal spindle cells classically stain positive for CD31, CD34, and erythroblast transformation specific–related gene (Erg) and stain negative for both human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and factor XIIIa.

Cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma, more commonly referred to as dermatofibroma, is a common benign lesion that presents clinically as a solitary firm nodule most commonly on the extremities in areas of repetitive trauma or pressure. It classically exhibits dimpling of the overlaying skin with lateral pressure on the lesion, known as the dimple sign.4 Histologically, dermatofibromas share similar features to DDA and demonstrate the presence of bland-appearing spindle cells within the dermis between the collagen bundles, resulting in collagen trapping. However, a distinguishing histologic feature of a dermatofibroma in comparison to DDA is the presence of epidermal hyperplasia overlying the dermatofibroma, leading to tabled rete ridges (Figure 2). Spindle cells in dermatofibromas are fibroblasts and have a distinct immunophenotype that includes factor XIIIa positivity and negative staining for CD31, CD34, and Erg.4,5

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a rare malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that clinically presents as a firm, flesh-colored, dermal plaque on the trunk, proximal extremities, head, or neck.5 Histologically, DFSP can be distinguished from DDA by the high density of spindle cells that are arranged in a storiform pattern, extending and infiltrating the underlying subcutaneous fat in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 3). Spindle cells in DFSP typically show expression of CD34 but are negative for CD31, Erg, and factor XIIIa.5

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is an endothelial cell–driven angioproliferative neoplasm that is associated with HHV-8 infection.6 The clinical presentation of KS can range from isolated pink or purple papules and patches to more extensive ulcerated plaques or nodules. Histopathology exhibits proliferation of monomorphic spindled endothelial cells within the dermis staining positive for HHV-8, Erg, CD31, and CD34, in conjunction with extravasated erythrocytes arranged within slitlike vascular spaces (Figure 4). Additionally, KS classically exhibits aberrant endothelial cell proliferation and vessel formation around preexisting vessels, which is referred to as the promontory sign (Figure 4).

Angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive vascular tumor arising from endothelial cells lining the blood vessels and lymphatics.7,8 Clinically, angiosarcoma presents as ulcerated violaceous nodules or plaques on the head, neck, or trunk. Histologic evaluation of angiosarcoma reveals a complex and poorly demarcated vascular network dissecting between collagen bundles in the dermis (Figure 5). Multilayering of endothelial cells, papillary projections extending into the vessel lumina, and mitoses frequently are seen. On immunohistochemistry, endothelial cells demonstrate prominent cellular atypia and stain positive with CD31, CD34, and Erg.

The Diagnosis: Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is an acquired reactive vascular proliferation in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Clinically, DDA presents as violaceous reticulated plaques, often with secondary ulceration and sometimes necrosis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis more commonly presents in patients with a history of severe peripheral vascular disease, coagulopathies, or infection, and it frequently arises on the extremities. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis also has been shown to develop on the breasts, particularly in patients with pendulous breast tissue. Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to be from ischemia and hypoxia, leading to angiogenesis.1-3 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is characterized histologically by the presence of a diffuse proliferation of spindled endothelial cells distributed between the collagen bundles throughout the dermis (quiz image and Figure 1). Spindle-shaped endothelial cells exhibit a vacuolated cytoplasm. On immunohistochemistry, these dermal spindle cells classically stain positive for CD31, CD34, and erythroblast transformation specific–related gene (Erg) and stain negative for both human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and factor XIIIa.