User login

Alcohol dependence in teens tied to subsequent depression

TOPLINE

Alcohol dependence, but not consumption, at age 18 years increases the risk for depression at age 24 years.

METHODOLOGY

- The study included 3,902 mostly White adolescents, about 58% female, born in England from April 1991 to December 1992, who were part of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) that examined genetic and environmental determinants of health and development.

- Participants completed the self-report Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) between the ages of 16 and 23 years, a period when average alcohol use increases rapidly.

- The primary outcome was probability for depression at age 24 years, using the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), a self-administered computerized clinical assessment of common mental disorder symptoms during the past week.

- Researchers assessed frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption as well as alcohol dependence.

- Confounders included sex, housing type, maternal education and depressive symptoms, parents’ alcohol use, conduct problems at age 4 years, being bullied, and smoking status.

TAKEAWAYS

- After adjustments, alcohol dependence at age 18 years was associated with depression at age 24 years (unstandardized probit coefficient 0.13; 95% confidence interval, 0.02-0.25; P = .019)

- The relationship appeared to persist for alcohol dependence at each age of the growth curve (17-22 years).

- There was no evidence that frequency or quantity of alcohol consumption at age 18 was significantly associated with depression at age 24, suggesting these factors may not increase the risk for later depression unless there are also features of dependency.

IN PRACTICE

“Our findings suggest that preventing alcohol dependence during adolescence, or treating it early, could reduce the risk of depression,” which could have important public health implications, the researchers write.

STUDY DETAILS

The study was carried out by researchers at the University of Bristol; University College London; Critical Thinking Unit, Public Health Directorate, NHS; University of Nottingham, all in the United Kingdom. It was published online in Lancet Psychiatry

LIMITATIONS

There was substantial attrition in the ALSPAC cohort from birth to age 24 years. The sample was recruited from one U.K. region and most participants were White. Measures of alcohol consumption and dependence excluded some features of abuse. And as this is an observational study, the possibility of residual confounding can’t be excluded.

DISCLOSURES

The investigators report no relevant disclosures. The study received support from the UK Medical Research Council and Alcohol Research UK.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE

Alcohol dependence, but not consumption, at age 18 years increases the risk for depression at age 24 years.

METHODOLOGY

- The study included 3,902 mostly White adolescents, about 58% female, born in England from April 1991 to December 1992, who were part of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) that examined genetic and environmental determinants of health and development.

- Participants completed the self-report Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) between the ages of 16 and 23 years, a period when average alcohol use increases rapidly.

- The primary outcome was probability for depression at age 24 years, using the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), a self-administered computerized clinical assessment of common mental disorder symptoms during the past week.

- Researchers assessed frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption as well as alcohol dependence.

- Confounders included sex, housing type, maternal education and depressive symptoms, parents’ alcohol use, conduct problems at age 4 years, being bullied, and smoking status.

TAKEAWAYS

- After adjustments, alcohol dependence at age 18 years was associated with depression at age 24 years (unstandardized probit coefficient 0.13; 95% confidence interval, 0.02-0.25; P = .019)

- The relationship appeared to persist for alcohol dependence at each age of the growth curve (17-22 years).

- There was no evidence that frequency or quantity of alcohol consumption at age 18 was significantly associated with depression at age 24, suggesting these factors may not increase the risk for later depression unless there are also features of dependency.

IN PRACTICE

“Our findings suggest that preventing alcohol dependence during adolescence, or treating it early, could reduce the risk of depression,” which could have important public health implications, the researchers write.

STUDY DETAILS

The study was carried out by researchers at the University of Bristol; University College London; Critical Thinking Unit, Public Health Directorate, NHS; University of Nottingham, all in the United Kingdom. It was published online in Lancet Psychiatry

LIMITATIONS

There was substantial attrition in the ALSPAC cohort from birth to age 24 years. The sample was recruited from one U.K. region and most participants were White. Measures of alcohol consumption and dependence excluded some features of abuse. And as this is an observational study, the possibility of residual confounding can’t be excluded.

DISCLOSURES

The investigators report no relevant disclosures. The study received support from the UK Medical Research Council and Alcohol Research UK.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE

Alcohol dependence, but not consumption, at age 18 years increases the risk for depression at age 24 years.

METHODOLOGY

- The study included 3,902 mostly White adolescents, about 58% female, born in England from April 1991 to December 1992, who were part of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) that examined genetic and environmental determinants of health and development.

- Participants completed the self-report Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) between the ages of 16 and 23 years, a period when average alcohol use increases rapidly.

- The primary outcome was probability for depression at age 24 years, using the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), a self-administered computerized clinical assessment of common mental disorder symptoms during the past week.

- Researchers assessed frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption as well as alcohol dependence.

- Confounders included sex, housing type, maternal education and depressive symptoms, parents’ alcohol use, conduct problems at age 4 years, being bullied, and smoking status.

TAKEAWAYS

- After adjustments, alcohol dependence at age 18 years was associated with depression at age 24 years (unstandardized probit coefficient 0.13; 95% confidence interval, 0.02-0.25; P = .019)

- The relationship appeared to persist for alcohol dependence at each age of the growth curve (17-22 years).

- There was no evidence that frequency or quantity of alcohol consumption at age 18 was significantly associated with depression at age 24, suggesting these factors may not increase the risk for later depression unless there are also features of dependency.

IN PRACTICE

“Our findings suggest that preventing alcohol dependence during adolescence, or treating it early, could reduce the risk of depression,” which could have important public health implications, the researchers write.

STUDY DETAILS

The study was carried out by researchers at the University of Bristol; University College London; Critical Thinking Unit, Public Health Directorate, NHS; University of Nottingham, all in the United Kingdom. It was published online in Lancet Psychiatry

LIMITATIONS

There was substantial attrition in the ALSPAC cohort from birth to age 24 years. The sample was recruited from one U.K. region and most participants were White. Measures of alcohol consumption and dependence excluded some features of abuse. And as this is an observational study, the possibility of residual confounding can’t be excluded.

DISCLOSURES

The investigators report no relevant disclosures. The study received support from the UK Medical Research Council and Alcohol Research UK.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cognitive decline risk in adult childhood cancer survivors

Among more than 2,300 adult survivors of childhood cancer and their siblings, who served as controls, new-onset memory impairment emerged more often in survivors decades later.

The increased risk was associated with the cancer treatment that was provided as well as modifiable health behaviors and chronic health conditions.

Even 35 years after being diagnosed, cancer survivors who never received chemotherapies or radiation therapies known to damage the brain reported far greater memory impairment than did their siblings, first author Nicholas Phillips, MD, told this news organization.

What the findings suggest is that “we need to educate oncologists and primary care providers on the risks our survivors face long after completion of therapy,” said Dr. Phillips, of the epidemiology and cancer control department at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Cancer survivors face an elevated risk for severe neurocognitive effects that can emerge 5-10 years following their diagnosis and treatment. However, it’s unclear whether new-onset neurocognitive problems can still develop a decade or more following diagnosis.

Over a long-term follow-up, Dr. Phillips and colleagues explored this question in 2,375 adult survivors of childhood cancer from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and 232 of their siblings.

Among the cancer cohort, 1,316 patients were survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 488 were survivors of central nervous system (CNS) tumors, and 571 had survived Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers determined the prevalence of new-onset neurocognitive impairment between baseline (23 years after diagnosis) and follow-up (35 years after diagnosis). New-onset neurocognitive impairment – present at follow-up but not at baseline – was defined as having a score in the worst 10% of the sibling cohort.

A higher proportion of survivors had new-onset memory impairment at follow-up compared with siblings. Specifically, about 8% of siblings had new-onset memory trouble, compared with 14% of ALL survivors treated with chemotherapy only, 26% of ALL survivors treated with cranial radiation, 35% of CNS tumor survivors, and 17% of Hodgkin lymphoma survivors.

New-onset memory impairment was associated with cranial radiation among CNS tumor survivors (relative risk [RR], 1.97) and alkylator chemotherapy at or above 8,000 mg/m2 among survivors of ALL who were treated without cranial radiation (RR, 2.80). The authors also found that smoking, low educational attainment, and low physical activity were associated with an elevated risk for new-onset memory impairment.

Dr. Phillips noted that current guidelines emphasize the importance of short-term monitoring of a survivor’s neurocognitive status on the basis of that person’s chemotherapy and radiation exposures.

However, “our study suggests that all survivors, regardless of their therapy, should be screened regularly for new-onset neurocognitive problems. And this screening should be done regularly for decades after diagnosis,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Phillips also noted the importance of communicating lifestyle modifications, such as not smoking and maintaining an active lifestyle.

“We need to start early and use the power of repetition when communicating with our survivors and their families,” Dr. Phillips said. “When our families and survivors hear the word ‘exercise,’ they think of gym memberships, lifting weights, and running on treadmills. But what we really want our survivors to do is stay active.”

What this means is engaging for about 2.5 hours a week in a range of activities, such as ballet, basketball, volleyball, bicycling, or swimming.

“And if our kids want to quit after 3 months, let them know that this is okay. They just need to replace that activity with another activity,” said Dr. Phillips. “We want them to find a fun hobby that they will enjoy that will keep them active.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Phillips has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among more than 2,300 adult survivors of childhood cancer and their siblings, who served as controls, new-onset memory impairment emerged more often in survivors decades later.

The increased risk was associated with the cancer treatment that was provided as well as modifiable health behaviors and chronic health conditions.

Even 35 years after being diagnosed, cancer survivors who never received chemotherapies or radiation therapies known to damage the brain reported far greater memory impairment than did their siblings, first author Nicholas Phillips, MD, told this news organization.

What the findings suggest is that “we need to educate oncologists and primary care providers on the risks our survivors face long after completion of therapy,” said Dr. Phillips, of the epidemiology and cancer control department at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Cancer survivors face an elevated risk for severe neurocognitive effects that can emerge 5-10 years following their diagnosis and treatment. However, it’s unclear whether new-onset neurocognitive problems can still develop a decade or more following diagnosis.

Over a long-term follow-up, Dr. Phillips and colleagues explored this question in 2,375 adult survivors of childhood cancer from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and 232 of their siblings.

Among the cancer cohort, 1,316 patients were survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 488 were survivors of central nervous system (CNS) tumors, and 571 had survived Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers determined the prevalence of new-onset neurocognitive impairment between baseline (23 years after diagnosis) and follow-up (35 years after diagnosis). New-onset neurocognitive impairment – present at follow-up but not at baseline – was defined as having a score in the worst 10% of the sibling cohort.

A higher proportion of survivors had new-onset memory impairment at follow-up compared with siblings. Specifically, about 8% of siblings had new-onset memory trouble, compared with 14% of ALL survivors treated with chemotherapy only, 26% of ALL survivors treated with cranial radiation, 35% of CNS tumor survivors, and 17% of Hodgkin lymphoma survivors.

New-onset memory impairment was associated with cranial radiation among CNS tumor survivors (relative risk [RR], 1.97) and alkylator chemotherapy at or above 8,000 mg/m2 among survivors of ALL who were treated without cranial radiation (RR, 2.80). The authors also found that smoking, low educational attainment, and low physical activity were associated with an elevated risk for new-onset memory impairment.

Dr. Phillips noted that current guidelines emphasize the importance of short-term monitoring of a survivor’s neurocognitive status on the basis of that person’s chemotherapy and radiation exposures.

However, “our study suggests that all survivors, regardless of their therapy, should be screened regularly for new-onset neurocognitive problems. And this screening should be done regularly for decades after diagnosis,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Phillips also noted the importance of communicating lifestyle modifications, such as not smoking and maintaining an active lifestyle.

“We need to start early and use the power of repetition when communicating with our survivors and their families,” Dr. Phillips said. “When our families and survivors hear the word ‘exercise,’ they think of gym memberships, lifting weights, and running on treadmills. But what we really want our survivors to do is stay active.”

What this means is engaging for about 2.5 hours a week in a range of activities, such as ballet, basketball, volleyball, bicycling, or swimming.

“And if our kids want to quit after 3 months, let them know that this is okay. They just need to replace that activity with another activity,” said Dr. Phillips. “We want them to find a fun hobby that they will enjoy that will keep them active.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Phillips has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among more than 2,300 adult survivors of childhood cancer and their siblings, who served as controls, new-onset memory impairment emerged more often in survivors decades later.

The increased risk was associated with the cancer treatment that was provided as well as modifiable health behaviors and chronic health conditions.

Even 35 years after being diagnosed, cancer survivors who never received chemotherapies or radiation therapies known to damage the brain reported far greater memory impairment than did their siblings, first author Nicholas Phillips, MD, told this news organization.

What the findings suggest is that “we need to educate oncologists and primary care providers on the risks our survivors face long after completion of therapy,” said Dr. Phillips, of the epidemiology and cancer control department at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Cancer survivors face an elevated risk for severe neurocognitive effects that can emerge 5-10 years following their diagnosis and treatment. However, it’s unclear whether new-onset neurocognitive problems can still develop a decade or more following diagnosis.

Over a long-term follow-up, Dr. Phillips and colleagues explored this question in 2,375 adult survivors of childhood cancer from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and 232 of their siblings.

Among the cancer cohort, 1,316 patients were survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 488 were survivors of central nervous system (CNS) tumors, and 571 had survived Hodgkin lymphoma.

The researchers determined the prevalence of new-onset neurocognitive impairment between baseline (23 years after diagnosis) and follow-up (35 years after diagnosis). New-onset neurocognitive impairment – present at follow-up but not at baseline – was defined as having a score in the worst 10% of the sibling cohort.

A higher proportion of survivors had new-onset memory impairment at follow-up compared with siblings. Specifically, about 8% of siblings had new-onset memory trouble, compared with 14% of ALL survivors treated with chemotherapy only, 26% of ALL survivors treated with cranial radiation, 35% of CNS tumor survivors, and 17% of Hodgkin lymphoma survivors.

New-onset memory impairment was associated with cranial radiation among CNS tumor survivors (relative risk [RR], 1.97) and alkylator chemotherapy at or above 8,000 mg/m2 among survivors of ALL who were treated without cranial radiation (RR, 2.80). The authors also found that smoking, low educational attainment, and low physical activity were associated with an elevated risk for new-onset memory impairment.

Dr. Phillips noted that current guidelines emphasize the importance of short-term monitoring of a survivor’s neurocognitive status on the basis of that person’s chemotherapy and radiation exposures.

However, “our study suggests that all survivors, regardless of their therapy, should be screened regularly for new-onset neurocognitive problems. And this screening should be done regularly for decades after diagnosis,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Phillips also noted the importance of communicating lifestyle modifications, such as not smoking and maintaining an active lifestyle.

“We need to start early and use the power of repetition when communicating with our survivors and their families,” Dr. Phillips said. “When our families and survivors hear the word ‘exercise,’ they think of gym memberships, lifting weights, and running on treadmills. But what we really want our survivors to do is stay active.”

What this means is engaging for about 2.5 hours a week in a range of activities, such as ballet, basketball, volleyball, bicycling, or swimming.

“And if our kids want to quit after 3 months, let them know that this is okay. They just need to replace that activity with another activity,” said Dr. Phillips. “We want them to find a fun hobby that they will enjoy that will keep them active.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Phillips has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Review may help clinicians treat adolescents with depression

Depression is common among Canadian adolescents and often goes unnoticed. Many family physicians report feeling unprepared to identify and manage depression in these patients.

“Depression is an increasingly common but treatable condition among adolescents,” the authors wrote. “Primary care physicians and pediatricians are well positioned to support the assessment and first-line management of depression in this group, helping patients to regain their health and function.”

The article was published in CMAJ.

Distinct presentation

More than 40% of cases of depression begin during childhood. Onset at this life stage is associated with worse severity of depression in adulthood and worse social, occupational, and physical health outcomes.

Depression is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Family history of depression is associated with a three- to fivefold increased risk of depression among older children. Genetic loci are known to be associated with depression, but exposure to parental depression, adverse childhood experiences, and family conflict are also linked to greater risk. Bullying and stigma are associated with greater risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth.

Compared with adults, adolescents with depression are more likely to be irritable and to have a labile mood, rather than a low mood. Social withdrawal is also more common among adolescents than among adults. Unusual features, such as hypersomnia and increased appetite, may also be present. Anxiety, somatic symptoms, psychomotor agitation, and hallucinations are more common in adolescents than in younger persons with depression. It is vital to assess risk of suicidality and self-injury as well as support systems, and validated scales such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale can be useful.

There is no consensus as to whether universal screening for depression is beneficial among adolescents. “Screening in this age group may be a reasonable approach, however, when implemented together with adequate systems that ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate follow-up,” wrote the authors.

Management of depression in adolescents should begin with psychoeducation and may include lifestyle modification, psychotherapy, and medication. “Importantly, a suicide risk assessment must be done to ensure appropriateness of an outpatient management plan and facilitate safety planning,” the authors wrote.

Lifestyle interventions may target physical activity, diet, and sleep, since unhealthy patterns in all three are associated with heightened symptoms of depression in this population. Regular moderate to vigorous physical activity, and perhaps physical activity of short duration, can improve mood in adolescents. Reduced consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks, processed foods, and meats, along with greater consumption of fruits and legumes, has been shown to reduce depressive symptoms in randomized, controlled trials with adults.

Among psychotherapeutic approaches, cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown the most evidence of efficacy among adolescents with depression, though it is less effective for those with more severe symptoms, poor coping skills, and nonsuicidal self-injury. Some evidence supports interpersonal therapy, which focuses on relationships and social functioning. The involvement of caregivers may improve the response, compared with psychotherapy that only includes the adolescent.

The authors recommend antidepressant medications in more severe cases or when psychotherapy is ineffective or impossible. Guidelines generally support trials with at least two SSRIs before switching to another drug class, since efficacy data for them are sparser, and other drugs have worse side effect profiles.

About 2% of adolescents with depression experience an increase in suicidal ideation and behavior after exposure to antidepressants, usually within the first weeks of initiation, so this potential risk should be discussed with patients and caregivers.

Clinicians feel unprepared

Commenting on the review, Pierre-Paul Tellier, MD, an associate professor of family medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said that clinicians frequently report that they do not feel confident in their ability to manage and diagnose adolescent depression. “We did two systematic reviews to look at the continuing professional development of family physicians in adolescent health, and it turned out that there’s really a very large lack. When we looked at residents and the training that they were getting in adolescent medicine, it was very similar, so they felt unprepared to deal with issues around mental health.”

Medication can be effective, but it can be seen as “an easy way out,” Dr. Tellier added. “It’s not necessarily an ideal plan. What we need to do is to change the person’s way of thinking, the person’s way of responding to a variety of things which will occur throughout their lives. People will have other transition periods in their lives. It’s best if they learn a variety of techniques to deal with depression.”

These techniques include exercise, relaxation methods [which reduce anxiety], and wellness training. Through such techniques, patients “learn a healthier way of living with themselves and who they are, and then this is a lifelong way of learning,” said Dr. Tellier. “If I give you a pill, what I’m teaching is, yes, you can feel better. But you’re not dealing with the problem, you’re just dealing with the symptoms.”

He frequently refers his patients to YouTube videos that outline and explain various strategies. A favorite is a deep breathing exercise presented by Jeremy Howick.

The authors and Dr. Tellier disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Depression is common among Canadian adolescents and often goes unnoticed. Many family physicians report feeling unprepared to identify and manage depression in these patients.

“Depression is an increasingly common but treatable condition among adolescents,” the authors wrote. “Primary care physicians and pediatricians are well positioned to support the assessment and first-line management of depression in this group, helping patients to regain their health and function.”

The article was published in CMAJ.

Distinct presentation

More than 40% of cases of depression begin during childhood. Onset at this life stage is associated with worse severity of depression in adulthood and worse social, occupational, and physical health outcomes.

Depression is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Family history of depression is associated with a three- to fivefold increased risk of depression among older children. Genetic loci are known to be associated with depression, but exposure to parental depression, adverse childhood experiences, and family conflict are also linked to greater risk. Bullying and stigma are associated with greater risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth.

Compared with adults, adolescents with depression are more likely to be irritable and to have a labile mood, rather than a low mood. Social withdrawal is also more common among adolescents than among adults. Unusual features, such as hypersomnia and increased appetite, may also be present. Anxiety, somatic symptoms, psychomotor agitation, and hallucinations are more common in adolescents than in younger persons with depression. It is vital to assess risk of suicidality and self-injury as well as support systems, and validated scales such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale can be useful.

There is no consensus as to whether universal screening for depression is beneficial among adolescents. “Screening in this age group may be a reasonable approach, however, when implemented together with adequate systems that ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate follow-up,” wrote the authors.

Management of depression in adolescents should begin with psychoeducation and may include lifestyle modification, psychotherapy, and medication. “Importantly, a suicide risk assessment must be done to ensure appropriateness of an outpatient management plan and facilitate safety planning,” the authors wrote.

Lifestyle interventions may target physical activity, diet, and sleep, since unhealthy patterns in all three are associated with heightened symptoms of depression in this population. Regular moderate to vigorous physical activity, and perhaps physical activity of short duration, can improve mood in adolescents. Reduced consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks, processed foods, and meats, along with greater consumption of fruits and legumes, has been shown to reduce depressive symptoms in randomized, controlled trials with adults.

Among psychotherapeutic approaches, cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown the most evidence of efficacy among adolescents with depression, though it is less effective for those with more severe symptoms, poor coping skills, and nonsuicidal self-injury. Some evidence supports interpersonal therapy, which focuses on relationships and social functioning. The involvement of caregivers may improve the response, compared with psychotherapy that only includes the adolescent.

The authors recommend antidepressant medications in more severe cases or when psychotherapy is ineffective or impossible. Guidelines generally support trials with at least two SSRIs before switching to another drug class, since efficacy data for them are sparser, and other drugs have worse side effect profiles.

About 2% of adolescents with depression experience an increase in suicidal ideation and behavior after exposure to antidepressants, usually within the first weeks of initiation, so this potential risk should be discussed with patients and caregivers.

Clinicians feel unprepared

Commenting on the review, Pierre-Paul Tellier, MD, an associate professor of family medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said that clinicians frequently report that they do not feel confident in their ability to manage and diagnose adolescent depression. “We did two systematic reviews to look at the continuing professional development of family physicians in adolescent health, and it turned out that there’s really a very large lack. When we looked at residents and the training that they were getting in adolescent medicine, it was very similar, so they felt unprepared to deal with issues around mental health.”

Medication can be effective, but it can be seen as “an easy way out,” Dr. Tellier added. “It’s not necessarily an ideal plan. What we need to do is to change the person’s way of thinking, the person’s way of responding to a variety of things which will occur throughout their lives. People will have other transition periods in their lives. It’s best if they learn a variety of techniques to deal with depression.”

These techniques include exercise, relaxation methods [which reduce anxiety], and wellness training. Through such techniques, patients “learn a healthier way of living with themselves and who they are, and then this is a lifelong way of learning,” said Dr. Tellier. “If I give you a pill, what I’m teaching is, yes, you can feel better. But you’re not dealing with the problem, you’re just dealing with the symptoms.”

He frequently refers his patients to YouTube videos that outline and explain various strategies. A favorite is a deep breathing exercise presented by Jeremy Howick.

The authors and Dr. Tellier disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Depression is common among Canadian adolescents and often goes unnoticed. Many family physicians report feeling unprepared to identify and manage depression in these patients.

“Depression is an increasingly common but treatable condition among adolescents,” the authors wrote. “Primary care physicians and pediatricians are well positioned to support the assessment and first-line management of depression in this group, helping patients to regain their health and function.”

The article was published in CMAJ.

Distinct presentation

More than 40% of cases of depression begin during childhood. Onset at this life stage is associated with worse severity of depression in adulthood and worse social, occupational, and physical health outcomes.

Depression is influenced by genetic and environmental factors. Family history of depression is associated with a three- to fivefold increased risk of depression among older children. Genetic loci are known to be associated with depression, but exposure to parental depression, adverse childhood experiences, and family conflict are also linked to greater risk. Bullying and stigma are associated with greater risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth.

Compared with adults, adolescents with depression are more likely to be irritable and to have a labile mood, rather than a low mood. Social withdrawal is also more common among adolescents than among adults. Unusual features, such as hypersomnia and increased appetite, may also be present. Anxiety, somatic symptoms, psychomotor agitation, and hallucinations are more common in adolescents than in younger persons with depression. It is vital to assess risk of suicidality and self-injury as well as support systems, and validated scales such as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale can be useful.

There is no consensus as to whether universal screening for depression is beneficial among adolescents. “Screening in this age group may be a reasonable approach, however, when implemented together with adequate systems that ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate follow-up,” wrote the authors.

Management of depression in adolescents should begin with psychoeducation and may include lifestyle modification, psychotherapy, and medication. “Importantly, a suicide risk assessment must be done to ensure appropriateness of an outpatient management plan and facilitate safety planning,” the authors wrote.

Lifestyle interventions may target physical activity, diet, and sleep, since unhealthy patterns in all three are associated with heightened symptoms of depression in this population. Regular moderate to vigorous physical activity, and perhaps physical activity of short duration, can improve mood in adolescents. Reduced consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks, processed foods, and meats, along with greater consumption of fruits and legumes, has been shown to reduce depressive symptoms in randomized, controlled trials with adults.

Among psychotherapeutic approaches, cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown the most evidence of efficacy among adolescents with depression, though it is less effective for those with more severe symptoms, poor coping skills, and nonsuicidal self-injury. Some evidence supports interpersonal therapy, which focuses on relationships and social functioning. The involvement of caregivers may improve the response, compared with psychotherapy that only includes the adolescent.

The authors recommend antidepressant medications in more severe cases or when psychotherapy is ineffective or impossible. Guidelines generally support trials with at least two SSRIs before switching to another drug class, since efficacy data for them are sparser, and other drugs have worse side effect profiles.

About 2% of adolescents with depression experience an increase in suicidal ideation and behavior after exposure to antidepressants, usually within the first weeks of initiation, so this potential risk should be discussed with patients and caregivers.

Clinicians feel unprepared

Commenting on the review, Pierre-Paul Tellier, MD, an associate professor of family medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said that clinicians frequently report that they do not feel confident in their ability to manage and diagnose adolescent depression. “We did two systematic reviews to look at the continuing professional development of family physicians in adolescent health, and it turned out that there’s really a very large lack. When we looked at residents and the training that they were getting in adolescent medicine, it was very similar, so they felt unprepared to deal with issues around mental health.”

Medication can be effective, but it can be seen as “an easy way out,” Dr. Tellier added. “It’s not necessarily an ideal plan. What we need to do is to change the person’s way of thinking, the person’s way of responding to a variety of things which will occur throughout their lives. People will have other transition periods in their lives. It’s best if they learn a variety of techniques to deal with depression.”

These techniques include exercise, relaxation methods [which reduce anxiety], and wellness training. Through such techniques, patients “learn a healthier way of living with themselves and who they are, and then this is a lifelong way of learning,” said Dr. Tellier. “If I give you a pill, what I’m teaching is, yes, you can feel better. But you’re not dealing with the problem, you’re just dealing with the symptoms.”

He frequently refers his patients to YouTube videos that outline and explain various strategies. A favorite is a deep breathing exercise presented by Jeremy Howick.

The authors and Dr. Tellier disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CMAJ

Suicidality risk in youth at highest at night

Investigators found that suicidal ideation and attempts were lowest in the mornings and highest in the evenings, particularly among youth with higher levels of self-critical rumination.

“These are preliminary findings, and there is a need for more data, but they signal potentially that there’s a need for support, particularly at nighttime, and that there might be a potential of targeting self-critical rumination in daily lives of youth,” said lead researcher Anastacia Kudinova, PhD, with the department of psychiatry and human behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I.

The findings were presented at the late-breaker session at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Urgent need

Suicidal ideation (SI) is a “robust” predictor of suicidal behavior and, “alarmingly,” both suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior have been increasing, Dr. Kudinova said.

“There is an urgent need to describe proximal time-period risk factors for suicide so that we can identify who is at a greater suicide risk on the time scale of weeks, days, or even hours,” she told attendees.

The researchers asked 165 psychiatrically hospitalized youth aged 11-18 (72% female) about the time of day of their most recent suicide attempt.

More than half (58%) said it occurred in the evenings and nights, followed by daytime (35%) and mornings (7%).

They also assessed the timing of suicidal ideation at home in 61 youth aged 12-15 (61% female) who were discharged after a partial hospitalization program.

They did this using ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) three times a day over 2 weeks. EMAs study people’s thoughts and behavior in their daily lives by repeatedly collecting data in an individual’s normal environment at or close to the time they carry out that behavior.

As in the other sample, youth in this sample also experienced significantly more frequent suicidal ideation later in the day (P < .01).

There was also a significant moderating effect of self-criticism (P < .01), such that more self-critical youth evidenced the highest levels of suicidal ideation later in the day.

True variation or mechanics?

Reached for comment, Paul Nestadt, MD, with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, noted that EMA is becoming “an interesting way to track high-resolution temporal variation in suicidal ideation and other psych symptoms.”

Dr. Nestadt, who was not involved in the study, said that “it’s not surprising” that the majority of youth attempted suicide in evenings and nights, “as adolescents are generally being supervised in a school setting during daytime hours. It may not be the fluctuation in suicidality that impacts attempt timing so much as the mechanics – it is very hard to attempt suicide in math class.”

The same may be true for the youth in the second sample who were in the partial hospital program. “During the day, they were in therapy groups where feelings of suicidal ideation would have been solicited and addressed in real time,” Dr. Nestadt noted.

“Again, suicidal ideation later in the day may be a practical effect of how they are occupied in the partial hospital program, as opposed to some inherent suicidal ideation increase linked to something endogenous, such as circadian rhythm or cortisol level rises. That said, we do often see more attempts in the evenings in adults as well,” he added.

A vulnerable time

Also weighing in, Casey O’Brien, PsyD, a psychologist in the department of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the findings in this study “track” with what she sees in the clinic.

Teens often report in session that the “unstructured time of night – especially the time when they usually should be getting to bed but are kind of staying up – tends to be a very vulnerable time for them,” Dr. O’Brien said in an interview.

“It’s really nice to have research confirm a lot of what we see reported anecdotally from the teens we work with,” said Dr. O’Brien.

Dr. O’Brien heads the intensive adolescent dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) program at Columbia for young people struggling with mental health issues.

“Within the DBT framework, we try to really focus on accepting that this is a vulnerable time and then planning ahead for what the strategies are that they can use to help them transition to bed quickly and smoothly,” Dr. O’Brien said.

These strategies may include spending time with their parents before bed, reading, or building into their bedtime routines things that they find soothing and comforting, like taking a longer shower or having comfortable pajamas to change into, she explained.

“We also work a lot on sleep hygiene strategies to help develop a regular bedtime and have a consistent sleep-wake cycle. We also will plan ahead for using distress tolerance skills during times of emotional vulnerability,” Dr. O’Brien said.

The Columbia DBT program also offers phone coaching “so teens can reach out to a therapist for help using skills outside of a therapeutic hour, and we do find that we get more coaching calls closer to around bedtime,” Dr. O’Brien said.

Support for the study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health and Bradley Hospital COBRE Center. Dr. Kudinova, Dr. Nestadt, and Dr. O’Brien have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that suicidal ideation and attempts were lowest in the mornings and highest in the evenings, particularly among youth with higher levels of self-critical rumination.

“These are preliminary findings, and there is a need for more data, but they signal potentially that there’s a need for support, particularly at nighttime, and that there might be a potential of targeting self-critical rumination in daily lives of youth,” said lead researcher Anastacia Kudinova, PhD, with the department of psychiatry and human behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I.

The findings were presented at the late-breaker session at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Urgent need

Suicidal ideation (SI) is a “robust” predictor of suicidal behavior and, “alarmingly,” both suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior have been increasing, Dr. Kudinova said.

“There is an urgent need to describe proximal time-period risk factors for suicide so that we can identify who is at a greater suicide risk on the time scale of weeks, days, or even hours,” she told attendees.

The researchers asked 165 psychiatrically hospitalized youth aged 11-18 (72% female) about the time of day of their most recent suicide attempt.

More than half (58%) said it occurred in the evenings and nights, followed by daytime (35%) and mornings (7%).

They also assessed the timing of suicidal ideation at home in 61 youth aged 12-15 (61% female) who were discharged after a partial hospitalization program.

They did this using ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) three times a day over 2 weeks. EMAs study people’s thoughts and behavior in their daily lives by repeatedly collecting data in an individual’s normal environment at or close to the time they carry out that behavior.

As in the other sample, youth in this sample also experienced significantly more frequent suicidal ideation later in the day (P < .01).

There was also a significant moderating effect of self-criticism (P < .01), such that more self-critical youth evidenced the highest levels of suicidal ideation later in the day.

True variation or mechanics?

Reached for comment, Paul Nestadt, MD, with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, noted that EMA is becoming “an interesting way to track high-resolution temporal variation in suicidal ideation and other psych symptoms.”

Dr. Nestadt, who was not involved in the study, said that “it’s not surprising” that the majority of youth attempted suicide in evenings and nights, “as adolescents are generally being supervised in a school setting during daytime hours. It may not be the fluctuation in suicidality that impacts attempt timing so much as the mechanics – it is very hard to attempt suicide in math class.”

The same may be true for the youth in the second sample who were in the partial hospital program. “During the day, they were in therapy groups where feelings of suicidal ideation would have been solicited and addressed in real time,” Dr. Nestadt noted.

“Again, suicidal ideation later in the day may be a practical effect of how they are occupied in the partial hospital program, as opposed to some inherent suicidal ideation increase linked to something endogenous, such as circadian rhythm or cortisol level rises. That said, we do often see more attempts in the evenings in adults as well,” he added.

A vulnerable time

Also weighing in, Casey O’Brien, PsyD, a psychologist in the department of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the findings in this study “track” with what she sees in the clinic.

Teens often report in session that the “unstructured time of night – especially the time when they usually should be getting to bed but are kind of staying up – tends to be a very vulnerable time for them,” Dr. O’Brien said in an interview.

“It’s really nice to have research confirm a lot of what we see reported anecdotally from the teens we work with,” said Dr. O’Brien.

Dr. O’Brien heads the intensive adolescent dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) program at Columbia for young people struggling with mental health issues.

“Within the DBT framework, we try to really focus on accepting that this is a vulnerable time and then planning ahead for what the strategies are that they can use to help them transition to bed quickly and smoothly,” Dr. O’Brien said.

These strategies may include spending time with their parents before bed, reading, or building into their bedtime routines things that they find soothing and comforting, like taking a longer shower or having comfortable pajamas to change into, she explained.

“We also work a lot on sleep hygiene strategies to help develop a regular bedtime and have a consistent sleep-wake cycle. We also will plan ahead for using distress tolerance skills during times of emotional vulnerability,” Dr. O’Brien said.

The Columbia DBT program also offers phone coaching “so teens can reach out to a therapist for help using skills outside of a therapeutic hour, and we do find that we get more coaching calls closer to around bedtime,” Dr. O’Brien said.

Support for the study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health and Bradley Hospital COBRE Center. Dr. Kudinova, Dr. Nestadt, and Dr. O’Brien have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that suicidal ideation and attempts were lowest in the mornings and highest in the evenings, particularly among youth with higher levels of self-critical rumination.

“These are preliminary findings, and there is a need for more data, but they signal potentially that there’s a need for support, particularly at nighttime, and that there might be a potential of targeting self-critical rumination in daily lives of youth,” said lead researcher Anastacia Kudinova, PhD, with the department of psychiatry and human behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I.

The findings were presented at the late-breaker session at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Urgent need

Suicidal ideation (SI) is a “robust” predictor of suicidal behavior and, “alarmingly,” both suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior have been increasing, Dr. Kudinova said.

“There is an urgent need to describe proximal time-period risk factors for suicide so that we can identify who is at a greater suicide risk on the time scale of weeks, days, or even hours,” she told attendees.

The researchers asked 165 psychiatrically hospitalized youth aged 11-18 (72% female) about the time of day of their most recent suicide attempt.

More than half (58%) said it occurred in the evenings and nights, followed by daytime (35%) and mornings (7%).

They also assessed the timing of suicidal ideation at home in 61 youth aged 12-15 (61% female) who were discharged after a partial hospitalization program.

They did this using ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) three times a day over 2 weeks. EMAs study people’s thoughts and behavior in their daily lives by repeatedly collecting data in an individual’s normal environment at or close to the time they carry out that behavior.

As in the other sample, youth in this sample also experienced significantly more frequent suicidal ideation later in the day (P < .01).

There was also a significant moderating effect of self-criticism (P < .01), such that more self-critical youth evidenced the highest levels of suicidal ideation later in the day.

True variation or mechanics?

Reached for comment, Paul Nestadt, MD, with Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, noted that EMA is becoming “an interesting way to track high-resolution temporal variation in suicidal ideation and other psych symptoms.”

Dr. Nestadt, who was not involved in the study, said that “it’s not surprising” that the majority of youth attempted suicide in evenings and nights, “as adolescents are generally being supervised in a school setting during daytime hours. It may not be the fluctuation in suicidality that impacts attempt timing so much as the mechanics – it is very hard to attempt suicide in math class.”

The same may be true for the youth in the second sample who were in the partial hospital program. “During the day, they were in therapy groups where feelings of suicidal ideation would have been solicited and addressed in real time,” Dr. Nestadt noted.

“Again, suicidal ideation later in the day may be a practical effect of how they are occupied in the partial hospital program, as opposed to some inherent suicidal ideation increase linked to something endogenous, such as circadian rhythm or cortisol level rises. That said, we do often see more attempts in the evenings in adults as well,” he added.

A vulnerable time

Also weighing in, Casey O’Brien, PsyD, a psychologist in the department of psychiatry at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, said the findings in this study “track” with what she sees in the clinic.

Teens often report in session that the “unstructured time of night – especially the time when they usually should be getting to bed but are kind of staying up – tends to be a very vulnerable time for them,” Dr. O’Brien said in an interview.

“It’s really nice to have research confirm a lot of what we see reported anecdotally from the teens we work with,” said Dr. O’Brien.

Dr. O’Brien heads the intensive adolescent dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) program at Columbia for young people struggling with mental health issues.

“Within the DBT framework, we try to really focus on accepting that this is a vulnerable time and then planning ahead for what the strategies are that they can use to help them transition to bed quickly and smoothly,” Dr. O’Brien said.

These strategies may include spending time with their parents before bed, reading, or building into their bedtime routines things that they find soothing and comforting, like taking a longer shower or having comfortable pajamas to change into, she explained.

“We also work a lot on sleep hygiene strategies to help develop a regular bedtime and have a consistent sleep-wake cycle. We also will plan ahead for using distress tolerance skills during times of emotional vulnerability,” Dr. O’Brien said.

The Columbia DBT program also offers phone coaching “so teens can reach out to a therapist for help using skills outside of a therapeutic hour, and we do find that we get more coaching calls closer to around bedtime,” Dr. O’Brien said.

Support for the study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health and Bradley Hospital COBRE Center. Dr. Kudinova, Dr. Nestadt, and Dr. O’Brien have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SLEEP 2023

Once-weekly growth hormone somapacitan approved for children

On May 26, the European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use adopted a positive opinion, recommending the product for replacement of endogenous growth hormone in children aged 3 years and older.

That decision followed the Food and Drug Administration’s approval in April of the new indication for somapacitan injection in 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg doses for children aged 2.5 years and older. The FDA approved the treatment for adults with growth hormone deficiency in September 2020.

Growth hormone deficiency is estimated to affect between 1 in 3,500 to 1 in 10,000 children. If left untreated, the condition can lead to shortened stature, reduced bone mineral density, and delayed appearance of teeth.

The European and American regulatory decisions were based on data from the phase 3 multinational REAL4 trial, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, in 200 prepubertal children with growth hormone deficiency randomly assigned 2:1 to weekly subcutaneous somapacitan or daily somatropin. At 52 weeks, height velocity was 11.2 cm/year with the once-weekly drug, compared with 11.7 cm/year with daily somatropin, a nonsignificant difference.

There were no major differences between the drugs in safety or tolerability. Adverse reactions in the REAL4 study that occurred in more than 5% of patients included nasopharyngitis, headache, pyrexia, extremity pain, and injection site reactions. A 3-year extension trial is ongoing.

The European Commission is expected to make a final decision in the coming months, and if approved somapacitan will be available in some European countries beginning in late 2023.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On May 26, the European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use adopted a positive opinion, recommending the product for replacement of endogenous growth hormone in children aged 3 years and older.

That decision followed the Food and Drug Administration’s approval in April of the new indication for somapacitan injection in 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg doses for children aged 2.5 years and older. The FDA approved the treatment for adults with growth hormone deficiency in September 2020.

Growth hormone deficiency is estimated to affect between 1 in 3,500 to 1 in 10,000 children. If left untreated, the condition can lead to shortened stature, reduced bone mineral density, and delayed appearance of teeth.

The European and American regulatory decisions were based on data from the phase 3 multinational REAL4 trial, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, in 200 prepubertal children with growth hormone deficiency randomly assigned 2:1 to weekly subcutaneous somapacitan or daily somatropin. At 52 weeks, height velocity was 11.2 cm/year with the once-weekly drug, compared with 11.7 cm/year with daily somatropin, a nonsignificant difference.

There were no major differences between the drugs in safety or tolerability. Adverse reactions in the REAL4 study that occurred in more than 5% of patients included nasopharyngitis, headache, pyrexia, extremity pain, and injection site reactions. A 3-year extension trial is ongoing.

The European Commission is expected to make a final decision in the coming months, and if approved somapacitan will be available in some European countries beginning in late 2023.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On May 26, the European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use adopted a positive opinion, recommending the product for replacement of endogenous growth hormone in children aged 3 years and older.

That decision followed the Food and Drug Administration’s approval in April of the new indication for somapacitan injection in 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg doses for children aged 2.5 years and older. The FDA approved the treatment for adults with growth hormone deficiency in September 2020.

Growth hormone deficiency is estimated to affect between 1 in 3,500 to 1 in 10,000 children. If left untreated, the condition can lead to shortened stature, reduced bone mineral density, and delayed appearance of teeth.

The European and American regulatory decisions were based on data from the phase 3 multinational REAL4 trial, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, in 200 prepubertal children with growth hormone deficiency randomly assigned 2:1 to weekly subcutaneous somapacitan or daily somatropin. At 52 weeks, height velocity was 11.2 cm/year with the once-weekly drug, compared with 11.7 cm/year with daily somatropin, a nonsignificant difference.

There were no major differences between the drugs in safety or tolerability. Adverse reactions in the REAL4 study that occurred in more than 5% of patients included nasopharyngitis, headache, pyrexia, extremity pain, and injection site reactions. A 3-year extension trial is ongoing.

The European Commission is expected to make a final decision in the coming months, and if approved somapacitan will be available in some European countries beginning in late 2023.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Extensive Erosions and Ulcerations on the Trunk and Extremities in a Neonate

The Diagnosis: Dominant Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa

Blisters in a neonate may be caused by infectious, traumatic, autoimmune, or congenital etiologies. Biopsy findings correlated with clinical findings usually can establish a prompt diagnosis when the clinical diagnosis is uncertain. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as well as indirect immunofluorescence studies are useful when autoimmune blistering disease or congenital or heritable disorders of skin fragility are in the differential diagnosis. Many genetic abnormalities of skin fragility are associated with marked morbidity and mortality, and prompt diagnosis is essential to provide proper care. Our patient’s parents had no history of skin disorders, and there was no known family history of blistering disease or traumatic birth. A heritable disorder of skin fragility was still a top consideration because of the extensive blistering in the absence of any other symptoms.

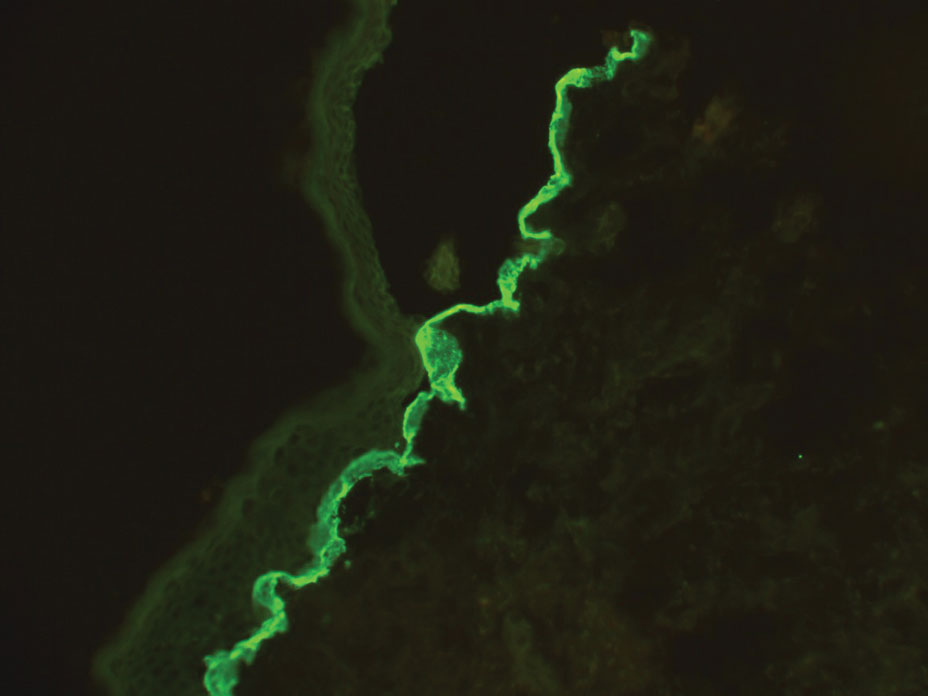

Although dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is an uncommon cause of skin fragility in neonates, our patient’s presentation was typical because of the extensive blistering and increased fragility of the skin at pressure points. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa has both dominant and recessive presentations that span a spectrum from mild and focal skin blistering to extensive blistering with esophageal involvement.1 Early diagnosis and treatment can mitigate potential failure to thrive or premature death. Inherited mutations in the type VII collagen gene, COL7A1, are causative.2 Dominant DEB may be associated with dental caries, swallowing problems secondary to esophageal scarring, and constipation, as well as dystrophic or absent nails. Immunomapping studies of the skin often reveal type VII collagen cytoplasmic granules in the epidermis and weaker reaction in the roof of the subepidermal separation (quiz image).3 Abnormalities in type VII collagen impact the production of anchoring fibrils. Blister cleavage occurs in the sublamina densa with type VII collagen staining evident on the blister roof (quiz image).4 Patients with severe generalized recessive DEB may have barely detectable type VII collagen. In our patient, the cytoplasmic staining and weak staining in the epidermal roof of the separation confirmed the clinical impression of dominant DEB.

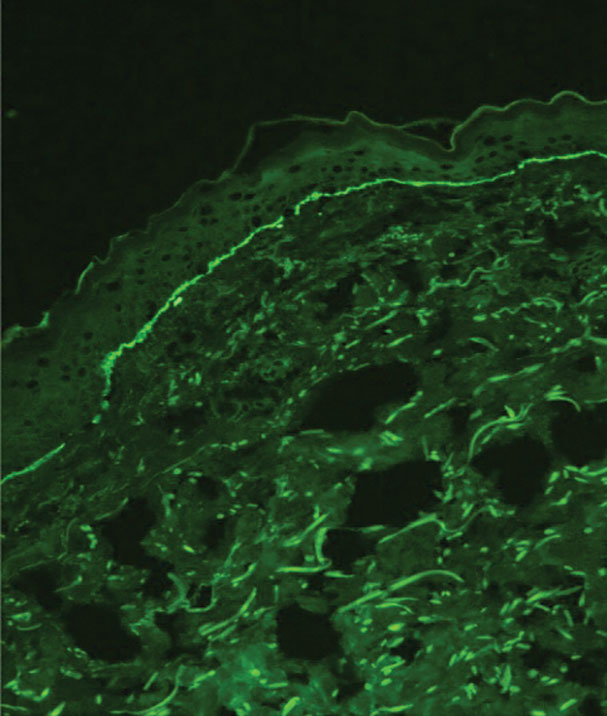

Autoimmune blistering disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, but it usually is associated with obvious disease in the mother. Direct immunofluorescence of pemphigoid gestationis reveals linear deposition of C3 at the basement membrane zone, which also can be associated with IgG (Figure 1). Neonates receiving passive transfer of antibodies may develop annular erythema, vesicles, and even dyshidroticlike changes on the soles.5

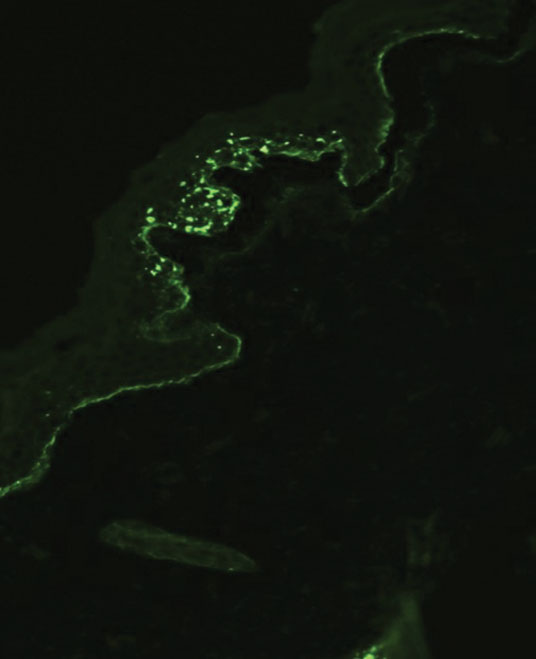

Suction blisters are subepithelial.6,7 When they occur in the neonatal period, they often are localized and are thought to be the result of vigorous sucking in utero.6 They quickly resolve without treatment and do not reveal abnormalities on DIF. If immunomapping is done for type VII collagen, it will be located at the floor of the suction blister (Figure 2).

Bullous pemphigoid is associated with deposition of linear IgG along the dermoepidermal junction—IgG4 is most common—and/or C3 (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence on split-skin biopsy reveals IgG on the epidermal side of the blister in bullous pemphigoid in contrast to epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, where the immune deposits are found on the dermal side of the split.8,9 Linear IgA bullous disease is associated with IgA deposition (Figure 4).10,11 Secretory IgA derived from breast milk can be causative.11 Neonatal linear IgA bullous disease is a serious condition associated with marked mucosal involvement that can eventuate in respiratory compromise. Prompt recognition is important; breastfeeding must be stopped and supportive therapy must be provided.

Other types of vesicular or pustular eruptions in the newborn usually are easily diagnosed by their typical clinical presentation without biopsy. Erythema toxicum neonatorum usually presents within 1 to 2 days of birth. It is self-limited and often resembles acne, but it also occurs on the trunk and extremities. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be present at birth and predominantly is seen in newborns with skin of color. Lesions easily rupture and usually resolve within 1 to 2 days. Infectious causes of blistering often can be identified on clinical examination and confirmed by culture. Herpes simplex virus infection is associated with characteristic multinucleated giant cells as well as steel grey nuclei evident on routine histologic evaluation. Bullous impetigo reveals superficial acantholysis and will have negative findings on DIF.12

When a neonate presents with widespread blistering, both genetic disorders of skin fragility as well as passive transfer of antibodies from maternal autoimmune disease need to be considered. Direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence immunomapping findings can be useful in clarifying the diagnosis when heritable disorders of skin fragility or autoimmune blistering diseases are a clinical consideration.

- Has C, Bauer JW, Bodemer C, et al. Consensus reclassification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa and other disorders with skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:614-627. doi:10.1111/bjd.18921

- Dang N, Murrell DF. Mutation analysis and characterization of COL7A1 mutations in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:553-568. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00723.x

- Has C, He Y. Research techniques made simple: immunofluorescence antigen mapping in epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:E65-E71. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.05.093

- Rao R, Mellerio J, Bhogal BS, et al. Immunofluorescence antigen mapping for hereditary epidermolysis bullosa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:692-697.

- Aoyama Y, Asai K, Hioki K, et al. Herpes gestationis in a mother and newborn: immunoclinical perspectives based on a weekly followup of the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index of a bullous pemphigoid antigen noncollagenous domain. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1168-1172. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.9.1168

- Afsar FS, Cun S, Seremet S. Neonatal sucking blister [published online November 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030 /qt33b1w59j.

- Yu WY, Wei ML. Suction blisters. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:237. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3277

- Gupta R, Woodley DT, Chen M. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:60-69.

- Reis-Filho EG, Silva Tde A, Aguirre LH, et al. Bullous pemphigoid in a 3-month-old infant: case report and literature review of this dermatosis in childhood. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:961-965. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132378

- Hruza LL, Mallory SB, Fitzgibbons J, et al. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis in a neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:171-176. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470

- Egami S, Suzuki C, Kurihara Y, et al. Neonatal linear IgA bullous dermatosis mediated by breast milk–borne maternal IgA. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1107-1111. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2392

- Ligtenberg KG, Hu JK, Panse G, et al. Bullous impetigo masquerading as pemphigus foliaceus in an adult patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2020; 6:428-430. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.02.040

The Diagnosis: Dominant Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa

Blisters in a neonate may be caused by infectious, traumatic, autoimmune, or congenital etiologies. Biopsy findings correlated with clinical findings usually can establish a prompt diagnosis when the clinical diagnosis is uncertain. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as well as indirect immunofluorescence studies are useful when autoimmune blistering disease or congenital or heritable disorders of skin fragility are in the differential diagnosis. Many genetic abnormalities of skin fragility are associated with marked morbidity and mortality, and prompt diagnosis is essential to provide proper care. Our patient’s parents had no history of skin disorders, and there was no known family history of blistering disease or traumatic birth. A heritable disorder of skin fragility was still a top consideration because of the extensive blistering in the absence of any other symptoms.

Although dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is an uncommon cause of skin fragility in neonates, our patient’s presentation was typical because of the extensive blistering and increased fragility of the skin at pressure points. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa has both dominant and recessive presentations that span a spectrum from mild and focal skin blistering to extensive blistering with esophageal involvement.1 Early diagnosis and treatment can mitigate potential failure to thrive or premature death. Inherited mutations in the type VII collagen gene, COL7A1, are causative.2 Dominant DEB may be associated with dental caries, swallowing problems secondary to esophageal scarring, and constipation, as well as dystrophic or absent nails. Immunomapping studies of the skin often reveal type VII collagen cytoplasmic granules in the epidermis and weaker reaction in the roof of the subepidermal separation (quiz image).3 Abnormalities in type VII collagen impact the production of anchoring fibrils. Blister cleavage occurs in the sublamina densa with type VII collagen staining evident on the blister roof (quiz image).4 Patients with severe generalized recessive DEB may have barely detectable type VII collagen. In our patient, the cytoplasmic staining and weak staining in the epidermal roof of the separation confirmed the clinical impression of dominant DEB.

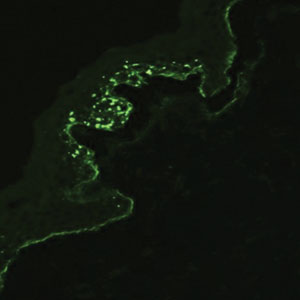

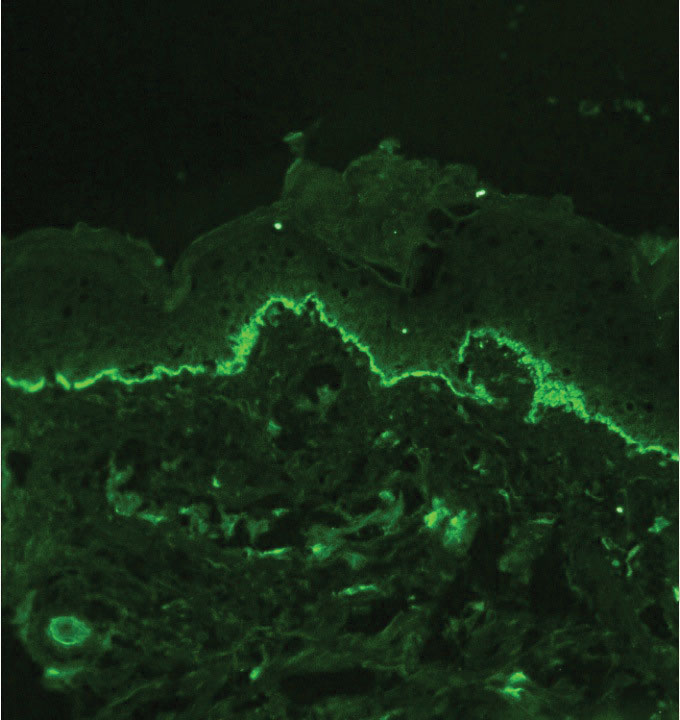

Autoimmune blistering disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, but it usually is associated with obvious disease in the mother. Direct immunofluorescence of pemphigoid gestationis reveals linear deposition of C3 at the basement membrane zone, which also can be associated with IgG (Figure 1). Neonates receiving passive transfer of antibodies may develop annular erythema, vesicles, and even dyshidroticlike changes on the soles.5

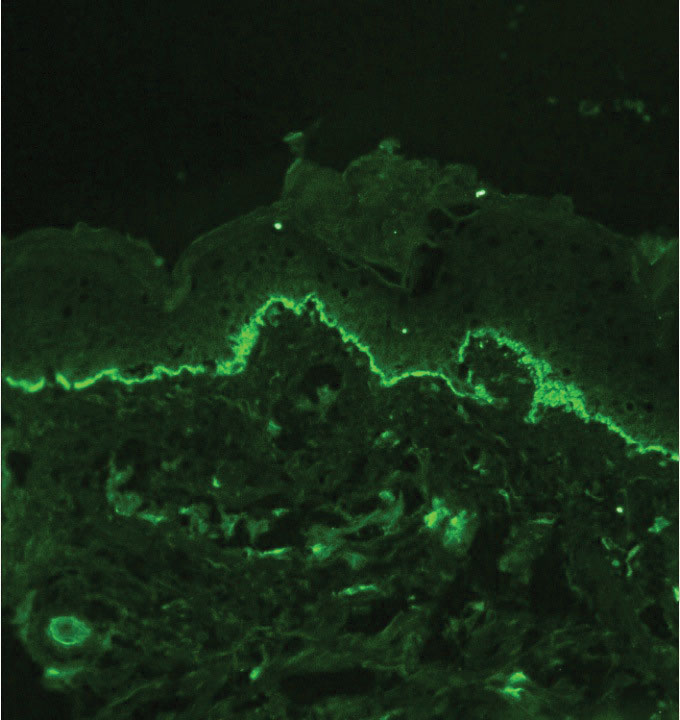

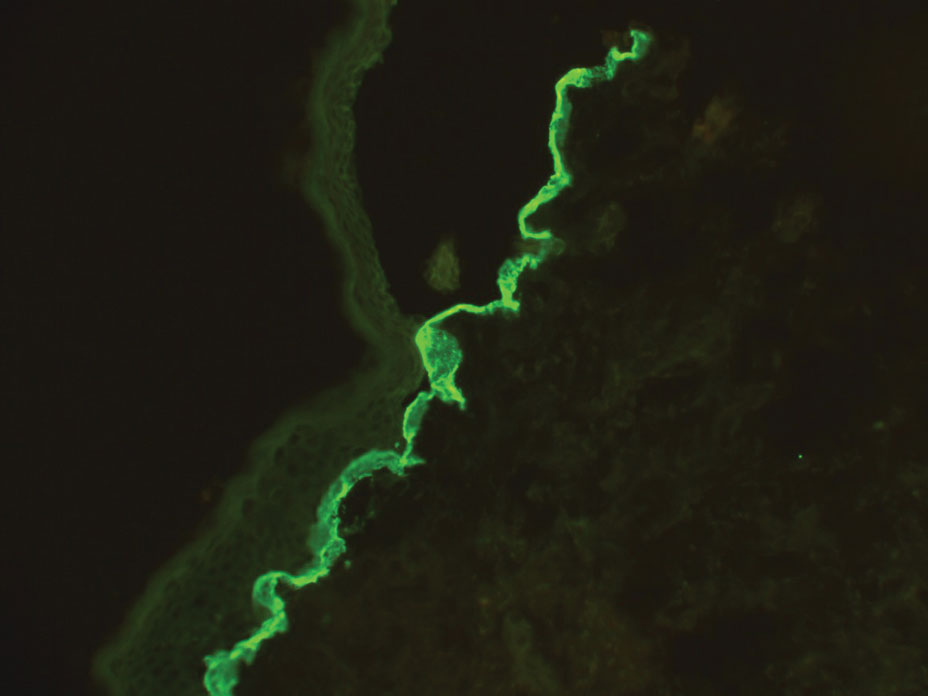

Suction blisters are subepithelial.6,7 When they occur in the neonatal period, they often are localized and are thought to be the result of vigorous sucking in utero.6 They quickly resolve without treatment and do not reveal abnormalities on DIF. If immunomapping is done for type VII collagen, it will be located at the floor of the suction blister (Figure 2).

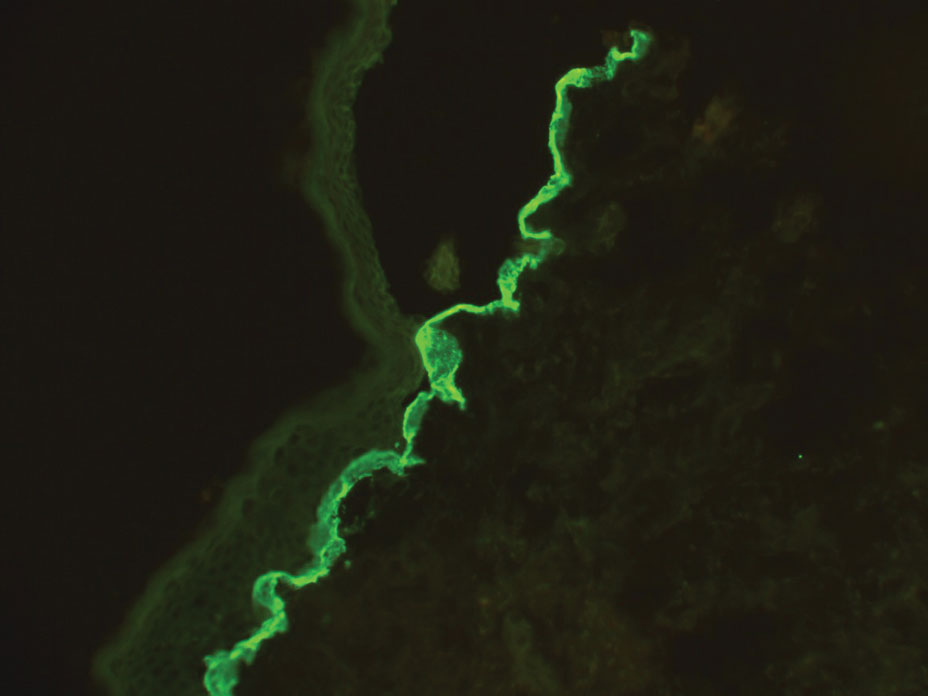

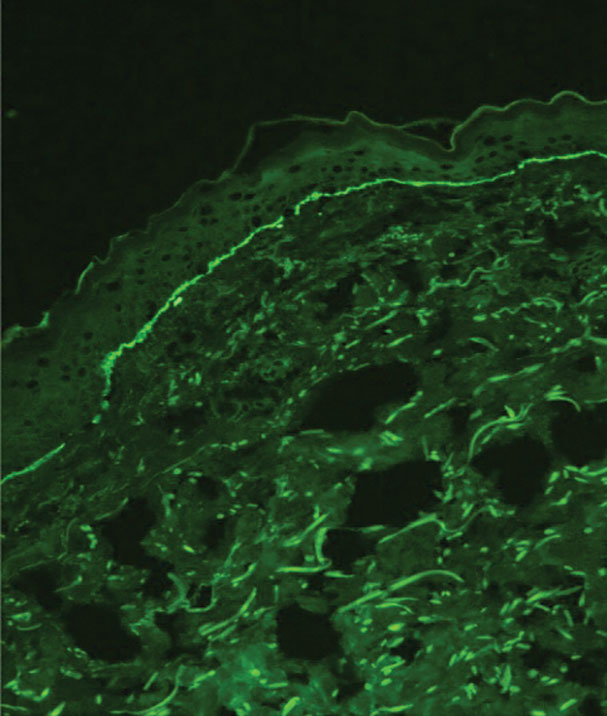

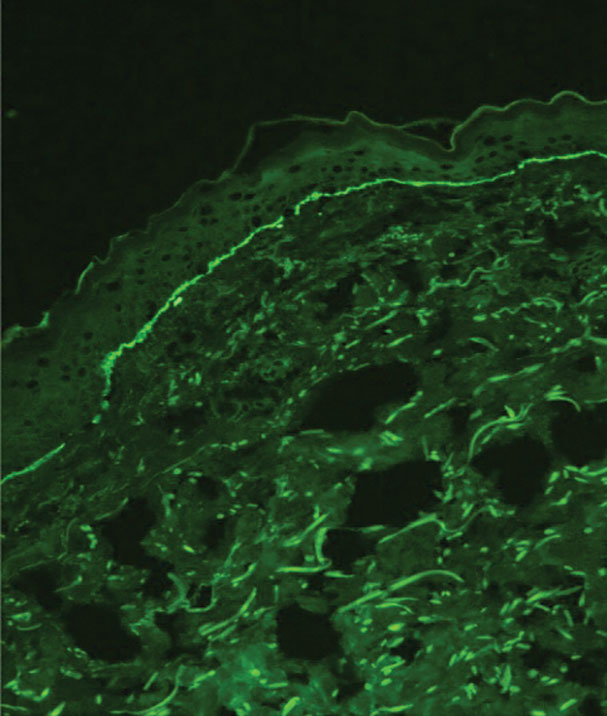

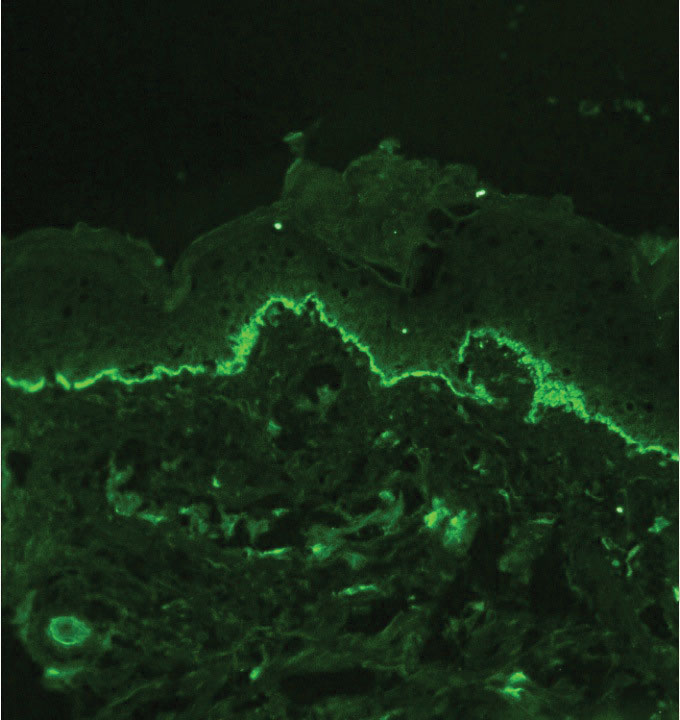

Bullous pemphigoid is associated with deposition of linear IgG along the dermoepidermal junction—IgG4 is most common—and/or C3 (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence on split-skin biopsy reveals IgG on the epidermal side of the blister in bullous pemphigoid in contrast to epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, where the immune deposits are found on the dermal side of the split.8,9 Linear IgA bullous disease is associated with IgA deposition (Figure 4).10,11 Secretory IgA derived from breast milk can be causative.11 Neonatal linear IgA bullous disease is a serious condition associated with marked mucosal involvement that can eventuate in respiratory compromise. Prompt recognition is important; breastfeeding must be stopped and supportive therapy must be provided.

Other types of vesicular or pustular eruptions in the newborn usually are easily diagnosed by their typical clinical presentation without biopsy. Erythema toxicum neonatorum usually presents within 1 to 2 days of birth. It is self-limited and often resembles acne, but it also occurs on the trunk and extremities. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be present at birth and predominantly is seen in newborns with skin of color. Lesions easily rupture and usually resolve within 1 to 2 days. Infectious causes of blistering often can be identified on clinical examination and confirmed by culture. Herpes simplex virus infection is associated with characteristic multinucleated giant cells as well as steel grey nuclei evident on routine histologic evaluation. Bullous impetigo reveals superficial acantholysis and will have negative findings on DIF.12

When a neonate presents with widespread blistering, both genetic disorders of skin fragility as well as passive transfer of antibodies from maternal autoimmune disease need to be considered. Direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence immunomapping findings can be useful in clarifying the diagnosis when heritable disorders of skin fragility or autoimmune blistering diseases are a clinical consideration.

The Diagnosis: Dominant Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa

Blisters in a neonate may be caused by infectious, traumatic, autoimmune, or congenital etiologies. Biopsy findings correlated with clinical findings usually can establish a prompt diagnosis when the clinical diagnosis is uncertain. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) as well as indirect immunofluorescence studies are useful when autoimmune blistering disease or congenital or heritable disorders of skin fragility are in the differential diagnosis. Many genetic abnormalities of skin fragility are associated with marked morbidity and mortality, and prompt diagnosis is essential to provide proper care. Our patient’s parents had no history of skin disorders, and there was no known family history of blistering disease or traumatic birth. A heritable disorder of skin fragility was still a top consideration because of the extensive blistering in the absence of any other symptoms.

Although dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is an uncommon cause of skin fragility in neonates, our patient’s presentation was typical because of the extensive blistering and increased fragility of the skin at pressure points. Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa has both dominant and recessive presentations that span a spectrum from mild and focal skin blistering to extensive blistering with esophageal involvement.1 Early diagnosis and treatment can mitigate potential failure to thrive or premature death. Inherited mutations in the type VII collagen gene, COL7A1, are causative.2 Dominant DEB may be associated with dental caries, swallowing problems secondary to esophageal scarring, and constipation, as well as dystrophic or absent nails. Immunomapping studies of the skin often reveal type VII collagen cytoplasmic granules in the epidermis and weaker reaction in the roof of the subepidermal separation (quiz image).3 Abnormalities in type VII collagen impact the production of anchoring fibrils. Blister cleavage occurs in the sublamina densa with type VII collagen staining evident on the blister roof (quiz image).4 Patients with severe generalized recessive DEB may have barely detectable type VII collagen. In our patient, the cytoplasmic staining and weak staining in the epidermal roof of the separation confirmed the clinical impression of dominant DEB.

Autoimmune blistering disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, but it usually is associated with obvious disease in the mother. Direct immunofluorescence of pemphigoid gestationis reveals linear deposition of C3 at the basement membrane zone, which also can be associated with IgG (Figure 1). Neonates receiving passive transfer of antibodies may develop annular erythema, vesicles, and even dyshidroticlike changes on the soles.5

Suction blisters are subepithelial.6,7 When they occur in the neonatal period, they often are localized and are thought to be the result of vigorous sucking in utero.6 They quickly resolve without treatment and do not reveal abnormalities on DIF. If immunomapping is done for type VII collagen, it will be located at the floor of the suction blister (Figure 2).

Bullous pemphigoid is associated with deposition of linear IgG along the dermoepidermal junction—IgG4 is most common—and/or C3 (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence on split-skin biopsy reveals IgG on the epidermal side of the blister in bullous pemphigoid in contrast to epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, where the immune deposits are found on the dermal side of the split.8,9 Linear IgA bullous disease is associated with IgA deposition (Figure 4).10,11 Secretory IgA derived from breast milk can be causative.11 Neonatal linear IgA bullous disease is a serious condition associated with marked mucosal involvement that can eventuate in respiratory compromise. Prompt recognition is important; breastfeeding must be stopped and supportive therapy must be provided.

Other types of vesicular or pustular eruptions in the newborn usually are easily diagnosed by their typical clinical presentation without biopsy. Erythema toxicum neonatorum usually presents within 1 to 2 days of birth. It is self-limited and often resembles acne, but it also occurs on the trunk and extremities. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be present at birth and predominantly is seen in newborns with skin of color. Lesions easily rupture and usually resolve within 1 to 2 days. Infectious causes of blistering often can be identified on clinical examination and confirmed by culture. Herpes simplex virus infection is associated with characteristic multinucleated giant cells as well as steel grey nuclei evident on routine histologic evaluation. Bullous impetigo reveals superficial acantholysis and will have negative findings on DIF.12

When a neonate presents with widespread blistering, both genetic disorders of skin fragility as well as passive transfer of antibodies from maternal autoimmune disease need to be considered. Direct immunofluorescence and indirect immunofluorescence immunomapping findings can be useful in clarifying the diagnosis when heritable disorders of skin fragility or autoimmune blistering diseases are a clinical consideration.

- Has C, Bauer JW, Bodemer C, et al. Consensus reclassification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa and other disorders with skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:614-627. doi:10.1111/bjd.18921

- Dang N, Murrell DF. Mutation analysis and characterization of COL7A1 mutations in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:553-568. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00723.x

- Has C, He Y. Research techniques made simple: immunofluorescence antigen mapping in epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:E65-E71. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.05.093

- Rao R, Mellerio J, Bhogal BS, et al. Immunofluorescence antigen mapping for hereditary epidermolysis bullosa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:692-697.